Major Foreign Aid Initiatives Under the Obama Administration: A Wrap-Up

Over the past few Administrations, Congress has maintained strong interest in and support for the broad global development areas of global health, food security, and climate-related aid and investment. The Obama Administration built its foreign assistance programming around the priorities and practices it identified in the 2010 Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) on Global Development, which identified broad-based economic growth and democratic governance as overarching U.S. development priorities. In particular, the Obama Administration focused on three key initiatives: the Global Health Initiative (GHI), the Global Climate Change Initiative, and the Global Food Security Initiative (Feed the Future). While built on the foundation of existing programs, each initiative was intended to bring new focus, improve coordination, and boost funding to the aid sectors it supported. The initiatives shared several principles, including an emphasis on building host country capacity, investing in innovation and research, using whole-of-government strategies, being results oriented, leveraging global partnerships, and applying a cross-sectoral approach.

The Global Health Initiative was launched to improve health outcomes through strengthened health systems and increased and integrated investments in maternal and child health, family planning, nutrition, and infectious diseases. GHI as a distinct platform faded away over the course of the Administration, but progress in global health outcomes that began during the George W. Bush Administration have been largely sustained during the Obama Administration, and the role of multilateral programs was elevated. Some assert that implementation of the initiative was inadequate, but others contend that U.S. global health programs were strong and effective before President Obama took office, and the scaled back emphasis on GHI reflects recognition that little change was needed.

Feed the Future aimed to accelerate inclusive growth in the agriculture sector of partner countries and improve nutritional status, particularly of women and girls. Feed the Future is the only original Obama foreign aid initiative specifically authorized in law (the Global Food Security Act of 2016, P.L. 114-195). The law established a specific statutory foundation for global food security assistance, required the President to develop a whole-of-government strategy to promote global food security (released in October 2016), and authorized funding to support the strategy (just over $1 billion per year) for FY2017 and FY2018. The initiative and the legislative support provided by the GFSA have given food security and agricultural development a more prominent role in the U.S. development policy and budget.

The Global Climate Change Initiative ramped up U.S. climate-related aid to developing countries, with a focus on promoting clean energy, sustainable landscapes, and climate change resilience and adaptation. While Congress has not always supported GCCI programs and funding, the United States has met its international pledges, and the initiative has reportedly had an impact on U.S. development practice, with USAID now assessing and addressing climate risks and climate change mitigation opportunities in all new country strategies. However, by promoting its climate agenda primarily through executive action, without seeking the approval of Congress, the Obama Administration has made any progress in this area vulnerable to dismantlement.

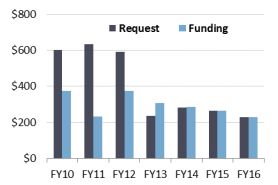

Reported results have been mixed, but the Obama Administration’s global development initiatives sustained efforts from the Bush Administration on global health and climate change and brought new attention to food security and agricultural development. While budget pressures have tamped down growth in the foreign aid budget, the portion of U.S. bilateral development assistance obligated for global health, agricultural development, and environment programs—more than one-third of total economic aid from FY2012 to FY2015—increased under the Obama Administration, continuing a trend that began under the Bush Administration. The incoming Administration and the 115th Congress may examine these initiatives as they consider future U.S. global development policy. Interest in these issues, if not these specific initiatives, can be expected to continue beyond the end of the Obama Administration.

Major Foreign Aid Initiatives Under the Obama Administration: A Wrap-Up

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Global Health Initiative

- Legislation

- Funding

- Results

- Feed the Future

- Legislation

- Funding

- Results

- Global Climate Change Initiative

- Legislation

- Funding

- Results

- Conclusion

Figures

- Figure 1. Environment, Global Health and Agriculture Sector Foreign Aid Obligations, FY2001-FY2015

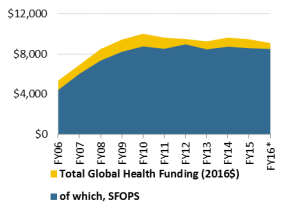

- Figure 2. Global Health Funding, Whole of Government and SFOPS

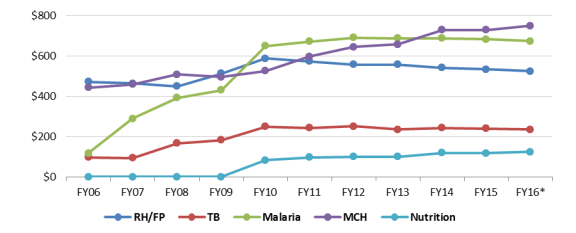

- Figure 3. Global Health Funding by Select Subsector

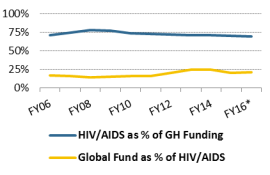

- Figure 4. Annual HIV/AIDS and Global Fund as Portion of GHP Funding

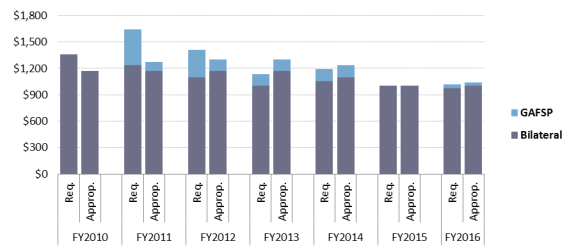

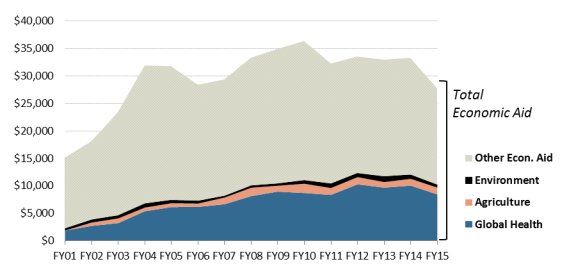

- Figure 5. Requested and Appropriated Funds for Bilateral Food Security Aid and U.S. Contributions to the GAFSP, FY2010-FY2015

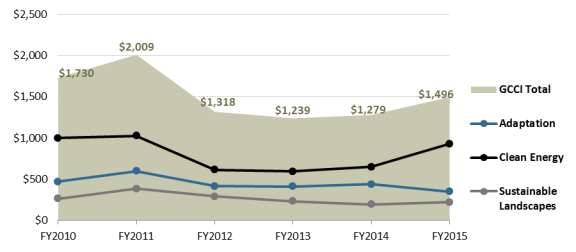

- Figure 6. Appropriated GCCI Funding by Pillar and Year, FY2010-FY2015

- Figure 7. Climate Investment Fund Contributions, Requested and Actual, FY2010-FY2016

Summary

Over the past few Administrations, Congress has maintained strong interest in and support for the broad global development areas of global health, food security, and climate-related aid and investment. The Obama Administration built its foreign assistance programming around the priorities and practices it identified in the 2010 Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) on Global Development, which identified broad-based economic growth and democratic governance as overarching U.S. development priorities. In particular, the Obama Administration focused on three key initiatives: the Global Health Initiative (GHI), the Global Climate Change Initiative, and the Global Food Security Initiative (Feed the Future). While built on the foundation of existing programs, each initiative was intended to bring new focus, improve coordination, and boost funding to the aid sectors it supported. The initiatives shared several principles, including an emphasis on building host country capacity, investing in innovation and research, using whole-of-government strategies, being results oriented, leveraging global partnerships, and applying a cross-sectoral approach.

- The Global Health Initiative was launched to improve health outcomes through strengthened health systems and increased and integrated investments in maternal and child health, family planning, nutrition, and infectious diseases. GHI as a distinct platform faded away over the course of the Administration, but progress in global health outcomes that began during the George W. Bush Administration have been largely sustained during the Obama Administration, and the role of multilateral programs was elevated. Some assert that implementation of the initiative was inadequate, but others contend that U.S. global health programs were strong and effective before President Obama took office, and the scaled back emphasis on GHI reflects recognition that little change was needed.

- Feed the Future aimed to accelerate inclusive growth in the agriculture sector of partner countries and improve nutritional status, particularly of women and girls. Feed the Future is the only original Obama foreign aid initiative specifically authorized in law (the Global Food Security Act of 2016, P.L. 114-195). The law established a specific statutory foundation for global food security assistance, required the President to develop a whole-of-government strategy to promote global food security (released in October 2016), and authorized funding to support the strategy (just over $1 billion per year) for FY2017 and FY2018. The initiative and the legislative support provided by the GFSA have given food security and agricultural development a more prominent role in the U.S. development policy and budget.

- The Global Climate Change Initiative ramped up U.S. climate-related aid to developing countries, with a focus on promoting clean energy, sustainable landscapes, and climate change resilience and adaptation. While Congress has not always supported GCCI programs and funding, the United States has met its international pledges, and the initiative has reportedly had an impact on U.S. development practice, with USAID now assessing and addressing climate risks and climate change mitigation opportunities in all new country strategies. However, by promoting its climate agenda primarily through executive action, without seeking the approval of Congress, the Obama Administration has made any progress in this area vulnerable to dismantlement.

Reported results have been mixed, but the Obama Administration's global development initiatives sustained efforts from the Bush Administration on global health and climate change and brought new attention to food security and agricultural development. While budget pressures have tamped down growth in the foreign aid budget, the portion of U.S. bilateral development assistance obligated for global health, agricultural development, and environment programs—more than one-third of total economic aid from FY2012 to FY2015—increased under the Obama Administration, continuing a trend that began under the Bush Administration. The incoming Administration and the 115th Congress may examine these initiatives as they consider future U.S. global development policy. Interest in these issues, if not these specific initiatives, can be expected to continue beyond the end of the Obama Administration.

Introduction

The Obama Administration built its foreign assistance programming around the priorities and practices it identified in the 2010 Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) on Global Development.1 The PPD was the first of its kind and sought to elevate global development as a pillar of American foreign policy, alongside defense and diplomacy. It identified broad-based economic growth and democratic governance as overarching U.S. development priorities and focused on three key initiatives as a means to support those priorities: the Global Health Initiative (GHI), the Global Climate Change Initiative, and the Global Food Security Initiative (Feed the Future). While built on the foundation of existing programs, each initiative was intended to bring new focus, improve coordination, and boost funding to the aid sectors it supports.

The Obama Administration followed a particularly active era in U.S. support for global development. Under the George W. Bush Administration, foreign assistance levels more than doubled, a new foreign aid agency was created (the Millennium Challenge Corporation, MCC), and the Bush Administration established, with strong congressional support and involvement, one of the largest foreign aid programs in history—the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The Obama Administration built upon these efforts, although within the context of an increasingly constrained budget and political environment. Within months of the PPD's release in 2010, the Republican Party won majority control in the House of Representatives, with priorities often at odds with the Democratic Administration. Concerns about the budget deficit and enactment of the Budget Control Act the next year reduced spending levels across the federal government, thereby reducing prospects for new investments in development assistance programs. Perhaps as a result of this political dynamic, the Obama Administration did not establish new aid programs, with the arguable exception of Power Africa,2 but rather sought to reconfigure and refocus existing programs. Some analysts suggest that the Administration was effectively limited after 2010 to efforts that were budget neutral and required little or no support from Congress.3

Specific funding for the global health, climate change, and food security initiatives was first requested in the FY2011 International Affairs budget, but support through ongoing program funds was provided in FY2010 appropriations. Congress has generally not used the initiatives as funding frameworks but has supported the activities they encompass to varying degrees. The portion of U.S. bilateral development assistance obligated for global health, agricultural development, and environment programs—more than one-third of total economic aid from FY2012 to FY2015—has increased under the Obama Administration, continuing a trend begun under the Bush Administration (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Environment, Global Health and Agriculture Sector Foreign Aid Obligations, FY2001-FY2015 (in millions of constant 2015 $) |

|

|

Source: USAID Query Database. |

While each of the Obama Administration initiatives is distinct, several common threads run through them, reflecting the Obama Administration's general global development strategy and priorities, as outlined in the PPD:

- Focus on Host Country Capacity. The policy sought to improve aid effectiveness by focusing efforts on partner countries and regions where the conditions seem most amenable to sustained progress. This took the form of "fast track" countries in the Global Health Initiative and "focus countries" in Feed the Future. One aspect of this focus on building partner capacity was an attempt to shift away from a pattern of emergency response aid toward a preventive posture (e.g., agricultural development aid instead of emergency food aid, or increasing capacity of governments to predict floods and other climate change impacts rather than providing post-disaster response). This selective approach is challenged by diplomatic pressure to spread aid broadly, potential conflict between U.S. priorities in a country or region, and concern that aid may be most needed in places with the least government and institutional capacity.

- Investment in Innovation and Research. The Obama Administration sought to foster development-focused research as a means to incentivize and identify "game-changing" innovations such as new vaccines, weather-resistant crop varieties, and clean energy technology. The U.S. Global Development Lab within USAID is perhaps the most significant manifestation of this PDD priority, but there are initiative specific components as well. For example, a Food Security Innovation Center (FSIC) was established at USAID as part of Feed the Future, which oversees numerous collaborative research programs, many of which predate the initiative.

- Whole of Government. Each initiative, as described in its roll-out and strategy documents, involves several U.S. government agencies beyond the primary international development actors (the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the State Department, and the MCC). The Obama Administration emphasized that this "whole of government" approach was intended to bring the full range of U.S. expertise and resources to the challenges addressed by the initiatives, as well as to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of existing, but often uncoordinated, international activities. The whole of government approach may also be a way to identify a broader range of ongoing U.S. government funding that can be attributed to these objectives and related international commitments. In practice, this approach has faced coordination challenges, caused in part by varying congressional committee jurisdictions and lack of legislative or executive authority to compel cross-agency coordination and cooperation. The fractured oversight and lack of coordinating authority has also presented challenges for tracking initiative spending.

- Results-Oriented. The PPD emphasized the use of metrics by which to measure development progress and the accountability of recipients for achieving results. The initiatives were established with specific goals and, except for the Global Climate Change Initiative (perhaps due to the longer time frames required to return accurate environmental assessments), specific performance indicators. This was not a new concept, but reaffirmed an ongoing whole-of-government effort stemming from the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993, updated in 2010, which established unprecedented statutory requirements for all U.S. government agencies regarding the establishment of goals, performance measurement indicators, and submission of related plans and reports to Congress. The Obama Administration emphasized tracking results and impacts of foreign aid generally, updating the evaluation policies of USAID, State and MCC between 2010 and 2012 to require more frequent and methodologically rigorous evaluation of aid programs.4 Congress supported this effort as well, passing legislation in 2016, the Foreign Aid Transparency and Accountability Act, that codified many of the new evaluation and reporting requirements. Nevertheless, measuring outcomes that can be attributed to U.S. aid interventions remains a significant challenge. Much of the results information reported for the initiatives is selective and is not the product of evaluations using control groups to identify impact.

- Global Partnership. All of the initiatives sprang from multilateral efforts such as the G8 food security summit or the U.N Framework Convention on Climate Change, and all have multilateral components, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the Global Agriculture and Food Security Fund, and the Green Climate Fund, among others. Furthermore, each initiative emphasizes working with private sector partners to bring greater resources and expertise to development challenges, a foreign assistance trend that predated the Obama Administration. The Obama Administration made efforts to expand the multilateral aspects of the initiatives, arguing that U.S. resources can be leveraged for greater impact through partnership with other donors and entities, including private sector actors. Congress has generally been less supportive of the multilateral aspects of the initiatives, citing oversight and governance concerns, among other things.

- Cross-Sectoral. One theme of the Obama development approach detailed in the PPD was the need to work across sectors and avoid the "stovepipe" approach for which foreign assistance, and particularly health aid, has sometimes been criticized. The global health initiative, for example, recognized that nutrition, clean water, and women's empowerment may be as important to healthy communities as vaccines and antiretroviral drugs. Agricultural development activities to promote food security also affect community resilience to climate change. The three initiatives all overlap to some degree in their objectives, creating opportunities for synergies but also confusion over the attribution of funding to one initiative or the other.

This report provides a brief overview of these initiatives as they were introduced, how they have evolved over the years, funding trends, reported results, and other areas of particular congressional interest and activity.

Global Health Initiative

U.S. investments in global health increased significantly under the George W. Bush Administration, primarily as a result of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Rather than create a new global health program aimed at a particular disease, President Obama emphasized the integration and coordination of ongoing global health efforts through an initiative he called the Global Health Initiative (GHI). The Administration launched the GHI in May 2009, calling on Congress to provide $63 billion over five years to "improve health outcomes through strengthened health systems, increased and integrated investments in maternal and child health, family planning, nutrition and infectious diseases including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases, and through a particular focus on improving the health of women, newborns and children."5 The approach was sometimes described as treating patients, not diseases, in contrast to the HIV-specific focus of PEPFAR. While GHI became the framework for all U.S. global health programs, the Administration identified eight "fast-track" countries (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Nepal, and Rwanda) in which to focus additional technical and management support to enable quick implementation and learning from the new approach.

The Administration established a small GHI coordinating office within the State Department, put together GHI country teams in 42 countries, and established GHI country strategies, all with the purpose of streamlining efforts across agencies and program silos. The 2010 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) outlined a plan by which leadership of GHI would shift to USAID when certain conditions were met.6 This transition never happened, however, and over the course of the Obama Administration the GHI as a distinct structure or strategy faded away. The "fast-track" country designation was no longer used. The GHI office closed in 2012, and its activities were integrated into the State Department's Office of Global Health Diplomacy. The Administration reportedly described this change as an elevation and cited the successful integration of GHI principles into country development plans.7 Others have commented that the office was ineffective and incapable of resolving interagency conflict, largely because it lacked the authority and designated funding to compel the cooperation of other federal entities.8 Most agency reports on global health stopped mentioning GHI after 2012, though annual congressional justifications for the international affairs budget continue to frame the global health request in the context of GHI.

Legislation

The GHI was never established in legislation, and the Administration did not seek authorizing legislation. Instead, it relied on existing authorities in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, and the PEPFAR authorization. It could be argued that by not seeking distinct authorization legislation, the Administration lost an opportunity to establish a stronger interagency coordinating authority.

Funding

GHI exists in 2016 largely as a funding framework within the international affairs budget. The Administration requests GHI funding primarily through the State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriation. Congress in turn appropriates funds not for GHI, but for Global Health Programs, the account that was established in FY2007 to combine appropriations for PEPFAR and the Maternal Health and Child Survival account. Additional global health funds have been provided over the years through appropriations for the Departments of Health and Human Services and Defense. For a detailed account of global health funding trends by agency, see CRS Report R43115, U.S. Global Health Assistance: FY2001-FY2016, by Tiaji Salaam-Blyther.

It appears from whole-of-government global health spending data that the initial GHI goal of $63 million over five years was not met. However, global health funding continued to grow early in the Obama Administration. In current dollars (adjusted for inflation), total global health funding leveled out after 2010 but remained historically high during a period of intense budget pressure (Figure 2). Congress and the President were largely in agreement over global health funding levels throughout the Obama Administration.

In several years of the Administration, Congress provided more funds than the Administration requested for global health, including every year since FY2013. While there were initial disparities between the Administration and Congress when it came to allocations for specific global health priorities—for example, the Administration asked for more than Congress provided for Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning/Reproductive Health in some early years of the Administration—sector requests and appropriations aligned fairy closely throughout much of the Obama Administration. Adjusted for inflation, funding for maternal and child health increased steadily during the Obama Administration, while funding for malaria and tuberculosis programs, and for reproductive health and family planning, increased in the early years of the Administration before leveling or even decreasing slightly. In addition, nutrition programs became a distinct global health programs sub-account as part of GHI, and have received slight but steady funding increases (Figure 3).

Aside from maintaing historically high funding levels for global health programs in general, two specific priorities of the GHI strategy appear to be reflected to a limited degree in the funding trends.

|

Figure 4. Annual HIV/AIDS and Global Fund as Portion of GHP Funding |

|

|

Source: Annual appropriations legislation, CRS calculations |

The portion of global health funding allocated to HIV/AIDS programs declined slightly but steadily during the administration, from 78% in 2008 to an estimated 70% in FY2016, consistent with the GHI goal of moving beyond the disease-specific focus and supporting broader health systems. A related trend is the increase in multilateral health aid, as represented by U.S. contributions to the Global Fund to Fight HIV, TB, and Malaria. Global Fund contributions increased in both dollar terms and as a portion of the economic assistance budget throughout the Obama Administration, perhaps reflecting the GHI emphasis on partnerships and leveraging the efforts of other donors.

Results

A focus on health outcomes was a key aspect of GHI, and the GHI strategy listed goals and targets in eight primary areas. A GHI website continued to present data related to the various global health focus areas after the GHI office closed, but the data have not been updated since July 2014. Table 1 compares the key goals detailed in the GHI strategy with recent results reported in a variety of U.S. global health program documents. Although these are not officially "GHI results," they show areas of continued progress in the individual program areas once encompassed by GHI.

|

Focus Area |

Goal |

Corresponding Results from Various Reports |

|

HIV/AIDS |

Support the prevention of more than 12 million new HIV/AIDS infections; provide direct support for more than 4 million people on treatment, support care for more than 12 million people, including 5 million orphans and vulnerable children. |

|

|

Malaria |

Halve the burden of malaria for 450 million people, representing 70% of the at-risk population in Africa. |

|

|

Tuberculosis |

Contribute to the treatment of a minimum of 2.6 million new TB cases and 57,200 drug-resistant cases of TB, and contribute to a 50% reduction in TB deaths and disease burden relative to the 1990 baseline. |

|

|

Maternal Health |

Reduce maternal mortality by 35% across assisted countries. |

|

|

Child Health |

Reduce under-5 mortality rates by 35% across assisted countries. |

|

|

Nutrition |

Reduce child undernutrition by 30% across assisted food insecure countries (in conjunction with Feed the Future). |

|

|

Family Planning/ |

Prevent 54 million unintended pregnancies by reaching a modern contraceptive prevalence rate of 35% across assisted countries and reducing from 24% to 20% the proportion of women aged 18-24 who have their first birth before age 18. |

|

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) |

Reduce the prevalence of 7 NTDs by 50% among 70% of the affected population. |

|

a. All results in this cell are reported in a 2016 PEPFAR Results Factsheet, available at https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/264882.pdf.

b. FY2017 International Affairs CBJ, p. 44.

c. 2016 Presidents Malaria Initiative annual report to Congress, p. 5.

d. All results in this cell are from the Annual Progress Report to Congress: Global Health Programs FY2014, p. 72.

e. Annual Progress Report to Congress: Global Health Programs FY2014, p. 54.

f. FY2017 International Affairs CBJ, p. 44.

g. Annual Progress Report to Congress: Global Health Programs FY2014, p. 37.

h. Annual Progress Report to Congress: Global Health Programs FY2014, p. 46.

i. FY2017 International Affairs CBJ, p. 44.

Source: Compiled by CRS from the 2011 United States Global Health Initiative Strategy Document, available at http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/136504.pdf. Results data are compiled from various sources, as indicated in the table notes.

The GHI strategy and results framework faded away over the course of the Administration, but progress in global health outcomes that began during the Bush Administration was largely sustained, and in some areas accelerated during the Obama Administration. Some assert that implementation of the initiative was poorly managed,9 while others contend that U.S. global health programs were strong and effective before President Obama took office, and that the scaled back emphasis on GHI as a unique approach reflects a recognition that little change was needed. Strong support from Congress suggests global health will likely continue to be the leading development assistance sector for years to come.

Feed the Future

The Obama Administration's global food security initiative was the U.S. response to the G8 Summit in L'Aquila, Italy, which was held in June 2009 to address the 2007-2008 global food price crisis.10 The proportion and absolute number of hungry people worldwide had risen to historic levels. At the summit, President Obama pledged U.S. investments of $3.5 billion over three years (FY2010 to FY2012) to a global hunger and food security initiative to address hunger and poverty worldwide. The U.S. commitment was part of a global pledge by the G20 countries and others of more than $20 billion. This represented a return to the U.S. and global development policy agenda of the 1960s and 1970s, which emphasized agricultural and rural development. The United States and other donors channeled a significantly smaller portion of aid funds to agricultural development activities in the 1990s and first decade of the 2000s.

In May 2010, the Administration officially launched the Feed the Future initiative and, in November 2010, established a Bureau for Food Security within USAID to lead implementation of the initiative. Also in 2010, a multidonor trust fund called the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP), administered by the World Bank, was established as the multilateral funding mechanism to fulfill the G8 Summit commitments.

Feed the Future emphasizes accelerating inclusive growth (affecting a broad range of participants, including small-scale farmers and women) in the agriculture sector of partner countries and improving nutritional status, particularly of women and girls. The initiative was built around five principles for sustainable food security first articulated at L'Aquila and endorsed at the 2009 World Summit on Food Security in Rome:

- supporting comprehensive strategies;

- investing through country-owned plans;

- improving stronger coordination among donors;

- leveraging effective multilateral institutions; and

- delivering on sustained and accountable commitments.

The initiative was also a means of focusing and coordinating previously existing U.S. agricultural development policies. Assistance was to be provided primarily to focus countries, of which there are currently 19, which USAID has identified as having the greatest needs, strongest host-country commitment and resources, potantial for agricultural led growth, and opportunities for regional synergies.11 For more detailed background information on Feed the Future, see CRS Report R44216, The Obama Administration's Feed the Future Initiative, by Marian L. Lawson, Randy Schnepf, and Nicolas Cook.

Legislation

Of the three Obama initiatives discussed in this report, Feed the Future is the only one that has been specifically authorized in law, though this authorization was enacted in the last year of the Obama Administration. The activities that constitute the initiative are authorized under the broad provisions of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, but Members of Congress chose to introduce legislation to specifically and permanently authorize an agriculture-focused global food and nutrition security strategy and programs with H.R. 1567, the Global Food Security Act of 2016, which was enacted by Congress and signed into law as P.L. 114-195 in July 2016.12 The law established a specific statutory foundation for global food security assistance, required the President to develop a whole-of-government strategy to promote global food security, and authorized funding to support the strategy (just over $1 billion per year) for FY2017 and FY2018.13 The required strategy was produced by the Administration in September 2016, and includes goals, objectives, and agency implementation plans for FY2017-FY2021.14

Funding

The Administration, working with Congress, easily met its Aquila pledge. Congress provides funding for Feed the Future programs primarily through the SFOPS appropriations bill. Congress does not specify a funding level for Feed the Future as a whole. Rather, it allocates funds (sometimes a specific amount and sometimes "no less than" a specific amount) for bilateral "food security and agricultural development" activities, which are implemented by USAID, MCC, the Peace Corps, and other agencies. In many years, a separate appropriation has been allocated for U.S. contributions to the GAFSP (administered by the Department of the Treasury), but recent appropriations legislation has not made a specific GAFSP allocation, instead stating that bilateral food security and agricultural development funds could be used for such a contribution.15 A portion of the Food for Peace program, funded through the Agriculture appropriation but implemented by USAID, is also counted in Feed the Future funding totals. The Administration determines whether or how to allocate these appropriated funds within the Feed the Future framework. As a result, it can be difficult to determine Feed the Future funding patterns based on appropriations acts. However, a look at Administration requests for Feed the Future and congressional appropriation for "food security and agricultural development" and GAFSP contributions year to year shows some interesting trends.

In the early years of the initiative, Administration requests significantly exceeded appropriated amounts, particularly with respect to GAFSP contributions. Since FY2013, however, appropriations have matched or exceeded Administration requests for food security activities, largely because the request for bilateral aid declined each year between FY2010 and FY2013. (Figure 5). In the longer view (Figure 1), agricultural development aid outlays over recent decades suggest that agricultural development became a higher priority within the foreign assistance budget, increasing from 2.2% of total economic aid in FY2005 to 4.5% in FY2015, and notably higher in real dollar terms than a decade prior. This trend began in the later years of the George W. Bush Administration and was maintained by the Obama Administration, even in the face of some early congressional resistance.

Results

To track the progress of the initiative, Feed the Future established two key impact indicators and several related output indicators. Table 2 summarizes some of the substantial but incomplete data on the two main goals of Feed the Future, as well as select output and outcome indicators that the Administration says can be directly attributed to U.S. government funding. All data are from the most recent report on Feed the Future progress.16

|

Goal |

Results Data from 2016 Progress Report |

|

Reductions in Poverty of 20% by 2017. |

Poverty had dropped between 7% and 36% within 11 of the 19 focus countries.a |

|

Reduction in Childhood Stunting of 20% by 2017. |

Child stunting has dropped between 4% and 40% within 8 of the 19 focus countries.a As of 2015, Cambodia, Honduras and Kenya were on track to exceed Feed the Future stunting reduction targets if they maintained their current rate of progress. |

|

Select Indicators |

Results Data from 2016 Progress report |

|

Hectares tended with improved technologies or management practices as a result of U.S. government assistance. |

5,329,462 in FY2015, of which 32% were tended by females. |

|

Children under 5 reached by U.S. government-supported nutrition programs. |

18,006,457 in FY2015, of which 51% were female. |

|

Value of incremental sales (collected at farm level) attributed to Feed the Future. |

$829,439,579 as of FY2015. |

Source: Compiled by CRS from the Feed the Future 2016 Progress Report, Growing Prosperity for a Food-Secure Future, pp. 4, 10-11.

Notes: The baseline data years used to calculate the change vary from country to country. Some country data covers the period 2010-2015, while in other countries the data period is as limited as 2013-2015.

a. Results reflect varying time periods. In Kenya, the country for which the greatest improvement is noted, the data covers 2008-2015, predating Feed the Future. In Guatemala, the relatively limited progress (6% reduction) may be because the period covered is only two years: 2013-2015.

While the data on poverty reduction and stunting is limited and shows mixed results, Feed the Future appears to be achieving some measure of success. One independent assessment of the initiative found that the Obama Administration has succeeded in focusing agricultural development aid in select focus countries, consistent with Feed the Future criteria on need and potential for effective partnership.17 The same assessment pointed out, however, that the initiative is not as transparent as it could be, that country ownership is lacking, and that Feed the Future appears to be more a USAID program than the whole-of-government effort it was proclaimed to be. The GFSA may address these issues, as it calls for presidential coordination for food security activities, not a USAID-led effort, and lists the agencies for which a detailed accounting of food security activities is required by the bill. The authorization of funding in GFSA, however, is for USAID. There is little doubt that Feed the Future and the legislative support provided by the GFSA have given food security and agricultural development a more prominent role in the U.S. development policy and budget. It is unclear, however, if these programs, and the principles by which they have been organized, will be a priority for the new administration and the 115th Congress.

Global Climate Change Initiative

As with the other initiatives, the Global Climate Change Initiative (GCCI) built on existing climate related efforts, adapted and scaled up to reflect evolving global efforts. Under the Clinton and George W. Bush Administrations, USAID was already pursuing environmental protection and adaptation activities, and the United States was already contributing to several multilateral climate investment funds, consistent with U.S. commitments stemming from the 1992 U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and subsequent related international agreements. The CGGI ramped up U.S. climate-related aid to developing countries, reflecting a proposal made jointly by developed countries under the December 2009 Copenhagen Accord, in which the Administration committed to working with other donors to provide "fast start" climate financing collectively approaching $30 billion during the period 2010-2012 (both public and private investment). Documents accompanying the 2010 PPD18 describe the initiative as focused on three key objectives:

- Investing in Clean Energy: The initiative sought to accelerate the deployment of clean energy technologies, policies, and practices as a means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions for energy generation and use. Much of the funding for this pillar was anticipated to be channeled through the World Bank's multilateral Climate Investment Funds (CIFs), which include the Strategic Climate Fund and the Clean Technology Fund, to take advantage of large-scale greenhouse gas reduction opportunities. Bilateral aid was focused on shaping policy and regulatory environments to ensure long-term sustainability.

- Promoting Sustainable Landscapes: As part of the "fast start financing" in the Copenhagen Accord, the Obama Administration committed $1 billion from 2010 to 2012 to support country plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). The Administration described this pillar as a cost-effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while providing sustainable development benefits.

- Supporting Climate Change Resilience and Adaptation: This pillar focused on helping the most vulnerable low-income countries to reduce the social, environmental, and economic impacts of climate change. A key aspect of this effort was integrating climate change considerations and solutions into development activities in all relevant sectors.

Aside from the focus areas, the Administration identified several ways in which the GCCI promoted the Administration's broader development policy, including promoting country ownership, promoting climate solutions that spur economic growth, ensuring sustainability of economic growth gains through actions that protect investments, strengthening governance and inclusive planning processes, and investing in potentially game-changing science and technology. To implement the initiative, an Office of the Special Envoy for Climate Change was established within the State Department in 2009. At USAID, GCCI activities were coordinated through the Environment and Science Policy Office, which was in 2012 renamed the Office for Global Climate Change.

Legislation

Several bills supporting aspects of the Obama climate change policy and programs were introduced in the 111th Congress, early in the Obama Administration. Most notably, then-Senator John Kerry introduced the International Climate Change Investment Act of 2009 (S. 2835) in December 2009, which would have established an interagency board on climate change to assess, monitor, evaluate, and report on the progress and contributions of departments and agencies in supporting funding for international climate change activities and the goals and objectives of the UNFCCC. The bill also would have required the USAID Administrator to establish a program to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, and the Secretary of State to develop a climate adaptation and global security program, among other things. No action was taken on the legislation or on other legislation that was introduced to support GCCI-related activities in a comprehensive way. However, relevant authority for GCCI programs exists in the Foreign Assistance Act sections on development assistance and the economic support fund, including Section 118 on tropical forests and Section 296(H) with regard to resilience to famine.

Funding

Congress does not designate an annual funding level for the GCCI, though appropriators have made specific allocations in some years for REDD+ and other forestry initiatives, understood as the "sustainable landscapes" pillar of GCCI. The Administration typically uses funds from the Development Assistance and other bilateral appropriations accounts that are authorized to support environmental protection activities, among other things. In addition, there are designated Treasury Department accounts for many of the multilateral environmental trust funds, and a portion of annual Millennium Challenge Corporation funding is also counted by the Administration toward the GCCI. Aside from appropriated funds, development finance provided through OPIC and export credits provided through the Export-Import Bank are counted as GCCI resources in recent reporting as well.

Total appropriated funding for GCCI, when adjusted for inflation, peaked in FY2011, before falling 34% in FY2012 and rising again FY2015. (Figure 6) Funding for clean energy programs, which has been the highest funded component of the initiative every year, ticked upward again in FY2015, bringing total GCCI funding up 17% between FY2014 and FY2015, but still well below the early years of the initiative, in real terms.

U.S. contributions to the multilateral components of GCCI are commonly (but not entirely) requested and appropriated as distinct line items, allowing for a comparison of requested and appropriated funds. Comparing requested funds with actual funding for those funds for which data are available (e.g., the Climate Investment Funds), the trend shows the Administration aiming high in its initial years, Congress providing far less than requested, and the President eventually scaling down requests for multilateral GCCI funding to a level in line with congressional support in the second half of his Administration.19

In the FY2016 budget request, the Administration attempted to ramp up multilateral climate change funding in a new form, requesting $500 million (split between State and Treasury accounts) for a new Green Climate Fund (GCF), to which the Administration pledged $3 billion in November 2014. The fund was intended to be the primary financing mechanism of the UNFCCC, succeeding contributions made to the two multilateral Climate Investment Funds (to which the United States completed a four-year, $2 billion pledge with FY2016 funding). The FY2016 appropriation did not include a specific allocation for a Green Climate Fund, but the accompanying report noted that other funds in the act, or enacted in prior foreign operations appropriations, could be used for this purpose with proper congressional notification.20 The Administration made a $500 million contribution that year, using the Economic Support Fund account, to the consternation of some Members of Congress. Funding for the GCF remains a contentious issue in Congress. In its FY2017 budget request the Administration proposed $750 million for the GCF and no funding for the CIFs, as the U.S. commitment to the CIFs had been met and the GCF was supplanting them. Congress has yet to finalize appropriations for FY2017 (a long-term continuing resolution is funding most programs at the FY2016 level), but the House SFOPS committee-approved bill (H.R. 5912) included a provision prohibiting the use of funds for a contribution to the GCF, while the Senate committee-approved bill (S. 3117) allowed for a GCF contribution up to $500 million.

Results

Unlike the Global Health Initiative and Feed the Future, the GCCI did not establish specific numeric goals and metrics by which to measure progress. However, a 2016 State Department Overview of the GCCI lists many examples of the type of support provided through the initiative, though many are not quantified and some report projected impacts rather than results achieved. USAID has also published some results from its GCCI activities in a recent USAID Climate Action Review, 2010-2016. Select results of the initiative, as reported in these State Department and USAID documents, are detailed in Table 3.

|

GCCI Pillar |

Select Results |

|

Adaptation |

|

|

Clean Energy & Sustainable Landscapes |

|

|

Clean Energy |

|

|

Sustainable Landscapes |

|

Source: Compiled by CRS from Overview of the Global Climate Change Initiative: U.S. Climate Change Finance 2010-2015; USAID Climate Action Review, 2010-2016.

In addition to the external results reporting, USAID reports that the GCCI has impacted how the agency approached development. USAID reports that climate change was incorporated into 62% of USAID country and regional strategies between 2011 and 2015, and beginning in 2015 USAID began to assess and address climate risks and consider climate change mitigation opportunities in all new country strategies. Even among activities that received no designated climate change funding, USAID reported that 18.5% integrated climate change elements, compared with 8% in 2009. USAID asserts than more than $1 billion in USAID funding, beyond designated GCCI funding, has contributed to climate change objectives.21

Some consider the conclusion of the 2015 Paris Agreement, through which 195 nations agreed to reduce the effects of climate change by maintaining global temperatures "well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels," a success attributable in part to the GCCI.22 GCCI bilateral funds have been commonly used to assist partner countries in developing the plans and capacities necessary to support the greenhouse gas abatement commitments that are key to the Agreement. Critics, however, assert that by choosing to make U.S. global policy on climate change almost exclusively through executive action, without seeking the approval and involvement of Congress, the Obama Administration has made any progress in this area vulnerable to dismantlement in a new Administration.23

Conclusion

The Obama Administration's global development initiatives sustained Bush Administration efforts on global health and climate change, and brought new attention to food security and agricultural development. The full potential of these initiatives was perhaps blunted to varying degrees by budget pressures, agency coordination issues, partner country issues, and, in the case of climate change, lack of congressional support. The lasting legacy of the Obama Administration on global development, some say, may be more about the "how" than the "what" of development.24 The principles emphasized in the PPD—elevation of development, partnership and accountability, innovation, evaluation, local procurement, data driven development policy, and interagency cooperation—may be the Obama Administration's unique global development legacy, more than choice of development sector priorities. The "why" aspect of the initiatives, which the PPD clearly frames in terms of promoting U.S. national security, could be reexamined by the new Administration and the 115th Congress together with the "what" and the "how" aspects. Nevertheless, sustained congressional interest in global health and food security, and the coordinated global efforts around climate change, may keep these issues prominent in global development policy discussions beyond the end of the Obama Administration.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

See https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2010/09/22/fact-sheet-us-global-development-policy. |

| 2. |

This report focuses only on the initial Obama Administration foreign aid initiatives and does not discuss Power Africa, which was announced in 2013, in President Obama's second term. For more on that initiative, see CRS Report R43593, Powering Africa: Challenges of and U.S. Aid for Electrification in Africa, by Nicolas Cook et al. |

| 3. |

See President Obama and His Development Legacy, by John Norris, at https://www.devex.com/news/president-obama-and-his-development-legacy-87853. |

| 4. |

For more on foreign aid evaluation, see CRS Report R42827, Does Foreign Aid Work? Efforts to Evaluate U.S. Foreign Assistance, by Marian L. Lawson. |

| 5. |

See the White House factsheet on GHI accompanying the rollout of the PPD at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/Global_Health_Fact_Sheet.pdf. |

| 6. |

See Leading through Civilian Power: The First Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, Appendix 2, available at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/153142.pdf. |

| 7. |

See http://www.pri.org/stories/2012-07-03/obama-administration-closes-global-health-initiative-office. The blog the article refers to is no longer accessible on the GHI website, but a screenshot of the message about the office closing is available at http://sciencespeaksblog.org/2012/07/09/ghi-watchers-wonder-as-next-steps-and-move-forward-include-closing-office/nextsteps/. |

| 8. |

See, for example, http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/07/10/development-community-upset-over-future-of-global-health-initiative/. |

| 9. |

See for example http://www.cgdev.org/blog/failure-launch-post-mortem-ghi-10. |

| 10. |

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that from June 2007 to June 2008, FAO's food price index increased by 44%, with wheat and rice prices increasing by 90% and maize prices by 35%, prompting global discussions about improving food security. |

| 11. |

For current information on focus countries, see https://www.feedthefuture.gov/countries. |

| 12. |

For more information on the legislation, see CRS In Focus IF10475, Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195), by Sonya Hammons. |

| 13. |

Timing of the funding authorization corresponds with the expiration of the Farm Bill, which authorizes U.S. commodity food aid programs. While such programs are not currently considered part of Feed the Future, this simultaneous expiration may offer Congress opportunities to coordinate funding, oversight, and programmatic goals between the programs. For more on food aid, see CRS Report R41072, U.S. International Food Aid Programs: Background and Issues, by Randy Schnepf. |

| 14. |

The strategy is available at https://feedthefuture.gov/sites/default/files/resource/files/USG_Global_Food_Security_Strategy_FY2017-21_0.pdf. The Obama Administration delegated authority for development of the strategy to USAID: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/09/30/presidential-memorandum-delegation-authority-pursuant-sections-5-6a-and. |

| 15. |

Other SFOPS funding, for nutrition activities under Global Health Programs and contributions to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, for example, may also contribute to Feed the Future goals but are not always identified as such in Administration budget requests. P.L. 480 Food for Progress, funded through the agriculture appropriation, is counted in Feed the Future progress reports but not the Feed the Future budget request. |

| 16. |

The report is available at https://feedthefuture.gov/sites/default/files/resource/files/2016%20Feed%20the%20Future%20Progress%20Report_0.pdf. |

| 17. |

See Assessing the US Feed the Future Initiative: A New Approach to Feed Security? by Kimberly Elliott and Casey Dunning, Center for Global Development Policy Paper 075, March 2016, available at http://www.cgdev.org/publication/assessing-us-feed-future-initiative-new-approach-food-security. |

| 18. |

Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/Climate_Fact_Sheet.pdf. |

| 19. |

The Administration had originally pledged $2 million for the CIFs between FY2009 and FY2012. The pledge was fulfilled, but not until FY2016. |

| 20. |

S.Rept. 114-79, p. 99. |

| 21. |

USAID Climate Action Review, p. 32. |

| 22. |

For more on the Paris Agreement, see CRS Insight IN10413, Climate Change Paris Agreement Opens for Signature, by Jane A. Leggett. |

| 23. |

See, for example, Obama's Fragile Climate Legacy by Sarah Wheaton, Politico, at http://www.politico.com/story/2015/12/climate-change-obama-paris-216716. |

| 24. |

See remarks of USAID Administrator Gayle Smith at the Center for Global Development, 12/07/16; President Obama and His Development Legacy, by John Norris, at https://www.devex.com/news/president-obama-and-his-development-legacy-87853; Anne-Marie Slaughter discussing the Obama development legacy at https://www.devex.com/news/what-is-obama-s-development-legacy-85296. |