Russia: Background and U.S. Policy

Over the last five years, Congress and the executive branch have closely monitored and responded to new developments in Russian policy. These developments include the following:

increasingly authoritarian governance since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidential post in 2012;

Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region and support of separatists in eastern Ukraine;

violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty;

Moscow’s intervention in Syria in support of Bashar al Asad’s government;

increased military activity in Europe; and

cyber-related influence operations that, according to the U.S. intelligence community, have targeted the 2016 U.S. presidential election and countries in Europe.

In response, the United States has imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions related to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria, malicious cyber activity, and human rights violations. The United States also has led NATO in developing a new military posture in Central and Eastern Europe designed to reassure allies and deter aggression.

U.S. policymakers over the years have identified areas in which U.S. and Russian interests are or could be compatible. The United States and Russia have cooperated successfully on issues such as nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, support for military operations in Afghanistan, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, the International Space Station, and the removal of chemical weapons from Syria. In addition, the United States and Russia have identified other areas of cooperation, such as countering terrorism, illicit narcotics, and piracy.

Like previous U.S. Administrations, President Donald J. Trump has sought to improve U.S.-Russian relations at the start of his tenure. In its first six months, the Trump Administration expressed an intention to pursue cooperation or dialogue with Russia on a range of pursuits (e.g., Syria, North Korea, cybersecurity). At initial meetings with President Putin in April and July 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and President Trump said they agreed to find ways to improve channels of communication and begin addressing issues dividing the two countries.

At the same time, the Administration has indicated that it intends to adhere to core international commitments and principles, as well as to retain sanctions on Russia. Secretary Tillerson has stated that Ukraine-related sanctions will remain in place “until Moscow reverses the actions that triggered” them. Secretary Tillerson and other officials also have noted the severity of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the need for an appropriate response.

Since the start of the 115th Congress, many Members of Congress have actively engaged with the Administration on questions concerning U.S.-Russian relations. As of August 2017, Congress has held more than 20 hearings on matters directly relating to Russia, codified and strengthened sanctions through the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-44, Title II), and considered other measures to assess and respond to Russian interference in the 2016 elections, influence operations in Europe, INF Treaty violations, and illicit financial activities abroad.

This report provides background information on Russian politics, economics, and military issues. It discusses a number of key issues for Congress concerning Russia’s foreign relations and the U.S.-Russian relationship.

Russia: Background and U.S. Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Political Structure and Developments

- Democracy and Human Rights

- Government Reshuffles

- September 2016 State Duma Elections

- The Opposition

- The Economy

- Economic Impact of Sanctions

- U.S.-Russian Trade and Investment

- Energy Sector

- Foreign Relations

- Russia and Other Post-Soviet States

- Ukraine Conflict

- NATO-Russia Relations

- EU-Russia Relations

- Russia-China Relations

- Russia's Intervention in Syria

- Russia's Global Engagement

- The Military

- Russia's Military Footprint in Europe

- U.S. Policy Toward Russia

- U.S. Policy Under the Obama Administration

- U.S. Policy Under the Trump Administration

- Congressional Action in the 115th Congress

- Selected Issues in U.S.-Russian Relations

- U.S. Sanctions on Russia

- Ukraine-Related Sanctions

- Sanctions for Malicious Cyber Activity

- Sanctions for Human Rights Violations and Corruption

- Other Sanctions

- Malicious Cyber Activity

- Interference in U.S. Elections

- Other Activities

- Nuclear Arms Control and Nonproliferation

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Over the last five years, Congress and the executive branch have closely monitored and responded to new developments in Russian policy. These developments include the following:

- increasingly authoritarian governance since Vladimir Putin's return to the presidential post in 2012;

- Russia's 2014 annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region and support of separatists in eastern Ukraine;

- violations of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty;

- Moscow's intervention in Syria in support of Bashar al Asad's government;

- increased military activity in Europe; and

- cyber-related influence operations that, according to the U.S. intelligence community, have targeted the 2016 U.S. presidential election and countries in Europe.

In response, the United States has imposed economic and diplomatic sanctions related to Russia's actions in Ukraine and Syria, malicious cyber activity, and human rights violations. The United States also has led NATO in developing a new military posture in Central and Eastern Europe designed to reassure allies and deter aggression.

U.S. policymakers over the years have identified areas in which U.S. and Russian interests are or could be compatible. The United States and Russia have cooperated successfully on issues such as nuclear arms control and nonproliferation, support for military operations in Afghanistan, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear programs, the International Space Station, and the removal of chemical weapons from Syria. In addition, the United States and Russia have identified other areas of cooperation, such as countering terrorism, illicit narcotics, and piracy.

Like previous U.S. Administrations, President Donald J. Trump has sought to improve U.S.-Russian relations at the start of his tenure. In its first six months, the Trump Administration expressed an intention to pursue cooperation or dialogue with Russia on a range of pursuits (e.g., Syria, North Korea, cybersecurity). At initial meetings with President Putin in April and July 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and President Trump said they agreed to find ways to improve channels of communication and begin addressing issues dividing the two countries.

At the same time, the Administration has indicated that it intends to adhere to core international commitments and principles, as well as to retain sanctions on Russia. Secretary Tillerson has stated that Ukraine-related sanctions will remain in place "until Moscow reverses the actions that triggered" them. Secretary Tillerson and other officials also have noted the severity of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the need for an appropriate response.

Since the start of the 115th Congress, many Members of Congress have actively engaged with the Administration on questions concerning U.S.-Russian relations. As of August 2017, Congress has held more than 20 hearings on matters directly relating to Russia, codified and strengthened sanctions through the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-44, Title II), and considered other measures to assess and respond to Russian interference in the 2016 elections, influence operations in Europe, INF Treaty violations, and illicit financial activities abroad.

This report provides background information on Russian politics, economics, and military issues. It discusses a number of key issues for Congress concerning Russia's foreign relations and the U.S.-Russian relationship.

Political Structure and Developments

|

Russia: Basic Facts Land Area: 6.3 million square miles, about 1.8 times the size of the United States. Population: 142.4 million (mid-2016 est.). Administrative Divisions: 83 administrative subdivisions, including 21 ethnic-based republics and the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. Russian law considers Ukraine's occupied region of Crimea and the Crimean city of Sevastopol to be additional administrative subdivisions. Ethnicity: Russian 77.7%; Tatar 3.7%; Ukrainian 1.4%; Bashkir 1.1%; Chuvash 1.0%; Chechen 1.0%; Other 10.2%; Unspecified 3.9% (2010 census). Gross Domestic Product: $1.268 trillion (2016 est.); $26,100 per capita (purchasing power parity) (2016 est.). Political Leaders: President: Vladimir Putin; Prime Minister: Dmitry Medvedev; Speaker of the State Duma: Vyacheslav Volodin; Speaker of the Federation Council: Valentina Matviyenko; Foreign Minister: Sergei Lavrov; Defense Minister: Sergei Shoigu. Source: CIA World Factbook. |

Russia, formally known as the Russian Federation, is the principal successor to the United States' former superpower rival, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, or Soviet Union). In its modern form, Russia came into being in December 1991, after its leaders joined those of neighboring Ukraine and Belarus to dissolve the USSR. From 1922 to 1991, Soviet Russia was the core of the USSR, established in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the civil war that followed. The USSR spanned much the same territory as the Russian Empire before it. Prior to the empire's establishment in 1721, Russian states had existed in various forms for centuries.

Today, Russia's multiethnic federal structure is inherited from the Soviet period and includes regions, republics, territories, and other subunits. The country's constitution provides for a strong presidency and central authority. The government is accountable to the president, not the legislature, and observers consider the presidential Administration rather than the Cabinet (headed by a prime minister) to be "the true locus of power."1

Russia's president is Vladimir Putin, who has led the country as president (2000-2008, 2012-present) or prime minister (2008-2012) for more than 17 years (see "Vladimir Putin" text box, below). In recent years, opinion polls have reported increased levels of support for President Putin. Since the annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region in March 2014, he has consistently received approval from more than 80% of respondents in opinion polls.2 This reported approval level is considerably higher than what Putin received in polls over the previous two years, when his approval rating was in the low 60s.

Russia's bicameral legislature is the Federal Assembly. The upper chamber, the Federation Council, has 170 deputies, two each from Russia's 83 regions and republics (including two major cities, Moscow and St. Petersburg) and four from Ukraine's occupied region of Crimea. These deputies are not directly elected but are chosen by regional executives and legislatures. The lower house, the State Duma, has 450 deputies, half of which are elected by proportional representation and half of which are in single-member districts. The State Duma also includes members from occupied Crimea: four from majoritarian districts and another four from party lists.3

The judiciary is the least developed of Russia's three branches. Courts are widely perceived to be subject to manipulation and control by government officials. The Supreme Court is the highest appellate body. The Constitutional Court rules on the legality and constitutionality of governmental acts and on disputes between branches of government or federative entities. A 2015 law gives the Constitutional Court the legal authority to disregard verdicts by interstate bodies that defend human rights and freedoms, if the court concludes that such verdicts contradict Russia's constitution (although the latter requires compliance of rules established by international treaties over domestic law).4 A Supreme Commercial Court, which handled commercial disputes and was viewed by experts as relatively impartial, was dissolved in September 2014, with its areas of jurisdiction transferred to the Supreme Court; lower-level commercial courts continue to function.

|

|

Sources: Graphic produced by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Map information generated by [author name scrubbed] using data from the Department of State (2015) and Esri, a geographic data company (2014). |

Democracy and Human Rights

Under Putin's rule, Russia has experienced a steady decline in its democratic credentials. At the start of the 2000s, the U.S. government-funded nongovernmental organization (NGO) Freedom House classified Russia as a "hybrid" regime, with democratic and authoritarian elements. By the end of Putin's second term in 2008, Freedom House considered Russia to be a consolidated authoritarian regime. This status continued during the tenure of Putin's handpicked successor for one term, Dmitry Medvedev, despite some signs of liberalization. Since Putin's return to the presidency in 2012, Freedom House has noted a new rise in authoritarian governance in Russia. In its 2016 annual report, Freedom House assigned Russia the same "freedom rating" it gave to China, Yemen, Cuba, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.5

|

Vladimir Putin After more than 15 years in the Soviet Union's Committee for State Security (the KGB), Vladimir Putin held a variety of governmental positions from 1990 to 1998, first in the local government of St. Petersburg (his native city) and then in Moscow. In 1998, Russian President Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin head of the Federal Security Service (FSB), a successor agency to the KGB, and prime minister a year later, in August 1999. Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned on New Year's Eve, 1999, and Putin became acting president. He was elected president in March 2000, with 53% of the vote. Putin served eight years as president before stepping down in 2008, in compliance with constitutional limits on successive terms. His successor was Dmitry Medvedev, a trusted former presidential chief of staff, deputy prime minister, and board chairperson of the state-controlled energy company Gazprom. As prime minister from 2008 to 2012, Putin continued to govern Russia in tandem with Medvedev, who remained informally subordinate to Putin. In September 2011, Medvedev announced that he would not run for reelection, paving the way for Putin to return to the presidency. In exchange, Medvedev was to become prime minister. Putin's return to the presidency had always been plausible, but the announcement was met with some public discontent, particularly in Moscow. A series of protests followed the December 2011 parliamentary elections, which domestic and international observers considered to be marred by fraud and other violations. In March 2012, Putin won the presidency. His current term extends to 2018 (as president, Medvedev extended the next presidential term to six years). Putin has not confirmed if he is planning to run for reelection, although many observers believe he plans to do so. |

Russia's authoritarian consolidation has involved a wide array of nondemocratic practices and human rights violations. The U.S. Department of State's most recent human rights report notes that the Russian government has "increasingly instituted a range of measures ... to harass, discredit, prosecute, imprison, detain, fine, and suppress individuals and organizations critical of the government." The report also notes the "lack of due process in politically motivated cases."6

According to the human rights report, Russian NGOs have been "stymied" and "stigmatize[d]," including through a 2012 law that requires foreign-funded organizations that engage in activity seeking to affect policymaking (loosely defined) to register and identify as "foreign agents." In addition, a 2015 law enables the government to identify as "undesirable" foreign organizations engaged in activities that allegedly threaten Russia's constitutional order, defense capability, or state security, and to close their local offices and bar Russians from working with them.7

As of the start of August 2017, 88 NGOs are classified as foreign agents (of these, 7 have been added since the start of the year).8 In 2014, Russia's main domestic election-monitoring organization, Golos, was the first organization to be so classified. Just before the September 2016 Duma election, a well-known polling organization, the Levada Center, also was branded a foreign agent; in October 2016, a prominent human rights group, Memorial, was so labeled, as well.

Eleven organizations or their subsidiaries have been barred from Russia for "undesirable" activity. In 2015-2016, barred organizations included the National Endowment for Democracy, Open Society Foundations (including the Open Society Institute Assistance Foundations), U.S.-Russia Foundation for Economic Advancement and the Rule of Law, National Democratic Institute, International Republican Institute, and Media Development Investment Fund. In April 2017, three allegedly foreign-registered affiliates of the NGO and civic movement Open Russia were added to the list; Open Russia was founded by former oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who served 10 years in prison on charges deemed by the opposition and most observers to be politically motivated. In June 2017, the German Marshall Fund's Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation also was barred.9

Russian law also limits freedom of assembly and expression. Public demonstrations require official approval, and police have broken up protests by force. The fine for participation in unsanctioned protests can be thousands of dollars; repeat offenders risk imprisonment. In 2016, new "antiterrorism" legislation (known as the Yarovaya Laws) hardened punishments for "extremism" (a crime that has been broadly interpreted to encompass antistate criticism on social media), required telecommunications providers to store data for six months, and imposed restrictions on locations of religious worship and proselytization.

A 2013 law restricts lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender (LGBT) rights by prohibiting "propaganda" among minors (including in the media or on the Internet) that would encourage individuals to consider "non-traditional sexual relationships" as attractive or socially equivalent to "traditional" sexual relationships. In June 2017, the European Court on Human Rights ruled that the law is discriminatory and violates freedom of expression.10

These laws and related discriminatory actions have impacted religious and sexual minorities. In April 2017, for example, Russia's Supreme Court upheld a March order of the Justice Ministry banning the operations of Jehovah's Witnesses in Russia for what it ruled to be "extremist" activity. Since then, Jehovah's Witnesses have reported increased harassment and violence. The Supreme Court rejected an appeal by the organization in July 2017.11

Also in April 2017, Russian media reported that local authorities in Chechnya, a majority-Muslim republic in Russia's North Caucasus, had rounded up more than 100 men on the basis of their suspected homosexuality.12 Reports indicate that detained individuals were beaten and tortured and that at least three died as a result of the roundup (including two reportedly killed by relatives after their release from detention).13 Putin's presidential spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said that the government had no information concerning the allegations, and the local administration's press secretary denied the reports.14 In May 2017, Putin said that he would speak to Russia's prosecutor-general and minister of internal affairs "concerning the rumors" about the detentions, but it is unclear what, if any, subsequent measures the government took.15

Over the years, a number of opposition-minded or critical Russian journalists, human rights activists, politicians, whistleblowers, and others, including opposition politician Boris Nemtsov in 2015, have been reported murdered or have died under mysterious circumstances.16 Although those who commit crimes are often prosecuted, suspicions frequently exist that such crimes are ordered by individuals who remain free.17

|

Corruption Observers contend that Russia suffers from high levels of corruption. The U.S. State Department's 2016 Human Rights Report notes that corruption in Russia is "widespread throughout the executive branch ... as well as in the legislative and judicial branches at all levels of government. Its manifestations [include] bribery of officials, misuse of budgetary resources, theft of government property, kickbacks in the procurement process, extortion, and improper use of [one's] official position to secure personal profits." Transparency International (TI), a nongovernmental organization (NGO), ranks Russia 131 out of 176 countries on its 2016 Corruption Perception Index, similar to Kazakhstan, Iran, Nepal, and Ukraine (though Russia's TI ranking has improved over time; in 2010, the country ranked 154 out of 178). Many Russians share these perceptions of corruption. In a February 2016 poll by the Russia-based Levada Center, 76% of respondents said that Russian state organs were either significantly or wholly affected by corruption. Of respondents who engaged in activities such as vehicle registration and licensing, hospital stays, university admissions, and funerals, 15%-30% reported having paid a bribe (as did nearly half of those who reported being detained by traffic police). Estimates of bribe amounts vary. In December 2015, Russia's Ministry of Internal Affairs reported that the average amount of a bribe in criminal cases was around $2,500. In September 2016, a domestic NGO, Clean Hands, calculated the average reported bribe to be around five times that amount. Government officials are occasionally arrested for bribery or compelled to resign from their posts. In 2016, cases included a regional governor who was once an opposition figure, the mayor of Russia's Pacific port city Vladivostok, an Interior Ministry anticorruption official, and the head of the Federal Customs Service. Although observers often presume there may be grounds for arrest or dismissal, these cases tend not to be interpreted as elements of a serious anticorruption campaign but rather as manifestations of political and economic infighting or as a way to remove ineffective or troublesome politicians. Few of Russia's most senior officials are arrested or dismissed for corruption. On the contrary, many observers, including within the U.S. government, believe that Putin and several of his closest colleagues have amassed considerable wealth while in power. In a January 2016 interview, then-Acting Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Adam Szubin said that "We've seen [President Putin] enriching his friends, his close allies and marginalizing those who he doesn't view as friends using state assets." Szubin also noted that Putin "supposedly draws a state salary of something like $110,000 a year. That is not an accurate statement of the man's wealth, and he has longtime training and practices in terms of how to mask his actual wealth." Russian government officials reject all such claims. Sources: U.S. Department of State, Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2016: Russia; Transparency International, "Corruption Perceptions Index 2016"; Levada Center, "Impressions about the Scale of Corruption and Personal Experience," April 6, 2016 (in Russian); Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation, "Today—the International Anti-Corruption Day," December 9, 2015; Association of Russian Lawyers for Human Rights, Corruption in Russia: An Independent Annual Report of the All-Russian Anticorruption Social Organization Clean Hands, September 21, 2016; BBC News, "Russia BBC Panorama: Kremlin Demands 'Putin Corruption' Proof," January 26, 2016. |

Government Reshuffles

Many observers agree that Vladimir Putin is the most powerful person in Russia. However, Putin does not rule alone. For most of his tenure, he has presided over a complex network of officials and business leaders, many of whom are individuals Putin knew from his time in the Soviet KGB or when he worked in the St. Petersburg local government in the early 1990s.18 An influential leadership circle below Putin includes government officials, heads of strategic state-owned enterprises, and businesspersons. Since 2012, the Russian-based Minchenko Consulting group has produced a series of well-regarded studies that assess who, besides Putin, are the most influential figures in the Russian policymaking process.19 This list specifies 8 to 10 individuals who wield the greatest influence (see "Key Russian Officials Under Putin" text box), including some who do not hold official positions, as well as around 50 other key individuals in the security, political, economic, and administrative spheres.

|

Key Russian Officials Under Putin Alexander Bortnikov: Director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) Sergei Chemezov: Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Rostec (hi-tech and defense state corporation) Sergei Lavrov: Foreign Minister Dmitry Medvedev: Prime Minister Nikolay Patrushev: Secretary of the Security Council Igor Sechin: CEO of Rosneft (state oil company) Sergei Shoigu: Minister of Defense Sergei Sobyanin: Mayor of Moscow Vyacheslav Volodin: Chair of Parliament Viktor Zolotov: Director of the National Guard Notes: Chemezov, Medvedev, Patrushev, Sechin, Shoigu, and Sobyanin are listed by Minchenko Consulting (see footnote 19) as among Russia's eight most influential policymakers under Putin, together with businessmen Yuri Kovalchuk and Arkady Rotenberg. |

Observers have noted some recent changes to this system of governance.20 The first change is a reduction in influence of several of Putin's longtime senior associates, including Putin's former chief of staff (and former minister of defense), Sergei Ivanov, who was once pegged as a possible successor to Putin. Since 2014, four senior officials close to Putin have retired, and Ivanov and at least one other appear to have been demoted (see "Resignations or Demotions of Longtime Putin Colleagues" text box).

A related change is a steady rise in the number of senior officials who are at least a decade younger than Putin (aged 64) and have risen as Putin's subordinates more than as his colleagues. Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (aged 51) straddles this divide; he has worked with Putin since St. Petersburg and was Putin's handpicked successor to the presidency (2008-2012) after Putin's first two terms. Others have served Putin or Medvedev for several years and have gained relatively powerful positions.

|

Resignations or Demotions of Longtime Putin Colleagues Vladimir Kozhin: Head of the Presidential Administrative Directorate (demoted May 2014) Vladimir Yakunin: Head of the Russian Railways (resigned August 2015) Viktor Ivanov: Head of the Federal Drug Control Service (retired May 2016; service dissolved) General Yevgeny Murov: Head of the Federal Guard Service (a more powerful version of the U.S. Federal Protective Service and Secret Service) (retired May 2016) Andrei Belyaninov: Head of the Federal Customs Service (resigned July 2016) Sergei Ivanov: Presidential Chief of Staff (and former minister of defense) (demoted August 2016) Note: Kozhin, Yakunin, V. Ivanov, Murov, and S. Ivanov are subject to U.S. Ukraine-related sanctions. |

Several other younger officials have emerged recently. They are generally seen as having no real power bases of their own and as entirely loyal to Putin. Some are bureaucrats who have replaced Putin's retiring colleagues. Observers also have noted the rapid rise of at least three younger officials who started their careers as members of the presidential security service (i.e., Putin's bodyguards) and have gone on to serve as regional governors; one is currently a deputy head of the Federal Security Service (FSB).21

In assessing the impact of these changes, a few considerations may be useful to keep in mind. First, there does not appear to be a single explanation for the declining influence of Putin's longtime colleagues. The most common factors that observers suggest are declining efficiency or increasing mismanagement.22 However, these factors are not evident in every case. Moreover, when they are relevant, the reasons behind them have varied, including corruption, age, and even bereavement (Sergei Ivanov recently lost his son to a drowning accident).

Second, the changes do not yet amount to a total turnover. Several of Putin's other longtime colleagues remain in positions of considerable power or influence (see "Longtime Putin Colleagues Still in Power" text box).

Third, this gradual "changing of the guard" is occurring against the backdrop of what observers characterize as frequently vicious struggles for wealth and influence among different power centers, but most often between the FSB (in particular, its Interior Security Department) and others: the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Investigative Committee (a kind of Federal Bureau of Investigation), Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov, and a more liberal (i.e., economically oriented) wing of the Russian government.23 Considerable speculation has occurred that such rivalries on occasion lead to developments that Putin does not control. Potential examples include the February 2015 murder of opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, which was blamed on people close to Kadyrov, and the November 2016 arrest of Minister of Economic Development Alexey Ulyukaev, which observers suspect is linked to a rivalry with Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin, considered one of Russia's most influential policymakers.24

|

Longtime Putin Colleagues Still in Power Sergei Chemezov: CEO of Rostec, Russia's large state-owned military-industrial complex, who oversees scores of hi-tech and defense companies across the country. Nikolay Patrushev: Chair of the National Security Council. Colleagues reportedly have referred to Patrushev as "Russia's most underestimated public figure." He is thought to have had considerable influence in shaping Russia's recent anti-Western foreign policy trajectory, including the annexation of Crimea. Igor Sechin: CEO of Rosneft. Sechin has long been considered one of the most powerful officials in Russia, with not only influence over the state-owned oil sector but also unofficial ties to elements of the FSB. Last year, Sechin was subject to some speculation that he risked overstepping his bounds and losing power, but he ultimately appeared to strengthen his position at the expense of various rivals. Viktor Zolotov: Head of the National Guard. Zolotov is considered to be singularly loyal to Putin. He now heads a new security apparatus that officially serves as a special police force to combat terrorism and organized crime but is widely considered to be Putin's "personal army" and, potentially, a repressive tool for fighting civil unrest. Other Longtime Putin Colleagues Still in Power: Andrei Fursenko (Presidential Aide), German Gref (Sberbank), Dmitry Kozak (Deputy Prime Minister), Alexei Kudrin (Vice Chair, Presidential Economic Council), Alexei Miller (Gazprom), Sergei Naryshkin (Foreign Intelligence Service), Yevgeny Shkolov (Presidential Aide), and Nikolai Tokarev (Transneft). Some influential businessmen also are longtime colleagues of Putin: Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, Nikolai Shamalov, and Gennady Timchenko. Notes: Chemezov is subject to U.S. and European Union (EU) Ukraine-related sanctions (as are Kozak, Naryshkin, and A. Rotenberg). Sechin is subject to U.S. Ukraine-related sanctions (as are Fursenko, B. Rotenberg, and Timchenko). Patrushev (and Shamalov) are subject to EU sanctions. In addition, Rostec is subject to U.S. (and, partially, EU) Ukraine-related sanctions and Rosneft is subject to U.S. and EU Ukraine-related sanctions. |

September 2016 State Duma Elections

On September 18, 2016, Russians elected the State Duma, the lower house of parliament. Russia's last parliamentary elections, in December 2011, triggered a wave of protests against electoral fraud and heralded the rise of a revitalized opposition against Putin's government. Five years later, expectations of democratic change at the ballot box had subsided. With a voter turnout of 48%, the ruling United Russia (UR) party won a resounding victory, with more than 75% of the seats (as opposed to 53% in 2011). All other seats went to those considered loyal opposition parties and deputies. No parties genuinely in opposition (sometimes termed the liberal opposition) won any seats (see Table 1).25

|

Party List % |

Party List Seats |

Single-Member Seats |

Total Seats |

% of Seats |

|||||

|

United Russia (UR) |

|

140 |

203 |

343 |

|

||||

|

Communist Party (KPRF)a |

|

35 |

7 |

42 |

|

||||

|

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR)a |

|

34 |

5 |

39 |

|

||||

|

A Just Russiaa |

|

16 |

7 |

23 |

|

||||

|

Other |

|

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

||||

|

Yablokob |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

||||

|

PARNASb |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

||||

|

Total |

|

225 |

225 |

450 |

|

Source: Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation, at http://www.vybory.izbirkom.ru.

Notes: Total party list percentage is calculated out of the total number of valid and invalid ballots.

a. The KPRF, LDPR, and A Just Russia parties are considered the loyal opposition parties. These parties criticize the government, if not Putin, but typically support its legislative initiatives.

b. Yabloko and PARNAS are liberal opposition parties considered to be genuinely in opposition to the government. They fall under the "Other" category, which includes several small parties that did not meet the 5% threshold for party list representation.

The ruling UR party traditionally polls lower than Putin, who does not formally lead the party, but it appeared to benefit from a surge in patriotic sentiment unleashed by Russia's annexation of Crimea, Russia's so-called defense of pro-Russian populations in eastern Ukraine, and appeals for national solidarity in the face of Western sanctions and criticism.26 UR also experienced a certain renewal in advance of elections; party primaries promoted the rise of many candidates new to national politics and eliminated a number of sitting deputies.27

At the same time, the Russian government took measures after the last election to bolster the victory of UR and minimize opposition gains across the country.28 Fourteen parties that received at least 3% of the vote in the last election or held at least one seat in a regional council competed in the 2016 election. Other parties technically could register after collecting 200,000 signatures, but no such registrations were approved. In addition, state-controlled media and government officials subjected opposition leaders to a barrage of negative publicity, branding them as agents of the West.29 Restrictions on mass demonstrations tightened. A centrally controlled redistricting process led to the carving up of urban centers that leaned toward the opposition. Finally, the election date was moved up from December 2016, considerably shortening the campaign period.30

UR also benefited from a change in electoral rules restoring a mixed electoral system that had been in place through 2003 parliamentary elections. UR's financial and administrative resources across the countryside were expected to help the party win more seats via single-member races than it would in a purely proportional contest; indeed, UR candidates won more than 90% of these races.31 By comparison, in the contested 2011 election, when seats were allocated entirely by party-list vote, UR officially won 49% of the vote (as opposed to 54% in 2016) but only 53% of seats (as opposed to 76% in 2016).

Election observers also raised concerns about fraud. The election observation mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) noted that the counting process was bad or very bad in 23% of the polling stations it observed. One widely cited statistical analysis by a Russian scholar also suggested the election was marred in certain areas of the country by high levels of fraud, including ballot-box stuffing.32

Besides UR, the three parties that gained seats have served in parliament already and are known as the loyal opposition. These parties criticize the government, if not Putin, but typically support its legislative initiatives. Two are longtime fixtures of Russian politics: the Communist Party (KPRF, led by Gennadiy Zyuganov) and the right-nationalist Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR, led by Vladimir Zhirinovsky). The third, A Just Russia (led by Sergei Mironov), is a center-left party that flirted with the opposition in 2011-2012 before returning to the fold (and expelling some of its members, who remained in opposition).33

The Opposition

As noted above, no liberal opposition party won Duma seats in the 2016 elections. However, two liberal opposition parties, neither of which was in the previous parliament, were eligible to compete: Yabloko (identified with its former longtime chairman Grigory Yavlinsky) and PARNAS (led by a former prime minister, Mikhail Kasyanov, as well as, previously, Boris Nemtsov, slain in 2015). Both parties consider themselves European-style liberal democratic parties, though other parties criticized PARNAS in 2016 for including at least one populist firebrand near the top of its list.34

In addition, 18 single-member races were contested by candidates representing the Open Russia movement, founded by former oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky.35

The party of another prominent opposition leader, anticorruption activist and 2013 Moscow mayoral candidate Alexei Navalny, had its registration revoked in 2015, ostensibly for technical reasons, and thus was unable to participate in the election. Navalny himself is barred from running for political office due to a 2013 criminal conviction that resulted in a suspended sentence. Navalny supporters and most outside observers deemed the case (and a second one) to be politically motivated, and in February 2016, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) concluded that the trial had violated Navalny's rights.36

Opposition fragmentation was an issue prior to the election. Opposition leaders protected their individual brands and appeared to fear that these brands could be damaged by formal unification with other parties (electoral blocs have been banned since 2005). In 2015, Navalny's Party of Progress had joined with PARNAS and others in a "Democratic Coalition," which was to run candidates under the PARNAS banner. The coalition soon encountered difficulties, however. It was barred from registering candidates in September 2015 regional elections, and in spring 2016 the coalition collapsed after PARNAS leader Kasyanov was targeted in a scandal involving alleged hidden video footage of an affair with a party colleague.37

For now, observers tend to see Vladimir Putin's rule as relatively stable, although new signs of discontent have arisen. Ongoing economic difficulties (see "The Economy," below) have led to small-scale protests across Russia, as prices have risen, salaries have fallen, unemployment has grown, and social spending has been reduced.38 In March and June 2017, nationwide protests spearheaded by Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation reportedly attracted thousands, many of whom were university-aged or younger, to demonstrate against corruption. Hundreds of protestors were temporarily detained, including Navalny, who was fined and sentenced to, respectively, 15 days and 30 days in prison for what the courts cited as illegal activity.39

Whether such protests are sufficient to catalyze a more substantial political movement remains to be seen. Some observers believe that the government is seeking to minimize popular discontent by continuing to increase social benefits in the lead-up to the next presidential election, scheduled for March 2018, even as expenditures in education, health care, and defense stay flat or decline.40

Potential future scenarios tend to center on succession politics, whether engineered by Putin or prompted by his incapacitation or untimely passing. As late as June 2017, Putin still would not say if he was planning to run for reelection, although many observers believe he plans to do so.41 In the event of a controlled succession (in 2018 or after), observers speculate about a number of well-known potential successors. However, the eventual choice also could be a relatively unknown figure; Putin himself was a highly unexpected choice to succeed his predecessor, Boris Yeltsin.

Many observers put little stock in the possibility of a democratic transition of power. In such a scenario, candidates are thought more likely to emerge from right-wing nationalist forces or a new post-Communist left, not from a liberal, pro-Western opposition or civil society, whose influence has been seriously undermined by the Russian government.

Other scenarios involve a loss of control by Putin or members of his inner circle, as a result of a collapsing economy, weakened state apparatus, or an external war gone wrong. Some observers have speculated that rival political centers could compete for power in Putin's absence and that this competition could turn violent. In addition, some have voiced concerns that an uncontrolled transition could lead to the rise of more nationalist forces.

|

Local Elections Formally, Russia has a robust system of subnational elections; in practice, the country's top-down system provides centralized control over key issues. Regional and municipal councils are elected, as are governors of most of Russia's 83 regions and republics (though candidates must secure the signatures of 5%-10% of all their region's municipal deputies, which is seen as a major constraint). Kremlin-backed leaders dominate local government structures. All but one of Russia's 83 governors are United Russia (UR) members or other government-backed figures. In the Siberian region of Irkutsk in September 2015, Communist Party member Sergei Levchenko became the only gubernatorial candidate since elections were reintroduced in 2012 to defeat a government-backed opponent. UR also has majorities, typically substantial ones, in all regional councils; only a handful of regional deputies across the country are affiliated with the liberal opposition. Certain regions and cities contain more opposition-minded voters, most notably the two major urban centers of Moscow and St. Petersburg. In the September 2013 Moscow mayoral election, opposition candidate Alexei Navalny won 27% of the vote (incumbent Sergei Sobyanin, Putin's former chief of staff and deputy prime minister, won 51%). Some regions in Siberia and the Far East, as well as in the Northwest, also elect greater numbers of opposition candidates (including the Communists and other loyal opposition parties). Although Russian law allows for the direct election of mayors in cities other than Moscow and St. Petersburg, most municipalities have an indirectly elected mayor or council head who shares authority with a more powerful appointed or indirectly elected city manager. A few opposition candidates have won competitive mayoral elections, although some of the more prominent were subsequently removed from office and even imprisoned. Sources: J. Paul Goode, "The Revival of Russia's Gubernatorial Elections: Liberalization or Potemkin Reform?," Russian Analytical Digest no. 139 (November 18, 2013), pp. 9-11; Joel C. Moses, "Putin and Russian Subnational Politics in 2014," Demokratizatsiya vol. 23, no. 2 (Spring 2015), pp. 181-203; Maria Tsvetkova, "When Kremlin Candidate Loses Election, Even Voters Are Surprised," Reuters, September 29, 2015; Ola Cichowlas, "Endangered Species: Why Is Russia Locking Up Its Mayors?," Moscow Times, August 2, 2016. |

The Economy42

The Russian economy has gone through periods of decline, growth, and stagnation since 1991. In the first seven years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1992-1998), Russia experienced an average annual decline in gross domestic product (GDP) of 6.8%. A decade of strong economic growth followed, in which Russia's GDP increased on average 6.9% per year. The surge in economic growth—largely the result of increases in world oil prices—helped to raise the Russian standard of living and brought a significant degree of economic stability.

The Russian economy was hit hard by the global financial crisis and resulting economic downturn that began in 2008. The crisis exposed weaknesses in the economy, including its significant dependence on the production and export of oil and other natural resources and its weak financial system. The Russian government's reassertion of control over major industries, especially in the energy sector, also contributed to an underachieving economy. As a result, Russia's period of economic growth came to an abrupt end by 2009. Although Russian real GDP increased 5.2% in 2008, it declined by 7.8% in 2009. Russia began to emerge from its recession in 2010, with 4.5% GDP growth that year, but by 2013 growth had again slowed to 1.3%.43

Since 2014, two external shocks—low oil prices and international sanctions—have contributed to considerable economic challenges. In particular, Russia has grappled with the following:

- economic contraction, with growth slowing to 0.7% in 2014 before contracting by 2.8% in 2015;

- capital flight, with net private capital outflows from Russia totaling $152 billion in 2014, compared to $60 billion in 2013;

- rapid depreciation of the ruble, more than 50% against the dollar over the course of 2014;

- increasing inflation, from 6.8% in 2013 to 15.5% in 2015;

- declining trade, with the dollar value of exports and imports down by 31% and 36%, respectively, from 2014 to 2015;

- budgetary pressures, with the budget deficit widening from 1.2% in 2013 to 3.4% in 2015;

- drawing on international reserves to offset fiscal challenges, with reserves falling from almost $500 billion in January 2014 to $356 billion in April 2015; and

- more widespread poverty, which increased from 16.1 million living in poverty in 2014 to 19.2 million in 2015 (13.4% of the population).44

During 2016, Russia's economy largely stabilized, even as sanctions remained in place. Russia's economy only slightly contracted (0.2%); net private sector capital outflows slowed, from more than $150 billion in 2014 to $19.8 billion in 2016; inflation fell by more than half since 2015, to 7.0%; the value of the ruble stabilized; reserves began to rise; and the government successfully sold new bonds in international capital markets in May 2016. Around 19.8 million (13.5% of the population) were estimated to be living in poverty.45 Net inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) into Russia, which essentially came to a halt in late 2014 and early 2015, started to resume in 2016. Most notably, a consortium of the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA, Qatar's national sovereign wealth fund) and Glencore, a Swiss-based mining and commodity trading firm, purchased 19.5% of the state-controlled Rosneft, Russia's largest oil company, for €10.2 billion (about $10.6 billion at the time).46

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Russia's economy is projected to grow by 1.4% in 2017.47 The IMF argues that after two years of recession, the economy is recovering due to a rise in oil prices and improved investor sentiment but that the medium-term prospects are subdued given oil prices still well below their peak and structural weaknesses in Russia's economy.48 Low oil prices also have strained the government budget, which ran a deficit of 3.7% of GDP in 2016, but the fiscal outlook has improved as oil prices have stabilized, with a budget deficit of 1.9% of GDP projected for 2017.49 The government has tapped one of Russia's sovereign wealth funds, the Reserve Fund, to address the budget shortfall, and its resources have fallen to about $16 billion from $143 billion in 2008.50 The government is considering consolidating its two sovereign wealth funds as the government continues to face budget shortfalls. Russia's other sovereign wealth fund, the National Wealth Fund, was designed to help balance the pension system and has about $75 billion.51

In the longer term, Russia's economy faces long-standing structural challenges, including slow economic diversification, weak protection of property rights, burdensome administrative procedures, state involvement in the economy, and adverse demographic dynamics.52 The IMF argues that sanctions dampen the potential for accelerating investment growth.53 Some analysts also have noted that the low value of the ruble may hamper Russia's attempts to innovate and modernize its economy and that the economy's continued reliance on oil makes it vulnerable to another drop in oil prices.54

Despite Western sanctions and Russia's own retaliatory ban against agricultural imports, the EU as a whole remains Russia's largest trading partner. In 2016, 47% of Russia's merchandise exports went to EU member states and 38% of its merchandise imports came from EU member states. By country, Russia's top three merchandise export destinations were the Netherlands (10%), China (10%), and Germany (7%), and its top three sources of merchandise imports were China (21%), Germany (11%), and the United States (6%).55

Economic Impact of Sanctions

It is difficult to assess whether, and to what extent, sanctions on Russia and Russia's retaliatory measures have impacted the country's economy over the past few years (for details on U.S. sanctions against Russia, see "Ukraine-Related Sanctions," below). Sanctions were imposed at the same time the price of oil, a major export and source of revenue for the Russian government, dropped significantly, by more than 60% between the start of 2014 and the end of 2015.56

That said, many economists, including at the IMF, have argued that the twin shocks of sanctions and low oil prices have adversely affected Russia's economy.57 In 2015, the IMF estimated that sanctions and Russia's retaliatory ban on agricultural imports reduced output in Russia over the short term between 1.0% and 1.5%.58 The IMF's models suggest that the effects on Russia over the medium term could be more substantial, reducing output by up to 9.0%, as lower capital accumulation and technological transfers weaken already declining productivity growth. At the start of 2016, a State Department official argued that sanctions were not designed to push Russia "over the economic cliff" in the short run but rather were designed to exert long-term pressure on Russia.59

In November 2014, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov estimated the annual cost of sanctions to the Russian economy at $40 billion (2% of GDP), compared to $90 billion-$100 billion (4%-5% of GDP) lost due to lower oil prices.60 Similarly, Russian economists estimated that the economic sanctions would decrease Russia's GDP by 2.4% by 2017, but the effect would be 3.3 times less than the effect from the oil-price shock.61 In November 2016, Putin stated that the sanctions are "severely harming Russia" in terms of access to international financial markets, although the impact was not as severe as the harm from the decline in energy prices.62

In December 2016, the Office of the Chief Economist at the U.S. State Department published estimates of the impact of the U.S. and European Union (EU) sanctions in 2014 on a firm-level basis.63 The main finding was that the average company or associated company in Russia subject to sanctions lost about one-third of its operating revenue, more than one-half of its asset value, and about one-third of its employees relative to nonsanctioned peers.

The longer-term effect of sanctions, if they are kept in place, is unclear. The economic bite of restrictions on U.S. long-term financing for certain sectors or technology for specific Russian oil exploration projects may manifest more prominently in coming years. At the same time, the long-term impact may depend on whether Russia can develop viable and reliable alternative economic partners, particularly among countries that have refrained from sanctions (such as China, India, and Brazil), to fulfill economic activities restricted by U.S. and EU sanctions.

U.S.-Russian Trade and Investment

Even before sanctions were imposed, the United States had relatively little direct trade and investment with Russia. Over the past decade, Russia has accounted for less than 2% of total U.S. merchandise imports, less than 1% of total U.S. merchandise exports, less than 1% of U.S. FDI, and less than 1% of FDI in the United States.64 At the same time, in 2016, the United States was Russia's third-largest source of merchandise imports (and 10th-largest destination for exports).

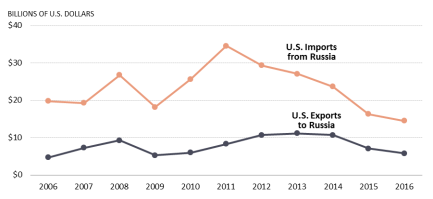

Over the past three years, U.S. merchandise trade with Russia has fallen by almost half (see Figure 2). U.S. merchandise exports to Russia fell from $11.1 billion in 2013 to $5.8 billion in 2016. U.S. merchandise imports from Russia fell from $27.1 billion in 2013 to $14.5 billion in 2016. U.S. investment ties with Russia also continued to weaken. U.S. investment in Russia was $9.2 billion in 2015, down from a peak of $20.8 billion in 2009.65 Russian investment in the United States was $4.5 billion, down from a peak of $8.4 billion in 2009.

U.S. merchandise imports from Russia tend to be dominated by oil and unfinished metals. Of the $14.5 billion in merchandise that the United States imported from Russia in 2016, about half was mineral fuels and oils ($7.2 billion), particularly noncrude oil ($6.6 billion). Other top U.S. merchandise imports from Russia in 2016 included aluminum ($1.33 billion); iron and steel ($1.3 billion); inorganic chemicals, precious and rare-earth metals and radioactive compounds ($1.2 billion), particularly enriched uranium ($1.03 billion); precious metals, stones, and related products ($696 million), particularly unfinished platinum ($607 million); fertilizers ($502 million); and fish, crustaceans, and aquatic invertebrates ($410 million). These products accounted for more than 85% of U.S. imports from Russia in 2016.

U.S. merchandise exports to Russia tend to focus on machinery and manufactured products. Of the $5.8 billion in commodities exported by the United States to Russia in 2016, the top export was nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery, and parts ($1.4 billion). Other top U.S. merchandise exports to Russia in 2016 included aircraft, spacecraft, and related parts ($1.3 billion); vehicles and parts ($617 million); optic, photo, medic, and surgical instruments ($438 million); electric machinery and sound equipment ($421 million); and pharmaceutical products ($190 million). These products accounted for more than 75% of U.S. exports to Russia in 2016.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using U.S. Census Bureau data, as accessed from Global Trade Atlas. |

Even though overall trade and investment flows between the United States and Russia are limited, economic ties at the firm and sector levels are in some cases substantial. Several large U.S. companies, such as PepsiCo, Ford Motor Company, General Electric, and Boeing, have been actively engaged with Russia: exporting to Russia, entering joint ventures with Russian partners, and relying on Russian suppliers for inputs. The U.S.-Russia Business Council, a Washington-based trade association that provides services to U.S. and Russian member companies, has a membership of around 170 U.S. companies conducting business in Russia.66

In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), and Congress passed and the President signed legislation that allowed the President to extend permanent normal trade relations to Russia (P.L. 112-208). Part of this legislation requires the U.S. Trade Representative to report annually on the implementation and enforcement of Russia's WTO commitments. The 2016 report stresses that although Russia acted as a responsible member of the WTO community in some areas, such as reducing bound tariffs (maximum rates allowed by the WTO between trading states) by the required deadline, other areas were more problematic: Russia's actions continued to depart from the WTO's core tenets of liberal trade, transparency, and predictability in favor of inward-looking, import-substitution economic policies.67 Separately, some analysts have raised questions about whether Russia's retaliatory ban on agriculture imports from the United States and other countries is compliant with its obligations under the WTO, whereas others argue that the ban may be permitted under the national security exemption. To date, no state has formally challenged the ban at the WTO.

Energy Sector68

Russia is a significant producer of energy in various forms, including crude oil, natural gas, coal, and nuclear power. In 2016, Russia was the third-largest oil producer, behind the United States and Saudi Arabia; the second-largest natural gas producer, behind the United States; and the sixth-largest coal producer. It is also a significant exporter of oil and the largest natural gas exporter, the latter providing Russia with market power, which it has exploited for geopolitical purposes. Natural gas is more of a regional commodity than oil because natural gas requires expensive infrastructure for transport. (Oil, by contrast, is a global market in which Russia does not have the same type of leverage over countries as it does with its natural gas exports.)

Table 2, below, provides data for all countries in Europe that received Russian natural gas (EU members are in bold) in 2015, the latest year for which data are available.69 Seven EU countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Romania, and Slovenia) relied on Russia for 100% of their natural gas imports in 2015, as did five non-EU countries (Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Moldova, and Serbia). Russian gas imports made up more than half the total gas consumption in 20 countries. However, only three EU countries (Hungary, Latvia, and Lithuania) and three non-EU countries (Armenia, Belarus, and Moldova) depended on Russian gas for more than 20% of their total primary energy consumption.

To maintain its leverage and position as Europe's dominant gas supplier, Russia has sought to develop multiple pipeline routes to reduce its dependence on transit states such as Ukraine and to satisfy regional markets. To the north, the Nord Stream pipeline runs under the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany; Russia's state-controlled natural gas company, Gazprom, is seeking to build a second, parallel pipeline, Nord Stream 2, with the financial support of five European energy companies. However, the project still must receive approval from the governments of Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, whose waters it would cross. The European Union (specifically, the EU's executive branch, the European Commission) also is considering whether and to what extent the proposed pipeline would be subject to existing EU regulations.

Opponents of the pipeline—including, among others, the governments of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, and many Members of the U.S. Congress—argue that the pipeline runs counter to the stated EU goal of diversifying European energy supply sources by increasing reliance on Russian gas. In addition, they contend that by bypassing existing pipelines to Eastern Europe through Ukraine, Nord Stream 2 could leave Ukraine and other countries in Central and Eastern Europe more vulnerable to supply cutoffs or price manipulation by Russia.

To the south, Russia had long planned the South Stream pipeline that would have run under the Black Sea to Bulgaria. That project was canceled at the end of 2014. Despite initial skepticism and a temporary decline in Turkish-Russian relations, however, the planned South Stream pipeline has been replaced to an extent by the Turk Stream project, which follows a similar route across the Black Sea but stops at the Turkish-Greek border. Gazprom has signed some contracts for the project, including one for the laying of pipe.

|

Country |

Russian Imports as % of Total Imports |

Russian Imports as % of Total Gas Consumption |

Russian Imports as % of Primary Energy Consumption |

|

Armenia |

83% |

83% |

40% |

|

Austria |

68% |

57% |

11% |

|

Belarus |

100% |

100% |

66% |

|

Belgium |

30% |

58% |

17% |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

100% |

100% |

3% |

|

Bulgaria |

100% |

97% |

14% |

|

Czech Republic |

48% |

47% |

9% |

|

Denmark |

53% |

21% |

3% |

|

Estonia |

100% |

100% |

19% |

|

Finland |

100% |

100% |

9% |

|

France |

20% |

22% |

3% |

|

Georgia |

15% |

15% |

4% |

|

Germany |

41% |

50% |

12% |

|

Greece |

61% |

61% |

6% |

|

Hungary |

100% |

81% |

23% |

|

Italy |

38% |

34% |

14% |

|

Latvia |

100% |

100% |

30% |

|

Lithuania |

84% |

84% |

37% |

|

Macedonia |

100% |

100% |

2% |

|

Moldova |

100% |

100% |

68% |

|

Netherlands |

8% |

6% |

2% |

|

Poland |

77% |

56% |

8% |

|

Romania |

100% |

2% |

0% |

|

Serbia |

100% |

72% |

9% |

|

Slovakia |

90% |

88% |

20% |

|

Slovenia |

100% |

100% |

6% |

|

Switzerland |

8% |

8% |

1% |

|

Turkey |

54% |

54% |

17% |

|

Ukraine |

44% |

21% |

8% |

Sources: CRS, on the basis of data from Cedigaz (http://www.cedigaz.org), industry data provider, 2015; British Petroleum (BP), Statistical Review of World Energy 2016, at http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html; and U.S. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Outlook 2016, at http://www.eia.gov/outlooks/ieo.

Notes: European Union member states are in bold.

Foreign Relations

In recent years, many Members of Congress and other U.S. policymakers have paid growing attention to Russia's active and increasingly forceful foreign policy, both toward neighboring states, such as Georgia and Ukraine, and in regard to operations further afield, such as the intervention in Syria and interference in political processes in Europe and the United States. These actions have even resurrected talk of a new Cold War.70

Although Russian foreign policy has been increasingly active, observers note that the principles guiding it have been largely consistent since the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991. One principle is to reestablish Russia as the center of political gravity for the post-Soviet region and to minimize the military and political influence of rival powers, particularly NATO and more recently the EU. A second principle is to establish Russia as one of a handful of dominant poles in global politics, capable in particular of competing (and, where necessary, cooperating) with the United States.

Beyond these fundamentals, debates exist on a number of related issues. Such issues include whether strong responses by outside powers can deter Russian aggression or whether these responses run a risk of escalating conflict; how much states that disagree with Russia on key issues can cooperate with Moscow; whether the Russian government is primarily implementing a strategic vision or reacting to circumstances and the actions of others; and the extent to which the Russian leadership takes actions abroad to strengthen its domestic position.

Russia and Other Post-Soviet States

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, one fundamental goal of Russian foreign policy has been to retain and, where necessary, rebuild close ties with neighboring states that were once part of the USSR. Many observers inside and outside Russia interpret this policy as laying claim to a traditional sphere of influence. Although Russian policymakers avoid reference to a sphere of influence, they have used comparable terms at various times. In the early 1990s, Russia's foreign minister and other officials employed the term near abroad to describe Russia's post-Soviet neighbors, and in 2008 President (and current Prime Minister) Dmitry Medvedev referred to Russia's neighbors as constituting a "region" where Russia has "privileged interests."71

The original mechanism for reintegrating the post-Soviet states was the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which was established by the Presidents of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine in December 1991. The CIS includes as members or participants all post-Soviet states except the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, all now NATO and EU members) and Georgia.72 The organization has had limited success in promoting regional integration, however.

Russia has had relatively more success developing multilateral relations with a narrower circle of states. In recent years, Russia has mainly accomplished this aim via two institutions: the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a security alliance that includes Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), an evolving single market that includes all CSTO members except Tajikistan (a prospective candidate).73

Current members of these organizations mostly have joined voluntarily, if not always enthusiastically.74 Their goals in joining have been diverse. Although these aims could include the facilitation of trade and investment, as well as protection against a variety of external threats (including terrorism and drug trafficking), they also may include a desire to accommodate Russia, ensure opportunities for labor migration, promote intergovernmental subsidies, and bolster regime security.

Russia dominates both the CSTO and the EEU. It has around 75% of the EEU's total population, approximately 85% of EEU members' total GDP, and more than 95% of CSTO members' military expenditures.75 Russia maintains active bilateral economic, security, and political relations with CSTO and EEU member states, and observers often consider these bilateral ties to be of greater significance than Russia's multilateral relations within these two institutions. Russia's main military facilities in CSTO member states consist of bases in Tajikistan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan and radar stations in Belarus and Kazakhstan.

Russia's relations with its CSTO and EEU partners are not always smooth. In addition to expressing differences over the principles and rules of the two institutions, Russia's closest partners have been reluctant to bind themselves entirely to Russia on matters of foreign policy and economic development. None of them followed Russia's lead in recognizing Georgia's breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states in 2008. Russia secured relatively greater support from partners in its annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region. In March 2014, Armenia and Belarus voted with Russia (and eight other states) to reject United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 68/262, which affirmed Ukraine's territorial integrity. In December 2016, Armenia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan voted with Russia (and 19 other states) to reject UNGA Resolution 71/205, which "condemn[ed] the temporary occupation" of Crimea and reaffirmed nonrecognition of its annexation.76

Russia's partners also have cultivated strong ties with other countries. Kazakhstan, in particular, has developed strong relations with China and the West, particularly in the energy sector. China is the largest trading partner of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Although Armenia and Belarus have close bilateral relations with Russia in the security and economic spheres, they also have established economic ties to Europe, and Belarus's authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko periodically criticizes Russia for what he considers unfair bilateral trading practices and strong-arm diplomacy. Both Armenia and Kazakhstan have established institutional partnerships with NATO; Armenia is a troop contributor to the NATO-led Kosovo Force and Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan. For more than 13 years, Kyrgyzstan hosted a major military base and transit center for coalition troops fighting in Afghanistan.

Russia also has partnerships with three post-Soviet states that are not members of the CSTO or the EEU: Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. These three states have opted to pursue independent foreign policies and do not seek membership in Russian-led or other security and economic blocs.77 Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are significant energy producers; they partner with Russia but also have developed major alternative transit routes for oil (in Azerbaijan's case) and natural gas. In addition, Russia has cultivated a partnership with Uzbekistan, although the latter competes with Kazakhstan for regional leadership in Central Asia and has long-standing disputes with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

Russia's relations with Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine have been the most difficult. These three states have sought to cultivate close ties with the West. Georgia has consistently pursued NATO membership and served as one of NATO's closest nonallied partners in Iraq and Afghanistan. Moldova and Ukraine are also close NATO partners.78 All three states have concluded association agreements with the EU that include the establishment of free-trade areas and encourage harmonization with EU laws and regulations.

Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine also have territorial conflicts with Russia, which stations military forces within these states' territories without their consent (see Figure 4, below). Since the first years of independence, Georgia and Moldova have confronted separatist regions supported by Moscow (in Georgia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia; in Moldova, Transnistria). Following a steady worsening of relations with Georgia, together with increasing clashes between Georgian and separatist forces, Russia went to war with Georgia in August 2008 to prevent Georgia from reestablishing control over South Ossetia. The war resulted in the expulsion of Georgian residents and the destruction of their villages, as well as Russian recognition of the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russia has periodically imposed embargoes on key imports from Georgia and Moldova, although both states have managed to partially normalize relations with Russia. Moldova's current president, Igor Dodon, seeks to reorient Moldova closer to Russia, although his formal powers to do so are relatively limited in Moldova's political system.

Ukraine Conflict79

|

Summary of Minsk-2 Provisions 1. Immediate and full bilateral cease-fire. 2. Withdrawal of all heavy weapons by both sides. 3. Effective international monitoring regime. 4. Dialogue on (a) modalities of local elections in accordance with Ukrainian legislation and (b) the future status of certain districts in Donetsk and Luhansk. 5. Pardon and amnesty via a law forbidding persecution and punishment of persons involved in the conflict. 6. Release of all hostages and other illegally detained people based on a principle of "all for all." 7. Safe delivery of humanitarian aid to those in need, based on an international mechanism. 8. Restoration of full social and economic links with affected areas. 9. Restoration of full Ukrainian control over its border with Russia alongside the conflict zone, beginning from the first day after local elections and ending after the introduction of a new constitution and permanent legislation on the special status of districts in Donetsk and Luhansk. 10. Withdrawal of all foreign armed groups, weapons, and mercenaries from Ukrainian territory and disarmament of all illegal groups. 11. Constitutional reform in Ukraine, including decentralization and permanent legislation on the special status of districts in Donetsk and Luhansk. 12. Local elections in districts of Donetsk and Luhansk, to be agreed upon with representatives of those districts and held according to OSCE standards. 13. Intensification of the work of the Trilateral Contact Group (Ukraine, Russia, OSCE), including through working groups on implementation of the Minsk agreements. |

Many observers consider that of all the post-Soviet states, Ukraine has been the most difficult for Russia to accept as fully independent.80 Even before 2014, the Russian-Ukrainian relationship suffered turbulence, with disputes over Ukraine's ties to NATO and the EU, the status of Russia's Crimea-based Black Sea Fleet, and the transit of Russian natural gas via Ukraine to Europe. Under Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych (2010-2014), such disputes were largely papered over. By the end of 2013, Yanukovych appeared to make a decisive move toward Russia, postponing the conclusion of an association agreement with the EU and agreeing to substantial financial assistance from Moscow.

The decision to postpone Ukraine's agreement with the EU was a catalyst for the so-called Euromaidan protests, which led to a government crackdown on demonstrators, violent clashes between protestors and government forces, and eventually the demise of the Yanukovych regime. Ukraine's armed conflict with Russia emerged soon after Yanukovych fled to Russia in February 2014. Moscow annexed Crimea the next month and facilitated the rise of new separatist movements in eastern Ukraine (the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, together known as the Donbas, see Figure 3). In late August 2014, Russia stepped up support to separatists in reaction to a new Ukrainian offensive.

In September 2014, the leaders of France, Germany, Russia, and Ukraine, together with separatist representatives, negotiated a cease-fire agreement, the Minsk Protocol (named after the city where it was reached). However, the protocol failed to end fighting or prompt a political resolution to the crisis.

The parties met again in February 2015 and reached a more detailed cease-fire agreement known as Minsk-2. This agreement mandates a total cease-fire, the withdrawal of heavy weapons and foreign troops and fighters, and full Ukrainian control over its border with Russia, among other provisions (see "Summary of Minsk-2 Provisions" box).

|

|

Sources: Graphic produced by CRS. Map information generated by [author name scrubbed] using data from the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (2016), the Department of State (2015), and geographic data companies Esri (2014) and DeLorme (2014). |

To date, most observers perceive that little has been achieved in implementing the provisions of Minsk-2, despite commitments made by all sides. Although the conflict's intensity has subsided at various times, a new round of serious fighting arose at the end of January 2017 and lasted for several days. As of mid-May 2017, the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights estimated that the conflict had led to at least 10,090 combat and civilian fatalities.81

Moscow officially denies Russia's involvement in the conflict outside of Crimea, where there are an estimated 28,000-29,000 Russian troops; most observers agree, however, that Russia has unofficially deployed troops to fight, helped recruit Russian "volunteers," and supplied Donbas separatists with weapons and armed vehicles.82 Estimates of the number of Russian troops in eastern Ukraine have declined since their height in 2015.83 In March 2017 testimony to a Senate Appropriations Subcommittee, Ukrainian Minister of Foreign Affairs Pavlo Klimkin said that there were now about 4,200 Russian troops in the region (together with around 40,000 militants, presumably a combination of local and Russian fighters).84

NATO-Russia Relations85

The Ukraine conflict has heightened long-standing tensions between NATO and Russia. Three days after Russia's annexation of Crimea, then-NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen declared that NATO could "no longer do business as usual with Russia."86 Accordingly, Russian actions in Ukraine resulted in a series of actions by NATO and its members intended to counter Moscow and to reassure Central and Eastern European allies that NATO will protect them against potential future acts of Russian aggression.

Even before the Ukraine conflict, post-Cold War efforts to build a cooperative NATO-Russia partnership had at best mixed results. Allies sought to assure a suspicious and skeptical Russia that NATO did not pose a security threat or seek to exclude Russia from Europe. The principal institutional mechanism for NATO-Russia relations is the NATO-Russia Council (NRC), which was established in May 2002, five years after the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act provided the formal basis for bilateral cooperation. Recognizing that NATO and Russia face many of the same global challenges and share similar strategic priorities, Russian and NATO leaders structured the NRC as a forum of equal member states, with goals that included political dialogue on security issues, the determination of common approaches, and the conduct of joint operations.87 Formal meetings of the NRC were suspended in April 2014 and resumed in 2016.