Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction: Federal Assistance and Programs

Recent flood disasters have raised congressional and public interest in reducing flood risks and improving flood resilience, which is the ability to adapt to, withstand, and rapidly recover from floods. Federal programs that assist communities in reducing their flood risk and improving their flood resilience include programs funding infrastructure projects (e.g., levees, shore protection) and other flood mitigation activities (e.g., nature-based flood risk reduction) and mitigation incentives for communities that participate in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Assistance Programs

Congress has established various federal programs to assist state, local, and territorial entities and tribes in reducing community flood risk. Each federal program has its own focus, statutory limitations, and way of operating. For example, the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) is triggered by a major disaster declaration pursuant to the Stafford Act, and the Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant program becomes available as the result of a 6% set-aside from the Disaster Relief Fund after every major disaster declaration. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the HMGP and PDM. In contrast to how the HMGP and PDM are triggered, Congress uses annual appropriations and supplemental appropriations to fund other assistance programs. Eligibility for assistance through some of these programs also may be tied to disaster declarations. These assistance programs include

FEMA’s Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grant program;

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) flood risk reduction projects;

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) acquisition of floodplain easements and grants for flood risk reduction projects;

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grants for coastal resilience, restoration, and management (including the Great Lakes);

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) support for state-administered loan programs and direct credit assistance for stormwater management; and

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and Community Development Block GrantDisaster Recovery (CDBGDR) programs.

Flood Insurance

Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program in the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (NFIA; 42 U.S.C. §§4001 et seq.). For federal flood insurance to be available to homeowners and business owners in a community, the NFIP requires participating communities to develop and adopt flood maps and enact minimum floodplain standards based on those flood maps. The NFIP encourages communities to adopt and enforce floodplain management regulations such as zoning codes, building codes, subdivision ordinances, and rebuilding restrictions. The NFIP also encourages communities to reduce flood risk through three programs: the FMA, Community Rating System, and Increased Cost of Compliance coverage.

Context for Federal Activities and Policy Considerations

In the United States, flood-related responsibilities are shared. States and local governments have significant discretion in land use and development decisions that shape communities’ vulnerability to floods and the consequence of floods. Since the 1960s, the federal role in responding to catastrophic and regional flooding has expanded through the NFIP and federal disaster response and recovery efforts. Recent floods and concerns about a changing climate have brought attention to the nation’s and the federal government’s financial exposure to flood losses and floods’ economic, social, and public health impacts. Members of Congress and other decisionmakers are faced with numerous policy questions, including whether federal programs and policies provide incentives or disincentives for states and communities to prepare for floods and manage their flood risks, and whether changes to how federal assistance programs and the NFIP are implemented and funded could improve long-term flood resilience.

Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction: Federal Assistance and Programs

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Primer on Flood Policy and Related Federal Activities

- Evolution of Efforts to Address Flood Risk

- Federal Flood-Related Activities

- Flood Control

- Insurance, Land Use, and Standards

- Mitigation and Nonstructural and Green Infrastructure Approaches

- Flood Monitoring, Modeling, and Mapping

- Federal Assistance Programs

- Federal Emergency Management Agency

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- Supplemental Appropriations

- U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Supplemental Appropriations and Program Amendments

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Supplemental Appropriations

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Supplemental Appropriations

- Flood Insurance and Related Programs

- Flood Maps and State and Local Land-Use Control

- NFIP Flood Mitigation

- Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program

- Community Rating System

- Increased Cost of Compliance Coverage

- Resilience-Related Policy Challenges Facing the NFIP

- Repetitive Flood Losses

- Future Flood Losses

- Policy Considerations

- CRS Products

Figures

- Figure 1. Coastal Barrier Resource Designations Near Charleston, SC

- Figure 2. Examples of Coastal Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction Improvements

- Figure 3. Illustration of Flood Risk Reduction Measures

- Figure 4. Example of a Beach Engineered to Reduce Flood Damages

- Figure 5. Example of Beach Engineered to Reduce Flood Damages

- Figure 6. Example of a EWP Floodplain Easement

- Figure 7. Example of a WFPO Project

- Figure 8. Example of a NOAA-Supported National Coastal Resilience Fund Project

Tables

- Table 1. Selected Federal Programs That Support Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction Improvements

- Table 2. FEMA: Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM)

- Table 3. FEMA: Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP)

- Table 4. FEMA: Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA)

- Table 5. USACE: Flood Damage Reduction Projects

- Table 6. USACE: Flood-Related Continuing Authorities Programs

- Table 7. NRCS: Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations (WPFO)

- Table 8. NRCS: Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP)—Floodplain Easements

- Table 9. NOAA: National Coastal Resilience Fund and Emergency Coastal Resilience Fund

- Table 10. EPA: Clean Water State Revolving Fund

- Table 11. EPA: Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA)

- Table 12. HUD: Community Development Block Grant (CDBG)

- Table 13. HUD: Community Development Block Grant Section 108 Loan Guarantees

- Table 14. HUD: Community Development Block Grant−Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR)

Summary

Recent flood disasters have raised congressional and public interest in reducing flood risks and improving flood resilience, which is the ability to adapt to, withstand, and rapidly recover from floods. Federal programs that assist communities in reducing their flood risk and improving their flood resilience include programs funding infrastructure projects (e.g., levees, shore protection) and other flood mitigation activities (e.g., nature-based flood risk reduction) and mitigation incentives for communities that participate in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Assistance Programs

Congress has established various federal programs to assist state, local, and territorial entities and tribes in reducing community flood risk. Each federal program has its own focus, statutory limitations, and way of operating. For example, the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) is triggered by a major disaster declaration pursuant to the Stafford Act, and the Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant program becomes available as the result of a 6% set-aside from the Disaster Relief Fund after every major disaster declaration. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the HMGP and PDM. In contrast to how the HMGP and PDM are triggered, Congress uses annual appropriations and supplemental appropriations to fund other assistance programs. Eligibility for assistance through some of these programs also may be tied to disaster declarations. These assistance programs include

- FEMA's Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grant program;

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) flood risk reduction projects;

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) acquisition of floodplain easements and grants for flood risk reduction projects;

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) grants for coastal resilience, restoration, and management (including the Great Lakes);

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) support for state-administered loan programs and direct credit assistance for stormwater management; and

- Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and Community Development Block Grant−Disaster Recovery (CDBG−DR) programs.

Flood Insurance

Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program in the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (NFIA; 42 U.S.C. §§4001 et seq.). For federal flood insurance to be available to homeowners and business owners in a community, the NFIP requires participating communities to develop and adopt flood maps and enact minimum floodplain standards based on those flood maps. The NFIP encourages communities to adopt and enforce floodplain management regulations such as zoning codes, building codes, subdivision ordinances, and rebuilding restrictions. The NFIP also encourages communities to reduce flood risk through three programs: the FMA, Community Rating System, and Increased Cost of Compliance coverage.

Context for Federal Activities and Policy Considerations

In the United States, flood-related responsibilities are shared. States and local governments have significant discretion in land use and development decisions that shape communities' vulnerability to floods and the consequence of floods. Since the 1960s, the federal role in responding to catastrophic and regional flooding has expanded through the NFIP and federal disaster response and recovery efforts. Recent floods and concerns about a changing climate have brought attention to the nation's and the federal government's financial exposure to flood losses and floods' economic, social, and public health impacts. Members of Congress and other decisionmakers are faced with numerous policy questions, including whether federal programs and policies provide incentives or disincentives for states and communities to prepare for floods and manage their flood risks, and whether changes to how federal assistance programs and the NFIP are implemented and funded could improve long-term flood resilience.

Introduction

Recent flood disasters have raised congressional and public interest in reducing flood risks and improving flood resilience, which is the ability to adapt to, withstand, and rapidly recover from floods.1 Congress has established various federal programs that may be available to assist state, local, and territorial entities and tribes in reducing flood risks. Among the federal programs are (1) programs that assist with infrastructure to reduce flood risks and other flood mitigation activities,2 and (2) programs of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) that provide incentives to reduce flood risks. This report provides information about these federal programs; it is organized into the following sections:

- a primer on flood policy and federal flood-related activities;

- descriptions of selected federal assistance programs;

- an introduction to flood insurance and related programs; and

- policy considerations.

In the United States, flood-related responsibilities are shared. States and local governments have significant discretion in land use and development decisions (e.g., building codes, subdivision ordinances), which can be factors in determining the vulnerability to and consequence of hurricanes, storms, extreme rainfall, and other flood events. Flood events in recent years and concerns about a changing climate on flood hazards have generated concern about the nation's and the federal government's financial exposure to flood losses, as well as the economic, social, and public health impacts of floods.

Congress and other policymakers may face various policy questions related to flood policy, federal programs, and federalism, including the following:

- Do federal programs provide incentives or disincentives for state and local entities to prepare for floods and manage their flood risks?

- Are federal programs providing cost-effective assistance to state and local entities to reduce flood risks, not only in areas that recently experienced floods, but also in other areas at risk of flooding?

- Could changes to how federal flood-related assistance programs or the NFIP are implemented and funded result in long-term net benefits in terms of avoided federal disaster assistance, lives lost, and economic disruption?

Although this report covers a broad range of federal programs that may be able to assist with reducing community flood risk and improving flood resilience, it is not comprehensive. Multiple aspects of flood policy and specialized federal programs are not addressed herein.3 This report provides an overview of existing federal programs with a brief description of some policy considerations as context for these programs and the nation's flood challenge.

Primer on Flood Policy and Related Federal Activities

Evolution of Efforts to Address Flood Risk

Over the decades, U.S. flood policy has evolved from trying to control floodwaters to managing flood risks. Early efforts focused on flood control and flood damage reduction using engineered structures such as dams and levees. In the late 20th century, the approach shifted to flood risk reduction and mitigation, which expanded the measures employed to include buyouts, easements,4 elevation of structures, evacuation, and other life-saving and damage-reducing actions. More recently, the concept of flood resilience has become more prominent.5 This evolution in part derives from efforts to manage not only floodwaters but also flood risk. Risks associated with floods and other natural disasters often are characterized as a combination of the following elements:

- a hazard, which is the local threat of an event (e.g., probability of a particular community experiencing a storm surge of a specific height);

- vulnerability, which is the pathway that allows a hazard to cause consequences (e.g., level of protection and performance of shore-protection measures); and

- consequences of an event (e.g., loss of life, property damage, economic loss, environmental damage, and social disruption).

For managing flood risks, some stakeholders promote policies to reduce the hazard (e.g., climate change mitigation to reduce sea level rise).6 Other stakeholders are more interested in reducing vulnerability. These stakeholders may support construction of levees, dams, and shore-protection measures; they also may support protection of natural features that provide flood management benefits, like coastal wetlands, natural dunes, and undeveloped floodplains. Some stakeholders support policies to reduce consequences through measures such as development restrictions, building codes, floodproofing of structures, buyouts of vulnerable properties, and improved evacuation routes. Efforts to improve flood resilience combine measures to reduce consequences, vulnerabilities, and, in some cases, hazards.

Federal Flood-Related Activities

Flood Control

Although local, state, and territorial entities and tribes maintain significant flood management responsibilities, since the early 1900s, the federal government has constructed many dams, levees, and other water resource projects to reduce riverine flood damages. The federal role has expanded over the decades, often in response to catastrophic and regional flood events. Examples include construction by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) of levees and floodways as part of the Mississippi River and Tributaries (MR&T) project, which Congress authorized in 1928,7 and drainage structures of the Central and Southern Florida project in and around the Florida Everglades, which Congress authorized in 1948. Starting in the mid-1950s, the federal government also has participated in many coastal flood risk reduction projects consisting of engineered coastal dunes and beaches, floodwalls, storm surge barriers, and levees.8 Nonfederal entities (e.g., municipalities, irrigation districts, county flood control entities) often share in the cost of these flood control projects. Nonfederal entities also may make their own investments in flood control infrastructure and take other actions to reduce flood risk.9

Some stakeholders support using flood control structures to manage flood waters; others oppose these measures because of concerns about their environmental impacts. Other interests raise concerns that flood control structures may encourage development in flood-prone areas (e.g., development behind levees or engineered dunes) and that the residual risks behind levees and shore protections and downriver from dams may be underappreciated.

USACE is the principal federal agency engaged in construction of flood control measures (e.g., levees and engineered coastal dunes).10 The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has acquired floodplain easements and supported construction of small levees and dams in rural areas. Some flood control infrastructure owned by local and state entities has received support from hazard mitigation assistance programs administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) programs of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

Insurance, Land Use, and Standards

Congress shifted the federal role in managing flood risks by entering the flood insurance market. Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program in the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (NFIA; 42 U.S.C. §§4001 et seq.), after private firms had largely abandoned offering flood insurance.11 When Congress established the NFIP, it found that "many factors have made it uneconomic for the private insurance industry alone to make flood insurance available to those in need of such protection on reasonable terms and conditions."12 The NFIP aimed to alter development in flood-prone areas identified as the 100-year floodplain; this floodplain also is referred to as the 1% annual-chance floodplain, or the floodplain for the Base Flood Elevation (BFE) for purposes of the NFIP.13 The NFIP's multipronged regulatory system consists of community flood risk assessment and mapping, purchase requirements for flood insurance for certain residential and commercial structures, and the adoption of minimum local requirements for land use and building codes for vulnerable areas. The NFIP allows for residential and commercial construction in known floodplains, with the proviso that construction must follow building-code regulations that reduce future flood damage and prevent new development from increasing flood risk.

The NFIP requires that participating communities adopt minimum land-use and building-code regulations, but local and state governments maintain the dominant role in adopting building codes (and local governments in their enforcement), including those related to flood risk. A broader federal role in land use and building codes was discussed in Congress in the late 1960s. It largely was not adopted, with a few exceptions for coastal land use (as discussed in the text box titled "Land Use and Federal Statutes Related to Coastal Management").

In 1977, President Carter signed Executive Order (E.O.) 11988 (Floodplain Management), which requires federal actions to avoid supporting development in the 100-year floodplain if alternatives are available. In 2015, President Obama signed E.O. 13690, which, among other things, established a Federal Flood Risk Management Standard (FFRMS) for federally funded projects that required a higher level of flood resilience than E.O. 11988.14 On August 15, 2017, President Trump signed E.O. 13807 in an effort to streamline federal infrastructure approval. Among other actions, E.O. 13807 revoked E.O. 13690. By revoking E.O. 13690, E.O. 13807 appears to have eliminated the FFRMS and returned federal floodplain policy to the original text of E.O. 11988. In addition to complying with the federal agency guidance for E.O. 11988, federal agencies and departments may adopt policies consistent with their authorities that address flood control works and flood risk and resilience for their programs and activities (e.g., establishing elevation requirements for program-funded structures, defining flood mitigation and flood control projects eligible for authorized programs).

|

Land Use and Federal Statutes Related to Coastal Management Prior to the late-1960s, localities largely administered land-use planning and regulation, with some states having roles in specific issues. After the late 1960s, that relationship changed as many states assumed more planning responsibilities, mostly for environmental protection. During this period, Congress considered a national land-use planning program. Although a national program for land-use planning was ultimately rejected, Congress created a program that was limited to the nation's coastal zones—the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended (CZMA; P.L. 92-532, 16 U.S.C. §§1451-1464). Congress later enacted the Coastal Barrier Resources Act of 1982 (CBRA; P.L. 97-348) to address development pressures on undeveloped coastal barriers and adjacent areas. Coastal Zone Management Act The CZMA was enacted to encourage planning to protect natural resources while fostering wise development in the coastal zone. Under the CZMA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) approves coastal zone management programs developed by coastal states and U.S. territories and provides some benefits to participating states and U.S. territories, including funding for coastal zone planning and projects and the ability to review federal activities that may affect their coastal uses or resources. The CZMA recognizes that states (and, in some states, local government) have the lead responsibility for planning and managing their coastal zones. Thirty states and five territories are eligible to participate in the CZMA. One eligible entity (Alaska) is not participating. Participating states and territories have developed widely varying programs that emphasize different elements of coastal management. CZMA grants can be used for numerous CZMA-defined coastal zone objectives, including managing the effects of sea-level rise and reducing threats to life and property. For more information, see CRS Report R45460, Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA): Overview and Issues for Congress, by Eva Lipiec. Coastal Barrier Resources Act Administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the CBRA and subsequent amendments to it have designated undeveloped or relatively undeveloped coastal barriers and other coastal areas as CBRA system units and otherwise protected areas. Most federal spending that would support additional development is prohibited in the CBRA system units. CBRA does not prohibit or regulate any nonfederal activity; it only prohibits funds from the federal government and federal programs from being used to support additional development within any system unit. Additionally, CBRA does not preclude federal expenditures to restore system units to former levels of development after natural disasters (e.g., reconstruction of roads and water or sewer systems to former dimensions and capacity). Unlike the broader spending prohibitions that apply to system units, the only CBRA prohibition that applies to otherwise protected areas is a prohibition on federal flood insurance. An illustration of system units and otherwise protected areas is provided Figure 1. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10859, The Coastal Barrier Resources Act (CBRA), by Eva Lipiec and R. Eliot Crafton.

|

Mitigation and Nonstructural and Green Infrastructure Approaches

After extensive flooding in the Midwest in 1993, Congress allowed federal agencies to assist with a wide array of activities to reduce damage and prevent loss of life, such as moving flood-prone structures and developing evacuation plans. Nonstructural mitigation is now regularly used as part of flood management for new development and during repairs of damaged property and communities.

Natural flood resilience can be reduced by development that degrades wetlands and ecosystems (e.g., mangroves) and increases impervious surfaces, which reduce rainfall infiltration and increase runoff. Some local, state, and federal agencies and programs allow or support approaches that mimic nature or are "nature-based" (e.g., placement of oyster beds along coastlines to reduce erosion),15 especially if there are multiple benefits, such as erosion reduction, improved fish habitat, and water quality benefits from oyster beds. Department of the Interior agencies, NOAA, USACE, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are involved in ecosystem restoration and protection activities, as well as permitting and planning activities, which may restore or protect these natural features and their flood risk reduction benefits.

Runoff from rainfall in urban areas is often referred to as stormwater. For decades local governments and public works officials constructed stormwater infrastructure to move rainwater rapidly away from developed areas. This was done largely through grey infrastructure using pipes, gutters, ditches, and storm sewers. Although these systems were able to collect and move water away, the stormwater discharged from these systems to surface waters often contained pollutants. In recent years, local governments and public works officials have increasingly expressed interest in and adopted green infrastructure for stormwater as a way to manage rainfall to reduce flood losses and to prevent pollution. For stormwater, green infrastructure often consists of using or mimicking natural processes to infiltrate, encourage evapotranspiration, or reuse stormwater on-site where it is generated.16 These techniques can help to reduce or delay runoff that contributes to high water levels in streams and rivers, as well as manage the pollutants entering surface water. Other communities and water users are looking to use green infrastructure to recharge groundwater with urban stormwater and other types of floodwater.

Until recently, the major federal role in stormwater had been EPA regulations to reduce pollution from stormwater pursuant to objectives and requirements in the Clean Water Act.17 That is, the federal government, if it participated financially in stormwater management, focused on the pollution prevention aspects. As a result of legislative and administrative changes by EPA and states administering the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF), activities that "manage, reduce, treat, or recapture stormwater" are now eligible for financial support.18 Such activities may have flood mitigation as well as pollution prevention benefits.

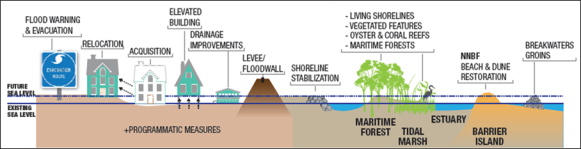

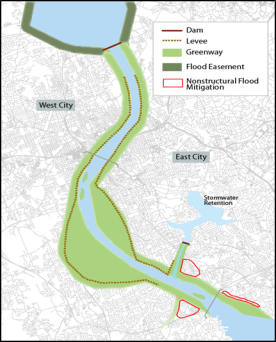

Figure 2 illustrates a suite of flood resilience and risk reduction improvements, including both structural and nonstructural measures, for coastal communities and states. A similar suite of options may be available for communities along rivers. A flood risk management response may incorporate multiple types of improvements. For example, Figure 3 illustrates how levees can be set back from a river to allow for a larger floodplain and how other structural and nonstructural components can be combined to create a more comprehensive flood risk management system (e.g., a hybrid of grey and green infrastructure).

|

Figure 2. Examples of Coastal Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction Improvements |

|

|

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, North Atlantic Coast Comprehensive Study: Resilience Adaptation to Increasing Risk, January 2015, p. 7, http://www.nad.usace.army.mil/Portals/40/docs/NACCS/NACCS_main_report.pdf. Note: Other options to reduce risk also are available, including other forms of zoning and building codes (e.g., floodproofing of lower floors of structures). NNBF = natural and nature-based features. |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Flood Monitoring, Modeling, and Mapping

The federal government is involved in monitoring and modeling flood risk along with nonfederal and private entities. Federal entities engaged in understanding flood hazards and mapping inundation include FEMA, DOI's U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), NOAA, and USACE. For example, federal agencies survey coastlines and conduct research to understand coastal processes, hazards, and resources and report on weather-related hazards, including hurricane storm surge warnings.19 The National Science Foundation also supports research on related topics. Advancements in technologies have assisted in improved understanding of weather, climate, hydrology, and hydraulics. Of the many types of data used to estimate flood risk and produce flood maps, elevation data are fundamental to producing refined estimates and maps. Federal agencies along with state, local, and private entities have been using remote sensing and other technologies to collect elevation data more accurately and precisely for a wide variety of applications, including for maps related to flood risk.20

Federal Assistance Programs

Congress has created various federal programs that may be able to assist state, local, territorial, and tribal entities with flood risk reduction and flood resilience improvements for communities. Table 1 summarizes some of these federal programs.21 Each program shown in Table 1 was created for a specific purpose and has statutory limitations. For example, some programs are triggered only after certain disaster declarations; others are part of regular agency operations. Discussions later in this report provide more information on programs listed in Table 1. Although the subsequent discussions examine geographic eligibility generally, some programs may not be eligible in certain areas designated under the Coastal Barrier Resources Act (P.L. 97-348). Table 1 provides information on regular funding for FY2019 (i.e., annual discretionary appropriations for some programs) and supplemental appropriations provided in FY2019 and FY2020. Additional information is provided in the more detailed program-level discussions. Table 1 reflects the supplemental appropriations enacted during FY2019 and for FY2020 as of mid-November 2019. Each supplemental legislation act often establishes specific conditions, requirements, or uses for funds provided therein. Act-specific criteria and detailed information is not shown in the table but is discussed in the agency- and program-specific discussions of this report.

The first set of assistance programs shown in Table 1 provide assistance targeted specifically at flood-related improvements. The second set addresses not only flood but also other hazard mitigation and resilience activities. The third set includes broader programs that include flood-risk reduction, resilience, or stormwater activities among multiple eligible activities.

In some instances, a state may carry out some activities supported by the programs shown in Table 1 in a coordinated manner. Each state has a State Hazard Mitigation Officer who helps to compile a state mitigation plan, administers certain mitigation funding, and generally has knowledge of the state's existing mitigation resources and its history of programs and funding awards in this area. Also, a few federal programs allow for funds provided through them to be used to satisfy the nonfederal cost-sharing requirement for another federal program (e.g., see entry for CDBG in Table 12).

The descriptions of the programs shown in Table 1 are grouped by the federal agency or department administering them. The order followed is FEMA, USACE, USDA, NOAA, EPA, and HUD.

Table 1. Selected Federal Programs That Support Flood Resilience and Risk Reduction Improvements

(dollars in millions [M] or billions [B])

|

Program |

Agency/Dept. |

Type of Assistance |

FY2019 Fundinga |

FY19/FY20 Supp. Fundsb |

|

Flood-Specific Programs |

||||

|

Flood Mitigation Assistance |

FEMA |

Grant |

$160 M |

— |

|

Flood Damage Reduction Projects |

USACE |

Federal share of project |

$946 M |

$1.775 B |

|

Flood-Related Continuing Authorities Programs |

USACE |

Federal share of project |

$19.5 M |

up to $25 M |

|

Emergency Watershed Protection—Floodplain Easements |

USDA |

Floodplain easement |

$0 |

$435 M |

|

Mitigation and Resilience Programs |

||||

|

Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) |

FEMA |

Grant |

$250 Mc |

— |

|

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program |

FEMA |

Grant |

Unknown, determined per disaster |

Not directly; see program description. |

|

Watershed and Flood Prevention |

USDA |

Grant |

$197 M (discretionary) |

— |

|

National Coastal Resilience Fund and Emergency Coastal Resilience Fund (administered by NFWF) |

NOAA |

Grant |

$30 M |

$50 M |

|

Multipurpose Programs |

||||

|

Clean Water State Revolving Fundd |

EPA |

Loans and other subsidization |

$1.694 B |

— |

|

Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) Program |

EPA |

Credit assistance (e.g., loan or loan guarantee) |

$60 M to cover subsidy costs of ≈$6 B of credit assistance |

— |

|

Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) |

HUD |

Grant |

$3 B |

— |

|

CDBG Section 108 Loan Guarantees |

HUD |

Loan guarantee |

$300 M loan-commitment ceiling |

— |

|

CDBG−Disaster Recovery |

HUD |

Grant |

— |

$2.431 B;P.L. 115-254: $1.680 B |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Notes: FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency; HUD = U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, NFWF = National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; USACE = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture. Subsidy costs are the present value of estimated future government losses from loans and loan guarantees.

a. Many of these programs provide assistance for multiple natural hazards or multiple categories of eligible activities. Therefore, funding levels provided are not exclusively for flood-related projects.

b. Supplemental appropriations were provided in P.L. 116-20 unless shown otherwise.

c. As of FY2019, Pre-Disaster Mitigation is no longer funded by appropriations. In P.L. 116-6, Congress made $250 million available from the Disaster Relief Fund for FY2019.

d. The states implement this program. Historically, the majority of this program's funding has supported wastewater infrastructure activities; it also can support stormwater and green infrastructure.

Federal Emergency Management Agency22

FEMA administers three mitigation grant programs that relate to flood resilience and risk reduction:

- Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant program;

- Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP); and

- Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) program.23

Through FY2019, the PDM program made awards on an annual basis to states through a competitive process. In FY2020, a new procedure for pre-disaster mitigation funds is expected. HMGP assistance is triggered by a major disaster declaration by the President under the authorities of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (the Stafford Act). The FMA awards also are made on an annual basis and are traditionally funded through the insurance premiums of NFIP policyholders. Collectively, FEMA refers to these programs as its Hazard Mitigation Assistance Grant Programs.24 Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4 include information on PDM, HMGP, and FMA, respectively. FMA is also discussed later in this report in "NFIP Flood Mitigation."

None of these programs directly received recent supplemental appropriations in FY2017, FY2018, or FY2019 (as of November 2019). However, HMGP and PDM are funded through the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), which did receive multiple supplemental appropriations.25

The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA 2018) changed funding for pre-disaster mitigation.26 DRRA 2018 authorized a new source of funding for pre-disaster mitigation, to be called the National Public Infrastructure Pre-Disaster Mitigation Fund (NPIPDM). For each major disaster declaration, the President may set aside from the DRF an amount equal to 6% of the estimated aggregate amount of the grants to be made pursuant to the following sections of the Stafford Act:

- 403 (essential assistance),

- 406 (repair, restoration, and replacement of damaged facilities),

- 407 (debris removal),

- 408 (federal assistance to individuals and households),

- 410 (unemployment assistance),

- 416 (crisis counseling assistance and training), and

- 428 (public assistance program alternative program procedures).

The funds from this 6% set-aside are to go to the new NPIPDM. FEMA anticipates that the NFIPDM will receive $300-$500 million per year on average.27 As of September 30, 2019, there was $383 million in the NFIPDM.28 There is potential for significantly increased funding for pre-disaster mitigation following a year with many high-cost disasters, but funds set aside also could be less in a year with few disasters. However, based on the recent funding trends of the DRF, FEMA assumes that a rare circumstance in which there is no set-aside would be rare.29

DRRA 2018's changes to pre-disaster mitigation funding may increase the focus on funding public infrastructure projects that improve community resilience before a disaster occurs. FEMA has the discretion to shape the new pre-disaster mitigation approach and has announced plans to replace the PDM program with a new program called Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC).30 The agency has not released details and it is not yet clear how FEMA will implement BRIC, but FEMA anticipates posting the first BRIC Notice of Funding Opportunity in August 2020, with October 2020 as the target date for the first application period to open.31 FEMA expects BRIC to be funded entirely by the 6% set-aside; however, nothing prohibits Congress from appropriating additional funds for the program.

Funding from the NPIPDM may be used to provide technical and financial mitigation assistance pursuant to each major disaster. An additional clause in DRRA 2018 related to building codes provides that NPIPDM funds may be used "to establish and carry out enforcement activities and implement the latest published editions of relevant consensus-based codes, specifications, and standards that incorporate the latest hazard-resistant designs and establish minimum acceptable criteria for the design, construction, and maintenance of residential structures and facilities that may be eligible for assistance under this Act."32

Other provisions in Section 1234 of DRRA 2018 establish that pre-disaster mitigation funds (authorized under Stafford Act Section 203) would be provided only to states that had received a major disaster declaration in the past seven years,33 or any Indian tribal governments located partially or entirely within the boundaries of such states.34 Other provisions would expand the criteria to be considered in awarding mitigation funds, including the extent to which the applicants have adopted hazard-resistant building codes and design standards and the extent to which the funding would increase resiliency.

The FY2019 PDM program was the last PDM cycle before the rollout of the new BRIC Program. Congress made available $250 million for PDM in FY2019.35 FEMA has made these funds available in a manner similar to that of previous years. In FY2019, each state, territory, and federally recognized tribe is eligible to receive an allocation of up to $575,000. Of the total appropriation, $20 million is to be set aside for federally recognized Native American tribal applicants, with the balance of the FY2019 funds distributed on a competitive basis.36

|

Purpose |

To assist applicants to implement a sustained natural hazard mitigation program prior to disasters. PDM addresses flood and other hazards, including tornadoes, earthquakes, and wildfires. |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Eligible projects may include, but are not limited to, property acquisition, structure demolition, floodproofing of structures, structure relocation, structure elevation, mitigation, and localized and nonlocalized flood risk reduction projects. Historically, program funding concentrated on nonstructural projects such as buyouts of repetitively flooded properties. On June 27, 2014, FEMA issued new policy guidance for eligible projects, including major flood control projects (dikes, dams, levees, etc.) that previously were ineligible for consideration under PDM.a |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

Grants to state agencies, federally recognized tribes, and local governments for mitigation projects as well as mitigation planning. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

Up to 75%/25%, or up to 90%/10% if the applicant is a small, impoverished community. |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

$4 million for mitigation projects. $400,000 for new mitigation plans. |

|

Program Trigger |

6% set-aside for every major disaster declaration for the estimated aggregate amount of the grants made pursuant to Stafford Act §§403, 406, 407, 408, 410, 416, and 428.c |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

Grant application process. State emergency management agency or the office that has primary emergency management responsibility applies directly as an applicant. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Funding is provided to all 50 states, Indian reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

No supplemental appropriations. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

$250 million from the DRF for PDM; PDM is not limited to flood hazards. |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

The Administration requested no funding for FY2020.d |

|

Authorization |

Section 203 of the Stafford Act, 42 U.S.C. §5133. |

|

Website |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Notes: DRF = Disaster Relief Fund; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency.

a. See Federal Emergency Management Agency, Eligibility of Flood Risk Reduction Measures Under the Hazard Mitigation Assistance Programs, FP 204-078-112-1, June 27, 2014, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/96140.

b. This information is based on the FY2019 Notice of Funding Opportunity for PDM. See FEMA, FY2019, Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) Grant Program, Notice of Funding Opportunity, August 26, 2019, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/182169.

c. Before FY2019, the PDM program was funded through annual appropriations.

d. The FY2020 Budget Request notes that, with the amended authority for PDM through the enactment of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act, FEMA no longer requires resources appropriated in Federal Assistance to fund grants for pre-disaster mitigation projects.

|

Purpose |

To reduce risk to individuals and property while reducing reliance on future federal disaster response and recovery funds. |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Eligible projects may include, but are not limited to, property acquisition, structure demolition, floodproofing of structures, structure relocation, structure elevation, mitigation, and localized and nonlocalized flood risk reduction projects. In late 2018 in Section 1210(b) of P.L. 115-254, Congress authorized that HMGP funds could be used toward the federal share of construction for authorized U.S. Army Corps of Engineers water resource projects if such activities are eligible under HMGP. Historically, program funding concentrated on nonstructural projects such as buyouts of repetitively flooded properties, structurally elevating properties, or limited small flood control projects. On June 27, 2014, FEMA issued new policy guidance for eligible projects including major flood control projects (dams, levees, etc.), which previously were ineligible for consideration under HMGP.a |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

Grants to state agencies, federally recognized tribes, local governments, and certain private nonprofit organizations for mitigation projects as well as mitigation planning. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

Up to 75%/25% |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

The total amount of HMGP funding is derived from a formula in law based on the total amount of other grant assistance provided through the Stafford Act (§404(s) of the Stafford Act, 42 U.S.C. §170c). In summary, it is as follows:

States that have an Enhanced State Hazard Mitigation Plan under Section 322(e) of the Stafford Act receive 20% of the total amount.b |

|

Program Trigger |

Triggered by a Stafford Act major disaster declaration by the President. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

Funds are typically made available statewide in the state that received the declaration, not just in the declared counties. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Funding is provided to all 50 states, Indian reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

Not applicable. HMGP is one of many activities funded by appropriations to the DRF. There were no supplemental appropriations to the DRF in FY2019. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

Not applicable. HMGP is one of many activities funded by appropriations to the DRF. The DRF received $12.558 billion in FY2019 funding. |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

Not applicable. HMGP is one of many activities funded by appropriations to the DRF. The Administration has requested $14.549 billion for the DRF. |

|

Authorization |

Section 404 of the Stafford Act, 42 U.S.C. §5170c. |

|

Website |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

a. See Federal Emergency Management Agency, Eligibility of Flood Risk Reduction Measures Under the Hazard Mitigation Assistance Programs, FP 204-078-112-1, June 27, 2014, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/96140.

b. For a list of states with enhanced mitigation plans, see FEMA's website at https://www.fema.gov/hazard-mitigation-plan-status.

|

Purpose |

Program is limited to flood-related mitigation that reduces the risk of properties that repetitively flood and to lessen future insurance claims for the NFIP.a |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Eligible projects may include, but are not limited to, property acquisition, structure demolition, floodproofing of structures, structure relocation, structure elevation, mitigation, and localized and nonlocalized flood risk reduction projects. |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

Grants to state agencies, federally recognized tribes, and local governments for mitigation projects as well as mitigation planning. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

For NFIP insured properties and planning grants: For repetitive loss property with repetitive loss strategy: For severe repetitive loss property with repetitive loss strategy: |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

Various restrictions exist on maximum awards depending on the type of activity funded.b |

|

Program Trigger |

Annual appropriations. FMA receives funding through an offsetting collection of NFIP premiums in annual appropriation acts. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

Grant application process.b |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Funding is provided to all 50 states, Indian Reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

Not applicable. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

$160 million is authorized through offsetting collections. |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

Administration budget request of $175 million in offsetting collections. |

|

Authorization |

Section 1366 of the National Flood Insurance Act, 42 U.S.C. §4104c |

|

Website |

https://www.fema.gov/flood-mitigation-assistance-grant-program |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

a. For more information, see FEMA, Fact Sheet: FY2019 Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) Grant Program, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/182169.

b. For example, by law (42 U.S.C. §4104c(c)(3)), restrictions are placed on the maximum amount that a state or community may receive for updating mitigation plans. For full details, see Federal Emergency Management Agency, FY2019 Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) Grant Program Fact Sheet, August 26, 2019, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/182169.

|

Dams and Flood Risk Primer and Most dams in the United States are owned by private entities, state or local governments, or public utilities. Dams may provide flood risk reduction as a primary purpose or as an associated benefit. Dams and associated structures also may pose a potential safety threat to populations living downstream and populations surrounding associated reservoirs. As dams age, they can deteriorate. The risks of dam deterioration may be amplified by lack of maintenance, misoperation, development in surrounding areas, natural hazards (e.g., weather and seismic activity), and security threats. Some dams, including older dams, may not meet current dam safety standards and may be at risk of failure, including from floods that may exceed the dams' design capacity. Structural failure of dams may threaten public safety, local and regional economies, and the environment, as well as cause the loss of services provided by a dam. As dams age and the population density near many dams increases, attention has turned to mitigating dam failure through dam inspection programs, rehabilitation, and repair, in addition to preventing and preparing for emergencies. According to a 2019 study by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, the total cost to rehabilitate the nonfederal dams in the National Inventory of Dams would be approximately $19 billion. In 2016, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322) authorized the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to administer a High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program to provide funding assistance for the repair, removal, or rehabilitation of certain nonfederal dams. Nonfederal sponsors (such as state governments or nonprofit organizations) may submit applications to FEMA on behalf of eligible dams and then may distribute any grant funding received from FEMA to these dams. Among other requirements, eligible dams must be in a state with a dam safety program, be classified as high hazard (i.e., failure may result in the loss of at least one life), have developed a state-approved emergency action plan, fail to meet the state's minimum dam safety standards, and pose an unacceptable risk. The WIIN Act authorized appropriations for the program through FY2026 and limited individual grants to nonfederal sponsors to the lesser of $7.5 million or 12.5% of total program funds for the year. For FY2019, Congress appropriated $10 million for the program (which was the first funding the program received). FEMA awarded grants to 26 nonfederal sponsors ranging from $153,000 to $1.25 million for technical, planning, design, and construction assistance for rehabilitation of eligible high hazard potential dams. Federal grant assistance must be accompanied by a nonfederal cost share of no less than 35%. For more information on dam safety and related federal programs and assistance, see CRS Report R45981, Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role, by Anna E. Normand. |

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers37

USACE is the primary federal agency involved in construction projects to provide flood damage reduction. It conducts this work through both project-specific and programmatic authorities.38 Typically, most of this work requires that the study and construction costs be shared with a nonfederal sponsor, such as a municipality or levee district. Generally, federal involvement is limited to projects that are determined to have national benefits exceeding their costs, or that address a public safety concern.39 The rate of annual federal discretionary appropriations for USACE projects has not kept pace with the rate of authorization for these projects; therefore, there is competition for annual USACE construction funds. Table 5 and Table 6 include information on USACE flood risk reduction projects and programs. Table 5 provides information on projects that require Congress to specifically authorize their study and construction in legislation. For projects of a limited size and scope, Congress has provided USACE with programmatic authorities to participate in planning and construction of some projects without project-specific congressional authorization; these authorities are known as continuing authorities programs (CAPs). Table 6 provides information on four flood-related CAPs. CAPs are known by the section of the law in which they were authorized. The four flood-related CAPs discussed are the following:

- Section 205 CAP to reduce flood damages,

- Section 103 CAP to reduce beach erosion and hurricane storm damage,

- Section 14 CAP to protect public works and nonprofit services affected by streambank and shoreline erosion, and

- Section 111 CAP to mitigate shore damage from federal navigation projects.

For more information on the CAP authorities, see CRS In Focus IF11106, Army Corps of Engineers: Continuing Authorities Programs, by Anna E. Normand. For more information on the process for project-specific congressional study and construction authorizations, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

Figure 4 illustrates how a USACE project may place sand to reduce flood risk by widening the beach and raising the height of the dune; Figure 5 illustrates a shoreline before and after the USACE project.

|

Figure 4. Example of a Beach Engineered to Reduce Flood Damages (Long Beach Island, NJ) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2013. |

USACE also is authorized to fund the repair of certain nonfederal flood control works (e.g., levees, dams) and federally constructed hurricane or shore protection projects that are damaged by other than ordinary water, wind, or wave action (e.g., storm surge, rather than high tide). To be eligible for this assistance, damaged flood control works must be eligible for and active in the agency's Rehabilitation and Inspection Program (RIP) and have been in an acceptable condition at the time of damage, according to regular inspections by USACE. RIP has 1,100 active nonfederal flood risk management systems participating. Congress funds RIP activities and the agency's flood-fighting efforts through the agency's Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies account. The RIP program does not fund repairs associated with regular operation, maintenance, repair, and rehabilitation. For more information on RIP repair assistance, see the relevant sections of CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

|

Figure 5. Example of Beach Engineered to Reduce Flood Damages (Ocean City, NJ, before and after engineered beach project) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2012 and 2013. |

Supplemental Appropriations

P.L. 116-20, Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act, 2019, was signed by the President on June 6, 2019. Through this legislation, Congress provided $3.258 billion in supplemental appropriations to the following USACE civil works accounts:

- $35 million for Investigations account available to USACE studies in states affected by Hurricanes Florence and Michael and insular areas that were affected by Typhoon Mangkhut, Super Typhoon Yutu, and Tropical Storm Gita;

- $740 million for Construction account available to projects in states affected by Hurricanes Florence and Michael and insular areas that were affected by Typhoon Mangkhut, Super Typhoon Yutu, and Tropical Storm Gita;40 and

- $1.0 billion for Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies (FCCE) account (primarily for flood fighting and RIP-related costs).41

USACE determines which states and insular areas are eligible for funding for the Investigations account and Construction account funds. FEMA disaster declaration data indicate that North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, Florida, Georgia, and Alabama may be eligible for funding based on impacts from Hurricanes Florence and Michael.42 Collectively, Typhoon Mangkhut, Super Typhoon Yutu, and Tropical Storm Gita appear to have affected the insular areas of American Samoa, Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam. Unlike the geographic limitations established by Congress for the Investigation and Construction account funds, the funds in the FCCE do not have geographic limitations.

|

Purpose |

Improvements that reduce riverine and coastal storm damages. These improvements are pursued as individual projects rather than under an authorized national program. |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Flood-damage reduction works, typically engineered works (e.g., levees, engineered dunes and beaches, storm surge gates and dams). Projects generally are required to have national benefits exceeding costs, or address public safety concerns. Projects are generally limited to those that reduce riverine and coastal flood damage; projects generally do not address drainage within a community or flooding from groundwater. |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

USACE study and construction, or credit or reimbursement for federal portion of nonfederal-led study and construction project.a |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

Study: typically 50%/50%. When P.L. 116-20 monies are used, the study costs are 100% federal. Construction: typically 65%/35%. When P.L. 116-20 monies are used, construction costs are 100% federal for ongoing USACE construction projects; for projects other than ongoing construction projects, typical cost sharing applies when using P.L. 116-20 monies. Coastal periodic nourishment: 50%/50%.b Operations and maintenance (O&M): O&M is a nonfederal responsibility for most projects (some legacy projects and dams have O&M provided by USACE). Territories and tribes have the first $484,000 in costs associated with studies and construction activities waived pursuant to 33 U.S.C. §2310. |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

Amount depends on project-specific authorization of appropriations. |

|

Program Trigger |

Annual appropriations; supplemental appropriations. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

For annual appropriations, inclusion in the Administration's work plan for USACE for enacted appropriations is required. For a USACE study, congressional study authorization and nonfederal cost-share of study is required. For a USACE construction project, project-specific congressional construction authorization and nonfederal cost-share of construction is required.c For USACE funds provided in P.L. 116-20, the Administration selects the USACE studies and projects to fund from among those that meet the geographic eligibility identified in P.L. 116-20. For P.L. 116-20 construction funds, either a project-specific congressional authorization or a determination by the Secretary of the Army that the project is technically feasible, economically justified, and environmentally acceptable is required. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Project-specific congressional authorization determines the geographic scope of the project. USACE has participated in projects in all states, some Indian Reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands. P.L. 116-20 limited eligibility to the Investigation and Construction account funds to those states affected by Hurricanes Florence and Michael, and insular areas that were affected by Typhoon Mangkhut, Super Typhoon Yutu, and Tropical Storm Gita. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

P.L. 116-20 provided $740 million (up to $25 million of this amount can be used for USACE's programmatic flood authorities; see Table 6) to the USACE Construction account for the construction of authorized flood and storm damage reduction projects; $35 million to the USACE Investigation account for studies for flood and storm damage reduction in qualifying states and territories. See above description of geographic eligibility for the Investigations and Construction account funds. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

$946 million for flood-related study and construction ($97 million for coastal studies and construction, $849 million for riverine studies and construction).d (Annual appropriations are typically provided in annual Energy & Water Development appropriations acts.) |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

Administration budget request of $211 million for flood-related study and construction ($18 million for coastal studies, $193 million for riverine studies and construction). |

|

Authorization |

Construction of individual projects is authorized by Congress, typically in a Water Resources Development Act or other omnibus water authorization legislation. |

|

Websites |

http://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Project-Planning/WRRDA-7001-Proposals/ http://www.iwr.usace.army.mil/Missions/Flood-Risk-Management/Flood-Risk-Management-Program/ To identify USACE district, use http://www.usace.army.mil/Locations/ |

Source: Congressional Research Service. Amounts shown in table do not include funding for operations and maintenance of USACE projects or funding for the study, construction, operation, maintenance, and repair of projects that are part of the Mississippi River & Tributaries project.

a. For the most part, congressionally authorized USACE flood damage reduction projects have been constructed by the agency (with a nonfederal cost-share). After construction, the projects are turned over to nonfederal sponsors to own, operate, maintain, repair, and rehabilitate. In recent years, some nonfederal sponsors have used authorities to construct projects themselves and seek reimbursement or credit from USACE.

b. For beach and dune nourishment elements of coastal storm damage reduction projects, the construction is often authorized to include regular renourishments (i.e., sand replenishment) over 50 years (with processes to seek extensions).

c. For more information on obtaining congressional USACE study and construction authorization, see CRS Report R45185, Army Corps of Engineers: Water Resource Authorization and Project Delivery Processes, by Nicole T. Carter and Anna E. Normand.

d. Amount does not include $754 million in USACE flood-related O&M spending; much of this is for existing projects that the USACE owns and operates. Amount does not include $274 million associated with flood-related study, construction, and operation and maintenance of projects that are part of the Mississippi River & Tributaries project.

|

Purpose |

Under authorized Continuing Authorities Programs (CAPs), USACE may study and construct certain improvements without additional project-specific congressional authorization. CAPs are known by the section number of the law in which they were authorized. The four flood-related CAPs are for projects that

|

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Flood damage reduction works, often engineered infrastructure, that fall within the authority of the specific CAP, subject to the availability of appropriations. Projects generally are required to have national benefits exceeding costs, or address public safety concerns, as well as be technically feasible and comply with federal environmental and resource statutes. |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

(§205, §103, §14, and §111) USACE study and construction of cost-shared projects. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

Study:

Construction:

Operations & Maintenance:

|

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

Federal assistance for a project (including projects using P.L. 116-20 funds) cannot exceed the following:

|

|

Program Trigger |

Annual appropriations; supplemental appropriations. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

State, tribal, or local government agency may submit to the local USACE district a written request for work under a CAP authority. USACE identifies and selects eligible projects for funding using enacted appropriations for the CAP program. Demand for CAP projects often exceeds federal funds. For P.L. 116-20 funds, the Administration selects which activities to fund from among USACE studies and projects that meet (1) geographic eligibility identified in P.L. 116-20 and (2) specific per-project federal cost limits and other limitations of the CAP programs. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Sections 205, 14, and 11 are open to all of the United States and Indian Reservations and have been interpreted as being open to territorial possessions. Section 103 is open to activities associated with the shores and beaches of the United States, Indian reservations, and U.S. territories and possessions. P.L. 116-20 limited eligibility for its CAP funds to states affected by Hurricanes Florence and Michael, and insular areas that were affected by Typhoon Mangkhut, Super Typhoon Yutu, and Tropical Storm Gita. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

P.L. 116-20 provided up to $25 million for "continuing authorities projects to reduce the risk of flooding and storm damage" in eligible states and insular areas. See above description of geographic eligibility. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

(§205) $8.0 million; (§103) $4.0 million; (§14) $8.0 million; (§111) $8.0 million. (Annual appropriations are typically provided in annual Energy and Water Development appropriations acts). |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

Administration budget request for Section 205 was $1.0 million. No funding was requested by the Administration for Section 103, Section 14, or Section 111. |

|

Authorization |

(§205) 33 U.S.C. §701s. (§103) 33 U.S.C. §426g. (§14) 33 U.S.C. §701r. (§111) 33 U.S.C. §426i. |

|

Website |

No national USACE CAP website; to identify USACE district, use http://www.usace.army.mil/Locations/. |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Notes: For more on the continuing authorities programs, see CRS In Focus IF11106, Army Corps of Engineers: Continuing Authorities Programs, by Anna E. Normand.

U.S. Department of Agriculture43

As at the USACE, USDA's role in flood control and risk reduction was established by Congress decades ago.44 The general difference between the two agencies is the size, scope, location, and authorization of projects. USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) administers two programs that provide flood damage reduction—the Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations (WFPO) program and the floodplain easement program of the Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) program.45 These programs provide assistance to states, tribes, and local organizations; projects generally originate at the local level and do not require congressional approval. Annual appropriations vary greatly from year to year, resulting in a number of authorized but unfunded projects. Table 7 and Table 8 include information on USDA flood risk reduction and mitigation programs. Figure 6 provides an example of a EWP floodplain easement and Figure 7 provides an example of a WFPO project.

|

Figure 6. Example of a EWP Floodplain Easement (flooded field covered by easement near the Red River east of Bowesmont, ND) |

|

|

Source: Natural Resources Conservation Service, May 1, 2013. |

Supplemental Appropriations and Program Amendments

P.L. 116-20 authorized supplemental appropriations for crop and livestock losses from hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, typhoons, volcanic activity, snowstorms, wildfires, and other natural disasters in CY2018 and CY2019. The act also provided additional funding for the EWP program for necessary expenses related to the consequences of Hurricanes Michael and Florence and wildfires occurring in CY2018, tornadoes and floods occurring in CY2019, and other natural disasters. The EWP funding is to remain available until expended and, as with most EWP funding, no disaster declaration is required.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (2018 farm bill; P.L. 115-334) made few amendments to the WFPO program, most substantially being the authorization of permanent mandatory funding of $50 million annually.46 Historically, the program has received only discretionary funding through the annual appropriations process. Additionally, this program historically has been called the small watershed program, because no project may exceed 250,000 acres and no structure may exceed 12,500 acre-feet of floodwater detention capacity or 25,000 acre-feet of total capacity. Although these limitations were not statutorily changed, the FY2019 appropriation temporarily waives the 250,000-acre limitation for all authorized activities in FY2018 where the primary purpose is not flood prevention.

|

Purpose |

WFPO provides technical and financial assistance to states, Indian tribes or tribal organizations,a and local organizations to plan and install watershed projects. WFPO originally required flood prevention and protection as a function of all projects. The program has since been amended to include other water quality and water resources purposes.b |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

Eligible projects include land treatment, and nonstructural and structural facilities for flood prevention and erosion reduction. Structural measures can include dams, levees, canals, and pumping stations. |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

Partial project grants, plus provision of technical advisory services. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

The federal government pays all costs related to construction for flood control purposes only. Costs for nonagricultural water supply must be repaid by local organizations; however, up to 50% of costs for land, easements, and rights-of-way allocated to public fish and wildlife and recreational developments may be paid with program funds. Local sponsors agree to operate and maintain completed projects. |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

No project may exceed 250,000 acres,c and no structure may exceed more than 12,500 acre-feet of floodwater detention capacity, or 25,000 acre-feet of total capacity without congressional approval. Congressional approval is also required when a project includes an estimated federal contribution of more than $25 million for construction, or includes a storage structure with a capacity in excess of 2,500 acre-feet. There are no population or community income-level limits on applications for WFPO; however, at least 20% of the total benefit of the project must directly relate to agriculture (including rural communities). |

|

Program Trigger |

Program appropriations in enacted legislation and permanently authorized mandatory funding. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

Authorization of approved watershed plans can be (1) requested from sponsoring organizations; (2) congressionally directed; or (3) authorized by the Chief of NRCS. After approval, technical and financial assistance can be provided for installation of works of improvement specified in the plans, subject to annual appropriations. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Projects in all 50 states, Indian Reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

No supplemental appropriations. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

$197 million total. $150 million (discretionary), $50 million of which is required to be allocated to projects and activities that can (1) "commence promptly"; (2) address regional priorities for flood prevention, agricultural water management, inefficient irrigation systems, fish and wildlife habitat, or watershed protection; or (3) address watershed protection projects authorized under Flood Control Act of 1944 (P.L. 78-534). (Annual appropriations typically are provided in annual Agricultural and Related Agencies appropriations acts.) $47 million (mandatory), authorization of $50 million is reduced by sequestration. (Mandatory funding is provided annually and permanently authorized.) |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

No funding was requested by the Administration. |

|

Authorization |

The program consists of projects built under two authorities—Watershed Prevention and Flood Protection Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-566) and Flood Control Act of 1944 (P.L. 78-534). 33 U.S.C. §701b-1, and 16 U.S.C. §§1001-1008. |

|

Website |

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/programs/landscape/wfpo/. |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

a. This includes any Indian tribe or tribal organization, as defined in 25 U.S.C. §5304, having authority under federal, state, or Indian tribal law to carry out, maintain, and operate the works of improvement.

b. Other improvements can include agricultural water management, public recreation development, fish and wildlife habitat development, and municipal or industrial water supplies.

c. The FY2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-6) temporarily waives the 250,000-acre limitation for all authorized WPFO activities in FY2019 unless the primary purpose is for flood prevention.

|

Purpose |

Separate from the general EWP program, floodplain easements are meant to safeguard lives and property from future floods, drought, and the products of erosion through the restoration and preservation of the land's natural values. |

|

Eligible Flood-Related Improvements |

NRCS has authority to restore and enhance floodplain function and values. This includes removing all structures, including buildings, within easement boundaries. Land must be within an eligible floodplain. |

|

Type of Federal Assistance |

Floodplain easements are voluntarily purchased and held by NRCS in perpetuity when in agricultural areas. In areas with residential properties, local project sponsors are required to acquire the underlying land, in fee title, after the easement closes. USDA also provides technical assistance and restoration costs. |

|

Federal/Nonfederal Cost-Share |

The federal government can provide up to 100% of restoration costs and up to 75% of building removal costs. Federal easement payments are limited to the lowest amount identified using the three valuation methods described below under "Maximum Project Assistance." |

|

Maximum Project Assistance |

Landowners receive the smallest of the following values as an easement payment: (1) a geographic area rate established by the NRCS; (2) the fair-market value based on an area-wide market analysis or an appraisal completed according to the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practices; or (3) the landowner's offer. |

|

Program Trigger |

Program appropriations in enacted legislation. |

|

Action Needed to Access Program |

Eligible lands include (1) floodplain lands damaged by flooding at least once in the previous calendar year or damaged by flooding at least twice within the previous 10 years; (2) other lands within the floodplain that would contribute to the restoration of flood storage and flow or erosion control, or would improve the practical management of the easement; or (3) lands that would be inundated or adversely affected as a result of a dam breach. |

|

Geographic Eligibility |

Projects in all 50 states, Indian Reservations, DC, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands. |

|

FY2019 and FY2020 |

General EWP program received $435 million in FY2019 (P.L. 116-20, Title I) for necessary expenses related to the consequences of Hurricanes Michael and Florence and wildfires occurring in CY2018, tornadoes and floods occurring in CY2019, and other natural disasters. Unspecified amount for floodplain easements. No funding, to date, in FY2020. |

|

FY2019 Funding |

Not part of annual budget requests or appropriations. |

|

FY2020 Budget Request |

Not part of annual budget requests or appropriations. |

|

Authorization |

33 U.S.C. §701b-1 and 16 U.S.C. §§2203-2205. |

|

Website |

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/programs/landscape/ewpp/. |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration47