Transatlantic Relations: U.S. Interests and Key Issues

Changes from May 31, 2019 to April 27, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- A Relationship in Flux?

- Long-Standing U.S. and Congressional Engagement

- The Trump Administration and Heightened Tensions

- A Challenging Political Context and Shifting Policy Priorities

- The Transatlantic Partnership and U.S. Interests

- NATO

- The European Union

- Tensions in the Alliance and Ongoing Challenges

- The European Union

- Evolution of U.S.-EU Relations

- The EU and the Trump Administration

- A More Independent EU?

- Possible Implications of Brexit

KeySelected Foreign Policy and Security Challenges- Russia

- Arms Control and the INF Treaty

- China

- Iran

- Syria

- Afghanistan

- Counterterrorism

- Climate Change

- EU Defense Initiatives

- Climate Policies

- COVID-19

- Trade and Economic Issues

- Current Trade and Investment

TiesRelations

- Trade Disputes

Proposed NewU.S.-EU Trade Negotiations- Implications for the United States

U.S. Policy Considerations andTrump Administration Views- Potential Damage?

Future Prospects- Issues for Congress

Summary

For the past 70 years, the United States has been instrumental in leading and promoting a strong U.S.-European partnership. Often termed the transatlantic relationship, this partnership has been grounded in the U.S.-led post-World War II order based on alliances with like-minded democratic countries and a shared U.S.-European commitment to free markets and an open international trading system. Transatlantic relations encompass the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU), close U.S. bilateral ties with most countries in Western and Central Europe, and a massive, interdependent trade and investment partnership. Despite periodic U.S.-European tensions, successive U.S. Administrations and many Members of Congress have supported the broad transatlantic relationship, viewing it as enhancing U.S. security and stability and magnifying U.S. global influence and financial clout.

Transatlantic Relations and the Trump Administration

The transatlantic relationship currently faces significant challenges. President Trump and some members of his Administration have questioned theNATO's strategic value and utility of NATO to the United States, and they have expressed considerable skepticism about the fundamental worth of the EU and the multilateral trading system. President Trump repeatedly has voicedvoices concern that the United States bears an undue share of the transatlantic security burden and that EU trade policies are unfair to U.S. workers and businesses. The United Kingdom's departure from the EU ("Brexit") on January 31, 2020, could have implications for U.S. security and economic interests in Europe. U.S.-European U.S.-European policy divisions have emerged on a wide range of regional and global issues, from certain aspects of relations with Russia and China, to policies on Iran, Syria, arms control, and climate change, among others. The United Kingdom's pending departure from the EU ("Brexit") also could have implications for U.S. security and economic interests in Europe. Managing the spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has further strained relations.

The Trump Administration asserts that its policies toward Europe seek to bolster the transatlantic relationship by ensuringensure that European allies and friendspartners are equipped to work with the United States in confronting the challenges posed by an increasingly competitive world. AdministrationU.S. officials maintain that the U.S. commitment to NATO and European security remains steadfast; President Trump the Trump Administration has backed new NATO initiatives to deter Russian aggression, supported the accession of two new members to the alliance, and increased U.S. troop deployments in Europe. The Administration also contends that it is committed to working with the EU to resolve trade and tariff disputes, as signaled by its intention to launch newpursue a U.S.-EU trade negotiationsliberalization agreement. Supporters credit President Trump's approach toward Europe with strengthening NATO and compelling the EU to address U.S. trade concerns.

Critics argue that the Administration's policies are endangering decades of U.S.-European consultation and cooperation that have advanced key U.S. geostrategic and economic interests. Some analysts suggest that current U.S.-European divisions are detrimental to transatlantic cohesion and represent a win for potential adversaries such as Russia and China. Many European leaders worry about potential U.S. global disengagement, and some increasingly argue that Europe must be better prepared to address both regional and international challenges on its own.

Congressional Interests

The implications of Trump Administration policies toward Europe and the extent to which the transatlantic relationship contributes to promoting U.S. security and prosperity may be of interest to the 116th Congress. Broad bipartisan support exists in Congress for NATO, and many Members of Congress view the EU as an important U.S. partner, especially given extensive U.S.-EU trade and investment ties. At the same time, some Members have long advocated for greater European burdensharing in NATO, or may oppose European or EU policies on certain foreign policy or trade issues. Areas for potential congressional oversight include the future U.S. role in NATO, as well as prospects for U.S.-European cooperation on common challenges such as managing a resurgent Russia and an increasingly competitive China. Based on its constitutional role over tariffs and foreign commerce, Congress has a direct interest in monitoring proposed new U.S.-EU trade agreement negotiations. In addition, Congress may consider how the Administration's trade and tariff policies could affect the U.S.-EU economic relationship. Also see CRS Report R45652, Assessing NATO's Value, by Paul Belkin; CRS Report R44249, The European Union: Ongoing Challenges and Future Prospects, by Kristin Archick; and CRS In Focus IF11209, Proposed IF10930, U.S.-EU Trade and Investment Ties: Magnitude and Scope, by Shayerah Ilias AkhtarU.S.-EU Trade Agreement Negotiations, by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar, Andres B. Schwarzenberg, and Renée Johnson.

A Relationship in Flux?

Long-Standing U.S. and Congressional Engagement

Since the end of the Second World War, successive U.S. Administrations and many Members of Congress have supported a close U.S. partnership with Europe. Often termed the transatlantic relationship, this partnership encompasses the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), of which the United States is a founding member, and extensive political and economic ties with the European Union (EU) and most countries in Western and Central Europe. The United States has been instrumental in building and leading the transatlantic relationship, viewing it as a key pillar of U.S. national security and economic policy for the past 70 years.

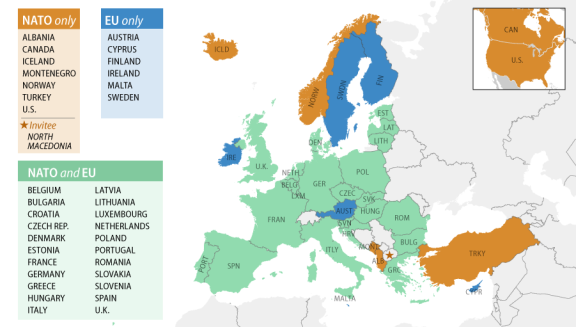

The United States spearheaded the formation of NATO in 1949 to foster transatlantic security and collective defense in Europe. Since the early1950s, U.S. policymakers also supported the European integration project that would evolve into the modern-day EU as a way to promote political reconciliation (especially between France and Germany), encourage economic recovery, and entrench democratic systems and free markets. During the Cold War, U.S. officials regarded both NATO and the European integration project as central to deterring the Soviet threat. After the Cold War, U.S. support was crucial to NATO and EU enlargement. Today, European membership in the two organizations largely overlaps; 2221 countries currently belong to both (see Figure 1). The United States and Europe also have cooperated in establishing and sustaining an open, rules-based international trading system that underpins the global economic order and contributes to U.S. and European wealth and prosperity.

Congress has been actively engaged in oversight of U.S. policy toward Europe and has played a key role in shaping the transatlantic partnership. After the end of the Cold War, many Members of Congress encouraged NATO's evolution—arguing that to remain relevant, NATO must be prepared to confront security threats outside of alliance territory—and were strong advocates for both NATO and EU enlargement to the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The U.S. and European economies are deeply intertwined through trade and investment linkages that support jobs on both sides of the Atlantic. Many Members of Congress thus have a keen interest in monitoring efforts to deepen transatlantic economic ties, such as through potential further trade liberalization, regulatory cooperation, and addressing trade frictions. At the same time, various Members have expressed concern for years about European allies' military dependence on the United States and some Members may oppose European policies on certain foreign policy or economic issues.

The Trump Administration and Heightened Tensions

Over the decades, U.S-European relations have experienced numerous ups and downs and have been tested by periods of political tension, various trade disputes, and changes in the security landscape. However, no U.S. president has questioned the fundamental tenets of the transatlantic security and economic architecture to the same extent as President Trump. Many European policymakers and analysts are critical of President Trump's reported transactional view of the NATO alliance, what some view as his singular focus on European defense spending as the measure of the alliance's worth, and his seeming hostility toward the EU, whose trade practices he has argued are unfair and detrimental to U.S. economic interests. Many in Europe also are concerned by what they view as protectionist U.S. trade policies, including the imposition of steel and aluminum tariffs and potential auto tariffs.

Under the Trump Administration, U.S.-European policy divisions have emerged on a range of other issues as well, including arms control and nonproliferation, China, Iran, Syria, from aspects of relations with Russia and China to policies on Iran, Syria, and the Middle East peace process, climate change, and the role of international organizations such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Source: Created by CRS.The Trump Administration contends that its policies toward Europe seek to shore up and preserve a strong transatlantic partnership to better address common challenges in what it views as an increasingly competitive world.. Many European officials are dismayed by the U.S. decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement to combat climate change. Tensions also have arisen over EU plans to improve defense capabilities and U.S.-EU strategies for resolving the long-standing dispute in the Western Balkans between Serbia and Kosovo. In addition, U.S.-European differences exist on the role of multilateral organizations such as the United Nations (U.N.) and the World Trade Organization (WTO).

U.S. officials contend that Trump Administration policies toward Europe seek to shore up and preserve a strong transatlantic partnership to better address common challenges in an increasingly competitive world. At the February 2020 Munich Security Conference in Germany, U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo stated, "the death of the transatlantic alliance is grossly over-exaggerated."1 The Administration asserts that it is committed to NATO and its collective defense clause (Article 5), has backed NATO efforts to deter Russia, and is seeking to address barriers to trade with the EU through proposed new trade negotiations. Supporters argue that President Trump's forceful approach has led to increased European defense spending and greater European willingness to address inequities in U.S-European trade relations.

Nevertheless, U.S.-European relations face significant strain. European policymakers continue to struggle with what they view as a lack of consistency in U.S. policies, especially given conflicting Administration statements about NATO and the EU. Some in Europe appear increasingly anxious about whether the United States will remain a credible and reliable partner.

A Challenging Political Context and Shifting Policy Priorities

European concerns about potential shifts in U.S. foreign, security, and trade policies come amid a range of other difficult issues confronting Europe.12 These include the United Kingdom's pending(UK's) departure from the EU (known as "Brexit"), at the end of January 2020; increased support for populist, anti-establishmentantiestablishment political parties,; rule of -of-law concerns in several countries (including Poland, Hungary, and Romania), sluggish growth and persistently high unemployment in key European economies (such as France, Italy, and Spain),; negative economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic amid already sluggish EU-wide growth; ongoing pressures related to migration,; a continued terrorism threat,; a resurgent Russia,; and a competitive China. The EU in particular is struggling with questions about its future shape and role on the world stage. In light of Europe's various internal preoccupations, some in the United States harbor concerns about the ability of European allies in NATO, or the EU as a whole, to serve as robust and effective partners for the United States in managing common international and regional challenges.

Meanwhile, the United States faces deep divisions on numerous political, social, and economic issues, as well as anti-establishmentantiestablishment sentiments and concerns about globalization and immigration among some segments of the U.S. public. A number ofSome analysts suggest that President Trump's "America First" foreign policy signals a U.S. shift away from international cooperation and indicates a U.S. shift toward a more isolationist United States. Experts point out that until the 20th century, U.S. foreign policy was based largely on the imperative of staying out of foreign entanglements. Some contend that "the trend toward an America First approach has been growing since the end of the Cold War" and that the post-World War II "bipartisan consensus "about America's role as upholder of global security has collapsed" among both Democrats and Republicans.2 Such possible shifts."3

In his remarks at the February 2020 Munich Security Conference, Secretary of State Pompeo asserted that the United States has not abandoned its global leadership role. However, European officials and commentators noted his emphasis on the importance of "sovereignty," which they interpreted as signaling a decreased U.S. interest in international cooperation and consultation, especially through multilateral institutions.4 Such possible trends could have lasting implications for transatlantic relations and the post-World War II U.S.-led global order.3

In addition, both the United States and Europe face generational and demographic changes. For younger Americans and Europeans, World War II and the Cold War are far in the past. Some observers posit that younger policymakers and publics may not share the same conviction as previous generations about the need for a close and stable transatlantic relationship.

The Transatlantic Partnership and U.S. Interests4

6

Despite periodic difficulties over the years in the transatlantic relationship, U.S. and European policymakers alike have valued a close transatlantic partnership as serving their respective geostrategic and economic interests. U.S. policymakersofficials, including past presidents and many Members of Congress, have articulated a range of benefits to the United States of strong U.S.-European ties, including the following:

- U.S. leadership of NATO and U.S. support for the European integration project have been crucial to maintaining peace and stability

on the European continentin Europe and stymieing big-power competition that cost over 500,000 American lives in two world wars.57

- NATO and the EU are cornerstones of the broader U.S.-led international order created in the aftermath of World War II. U.S. engagement in Europe has helped to foster democratic and prosperous European allies and friends that frequently support U.S. foreign and economic policy preferences and bolster the credibility of U.S. global leadership, including in multilateral institutions such as the

United NationsU.N. and the WTO. - U.S. engagement in Europe helps limit Russian, Chinese, or other potentially malign influences in the region.

- The two sides of the Atlantic face a range of common international challenges—from countering terrorism and cybercrime to managing instability in the Middle East—and share similar values and policy outlooks. Neither side can adequately address such diverse global concerns alone, and the United States and Europe have a demonstrated track record of cooperation.

- U.S. and European policymakers have developed trust and well-honed habits of political, military, and intelligence cooperation over decades. These dynamics are unique in international relations and cannot be easily or quickly replicated elsewhere (particularly with countries that do not share the same U.S. commitment to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law).

- The United States and Europe share a substantial and mutually beneficial economic relationship that is highly integrated and interdependent. This economic relationship

substantiallycontributes to economic growth and employment on both sides of the Atlantic. TheEU accounts for about one-fifth of U.S. total trade in goods and services, and the United States and the EU are each other's largest source and destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). The transatlantic economy generates overUnited States and the EU are each other's largest trade and investment partners. The transatlantic economy (including the EU and non-EU countries such as the UK, Norway, and Switzerland) typically generates overs $5 trillion per year in foreign affiliate sales and directly employsaboutover 9 million workers on both sides of the Atlantic (and possibly up to 16 million people when indirect employment is included). Together, theThe United States and Europe have created and maintained the current rules-based international trading system that has contributed to U.S. (and European) wealth and prosperity.TheIn 2018, the combined U.S. and EU economiesaccount for 46%accounted for nearly half of global gross domestic product (GDP) and over half of globalFDI. Together, this providesforeign direct investment (FDI). Together, the United States and Europewiththus possess significant economic clout that has enabled the two sides of the Atlantic to take the lead in setting global rules and standards.

At times, U.S. officials and analysts have expressed frustration with certain aspects of the transatlantic relationship. Previous U.S. administrations and many Members of Congress have criticized what they viewed as insufficient European defense spending and have questioned the costs of the U.S. military presence in Europe (especially after the Cold War). U.S. policymakers have long-standing concerns about some EU regulatory barriers to trade. In addition, observers point out that the EU lacks a single voice on many foreign policy issues, which may complicate or prevent U.S.-EU cooperation. Some in the United States have argued that maintaining a close U.S.-European partnership necessitates compromise and may slow U.S. decisionmaking.

Meanwhile, some European officials periodically complain about U.S. dominance of the relationship and a frequent U.S. expectation of automatic European support, especially in international or multilateral forums. Those with this view contend that although the United States has long urged Europe to "do more" in addressing challenges both within and outside of Europe, the United States often fails to grant European allies in NATO, or the EU as an institution, an equal say in transatlantic policymaking. In the past, some European leaders—particularly in France—have aspired to build up the EU as a global power in part to check U.S. influence. Most European governments, however, have not supported developing the EU as a counterweight to the United States. Regardless of these occasional U.S. and European irritations with each other, the transatlantic partnership has remained grounded broadly in the premise that its benefits outweigh the negatives for both sides of the Atlantic.

NATO6

8

The United States was the driving proponent of NATO's creation in 1949 and has been the alliance's undisputed leader as it has evolved from a regionally focused collective defense organization of 12 members to a globally engaged security organization of Trump Administration officials stress that U.S. policy toward NATO continues to be driven by a steadfast commitment to European security and stability. The Administration's 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy articulate that the United States remains committed to NATO's foundational Article 5 collective defense clause. (President Trump also has proclaimed his support for Article 5.) U.S. strategy documents underscore that the Administration continues to view NATO as crucial to deterring Russia. The Administration has requested significant increases in funding for U.S. military deployments in Europe under the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). The United States currently leads a battalion of about 1,100 NATO troops deployed to Poland and deploys a U.S. Army Brigade Combat Team of about 3,300 troops on continuous rotation in NATO's eastern member states.2930 members. Successive U.S. Administrations have viewed U.S. leadership of NATO as a cornerstone of U.S. national security strategy, bringing benefits ranging from peace and stability in Europe to the political and military support of 28. President Trump's apparent skepticism of the value and utility of NATO, however, has generated significant unease and tensions within the alliance. Many European policymakers and outside analysts contend that President Trump's rhetoric and a perceived U.S. unilateral approach to certain common challenges—in Syria, for example—are prompting questions about U.S. leadership of NATO and potentially causing lasting damage to alliance cohesion and credibility.

European allies also stress that the first and only time NATO invoked Article 5 was in solidarity with the United States after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Subsequently, Canada and the European allies joined the United States to lead military operations in Afghanistan, the longest and most expansive operation in NATO's history. In 2015, following the end of its 11-year-long combat mission in Afghanistan, NATO launched the Resolute Support Mission (RSM) to train, advise, and assist Afghan security forces. Between 2015 and late 2018, NATO allies and partners steadily matched U.S. increases in troop levels to RSM. Many in Europe and Canada view their contributions in Afghanistan as a testament to the value they can provide in achieving shared security objectives. As of April 2020, almost one-third of the fatalities suffered by coalition forces in Afghanistan have been from NATO members and partner countries other than the United States.9 In 2011, the high point of the NATO mission in Afghanistan, about 40,000 of the 130,000 troops deployed to the mission were from non-U.S. NATO countries and partners.10For almost as long as NATO has been in existence, it has faced criticism. One long-standing concern of U.S. critics, including President Trump and some Members of Congress, is that the comparatively low levels of defense spending by some European allies and their reliance on U.S. security guarantees have fostered an imbalanced "burdensharing"burdensharing arrangement by which the United States carries an outsize share of the responsibility for European security. President Trump has repeatedly expressed these sentiments in suggesting that NATO is a "bad deal" for the United States. Although successive U.S. Administrations have U.S. leaders have long called for increased allied defense spending, none are seen to have done so as stridently as President Trump or to link these calls so openly to the U.S. commitment to NATO and a broader questioning of the alliance's value and utility (see text box below).7 (see text box).11

Administration supporters, including some Members of Congress, argue that President Trump's forceful statements have succeeded in securing defense spending increases across the alliance that were not forthcoming under his predecessors.

Trump Administration officials stress that U.S. policy toward NATO continues to be driven by a steadfast commitment to European security and stability. The Administration's 2017 National Security Strategy and 2018 National Defense Strategy articulate that the United States remains committed to NATO's foundational Article 5 collective defense clause. (President Trump has proclaimed his support for Article 5 as well.) U.S. strategy documents also underscore that the Administration continues to view NATO as crucial to deterring Russia. The Administration has requested significant increases in funding for U.S. military deployments in Europe under the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). The United States currently leads a battalion of about 1,100 NATO troops deployed to Poland and deploys a U.S. Army Brigade Combat Team of about 3,300 troops on continuous rotation in NATO's eastern member states NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has credited President Trump with playing a key role in spurring increases in European allied defense spending.12 Critics of the Trump Administration's NATO policy maintain that renewed Russian aggression has been a major factor behind rising European defense budgets.

|

NATO Defense Spending At their 2014 Wales Summit, NATO members agreed to increase defense spending so that by 2024 their national defense budgets would equal at least 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) and at least 20% of national defense expenditure would be devoted to procurement and research and development. The 2% and 20% spending targets are intended to guide national defense spending by NATO members; they do not refer to contributions made directly to NATO, nor would all defense spending increases necessarily be devoted solely to meet NATO goals. U.S. and NATO officials say they are encouraged by a steady rise in defense spending since the Wales Summit. Whereas three allies met the 2% guideline in 2014, NATO estimates that Although all allied governments agreed to the Wales commitments, many emphasize that contributions to ongoing NATO missions and the effectiveness of military capabilities should be deemed as important as total defense spending levels. They note that an ally spending less than 2% of GDP on defense could have more modern, effective military capabilities than an ally that meets the 2% target but allocates most of that funding to personnel costs and relatively little to ongoing missions and modernization. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg also has frequently emphasized a broader approach to measuring contributions to the alliance, using a metric of "cash, capabilities, and contributions." Others add that such a broader assessment would be more appropriate given NATO's wide-ranging strategic objectives, some of which may require capabilities beyond the military sphere. Source: For NATO defense spending data, see NATO, Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries |

Many officials and analysts on both sides of the Atlantic assert that President Trump's vocal criticism of NATO and what they regard as an increasing lack of transatlantic coordination have undermined the alliance.14 In a widely reported November 2019 interview, French President Emmanuel Macron cited such divergences when he proclaimed that, "we are currently experiencing the brain death of NATO." Referring to concerns about the drawdown of U.S. forces from Syria in October 2019 and subsequent military operations by Turkey, he lamented, "You have partners together in the same part of the world, and you have no coordination whatsoever of strategic decision-making between the United States and its NATO allies."15 NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg maintains that disagreement among allies is not a new phenomenon and stresses that "Europe and North America are doing more together in NATO today than we have for decades."16 As part of NATO efforts to strengthen deterrence and defense, member states have deployed a total of 4,500 troops to the three Baltic States and Poland and NATO has increased military exercises and training activities in Central and Eastern Europe. At NATO's December 2019 Leaders' Meeting, the allies highlighted progress in responding to cyber and hybrid threats and formally declared space as a new operational domain for NATO. In February 2020, NATO defense ministers agreed to expand NATO's training mission in Iraq. Despite some initial concerns that allied governments were not being consulted on U.S. force drawdown plans in Afghanistan, NATO leaders welcomed the February 29, 2020, agreements between the United States and the Taliban and the U.S. and Afghanistan governments. These agreements call for the withdrawal of U.S. and international forces within 14 months, based on certain political and security conditions being met. Secretary General Stoltenberg asserted that NATO would implement adjustments, including troop reductions, to its Afghanistan mission in accordance with the agreements and in coordination with the United States.17Despite stated U.S. policyTensions in the Alliance and Ongoing Challenges

Despite stated Trump Administration support for NATO, some European allies express unease about President Trump's commitment to NATO, especially amid reports that the President has considered withdrawing the United States from the alliance.813 European allies object to the President' European allies refute past statements by President Trump that NATO is obsolete and take issue with the President's claims that European countries have takentake advantage of the United States by not spending enough on their own defense. SinceThey stress that since the end of the Cold War, NATO allies and partner countries have contributed to a range of NATO-led military operations across the globe, including in the Western Balkans, Eastern Europe, Afghanistan, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Middle East.

the Middle East, and Eastern Europe.

European allies also stress that the first and only time NATO invoked Article 5 was in solidarity with the United States after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Subsequently, Canada and the European allies joined the United States to lead military operations in Afghanistan, the longest and most expansive operation in NATO's history. Many in Europe and Canada view their contributions in Afghanistan as an unparalleled demonstration of solidarity with the United States and a testament to the value they can provide in achieving shared security objectives. As of early 2019, almost one-third of the fatalities suffered by coalition forces in Afghanistan have been from NATO members and partner countries other than the United States.9 In 2011, the high point of the NATO mission in Afghanistan, about 40,000 of the 130,000 troops deployed to the mission were from non-U.S. NATO countries and partners.10

NATO also continues to face a number of political and military challenges. Key among these is managing a resurgent Russia. Allied discussions over NATO's strategic posture have exposed divergent views over the threat posed by Russia (see "Key Foreign Policy and Security Challenges" for more information). Differences also . Allied discussions over NATO's strategic posture have exposed divergent views over the threat posed by Russia. Many allies have criticized fellow NATO member Turkey for its military operations in Syria and its acquisition of a Russian-made air defense system. Differences exist among the allies over the appropriate role for NATO in addressing the wide-ranging security challenges emanating from the Middle East and North Africa. NATO continues to grapple with significant disparities in allied military capabilities, especially between the United States and the other allies, as well as from a rising China.

In addition, significant disparities in allied military capabilities persist. In most, if not all, NATO military interventions, European allies and Canada have depended on the United States to provide key capabilities such as air- and sea-lift,; refueling,; and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). In addition, a number of European policymakers and outside analysts contend that President Trump's negative rhetoric about NATO is damaging alliance cohesion and raising questions about future U.S. leadership of the alliance (see "U.S. Policy Considerations and Future Prospects" below).

The European Union11

. Some European policymakers argue that improving European military capabilities requires greater EU defense integration, but others in Europe and many U.S. officials worry that such efforts could weaken NATO and decouple U.S. and European security (see "Selected Foreign Policy and Security Challenges" for more information).

The European Union18

Evolution of U.S.-EU Relations

Since May 1950—when President Harry Truman first offered U.S. support for the European Coal and Steel Community, regarded as the initial step on the decades-long path toward building the EU—the United States has championed the European integration project.1219 Supporters of the EU integration project contend that it largely succeeded in fulfilling core U.S. post-World War II-goals in Europe of promoting peace and prosperity and deterring the Soviet Union. After the Cold War, the United States strongly backed EU enlargement to the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, viewing it as essential to extending stability, democracy, and the rule of law throughout the region, preventing a strategic vacuum, and firmly entrenching these countries in Euro-Atlantic institutions and the U.S.-led liberal international order. The United States and many Members of Congress traditionally have supported the EU membership aspirations of Turkey and the Western Balkan states for similar reasons.

Over the past 25 years, as the EU has expanded and evolved, U.S.-EU political and economic relations have deepened. Despite some acute differences (including the 2003 war in Iraq), the United States has looked to the EU for partnership on foreign policy and security concerns worldwide. Although EU decisionmaking is sometimes slower than many U.S. policymakers would prefer and agreement among EU member states proves elusive at times, U.S. officials generally have regarded cooperation with the EU—where possible—as serving to bolster U.S. positions and enhance the prospects of achieving U.S. objectives. The United States and the EU have promoted peace and stability in various regions and countries (including the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Africa), jointly imposed sanctions on Russia for its aggression in Ukraine, enhanced law enforcement and counterterrorism cooperation, worked together to contain Iran's nuclear ambitions, and sought to tackle cross-border challenges such as cybersecurity and climate changecybercrime. Historically, U.S.-EU cooperation has been a driving force behind efforts to liberalize world trade and ensure the stability of international financial markets.

The EU and the Trump Administration

In light of long-standing U.S. support for the EU, many EU officials have been surprised by what they regard as President Trump's largely negative opinion of the bloc and key member states such as Germany. President Trump has supported the UK's decision to leave the EU and has expressed doubts about the EU's future viability. President Trump has called the EU a "foe" for "what they do to us in trade," although he also has noted, "that doesn't mean they are bad … it means that they are competitive."13 At the same time, the20 The EU is concerned by the Trump Administration's trade policies, especially the imposition of steel and aluminum tariffs and ongoing threats of potential auto tariffs. Many in the EU question whetherAlthough the Administration has engaged with the EU in efforts to reform the WTO, many EU policymakers remain anxious about the degree to which the United States will continue to be a reliable partner for the EU in setting global trade rules and standards and sustaining the multilateral trading system. (See "Trade and Economic Issues" for more information.)

Some commentators suggest that the Trump Administration largely views the EU through an economic prism and is less inclined to regard the EU as an important political and security partner. Various observersThey speculate that unlike past Administrations, the Trump Administration might be indifferent to the EU's collapse if it allowed the United States to negotiate bilateral trade deals with individual member states that it believes would better serve U.S. interests.1421 President Trump (and some Members of Congress) have expressed keen interest in concluding a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United KingdomUK following its expectedJanuary 2020 withdrawal from the EU (see "Possible Implications of Brexit").

ManySeveral analysts suggest that President Trump's critical viewscriticism of the EU areis shaped by a preference for working bilaterally with nation-states rather than in international or multilateral forums. In a December 2018 speech in Brussels, Belgium, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo asserted that "the European Union and its predecessors have delivered a great deal of prosperity to the entire continent" and that "we [the United States] benefit enormously from your success," but he also criticized multilateralism and asked, "Is the EU ensuring that the interests of countries and their citizens are placed before those of bureaucrats here in Brussels?".1522 Secretary Pompeo's comments were widely interpreted as an implicit rebuke of the EU. Others point out that the Trump Administration is not the first U.S. Administration to be skeptical of multilateral institutions or to be charged withseen as preferring unilateral action. This was a key European criticism of the George W. Bush Administration as well.

In addition, manyMany in the EU also are uneasy with elements of the Trump Administration's "America First" foreign policy. Several Administration decisions have put the United States into direct conflict with the EU and experts suggest they could endanger U.S.-EU political cooperationare directly at odds with EU views and policies. These include, in particular, the Trump Administration'sU.S. decisions to withdraw from the 2015 multilateral nuclear deal with Iran and the Paris Agreement on climate change (see "Key Foreign Policy and Security Challenges" for more information). EU officials also view. EU officials argue that the Administration's recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital as undermining prospects for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

At the same time, Administration officials contendundermines prospects for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a long-standing EU goal. U.S.-EU tensions have flared with respect to the ongoing conflict in Syria, a rising China, and combatting the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, the Trump Administration contends that certain EU policies are damaging relations with the United States. Among other issues, such officialssome U.S. policymakers express frustration with the EU's refusal to discuss agricultural products in planned U.S.-EU trade negotiations, and they argue that that the EU does not sufficiently understand the extent of the threat posed by Iran.16 Some U.S. policymakers voice concern that renewed EU defense initiatives could compete with NATO. In 2017, 25 EU members launched a new EU defense pact (known as Permanent Structured Cooperation, or PESCO) aimed at enhancing European military capabilities and bolstering the EU's Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP). Previous U.S. Administrations have been anxious about CSDP's potential implications for NATO. The EU has bristled at the Trump Administration's criticisms, however, given its strident calls for greater European defense spending and burdensharing in NATO, as well as Administration suggestions that PESCO could become a "protectionist vehicle for the EU" that impedes U.S.-European defense industrial cooperation and U.S. defense sales to Europe.17

U.S. officials note that there have always been disagreements between the United States and the EU, and they argue that fears of a demise in relations are largely overblown. At the same time, some U.S. policymakers and analysts suggest that the multiple challenges currently facing the EU could have negative implications for the EU's ability to be a robust, effective U.S. partner. Those with this view note that internal preoccupations (ranging from Brexit to migration to voter disenchantment with traditionally pro-EU establishment parties) could prevent the EU from focusing on key U.S. priorities, such as Russian aggression in Ukraine, a more assertive China, instability in the Middle East and North Africa, the ongoing conflict in Syria, and the continued terrorism threat. Others point out that despite the string of recent EU crises over the past few years, the EU has survived and the bloc has continued to work with the United States on numerous regional and international issues.

Possible Implications of Brexit18

Many European leaders increasingly call for the EU to play a more assertive and independent role on the world stage (often referred to by the EU as strategic autonomy). Although forging a more coherent and robust EU foreign policy is a long-standing EU goal, boosting the EU's ability to act more independently also is receiving new attention, in part because of concerns about the future trajectory of the EU's partnership with the United States. In June 2019, EU leaders approved a new Strategic Agenda for 2019-2024, which asserted that, "In a world of increasing uncertainty, complexity and change, the EU needs to pursue a strategic course of action and increase its capacity to act autonomously to safeguard its interests, uphold its values and way of life, and help shape the global future."24 Upon assuming office in December 2019, Ursula von der Leyen, the new President of the European Commission (the EU's executive), stated that she would lead a "geopolitical Commission" actively engaged in tackling regional and global challenges with the full range of EU diplomatic and economic tools. The EU also is seeking to be a global leader on issues such as data protection and climate change.25 Experts view French President Macron as a driving force behind revived EU ambitions to be a more independent and autonomous global actor, in line with long-held French policy preferences. Macron champions "European military and technological sovereignty" as crucial to ensuring the EU's position as a global player in a more competitive world in which the EU cannot necessarily depend on U.S. cooperation and support.26 German Chancellor Angela Merkel also backs a more geopolitical and militarily capable EU but tempers this position with continued strong support for NATO and recognition that the transatlantic alliance remains crucial to European security.27 Despite ambitions for a robust EU role in foreign policy and security matters, many analysts point out that EU member states remain divided on policy responses to many challenges and the EU still struggles to speak with one voice on a range of key issues, including Libya, Syria, Turkey, Russia, China, migration, and some aspects of climate change mitigation.28 Some U.S. officials note that there have always been political disagreements and trade disputes between the United States and the EU, and they argue that fears of a demise in relations are largely overblown. With the entrance into office of new leaders at all three main EU institutions in late 2019, U.S. officials sought to "reset" relations and reduce tensions.29 EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell maintains that the United States and the EU continue to share "common values" and the U.S.-EU partnership will endure.30 In a 2016 referendum, UK voters favored leaving the EU by 52% to 48%. Brexit was originally scheduled to occur in March 2019, but the UK Parliament was unable to agree on a way forward due to divisions over what type of Brexit the UK should pursue and challenges related to the future of the border between Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (an EU member state). An early parliamentary election in the UK in December 2019 broke the political deadlock, with a decisive victory for Prime Minister Boris Johnson's Conservative Party leading to the UK's withdrawal as a member of the EU on January 31, 2020.In a 2016 referendum, UK voters favored leaving the EU by 52% to 48%. In March 2017, the UK government officially notified the EU of its intention to withdraw, triggering a two-year period for the UK and the EU to conclude complex withdrawal negotiations. Since the 2016 referendum, the UK has remained divided on what type of Brexit it wants. UK Prime Minister Theresa May's government largely pursued a "hard" Brexit that would keep the UK outside the EU's single market and customs union, thus allowing the UK to negotiate its own trade deals with other countries. Since January 2019, the UK Parliament has rejected the withdrawal agreement negotiated with the EU three times; a key sticking point has been the "backstop" to resolve the Irish border question and protect the Northern Ireland peace process. As the result of a six-month extension offered by EU leaders on April 10 (at an emergency European Council summit), the UK is scheduled to exit the EU by October 31, 2019, at the latest U.S. officials also are dismayed that the EU and most national governments have not issued outright bans on using equipment from Chinese telecommunication companies such as Huawei, despite U.S. security concerns. In addition, the Administration is wary that EU efforts to bolster its Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and pursue greater EU defense integration could compete with NATO and impede U.S.-European defense industrial cooperation. Previous U.S. Administrations have been anxious about CSDP's potential implications for NATO, as well.23 (See "Selected Foreign Policy and Security Challenges" for more information.)

A More Independent EU?

Since deciding to leave the EU, the UK has sought to reinforce its close ties with the United States and to reaffirm its position as a leading country in NATO. The UK is likely to remain a strong U.S. partner, and Brexit is unlikely to cause a dramatic makeover in most aspects of the U.S.-UK relationship. Analysts believe that close U.S.-UK cooperation will continue for the foreseeable future in areas such as counterterrorism, intelligence, economic issues, and the future of NATO, as well as on numerous global and regional security challenges. UK officials have emphasized that Brexit does not entail a turn toward isolationism and that the UK intends to remain a global leader in international diplomacy, security issues, trade and finance, and development aid.

Observers hold differing views as to whether Brexit will ultimately reinvigorate or diminish the UK's global power and influence in foreign policy, security, and economic issues.President Trump has expressed repeated support for Brexit. In October 2018, the Trump Administration notified Congress of its intent to launch U.S.-UK trade negotiations once the UK ceasesceased to be a member of the EU, and many Members of Congress appear receptive to a U.S.-UK FTA in the future.1933 At the same time, some in Congress arehave been concerned that Brexit might negatively affect the Northern Ireland peace process. In London in April 2019, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi asserted that there would be "no chance whatsoever" for a U.S.-UK FTA should Brexit weaken the 1998 peace accord that ended Northern Ireland's 30-year sectarian conflict.20

Beyond the U.S.-UK bilateral relationship, Brexit could have a substantial impact on certain U.S. strategic interests, especially in relation to Europe more broadly and future developments in the EU. The UK iswas the EU's second-largest economy and a key diplomatic and military power within the EU. Moreover, the UK is oftenoften was regarded as the closest U.S. partner in the EU, a partner that commonly sharesshared U.S. views on foreign policy, trade, and regulatory issues. Some observers suggest that the United States is losinghas lost its best advocate within the EU for policies that bolster U.S. goals and protect U.S. interests. Others contend that the United States has close bilateral ties with most EU countries, shares common political and economic preferences with many of them, and as such, the UK's departure will not significantly alter U.S.-EU relations.

Some U.S. officials have conveyed concerns that the UK's withdrawal could make the EU a less capable and less reliable partner for the United States given the UK's diplomatic, military, and economic clout. The UK has served as a key driver of certain EU initiatives, especially EU enlargement (including to Turkey) and efforts to develop stronger EU foreign and defense policies. In addition, as the UK is a leading voice for robust EU sanctions against Russia in response to Russia's annexation of Ukraine's Crimea and aggression in eastern Ukraine, some observers suggest that the departure of the UK could shift the debate in the EU about the duration and severity of EU sanctionsOthers contend that the United States has close bilateral ties with most EU countries, shares common political and economic preferences with many of them, and as such, the UK's departure will not significantly alter U.S.-EU relations.

More broadly, U.S. officials have long urged the EU to move beyond what is often perceived as a predominantly inward focus on treaties and institutions, in order to concentrate more effort and resources toward addressing a wide range of shared external challenges (such as terrorism and instability to Europe's south and east). Some observers note that Brexit has produced another prolonged bout of internal preoccupation within the EU and has consumed a considerable degree of UK and EU time and personnel resources in the process. At the working level, EU officials arethe EU is losing British personnel with significant technical expertise and negotiating prowess on issues such as sanctions or dealing with countries like Russia and Iran.

On the other hand, some analysts have suggested that Brexit could ultimately lead to a more like-minded EU, able to pursue deeper integration without UK opposition (the UK traditionally served as a brake on certain EU integration efforts). For example, Brexit could allow the EU to move ahead more easily with undertaking military integration projects under the EU Common Security and Defense Policy. However, as discussed above, Trump Administration officials express a degree of concern about PESCO, the EU's new defense pactrecent efforts to enhance European military capabilities and CSDP, and some worry that without UK leadership, CSDP and PESCOEU defense initiatives could evolve in ways that may infringe upon NATO's primary role in European security in the longer term.

KeySelected Foreign Policy and Security Challenges

35

The United States and Europe face numerous common foreign policy and security challenges, but they have pursued different policies on several key issues. The Trump Administration maintains that its policy choices display strong U.S. leadership and seek to bolster both U.S. and European security. Administration officials also argue that they remain ready to work with Europe on many of these common challenges.

Russia21

36

U.S.-European cooperation has been viewedregarded as crucial to managing a more assertive Russia and preventing Russia from driving a wedge between the two sides of the Atlantic. The imposition of sanctions on Russia in response to its aggression in Ukraine is cited as a key example of a policy that has benefited from U.S.-EU coordination given the EU's more extensive economic ties with Russia. The EU has welcomed congressional efforts since the start of the Trump Administration to maintain U.S. sanctions on Russia, despite concerns that certain provisions in the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act (CRIEEA) of 2017 (P.L. 115-44, Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA], Title II) could negatively affect EU business and energy interests.

Although some Europeans remain wary about President Trump's expressed interest in improving U.S.-Russian relations, U.S. and European policies toward Russia remain broadly aligned. As noted above, the Trump Administration has endorsed new NATO initiatives to deter Russian aggression and increased the U.S. military footprint in Europe. The United States has continuedAlthough some Europeans were wary initially about President Trump's expressed interest in improving U.S.-Russian relations, many U.S. and European policies toward Russia remain broadly aligned. As noted above, the Trump Administration has endorsed new NATO initiatives to deter Russian aggression and increased the U.S. military footprint in Europe.

The imposition of sanctions on Russia following its 2014 invasion of Ukraine is cited as a key example of a policy that has benefited from U.S.-EU coordination given the EU's more extensive economic ties with Russia. Both the United States and the EU continue to support and impose sanctions on Russia for its actions in Ukraine and for other malign activities (including Russia's March 2018 chemical weapons attack in the United KingdomUK on former Russian intelligence officer and UK citizen Sergei Skripal and his daughter). The United States and many European countries share similar concerns about Russian cyber activities and influence operations and have sought to work together in various forums to share best practices on countermeasures.

At the same time, some policymakers and analysts express concern about the effectiveness and sustainability of NATO efforts to deter Russia and the use of sanctions as a long-term policy option. Some allies, including Poland and the Baltic States, have urged a more robust allied military presence in Central and Eastern Europe and strongly support maintaining pressure on Russia through sanctions. Others, including leaders in Germany and Italy, have stressed the importance of a dual-track approach to Russia that complements deterrence with dialogue.

A key U.S.-European friction point is the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project that would increase the amount of Russian gas delivered to Germany and other parts of Europe via the Baltic Sea. The Trump Administration and many Members of Congress object to Nord Stream 2 because they believe it will increase European energy dependence on Russia and undercut Ukraine (the pipeline would bypass the country, thereby denying Ukraine transit fees and possibly loosening constraints on Russian policy toward Ukraine). Many in the EU share these concerns, including Poland and other Central European countries, as well as the European Commission (the EU's executive body). Germany, Austria, and other supporters view Nord Stream 2 primarily as a commercial project and argue that it will help increase the supply of gas to Europe.22

Arms Control and the INF Treaty23

Most European NATO allies, as well as the EU, have long regarded the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty as a key pillar of the European security architecture. On February 1, 2019, the Trump Administration announced it was suspending U.S. participation in the INF Treaty and would withdraw the United States in six months (in accordance with the terms of the treaty). European leaders largely agree with the U.S. assessment that Russia is violating the INF Treaty, and NATO leaders have announced that they "fully support" the U.S. decision.24

At the same time, differences in perspective exist among European countries. Some European officials and analysts question the effectiveness and sustainability of NATO efforts to deter Russia and the use of sanctions as a long-term policy option. Several European policymakers, including leaders in Germany and Italy, have stressed the importance of a dual-track approach to Russia that complements deterrence with dialogue. In light of what he views as a continued deadlock with Russia, French President Macron has criticized Western sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 as "inefficient" and has called for restarting a "strategic dialogue" to resolve differences with Russia.37 Other allies, including Poland and the Baltic States, urge a more robust NATO military presence in Central and Eastern Europe and strongly support maintaining pressure on Russia through sanctions. Some U.S.-European tensions have arisen recently over new U.S. sanctions on Russia that EU and other European officials regard as more unilateral in nature, prompting concerns about the continued coordination of U.S.-EU sanctions. In particular, many European policymakers express opposition to U.S. secondary sanctions that could negatively affect European firms. These include sanctions aimed at curbing Russian energy export pipelines such as Nord Stream 2, which some European companies are engaged in financing and constructing. The Trump Administration and many Members of Congress object to Nord Stream 2 because they believe that it will give Russia greater political and economic leverage over countries that depend on Russian gas and increase Ukraine's vulnerability to Russian aggression. Some EU officials, Poland, and the Baltic States, among others, share U.S. concerns. Supporters of Nord Stream 2, including the German and Austrian governments, assert that the pipeline will enhance EU energy security by increasing the capacity of a direct and secure supply route at a time of rising European demand for gas. In December 2019, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Protecting Europe's Energy Security Act (PEESA) as part of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92, Title LXXV). PEESA aims to stop the construction of Nord Stream 2 by establishing sanctions on foreign persons and entities involved in laying the pipeline. Some European opponents of Nord Stream 2, including the European Commission, joined supporters of the pipeline in criticizing U.S. sanctions established by PEESA. EU officials noted that the EU rejects as a "matter of principle" the imposition of sanctions against EU companies conducting legitimate business in line with EU and European law.38 Other opponents of Nord Stream 2, such as the Polish government, support PEESA as a necessary mechanism to prevent completion of the project.39 Most European NATO allies, as well as the EU, have long regarded the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty as a key pillar of the European security architecture. In February 2019, the Trump Administration announced it was suspending U.S. participation in the INF Treaty due to Russian violations and subsequently withdrew the United States in August 2019, in accordance with the terms of the treaty. At the February 2020 Munich Security Conference in Germany, U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo asserted that the United States had restored "credibility" to arms control by withdrawing from the INF Treaty.41 European leaders largely agree with the U.S. assessment that Russia was violating the INF Treaty, and NATO leaders announced that they "fully support" the U.S. withdrawal.42 At the same time, European officials remain concerned that the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty could spark a new arms race and harm European security. Following the U.S. decision, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia also would suspend participation in the INF Treaty. Moreover, Putin indicated that Russia would begin work on developing new nuclear-capable missiles in light of the treaty's collapse.43 Many European officials appear troubled that the United States has not presented a clear way forward on arms control following its withdrawal from the INF Treaty. Some worry that should the United States seek to field U.S. missiles in Europe in the future, this could create divisions within NATO and be detrimental to alliance cohesion. They add that tensions linked to the U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty could negatively affect possible efforts to renew the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (known as New START) with Russia, which is set to expire in 2021. French President Macron has urged renewal of the New START Treaty, as have some Members of Congress. Russian President Putin also has expressed interest in renewing the treaty. The Trump Administration has not yet decided whether it will support extending the treaty.44At the same time, European officials remain deeply concerned that the U.S. suspension and expected withdrawal from the INF Treaty could spark a new arms race and harm European security. Subsequent to the U.S. decision, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that Russia also would suspend participation in the INF Treaty. Moreover, Putin indicated that Russia would begin work on developing new nuclear-capable missiles in light of the treaty's collapse. Many European officials appear troubled by the U.S. decision because they contend that the United States has not presented a clear way forward. Some worry that should the United States seek to field U.S. missiles in Europe in the future, this could create divisions within NATO and be detrimental to alliance cohesion. They add that tensions linked to the planned Many in the EU welcomed efforts by Congress in 2017 to ensure the Trump Administration maintained U.S. sanctions on Russia, despite concerns that certain provisions in the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-44, Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, Title II) could negatively affect EU business and energy interests.

U.S. withdrawal from the INF Treaty could negatively affect possible efforts to renew the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (known as New START) with Russia, which is set to expire in 2021.25

China26

As expressed in the December 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy, U.S. officials have grown increasingly concerned that "China is gaining a strategic foothold in Europe by expanding its unfair trade practices and investing in key industries, sensitive technologies, and infrastructure."27 Chinese investment in the EU reportedly has increased from approximately $700 million annually prior to 2008 to $30 billion in 2017. Such investment spans sectors including energy, transport, communications, media, insurance, financial services, and industrial technology.28

The Trump Administration and many Members of Congress have been alarmed in particular by some European governments' interest in contracting withthe potential involvement of Chinese telecommunications company Huawei to buildin building out at least parts of theirEuropean fifth generation (or 5G) wireless networks. U.S. officials have warned European allies and partners that using Huawei or other Chinese 5G equipment could impede intelligence- sharing with the United States due to fears of compromised network security. Although some allies, such as the UK and Germany, have said they would not prevent Chinese companies from bidding on 5G contracts, they have stressed that they would not contract with any companies that do not meet their stringent national security requirements.29

In addition to concerns about intellectual property theft and illicit data collection or spying, some analysts worry that Chinese economic influence could translate into leverage over European countries. Such leverage could push some European governments to align their foreign policy positions with those of China or otherwise validate policies of the Chinese government, and possibly prevent the EU from speaking with one voice on China. Some experts suggest that smaller51

Smaller EU countries, as well as less prosperous non-EU Balkan countries, aremay be relatively vulnerable to this type of leverageeconomic pressure from China, although large EU countries also could be susceptible. As evidence, many noteSome experts express concern in particular about Italy's decision to joincooperate in China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China'sa state-run initiative to deepen Chinese investment and infrastructure links across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe. The Trump Administration reportedly lobbied Italy against joining the BRI.30

Despite U.S. concerns about China's growing footprint in Europe, Administration officials appear hopeful that the United States and Europe can work together to meet the various security and economic issues posed by a rising China. Over the past year, EU members France and Germany have backed efforts by the European Commission to develop more stringent requirements to regulate Chinese investment in Europe.Since early 2019, analysts note a more assertive European approach to China.54 In a March 2019 joint position paper on China, the European Commission and the EU's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy characterized China in part as an "economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance."31

In a February 2019 interview, U.S. Ambassador to the EU Gordon Sondland called on the United States and the EU to "combine our mutual energies … to meet China and check China in multiple respects: economically, from an intelligence standpoint, militarily."3255 In April 2019, predominantly as a result of mounting concern over China, the EU adopted a new regulation that set out a framework for increased screening of foreign investments (many EU member states have national FDI screening programs).56 Some analysts, however, are skeptical about the extent to which U.S.-European cooperation toward China is possible. Those with this view note the disparities in U.S. and European security interests vis-à-vis China and apparent U.S. inclinations to view China as an economic rival to a greater extent than many European governments.33

Iran34

With tensions between the United States and China increasing over the COVID-19 pandemic, analysts have observed China undertaking a campaign of "facemask diplomacy" in offering medical supplies and support to some European countries. At the same time, experts also assert that attempts by China to control the COVID-19 narrative through disinformation could backfire and result in increasingly strained relations with Europe.58 Many European governments and the EU have been alarmed by rising tensions between the United States and Iran, which they fear could lead to military confrontation. European concerns intensified further in the aftermath of the January 2, 2020, U.S. strike in Iraq that killed Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani, head of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps-Qods Force. News reports suggest that European allies were not given advance warning of the U.S. strike, and many European governments expressed concern that the U.S. decision could put European troops in the region at risk. European countries are significant contributors to the NATO training and advisory mission in Iraq and to the U.S.-led coalition combating the Islamic State terrorist organization (also known as ISIS or ISIL) in Iraq and Syria. (In March 2020, several European countries announced the temporary withdrawal of troops from these missions after the suspension of activities to reduce the spread of COVID-19.)60 On January 6, 2020, French President Macron, German Chancellor Merkel, and UK Prime Minister Johnson (leaders of the so-called E3, the three European countries that helped negotiate the 2015 multilateral nuclear deal with Iran, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA) released a joint statement condemning recent attacks on coalition forces in Iraq by Iranian-backed militias and the "negative role" that Iran has played in the region, including through forces under the command of General Soleimani. The three leaders urged all parties to de-escalate. The joint statement also called on Iran to "reverse all measures inconsistent with the JCPOA," expressed concern about security and stability in Iraq, and emphasized the importance of continuing to combat the Islamic State.61 In a subsequent statement following a meeting of NATO countries, NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg reiterated many of these points, similarly expressing concern about Iran's destabilizing behavior and calling for de-escalation.62Many European governments and the EU are alarmed by rising tensions between the United States and Iran, which they fear could lead to military confrontation. 57

(the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). The EU remains committed to the JCPOA and has sought to work with Iran and other signatories to prevent its collapse. The EU worked closely with the Obama Administration to negotiate the JCPOA and considers it to be a major foreign policy achievement that has prevented Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Many analysts assert that the EU's adoption of strict sanctions againston Iran between 2010 and 2012, including a full embargo on oil purchases, brought U.S. and European approaches on Iran into alignment. They credit this combined U.S.-EU economic pressure as key to forcing Iran into the negotiations that produced the JCPOA.

The Trump Administration contends that the JCPOA has only served to embolden Iran and has urged the EU to join the United States in abandoning the JCPOA and reimposing sanctions on Iran. The EU shares other U.S. concerns about Iran, including those related to Iran's ongoing ballistic missile program and support for terrorism, but the EU asserts that such issues should be addressed separately from the JCPOA. The EU also contends that the U.S. decision to unilaterally withdraw from the JCPOA could destabilize the region and worries that the reimposition of U.S. sanctions on Iran could threaten EU business interests.

The EU remains committed to the JCPOA and has sought to work with Iran and other signatories to prevent its collapse. In January 2019, France, Germany, and the UK launched the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX), a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) designed to enable trade in humanitarian items (including food, medicine, and medical devices) that are generally exempt from sanctions (although INSTEX might eventually provide a platform to trade with Iran in oil and other products). Some in the EU, however, fear that Iran's commitment to the JCPOA may be weakening amid Iran's announcement in early May 2019 that it would no longer abide by JCPOA restrictions on stockpiles of low-enriched uranium and heavy water. The EU continues to urge Iran not to withdraw from the JCPOA completely.

Syria35

Many European governments were alarmed by President Trump's announcement in December 2018 that the United States would withdraw its entire 2,000-strong force in Syria fighting the Islamic State terrorist organization (also known as ISIS or ISIL). Most European countries have supported the U.S.-led international coalition to defeat the Islamic State since 2014. Although President Trump's decision to withdraw U.S. forces was based on his view that the Islamic State was largely defeated, the United States reportedly did not consult with its European partners on its military plans. The apparent lack of consultations has raised concerns about a breakdown in U.S.-European cooperation and potential negative consequences for transatlantic cohesion.

News reports suggest that U.S. officials urged the UK and France to keep their ground forces in Syria following the expected U.S. departure and called for European countries to deploy an "observer" force to patrol a "safe zone" on the Syrian side of the border with Turkey. The UK and France reportedly declined these requests, and other European governments did not appear eager to assume the risks of a Syria operation in the absence of U.S. forces. The United States has since announced that it will keep a residual force of around 400 troops in Syria in an apparent effort to encourage a continued European presence, but it remains uncertain whether European governments will agree to this approach.36

Afghanistan37

In December 2018, news outlets reported that the Trump Administration was considering substantially reducing the U.S. troop presence in Afghanistan. European allies, who have served with the United States and NATO in Afghanistan since 2001, reacted to these reports with surprise and concern. Although the Administration has begun negotiations with the Taliban on ending the conflict in Afghanistan, U.S. officials denied a possible drawdown in U.S. forces. European officials asserted that any future reduction in U.S. troops in Afghanistan must be carried out in close coordination with the allies.

Some experts have questioned the viability of NATO's Afghanistan mission without continued U.S. participation at current levels. Subsequent press reports indicate that the U.S. Defense Department has begun discussions with European allies on future military plans for Afghanistan.38 European military involvement in Afghanistan has faced relatively consistent public opposition in many European countries. As such, observers suggest that allies could be receptive to winding down NATO's mission in Afghanistan in tandem with the United States. At the same time, some European officials reportedly object to being left out of peace talks with the Taliban, given allied military contributions as well as considerable European development assistance to Afghanistan.39

Counterterrorism40

Since 2001, the United States has enhanced counterterrorism and homeland security cooperation with European governments and the EU. The United States and the EU have concluded several agreements in this area, including accords to improve shipping container security, share airline passenger data, and track terrorist financing. U.S. and European officials alike regard such cooperation as crucial to fighting terrorism on both sides of the Atlantic. In recent years, the United States and Europe have focused on combating the Islamic State and the foreign fighter phenomenon. Like its predecessors, the Trump Administration appears to value such cooperation.

Recently, some European governments and the EU have bristled at President Trump's call for European countries to repatriate European fighters and sympathizers captured by U.S.-backed forces in Syria and Iraq or risk their release as the United States prepares to withdraw its forces from Syria. Many European governments have been grappling with how to deal with returning Islamic State fighters and their families, but some are hesitant to assume the associated security risks of bringing such citizens home. Amid broader tensions, some analysts worry about fissures developing between the United States and Europe on counterterrorism strategies and tactics.41

Climate Change42

The EU reacted with dismay to President Trump's announcement in June 2017 that the United States would withdraw from the 2015 multilateral Paris Agreement aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combating climate change (the U.S. withdrawal is due to take effect in November 2020). The EU had worked closely with the former Obama Administration to negotiate the 2015 accord. In announcing his decision, President Trump asserted that the Paris Agreement disadvantages U.S. businesses and workers, but he also indicated that he would be open to negotiating a "better" deal.43 The EU rejects any renegotiation of the Paris Agreement, and EU officials have vowed to work with U.S. business leaders and state governments that remain committed to implementing the accord's provisions.

Analysts suggest that the Trump Administration's decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement has spurred the EU to assume even greater stewardship of the accord. In February 2018, the EU asserted that it would not conclude FTAs with countries that do not ratify the Paris Agreement, creating another potential friction point in U.S.-EU trade discussions. The EU continues to voice support for other international partners—especially developing countries—in meeting their commitments to the Paris Agreement and has intensified cooperation with China in particular.44 At the same time, observers point out that some EU countries are facing challenges in meeting their existing targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and efforts to formalize more ambitious EU emissions reduction goals have encountered a degree of resistance within the EU.45

Trade and Economic Issues46

Current Trade and Investment Ties

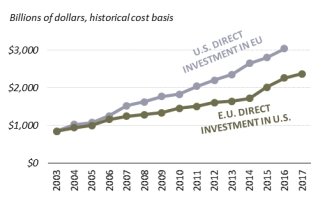

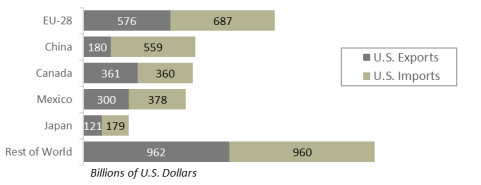

The United States and the EU are each other's largest trade and investment partners. Total U.S.-EU trade in merchandise and services reached $1.3 trillion in 2018 (Figure 2). Investment ties, including affiliate presence and intra-company trade, are even more significant given their size and interdependent nature. In 2017, the stock of transatlantic foreign direct investment (FDI) totaled over $5 trillion (Figure 3); the EU accounts for over half of both FDI in the United States and U.S. direct investment abroad.

While the transatlantic economy is highly integrated, it still faces tariffs and nontariff barriers to trade and investment. U.S. and EU tariffs are low on average, though tariffs are high on some sensitive products. Regulatory differences and other nontariff barriers also may raise the costs of U.S.-EU trade and investment. Over the years, the United States and the EU have sought to further liberalize trade ties, enhance regulatory cooperation, and work together on international economic issues of joint interest and concern, for instance, regarding China's trading practices.