Introduction

This report provides an overview of the FY2020 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-93) and serves as an access portal to other CRS products providing additional context, detail, and analysis relevant to particular aspects of that legislation.

The following Overview tracks the legislative history of the FY2020 defense appropriations act and summarizes the budgetary and strategic context within which it was being debated. Subsequent sections of the report summarize the act's treatment of major components of the Trump Administration's budget request, including selected weapons acquisition programs and other provisions.

Overview

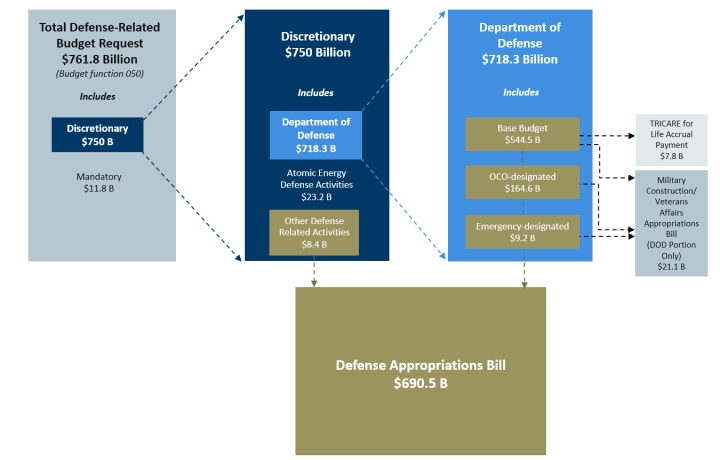

For FY2020, the Trump Administration requested a total of $750.0 billion in discretionary budget authority for national defense-related activities. This included $718.3 billion (95.8% of the total) for the military activities of the Department of Defense (DOD). The balance of the national defense budget request is for defense-related activities of the Energy Department and other agencies.1

Of the amount requested for DOD, $689.5 billion fell within the scope of the annual defense appropriations bill, as did $1.1 billion for certain expenses of the intelligence community. This bill does not include funding for military construction and family housing, which is provided by the appropriations bill that funds those activities, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and certain other agencies. Also not included in the FY2020 defense bill is $7.8 billion in accrual payments to fund the TRICARE for Life program of medical insurance for military retirees, funding for which is appropriated automatically each year, as a matter of permanent law (10 U.S.C. 1111-1117). (See Figure 1.)

|

Figure 1. FY2020 Administration Budget Request |

|

The FY2020 Defense Appropriations Act, enacted as Division A of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for FY2020, provides a total of $687.8 billion for DOD, which is $2.86 billion less than President Trump requested for FY 2020. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. FY2020 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-93, Division A)

amounts in millions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Appropriation Title |

FY2019 enacted |

FY2020 request |

House-passed |

Senate-passed |

FY2020 enacted |

|||||

|

Base Budget |

||||||||||

|

Military Personnel |

138,537.0 |

143,476.5 |

141,621.6 |

142,983.8 |

142,446.1 |

|||||

|

Operation and Maintenance |

193,682.9 |

123,944.6 |

206,673.5 |

200,610.1 |

199,415.4 |

|||||

|

Procurement |

135,362.6 |

118,923.1 |

130,544.8 |

132,837.2 |

133,880.0 |

|||||

|

Research and Development |

94,896.7 |

102,647.5 |

100,455.4 |

104,282.1 |

104,431.2 |

|||||

|

Revolving and Management Funds |

1,641.1 |

1,426.2 |

1,426.2 |

1,580.2 |

1,564.2 |

|||||

|

Defense Health Program and Other DOD |

36,212.1 |

35,147.1 |

35,641.8 |

35,728.7 |

36,316.2 |

|||||

|

Related Agencies |

1,036.4 |

1,072.0 |

1,072.0 |

1,053.4 |

1,070.0 |

|||||

|

General Provisions |

-1,963.0 |

-2,698.2 |

-3,904.3 |

-3,803.2 |

||||||

|

Subtotal: |

599,405.9 |

526,637.1 |

614,737.2 |

615,171.2 |

615,319.9 |

|||||

|

Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) |

67,914.0 |

163,980.5 |

68,079.0 |

70,665.0 |

70,665.0 |

|||||

|

Disaster Relief |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1,710.2 |

1,771.4 |

|||||

|

Grand Total |

667,319.9 |

690,617.6 |

682,816.2 |

687,546.5 |

687,756.3 |

|||||

Sources: H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes:

a. To comply with the cap on discretionary appropriations for the FY2020 DOD base budget, the Trump Administration included in its FY2020 DOD request for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), $98.0 billion for base budget purposes. The Armed Services and Appropriations Committees of both the House and Senate chose, instead, to designate the funds in question as part of the DOD base budget.

b. The enacted bill includes $1.77 billion to remedy storm damage to DOD installations that occurred after the Administration's FY2020 budget request was submitted to Congress.

Base Budget, OCO, and Emergency Spending

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, DOD has organized its budget requests in various ways to designate funding for activities that either are related to the aftermath of those attacks or otherwise are distinct from regularly recurring costs to man, train, and equip U.S. armed forces for the long haul. The latter are funds that have come to be referred to as DOD's "base budget." Since 2009, the non-base budget funds have been designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).2

Since enactment of the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), which set binding annual caps on defense3 and non-defense discretionary spending, the OCO designation has taken on additional significance. Spending designated by the President and Congress as OCO or for emergency requirements (such as the storm damage remediation funds in the enacted FY2020 defense bill) is effectively exempt from the spending caps.

Under the law in effect when the FY2020 budget was submitted to Congress, the defense spending cap for FY2020 was $576.2 billion. The Administration's FY2020 budget request for defense-related programs included that amount for the base budget plus an additional $97.9 billion that also was intended to fund base budget activities but which was designated as OCO funding, in order to avoid exceeding the statutory defense spending cap.4

The Armed Services and Appropriations Committees of both the Senate and the House treated the "OCO for base" funds as part of the base budget request. The issue became moot with the enactment on August 2, 2019 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-37) which raised the defense spending cap for FY2020 to $666.5 billion.5

|

Border Wall Construction As enacted (P.L. 116-93, Div. A), the FY2020 Defense Appropriations Act included no restrictions on the ability of President Trump to use appropriated funds to construct barriers along the U.S.-Mexico border. Section 8127 of the House-passed version of the bill (H.R. 2968) would have prohibited the use of funds appropriated by this act or any other act for that purpose. The provision was a response to the Trump Administration's use of DOD funds appropriated for other purposes, to construct barriers along the U.S. Border with Mexico. The issue was a sticking point in year-end negotiations between Congress and the Administration aimed at reaching an overall agreement on FY2020 appropriations. In the course of negotiations leading to the final package of FY2020 appropriation bills, it was agreed that the bills would include no restrictions on existing presidential authority to transfer funds. For background and analysis on this issue, see CRS Report R46002, Military Funding for Border Barriers: Catalogue of Interagency Decisionmaking, by Christopher T. Mann and Sofia Plagakis; CRS Insight IN11210, Possible Use of FY2020 Defense Funds for Border Barrier Construction: Context and Questions, by Christopher T. Mann; and CRS Insight IN11052, The Defense Department and 10 U.S.C. 284: Legislative Origins and Funding Questions, by Liana W. Rosen. |

Legislative History

Separate versions of the FY2020 defense appropriations bill were reported by the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate. After the House committee reported its version (H.R. 2968), the text of that bill was incorporated into H.R. 2740, which the House passed on June 19, 2019, by a vote of 226-203. The Senate committee reported its version of the bill (S. 2474) on September 12, 2019, but the Senate took no action on that measure. A compromise version of the defense bill was agreed by House and Senate negotiators and then was incorporated by amendment into another bill (H.R. 1158), which was passed by both chambers. (See Table 2.)

In the absence of a formal conference report on the bill, House Appropriations Committee Chairman Nita Lowey inserted in the Congressional Record an Explanatory Statement to accompany the enacted version of H.R. 1158.6

Table 2. FY2020 Defense Appropriations Act

(H.R. 2968; S. 2474; H.R. 1158; P.L. 116-93)

|

Subcommittee Markup |

House Report (H.R. 2968) |

House Passage (H.R. 2740) |

Senate Report |

Senate Passage |

Conf. Report |

Conference Report Approval |

Public Law |

||

|

House |

Senate |

House |

Senate |

||||||

|

5/15/2019 |

9/10/2019 voice vote |

H. Rept. 116-84 |

6/19/2019 |

S. Rept. 116-103 |

No action taken |

12/17/2019 |

12/19/2019 |

P.L. 116-93 |

|

Note: The House and Senate agreed on text of the final bill by exchange of amendments without convening a formal conference committee. An Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, appears in the Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Strategic Context

The President's FY2020 budget request for DOD reflects a shift in strategic emphasis based on the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS), which called for "increased and sustained investment" to counter evolving threats from China and Russia. This marks a change from the focus of U.S. national security policy for nearly the past three decades and a renewed emphasis on competition between nuclear-armed powers, which had been the cornerstone of U.S. strategy for more than four decades after the end of World War II.

During the Cold War, U.S. national security policy and the design of the U.S. military establishment were focused on the strategic competition with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and on containing the spread of communism globally. In the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union, U.S. policies were designed – and U.S. forces were trained and equipped – largely with an eye on dealing with potential regional aggressors such as Iraq, Iran, and North Korea and recalibrating relations with China and Russia.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, U.S. national security policy and DOD planning focused largely on countering terrorism and insurgencies in the Middle East while containing, if not reversing, North Korean and Iranian nuclear weapons programs. However, as a legacy of the Cold War, U.S. and allied military forces had overwhelming military superiority over these adversaries and, accordingly, counter-terrorism and counterinsurgency operations were conducted in relatively permissive environments.

The 2014 Russian invasion of the Crimean peninsula and subsequent proxy war in eastern Ukraine fostered a renewed concern in the United States and in Europe about an aggressive and revanchist regime in Moscow. Meanwhile, China began building and militarizing islands in the South China Sea in order to lay claim to key shipping lanes and to reinforce its claims to sovereignty over the South China Sea, itself. Together, these events highlighted anew the salience in the U.S. national security agenda of competing with other great powers, that is, states able and willing to use military force unilaterally to accomplish their objectives. At the same time, the challenges that had surfaced at the end of the Cold War (e.g., fragile states, genocide, terrorism, and nuclear proliferation) remained serious threats to U.S. interests.

In some cases, adversaries appear to be collaborating to achieve shared or compatible objectives and to take advantage of social and economic tools to advance their agendas. Some states are also collaborating with non-state proxies (including, but not limited to, militias, criminal networks, corporations, and hackers) and deliberately blurring the lines between conventional and irregular conflict and between civilian and military activities. In this complex security environment, conceptualizing, prioritizing, and managing these numerous problems, arguably, is more difficult than it was in eras past.

The Trump Administration's December 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS)7 and the 11-page unclassified summary of the January 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS)8 explicitly reorient U.S. national security strategy (including defense strategy) toward a primary focus on great power competition with China and Russia and on countering their military capabilities.

In addition to explicitly making great power competition the primary U.S. national security concern, the NDS also argues for a focus on bolstering the competitive advantage of U.S. forces, which, the document contends, has eroded in recent decades vis-à-vis the Chinese and Russian threats. The NDS also maintains that, contrary to what was the case for most of the years since the end of the Cold War, U.S. forces now must assume that their ability to approach military objectives will be vigorously contested.

The Trump Administration's strategic orientation, as laid out in the NSS and NDS is consistent with the strategy outlined in comparable documents issued by prior Administrations, in identifying five significant external threats to U.S. interests: China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and terrorist groups with global reach. In a break from previous Administrations, however, the NDS views retaining the U.S. strategic competitive edge relative to China and Russia as a higher priority than countering violent extremist organizations. Accordingly, the new orientation for U.S. strategy is sometimes referred to a "2+3" strategy, meaning a strategy for countering two primary challenges (China and Russia) and three additional challenges (North Korea, Iran, and terrorist groups).

|

2018 National Defense Strategy: Focus on Great Power Competition For additional background and analysis on the National Defense Strategy, see CRS Report R45349, The 2018 National Defense Strategy: Fact Sheet, by Kathleen J. McInnis. For further background and analysis on DOD's heightened focus on great power military competition see CRS Report R43838, Renewed Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke, and CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie. |

Budgetary Context

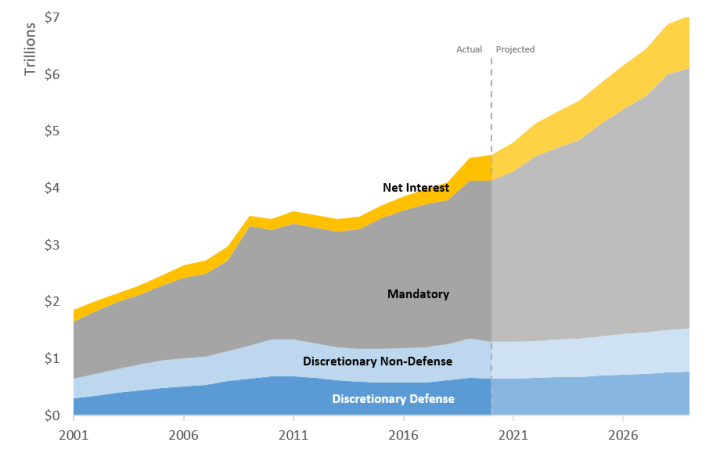

In the more than four decades since the end of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, annual outlays by the federal government have increased by a factor of nine. The fastest growing segment of federal spending during that period has been mandatory spending for entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. (See Figure 2.)

|

Figure 2. Outlays by Budget Enforcement Category, FY2001-FY2029 (in trillions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: OMB, Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2024; CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028 and the data supplement 10-Year Budget Projections from January 2019. Notes: Figures from FY2001 through FY2019 from OMB; projections from FY2020 through FY2029 from CBO. |

Over the past decade, a central consideration in congressional budgeting was the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) as amended, which was intended to control federal spending by enforcement through sequestration of government operating budgets in case discretionary spending budgets failed to meet separate caps on defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority.9

The act established binding annual limits (or caps) to reduce discretionary federal spending through FY2021 by $1.0 trillion. Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previous appropriations, to reduce discretionary spending to the BCA cap for the year in question.

The caps on defense-related spending apply to discretionary funding for DOD and for defense-related activities by other agencies, comprising the national defense budget function which is designated budget function 050. The caps do not apply to funding designated by Congress and the president as emergency spending or spending on OCO.

|

The Budget Control Act For additional information on the BCA and its impact on the defense budget see CRS Report R44039, The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Brendan W. McGarry, CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch, and CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by Grant A. Driessen. |

Congress repeatedly has enacted legislation to raise the annual spending caps. However, at the time the Administration submitted its budget request for FY2020, the national defense spending cap for that year remained $576 billion – a level enacted in 2013 that was $71 billion lower than the revised cap for FY2019.

To avert a nearly 11% reduction in defense spending, the Administration's FY2020 base budget request conformed to the then-binding defense cap. But the Administration's FY2020 request also included $165 billion designated as OCO funding (and thus exempt from the cap) of which $98 billion was intended for base budget purposes. The Armed Services and Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate disregarded this tactic, and considered all funding for base budget purposes as part of the base budget request.

Selected Elements of the Act

Military Personnel Issues

Military End-strength

P.L. 116-93 funds the Administration's proposal for a relatively modest net increase in the number of active-duty military personnel in all four armed forces, but includes a reduction of 7,500 in the end-strength of the Army. According to Army budget documents, the reduction was based on the fact that the service had not met higher end-strength goals in FY2018.10

The act also funds the proposed reduction in the end-strength of the Selected Reserve – those members of the military reserve components and the National Guard who are organized into operational units that routinely drill, usually on a monthly basis. (See Table 3)

|

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

Change from FY2019 to FY2020 request |

House-passed (H.R.2740) |

Senate-committee reported (S.2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

|

Active-duty |

||||||

|

Army |

487,500 |

480,000 |

-7,500 |

478,000 |

480,000 |

480,000 |

|

Navy |

335,400 |

340,500 |

+5,100 |

340,500 |

340,500 |

340,500 |

|

Marine Corps |

186,100 |

186,200 |

+100 |

186,200 |

186,200 |

186,200 |

|

Air Force |

329,100 |

332,800 |

+3,700 |

332,800 |

332,800 |

332,800 |

|

Total: |

1,388,100 |

1,339,500 |

+1,400 |

1,337,500 |

1,339,500 |

1,339,500 |

|

Selected Reserve |

817,700 |

800,800 |

-16,900 |

800,800 |

800,800 |

800,800 |

Source: H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Military Pay Raise

As was authorized by the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92), P.L. 116-93 funds a 3.1% increase in military basic pay that took effect on January 1, 2020.

Sexual Assault Prevention and Treatment

The act appropriates $61.7 million for DOD's Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO), adding to the amount requested $35.0 million for the Special Victims' Counsel (SVC) program11. The SVC organization provides independent legal counsel in the military justice system to alleged victims of sexual assault.

The act also provides $3.0 million (not requested) to fund a pilot program for treatment of military personnel for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder related to sexual trauma. The program was authorized by Section 702 of the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 115-232).

Child Care

P.L. 116-93 added a total of $110 million to the $1.1 billion requested for DOD's childcare program. This is the largest employer-sponsored childcare program in the United States, with roughly 23,000 employees attending to nearly 200,000 children of uniformed service members and DOD civilians.12

The act and its accompanying explanatory statement let stand a requirement in the Senate Appropriations Committee report on S. 2474 for the Secretary of Defense to give Congress a detailed report on DOD's childcare system including plans to increase its capacity and a prioritized list of the top 50 childcare center construction requirements.

|

Military Personnel Issues For information and additional analysis concerning military personnel issues dealt with in the companion FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92), see CRS Report R46107, FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, coordinated by Bryce H. P. Mendez. |

Strategic, Nuclear-armed Systems

P.L. 116-93 generally supports the Administration's FY2020 budget request to continue the across-the-board modernization of nuclear and other long-range strike weapons started by the Obama Administration. The Trump Administration's FY2020 budget documentation described as DOD's "number one priority" this modernization of the so-called nuclear triad: ballistic missile-launching submarines, long-range bombers, and land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

|

Strategic Arms Modernization Program For background and additional analysis, see CRS Report RL33640, U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues, by Amy F. Woolf. |

|

Program |

Approp. |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

Columbia-class Ballistic Missile Submarine (Ohio-class replacement) |

Proc. |

$1,698.9 |

$1,612.0 |

$1,821.9 |

$1,820.9 |

|

R&D |

$419.1 |

$419.1 |

$434.1 |

$427.1 |

|

|

B-21 Bomber |

R&D |

$3,003.9 |

$3,003.9 |

$2,898.1 |

$2,982.5 |

|

Bomber Upgrades (B-52, B-1, B-2) |

Proc. |

$101.3 |

$101.3 |

$58.6 |

$76.4 |

|

R&D |

$718.7 |

$714.3 |

$679.2 |

$667.8 |

|

|

Long-Range Standoff Weapon |

R&D |

$712.5 |

$712.5 |

$712.5 |

$712.5 |

|

Ground-based Strategic Deterrent |

R&D |

$570.4 |

$461.7 |

$657.5 |

$557.5 |

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation; H.Rept. 116-84,House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: In the column headed "Approp. Type". "Proc." means "procurement" and "R&D" means research and development. The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Hypersonic Weapons

P.L. 116-93 generally supported the Administration's effort to develop an array of long-range missiles that could travel at hypersonic speed – that is, upwards of five times the speed of sound (3,800 mph) – and that would be sufficiently accurate to strike distant targets with conventional (non-nuclear) warheads. Although ballistic missiles travel as fast, the types of weapons being developed under the "hypersonic" label differ in that they can maneuver throughout most of their flight trajectory.

DOD has funded development of hypersonic weapons since the early 2000s. However, partly because of reports that China and Russia are developing such weapons, DOD identified hypersonic weapons as an R&D priority in its FY2019 budget request and is seeking – and securing from Congress – funding to accelerate the U.S. hypersonic program. The FY2020 DOD budget request continued this trend, and Congress supported it in the enacted FY2020 defense appropriations bill.

P.L. 116-93 also provided more than three times the amount requested to develop defenses against hypersonic missiles. Such weapons are difficult to detect and track because of the low altitude at which they fly and are difficult to intercept because of their combination of speed and maneuverability.

The act also added $100 million, not requested, to create a Joint Hypersonics Transition Office to coordinate hypersonic R&D programs across DOD. In the Explanatory Statement accompanying the enacted FY2020 defense bill, House and Senate negotiators expressed a concern that the rapid growth in funding for hypersonic weapons development might result in duplication of effort among the services and increased costs.

|

Selected Hypersonic Weapons-related Programs For background and additional information, see CRS Report R45811, Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress, by Kelley M. Sayler. |

|

Agency |

Program Element |

FY2020 Request |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

|

Army |

Hypersonics |

228.0 |

234.0 |

378.6 |

404.0 |

|

|

Navy |

Precision Strike Weapons Development |

593.0 |

410.4 |

563.0 |

512.2 |

|

|

Air Force |

Hypersonics Prototyping |

576.0 |

576.0 |

576.0 |

576.0 |

|

|

DARPA |

Advanced Aerospace Systems |

279.7 |

279.7 |

279.7 |

279.7 |

|

|

Prompt Global Strike Capability Development |

107.0 |

0.0 |

107.0 |

51.0 |

||

|

Hypersonics Capability Development |

0.0 |

85.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

Subtotal: offensive weapons: |

1,766.7 |

1,568.1 |

1,887.3 |

1,805.9 |

||

|

MDA |

Hypersonic Defense |

157.4 |

159.3 |

395.3 |

390.2 |

|

|

MDA |

Ballistic Missile Defense System Space Programs |

0.0 |

0.0 |

108.0 |

108.0 |

|

|

Subtotal: counter-hypersonic defense |

157.4 |

159.3 |

503.3 |

498.2 |

||

|

Joint Hypersonics Transition Office |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

||

Sources: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Note: In the "Agency" column, DARPA is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and MDA is the Missile Defense Agency.

Ballistic Missile Defense Systems

In general, P.L. 116-93 supported the Administration's proposals to strengthen defenses against ballistic missile attacks, whether by ICBMs aimed at U.S. territory, or missiles of shorter range aimed at U.S. forces stationed abroad, or at the territory of allied countries. The missile defense budget request reflected recommendations of the Administration's Missile Defense Review, published in January 2019.13 (See Table 6)

|

Ballistic Missile Defense For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF10541, Defense Primer: Ballistic Missile Defense, by Stephen M. McCall. |

U.S. Homeland Missile Defense Programs

Compared with the Administration's budget request, P.L. 116-93 shifted several hundred million dollars among various components of the system intended to defend U.S. territory against ICBMs. In the explanatory statement accompanying the bill, House and Senate negotiators indicated that the impetus for these changes was DOD's August 2019 cancellation of an effort to develop an improved warhead -- designated the Replacement Kill Vehicle (RKV) -- to be carried by the system's Ground-Based Interceptors (GBIs).

Partly by reallocating funds that had been requested for the RKV programs, the act provides a total of $515.0 million to develop an improved interceptor missile that would replace the GBI and its currently deployed kill vehicle. It also provides:

- $285 million for additional GBI missiles and support equipment; and

- $180 million for R&D intended to improve the reliability GBIs.

|

Program |

Approp. |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S.2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

U.S. Homeland Defenses: Currently deployed system (GMD) and Planned Replacement |

Proc. (GMD) |

9.5 |

9.5 |

343.0 |

285.5 |

|

R&D (GMD) |

1,254.6 |

1,065.5 |

1,801.7 |

1,401.8 |

|

|

R&D (new components) |

843.8 |

843.8 |

824.6 |

860.2 |

|

|

Aegis BMD: Missiles and support equipment for ship-based and Aegis Ashore |

Proc. |

848.4 |

848.4 |

824.6 |

$822.1 |

|

R&D |

935.7 |

888.6 |

931.8 |

945.5 |

|

|

Terminal (short-range) Defenses: (THAAD and Patriot) |

Proc. |

1,555.7 |

1,555.7 |

1,476.8 |

1,495.5 |

|

R&D |

424.3 |

424.3 |

395.5 |

419.3 |

|

|

Israeli Co-operative Defense |

Proc. |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

200.0 |

|

R&D |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

300.0 |

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: In the column headed "Approp. Type". "Proc." means "procurement" and "R&D" means research and development. The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Defense Space Programs

P.L. 116-93 was generally supportive of the Administration's funding requests for acquisition of military space satellites and satellite launches. (See Table 7.)

Space Force O&M Funding

Congress approved $40.0 million of the $72.4 million requested for operation of the newly created Space Force, authorized by P.L. 116-92, the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act. The Explanatory Statement accompanying the bill asserted that DOD had provided insufficient justification for the Space Force budget request. Therefore, DOD received nearly 44% less in Space Force operating funds than it requested. The Explanatory Statement also directed the Secretary of the Air Force to give the congressional defense committees a month-by-month spending plan for FY2020 Space Force O&M funding.

|

Creation of Space Force For additional background, see CRS In Focus IF11244, FY2020 National Security Space Budget Request: An Overview, by Stephen M. McCall and Brendan W. McGarry; and CRS In Focus IF11326, Military Space Reform: FY2020 NDAA Legislative Proposals, by Stephen M. McCall. |

|

Program |

Approp. |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle |

Proc. |

1,237.6 |

1,237.6 |

1,237.6 |

1,237.6 |

|

R&D |

432.0 |

432.0 |

462.0 |

432.0 |

|

|

Space-Based Infra-Red System (SBIRS) – High |

Proc. |

234.0 |

218.0 |

234.0 |

227.0 |

|

R&D |

1,395.3 |

1,193.7 |

1,930.8 |

1,470.3 |

|

|

Global Positioning System (GPS III) |

Proc. |

446.1 |

446.1 |

426.1 |

426.1 |

|

R&D |

1,280.5 |

1,270.4 |

1,256.2 |

1,256.2 |

|

|

Space Force |

O&M |

72.4 |

15.0 |

72.4 |

40.0 |

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: In the column headed "Approp. Type". "Proc." means "procurement", "R&D" means research and development, and O&M means "operation and maintenance". The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Ground Combat Systems

The act supported major elements of the Army's plan to upgrade its currently deployed fleet of ground-combat vehicles. One departure from that plan was the act's provision of 30% more than was requested to increase the firepower of the Stryker wheeled troop-carrier. The program would replace that vehicle's .50 caliber machine gun – effective against personnel – with a 30 mm cannon that could be effective against lightly armored vehicles. (See Table 8.)

Army Modernization Plan

The act sends a mixed message regarding congressional support for the Army's strategy for developing a new suite of combat capabilities. The service plans to pay for the new programs – in part -- with funds it anticipated in future budgets that were slated to pay for continuation of upgrade programs for existing systems. Under the Army's new plan, those older programs would be truncated to free up the anticipated funds. In effect, this means that planned upgrades to legacy systems would not occur so investments in development of new systems could be made sooner. The Army has proposed that programs to upgrade Bradley fighting vehicles and CH-47 Chinook helicopters be among those utilized as these "bill-payers". The enacted bill provides one-third less than was requested for Bradley upgrades, with the $223.0 million that was cut being labelled by the Explanatory Statement as "excess to need." However, the enacted version of the appropriations bill – like the versions of that bill passed by the House and Senate – provides nearly triple the amount requested for the Chinook upgrade, appropriating $46.2 million rather than the $18.2 million requested. The amount appropriated is the amount that had been planned for the Chinook upgrade in FY2020, prior to the publication of the Army's new modernization plan. In the reports accompanying their respective versions of the bill, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees each had challenged the Army's plan to forego upgrades to the existing CH-47 fleet.

|

Army Modernization Program For background and additional information on the Army modernization plan published in 2019, see CRS Report R46216, The Army's Modernization Strategy: Congressional Oversight Considerations, by Andrew Feickert and Brendan W. McGarry. |

Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV)

P.L. 116-93 reined in the Army's third effort in 20 years to develop a replacement for the 1980s-vintage Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, providing $205.6 million of the $378.4 million requested for the Optionally-Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) program. The program had come under fire on grounds that it was too technologically ambitious to be managed under a streamlined acquisition process (Section 804 authority), as the Army proposed.14

The issue became moot after P.L. 116-93 was enacted, when the Army announced on January 16, 2020, that it was cancelling the OMFV contracting plan and restarting it with new design parameters.

|

Program |

Approp. |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

M-1 Abrams tank (mods and upgrades) |

Proc. |

2,114.7 |

2,099.1 |

2,114.7 |

2,099.3 |

|

Mobile Protected Firepower ("light-weight" tank) |

R&D |

310.2 |

294.0 |

301.3 |

285.1 |

|

Bradley Fighting Vehicle (upgrades) |

Proc. |

638.8 |

573.2 |

415.7 |

415.7 |

|

Optionally-Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) |

R&D |

378.4 |

378.4 |

319.9 |

205.6 |

|

Stryker (new vehicles and upgrades) |

Proc. |

698.5 |

819.1 |

665.4 |

911.6 |

|

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) |

Proc. |

485.7 |

480.6 |

444.8 |

444.8 |

|

Paladin Self-propelled Artillery (mods) |

Proc. |

553.4 |

553.4 |

553.4 |

553.4 |

|

M-SHORAD |

Proc. |

262.1 |

214.4 |

238.1 |

233.3 |

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84,House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: In the column headed "Approp. Type". "Proc." means "procurement" and "R&D" means research and development. The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Military Aviation Systems

P.L. 116-93 generally supports the budget request for the major aviation programs of all four armed forces. (See Table 9)

Chinook Helicopter Upgrades

An indicator of potential future disagreements between Congress and the Army was the act's insistence that a planned upgrade of the service's CH-47 Chinook helicopter continue as had been planned prior to submission of the FY2020 budget request. As discussed above, this is one of several programs to improve currently deployed equipment that the Army wants to curtail in order to free up funds in future budgets for the wide-ranging modernization strategy it announced in late 2019.

Prior to tagging the program as a "bill-payer" for new programs, the Army had projected a FY2020 request of $46.4 million associated with procurement of improved "Block II" CH-47s. The amended FY2020 request for the program was $18.2 million, reflecting the Army's decision to truncate the planned procurement. The enacted version of the FY2020 defense bill – like the versions passed by the House and approved by the Senate Appropriations Committee – provided $46.2 million for the program.

F-15 Fighter

The act provides $985.5 million of the $1.05 billion requested for eight F-15s to partly fill the gap in Air Force fighter strength resulting from later-than-planned fielding of the F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. The act shifted funds for two of the eight aircraft and some design efforts (a total of $364.4 million) to the Air Force's Research and Development account on grounds that those F-15s would be used for testing.

The Explanatory Statement accompanying the act directs the Secretary of the Air Force to provide the House and Senate Armed Services and Appropriations Committees with a review of options for reducing the Air Force's shortfall in its planned complement of fighters.

|

Program |

Approp. |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

Fighter Aircraft |

|||||

|

F-35 – All variants and mods |

Proc. |

9,599.6 |

10,383.5 |

11,004.7 |

11,112.8 |

|

R&D |

1,611.8 |

1,611.8 |

1,382.9 |

1,499.4 |

|

|

F/A-18 – new aircraft and mods |

Proc. |

3,011.1 |

2,909.2 |

2,915.9 |

2,891.3 |

|

R&D |

327.2 |

320.3 |

307.2 |

300.3 |

|

|

F-15 – new aircraft and mods |

Proc. |

1,680.1 |

1,614.9 |

1,228.2 |

1,220.6 |

|

R&D |

383.4 |

383.4 |

741.5 |

731.5 |

|

|

F-22 mods |

Proc. |

343.8 |

343.8 |

172.5 |

229.5 |

|

R&D |

496.3 |

496.3 |

546.3 |

546.3 |

|

|

Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) |

R&D |

1,000.0 |

500.0 |

960.0 |

905.0 |

|

Remotely Piloted Vehicles |

|||||

|

RQ-4 Global Hawk |

Proc. |

523.0 |

485.7 |

510.4 |

485.5 |

|

R&D |

438.4 |

438.4 |

421.5 |

421.5 |

|

|

MQ-9 Reaper |

Proc. |

770.2 |

858.4 |

528.5 |

748.0 |

|

R&D |

175.7 |

148.0 |

148.0 |

148.0 |

|

|

MQ-25 Stingray |

R&D |

671.3 |

590.4 |

657.1 |

649.1 |

|

Surveillance and Support Aircraft |

|||||

|

KC-46A tanker |

Proc. |

2,234.5 |

2,198.5 |

2,127.8 |

2,139.7 |

|

R&D |

59.6 |

59.6 |

94.6 |

59.6 |

|

|

P-8 Poseidon patrol plane |

Proc. |

1,314.2 |

1,772.7 |

1,214.0 |

1,742.7 |

|

R&D |

198.7 |

179.7 |

170.7 |

162.7 |

|

|

E-2D Hawkeye radar surveillance plane |

Proc. |

934.7 |

1,260.5 |

917.4 |

1,260.4 |

|

R&D |

232.8 |

191.1 |

235.3 |

226.6 |

|

|

Air Force One replacement |

R&D |

757.9 |

757.9 |

757.9 |

757.9 |

|

Presidential Helicopter replacement |

Proc. |

658.1 |

647.4 |

625.0 |

641.0 |

|

R&D |

187.4 |

165.0 |

187.4 |

176.2 |

|

|

Helicopters and Tilt-rotor Aircraft |

|||||

|

AH-64 Apache |

Proc. |

1,055.9 |

1,047.9 |

1,055.9 |

1,068.3 |

|

UH-60 Blackhawk |

Proc. |

1,660.6 |

1,660.4 |

1,646.6 |

1,667.5 |

|

CH-47 Chinook |

Proc. |

195.3 |

214.0 |

223.3 |

214.0 |

|

R&D |

174.4 |

174.4 |

168.2 |

168.2 |

|

|

CH-53K |

Proc. |

1,022.9 |

1,008.9 |

1,008.9 |

1,062.6 |

|

R&D |

517.0 |

517.0 |

507.0 |

507.0 |

|

|

V-22 Osprey |

Proc. |

1,384.5 |

1,631.6 |

1,631.6 |

1,654.4 |

|

R&D |

203.0 |

193.9 |

216.4 |

209.1 |

|

|

Search and Rescue Helicopter |

Proc. |

884.2 |

876.0 |

856.7 |

850.5 |

|

R&D |

247.0 |

192.0 |

247.0 |

247.0 |

|

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: In the column headed "Approp. Type". "Proc." means "procurement" and "R&D" means research and development. The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Selected long-range bomber programs are listed in Table 4, above.

Shipbuilding Programs

P.L. 116-93 supports major elements of the Navy's shipbuilding budget request. The request in turn reflects a 2016 plan to increase the size of the fleet to 355 ships, a target some 15% higher than the force goal set by the previous Navy plan. The request included – and the act generally supports – funds to begin construction of a number of relatively large, unmanned surface and subsurface ships that carry weapons and sensors and would further enlarge the force.

The act departed from the budget request on two issues that involved more than $1 billion apiece:

- It denied a total of $3.2 billion budgeted for one of the three Virginia-class submarines included in the Administration's request, adding $1.4 billion of those funds instead to the funds requested (and approved by the act) for the other two subs. The increase is intended to pay for incorporating into the two funded ships the so-called Virginia Payload Module -- an 84-foot-long, mid-body section equipped with four large-diameter, vertical launch tubes for storing and launching additional Tomahawk missiles or other payloads.15

- It provided a total of $1.2 billion, not requested, for specialized ships and a landing craft to support amphibious landings by Marine Corps units. (See Table 10.)

|

Shipbuilding Plans For additional background and analysis, see CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. |

Table 10. Selected Naval Systems

amounts in millions of dollars; procurement funds only except as noted

|

Program |

FY2020 |

House- |

Senate-committee reported (S. 2474) |

FY2020 enacted P.L. 116-93 |

|

Ford-class Aircraft Carrier |

2,347.0 |

2,066.0 |

2,236.8 |

2,276.5 |

|

Carrier modernization and refueling |

647.9 |

684.8 |

631.5 |

651.5 |

|

Virginia-class submarine |

9,925.5 |

8,458.9 |

8,325.5 |

8,334.8 |

|

Aegis destroyer |

5,323.3 |

5,239.3 |

5,878.3 |

5,809.3 |

|

Frigate |

1,281.2 |

1,281.2 |

1,281.2 |

1,281.2 |

|

TAO Fleet Oiler (underway refueling ship) |

1,054.2 |

1,054.2 |

1,054.2 |

1,054.2 |

|

ATS Towing and Salvage ship |

150.3 |

150.3 |

88.2 |

150.3 |

|

Amphibious Landing Ships and Craft |

||||

|

LHA helicopter carrier |

0.0 |

0.0 |

650.0 |

|

|

LPD amphibious landing transport |

247.1 |

247.1 |

747.1 |

524.1 |

|

Expeditionary Fast Transport |

0.0 |

0.0 |

261.0 |

261.0 |

|

Ship-to-Shore Connector (air-cushion landing craft) |

0.0 |

65.0 |

0.0 |

65.0 |

Source: CRS analysis of FY2020 DOD budget documentation, H.Rept. 116-84, House Appropriations Committee report to accompany H.R. 2968; S.Rept. 116-103, Senate Appropriations Committee report to accompany S. 2474; and Explanatory Statement to accompany Division A (Defense) of H.R. 1158, the Consolidated Appropriations Bill for FY2020, Congressional Record, December 17, 2019 (Book II), pp. H10613-H10960.

Notes: The Appendix lists the full citation of each CRS product cited in this table by its ID number.

Appendix. CRS Reports, In Focus, and Insights

Following, in numerical order, are the full citations of CRS products cited in this report.

CRS Reports

CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL30563, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, by Jeremiah Gertler.

CRS Report RL30624, Navy F/A-18E/F and EA-18G Aircraft Program, by Jeremiah Gertler.

CRS Report RL31384, V-22 Osprey Tilt-Rotor Aircraft Program, by Jeremiah Gertler.

CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL32665, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL33640, U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues, by Amy F. Woolf.

CRS Report R41129, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch.

CRS Report R43049, U.S. Air Force Bomber Sustainment and Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, by Jeremiah Gertler.

CRS Report R43240, The Army's Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert.

CRS Report R43838, Renewed Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R43543, Navy LPD-17 Flight II and LHA Amphibious Ship Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R44039, The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Brendan W. McGarry.

CRS Report R44229, The Army's M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert.

CRS Report R44463, Air Force B-21 Raider Long-Range Strike Bomber, by Jeremiah Gertler.

CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, by Brendan W. McGarry and Emily M. Morgenstern.

CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch.

CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie.

CRS Report R44968, Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT) Mobility, Reconnaissance, and Firepower Programs, by Andrew Feickert.

CRS Report R44972, Navy Frigate (FFG[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R45288, Military Child Development Program: Background and Issues, by Kristy N. Kamarck.

CRS Report R45349, The 2018 National Defense Strategy: Fact Sheet, by Kathleen J. McInnis.

CRS Report R45519, The Army's Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert.

CRS Report R45811, Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress, by Kelley M. Sayler.

CRS Report R46002, Military Funding for Border Barriers: Catalogue of Interagency Decisionmaking, by Christopher T. Mann and Sofia Plagakis.

CRS Report R46107, FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, coordinated by Bryce H. P. Mendez.

CRS Report R46211, National Security Space Launch, by Stephen M. McCall.

CRS Report R46216, The Army's Modernization Strategy: Congressional Oversight Considerations, by Andrew Feickert and Brendan W. McGarry.

Congressional In Focus

CRS In Focus IF10541, Defense Primer: Ballistic Missile Defense, by Stephen M. McCall.

CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by Grant A. Driessen.

CRS In Focus IF11244, FY2020 National Security Space Budget Request: An Overview, by Stephen M. McCall and Brendan W. McGarry.

CRS In Focus IF11326, Military Space Reform: FY2020 NDAA Legislative Proposals, by Stephen M. McCall.

Congressional Insights

CRS Insight IN11052, The Defense Department and 10 U.S.C. 284: Legislative Origins and Funding Questions, by Liana W. Rosen.

CRS Insight IN11083, FY2020 Defense Budget Request: An Overview, by Brendan W. McGarry and Christopher T. Mann.

CRS Insight IN11148, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch.

CRS Insight IN11210, Possible Use of FY2020 Defense Funds for Border Barrier Construction: Context and Questions, by Christopher T. Mann.