What Is the Farm Bill?

Changes from April 26, 2018 to September 26, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

What Is the Farm Bill?

Contents

- What Is the Farm Bill?

- What Is the Estimated Cost of the Farm Bill?

- How Much Was It Expected to Cost at Enactment in

2014? - What Are the Current Projections?

How Much Has the Farm Bill Cost in the Past2018? How Have Projections Changed Since Enactment?- How Have the Allocations Changed over Time?

- Title-by-Title Summaries of the 2018 Farm Bill

- Title I:

Commodity ProgramsCommodities

- Title II: Conservation

- Title III: Trade

- Title IV: Nutrition

- Title V: Credit

- Title VI: Rural Development

- Title VII: Research , Extension, and Related Matters

- Title VIII: Forestry

- Title

IXX: Energy - Title X: Horticulture

and Organic Agriculture - Title XI: Crop Insurance

- Title XII: Miscellaneous

Figures

Summary

The farm bill is an omnibus, multi-yearmultiyear law that governs an array of agricultural and food programs. Titles in the most recent farm bill encompassed farm commodity price and incomerevenue supports, agricultural conservation, trade and foreign food assistance, farm credit, farm credit, trade, research, rural development, bioenergy, foreign food aidforestry, bioenergy, horticulture, and domestic nutrition assistance. Because it isTypically renewed about every five or six years, the farm bill provides a predictable opportunity for policymakers to comprehensively and periodically address agricultural and food issues.

The most recent farm bill—the Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79; 2014 farm bill)Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, P.L. 115-334—was enacted into law in February 2014December 2018 and expires in 20182023. It succeeded the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79). Provisions in the 20142018 farm bill reshapedmodified the structure of farm commodity support, expanded crop insurance coverage, consolidatedamended conservation programs, reauthorized and revised nutrition assistance, and extended authority to appropriate funds for many U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) discretionary programs through FY2018.

When the 2014 farm bill was enactedFY2023.

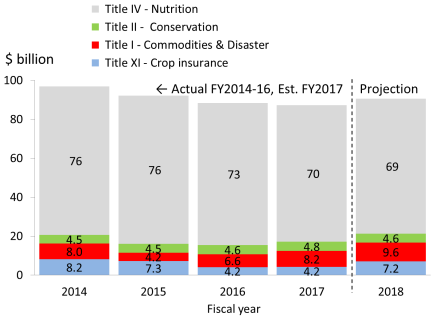

At enactment in December 2018, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the total cost of the mandatory programs in the farm bill would be $489428 billion over the five years FY2014-FY2018. Four titles accounted for 99% ($483.8 billion) of anticipated farm bill mandatory program outlays: nutrition, crop insurance, conservation, and farm commodity support. The nutrition title, which includes the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), comprised 80% of the total. The remaining 20% was mostly geared toward agricultural production across several other titles.

CBO has updated its projections of government spending based on new information about the economy and program participation. Outlays for FY2014 to FY2017 are completed, and updated projections for FY2018 have generally reflected lower-than-expected farm commodity prices in the near term and lower-than-expected participation in SNAP. The new five-year estimated cost of the 2014 farm bill, as of April 2018, is now $455 billion for the four largest titles, compared with $484 billion for those same four titles four years ago. This is $28 billion less than what was projected at enactment.

SNAP outlays are projected to be $26 billion less for the five-year period FY2014-FY2018 than was expected in February 2014. Crop insurance is projected to be $10 billion less for the five-year period and conservation about $5 billion less. In contrast, farm commodity and disaster program payments are projected to be about $13 billion higher than was expected at enactment due to lower commodity market prices (which raises counter-cyclical payments) and higher livestock payments due to disasters.

What Is the Farm Bill?

Four titles account for 99% of anticipated farm bill mandatory outlays: Nutrition, Crop Insurance, Farm Commodity Support, and Conservation. The Nutrition title comprises 76% of mandatory outlays, mostly for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). The remaining 24% of outlays covers mostly risk management and commodity support (16%) and conservation (7%). Programs in all other farm bill titles account for about 1% of mandatory outlays. Many programs are authorized to receive discretionary (appropriated) funds. The distribution of spending across titles in the farm bill over time is not a zero-sum game. Legislative changes enacted in each farm bill account for only a fraction of the observed change between farm bills. Every year, CBO re-estimates the baseline to determine expected costs. Baseline projections can rise and fall over time based on changes in economic conditions, even without any action by Congress. For example, SNAP outlays, which comprise most of the Nutrition title, increased markedly through the recession that ended in 2009. Crop insurance outlays have increased steadily from policy changes, while the farm commodity programs have risen and fallen counter-cyclically with market prices. Conservation program outlays increased steadily since the 1990s but have leveled off in recent years.The farm bill is an omnibus, multi-year law that governs an array of agricultural and food programs. Although agricultural policies sometimes areits five-year duration, FY2019-FY2023, about $1.8 billion more than if the 2014 farm bill were extended. On a 10-year basis, the expected cost was $867 billion over FY2019-FY2028, which was budget neutral compared to extending the 2014 farm bill.

What Is the Farm Bill?

The farm bill is an omnibus, multiyear law that governs an array of agricultural and food programs. Although agricultural policies are sometimes created and changed by freestanding legislation or as part of other major laws, the farm bill provides a predictable opportunity for policymakers to comprehensively and periodically address agricultural and food issues. The farm bill is typically renewed about every five years.

Since the 1930s, farm bills traditionally have or six years.1

Historically, farm bills focused on farm commodity program support for a handful of staple commodities such as —corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, peanuts, dairy, and sugar. Yet farm bills have grown in breadth in recent decades. Among the most prominent additions have been nutrition assistance,Farm bills have become increasingly expansive in nature since 1973, when a nutrition title was first included. Other prominent additions since then include conservation, horticulture, and bioenergy programs.1.2

The omnibus nature of the farm bill can create broad coalitions of support among sometimes conflicting interests for policies that, individually, might not survivehave greater difficulty negotiating the legislative process. This can lead to competition for funds provided in a farm bill. In recent years, more partiesstakeholders have become involved in the debate on farm bills, including national farm groups,; commodity associations,; state organizations,; nutrition and public health officials,; and advocacy groups representing conservation, recreation, rural development, faith-based interests, local food systems, and certified organic production.

The Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79, H.Rept. 113-333Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334, H.Rept. 115-1072), referred to here as the "20142018 farm bill," is the most recent omnibus farm bill. It was enacted in February 2014 and expires mostly in 2018. It succeeded the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-246, "2008 farm bill"). The 2014December 2018, with most provisions expiring in 2023. It succeeded the Agricultural Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-79; 2014 farm bill). The 2018 farm bill contains 12 titles encompassing commodity price and incomerevenue supports, farm credit, trade, agricultural conservation, research, rural development, energy, and foreign and domestic food programs, among other programs.2 (See titles 3 (All titles in the 2018 farm bill are described in the text box below. as well as in the section "Title-by-Title Summaries of the 2018 Farm Bill.") Provisions in the 20142018 farm bill reshapedmodified the structure of farm commodity support, expanded crop insurance coverage, consolidatedamended conservation programs, reauthorized and revised nutrition assistance, and extended authority to appropriate funds for many U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) discretionary programs through FY2018FY2023.

PotentialWithout reauthorization, some farm bill programs would expire, such as the nutrition assistance programs and the farm commodity revenue programs. Procedurally, the potential for expiration and the consequences of expired law may also motivate legislative action.3 When a farm bill expires, not all programs are affected equally. Some programs 4 Functionally, without reauthorization, support for certain basic farm commodities would revert to long-abandoned—and potentially costly—supply-control and price regimes under permanent law dating back to the 1940s. Some programs would cease to operate unless reauthorized, while others might continue to pay old obligations. The farm commodity programs not only expire but would revert to permanent law dating back to the 1940s. Nutrition assistance programs require periodic reauthorization, but appropriations can keep them operatingonly existing obligations. Nutrition assistance programs that require reauthorization and are funded with mandatory spending can continue to operate via appropriations acts. Many discretionary programs would lose their statutory authority to receive appropriations, though an annual appropriations act could provide funding andunder an implicit authorization. Other programs have permanent authority and do not need to be reauthorizedamended in the farm bill have permanent authority (e.g., crop insurance).4

|

|

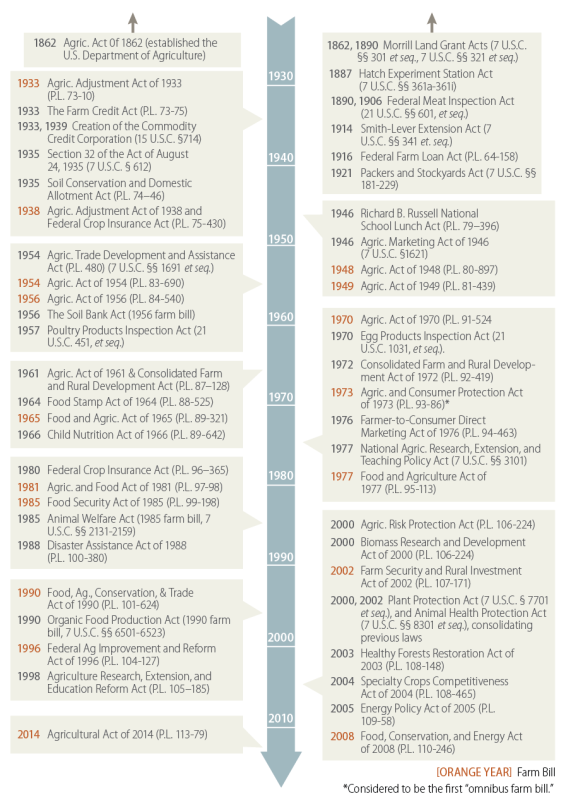

Figure 1 provides a timeline of selected important dates for U.S. farm bill policy and other related laws. In many respects, agricultural policy in the United States began with the creation of USDA, homesteading, and subsequent creation of the land -grant universities in the 1800s. Many stand-alone agricultural laws were passed during the early 1900s to help farmers with credit availability and marketing practices, and to protect consumers via meat inspection.

Source: CRS.

The economic depression and dust bowl in the 1930s prompted the first "farm bill" in 1933, with subsidies and production controls to raise farm incomes and encourage conservation. Commodity subsidies evolved through the 1960s, when Great Society reforms drew attention to food assistance. The 1973 farm bill was the first "omnibus" farm bill

; it. It included not only farm supports but also food stamp reauthorization to provide nutrition assistance for needy individuals. Subsequent farm bills expanded in scope, adding titles for formerly stand-alone laws such as trade, credit, and crop insurance. New conservation laws were added in the 1985 farm bill, organic agriculture in the 1990 farm bill, research programs in the 1996 farm bill, bioenergy in the 2002 farm bill, and horticulture and local food systems in the 2008 farm bill.

|

|

|

Source: CRS. |

What Is the Estimated Cost of the Farm Bill?

The farm bill authorizes programs in two spending categories: mandatory and discretionary.

- Mandatory spending programs generally operate as entitlements. A bill pays for them using multi-year budget estimates (baseline) when the law is enacted.

- Discretionary spending programs are authorized for their scope but are not funded in the farm bill. They are subject to annual appropriations.

While both types of programs are important, mandatory programs often dominate the farm bill debate and are the focus of the farm bill's budget.5

How Much Was It Expected to Cost at Enactment in 2014?

When the current farm bill was enacted in February 2014, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the total cost of mandatory programs would be $489 billion for the 12-title farm bill over the five years FY2014-FY2018.6

Four titles accounted for 99% of anticipated farm bill mandatory outlays: nutrition, crop insurance, conservation, and farm commodity support. The nutrition title, which includes the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), comprised 80% of the total. The remaining 20% was mostly geared toward agricultural production across several other titles (Table 1).

Farm commodity support and crop insurance combined to be 13% of mandatory program costs, with another 6% of costs in USDA conservation programs. All other farm bill titles accounted for about 1% of all mandatory expenditures. Although their relative share is small, titles such as horticulture and research saw their shares increase compared to the 2008 farm bill.

What Are the Current Projections?

In the years since enactment of the farm bill, CBO has updated its projections of government spending several times a year based on new information about the economy and program participation.7 Outlays for FY2014-FY2016 have become final (actual), estimates are available for FY2017, and updated projections for FY2018 have generally reflected lower farm commodity prices and lower costs for SNAP.

The new five-year estimated cost of the 2014 farm bill, as of April 2018, is $455 billion for the four largest titles, compared with $484 billion for those same four titles four years ago (right side of Table 1). This is $28 billion less than what was projected at enactment (-6%). Figure 2 shows these projections and actual outlays for the four major titles of the 2014 farm bill. The result of these new projections is that SNAP outlays are projected to be $26 billion less for the five-year period FY2014-FY2018 than was expected in February 2014 (-7%). Crop insurance is projected to be $10 billion less for the five-year period (-25%) and conservation programs about $5 billion less (-19%). In contrast, farm commodity and disaster program payments are projected to be about $13 billion higher than was expected at enactment (+55%) due to lower commodity market prices (which raises counter-cyclical payments) and higher livestock payments due to disasters.

|

At enactment, February 2014 |

Most recently, April 2018 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm Bill Titles (sorted) |

Projection for FY2014-18 |

Share |

Actual FY2014-16; Estimate FY2017; Projected FY2018 |

Change since enactment |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IV |

Nutrition |

390,650 |

79.9% |

364,861 |

-25,789 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

XI |

Crop Insurance |

41,420 |

8.5% |

31,044 |

-10,376 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

II |

Conservation |

28,165 |

5.8% |

22,939 |

-5,226 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I |

Commodities and Disaster |

23,555 |

4.8% |

36,582 |

+13,027 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subtotal, 4 largest titles |

483,789 |

99.0% |

455,426 |

-28,363 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

III |

Trade |

1,782 |

0.4% |

1,699 |

-82 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

XII |

Miscellaneous, including NAP |

1,544 |

0.3% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

X |

Horticulture |

874 |

0.2% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

VII |

Research |

800 |

0.2% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IX |

Energy |

625 |

0.1% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

VI |

Rural Development |

218 |

0.0% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

VIII |

Forestry |

8 |

0.0% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

V |

Credit |

-1,011 |

-0.2% |

na |

na |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total, Direct Spending |

488,629 |

100.0% |

na |

na The farm bill authorizes programs in two spending categories: mandatory and discretionary.

(millions of dollars, five- and 10-year totals, mandatory spending)

|

Five years (FY2019-FY2023)

|

10 years (FY2019-FY2028)

|

Farm bill titles

|

CBO baseline April 2018

|

Score of 2018 farm bill

|

Projected outlays at enactment

|

CBO baseline April 2018

|

Score of 2018 farm bill

|

Projected outlays at enactment

|

Commodities

|

31,340

|

+101

|

31,440

|

61,151

|

+263

|

61,414

|

Conservation

|

28,715

|

+555

|

29,270

|

59,754

|

-6

|

59,748

|

Trade

|

1,809

|

+235

|

2,044

|

3,624

|

+470

|

4,094

|

Nutrition

|

325,922

|

+98

|

326,020

|

663,828

|

+0

|

663,828

|

Credit

|

-2,205

|

+0

|

-2,205

|

-4,558

|

+0

|

-4,558

|

Rural Development

|

98

|

-530

|

-432

|

168

|

-2,530

|

-2,362

|

Research

|

329

|

+365

|

694

|

604

|

+615

|

1,219

|

Forestry

|

5

|

+0

|

5

|

10

|

+0

|

10

|

Energy

|

362

|

+109

|

471

|

612

|

+125

|

737

|

Horticulture

|

772

|

+250

|

1,022

|

1,547

|

+500

|

2,047

|

Crop Insurance

|

38,057

|

-47

|

38,010

|

78,037

|

-104

|

77,933

|

Miscellaneous

|

1,259

|

+685

|

1,944

|

2,423

|

+738

|

3,161

|

Subtotal

|

426,462

|

+1,820

|

428,282

|

867,200

|

+70

|

867,270

|

- Increase revenue

|

-

|

+35

|

35

|

-

|

+70

|

70

|

Total

|

426,462

|

+1,785

|

428,247

|

867,200

|

+0

|

867,200 Sources: CRS. Compiled from the CBO Baseline by Title (unpublished; April 2018); and CBO cost estimate of the conference agreement for H.R. 2, December 11, 2018. Notes: Baseline for the Credit title is negative because of receipts to the Farm Credit System Insurance Fund. Baseline for the Rural Development "cushion of credit" is accounted for outside of the farm bill | |||||

Source: CRS, using the CBO cost estimate of the Agricultural Act of 2014 (January 28, 2014), and the CBO Budget and Economic Outlook, "10-Year Budget Projections," April 2018.

Notes: "na" indicates sufficient detail is not available to compile data for all titles in non-farm bill years.

|

Figure 2. Projected Outlays Actuals FY2014-2016, Est. FY2017, Projected FY2018 in April 2018 CBO Baseline |

|

|

How Much Has the Farm Bill Cost in the Past?

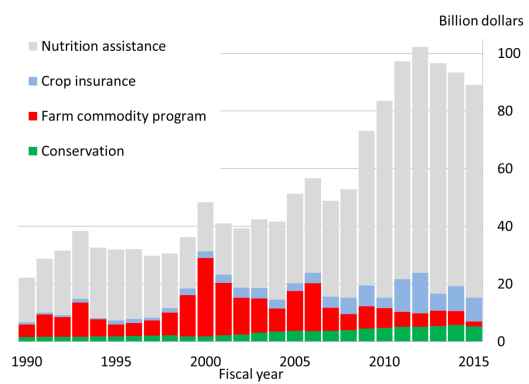

The cost of the farm bill has grown over time, though relative proportions across the major program groups have shifted (Figure 3).

- Conservation program spending has steadily risen as conservation programs have become more numerous and expansive in their authorized scope.

Farm commodity program spending has both risen and fallen with market price conditions and policy responses. For the past decade, though, program costs have generally decreased as counter-cyclical payments were smaller due to higher market prices. (This trend, however, has reversed at least temporarily as shown in the current projections for future farm bill spending [Table 1]).- Crop insurance costs have increased steadily as the program has expanded to cover more commodities and become a primary means for risk management. Higher farm commodity market prices and increased covered acreage have raised the insured value of production and consequently program costs. Crop insurance costs have overtaken the traditional farm commodity programs in total costs.

- Nutrition program assistance in the farm bill (SNAP) rose sharply after the recession in 2009 but has begun to decline more slowly during the recovery.

How Have the Allocations Changed over Time?

The allocation of baseline among titles, and the size of each amount, is not a zero-sum game over time. Every year, CBO reestimates the baseline to determine expected costs. Baseline projections rise and fall based on changes in economic conditions, even without any action by Congress.

For example, when the 2008 farm bill was enacted, the nutrition title was 67% of the five-year total. When the 2014 farm bill was enacted, the nutrition share had risen to 80% (Table 2). This growth in size and proportion does not mean, however, that nutrition grew at the expense of agricultural programs. Legislative changes that are made in each farm bill account for only a fraction of the observed change between farm bills.

- Nutrition. Projected five-year SNAP outlays rose at an annualized rate of 13% per year from enactment of the 2008 farm bill to the 2014 farm bill. This $202 billion increase was entirely from changing economic expectations, since legislative changes in the 2014 farm bill scored a $3.2 billion reduction.8

- Crop insurance. Projected five-year crop insurance outlays rose at an annualized rate of 11% per year from 2008 to 2014—nearly the same rate as SNAP, though smaller in dollars. The $20 billion increase was mostly from changing economic expectations rather than the $1.8 billion increase that was legislated in the farm bill.

- Farm commodity programs. Projected five-year farm commodity program outlays fell at an annualized rate of 9.1% per year between the 2008 and 2014 farm bills, given the $18 billion reduction that was scored from restructuring program payments.

Table 2. Shares and Growth in Projected Farm Bill Outlays from 2008 to 2014

Five-year projected cost of the farm bill at enactment

|

2008 farm bill |

2014 farm bill |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm bill titles |

$ billion |

Share |

$ billion |

Share |

Change in projection $ billion |

Annualized change |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Primary divisions |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nutrition (Mandatory outlays, billions of dollars, FY2019-FY2023)

|

Sources: CRS. Compiled from the CBO Baseline by Title (unpublished, April 2018); and CBO cost estimate of the conference agreement for H.R. 2, December 11, 2018. (millions of dollars, five-year totals, mandatory spending)

|

Selected farm bill titles

|

At enactment, December 2018

|

Most recently, May 2019

|

Projection for FY2019-FY2023

|

Share

|

Projection for FY2019-FY2023

|

Change since enactment

|

Nutrition

|

326,020

|

76.1%

|

321,405

|

-4,615

|

Crop Insurance

|

38,010

|

8.9%

|

40,882

|

+2,872

|

Commodities and Disaster

|

31,440

|

7.3%

|

26,763

|

-4,677

|

Conservation

|

29,270

|

6.8%

|

28,477

|

-793

|

Subtotal, four largest titles

|

424,740

|

99.2%

|

417,527

|

-7,213

|

Total, 12 titles (see Table 1)

|

428,282

|

100.0%

|

na

|

na Source: CRS, using CBO data. See Table 1, and based on CBO data in "Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs," May 2019. Notes: "na" indicates that sufficient detail is not available to compile data for all titles in non-farm-bill years. Figure 3. Actual and Projected Spending by Major Farm Bill Mandatory Programs

|

Source: CRS using USDA and CBO data (through the May 2019 CBO baseline). Notes: Darker shades of each color are actual outlays based on available USDA data; lighter shades are CBO data and projections. Excludes the Trade Aid Program announced in 2018-2019 and supplemental appropriations. (billions of nominal dollars, five-year projection at enactment, mandatory spending)

|

2008 farm bill

|

2014 farm bill

|

2018 farm bill

|

Farm bill titles

|

Amount

|

Share

|

Amount

|

Share

|

Amount

|

Share

|

Overall Nutrition (Title IV) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Rest of the farm bill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Selected agricultural titles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Crop insurance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm commodities (Title I) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subtotal: "Farm safety net" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conservation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Horticulture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total, Entire Farm Bill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Inflation (GDP price index) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Title-by-Title Summaries

of the 2018 Farm BillFollowing are summaries of the major provisions of each title of the The Commodities title authorizes support programs for dairy, sugar, and covered commodities—including major grain, oilseed, and pulse crops—as well as agricultural disaster assistance. The 2018 farm bill extends authority for most current commodity programs but with some modifications. Major field-crop programs include Price Loss Coverage (PLC), Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC), and Marketing Assistance Loans (MAL). The new dairy program protects a portion of the margin between milk and feed prices. The sugar program provides a combination of price supports, limits on imports, and processor/refiner marketing allotments. Four disaster assistance programs focus primarily on livestock and tree crops. Title I also includes several administrative provisions that set payment limits, an adjusted gross income (AGI) threshold, and other details for payment attribution and eligibility. The 2018 farm bill provides producers the flexibility of switching between ARC and PLC coverage under certain conditions. Producers can update their program yields for the PLC, and an escalator provision was added that could potentially raise a covered commodity's effective reference price. For ARC, data from the Risk Management Agency become the primary source for county average yields, which is intended to avoid cross-county disparities in payments. For the marketing assistance loan program, rates are increased for several crops, including barley, corn, grain sorghum, oats, extra-long-staple cotton, rice, soybeans, dry peas, lentils, and small and large chickpeas. Regarding payment limitations, the definition of family farm is expanded to include first cousins, nieces, and nephews, thus increasing eligibility. For dairy, a new Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program adds higher levels of margin coverage, provides for lower producer-paid premium rates for 5 million pounds or less of milk production, and allows producers to cover a larger percentage of milk production compared with the 2014 Margin Protection Program. Under DMC, premiums were designed to incentivize higher levels of coverage. Producers may participate in both margin coverage and the Livestock Gross Margin-Dairy insurance program that insures the margin between feed costs and a designated milk price. The Conservation title provides assistance to agricultural producers by addressing environmental resource concerns on private land through land retirement, conservation easements, working lands assistance, and partnership opportunities. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes and amends many of the largest conservation programs and creates a number of new pilot programs, carve-outs, and initiatives. The two largest working lands programs—Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP)—were reauthorized and amended. Enrollment for CSP is reduced and funds are shifted, in part, to EQIP and other farm bill conservation programs. EQIP is expanded to irrigation and drainage entities, and additional funding carve-outs and pilot projects are authorized. The largest land retirement program—the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP)—is reauthorized and expanded by incrementally increasing the enrollment limit from 24 million acres in FY2019 to 27 million acres by FY2023. CRP payments to participants are reduced, and additional subprograms are authorized. The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is redefined as a stand-alone program with separate contracts and an expanded scope of eligible projects. Agricultural land easements in the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) are amended to provide additional flexibility to eligible entities. The Trade title addresses U.S. agricultural export programs and U.S. international food assistance programs. Major programs support agricultural trade promotion and facilitation, such as the Market Access Program, and the primary U.S. international food assistance program, Food for Peace (FFP) Title II. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes existing U.S. export promotion programs and consolidates four programs into a new Agricultural Trade Promotion and Facilitation Program (ATPFT) that establishes permanent mandatory funding. It also establishes a Priority Trade Fund within ATPFT. The enacted law also reauthorizes direct credits or export credit guarantees for the promotion of agricultural exports to emerging markets. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes all international food assistance programs as well as certain operational details such as prepositioning of agricultural commodities and micronutrient fortification. It also adds a provision requiring that food vouchers, cash transfers, and local and regional procurement of non-U.S. foods avoid market disruption in the recipient country. The 2018 farm bill amends FFP Title II by eliminating the requirement to monetize—that is, sell on local markets to fund development projects—at least 15% of FFP Title II commodities. It also increases the minimum level of FFP Title II funds allocated for nonemergency assistance. The 2018 farm bill also reauthorizes and/or amends other international food assistance programs, including the McGovern-Dole program. For the SNAP Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) system, the 2018 farm bill places limits on fees, shortens the time frame for unused benefits, and changes the authorization requirements for some farmers' market operators. It requires nationwide online acceptance of SNAP benefits and authorizes a pilot project about recipients' use of mobile technology to redeem SNAP benefits. The 2018 farm bill further reauthorizes, renames, and expands the Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive (FINI, now the Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program), a grant program for projects that incentivize SNAP and other low-income participants' purchase of fruits and vegetables. The 2018 farm bill also continues funding for the Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program and reauthorizes but reduces funding for the Community Food Projects grants. It also reauthorizes and revises food distribution programs. Supporting emergency feeding organizations, the bill reauthorizes TEFAP and authorizes new projects to facilitate the donation of raw/unprocessed commodities. The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations now requires the federal government to pay at least 80% of administrative costs and includes a demonstration project for tribes to purchase their own commodities. The Credit title offers direct government loans to farmers/ranchers and guarantees on private lenders' loans. For the USDA farm loan programs, the enacted law adds criteria that may be used to reduce a three-year farming experience requirement. It raises the maximum loan size for guaranteed loans by about 25%. It further doubles the limit for direct farm ownership loans and increases the direct operating loan limit by one-third. Beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers may benefit from a higher guarantee percentage on loans. For the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (known as FarmerMac), the 2018 farm bill increases an acreage exception to remain a qualified loan. For the Farm Credit System Insurance Corporation, the farm bill provides greater statutory guidance about its conservatorship and receivership authorities, which are largely modeled after the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. It also reauthorizes the State Agricultural Loan Mediation Program and expands the range of eligible issues. The Rural Development title supports rural business and community development. The 2018 farm bill makes changes to existing USDA programs. It temporarily prioritizes public health emergencies and substance use disorder, including in the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Program, the Community Facilities Program, and the Rural Health and Safety Education Program. For rural broadband deployment, the 2018 farm bill authorizes the Rural Broadband Access Program to provide grants in addition to direct and guaranteed loans and increases the minimum acceptable speed levels for broadband service. The farm bill reauthorizes the Rural Energy Savings Program and amends the program to allow off-grid and energy storage systems. It amends the definition of rural to exclude individuals incarcerated on a "long-term or regional basis" and excludes the first 1,500 individuals who reside in housing located on military bases. The 2018 farm bill further provides that areas defined as rural between 1990 and 2020 may remain so until the 2030 census. It amends the Cushion of Credit Payments Program for rural utilities to cease new deposits and to modify the interest rate. The Research title supports agricultural research at the federal level and provides support for cooperative research, extension, and postsecondary agricultural education programs. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes several existing programs and establishes new programs and initiatives. The 2018 farm bill also amends and reauthorizes funding for the competitively awarded Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI), Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative (OREI), and Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI). It reauthorizes the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP), which distributes funds to eligible applicants on a formula basis. It enhances mandatory funding and requires a strategic plan for the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR). Among new programs and initiatives, the 2018 farm bill establishes the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority Pilot, research Centers of Excellence at 1890 Institutions (historically black land-grant colleges and universities), and competitive grants programs to benefit tribal students and those at 1890 Institutions. It also establishes new competitive research and extension grants for hemp research and indoor and urban agriculture. The Forestry title supports forestry management programs run by USDA's Forest Service. The 2018 farm bill continues provisions related to forestry research and provides financial and technical assistance to nonfederal forest landowners. It also includes several provisions addressing management of the National Forest System lands managed by the Forest Service and the public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management in the Department of the Interior.16 It reauthorizes the Healthy Forests Reserve Program, Rural Revitalization Technology, National Forest Foundation, and funding for implementing statewide forest resource assessments. It authorizes financial assistance for large restoration projects that cross landownership boundaries. The enacted law also addresses issues related to the accumulation of biomass and the associated risk for uncharacteristic wildfires. The 2018 farm bill changes how the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management comply with the National Environmental Policy Act for management of sage grouse and mule deer habitat. It also changes the Forest Service's authority to designate insect and disease treatment areas and procedures intended to expedite the environmental analysis. It establishes two watershed protection programs on National Forest System lands and authorizes acceptance of cash or in-kind donations for those programs. The Energy title encourages the development of biofuels and farm and community renewable energy systems through grants, loan guarantees, and a feedstock procurement initiative. It also supports increases in energy efficiency as well as the development of biobased products. The 2018 farm bill extends eight programs and one initiative through FY2023, repeals one program and one initiative (the Repowering Assistance Program and the Rural Energy Self-Sufficiency Initiative), and establishes one new grant program (the Carbon Utilization and Biogas Education Program). It amends the Biomass Crop Assistance Program to include algae. It also modifies the definitions of biobased product (to include renewable chemicals), biorefinery (to include the conversion of an intermediate ingredient or feedstock), and renewable energy systems (to include ancillary infrastructure such as a storage system). Compared to previous farm bills, the 2018 farm bill provides less mandatory funding for existing USDA energy programs. The Horticulture title supports specialty crops—as defined in statute, covering fruits, vegetables, tree nuts, and nursery products—through a range of initiatives, including market promotion, plant pest and disease prevention, and public research. The title also provides support to certified organic agricultural production and locally produced foods. The 2018 farm bill reauthorizes many of these provisions, including block grants to states, support for farmers markets, data and information collection, education on food safety and biotechnology, and organic certification. Provisions affecting the specialty crop, certified organic, and local foods sectors are not limited to the Horticulture title (Title X) but are contained within several other titles, including the Research, Nutrition, and Trade titles. The 2018 farm bill expands and adds funding for farmers markets and local food promotion programs by combining existing programs to create a new Local Agriculture Market Program. Other provisions supporting local and urban agriculture development are housed in the Miscellaneous, Research, Conservation, and Crop Insurance titles.19 The 2018 farm bill makes changes to USDA's National Organic Program (NOP) and related programs, addressing concerns about organic import integrity by including provisions that strengthen the tracking, data collection, and investigation of organic product imports. It also expands mandatory funding for the National Organic Certification Cost Share Program and expands support for technology upgrades to improve tracking and verification of organic imports. The 2018 farm bill authorizes establishing a regulatory framework for the cultivation of hemp (as defined in statute) and creates a new regulatory program for hemp production under USDA's oversight. Related provisions expand the statutory definition of hemp and expand eligibility to produce hemp to a broader set of producers and groups, including tribes and territories. Provisions in other titles further expand support for hemp, including making hemp eligible for federal crop insurance and certain USDA research programs, as well as excluding hemp from the statutory definition of marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act.20 The Crop Insurance title modifies the permanently authorized Federal Crop Insurance Act. The federal crop insurance program offers subsidized policies to farmers to protect against losses in yield, crop revenue, or whole farm revenue. The 2018 farm bill makes several modifications. It expands coverage by authorizing catastrophic policies for forage and grazing crops and grasses. It also allows producers to purchase separate crop insurance policies for crops that can be both grazed and mechanically harvested on the same acres and to receive independent indemnities for each intended use. For crop insurance research and development, the farm bill redefines beginning farmer or rancher as an individual having actively operated and managed a farm or ranch for less than 10 years. This redefinition makes these individuals eligible for federal subsidy benefits of whole-farm insurance plans. The law also allows waivers of certain viability and marketability requirements for developing a policy or pilot program for the production of hemp. It further adds hemp (as defined in statute) as an eligible crop for federal crop insurance and to the limited list of crops that cover post-harvest losses. The Miscellaneous title covers a wide array of issues across six subtitles, including livestock, agriculture and food defense, historically underserved producers, Department of Agriculture Reorganization Act of 1994 Amendments, and other general provisions. The livestock provisions establish the National Animal Disease Preparedness Response Program and the National Animal Vaccine and Veterinary Countermeasures Bank. Other livestock provisions authorize appropriations for the Sheep Production and Marketing Grant Program; add llamas, alpacas, live fish, and crawfish to the list of covered animals under the Emergency Livestock Feed Assistance Act; and establish regional cattle and carcass grading centers. Other animal-related provisions ban the slaughter of dogs and cats, impose a ban on animal fighting in U.S. territories, and require a report on the importation of dogs. The Miscellaneous title includes a number of other provisions covering a wide range of policy issues. Among these, it directs USDA to restore certain exemptions for inspection and weighing services that were included in the United States Grain Standards Act but were rescinded by USDA when the act was reauthorized in 2015. It amends the Controlled Substances Act to exclude hemp (as defined in statute) from the statutory definition of marijuana. The enacted law also establishes the Farming Opportunities Training and Outreach program by combining and expanding existing programs for beginning, limited resource, and socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers.21 It further extends outreach and technical assistance programs for socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers and adds military veteran farmers and ranchers as a qualifying group. It also creates a military veterans agricultural liaison within USDA to advocate for and provide information to veterans and establishes an Office of Tribal Relations to coordinate USDA activities with Native American tribes.22 The enacted law requires USDA to conduct additional planning and monitoring of plant disease and pest concerns and reauthorizes policies supporting citrus growers and cotton and wool apparel manufacturers. Author Contact Information See CRS Report R45210, Farm Bills: Major Legislative Actions, 1965-2018. Since the 1930s, there have been 18 farm bills (2018, 2014, 2008, 2002, 1996, 1990, 1985, 1981, 1977, 1973, 1970, 1965, 1956, 1954, 1949, 1948, 1938, and 1933). See also CRS In Focus IF11126, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: What Is the Farm Bill? See CRS Report R45525, The 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison. For example, in 2012 Congress did not complete a new farm bill to replace the 2008 law, requiring a one-year extension for both FY2013 and crop year 2013. In 2013, Congress passed bills that culminated in the 2014 farm bill. Some programs, though, ceased to operate during the 2013 extension because they had no funding. For background, see CRS Report R41433, Programs Without a Budget Baseline at the End of the 2008 Farm Bill. See CRS Report R45341, Expiration of the 2014 Farm Bill. See CRS Report R45425, Budget Issues That Shaped the 2018 Farm Bill. CBO cost estimate of H.R. 2, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, December 11, 2018. CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, "10-Year Budget Projections," May 2019; and programmatic details available in "Details About Baseline Projections for Selected Programs," May 2019. See CRS In Focus IF11163, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: The Farm Safety Net; CRS In Focus IF11164, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Title I Commodity Programs; and CRS In Focus IF11188, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Dairy Programs. See CRS Report R45698, Agricultural Conservation in the 2018 Farm Bill; or CRS In Focus IF11199, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Title II Conservation Programs. See CRS In Focus IF11223, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Agricultural Trade and Food Assistance. See CRS In Focus IF11087, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: SNAP and Nutrition Title Programs. See CRS In Focus IF11225, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Rural Development Programs. See CRS In Focus IF11319, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Agricultural Research and Extension. See CRS In Focus IF10681, Farm Bill Primer: Forestry Title. See CRS Report R45696, Forest Management Provisions Enacted in the 115th Congress. See CRS In Focus IF10639, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Energy Title. See CRS In Focus IF11317, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Specialty Crops and Organic Agriculture. See CRS In Focus IF11252, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Support for Local Food Systems; and CRS In Focus IF11210, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Support for Urban Agriculture. See CRS In Focus IF11088, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Hemp Cultivation and Processing. See CRS In Focus IF11227, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Beginning Farmers and Ranchers.20142018 farm bill. For more detailed information, see CRS Report R43076R45525, The 20142018 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79115-334): Summary and Side-by-Side Comparison.

Title I: Commodities9

Footnotes

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

See CRS In Focus IF11093, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Veteran Farmers and Ranchers): Summary and Side-by-Side, which compares the provisions in the final 2014 farm bill to previous law and the House- and Senate-passed versions of the farm bill.

Title I: Commodity Programs9

Under the enacted 2014 farm bill, farm support for traditional commodity crops—grains, oilseeds, and cotton—is restructured by eliminating what were formerly known as direct payments, the counter-cyclical program, and the Average Crop Revenue Election program.10 Under the 2014 farm bill, producers may choose between two programs that respond to declines in either price or revenue: (1) Price Loss Coverage (PLC), which is a counter-cyclical price program that makes a farm payment when the farm price of a covered crop declines below its statutory "reference price"; and (2) Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC), which is a revenue-based program designed to cover a portion of a farmer's out-of-pocket loss (referred to as "shallow loss") when crop revenue declines. These farm programs are separate from a producer's decision to purchase crop insurance (Title XI).

The 2014 farm bill makes significant changes to U.S. dairy policy by eliminating the dairy product price support program, the Milk Income Loss Contract (MILC) program, and export subsidies. These are replaced by a new program that makes payments to participating dairy producers when the national margin (average farm price of milk minus an average feed cost calculation) falls below a producer-selected margin. The farm bill does not change the objective and structure of the U.S. sugar program. The 2014 farm bill also sets a $125,000 per person cap on the total of PLC, ARC, marketing loan gains, and loan deficiency payments. It also makes changes to the eligibility requirement based on adjusted gross income (AGI), setting a new limit to a single, total AGI limit of $900,000.

For disaster assistance,11 Title I reauthorizes and funds four programs covering livestock and tree assistance. Coverage is retroactive beginning with FY2012 and continues without expiration. The crop disaster program from the 2008 farm bill (the Supplemental Revenue Assistance, or SURE) was not reauthorized, but elements of it are folded into the new ARC program by allowing producers to protect against farm-level revenue losses.

Title II: Conservation12

Prior to the 2014 farm bill, the agricultural conservation portfolio included over 20 programs. The bill reduces and consolidates the number of conservation programs, and reduces mandatory funding. It reauthorizes many of the larger existing programs, such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), and rolled smaller and similar conservation programs into two new programs—the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). Previous easement programs related to wetlands, grasslands, and farmland protection were repealed and consolidated to create ACEP, which retains most of the provisions by establishing two types of easements: wetland reserve easements that protect and restore wetlands, and agricultural land easements that prevent non-agricultural uses on productive farm or grasslands. Previous programs that focused on agricultural water enhancement, and two programs related to the Chesapeake Bay and Great Lakes, were repealed and consolidated into the new RCPP, which partners with state and local governments, Indian tribes, cooperatives, and other organizations for conservation on a regional or watershed scale.

The 2014 farm bill also adds the federally funded portion of crop insurance premiums to the list of program benefits that could be lost if a producer is found to produce an agricultural commodity on highly erodible land without implementing an approved conservation plan or qualifying exemption, or converts a wetland to crop production. This prerequisite, referred to as conservation compliance, has existed since the 1985 farm bill and previously affected most USDA farm program benefits, but has excluded crop insurance since 1996.

Title III: Trade13

The 2014 farm bill reauthorized and amended USDA's food aid, export market development, and export credit guarantee programs. The bill reauthorizes all of the international food aid programs—including the largest, Food for Peace Title II (emergency and nonemergency food aid). It also amends existing food aid law to place greater emphasis on improving the nutritional quality of food aid products and ensuring that sales of agricultural commodity donations do not disrupt local markets. The bill creates a new local and regional purchase program in place of the expired local and regional procurement (LRP) pilot program of the 2008 farm bill and increases the authorized appropriations for the program.

The 2014 farm bill also reauthorizes funding for the Export Credit Guarantee program and three other agricultural export market promotion programs, including the Market Access Program (MAP), which finances promotional activities for both generic and branded U.S. agricultural products, and the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP), which is a generic commodity promotion program. It also made changes to the credit guarantee program to comply with the WTO cotton case against the United States won by Brazil, and proposes a plan to reorganize the trade functions of USDA, including establishing an agency position to coordinate sanitary and phytosanitary matters and address agricultural non-tariff trade barriers across agencies.

Title IV: Nutrition14

The 2014 farm bill's nutrition title accounts for 80% of the law's forecasted spending. The majority of the law's Nutrition funding and policies pertain to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides benefits redeemable for eligible foods at eligible retailers to eligible, low-income individuals. The bill reauthorizes SNAP and The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP, the program that provides USDA foods and federal support to emergency feeding organizations such as food banks and food pantries). The bill retains most of the eligibility and benefit calculation rules in SNAP. However, it does amend how Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) payments are treated to calculate SNAP benefits.15 It disqualifies certain ex-offenders from receiving SNAP benefits if they do not comply with the terms of their sentence. The law establishes a number of new policies related to the SNAP Employment and Training (E&T) program, including a pilot project for work programs for SNAP participants.16 The bill makes changes to SNAP law pertaining to retailer authorization and benefit issuance and redemption, including requiring stores to stock a greater variety of foods and more fresh foods, requiring retailers to pay for their electronic benefit transfer (EBT) machines, and providing additional funding for combatting trafficking (the sale of SNAP benefits). It also includes new federal funding to support organizations that offer bonus incentives for SNAP purchases of fruits and vegetables (called Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive grants). It also includes other changes to SNAP and related programs, including amendments to the nutrition programs operated by tribes and territories, the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP), and the distribution of USDA foods to schools.17

Title V: Credit18

The 2014 farm bill makes relatively minor changes to the permanent statutes for two types of farm lenders: the USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) and the Farm Credit System (FCS). It gives USDA discretion to recognize alternative legal entities to qualify for farm loans and allow alternatives to meet a three-year farming experience requirement. It increases the maximum size of down-payment loans, and eliminates term limits on guaranteed operating loans (by removing a maximum number of years that an individual can remain eligible). It increases the percentage of a conservation loan that can be guaranteed, adds another lending priority for beginning farmers, and facilitates loans for the purchase of highly fractionated land in Indian reservations.

Title VI: Rural Development19

The 2014 farm bill reauthorizes and/or amends rural development loan and grant programs and authorizes several new provisions, including rural infrastructure, economic development, and broadband and telecommunications development.20 The bill reauthorizes funding for programs under the Rural Electrification Act of 1936, including access to broadband and the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Program. It reauthorizes the Northern Great Plains Regional Authority and the three regional authorities established in the 2008 farm bill. It also increases funding for several programs, including the Value-Added Agricultural Product Grants, rural development loans and grants, and the Microentrepreneur Assistance Program. It retains the definition of "rural" and "rural area" under current law for purposes of program eligibility. However, it amends the definition of rural area in the 1949 Housing Act so that areas deemed rural retain their designation until the 2020 decennial census and raises the population threshold for eligibility from 25,000 to 35,000.

Title VII: Research21

USDA conducts agricultural research at the federal level and provides support for cooperative research, extension, and post-secondary agricultural education programs. The 2014 farm bill reauthorizes funding for these activities through FY2018, subject to appropriations, and amends authority so that only competitive grants can be awarded under certain programs. Mandatory spending for the research title is increased for several programs, including the Specialty Crop Research Initiative and the Organic Agricultural Research and Extension Initiative. Also, mandatory funding is continued for the Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program. The bill provides mandatory funding to establish the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, a nonprofit corporation designed to accept private donations and award grants for collaborative public/private partnerships among USDA, academia, and the private sector.

Title VIII: Forestry22

General forestry legislation is within the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Committees, and past farm bills have included provisions addressing forestry assistance, especially on private lands. The 2014 farm bill generally repeals, reauthorizes, and modifies existing programs and provisions under two main authorities: the Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act (CFAA), as amended, and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (HFRA), as amended. Many federal forestry assistance programs are permanently authorized, and thus do not require reauthorization in the farm bill. However, the 2014 farm bill reauthorizes several other forestry assistance programs through FY2018. It also repeals programs that have expired or have never received appropriations. The bill also includes provisions that address the management of the National Forest System, and also authorizes the designation of treatment areas within the National Forest System that are of deteriorating forest health due to insect or disease infestation, and allows for expedited project planning within those designated areas.

Title IX: Energy23

USDA renewable energy programs encourage research, development, and adoption of renewable energy projects, including solar, wind, and anaerobic digesters. However, the primary focus of these programs has been to promote U.S. biofuels production and use. Cornstarch-based ethanol dominates the U.S. biofuels industry. Earlier, the 2008 farm bill refocused U.S. biofuels policy initiatives in favor of non-corn feedstocks, especially the development of the cellulosic biofuels industry. The most critical programs to this end are the Bioenergy Program for Advanced Biofuels (pays producers for production of eligible advanced biofuels); the Biorefinery Assistance Program (assists in the development of new and emerging technologies for advanced biofuels); the Biomass Crop Assistance Program, BCAP (assists farmers in developing nontraditional crops for use as feedstocks for the eventual production of cellulosic biofuels); and the Renewable Energy for America Program, REAP (funds a variety of biofuels-related projects). The 2014 farm bill extends many of the renewable energy provisions of the 2008 farm bill through FY2018.

Title X: Horticulture and Organic Agriculture24

The 2014 farm bill reauthorizes many of the existing farm bill provisions supporting farming operations in the specialty crop and certified organic sectors. Many provisions fall into the categories of marketing and promotion; organic certification; data and information collection; pest and disease control; food safety and quality standards; and local foods. The bill provides increased funding for several key programs that benefit specialty crop producers. These include the Specialty Crop Block Grant Program, plant pest and disease programs, USDA's Market News for specialty crops, the Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI), and the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program (Snack Program) and Section 32 purchases for fruits and vegetables under the Nutrition title. The final law also reauthorizes most programs benefitting certified organic producers provisions as well as provisions that expand opportunities for local food systems and also beginning farmers and ranchers. Provisions affecting the specialty crop and certified organic sectors are not limited to this title but are also contained within several other titles of the farm bill such as the research, nutrition, and trade titles.

Title XI: Crop Insurance25

The crop insurance title enhances the permanently authorized Federal Crop Insurance Act. The federal crop insurance program makes available subsidized crop insurance to producers who purchase a policy to protect against losses in yield, crop revenue, or whole farm revenue. More than 100 crops are insurable. The 2014 farm bill increases funding for crop insurance relative to baseline levels, most of which is for two new insurance products, one for cotton and one for other crops. A new crop insurance policy called Stacked Income Protection Plan (STAX) is made available for cotton producers, since cotton is not covered by the new counter-cyclical price or revenue programs in Title I. For other crops, the 2014 farm bill makes available an additional policy called Supplemental Coverage Option (SCO), based on expected county yields or revenue, to cover part of the deductible under the producer's underlying policy (referred to as a farmer's out-of-pocket loss or "shallow loss"). Additional crop insurance changes in the 2014 farm bill are designed to expand or improve crop insurance for other commodities, including specialty crops. New provisions revise the value of crop insurance for organic crops to reflect the higher prices of organic crops rather than conventional crops. Finally, USDA is required to conduct more research on whole farm revenue insurance with higher coverage levels than currently available.

Title XII: Miscellaneous

The miscellaneous title in the 2014 farm bill includes various provisions affecting livestock production, socially disadvantaged and limited-resource producers, oilheat efficiency, research, and jobs training, among other provisions.

The livestock provisions include animal health-related and animal welfare provisions, creation of a production and marketing grant program for the sheep industry, and requirements that USDA finalize the rules on catfish inspection and also conduct a study of its country-of-origin labeling (COOL) rule.26

The farm bill also extends authority for outreach and technical assistance programs for socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers and adds military veteran farmers and ranchers as a qualifying group. It creates a military veterans agricultural liaison within USDA to advocate for and to provide information to veterans, and establishes an Office of Tribal Relations to coordinate USDA activities with Native American tribes. Other provisions establish grants for maple syrup producers and trust funds for cotton and wool apparel manufacturers and citrus growers, and also provide technological training for farm workers.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

There have been 17 farm bills since the 1930s (2014, 2008, 2002, 1996, 1990, 1985, 1981, 1977, 1973, 1970, 1965, 1956, 1954, 1949, 1948, 1938, and 1933). Farm bills have become increasingly omnibus in nature since 1973, when the nutrition title was included. |

| 2. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43076, The 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79): Summary and Side-by-Side. |

| 3. |

For example, in 2012, the 112th Congress did not complete a new farm bill to replace the 2008 law, requiring a one-year extension for 2013. The 113th Congress passed reintroduced and revised bills, culminating in the 2014 farm bill. Some programs, though, still ceased to operate during the 2013 extension because they had no funding. For background, see CRS Report R41433, Programs Without a Budget Baseline at the End of the 2008 Farm Bill. |

| 4. |

For more information on the consequences of expiration, see CRS Report R42442, Expiration and Extension of the 2008 Farm Bill. |

| 5. |

For more background, see CRS Report R42484, Budget Issues That Shaped the 2014 Farm Bill. |

| 6. |

CBO cost estimate of the Agricultural Act of 2014, January 28, 2014, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/45049. |

| 7. |

Congressional Budget Office, Budget and Economic Outlook, "10-Year Budget Projections," various updates, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget_economic_data. |

| 8. |

See CRS Report R42484, Budget Issues That Shaped the 2014 Farm Bill. |

| 9. |

For more on farm commodity programs, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R43448, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

| 10. |

For background on the 2008 farm commodity programs that were replaced by the 2014 farm bill, see CRS Report RL34594, Farm Commodity Programs in the 2008 Farm Bill (available upon request to CRS). |

| 11. |

For more information on disaster programs, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report RS21212, Agricultural Disaster Assistance. |

| 12. |

For more on conservation programs, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R40763, Agricultural Conservation: A Guide to Programs. |

| 13. |

For more on international food aid, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]); for agricultural export programs, contact Mark McMinimy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS In Focus IF10194, U.S. International Food Aid Programs, and CRS Report R43905, Major Agricultural Trade Issues in the 115th Congress. |

| 14. |

For more nutrition programs, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R42353, Domestic Food Assistance: Summary of Programs. |

| 15. |

CRS Report R42591, The 2014 Farm Bill: Changing the Treatment of LIHEAP Receipt in the Calculation of SNAP Benefits. |

| 16. |

The bill does not include changes to broad-based categorical eligibility or a state option to drug test SNAP applicants; these options has been included in House proposals. |

| 17. |

The 2010 child nutrition reauthorization (Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, P.L. 111-296) had already reauthorized some nutrition programs through FY2015, but the 2014 farm bill included certain related policy changes. |

| 18. |

For more on agricultural credit, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report RS21977, Agricultural Credit: Institutions and Issues. |

| 19. |

For more on rural development, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report RL31837, An Overview of USDA Rural Development Programs. |

| 20. |

The Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act is the permanent statute that authorizes USDA agricultural credit and rural development programs. The Farm Credit Act of 1971, as amended, is the permanent statute that authorizes the Farm Credit System. See CRS Report RS21977, Agricultural Credit: Institutions and Issues. |

| 21. |

For more on agricultural research, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R40819, Agricultural Research: Background and Issues. |

| 22. |

For more on forestry, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report RL31065, Forestry Assistance Programs. |

| 23. |

For more on farm bill energy programs, contact Mark McMinimy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R43416, Energy Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79): Status and Funding. |

| 24. |

For more on horticulture, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R42771, Fruits, Vegetables, and Other Specialty Crops: Selected Farm Bill and Federal Programs. |

| 25. |

For more on crop insurance, contact [author name scrubbed] ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed]). See CRS Report R40532, Federal Crop Insurance: Background. |

| 26. |

|