Mexico: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from May 2, 2019 to April 29, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- López Obrador Administration

- July 1, 2018, Election

- President López Obrador: Priorities and

Early ActionsApproach to Governing

- Security Conditions

- Corruption, Impunity, and Human Rights Abuses

- Corruption and the Rule of Law

- Human Rights

- Foreign Policy

- Economic and Social Conditions

- Factors Affecting Economic Growth

- Combating Poverty and Inequality

- U.S.-Mexican Relations and Issues for Congress

- Security Cooperation

: Transnational Crime and Counternarcotics - Department of Defense Assistance

- Extraditions

- Human Rights

- Economic and Trade Relations

- Trade Disputes

- The Proposed USMCA

- Extraditions

- Human Rights

- Migration and Border Issues

- Mexican-U.S. Immigration Issues

- Dealing with Unauthorized Migration, Including from Central America

- Modernizing the U.S.-Mexican Border

- Energy

- Water and Floodplain Issues

- Environment and Renewable Energy Policy

- Educational Exchanges and Research

- Structural Reforms: Enacted but Implemented Unevenly

- Bilateral Economic and Trade Ties

- NAFTA and the USMCA

- Energy

- Border Environmental Issues

- Water Resource Issues

- U.S.-Mexico Health Cooperation

- Outlook

Figures

- Figure 1. Mexico at a Glance

- Figure 2.

Presidential Election Results: 2012 vs. 2018 - Figure 3. Gubernatorial Control, by Party

- Figure

43. Estimated OrganizedCrime--Crime RelatedViolenceHomicides in Mexico - Figure

5. Proposed "Maya Train" Route4. Poppy Cultivation in Mexico

- Figure

65. Extraditions from Mexico to the United States:1998-20181999-2019

- Figure

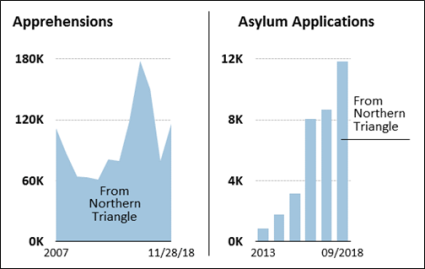

76. Mexico: Reported Apprehensions from Northern Triangle Countries and Asylum Applications

Tables

Summary

Congress has maintained significant interest in Mexico, an ally and top trade partner. In recent decades, U.S.-Mexican relations have grown closer through cooperative management of the 2,000-mile border, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and security and rule of law cooperation under the Mérida Initiative. Relations have been tested, however, by President Donald J. Trump's shifts in U.S. immigration and trade policies.

Mexico, the 10th most populous country globally, has the 15th largest economy in the world. It is currently the top U.S. trade partner and a major source of energy for the United States, with which it shares a nearly 2,000-mile border and strong economic, cultural, and historical ties. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the populist leader of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, which he created in 2014, took office for a six-year term in December 2018. López Obrador is the first Mexican president in over two decades to enjoy majorities in both chambers of Congress. In addition to combating corruption, he pledged to build infrastructure in southern Mexico, revive the poor-performing state oil company, address citizen security through social programs, and adopt a foreign policy based on the principle of nonintervention. President López Obrador's once high approval ratings have fallen from 60% in January 2020 to 47% in April, as Mexico faces organized crime-related violence, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and a recession. In 2019, Mexicans generally approved of the López Obrador government's new social programs and minimum wage increases, but many also viewed the cuts to government expenditures as wasteful. After Mexico encountered several high-profile massacres and record homicide levels, the López Obrador government came under U.S. and domestic pressure to improve its security strategy. Mexico's economy recorded zero growth in 2019, and the International Monetary Fund estimates that it may contract 6.6% in 2020. Nevertheless, President López Obrador has been slow to implement economic policies and public health measures to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and low oil prices on the country. U.S. PolicyOn December 1, 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the leftist Mérida Initiative Funding

Summary

populist leader of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) party, which he created in 2014, took office for a six-year term after winning 53% of votes in the July 1, 2018, presidential election. Elected on an anticorruption platform, López Obrador is the first Mexican president in over two decades to enjoy majorities in both chambers of Congress. López Obrador succeeded Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). From 2013-2014, Peña Nieto shepherded reforms through the Mexican Congress, including one that opened Mexico's energy sector to foreign investment. He struggled, however, to address human rights abuses, insecurity, and corruption.

President López Obrador has pledged to make Mexico a more just and peaceful society, but also to govern with austerity. Given fiscal constraints and rising insecurity, observers question whether his goals are attainable. López Obrador aims to build infrastructure in southern Mexico, revive the state oil company, promote social programs, and maintain a noninterventionist position in foreign affairs, including the crisis in Venezuela. His power is constrained, however, by MORENA's lack of a two-thirds majority in Congress, which he would need to enact constitutional reforms or to roll back reforms. Non-MORENA governors have also opposed some of his policies. Still, as of April 2019, López Obrador had an approval rating of78%.

U.S. Policy

Despite predictions to the contrary, U.S.-Mexico relations under the López Obrador government have thus far remained friendly. Nevertheless, tensions have emerged over several key issues, including trade disputes and tariffs, immigration and border security issues, and Mexico's decision to remain neutral in the crisis in Venezuela. The new government has accommodated U.S. migration and border security policies, despite the domestic criticism it has received for agreeing to allow Central American asylum seekers to await U.S. immigration proceedings in Mexico and for rapidly increasing deportations. The Trump Administration requested $76.3 million for the Mérida Initiative for FY2020 (a 35% decline from the FY2018-enacted level)U.S. citizens killed in Mexico, and Mexico's neutrality regarding the crisis in Venezuela. Security cooperation under the Mérida Initiative continues, but the Trump Administration has pushed Mexico to improve its antidrug efforts. The Mexican government has accommodated most of the Administration's border and asylum policy changes that have shifted the burden of interdicting migrants and offering asylum to Mexico. The Administration has requested $63.8 million in foreign aid for Mexico for FY2021.

In November 2018, Mexico, the United States, and Canada signed Legislative Action The 116th Congress consulted with the Trump Administration in the renegotiation of NAFTA under Trade Promotion Authority. The USMCA will replace NAFTA upon its entry into force. The House Democratic leadership recommended modifications to USMCA (on labor, the environment, and dispute settlement, among other topics) that led to changes to the agreement and a subsequent negotiation with Mexico and Canada on a USMCA protocol of amendment on December 10, 2019. The House approved USMCA implementing legislation in December 2019, and the Senate followed suit in January 2020 (P.L. 116-113). Both houses have taken action on H.R. 133, the United States-Mexico Economic Partnership Act, which directs the Secretary of State to enhance economic cooperation and educational and professional exchanges with Mexico; the House approved the measure in January 2019, and the Senate approved an amended version in January 2020. Congress provided $162.5 million in foreign assistance to Mexico in FY2019 (P.L. 116-6) and an estimated $157.9 million in FY2020 (P.L. 116-94). The FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92) required a classified assessment of drug trafficking, human trafficking, and alien smuggling in Mexico. a proposedthe U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) free trade agreement to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The López Obrador administration enacted labor reforms and raised wages to help secure U.S. congressional approval of the necessary implementing legislation. The USMCA is expected to enter into force on July 1, 2020.

Introduction

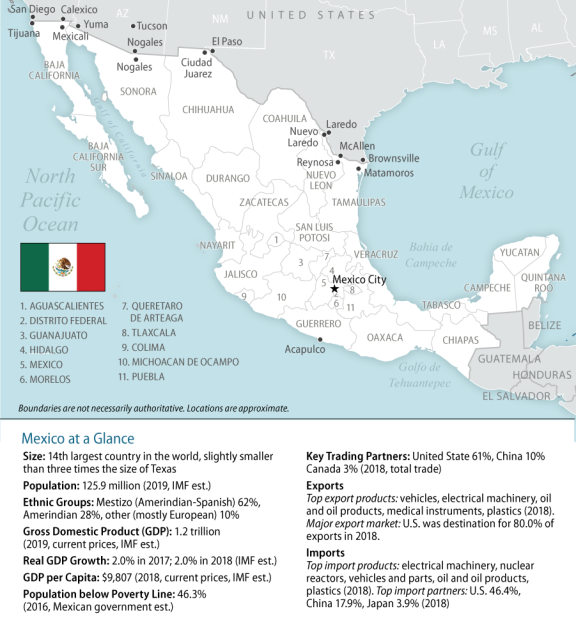

The 116th Congress has demonstrated renewed interest in Mexico, a neighboring country and top trading partner with which the United States has a close, but complicated relationship (see Figure 1). In recent decades, U.S.-Mexican relations have improved as the countries have become close trade partners and worked to address crime, the environment, and other issues of shared concern. Nevertheless, the history of U.S. military and diplomatic intervention in Mexico and the asymmetry in the relationship continue to provoke periodic tension.1

As the United States-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA), approved by Congress in January 2020, enters into force on July 1, 2020, its implementation is likely to receive congressional attention.2 Congress remains concerned about the effects of organized-crime-related violence in Mexico on U.S. security interests and U.S. citizens' safety in Mexico and has increased oversight of U.S.-Mexican security cooperation. Congress may appropriate foreign assistance for Mexico and oversee bilateral efforts to address U.S.-bound unauthorized migration, illegal drug flows, and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic U.S.-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) free trade agreement that, if approved by Congress and ratified by Mexico and Canada, would replace NAFTA. Mexico has applied retaliatory tariffs in response to U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports imposed in 2018.

Legislative Action

The 116th Congress may consider approval of the USMCA. Congressional concerns regarding the USMCA include possible effect on the U.S. economy, working conditions in Mexico and the protection of worker rights, enforceability of USMCA labor provisions, U.S.-Mexican economic relations, and other issues. It is not known whether or when Congress will consider implementing legislation for USMCA. In January 2019, Congress provided $145 million for the Mérida Initiative ($68 million above the budget request) in the FY2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-6) and asked for reports on how bilateral efforts are combating flows of opioids, methamphetamine, and cocaine. The House also passed H.R. 133 (Cuellar), a bill that would promote economic partnership between the United States and Mexico, as well as educational and professional exchanges. A related bill, S. 587 (Cornyn), has been introduced in the Senate.

Further Reading

CRS In Focus IF10578, Mexico: Evolution of the Mérida Initiative, 2007-2019.

CRS In Focus IF10400, Transnational Crime Issues: Heroin Production, Fentanyl Trafficking, and U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation.

CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts.

CRS Report R45489, Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions.

CRS Report RL32934, U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications.

CRS Report R44981, NAFTA Renegotiation and the Proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

CRS Report R45430, Sharing the Colorado River and the Rio Grande: Cooperation and Conflict with Mexico

Introduction

Congress has demonstrated renewed interest in Mexico, a top trade partner and energy supplier with which the United States shares a nearly 2,000-mile border and strong cultural, familial, and historical ties (see Figure 1). Economically, the United States and Mexico are interdependent, and Congress closely followed efforts to renegotiate NAFTA, which began in August 2017, and ultimately resulted in a proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) signed in November 2018. Similarly, security conditions in Mexico and the Mexican governments' ability to manage U.S.-bound migration flows affect U.S. national security, particularly at the Southwest border.

Five months into his six-year term, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador enjoys an approval ratings of 78%, even as his government is struggling to address rising insecurity and sluggish growth.1 Discontent with Mexico's traditional parties and voters' desire for change led them to elect López Obrador president with 53% of the vote. Some fear that López Obrador, whose National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) coalition captured legislative majorities in both chambers of the Congress, will reverse the reforms enacted in 2013-2014. Others predict that pressure from business groups, civil society, and some legislators and governors may constrain López Obrador's populist tendencies.

This report provides an overview of political and economic conditions in Mexico, followed by assessments of selected issues of congressional interest in Mexico: security and foreign aid, extraditions, human rights, trade, migration, energy, education, environmentwater, and water issuesenvironmental issues at the border.

Background

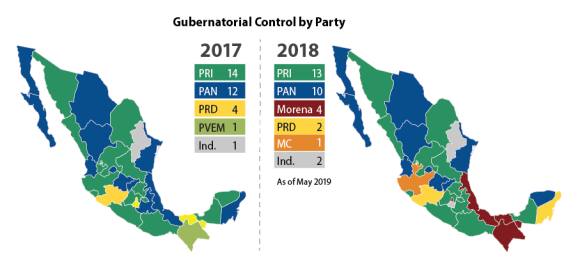

Over the past two decades, Mexico has transitioned from a centralized political system dominated by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which controlled the presidency from 1929-2000, to a true multiparty democracy.3 Since the 1990s, presidential power has become more balanced with that of Mexico's Congress and Supreme Court. Partially as a result of these new constraints on executive power, the country's first two presidents from the conservative National Action Party (PAN)—Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderón (2006-2012)—struggled to enact some of the reforms designed to address Mexico's economic and security challenges.

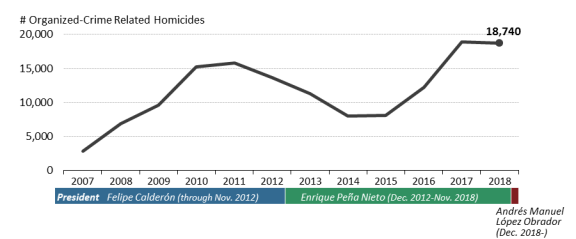

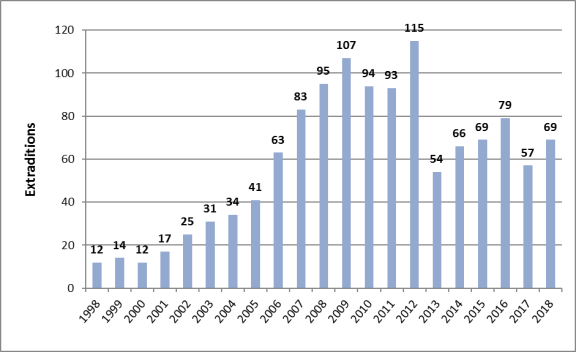

The Calderón government pursued an aggressive anticrime strategy and increased security cooperation with the United States. Mexico arrested and extradited many drug kingpins, but some 60,000 people died due to organized crime-related violence. Mexico's securitySecurity challenges overshadowed some of the government's achievements, including its economic stewardship during the global financial crisis, health care expansion and management of the H1N1 influenza pandemic, and efforts on climate change.4

In 2012, the PRI regained control of the presidency 12 years after ceding it to the PAN with a victory by Enrique Peña Nieto over López Obrador ofAndrés Manuel López Obrador, then standing for the leftist Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD). López Obrador then left the PRD and founded the MORENA party. Voters viewed the PRI as best equipped to reduce violence and hasten economic growth, despite concerns about its reputation for corruption. In 2013, Peña Nieto shepherded structural reforms through a fragmented legislature by forming a "Pact for Mexico" agreement among the PRI, PAN, and PRD. The reforms addressed a range of issues, including education, energyenergy, education, telecommunications, access to finance, and politics (see Table A-1 in the Appendix). The energy reform led to foreign oil and gas . The energy reform, which opened Mexico's energy sector to private investment, led to foreign companies committing to invest $160 billion in the country.2

|

|

Sources: Graphic created by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Map files from Map Resources. Trade data from Global Trade Atlas and Ethnicity data from CIA, The World Factbook. Other data are from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). |

Despite that early success, Peña Nieto left office with extremely low approval ratings (20% in November 2018) after presiding over a term that ended with record levels of homicides, moderate economic growth (averaging 2% annually), and pervasive corruption and impunity.3 Peña Nieto's approval rating plummeted after his government botched an investigation into the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero in September 2014.4 Reports that surfaced in 2014 of how Peña Nieto, his wife, and his foreign minister benefitted from ties to a firm that won lucrative government contracts, further damaged the administration's reputation.5 In 2017, reports emerged that the Peña Nieto government used spyware to monitor its critics, including journalists.6

López Obrador Administration

On July 1, 2018, Mexican voters gave López Obrador and MORENA a fairly strong mandate to change the course of Mexico's domestic policies.July 1, 2018, Election7

On July 1, 2018, Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his MORENA coalition dominated Mexico's presidential and legislative elections. Originally from the southern state of Tabasco, López Obrador is a 65-year-old , a former mayor of Mexico City (2000-2005) who ran, had run for president in the past two elections. After his loss in 20122012 loss, he left the center-left Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD)PRD and established MORENA.

MORENA, a leftist party, ran in coalition with the socially conservative Social Encounter Party (PES) and the leftist Labor Party (PT). López Obrador won 53.2% of the presidential vote, more than 30 percentage points ahead of his nearest rival, Ricardo Anaya, of the PAN/PRD/Citizen's Movement (MC) alliance who garnered 22.3% of the vote. López Obrador won in 31 of 32 states (see Figure 2). The PRI-led coalition candidate, José Antonio Meade, won 16.4% of the vote followed by Jaime Rodríguez, Mexico's first independent presidential candidate, with 5.2%.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador's victory signaled a significant change in Mexico's political development. López Obrador won in 31 of 32 states, demonstrating that he had broadened his support from his base in southern Mexico. The presidential election results have prompted soul-searching within the traditional parties and shown the limits of independent candidates. Anaya's defeat provoked internal struggles within the PAN. Meade's performance demonstrated voters' deep frustration with the PRI.

In addition to the presidential contest, all 128 seats in the Mexican senate and 500 seats in the chamber of deputies were up for election. Senators serve for six years, and deputies serve for three. Beginning this cycle, both senators and deputies will be eligible to run for reelection for a maximum of 12 years in office. MORENA's coalition won solid majorities in the Senate and the Chamber which convened on September 1, 2018. As of April 2019, the ruling coalition controls 70 of 128 seats in the Senate and 316 of 500 seats in the Chamber.8 The MORENA coalition lacks the two-thirds majority it needs to make constitutional changes or overturn reforms passed in 2013. The PAN is the second-largest party in each chamber.

|

|

|

Source: Graphic created by Congressional Research Service (CRS). Data from Mexico's National Electoral Institute |

Mexican voters gave López Obrador and MORENA a mandate to change the course of Mexico's domestic policies. Nevertheless, López Obrador's legislative coalition may face opposition if it seeks to enact policies that would shift the balance of power between federal and state offices. López Obrador proposed having a federal representative in each state to liaise with his office and to oversee distribution of all federal funds, but governors opposed this proposal. As shown in Figure 3, MORENA and allied parties control four of 32 governorships, including that of Mexico City.

President López Obrador: Priorities and Early Actions

Figure 2. Composition of the Mexican Congress by Party, as of April 2020

Source: CRS graphic, with information from the Mexican Chamber of Deputies, Mexican Senate.

As of April 2020, the ruling coalition, which includes MORENA, PT, PES, and the Green Party (PVEM), controls 77 of 128 seats in the Senate and 333 of 500 seats in the Chamber. The MORENA-led coalition has a two-thirds majority (needed to make constitutional changes) in the Chamber but not in the Senate. The PAN is the second-largest party in each chamber. Mexican voters gave López Obrador and MORENA a fairly strong mandate to change the course of Mexico's domestic policies.

President López Obrador: Priorities and Approach to GoverningIn 2018, López Obrador promised to bring about change by governing differently than recent PRI and PAN administrations. He focused on addressing voters' concerns about corruption, poverty and inequality, and escalating crime and violence.Although some of his advisers endorse progressive social policies, López Obrador personally has opposed abortion and gay marriage.9

López Obrador has In addition to combating corruption, he pledged to build infrastructure in southern Mexico, revive the poor-performing state oil company, address citizen security through social programs, and adopt a noninterventionist foreign policy. Given fiscal constraints, some observers questioned whether his goals were attainable. Although some of his advisers endorsed progressive social policies, López Obrador has opposed abortion and same-sex marriage.6

President López Obrador set high expectations for his government and promised many things to many different constituencies, some of which appear to conflict with each other. Upon taking office, López Obrador pledged to bring about a "fourth transformation" that would make Mexico a more just and peaceful society, but observers question whether his ambitious goals are attainable, given existing fiscal constraints. 10 As an example, he has promised to govern austerely but has started a number of new social programs. His finance minister has promised thatAs an example, he promised to govern austerely and bolster economic growth, but a lack of public (and private) investment has hurt the country's growth prospects. Although the López Obrador government promised to respect existing contracts with private energy companies will be respected, but his, the energy ministerministry has halted new auctions and is seeking to rebuild the heavily indebted state oil company (Petróleos de México or Pemex).11

President López Obrador's distinct brand of politics has given him broad support. 12 López Obrador has dominated the news cycle by convening daily, early morning press conferences. His decision to cut his own salary and public sector salaries generally have prompted high-level resignations among senior bureaucrats, but proven popular with the public. His government has started a new youth scholarship program and pensions for the elderly, while also promising to create jobs with infrastructure investments (including a new oil refinery and a railroad in the Yucatán) in southern Mexico regardless of their feasibility.13 Voters have given the government the benefit of the doubt even when its policies have caused inconveniences, such as fuel shortages that occurred after security forces closed some oil pipelines in an effort to combat theft.14

Investors have been critical of some of the administration's early actions. Many expressed concern after López Obrador cancelled a $13 billion airport project already underway after voters in a MORENA-led referendum rejected its location. Investors were somewhat assuaged, however, after the administration unveiled a relatively austere budget in late 2018 and then decided to allow energy contracts signed during Peña Nieto's presidency to proceed while halting new ones. With López Obrador's support, the Congress has enacted reforms to strengthen the protection of labor rights and workers' salaries, in part to comply with its domestic commitments related to the USMCA.15 On the other hand, it is unclear whether legislators' revisions will water down, or completely undo, education reforms passed in 2013 that were deemed a step forward toward raising education standards by many, but have been opposed by unions and ordered repealed by López Obrador.16

Critics maintain that President López Obrador has shunned reputable media outlets that have questioned his policies and cut funding for entities that could provide checks on his presidential power.17 He has dismissed data collected on organized crime-related violence by media outlets as "fake news" even as government data corroborate their findings that violence is escalating.18 His government has cut the budget for the national anticorruption commission, newly independent prosecutor general's office, and several regulatory agencies.

Security Conditions

Endemic violence, much of which is related to organized crime, has become an intractable problem in Mexico (see Figure 4). Organized crime-related violence has been fueled by U.S. drug demand, as well as bulk cash smuggling and weapons smuggling from the United States.19 Organized crime-related homicides in Mexico rose slightly in 2015 and significantly in 2016. In 2017, total homicides and organized crime-related homicides reached record levels.20 During Mexico's 2018 campaign, more than 150 politicians reportedly were killed.21 The homicide rate reached record levels in 2018 and rose even higher during the first three months of 2019 as fighting among criminal organizations intensified.22

Infighting among criminal groups has intensified since the rise of the Jalisco New Generation, or CJNG, cartel, a group that shot down a police helicopter in 2016. The January 2017 extradition of Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán prompted succession battles within the Sinaloa Cartel and emboldened the CJNG and other groups to challenge Sinaloa's dominance.23 Crime groups are competing to supply surging U.S. demand for heroin and other opioids. Mexico's criminal organizations also are fragmenting and diversifying away from drug trafficking, furthering their expansion into activities such as oil theft, alien smuggling, kidnapping, and human trafficking.24 Although much of the crime—particularly extortion—disproportionately affects localities and small businesses, fuel theft has become a national security threat, costing Mexico as much as $1 billion a year and fueling violent conflicts between the army and suspected thieves.25

(2007-2018) |

|

|

Source: Lantia Consultores, a Mexican security firm. Graphic prepared by CRS. |

Many assert that the Peña Nieto administration maintained Calderón's reactive approach of deploying federal forces—including the military—to areas in which crime surges rather than proactively strengthening institutions to deter criminality. These deployments led to a swift increase in human rights abuses committed by security forces (military and police) against civilians (see "Human Rights " below).26 High-value targeting of top criminal leaders also continued. As of August 2018, security forces had killed or detained at least 110 of 122 high-value targets identified as priorities by the Peña Nieto government; nine of those individuals received sentences.27 In August 2018, the Mexican government and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced a new bilateral effort to arrest the leader of the CJNG.28 Even as many groups have developed into multifaceted illicit enterprises, government efforts to seize criminal assets have been modest and attempts to prosecute money laundering cases have had "significant shortcomings."29

With violence reaching historic levels during the first quarter of 2019 and high-profile massacres occurring, President López Obrador is under increasing pressure to refine his security strategy.30 As a candidate, López Obrador emphasized anticorruption initiatives, social investments, human rights, drug policy reform, and transitional justice for nonviolent criminals. In line with those priorities, Mexico's security strategy for 2018-2024 includes a focus on addressing the socioeconomic drivers of violent crime.31 The administration has launched a program to provide scholarships to youth to attend university or to complete internships. Allies in the Mexican Congress are moving toward decriminalizing marijuana production and distribution.32

At the same time, President López Obrador has backed constitutional reforms to allow military involvement in public security to continue for five more years, despite a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that prolonged military involvement in public security violated the constitution.33 He secured congressional approval of a new 80,000-strong National Guard (composed of military police, federal police, and new recruits) to combat crime, a move that surprised many in the human rights community.34 After criticism from human rights groups, the Congress modified López Obrador's original proposal to ensure the National Guard will be under civilian command.

Corruption, Impunity, and Human Rights Abuses

Corruption and the Rule of Law

Corruption is an issue at all levels of government in Mexico: 84% of Mexicans identify corruption as among the most pressing challenge facing the country.35 In Mexico, the costs of corruption reportedly reach as much as 5% of gross domestic product each year.36 Mexico fell 33 places in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index from 2012 to 2018. At least 14 current or former governors (many from the PRI) are under investigation for corruption, including collusion with organized crime groups that resulted in violent deaths.37 A credible case against the chair of Peña Nieto's 2012 campaign (and former head of Pemex) for receiving $10.5 million in bribes from Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction firm, stalled after the prosecutor investigating the case was fired.38 Even though López Obrador has called for progress and transparency in anticorruption cases, his government has not unsealed information on investigations related to the Odebrecht case.39

President López Obrador has proven adept at connecting with his constituents but has struggled to adjust his priorities, even as Mexico faces a security crisis, recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Until recently, López Obrador had succeeded in shaping daily news coverage by convening frequent, early morning press conferences and traveling throughout the country to attend large, campaign-style rallies. He reportedly continued to hold large public events after public health officials warned of the dangers of COVID-19. Critics maintain that President López Obrador has shunned media outlets that have questioned his policies and cut funding for government entities that could check his presidential power.10 López Obrador has continued to support cuts in public sector salaries and ministry budgets, which have led to the resignations of senior bureaucrats and weakened public institutions, including the public health system. He remains committed to implementing large infrastructure projects—a new oil refinery and a train through the Yucatán—despite their fiscal unfeasibility and potential negative impacts on the environment and indigenous communities.11

2007-2019 Source: Lantia Consultores, a Mexican security firm. Graphic prepared by CRS. U.S. drug demand, as well as bulk cash smuggling and weapons smuggling into Mexico from the United States, have fueled drug trafficking-related violence in Mexico for over a decade. Recent violence may be attributed to competition for the production and trafficking of synthetic opioids, namely fentanyl.16 Journalists and mayors have experienced particularly high victimization rates, which has prompted concern about freedom of the press and criminal control over Mexican territory.17 In November 2019, drug traffickers killed nine women and children from an extended family of dual citizens of the United States and Mexico in Sonora, prompting significant concern from the Trump Administration and Congress.18 President López Obrador has rejected calls for a "war" on transnational criminal organizations, which he asserts would increase civilian casualties. Until recently, he also was hesitant to embrace the so-called "kingpin strategy," employed by his two predecessors, of arresting and extraditing top cartel leaders. López Obrador's security strategy, released in February 2019, included a focus on addressing the socioeconomic drivers of violent crime.19 The administration has launched a program to provide scholarships to youth to attend university or to complete internships rather than join criminal groups out of economic necessity. It has also discussed launching transitional justice programs for nonviolent offenders. The MORENA-led Congress is moving to decriminalize marijuana production and distribution (to comply with a 2018 Mexican Supreme Court ruling).20 At the same time, President López Obrador backed constitutional reforms to allow military involvement in public security to continue for five more years and created a military-led National Guard.21 Thus far, Mexico's National Guard (composed mostly of military and former federal police) has been tasked with reasserting territorial control in high-crime areas but also has been deployed to help detain migrants transiting through Mexico (at the behest of the U.S. government). More recently, it has been tasked with providing perimeter security and protecting medical supplies at hospitals serving COVID-19 patients.22 Since Mexico's National Guard lacks investigatory authority, evidence it gathers is inadmissible in court. Critics have therefore faulted the López Obrador administration for dismantling the U.S.-trained and equipped federal police and not adequately investing in the state and local police forces charged with investigating most crimes, including homicides.23 A fund previously dedicated to supporting local police reform efforts is being used to purchase protective health equipment for police working to combat rising crime amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.24 The López Obrador administration's security strategy appears to have shifted in recent months, after it received withering criticism following several massacres in fall 2019. Since the high-profile failure of an army-led operation to arrest El Chapo Guzmán's son (Ovidio Guzmán) in October 2019, the López Obrador administration has reportedly redeployed an elite navy unit that had previously tracked and arrested high-level kingpins, sometimes based on U.S. intelligence.25 The administration is reportedly in the process of developing a comprehensive drug control strategy. It has also resumed efforts to target, arrest, and extradite high-level kingpins to the United States (see "Extraditions," below). Corruption is an issue at all levels of government in Mexico and among all political parties. Twenty former governors (many from former president Peña Nieto's PRI party) are under investigation for corruption.26 In December 2019, the U.S. arrest of former PAN president Calderón's public security minister on charges of accepting millions in bribes from the Sinaloa Cartel revealed corruption at the highest levels of that administration.27 Although voters backed López Obrador for his perceived personal honesty and willingness to tackle corruption, some of his allies are suspected of malfeasance.28 President López Obrador has taken steps to combat corruption, but some observers question whether the administration will invest in the institutions necessary to effectively detect and address corrupt offenses. López Obrador's efforts to eliminate unnecessary government expenditures, including his decisions to cut his salary and fly commercial, and his announcements returning seized assets to the public coffers have won praise from some citizens. Others have dismissed them as merely symbolic actions.29 Some observers also worry that cuts in public sector salaries could make officials more susceptible to bribes. López Obrador's backing of constitutional reforms that added corruption to the list of grave crimes for which judges must require pre-trial detention also proved divisive. U.N. officials and others expressed concern that the move violates the principle that one is innocent until proven guilty and could encourage politicians to pressure judges to punish their political rivals.30 Key Institutions for Strengthening the Rule of LawNew Criminal Justice System. By the mid-2000s, most Mexican legal experts had concluded that reforming Mexico's corrupt and inefficient criminal justice system was crucial for combating criminality and strengthening the rule of law. In June 2008, Mexico implemented constitutional reforms mandating that by 2016, trial procedures at the federal and state levelgotten into a dispute with a major U.S.-led consortium drilling new wells in the country.7 López Obrador worked to secure the USMCA to assuage investors concerned about his economic policies but abandoned large infrastructure projects already underway, including a $13 billion Mexico City airport project, after voters in popular referendums rejected them.8 His government started a youth scholarship program, increased pensions for the elderly, and twice increased the minimum wage, while pledging not to raise taxes until at least 2021.9

40

31

Under Peña Nieto, Mexico technically met the June 2016 deadline for adopting the new system, with states that have received technical assistance from the United States showing, on average, better results than others.4132 Nevertheless, s problems in implementation occurred and public opinion turned against the system as many criminals were released by judges due to flawed police investigations by police and/or weak cases presented by prosecutors. 42 On average, fewer than 20% of homicides have been successfully prosecuted, suggesting persistently high levels of impunity.4333 According to the World Justice Project, the new system has produced better courtroom infrastructure, more capable judges, and faster case resolution than the old system, but additionalmore training for police and prosecutors is needed.44 It is unclear whether López Obrador will dedicate the resources necessary to strengthen the system.

Thus far, López Obrador has not dedicated significant resources to strengthening the justice system. His administration has implemented some reforms, including mandatory pre-trial detention for more types of crimes, which appear to contradict the goals of the new system. It also considered pushing other policies that would have weakened protections against police and prosecutorial abuses.35 Those policy changes were abandoned following a popular backlash.Reforming the Attorney34

For years, the PGR's efficiency has suffered because ofThe PGR has struggled with limited resources, corruption, and a lack of political will to resolve high-profile cases, including those involving high-level corruption or emblematic human rights abuses. Three attorneys general resigned from 2012 to 2017; the last one stepped down over allegations of corruption. Many civil society groups that pushed for the new criminal justice system in the mid-2000s also lobbied the Mexican Congress to create an independent prosecutor's office to replace the PGR.45.36 Under 2014 constitutional reforms adopted in 2014, Mexico's Senate would appointwas charged with appointing an independent individual to lead the new prosecutor general's office for a nine-year term.

.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador downplayed the importance of the new office during his presidential campaign, but Mexico's Congress established the office after he was inaugurated in December 2018. In January 2019, Mexico's Senate named Dr. Alejandro Gertz Manero, a 79-year oldclose associate and former security advisor to López Obrador, as prosecutor general. Despite the limited overall budget and institutional capacity of the newly created office, Gertz Manero has directed prosecutors to focus on emblematic cases. Still, critics maintain that Gertz Manero's ties to the president have inhibited his willingness to take on difficult cases, particularly those involving the current administration.37

National Anticorruption System. In July 2016, Mexico's Congress approved legislation that contained several proposals put forth by civil society to fully implement the national anticorruption system (NAS) created by a 2015 constitutional reform. The legislation associate and former security advisor to López Obrador, as Prosecutor General. Gertz Manero's nomination and subsequent appointment has raised concerns about his capacity to remain independent, given his ties to the president. Many wonder if he will take up cases against the president and his administration.46 Gertz Manero is to serve a nine-year term.

Making Electoral Fraud and Corruption Grave Crimes. In December 2018, López Obrador proposed constitutional changes that would expand the list of grave crimes for which judges must mandate pretrial detention to include corruption and electoral fraud. The proposal passed the Senate in December and the lower chamber in February 2019.47 Critics, such as the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), noted that the change violates the presumption of innocence, an international human right under the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Increasing pretrial detention also goes against one of the stated goals of the NCJS. The president, however, welcomed the outcome.

National Anticorruption System. In July 2016, Mexico's Congress approved legislation to fully implement the national anticorruption system (NAS) created by a constitutional reform in April 2015. The legislation reflected several of the proposals put forth by Mexican civil society groups. It gave the NAS investigative and prosecutorial powers and a civilian board of directors; increased administrative and criminal penalties for corruption; and required three declarations (taxes, assets, and conflicts of interest) from public officials and contractors.48 During Under the Peña Nieto government, federal implementation of the NAS lagged and state-level implementation varied significantly. In December 2017, members of the system's civilian board of directors maintained that the government had thwarted its efforts by denying requests for information.49

Although he campaigned on an anticorruption platform, President López Obrador has questioned the necessity of the NAS.50 Since taking office, López Obrador has not prioritized implementing the system. Nevertheless, Prosecutor General Gertz Manero named a special anticorruption prosecutor in February 2019. The 18 judges required to hear corruption cases are still to be named. In addition, many states have not fulfilled the constitutional requirements for establishing a local NAS.

Human Rights

In February 2019 Prosecutor General Gertz Manero named a special anticorruption prosecutor who received a significant budget for 2020 amidst generalized budget cuts for the institution. Cases involving corruption in the social development ministry and corrupt payments from the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht to the head of Petróleos de México (Pemex) during the Peña Nieto administration are moving forward. However, as of April 2020 President López Obrador has only nominated three of the judges required to hear corruption cases, and many states have not filled the positions needed to establish their state-level anti-corruption systems.39Criminal groups, sometimes in collusion with public officials, as well as state actors (military, police, prosecutors, and migration officials), have continued to commit serious human rights violations against civilians, including extrajudicial killings. 51 The vast majority of those abuses have gone unpunished, whether .38

prosecuted in the military or civilian justice systems.52 The government also continues to receive criticism for not adequately protecting journalists and, human rights defenders, migrants, and other vulnerable groups.

For years, human rights groups and the U.S. State Department's Country Reports on Human Rights Practices have chronicled cases of Mexican security officials' involvement in extrajudicial killings, "enforced disappearances," and torture.53 In October 2018, the outgoing Peña Nieto government estimated that more than 37,000 people who had gone missing since 2006 remained unaccounted for. States on the U.S.-Mexico border (Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Sonora) have among the highest rates of disappearances.54 The National Human Rights Commission estimates that "more than 3,900 bodies have been found in over 1,300 clandestine graves since 2007."55

|

Extrajudicial Killings, Enforced Disappearances, and Torture Two emblematic human rights cases have received international attention: Tlatlaya, State of Mexico. In October 2014, Mexico's National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) issued a report concluding that the Mexican military killed between 12 and 15 people in Tlatlaya on July 1, 2014. The military claimed that the victims were criminals killed in a confrontation. The CNDH also documented claims of the torture of witnesses to the killings by state officials. The last three soldiers in custody for killing eight people that day have been released, but four state prosecutors were convicted of torture. Concerns about the adequacy of the attorney general's investigation prompted a federal judge to order the case to be reopened in May 2018.56 Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. The unresolved case of 43 missing students who disappeared in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in September 2014—which allegedly involved the local police and authorities—galvanized global protests. The Peña Nieto government's investigation has been widely criticized, and experts from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) disproved much of its findings. The government worked with those experts to reinvestigate the case in 2015-April 2016 but denied their requests to interview soldiers who were in the area of the incident. In July 2016, the government formed a follow-up mechanism with the IACHR to help ensure follow up on the experts' lines of investigation, but it made little progress. In May 2018, a federal judge ruled that the attorney general's investigation had not been "impartial or independent" and called for the creation of a creation of a truth commission to take over the case.57 President López Obrador has established a truth commission to reinvestigate the case that will receive assistance from the United Nations. |

Among the human rights challenges facing Mexico, President López Obrador has prioritized enforced disappearances. The López Obrador administration has met regularly with families of the missing, launched an online portal for reporting missing persons, supported community-led searches, registered more than 3,600 clandestine graves, and increased the 2020 budget for Mexico's national search commission. Amidst what the interior ministry has deemed a "forensics crisis," the government is seeking international assistance, including U.S. support, to identify bodies that have been exhumed.44 In 2017, the Mexican Congress enacted a law againsttorture, and "enforced disappearances."42 The unresolved case of 43 missing students who disappeared in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, in September 2014—which allegedly involved the local police and authorities—galvanized global protests for the next four years. Experts from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) disproved much of the attorney general's investigation, and in 2018, a federal judge ruled that the attorney general's investigation had not been impartial. President López Obrador established a truth commission on Ayotzinapa, and Prosecutor General Gertz Manero created a special prosecutor's office to focus on the case. In March 2020, a federal judge issued arrest warrants for a former marine and five government officials for torture and obstruction of justice related to the case, a significant advance.43

" in Mexico and found the use of" and found torture to be "endemic" in detention centers.58 They also maintained that impunity for the crime of torture must be addressed: 4.6% of investigations into torture claims resulted in convictions.59

During a recent visit to Mexico, Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights recognized President López Obrador's efforts to put human rights at the center of his government. Bachelet highlighted the President's willingness to "unveil the truth, provide justice, give reparations to victims and guarantee the nonrepetition" of human rights violations. She commended the creation of the Presidential Commission for Truth and Access to Justice for the Ayotzinapa case and acknowledged the government's broader commitment to search for the disappeared. The commissioner welcomed the government's presentation of the Plan for the Implementation of the General Law on Disappearances (approved in 2017), the reestablishment of the National Search System, and the announcement of plans to create a Single Information System and a National Institute for Forensic Identification.60

In recent years, international observers have expressed alarm as Mexico has become one of the most dangerous countries for journalists to work outside of a war zone. From 2000 to 2018, some 120 journalists and media workers were killed in Mexico and many more have been threatened or attacked, according to Article 19 (an international media rights organization).61 A more conservative estimate from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is that 41 journalists have been killed in Mexico since 2000. In addition, Mexico ranks among the top 10 countries globally with the highest rates of unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of population in CPJ's Global Impunity Index.

Mexico is also a dangerous country for human rights defenders. During the first three months of the López Obrador government, at least 17 journalists and human rights defenders were killed, at least one of whom was receiving government protection.62 Although López Obrador has been critical of some media outlets and reporters, his government has pledged to improve the mechanism intended to protect human rights defenders and journalists.63

Foreign Policy

President Peña Nieto prioritized promoting trade and investment in Mexico as a core goal of his administration's foreign policy. During his term, Mexico began to participate in U.N. peacekeeping efforts and spoke out in the Organization of American States on the deterioration of democracy in Venezuela, a departure for a country with a history of nonintervention. Peña Nieto hosted Chinese Premier Xi Jinping for a state visit to Mexico, visited China twice, and in September 2017 described the relationship as a "comprehensive strategic partnership."64 The Peña Nieto government negotiated and signed the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement with other Asia-Pacific countries (and the United States and Canada). Even after President Trump withdrew the United States from the TPP agreement, Mexico and the 10 other signatories of the TPP concluded their own trade agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Mexico also prioritized economic integration efforts with the pro-trade Pacific Alliance countries of Chile, Colombia, and Peru and focused on expanding markets for those governments.65

In contrast to his predecessor, President López Obrador generally has maintained that the best foreign policy is a strong domestic policy. His foreign minister, Marcelo Ebrard (former mayor of Mexico City), is leading a return to Mexico's traditional, noninterventionist approach to foreign policy (the so-called Estrada doctrine). Many analysts predict, however, that Mexico may continue to engage on global issues that it deems important. López Obrador reversed the active role that Mexico had been playing during the Peña Nieto government in seeking to address the crises in Venezuela. Mexico has not recognized Juan Guaidó as Interim President of Venezuela despite pressure from the United States and others to do so. As of January 2019, U.N. agencies estimated that some 39,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees were sheltering in Mexico.66

Despite these changes, Mexico continues to participate in the Pacific Alliance, promote its exports and seek new trade partners, and support investment in the Northern Triangle countries (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras). The Mexican government has long maintained that the best way to stop illegal immigration from Central America is to address the insecurity and lack of opportunity there. Nevertheless, fiscal limitations limit the Mexican government's ability to support Central American efforts to address those challenges.

Economic and Social Conditions67

Mexico has transitioned from a closed, state-led economy to an open market economy that has entered into free trade agreements with 46 countries.68 The transition began in the late 1980s and accelerated after Mexico entered into NAFTA in 1994. Since NAFTA, Mexico has increasingly become an export-oriented economy, with the value of exports equaling more than 38% of Mexico's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016, up from 10% of GDP 20 years prior. Mexico remains a U.S. crude oil supplier, but its top exports to the United States are automobiles and auto parts, computer equipment, and other manufactured goods. Reports have estimated that 40% of the content of those exports contain U.S. value added content.69

Despite attempts to diversify its economic ties and build its domestic economy, Mexico remains heavily dependent on the United States as an export market (roughly 80% of Mexico's exports in 2018 were U.S.-bound) and as a source of remittances, tourism revenues, and investment. Studies estimate that a U.S. withdrawal from NAFTA, could cost Mexico more than 950,000 low-skilled jobs and lower its GDP growth by 0.9%.70 In recent years, remittances have replaced oil exports as Mexico's largest source of foreign exchange. According to Mexico's central bank, remittances reached a record $33.0 billion in 2018. Mexico remained the leading U.S. international travel destination in 2017 (the most recent year calculated by the U.S. Department of Commerce). U.S. travel warnings regarding violence in resort areas such as Playa del Carmen, Los Cabos, and Cancún could result in declining arrivals.71

The Mexican economy grew by 2% in 2018, but growth may decline to 1.6% in 2019, due, in part, to lower projected private investment.72 Mexico's Central Bank has also cited slowing investment, gasoline shortages, and strikes as reasons for revising its growth forecast for 2019 downward to a range of 1.1% to 2.1% for 2019.73 Some observers believe that investor sentiment and the country's growth prospects could worsen if López Obrador continues to promote government intervention in the economy and to rely on popular referendums to make economic decisions.74

Economic conditions in Mexico tend to follow economic patterns in the United States. When the U.S. economy is expanding, as it is now, the Mexican economy tends to grow. However, when the U.S. economy stagnates or contracts, the Mexican economy also tends to contract, often to a greater degree. The negative impact of protectionist U.S. trade policies and a projected U.S. economic slowdown in 2020 could hurt Mexico's growth prospects.75 President Trump has threatened to close the U.S.-Mexico border in response to his concerns about illegal immigration and illicit drug flows. Closing the border could have immediate and serious economic consequences. As an example, the U.S. auto industry stated that U.S. auto production would stop after a week due to the deep interdependence of the North American auto industry.76

Sound macroeconomic policies, a strong banking system, and structural reforms backed by a flexible line of credit with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have helped Mexico weather recent economic volatility.77 Nevertheless, the IMF has recommended additional steps to deal with potential external shocks. These steps include improving tax collection, reducing informality, reforming public administration, and improving governance.

Factors Affecting Economic Growth

Over the past 30 years, Mexico has recorded a somewhat low average economic growth rate of 2.6%. Some factors—such as plentiful natural resources, a young labor force, and proximity to markets in the United States—have been counted on to help Mexico's economy grow faster in the future. Most economists maintain that those factors could be bolstered over the medium to long term by continued implementation of some of the reforms described in Table A-1.

At the same time, continued insecurity and corruption, a relatively weak regulatory framework, and challenges in its education system may hinder Mexico's future industrial competitiveness. Corruption costs Mexico as much as $53 billion a year (5% of GDP).78 A lack of transparency in government spending and procurement, as well as confusing regulations and red tape, has likely discouraged some investment. Deficiencies in the education system, including a lack of access to vocational education, have led to firms having difficulty finding skilled labor.79

Another factor affecting the economy is the price of oil. Because oil revenues make up a large, if lessening, part of the country's budget (32% of government revenue in 2017), low oil prices since 2014 and a financial crisis within Pemex have proved challenging.80 The Peña Nieto government raised other taxes to recoup lost revenue from oil, but the López Obrador administration has pledged to make budget cuts in order to maintain fiscal targets.81

Many analysts predict that Mexico will have to combine efforts to implement its economic reforms with other actions to boost growth. A 2018 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development suggests that Mexico will need to enact complementary reforms to address issues such as corruption, weak governance, and lack of judicial enforcement to achieve its full economic growth potential.82

Combating Poverty and Inequality

Mexico has long had relatively high poverty rates for its level of economic development (43.6% in 2016), particularly in rural regions in southern Mexico and among indigenous populations.83 Some assert that conditions in indigenous communities have not measurably improved since the Zapatistas launched an uprising for indigenous rights in 1994.84 Traditionally, those employed in subsistence agriculture or small, informal businesses tend to be among the poorest citizens. Many households rely on remittances to pay for food, clothing, health care, and other basic necessities.

Mexico also experiences relatively high income inequality. According to the 2014 Global Wealth Report published by Credit Suisse, 64% of Mexico's wealth is concentrated in 10% of the population. Mexico is among the 25 most unequal countries in the world included in the Standardized World Income Inequality Database. According to a 2015 report by Oxfam Mexico, this inequality is due in part to the country's regressive tax system, oligopolies that dominate particular industries, a relatively low minimum wage, and a lack of targeting in some social programs.85

Human rights groups maintain that efforts to protect journalists, human rights defenders, and migrants remain insufficient, and in some cases, have worsened under López Obrador. Some 132 journalists and media workers were killed in Mexico from 2000 to 2019, including11 in 2019.46 Mexico ranks among the top 10 countries globally with the highest rates of unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of population, according to the nongovernmental Committee to Protect Journalists' Global Impunity Index. López Obrador has been critical of some media outlets and reporters who have questioned his policies; some of those reporters have subsequently been victims of physical attacks.47 Mexico is also a dangerous country for human rights defenders. In 2019, at least 23 human rights defenders were killed.48 Nevertheless, the López Obrador government has cut the budget for the already underfunded mechanism intended to protect human rights defenders and journalists and the budget for prosecutors charged with investigating those crimes. Migrants traveling through Mexico are vulnerable to abuse by criminal groups and corrupt officials. In June 2019, the López Obrador administration reached a migration agreement with the Trump Administration in order to avoid the imposition of U.S. tariffs.49 As part of that agreement, Mexico agreed to step up its immigration enforcement efforts and to allow more U.S.-bound migrants to be returned to Mexico to await their U.S. immigration proceedings. Since the June agreement took effect, violent incidents against migrants have increased in both southern and northern Mexico; human rights advocates have documented 800 cases of migrants returned to northern Mexico who have been raped, kidnapped, and/or attacked.50 In contrast to his predecessor, President López Obrador generally has maintained that the best foreign policy is a strong domestic policy and has not traveled outside the country since assuming office. Foreign minister Marcelo Ebrard (former mayor of Mexico City) has represented Mexico in global fora. He has been tasked with leading a return to Mexico's historic noninterventionist and independent approach to foreign policy (the so-called Estrada doctrine). As an example, López Obrador reversed the active role that Mexico had been playing during the Peña Nieto government in seeking to address the crises in Venezuela. Among other policy shifts, Mexico has established closer relations with Cuba, granted asylum to ousted Bolivian president Evo Morales, and discussed purchasing new helicopters from Russia after canceling a purchase of U.S. military helicopters in 2019.51 Despite these changes, Mexico continues to participate in multilateral institutions and support development in Central America. In addition to working within trade fora, such as the Pacific Alliance, Mexico continues to promote its exports and seek new trade partners.52 The López Obrador administration shares the view of prior Mexican governments that the best way to stop illegal immigration from the Northern Triangle of Central America (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) is to address the lack of opportunity and insecurity in that region. It has launched a $100 million program focused on promoting sustainable development in the Northern Triangle and signed agreements with the Trump Administration to bolster investment in the region.53 Beginning in the late 1980s, Mexico transitioned from a closed, state-led economy to an open market economy that has entered into free trade agreements with at least 46 countries. The transition accelerated after NAFTA's entry into force in 1994. Since NAFTA, Mexico has increasingly become an export-oriented economy, with the value of exports equaling 39% of Mexico's gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, up from 12% of GDP in 1993.55 Mexico remains a U.S. crude oil supplier, but its top exports to the United States are automobiles and auto parts, computer equipment, and other manufactured goods, many of which contain a significant percentage of U.S. value-added content. Over the past 30 years, Mexico has recorded a somewhat low average economic growth rate of 2.6%. Some factors—such as plentiful natural resources, a relatively young labor force, and proximity to markets in the United States—may help Mexico's economy growth prospects. At the same time, relatively weak institutions, an inefficient tax system, challenges in the education sector, and persistently high levels of informality (discussed below) may hinder Mexico's performance.56 A lack of transparency in government spending and procurement, confusing regulations, corruption, and high levels of insecurity remain barriers to investment.57 Despite attempts to diversify its economic ties and build its domestic economy, Mexico remains heavily dependent on the United States as an export market (roughly 85% of Mexico's exports in 2019 were U.S.-bound) and as a source of remittances, tourism revenues, and investment. Remittances, which reached a record $36 billion in 2019 according to Mexico's central bank, have replaced oil exports as Mexico's largest source of foreign exchange. Mexico remained the leading U.S. international travel destination in 2018 (the most recent year calculated by the U.S. Department of Commerce), despite U.S. travel warnings regarding violence in some resort areas. The total stock of U.S. foreign direct investment in Mexico stood at $114.9 billion in 2018, a 4.7% increase from 2017. When President López Obrador took office, he inherited an economy facing challenges but with strong fundamentals and an improving investment climate that had helped the country weather external volatility.58 Although the IMF renewed Mexico's flexible line of credit in November 2019, it expressed concerns about uncertainty in the administration's economic policymaking and unclear plans to generate the revenue necessary to offset additional spending.59 After growth averaging 3.0% since 2010, the Mexican economy contracted by 0.1% in 2019, due, in part, to lower public and private investment. Some investors have expressed serious concerns about López Obrador's promotion of government intervention in the economy, particularly support for Pemex and willingness to cancel major privately funded infrastructure projects opposed by his supporters.60 Some analysts had expected investment to increase this year as a result of the entry into force of the USMCA, which would offer some policy certainty to investors; those gains are unlikely to materialize due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Mexico's economy is particularly vulnerable to external volatility because of its strong reliance on export sectors. In its April 2020 World Economic Outlook, the IMF predicted that Mexico's economy would contract by some 6.6% in 2020 due to a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic, low oil prices and demand, and a likely U.S. recession.61 President López Obrador's responses to these phenomenon could worsen their combined impacts. As the peso has plunged, job losses have mounted, and investment flows have left the country, some observers are becoming increasingly concerned. Mexico has long had relatively high poverty rates for its level of economic development (41.6% in 2018 as compared to 44.4% in 2008), particularly in rural regions in southern Mexico and among indigenous populations.71 Traditionally, those employed in subsistence agriculture or in the informal sector tend to be among the poorest citizens. Many poor and working-class households rely on remittances from workers abroad to pay for food, clothing, health care, and other basic necessities and may be particularly hard hit this year as those remittances fall. Mexico also experiences relatively high income inequality. According to the 2019 Global Wealth Report published by Credit Suisse, 62.8% of Mexico's wealth is concentrated in 10% of the population, although that percentage declined from 66.7% in 2000. Inequality has historically been due, in part, to the country's regressive tax system, oligopolies that dominate particular industries, a relatively low minimum wage, and a lack of targeting in some social programs.72 Economists have maintained that reducing the untaxed and unregulated informal sector, in which workers lack job protections and benefits, is crucial for addressing income inequality and poverty, while also expanding Mexico's low tax base. Some of the reforms enacted in 2013-2014 sought to boost formal-sector employment and productivity, particularly among the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that employ some 60% of Mexican workers. To address the significant discrepancy in productivity between formal and informal sector firms, the financial reform aimed to increase access to credit for SMEs. The fiscal reform sought to incentivize SMEs' participation in the formal economy by offering insurance, retirement savings accounts, and home loans to those that register with the national tax agency. Despite those reforms, significant productivity differentials remain.73Economists have maintained that reducing informality is crucial for addressing income inequality and poverty, while also expanding Mexico's low tax base. The 2013-2014 reforms sought to boost formal-sector employment and productivity, particularly among the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that employ some 60% of Mexican workers, mostly in the informal sector. Although productivity in Mexico's large companies (many of which produce internationally traded goods) increased by 5.8% per year between 1999 and 2009, productivity in small businesses fell by 6.5% per year over the same period.86 To address that discrepancy, the financial reform aimed to increase access to credit for SMEs and the fiscal reform sought to incentivize SMEs' participation in the formal (tax-paying)45 The U.N. body also found that fewer than 5% of investigations into torture claims resulted in convictions. López Obrador has spoken out against torture, but his government has yet to develop a system to track statistics on torture cases as required by the 2017 law.

Combating Poverty and Inequality

economy by offering insurance, retirement savings accounts, and home loans to those that register with the national tax agency.

The Peña Nieto administration sought to complement economic reforms with social programs, but corruption within the Secretariat for Social Development likely siphoned significant funding away from some of those programs.87 It expanded access to federal pensions, started a national anti-hunger program, and increased funding for the country's flagship conditional cash transfer program.88 Peña Nieto renamed that program Prospera (Prosperity) and redesigned it to encourage its beneficiaries to engage in productive projects. 75 In addition to corruption, some of Peña Nieto's programs, namely the anti-hunger initiative, were criticized for a lack of efficacy.89

Despite his avowed commitment to austerity,reportedly were ineffective.76

President López Obrador has endorsed state-led economic development and promised to rebuild Mexico's domestic market as part of his National Development Plan 2018-2024, which he presented on May 1, 2019.90 In addition to revitalizing Pemex, the president has promised to build a "Maya Train". He has pledged to invest some $25 billion in southern Mexico, including a Mayan train to connect five states in the southeast and facilitateand promote tourism.77 Experts have dismissed the rail project and others he has proposed as financially and environmentally unfeasible, particularly now that the effects of COVID-19 are damaging the economy.78 tourism (see Figure 5). In December 2018, López Obrador announced a plan to invest some $25 billion in southern Mexico to accompany an estimated $4.8 billion in potential U.S. public and private investments to promote job growth, infrastructure, and development in that region, including jobs for Central American migrants.91

|

|

|

López Obrador's pledges related to social programs include (1) doubling monthly payments to the elderly; (2) providing regular financial assistance to a million disabled people; and (3) giving a monthly payment to 2.3 million youth ages 18-29 to stay in school or complete internships. 79 Some of these programs, combined with two minimum wage hikes, have improved people's socioeconomic conditions amidst a recession. Irregularities have already been detected, however, including within the youth scholarship program.80 Many development experts were concerned when López Obrador ended Prospera, a conditional cash payments program that had shown positive impacts on school attendance and nutrition outcomes and had been copied around the world.81

U.S.-Mexican (3) giving a monthly payment to students in 10th to 12th grades to lower the dropout rate, and (4) offering paid apprenticeships for 2.3 million young people. While some of these programs have already gotten underway, their ultimate scale and impacts will take time to evaluate. Some observers are concerned about his plan to decouple monthly support to families provided through the program formerly known as Prospera with requirements that children attend school and receive regular health checkup.92

U.S. Relations and Issues for Congress

Mexican-U.S. relations generally have grown closer over the past two decades. Common interests in encouraging trade flows and energy production, combating illicit flows (of people, weapons, drugs, and currency), and managing environmental resources have been cultivated over many years. A range of bilateral talks, mechanisms, and institutions have helped the Mexican and U.S. federal governments—as well as stakeholders in border states, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations—find common ground on difficult issues, such as migration and water management. U.S. policy changes that run counter to Mexican interests in one of those areas could trigger responses from the Mexican government on other areas where the United States benefits from Mexico's cooperation, such as combating illegal migration.93

Despite predictions to the contrary,

U.S.-Mexico relations under the López Obrador administration have thus far remained friendly. Nevertheless, periodic tensions have emerged over several key issues, including trade disputes and tariffs,; immigration and border security issues, and Mexico's decision to remain neutral in the crisis in Venezuela. The new government has generally accommodated U.S. migration and border security policies, but has protested recent policies that have resulted in extended border delays.94 President López Obrador has also urged the U.S. Congress to consider the USMCA.95

Security Cooperation: Transnational Crime and Counternarcotics96

Mexico is a significant source and transit country for heroin, marijuana, and synthetic drugs (such as methamphetamine) destined for the United States. It is also a major transit country for cocaine produced in the Andean region.97 Mexican-sourced heroin now accounts for nearly 90% of the total weight of U.S.-seized heroin analyzed in the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA's) Heroin Signature Program. In addition to Mexico serving as a transshipment point for Chinese fentanyl (a powerful synthetic opioid), the DEA suspects labs in Mexico may use precursor chemicals smuggled over the border from the United States to produce fentanyl.

Mexican drug trafficking organizations pose the greatest crime threat to the United States, according to the DEA's 2018including President Trump's determination to construct a border wall; and the adequacy of Mexico's antidrug efforts, among other topics.82 Under López Obrador, Mexico has accommodated increasingly restrictive U.S. immigration and border security policies, possibly to achieve one of its top foreign policy priorities: U.S. approval of the USMCA. As the USMCA enters into force in July 2020, bilateral relations may pivot to other issues, including how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Security Cooperation, Counternarcotics, and U.S. Foreign Aid83

As a primary source of and transit country for illicit drugs destined for the United States, Mexico plays a key role in U.S. drug control policy. Mexico is a significant source country for heroin, marijuana, and synthetic drugs (such as methamphetamine and fentanyl) destined for the United States. Opium poppy cultivation and heroin production have surged in Mexico since 2013 (see Figure 4 below). Mexico is also a major transit country for cocaine produced in the Andean region of South America and for fentanyl from China.

Mexican drug trafficking organizations continue to pose the greatest criminal threat to the United States, according to the DEA's 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment. These organizations engage in drug trafficking, money laundering, and other violent crimes. They traffic heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, marijuana, and, increasingly, the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl.

Figure 4. Poppy Cultivation in Mexico

Sources: Graphic created by CRS using data from the Office of National Drug Control Policy (2019), State Department (2017), Esri (2014), and DeLorme (2014).