International Food Assistance: Food for Peace Nonemergency Programs

The U.S. government provides international food assistance to promote global food security, alleviate hunger, and address food crises among the world’s most vulnerable populations. Congress authorizes this assistance through regular agriculture and international affairs legislation, and provides funding through annual appropriations legislation. The primary channel for this assistance is the Food for Peace program (FFP), administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Established in 1954, FFP has historically focused primarily on meeting the emergency food needs of the world’s most vulnerable populations; however, it also manages a number of nonemergency programs. These lesser-known programs employ food to foster development aims, such as addressing the root causes of hunger and making communities more resilient to shocks, both natural and human-induced.

Nonemergency activities, which in FY2019 are funded at a minimum annual level of $365 million, may include in-kind food distributions, educational nutrition programs, training on agricultural markets and farming best practices, and broader community development initiatives, among others. In building resilience in vulnerable communities, the United States, through FFP, seeks to reduce the need for future emergency assistance. Similar to emergency food assistance, nonemergency programs use U.S. in-kind food aid—commodities purchased in the United States and shipped overseas. In recent years, it has also turned to market-based approaches, such as procuring food in the country or region in which it will ultimately be delivered (also referred to as local and regional procurement, or LRP) or distributing vouchers and cash for local food purchase.

The 115th Congress enacted both the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334) and Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266), which authorized all Food for Peace programs through FY2023. In the 116th Congress, Members may be interested in several policy and structural issues related to nonemergency food assistance as they consider foreign assistance, agriculture, and foreign affairs policies and programs in the course of finalizing annual appropriations legislation. For example,

The Trump Administration has repeatedly proposed eliminating funding for the entire FFP program, including both emergency and nonemergency programs, from Agriculture appropriations and instead fund food assistance entirely through Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations. The Administration asserts that the proposal is part of an effort to “streamline foreign assistance, prioritize funding, and use funding as effectively and efficiently as possible.” To date, Congress has not accepted the Administration’s proposal and continued to fund the FFP program in Agriculture appropriations, which is currently authorized through FY2023.

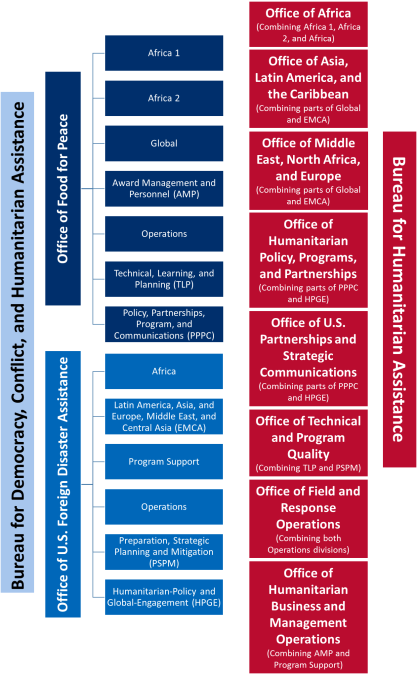

USAID’s internal reform initiative, referred to as Transformation, calls for the merger of the Office of FFP with the Office U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) into a new entity called the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (HA) by the end of 2020. While the agency has indicated that the new HA will administer nonemergency programming, there are few details on how it will do so.

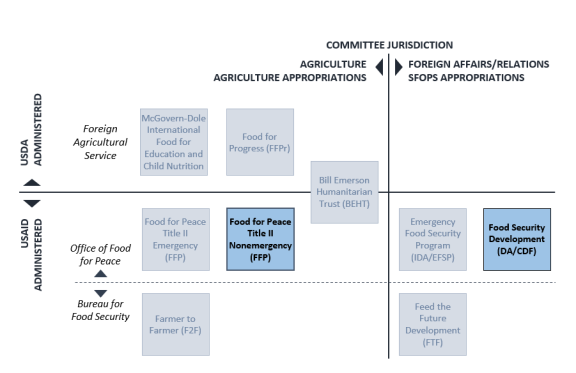

FFP programs fall into two distinct committee jurisdictions—Agriculture and Foreign Affairs/Relations—making congressional oversight of programs more challenging. No one committee receives a comprehensive view of all FFP programming, and the committees of jurisdiction sometimes have competing priorities.

For additional information, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview.

International Food Assistance: Food for Peace Nonemergency Programs

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Food for Peace Nonemergency Programming

- Food for Peace Nonemergency Programs in the Context of U.S. International Food Assistance

- Program Coordination Within USAID

- Legislation

- Funding

- Issues for Congress

- Proposed Elimination of Title II Funding and Food Aid Reform

- Nonemergency Programs in the Context of USAID's Transformation Initiative

- Separation of Food for Peace Nonemergency and Feed the Future Development Programs

- Use of Community Development Funds (CDF)

- Congressional Oversight

- Looking Ahead

Figures

Summary

The U.S. government provides international food assistance to promote global food security, alleviate hunger, and address food crises among the world's most vulnerable populations. Congress authorizes this assistance through regular agriculture and international affairs legislation, and provides funding through annual appropriations legislation. The primary channel for this assistance is the Food for Peace program (FFP), administered by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Established in 1954, FFP has historically focused primarily on meeting the emergency food needs of the world's most vulnerable populations; however, it also manages a number of nonemergency programs. These lesser-known programs employ food to foster development aims, such as addressing the root causes of hunger and making communities more resilient to shocks, both natural and human-induced.

Nonemergency activities, which in FY2019 are funded at a minimum annual level of $365 million, may include in-kind food distributions, educational nutrition programs, training on agricultural markets and farming best practices, and broader community development initiatives, among others. In building resilience in vulnerable communities, the United States, through FFP, seeks to reduce the need for future emergency assistance. Similar to emergency food assistance, nonemergency programs use U.S. in-kind food aid—commodities purchased in the United States and shipped overseas. In recent years, it has also turned to market-based approaches, such as procuring food in the country or region in which it will ultimately be delivered (also referred to as local and regional procurement, or LRP) or distributing vouchers and cash for local food purchase.

The 115th Congress enacted both the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334) and Global Food Security Reauthorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-266), which authorized all Food for Peace programs through FY2023. In the 116th Congress, Members may be interested in several policy and structural issues related to nonemergency food assistance as they consider foreign assistance, agriculture, and foreign affairs policies and programs in the course of finalizing annual appropriations legislation. For example,

- The Trump Administration has repeatedly proposed eliminating funding for the entire FFP program, including both emergency and nonemergency programs, from Agriculture appropriations and instead fund food assistance entirely through Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations. The Administration asserts that the proposal is part of an effort to "streamline foreign assistance, prioritize funding, and use funding as effectively and efficiently as possible." To date, Congress has not accepted the Administration's proposal and continued to fund the FFP program in Agriculture appropriations, which is currently authorized through FY2023.

- USAID's internal reform initiative, referred to as Transformation, calls for the merger of the Office of FFP with the Office U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) into a new entity called the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (HA) by the end of 2020. While the agency has indicated that the new HA will administer nonemergency programming, there are few details on how it will do so.

- FFP programs fall into two distinct committee jurisdictions—Agriculture and Foreign Affairs/Relations—making congressional oversight of programs more challenging. No one committee receives a comprehensive view of all FFP programming, and the committees of jurisdiction sometimes have competing priorities.

For additional information, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview.

Introduction

For more than 65 years, the U.S. Congress has funded international food assistance through the Food for Peace program (FFP) to alleviate hunger and improve global food security. U.S. food assistance comes in the form of in-kind food commodities purchased in the United States and shipped overseas, and through market-based approaches. Market-based approaches include purchasing food in foreign local and regional markets and then redistributing it, and providing food vouchers and cash transfers that recipients can use to buy food locally.

|

What Is Global Food Security? In the 1990 farm bill (P.L. 101-624), Congress defined international food security as "access by any person at any time to food and nutrition that is sufficient for a healthy and productive life." In 1992, USAID issued a policy determination defining food security as "When all people at all times have both physical and economic access to sufficient food to meet their dietary needs for a productive and healthy life."1 This definition took elements from the 1990 definition, as well as food security definitions put forward by the World Bank and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). |

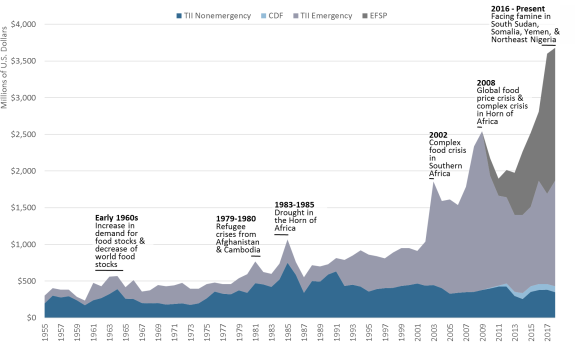

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the lead development and humanitarian arm of the U.S. government, administers the majority of U.S. international food assistance. Within the agency, the Office of Food for Peace manages the FFP program, which provides both emergency and nonemergency food aid. Nonemergency programming once represented a significant portion of FFP, but this portion has declined (from 83% in FY1959 to 11% in FY2018) as emergency needs have continued to rise and FFP has received emergency funding from additional accounts (see Figure 3).2 The Bureau for Food Security (BFS), within USAID, manages agricultural development and nutrition programs, which support food security goals but are not considered food aid under the umbrella of the Feed the Future Initiative (FTF).3 The distinctions between FFP nonemergency programs and BFS development programs are found in authorizing legislation, funding flows, and congressional jurisdiction.4

This report focuses primarily on FFP's nonemergency activities.5 It explains current programs, legislative history, and funding trends. The report also discusses how FFP nonemergency programs fit within the broader food aid and food security assistance framework, and the future of FFP nonemergency programs in the context of related Trump Administration proposals. Finally, this report explores the challenges Congress faces in conducting oversight of U.S. international food assistance programs, which fall under two separate congressional committee jurisdictions.

Food for Peace Nonemergency Programming

In FY2018, Food for Peace (both emergency and nonemergency programs) operated in 59 countries and reached more than 76 million recipients. However, FFP had active nonemergency programs in only 15 countries—most of which were in sub-Saharan Africa, with the remaining in Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia.6

FFP nonemergency programs seek to aid the poorest of the poor by addressing the root causes of hunger and making vulnerable communities more resilient to shocks, both natural and human-induced. Programs generally last five years and, according to FFP, "aim to reduce chronic malnutrition among children under five and pregnant or lactating women, increase and diversify household income, provide opportunities for microfinance and savings, and support agricultural programs that build resilience and reduce vulnerability to shocks and stresses."7 Common types of FFP nonemergency activities include in-kind food, cash or voucher distributions, educational programs to encourage dietary diversity and promote consumption of vitamin- and protein-rich foods, farmer training on agricultural value chains and climate-sensitive agriculture, and conflict sensitivity training for local leaders.8

- In building resilience in vulnerable communities, FFP seeks to reduce the need for future emergency assistance and pave the way for communities to pursue longer-term development goals. With few exceptions, nonemergency programs are implemented by nongovernmental organization (NGO) partners.9 Examples of the range of FFP nonemergency programs include the following:

- Strengthening Household Ability to Respond to Development Opportunities (SHOUHARDO III) in Bangladesh began in 2015 to improve "gender equitable food and nutrition security and resilience of the vulnerable people" in two of the country's regions. USAID identified four areas of concern on which interventions should focus: gender inequality and women's disempowerment, social accountability, youth, and climate adaptation.10 CARE, a nonprofit organization that formed in post-World War II to distribute food packages in Europe, implements SHOUARDO III. The program's goal is to reach 384,000 participants through activities that address climate change and disaster resilience training, supplementary food distributions for pregnant and lactating women, youth skills training, the organization of microenterprise groups, and water supply and sanitation activities, among others.11 SHOUHARDO III is one of the few FFP nonemergency programs that includes a monetization component.12 In FY2018, SHOUHARDO received more than $18 million in FFP Title II funding.13 The program is scheduled to run through the end of FY2020.

- Tuendelee Pamoja II in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was initiated in 2016 to improve food security and resilience among 214,000 households in selected provinces, with a special focus on women and youth. Food for the Hungry, an international Christian relief, development, and advocacy organization, implements the program. Interventions include the distribution and testing of new varieties of soybeans, beans, and maize; construction of planting terraces to reduce land erosion; training on fishing practices; literacy and numeracy education; and youth training in wood- and metal-working; among others.14 The program received more than $15 million in FFP Title II funding in FY2018 and is scheduled to run through the end of 2021.15

- Njira Pathways to Sustainable Food Security in Malawi began in 2014 with the aim of improving food security for more than 244,000 vulnerable people in selected districts in Malawi. The programs were designed to address Feed the Future (FTF)-established food security goals for the country and to complement other FTF programs and development goals under USAID/Malawi Mission's Country Development Cooperation Strategy.16 Project Concern International (PCI), a global development program established in 1961, implements the Njira project; its activities include distributing livestock and offering animal health services to improve livestock production, increasing access to and participation in women's empowerment savings and loan groups, conducting farmer training to combat Fall Armyworm, and distributing food rations to children under five.17 In FY2018, the Njira project received nearly $2 million in FFP Title II nonemergency funds and nearly $2.5 million in Community Development Funds (CDF). The project is slated to run through late 2019. 18

Food for Peace Nonemergency Programs in the Context of U.S. International Food Assistance

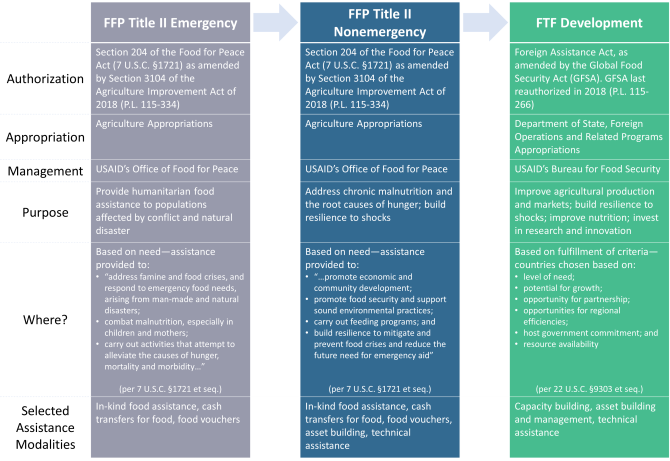

FFP nonemergency programs are largely used to support the transition in food security assistance between short-term emergency food assistance programs and longer-term agricultural development and nutrition assistance programs. They share a close relationship with FFP emergency programs and the BFS-led Feed the Future development programs, but distinct differences exist among these aid channels, which are designed to be complementary and undertaken sequentially (see Figure 1).

While Food for Peace nonemergency programs address the root causes of food insecurity and seek to build resilience among vulnerable populations, FFP Title II emergency programs seek to distribute immediate, life-saving food and nutrition assistance to populations in crisis. Assistance—primarily through food procured in the United States but also through market-based approaches—is meant for those suffering from hunger or starvation as a result of crises. Programs are short, many running between 12-18 months, and are primarily implemented by the United Nations' World Food Programme. In FY2018, some of FFP's largest Title II emergency responses were staged in South Sudan ($335 million), Yemen ($273 million), and Ethiopia ($198 million).19

As noted, Food for Peace works with the poorest of the poor, focusing on building resilience. Feed the Future works with communities ready for longer-term development and focuses more on agricultural systems strengthening and market development.20 Catholic Relief Services, for example, currently implements both FFP nonemergency and Feed the Future development programs in Ethiopia. The FFP Ethiopia nonemergency program includes rehabilitating small-scale irrigation systems, conducting assessments on conflict management, and developing "livelihood pathways" for beneficiaries. The FTF development program includes financial education and services training, the establishment of marketing groups, and training for local leaders on youth participation in economic and social development. In this case, Food for Peace is supporting resilience strategies and baseline asset-building, while Feed the Future is encouraging more diverse market engagement and economic development.21

The use of Food for Peace nonemergency assistance and Feed the Future development assistance can depend on their different statutory requirements and flexibilities. For example, all FFP nonemergency programs funded with Title II must include in-kind food distributions; FTF programs do not. FFP nonemergency programs have funding flexibility that FTF development programs do not: funding may be reprogrammed from nonemergency to emergency responses if a shock occurs during the course of a nonemergency program. This flexibility exists because Title II funding is authorized for both emergency and nonemergency programing (see the "Legislation" section). For example, a five-year FFP nonemergency program in Madagascar shifted some of its funding to emergency programming in 2015, when the southern part of the country was hit with a drought. Once emergency food needs were met in those areas, the program was able to refocus on nonemergency programming.22

|

|

Sources: Created by CRS based on Food for Peace Emergency Activities (https://www.usaid.gov/food-assistance/what-we-do/emergency-activities); Food for Peace Development Activities (https://www.usaid.gov/food-assistance/what-we-do/development-activities); Feed the Future (https://www.feedthefuture.gov/about/). Notes: This chart does not include the FFP Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP), which serves the same purpose and populations as FFP Title II but is authorized by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended by GFSA, and is appropriated through SFOPS appropriations (See "Legislation" and "Funding" for more information on EFSP). Arrows indicate USAID's intention to sequence these programs, from emergency assistance to longer-term development programs. |

In some instances, Food for Peace nonemergency and Feed the Future development programs pursue similar or overlapping programming. Where such overlap occurs, implementing partners often duplicate programs deliberately to smooth the sustainable sequencing of food security programs, from FFP nonemergency to FTF development programming.23

Program Coordination Within USAID

As Food for Peace nonemergency programs are meant to bridge the gap between emergency programming and longer-term development programs, FFP seeks to coordinate both within the office and with its BFS counterparts. Within FFP, the office's geographic teams manage nonemergency programs alongside emergency programs, and in many cases the same staff manage both types of programs. For example, an FFP officer managing a nonemergency program in Haiti would also be managing emergency programs in the country. This integration allows the office's geographic staff to leverage resources and approaches between nonemergency and emergency programs.

FFP officers also work with their Bureau for Food Security counterparts, both in Washington, DC, and in the field. FFP is a part of the Feed the Future target country selection process, and BFS works closely with FFP on its annual country selection process for new countries for FFP nonemergency resources and the subsequent program design for those countries. FFP also uses FTF indicators to measure progress toward programmatic goals in its program evaluations. In the field, BFS and FFP officers collaborate.

Legislation

The Food for Peace program was established in 1954 with the passage of the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-480). Title II of the act authorized the use of surplus agricultural commodities to "[meet] famine or other urgent relief requirements" around the world and provided the general authority for FFP development programs.24 Now referred to as the Food for Peace Act, the program has evolved to reflect changes in domestic farm policy and in response to foreign policy developments.25

Congress authorizes the majority of international food assistance programs, including the FFP program, in two pieces of legislation:

- The Farm Bill. Typically renewed every five years, legislation commonly referred to as the farm bill is a multiyear authorization that governs a range of agricultural and food programs. The majority of farm bill-authorized programs are domestic, but Title III includes the Food for Peace Act as Subtitle A. In the most recent farm bill, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334), Congress authorized programs through FY2023.26

- The Global Food Security Act of 2016 (GFSA). Congress enacted the Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195) to direct the President to coordinate the development of a whole-of-government global food security strategy and to provide food assistance pursuant to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195; 22 U.S.C. 2151 et seq.). The GFSA also amended Sections 491 and 492 of the 1961 Act (22 U.S.C. 2292 et seq.) to establish the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) under International Disaster Assistance authorities, which FFP uses to provide emergency food assistance primarily through market-based approaches such as local and regional procurement (LRP), vouchers, and cash transfers for food. An extension of GFSA (P.L. 115-266) was enacted in 2018 and authorizes programs through FY2023.

Food for Peace nonemergency programs, in particular the Title II in-kind commodity purchase and distribution components, have historically received considerable bipartisan support from a broad domestic constituency. This support is a result of the program's link to U.S. farmers and shippers through the farm bill's statutory requirements.27 While FFP emergency responses make up the majority of the U.S. in-kind programming, the nonemergency food assistance programs share the same domestic connections. In a prepared statement for the House Agriculture Committee in relation to a 2017 hearing on the farm bill, the chairperson of the USA Rice Farmers Board shared the board's support of U.S. international food aid programs, noting that while U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) commodity procurement-purchases comprise only between 1% and 2% of total rice exports, "it is important to the industry that we continue to play a strong role in providing our nation's agricultural bounty to those in need."28 In written testimony for the House Subcommittee on Agriculture Appropriations, the Senior Director of Policy and Advocacy at Mercy Corps stated that "from our decades of experience working in fragile states, we have found non-emergency FFP programs to be the leading US government tool, for building the resilience of families and communities to food insecurity…. [W]ith these investments, we can prevent and mitigate food security crises."29 Further, FFP has a close relationship with the U.S. maritime industry as a result of longstanding but evolving requirements that a percentage of FFP commodities be shipped on U.S.-flagged vessels. These agricultural cargo preference requirements can sometimes create tension; the U.S. Maritime Administration asserts that agricultural cargo preference is critical to maintaining U.S. sealift capacity while FFP often expresses concern about how the increased cost of adhering to agricultural cargo preference affects its ability to meet the needs of the world's most food insecure populations. Despite this tension, the maritime industry remains engaged and active in FFP programming and has been a vocal advocate for the commodity-based programs.30 These historic links to the U.S. agriculture and maritime industries have been a significant factor when Congress considers legislation.

Funding

Consistent with the two authorization vehicles described above, food assistance funds are appropriated through both Agriculture appropriations (for farm bill-authorized programs) and Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations (for GFSA-authorized programs). Funds for nonemergency programs come from two accounts:

- The Food for Peace Title II Grants account within the Foreign Agricultural Service in Agriculture appropriations. FFP has received Food for Peace Title II Grants since its establishment.

- The Development Assistance (DA) account within SFOPS appropriations. FFP receives DA funds—designated as Community Development Funds (CDF)—from BFS to complement its Title II nonemergency resources and improve coordination between FFP and BFS.31 First legislated in FY2010, Congress intended CDF funds be used to help FFP reduce its reliance on monetization—the practice of partners selling U.S. commodities on local markets and using the proceeds to fund nonemergency programs. The level of CDF that FFP receives from BFS is not required by law; however, Congress has designated funds for CDF in the report accompanying annual appropriations (sometimes referred to as a "soft earmark") to which USAID has adhered each fiscal year.

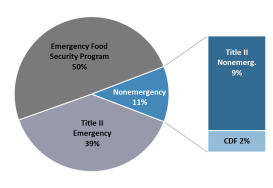

|

|

Source: Created by CRS based on FY2018 FFP Annual Report. Notes: CDF = Community Development Funds. Title II Emergency and Nonemergency funding are under the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Committees and Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittees. Emergency Food Security Program and CDF are under the jurisdiction of the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations Committees and SFOPS Appropriations Subcommittees. |

FFP receives additional funding for emergency food programs through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account within SFOPS appropriations. In FY2010, FFP started receiving IDA funds for the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) to supplement its Title II emergency funds.

In FY2018, Food for Peace received nearly half of its resources through Agriculture appropriations (see Figure 2). Of its overall funding, FFP used 11% ($431 million) for nonemergency programs—funded both through Title II and CDF—and 89% ($3.250 billion) for emergency programs. As previously mentioned, this was a marked change from the early years of the FFP program. When the Title II program was established, nonemergency programs constituted 65% of funding. While their share of overall programming rose in the first few years of the program—in 1959, they made up 83% of Title II programming—the share steadily declined in the following decades. By 2007, nonemergency programming accounted for 20% of Title II funds (see Figure 3). The following year, Congress established a minimum level (in U.S. dollars) of nonemergency food assistance in the 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246). The nonemergency minimum has been maintained in subsequent authorizations but has fallen by $10 million since it was first added to the bill (see Table 1). The most recent farm bill (P.L. 115-334), enacted in December 2018, set the minimum level of nonemergency food assistance at $365 million but allowed for Community Development Funds and the Farmer-to-Farmer Program funds to be counted toward the minimum.32

Table 1. Minimum Levels of Nonemergency Food Assistance, FY2009-FY2023

(levels designated in statute)

|

Fiscal Year |

Minimum Level of Nonemergency Food Assistance |

|

2009 |

$375 |

|

2010 |

$400 |

|

2011 |

$425 |

|

2012 |

$450 |

|

2013 |

— |

|

2014-2018 |

$350 |

|

2019-2023 |

$365 |

Sources: P.L. 110-246, P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-79, and P.L. 115-334.

Notes: The 2008 farm bill determined nonemergency minimum levels for FY2009-FY2012. The farm bill was extended for one fiscal year before the 2014 farm bill set a nonemergency minimum for FY2014-FY2018. Congress did not specify a nonemergency minimum for the FY2013 extension (Title VII of P.L. 112-240). For FY2019-FY2023, FFP is authorized to count Community Development Funds and Farmer-to-Farmer Program funds toward the $365 million nonemergency minimum.

|

|

Sources: Created by CRS based on Foreign Aid Explorer (explorer.usaid.gov) for FY1955-FY1991; U.S. Agency for International Development International Food Assistance Reports for FY1992-FY2017; Annual Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP) Reports, FY2010-FY2018; FFP FY2017 and FY2018 Annual Reports. |

Issues for Congress

The 116th Congress may be interested in a number of issues related to Food for Peace nonemergency programs. Areas of interest may include proposed and ongoing reforms to the FFP program funding and structure that could change both how nonemergency programs fit into the broader landscape of U.S. international food assistance programs, and the means through which the program is funded.

Proposed Elimination of Title II Funding and Food Aid Reform

Since FY2018, the Trump Administration has proposed eliminating funding for the entire FFP Title II program—both emergency and nonemergency programs—on the basis that doing so would "streamline foreign assistance, prioritize funding, and use funding as effectively and efficiently as possible."33 In its FY2020 foreign assistance budget request, the Administration referred to providing Title II food aid as "inefficient."34 Instead of relying on the FFP Title II program, which is funded through Agriculture appropriations, the Administration suggests providing food assistance solely through accounts funded by SFOPS appropriations.35 The Administration also proposes reducing SFOPS appropriations, indicating a preference for an overall reduction in funding for U.S. foreign assistance, including international food assistance programs.36

The Trump Administration is not the first to suggest significant changes to U.S. international food assistance programs. The Obama Administration also pursued a food aid reform agenda, proposing in its FY2014 budget request to shift all FFP Title II funds into three SFOPS assistance accounts. According to the Obama Administration, the proposed changes would have increased the flexibility, timeliness, and efficiency of U.S. international food assistance and allowed the programs to reach an additional "4 million more people each year with equivalent funding."37

|

The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334) The 2018 farm bill authorized the Food for Peace Title II program through FY2023 and made some changes to parts of the program, some of which had been proposed in earlier legislation and food aid reform efforts. These included, but were not limited to, eliminating the requirement to monetize at least 15% of FFP Title II commodities and instead providing a permissive authority to monetize, allowing Community Development Funds and Farmer-to-Farmer funds to count toward the nonemergency minimum assistance level, and increasing the maximum allocation for program oversight, monitoring, and evaluation from $17 million annually to 1.5% of annual FFP Title II appropriated funds.38 |

While to date Congress has not accepted any proposals to defund Title II, there have been efforts on Capitol Hill to change parts of the Title II program. For example, in the 115th Congress, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairperson Bob Corker and House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairperson Edward Royce both introduced versions of the Food for Peace Modernization Act, with bipartisan support (S. 2551 and H.R. 5276, respectively). The two bills would have made changes to the Title II program—including eliminating the requirement to purchase all Title II food aid commodities in the United States and removing the monetization requirement—in an effort to reduce cost and gain efficiency.39 Neither bill received further consideration, but some elements of the proposals were incorporated into the most recent farm bill (P.L. 115-334).

In FY2018 and FY2019, Congress did not accept Administration proposals to eliminate Title II funding, and for FY2020, the House-passed Agriculture appropriations include $1.85 billion for Title II. As Congress considers its annual appropriations and future authorization measures, Members may consider how to balance calls for reform with the priorities and vested interests of domestic constituencies, including agricultural interests and development groups, and how the often conflicting viewpoints may affect the effectiveness and efficiency of the Title II nonemergency programs.

Nonemergency Programs in the Context of USAID's Transformation Initiative40

As part of USAID's internal reform initiative, referred to as Transformation, the agency is planning to merge the FFP Office with the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) into a new Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (HA). OFDA is currently responsible for leading the U.S. government response to humanitarian crises overseas. In creating a new HA bureau, USAID would be consolidating its food (currently administered by FFP) and nonfood (currently administered by OFDA) humanitarian responses in an effort to remove potential duplication and present a more unified and coherent U.S. policy on humanitarian assistance on the global stage. In the new HA bureau, FFP and OFDA would no longer remain separate from one another with independent functions; instead, they would be consolidated into one bureau comprising eight offices—three geographically focused (Africa; Asia, Latin America, and Caribbean; and Middle East, North Africa, and Europe) and five technical (covering issues such as award management, program quality, donor coordination, and business operations, among others). (See Appendix B.)

The humanitarian community remains engaged with the U.S. government on this proposal and its potential effects on the broader efficiency, effectiveness, and coordination of humanitarian assistance. Some food assistance stakeholders have raised concerns about the dissolution of FFP and its potential impact on Title II programming. According to a USAID congressional notification on the intent to form the HA bureau, Title II nonemergency programming would remain in the new HA bureau, though it is unclear how that arrangement will look in practice.41 For the moment, USAID is planning to have the new HA geographic offices be responsible for managing both emergency and nonemergency Title II programming; however, a number of details need to be worked out by USAID leadership. These include whether and how nonemergency programs will be incorporated into larger disaster risk reduction efforts, and how the nonemergency programs will fit in with the programs to be managed by the new Bureau for Resilience and Food Security.42

As part of its Transformation process, USAID has held a number of consultations with Members of Congress. While the structural redesign is underway (HA is currently slated to be operational by the end of 2020, though implementation timelines may change), Congress has opportunities to provide feedback and guidance to the agency as it finalizes office-level details.

Separation of Food for Peace Nonemergency and Feed the Future Development Programs

Some policymakers have questioned why two different offices within USAID are responsible for similar programming, and have suggested either moving FFP's nonemergency portfolio to BFS or vice versa. In either consolidation scenario, the program could potentially benefit from increased coordination. For example, having one office manage all programming and present a unified voice to all stakeholders (including Congress) may reduce communication and coordination challenges. However, USAID could face significant tradeoffs in both consolidation scenarios.

If FFP's nonemergency portfolio were to move to USAID's Bureau for Food Security, the programs could lose their focus on serving the most vulnerable populations. Unlike Food for Peace, Feed the Future does not focus its programs on the poorest of the poor, does not include in-kind food distributions in its projects, and cannot shift its funding to meet emergency needs should a shock occur. Were FFP nonemergency programming to move to BFS, these unique FFP qualities may be deprioritized in favor of the more traditional development model BFS has pursued with its Feed the Future programs. Additionally, during a disaster FFP often uses its nonemergency programs as a component in the overall emergency response, by either diverting existing resources or injecting new emergency resources to support an early response.

Conversely, if BFS programming were to move to the Office of Food for Peace, the FTF programs could be deprioritized in favor of emergency programming. As discussed earlier, emergency programs have grown to dwarf nonemergency programming in funding terms (see Figure 3). If emergency funding needs continue to rise consistent with their previous trajectory, the demands from the emergency portfolio could outpace and overtake the traditional development assistance, jeopardizing the FTF gains already made and risking future programming.

Use of Community Development Funds (CDF)

Since FY2010, Food for Peace has received Community Development Funds (CDF) from the Development Assistance account in SFOPs appropriations to support its nonemergency programs and reduce reliance on monetization. Over the years, FFP has grown to rely on CDF to pursue the full range of its nonemergency programs. Implementing partners have raised concerns that if the level of CDF funding were to drop, USAID would have to choose between routing CDF funds through BFS to FFP and fully funding BFS-administered programs. If FFP lost its CDF funding, it would likely need to return to using monetization to partially fund its nonemergency programs. To address this potential challenge, Congress could consider changes in legislation, including but not limited to the following:

- Increasing flexibilities in Title II funding, including the authorized level of Section 202(e).43 An increase in flexibility through Section 202(e) could mimic the programmatic flexibilities FFP has gained through the use of CDF, including interventions that do not rely on in-kind food distributions. Proposed increases in flexibility have been opposed by some FFP stakeholders, in particular U.S. agricultural commodity groups.

- Designating in law a specific CDF level for FFP—instead of using the "soft earmark" in the bill report—thereby guaranteeing a secure line of funding for FFP's nonemergency programs. This approach would likely be supported by the implementing partner community, as it would provide some assurance that the CDF level would remain constant from year to year. However, this approach could negatively affect Feed the Future programming if the overall DA funding were to drop. It also would institutionalize the coordination between FFP and BFS that the sharing of CDF has already propagated.

Congressional Oversight

The various U.S. international food assistance programs fall under two separate congressional committee jurisdictions, which some argue can reduce Congress's ability to pursue comprehensive, integrated oversight of these programs. In the nonemergency context, FFP Title II-funded programs fall under the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Committees and Agriculture Appropriations Subcommittees, but the CDF-funded programming falls under the jurisdiction of the Foreign Affairs and Foreign Relations Committees and SFOPS Appropriations Subcommittees (see Appendix A). FFP reports on both of these in the International Food Assistance Report (IFAR), the farm bill-mandated annual report to Congress, even though it is not required to include Community Development Funds. This report offers a complete perspective on the FFP nonemergency programs, but it does not contextualize the programs with the entire U.S. international food assistance landscape. The IFAR does not include Emergency Food Security Program or Feed the Future reporting, because both are overseen by the Foreign Affairs/Relations Committees and are subject to different reporting requirements. As such, no single report currently mandated by Congress captures the entirety of international food assistance.44

The two oversight jurisdictions also present unique challenges to USAID. The two committee groupings often have different (and sometimes competing) priorities, the push and pull of which can sometimes lead USAID and its implementing partners to shoulder a higher administrative burden than other programs that reside in only one jurisdiction. For example, FFP was subject to eight Government Accountability Office (GAO) audits from 2014 to July 2019, covering issues from the monitoring and evaluation of cash-based food assistance programs to how U.S. in-kind commodities are shipped and stored. By comparison, BFS was the primary subject for one GAO audit in that same time-frame.

Looking Ahead

With enactment of the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334), Food for Peace Title II nonemergency programs are authorized through FY2023. However, the Administration continues to propose the elimination of the FFP Title II program in its annual budget requests. By moving forward with USAID's Transformation initiative, the Administration is implementing changes to organizational structures through which nonemergency food assistance programs are administered. Congress may consider addressing its priorities for FFP nonemergency programs in annual appropriations legislation, stand-alone bills that address certain components of the program, and Transformation-related consultations.

Appendix A. U.S. International Food Assistance Programs

This graphic illustrates the suite of U.S. international food assistance programs, including their administering agency and congressional jurisdiction. The programs highlighted in this graphic are the nonemergency programs discussed in this report.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS, based on information from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Agency for International Development. Notes: The Feed the Future Initiative is not listed in this matrix as it is a whole-of-government approach that includes most of these programs, among others. The programs highlighted in this graphic are the programs discussed in this memorandum. SFOPS = Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; USAID = U.S. Agency for International Development; IDA = International Disaster Assistance; DA = Development Assistance. |

Appendix B. USAID's Proposed Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Policy Determination Definition of Food Security, PD-19, April 13, 1992, https://www.marketlinks.org/sites/marketlinks.org/files/resource/files/USAID%20Food%20Security%20Definition%201992.pdf. |

| 2. |

Foreign Aid Explorer (explorer.usaid.gov) for FY1959; U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Food for Peace, Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report, May 23, 2019, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/FY2018_FFP_Annual_Report_508_compliant.pdf. |

| 3. |

The Obama Administration established the Feed the Future initiative; Congress specifically authorized the initiative in P.L. 114-195. For more information, see CRS Report R44727, Major Foreign Aid Initiatives Under the Obama Administration: A Wrap-Up, by Marian L. Lawson. |

| 4. |

In its publications, FFP often refers to its nonemergency programs as development programs. This report, however, refers to these programs as nonemergency programs, consistent with the legislative language. |

| 5. |

For information on the various other U.S. international food assistance mechanisms, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview, by Alyssa R. Casey. |

| 6. |

Office of Food for Peace, Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report. |

| 7. |

See FFP's Development Activities at https://www.usaid.gov/food-assistance/what-we-do/development-activities. |

| 8. |

Select examples chosen from U.S. Agency for International Development, "Tuendelee Pamoja II" Development Food Security Activity (DFSA) Project, FY 18 1st Quarter Report (October-December 2017), February 26, 2018, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00SX3V.pdf. |

| 9. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Food for Peace, Food for Peace FY2017 Food Assistance Tables, July 9, 2018, https://www.usaid.gov/documents/1866/food-peace-fy-2017-food-assistance-tables. |

| 10. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Food for Peace, Fiscal Year 2015: Title II Request for Applications Title II Development Food Assistance Project, Country Specific Information: Bangladesh, Washington, DC, April 8, 2015. |

| 11. |

CARE, Bangladesh, SHOUHARDO III Program, FY18 Annual Results Report, December 20, 2018, https://dec.usaid.gov/dec/GetDoc.axd?ctID=ODVhZjk4NWQtM2YyMi00YjRmLTkxNjktZTcxMjM2NDBmY2Uy&rID=NTE2NTQ2&pID=NTYw&attchmnt=True&uSesDM=False&rIdx=MjcwODkw&rCFU=. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TJKT.pdf. |

| 12. |

Monetization is a process by which implementing partners sell U.S. in-kind commodities in local markets to fund their nonemergency programs. Monetization used to be a requirement in the farm bill; the most recent farm bill (P.L. 115-334) eliminated the monetization requirement, instead replacing it with a permissive authority. Analysts have found that in practice, monetization loses 20-25 cents on the dollar (see, for example, Erin C. Lentz, Stephanie Mercier, and Christopher B. Barrett, International Food Aid and Food Assistance Programs and the Next Farm Bill, American Enterprise Institute, October 2017, p. 8, http://www.aei.org/publication/international-food-aid-and-food-assistance-programs-and-the-next-farm-bill/). Bangladesh is the only country in which FFP projects include a monetization component. |

| 13. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Food for Peace, International Food Assistance Report, Fiscal Year 2018, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TQSC.pdf. |

| 14. |

Food for the Hungry/DRC, Tuendelee Pamoja II Development Food Security Project, FY 19 1st Quarter Report (October-December 2018), February 15, 2019, https://dec.usaid.gov/dec/GetDoc.axd?ctID=ODVhZjk4NWQtM2YyMi00YjRmLTkxNjktZTcxMjM2NDBmY2Uy&rID=NTE3MTg1&pID=NTYw&attchmnt=True&uSesDM=False&rIdx=MjcxNTI2&rCFU=. |

| 15. |

International Food Assistance Report, Fiscal Year 2018. |

| 16. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Office of Food for Peace, Fiscal Year 2014: Title II Request for Applications Title II Development Food Assistance Programs, Country Specific Information: Malawi, Washington, DC, January 3, 2014. |

| 17. |

Project Concern International Malawi, Njira: Pathways to Sustainable Food Security, FY18 Annual Results Report, November 5, 2018, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TJKT.pdf. |

| 18. |

International Food Assistance Report, Fiscal Year 2018. |

| 19. |

International Food Assistance Report, Fiscal Year 2018. |

| 20. |

USAID's Office of Food for Peace, 2016-2025 Food Assistance and Food Security Strategy, October 6, 2016, p. 22, https://www.usaid.gov/FFPStrategy. |

| 21. |

FY2019 Quarter 1 Reports for AID-FFP-A-16-00005 and AID-663-A-17-00005, accessed through the Development Experience Clearinghouse (dec.usaid.gov). |

| 22. |

Example shared at a June 20, 2019, event on Capitol Hill hosted by Catholic Relief Services. |

| 23. |

Per conversations with implementing partner representatives in June 2019. |

| 24. |

Congress first used the term "nonemergency" to refer to these programs in the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-127). |

| 25. |

Congress renamed the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954 the Food for Peace Act in P.L. 110-246, Title III, Subtitle A, Section 3001. |

| 26. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11126, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: What Is the Farm Bill?, by Renée Johnson and Jim Monke. For greater detail on the 2018-enacted farm bill, see CRS Report R45525, The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison, coordinated by Mark A. McMinimy. |

| 27. |

Statute requires that nearly all agricultural commodities procured and distributed using Food for Peace Title II funds be produced in the United States. This requirement has kept FFP connected with U.S. farmers since the program's establishment. Statute requires at least 50% of all U.S. government-financed cargoes be shipped on U.S. flag vessels. As such, FFP relies on the cargo fleet to transport at least half of its U.S. in-kind commodities. |

| 28. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Agriculture, The Next Farm Bill, 115th Cong., 1 sess., April 4, 2017, p. 983. |

| 29. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies, Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations for 2018. Part 2: Statements of Interested Individuals and Organizations, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, FDA, and Related Agencies Appropriations to consider FY2018 budget requests of USDA, FDA, and related agencies., 115th Cong., 1st sess., January 1, 2017, pp. 157-158. |

| 30. |

For a full explanation and discussion of agricultural cargo preference and the resulting tension between USAID and the maritime industry, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview, by Alyssa R. Casey. |

| 31. |

For more information on FFP's funding, see U.S. International Food Assistance Funding Fact Sheet at https://www.usaid.gov/documents/1866/food-peace-funding-overview. |

| 32. |

Community Development Funds (CDF) are appropriated each year through the State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriation. USAID then allots a portion of CDF to the Office of Food for Peace to help fund its nonemergency programs. The Farmer-to-Farmer program is authorized through the Food for Peace Act (Title V) and funded through Agriculture appropriations. USAID's Bureau for Food Security implements the Farmer-to-Farmer program. The 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334) was the first to allow both CDF and Farmer-to-Farmer to count toward the nonemergency minimum requirement. |

| 33. |

United States Department of Agriculture, FY2018 Budget Summary, p. 25, https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USDA-Budget-Summary-2018.pdf. |

| 34. |

United States Department of Agriculture, FY2020 Budget Summary, p.32, https://www.obpa.usda.gov/budsum/fy2020budsum.pdf. |

| 35. |

If applied to accounts appropriated in FY2019, those would include International Disaster Assistance and Development Assistance funds. If Congress were to accept the Administration's proposal for FY2020, those accounts would be International Humanitarian Assistance and Economic Support and Development Fund. For more information on the proposed accounts, see U.S. Department of State, FY2020 Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FY-2020-CBJ-FINAL.pdf. |

| 36. |

For more information on the Trump Administration's FY2020 proposal to consolidate humanitarian funding accounts, see the "Proposed Account Consolidations and Restructuring" and "Humanitarian Assistance" sections in CRS Report R45763, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs: FY2020 Budget and Appropriations, by Cory R. Gill, Marian L. Lawson, and Emily M. Morgenstern. |

| 37. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, The Future of Food Assistance: U.S. Food Aid Reform, 2013, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1869/USAIDFoodAidReform_FactSheet.pdf. |

| 38. |

For more information on changes made in the most recent farm bill, see the Trade Section and Table 7 in CRS Report R45525, The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison, coordinated by Mark A. McMinimy. |

| 39. |

For more information on food aid reform efforts, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview, by Alyssa R. Casey. |

| 40. |

For more information on Transformation, see CRS Report R45779, Transformation at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), coordinated by Marian L. Lawson. |

| 41. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, Merger and Restructuring of the Offices of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and Food for Peace into the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, Congressional Notification #1, July 27, 2018, pp. 1-13, https://pages.devex.com/rs/685-KBL-765/images/USAID-Congressional-Notifications.pdf. |

| 42. |

Per conversations with USAID officials in June 2019. |

| 43. |

Section 202(e) of the Food for Peace Act (7 U.S.C. §1722(e)) authorizes FFP to use a portion of Title II funds to "enhance" Title II projects, including through market-based interventions like food vouchers and cash transfers. The notion is that "enhancing" projects grants FFP the flexibility to use the right intervention—whether in-kind assistance or market-based assistance—at the right time to reach beneficiaries in need in a cost-effective manner. |

| 44. |

For Title II programming, FFP submits to Congress an annual International Food Assistance Report that, until FY2018, was a joint report with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. FFP also submits to Congress an Emergency Food Security Program report that details its use of IDA/EFSP funds. Separately, Congress receives reports on FTF per the requirements outlined in the Global Food Security Act. Since FY2016, FFP has published a public annual report that provides an overview of all programs across its funding streams but that report is not required by law. |