The Palestinians and Amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act: U.S. Aid and Personal Jurisdiction

Two recent amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2331 et seq.) have significant implications for U.S. aid to the Palestinians and U.S. courts’ ability to exercise jurisdiction over Palestinian entities. They are the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253) and the Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019 (PSJVTA, § 903 of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94).

Congress passed ATCA after a U.S. federal lawsuit (known in various incarnations as Waldman v. PLO and Sokolow v. PLO) against the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that an appeals court dismissed in 2016. The trial court had found that the PA and PLO were responsible under ATA (at 18 U.S.C. § 2333) for various terrorist attacks by providing material support to the perpetrators. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that the attacks, “as heinous as they were, were not sufficiently connected to the United States to provide specific personal jurisdiction” in U.S. federal courts.

Amendments to ATA. ATCA provided that a defendant consents to personal jurisdiction in U.S. federal court for lawsuits related to international terrorism if the defendant accepts U.S. foreign aid from any of the three accounts from which U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians has traditionally flowed. In December 2018, the PA informed the United States that it would not accept aid that subjected it to federal court jurisdiction. Consequently, all bilateral aid ended on January 31, 2019.

PSJVTA eliminated a defendant’s acceptance of U.S. foreign aid as a trigger of consent to personal jurisdiction—thus partly reversing ATCA—and instead provides that PA/PLO payments related to a terrorist act that kills or injures a U.S. national act as a trigger of consent to personal jurisdiction. The PA/PLO may face strong Palestinian domestic opposition to discontinuing such payments. PSJVTA also directs the State Department to establish a mechanism for resolving and settling plaintiff claims against the PA/PLO. President Trump stated in a signing statement that this provision could interfere with the exercise of his “constitutional authorities to articulate the position of the United States in international negotiations or fora.”

Implications of stopping U.S. aid and prospects for resumption. It is unclear to what extent the stop to U.S. security assistance for the PA has affected Israel-PA security cooperation and could affect it in the future. The U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC) said in December 2019 that the suspension of aid had not significantly affected Israel-PA security cooperation, but that the disruption of initiatives aimed at facilitating cooperation and helping reform the PA security sector had some impact on PA acquiescence to USSC requests aimed at reform and greater professionalization.

Even though PSJVTA removed acceptance of U.S. bilateral aid as a trigger for personal jurisdiction, the actual resumption of U.S. aid may depend on political decisions by Congress and the Administration, as well as cooperation from the PA. For FY2020, Congress has appropriated $75 million in PA security assistance for the West Bank and $75 million in economic assistance for the “humanitarian and development needs of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza.” However, the Trump Administration had previously suggested that restarting U.S. aid for Palestinians could depend on a resumption of PA/PLO diplomatic contacts with the Administration, which may be unlikely in the current U.S.-Israel-Palestinian political climate. Additionally, it is possible that the PA might not accept aid if doing so could be perceived domestically as giving in to U.S. political demands on the peace plan, or as tacitly agreeing to the new triggers of potential PA/PLO liability in PSJVTA.

Implications for personal jurisdiction. The extent to which Congress can provide by statute—such as through ATA—that a foreign entity (in this case, the PA/PLO) is deemed to consent to personal jurisdiction appears to be untested in court. The deemed consent provision in ATA may encounter legal challenges on the basis that it could constitute an unconstitutional condition. A condition attached to government benefits is unconstitutional if it forces the recipient to relinquish a constitutional right that is not reasonably related to the purpose of the benefit. If this concept applies to personal jurisdiction, a reviewing court may need to determine whether submission to jurisdiction has a rational relationship with PA/PLO payments or other PA/PLO activities, such as maintenance of facilities in the United States.

The Palestinians and Amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act: U.S. Aid and Personal Jurisdiction

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction and Issues for Congress

- Amendments to Anti-Terrorism Act

- Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018

- Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019

- Implications for U.S. Policy and Law

- U.S. Aid to Palestinians

- After ATCA

- After PSJVTA

- Personal Jurisdiction

- Looking Ahead: Questions

Summary

Two recent amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2331 et seq.) have significant implications for U.S. aid to the Palestinians and U.S. courts' ability to exercise jurisdiction over Palestinian entities. They are the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253) and the Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019 (PSJVTA, § 903 of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94).

Congress passed ATCA after a U.S. federal lawsuit (known in various incarnations as Waldman v. PLO and Sokolow v. PLO) against the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that an appeals court dismissed in 2016. The trial court had found that the PA and PLO were responsible under ATA (at 18 U.S.C. § 2333) for various terrorist attacks by providing material support to the perpetrators. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that the attacks, "as heinous as they were, were not sufficiently connected to the United States to provide specific personal jurisdiction" in U.S. federal courts.

Amendments to ATA. ATCA provided that a defendant consents to personal jurisdiction in U.S. federal court for lawsuits related to international terrorism if the defendant accepts U.S. foreign aid from any of the three accounts from which U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians has traditionally flowed. In December 2018, the PA informed the United States that it would not accept aid that subjected it to federal court jurisdiction. Consequently, all bilateral aid ended on January 31, 2019.

PSJVTA eliminated a defendant's acceptance of U.S. foreign aid as a trigger of consent to personal jurisdiction—thus partly reversing ATCA—and instead provides that PA/PLO payments related to a terrorist act that kills or injures a U.S. national act as a trigger of consent to personal jurisdiction. The PA/PLO may face strong Palestinian domestic opposition to discontinuing such payments. PSJVTA also directs the State Department to establish a mechanism for resolving and settling plaintiff claims against the PA/PLO. President Trump stated in a signing statement that this provision could interfere with the exercise of his "constitutional authorities to articulate the position of the United States in international negotiations or fora."

Implications of stopping U.S. aid and prospects for resumption. It is unclear to what extent the stop to U.S. security assistance for the PA has affected Israel-PA security cooperation and could affect it in the future. The U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC) said in December 2019 that the suspension of aid had not significantly affected Israel-PA security cooperation, but that the disruption of initiatives aimed at facilitating cooperation and helping reform the PA security sector had some impact on PA acquiescence to USSC requests aimed at reform and greater professionalization.

Even though PSJVTA removed acceptance of U.S. bilateral aid as a trigger for personal jurisdiction, the actual resumption of U.S. aid may depend on political decisions by Congress and the Administration, as well as cooperation from the PA. For FY2020, Congress has appropriated $75 million in PA security assistance for the West Bank and $75 million in economic assistance for the "humanitarian and development needs of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza." However, the Trump Administration had previously suggested that restarting U.S. aid for Palestinians could depend on a resumption of PA/PLO diplomatic contacts with the Administration, which may be unlikely in the current U.S.-Israel-Palestinian political climate. Additionally, it is possible that the PA might not accept aid if doing so could be perceived domestically as giving in to U.S. political demands on the peace plan, or as tacitly agreeing to the new triggers of potential PA/PLO liability in PSJVTA.

Implications for personal jurisdiction. The extent to which Congress can provide by statute—such as through ATA—that a foreign entity (in this case, the PA/PLO) is deemed to consent to personal jurisdiction appears to be untested in court. The deemed consent provision in ATA may encounter legal challenges on the basis that it could constitute an unconstitutional condition. A condition attached to government benefits is unconstitutional if it forces the recipient to relinquish a constitutional right that is not reasonably related to the purpose of the benefit. If this concept applies to personal jurisdiction, a reviewing court may need to determine whether submission to jurisdiction has a rational relationship with PA/PLO payments or other PA/PLO activities, such as maintenance of facilities in the United States.

Introduction and Issues for Congress

This report provides background information and analysis on two amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2331 et seq.): the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253), which became law in October 2018; and the Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019 (PSJVTA, § 903 of P.L. 116-94), which became law in December 2019. The report focuses on the impact of this legislation on the following key issues:

U.S. aid to the Palestinians.

Whether federal courts have personal jurisdiction over the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) for terrorism-related offenses.

Amendments to Anti-Terrorism Act

The ATA generally prohibits acts of international terrorism, including the material support of terrorist acts or organizations.1 It also provides a civil cause of action through which Americans injured by such acts can sue responsible persons or entities for treble damages.2 Prior to ATCA, the ATA did not dictate personal jurisdiction.3

Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018

Congress passed ATCA in the wake of a U.S. federal lawsuit (known in various incarnations as Waldman v. PLO and Sokolow v. PLO) that an appeals court dismissed in 2016.4 The plaintiffs were eleven American families who had members killed or wounded in various attacks against Israeli targets during the second Palestinian intifada (or uprising, which took place between 2000 and 2005).5 The trial court found that the PA and PLO were liable for the attacks because they provided material support to the perpetrators.6 The jury awarded damages of $218.5 million, an amount trebled automatically under the ATA, bringing the total award to $655.5 million.7 On appeal, however, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (Second Circuit) dismissed the suit for lack of personal jurisdiction.8 Discussed in more detail below, personal jurisdiction is the principle that defendants in U.S. courts must have "minimum contacts" to the forum for the court to adjudicate the dispute.9 In Waldman/Sokolow, the Second Circuit concluded that the terrorist attacks, "as heinous as they were, were not sufficiently connected to the United States" to create personal jurisdiction in U.S. federal courts.10

ATCA amended ATA (at 18 U.S.C. § 2334) by, among other things, stating that a defendant consented to personal jurisdiction in U.S. federal court for lawsuits related to international terrorism if the defendant accepted U.S. foreign aid from any of the following three accounts after the law had been in effect for 120 days:11

- Economic Support Fund (ESF);

- International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE); or

- Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR).

Although ATCA's terms do not specifically cite the PA/PLO, ATCA's reference to the three accounts from which U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians has traditionally flowed (see "U.S. Aid to Palestinians" below) suggests that ATCA was responding to the appellate ruling in the Waldman/Sokolow cases on personal jurisdiction.

In December 2018, then-PA Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah wrote to Secretary of State Michael Pompeo that the PA would not accept aid that subjected it to U.S. federal court jurisdiction.12 Consequently, U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians ended on January 31, 2019.13

Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019

In December 2019, Congress passed PSJVTA as § 903 of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94. PSJVTA changes the legal framework by replacing certain provisions in ATCA that triggered consent to personal jurisdiction for terrorism-related offenses.14 These changes include eliminating ATCA's provision triggering consent when a defendant accepts U.S. foreign aid. In place of that provision, PSJVTA provides that the following three actions trigger consent to personal jurisdiction:

- Making payments to individuals imprisoned for terrorist acts against Americans or to families of individuals who died while committing terrorist acts against Americans;15

- Maintaining or establishing any PA/PLO office, headquarters, premises, or other facilities or establishments in the United States;16 or

- Conducting any activity (other than some specified exceptions) on behalf of the PA or PLO while physically present in the United States.17

Unlike ATCA, which did not mention specific Palestinian entities by name, PSJVTA expressly applies its new jurisdictional triggers exclusively to the PA and PLO.18

The prospect of ending PA/PLO payments that could activate the first trigger may encounter strong opposition among Palestinians. Similar payments to Palestinians in connection with alleged terrorist acts continued even after they led to a legal suspension of significant ESF funding for the PA under the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141) when it became effective in March 2018.19 By partly reversing ATCA with respect to the acceptance of aid, PSJVTA could facilitate the resumption of various types of aid, but would still provide for conditions that are reasonably likely to trigger PA/PLO consent to personal jurisdiction, subject to the question of constitutionality.

PSJVTA also directs the State Department to create a claims process for U.S. nationals harmed by terrorist attacks that they attribute to the PA or PLO.20 Under PSJVTA, the Secretary of State, in consultation with the Attorney General, has 30 days from the date of enactment (December 20, 2019) to "develop and initiate a comprehensive process for the Department of State to facilitate the resolution and settlement of covered claims."21 Covered claims are defined to mean pending and successfully completed civil actions against the PA or PLO under the ATA, as well as those lawsuits previously dismissed for lack of personal jurisdiction.22 The Secretary of State has 120 days after enactment to begin meetings with claimants to discuss the state of lawsuits and settlement efforts.23 The Secretary of State has 180 days after enactment to begin negotiations with the PA and PLO to settle covered claims.24 There is no provision withdrawing pending cases from court, however, and jurisdictional provisions applicable before PSJVTA continue to apply to such cases if consent to jurisdiction existed under them.25 The settlement mechanism will apparently operate in tandem with court proceedings.

President Trump stated in a signing statement that the claims process provision in PSJVTA could interfere with the exercise of his "constitutional authorities to articulate the position of the United States in international negotiations or fora."26 He further stated that his Administration would "treat each of these provisions consistent with the President's constitutional authorities with respect to foreign relations, including the President's role as the sole representative of the Nation in foreign affairs."27 To date, CRS does not have information about whether the executive branch has taken steps to create a claims process under PSJVTA.

Implications for U.S. Policy and Law

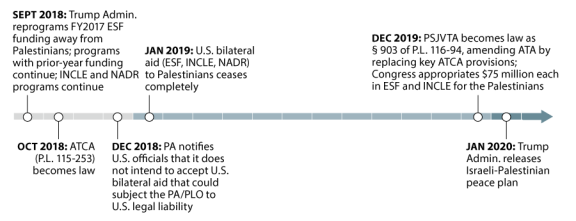

The end of U.S. security assistance and existing economic assistance projects for Palestinians in January 2019, in light of ATCA, has had implications for U.S. policy. The enactment of PSJVTA in December 2019 to partly reverse ATCA and otherwise amend ATA also has policy and legal implications related to U.S. aid and personal jurisdiction over Palestinian entities (see timeline at Figure 1).

|

|

Sources: Various. Note: Acronyms in this figure all have been previously defined in the body of the report. |

U.S. Aid to Palestinians

After ATCA

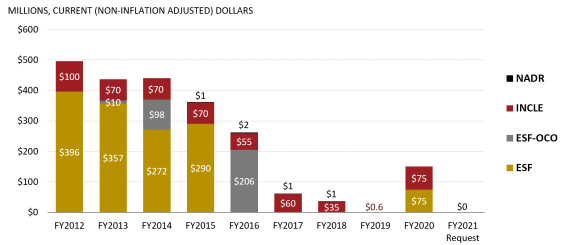

While the Administration made drastic reductions to aid for the Palestinians during 2018,28 the ongoing use of prior-year funding meant that the changes had not affected aid for the PA security forces or existing economic aid projects at the time ATCA took effect. Some sources suggested that the Administration and Congress belatedly realized ATCA's possible impact, and subsequently began considering how to reduce or reverse some of its consequences.29

The end of bilateral aid has halted U.S.-funded programs that began in 1975 with a focus on economic and humanitarian needs, and expanded starting in 1994 (in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process) to assist the newly formed PA with security and Palestinian self-governance.30 The following are changes in status to key aid streams.

- Economic assistance. Although the Trump Administration decided in September 2018 to reprogram all of the FY2017 ESF aid from the West Bank and Gaza to other recipients, some aid projects continued in the West Bank and Gaza using prior-year funding.31 These projects shut down in January 2019. ESF appropriations for the West Bank and Gaza from FY1975 to FY2016 have totaled some $5.26 billion.32

- Security assistance. After the Administration reprogrammed or discontinued various funding streams for the Palestinians during 2018, the main U.S. aid category remaining was the INCLE account. This security assistance account supported nonlethal train-and-equip programs for PA West Bank security forces (PASF). INCLE assistance, along with $1 million per year in NADR assistance, also ended in January 2019 due to ATCA. INCLE appropriations for the PASF from FY2008 to FY2019 have totaled some $919.6 million.33 The office of the U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC, see textbox below) continues to conduct a "security cooperation-only mission" that does not involve funding support, but still facilitates Israel-PA security coordination.34

After ATCA's enactment, the Administration reportedly favored amending ATCA to allow security assistance to continue because of the priority U.S. officials place on Israel-PA security cooperation, which many in Israel also highly value.35 In an October 29, 2019, hearing before the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker said that the Administration was willing to "engage with Congress on every level" to consider ways to revisit or "fix" ATCA to allow the resumption of certain types of aid to Palestinians.

Israeli officials have strongly supported U.S. security assistance as a way to improve PA security capabilities and encourage the PA to coordinate more closely with Israeli security forces.36 Before U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians had ceased, other sources suggested that Israeli officials had reached out to the Administration and Members of Congress in hopes that some arrangement would be able to ensure that U.S. security assistance could continue while also maintaining recourse in U.S. courts against the PA/PLO for past alleged acts of terror.37

It is unclear to what extent the stop to U.S. security assistance for the PA has affected Israel-PA security cooperation and could affect it in the future. One analyst wrote in January 2019 that even without U.S. aid, the PA would have a strong interest in coordinating security with its Israeli counterparts.38 Media reports have routinely suggested that Israel and the PA share a core objective in countering Hamas in the West Bank.39 However, the same analyst wrote that over the long term, "termination of [U.S.-funded programs] in areas like training, logistics, human resources, and equipment provision will undoubtedly have a negative impact on the PASF's overall capabilities and professionalism."40 Another analyst said that without U.S. security aid, the PA will have fewer incentives to continue security cooperation with Israel.41 A spokesman for PA President Mahmoud Abbas responded to the halt in aid by saying it would "have a negative impact on all, create a negative atmosphere and increase instability."42

|

The USSC and INCLE Security Assistance for the PA The U.S. Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority (USSC), established in 2005, is a U.S.-led multilateral mission of more than 50 security specialists from eight NATO countries based in Jerusalem, with a forward post in the West Bank city of Ramallah, where the PA is headquartered.43 The USSC is headed by a three-star U.S. flag officer who leads U.S. efforts to develop and reform the PA security sector. When implementing projects, including those that provide training and equipment to the elements of the PA security forces (PASF), USSC works in coordination with the State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. In synchronizing international supporting efforts for PASF, the USSC works closely with other organizations operating in the region, including the Office of the Quartet and the European Union Coordinating Office for Palestinian Police Support (EUPOL COPPS).44 After more than four years of supporting the PA's recruitment and training of personnel for National Security Forces and Presidential Guard units (2008-2012), the USSC shifted to a less resource intensive, strategic advisory role alongside continuing efforts to use INCLE funds to assist with:

By most accounts, the PASF receiving INCLE support have shown increased professionalism and have helped improve law and order in West Bank cities, despite continuing challenges that stem from squaring Palestinian national aspirations with coordinating security with Israel.45 Within the context of some correlation between USSC efforts and an improved West Bank security situation since 2005 (the end of the second intifada), it is unclear to what extent those efforts and INCLE funding have driven PASF actions and outcomes. In information provided to CRS on December 17, 2019, the USSC stated that, since the suspension of U.S. security assistance in January 2019, USSC has not observed a significant decrease in Israeli-Palestinian security coordination. However, USSC has observed a decrease in the willingness of PASF leadership to acquiesce to U.S. requests regarding Palestinian Security Sector reform. The biggest complication stemming from the cessation of security assistance funds is the suspension of major projects and initiatives designed to improve the professionalism of the Palestinian Security Forces and facilitate their security coordination with the Israelis…. In 2019, violent activity is on a slightly downward trend following a particularly volatile period that closed out 2018 (Ofra Shooting). Yet, the heightened variability in violent activities in the West Bank suggests a gradually increasing level of tension and instability. [It] is unclear [how] the lack of U.S.-funded security assistance contributes to the instability. |

After PSJVTA

Even though PSJVTA removed acceptance of U.S. bilateral aid as a trigger of PA/PLO consent to personal jurisdiction,46 the actual resumption of U.S. aid may depend on political decisions by Congress and the Administration, as well as cooperation from the PA. The conference report for the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), enacted in December 2019, provided the following earmarks:47

- $75 million in INCLE for security assistance in the West Bank for the PA;

- $75 million in ESF for the "humanitarian and development needs of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza."

The conference report said that these funds "shall be made available if the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 is amended to allow for their obligation." The inclusion of PSJVTA in P.L. 116-94 may satisfy that condition.

It is unclear whether the executive branch will implement the aid provisions. The Trump Administration had previously suggested that restarting U.S. aid for Palestinians could depend on a resumption of PA/PLO diplomatic contacts with the Administration.48 Such a resumption of diplomacy may be unlikely in the current U.S.-Israel-Palestinian political climate,49 particularly following the January 2020 release of a U.S. peace plan that the PA/PLO strongly opposes.50 Additionally, under its terms, the Taylor Force Act would preclude any ESF deemed to directly benefit the PA.51 The Administration's omission of any bilateral assistance—security or economic—for the West Bank and Gaza in its FY2021 budget request, along with its proposal in the request for a $200 million Diplomatic Progress Fund ($25 million in security assistance and $175 million in economic) to support future diplomatic efforts, may potentially convey some intent by the Administration to condition aid to Palestinians on PA/PLO political engagement with the U.S. peace plan.52

Additionally, it is unclear whether the PA would cooperate with a U.S. effort to provide aid to Palestinians given U.S.-Palestinian political tensions and the way that PSJVTA amended ATA. Even if accepting aid would no longer potentially trigger PA/PLO liability in U.S. courts, it is possible that—given PA concerns about national dignity—the PA might not accept aid if doing so could be perceived domestically as giving in to U.S. political demands on the peace plan, or as tacitly agreeing to the new triggers of potential PA/PLO liability in PSJVTA (see "Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019" above).

If the executive branch and the PA agree on the resumption of aid, it is unclear how the economic portion of aid would specifically address humanitarian and development needs in the West Bank and Gaza. In the October 29, 2019, committee hearing mentioned above, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Assistant Administrator for Middle East Affairs Michael Harvey was asked what type of aid should be given priority. Harvey said that, without prejudging, if the political decision were made to resume ESF assistance, water and wastewater projects have historically been key objectives, and thus could be places to start.

Personal Jurisdiction

One of the aims of the amendments to ATA described above is to enhance personal jurisdiction over defendants accused of carrying out terrorist attacks that injure U.S. nationals. To try any civil case, U.S. courts must have both subject matter jurisdiction and personal jurisdiction over the defendant. ATA provides for subject matter jurisdiction by providing a cause of action for U.S. nationals injured by applicable acts of terrorism.53 However, for a court to exercise personal jurisdiction over the defendant, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment must be satisfied.54 Due process requires that the defendant have sufficient "minimum contacts" in the forum adjudicating the lawsuit such that the maintenance of the suit there does not offend "traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice."55

Foreign entities, including foreign political but non-sovereign entities such as the PA and PLO, are entitled to due process and can challenge a court's jurisdiction based on a lack of personal jurisdiction.56 Under the doctrine of general personal jurisdiction, a foreign entity can be sued for virtually any matter without regard to the nature of its contacts with the forum state.57 The Supreme Court has held that, for courts to exercise general personal jurisdiction, a defendant entity must have enough operations in that state to be essentially "at home" there.58 When general jurisdiction is not available, maintenance of a lawsuit against a foreign defendant requires specific personal jurisdiction. Specific jurisdiction exists where there is a significant relationship among the defendant, the forum, and the subject matter of the litigation.59 Based on this test, ATA lawsuits against the PA and PLO have failed for want of specific personal jurisdiction.60

Personal jurisdiction can be waived61 and litigants can consent to personal jurisdiction that might otherwise be lacking.62 But the extent to which Congress can provide by statute that a foreign entity is deemed to consent to personal jurisdiction by making payments or through the maintenance of facilities in the United States appears to be untested.63 Plaintiffs' efforts to obtain personal jurisdiction over the PA and PLO based on the criteria provided in ATCA, including acceptance of foreign aid and the maintenance of facilities in the United States, failed because plaintiffs could not prove that any of the criteria had been met, obviating the need for the courts to address ATCA's constitutionality.64

The new deemed consent provisions in PSJVTA may encounter challenges in court on the basis that they could constitute an unconstitutional condition on permission to operate in the United States.65 A condition attached to government benefits is unconstitutional if it forces the recipient to relinquish a constitutional right that is not reasonably related to the purpose of the benefit.66 If this concept applies to personal jurisdiction,67 a reviewing court may need to determine whether submission to such jurisdiction is either voluntary or has a rational relationship with PA/PLO payments or other PA/PLO activities, including maintenance of facilities in the United States. On the other hand, because ATA is a federal foreign affairs-related statute, Congress may have greater leeway to establish jurisdiction based on deemed consent.68

Looking Ahead: Questions

Responses to the following questions could have important implications for U.S. policy and law.

- Given that acceptance of aid no longer triggers consent to personal jurisdiction, will the PA cooperate with the implementation of U.S. security and economic aid that Congress appropriated in December 2019 for FY2020 for the West Bank and Gaza?

- Will the Trump Administration provide the appropriated FY2020 security and economic aid to Palestinians? If so, when?

- What are the effects of the cutoff—since January 2019—of U.S. aid to the West Bank and Gaza? Depending on the timing and other circumstances surrounding a possible resumption of aid, what effects could an aid resumption have?

- Will the PA/PLO stop payments to prisoners accused of terrorist acts against Americans (or payments to the prisoners' families) in order to avoid being deemed to consent to personal jurisdiction under PSJVTA?

- If PSJVTA's provisions on PA/PLO consent to personal jurisdiction are challenged in court, will they be upheld as constitutional?

- Will the Trump Administration comply with the requirement in PSJVTA for the State Department to establish a process for resolving and settling claims against the PA/PLO under ATA? If so, what would the process look like and what outcomes would it produce?

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

P.L. 101-519 § 132, codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. §§ 2331-39D. |

| 2. |

18 U.S.C. § 2333. |

| 3. |

Id. § 2334 (2018). |

| 4. |

H.Rept. 115-858, at 6-8 (explaining rationale for linking acceptance of foreign aid to jurisdiction in U.S. courts). See also Greg Stohr, "U.S. Supreme Court Won't Make PLO Pay $656 Million Terror Award," Bloomberg, April 2, 2018. |

| 5. |

Waldman v. Palestine Liberation Organization, 835 F.3d 317, 322 (2d Cir. 2016), cert. denied sub nom. Sokolow v. Palestine Liberation Organization, 138 S. Ct. 1438 (2018). The text of the court decision is available at https://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/16-1071-op-bel-2d-cir.pdf. |

| 6. |

The PLO is the internationally recognized representative of the Palestinian people. Various Israel-PLO agreements during the Oslo process in the 1990s created the PA as the organ of governance for limited Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Officially, the PLO represents the Palestinian national movement in international bodies, including the United Nations, often using the moniker "Palestine" or "State of Palestine." Because Mahmoud Abbas is both PLO chairman and PA president, U.S. officials and other international actors sometimes conflate his roles. For more information on the two entities, see the European Council on Foreign Relations' online resource Mapping Palestinian Politics at https://www.ecfr.eu/mapping_palestinian_politics/detail/institutions. |

| 7. |

Waldman, 835 F.3d at 322. |

| 8. |

Id. at 377. |

| 9. |

See International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316 (1945). |

| 10. |

Waldman, 835 F.3d at 377. |

| 11. |

Under ATCA, consent to personal jurisdiction was also triggered by continued operation or establishment of new facilities in the United States otherwise permitted by a waiver of the prohibitions set forth in 22 U.S.C. § 5202, which generally prohibits the PLO to operate facilities in the United States. |

| 12. |

Letter accessible at Shalom Lipner, "US pressure on the Palestinians must not come at the cost of security," atlanticcouncil.org, January 25, 2019. |

| 13. |

Yolande Knell, "US stops all aid to Palestinians in West Bank and Gaza," BBC News, February 1, 2019. |

| 14. |

18 U.S.C. § 2334(e)(5) (as added). |

| 15. |

Id. § 2334(e)(1)(A) (as amended). This provision applies 120 days after enactment of the PSJVTA. Id. |

| 16. |

Id. § 2334(e)(1)(B)(i-ii) (as amended). This provision applies 15 days after enactment of the PSJVTA. Id. Since late 2018, the PLO has not maintained a representative office in the United States. |

| 17. |

Id. § 2334(e)(1)(B)(iii) and (e)(3) (as amended). This provision applies 15 days after enactment of PSJVTA. Id. § 2334(e)(1)(B)(iii) (as amended). |

| 18. |

18 U.S.C. § 2334(e)(5) (as added). |

| 19. |

For more information on the Taylor Force Act, see CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 20. |

P.L. 116-94 § 903(b). |

| 21. |

Id. § 903(b)(1). |

| 22. |

Id. § 903(b)(5). The cases must have been pending on or after August 30, 2016. Id. § 903(d)(2). |

| 23. |

Id. § 903(b)(2)(B). |

| 24. |

Id. § 903(b)(2)(C). |

| 25. |

Id. § 903(c)(2) (prior consent not abrogated). There do not appear to be any cases in which consent was found based on the ATCA provision. |

| 26. |

Statement by the President on Signing the "Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020," Dec. 20, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-by-the-president-32/. |

| 27. |

Id. The President also protested the provision requiring progress reports to Congress, stating that his Administration would treat it and other such provisions "consistent with the President's constitutional authority to control the disclosure of information that could impair foreign relations, national security, law enforcement, the deliberative processes of the executive branch, or the performance of the President's constitutional duties, and to supervise communications by Federal officers and employees related to their official duties, including in cases where such communications would be unlawful or could reveal confidential information protected by executive privilege." Id. |

| 28. |

See CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 29. |

Matthew Lee, "In a twist, Trump fights to keep some Palestinian aid alive," Associated Press, November 30, 2018; Scott R. Anderson, "Congress Has (Less Than) 60 Days to Save Israeli-Palestinian Security Cooperation," Lawfare Blog, December 7, 2018. |

| 30. |

See CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. Prior to the establishment of limited Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza, approximately $170 million in U.S. developmental and humanitarian assistance (not including contributions to UNRWA) were obligated for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza from 1975-1993, mainly through nongovernmental organizations. CRS Report 93-689 F, West Bank/Gaza Strip: U.S. Foreign Assistance, by Clyde R. Mark, July 27, 1993, available to congressional clients on request to Jim Zanotti. |

| 31. |

Information on ESF projects that received funding from prior-year appropriations during the early part of FY2019 is available at USAID's Foreign Aid Explorer portal, listed under 2019 disbursements for West Bank/Gaza. Key project sectors included water supply and sanitation, emergency humanitarian needs, community infrastructure, basic education, civil society, and economic development. |

| 32. |

Total aid estimate is approximated from congressional appropriation amounts and information from the State Department and USAID. |

| 33. |

Total aid estimate is approximated from congressional appropriation amounts and information from the State Department and USAID. |

| 34. |

Tovah Lazaroff, et al., "U.S. funding for Palestinian security services ends," jpost.com, January 31, 2019. |

| 35. |

Ibid. |

| 36. |

Bryant Harris, "Congress in no hurry to act as Palestinians reject security aid," Al-Monitor, January 22, 2019. |

| 37. |

Ron Kampeas, "Israel working with Trump administration to get U.S. money to Palestinian security services," Jewish Telegraphic Agency, January 24, 2019. See also Michael Bachner, "Israel said pushing US to amend law that threatens security coordination with PA," Times of Israel, January 24, 2019. |

| 38. |

Neri Zilber, "Now Trump's Shutdown Threatens Israel's Security," Daily Beast, January 22, 2019. |

| 39. |

Anshel Pfeffer, "Israel quietly lobbying to sustain Palestinian security funding in the West Bank," Jewish Chronicle, February 5, 2019. |

| 40. |

Zilber, op. cit. footnote 38. |

| 41. |

Jihad Harb, quoted in Adam Rasgon, "As new anti-terrorism law goes into effect, PA says it'll stop accepting US aid," Times of Israel, January 20, 2019. |

| 42. |

Michael Wilner and Tovah Lazaroff, "Trump team says PA wants to skirt U.S. courts," jpost.com, February 2, 2019. |

| 43. |

Factsheets provided by the USSC to CRS, February 12, 2020. The core of the USSC is made up of U.S. military officers hosted by the State Department. Supporting contingents of security specialists from the United Kingdom and Canada work with the U.S. core team, as do smaller contingents from the Netherlands, Turkey, Italy, Poland, and Bulgaria. |

| 44. |

USSC web portal at https://www.state.gov/about-us-united-states-security-coordinator-for-israel-and-the-palestinian-authority/. The Office of the Quartet (the Quartet is the United Nations, European Union, United States, and Russia) has a mandate to assist Palestinian economic and institutional development. Website: http://www.quartetoffice.org/. EUPOL COPPS website: https://eupolcopps.eu/. |

| 45. |

CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 46. |

See "Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019" for information on the PSJVTA triggers that replaced ATCA's trigger of accepting U.S. bilateral aid. |

| 47. |

Text of conference report available at https://appropriations.house.gov/sites/democrats.appropriations.house.gov/files/HR%201865%20-%20Division%20G%20-%20SFOPs%20SOM%20FY20.pdf. |

| 48. |

Barak Ravid, "Trump told officials that Netanyahu should pay security aid to Palestinians," Axios, November 6, 2019. |

| 49. |

CRS Report R44245, Israel: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief, by Jim Zanotti; CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 50. |

Colum Lynch and Robbie Gramer, "Trump Pressures Palestinians and Allies over Peace Plan," foreignpolicy.com, February 11, 2020. |

| 51. |

CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 52. |

See footnote 50; Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2021, stating (at p. 77), "The creation of this fund sends a clear signal that additional support from the United States can be made available for governments that choose to engage positively to advance peace and/or shared diplomatic goals." |

| 53. |

18 U.S.C. § 2333(a) provides a civil action for U.S. nationals injured "by reason of an act of international terrorism...." Id. The term "international terrorism" is defined as activities that: (A) involve violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State, or that would be a criminal violation if committed within the jurisdiction of the United States or of any State; (B) appear to be intended-- (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and (C) occur primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States, or transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to intimidate or coerce, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or seek asylum.... 18 U.S.C. § 2331(1). |

| 54. |

Federal courts ordinarily follow state law in determining the bounds of their jurisdiction over persons, Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U.S. 117, 125 (2014) (citing Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 4(k)(1)(A)), which implicates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, when the lawsuit involves a federal question, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment instead may be implicated, which could provide a different test. See Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California, San Francisco Cty., 137 S. Ct. 1773, 1783–84 (2017) (leaving open whether the Fifth Amendment imposes the same restrictions on the exercise of personal jurisdiction by a federal court as apply to state jurisdiction under the Fourteenth Amendment (citing Omni Capital Int'l, Ltd. v. Rudolf Wolff & Co., 484 U.S. 97, 102 n.5 (1987))). |

| 55. |

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 316 (1945). |

| 56. |

See, e.g., Waldman v. Palestine Liberation Organization, 835 F.3d 317, 329 (2d Cir. 2016), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 1438 (2018). |

| 57. |

For additional background on types of personal jurisdiction and their relationship with the Due Process Clause, see CRS Report R44957, Due Process Limits on the Jurisdiction of Courts: Issues for Congress, by Brandon J. Murrill. |

| 58. |

Daimler, 571 U.S. at 374 ("A court may assert general jurisdiction over foreign (sister-state or foreign-country) corporations to hear any and all claims against them when their affiliations with the State are so 'continuous and systematic' as to render them essentially at home in the forum State." (quoting Goodyear Dunlop Tires Operations, S.A. v. Brown, 564 U.S. 915, 919 (2011))). Applying the Daimler test, courts have found that the PA and PLO did not have sufficiently continuous and systematic affiliations with the forum state to support jurisdiction. See Waldman, 835 F.3d at 332–33 ("As the District Court for the District of Columbia observed, '[i]t is common sense that the single ascertainable place where a government such a[s] the Palestinian Authority should be amenable to suit for all purposes is the place where it governs. Here, that place is the West Bank, not the United States…The same analysis applies equally to the PLO, which during the relevant period maintained its headquarters in Palestine and Amman, Jordan.") (citations omitted); Estate of Klieman v. Palestinian Auth., 82 F. Supp. 3d 237, 245 (D.D.C. 2015) ("Defendants' activities in the United States represent a tiny fraction of their overall activity during the relevant time period, and are a smaller proportion of their overall operations than Daimler's California–based contacts."), aff'd sub nom. Estate of Klieman by & through Kesner v. Palestinian Auth., 923 F.3d 1115 (D.C. Cir. 2019). |

| 59. |

Waldman, 855 F.3d at 355 ("For a State to exercise jurisdiction consistent with due process, the defendant's suit-related conduct must create a substantial connection with the forum State."). |

| 60. |

See id. at 337 ("While the killings and related acts of terrorism are the kind of activities that the ATA proscribes, those acts were unconnected to the forum and were not expressly aimed at the United States. And '[a] forum State's exercise of jurisdiction over an out-of-state intentional tortfeasor must be based on intentional conduct by the defendant that creates the necessary contacts with the forum.'" (quoting Walden v. Fiore, 571 U.S. 277, 285 (2014)); Safra v. Palestinian Auth., 82 F. Supp. 3d 37, 51 (D.D.C. 2015) (finding "insufficient links between the specific acts underlying th[e] action and the United States to support specific jurisdiction"), aff'd sub nom. Livnat v. Palestinian Auth., 851 F.3d 45 (D.C. Cir. 2017); Estate of Klieman, 82 F. Supp. at 246 ("If the activities giving rise to the suit occurred abroad, jurisdiction is proper only if the defendant has 'purposefully directed' its activities towards the forum and if defendant's 'conduct and connection with the forum State are such that he should reasonably anticipate being haled into court there.'" (citing Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462, 472, 474 (1985); Williams v. Romarm, SA, 756 F.3d 777, 784, 786–87 (D.C. Cir.2014)). Some earlier cases in which courts applied a less stringent test found that personal jurisdiction did exist, Biton v. Palestinian Interim Self-Gov't Auth., 310 F. Supp. 2d 172, 179 (D.D.C. 2004) (holding that the PA "appears to have sufficient contacts with the United States to satisfy due process concerns"); Estates of Ungar ex rel. Strachman v. Palestinian Auth., 153 F. Supp. 2d 76, 88 (D.R.I. 2001) (finding PA and PLO have sufficient minimum contacts with the United States as a whole to support personal jurisdiction consistent with the Fifth Amendment). |

| 61. |

See, e.g., Gilmore v. Palestinian Interim Self-Gov't Auth., 843 F.3d 958, 964 (D.C. Cir. 2016) (noting that it is "elementary" that defendants can waive personal jurisdiction and concluding that the PA and PLO waived their challenges to personal jurisdiction by not raising the defense at the outset), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 88 (2017). |

| 62. |

Ins. Corp. of Ireland v. Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinee, 456 U.S. 694, 703–04 (1982) (noting that many legal means have been taken to represent express or implied consent to personal jurisdiction, including by contract in advance, by stipulation, agreements to arbitrate, and state procedures that find constructive consent through the voluntary use of certain state procedures). |

| 63. |

Given the Supreme Court's opinions in Goodyear and Daimler, some federal courts have been reluctant to find implicit consent to personal jurisdiction based solely on corporations' registration to do business in a state. See, e.g., Waite v. All Acquisition Corp., 901 F.3d 1307, 1318 (11th Cir. 2018) ("After Daimler, there is 'little room' to argue that compliance with a state's 'bureaucratic measures' render a corporation at home in a state." (citation omitted)), cert. denied sub nom. Waite v. Union Carbide Corp., 139 S. Ct. 1384 (2019); AM Tr. v. UBS AG, 681 F. App'x 587, 588 (9th Cir. 2017) ("It is an open question whether, after Daimler, a state may require a corporation to consent to general personal jurisdiction as a condition of registering to do business in the state."); Brown v. Lockheed Martin Corp., 814 F.3d 619, 638-39 (2d Cir. 2016) (holding that Goodyear and Daimler foreclosed establishing personal jurisdiction by implied consent through statutorily required corporate registration as had been permissible under Pennsylvania Fire Insurance Co. of Philadelphia v. Gold Issue Mining & Milling Co., 243 U.S. 93 (1917)). But see Acord Therapeutics, Inc. v. Mylan Pharm. Inc., 78 F. Supp. 3d 572, 584 (D. Del. 2015) (holding that an out-of-state corporation had consented to general personal jurisdiction by registering to do business in Delaware), aff'd on other grounds, 817 F.3d 755 (Fed. Cir. 2016), cert. denied 137 S. Ct. 625 (2017). No federal appellate court has yet addressed whether a state statute is constitutional if it expressly conditions consent to personal jurisdiction on registration to do business in the state. District courts appear to be divided. Compare In re Asbestos Products Liability Litigation (No. VI), 384 F. Supp. 3d 532, 542 (E.D. Pa. 2019) (finding Pennsylvania statute conferring jurisdiction over corporations that register to be unconstitutional), with Gorton v. Air & Liquid Sys. Corp., 303 F. Supp. 3d 278, 298 (M.D. Pa. 2018) (finding that pursuant to Pennsylvania statute, "a corporation that applies for and receives a certificate of authority to do business in Pennsylvania consents to the general jurisdiction of state and federal courts in Pennsylvania"), and Bors v. Johnson & Johnson, 208 F. Supp. 3d 648, 653 (E.D. Pa. 2016) ("The ruling in Daimler does not eliminate consent to general personal jurisdiction over a corporation registered to do business in Pennsylvania."). |

| 64. |

See Waldman v. Palestine Liberation Org., 925 F.3d 570, 574 (2d Cir. 2019) (declining to reopen earlier dismissed lawsuit based on ATCA because the plaintiffs did not show that either factual predicate of Section 4 of ATCA had been satisfied), petition for cert. filed, (Dec 16, 2019) (No. 19-764); Estate of Klieman, 923 F.3d at 1128 (holding that because plaintiffs had not shown ATCA criteria had been met, ATCA "does not affect our analysis of personal jurisdiction, and we need not reach the defendants' constitutional challenges"), petition for cert. filed, (Dec 11, 2019) (No. 19-741). |

| 65. |

Cf. Supplemental Brief of Defendants-Appellees in Response to the Amicus Curiae Brief of the United States, Estate of Klieman v. Palestinian Auth., 923 F.3d 1115 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (No. 15-7034), 2019 WL 1399559 at *9 ("[B]ecause it coerces the surrender of Defendants' jurisdictional due process protections, ATCA Section 4 imposes an unconstitutional condition on benefits - financial aid, a Section 1003 waiver - that the United States might choose to offer."). |

| 66. |

See Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374, 385 (1994) ("Under the well-settled doctrine of 'unconstitutional conditions,' the government may not require a person to give up a constitutional right... in exchange for a discretionary benefit conferred by the government where the benefit sought has little or no relationship to the property" (citing Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593 (1972); Pickering v. Board of Ed. of Township High School Dist. 205, Will Cty., 391 U.S. 563, 568 (1968)); Nat'l Amusements, Inc. v. Town of Dedham, 43 F.3d 731, 747 (1st Cir. 1995) (opining that if a condition is sufficiently related to the benefit, it may validly be imposed), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1103 (1995). |

| 67. |

In re Asbestos Products, 384 F. Supp. at 542 (applying doctrine of unconstitutional conditions to a Pennsylvania statutory business registration scheme's conferral of consent to general personal jurisdiction in exchange for ability to do business in Pennsylvania). |

| 68. |

See Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae, Estate of Klieman v. Palestinian Auth., 923 F.3d 1115 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (No. 15-7034), 2019 WL 1200589 at *16 (arguing that "in light of [its] foreign affairs and national security context, Section 4 [of ATCA] is entitled to deference in a way that state consent-by-registration statutes are not" (citing Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, 561 U.S. 1, 35-36 (2010)). |