Northeast Asia and Russia’s “Turn to the East”: Implications for U.S. Interests

Since Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and its annexation of the Crimea in March 2014, Moscow’s already tense relationship with the United States and Europe has grown more fraught. After the imposition of sanctions on Russia by much of the West, Russian President Vladimir Putin has turned to East Asia, seeking new partnerships to counter diplomatic isolation and secure new markets to help Russia’s struggling economy. His outreach to Beijing, Tokyo, Seoul, and Pyongyang has met varying degrees of success. The most high-profile outreach was a summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping in May 2014, when the leaders announced dozens of economic cooperation agreements. Putin has met with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe over a dozen times in an effort to resolve a territorial dispute and improve bilateral relations. Putin has also reached out to both Koreas in his bid to step up engagement with Northeast Asian countries.

Russian engagement in Northeast Asia challenges the U.S. strategic presence in the region in a number of ways and represents a new arena of potential concern for Congress. If Moscow’s engagement efforts succeed, it could undermine U.S. efforts to impose sanctions on Russia and isolate Putin diplomatically for his intervention in Ukraine. It could also create mistrust between the United States and its allies Japan and South Korea if those countries’ leaders are drawn closer to Russia. Diplomatic initiatives in the region to deal with the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs could suffer if Moscow disrupts international efforts to rein in North Korean provocations. Perhaps most importantly, China and Russia could form a regional bloc whose primary purpose could be to reduce U.S. economic leverage and challenge the U.S. security presence in the region.

The Chinese-Russian relationship is driven in large part by the perceived threat of the U.S. rebalance to Asia and their shared perspective of American unilateralism. Concrete progress on bilateral projects, however, is marked by inconsistency and faltering implementation of agreements. With Russia’s economy devastated by falling energy prices since 2014, China appears to view Russia as a junior partner. Although Russia-China military relations have increased rapidly, so too has an element of competition, particularly in the Arctic region. Chinese firms are wary of investing in Russia, seeing it as politically risky and commercially unattractive. In multilateral fora like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and new Silk Road initiatives, China wants to expand its economic clout while Russia looks to assert its military dominance in Central Asia. These tensions may prevent a full-fledged strategic partnership, but relations continue to grow stronger through regular bilateral summits and global cooperation.

Japan appears enthusiastic about improving relations with Russia and resolving their territorial dispute over four islands at the northern edge of Japan. Even as U.S.-Japan security links grow stronger, Abe continues to respond to Putin’s overtures with an eye on balancing China. Russia’s economic engagement of Pyongyang has chilled since the Kim regime resumed testing nuclear weapons and missiles. The stalemate in inter-Korean relations and the abandonment of cross-border projects also limit Russia’s potential role in facilitating infrastructure and trade links on the Peninsula. Seoul’s increasingly close U.S. alliance contracts the space for Moscow’s diplomatic maneuver.

Japan, South Korea, and China all have interest in Russia’s supply of oil and gas from its resource-rich Far East. Although several partnerships already exist, dealing with Russia’s government-controlled energy companies has proved difficult. Private firms are reluctant to invest in a politically risky environment, and the availability of cheap energy from elsewhere has dampened commercial enthusiasm for investing heavily in Russia’s energy industry.

Despite obstacles, Russia’s pursuit of better relations with countries in East Asia remains a complicating and potentially destabilizing factor for the U.S. policy of rebalancing its security and economic interests to the region. Russia could become a larger factor for Congress to consider when assessing progress on the rebalance to Asia strategy. Russia’s “Turn to the East” could also affect areas of congressional concern such as the efficacy of U.S. sanctions policy, U.S. North Korean policy, U.S. strategy in the Arctic region, U.S. priorities at the United Nations, and global energy politics.

Northeast Asia and Russia's "Turn to the East": Implications for U.S. Interests

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Possible Implications for U.S. Interests

- Potential for a China-Russia Bloc

- Possible Challenges to U.S. Alliances

- Impact on U.S. Strategy Toward North Korea

- China-Russia Relations

- A Relationship of Convenience or a True Alliance?

- Security Relations

- Cooperation at the United Nations

- Competition and Cooperation in Regional Fora

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)

- Japan-Russia Relations

- Constraints on Relationship

- Japan-Russia Territorial Dispute

- Korea-Russia Peninsula Relations

- North Korea

- South Korea

- Arctic Geopolitics

- Russia's Energy Diplomacy

- China-Russia Energy Ties

- Japan-Russia Energy Ties

- South Korea-Russia Energy Ties

- Issues for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1. Russia and Northeast Asia

- Figure 2. China's Trans-Asia Initiatives

- Figure 3. Shanghai Cooperation Organization Membership, August 2016

- Figure 4. Territorial Dispute and Russo-Japanese Borders

- Figure 5. Russian Railway Development in North Korea

- Figure 6. Potential Shipping Routes in the Arctic

- Figure 7. Russian Pipeline Projects to China and the Pacific

Summary

Since Russia's aggression in Ukraine and its annexation of the Crimea in March 2014, Moscow's already tense relationship with the United States and Europe has grown more fraught. After the imposition of sanctions on Russia by much of the West, Russian President Vladimir Putin has turned to East Asia, seeking new partnerships to counter diplomatic isolation and secure new markets to help Russia's struggling economy. His outreach to Beijing, Tokyo, Seoul, and Pyongyang has met varying degrees of success. The most high-profile outreach was a summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping in May 2014, when the leaders announced dozens of economic cooperation agreements. Putin has met with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe over a dozen times in an effort to resolve a territorial dispute and improve bilateral relations. Putin has also reached out to both Koreas in his bid to step up engagement with Northeast Asian countries.

Russian engagement in Northeast Asia challenges the U.S. strategic presence in the region in a number of ways and represents a new arena of potential concern for Congress. If Moscow's engagement efforts succeed, it could undermine U.S. efforts to impose sanctions on Russia and isolate Putin diplomatically for his intervention in Ukraine. It could also create mistrust between the United States and its allies Japan and South Korea if those countries' leaders are drawn closer to Russia. Diplomatic initiatives in the region to deal with the threat of North Korea's nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs could suffer if Moscow disrupts international efforts to rein in North Korean provocations. Perhaps most importantly, China and Russia could form a regional bloc whose primary purpose could be to reduce U.S. economic leverage and challenge the U.S. security presence in the region.

The Chinese-Russian relationship is driven in large part by the perceived threat of the U.S. rebalance to Asia and their shared perspective of American unilateralism. Concrete progress on bilateral projects, however, is marked by inconsistency and faltering implementation of agreements. With Russia's economy devastated by falling energy prices since 2014, China appears to view Russia as a junior partner. Although Russia-China military relations have increased rapidly, so too has an element of competition, particularly in the Arctic region. Chinese firms are wary of investing in Russia, seeing it as politically risky and commercially unattractive. In multilateral fora like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and new Silk Road initiatives, China wants to expand its economic clout while Russia looks to assert its military dominance in Central Asia. These tensions may prevent a full-fledged strategic partnership, but relations continue to grow stronger through regular bilateral summits and global cooperation.

Japan appears enthusiastic about improving relations with Russia and resolving their territorial dispute over four islands at the northern edge of Japan. Even as U.S.-Japan security links grow stronger, Abe continues to respond to Putin's overtures with an eye on balancing China. Russia's economic engagement of Pyongyang has chilled since the Kim regime resumed testing nuclear weapons and missiles. The stalemate in inter-Korean relations and the abandonment of cross-border projects also limit Russia's potential role in facilitating infrastructure and trade links on the Peninsula. Seoul's increasingly close U.S. alliance contracts the space for Moscow's diplomatic maneuver.

Japan, South Korea, and China all have interest in Russia's supply of oil and gas from its resource-rich Far East. Although several partnerships already exist, dealing with Russia's government-controlled energy companies has proved difficult. Private firms are reluctant to invest in a politically risky environment, and the availability of cheap energy from elsewhere has dampened commercial enthusiasm for investing heavily in Russia's energy industry.

Despite obstacles, Russia's pursuit of better relations with countries in East Asia remains a complicating and potentially destabilizing factor for the U.S. policy of rebalancing its security and economic interests to the region. Russia could become a larger factor for Congress to consider when assessing progress on the rebalance to Asia strategy. Russia's "Turn to the East" could also affect areas of congressional concern such as the efficacy of U.S. sanctions policy, U.S. North Korean policy, U.S. strategy in the Arctic region, U.S. priorities at the United Nations, and global energy politics.

|

Figure 1. Russia and Northeast Asia |

|

|

Source: CRS graphics. |

Introduction

Since the end of the Cold War, Russia has played a mostly quiet role in East Asia, only intermittently focusing its attention on the Pacific while primarily orienting its foreign policy toward Europe and former Soviet states. In the past few years, and particularly in the wake of Russian aggression in Ukraine in 2014, Russia's relations with the West have soured.1 In part as a consequence, Moscow appears to be stepping up efforts to develop closer ties with countries in East Asia, consistent with Vladimir Putin's 2012 presidential campaign promise to "turn to the East." As one European analyst put it, "Originally, Russia was simply attracted by the dynamic developments in Asia and China; however, since the Ukraine crisis and the deterioration of the zapadny vektor ('Western vector') in 2014, its interest has turned into a necessity."2

In 2014, Putin signed legislation to offer a range of tax benefits and subsidies to businesses that establish operations in the Russian Far East, with an eye to expanding Russia's trade with Asia.3 China, Japan, and South Korea, all in need of energy supplies, offer commercial opportunities as the West imposes economic sanctions on Russia and Russia develops its oil and gas reserves. Although most see a geostrategic alignment between Moscow and Tokyo as improbable, such an arrangement could offer a regional counterweight to Beijing's rising stature. At the same time, Russia's flirting with a partnership with China provides a retort to the U.S. "rebalance" to Asia strategy.

Already tense, U.S. relations with Moscow have frayed further since Russia's intervention in Ukraine in February-March 2014 and its initiation of military activities in Syria in 2015. The United States led an effort to impose multilateral sanctions on Russia and isolate Moscow diplomatically, encouraging its Asian allies to do the same. (See Appendix.) Although its economic power is declining as energy prices fall, Russia still has strength in terms of military capability, diplomatic capital by virtue of its permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, status as a nuclear state, and sheer geographic size. Analysts believe leaders in Moscow increasingly view the world through an anti-U.S. lens and hold many grievances against the West.4 From this mindset, Russia may see Asia as an area in which it is able to challenge U.S. interests.

Under President Putin, Russia's outreach to Asia has been inconsistent, and at times contradictory. In 2015, Putin failed to attend the two largest East Asia international meetings: the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and the East Asia Summit (EAS), although Russia is a member of both groupings. While pursuing warmer relations with Tokyo, Russia has accelerated a military buildup on one of the disputed northern islands that Japan also claims. After Russia appeared to engage North Korea, leader Kim Jong-un declined to attend a 2015 World War II commemorative ceremony in Moscow, and the relationship apparently faltered. With China, Moscow alternates between summits with Beijing and shows of military might to counter China's moves, particularly in contested areas like the Artic region. On the whole, the Russian economy remains poorly integrated with Asian countries, despite some apparent natural outlets for more trade.5

This report will examine how Russia has sought to engage Northeast Asian states, and vice versa, since 2012. It will also evaluate the durability of developing relationships and the relative value of these ties to the individual states. It will explore whether Russia might become a bigger geopolitical player in the region, and how this might affect U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific.

For Members of Congress, Russia's relations with countries in Northeast Asia are important to consider. In addition to their impact on regional dynamics, they have implications for general foreign policy oversight, as well as for more specific issues such as the efficacy of sanctions policy, the developing security competition in the Arctic region, and alternative blocs of influence in international fora like the United Nations Security Council. Congress could express concern or interest in this area through additional hearings, an expansion of reporting requirements for the Departments of Defense and State, and other legislation that focuses on Russia's engagement in Northeast Asia.

Possible Implications for U.S. Interests

Potential for a China-Russia Bloc

A Chinese-Russian coalition almost inherently embodies a challenge to the U.S. presence in the Asia-Pacific and could hamper U.S. leadership in the region, as well as globally. During Putin's state visit to Beijing in June 2016, he and Chinese President Xi Jinping issued a joint statement on "global strategic stability" that criticized the United States' military and alliance policies, accusing the United States of enhancing instability and possibly triggering a new arms race.6 A united front by China and Russia could undercut the efforts of the United States and its allies to consolidate international laws and norms as part of the existing international order, a particular focus of U.S. diplomacy in East Asia. As veto-wielding permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, China and Russia already often find common ground on security issues; an enhancement of relations could further diminish American and Western influence in dealing with international problems through the United Nations.

If Moscow and Beijing were to develop a stronger partnership, the two powers might reach a strategic accommodation on areas like the South China Sea and the East China Sea, limiting U.S. ability to challenge China's increasing maritime assertiveness. Some observers already see indications of China's enlisting Russia's support for its regional strategy: in April 2016, Russia's foreign minister joined his Chinese counterpart in saying that non-claimants should not take sides on territorial claims in the South China Sea.7 This appears to be a rebuff to the U.S. position on the South China Sea. Although the U.S. government does not take a position on specific sovereignty disputes, it urges respect for customary international law; opposes the use of coercion, force, or threat to assert claims; and has supported the efforts of smaller Southeast Asian nations to address China's land reclamation and maritime claims though diplomacy and compulsory dispute-resolution mechanisms.8 One barometer for Russia-China relations is Russian willingness to sell China some of its most sophisticated military systems. If Moscow continues to open up its market to purchases from China, the strategic balance of power in Asia could shift in areas such as the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.9 (See "Security Relations" section below.)

Russia and China have also joined voices in objecting to the deployment of a U.S. ballistic missile defense (BMD) system on the Korean peninsula. After North Korea conducted its fourth nuclear weapon test and a satellite launch in 2016, the South Korean government announced that it would deploy a U.S. Theater High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) BMD system to South Korea. Seoul resists full integration into the U.S.-led regional BMD network, but has agreed to a policy of interoperability with U.S. BMD assets. Both Moscow and Beijing strenuously objected to the THAAD announcement, citing the "direct threat" to the security of China and Russia given the range of the system's radar.10 U.S. defense planners and some Members of Congress have supported the idea of an integrated BMD system among Japan, South Korea, and the United States, but vehement Russian and Chinese opposition could contribute to South Korean caution as it goes forward with deployment of the THAAD system.

If Beijing and Moscow pull closer to an informal alliance, the regional organizations that they dominate could become more coordinated and potentially more powerful. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is in the process of admitting India and Pakistan as full members (see "Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) section). This expansion could reduce U.S. economic leverage with SCO members if the group embraces a more integrated economic framework and, some analysts suggest, reduce the efficacy of sanctions in the region.11 Already, U.S. influence in the security sphere in Central Asia is diminished with the closure of its base in Uzbekistan in 2005 and its last base in Kyrgyzstan in 2014.

China and Russia are far from embracing a full alliance with one another. Strong distrust still exists in their bilateral relationship, and cooperation is likely to be on an ad-hoc basis, without encompassing all political and economic dimensions. Despite the barriers to a deeper partnership, however, Beijing and Moscow's shared sense that the new geopolitical order of East Asia should resist a dominant U.S. influence remains a potent force.12

Possible Challenges to U.S. Alliances

South Korean and Japanese response to Russian overtures could create tensions in the U.S. bilateral alliances with each, as well as weaken the international sanctions regime against Moscow. Although the U.S.-Japan alliance has thrived in recent years, Tokyo appears eager to engage Russia, particularly under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's leadership. Some U.S. officials could view Abe's frequent meetings with Putin—which could potentially include a formal state visit to Japan—as undermining the U.S. effort to isolate Putin diplomatically. (This was particularly true in the immediate aftermath of the Ukraine crisis, when the United States avoided meetings with Putin. Washington has adjusted its approach since, and Obama has met directly with Putin.) Washington and Tokyo have made significant advances in their military alliance since 2012, including updating bilateral defense guidelines.13 Implementation of the security legislation that Tokyo passed in 2015 is at a sensitive stage; capitalizing on these upgrades to the alliance will likely depend on continued strong relations at the leaders' level. If diplomatic priorities on Russia diverge, however, the U.S.-Japan alliance could lose some of its recent momentum.

Some U.S. analysts contend, however, that a partnership between Japan and Russia could be beneficial for the United States in the long run.14 They argue that a stronger Japan-Russia relationship could provide a counterweight to China's strength in the region. Particularly in the maritime arena, Japan and Russia could form a complementary partnership in response to China's assertiveness. Russia has traditionally had a strong defense relationship with Vietnam and might be persuaded to back Hanoi's claims in the South China Sea more forcefully. Further, Tokyo seeks support for its territorial dispute with Beijing over the Senkaku Islands (known as Diaoyu in China and Diaoyutai in Taiwan). Russia has not taken a position on the East China Sea territorial claims; some analysts have even suggested that Russia could be a mediator there.15

South Korea's alliance with the United States has strengthened in reaction to North Korean provocations, including Pyongyang's fourth nuclear weapon test, a rocket launch, and the test of a submarine-based missile, all in 2016. The latest upgrade is deployment of the THAAD missile defense system, which may increase Russia's and China's objections to the U.S. military presence in the region. South Korean leaders already face some domestic criticism over Seoul's alleged dependence on the United States; Russian (and Chinese) complaints about U.S. alliances may amplify these voices in South Korean politics. On the other hand, better ties with Russia could help Seoul gain more independence from Beijing. Although China is by far South Korea's most important trade partner, more linkages with Russia could provide Seoul with another, albeit less influential, regional partner on such issues as pressuring North Korea to curb its provocations.

Impact on U.S. Strategy Toward North Korea

Diplomatic and economic support for North Korea from Russia could undermine U.S. and Chinese efforts to pressure North Korea to change its behavior and re-engage in denuclearization talks. If Moscow and Pyongyang draw closer—as they appeared to be doing in 2014-2015—the united diplomatic front among the Six-Party Talks partners could fray. The Talks, the multilateral negotiations comprised of the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, and Russia, have not convened since 2008, but remain the primary multilateral vehicle to deal with North Korea's nuclear programs. Many observers saw Moscow playing a small but productive role in the talks when they were active in the mid-2000s, but Russia's renewed interest in staking a diplomatic presence in the region could mean their engagement in the talks is more disruptive to the process. Russia could provide more support—at least diplomatically—for the North Koreans even if China takes a harder line against the regime.

Russia, however, appears to remain concerned about North Korea's nuclear weapons program and the uptick in relations seems to have been arrested by North Korea's provocations. Despite working with China to dilute several United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions that condemned Pyongyang's nuclear weapon and missile tests, Russia ultimately signed on to a tough resolution (UNSC Resolution 2270) in 2016 that could hurt its economic projects in North Korea. The resolution bans or limits North Korean exports of several natural resources, which could curtail Pyongyang's ability to compensate Russian companies for their investments and deliveries. Implementation of existing projects may slow or fail as a result. Some analysts estimate Moscow's losses at several hundred million dollars due to lost trade.16 In any event, it is unclear how much economic assistance and trade Russia could provide North Korea, particularly if Pyongyang is unwilling to pay market prices.

Some analysts argue that if the United States and its allies moved more aggressively to alter the situation on the Peninsula, or if the regime in Pyongyang collapsed on its own accord, Moscow and Beijing may find common cause in supporting North Korea. Both countries share a strong desire to prevent a shift in the regional balance that a reunified peninsula under U.S. influence might produce.17

China-Russia Relations

Moscow and Beijing have many reasons to cooperate. Both countries have a desire to counter what they claim to be U.S. hegemony, both regionally and worldwide. Both are wary of the U.S. military presence in Asia and often criticize U.S. efforts to upgrade the United States' defense capabilities with its treaty allies, Japan and South Korea. Both hold vetoes on the UNSC and often work together to adjust or oppose UNSC resolutions that are supported by Western countries. Both were unnerved by a series of "color revolutions" worldwide in which citizen demonstrations brought down or starkly challenged authoritarian governments, and both are suspicious of U.S. involvement in these movements. When Chinese President Xi Jinping held a military parade in September 2015 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the victory over Japan in World War II, Putin appeared prominently beside Xi in Tiananmen Square, just as Xi did for Putin in commemorating the victory over Nazi Germany in Moscow earlier that year. Scholars point to Putin's personal interest in cultivating a friendship with Xi to strengthen the bilateral relationship.18 Experts have also advanced arguments that both capitals, driven in part by national identity factors, have supported each other in international disputes and intentionally minimized differences in their approach to foreign policy.19

Relations have been particularly robust since Xi took power in 2012. In 2013, Xi made Russia his first overseas trip as president.20 Since then, the two presidents have conducted a series of high-profile visits and announced similarly high-profile agreements, often apparently calibrated to make a statement to the United States and other Western countries. In 2014, as Western powers adopted sanctions on Russia in retaliation for the Ukraine intervention, China and Russia held a summit and announced a $400 billion natural gas deal, along with over 40 other economic cooperation agreements.21 Shortly after the summit, both leaders attended the opening of bilateral naval exercises in the East China Sea near the disputed islands that both China and Japan claim.

Russia's intervention in Ukraine shaped relations with China today. On the one hand, it drove closer cooperation and a strong show of solidarity as Western nations imposed sanctions and attempted to isolate Putin diplomatically. However, it also created an imbalance in the relationship, as Moscow was suddenly frozen out of European foreign policy and in need of Beijing's support. With China enjoying a boost in its leverage, it was able to derive more concessions from Russia, including in negotiations on energy deals. Thus, while the Ukraine crisis intensified an already warming relationship, it also may have introduced an asymmetry in relations. Russia, still smarting from losing its superpower status, may not be comfortable playing the role of junior partner to its former rival China. As Russia's economic and diplomatic strength have withered, China has not remained singularly driven by what one journalist calls "political sympathy" as it pursues its own national interests.22 While Russia is driven closer to China by economic necessity, China has more options.23

Further, Beijing has appeared to be uneasy with Russia's invasion of Ukraine, as it is at odds with China's official statements concerning respect for the sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity of other nations. China has maintained a policy that many analysts call "benevolent neutrality" toward the Ukraine crisis, carefully treading the line by stating its respect for Ukraine's sovereignty but noting that it "takes into consideration the complicated historical background and realistic factors of the Crimea issue."24 However, any future Russian military adventurism could prompt Beijing to consider distancing itself from Moscow. This would be particularly true if China begins to assess that Russian actions are destabilizing regions to the detriment of Chinese interests.

A Relationship of Convenience or a True Alliance?

Analysts are divided over how enduring the Moscow-Beijing partnership will be in the medium to long term. In early 2016, a senior Chinese official described the relationship as "a stable strategic partnership and by no means a marriage of convenience: it is complex, sturdy, and deeply rooted."25 To a large extent, it is dependent on external events in a vastly complicated web of relationships around the world. U.S. behavior may be the largest variable: to the extent that China and Russia feel that the United States is challenging their strategic space, they may feel driven to develop stronger relations. In the current context, however, Beijing may not want to enter into an explicitly anti-Western alliance; its trade volume with the United States dwarfs that with Russia, and it is loath to confront the West directly as it continues its path of economic development.

Other factors could prevent a more full-fledged alliance, not least among them a history of rivalry, including the ideological divide that led to the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s. The Russia-China relationship appears to be characterized by a degree of strategic mistrust. Each nation has responded, sometimes aggressively, to counter the other's military advances, particularly in the Arctic region. (See "Arctic Geopolitics" section below.) Tensions have also periodically risen because of many Russians' perception that large numbers of Chinese migrants are crossing the border for possible economic opportunity in the sparsely populated Russian Far East. Many observers point out that the flow may go in the other direction, given the comparative economic vibrancy of the Chinese side, and assert that the numbers of Chinese are much lower than suspected.26 Regardless of the reality on the ground, however, Russian popular opinion continues to harbor suspicions about Chinese presence in the resource-rich region.

Elsewhere in Asia, Chinese and Russian interests sometimes collide. In Southeast Asia, Russia historically had the strongest relationship with Vietnam since the Soviet Union allied itself with North Vietnam and remained its benefactor through the Cold War period. Today, the Russian military enjoys access to Vietnam's Cam Rahn Bay base. Beijing is wary of Moscow's relationship with Vietnam and may be frustrated that Russia does not back China's position in the South China Sea more fully. Similarly, Russia does not want to lose its foothold in Southeast Asia or alienate other ASEAN powers by siding with China.27

Commercial interests in China are also increasingly wary of investment in Russian projects. The drop in energy prices has cast doubt on the profitability of a number of energy projects, and investment efforts in Russia have fallen short of earlier goals. (See "China-Russia Energy Ties" section.) Other than the "political" development banks (state institutions driven by Beijing's political interest), few large banks are interested in taking on risky ventures given Russia's economic conditions and the imposition of international sanctions. Although Russia and China pledged in 2011 to increase trade to $200 billion by 2020, the two countries missed the interim goal of $100 billion by 2015 by nearly $35 billion.28 One Chinese scholar described the relationship with Russia as "warm politics and cold economy."29 Trade between the two nations plummeted in 2015, with Chinese imports from Russia falling by nearly 20% and Chinese exports to Russia falling by 34%,30 although these declines are mostly due to the steep drop in energy prices. In the economic relationship, Chinese power is again evident: China is Russia's largest trading partner, but Russia does not rank in China's top five partners.31

Security Relations

China-Russia security relations have advanced significantly since 2012. Russia and China have held increasingly large and sophisticated military exercises since 2011, including joint naval drills in the East China Sea in 2014 and in the Sea of Japan in 2015.32 The exercises include war gaming, as well as search and rescue operations and amphibious assaults. In early 2016, the two countries' defense ministers announced that they intended to deepen military cooperation and increase the number of joint exercises.33 Analysts say that Beijing and Moscow intend to send strong signals to the West, particularly the United States, by holding these high-profile exercises.34 Both Putin and Xi attended the opening ceremonies of the 2014 drills, signifying the political importance of the exercises.

Russian arms sales to China have been a central aspect of the defense relationship, running about $2-$3 billion annually in the early 2000s. Sales appeared to dwindle in the mid-2000s, but have recently seen another uptick, particularly since the Ukraine crisis. In 2015, Moscow agreed to sell China some of its most sophisticated weaponry—such as the Sukhoi Su-35 fighter jets and S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems—because of a perceived need to boost defense industry exports.35 Some analysts believe increases in arms sales could lead to more technology transfers to China as well as cooperation on defense-related research and development.36

However, competition and distrust are also evident in the area of arms sales. Russian arms dealers are suspicious that China is copying Russian designs as China's military modernization effort moves toward domestic manufacturing.37 Moreover, Russia and China have begun to compete with one another in the international arms market, with both countries targeting Asian and African middle-income countries. Russia finds itself at a disadvantage in this area, as China tends to offer its arms deals along with larger, more comprehensive development packages that include favorable loans and infrastructure investments.

Cooperation at the United Nations

As permanent, veto-wielding members of the Security Council, Russia and China often find common cause at the United Nations, particularly in opposing positions taken by the other three members of the Security Council: the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. In recent years, Russia has generally deferred to China in matters related to North Korea, while China has followed Russia's lead on negotiations involving Syria. While this pattern can build cooperation and trust between Moscow and Beijing, occasionally it can also generate tension. As the UNSC debated a resolution imposing sanctions on North Korea for its fourth nuclear test in February 2016, Russia reportedly was angered by China's failure to adequately protect Russian commercial interests in its North Korean investments. Overall, however, the two capitals often find it mutually beneficial to support each other's interests. If confrontation between the United States and Russia and/or China intensified, the United Nations represents one of the primary arenas where U.S. global interests can be challenged.

Competition and Cooperation in Regional Fora

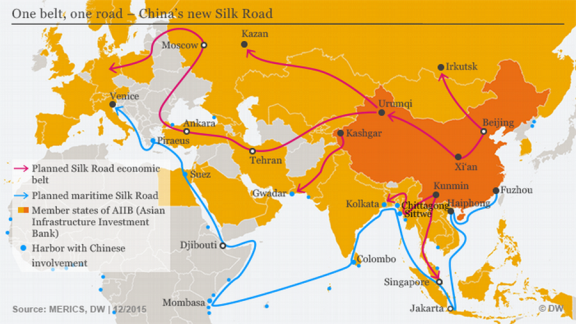

Both China and Russia have advanced new initiatives that aim to consolidate trade and transportation networks between Europe, Asia, and even Africa. These plans reflect both countries' interest in developing stronger economic links, particularly in the energy realm, with Central Asia and beyond. China's "One Belt, One Road"38 (OBOR) initiative envisions the development of energy infrastructure, roads, railways, ports, and industrial parks that span three continents. Putin, meanwhile, has proposed a Eurasian Economic Union concept that similarly promotes economic integration; the original membership included Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan, but Putin has stated he would like it to expand to all former Soviet states. An inherent tension exists in these two plans: Russia has long considered Central Asia to be a part of its traditional sphere of influence, and is wary of China's drive to build infrastructure that could redirect economic activity toward China.

In May 2015, Beijing and Moscow announced that they intended to link the two plans, with China providing most of the necessary capital and Russia offering security assurances for the projects. Despite the fanfare of the announcement between the two leaders, analysts report little progress in reconciling the two projects.39 When Putin paid a state visit to Beijing in June 2016, a Russian commentator noted that the plans to link the initiatives "have not advanced a step."40 To some observers, the declaration may have been intended less as a blueprint for action and more as an indication of the leaders' determination to avoid open hostility between the two plans.41

|

|

Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies. December 2015. |

Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)

A similar dynamic has played out in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO): Russia seeks to assert its traditional role as a guarantor of security to the Central Asian region while China looks to establish its centrality as an economic powerhouse. The SCO also reinforces the shared sense of the need to counter what are seen as Western, and specifically U.S., efforts to contain China and Russia. An early SCO (then the "Shanghai Five") joint statement pledged to "oppose intervention in other countries' internal affairs on the pretexts of 'humanitarianism' and 'protecting human rights;' and to support the efforts of one another in safeguarding the five countries' national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and social stability."42 In 2009, the SCO approved Russia's cyber- and information war-related proposal, which described the spread of information damaging to "spiritual, moral, and cultural spheres of other States" as a security threat.43 During the 2014 SCO meeting, China's Minister of Public Security accused "external forces" (implicitly referring to Western nations) of attempting to foment "a new wave of color revolutions."44

The SCO (originally the "Shanghai Five") was created in 1996 by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, with the Treaty on Deepening Military Trust in Border Regions (1996) and then later the Treaty on Reduction of Military Forces in Border Regions (1997). Uzbekistan later joined, and India and Pakistan appeared to be inching toward full membership in 2016.45 Ten other countries hold observer status, including Iran. The initial purpose of the grouping was to engage in confidence-building, manage border conflicts, and maintain stability in Central Asia, but the group eventually came to focus on wider political, security, economic, and cultural issues as well.46 Regular military drills among the members focus mostly on maintaining stability and combatting what member states deem to be "terrorism, separatism, and extremism."47

For years, China has been pushing the SCO to take on more economic roles. China-led economic initiatives within the organization include a potential free trade zone (first suggested in 2003), an SCO Development Bank, and a Development Fund. The SCO agreed in 2012 to establish the Bank and the Fund and decided during the 2015 summit to continue to work toward their creation.48 Nevertheless, few concrete steps have been taken yet due in part to Moscow's and other capitals' concern with Beijing's economic influence within the SCO and in Central Asia.49 The slow pace of the SCO's actions in the economic realm has prompted China to push for its own Eurasian initiatives.50

|

Figure 3. Shanghai Cooperation Organization Membership, August 2016 |

|

|

Source: Stratfor, July 2015. See https://www.stratfor.com/image/china-and-russias-evolving-relationship. |

Japan-Russia Relations

Russia's overtures to the East appear to have gained the most traction in Japan. Despite joining Japan's G7 partners in imposing sanctions on Russia, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has aggressively pursued better relations with Moscow. In May 2016, Abe visited Putin in Sochi, Russia, to discuss the two countries' lingering territorial dispute (see "Japan-Russia Territorial Dispute" section) and pledge increased economic engagement. The two leaders made plans to meet again at the Eastern Economic Summit in Vladivostok in September 2016, with a possible visit by Putin to Japan later in the year. In mid-2016, the Moscow-Tokyo relationship appeared vibrant to many observers.

When Abe returned to the premiership in 2012, after an earlier one-year term as Prime Minister in 2006-2007, he moved to reinvigorate Japan's diplomacy. Among his targets was Russia, with which Japan has never signed a peace treaty formalizing the end of World War II. Abe met Putin five times in his first year in office, explicitly aiming to resolve the territorial dispute over four islands in the Kuril Chain, known in Japan as the Northern Territories, which are now under Russian administrative control. Overall relations were on the upswing: bilateral trade in 2013 rose to a record $34.8 billion, the ministers of defense and foreign affairs held "2+2" talks, and the two governments announced new plans on energy cooperation. As many Western powers distanced themselves from Russia in part because of Putin's anti-gay comments and policies, Abe was among the most high-profile leaders at the 2014 Winter Olympics Opening Ceremony in Sochi, Russia.

On its face, a Russia-Japan partnership makes sense. Japan, particularly under Abe, faces skepticism from neighbors who distrust Japan and see any Japanese move to advance its security role in the region as a reversion to militarism. After shutting down its nuclear power generation capacity following the March 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, Japan is also in need of more energy imports; the Russian Far East offers an abundance of fossil fuels practically next door. Shared values with the West and a commitment to democracy aside, Japanese leaders appear to take the position that Russian military moves in Eastern Europe do not present a direct security threat to Japan. Russia wants customers for its natural resources and has for years promised to become a more engaged Pacific power. Putin, too, needs friends: now somewhat of an international pariah for his aggression in the Crimea, crackdown on civil liberties at home, and jingoistic rhetoric, his power is challenged by plummeting energy prices and economic sanctions.

At the center of both countries' strategic concerns is China's massive economic and geopolitical presence. For Japan, lessening its northern territorial vulnerabilities would allow it to focus on the more acute problem of China's intrusions and claims in the disputed Senkaku Islands (known as Diaoyu in China and Diaoyutai in Taiwan) as well as free up military and Coast Guard assets currently stationed in the north. Russian bombers and patrol planes routinely fly through Japan's northern air space, prompting Japan to scramble fighter jets in response. In 2015, such scrambles increased sharply to levels not seen since the Cold War.51 Both Russia and Japan may be eager to exploit each other in relation to concerns about China's increasing maritime presence in the Pacific. If an agreement on the Kuriles is accompanied by a consensus between Japan and Russia to cooperate at the strategic level, the reasoning goes, Abe and Putin could tilt the balance of regional relations in their favor, at the expense of China.

Constraints on Relationship

Many indicators suggest that efforts to upgrade the Russia-Japan relationship may falter, however. Moscow's foreign policy can be unpredictable and inconsistent, perhaps even by design, and under Putin Russia has been known to lash out at potential rivals. Russian oil and gas supplies are far from a panacea for energy-hungry Japan, and Tokyo may see Russian attempts to manipulate energy supplies to Eastern Europe for political leverage as a warning sign. Russia's development of its Far East's energy resources has been problematic, dominated by Russian national energy firms and subject to fluctuating geopolitical concerns. For years, Moscow has played coy about the route of pipelines from its Far East to Asian markets, and Japanese energy firms may see the area as too risky for further investment. Domestic politics in each country also restrain both leaders, who are loath to be seen as giving up concessions at a time when territorial disputes are so prominent for both countries.

After Russia's aggression in Ukraine, Japan faced considerable pressure from the United States and other Western powers to isolate Moscow diplomatically and financially. Japan complied with imposing financial sanctions, but took a somewhat minimalist approach, including postponing a visit from Putin and freezing several other diplomatic initiatives. Though Tokyo has restarted its efforts to engage Russia, it faces a difficult balancing act given the concerted effort by other Western nations to punish Putin for his behavior. Russia and Japan used to cooperate in the G-8, for example, but that venue was eliminated after Russia was ejected from the group for its intervention in Ukraine.

The U.S.-Japan alliance plays more than just a passing role in Japan's strategic calculus. Washington puts pressure on Tokyo to support U.S. foreign policy priorities, though there is a high degree of natural strategic convergence. The United States and Japan share a fundamental affinity: upholding the rules and norms of the international order has been a major emphasis in the foreign policies of Washington and Tokyo. Moscow takes a starkly different approach, which some analysts describe as classical realpolitik. Putin appears to view the world and Russia's role in it through a sharply anti-American lens, while Japan continues to identify the U.S.-Japan alliance as the centerpiece of its security strategy. If Putin and Abe manage to advance relations, reconciling these different views could be difficult.

As Tokyo and Moscow have explored a detente, Putin has emphasized the benefits of expanding the Japan-Russia trade relationship. Current economic relations are not particularly robust: Russia was Japan's 14th-largest export market and 12th-largest import market in 2015, while Japan was Russia's 6th-largest trade partner.52 Foreign investment has also been relatively low: Japan External Trade Organization data show that Japanese investment in India and Brazil, fellow BRICS countries with Russia, was 297% and 541% more, respectively, than Japanese investment in Russia in 2015.53

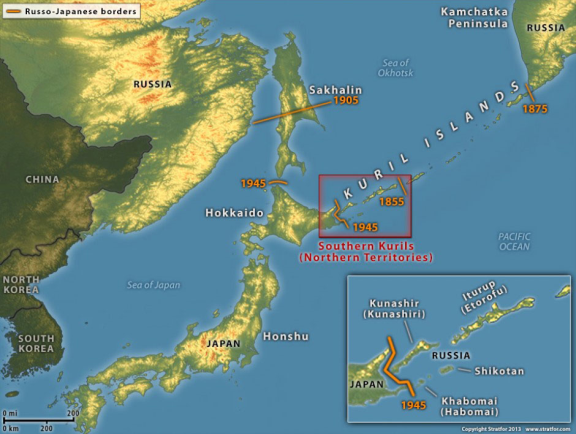

Japan-Russia Territorial Dispute

For years, Japan's policy toward Russia has focused on the dispute over the ownership of four small islands north of Hokkaido, known as the "Northern Territories" in Japan. These islands—Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and the Habomai Archipelago—were seized by the Soviet Union in the final days of World War II.54 Since the 1960s, periodic attempts to resolve the dispute have fallen short. Although Soviet and Russian governments have floated the idea of returning two islands, Tokyo has insisted on reversion of all four islands. When some Japanese negotiators developed a "two islands plus alpha" compromise in 2000-2001 (meaning two islands in addition to other concessions, such as fishing rights), hardline elements in the Japanese Foreign Ministry defeated the proposal.

Since Abe's return to office and his initiative to rebuild relations with Russia, his government has restarted efforts to resolve the lingering territorial issue. Despite renewed attention and some analysts' optimism, progress has not materialized. Under Putin, Russia appears to have little appetite for ceding territory, despite the fact that Putin mentioned a "hikiwake" (a judo term meaning a draw) back in 2001. Russia has apparently consolidated its claims over the islands by sending high-level emissaries and continuing an ongoing military buildup. The Russian military conducted a series of exercises throughout Russia's Eastern District in late summer 2014, including on Etorofu and Kunashiri. Another set of exercises in spring 2014 included bombers and submarine patrol aircraft that circled Japan.55 In August 2015, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev visited Etorofu, highlighting Moscow's development plan for the islands, prompting Tokyo to lodge an official protest. Medvedev also visited the islands when he was president of Russia in 2010.

After a May 2016 meeting with Putin, Abe declared that the leaders agreed "a new approach" was needed, yet gave no indication of a politically acceptable compromise. Putin has emphasized the continued relevance of the 1956 Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration, thereby suggesting that Russia remained willing to transfer Shikotan and Habomai (the smallest group of the disputed islands) to Japan after the conclusion of a peace treaty. Japan has continued to demand return of all four islands, though some analysts see hints that it would be open to a compromise of some sort. Without resolving the territorial issue and signing a peace treaty, many analysts doubt that Japan and Russia can meaningfully advance bilateral relations.56 Due to deeply entrenched national identity issues associated with the territorial dispute, many analysts see a breakthrough as unlikely.57 The question is if Putin and Abe, both seen as strong nationalist figures in their respective countries, can reach a deal that serves each other's needs.

|

|

Source: Stratfor, April 2013. See https://www.stratfor.com/image/russo-japanese-islands-dispute. |

Korea-Russia Peninsula Relations

Russia's interest in the divided Korean peninsula is less easily defined and has not occupied as central a role in its foreign policy as have its relations with China. As Russia has refocused its attention on East Asia, Moscow's relations with the Koreas have developed more fully and, in particular, Russian views on a potential reunification of Korea have come into sharper relief. Russia's desire to develop its natural resources and sell them to the Asian market could be strengthened by land access through the Koreas, leading one Russian analyst to call Russian involvement in the Peninsula as "the key to Asia."58

Russia has a pragmatic interest in stability and peace between the two Koreas, not least because of its land border with North Korea. On the other hand, the division between North and South offers Moscow an opportunity to pressure South Korea using Russia's ties to the North. Russian leaders have exploited both of these positions to maximize its leverage in the region.

In the past, some analysts have posited that reunification may not threaten Russia's interests compared to the potentially seismic geopolitical implications for the United States, Japan, and China.59 But since it has begun to execute its "look east" strategy, Moscow appears to have prioritized the maintenance of the status quo situation based on the fear that any change could lead to a reduction in Russian influence. Russian analysts generally emphasize economic and infrastructure projects as a first step in inter-Korean cooperation, and some analysts suggest that eventually Russia may favor peaceful unification under a possible federation system.60 Russian officials have stated that they opposed joint defensive exercises between the United States and South Korea and share concerns with China about U.S. troop presence on its borders under a U.S.-allied unified Korea.

For many years Russia played a small, occasionally productive role in the now-dormant Six-Party Talks. Moscow now appears to be amplifying its role as a regional actor in dealing with North Korean provocations.61 Apparently following China's lead, Russia has insisted that North Korea commit to denuclearization and has joined the UNSC resolutions that condemn Pyongyang's repeated nuclear weapon and missile tests. China and Russia have often both watered down some of the toughest sanctions proposed by the UNSC, but have not blocked them and have approved increasingly critical language to describe North Korea's actions.

North Korea

Historically, North Korea was a client state of the former Soviet Union and had extensive economic, political, and military ties to its patron. After the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, economic support for North Korea evaporated, leaving China as North Korea's dominant economic partner. Pyongyang-Moscow relations weakened and both countries were consumed with addressing their own internal problems. Gradually, Moscow and Pyongyang re-engaged, and relations appeared positioned to develop further in 2014. As China's relations with North Korea dampened under Kim Jong-un, Russia appeared poised to step in as a North Korean ally. Russia announced it would forgive 90% of North Korea's debt and accelerate investment in North Korea to build a gas pipeline and rail links through the country. Although Russia was not able to offer China's level of economic assistance or diplomatic protection, relations appeared to be on the upswing as the two countries declared 2015 a "Year of Friendship." Defense relations appeared to be improving: the two countries announced they were planning joint military exercises and possible new confidence-building security agreements, and military officers paid official visits to the other's capital.62

However, the partnership seemed to chill after Kim Jong-un appeared to accept, then suddenly shun, Putin's invitation to attend Russia's commemoration of the end of World War II in May 2015. This rift between the two leaders, combined with Pyongyang's series of provocations in early 2016 and Russia's subsequent willingness to join the international community in punishing the regime, may have halted any sustained upgrade of the relationship. Still, some analysts see the possibility of Moscow-Pyongyang cooperation expanding in the future, particularly as Putin looks to assert more Russian influence in the region.63 Among the participants in the now dormant Six-Party Talks, Moscow now imposes the fewest demands on North Korea, promoting negotiations and economic development without conditions.64 If Pyongyang at some point decides to re-emerge from its isolation, it may seek more coordination with the country that most closely supports its political goals of reunification with independence from China and the United States.

Most foreign-funded large-scale infrastructure projects in North Korea have faltered due to the challenges of investment in North Korea. The grander plans for gas pipelines, electric transmission lines, and a functioning railway through the two Koreas have all run into obstacles. North Korea's Special Economic Zone in Rason (located in the two municipalities Rajin and Sonbong) has provided the most significant area of investment. With access to the Sea of Japan, the warm-water port of Rason is a center for both Chinese and Russian projects, although Chinese investment far exceeds Russian.65 Russia constructed a railway segment—opened in 2013 after about a decade of construction—that connects the port with the Russian border city of Khasan and modernized the Rason terminal.66 According to reports, however, the railway is used only occasionally for deliveries of coal to North Korea to be sold to Asian markets.67 Russia has also reportedly invested over $60 million to develop one of Rason's piers.68 The SEZ may represent the most promising area for further development of economic relations, but could also be an arena of competition with Chinese investors.

|

|

Source: Stratfor, September 2013. See https://www.stratfor.com/image/reconnecting-russia-north-korea-rail-link. |

South Korea

Russia appears to regard South Korea as a flexible player in regional geopolitics. This perception, undergirded by growing trade, has made South Korea-Russia relations stable and generally friendly, if not widely developed. Both countries—wary of depending too heavily on China—may see increased cooperation as positive in diversifying regional partnerships. Compared to her predecessors, President Park Geun-hye has increased emphasis on reunification and the need to prepare for it; she may see Russian economic integration and friendly political ties as helpful for this eventuality. Tensions have emerged, however, as Moscow has looked to play a more assertive role in dealing with North Korea, particularly in the wake of North Korea's early 2016 nuclear test and rocket launch.

As Park began her presidency in 2013, Russian and South Korean strategies appeared to be complementary. During the first years of her term, Park promoted her strategy of building trust with North Korea. In this "trustpolitik" approach, she welcomed Russian plans to build new rail and pipeline links through North Korea. Russia responded favorably to South Korean rhetoric on developing strong Eurasian cooperation and economic links. Park's "Eurasian Initiative," announced in 2013, sought to build energy and logistic infrastructure to link European and Asian trade more closely. This area of cooperation was on display during two 2013 summits—the first in Moscow and the second in Seoul: the two sides agreed on a long list of potential cooperative projects on the peninsula, ranging from new infrastructure and development of energy trade to environmental agreements.

The promise of these projects has largely not panned out. North Korea's provocative missile and nuclear weapon tests in the years since have stalled many of Seoul's efforts to build such trust, and many of the joint Russia-South Korea projects have stalled as well. For example, after the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 2270 imposing stricter sanctions on North Korea, South Korea halted the practice of using Rason for transshipments of coal from Russia. Although Russia-South Korea presidential summits emphasized growing trade ties, the two nations do not currently have particularly deep trading relations. Russia is South Korea's 15th-largest trade partner overall and South Korea is Russia's 9th largest.69 Russia's exports to South Korea are overwhelmingly dominated by the energy sector. (See "South Korea-Russia Energy Ties" section below.)

Strategic differences have emerged as well. Some observers claim that Moscow does not perceive the U.S.-South Korea alliance in the same way it sees the U.S.-Japan alliance. Whereas the U.S.-Japan alliance is seen as a threat to Russia's security, Russian analysts see the U.S.-South Korean counterpart as dedicated mostly to maintaining stability on the Korean peninsula.70 However, it appears that Moscow views some U.S.-South Korea alliance initiatives with skepticism. In February 2016, in the wake of North Korea's fourth nuclear test, the United States and South Korea announced that they would move forward on deployment of the Theater High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) ballistic missile defense (BMD) system. China had earlier criticized the possibility, and Russia echoed Beijing's complaints that the system's radar range extended well beyond the Korean Peninsula and would threaten the region's security.71

South Korea-Russia relations have been disturbed by a series of other factors. Park declined to attend Putin's May 2015 ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany. As Russia has moved to become a more active player in responding to the North's provocations, Seoul has taken issue with Moscow's approach, even as Russia has shown a willingness to come down harder on North Korea. South Korea has taken a harder line on sanctions and other punishment of the North, while Russia continues to encourage direct talks with Pyongyang. Beyond these different approaches, some analysts see Seoul as somewhat dismissive of Russia's relevance to the Peninsula's security problems, an attitude that does not please Moscow.72

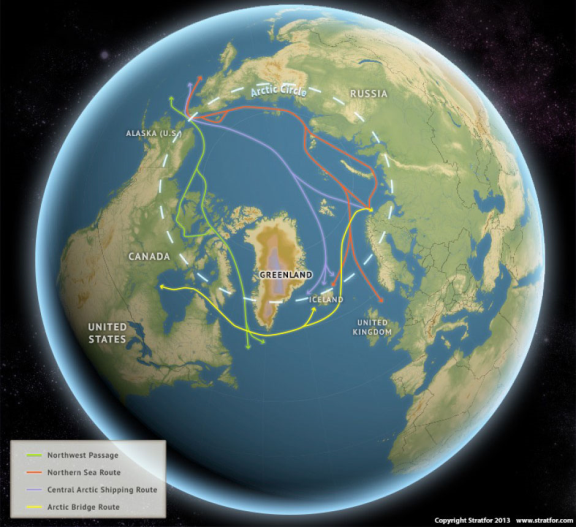

Arctic Geopolitics

The Arctic region is emerging as new arena of strategic competition. Due to climate change and the development of ice breakers, the Northern Sea Route has become passable year-round. This passage is the shortest route between the Atlantic and Pacific and can decrease the travel time by sea between Europe and Asia by 12 days. For Japan, use of this route, particularly for energy imports, would provide an alternative to the more risky and crowded southern route. In 2015, the Russian government announced a plan to increase the capacity of the Northern Sea Route 20-fold in the next 15 years by developing the necessary infrastructure, including emergency services and escort vessels.73

Analysts caution, however, that increased traffic on the northern passage could also encourage the militarization of the area as countries move to protect their commercial interests. The past five years have revealed undercurrents of military competition. As Russia has re-opened shuttered Soviet-era military bases and moved to build up its infrastructure in the Arctic, China has also made its first forays into the region. After sending its first icebreaker into the Arctic in 2012, China is now building another. (The United States also has 2 operational icebreakers; Russia has 41.)74 After China sent its first icebreaker on its maiden voyage, Russia launched military exercises as the Chinese vessel neared Sakhalin. In 2013, Chinese naval warships appeared in the Sea of Okhotsk, setting off massive land and sea military exercises by Russia in response, personally supervised by Putin.75 In March 2015, Russia held large-scale military exercises involving 45,000 troops and submarines in its strategic nuclear arsenal. Russia also plans to develop a new army brigade around its energy projects on the Yamal peninsula. As President Obama visited Alaska in September 2015, five Chinese navy ships were spotted in international waters in the Bering Sea.

The Arctic Council is an international forum devoted to monitoring and discussing issues in the region. The United States, Russia, Canada, and several Scandinavian countries are permanent members, while Japan, China, and South Korea are among the 12 observer nations.76 Russia was vocal in support of Japan's application for observer status in 2009, but not supportive of China's application.77 Japan's interest in Russia's $27 billion Yamal liquefied natural gas (LNG) development project may increase its attention to the Arctic region. Although this suggests that Japan and Russia could view the Arctic as a cooperative arena for energy trade, the proximity of the disputed Northern Territories to the Arctic northern route, particularly given Russia's continued military buildup on the islands, points to an area of potential tension in the relationship.

|

|

Source: Stratfor, May 2013. See https://www.stratfor.com/image/arctics-growing-importance-trade. |

Russia's Energy Diplomacy

Russia's massive but underdeveloped energy reserves constitute a large part of the appeal of Russia for energy-hungry Asian nations, and lend economic ballast to the push to develop closer diplomatic relations. Although Russia already exports oil and gas to Japan, China, and South Korea, Russian oil and gas make up a small percentage of the energy supply for these three states that depend heavily on fossil fuel imports. All three nations depend heavily on energy imports from the Middle East, a region where political turmoil often threatens access and creates volatility in prices, although China has worked to diversify its energy suppliers and has growing energy ties with Central Asia and other regions, too.78 For Seoul, Tokyo, and Beijing, access to oil and gas supplies from Russia could offer an additional, stable source of energy imports. Russia, too, has increased its focus on developing these markets. In February 2014, the Russian Ministry of Energy released an updated energy strategy that sharply raised its targets for exports to the Asia-Pacific region as a percentage of total energy trade, from 27% in its 2009 strategy, to 34%, with a particular jump in natural gas exports.79

However, the drive to develop robust energy partnerships with Russia has diminished in the past few years due to several factors. Some Asian customers see the potential for availability of large quantities of natural gas imports from the United States, and the dramatic decline in energy prices has reduced the appetite for costly new development projects in Russia's Far East. Moreover, private firms are reluctant to invest in Russia's market because of the Kremlin's assertion of control over energy companies in Russia and a history of failed deals. More recently, the imposition of sanctions by Western countries has limited access to capital markets and technology for major infrastructure development, such as LNG terminals.

Asian companies also complain that Moscow has a tendency to play different countries off one another in bidding for upstream projects, creating another layer of political risk. The competition becomes even more fraught when dealing with pipeline projects because the supply is directed to only one destination. This creates a stable source for the buyer but also provides more leverage to the supplier. Russia may consider the inflexibility of pipelines to be a risk factor when evaluating long-term commitments.

|

Figure 7. Russian Pipeline Projects to China and the Pacific |

|

|

Source: Stratfor, January 2013. See https://www.stratfor.com/image/russias-growing-energy-ties-asia.

|

|

Snapshot of Pipeline Politics in Russia The example of the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean Pipeline (see map above) illustrates the frustration and the promise of energy deals with Moscow. Originally proposed in 2001 by private oil firm Yukos, the project eventually was taken over by the government-owned Transneft and Rosneft companies. Japan and China competed for access to the pipeline, with Japan promising full financing for the pipeline to go the roughly 4,800 kilometers (nearly 3,000 miles) from Central Siberia to the Pacific for export to Japan. For years, Moscow equivocated, refusing to make a firm commitment to either project. China and Russia signed an agreement to build the pipeline in 2003, with construction commencing in 2004. Moscow appeared to continue to hedge its bets by building the first leg of the pipeline to Skovorodino, retaining the option of directing the pipeline to the Pacific for export to other markets. After Russia secured a loan worth $25 billion from China, construction on a spur directly to China's Daqing refineries began in 2008, with oil first delivered in 2011. Construction was completed on the final stage, running from Skovorodino to the Pacific port of Kozmino, in 2012. Although the completion of the pipeline significantly expanded Russia's export capacity to Asia, the lengthy negotiations, total cost, and shifting landscape of private and state-owned energy entities demonstrate the challenges in extracting more energy supplies from Russia, particularly with additional sources of energy becoming more available internationally. |

China-Russia Energy Ties80

Energy deals have formed the centerpiece of Russia and China's recent partnership, particularly after Moscow's relations with the West soured after the crisis in Ukraine. China, as the world's largest energy consumer, is seeking to boost the share of renewable energy in its overall energy mix, but is also seeking new sources of fossil fuels for its economy, now growing more slowly than in the past, at approximately 6% a year. Like Japan, China wants to reduce its dependence on Middle East energy suppliers, and Russia's large reserves have been among its targets for new development. China has been willing to sign large oil-for-loan deals with Russia. Russia supplies over 10% of China's crude oil imports, with some of this coming via pipeline from Eastern Siberia oil fields.

China does not currently import any significant amount of LNG from Russia. It inked two massive gas pipeline agreements with Russia in 2014, but these eye-catching deals—the "Power of Siberia" and "Altai" gas pipelines—have been postponed until at least the 2020s, and doubts are growing about their profitability. Meanwhile, China has diversified its suppliers.81 While Russia was hoping to use China to demonstrate to its largely European market that it had other buyers, the fate of the deals has not helped Moscow make its case.

China's push to develop energy deals with Central Asia has yielded several major pipelines with Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.82 These agreements have raised tension between these countries and Russia, however, given Moscow's view that these former Soviet republics should operate within its sphere of geopolitical influence. Central Asia's rich gas fields now compete with Russia's reserves on the international market and increase China's energy security, particularly because the gas is delivered via dedicated pipelines.83

Japan-Russia Energy Ties84

With the exception of the Sakhalin projects, Japan and Japanese companies have had limited success in developing energy relationships with Russia. Japan, as the top natural gas customer in the world, gets about 10% of its LNG from Russia. Japanese firms—including Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and the SODECO consortium—are all minority stakeholders in various Sakhalin projects in both oil and gas. With energy prices soaring in the mid-2000s, the Kremlin asserted control and required that all projects be majority-controlled by state-owned companies Gazprom and Rosneft.85

Since the Fukushima nuclear reactor disaster following the earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, Japan's energy portfolio has transitioned to a dependence on fossil fuels without the steady source of nuclear power. Japan is particularly attracted to the environmental benefits of natural gas (compared to coal or oil), and is eager to import more LNG from the United States. Although Japanese companies remain wary, Japanese leaders may be trying to take a longer view and develop a stable supplier in Russia. Although Tokyo has largely kept its territorial issues with Moscow on a separate track from its energy relationship, the two have been increasingly intersecting as Japan looks to woo Russia. When Abe met with Putin in Sochi in May 2016, the Japanese side laid out an eight-part plan focusing on Japanese investment in the Russian Far East. A top Abe aide told the press that, "We, of course, believe that peace treaty negotiations and joint economic projects with Russia should be conducted in parallel."86

South Korea-Russia Energy Ties87

South Korea depends on imports for 97% of its energy, and is the ninth-largest consumer in the world. With no international gas or oil pipelines, it relies entirely on tankers to deliver its energy supplies and heavily depends on sources in the Middle East. After South Korea scaled back its crude oil imports from Iran due to pressure from the United States in 2012, Russia made up some of the difference. South Korea imports 4%-5% of its LNG and oil from Russia. Although South Korea did not impose sanctions on Russia following the crisis in Ukraine, Seoul officials claim that existing plans for projects with Russia, including those in the energy sector, were scaled back.88

With the Korean Peninsula contiguous with Eastern Russia, the potential for overland energy trade is vast, but the myriad strategic, logistical, and geographic challenges of North Korea make such plans difficult to implement (see "Korea-Russia Peninsula Relations" section). Over the years, a variety of plans for overland railways or pipelines that would deliver oil or gas to South Korea have been put forward, but they have always been ultimately stymied by the stubborn security situation on the Peninsula.

Issues for Congress

For Members of Congress, Russia's effort to develop stronger economic and security ties with the countries of Northeast Asia may be important because of the potentially significant impact on global geopolitics. In conducting oversight of foreign policy, Congress may request that the executive branch keep relevant committees closely informed of how Tokyo, Beijing, Seoul, and Pyongyang are responding to Moscow's overtures. In considering issues such as the North Korean nuclear problem, maritime challenges in the Pacific, global energy policy and politics, or the U.S. rebalance to Asia, Congress may give additional weight to how Russian involvement affects U.S. interests.

Russia's "Turn to the East" could impact several other areas that are of interest to Congress. One is the efficacy of U.S. sanctions policy on Russia given the lighter sanctions imposed on Russia by Japan and South Korea and China's attempt to broaden its economic cooperation with Russia. Another area that has been the subject of increased congressional interest is the development of the policy in the Arctic; Chinese and Russian competition in that region could affect whether additional U.S. military assets are necessary or desirable. Congress may also reconsider how enhanced Russian and Chinese cooperation at the United Nations could impact U.S. global interests.

Measures that Congress could consider include:

- Additional hearings by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, House Foreign Affairs Committee, Senate Armed Services Committee, or House Armed Services Committee to assess how Russia's efforts to upgrade relations with China, particularly its increase in military-to-military contacts, affect the U.S. security position in the Asia-Pacific.

- Formal requirements that the Departments of Defense and State include in their reporting to Congress assessments of how Russia is developing its relations with China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula.

- References in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to Russian activities that may alter the geopolitical environment in the Asia Pacific.

- Assessment of how existing sanctions on Russia are affected by U.S. allies' compliance with G-7 sanctions associated with the Ukraine crisis. Specifically, Congress may examine whether Japan and South Korea should strengthen restrictions on trade with Russia and how the U.S. State Department prioritizes this issue in relations with Seoul and Tokyo.

- Hearings, reporting requirements, and possible legislation on the U.S. position in the Arctic region and how changing security relations among Northeast Asia countries affect the U.S. presence and resources in the Arctic.

Appendix. Russia's Annexation of Crimea: Asian Response

After Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014, international condemnation was swift and widespread. At the United Nations, 100 countries voted for a resolution that supported Ukraine's territorial integrity and labeled the referendum invalid. Russia was suspended from the G8, and in April 2014 the remaining G7 members imposed sanctions on Russia. Among the Asian powers, only Japan and South Korea joined the Western countries in voting for the U.N. resolution, with only Japan imposing sanctions.

Tokyo has imposed a number of sanctions on Moscow, but they have been relatively weak compared to the ones implemented by other Western nations. Notably, Japan has not imposed any energy-sector-related sanctions. Tokyo has stated that it will not hold talks on the Northern Territories until the situation in Ukraine is more fully resolved. Abe also attempted to use Russia's annexation of Crimea to draw the international community's attention to China by arguing that Beijing might make similar moves with regard to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands.

South Korea's response was likely tied to Seoul's desire to obtain Moscow's cooperation on North Korea. South Korea refused to recognize Russia's annexation and voted "yes" for the U.N. resolution on Ukraine's territorial integrity, but chose not to impose any sanctions on Moscow.

China abstained from the U.N. vote and did not impose sanctions. China's response is motivated by Beijing's discomfort with the notion of states asserting independence through referendums as in the case of Crimea, and its stated ideological opposition to sanctions. China expressed discomfort with regard to Russia's annexation of Crimea, stating that "China always respects the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states. The Crimean crisis should be resolved politically under the frameworks of law and order." At the same time, China has noted Crimea's particular importance to Russia. While stating its clear opposition against independence through referendums, Beijing has decided to treat the Crimea case as an exception, perhaps seeing some parallels to China's own claims over Taiwan.

Likely in a bid to seek more international partners and escape isolation, North Korea has unequivocally supported Russia's position. North Korea was one of only 11 countries to vote "no" on the U.N. resolution affirming Ukraine's territorial integrity. The Kim regime also stated that Russia's annexation of Crimea was "fully justified."

Northeast Asian responses to Russia's annexation of Crimea are summarized as follows.

|

Vote on U.N. Resolution 68/262 Affirming the Territorial Integrity of Ukraine |

Sanctions |

|

|

Japan |

Yes |

Yes |

|

South Korea |

Yes |

No |

|

China |

Abstain, but made statements supporting the principle of territorial integrity. Considers Crimea a special case. |

No |

|

North Korea |

No. Unequivocally supports Russia. |

No. Clearly opposes. |

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sungtae "Jacky" Park for his contributions to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more, see CRS Report RL33460, Ukraine: Current Issues and U.S. Policy, by Vincent L. Morelli. |

| 2. |

Hans-Joachim Spanger, "Russia's Turn Eastward, China's Turn Westward: Cooperation and Conflict on the New Silk Road," Russia in Global Affairs, June 14, 2016. |

| 3. |