U.S.-EU Trade Agreement Negotiations: Trade in Food and Agricultural Products

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) officially notified the Congress of the Trump Administration’s plans to enter into formal trade negotiations with the European Union (EU) in October 2018. In January 2019, USTR announced its negotiating objectives for a U.S.-EU trade agreement, which included agricultural policies—both market access and non-tariff measures. However, the EU’s negotiating mandate, released in April 2019, stated that the trade talks would exclude agricultural products.

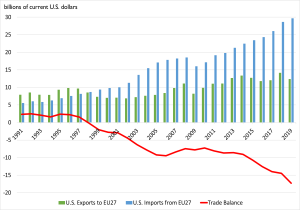

U.S.-EU27 Agricultural Trade, 1990-2019/

Source: CRS from USDA data for “Total Agricultural and Related Products (BICO-HS6). EU27 excludes UK.

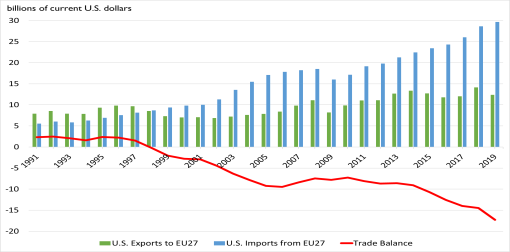

Improving market access remains important to U.S. agricultural exporters, especially given the sizable and growing U.S. trade deficit with the EU in agricultural products (see figure). Some market access challenges stem in part from commercial and cultural practices that are often enshrined in EU laws and regulations and vary from those of the United States. For food and agricultural products, such differences are focused within certain non-tariff barriers to agricultural trade involving Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBTs), as well as Geographical Indications (GIs).

SPS and TBT measures refer broadly to laws, regulations, standards, and procedures that governments employ as “necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health” from the risks associated with the spread of pests and diseases, or from additives, toxins, or contaminants in food, beverages, or feedstuffs. SPS and TBT barriers have been central to some longstanding U.S.-EU trade disputes, including those involving EU prohibitions on hormones in meat production and pathogen reduction treatments in poultry processing, and EU restrictions on the use of biotechnology in agricultural production. As these types of practices are commonplace in the United States, this tends to restrict U.S. agricultural exports to the EU.

GI protections refer to naming schemes that govern product labeling within the EU and within some countries that have a formal trade agreement with the EU. These protections tend to restrict U.S. exports to the EU and to other countries where such protections have been put in place.

Plans for U.S.-EU trade negotiations come amid heightened U.S.-EU trade frictions. In March 2018, President Trump announced tariffs on steel and aluminum imports on most U.S. trading partners after a Section 232 investigation determined that these imports threaten U.S. national security. Effective June 2018, the EU began applying retaliatory tariffs of 25% on imports of selected U.S. agricultural and non-agricultural products. In October 2019, the United States imposed additional tariffs on imports of selected EU agricultural and non-agricultural products, as authorized by World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement procedures in response to the longstanding Boeing-Airbus subsidy dispute.

Public statements by U.S. and EU officials in January 2020, however, signaled that the U.S.-EU trade talks might include SPS and regulatory barriers to agricultural trade. Statements by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials cited in the press call for certain SPS issues as well as GIs to be addressed in the trade talks. However, other press reports of statements by EU officials have downplayed the extent that specific non-tariff barriers would be part of the talks. More formal discussions are expected in the spring of 2020.

Previous trade talks with the EU, as part of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) negotiations during the Obama Administration, stalled in 2016 after 15 rounds. During those negotiations, certain regulatory and administrative differences between the United States and the EU on issues of food safety, public health, and product naming schemes for some types of food and agricultural products were areas of contention.

U.S.-EU Trade Agreement Negotiations: Trade in Food and Agricultural Products

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Trade Data and Statistics

- U.S.-EU Tariff Retaliation

- Selected U.S.-EU Agricultural Trade Issues

- Market Access

- Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade

- SPS/TBT Issues

- Geographical Indications

- Next Steps

Figures

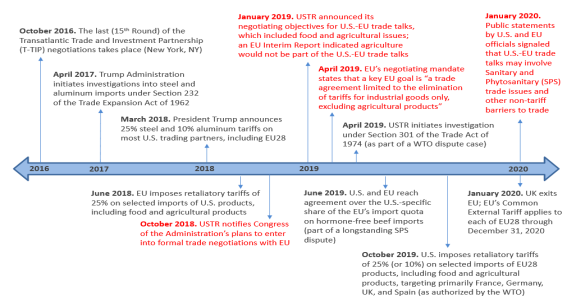

- Figure 1. Selected Timeline of Events Related to U.S.-EU Agricultural Trade

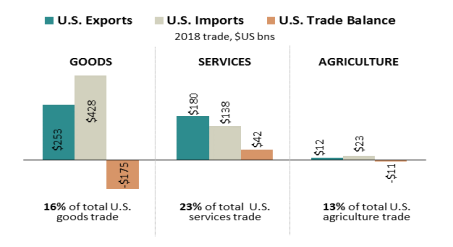

- Figure 2. U.S.-EU27 Trade in 2018

- Figure 3. U.S.-EU27 Trade, 1991-2019

- Figure 4. U.S.-UK Trade, 1991-2019

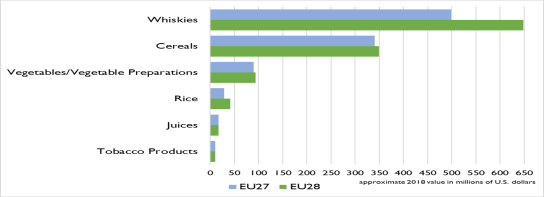

- Figure 5. Selected U.S. Exports to EU28 Subject to Retaliation for Section 232 Tariffs

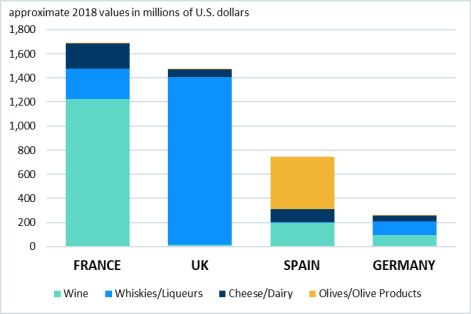

- Figure 6. Selected U.S. Imports from EU28 Member States Affected by Section 301 Tariffs

Summary

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) officially notified the Congress of the Trump Administration's plans to enter into formal trade negotiations with the European Union (EU) in October 2018. In January 2019, USTR announced its negotiating objectives for a U.S.-EU trade agreement, which included agricultural policies—both market access and non-tariff measures. However, the EU's negotiating mandate, released in April 2019, stated that the trade talks would exclude agricultural products.

U.S.-EU27 Agricultural Trade, 1990-2019

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA data for "Total Agricultural and Related Products (BICO-HS6). EU27 excludes UK. |

Improving market access remains important to U.S. agricultural exporters, especially given the sizable and growing U.S. trade deficit with the EU in agricultural products (see figure). Some market access challenges stem in part from commercial and cultural practices that are often enshrined in EU laws and regulations and vary from those of the United States. For food and agricultural products, such differences are focused within certain non-tariff barriers to agricultural trade involving Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBTs), as well as Geographical Indications (GIs).

SPS and TBT measures refer broadly to laws, regulations, standards, and procedures that governments employ as "necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health" from the risks associated with the spread of pests and diseases, or from additives, toxins, or contaminants in food, beverages, or feedstuffs. SPS and TBT barriers have been central to some longstanding U.S.-EU trade disputes, including those involving EU prohibitions on hormones in meat production and pathogen reduction treatments in poultry processing, and EU restrictions on the use of biotechnology in agricultural production. As these types of practices are commonplace in the United States, this tends to restrict U.S. agricultural exports to the EU.

GI protections refer to naming schemes that govern product labeling within the EU and within some countries that have a formal trade agreement with the EU. These protections tend to restrict U.S. exports to the EU and to other countries where such protections have been put in place.

Plans for U.S.-EU trade negotiations come amid heightened U.S.-EU trade frictions. In March 2018, President Trump announced tariffs on steel and aluminum imports on most U.S. trading partners after a Section 232 investigation determined that these imports threaten U.S. national security. Effective June 2018, the EU began applying retaliatory tariffs of 25% on imports of selected U.S. agricultural and non-agricultural products. In October 2019, the United States imposed additional tariffs on imports of selected EU agricultural and non-agricultural products, as authorized by World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement procedures in response to the longstanding Boeing-Airbus subsidy dispute.

Public statements by U.S. and EU officials in January 2020, however, signaled that the U.S.-EU trade talks might include SPS and regulatory barriers to agricultural trade. Statements by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) officials cited in the press call for certain SPS issues as well as GIs to be addressed in the trade talks. However, other press reports of statements by EU officials have downplayed the extent that specific non-tariff barriers would be part of the talks. More formal discussions are expected in the spring of 2020.

Previous trade talks with the EU, as part of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) negotiations during the Obama Administration, stalled in 2016 after 15 rounds. During those negotiations, certain regulatory and administrative differences between the United States and the EU on issues of food safety, public health, and product naming schemes for some types of food and agricultural products were areas of contention.

In October 2018, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) officially notified the Congress, under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), of the Trump Administration's plans to enter into formal trade negotiations with the European Union (EU).1 This action followed a July 2018 U.S.-EU Joint Statement by President Trump and then-European Commission (EC) President Juncker announcing that they would work toward a trade agreement to reduce tariffs and other trade barriers, address unfair trading practices, and increase U.S. exports of soybeans and certain other products.2 Previously, in 2016, U.S.-EU negotiations as part of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) stalled after 15 rounds under the Obama Administration.3

The outlook for new U.S.-EU talks remains uncertain. There continues to be disagreement about the scope of the negotiations, particularly the EU's intent to exclude agriculture from the talks on the basis that it "is a sensitivity for the EU side."4 EU sensitivities stem in part from commercial and cultural practices that are often embodied in EU laws and regulations and vary from those of the United States. For food and agricultural products, such differences include regulatory and administrative differences between the United States and the EU on issues related to food safety and public health—or Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures, and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBTs). Other differences include product naming schemes for some types of food and agricultural products subject to protections involving Geographical Indications (GIs). Addressing food and agricultural issues in the negotiations remains important to U.S. exporters given the sizable and growing U.S. trade deficit with the EU in agricultural products.

Renewed trade talks also come amid heightened U.S.-EU trade frictions. In March 2018, President Trump announced 25% steel and 10% aluminum tariffs on most U.S. trading partners, including the EU, after a Section 232 investigation determined that these imports threaten U.S. national security.5 In response, the EU began applying retaliatory tariffs of 25% on certain U.S. exports to the EU. Additionally, as part of the Boeing-Airbus subsidy dispute, in October 2019 the United States began imposing additional, World Trade Organization (WTO)-sanctioned tariffs on $7.5 billion worth of certain U.S. imports from the EU.

This report provides an overview of U.S.-EU trade in agriculture and background information on selected U.S.-EU agricultural trade issues concerning a potential trade liberalization agreement between the United States and the EU. Following a review of U.S.-EU agricultural trade trends, this report describes recent agricultural trade trends and tariff actions affecting certain U.S.-EU traded food and agricultural goods. It then describes potential issues in U.S.-EU trade agreement negotiations involving food and agricultural trade. Figure 1 shows a timeline of selected events.

Trade Data and Statistics

Following are trade data and statistics for the current 27 EU member states (EU27).6 Unless otherwise noted, these figures exclude the United Kingdom (UK), which formally exited the EU in January 2020.7 Moving forward, U.S. trade negotiations with the EU are expected to exclude the UK, which may enter into trade discussions with the United States separately.8

Trade data presented here are compiled from U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) trade statistics for "Agricultural and Related Products." As defined by USDA, this product grouping includes agricultural products (including bulk and intermediate products and also consumer-oriented products) and agricultural-related products (including fish and shellfish products, distilled spirits, forest products, and ethanol and biodiesel blends). Additional information on the various data sources is discussed in the text box.

The United States and the EU are the world's largest trade and investment partners.9 While food and agricultural trade between the United States and the EU27 accounts for less than 1% of the value of overall trade in total goods and services (Figure 2), the EU27 remains a leading market for U.S. agricultural exports. It accounted for about 8% of the value of all U.S. exports and ranked as the fifth-largest market for U.S. food and farm exports in 2019—after Canada, Mexico, China, and Japan. Data depicted in Figure 2 do not reflect trade in fish and seafood, distilled spirits, and bioenergy products.

|

USDA's definition of "agricultural products" (often referred to as "food and fiber" products)—for the purposes of calculating U.S. agricultural exports, imports, and the agricultural trade balance—covers a broad range of goods from unprocessed bulk commodities, intermediate products, and consumer-oriented products. This includes grains for human consumption and animal feed, raw cotton, meat and poultry products, milk and dairy foods, fresh and processed specialty crops (fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, nursery products, honey, and wine), highly processed high-value foods and beverages (such as sausages, bakery goods, ice cream, beer, and condiments), tropical products (such as sugar, cocoa, and coffee), fats and oils, hides and skins, wool and mohair, and unmanufactured tobacco. Generally, most of the products found in Chapters 01-23 of the U.S. Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) include agricultural products. Exceptions include fishery products (Chapters 03 and 16) and distilled spirits (Chapter 22). Other products are also considered agricultural products. These include essential oils (Chapter 33), raw rubber (Chapter 40), raw animal hides and skins (Chapter 41), and wool and cotton (Chapters 51-52). These data exclude manufactured tobacco products such as cigarettes and cigars (Chapter 24). Some products derived from plants or animals are considered to be nonagricultural because of their manufactured nature, such as cotton thread and yarn, fabrics and textiles, clothing, leather and leather goods, cigarettes and cigars, and distilled spirits. Others are considered to be agricultural-related products, such as fishery and seafood products (given their food value) and solid wood products (given that USDA promotes U.S. exports of these products). USDA's definition of "agricultural related products" includes fish and shellfish products, distilled spirits, forest products, and ethanol and biodiesel blends. Source: USDA, "GATS Agricultural Products Definition," https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/AgriculturalProducts.aspx. See also, for example, USDA, Profiles of Tariffs in Global Agricultural Markets, AER-796, Appendix, January 2001. |

|

|

Source: CRS using trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb database. Data for "Agricultural Products" (as defined by USDA) are from USDA's Global Agricultural Trade System, and do not include distilled spirits, fish and seafood, and other products. Notes: 2018 is the most recent year for which services data are available. EU27 excludes UK. |

During the past two decades, growth in U.S. agricultural exports to the EU has not kept pace with growth in trade to other U.S. markets. U.S. agricultural imports from the EU27 currently exceed U.S. exports to the EU27. In 2019, U.S. exports of agricultural and related products to the EU27 totaled $12.4 billion, while U.S. imports of agricultural and related products from the EU27 totaled $29.7 billion, resulting in a U.S. trade deficit of approximately $17.3 billion. This reverses the U.S. agricultural trade surpluses with the EU27 during the early 1990s (Figure 3). Leading U.S. agricultural exports to the EU27 were corn and soybeans, tree nuts, distilled spirits, fish products, wine and beer, planting seeds, and processed foods. Leading U.S. imports from the EU27 were wine and spirits, beer, drinking waters, olive oil, cheese, and processed foods.

While data shown in the graphic reflect total trade in "Agricultural and Related Products," including agricultural products, fish and shellfish products, distilled spirits, and other agricultural related products, the trade picture may vary by product category (as shown in Table 1). Trade data presented here do not include the UK, which is a major importer of U.S. agricultural products. In 2019, U.S. agricultural and related product exports to the UK totaled $2.8 billion, which roughly equaled the value of imports from the UK (Figure 4).

|

Exports (EU27) |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2015 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

(billions of current U.S. dollars) |

||||||

|

Total Agricultural and Related Products |

7.9 |

7.0 |

9.9 |

12.7 |

14.1 |

12.4 |

|

Agricultural Products |

6.7 |

5.5 |

7.6 |

10.4 |

11.7 |

10.2 |

|

Consumer Oriented Products |

1.2 |

1.7 |

3.2 |

4.9 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

|

Intermediate Products |

1.9 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

|

Bulk Agricultural Products |

3.6 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

4.3 |

2.8 |

|

Agricultural Related Product |

1.3 |

1.5 |

2.3 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

|

Fish Products |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

|

Distilled Spirits |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

|

Other Products |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Imports (EU27) |

||||||

|

Total Agricultural and Related Products |

5.7 |

9.8 |

17.1 |

23.4 |

28.6 |

29.7 |

|

Agricultural Products |

4.8 |

7.6 |

13.4 |

18.5 |

21.9 |

22.5 |

|

Consumer Oriented Products |

3.7 |

6.0 |

8.8 |

11.9 |

14.2 |

14.8 |

|

Intermediate Products |

0.9 |

1.4 |

4.4 |

6.1 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

|

Bulk Agricultural Products |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Agricultural Related Product |

0.9 |

2.2 |

3.7 |

4.9 |

6.8 |

7.1 |

|

Fish Products |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Distilled Spirits |

0.5 |

1.2 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

|

Other Products |

0.2 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

|

Net Trade (EU27) |

||||||

|

Total Agricultural and Related Products |

2.3 |

-2.8 |

-7.2 |

-10.7 |

-14.5 |

-17.3 |

|

Agricultural Products |

1.9 |

-2.1 |

-5.8 |

-8.1 |

-10.1 |

-12.4 |

|

Consumer Oriented Products |

-2.5 |

-4.3 |

-5.6 |

-7.0 |

-9.6 |

-10.0 |

|

Intermediate Products |

1.0 |

0.1 |

-2.2 |

-3.5 |

-4.5 |

-4.8 |

|

Bulk Agricultural Products |

3.4 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.5 |

4.0 |

2.5 |

|

Agricultural Related Product |

0.4 |

-0.6 |

-1.5 |

-2.6 |

-4.4 |

-4.9 |

|

Fish Products |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Distilled Spirits |

-0.5 |

-1.1 |

-2.4 |

-2.9 |

-3.3 |

-4.0 |

|

Other Products |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

-0.2 |

-1.2 |

-1.2 |

Source: CRS from USDA's Global Agricultural Trade System data (BICO-HS6 product group). Data cover EU27 nations (excluding UK). As defined by USDA, "Agricultural and Related Products" include bulk and intermediate agricultural products, consumer-oriented products, and other related agricultural products such as distilled spirits, fish and seafood, forest products and biodiesel blends, and other products.

Notes: Totals may not add due to rounding.

U.S.-EU Tariff Retaliation

The U.S.-EU trade negotiations come amid heightened U.S.-EU trade frictions. In March 2018, President Trump announced 25% steel and 10% aluminum tariffs on most U.S. trading partners after a Section 232 investigation determined that these imports threaten to impair U.S. national security.10 The EU was not among the trading partners with whom the Trump Administration negotiated permanent exemptions from tariffs or alternative quota arrangements, and U.S. tariffs on U.S. imports from the EU went into effect in June 2018. The EU views the U.S. national security justification as groundless and the U.S. tariffs to be inconsistent with WTO rules. The EU has challenged the U.S. actions at the WTO.11

Effective June 2018, the EU began applying retaliatory tariffs of 25% on imports of U.S. whiskies, corn, rice, kidney beans, preserved and mixed vegetables, orange juice, cranberry juice, peanut butter, and tobacco products, along with selected non-agricultural products (Figure 5).12 This action includes the EU27 countries and the UK (EU28), as U.S. exports to the UK remain subject to the additional tariffs.13 The value of U.S. agricultural exports to the EU28 targeted by these additional tariffs is estimated to have been approximately $1.2 billion in 2018, or nearly 9% of total U.S. agricultural exports to the EU28 (excluding nonagricultural products) (Table 2). Some analysts estimate that U.S. agricultural exports subject to tariff retaliation in 2018-2019 experienced a 33% decline in the EU28 market.14

|

EU Imports from the U.S. Targeted by EU's Section 232 Retaliatory Tariffs |

CN* Subheadings |

2018 Value (millions of U.S.$) |

Share of Targeted U.S. Exports (%) |

Additional Tariff as of June 2018 (%) |

||||

|

Whiskies |

4 |

648.7 |

22.5 |

25 |

||||

|

Cereals |

1 |

349.3 |

12.1 |

25 |

||||

|

Vegetables/Vegetable Preparations |

7 |

94.0 |

3.3 |

25 |

||||

|

Rice |

19 |

41.7 |

1.4 |

25 |

||||

|

Juices |

9 |

17.7 |

0.6 |

25 |

||||

|

Tobacco Products |

10 |

10.8 |

0.4 |

25 |

||||

|

All Other |

131 |

1,724.7 |

59.7 |

10 or 25 |

||||

|

Total |

181 |

2,886.9 |

100.0 |

|||||

Source: CRS using trade data from Global Trade Atlas and EU Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/886, Annex I (June 20, 2018).

Notes: EU28 includes UK, which left the EU in 2020. *Combined Nomenclature (CN) is the EU's eight-digit product coding system. Values are approximates. The EU developed two lists of U.S. import products subject to EU retaliatory tariffs. Annex I, which entered into force on June 22, 2018, contains 181 product categories subject to an additional ad valorem tariff rate of 25% and one product category subject to an additional 10%. Annex II (not included in the figures above) contains 158 import product categories from the United States that would be subject to additional ad valorem duties of 10%, 25%, 35%, and 50%. Annex II is expected to apply on June 1, 2021 "or upon the adoption by, or notification to, the WTO Dispute Settlement Body of a ruling that the United States' safeguard measures are inconsistent with the relevant provisions of the WTO Agreement." EU retaliatory actions to date have been notified to the WTO pursuant to the Agreement on Safeguards.

In October 2019, U.S.-EU trade tensions escalated further when the United States imposed additional tariffs on $7.5 billion worth of certain U.S. imports from the EU, or about 1.5% of all U.S. imports from the EU28 in 2018 (including the UK and nonagricultural products).15 This action, authorized by WTO dispute settlement procedures, followed a USTR investigation initiated in April 2019 under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.16 The USTR determined that the EU had denied U.S. rights under WTO agreements.17 Specifically, USTR concluded that the EU and certain member states (including the UK) had not complied with a WTO Dispute Settlement Body ruling recommending the withdrawal of WTO-inconsistent EU subsidies to Airbus for the manufacture of large civil aircraft.18

The list of products subject to additional tariffs stemming from the Airbus subsidy dispute targets mainly the EU member states responsible for the illegal subsidies. It includes agricultural products such as spirits and wine, cheese and dairy products, meat products, fish and seafood, fresh and prepared fruit products, coffee, and bakery goods. Agricultural imports account for about 56% of the total value of EU28 products subject to these additional tariffs.19 As of February 2020, tariff increases are limited to 25% on agricultural products, and they target primarily France, Germany, UK, and Spain (Figure 6). By agricultural product category, whiskies, liqueurs, and wine (mainly from UK and France) account for approximately 38%, and other food and agricultural products (mainly from Spain and France) account for 19% (Table 3).20 In December 2019, USTR began a review to determine if the list of imports subject to additional tariffs should be revised or tariff rates increased.21 In February 2020, USTR made some changes to the list of products affected by Section 301 tariffs. In terms of U.S. agricultural imports from the EU, the only change will be the removal of prune juice from the list, which will not be subject to additional 25% tariffs effective March 5, 2020.

U.S.-EU trade negotiations could be affected further if the EU retaliates and imposes tariffs on U.S. exports, in response to either these U.S. actions or an upcoming WTO decision in the parallel EU dispute case against the United States.22 Later this year a WTO arbitrator is expected to authorize the EU to seek remedies in the form of tariffs on U.S. exports to the EU, after the WTO determined in early 2019 that the United States had also failed to abide by WTO subsidies rules in supporting Boeing.

|

U.S. Imports from the EU Targeted by the Tariff Action |

HTS Subheadings |

Share of Targeted Imports (%) |

Average Tariff in 2018 (%) |

Additional Tariff as of October 18, 2019 (%) |

||||

|

Aircraft |

1 |

38.5 |

0 |

10 |

||||

|

Whiskies/Liqueurs |

2 |

20.9 |

0 |

25 |

||||

|

Wine |

1 |

16.8 |

0.7 |

25 |

||||

|

Cheese and Dairy |

64 |

8.8 |

10.8 |

25 |

||||

|

Olives and Olive Products |

11 |

4.8 |

1.5 |

25 |

||||

|

Heavy Equipment, Machinery, Tools |

15 |

4.2 |

0.5 |

25 |

||||

|

Pork and Pork Products |

9 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

25 |

||||

|

Biscuits, Waffles, Wafers |

2 |

1.5 |

0 |

25 |

||||

|

Fruit and Fruit Juice |

16 |

1.0 |

9.0 |

25 |

||||

|

Coffee |

3 |

0.4 |

0 |

25 |

||||

|

Clothes |

13 |

0.2 |

11.6 |

25 |

||||

|

Fish/Seafood |

10 |

0.0 |

0.1 |

25 |

||||

|

Blankets and Linens |

4 |

0.0 |

8.5 |

25 |

||||

|

Other (Books/Paper Products) |

5 |

0.6 |

0 |

25 |

||||

|

Other (Appliances/Parts) |

2 |

0.5 |

2.3 |

25 |

||||

Source: CRS using data from USTR and USITC. HTS = Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States.

Notes: EU28 includes UK, which left the EU in 2020. Based on USTR's lists of products (84 Federal Register 54245, October 9, 2019; and 84 Federal Register 55998, October 18, 2019). Product descriptions in Annex B are provided for informational purposes, may cover only a portion of the HTS 8-digit subheadings, and do not necessarily delimit the scope of the action. For detail, see Annex A. The estimated average tariff rate is illustrative, applies only to the subheadings in Annex B covered by the tariff action, and is calculated by dividing estimated import duties collected by import value in 2018.

Selected U.S.-EU Agricultural Trade Issues

In January 2019, USTR announced its negotiating objectives for a U.S.-EU trade agreement, following a public comment period and a hearing involving several leading U.S. agricultural trade associations.23 These objectives include agricultural policies—both market access and non-tariff measures such as tariff rate quotas (TRQ) administration and other regulatory issues. Among regulatory issues, key U.S. objectives include harmonizing regulatory processes and standards to facilitate trade, including SPS standards, and establishing specific commitments for trade in products developed through agricultural biotechnologies. The U.S. objectives also include addressing GIs by protecting generic terms for common use. U.S. agricultural interests generally support including agriculture in a U.S.-EU trade agreement.24 The stated overarching goal for the U.S. side is addressing the U.S. trade deficit in agricultural products with the European Union.25

Early on, the EU indicated that it was planning for a more limited negotiation that does not include agricultural products and policies.26 The EU negotiating mandate, dated April 2019, states that a key EU goal is "a trade agreement limited to the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods only, excluding agricultural products."27 Several Members of Congress opposed the EU's decision to exclude agricultural policies in its negotiating mandate. A letter to USTR from a bipartisan group of 114 House members states that "an agreement with the EU that does not address trade in agriculture would be, in our eyes, unacceptable."28 Senate Finance Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley reiterated, "Bipartisan members of the Senate and House … have voiced their objections to a deal without agriculture, making it unlikely that such a deal would pass Congress."29

Then, in January 2020, public statements by U.S. and EU officials signaled the possibility that the U.S.-EU trade talks might include negotiation on SPS and regulatory barriers to agricultural trade. It is not clear, however, that both sides agree on which specific types of non-tariff trade barriers might actually be part of the U.S.-EU trade talks. As reported in the press, statements by some USDA officials have suggested that selected SPS barriers as well as GIs would need to be addressed by the trade talks.30 Meanwhile, other press reports indicate that some EU officials have downplayed the extent that certain non-tariff barriers—such as biotechnology product permits, approval of certain pathogen rinses for poultry, regulations on pesticides, or food standards—would be part of the talks; instead, regulatory barriers might be lowered for certain "non-controversial" foods.31 The United States continues to push for additional concessions from the EU. More formal discussions are expected in the spring of 2020—in an effort to ease trade tensions regarding the imposition of retaliatory tariffs.32

The EU has taken certain measures to avoid escalating agricultural trade tensions with the United States. For example, it has expanded the U.S.-specific quota for EU imports of hormone-free beef, increased imports of U.S. soybeans as a source of biofuels,33 approved a number of long-pending genetically engineered products for food and feed uses,34 and proposed to lift a ban on certain pest-resistant American grapes in EU wine production,35 and other trade-related measures.

In a separate but indirectly related action, in August 2019, USTR asked the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) to conduct an investigation examining SPS barriers related to pesticide maximum residue levels (MRLs) across all U.S. markets, including Europe.36

Previously, during T-TIP negotiations, both market access and non-tariff barriers were part of the U.S. negotiating objectives.37 At that time, non-tariff barriers to agricultural trade—including SPS and TBT measures, and GIs—were among the agricultural issues actively debated. In addition, regulatory coherence and cooperation was part of USTR's stated objectives. Some of the same issues that proved to be challenging during the T-TIP talks may continue to challenge negotiators. Various studies at the time reported that removing tariff and non-tariff barriers in U.S.-EU trade would result in economic benefits to the U.S. and EU agricultural sectors.38 Another study by the European Parliament acknowledged that gains from tariff cuts would be limited unless regulatory and administrative barriers were also addressed.39

Market Access

Market access issues are not slated to be discussed in the U.S.-EU trade talks. However, these issues remain important for U.S. agricultural exporters. This is especially true regarding the EU's use of restrictive tariff rate quotas (TRQs) on certain agricultural products. TRQs allow imports of fixed quantities of a product at a lower tariff. Once the quota is filled, a higher tariff is applied on additional imports. The EU allocates TRQs to importers using licenses issued by the member states' national authorities. Only companies established in the EU may apply for import licenses.40 For exports under a U.S.-specific TRQ, a certificate of origin must be supplied. The EU applies TRQs on many types of beef and poultry products, sheep and goat meat, dairy products, cereals, rice, sugar, and fruit and vegetables.41 Some products are heavily protected by both TRQs and non-tariff SPS measures.42

Import tariffs for agricultural products into Europe tends to be relatively high compared to tariffs for similar products into the United Sates. The WTO reports that the simple average most-favored-nation (MFN) tariff43 applied to agricultural products entering the United States is about 5%, compared to an average tariff of about 13% for products entering the EU.44 Including all products imported under an applied tariff or a TRQ, USDA reports that the calculated average rate across all U.S. agricultural imports is roughly 12%, well below the EU's average of 30%.45 By commodity group, EU tariffs average more than 40% for imported meat products, grains, and grain products and average at or above 20% for most fruit and vegetable products. For some products, EU tariffs are even greater, averaging more than 80% for imported dairy products, more that 50% for sugar cane and sweeteners, and nearly 350% for sugar beets.46 The EU has concluded preferential trade agreements with more than 35 non-EU countries and continues to negotiate agreements with several others.47 This preferential access provides U.S. export competitors an advantage over U.S. agricultural exporters, particularly in countries where the United States does not have a preferential agreement in place.

Previously, during the T-TIP negotiations, Senate leadership sent a letter to USTR reiterating that a final agreement would need to include "a strong framework for agriculture," including "tariff elimination on all products—including beef, pork, poultry, rice, and fruits and vegetables" and that "liberalization in all sectors of agriculture" was a priority, if the agreement were to obtain the support of Congress.48 The letter also addressed the importance of "longstanding regulatory barriers," including the EU's import approval process of U.S. biotechnology products and GI protections promoted by the EU.

Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade

High tariff barriers are further exacerbated by additional non-tariff barriers that may limit U.S. agricultural exports, including SPS measures, and other types of non-tariff barriers. Non-tariff measures (NTMs) generally refer to policy measures other than tariffs that may have a negative economic effect on international trade.49 NTMs include both technical and nontechnical measures. Technical measures include both SPS and TBTs and pre-shipment formalities and related requirements that are intended to govern public health and food safety. Nontechnical measures include quotas, price control measures, rules of origin requirements, and government procurement restrictions.

Non-tariff barriers affect agricultural trade in various ways, including delays in reviews of biotech products (creating barriers to U.S. exports of grain and oilseed products), prohibitions on growth hormones in beef production and certain antimicrobial and pathogen reduction treatments (creating barriers to U.S. meat and poultry exports), and burdensome and complex certification requirements (creating barriers to U.S. processed foods, animal products, and dairy products).50 Extensive EU regulations and difficulty finding up-to-date information are among the primary concerns of U.S. businesses, particularly for makers of processed foods.51 U.S. businesses report a lack of a science-based focus in establishing SPS measures, difficulty meeting food safety standards and obtaining product certification, differences across countries in food labeling requirements, and stringent testing requirements that are often applied inconsistently across EU member nations.

Non-tariff barriers to agricultural trade—including SPS and TBT measures, and GIs—were among the agricultural issues actively debated in the T-TIP negotiation. Previous negotiations were complicated by longstanding trade disputes between the United States and EU involving food safety and product standards that are often embodied in laws and regulations in the United States and EU, as well as separate requirements that may be in force within individual EU member states. For example, the EU restricts some types of genetically engineered (GE) seed varieties and also prohibits the use of hormones in meat production and certain pathogen reduction treatments in poultry production. As these types of practices are commonplace in the United States, this tends to restrict U.S. agricultural exports to the EU. Other EU regulations and standards involve pesticide residues on foods, drug residues in animal production, and certain animal welfare requirements that may vary from those in the United States. The United States has also opposed the EU's GI protections that govern product labeling on products within the EU and within some countries that have a formal trade agreement with the EU. Such GI protections also tend to restrict U.S. agricultural exports to the EU and to some other countries where such protections have been put in place.

As part of a trade negotiation, non-tariff barriers tend to be broadly grouped along with other issues related to regulatory coherence. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce defines regulatory coherence as "good regulatory practices, transparency, and stakeholder engagement in a domestic regulatory process" and regulatory cooperation as "the process of interaction between U.S. and EU regulators, founded on the benefits regulators can achieve through closer partnership and greater regulatory interoperability."52 Related terminology may refer interchangeably to regulatory convergence, cooperation, and/or harmonization. Trade negotiations involving regulatory and intellectual property rights issues have focused, in part, on the goals of ensuring greater transparency, harmonization, and coherence to improve cooperation and streamline the regulatory approval process among the trading partners.

Previous USDA estimates calculated the ad valorem equivalent53 effects of EU non-tariff barriers to U.S. agricultural exports, which were estimated to range from 23% to 102% for some more heavily protected products, including meat products, fruits and vegetables, and some crops.54

In general, SPS and related regulatory issues tend to be addressed in free trade agreements (FTAs) within an agreement's agriculture chapter or chapter on regulatory coherence, while GIs tend to be addressed along with other types of intellectual property rights (IPR) issues, in an FTA's IPR chapter. The following section provides additional background on SPS and TBT measures, as well as GI protections.

SPS/TBT Issues

SPS measures are laws, regulations, standards, and procedures that governments employ as "necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health" from the risks associated with the spread of pests, diseases, or disease-carrying and causing organisms, or from additives, toxins, or contaminants in food, beverages, or feedstuffs.55 Examples include product standards, requirements for products to be produced in disease-free areas, quarantine and inspection procedures, sampling and testing requirements, residue limits for pesticides and drugs in foods, and limits on food additives. TBT measures cover both food and non-food traded products. TBTs in agriculture include SPS measures, but also include other types of measures related to health and quality standards, testing, registration, and certification requirements, as well as packaging and labeling regulations. Both SPS and TBT measures regarding food safety and related public health protection are addressed in various multilateral trade agreements and are regularly notified to and debated within both the SPS Agreement and TBT Agreement within the WTO.56

In general, under the SPS and TBT agreements, WTO members agree to apply such measures, based on scientific evidence and information, only to the extent necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life and health and to not arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between WTO members where identical standards prevail. Member countries are also encouraged to observe established and recognized international standards. Improper use of SPS and TBT measures can create substantial barriers to trade when they are disguised protectionist barriers, are not supported by scientific evidence, or are otherwise unwarranted. Bilateral and regional FTAs between the United States and other countries regularly address SPS and TBT matters. Provisions in most U.S. FTAs have generally reaffirmed rights and obligations of both parties under the WTO SPS and TBT agreements. Some FTAs have established standing bilateral committees to enhance understanding of each other's measures and to consult regularly on related matters. Other FTAs have included side letters or agreements for the parties to continue to cooperate on scientific and technical issues, which in some cases may be related to certain specific market access concerns.57 Most FTAs have not addressed specific non-tariff trade concerns directly.

Differences in U.S. and EU Laws and Regulations

Regulatory differences between the United States and EU have contributed to trade disputes regarding SPS and TBT rules between the two trading blocs. The United States has several formal WTO trade disputes regarding SPS and TBT measures with the EU. These include concerns regarding the EU's prohibitions on the use of growth-promoting hormones58 (and ractopamine59) in meat production, the EU's restrictions on chemical treatments ("pathogen reduction treatments" or "PRTs") on U.S. poultry,60 and the EU's approval process of biotechnology products.61 Other SPS concerns have involved regulations related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, commonly known as mad cow disease) and regulations involving plant processing, chemical residues, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, antibiotics, and animal welfare.

There are major differences in how the United States and the EU regulate food safety and related public health protection, including various administrative and technical review differences, which in turn influences how each applies various SPS and TBT measures. Such differences have often been central to SPS and TBT disputes, including those involving the use of hormones in meat production and pathogen reduction treatments in poultry processing. Other disputes invoking the SPS and TBT agreements between the U.S. and EU have included beef and poultry products, eggs, frozen bovine semen, milk products, animal byproducts, seafood, pesticide and animal drug residues, seeds, wheat, wine and spirits, and food packaging requirements.62

Differences are also evident in how the United States and EU regard biotechnology in agricultural production. In general, EU officials have been cautious in allowing genetically engineered crops—commonly referred to in Europe as genetically modified organisms (or GMOs)—to enter the EU market. As such, any GE-derived food and feed must be labeled accordingly. The EU's regulatory framework regarding biotechnology is generally regarded as one of the most stringent systems worldwide.63 During the T-TIP negotiations, U.S. agricultural and food groups actively called for changes to the EU's approach for approving and labeling biotechnology products.64

The EU has reported concerns about perceived U.S. SPS barriers to EU exports of sheep and goat meat, egg products, beef, certain dairy products, live bivalve mollusks, apples, and pears, along with difficulties protecting its own GIs on certain food and drinks.65 Other EU concerns have involved the use of "Buy American" restrictions in the United States governing public procurement. During the T-TIP negotiations, some expressed concern that including "Buy American" provisions could affect local food procurement, including restricting bidding contract preferences contained in U.S. and EU farm-to-school programs.66

The EU's application of the so-called precautionary principle remains central to the EU's risk management policy regarding food safety and animal and plant health and is often cited as the rationale behind the EU's more risk-averse approach.67 The precautionary principle was reportedly referenced as part of the 1992 Treaty on European Union that further integrated the EU, and its use was further outlined in a 2000 communication and then formally established in EU food legislation in 2002 (Regulation EC No 178/2002).68 The EU's 2000 communication further outlines guidelines for implementation, the basis for invoking the principle, and the general standards of application. Regarding international trade, under EU law, the precautionary principle provides for "rapid response" to address "possible danger to human, animal, or plant health, or to protect the environment" and can be used to "stop distribution or order withdrawal from the market of products likely to be hazardous."69 Although the principle may not be used as a pretext for protectionist measures, many countries have challenged some EU actions that invoke the precautionary principle as "protectionist." The EU, however, continues to invoke the precautionary principle to justify its policies regarding various regulatory issues and generally rejects arguments, on the grounds of risk management, that the lack of clear evidence of harm is not evidence of the absence of harm.70

No universally agreed-upon definition of the precautionary principle exists, and many differently worded or conflicting definitions can be found in international law. However, within the context of the WTO and the SPS agreement, the precautionary principle (or precautionary approach) allows a country to set higher standards and methods of inspecting products. It also allows countries to take "protective action"—including restricting trade of products or processes—if they believe that scientific evidence is inconclusive regarding their potential impacts on human health and the environment (provided the action is consistent and not arbitrary). The WTO has generally acknowledged that the need to take precautionary actions in the face of scientific uncertainty has long been widely accepted, particularly in the fields of food safety and plant and animal health protection.71 Examples might include a sudden outbreak of an animal disease that is suspected of being linked to imports, which may require a country to impose certain trade restrictions while the outbreak is assessed.72

Application of the precautionary principle by some countries remains an ongoing source of contention in international trade, particularly for the United States, and is often cited as a reason why some countries may restrict imports of some food products and processes.73

Addressing SPS and TBT Measures in FTA Negotiations

In the lead up to the previous T-TIP and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations,74 there were active efforts to "go beyond" the rules, rights, and obligations in the WTO SPS Agreement and TBT Agreement, as well as commitments in existing U.S. FTAs. These efforts were referred to as "WTO-Plus" rules or, alternatively, as "SPS-Plus" and "TBT-Plus" rules.75 Related efforts called for improvements in regulatory cooperation and coherence, along with enhanced partnerships and interactions among regulators in each country.

Modernizing the rules governing the application of SPS and TBT measures in U.S.-EU trade by incorporating "SPS-Plus" and "TBT-Plus" rules as part of a trade agreement could represent a positive step for U.S. food and agricultural exporters. Changes regarding SPS and TBT measures agreed to in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the U.S.-China Phase One Trade Agreement incorporated policy changes regarding SPS and TBT measures consistent with previous "SPS-Plus" and "TBT-Plus" efforts.76 According to USITC, USMCA "goes further in requiring transparency and encouraging harmonization or equivalence of SPS measures" and incorporates all of the proposed enhanced TPP disciplines "in the areas of equivalence, science and risk analysis, transparency, and cooperative technical consultations."77 Some industry representatives claim that USMCA "goes beyond TPP in establishing deadlines for 'import checks,' by requiring importing parties to inform exporters or importers within five days of shipments being denied entry."78 Both agreements contain language that directly relates to the use of biotechnology.79

Alternative efforts to modify the EU's application of the precautionary principle could present more of a challenge for U.S. agricultural producers and exporters. Previously, during the T-TIP negotiations, some in the U.S. agriculture and food industry urged U.S. negotiators to address the EU's use and application of the precautionary principle. Many U.S. agricultural and food organizations contended that the EU's application of the precautionary principle undermines sound science and innovation and results in "unjustifiable restrictions" on U.S. exports,80 allowing the EU "to put in place restrictions on products or processes when they believe that scientific evidence on their potential impact on human health or the environment is inconclusive."81 Some asserted that application of the principle results in a bias against new technologies, such as biotechnology and nanotechnology.82 As a result, these groups said that "science-based decision making and not the precautionary principle must be the defining principle in setting up mechanisms and systems" to address SPS concerns.83 The U.S. Chamber of Commerce supported a "science-based approach to risk management, where risk is assessed based on scientifically sound and technically rigorous standards" and opposed "the domestic and international adoption of the precautionary principle as a basis for regulatory decision making."84 Many in Congress also called for "effective rules and enforceable rules to strengthen the role of science" to resolve international trade differences.85

More recently, the EU's SPS were among the issues that raised the most concerns during a WTO review of the EU's trade policies. Among the cited concerns were certain SPS measures that were viewed to be not based on science or on international standards, and that were also deemed to not allow for adequate opportunity to take into account for the views of third countries.86

Efforts to Resolve SPS and TBT Measures Outside FTA Negotiations

Outside of the FTA negotiation process, various U.S. federal agencies regularly address trade concerns involving SPS and TBT measures as part of their day-to-day oversight and regulatory responsibilities. For example, USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) administers various regulatory and control programs pertaining to animal and plant health and quarantine, humane treatment of animals, and the control and eradication of pests and diseases. APHIS also oversees SPS certification requirements for imported and exported agricultural goods.87 This work is ongoing.88

The United States also maintains ongoing interagency processes and mechanisms to identify, review, analyze, and address foreign government standards-related measures that may be barriers to trade. These activities are coordinated through the USTR-led Trade Policy Staff Committee, which is composed of representatives from several federal agencies, including USDA, the Department of Commerce, and the State Department. USTR also chairs an interagency group (i.e., both USDA and non-USDA agencies with SPS and TBT responsibilities) that reviews SPS and TBT measures that are notified to the WTO, as required under the SPS and TBT agreements. These agency officials also work with their international counterparts on concerns involving SPS and TBT measures.89 USTR tracks issues related to such measures as part of its annual reports.90

Geographical Indications

GIs are geographical names that act to protect the quality and reputation of a distinctive product originating in a certain region. The term GI is most often applied to wines, spirits, and agricultural products. GIs allow some food producers to differentiate their products in the marketplace. GIs may also be eligible for relief from acts of infringement or unfair competition. While GIs may protect consumers from deceptive or misleading labels, they can also impair trade when names that are considered common or generic in one market are protected in another. Examples of registered or established GIs include Parmigiano Reggiano cheese and Prosciutto di Parma ham from the Parma region of Italy, Toscano olive oil from the Tuscany region of Italy, Roquefort cheese from France, Champagne from the region of the same name in France, Irish whiskey, Darjeeling tea, Florida oranges, Idaho potatoes, Vidalia onions, Washington State apples, and Napa Valley wines.91

GIs are an example of IPR, along with patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets. The use of GIs has become a contentious international trade issue, particularly for U.S. wine, cheese, and sausage makers. In general, some consider GIs to be protected intellectual property, while others consider them to be generic or semi-generic terms. GIs are included among other IPR issues in the current U.S. trade agenda.92 GIs were an active area of debate during the T-TIP negotiations. Laws and regulations governing GIs differ markedly between the United States and EU, which further complicates this issue.

GIs are protected by the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which sets binding minimum standards for intellectual property protection that are enforceable by the WTO's dispute settlement procedure. Under TRIPS, WTO members must recognize and protect GIs as intellectual property. Both the United States and the EU are signatories of TRIPS and therefore subject to its rights and obligations. Accordingly, under TRIPS, the United States and EU have committed to providing a minimum standard of protection for GIs (i.e., protecting GI products to avoid misleading the public and prevent unfair competition) and an "enhanced level of protection" to wines and spirits that carry a GI, subject to certain exceptions. TRIPS builds on treaties administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization, a specialized agency in the United Nations with the mission to "lead the development of a balanced and effective international intellectual property (IP) system."93 It also oversees the "International Register of Appellations of Origin" established in the Lisbon Agreement for the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their International Registration. The agreement's multilateral register covers food products and beverages and related products, as well as non-food products.94

The EU's GI program remains a contentious issue for some U.S. producer groups, particularly among wine, cheese, and sausage makers. Some have long expressed their concerns about EU protections for GIs, which they claim are being misused to create market and trade barriers.95 Much of this debate involves certain terms used by cheesemakers, such as parmesan, asiago, and feta cheese, which the U.S. cheese sectors consider to be generic terms. For example, feta cheese produced in the United States may not be exported for sale in the EU, since only feta produced in countries or regions currently holding GI registrations may be sold commercially. A 2019 study commissioned by the U.S. dairy industry forecasts declining U.S. cheese exports due to expanding restrictions on parmesan, asiago, and feta cheese.96 Another study concluded that up to $15 million in cheese trade might need to be relabeled due to the restriction on certain GI terms, while other traded foods, such as oilseeds and vinegars, would experience little impact.97

Some U.S. industry groups, however, are trying to institute protections for U.S. products—similar to those in the EU GI system—to promote certain distinctive American agricultural products. The American Origin Products Association represents certain U.S. potato, maple syrup, ginseng, coffee, and chile pepper producers and certain U.S. winemakers, among other regional producer groups. It seeks to work with federal authorities to create "a list of qualified U.S. distinctive product names, which correspond to the GI definition."98

Differences in U.S. and EU Laws and Regulations

Laws and regulations governing GIs differ markedly between the United States and EU. In the United States, GIs generally fall under the common law right of possession or "first in time, first in right" as trademarks or collective or certification marks under the purview of the existing trademark regime, administered by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) and protected under the U.S. Trademark Act.99 Trademarks are distinctive signs that companies use to identify themselves and their products or services to consumers and can take the form of a name, word, phrase, logo, symbol, design, image, or a combination of these elements. Trademarks do not refer to generic terms, nor do they refer exclusively to geographical terms.100 Trademarks may refer to geographical names to indicate the specific qualities of goods either as certification marks or as collective marks.101 PTO does not have a special database register for GIs in the United States. PTO's trademark register, the U.S. Trademark Electronic Search System, contains GIs registered as trademarks, certification marks, and collective marks.102 USTR says that EU farm products hold nearly 12,000 trademarks.103 These register entries are not designated with any special field (such as "geographical indications") and cannot be readily compiled into a complete list of registered GIs. In the United States, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB)104 also plays a role overseeing the labeling of wine, malt beverages, beer, and distilled spirits.105

In the EU, a series of regulations governing GIs was initiated in the early 1990s covering agricultural and food products, wine, and spirits. Legislation adopted in 1992 covering agricultural products (not including wines and spirits)106 was replaced by changes enacted in 2006 following a WTO panel ruling that found some aspects of the EU's scheme inconsistent with WTO rules.107 The new rules came into force in January 2013.108 The EU laws and regulations provide product registration markers for the different quality schemes.109 The EU regulations establish provisions regarding products from a defined geographical area given linkages between the characteristics of products and their geographical origin. The EU defines a GI as "a distinctive sign used to identify a product as originating in the territory of a particular country, region or locality where its quality, reputation or other characteristic is linked to its geographical origin."110

EU registered products often fall under GI protections in certain third-country markets, and some EU GIs have been trademarked in some non-EU countries. This has become a concern for U.S. agricultural exporters following a series of trade agreements the EU has concluded with Canada, Japan, South Korea, South Africa, and other countries that in many cases are also trading partners of the United States.111 For example, Canada has agreed to recognize a list of 143 EU GIs in Canada,112 and Japan has agreed to recognize more than 200 EU GIs in Japan.113 These GI protections could limit U.S. sales of certain products to these countries. The EU is in the process of negotiating FTAs with several other U.S. trading partners, including Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, and the Mercosur states (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay). Each of these efforts includes a selected list of GIs that would become protected under an FTA between these countries and the European Union.114 In December 2019, the EU also entered into an agreement with China regarding GIs that would protect a reported 100 EU GIs in China.115 As of January 2020, 3,316 product names are registered and protected in the EU for foods, wine, and spirits originating in both EU member states and other countries.116

Addressing GI Barriers in FTA Negotiations

GIs continue to be actively debated as part of the official U.S. trade agenda, involving concerns about their possible improper use as well as the lack of transparency and due process under some country GI systems.117 USTR is working "to advance U.S. market access interests in foreign markets and to ensure that GI-related trade initiatives of the EU, its Member States, like-minded countries, and international organizations, do not undercut such market access," and states that the EU's GI agenda "significantly undermines the scope of trademarks and other [IPR] held by U.S. producers and imposes barriers on market access for American-made goods that rely on the use of common names."118 Statements by USDA officials in early 2020 have signaled that this issue could resurface as part of the U.S.-EU trade talks.119

Previously, during T-TIP negotiations, U.S. officials indicated that the United States would likely not agree to EU demands to reserve certain food names for EU producers and have expressed concerns about the EU's system of protections for GIs.120 At the time, U.S. trade policy objectives regarding the EU's GI protections was to ensure that they "do not undercut U.S. industries' market access" and to defend the use of certain "common food names."121 In general, the United States is seeking protection for current U.S. owners of trademarks that overlap with EU-protected GIs, the ability to use U.S. trademarked names in third countries, and the ability to use U.S. trademarked names in the EU.122

In recent developments, according to USITC, USMCA "increases the transparency of applications, approvals, and cancellations" regarding GIs and "provides guidelines for determining whether a term is customary in common use."123 In addition, a side letter between the United States and Mexico commits Mexico to not restrict market access for a list of more than 30 cheeses.124 USITC says this could "help prevent future losses of U.S. market access for cheeses with common names" such as "blue" or "Swiss" cheese.125 The final U.S.-China Phase One Trade Agreement also addresses longstanding concerns regarding IPR, including GIs, building on previous commitments regarding IPR and GIs.126 The agreement is expected to require that China ensure that it will "not undermine market access for U.S. exports to China of goods" and will apply relevant factors when providing certain GI protections, as well as provide the United States with "necessary opportunities to raise disagreement" regarding GIs.127 GI provisions in these two recent U.S. FTAs, however, could prove to be incompatible with other EU agreements regarding GIs with these countries. For Mexico and Canada, these include GI protections that are likely to be part of the EU-Mexico Global Agreement, as well as existing GI protections in the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. For China, these include GI protections agreed to in the 2019 EU-China agreement protecting certain EU GIs in China.128

Next Steps

The U.S.-EU Trade Agreement negotiations present Congress with the challenge of determining to what extent food and agriculture issues will be addressed in the trade talks, if at all. Although market access and tariff reductions may be off the table, addressing regulatory restrictions and other non-tariff barriers to U.S. agricultural trade are considered important for many U.S. producers. Some press reports indicate that certain non-tariff barriers and regulatory cooperation could become part of the new trade talks, while other press reports raise questions about the EU's willingness to address specific types of non-tariff barriers as part of the negotiation. Even if regulatory coherence and cooperation become part of the U.S.-EU trade talks, their resolution in a manner that benefits U.S. agricultural exporters is far from assured. Instead, some of the same non-tariff and regulatory barriers to U.S. trade that proved to be challenging during the T-TIP negotiation could prove to be equally intractable today.

The UK's exit from the EU could also complicate future trade negotiations. The UK is a close ally of the United States and has been one of its strongest advocates among the EU bloc. In general, the regulatory framework and actions taken by the UK's Food Standards Agency are more aligned with those in the United States.129 Now that the UK is no longer part of the EU, the EU trade gains for U.S. agriculture could be reduced while its agricultural trade deficit may become more pronounced, given a more favorable trade situation with the UK.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Letter from USTR Robert E. Lighthizer to then-Speaker of the House of Representatives Paul Ryan, October 16, 2018. This action began a congressionally-mandated 90-day consultation period under TPA prior to the launch of negotiations. USTR held a public hearing on negotiating objectives for a U.S.-EU trade agreement in December 2018. |

| 2. |

The EC is the EU's executive body and represents the interests of the EU as a whole. It is responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the EU's treaties, and day-to-day running of the EU. |

| 3. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43387, Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) Negotiations, and CRS Report R44564, Agriculture and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) Negotiations. |

| 4. |

EC, "EU-US Relations: Interim Report on the Work of the Executive Working Group," January 30, 2019. For background on U.S.-EU relations and other policy topics that have been part of the negotiation, see CRS In Focus IF11094, U.S.-European Relations in the 116th Congress and CRS In Focus IF11209, Proposed U.S.-EU Trade Agreement Negotiations. |

| 5. |

A Section 232 investigation is conducted to determine the effects of specified imports on national security. For more information, see CRS Report R45249, Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress |

| 6. |

For a listing of the EU member countries, see http://europa.eu/about-eu/countries/member-countries/. |

| 7. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45944, Brexit: Status and Outlook. The UK includes England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. |

| 8. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11123, Brexit and Outlook for U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement. |

| 9. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11209, Proposed U.S.-EU Trade Agreement Negotiations. |

| 10. |

On January 24, 2020, President Trump issued a proclamation expanding the tariffs to certain steel and aluminum "derivatives." For more detail on Section 232, see CRS In Focus IF10667, Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962; and CRS Report R45249, Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress. |

| 11. |

For more background, see CRS Insight IN10971, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Affected Trade, and also CRS In Focus IF10931, U.S.-EU Trade and Economic Issues. |

| 12. |

For a full list of product codes subject to higher duties, see Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/886 available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32018R0886&from=EN. The EU's list also specifies additional tariffs of 10% to 50%, which may apply after the WTO dispute process is complete. See also USDA, "EU Imposes Additional Tariffs on U.S. Products," GAIN Report Number: E18045, June 21, 2018. The United States is pursuing a case at the WTO against the EU over these tariff actions. |

| 13. |

The Common External Tariff applies to the EU28 until the EU27-UK transition period ends on December 31, 2020. |

| 14. |

J.S. Grant, et al., "The 2018-2019 Trade Conflict: A One-Year Assessment and Impacts of U.S. Agricultural Exports," CHOICES Magazine, Quarter 4, 2019. |

| 15. |

USTR press release, "U.S. Wins $7.5 Billion Award in Airbus Subsidies Case," October 2, 2019. For other background, see CRS In Focus IF11364, Boeing-Airbus Subsidy Dispute: Recent Developments. |

| 16. |

WTO, European Communities and Certain Member States–Measures Affecting Trade In Large Civil Aircraft, WT/DS316/ARB, October 2, 2019. |

| 17. |

For a list of U.S. imports subject to higher duties, see 84 Federal Register 54245, October 9, 2019. |

| 18. |

For other background, see CRS In Focus IF11364, Boeing-Airbus Subsidy Dispute: Recent Developments. On December 2, 2019, a WTO compliance panel rejected the EU's claims that EU subsidies had been brought in line with WTO rulings. For more detail, see WTO, European Communities and Certain Member States–Measures Affecting Trade In Large Civil Aircraft, "Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the European Union and Certain Member States, Report of the Panel," WT/DS316/RW2, December 2, 2019. |

| 19. |

Again, despite Brexit, U.S. imports from the UK will continue to be subject to these additional tariffs through 2020. |

| 20. |

Separately, antidumping and countervailing duties may apply on certain agricultural goods traded between the United States and EU, including for ripe olives and biofuels. See https://enforcement.trade.gov/trcs/foreignadcvd/. The EU's list is at https://trade.ec.europa.eu/actions-against-eu-exporters/cases/. For more background on the U.S.-EU dispute over U.S. olive imports, see CRS Report R45728, Major Agricultural Trade Issues in the 116th Congress. |

| 21. |

84 Federal Register 67992, December 12, 2019. |

| 22. |

For more detail, see WTO DS353: "United States—Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft." |

| 23. |

83 Federal Register 57526, November 15, 2018. |

| 24. |

Letter from U.S. agricultural groups to USTR Robert E. Lighthizer, December 17, 2018; and American Farm Bureau Federation, "US-EU Trade Negotiations," February 2019. See also comments at USTR's "Public Hearing on Negotiating Objectives for U.S.-EU Trade Agreement," December 14, 2018 (Docket No. USTR-2018-0035). |

| 25. |

USTR, "United States-European Union Negotiations, Summary of Specific Negotiating Objectives," January 2019. |

| 26. |

See EC, "EU-US Relations: Interim Report on the work of the Executive Working Group," January 30, 2019. |

| 27. |

See Council of the European Union, "Trade with the United States: Council Authorises Negotiations on Elimination of Tariffs for Industrial Goods and on Conformity Assessment," press release, April 15, 2019. |

| 28. |

Letter to USTR Robert E. Lighthizer from 114 House Members, March 14, 2019. |

| 29. |

U.S. Senate Finance Committee, "Grassley Statement on the Omission of Agriculture from E.U. Trade Negotiating Mandate," press release, April 15, 2019. |

| 30. |

See R. McCrimmon, "Perdue Lays Out Ag Objectives in U.S. Trade Talks," Politico, January 29, 2020; S. Chase, "Perdue Eyes SPS, GI barriers as Key Issues in Potential US-EU Deal," Agri-Pulse, January 29, 2020; World Trade Online, "Hogan Hopes SPS Solutions Can Break EU-U.S. Ag Impasse," January 17, 2020; and S. Michalopoulos, "US Agriculture Chief Urges EU to Listen to Science, Not Fear-Mongering NGOs," Euractiv, January 27, 2020. |

| 31. |

See, for example, A. Shalal and D. Lawder, "As Trump Takes Aim at EU Trade, European Officials Brace for Fight," Reuters Business News, February 11, 2020; World Trade Online, "Hogan Doubles Down on EU Regulations as U.S. Officials Demand Ag Concessions," February 20, 2020; D. Palmer, "More Than Peanuts: EU Woos Trump with Farming and Industrial Concessions," Politico, February 21, 2020. |

| 32. |

European Parliament press release, "Trade MEPs in Washington, DC, to Discuss EU-US Trade Relations," February 21, 2020; and World Trade Online, "U.S., EU Negotiators Accelerating Talks, Eyeing Monthly High-Level Meetings," February 13, 2020. |

| 33. |

See "Joint U.S.-EU Statement Following President Juncker's Visit to the White House," July 25, 2018. |

| 34. |

USDA, "European Commission Authorizes Ten Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs)," GAIN Report E19028, August 5, 2019. |

| 35. |

Council of the European Union, Interinstitutional file: 2018/0218 (COD), June 1, 2018. |

| 36. |

See letter from USTR Robert E. Lighthizer to David S. Johanson, USITC Chairman, August 30, 2019. |

| 37. |

For more background, CRS Report R44564, Agriculture and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) Negotiations. |

| 38. |

See, for example, J. Beckman et al., Agriculture in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership: Tariffs, Tariff-Rate Quotas, and Non-Tariff Measures, USDA, ERR-198, November 2015; S. Arita et al., Estimating the Effects of Selected Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and Technical Barriers to Trade on U.S.-EU Agricultural Trade, USDA, ERR-199, November 2015; and Ecorys, Trade SIA on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) Between the EU and the USA, Draft Interim Technical Report, May 2016. |

| 39. |

European Parliament, Risks and Opportunities for the EU Agri-Food Sector in a Possible EU-US Trade Agreement, July 2014. |

| 40. |

USDA, "Tariff Rate Quotas," http://www.usda-eu.org/trade-with-the-eu/tariffs/tariff-rate-quotas/. Council Regulation 717/2008 establishes a procedure for administering quantitative quotas. Rules on the administration of TRQs for agricultural products under a system of import licenses are set out in Council Regulation 1301/2006. |

| 41. |

M. Normile et al., U.S. and EU Farm Policy—How Similar?, USDA, WRS-04-04, February 2004. |

| 42. |

See, for example, S. Arita et al., Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and Tariff-Rate Quotas for U.S. Meat Exports to the European Union, USDA, LDPM-245-01, December 2014. |

| 43. |

MFN tariffs are normal non-discriminatory tariffs charged on imports (excluding preferential tariffs under free trade agreements and other schemes or tariffs charged inside quotas) applied by countries/customs territories. |

| 44. |

WTO, "World Tariff Profiles," 2019. Average WTO MFN tariff rates do not take into consideration tariff rates under a TRQ or preferential trade agreement, or temporary increases in tariffs resulting from any ongoing trade disputes. |

| 45. |

USDA, "Why Trade Promotion Authority Is Essential for U.S. Agriculture and T-TIP," February 2015. |

| 46. |

P. Gibson et al., Profiles of Tariffs in Global Agricultural Markets, USDA, AER-796, January 2001. See Table 2. The EU tariff schedule can be accessed at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2014:312:FULL&from=EN. |

| 47. |

For a listing of the EU's free trade agreements and negotiations with non-EU nations, see EC, "Overview of FTA and other Trade Negotiations, November 2019, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/december/tradoc_118238.pdf. See also EC, "2019 Annual Report on the Implementation of the EU Trade Agreements." |

| 48. |

Letter from Senate leadership to former Ambassador Froman, USTR, April 22, 2016. |

| 49. |

For more information, see United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Non-Tariff Measures: Evidence from Selected Developing Countries and Future Research Agenda, 2010. |

| 50. |

S. Arita et al., Estimating the Effects of Selected Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and Technical Barriers to Trade on U.S.-EU Agricultural Trade, USDA, ERR-199, November 2015. |

| 51. |

See, for example, USITC, Trade Barriers that U.S. Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Perceive as Affecting Exports to the European Union, Investigation 332-541, USITC Publication 4455, March 2014. |

| 52. |

U.S. Chamber of Commerce, "Regulatory Coherence and Cooperation in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)," February 27, 2015. |

| 53. |

Ad valorem equivalent refers to import duties or other charges levied on a traded good, expressed as a percentage of the value of the imported item and not based on the weight, size, or quantity of the item. |