Climate Change: Frequently Asked Questions About the 2015 Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (PA) to address climate change internationally entered into force on November 4, 2016. The United States is one of 149 Parties to the treaty; President Barack Obama accepted the agreement rather than ratifying it with the advice and consent of the Senate. On June 1, 2017, President Donald J. Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the agreement and that his Administration would seek to reopen negotiations on the PA or on a new “transaction.” Following the provisions of the PA, U.S. withdrawal could take effect as early as November 2020.

Experts broadly agree that stabilizing greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere to avoid dangerous GHG-induced climate change would require concerted efforts by all large emitting nations. The United States is the second largest emitter of GHG globally after China. Toward this purpose, the PA outlines goals and a structure for international cooperation to slow climate change and mitigate its impacts over decades to come.

The PA is subsidiary to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which the United States ratified in 1992 with the advice and consent of the Senate and which entered into force in 1994. The PA requires that nations submit pledges to abate their GHG emissions, set goals to adapt to climate change, and cooperate toward these ends, including mobilization of financial and other support. The negotiators intended the PA to be legally binding on its Parties, though not all provisions in it are mandatory. Some are recommendations or collective commitments to which it would be difficult to hold an individual Party accountable. Key aspects of the agreement include:

Temperature goal. The PA defines a collective, long-term objective to hold the GHG-induced increase in temperature to well below 2o Celsius (C) and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5o C above the pre-industrial level. A periodic “global stocktake” will assess progress toward the goals.

Single GHG mitigation framework. The PA establishes a process, with a ratchet mechanism in five-year increments, for all countries to set and achieve GHG emission mitigation pledges until the long-term goal is met. For the first time under the UNFCCC, all Parties participate in a common framework with common guidance, though some Parties are allowed flexibility in line with their capacities. This largely supersedes the bifurcated mitigation obligations of developed and developing countries that held the negotiations in often-adversarial stasis for many years.

Accountability framework. To promote compliance, the PA balances accountability to build and maintain trust (if not certainty) with the potential for public and international pressure (“name-and-shame”). Also, the PA establishes a compliance mechanism that will be expert-based and facilitative rather than punitive. Many Parties and observers will closely monitor the effectiveness of this strategy.

Adaptation. The PA also requires “as appropriate” that Parties prepare and communicate their plans to adapt to climate change. Adaptation communications will be recorded in a public registry.

Collective financial obligation. The PA reiterates the collective obligation in the UNFCCC for developed country Parties to provide financial resources—public and private—to assist developing country Parties with mitigation and adaptation efforts. It urges scaling up of financing. The Parties agreed to set, prior to their 2025 meeting, a new collective quantified goal for mobilizing financial resources of not less than $100 billion annually to assist developing country Parties.

Obama Administration officials stated that the PA is not a treaty requiring Senate advice and consent to ratification. President Obama signed an instrument of acceptance on behalf of the United States on August 29, 2016, without submitting it to Congress. In 2015, Members of the 114th Congress introduced several resolutions (e.g., S.Res. 329, S.Res. 290, H.Res. 544, S.Con.Res. 25) to express the sense that the PA should be submitted for the advice and consent of the Senate. Additionally, resolutions were introduced in the House (H.Con.Res. 97, H.Con.Res. 105,H.Res. 218) to oppose the PA or set conditions on its signature or ratification by the United States. None received further action. In the 115th Congress, a number of resolutions have also been introduced to oppose or support U.S. participation in the PA (e.g., H.Con.Res. 55, H.Res. 85, H.Res. 390, S.Con.Res. 17).

Beyond the Senate’s role in giving advice and consent to a treaty, Congress continues to exercise its powers through authorizations and appropriations for related federal actions. Additionally, numerous issues may attract congressional oversight, such as:

procedures for withdrawal;

foreign policy, technological, and economic implications of withdrawal;

possible objectives and provisions of renegotiation of the PA or of a new “transaction” for cooperation internationally;

international rules and guidance to carry out the PA;

financial contributions and uses of finances mobilized; and

assessment of the effectiveness of other Parties’ efforts.

Climate Change: Frequently Asked Questions About the 2015 Paris Agreement

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- The Paris Agreement in Context

- Introduction

- What is the relationship of the PA to the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol?

- What are some key policy takeaways from Paris?

- Requirements and Recommendations in the PA

- What is the purpose and long-term goal of the PA?

- What does the PA require?

- Is the PA legally binding?

- Are PA requirements new for some Parties?

- What are the financial obligations, if any, for the United States in the PA?

- What is the role of the Green Climate Fund in the PA?

- Does the PA address "Loss and Damage"?

- Does the PA include or allow market-based mechanisms to reduce GHG emissions?

- What gases and sectors does the PA cover?

- Procedural Topics

- How did the PA enter into force?

- Signatures

- Deposits of Instruments of Ratification, Acceptance, Approval, or Accession

- What actions did the United States take to join the PA?

- Can a Party withdraw from the PA?

- What are the roles of Congress with respect to the UNFCCC and the PA?

- Countries' Pledges to Contribute to GHG Emission Mitigation

- What did the United States pledge as its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to global GHG mitigation?

- Could a Party rescind its NDC and submit a new one?

- Can the United States meet its 2025 GHG reduction pledge?

- What did other major GHG-emitting countries pledge as their INDCs?

- What if a Party does not meet its pledge?

- What effect might full compliance with the PA have on climate change?

- Next Steps for the PA

- Tasks for all Parties

- Questions About Next Steps for the United States

Figures

Summary

The Paris Agreement (PA) to address climate change internationally entered into force on November 4, 2016. The United States is one of 149 Parties to the treaty; President Barack Obama accepted the agreement rather than ratifying it with the advice and consent of the Senate. On June 1, 2017, President Donald J. Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the agreement and that his Administration would seek to reopen negotiations on the PA or on a new "transaction." Following the provisions of the PA, U.S. withdrawal could take effect as early as November 2020.

Experts broadly agree that stabilizing greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations in the atmosphere to avoid dangerous GHG-induced climate change would require concerted efforts by all large emitting nations. The United States is the second largest emitter of GHG globally after China. Toward this purpose, the PA outlines goals and a structure for international cooperation to slow climate change and mitigate its impacts over decades to come.

The PA is subsidiary to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which the United States ratified in 1992 with the advice and consent of the Senate and which entered into force in 1994. The PA requires that nations submit pledges to abate their GHG emissions, set goals to adapt to climate change, and cooperate toward these ends, including mobilization of financial and other support. The negotiators intended the PA to be legally binding on its Parties, though not all provisions in it are mandatory. Some are recommendations or collective commitments to which it would be difficult to hold an individual Party accountable. Key aspects of the agreement include:

- Temperature goal. The PA defines a collective, long-term objective to hold the GHG-induced increase in temperature to well below 2o Celsius (C) and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5o C above the pre-industrial level. A periodic "global stocktake" will assess progress toward the goals.

- Single GHG mitigation framework. The PA establishes a process, with a ratchet mechanism in five-year increments, for all countries to set and achieve GHG emission mitigation pledges until the long-term goal is met. For the first time under the UNFCCC, all Parties participate in a common framework with common guidance, though some Parties are allowed flexibility in line with their capacities. This largely supersedes the bifurcated mitigation obligations of developed and developing countries that held the negotiations in often-adversarial stasis for many years.

- Accountability framework. To promote compliance, the PA balances accountability to build and maintain trust (if not certainty) with the potential for public and international pressure ("name-and-shame"). Also, the PA establishes a compliance mechanism that will be expert-based and facilitative rather than punitive. Many Parties and observers will closely monitor the effectiveness of this strategy.

- Adaptation. The PA also requires "as appropriate" that Parties prepare and communicate their plans to adapt to climate change. Adaptation communications will be recorded in a public registry.

- Collective financial obligation. The PA reiterates the collective obligation in the UNFCCC for developed country Parties to provide financial resources—public and private—to assist developing country Parties with mitigation and adaptation efforts. It urges scaling up of financing. The Parties agreed to set, prior to their 2025 meeting, a new collective quantified goal for mobilizing financial resources of not less than $100 billion annually to assist developing country Parties.

Obama Administration officials stated that the PA is not a treaty requiring Senate advice and consent to ratification. President Obama signed an instrument of acceptance on behalf of the United States on August 29, 2016, without submitting it to Congress. In 2015, Members of the 114th Congress introduced several resolutions (e.g., S.Res. 329, S.Res. 290, H.Res. 544, S.Con.Res. 25) to express the sense that the PA should be submitted for the advice and consent of the Senate. Additionally, resolutions were introduced in the House (H.Con.Res. 97, H.Con.Res. 105,H.Res. 218) to oppose the PA or set conditions on its signature or ratification by the United States. None received further action. In the 115th Congress, a number of resolutions have also been introduced to oppose or support U.S. participation in the PA (e.g., H.Con.Res. 55, H.Res. 85, H.Res. 390, S.Con.Res. 17).

Beyond the Senate's role in giving advice and consent to a treaty, Congress continues to exercise its powers through authorizations and appropriations for related federal actions. Additionally, numerous issues may attract congressional oversight, such as:

- procedures for withdrawal;

- foreign policy, technological, and economic implications of withdrawal;

- possible objectives and provisions of renegotiation of the PA or of a new "transaction" for cooperation internationally;

- international rules and guidance to carry out the PA;

- financial contributions and uses of finances mobilized; and

- assessment of the effectiveness of other Parties' efforts.

The Paris Agreement in Context

Introduction

Debate continues in the United States over whether and how the federal government should address human-related climate change. A large majority of scientists and governments accept that stabilizing the concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere and avoiding further GHG-induced climate change would require concerted effort by all major emitting countries.1 Toward this end, 195 governments attending the 21st Conference of Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Paris, France, adopted an agreement in 2015 outlining goals and a structure for international cooperation to address climate change and its impacts over decades to come.2 The "Paris Agreement" (PA) is subsidiary to the UNFCCC, a treaty that the United States ratified with the advice and consent of the Senate3 and that entered into force in 1994.4

The PA entered into force on November 4, 2016, 30 days after at least 55 countries representing at least 55% of officially reported global GHG emissions had deposited their instruments. On behalf of the United States, President Obama signed an instrument of acceptance of the PA on August 29, 2016, and deposited it with U.N. Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon on September 3, 2016. As of April 1, 2017, 142 additional nations have become Parties.

On June 1, 2017, President Donald Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the PA.5 He also stated that his Administration would seek to reopen negotiations on the PA or on a new "transaction." As discussed later, a Party may withdraw from the PA if it chooses to do so. Article 28 allows a Party to give written notice of withdrawal to the U.N. depositary after three years from the date on which the agreement has entered into force for that Party. The withdrawal could take effect one year later. The United States could give notice of withdrawal as soon as November 4, 2019, with withdrawal taking effect as soon as November 4, 2020. The President did not indicate how the United States might participate in PA procedures until withdrawal should take effect.

The PA creates a structure for nations to pledge to abate their GHG emissions, adapt to climate change, and cooperate toward these ends, including financial and other support. The PA is intended to be legally binding on Parties, though not all provisions are mandatory. The Parties in Paris also adopted a Decision to help implement the PA, and the specified processes to define rules, methods, and other tasks are underway.

Members of Congress have expressed diverse views about the PA and may have questions about its content, process, and obligations. This report is intended to answer some of the primary factual and policy questions about the PA and its implications for the United States. It touches on nearly all of the 29 articles in the 16-page agreement, as well as some in the accompanying decision of the Parties to give effect to the PA. Other CRS products, available by request or on the CRS website, may provide additional or deeper information on specific questions.6

|

The UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement The UNFCCC is a "framework" or "umbrella" treaty.7 That is, Parties established an objective and general obligations in the UNFCCC aimed at achieving its objective: The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.8 Governments anticipated that the UNFCCC would require subsequent decisions, annexes, protocols, or other agreements in order to achieve that objective. The first subsidiary agreement to the UNFCCC was the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which entered into force in 2005. The United States signed but did not ratify the Kyoto Protocol and so is not a Party to it. The Kyoto Protocol established legally binding targets for 37 high-income countries and the European Union (EU) to reduce their GHG emissions on average by 5% below 1990 levels during 2009-2012. It precluded GHG mitigation obligations for developing countries. Most of the high-income Parties took on further targets for 2013-2020. The United States and a number of other countries ultimately viewed the Kyoto Protocol as an unsuitable instrument for long-term cooperation because it excluded GHG mitigation commitments from developing countries. The PA is the second major subsidiary agreement under the UNFCCC. Many stakeholders expect the PA to eventually replace the Kyoto Protocol as the primary subsidiary vehicle for process and actions under the UNFCCC. No agreed vision for a transition from the Kyoto Protocol to the PA has been articulated, though some Parties have urged that PA implementation take advantage of existing processes and rules of the Kyoto Protocol that have proven successful. |

What is the relationship of the PA to the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol?

The UNFCCC is a "framework" treaty. (See text box.) The PA is subsidiary to the UNFCCC, meaning that it is understood to exist within the scope and terms of the UNFCCC. As such, only Parties to the UNFCCC are eligible to become Parties to the PA (PA Article 20.1).9

The PA is the outcome of the so-called Durban Mandate: The Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC agreed at its 2011 meeting in Durban, South Africa, "to develop a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties,"10 which could be adopted by the COP in December 2015 and come into effect and be implemented by 2020.

The PA may take advantage of many rules and processes that currently support Parties' implementation of their UNFCCC obligations (e.g., to submit and review national GHG inventories). UNFCCC processes will continue in parallel with new ones under the PA unless Parties modify them. In developing implementation of the PA, the Parties may elect to make use of existing UNFCCC or Kyoto Protocol processes and agreed rules—such as to promote adaptation to climate change or to account for emissions from land use change—rather than beginning new ones. Some processes may be streamlined or merged under the related agreements.

|

Abbreviations for Key UNFCCC Decisionmaking Bodies COP: The Parties to the UNFCCC, as a body, are referred to as the "Conference of the Parties" (COP). It remains the supreme decisionmaking body of the treaty. CMA: The Parties to the PA will collectively be called the "Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the PA", or CMA. APA: To prepare for the first CMA, the PA established the "Ad Hoc Working Group on the PA" (APA) to develop guidance, processes, and recommendations for the CMA's consideration and adoption. |

What are some key policy takeaways from Paris?

While the PA is only 16 pages long, it contains a number of complex mechanisms—many of which will require further definition by the negotiating Parties. Some experts and observers, noting the PA's largely procedural nature and lack of binding quantitative GHG obligations, have questioned whether the PA marks significant change. Others note a number of substantive differences from prior commitments, specifically for some Parties. Below are several ways in which the PA embodies change under the UNFCCC.

- Common process for all Parties. For the first time under the UNFCCC, all Parties will participate in a common framework with common guidance, although some Parties will have flexibility in line with their capacities. The commonality largely supersedes the bifurcation into wealthier and developing countries that has held the negotiations in often-adversarial stasis for many years.

- Ratcheting process toward quantified objective. The PA defines a quantitative (though collective) long-term objective to hold the GHG-induced increase in temperature to well below 2o Celsius (C) and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5oC above the pre-industrial level. The PA establishes a process, with a "ratchet mechanism" in five-year increments, for countries to set and achieve GHG abatement targets until the long-term goal is met.

- Greater subsidiarity. The PA embodies greater decentralization than, for example, the Kyoto Protocol.11 The PA increases reliance on decisionmaking and strategy by individual countries or countries cooperating among themselves, not necessarily through central decision mechanisms. Examples of subsidiarity include

- the nationally determined contributions (pledges) that set countries' GHG targets, and

- recognition that Parties will use market-based mechanisms (e.g., emissions trading) to transfer emission reduction credits to meet their commitments.12

- Growing role of non-state entities. The negotiations leading to the Paris conference and the PA grew more inclusive of non-state entities (including the private sector) as observers and influencers. Parties recognized them as key decisionmakers and implementers of activities expected to be necessary to achieve the GHG abatement and increased resilience to climate change envisioned in the PA. The government of France established a website for non-state actors to make pledges and share information.

- Moderate compliance incentives for all. For the first time, all countries agreed to a single system for transparency, accountability, and public accessibility to emissions and policy information to promote compliance with the PA. The UNFCCC lacks universal obligations for transparency and review; the Kyoto Protocol's more intrusive non-compliance provisions may have discouraged participation in commitments by some Parties. To promote compliance, the PA works to balance accountability necessary to build and maintain trust (if not certainty) with the potential for public and international pressure ("name-and-shame"). A compliance mechanism is defined to be expert-based and facilitative rather than punitive. Many Parties and observers will closely monitor the effectiveness of this strategy.

Requirements and Recommendations in the PA

What is the purpose and long-term goal of the PA?

The PA states its purpose in Article 2: to enhance implementation of the UNFCCC and "to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change." Parties to the UNFCCC adopted the PA "in pursuit of the objective of the Convention"13—to stabilize GHG concentrations in the atmosphere at a level to avoid dangerous anthropogenic interference in the climate system.14

|

GHG Increases and Global Average Temperature Increases There is strong scientific agreement that climate change is occurring and that human activities—especially carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas)—are responsible for most of the climate change observed since the 1950s. Further human-related GHG emissions, and their accumulation in rising atmospheric concentrations, would induce further climate change and would pose significant risks for many human and natural systems.15 The amount of global average temperature increase induced by rising GHG emissions is understood only within a wide range, and the higher temperature end of that range is not well constrained by observational evidence. There is broad—though not universal—scientific agreement that a doubling of pre-industrial CO2 concentrations (from 280 parts per million) would likely result in global average warming of 1.5-4.5oC (2.7-8.1oF) over multiple centuries.16 (Current CO2 concentrations, not including other GHG, exceed 400 ppm globally.) From a geologic perspective, a temperature increase in this range would be a large and rapid change in the earth's system. For a comparison of magnitudes, a multi-researcher analysis estimated a temperature difference of approximately 3-5oC between the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheets were at their maximum extent—about 21,000 years ago—and the pre-industrial surface global mean temperature.17 |

Although stabilizing GHG concentrations would require eventually reducing human-related net emissions to near zero, the UNFCCC did not state when or at what levels stabilization should occur. The levels at which GHG atmospheric concentrations stabilize ultimately determines the degree of GHG-induced temperature change.

The PA quantifies the intent of Parties in this regard in Article 2, stating that it aims to

[hold] the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.

Article 2 also calls for, inter alia, increasing the ability to adapt to climate change and making financial flows consistent with a pathway toward low GHG emissions and climate-resilient development.

In order to achieve the PA's "long-term temperature goal," Parties aim to make their GHG emissions peak as soon as possible and then reduce them rapidly "so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century."18 In other words, the PA envisions achieving net zero anthropogenic GHG emissions within a defined time period. While this is arguably synonymous with the UNFCCC's objective of stabilizing GHG atmospheric concentrations, the PA puts a time frame on the objective for the first time. The objective, however, is collective. It remains unclear whether the PA could hold an individual Party accountable if the collective objective were not met.

What does the PA require?

The PA establishes a single framework under which all Parties shall:

- communicate every five years and undertake Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to mitigate GHG emissions, reflecting the "highest possible ambition";

- participate in a single "transparency framework" that includes communicating Parties' GHG inventories and implementation of their obligations—including financial support provided or received—not less than biennially (with exceptions to a few least-developed states); and

- be subject to international review of their implementation.

The requirements are procedural. There are no legal targets and timetables for reducing GHG emissions.

All Parties will eventually be subject to common procedures and guidelines. However, developed country Parties19 should provide NDCs stated as economy-wide, absolute GHG reduction targets, while developing country Parties are exhorted to enhance their NDCs and move toward similar targets over time in light of their national circumstances. Further flexibility in the transparency framework is allowed to developing countries (depending on their capacities) regarding the scope, frequency, and detail of their reporting. Many observers consider this flexibility key to gaining the participation of many low-income countries, while some observers note that the flexibility may allow reticent Parties to resist more stringent commitments.20 The administrative Secretariat of the UNFCCC will record the NDCs and other key reports in a public registry.

The PA also requires "as appropriate" that Parties prepare and communicate their plans to adapt to climate change. Adaptation communications, too, will be recorded in a public registry.

The PA reiterates the obligation in the UNFCCC for developed country Parties to provide public and private financial support to assist developing country Parties with mitigation and adaptation efforts. It also urges scaling up of financing. The Parties agreed to set, prior to their 2025 meeting, a new collective quantified goal for mobilizing financial resources of not less than $100 billion annually to assist developing country Parties.21 Financing is not restricted to public funds, and many stakeholders expect that most would flow through private investment.

The PA permits Parties to participate in cooperative approaches (implicitly, emissions markets) that "involve the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes." Additional mechanisms for cooperative activities, and efforts to incentivize private sector participation, are identified.

Further, the PA establishes a committee that will address compliance issues under the PA in a facilitative and non-punitive manner. Finally, the PA contains provisions for voluntary withdrawal by Parties.

Is the PA legally binding?

The Department of State in 2016 communicated to Congress that, in its view, some elements of the PA are legal and binding: "Once the Agreement enters into force for the United States, the legally binding provisions of the Agreement … will apply to the United States."22

Negotiators intended the PA to be a legal instrument, though not all provisions in it are mandatory. Some are recommendations or collective commitments to which it would be difficult to hold an individual Party accountable.

As explained in CRS Report RL32528, International Law and Agreements: Their Effect upon U.S. Law:

An international agreement is generally presumed to be legally binding in the absence of an express provision indicating its nonlegal nature. State Department regulations recognize that this presumption may be overcome when there is "clear evidence, in the negotiating history of the agreement or otherwise, that the parties intended the arrangement to be governed by another legal system." Other factors that may be relevant in determining whether an agreement is nonlegal in nature include the form of the agreement and the specificity of its provisions."

The PA was negotiated as a subsidiary agreement to the UNFCCC, which is a legally binding treaty among its Parties under international law.23 Pursuant to enhancing implementation of the UNFCCC, the negotiators adopted the Durban Mandate for "a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force" applicable to all Parties.24 As negotiations under the Durban Mandate neared their resolution, many Parties stated their intentions that the PA be legally binding in many respects.25 The text contains provisions consistent with the form of an agreement intended to be governed by international law, such as entry into force, the depositary for the agreement, dispute settlement, and withdrawal from the agreement.26 As discussed above, the PA also contains specific obligations intended to be binding on Parties to it. Many of the mandatory obligations appear to be distinguishable by use of the imperative verb shall, although some are qualified in ways (e.g., "as appropriate") that soften the potential obligation. Not all provisions in the PA are mandatory. Some provisions exhort but would not legally require Parties (individually or collectively) or the Secretariat to undertake actions or to conform to norms under the PA. Some provisions are facilitative.

The principal mandatory provisions for individual Parties are procedural. Among the most important of these is PA Article 4.2:

[E]ach Party shall prepare, communicate, and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve. Parties shall pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions.

While the PA obligates Parties to submit NDCs to mitigate GHG emissions—with certain characteristics and frequency of those submissions identified in the PA or to be determined in guidance of the Parties—the contents of the NDCs are not intended to be enforceable under the PA. The Department of State has stated:

Even after the United States deposits its instrument and the Agreement enters into force, the U.S. 26-28 percent contribution will not, by the terms of the Agreement, be legally binding. Neither Article 4, which addresses mitigation efforts, nor any other provision of the Agreement obligates a Party to achieve its contribution.27

Article 4.8 requires that Parties' communications of their NDCs shall provide the information necessary for clarity, transparency, and understanding in accordance with guidance on reporting and NDCs to be developed by the APA for adoption by the CMA in its first session. Each Party must communicate an NDC every five years. Each shall also account for its NDC post-submission in accordance with CMA guidance, including reporting on its progress in achieving its NDC.

Each Party must also, "as appropriate," engage in adaptation planning processes and implementation of adaptation-related actions.

While the PA contains many additional requirements, such as to provide "continuous and enhanced support … to developing country Parties" for required adaptation efforts, those provisions are collective obligations. There is currently no mechanism by which an individual Party could be held accountable for collective shortcomings.

Are PA requirements new for some Parties?

The PA contains a multitude of obligations for governments that are Parties to it, but few experts have suggested that there are substantive, legal obligations for the United States in the PA beyond those in the UNFCCC. The Obama Administration articulated its view: "The elements that are binding are consistent with already approved previous agreements."28

Some of the PA's provisions are, arguably, new obligations for other Parties, such as the (mostly low-income) Parties not listed in the UNFCCC's Annex I. One example is the provision requiring all Parties to ultimately be held to common transparency and review guidelines.

All Parties to the UNFCCC,29 including the United States, have a host of obligations under the treaty. These existing obligations require Parties to:

- inventory, report, and control their human-related GHG emissions, including from land use;

- cooperate in preparing to adapt to climate change;

- seek to mobilize financial resources; and

- assess and review, through the COP, the effective implementation of the UNFCCC, including the commitments therein.

The industrialized countries listed in Annex I of the UNFCCC, including the United States, took on stronger obligations than other countries with regard to reporting, communicating, and international review. In addition, the then-highest income countries, listed in Annex II of the UNFCCC, also agreed to provide financial, technological, and capacity-building assistance to help developing country Parties meet their obligations.

For countries not listed in Annex I, some obligations under the PA will be new or stronger than those under the UNFCCC. The PA and Decision establish a single framework under which all Parties would:

- communicate every five years and undertake NDCs to mitigate GHG emissions, reflecting the "highest possible ambition" (Article 4.3),

- participate in a single transparency framework that includes communicating their GHG inventories and implementation of their obligations—including financial support provided or received—not less than biennially (with exceptions to a few least developed states), and

- be subject to international review of their implementation.

The United States, as a Party listed in Annex I of the UNFCCC, has already taken on the PA's general obligations under the UNFCCC. In contrast, Parties not listed in Annex I were not subject to UNFCCC provisions that required detailed reporting of policies and measures and their effects,30 among other requirements. Additional provisions subjected Annex I Parties to certain reviews not applicable to other Parties.31 The PA expands reporting and reviews for non-Annex I Parties.

All Parties to the PA will eventually be subject to common procedures and guidelines under it. However, while developed country Parties32 must provide NDCs stated as economy-wide, absolute GHG reduction targets, developing country Parties are exhorted to enhance their NDCs (i.e., deepen their GHG reductions) and move toward similar targets over time in light of their national circumstances. Article 4 states that "each Party's successive nationally determined contribution will represent a progression beyond the Party's then current nationally determined contribution." Many view this as a ratchet mechanism that would result in progressively deeper GHG emission reductions. This may be more an expectation than an obligation.33

What are the financial obligations, if any, for the United States in the PA?

Article 9 of the PA reiterates the obligation in the UNFCCC for developed country Parties, including the United States, to mobilize financial support to assist developing country Parties with mitigation and adaptation efforts (Article 9.1). Also, for the first time under the UNFCCC, the PA encourages all Parties to provide financial support voluntarily, regardless of their economic standing (Article 9.2). The agreement states that developed country Parties should take the lead in mobilizing climate finance and that the mobilized resources may come from a wide variety of sources—noting the significant role of public funds. It adds that the mobilization of climate finance "should represent a progression beyond previous efforts" (Article 9.3).

The COP Decision to adopt the PA uses exhortatory language to restate the collective pledge by developed countries in the 2009 Copenhagen Accord of $100 billion annually by 2020 and calls for continuing this collective mobilization through 2025. In addition, the Parties to the COP agreed to set, prior to their 2025 meeting, a new collective quantified goal for mobilizing financial resources of not less than $100 billion annually to assist developing country Parties.34 The Decision strongly urges developed country Parties to scale up their current financial support—in particular to significantly increase their support for adaptation. The Decision recognizes that "enhanced support" will allow for "higher ambition" in the actions of developing country Parties (1/CP.21§114). This is a collective commitment to which it would be difficult to hold an individual Party accountable.

What is the role of the Green Climate Fund in the PA?

The Decision recognizes the Green Climate Fund (GCF)35 as one of the entities entrusted with the operation of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC (1/CP.21§58) and, thus, as one channel through which official UNFCCC financing may flow. In general, the Decision recognizes that adequate and predictable financial resources will flow from, inter alia, "public and private, bilateral and multilateral sources, such as the Green Climate Fund, and alternative sources" (1/CP.21§54).

The GCF is a multilateral trust fund intended to operate at arm's length from the UNFCCC with an independent board, trustee, and secretariat. The GCF was proposed during the 2009 COP in Copenhagen, Denmark; accepted by Parties as an "operating entity of the financial mechanism under Article 11 of the Convention" during the 2011 COP in Durban, South Africa; and made operational in the summer of 2014. The governing instrument for the GCF states that the GCF is to be "accountable to and function under the guidance of the Conference of Parties" (3/CP.17§A4)—that is, similar in legal structure to the Global Environment Facility—as opposed to "accountable to and function under the guidance and authority of the Conference of Parties" (i.e., similar in legal structure to the Adaptation Fund).

Does the PA address "Loss and Damage"?

A key issue for some Parties in the PA negotiations was "loss and damage" due to climate change. Parties that perceived themselves as vulnerable to climate change have long sought commitments from the historically high-emitting countries to provide liability or funds to compensate for loss and damage that vulnerable Parties may suffer. The UNFCCC Secretariat defined loss and damage, at least temporarily, as "the actual and/or potential manifestation of impacts associated with climate change in developing countries that negatively affect human and natural systems."36 Loss and damage may occur even with preparation and adaptation to anticipated climate change. The United States and other historically high-emitting nations opposed new programs or commitments addressing loss and damage.

In response to the interests of many countries, the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage ("Warsaw Mechanism") was agreed under the UNFCCC in 2013 at COP19 in Decision 3/CP.19. The Warsaw Mechanism is procedural in nature.

Despite strenuous negotiations, the UNFCCC Parties did not adopt proposals that could have established legal remedies—such as liability or compensation for loss and damage. Instead, the negotiators agreed in Article 8 to continue the existing process under the authority of the CMA to explore cooperation and facilitation that could include early warning systems, emergency preparedness, comprehensive risk assessment and management, and improved resilience.

Does the PA include or allow market-based mechanisms to reduce GHG emissions?

Article 6 of the PA recognizes that Parties may use market-based mechanisms that generate and allow international transfer of GHG reduction credits that can be used to meet NDCs. The Decision calls for a work program that would govern market mechanisms and the additional mechanisms under the PA.

Article 6 covers four distinct (but not mutually exclusive) opportunities for Parties to the PA to voluntarily cooperate to mitigate GHG emissions in ways that can lead to transfers of emission reduction credits between Parties:

- Cooperative approaches, acknowledging that Parties may choose, on a voluntary basis, to cooperate in the implementation of their NDCs.37 This provision may be read as broad, potentially encompassing the other means included in the article as well as additional approaches that may emerge through the duration of the PA.

- Transfers of mitigation outcomes between Parties are recognized as a means to meet Parties' NDCs. "Internationally transferred mitigation outcomes" will need to be consistent with future CMA guidance on their GHG accounting, intended to ensure "environmental integrity"—that is, that there is no double counting or other misaccounting that could undermine the abatement pledged by Parties. The language is explicit that the transfers occur under the authorities of the participating Parties, not the CMA. This contrasts with the provisions in the Kyoto Protocol that required exchanges of credits to occur under—and with the prior approval of—Kyoto-established institutions (i.e., the Clean Development Mechanism).

- A mechanism to contribute to mitigation and support sustainable development is established under the CMA that could establish credit for cooperative programs that mitigate GHG emissions and development of a Party. Those credits could be used to meet one Party's NDC. A share of the proceeds from activities under this mechanism will help defray administrative expenses and assist developing countries.

- A framework for non-market approaches is defined but not "established." The provisions make clear that the framework should promote sustainable development; synergies across mitigation, adaptation, finance, and technology transfer; and capacity-building, along with additional purposes. But the nature and processes of this framework remain to be developed.

Collectively, these four mechanisms encompass a diversity of interests and preferred approaches among Parties. They may be viewed as broadly inclusive, not suggesting preferences in the PA for one approach over another.

What gases and sectors does the PA cover?

The PA is silent regarding the anthropogenic gases and sectors potentially covered, leaving the scope bounded by the UNFCCC's scientific definition of what constitutes a GHG.38 The UNFCCC includes all human-related GHGs and all sectoral sources of them. It also includes removals of GHGs from the atmosphere by "sinks" and reservoirs, including land uses (i.e., photosynthesis by vegetation and soils). Article 5 explicitly exhorts Parties to "reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and conservation (REDD+), including through results-based payments."

To support the PA negotiations, most UNFCCC Parties submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) during 2015, constituting country-driven intentions of what each would do to address GHG emission mitigation and, in some cases, adaptation.39 Each Party decided and communicated which GHG and sectors it covered in its INDC, and a wide diversity of scopes were identified across nations. A continuing task for the UNFCCC Secretariat will be to try to put those INDCs into a common metric and assess the aggregate effects of the INDCs. It began this task with an analysis released in October 201540 updated on May 2, 2016.41

The COP Decision giving effect to the PA requested the APA to develop guidance for the CMA to consider and adopt at its first session. The process of negotiating guidance will likely consider methods and approaches for estimating and accounting for anthropogenic GHG emissions and sinks in the NDCs. (See paragraphs 28 and 27 of Decision 1/CP.21.) This process will build on extensive but flexible guidance already adopted under the UNFCCC for estimating and reporting GHG inventories, but challenging issues—such as reporting of sinks—may arise as they have in the past.

Procedural Topics

How did the PA enter into force?

In accordance with Article 21 of the PA, the agreement entered into force on November 4, 2016, on the 30th day after at least 55 countries representing at least 55% of officially reported global GHG emissions deposited their instruments. Entry into force of the PA entailed four steps by Parties:

- 1. Signature by individual national governments;42

- 2. Governments' processes of ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession, according to their domestic laws and practices;

- 3. Deposition of those instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession with the United Nations depositary; and

- 4. Passing a threshold of 55 countries, representing at least 55% of GHG emissions, that have deposited their instruments.

The threshold in step 4, above, was passed on October 5, 2016, initiating the 30-day clock. The PA has legal force only for those nations that are Parties to it—those that have deposited their instruments.

The Durban Mandate for the PA envisioned the PA taking effect in 2020. The entry into force four years sooner than anticipated poses some challenges to the Parties. In particular—as discussed later in "Next Steps for the PA"—Parties are pressed to develop and adopt many procedures and methods to guide their compliance with the PA's provisions. Some procedures were envisioned in the PA as being ready for adoption in the first COP serving as the meeting of the Parties to the PA (CMA). That first meeting began in November 2016 rather than in 2020, and development of rules and procedures are ongoing.

Signatures

More than 170 governments (including the United States and EU) signed the agreement on April 22, 2016.43 This set a new record for signatures on a U.N. treaty in a single day. As of June 1, 2017, the PA had received 195 signatures.44 Signatories included all major emitting countries and the EU; only Nicaragua and Syria had not signed. The PA remained open for signature until April 21, 2017.

Signature alone did not trigger entry into force of the agreement, but was a first step in the process for a UNFCCC Party to become Party to the PA. The PA is explicit in Article 20 that signature is further subject to ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession by the signing state or regional economic integration organization (REIO) before the agreement has legal force on that signatory. After signing, a state that seeks to become Party to the PA proceeds with its own domestic processes,45 defined by its laws, to ratify, accept, approve, or (for nations that do not sign before April 21, 2017) accede to the agreement.

Finally, to become a Party, a national government or an REIO (e.g., the EU) must deposit an instrument of ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession with the U.N. depositary. On April 22, 2016, 15 nations deposited their ratifications with the United Nations, and others pledged to do so as quickly as possible.

Deposits of Instruments of Ratification, Acceptance, Approval, or Accession

By October 5, 2016, 72 nations had deposited their ratifications, acceptances, or approvals of the PA, accounting for more than 56% of global GHG emissions, passing the threshold for the PA to enter into force. In synchrony, the United States and China deposited their instruments with U.N. Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon on September 3, 2016. As of June 23, 2017, 149 Parties had joined the PA, including the major emitters Brazil, the EU and seven of its members, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea, and Ukraine. Additional Parties represent a spectrum of emissions and economies, from Albania to Vanuatu. Among the top 20 emitting countries, only Iran and Russia are not yet Parties. In 2016, Russia pledged to join the PA as quickly as possible.

What actions did the United States take to join the PA?

The United States completed a number of steps necessary to become a Party to the PA. First, the United States became a Party to the umbrella treaty, the UNFCCC, when it entered into force in 1994. The United States participated as a UNFCCC Party in the 21st meeting of the COP when it adopted the PA by consensus, on December 12, 2015.

The United States became a signatory of the PA when Secretary of State John Kerry signed the PA on behalf of the United States on April 22, 2016. On August 29, 2016, President Obama, on behalf of the United States, signed an instrument of acceptance of the PA, effectively providing U.S. consent to be bound by the PA. He deposited that instrument of acceptance directly with U.N. Secretary General Ban-Ki Moon on September 3, 2016. The United States became a Party to the PA when it entered into force on November 4, 2016.

Whether the United States legally could—or should—have become a Party to the PA as a treaty with Senate advice and consent, or as an executive agreement,46 has been a matter of interest for some in Congress and the public. The PA is intended by its negotiators to be an international treaty as defined in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.47 Nonetheless, under U.S. law, the term treaty refers to agreements that receive Senate advice and consent in conformance with Article II of the Constitution. President Obama accepted the PA as an executive agreement rather than seeking the advice and consent of the Senate to ratify it; executive agreements may be made pursuant to congressional authorization, pursuant to authority granted to the executive in a prior treaty, or "solely on the basis of the constitutional authority of the President."48 This process has been used for other international treaties. At least one other international environmental agreement, the 2013 Minamata Convention on Mercury, was entered into as an executive agreement.49

The State Department's Handbook on Treaties and Other International Agreements identifies considerations for the executive branch's determination of the type of agreement and the constitutionally authorized procedures to be followed by the United States in joining an agreement.50 The determination depends on a number of considerations, including whether the PA was negotiated pursuant to a ratified treaty (e.g., the UNFCCC), its content and importance, whether it requires additional legislative authorizations for the United States to comply, related congressional resolutions, and other factors. As examples of application of these considerations, if the PA were to contain new legal obligations for the United States, or if the United States were unable to meet its obligations without additional authority from Congress, those factors would favor regarding the PA as requiring congressional action. Senior officials of the executive branch asserted that the PA is an executive agreement that does not require submission to the Senate because of the way it is structured.51 State Department officials stated that they had "a standard State Department exercise that [they were] going through for authorizing an executive agreement, which this is."52

The State Department's Handbook states, following its listing of considerations, that "[i]n determining whether any international agreement should be brought into force as a treaty or as an international agreement other than a treaty, the utmost care is to be exercised to avoid any invasion or compromise of the constitutional powers of the Senate, Congress as a whole, or the President."53 It also states that consultations on the type of agreement to be used "will be held with congressional leaders and committees as may be appropriate."54 The 2016 White House statement upon deposit of the U.S. instrument of acceptance provided little insight into the decision.55

The Senate Legislative Counsel in 1975 stated its position that "the scope of presidential authority to make executive agreements is unclear." Congress has interests in both the substance of the agreement and protecting its constitutional authorities. In 2015, Members of the 114th Congress introduced several resolutions (e.g., S.Res. 329, S.Res. 290, H.Res. 544, S.Con.Res. 25) to express the sense that the PA should be submitted for the advice and consent of the Senate. Additionally, resolutions were introduced in the House (H.Con.Res. 97, H.Con.Res. 105, H.Res. 218) to oppose the PA or set conditions on its signature or ratification by the United States. None received further action. In the 115th Congress, a number of resolutions have also been introduced to oppose or support U.S. participation in the PA (e.g., H.Con.Res. 55, H.Res. 85, H.Res. 390, S.Con.Res. 17). Again, no further action has occurred.

The 1997 Byrd-Hagel Resolution (S.Res. 98, 105th Congress, adopted 98-0) expressed the Sense of the Senate opposing an agreement pursuant to the UNFCCC that would

(A) mandate new commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for the Annex I Parties, unless the protocol or other agreement also mandates new specific scheduled commitments to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions for Developing Country Parties within the same compliance period, or

(B) would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States.

The PA could be seen to satisfy the first clause, as all Parties have the same obligation to submit NDCs to abate GHG emissions, with all Parties pledging to achieve their contributions by 2030. (The U.S. opted for a target date of 2025.) The substance of the NDCs is not binding for any Party. In the second clause, determining whether the agreement could cause "serious harm" to the U.S. economy would require analysis and judgment.56

Stakeholders have weighed in with their views regarding the appropriate legal form and process for the PA in the United States. Some commentators consider that the PA is appropriately an executive agreement because it does not contain new, specific legal obligations for the United States beyond those in the UNFCCC and already authorized under U.S. law.57 The United States and other Parties to the UNFCCC accepted legally binding obligations when they ratified the UNFCCC, including addressing GHG emissions (Articles 4.1 and 4.2), preparation to adapt to climate change (Article 4.1), financial assistance to developing countries (Articles 4.3-4.5), international cooperation and support (Article 4.1), and regular reporting of emissions and actions (Article 12) with international review (Article 4.2, 7). Some commentators note that the obligation to submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is procedural, because the Parties would not have a legal obligation to comply with the content of the NDC. In other words, a Party could be held to account under the compliance provisions of the PA for not submitting an NDC, but it could not be held accountable under the compliance provisions should that Party not, for example, achieve a GHG emissions target it specified in its NDC. (See discussion in "Are PA requirements new for some Parties?")

Other commentators argued that the PA is a treaty that should have been submitted to the Senate.58 Some gave reasons such as historical practice, the potential costs and benefits, or other factors.59 At least one commentator argued that the PA could, in future decades, result in stronger obligations for the United States than the Senate anticipated when it gave its consent to ratifying the UNFCCC.60

Can a Party withdraw from the PA?

The PA—typical of modern international agreements, including the UNFCCC—includes provisions for Parties to withdraw if they choose to do so. Article 28 spells out a procedure by which a Party may give written notice of withdrawal to the U.N. depositary after three years from the date on which the agreement has entered into force for that Party. The soonest date the United States may submit that intent would be November 4, 2019. The withdrawal would take effect after one year, as soon as November 4, 2020 for the United States, or later if so specified in the notification of withdrawal.

On June 1, 2017, President Donald Trump announced his intent to withdraw the United States from the PA.61 As the PA is an executive agreement, U.S. historical practice suggests that the President may withdraw from the PA, without prior approval by Congress, by submitting notification of withdrawal from the PA to the U.N. Depositary.62

Some have suggested that the United States could withdraw more quickly by exercising the right to withdraw from the UNFCCC under its Article 25. Article 28(3) of the PA specifies: "Any Party that withdraws from the Convention shall be considered as also having withdrawn from this Agreement."

Because the UNFCCC received the Senate's advice and consent in 1992,63 an effort by the executive to terminate that treaty unilaterally could invoke the historical and largely unresolved debate over the role of Congress in treaty termination.64 The Constitution sets forth a definite procedure for the President to make treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate,65 but it does not describe how they should be terminated.66 There are proponents on both sides of the debate over the executive's power of unilateral treaty determination. On the one hand, the Restatement of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States (Third) concludes that the President has the power to terminate or suspend a treaty by virtue of the executive's powers related to foreign affairs.67 On the other hand, some contend that the Founders could not have intended the executive to be the "sole organ" of treaty powers, because the Treaty Clause expressly provides a role for the Senate formation of treaties. The Senate must, by this reasoning, also approve the termination of a treaty that it previously ratified.68

Given the diverse past practices and the unsettled state of the law relating to Congress's role in this process, it is unclear whether the executive would be required to receive congressional or senatorial approval should it decide to withdraw from the UNFCCC. It is also unclear whether the courts would resolve a dispute between the legislative and executive branches over termination of the UNFCCC should a disagreement arise.

What are the roles of Congress with respect to the UNFCCC and the PA?

Congress has power to influence U.S. commitments and performance under the UNFCCC and the PA. As with other actions of the executive branch, Congress retains its powers of appropriations and oversight, as well as of giving (or withdrawing) authorizations regarding implementation of the PA.

Appropriations or prohibition of use of funds for certain purposes have been used on numerous occasions in the context of the UNFCCC with regard to supporting the UNFCCC processes, providing technical or financial assistance to lower capacity countries in furtherance of the treaties, and cooperative activities of particular interest, such as enhancing monitoring of compliance with treaty obligations or promotion of key technologies, such as carbon capture and sequestration.

Members of Congress and their staff routinely consult with the executive branch and conduct oversight with respect to the UNFCCC before and after multilateral sessions and while attending as part of congressional delegations. Letters to executive officials may convey views or request specific information, and legislative resolutions may express majority views more strongly. Congressional hearings provide more public settings for receiving testimony and exchanges of views with the Administration. Committee chairs have requested reviews of particular issues by the Government Accountability Office and others. All of these may continue under the UNFCCC and the PA.

Some key issues that may attract oversight, should the United States proceed with the President's intent to withdraw from the agreement include:

- Options for withdrawing from the PA;

- The degree and content of U.S. participation in the PA activities while the United States is a Party and after withdrawal occurs;69

- Objectives and options for renegotiation of the PA, or of a new "transaction,"70 should other Parties be willing to engage;

- The possible implications for the United States of decisions Parties make following U.S. withdrawal (for example, regarding technology cooperation and trade); or

- Evaluation of bilateral cooperation in areas such as development of advanced technologies and information-sharing.

As long as the United States remains a Party, issues include the following:

- Development of methods and guidance to which PA Parties will be expected to conform concerning reporting on and achievement of NDCs;

- Protection of intellectual property and opportunities for market access in technology-related provisions;

- Balancing and evaluating outcomes of appropriations, partnership programs, regulations, and other federal activities to advance technologies, inform the public, and influence GHG emissions and adaptation to climate change;

- Use and outcomes of any appropriated funding, such as for operations of the Secretariat, bilateral cooperation with other Parties, or the GCF; and

- Overall outcomes of Parties' actions in light of the objectives of the UNFCCC and PA and in view of domestic concerns about potential economic and trade implications and climate effectiveness of the agreement.

Countries' Pledges to Contribute to GHG Emission Mitigation

What did the United States pledge as its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to global GHG mitigation?

Intended NDCs (INDCs)—and, now for Parties, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)71—embody the pledges of countries to abate their GHG emissions, and, in some, to adapt to climate change. They are thus critical to considering the overall effect of the PA. To support the negotiations, most UNFCCC Parties submitted statements or INDCs of the contributions they intended to make to the global effort to mitigate GHG emissions and, in some cases, adapt to climate change. The PA requires formal, country-driven pledges from its Parties as NDCs, though Parties are not bound to achieve the targets or take the actions the NDCs contain.

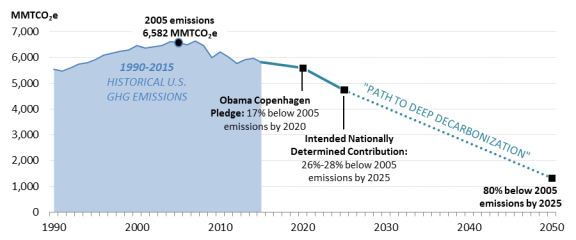

On March 31, 2015, the State Department communicated its INDC, a U.S. pledge to reduce U.S. GHG emissions by 26-28% by 2025 compared to 2005 levels72 (Figure 1). The United States stated that it will "make best efforts to reduce its emissions by 28%." The U.S. INDC was not explicitly conditional on other countries' actions, as some other Parties' were.

The United States noted that its INDC was supported by domestic policy actions that placed the nation on a course to reduce GHG emissions by 17% by 2020 below 2005 levels. The INDC also stated that the U.S. 2025 target is consistent with a straight-line emission reduction path to "deep decarbonization" of 80% or more by 2050.

Having communicated the U.S. INDC to the UNFCCC Secretariat in 2015 before joining the PA, the United States is considered, in accordance with paragraph 22 of the Decision, to have satisfied the PA's requirement to submit a first NCD under PA Article 4.2. The Secretariat has now registered the U.S. pledge in the interim NDC Registry73 in accordance with PA Article 4.12 and Decision paragraph 30.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on U.S. Government, "U.S. Cover Note, INDC and Accompanying Information," March 31, 2015, http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/indc/Submission%20Pages/submissions.aspx; and EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2015, 2017. Notes: These estimates are of net human-related emissions comprising gross emissions from energy and other sectors, net removals of CO2 from the atmosphere by "land use, land use change, and forestry," and sequestration of carbon in harvested wood products. |

Could a Party rescind its NDC and submit a new one?

Once a government becomes a Party to the PA, its INDC may be registered by the Secretariat as the Party's NDC, unless the Party requests otherwise. The question has arisen as to whether, once a Party's NDC has been submitted and registered, that Party may rescind it and submit a new one.

This question is pertinent to the United States for several reasons. President Trump, in announcing his intent to withdraw from the PA, stated that "this includes ending the implementation of the nationally determined contribution."74 In addition, some U.S. stakeholders have expressed concern that the ambition of the U.S. NDC GHG emission reduction target may be too little or too great. Those seeking a less ambitious target may assert that there is not parity in the levels of effort being contributed across countries, especially among competitive nations, or that the costs of achieving the target may harm the U.S. economy or fossil fuel interests. Some have suggested that the United States remain Party to the PA but rescind its NDC and possibly submit a less ambitious substitute. These views and President Trump's statement have raised legal and political questions, including how to interpret related provisions in the PA.

The U.S. NDC has been registered by the Secretariat. Unless the United States rescinds its NDC, the NDC presumably remains in effect. Its content is not binding, and, indeed, achievement of its content could not be definitively determined until at least two years after the 2025 target date.75 Most Parties stated their NDC with a target date of 2030; their GHG emissions data would become available for review by Parties and the public in 2032 or later (depending on the capacity of the country and rules developed under the PA).

Formal accounting of actions Parties are taking to achieve their NDCs would probably not be required until the next biennial national report (BNR) under the UNFCCC is due in 2018, and perhaps not even then. This communication is due under the Convention, not the PA, and so will be expected regardless of U.S. intent to withdraw from the PA. The United States may expect that other Parties will pay particular attention to U.S. explanation of its policies, actions, and GHG trajectories, as required in such reports, when the BNR is published.

The United States may have an interest in supporting rigorous reporting and transparency under the UNFCCC and PA and generally to be viewed as compliant with its international procedural obligations. The United States may therefore have broader considerations than strictly the legal terms of the PA and the UNFCCC.

There are no provisions in the PA permitting a Party to rescind its NDC or express prohibitions. Possible withdrawal of the existing U.S. NDC raises two aspects of compliance with the PA: (1) the requirement that each Party must submit a NDC; and (2) provisions suggesting that each NDC must include a more ambitious pledge, a ratcheting mechanism for ambition in GHG emission reductions.

As noted above, the U.S. NDC has already been registered. Should the United States withdraw its NDC without submitting another, it would arguably no longer be in compliance with PA Article 4.2 as long as the United States' withdrawal has not taken effect (in late 2020 or later). There is no clear time by which a Party must have an initial NDC in place.76 Deadlines may be decided by the PA Parties as they develop rules under the PA. Subsequent NDCs must be submitted every five years. In light of President Trump's stated intent to withdraw, Parties may or may not pursue non-compliance processes should the United States rescind its NDC and not submit a new one.

Article 4.3 states that "each Party's successive nationally determined contribution will represent a progression beyond the Party's then current nationally determined contribution and reflect its highest possible ambition." Article 4.11 of the PA states that "a Party may at any time adjust its existing nationally determined contribution with a view to enhancing its level of ambition, in accordance with guidance adopted by the [CMA]." Various legal advisers and diplomatic officials, in the United States and other countries, have asserted differing opinions regarding whether the "ratcheting" mechanism is legally obligatory. The language appears permissive and not prohibitive. During the negotiations, countries disagreed regarding whether Parties should be obligated to submit NDCs that are progressively more ambitious. As is often the case in difficult negotiations, the differences were resolved by language that may be ambiguous. Whether a less ambitious NDC would be noncompliant would entail further legal interpretation and diplomatic discussion among Parties. The provisions' uses of the words will and may, rather than shall, may undermine the argument that they could be legally mandatory. Nonetheless, a less ambitious NDC would likely be inconsistent with the express intent in multiple provisions aimed at peaking global emissions with reductions thereafter and could be seen as undermining the intent of the agreement overall.

The advantages and disadvantages for the United States of invoking a compliance question may depend on expectations of diplomatic repercussions in light of President Trump's stated intention to withdraw from the PA.77 It may also be influenced by the possibility that the United States might meet the existing NDC target under expected market conditions and public policies, including those at state and local levels, as a few observers suggest.

Can the United States meet its 2025 GHG reduction pledge?

Whether the United States will meet the GHG reduction targets in its NDC is uncertain but does not appear likely. A Party's achievement of its GHG emissions target is not a legal obligation but likely has broader diplomatic and public opinion implications in the PA's "name and shame" compliance system. President Trump announced on June 1, 2017, that the United States would, as of that date, "cease all implementation" of the U.S. NDC. The likelihood that the United States would meet its target would be further reduced should the Administration's review of regulations (such as the Clean Power Plan [CPP]78) by agencies result in rescissions or more permissive standards than those promulgated under the Obama Administration. One dozen states79—along with hundreds of localities, businesses, universities, and other U.S. entities—have stated, nonetheless, their intentions to continue efforts to reduce their GHG emissions80 and, in many cases, to achieve a reduction proportionate to their shares of the U.S. NDC target.

Through 2016, several analyses indicated that the United States could meet its NDC pledge to reduce GHG emissions to 26-28% below their 2005 levels by 2025, relying on optimistic assumptions and additional policies.81 Other analyses, or less optimistic assumptions, suggested that the United States would fall short of its NDC target.82

At the end of 2015, the United States submitted its second biennial report to the UNFCCC83 and itemized actions that the United States was implementing or intended to take that would assist in reducing GHG emissions. The State Department reported that, under then-current measures only, the United States could reduce GHG emissions (net of removals by sinks) by 12-16% below 2005 levels by 2025. This would be well short of the U.S. NDC target. Analyses by non-governmental sources produced similar results.84

New policies and actions of the Trump Administration could decrease the likelihood that the United States could meet the NDC GHG target. President Trump's Executive Order 13783, "Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth," directed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator to review and, if appropriate, suspend, revise, or rescind, "as appropriate and consistent with law," the CPP and other rules that "unduly burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources beyond the degree necessary to protect the public interest or otherwise comply with the law." E.O. 13783 also withdrew President Obama's Climate Action Plan (CAP), among other policies.

One measure in the CAP considered important to achieving the US NDC target was EPA's CPP, promulgated in 2015.85 It set standards limiting CO2 emissions from existing fossil-fuel-fired electric generating facilities, which emitted 33% of U.S. net GHG emissions in 2015.86 Already, the Supreme Court had stayed the rule on February 10, 2016, under litigation challenging the rule. EPA published notice in April 2017 that it was reviewing the CPP and, if appropriate, would initiate proceedings, consistent with the law, to suspend, revise, or rescind the regulation.87 The court paused the CPP litigation for 60 days to allow EPA time for that review.

Regarding GHG emissions from the transportation sector, the Trump Administration announced on March 15, 2017 a reconsideration of vehicle GHG standards for the Model Years 2017-2025 that could ease or delay the emissions limits. The evaluation is due by April 2018.88 Other new policies designed to encourage greater fossil energy production and consumption could increase associated GHG emissions.

The outcomes on U.S. GHG emissions of the ordered regulatory reviews and other changes in policy remain to be seen. Many factors outside of federal policy could increase or decrease the likelihood of meeting the target, and it is not possible to predict future emissions precisely. Some analysts suggest that economic and technological factors may continue to reduce U.S. GHG emissions through 2025, with a few suggesting that the NDC targets could be met through continuing market forces along with state, local, and philanthropic programs. Plentiful natural gas supplies have continued to offer an attractive alternative to coal-fired electricity, and falling costs of electricity from wind and solar—along with federal tax incentives—have expanded investment in these more advanced technologies. Any projection of future emissions is contingent on assumptions about future economic conditions and consumer preference, the size and structure of the energy sector, the influence of existing and new policy measures, and the modeling methods. Strategies being undertaken by states and localities and many in the private sector could also limit GHG emissions. Rapid technological change in the energy sector may have an even greater influence.

Many state and local policies already constrain GHG emissions, and they will continue to influence the U.S. emissions trajectory even under new federal policy. California proceeds with its Advanced Clean Car Program, which included an EPA waiver to use the MY2017-2025 vehicles standards; 12 additional states have adopted the California standards. California has also enacted laws to reduce its GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 and has set a goal to reduce GHG emissions to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. This will require GHG reductions beyond what was counted in earlier projections of California's Climate Action Plan. Ten northeastern states continue to implement the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative limiting CO2 emissions, allowing emissions trading and reinvestment of associated revenues. Many states have renewable energy portfolio requirements, and many have stated that they will continue to pursue GHG reduction policies, as have a number of localities and major corporations. More than 130 U.S. cities have joined the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, pledging to abate GHG emissions locally. A number of electric utilities reliant on fossil fuels are hedging with investments in renewable energy generation or finding them economically competitive with the alternatives. Many experts expect expanding deployment of advanced technologies to continue to reduce costs and increase availability of less GHG-emitting energy systems.

Some potentially countervailing factors include the relatively low prices of motor fuels and impacts on consumer choices and use of vehicles, relatively low operating costs of existing coal-fired plants, electricity grid constraints, and intermittency and storage challenges of renewable energy technologies. If natural gas prices rise significantly, or the CPP is remanded, rescinded, or weakened,89 the NDC targets could be especially challenging to achieve. Under most scenarios, fossil fuels remain strongly present in the U.S. energy economy through 2030 and beyond.

What did other major GHG-emitting countries pledge as their INDCs?

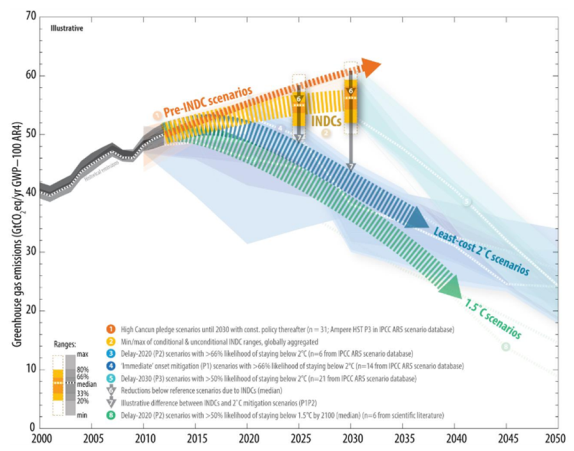

More than 190 Parties to the UNFCCC submitted INDCs—now NDCs for Parties to the PA—that included pledges to address national GHG emissions. Nearly all announced specific GHG targets or actions to contribute to the evolving post-2020 regime. Some included pledges to prepare to adapt to forecasted climate change as well.