U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians

In calendar year 2018, the Trump Administration has significantly cut funding for the Palestinians during a time of tension in U.S.-Palestinian relations. Statements by President Trump suggest that the Administration may seek via these cuts to persuade the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to participate in U.S.-led diplomacy on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Despite the funding cuts, PLO Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas and other PLO/PA officials have not reversed their decision to break off diplomatic contacts with the United States, which came after President Trump’s December 2017 recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Various observers are debating what the Administration wants to accomplish via the U.S. funding cuts, and how compatible its actions are with U.S. interests. Some Members of Congress have objected to the cuts, including on the grounds that they could negatively affect a number of humanitarian outcomes, especially in Hamas-controlled Gaza. Some current and former Israeli security officials have reportedly voiced concerns about the effects of drastic U.S. cuts on regional stability.

Until this year, the U.S. government had consistently supported economic assistance to the Palestinians and humanitarian contributions to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), even if funding in some cases was reduced or delayed. Bilateral assistance to the Palestinians since 1994 has totaled more than $5 billion, and has been a key part of U.S. policy to encourage an Israeli-Palestinian peace process, improve life for West Bank and Gaza residents, and (since 2007) strengthen the West Bank-based PA vis-à-vis Hamas in Gaza. U.S. contributions to UNRWA through global humanitarian accounts since 1950 have totaled more than $6 billion.

The 2018 changes raise questions about the future of various funding streams and U.S. political influence, as well as the impact on other international actors’ support of and influence on the Palestinians. Congress has options to determine types and amounts of funding for the Palestinians and to place conditions or oversight requirements on it.

The 2018 changes included

Reprogramming $231.532 million of FY2017 bilateral economic assistance that was originally intended for the West Bank and Gaza (including $25 million for East Jerusalem hospitals) for other purposes.

Ending U.S. humanitarian contributions to UNRWA. U.S. funding in FY2018 totaled $65 million, contrasted with $359.3 million in FY2017.

Deciding to prevent Palestinians from participating in a Conflict Management and Mitigation program (CMM) funded by USAID and the U.S. embassy in Israel. Programs involving Israelis and Palestinians generally receive $10 million annually.

Nonlethal U.S. security assistance for the PA security forces has continued, as has PA security coordination with Israel, but a majority of Palestinians support recent PLO recommendations to end the coordination.

Legislation enacted in 2018 is also significantly impacting U.S. aid to the Palestinians. Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141) in March. This law augmented existing legislative provisions to suspend U.S. bilateral economic assistance for the PA unless and until Palestinian officials cease certain payments deemed under U.S. law to be “for acts of terrorism.” The Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ACTA, P.L. 115-253) became law in October, as an apparent way to ensure that the PLO and PA would be subject to jurisdiction in U.S. courts for past acts of Palestinian terrorism against U.S. citizens. Because the ATCA attempts to use U.S. aid to Palestinians as a means of establishing this jurisdiction, and Palestinian leaders apparently want to avoid that outcome, the ATCA might indirectly lead to a complete end of U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians by February 2019. The Trump Administration may not have realized the possible impact of the ATCA when it was enacted, and reportedly may be trying to have Congress change the ATCA to facilitate the continuation of security assistance, at least.

U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview: Changes in U.S. Funding for Palestinians

- 2018 Administration Actions

- Reprogramming FY2017 Bilateral ESF

- Changing the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Management and Mitigation Program

- Ending U.S. Contributions to UNRWA

- Continuing Security Assistance

- Assessment

- Political Strategy and Leverage

- The Changes' Direct Impact

- 2018 Legislation

- Taylor Force Act: No ESF That "Directly Benefits" the PA

- Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018: Possible Complete End to Bilateral Aid

- Options for Congress

- FY2019 Appropriations Legislation

- UNRWA-Related Bills

- Palestinian Partnership Fund Act (S. 3549 and H.R. 7060)

Summary

In calendar year 2018, the Trump Administration has significantly cut funding for the Palestinians during a time of tension in U.S.-Palestinian relations. Statements by President Trump suggest that the Administration may seek via these cuts to persuade the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to participate in U.S.-led diplomacy on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Despite the funding cuts, PLO Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas and other PLO/PA officials have not reversed their decision to break off diplomatic contacts with the United States, which came after President Trump's December 2017 recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital.

Various observers are debating what the Administration wants to accomplish via the U.S. funding cuts, and how compatible its actions are with U.S. interests. Some Members of Congress have objected to the cuts, including on the grounds that they could negatively affect a number of humanitarian outcomes, especially in Hamas-controlled Gaza. Some current and former Israeli security officials have reportedly voiced concerns about the effects of drastic U.S. cuts on regional stability.

Until this year, the U.S. government had consistently supported economic assistance to the Palestinians and humanitarian contributions to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), even if funding in some cases was reduced or delayed. Bilateral assistance to the Palestinians since 1994 has totaled more than $5 billion, and has been a key part of U.S. policy to encourage an Israeli-Palestinian peace process, improve life for West Bank and Gaza residents, and (since 2007) strengthen the West Bank-based PA vis-à-vis Hamas in Gaza. U.S. contributions to UNRWA through global humanitarian accounts since 1950 have totaled more than $6 billion.

The 2018 changes raise questions about the future of various funding streams and U.S. political influence, as well as the impact on other international actors' support of and influence on the Palestinians. Congress has options to determine types and amounts of funding for the Palestinians and to place conditions or oversight requirements on it.

The 2018 changes included

- Reprogramming $231.532 million of FY2017 bilateral economic assistance that was originally intended for the West Bank and Gaza (including $25 million for East Jerusalem hospitals) for other purposes.

- Ending U.S. humanitarian contributions to UNRWA. U.S. funding in FY2018 totaled $65 million, contrasted with $359.3 million in FY2017.

- Deciding to prevent Palestinians from participating in a Conflict Management and Mitigation program (CMM) funded by USAID and the U.S. embassy in Israel. Programs involving Israelis and Palestinians generally receive $10 million annually.

- Nonlethal U.S. security assistance for the PA security forces has continued, as has PA security coordination with Israel, but a majority of Palestinians support recent PLO recommendations to end the coordination.

Legislation enacted in 2018 is also significantly impacting U.S. aid to the Palestinians. Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141) in March. This law augmented existing legislative provisions to suspend U.S. bilateral economic assistance for the PA unless and until Palestinian officials cease certain payments deemed under U.S. law to be "for acts of terrorism." The Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act (ACTA, P.L. 115-253) became law in October, as an apparent way to ensure that the PLO and PA would be subject to jurisdiction in U.S. courts for past acts of Palestinian terrorism against U.S. citizens. Because the ATCA attempts to use U.S. aid to Palestinians as a means of establishing this jurisdiction, and Palestinian leaders apparently want to avoid that outcome, the ATCA might indirectly lead to a complete end of U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians by February 2019. The Trump Administration may not have realized the possible impact of the ATCA when it was enacted, and reportedly may be trying to have Congress change the ATCA to facilitate the continuation of security assistance, at least.

Overview: Changes in U.S. Funding for Palestinians

U.S. aid to the Palestinians has changed more dramatically in calendar year 2018 than at any time since 2007, when it was restructured to respond to the takeover of the Gaza Strip by the Sunni Islamist group Hamas (for more background, see Appendix A).1 The Trump Administration has taken several steps to reduce U.S. funding for programs benefitting Palestinians. The President's statements suggest that the Administration may seek to persuade the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to participate in U.S.-led diplomacy on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process (see "2018 Administration Actions" below). PLO Chairman and Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas broke off diplomatic contacts with the Administration in December 2017 after President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announced his intention to relocate the U.S. embassy there from Tel Aviv.

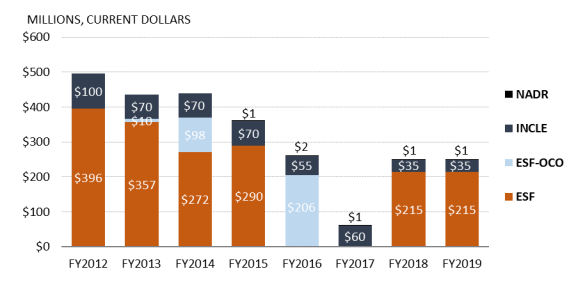

In August and September 2018, the Administration announced that it would reprogram at least $225 million of FY2017 bilateral economic aid initially allocated for the West Bank and Gaza (from the Economic Support Fund, or ESF, account, including some amounts designated as ESF-Overseas Contingency Operations, or ESF-OCO). The amounts reprogrammed are estimated to be $231.542 million (see "Reprogramming FY2017 Bilateral ESF" below). Also in September, the Administration announced that it was ending all U.S. humanitarian contributions to the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Bilateral, nonlethal security assistance from the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) account is the only major stream of U.S. funding to the Palestinians that has continued unabated. This assistance helps train and equip PA security forces and officials from the PA's justice sector.

The Administration's actions regarding FY2017 ESF have raised questions about future-year funding (including FY2018 and FY2019) for the Palestinians, such as whether existing aid programs will continue. Media reports suggest that many of the organizations that have implemented ESF programs in the West Bank and Gaza are suspending or preparing to suspend operations unless funding resumes.2 The status of ESF programs and of UNRWA's operations could affect the region's security and its economic and humanitarian situations. The Administration's actions also have sparked debate over how cuts in U.S. bilateral and multilateral assistance will affect U.S. political leverage with the Palestinians (see "Political Strategy and Leverage" below), and whether other countries will step in to replace U.S. funding and—potentially—U.S. influence.

Regardless of the Administration's actions in 2018, it is unclear how much FY2017 ESF would have been available for the Palestinians. Congress suspended all ESF that "directly benefits" the PA in March via the Taylor Force Act (Title X of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, or P.L. 115-141). In October, U.S. government officials clarified that they would have been legally required to withhold $165 million in FY2017 ESF even if the Administration had not reprogrammed the entire $231.542 million.3 The same requirement to suspend ESF will apply to future-year funding unless and until Palestinian governing entities stop payments to individuals imprisoned for or killed while allegedly committing acts of terrorism, or to these individuals' families.

Some reports have suggested that the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253), which became law in October 2018, could indirectly lead to a complete end of U.S. bilateral aid for the Palestinians absent further congressional action (see "Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018: Possible Complete End to Bilateral Aid").

2018 Administration Actions

Changes in U.S. policy on various types of funding for the Palestinians have unfolded throughout 2018. In an August 28 press briefing, the State Department spokesperson said

Earlier this year…the President directed an overall review of U.S. assistance to the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and also in Gaza….

The decision was then made, and we sent out a statement to this effect [on August 24], that that money at this time is not in the best interests of the U.S. national interest and also at this time does not provide value to the U.S. taxpayer.

Various statements from President Trump, as well as observations from other sources, suggest that U.S. actions on aid may seek to persuade the Palestinians to participate in U.S.-led diplomacy on the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. In January 2018, shortly after PLO Chairman Abbas broke off diplomatic contacts with the United States in response to its new policy on Jerusalem, President Trump said that the hundreds of millions of dollars of aid that Palestinians receive "is not going to them unless they sit down and negotiate peace." In September, President Trump said that he stopped "massive amounts of money that we were paying to the Palestinians" and that the United States would not resume payments "until we make a deal."4 Later in September, an article examining U.S. aid policy toward the Palestinians stated

The broad push to cut all funding to Palestinian civilians is promoted by Jared Kushner, the son-in-law of President Trump and the top White House adviser on the Middle East. Mr. Kushner has been working on a peace proposal for the Israelis and Palestinians, and is seeking maximum negotiating leverage over the Palestinians.5

For more on this topic, see "Political Strategy and Leverage" below.

Reprogramming FY2017 Bilateral ESF

The Administration appears to have reprogrammed all FY2017 bilateral economic aid originally intended for the West Bank and Gaza. Based on congressional notifications it made in September 2018, USAID reprogrammed an estimated $231.542 million of ESF (including some designated as ESF-OCO) from the West Bank and Gaza for other purposes.6 To use the funds, USAID was required to obligate them by the end of FY2018 (September 30, 2018). Pursuant to an August 24 statement, a State Department official said that the President directed the reprogramming of $200 million in FY2017 ESF to "high-priority projects elsewhere."7 On September 8, a State Department official announced a similar reprogramming of approximately $25 million originally planned for the East Jerusalem Hospital Network.8

Changing the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Management and Mitigation Program

Additionally, in September, executive and legislative branch sources disclosed the Administration's decision to bar Palestinians from participating in a Conflict Management and Mitigation program (CMM) funded by USAID and the U.S. embassy in Israel.9 According to Section 7060(g) of P.L. 115-141, CMM's funds (which come from either the ESF or the Development Assistance accounts) are intended to "support people-to-people reconciliation programs which bring together individuals of different ethnic, religious, and political backgrounds from areas of civil strife and war."

According to media reports, $10 million of $26 million allocated by the Administration for CMM in FY2017 had initially been set aside for initiatives involving Israeli Jews—either with Palestinians from the West Bank or with Arab citizens of Israel.10 The Administration's September decision reportedly halted the awarding of new grants for initiatives involving West Bank Palestinians. A congressional aide was quoted as saying that USAID "decided to support programs that involve Israeli Jews and Israeli Arabs" to avoid having the Israel-based part of the program shut down.11 Congress began funding Israeli-Palestinian CMM projects in FY2004,12 and up through FY2012 had annually earmarked $10 million for initiatives in the Middle East.13 Some former U.S. officials have expressed concern that the program changes will reduce U.S. influence and credibility in the region.14

|

Current and Recent Israeli-Palestinian CMM Initiatives According to a 2017 USAID factsheet, the CMM program provides Jewish and Arab Israelis, Palestinians, and some others "opportunities to address issues, reconcile differences, and promote greater understanding and mutual trust by working on common goals such as economic development, environment, health, education, sports, music, and information technology. Since the program's start in 2004, USAID and U.S. Embassy Tel Aviv have invested in 113 CMM grants."15 Per the 2017 factsheet, at the time of its release the program included 33 grants, including the following: Dead Sea and Arava Science Center (2016-2019; $1,000,000): Promotes cooperation on water management and economic development in the Red Sea-Dead Sea basin for sustainable improved livelihoods and the reduction of conflict among 230 Palestinians, Israelis, and Jordanians. Kids4Peace (2016-2019; $800,000): Connects more than 1,000 youth and parents from East and West Jerusalem and neighboring West Bank communities in cross-border programs that foster civic involvement, celebrate the religious diversity of Jerusalem, and encourage key populations to support a pro-peace agenda. Near East Foundation (2016-2019; $1,200,000): Targets 1,000 olive producers, mill operators, and olive oil distributors in 37 communities in Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan to expand economic cooperation, build working relationships between business and policy leaders, and develop 30 women-owned businesses through cross-border collaboration. Middle East Entrepreneurs for Tomorrow (2015-2017, $850,454): Provides training for 70-80 excelling Israeli and Palestinian youth between ages 15-18 in advanced technology, entrepreneurship, and leadership. This project also works on establishing networks of mutual trust, understanding, respect, and teamwork. |

Ending U.S. Contributions to UNRWA16

On August 31, 2018, the State Department announced that the United States will not make further contributions to UNRWA:

The Administration has carefully reviewed the issue and determined that the United States will not make additional contributions to UNRWA. When we made a U.S. contribution of $60 million in January, we made it clear that the United States was no longer willing to shoulder the very disproportionate share of the burden of UNRWA's costs that we had assumed for many years. Several countries, including Jordan, Egypt, Sweden, Qatar, and the UAE have shown leadership in addressing this problem, but the overall international response has not been sufficient.

Beyond the budget gap itself and failure to mobilize adequate and appropriate burden sharing, the fundamental business model and fiscal practices that have marked UNRWA for years – tied to UNRWA's endlessly and exponentially expanding community of entitled beneficiaries – is simply unsustainable and has been in crisis mode for many years. The United States will no longer commit further funding to this irredeemably flawed operation. We are very mindful of and deeply concerned regarding the impact upon innocent Palestinians, especially school children, of the failure of UNRWA and key members of the regional and international donor community to reform and reset the UNRWA way of doing business. These children are part of the future of the Middle East. Palestinians, wherever they live, deserve better than an endlessly crisis-driven service provision model. They deserve to be able to plan for the future.

Accordingly, the United States will intensify dialogue with the United Nations, host governments, and international stakeholders about new models and new approaches, which may include direct bilateral assistance from the United States and other partners, that can provide today's Palestinian children with a more durable and dependable path towards a brighter tomorrow.17

The U.S. decision to end contributions could greatly affect UNRWA, which provides education, health care, and other forms of humanitarian assistance for around 5.4 million Palestinian refugees registered in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. The United States has been a major contributor to UNRWA since its establishment shortly after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and provided approximately one-third of UNRWA's annual budget in 2017.18 For additional background on UNRWA, see Appendix B.

|

Challenges to UNRWA's Work Demands on UNRWA's emergency and refugee assistance markedly increased over the past decade, owing largely to conflict-related humanitarian needs—particularly in Gaza and Syria. Such needs are driven by factors such as general insecurity, problems with humanitarian access and provision of assistance, deteriorating socio-economic conditions, and funding shortfalls, all of which affect UNRWA's beneficiaries in different ways in its five field operations (West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria). Globally, U.S. humanitarian policy and provision of assistance has typically been based on need and intended to remain independent of politics. In response to increased references to UNRWA in the Israeli-Palestinian political debate, some observers have asserted that funding to UNRWA provides essential, lifesaving assistance to vulnerable Palestinian refugees and should not be used as leverage in negotiations.19 |

U.S. contributions to UNRWA—separate from U.S. bilateral aid to the West Bank and Gaza—have come from the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) account (including some amounts designated as MRA-Overseas Contingency Operations assistance, or MRA-OCO) and, in exceptional situations, the Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance (ERMA) account. These are global humanitarian accounts and generally do not include legislative earmarks to specify funding amounts for UNRWA or other organizations. U.S. contributions to UNRWA have been administered by the State Department's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM).

|

Fiscal Year(s) |

Amount |

Fiscal Year(s) |

Amount |

||||

|

1950-1989 |

|

2005 |

|

||||

|

1990 |

|

2006 |

|

||||

|

1991 |

|

2007 |

|

||||

|

1992 |

|

2008 |

|

||||

|

1993 |

|

2009 |

|

||||

|

1994 |

|

2010 |

|

||||

|

1995 |

74.8 |

2011 |

249.4 |

||||

|

1996 |

77.0 |

2012 |

233.3 |

||||

|

1997 |

79.2 |

2013 |

294.0 |

||||

|

1998 |

78.3 |

2014 |

398.7 |

||||

|

1999 |

80.5 |

2015 |

390.5 |

||||

|

2000 |

89.0 |

2016 |

359.5 |

||||

|

2001 |

123.0 |

2017 |

359.3 |

||||

|

2002 |

119.3 |

2018 |

65.0 |

||||

|

2003 |

134.0 |

||||||

|

2004 |

127.4 |

TOTAL |

6,248.4 |

Source: U.S. State Department.

Note: All amounts are approximate.

The U.S. decision in August to stop providing funds for UNRWA has prompted public debate, including among Members of Congress. The debate has focused both on how UNRWA might adjust to or compensate for the cuts, and on how changes or alternatives to UNRWA's operations might affect refugees' lives and associated political and security issues (see "Assessment" and "UNRWA-Related Bills" below).

|

U.S. Debate and U.N. Information on Refugee Status of Descendants Within the United States, public debate from 2012 to 2015 surrounded an effort by some Members of Congress to have the executive branch provide a report related to the refugee status of descendants of original Palestinian refugees (see Appendix B for more information). The issue reemerged in U.S. public debate in 2018 surrounding the Trump Administration's decision to stop funding UNRWA.20 The United Nations has said the following on the issue: Under international law and the principle of family unity, the children of refugees and their descendants are also considered refugees until a durable solution is found. Both UNRWA and UNHCR [U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, the organization responsible for all refugees worldwide outside of UNRWA's mandate] recognize descendants as refugees on this basis, a practice that has been widely accepted by the international community, including both donors and refugee hosting countries. Palestine refugees are not distinct from other protracted refugee situations such as those from Afghanistan or Somalia, where there are multiple generations of refugees, considered by UNHCR as refugees and supported as such. Protracted refugee situations are the result of the failure to find political solutions to their underlying political crises.21 |

In response to the August 31 U.S. decision to withhold contributions, UNRWA Commissioner-General Pierre Krahenbuhl said that the responsibility for the protracted nature of the refugee issue "lies squarely with the parties and in the international community's lack of will or utter inability to bring about a negotiated and peaceful resolution of the conflict," and that attempting to hold UNRWA responsible is "disingenuous at best."22

Until sometime in August, the Israeli government had reportedly been recommending that U.S. officials make any reductions in funding to UNRWA gradual and leave Gaza unaffected.23 This position apparently had the support of Israel's security establishment, based on concerns about the potential humanitarian and security consequences of larger cuts.

Reports citing senior Israeli officials suggest that Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu changed course without consulting his security officials and urged President Trump to cut all funding for UNRWA.24 In voicing support for the U.S. decision, Netanyahu said that UNRWA was formed "not to absorb the refugees but to perpetuate them."25 However, PLO Secretary General Saeb Erekat said that UNRWA is a U.N. agency, not a Palestinian one, "and there is an international obligation to assist and support it until all the problems of the Palestinian refugees are solved."26 The U.N. website states, "The General Assembly continues to determine the necessity of UNRWA's work in the absence of a just resolution of the question of Palestine refugees. In the absence of UNRWA, Palestine refugees would still exist."27

UNRWA intends to carry on its operations and to seek emergency funding to meet its deficit for calendar year 2018, which was estimated to be $21 million in late November.28 Anticipating the U.S. decision, an UNRWA spokesperson said, "The fact that any particular member state decides to withhold funding does not change our mandate. It just means we have less money to implement it."29 UNRWA's current mandate from the U.N. General Assembly runs until June 2020.30 According to UNRWA officials, the agency has saved $92 million internally via austerity and reform measures,31 and other countries have pledged nearly $425 million in an attempt to cover its 2018 shortfall.32 Some Arab states, European countries, and Japan are involved in efforts to help raise funds.33

If UNRWA cannot provide core services such as youth education and health care (about 58% and 15% of UNRWA's budget, respectively),34 it is unclear what alternatives Palestinian refugees might have. In late August, Israeli defense officials reportedly told Israeli leaders that swift cuts affecting UNRWA in Gaza could create a vacuum for social services that could strengthen Hamas.35 A former Israeli military spokesman argued that a similar vacuum could affect stability in the West Bank.36 Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria also host Palestinian refugees under UNRWA's mandate, and the funding cuts could trigger similar stability concerns in those countries.37 One article quoted a number of sources from the humanitarian sector as saying that other organizations would have difficulty replacing UNRWA because of the large scope of its operations and because UNRWA—in contrast to most organizations—implements its programs directly instead of using implementing partners.38 However, in a September analysis, a former general counsel for UNRWA said that the end of U.S. funding "should not have a dire impact on the Palestinians," referring to ways in which UNRWA might make its education and health care benefits more cost-effective and need-based.39

Continuing Security Assistance

The United States has used bilateral aid from the INCLE account to train and provide nonlethal equipment for PA civil security forces in the West Bank loyal to President Abbas.40 This aid, which is the only major stream of U.S. funding to the Palestinians that continues unabated, is aimed at countering militants from organizations such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and at improving rule of law in areas that the PA controls. It also appears to encourage greater PA security coordination with Israel.

To date, PA security forces have continued this coordination with Israel, despite widespread opposition in Palestinian public opinion. Multiple decisions by the PLO Central Council—most recently in October—have called on the PA to terminate security coordination,41 and in the wake of the various U.S. funding cuts in 2018, some Palestinians have called for the PA to reconsider its stance.42 A September poll of Palestinians indicated that 68% favor ending security coordination with Israel, but 69% do not believe that the PA will end it.43

Assessment

Political Strategy and Leverage

Various actors have expressed opinions about the U.S. political strategy behind the funding changes. Palestinian leaders have insisted that the Trump Administration has aligned itself with Israel to predetermine key diplomatic outcomes regarding Jerusalem and refugees.44 Top Administration officials, meanwhile, assert that they are discarding failed diplomatic frameworks of the past and helping the Palestinians come to terms with the realities they will face in a future negotiation. For example, White House senior advisor Jared Kushner has said, "All we're doing is dealing with things as we see them and not being scared out of doing the right thing. I think, as a result, you have a much higher chance of actually achieving a real peace."45 Some observers have noted that this Administration's vision of a negotiated solution may not differ much from those of past Administrations.46 They also debate how this Administration's apparent departure from past Administrations' symbolic toleration of Palestinian demands on key issues might affect the chances for resolution.47

Some Members of Congress are skeptical that economic pressure could lead to Palestinian political concessions. In a September 21 letter to President Trump, 34 Senators expressed opposition to using funding cuts to persuade the PLO and PA to reengage diplomatically with the United States:

We are deeply concerned that your strategy of attempting to force the Palestinian Authority to the negotiating table by withholding humanitarian assistance from women and children is misguided and destined to backfire. Your proposed cuts would undermine those who seek a peaceful resolution and strengthen the hands of Hamas and other extremists in the Gaza Strip, as the humanitarian crisis there worsens.48

On September 28, 112 Representatives sent a similar letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urging the Administration to reverse its decision regarding various U.S. funding streams for the Palestinians.49

The political strategy's success appears largely tied to whether cutting funding streams will increase U.S. leverage over the Palestinians, as the President appeared to anticipate in his September statement cited above.50 A former director of USAID's programs for the West Bank and Gaza has said that "it won't work. Because [the programs are] effectively implemented outside of the PA. There's no leverage that's attached to this."51 Two other former U.S. officials claim that the withdrawal of material benefits and political access for the Palestinians could decrease rather than increase U.S. influence on Palestinian actions—expressing concern that the Administration has "unwittingly unshackled the Palestinians."52 To date, Abbas and other Palestinian officials have not indicated any change in their position, but have rather focused their public efforts on rallying support for the Palestinians within the United Nations and other international fora in opposition to U.S. and Israeli policies.53 In a September poll of Palestinians, 62% opposed resuming dialogue with the Trump Administration.54

The Changes' Direct Impact

Various stakeholders have expressed opinions about the probable impact of U.S. funding changes on different forms of assistance to the Palestinians, and the second-order effects they could have for the region. The September 21 letter to President Trump from 34 Senators urged the President to reverse his funding cuts, claiming, "Specifically, according to the organizations implementing USAID-funded [ESF] programs in the West Bank and Gaza, these cuts will prevent

- nearly 140,000 individuals from receiving emergency food aid;

- 3,000 children and their caregivers from receiving healthcare for anemia and malnutrition;

- up to 71,000 individuals from receiving access to clean water;

- 800 children from receiving rehabilitation services for cerebral palsy; and,

- 16,000 women from receiving clinical breast cancer treatment.

In addition, [the] decision to end U.S. contributions to UNRWA puts at risk

- civilian, secular education for 525,000 kids, 50 percent of which are girls, in more than 700 schools;

- food assistance to 1 million residents in Gaza, half of its population; and,

- public health in the refugee population, where UNRWA has long achieved a 100 percent vaccination rate.55

Gaza

Much of the focus from international organizations has been on the possibility that funding cuts could make a difficult situation in Gaza worse.56 According to the World Bank, large transfers of aid and PA money have kept Gaza's economy afloat, but those transfers have significantly declined since 2017. Furthermore

In this environment the USD30 million per month reduction in PA payments in 2018, the winding down of the USD50-60 million per year [bilateral economic aid] operation of the US Government, and the cuts being made in the UNRWA program are having a significant effect on economic growth and unemployment.57

In summer 2018, 70 Representatives and 10 Senators wrote letters to Administration officials, urging them to provide economic aid and UNRWA contributions to alleviate humanitarian challenges in Gaza.58

On August 24, a State Department official defended the U.S. decision to reprogram ESF away from the West Bank and Gaza by saying that "this decision takes into account the challenges the international community faces in providing assistance in Gaza, where Hamas control endangers the lives of Gaza's citizens and degrades an already dire humanitarian and economic situation."59

For more on Gaza, see CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti; and CRS In Focus IF10644, The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy, by Jim Zanotti.

West Bank

Some observers have expressed concern that funding cuts for the West Bank could undermine the relative stability and economic well-being that its residents have experienced over the past ten years. According to one account drawn from interviews with former Israeli security officials, discontinuing bilateral economic aid and contributions to UNRWA could "undo much of this hard-won stability, potentially putting untold numbers of Palestinian workers, students, and refugees out onto the streets."60

Regarding the reprogramming of $25 million away from the six hospitals forming the East Jerusalem Hospital Network, various parties (including church groups in the United States and Europe) have voiced concern that these hospitals provide specialized treatment to Palestinians that they cannot obtain in the West Bank and Gaza.61 Palestinian children with cancer are reportedly in particular need of services from these hospitals, and other types of treatment not generally available elsewhere include cardiac surgery, neonatal intensive care, and pediatric dialysis.62 After the U.S. funding change was announced, the PA reportedly told East Jerusalem hospitals that it could provide them $20 million.63

2018 Legislation

Taylor Force Act: No ESF That "Directly Benefits" the PA

Congress enacted the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141) in March 2018 to alter restrictions on bilateral ESF (including ESF-OCO) in annual appropriations legislation that date from FY2015 and are used to discourage certain PLO/PA payments "for acts of terrorism." The PLO/PA makes payments to some Palestinians (and/or their families) imprisoned for or accused of terrorism by Israel. Because money is fungible, and the United States has regularly helped to defray PA debts, critics have asserted that any aid directly benefitting the PA could indirectly support such payments.64 In June 2017 testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said, "Attaching payments as recognition of violence or murders is something the American people could never accept or understand."65 A March 2018 media article stated that Palestinians acknowledge some payments go to people who make "heinous attacks" or their families. However, the same article also said, "There is no standard definition for terrorism in the U.S. government, a problem State Department officials encountered when they sought to penalize the PA [under the provisions dating from FY2015]. Indeed, Palestinians may be jailed by Israel as security threats for acts that some—or many—Americans might consider civil disobedience."66

|

Palestinian Payments for "Martyrs" and Prisoners The Palestinian practice of compensating families who lost a member (combatant or civilian) in connection with Israeli-Palestinian violence reportedly dates back to the 1960s.67 Palestinian payments on behalf of prisoners or decedents in their current form apparently "became standardized during the second intifada [uprising] of 2000 to 2005."68 Various PA laws and decrees since 2004 have established parameters for payments.69 U.S. lawmakers and the Trump Administration have condemned the practice to the extent it might incentivize violence, focusing particular criticism on an apparent tiered structure that provides higher levels of compensation for prisoners who receive longer sentences.70 |

The Taylor Force Act suspends all ESF aid that "directly benefits" the PA (with specific exceptions for the East Jerusalem Hospital Network and a certain amount for wastewater projects and vaccination programs) unless and until the Administration certifies that the PA and PLO

- are taking credible steps to end acts of violence against Israeli citizens and U.S. citizens that are perpetrated or materially assisted by individuals under their jurisdictional control, such as the March 2016 attack that killed former U.S. Army officer Taylor Force, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan;

- have terminated payments for acts of terrorism against Israeli citizens and U.S. citizens to any individual, after being fairly tried, who has been imprisoned for such acts of terrorism and to any individual who died committing such acts of terrorism, including to a family member of such individuals;

- have revoked any law, decree, regulation, or document authorizing or implementing a system of compensation for imprisoned individuals that uses the sentence or period of incarceration of an individual imprisoned for an act of terrorism to determine the level of compensation paid, or have taken comparable action that has the effect of invalidating any such law, decree, regulation, or document; and

- are publicly condemning such acts of violence and are taking steps to investigate or are cooperating in investigations of such acts to bring the perpetrators to justice.

If the Administration cannot certify that the PA and PLO have taken these steps, the Administration is required to report to Congress on the reasons for its failure to certify, the definition of "acts of terrorism" that it used, and the amount of aid to be withheld. Separately, the act requires the Administration to submit to Congress an updated list of the criteria it uses to determine which assistance "directly benefits" the PA, given that questions persist about how broadly this term might apply to certain kinds of development and humanitarian assistance. Additionally, for six years the Administration must submit an annual report to Congress providing estimates of PLO/PA terrorism-related payments, along with information related to the Palestinian legal basis for the payments and to U.S. efforts toward the goal of ending the PLO/PA payments and removing any such legal basis.

The Taylor Force Act also contains a mechanism by which the withheld aid can be used to directly benefit the PA if the Administration makes the certification described above within a certain time period. However, after that time period expires, 50% of the withheld aid can be used for purposes that do not directly benefit the PA, and 50% can only be used outside of the West Bank and Gaza.

Since FY2015, annual appropriations legislation (including §7041(m)(3) of P.L. 115-141, as extended by the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019, or P.L. 115-245) has provided for "dollar-for-dollar" reduction of ESF aid for the PA in relation to PLO/PA terrorism-related payments. ESF amounts withheld under the Taylor Force Act need to be at least what is required under the dollar-for-dollar reduction provision, and will be deemed to satisfy that provision.71

While Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu praised the enactment of the Taylor Force Act, the then-PLO representative to the United States,72 Husam Zomlot, denounced it as flagrantly biased and deliberately aimed at the Palestinian people.73 It is unclear whether the act will significantly affect PLO/PA terrorism-related payments. In July, PLO Chairman and PA President Abbas reportedly insisted that the payments would not stop.74

Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018: Possible Complete End to Bilateral Aid

The House and Senate passed the ATCA (P.L. 115-253) in September, and the President signed it in October. The act might increase the possibility that the PA could face terrorism-related lawsuits in the United States by stating that a defendant consents to personal jurisdiction if it accepts any form of U.S. foreign assistance—including bilateral economic or security assistance. The act appears in large part to be a response to a federal court case (known in various incarnations as Waldman v. PLO and Sokolow v. PLO). In the case, a jury awarded hundreds of millions of dollars in damages from the PLO and PA to families of victims of terrorism from the second intifada (between 2002 and 2004),75 but an appeals court dismissed the suit because it ruled that jurisdiction was lacking.76

Absent further congressional action, the ATCA might indirectly lead to a complete end to U.S. bilateral aid for the Palestinians and shutdown of the accompanying in-country activities of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Security Coordinator (USSC) for Israel and the Palestinian Authority. According to one analysis, even though the Palestinian leaders still have legal defenses available to them, they have determined "that the limited U.S. foreign assistance currently received is far outweighed by the potential liability to which they would be subjected if they were to accept it."77 Reportedly, U.S. and Palestinian officials are preparing for a possible end to U.S. aid before the ATCA takes full effect on February 1, 2019.78 The Trump Administration may be pursuing efforts to have Congress change the ATCA to facilitate the continuation of security assistance, at least, with one media report suggesting that the White House belatedly realized the ATCA's possible impact.79

Options for Congress

Congress has the power to appropriate, condition, or prohibit various forms of funding for the Palestinians, including bilateral aid and humanitarian contributions to UNRWA. Congress also could provide U.S. foreign assistance to other countries (such as Jordan or Lebanon) or organizations to benefit the Palestinians receiving UNRWA services.80 Additionally, congressional oversight could focus on potential implications of the Administration's funding decisions and other aspects of U.S. aid to the West Bank and Gaza or contributions to UNRWA.

FY2019 Appropriations Legislation

Pending legislation includes the FY2019 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations bills (H.R. 6385, S. 3108). Both bills would carry forward the conditions attached to bilateral aid for FY2018 (for more information, see Appendix A), and contain a reporting requirement for UNRWA virtually identical to the provision that has been in annual appropriations legislation since FY2015 (see Appendix B).

UNRWA-Related Bills

Bills introduced earlier this year regarding UNRWA include the Palestinian Assistance Reform Act (S. 3425), the UNRWA Accountability Act of 2018 (H.R. 5898, ordered to be reported amended by the House Foreign Affairs Committee on June 28), and the UNRWA Reform and Refugee Support Act of 2018 (H.R. 6451).

Palestinian Partnership Fund Act (S. 3549 and H.R. 7060)

Members in the Senate and House introduced versions of the Palestinian Partnership Fund Act (S. 3549 and H.R. 7060) in October. The bill would establish a fund to finance

- joint economic development, research, and business initiatives (including in the high-tech industry) linking Palestinian companies with those of the United States, Israel and other countries; and

- people-to-people exchanges seemingly similar to those in the CMM program, which, as mentioned above, the Administration changed in September.

Under the bill's provisions as introduced, the State Department (in consultation with USAID and the Commerce and Treasury Departments) would establish the fund, and congressional leaders would appoint its governing officers. Additionally, the fund's administrators would be precluded from discriminating "against any community or entity in Israel, the West Bank, or Gaza"—presumably including Israeli settlements in the West Bank—"due to its geographic location." The bill would authorize annual contributions to be appropriated from FY2019 through FY2024—with S. 3529 authorizing $100 million per year and H.R. 7060 authorizing $50 million per year. The Senate committee version of the FY2019 appropriations bill for State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (S. 3108) would appropriate $50 million in ESF for a Palestinian Partnership Fund for that fiscal year. Amounts used from the fund would be subject to vetting on terms similar to those applicable to foreign aid to the Palestinians, and would not be available for individuals or groups involved in or advocating terrorist activity.

Appendix A. Background on U.S. Aid to the Palestinians

Overview

Significant bilateral U.S. aid to the Palestinians began when the Palestinians achieved limited self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the mid-1990s.81 Bilateral aid to the Palestinians since 1994 has totaled more than $5 billion. It was restructured in 2007, as mentioned above, to account for Hamas controlling Gaza. Since then, much of the U.S. bilateral aid has gone toward security, economic development, self-governance, and humanitarian needs—with an emphasis on strengthening the West Bank-based, Fatah-led PA vis-à-vis Hamas. However, at various points, the executive branch and Congress have taken various measures to reduce, delay, or place conditions on this aid. Annual appropriations legislation routinely contains the following selected conditions:82

- Hamas and terrorism. Aid to Hamas or Hamas-controlled entities is specifically prohibited, and no aid may be made available for the purpose of recognizing or otherwise honoring individuals who commit or have committed acts of terrorism. Additionally, the Secretary of State is required to take all appropriate steps to ensure that economic assistance for the West Bank and Gaza does not support terrorism, and to terminate assistance to "any individual, entity, or educational institution which the Secretary has determined to be involved in or advocating terrorist activity."83

- Fatah-Hamas "unity" government scenario. Generally, no aid is permitted for a power-sharing PA government that includes Hamas as a member, or that results from an agreement with Hamas and over which Hamas exercises "undue influence." This general restriction is only lifted if the President certifies that the PA government, including all ministers, has "publicly accepted and is complying with" the following two principles embodied in Section 620K of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended by the Palestinian Anti-Terrorism Act of 2006 (PATA, P.L. 109-446): (1) recognition of "the Jewish state of Israel's right to exist" and (2) acceptance of previous Israeli-Palestinian agreements (the "Section 620K principles").84 If the PA government is "Hamas-controlled," PATA applies additional conditions, limitations, and restrictions on aid.

- International Criminal Court action. ESF assistance for the PA is prohibited if "the Palestinians initiate an International Criminal Court judicially authorized investigation, or actively support such an investigation, that subjects Israeli nationals to an investigation for alleged crimes against Palestinians."85

- Membership in the United Nations or U.N. agencies. ESF assistance for the PA is prohibited if the Palestinians obtain "the same standing as member states or full membership as a state outside an agreement negotiated between Israel and the Palestinians" in the United Nations or any U.N. specialized agency other than U.N. Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).86

- PA personnel in Gaza. No aid is permitted for PA personnel located in Gaza.87

- PLO and Palestinian Broadcasting Corporation (PBC). No aid is permitted for the PLO or for the PBC.88

- Palestinian state. No funds may be provided to support a future Palestinian state unless the Secretary of State certifies that the governing entity of the state has committed to peaceful coexistence with Israel, is taking measures to counter terrorism, and is working to establish "comprehensive peace in the Middle East."89 This restriction can be waived for national security purposes, and does not apply to aid meant to reform the Palestinian governing entity so that it might meet these conditions.

- Vetting, monitoring, and evaluation. For U.S. aid programs for the Palestinians, annual appropriations legislation routinely requires executive branch reports and certifications, as well as internal and Government Accountability Office (GAO) audits. These requirements appear to be aimed at, among other things, preventing U.S. aid from benefitting terrorists or abetting corruption, and assessing aid programs' effectiveness.90 This vetting process has become more rigorous since 2006 in response to recommendations from GAO.91 In April 2016, a GAO report found that USAID had generally complied with vetting requirements since the 2006 changes.92

The effectiveness of U.S. aid to the Palestinians has been challenged by the shifting and often conflicting objectives of Israel and various Palestinian groups. For example, Israeli security requirements or Palestinian factional disputes affect the viability of aid programs to help with Palestinian security, infrastructure, or economic development. Additional complications come from coordinating U.S. actions with the activities of other donor states and international organizations such as the European Union (EU), United Nations,93 World Bank, the Office of the Quartet Representative,94 and the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee.95

As mentioned above, bilateral economic aid to the Palestinians is appropriated through the ESF account. Project assistance has been provided by USAID and other government agencies to implementing partners (both for-profit and nonprofit grantees) operating in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.96 Funds have been used for humanitarian assistance, economic development, democratic reform, improving water access and other infrastructure, health care, and education.97 In addition to project assistance, since FY2014 the United States has provided some budgetary assistance for the PA through direct payments to its creditors—mainly Israeli utility companies and East Jerusalem hospitals.98 The PA, with a regular annual budget deficit of over $1 billion, is dependent on external sources to meet its financial commitments.99

|

Past Aid Limitations or Holds Since 2011, when the Palestinians unsuccessfully sought to gain membership in the United Nations, the Palestinians have faced reprisals from the United States and Israel for international initiatives or other actions that go against U.S. or Israeli positions. Past reprisals included informal congressional holds that delayed disbursement of U.S. aid (mostly ESF),100 and temporary Israeli refusals to transfer tax and customs revenues due the PA.101 Since FY2015, legislative provisions regarding Palestinian payments "for acts of terrorism) (see "Taylor Force Act: No ESF That "Directly Benefits" the PA") have reduced U.S. economic aid for the PA. |

In addition to providing bilateral assistance to the Palestinians, the United States has allocated some amounts from various foreign assistance accounts for Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation or Arab-Israeli cooperation.102

Security Assistance

Since Hamas forcibly took control of the Gaza Strip in June 2007, the office of the U.S. Security Coordinator (USSC) for Israel and the Palestinian Authority has worked in coordination with the State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) to sponsor bilateral, nonlethal security assistance programs for West Bank-based PA security forces from the INCLE account. The PA newly recruited and vetted many of these personnel in the period roughly spanning 2008-2012. Much of the U.S.-sponsored training has taken place in Jordan, at least partly because of Israeli conditions on the use of firearms in the West Bank. The USSC is a three-star U.S. general/flag officer, supported as of early 2018 by U.S. and allied staff and military officers from the United Kingdom, Canada, Turkey, Italy, and the Netherlands.103 Around 2012, the USSC/INL program reportedly shifted to a less resource intensive "advise and assist" role alongside its efforts to assist the PA in improving the functioning of its criminal justice system.

The USSC/INL security assistance program exists alongside other assistance and training programs provided to Palestinian security forces and intelligence organizations by various countries and the European Union (EU).104 By most accounts, the PA forces receiving training have shown increased professionalism and have helped improve law and order in West Bank cities, despite continuing challenges that stem from squaring Palestinian national aspirations with coordinating security with Israel.105

Appendix B. Background on UNRWA and U.S. Contributions106

Since UNRWA's inception in 1949, the United States has been the agency's largest donor, with more than $6 billion in contributions. UNRWA's mandate is to "provide relief, human development and protection services to Palestine refugees and persons displaced by the 1967 hostilities in its fields of operation: Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, West Bank and the Gaza Strip."107 The U.N. General Assembly continues to renew UNRWA's mandate pending resolution of the status of "Palestine refugees"—approximately 5.4 million people who include original refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and their descendants in the places listed above.108 All other refugees worldwide fall under the mandate of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

UNRWA is partly shaped by the context in which it operates. Most of UNRWA's employees—other than its senior international staff—are drawn from the Palestinian refugee population it serves. UNRWA's website states that its role encompasses "global advocacy for Palestine refugees" in addition to the provision of assistance and protection.109 UNRWA does not have a robust policing capability. It often faces security concerns along with political pressures from Hamas and other actors.

The program budget for UNRWA's core programs is funded mainly by Western governments, international organizations, and private donors via voluntary contributions.110 Core programs include providing food, shelter, education, medical care, microfinance, and other humanitarian and social services to designated beneficiaries. UNRWA also launches emergency appeals and special funds for pressing humanitarian needs. In FY2017, the United States contributed a total of $359.3 million: $160 million to the program budget, $103.3 million to an emergency appeal for Syria, $95 million to a West Bank/Gaza emergency appeal, and around $966,000 to an anti-gender-based violence initiative called "Safe from the Start."111

Vetting of UNRWA Contributions

Some Members of Congress have raised concerns that U.S. contributions to UNRWA might be used to support terrorists. Section 301(c) of the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act (P.L. 87-195), as amended, says that "No contributions by the United States shall be made to [UNRWA] except on the condition that [UNRWA] take[s] all possible measures to assure that no part of the United States contribution shall be used to furnish assistance to any refugee who is receiving military training as a member of the so-called Palestine Liberation Army or any other guerrilla type organization or who has engaged in any act of terrorism."

To date, no arm of the U.S. government has found UNRWA to be out of compliance with Section 301(c). For 2010 and each year thereafter, the State Department and UNRWA have had a nonbinding "Framework for Cooperation" in place, the most recent of which was signed in November 2017. Each of the documents has agreed that, along with the compliance reports UNRWA submits to State biannually, State would use enumerated criteria as a way to evaluate UNRWA's compliance with Section 301(c).112

Some Members of Congress have supported legislation or resolutions aimed at increasing oversight of UNRWA, strengthening its vetting procedures, and/or capping U.S. contributions. Since FY2015, annual appropriations legislation (for FY2019, Section 7048(d) of P.L. 115-141, as extended by the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2019, or P.L. 115-245) has included a provision requiring the State Department to report to Congress on whether UNRWA is

- using Operations Support Officers to inspect UNRWA installations and reporting any inappropriate use;

- acting promptly to address any staff or beneficiary violations of Section 301(c) or UNRWA internal policies;

- implementing procedures to maintain its facilities' neutrality, and conducting regular inspections;113

- taking necessary and appropriate measures to ensure Section 301(c) compliance and related reporting;

- taking steps to ensure the content of educational materials taught in UNRWA-administered schools and summer camps is consistent with the values of human rights, dignity, and tolerance and does not induce incitement;114

- not engaging in financial violations of U.S. law, and taking steps to improve financial transparency; and

- in compliance with U.N. audit requirements.

In 2012, public debate intensified in the United States over whether UNRWA was perpetuating the refugee issue by providing services to descendants of the original Palestinian refugees from 1948.115 That year, the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs approved a reporting requirement in connection with FY2013 appropriations (S.Rept. 112-172) that, if enacted, would have required the Secretary of State to differentiate between the original 1948 refugees and their descendants. In a letter to the subcommittee, the State Department objected, asserting that this requirement would be "viewed around the world as the United States acting to prejudge and determine the outcome of this sensitive issue."116 Another subcommittee report (S.Rept. 113-81), associated with the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (P.L. 113-76), required the State Department to fulfill the reporting requirement from S.Rept. 112-172. The State Department produced a classified version of the report in 2015, and a declassified, partially redacted version became publicly accessible in July 2018.

Regarding this issue, UNRWA officials insisted that established "principles and practice—as well as realities on the ground—clearly refuted the argument that the right of return of Palestine refugees would disappear or be abandoned if UNHCR [instead of UNRWA] were responsible for these refugees."117 As part of the public debate, some observers asserted that the UNHCR definition for refugees was different from the UNRWA definition.118 The 2015 State Department report contained the following passage:

Considering descendants of refugees as refugees, and providing them with aid and services, is not unique to Palestinian refugees. In protracted refugee situations, refugee groups experience natural population growth over time. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and UNRWA both recognize descendants of refugees as refugees for purposes of their operations. For example, UNHCR recognizes descendants of refugees as refugees in populations including, but not limited to, the Tibetan refugee population of India and Nepal, the Burmese refugee population in Thailand, the Bhutanese refugee population in Nepal, the Afghan population in Pakistan, and the Somali population in Kenya.119

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Hamas has been designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), a Specially Designated Terrorist (SDT), and a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) by the U.S. government. |

| 2. |

Daniel Estrin, "U.S. Palestinian Aid Cuts Hit Programs Providing Food and Health for Gaza's Poorest," NPR, August 1, 2018; Krishnadev Calamur, "A U.S. Funding Review Is Hurting Aid Groups and Palestinians," theatlantic.com, August 10, 2018. |

| 3. |

Michael Wilner, "Pompeo: U.S. Blocked $165M in Funding due to Palestinian Incitement," jpost.com, October 11, 2018; USAID email correspondence with CRS, October 12, 2018. |

| 4. |

White House, Remarks by President Trump in Rosh Hashanah National Press Call with Jewish Faith Leaders and Rabbis, September 6, 2018. |

| 5. |

Edward Wong, "U.S. Is Eliminating the Final Source of Aid for Palestinian Civilians," New York Times, September 14, 2018. |

| 6. |

USAID FY2018 Congressional Notifications #201 (South Africa), #202 (Zimbabwe), #204 and #205 (Barbados and Eastern Caribbean), #206 (Nicaragua), #207 (Peru), #208 (USAID South America Regional), #210 (Ghana), #215 (Paraguay), #216 (Lebanon), #218 (Afghanistan), #219 (Bangladesh), #220 (Indo-Pacific Strategy), #221 (Ethiopia), #223 (Cuba), #227 (Yemen), and #228 (Pilot Program for Direct Vetting), September 10-13, 2018. |

| 7. |

David Brunnstrom, "Trump cuts more than $200 million in U.S. aid to Palestinians," Reuters, August 24, 2018. |

| 8. |

"Trump cuts $25 million in aid for Palestinians in East Jerusalem hospitals," Reuters, September 8, 2018. |

| 9. |

Edward Wong, "U.S. Is Eliminating the Final Source of Aid for Palestinian Civilians," New York Times, September 15, 2018; Daniel Estrin, "U.S. Will No Longer Fund Peace-Building Programs for Palestinians," NPR, September 15, 2018. |

| 10. |

Wong, op. cit. |

| 11. |

Ibid. |

| 12. |

Ibid. |

| 13. |

§7062(f) of Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2012 (P.L. 112-74). |

| 14. |

Wong, op. cit. |

| 15. |

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1883/WBG_2017_CMM_Factsheet_Final.pdf. |

| 16. |

Rhoda Margesson, Specialist in International Humanitarian Policy, contributed to this section. |

| 17. |

State Department, Heather Nauert, Department Spokesperson, "On U.S. Assistance to UNRWA," Washington, DC, August 31, 2018. |

| 18. |

See 2017 donor contributions at https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/overalldonor_ranking.pdf. The United States contributed approximately $364 million of the $1.121 billion spent by UNRWA (including its regular program budget and other emergency appeals and projects) in calendar year 2017. |

| 19. |

In a January 2018 letter to then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis, 21 global humanitarian aid organizations expressed concern that the Administration's January decision to withhold some funding from UNRWA was political rather than need-based. According to these organizations, such a decision was a "dangerous and striking departure from U.S. policy on international humanitarian assistance." Rick Gladstone, "Aid Agencies Ask U.S. to Restore Palestinian Aid," New York Times, January 25, 2018. |

| 20. |

For various perspectives, see, e.g., UNRWA spokesperson Chris Gunness, quoted in Adam Rasgon, "Shift to UNHCR criteria would strip refugee status from millions of Palestinians," Times of Israel, September 6, 2018; James G. Lindsay, "UNRWA: Still UN-Fixed," Justice (The Magazine of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists), Winter 2014-2015, No. 55, pp. 15-23; Jay Sekulow, UNRWA Has Changed the Definition of Refugee, foreignpolicy.com, August 17, 2018; Colum Lynch, "For Trump and Co., Few Palestinians Count as Refugees," foreignpolicy.com, August 9, 2018; Benjamin N. Schiff, "Defunding aid for Palestinian refugees is not a road to peace," thehill.com, September 12, 2018. |

| 21. |

http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/refugees/index.html. |

| 22. |

UNRWA, Open letter from UNRWA Commissioner-General to Palestine refugees and UNRWA staff, September 1, 2018. |

| 23. |

"Scoop: Netanyahu asked U.S. to cut aid for Palestinian refugees," Axios, September 2, 2018. |

| 24. |

"Report: PM lobbied US to defund UNRWA without consulting cabinet, security heads," Times of Israel, September 2, 2018. |

| 25. |

"Israel prime minister praises U.S. decision to cut Palestinian aid," Associated Press, September 2, 2018. |

| 26. |

Karen DeYoung et al., "U.S. ends aid to United Nations agency supporting Palestinian refugees," Washington Post, August 31, 2018. |

| 27. |

http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/refugees/index.html. |

| 28. |

UNRWA, UNRWA Commissioner-General thanks partners for remarkable response in face of unprecedented financial challenges and announces a reduced US$21 million shortfall at Advisory Commission meeting, September 28, 2018. |

| 29. |

Karen DeYoung and Ruth Eglash, "Trump administration to end U.S. funding to U.N. program for Palestinian refugees," Washington Post, August 30, 2018. According to the U.N. website, "UNRWA has not changed and cannot change its mandate. That is the responsibility of UN Member States. These Member States, through the UN General Assembly, have tasked UNRWA to provide assistance and protection to Palestine refugees until a just and lasting political solution is found that addresses their plight." http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/refugees/index.html. |

| 30. |

U.N. General Assembly Resolution A/RES/71/91 (December 22, 2016) renewed UNRWA's mandate through June 2020. |

| 31. |

Email correspondence from UNRWA official to CRS, November 30, 2018. |

| 32. |

UNRWA, UNRWA Commissioner-General thanks partners for remarkable response in face of unprecedented financial challenges and announces a reduced US$21 million shortfall at Advisory Commission meeting, September 28, 2018. |

| 33. |

Ibid. |

| 34. | |

| 35. |

Neri Zilber, "Trump Wants to Help Israel by Cutting Aid to Palestinians. Why are Some Israelis Worried?" foreignpolicy.com, August 29, 2018. |

| 36. |

Peter Lerner, "Trump's Hardball Policy on the Palestinians Will Blow Up in Israel's Face," haaretz.com, August 26, 2018. |

| 37. |

See, e.g., "Defunding UNRWA: Ramifications for Countries Hosting Palestinian Refugees," Arab Center Washington DC, September 4, 2018; Elisabeth Marteu and Sara Fouad Almohamadi, "What does Trump's UNRWA aid cut mean for Palestinians and the Middle East?" International Institute for Strategic Studies, September 21, 2018. |

| 38. |

Amy Lieberman, "Why NGOs cannot fill the gap funding cuts to UNRWA will create," Devex, September 17, 2018. |

| 39. |

James G. Lindsay, "UNRWA Funding Cutoff: What Next?" Washington Institute for Near East Policy, PolicyWatch 3012, September 6, 2018. |

| 40. |

Israel maintains responsibility for security in East Jerusalem, having annexed the area after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. |

| 41. |

Elior Levy, "PLO Central Council calls to halt security coordination with Israel," Ynetnews, October 30, 2018. |

| 42. |

See, e.g., Alaa Tartir, "Aid has been used as a tool to cripple the Palestinians—it's time we took back control," Middle East Eye, September 3, 2018. |

| 43. |

Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), Public Opinion Poll No. 69 Press-Release, September 12, 2018 (poll conducted September 5-8, 2018) |

| 44. |

See, e.g., "US set to announce it rejects Palestinian 'right of return'—TV report," Times of Israel, August 25, 2018. |

| 45. |

Mark Landler, "Kushner Says Punishing Palestinians Shortens Odds for Peace," New York Times, September 14, 2018. |

| 46. |

See, e.g., Robert Malley and Aaron David Miller, "Trump Is Reinventing the U.S. Approach to the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict," theatlantic.com, September 20, 2018; Dalia Hatuqa, "For Palestinians, America Was Never an Honest Broker," foreignpolicy.com, September 13, 2018. |

| 47. |

Ibid. |

| 48. |

Text of letter available at https://plus.cq.com/pdf/5392410.pdf?0. |

| 49. |

Text of letter available at https://price.house.gov/sites/price.house.gov/files/documents/Letter%20to%20State%20Department%20re%20WBG%20%26%20UNRWA%20funding%20cuts.pdf. |

| 50. |

White House, Remarks by President Trump in Rosh Hashanah National Press Call with Jewish Faith Leaders and Rabbis, September 6, 2018. |

| 51. |

Dave Harden, quoted in Calamur, op. cit. |

| 52. |

Malley and Miller, op. cit. |

| 53. |

Mahmoud Abbas, Transcript of remarks before the U.N. General Assembly, September 27, 2018, available at https://www.timesofisrael.com/jerusalem-is-not-for-sale-full-text-of-abbass-speech-to-un-general-assembly/; Ahmad Abu Amer, "Palestinians ponder reasons for punishing US measures," Al-Monitor Palestine Pulse, September 24, 2018. |

| 54. |

PCPSR, Public Opinion Poll No. 69 Press-Release, op. cit. |

| 55. |

Text of letter available at https://plus.cq.com/pdf/5392410.pdf?0. |

| 56. |

For information on the situation, see U.N. Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Gaza Strip: Early Warning Indicators—June 2018, at https://www.un.org/unispal/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/OCHAINFOGRAEWI_120718.pdf. |

| 57. |

World Bank, Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, September 27, 2018. |

| 58. |

Text of July 30, 2018, House letter available at https://pocan.house.gov/sites/pocan.house.gov/files/Gaza-Humanitarian-Aid-Letter-7-30-18.pdf; Text of August 3, 2018, Senate letter available at https://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/a/9/a99dbadf-e6a5-42e2-9d7a-71ee342102e9/773063A06B1141CC50F42A51E1AAEC87.2018.08.03-gaza-aid-letter.pdf. |

| 59. |

Amir Tibon, "Trump Administration to Cut $200 Million from Palestinian Aid," haaretz.com, August 25, 2018. |

| 60. |

Neri Zilber, "Trump Wants to Help Israel by Cutting Aid to Palestinians. Why are Some Israelis Worried?" foreignpolicy.com, August 29, 2018. |

| 61. |

Daoud Kuttab, "Church groups outraged as US denies critical support to Jerusalem hospitals," Al-Monitor Palestine Pulse, September 12, 2018. |

| 62. |

Ibid.; "US cuts $25m aid for Jerusalem hospitals serving Palestinians," Al Jazeera, September 8, 2018. |

| 63. |

Kuttab, op. cit. |

| 64. |

See, e.g., Elliott Abrams, "Stop Supporting Palestinian Terror," National Review, April 17, 2017. |

| 65. |

Testimony of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, June 14, 2017. |

| 66. |

Glenn Kessler, "Does the Palestinian Authority pay $350 million a year to 'terrorists and their families'?" Washington Post, March 14, 2018. |

| 67. |

Neri Zilber, "An Israel 'Conspiracy Theory' That Proved True—but Also More Complicated," theatlantic.com, April 27, 2018. |

| 68. |

Eli Lake, "The Palestinian incentive program for killing Jews," Bloomberg, July 11, 2016. |

| 69. |

Yossi Kuperwasser, "Incentivizing Terrorism: Palestinian Authority Allocations to Terrorists and their Families," Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, at http://jcpa.org/paying-salaries-terrorists-contradicts-palestinian-vows-peaceful-intentions/; Testimony of Yigal Carmon of the Middle East Media Research Institute, transcript from hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa, July 6, 2016. |

| 70. |

See, e.g., Corker Opening Statement at Hearing on Taylor Force Act, July 12, 2017, https://www.corker.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/news-list?ID=CFA1D96C-2FF8-4A70-9C29-49451ADD90AE; Joel Gehrke, "House passes bill that could cut off Palestinian Authority funding due to aid of terrorists' families," Washington Examiner, December 5, 2017. |

| 71. |

One media report suggested that the annual amount required to be withheld under the dollar-for-dollar provision (Section 7041(m)(3)) is classified by the State Department "in part because of how the data used to estimate the figure was collected and in part because U.S. officials have little confidence in the estimates." The report's author speculated that the amount is "significantly smaller" than a public Israeli claim of $350 million, and "perhaps more than two-thirds smaller." Kessler, op. cit. |

| 72. |

Noa Landau, "Netanyahu Lauds U.S. Law Banning 'Salaries' for Palestinian Terrorists, but Israel Delays Similar Legislation," Ha'aretz, March 25, 2018. |

| 73. |

Michael Wilner, "Palestinians Slam Congress's Passage of Taylor Force Act," jpost.com, March 24, 2018. |

| 74. |

"Defiant Abbas says he won't halt stipends to terrorists," Times of Israel, July 9, 2018. |

| 75. |

Scott R. Anderson, "Congress Has (Less Than) 60 Days to Save Israeli-Palestinian Security Cooperation," Lawfare Blog, December 7, 2018. |

| 76. |

Greg Stohr, "U.S. Supreme Court Won't Make PLO Pay $656 Million Terror Award," Bloomberg, April 2, 2018. |

| 77. |

Anderson, op. cit. |

| 78. |

Ibid. See also Robbie Gramer and Colum Lynch, "U.S. Mulls End to Remaining Aid Programs for Palestinians," foreignpolicy.com, November 30, 2018. |

| 79. |

Matthew Lee, "In a twist, Trump fights to keep some Palestinian aid alive," Associated Press, November 30, 2018. |

| 80. |

According to one article, "[White House senior advisor Jared] Kushner had proposed redirecting UNRWA funds to the Jordanian government to help defray the cost of caring for its Palestinians if Amman would agree to fully naturalize them and accept the fact that they would not be granted a right of return to Israel. Jordan rebuffed the proposal." Colum Lynch, "U.S. to End All Funding to U.N. Agency That Aids Palestinian Refugees," foreignpolicy.com, August 28, 2018. |

| 81. |

Prior to the establishment of limited Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza, approximately $170 million in U.S. developmental and humanitarian assistance (not including contributions to UNRWA) were obligated for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza from 1975-1993, mainly through nongovernmental organizations. CRS Report 93-689 F, West Bank/Gaza Strip: U.S. Foreign Assistance, by Clyde R. Mark, July 27, 1993, available to congressional clients on request to Jim Zanotti. |

| 82. |

Current conditions and restrictions for FY2019 are contained in P.L. 115-141, §§7036-7040 and 7041(m), as extended by P.L. 115-245. |

| 83. |

P.L. 115-141, §7039. |

| 84. |

P.L. 115-141, §7040(f). |

| 85. |

P.L. 115-141, §7041(m). For more information, see CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti. |

| 86. |