Unauthorized Aliens’ Access to Federal Benefits: Policy and Issues

Federal law bars aliens residing without authorization in the United States from most federal benefits; however, there is a widely held perception that many unauthorized aliens obtain such benefits. The degree to which unauthorized resident aliens should be accorded certain rights and privileges as a result of their residence in the United States, along with the duties owed by such aliens given their presence, remains the subject of debate in Congress. This report focuses on the policy and legislative debate surrounding unauthorized aliens’ access to federal public benefits.

Except for a narrow set of specified emergency services and programs, unauthorized aliens are not eligible for federal public benefits. The law (§401(c) of P.L. 104-193) defines federal public benefit as

any grant, contract, loan, professional license, or commercial license provided by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States; and any retirement, welfare, health, disability, public or assisted housing, postsecondary education, food assistance, unemployment benefit, or any other similar benefit for which payments or assistance are provided to an individual, household, or family eligibility unit by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States.

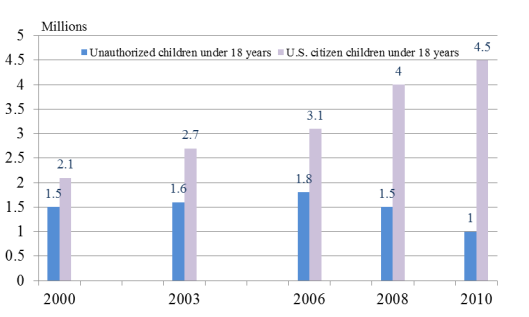

The actual number of unauthorized aliens in the United States is unknown. Researchers at Pew Research Center estimate that there were 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States in March 2014. A noteworthy portion of the households headed by unauthorized aliens are likely to have U.S. citizen children, as well as spouses who may be legal permanent residents (LPRs), and are referred to as “mixed status” families. The number of U.S. citizen children in “mixed status” families has grown from 2.7 million in 2003 to 4.5 million in 2010. (This is the latest figure available as of the date of the report.)

Although the law appears straightforward, the policy on unauthorized aliens’ access to federal public benefits is peppered with ongoing controversies and debates. Some center on demographic issues, such as how to treat mixed-immigration-status families. Others explore unintended consequences, most notably when tightening up the identification requirements results in denying benefits to U.S. citizens. Still others are debates about how broadly the clause “federal public benefit” should be implemented, particularly regarding tax credits and refunds.

Unauthorized Aliens' Access to Federal Benefits: Policy and Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Unauthorized Population in the United States

- "Quasi-legal" Migrants

- Mixed-Immigration-Status Families

- Benefit Eligibility Rules

- Pre-1996 Policies

- Program Rules

- PRUCOL

- Current Federal Law

- Higher Education Benefits

- State Benefits

- Determining Status and Eligibility

- Immigrant Verification

- Citizenship Verification

- Receipt of Benefits

- Selected Issues

- Treatment of Mixed-Status Families

- Expansion of Documentary Requirements

- Scope of "Federal Public Benefits" Clause for Tax Refunds

- Competing Priorities for Emergency Relief

- Re-emergence of PRUCOL with "Quasi-legal" Migrants

- Refinement or Revisions of the Rules

Summary

Federal law bars aliens residing without authorization in the United States from most federal benefits; however, there is a widely held perception that many unauthorized aliens obtain such benefits. The degree to which unauthorized resident aliens should be accorded certain rights and privileges as a result of their residence in the United States, along with the duties owed by such aliens given their presence, remains the subject of debate in Congress. This report focuses on the policy and legislative debate surrounding unauthorized aliens' access to federal public benefits.

Except for a narrow set of specified emergency services and programs, unauthorized aliens are not eligible for federal public benefits. The law (§401(c) of P.L. 104-193) defines federal public benefit as

any grant, contract, loan, professional license, or commercial license provided by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States; and any retirement, welfare, health, disability, public or assisted housing, postsecondary education, food assistance, unemployment benefit, or any other similar benefit for which payments or assistance are provided to an individual, household, or family eligibility unit by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States.

The actual number of unauthorized aliens in the United States is unknown. Researchers at Pew Research Center estimate that there were 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States in March 2014. A noteworthy portion of the households headed by unauthorized aliens are likely to have U.S. citizen children, as well as spouses who may be legal permanent residents (LPRs), and are referred to as "mixed status" families. The number of U.S. citizen children in "mixed status" families has grown from 2.7 million in 2003 to 4.5 million in 2010. (This is the latest figure available as of the date of the report.)

Although the law appears straightforward, the policy on unauthorized aliens' access to federal public benefits is peppered with ongoing controversies and debates. Some center on demographic issues, such as how to treat mixed-immigration-status families. Others explore unintended consequences, most notably when tightening up the identification requirements results in denying benefits to U.S. citizens. Still others are debates about how broadly the clause "federal public benefit" should be implemented, particularly regarding tax credits and refunds.

Introduction

The number of foreign-born people residing in the United States (42.4 million) is at the highest level in our history and, as a portion of the U.S. population, has reached a percentage (13%) not seen since the early 20th century.1 Of the foreign-born residents in the United States, approximately 11 million are speculated to be unauthorized residents (often characterized as illegal aliens).2

The degree to which unauthorized resident aliens should be accorded certain rights and privileges as a result of their residence in the United States, along with the duties owed by such aliens given their presence, remains the subject of debate in Congress.3 Included among the specific policy areas that spark controversy are due process rights, tax liabilities, military service, eligibility for federal assistance, educational opportunities, and pathways to citizenship. This report focuses on the policy and legislative debate surrounding unauthorized aliens' access to federal benefits.4

Unauthorized Population in the United States

Researchers at Pew Research Center estimate that there were 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States in March 2014.5 The three main components of the unauthorized resident alien population are foreign nationals who overstay their nonimmigrant visas, foreign nationals who enter the country surreptitiously, and foreign nationals who are admitted on the basis of fraudulent documents. In all three instances, these aliens are in violation of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and subject to removal. Nonetheless, the actual number of unauthorized aliens in the United States is not known, as locating and enumerating people who are residing in the United States without permission poses many methodological problems.6

"Quasi-legal" Migrants

Not all unauthorized aliens lack legal documents, leading many observers to characterize these documented aliens as "quasi-legal" migrants. Specifically, there are certain circumstances in which DHS issues temporary employment authorization documents (EADs) to aliens who are not otherwise considered authorized to reside in the United States. Aliens with EADs, in turn, may legally obtain Social Security cards.7 These "quasi-legal" unauthorized aliens fall in several categories:

- Those who received from the Government temporary humanitarian relief from removal, such as Temporary Protected Status (TPS).8

- Those eligible for deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA).9

- Those who sought asylum in the United States and their cases have been pending for at least 180 days.10

- Those who are immediate family or fiancées of legal permanent residents (LPRs) who are awaiting in the United States their legal permanent residency cases to be processed.11

- Those who have overstayed their nonimmigrant visas and have petitions pending to adjust status as employment-based LPRs.12

None of the aliens described above have been formally approved to remain in the United States permanently, and many with pending cases may ultimately be denied LPR status. Only about 25% of asylum seekers, for example, ultimately gain asylum.13 Approximately 80% to 85% of LPR petitions reportedly are approved.14

Abused, neglected, or abandoned children who also lack authorization under immigration law to reside in the United States (i.e., unauthorized aliens) raise complex immigration and child welfare concerns. In 1990, Congress created an avenue for unauthorized alien children who become dependents of the state juvenile courts to remain in the United States legally and permanently. Any child or youth under the age of 21 who was born in a foreign country; lives without legal authorization in the United States; has experienced abuse, neglect, or abandonment; and meets other specified eligibility criteria may be eligible for special immigrant juvenile (SIJ) status. Otherwise, unauthorized residents who are minors are subject to removal proceedings and deportation, as are all other unauthorized foreign nationals. The SIJ classification enables unauthorized juveniles who become dependents of the state juvenile court to become LPRs under the INA.15

Mixed-Immigration-Status Families

A noteworthy portion of the households headed by unauthorized aliens is likely to have U.S. citizen children, as well as spouses who may be legal permanent residents. Children born in the United States to parents who are unlawfully present in the United States are U.S. citizens, consistent with the British common law principle known as jus soli. This principle is codified in the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and by Section 301(a) of the INA, which provides that a person who is born in the United States, subject to its jurisdiction, is a citizen of the United States regardless of the race, ethnicity, or alienage of the parents.16

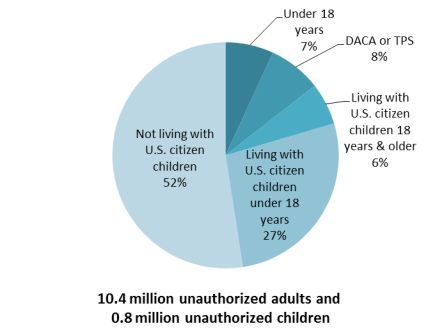

As Figure 1 illustrates, an estimated 27% of unauthorized adults (3.1 million) are living with U.S. citizen children who are minors (i.e., under 18 years of age), and another 6% (0.7 million) are living with U.S. citizen children who are 18 years of age or older. Just over half (52%) of the unauthorized aliens are not living with U.S. citizen children. An estimated 775,000 unauthorized aliens are children under the age of 18 years.17

As Figure 2 illustrates, the number of citizen children (i.e., under 18 years of age) in households headed by an unauthorized alien has grown from 2.7 million in 2003 to 4.5 million in 2010. The number of unauthorized children, however, has declined from 1.5 million in 2003 to 1.0 million in 2010.18

Benefit Eligibility Rules

As mentioned before, most persons lacking legal authority to reside in the United States are not eligible for federally provided assistance. However, it is not unexpected that many persons residing illegally would be on the margins socioeconomically and thus, would pose particular dilemmas for service providers. The policies discussed below reflect a balancing of the integrity of entitlement programs with humanitarian provision of emergency services and assistance.

Pre-1996 Policies

In 1996, Congress enacted the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA, P.L. 104-193), which, among other things, created a general set of rules for noncitizen eligibility for public benefits. For some federal public benefits the eligibility rules were similar to those that were already in existence.

Program Rules

With the single exception of emergency Medicaid, unauthorized (illegally present) aliens were barred prior to 1996 from participation in all the major federal assistance programs that had statutory provisions for noncitizens, as were aliens here legally in a temporary status (i.e., nonimmigrants such as persons admitted for tourism, education, or employment).19 Since 1986, for example, a Medicaid recipient was required to declare under penalty of perjury whether he or she is a citizen or national of the United States or—if not a citizen or national—that he or she is an alien in a "satisfactory immigration status."20

However, many health, education, nutrition, income support, and social service programs did not include specific provisions regarding alien eligibility, and unauthorized aliens were potential participants.21 These programs included, for example, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (the WIC program); child nutrition programs; initiatives funded through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act; the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); community and migrant health centers; and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) program.

PRUCOL

PRUCOL, an acronym for "permanently residing under color of law," is an eligibility standard that is not defined in statute; historically, it has been used to provide a benefit to certain foreign nationals who the government knows are present in the United States, but whom it has no plans to deport or remove. Considered by many to be an obsolete construct, PRUCOL recently began re-emerging in the context of "quasi-legal" aliens.

Prior to 1996, eligibility for federal benefits depended on how the PRUCOL standards were interpreted. Many service providers had construed PRUCOL narrowly to include only those aliens here under certain specific statutory authorizations during the 1970s. A federal court, however, disagreed with these narrow interpretations. In Holley v. Lavine, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that "[w]hen ... a legislative body uses the term 'under color of law' it deliberately sanctions the inclusion of cases that are, in strict terms, outside the law but are near the border."22 At that time, the court concluded that the PRUCOL standard for Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, the precursor to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), for example, could cover aliens known by the government to be undocumented or deportable, but whom the government nevertheless allowed to remain here indefinitely. The court decisions, however, did not offer a uniform definition of PRUCOL, resulting in differing applications according to the benefit and the class of alien.

Current Federal Law

Enacted more than 20 years ago, Title IV of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996 (P.L. 104-193) established comprehensive restrictions on the eligibility of all noncitizens for federal public benefits, with limited exceptions including LPRs with a substantial U.S. work history or military connection. Regarding unauthorized aliens, Section 401 of PRWORA sought to end the PRUCOL eligibility standard by barring them from any federal public benefit except the emergency services and programs expressly listed in Section 401(b) of PRWORA.

This overarching bar to unauthorized aliens hinges on how broadly the phrase "federal public benefit" is implemented. The law defines a federal public benefit as

(A) any grant, contract, loan, professional license, or commercial license provided by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States; and (B) any retirement, welfare, health, disability, public or assisted housing, postsecondary education, food assistance, unemployment benefit, or any other similar benefit for which payments or assistance are provided to an individual, household, or family eligibility unit by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States.23

So defined, this bar covers many programs whose enabling statutes do not individually make citizenship or immigration status a criterion for participation. Thus, unauthorized aliens are statutorily barred from receiving benefits that previously were not individually restricted—Social Services Block Grants and migrant health center services, for example—unless they fall within the 1996 welfare act's limited exceptions. These statutory exceptions include the following:

- treatment under Medicaid for emergency medical conditions (other than those related to an organ transplant);24

- short-term, in-kind emergency disaster relief;25

- immunizations against immunizable diseases and testing for and treatment of symptoms of communicable diseases;

- services or assistance (such as soup kitchens, crisis counseling and intervention, and short-term shelters) designated by the Attorney General as (1) delivering in-kind services at the community level, (2) providing assistance without individual determinations of each recipient's needs, and (3) being necessary for the protection of life and safety; and

- to the extent that an alien was receiving assistance on the date of enactment, programs administered by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, programs under title V of the Housing Act of 1949, and assistance under Section 306C of the Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act.26

Beyond the statutory exceptions noted above, PRWORA also includes special rules governing the EITC. These provisions are aimed at preventing unauthorized aliens from receiving an EITC by requiring that Social Security Numbers (SSNs) for recipients (and spouses) be valid for employment in the United States.27

PRWORA separately has language on certain federally supported nutrition programs that directly bears on unauthorized aliens.28 More precisely, Title VII includes provisions that (1) stipulate that students eligible to receive free public education may receive federally subsidized school meals (e.g., free school lunches/breakfasts) without regard to their citizenship status29 and (2) leave to state discretion whether the state will deny benefits to unauthorized aliens under the WIC program, the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), the Summer Food Service program, the Special Milk program, the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP), the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR).30

PRWORA also mandated that unauthorized alien women be ineligible for prenatal care under Medicaid. Congress also enacted a provision that automatically provides Medicaid coverage at birth to children born of Medicaid-eligible mothers, but imposes a waiting period on covering children born of mothers who are not Medicaid-eligible.31 When the question of whether citizen children of unauthorized alien mothers were Medicaid-eligible at birth arose, a court dismissed the argument that children of all Medicaid-ineligible mothers rather than alienage was the relevant classification. In Lewis v. Thompson, the court found that citizen children of unauthorized alien mothers must be accorded automatic eligibility on terms as favorable as those available to the children of citizen mothers.32

Enacted in 1997, the year after PRWORA, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP),33 is considered a federal public benefit (barring unauthorized aliens). However, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) promulgated regulations in 2002 permitting states to provide CHIP coverage to fetuses.34 States reportedly are using this option of CHIP coverage for fetuses to provide prenatal care services to pregnant women who are unauthorized aliens.35

Higher Education Benefits

The Higher Education Amendments (HEA) of 1986 (P.L. 99-498) codified regulations that limited the eligibility for many federal student aid programs to U.S. citizens and LPRs. The U.S. Department of Education has kept in place the bar on unauthorized aliens and temporary foreign residents, including international students. Notably, since enactment of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), the Department of Education has verified the immigration status of applicants for federal financial aid through the Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) system (discussed in "Immigrant Verification").36

State Benefits

Unlike earlier federal law, PRWORA expressly bars unauthorized aliens from most state and locally funded benefits. The restrictions on these benefits parallel the restrictions on federal benefits. Unauthorized aliens are generally barred from state and local government contracts, licenses, grants, loans, and assistance.37 The following exceptions are made:

- treatment for emergency conditions (other than those related to an organ transplant);

- short-term, in-kind emergency disaster relief;

- immunization against immunizable diseases and testing for and treatment of symptoms of communicable diseases; and

- services or assistance (such as soup kitchens, crisis counseling and intervention, and short-term shelters) designated by the attorney general as (1) delivering in-kind services at the community level, (2) providing assistance without individual determinations of each recipient's needs, and (3) being necessary for the protection of life and safety.

Also, the restrictions on state and local benefits do not apply to activities that are funded in part by federal funds; these activities are regulated under PRWORA as federal benefits. Furthermore, the law states that nothing in it is to be construed as addressing eligibility for basic public education. Finally, the 1996 law allows the states, through enactment of new state laws, to provide unauthorized aliens with state and local benefits that otherwise are restricted.

Despite the federally imposed bar and the state flexibility provided by PRWORA, states still may expend a significant amount of state funds for unauthorized aliens. Public elementary and secondary education coupled with school lunches for unauthorized aliens remain compelled by judicial decision,38 and payment for emergency medical services for unauthorized aliens remains compelled by federal law. Meanwhile, certain other costs attributable to unauthorized aliens, such as criminal justice costs, remain compelled by the continued presence of unauthorized aliens.39

Determining Status and Eligibility

Although the bars on unauthorized aliens obtaining federal benefits are emphatic, determining a person's immigration and citizenship status is not always easy. The laws governing the eligibility of LPRs for means-tested federal assistance are based on a complex set of factors (e.g., work history, category of admission, and petitioning sponsorship), and states have options to provide benefits to LPRs that they may not opt to provide to unauthorized aliens.40

Immigrant Verification

The Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) system provides federal, state, and local government agencies access to data on immigration status that are necessary to determine noncitizen eligibility for public benefits. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) does not determine benefit eligibility; rather, SAVE enables the specific program administrators to ensure that only those noncitizens who meet their program's eligibility rules actually receive public benefits. According to USCIS, SAVE draws on the Verification Information System (VIS) database, which is a nationally accessible database of selected immigration status information that contains over 100 million records.41

SAVE's statutory authority dates back to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA).42 The IRCA, as amended, mandates the following programs and agencies to participate in the verification of an applicant's immigration status: the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Program, the Medicaid Program, and certain Territorial Assistance Programs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services); the Unemployment Compensation Program (U.S. Department of Labor); Title IV Educational Assistance Programs (U.S. Department of Education); and certain Housing Assistance Programs (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development).43 Subsequently, PRWORA required the Attorney General to establish procedures for a person applying for a federal public benefit to provide citizenship information in a fair, nondiscriminatory manner.44

According to USCIS, state and local agencies may access SAVE through two methods to verify an applicant's status: an electronic verification process through the online SAVE system; or, a paper-based verification process through the Form G-845, Document Verification Request. USCIS charges the benefit-granting agencies fees to use SAVE through web-based access according to the number and type of transactions. Agencies must have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and a purchase order with the SAVE program contractor to pay the transaction fees for web-based Internet access. Those agencies submitting paper forms (G-845s) are charged $2.00 per case by USCIS.45

In addition to establishing the SAVE system, there has been a consensus for well over a decade that immigration documents issued to aliens should include biometric identifiers. In designing these documents, the priorities have centered on document integrity as well as personal identification. The official document issued to LPRs is the permanent resident card, commonly called a "green card" because it had been printed on green stock. Now it is a plastic card that is similar in size to a credit card. Since April 1998, the card has incorporated security features, including digital images, holograms, micro-printing, and an optical memory stripe.46 The USCIS also issues an employment authorization document that has incorporated security features, including digital images, holograms, and micro-printing, since 1998.47

Given that approximately 11.1 million foreign nationals were estimated to be residing in the United States without legal authorization in 2014, it is reasonable to presume that some of these unauthorized aliens are committing document fraud. However, the extent to which unauthorized aliens enter with fraudulently obtained documents or acquire bogus documents after entry is not known.48

Citizenship Verification

As discussed above, the technology to verify legal immigration status has advanced considerably over the years. The United States, however, does not require its citizens to have legal documents that verify their citizenship and identity (i.e., national identification cards). Although some assert that the United States has de facto identification cards in the form of Social Security cards and driver's licenses or state identification cards, none of these documents establishes citizenship. The U.S. passport is one of the few documents that certify the individual is a U.S. citizen; indeed, for most U.S. citizens, it is the only document they possess that verifies both their citizenship and identity. Until recently, self-attestation of citizenship was generally accepted for most government purposes.

False claims of citizenship have long been an illicit avenue for benefit fraud and, as a result, are considered a crime. In general, Section 1015 of the United States Criminal Code (Title 18) criminalizes acts of fraud relating to naturalization, citizenship, or alien registry. Specifically, it is a criminal offense for a person to "knowingly ... make any false statement or claim that he is, or at any time has been, a citizen or national of the United States, with the intent to obtain, for himself or another, any federal or state benefit or service, or to engage unlawfully in employment in the United States."49 The INA also makes "misrepresentation" (e.g., falsely claiming U.S. citizenship) a ground for inadmissibility.50

Congress enacted in recent years several specific laws aimed directly at these perceived loopholes of citizenship self-attestation and identity document integrity. In terms of document integrity, for example, the REAL ID Act (P.L. 109-13, Division B) contained provisions to enhance the security of state-issued drivers' licenses and personal identification (ID) cards. If state-issued drivers' licenses and ID cards are to be accepted for federal purposes, the act requires states to establish minimum issuance standards and adopt certain procedures to verify documents used to obtain drivers' licenses and ID cards.51

In terms of obtaining Medicaid, Section 6036 of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-171), as amended by the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432), requires that states obtain satisfactory documentation of citizenship and identity to determine eligibility. This requirement is codified as Section 1903(x) of the Social Security Act (SSA). Section 211 of CHIPRA 2009 (enacted as P.L. 111-3) permits states to elect an alternative process for verifying citizenship for Medicaid, as required by Section 1903(x) of the SSA. Under the Section 211 option, the name and SSN of an applicant could be submitted to the Commissioner of SSA. The Commissioner would check the information received from the states against the SSA database and determine whether the name and SSN match and whether the SSA database shows that the applicant is a citizen. If the SSA cannot confirm the applicant's name, SSN, and citizenship, the applicant would have to either resolve the inconsistency or provide satisfactory documentary evidence of citizenship as defined in Section 1903(x)(3), or else be disenrolled. Section 211(c) of CHIPRA 2009 would provide that the Medicaid citizenship documentation requirements currently required under Section 1903(x), and as amended by the provisions of Section 211 of CHIPRA 2009, would apply to CHIP.52

The use of the Social Security card for personal identification has been controversial for many years. The Social Security Administration (SSA) has emphasized that the SSN identifies a particular record only and the Social Security card indicates the person whose record is identified by that number. Thus, the Social Security card was not meant to identify the bearer. The Social Security Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-603) required the SSA to obtain evidence to establish age, citizenship, or alien status, and identity of the applicant for a Social Security card/number. As of November 2008, the SSA requires applicants to present for identification a document that shows name, identifying information, and preferably a recent photograph.53 The SSA also requires that all documents be either originals or copies certified by the issuing agency.54

Receipt of Benefits

There is a widely held perception that many unauthorized migrants obtain federal benefits—despite the restrictions and verification procedures. Given that data on unauthorized aliens are estimates at best and that these aliens are expressly barred from most federal programs, reliable data on the extent that they actually receive benefits are not available. That said, there are a few program evaluations and investigations, as well as demographic projections, that attempt to address this thorny issue.55

The Inspector General for Tax Administration at the U.S. Department of the Treasury found that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) paid $4.2 billion in refundable tax credits in 2010 to individuals who were not authorized to work in the United States. This audit was based upon analysis of tax returns filed by persons with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs). The IRS issues ITINs to individuals who are required to have a taxpayer identification number for tax purposes but are not eligible to obtain an SSN because they are not authorized to work in the United States.56 Both resident and nonresident aliens have income reporting requirements under the Internal Revenue Code, and even income illegally obtained is subject to taxation. The number of tax forms filed with ITINs has increased from 1.55 million in 2005 to 3.02 million in 2010.57 It is unclear how many of these individuals who filed with ITINs were part of mixed-status families.58

A dated (2004) U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) study had estimated that $38.0 million in Unemployment Compensation (UC) was paid to unauthorized aliens in FY2002.59 In total, the UC program expended $53.8 billion that same year.60 In determining eligibility for UC, the state agency requires that any individual applying for UC, under penalty of perjury, declare in writing whether or not he or she is a citizen or a national of the United States. If the individual is not a citizen or a national, the individual must present documentation from the USCIS containing the individual's alien admission number or alien file number or such other documents as the state determines constitute reasonable evidence indicating a satisfactory immigration status. Immigration status is supposed to be verified through the SAVE Program.61 The DOL concluded, "[T]he largest reason for making the error ... involved the state's failure to use information it had in hand to determine that this information definitely pointed to an eligibility issue."62 This DOL study did not provide sufficient detail to determine the extent that these unauthorized alien beneficiaries were "quasi-legal" migrants who had EADs and SSNs.

Analysis of the latest data from DOL's Benefit Accuracy Measurement (BAM) Survey revealed that payments to ineligible aliens made up 0.02% of all UC payments from July 2013 through June 2016.63 These UC payments to ineligible aliens comprised 0.17% of all UC overpayments during this three-year period.64

Mixed-immigration status families are another factor that confounds research on benefit receipt. A report on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) estimated that 4.1 million U.S. citizen children who were living with noncitizen parents received food stamps in FY2014, or 9.0% of all participants.65 Although many of these noncitizen parents are likely to be LPRs, some parents may be unauthorized migrants. Similarly, FY2015 data on characteristics of TANF recipients indicate that 25.4% of the "child-only" cases are U.S. citizen children of foreign born parents who do not meet the definition of "qualified alien."66

Steven Camarota, director of research at the Center for Immigration Studies, used the March CPS and the decennial census as the basis for his widely cited estimations on federal benefits that may have gone to households headed by unauthorized migrants in 2002.67 Camarota estimated that the largest costs were Medicaid ($2.5 billion), treatment for the uninsured ($2.2 billion), and food assistance programs ($1.9 billion). Camarota's cost calculations additionally included programs that unauthorized aliens are eligible for, such as emergency Medicaid and school lunch. He concluded, "[M]any of the costs associated with illegals are due to their American-born children, who are awarded U.S. citizenship at birth ... greater efforts at barring illegals from federal programs will not reduce costs because their citizen children can continue to access them."68

Selected Issues

Although the law appears straightforward, the policy on unauthorized aliens' access to federal benefits is peppered with ongoing controversies and debates. Some center on demographics issues, such as how to treat mixed-immigration-status families. Others explore unintended consequences, most notably when tightening up the identification requirements results in denying benefits to U.S. citizens. Still others are debates about how broadly the clause "federal public benefit" should be implemented. The concluding section of this report offers an illustrative sampling of these issues.

Treatment of Mixed-Status Families

Whether an unauthorized alien who is head of household is permitted to be the payee of a federal benefit for U.S. citizen children varies across programs. Most federal statutes are silent on the matter because the benefit is given to the eligible individual.69 In the case of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called food stamps), the "assistance unit" is a household, typically those living together who also purchase and prepare food together. SNAP eligibility and benefits depend on the number of eligible household members and household financial resources.70 When determining a household's eligibility status and benefit level, unauthorized aliens living with eligible members are not counted as household members; but their income, typically less their pro-rata share, is counted (deemed to the rest of the household).71 SNAP rules allow an unauthorized alien household member to apply for and obtain benefits on behalf of eligible members, and eligibility/benefit determinations are carried out as described above.72

The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, while not expressly barring them, sets a barrier for unauthorized alien parents to be the payees of SSI benefits for their U.S. citizen children. More precisely, the Social Security Act requires an investigation into a potential representative payee to determine his or her suitability and as part of this investigation: "verify the social security account number (or employer identification number) of such person."73 This provision is somewhat analogous to the requirement that taxpayers claiming the EITC provide their SSN and the SSN of any qualifying child.74

Expansion of Documentary Requirements

Foreign nationals who are LPRs, as discussed more fully above, have biometric identification documents, and their eligibility for federal benefits may be confirmed through the SAVE system.75 Congress has already enacted strong incentives for states to issue enhanced drivers licenses (EDLs) that indicate country of citizenship. Requiring that the Social Security Administration issue SSNs that may be used to verify immigration status and citizenship is another option. Proponents of expanding the documentary requirements to include proof of U.S. citizenship assert that it is the most effective way to stop ineligible aliens from making false claims of U.S. citizenship. A secondary argument is one of equal treatment; that is, it levels the playing field by holding U.S. citizens to the same documentary requirements as foreign nationals.

Medicaid provides an excellent example because, as noted earlier, a citizenship documentation requirement was added in 2006 to supersede the self-declaration of citizenship status.76 Medicaid now requires that a state obtain satisfactory documentation of citizenship and identity to determine eligibility.77 When the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) evaluated the new requirement in 2007, it found only limited information about the extent to which the requirement deterred aliens who were not qualified from applying for Medicaid. These findings were consistent with the 2005 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General report on state self-attestation policies, which did not find problems regarding false allegations of citizenship.78 Rather, the GAO found evidence of inadvertent denials of persons who appeared to be U.S. citizens. "Twenty-two of the 44 states reported declines in Medicaid enrollment due to the requirement, and a majority of these states attributed the declines to delays in or losses of Medicaid coverage for individuals who appeared to be eligible citizens."79

Also at issue is whether expanded documentary requirements are cost effective. The HHS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had estimated the citizenship documentation requirement would result in savings for the federal government and states of $90 million for FY2008. When GAO investigated this cost savings, it concluded that the potential fiscal benefits for the federal government and states were uncertain. "Specifically, CMS did not account for the increased administrative expenditures reported by states, and the agency's estimated savings from ineligible, noncitizens no longer receiving benefits may be less than anticipated."80

Scope of "Federal Public Benefits" Clause for Tax Refunds

The language of Section 401 of PRWORA appears to be quite broad (see the "Current Federal Law" section, above), yet its implementation across federal public benefits is not uniform. An example of this ambiguity centers on tax refunds. As noted earlier, the Internal Revenue Code generally does not distinguish between resident aliens who are lawfully present in the United States and those who are not (with the exception of the EITC). It appears that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) permits unauthorized resident aliens to claim the additional child tax credit.81 There is no indication, moreover, that the IRS generally considers refundable tax credits to be federal public benefits that unauthorized migrants are barred from receiving.82

It is possible that refundable tax credits could fall within the types of benefits described by Section 401.83 Under this interpretation, the refundable nature of a credit makes it equivalent to a "grant" or "payment or assistance" provided by a federal agency or appropriated funds. Refundable tax credits, as some elaborate, are being "provided to an individual, family, or eligibility unit" and thus could be classified as a federal public benefit under Section 401 of PRWORA.84

Competing Priorities for Emergency Relief

Government officials sometimes face competing priorities when dealing with unauthorized aliens, and such dilemmas are especially evident during major disasters. When a major disaster occurs, two competing priorities come into play: access to emergency disaster relief and immigration enforcement. According to Section 401 of PRWORA, unauthorized aliens are eligible for short-term, in-kind emergency disaster relief and services or assistance that deliver in-kind services at the community level, provide assistance without individual determinations of each recipient's needs, and are necessary for the protection of life and safety.85 The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act,86 the authority under which the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) conducts disaster assistance efforts, requires nondiscrimination and equitable treatment in disaster assistance.87 FEMA assistance provided under the Stafford Act includes (but is not limited to) grants for immediate temporary shelter, cash grants for uninsured emergency personal needs, temporary housing assistance, home repair grants, unemployment assistance due to the disaster, emergency food supplies, legal aid for low-income individuals, and crisis counseling.88

When a situation threatens human health and safety, and a disaster is imminent but not yet declared, the Secretary of DHS may pre-position employees and supplies and provide precautionary evacuation measures.89 As part of a mock evacuation in May 2008 in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, DHS Border Patrol officials in that region announced that border patrol agents would pre-screen residents for citizenship documents before allowing them to board evacuation buses in the event of a hurricane. DHS Border Patrol spokesperson Dan Doty stated that the border patrol will assist other federal, state, and local authorities in a safe evacuation but at the same time uphold its job of "border security, protecting the border, and establishing alienage."90 DHS has reportedly acknowledged the importance of keeping families together during an evacuation; however, officials have not indicated how mixed-immigration status families would be treated, or what would happen (when asked) if everyone in the family except an elderly grandparent had proper documents.91 Notwithstanding the media reports, DHS Headquarters officials indicate that the department has not issued a formal policy on pre-screening during emergency evacuations.92

When the disaster relief moves from emergency assistance for the protection of life and safety to disaster aid based on determinations of each recipient's needs (e.g., funds to help repair a damaged home), the "federal public benefits" question arises. FEMA requires additional information from applicants at this point in the application process. That information may include proof of a rental agreement or property ownership, employment status, and other factors that may further identify an applicant's citizenship status as part of the eligibility determination.93

Regardless of their programmatic eligibility, when unauthorized aliens are receiving federal disaster aid, according to DHS officials, they have no immunity from deportation. In the aftermath of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, there were reportedly many displaced aliens who feared that seeking government help might lead to their deportation.94 "The administration's priority is to provide needed assistance: water, food, medical care, shelter," DHS spokesperson Joanna Gonzalez explained at the time. "However, as we move forward with the response, we can't turn a blind eye to the law."95 DHS arrested, detained, and ordered deported an unspecified number of unauthorized aliens displaced by the 2005 hurricanes.96

In addition to the disaster-related emergency assistance, FEMA also funds the Emergency Food and Shelter National Board (EFS) Program, which provides funding to service providers assisting homeless individuals and families.97 When there was an influx of unaccompanied alien children and families from Central America in the spring and summer of 2014,98 the EFS program was one of the few potential sources of supplemental funding for the homeless service providers that provided them shelter.

Re-emergence of PRUCOL with "Quasi-legal" Migrants

As awareness of and confusion over "quasi-legal" migrants grows, the policies embodied by PRUCOL have returned to the fore.99 This issue most frequently arises in the context of compensation or training for laid-off workers or in debates over tax refunds or rebates. Those aliens who have EADs and SSNs—but who are not otherwise authorized to reside in the United States—pose a particular dilemma to some because they are permitted to work and have likely paid into the system that finances the particular benefit.100 They also are difficult to distinguish from LPRs because they possess valid government-issued documents.

A similar issue is whether states may provide in-state tuition to foreign nationals who have Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a subset of "quasi-legal" migrants. Some have asserted the bar on benefit receipt does not apply to foreign nationals with TPS because Section 244 of INA considers them lawfully present. However, others point out that Section 244(f)(4) limits that "lawfully present" designation to nonimmigrant adjustments or changes in immigration status. Aliens with TPS are not defined as qualified aliens under PRWORA. Given the bar on federally funded postsecondary education in Section 401 of PRWORA, the question of states providing in-state tuition to foreign nationals with TPS may ultimately hinge on whether federal funds are involved.101

Refinement or Revisions of the Rules

Congress has grappled on numerous occasions with the question of whether to refine or revise the access rules for unauthorized aliens. These issues are sometimes centered in intricate and, some would say, secondary concerns (e.g., the citizenship documentation requirements in the CHIP reauthorization legislation in the 111th Congress).102 Other times, the issue becomes embroiled in major "hot-button" controversy, such as the motion to re-commit H.R. 3161 in the 110th Congress with instructions to amend it to bar use of funds to employ or provide housing for unauthorized aliens.103

Some argue that—if unauthorized aliens can end-run the system—federal benefit programs are a magnet for unauthorized migration. Others argue that—in the absence of congressional action on comprehensive immigration reform—the dilemma of unauthorized aliens, mixed-immigration status families, and "quasi-legal" migrants fosters a growing underclass of noncitizens who lack access to services. Whether additional restrictions and expenditures to further bar access to benefits, as well as fraudulent receipt of benefits, are cost-effective options in terms of the value of the benefits provided is yet another argument for Congress to weigh.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Ruth Ellen Wasem and Alison Siskin, former CRS Specialists in Immigration Policy, were previous authors of this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRS Report R42988, U.S. Immigration Policy: Chart Book of Key Trends. |

| 2. |

Ibid. |

| 3. |

For legal analyses of these issues at the state and local levels, see CRS Report RL34345, State and Local Restrictions on Employing, Renting Property to, or Providing Services for Unauthorized Aliens: Legal Issues and Recent Judicial Developments. |

| 4. |

For policy on legal permanent residents' eligibility, see CRS Report RL33809, Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview and Trends. For a discussion of noncitizen eligibility for Social Security and the Affordable Care Act, which are not considered federal public benefits, see CRS Report RL32004, Social Security Benefits for Noncitizens. |

| 5. |

Jeffrey S. Passel and D'Vera Cohn, "Unauthorized immigrant population stable for half a decade," Pew Research Center (Pew), July 22, 2015. |

| 6. |

For a discussion of the estimates and the issues, see CRS Report RL33874, Unauthorized Aliens Residing in the United States: Estimates Since 1986. |

| 7. |

For further background, CRS Report RL32004, Social Security Benefits for Noncitizens. |

| 8. |

For further background, see CRS Report RS20844, Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues. |

| 9. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Secretary Napolitano Announces Deferred Action Process for Young People Who Are Low Enforcement Priorities," http://www.dhs.gov/files/enforcement/deferred-action-process-for-young-people-who-are-low-enforcement-priorities.shtm; and CRS Report RL33863, Unauthorized Alien Students: Issues and "DREAM Act" Legislation. |

| 10. |

For further background, see CRS Report R41753, Asylum and "Credible Fear" Issues in U.S. Immigration Policy. |

| 11. |

For further background, CRS Report R42866, Permanent Legal Immigration to the United States: Policy Overview. |

| 12. |

The extent that some nonimmigrants (e.g., temporary workers, tourists, or foreign students) overstay their temporary visas and become "quasi-legal" aliens with petitions pending to adjust to legal status is discussed in CRS Report RS22446, Nonimmigrant Overstays: Brief Synthesis of the Issue. |

| 13. |

For further background, see CRS Report RL32621, U.S. Immigration Policy on Asylum Seekers. |

| 14. |

For a full analysis of this issue, see Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman, 2007 Annual Report to Congress, June 11, 2007. |

| 15. |

CRS Report R43703, Special Immigrant Juveniles: In Brief. |

| 16. |

8 U.S.C. §1401(a). For a complete legal analysis of jus soli, see CRS Report RL33079, Birthright Citizenship Under the 14th Amendment of Persons Born in the United States to Alien Parents (available to congressional clients upon request). |

| 17. |

Jeffrey Passel, D'Vera Cohn, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, Population Decline of Unauthorized Immigrants Stalls, May Have Reversed, Pew Research Center, Washington, DC, September 23, 2013, http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2013/09/Unauthorized-Sept-2013-FINAL.pdf. |

| 18. |

Jeffrey S. Passel and D'Vera Cohn, Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010, Pew Hispanic Center, February 1, 2011; and Paul Taylor, Mark Hugo Lopez, and Jeffrey S. Passel, Unauthorized Immigrants: Length of Residency, Patterns of Parenthood, Pew Hispanic Center, December 1, 2011. |

| 19. |

Emergency Medicaid is solely for noncitizens and came into being as a result of provisions in subtitle E of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-509), which restricted Medicaid eligibility to LPRs and noncitizens permanently residing under color of law, and required Medicare-participating hospitals to provide emergency medical services for all patients (including noncitizens) who seek care, regardless of their ability to pay. |

| 20. |

§1137(d) of the Social Security Act, as amended by the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 (P.L. 99-603). |

| 21. |

A number of states reportedly had enacted laws denying various types of public assistance to all aliens or to legal aliens who had not resided in the United States for a fixed number of years. However, in 1971 the Supreme Court declared these state-imposed restrictions unconstitutional in Graham v. Richardson (403 U.S. 365 (1971), both because they violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and because they encroached upon the exclusive federal power to regulate immigration. See also Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982). |

| 22. |

553 F.2d 845 (2d Cir. 1977). |

| 23. |

§401(c) of PRWORA, 8 U.S.C. 1611. |

| 24. |

For further analysis of this issue, see CRS Report RL31630, Federal Funding for Unauthorized Aliens' Emergency Medical Expenses. |

| 25. |

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. §5121 et. seq.) authorizes the President to make the initial determination of eligibility for federal relief and recovery assistance through the issuance of either a major disaster or emergency declaration. Under §403 of the Stafford Act, FEMA may provide assistance essential to save lives and property (42 U.S.C. 5170b). |

| 26. |

Subtitle E of Title V of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (Division C of P.L. 104-208) later facilitated the removal of unauthorized aliens from housing assistance. For analysis, see CRS Report RL31753, Immigration: Noncitizen Eligibility for Needs-Based Housing Programs. |

| 27. |

The Internal Revenue Code does not have a special classification for individuals who are in the United States without authorization. Instead, the Code treats these individuals in the same manner as other foreign nationals—they are subject to federal taxes and classified for tax purposes as either resident or nonresident aliens. An unauthorized individual who has been in the United States long enough to qualify under the "substantial presence" test is classified for tax purposes as a resident alien. For a fuller explanation, see CRS Report RS21732, Federal Taxation of Aliens Working in the United States. |

| 28. |

As opposed to the rules noted here, the law governing the Food Stamp program bars unauthorized aliens from participation. |

| 29. |

The PWORA itself does not address a states' obligation to grant all aliens equal access to education under the Supreme Court's decision in Plyer v. Doe (47 U.S. 202 [1982]). |

| 30. |

No state has, as yet, taken the option to deny benefits under these programs. |

| 31. |

42 U.S.C. §1396a(e)(4) and 42 C.F.R. §§435.117, 435.301(b)(1)(iii). |

| 32. |

Lewis v. Thompson, 252 F.3d 567, 588 (2d. Cir. 2001). |

| 33. |

Title XXI of the Social Security Act. CHIP was enacted in 1997, the year after PRWORA. |

| 34. |

Federal Register, vol. 67, pp. 61955-61974, October 2, 2002. |

| 35. |

8 U.S.C §1611. For further discussion, see CRS Report R40144, State Medicaid and CHIP Coverage of Noncitizens, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 36. |

CRS Report R43302, Postsecondary Education Issues in the 113th Congress. |

| 37. |

For a comprehensive legal analyses of these issues at the state and local levels, see CRS Report RL34345, State and Local Restrictions on Employing, Renting Property to, or Providing Services for Unauthorized Aliens: Legal Issues and Recent Judicial Developments. |

| 38. |

457 U.S. 202 (1982). |

| 39. |

CRS Report R42053, Fiscal Impacts of the Foreign-Born Population. |

| 40. |

For further analyses of these issues, see CRS Report RL33809, Noncitizen Eligibility for Federal Public Assistance: Policy Overview and Trends. |

| 41. |

The VIS database is also used for the E-Verify system that employers may use to check whether an alien is authorized to work in the United States. CRS Report R40446, Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification. |

| 42. | |

| 43. |

In 1996, however, Congress also gave the states the option of not using SAVE for determining noncitizen eligibility for food stamps, now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). More specifically, §840 of PRWORA added §11(p) to the Food Stamp Act of 1977, which stated that state agencies were not required to use the income and eligibility or an immigration status verification system that had been established by IRCA. Notably, the provision did not waive the requirements for the state agencies to make immigration status eligibility determinations. |

| 44. |

P.L. 104-193, §432. |

| 45. |

For further information, see the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services SAVE home page at https://www.uscis.gov/save. |

| 46. |

For further analysis, see CRS Report RL34007, Immigration Fraud: Policies, Investigations, and Issues. |

| 47. |

For more complete analyses of alien employment laws, policies, and issues, see CRS Report RL33973, Unauthorized Employment in the United States: Issues, Options, and Legislation; and CRS Report RS22180, Unauthorized Employment of Aliens: Basics of Employer Sanctions. |

| 48. |

For further analysis, see CRS Report RL34007, Immigration Fraud: Policies, Investigations, and Issues. |

| 49. |

18 U.S.C. §1015. For a complete legal analysis, see CRS Report RL32657, Immigration-Related Document Fraud: Overview of Civil, Criminal, and Immigration Consequences, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 50. |

§212(c) of INA. |

| 51. |

The act specifies the minimum requirements to be established. These requirements include two biometric features: a digital photograph and a signature. For further discussion, see CRS Report RL34430, The REAL ID Act of 2005: Legal, Regulatory, and Implementation Issues. |

| 52. |

For further discussion, see CRS Report RS22629, Medicaid Citizenship Documentation. |

| 53. |

Implementing §7213 of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, P.L. 108-458. |

| 54. |

Social Security Administration, New Rules for Getting a Social Security Number and Card, SSA Publication No. 05-10120, November 2008. |

| 55. |

For a more complete synthesis of the research on the costs of unauthorized aliens, see CRS Report R42053, Fiscal Impacts of the Foreign-Born Population. |

| 56. |

For example, foreign nationals who live abroad may be subject to federal income tax if they have U.S. source income. For a discussion of foreign nationals and taxes, see CRS Report R43840, Federal Income Taxes and Noncitizens: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 57. |

Michael E. McKenney, Kyle R. Andersen, and Larry Madsen, et al., Individuals Who Are Not Authorized to Work in the United States Were Paid $4.2 Billion in Refundable Credits, Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, 2011-41-061, Washington, DC, July 7, 2011, http://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2011reports/201141061fr.html#background. |

| 58. |

For further analysis, see CRS Report R42628, Ability of Unauthorized Aliens to Claim Refundable Tax Credits. |

| 59. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, An Analysis of Overpayments Not Included In the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Measure for "Prevention of Overpayments." |

| 60. |

For more on the Unemployment Compensation Program, see CRS Report RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits. |

| 61. |

§1137(d) and (e) of the Social Security Act (SSA). |

| 62. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, An Analysis of Overpayments Not Included In the Unemployment Insurance (UI) Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Measure for "Prevention of Overpayments," report available at http://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/integrity/gpra_overpayments.asp, last accessed May 5, 2008. |

| 63. |

The BAM survey includes the State UI, Unemployment Compensation for Federal Employees (UCFE), and Unemployment Compensation for Ex-Service Members (UCX) programs only and does not include payments for Extended Benefits or Emergency Unemployment Compensation. |

| 64. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Unemployment Insurance, BAM Overpayment Rates by Cause, unpublished tabulations from the Benefit Accuracy Management System, October 24, 2016. |

| 65. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support, Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2014, SNAP-15-CHAR, by Kelsey Farson Gray and Shivani Kochhar. Project Officer, Jenny Genser. Alexandria, VA: 2015. |

| 66. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients, Fiscal Year 2015, Table 8, August 18, 2016. |

| 67. |

For a complete discussion of Camarota's methodology on the costs of unauthorized aliens, see CRS Report R42053, Fiscal Impacts of the Foreign-Born Population. |

| 68. |

Steven A. Camarota, The High Cost of Cheap Labor: Illegal Immigration and the Federal Budget (Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies, August 2004). |

| 69. |

If the presence of ineligible aliens (e.g., unauthorized aliens or LPRs during the first five years) in a family is made known, state policies likely do not exclude their income or financial resources from the household when determining whether the family falls within the poverty thresholds for Medicaid or TANF. California's TANF program, for example, includes the income and needs of ineligible aliens who are part of the household in making the eligibility determination but does not compute such individuals into the grant amount. |

| 70. |

For background on SNAP, see CRS Report R42505, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A Primer on Eligibility and Benefits. |

| 71. |

Section 6(f) of the Food and Nutrition Act; 7 U.S.C. 2015(f). In addition, §6(f) provides that, when judging a household's eligibility, the total amount of an ineligible unauthorized alien household member's liquid assets are to be counted. |

| 72. |

§11(e) of the Food and Nutrition Act; 7 U.S.C. 2020(e). |

| 73. |

§1631(a)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Social Security Act. Presumably, an alternate payee would be designated to receive the money on the child's behalf if the payee's SSN was not valid. |

| 74. |

§451 of PRWORA. 8 U.S.C. 1161. |

| 75. |

As discussed above, the SAVE system provides federal, state, and local government agencies access to data on immigration status that are necessary to determine noncitizen eligibility for public benefits. |

| 76. |

§6036 of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-171), as amended by the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432). |

| 77. |

For further discussion, see CRS Report RS22629, Medicaid Citizenship Documentation. |

| 78. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, Self-Declaration of U.S. Citizenship for Medicaid, July 2005. |

| 79. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, States Reported That Citizenship Documentation Requirement Resulted in Enrollment Declines for Eligible Citizens and Posed Administrative Burdens, GAO-07-889, June 2007. |

| 80. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, States Reported That Citizenship Documentation Requirement Resulted in Enrollment Declines for Eligible Citizens and Posed Administrative Burdens, GAO-07-889, June 2007. |

| 81. |

See Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, The Internal Revenue Service's Individual Taxpayer Identification Number Creates Significant Challenges for Tax Administration, Report No. 2004-30-023, at 3 (January 2004) (stating that "unauthorized resident aliens are eligible for the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC), which is one of only two major credits that can result in a Federal Government payment above the tax liability. In TY 2001, $160.5 million was given to approximately 203,000 unauthorized resident aliens, with about 190,000 of these filers having no tax liability and receiving $151 million"). |

| 82. |

CRS Report R42628, Ability of Unauthorized Aliens to Claim Refundable Tax Credits. |

| 83. |

Michael E. McKenney, Kyle R. Andersen, and Larry Madsen, et al., Individuals Who Are Not Authorized to Work in the United States Were Paid $4.2 Billion in Refundable Credits, Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, 2011-41-061, Washington, DC, July 7, 2011, http://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2011reports/201141061fr.html#background. |

| 84. |

CRS Report R42628, Ability of Unauthorized Aliens to Claim Refundable Tax Credits. |

| 85. |

For a more complete analysis, see CRS Congressional Distribution Memorandum, Noncitizen Eligibility for Disaster-Related Assistance. |

| 86. |

42 U.S.C. §5121 et. seq. |

| 87. |

42 U.S.C. §5151(a): The President shall issue, and may alter and amend, such regulations as may be necessary for the guidance of personnel carrying out Federal assistance functions at the site of a major disaster or emergency. Such regulations shall include provisions for insuring that the distribution of supplies, the processing of applications, and other relief and assistance activities shall be accomplished in an equitable and impartial manner, without discrimination on the grounds of race, color, religion, nationality, sex, age, disability, English proficiency, or economic status. |

| 88. |

For a full discussion of available assistance, see CRS Report RL33053, Federal Stafford Act Disaster Assistance: Presidential Declarations, Eligible Activities, and Funding, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 89. |

The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 (Title VI, P.L. 109-295) authorized the President to support precautionary evacuation measures, accelerate federal emergency response and recovery aid, and provide expedited federal assistance (coordinated with the state to the extent possible) in the absence of a specific request from state officials authorized to provide transportation assistance to those displaced from their residences, including that assistance needed to move among alternative temporary shelters or to return to their original residence; and provide case management services to state, local, or qualified private organizations that provide assistance to victims. (P.L. 109-295, §681, 120 Stat. 1444, which amended §§402 and 502 of the Stafford Act.) For more information on the expanded assistance, see CRS Report RL33729, Federal Emergency Management Policy Changes After Hurricane Katrina: A Summary of Statutory Provisions, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 90. |

Rio Grande Guardian, "Hurricane evacuees leaving the Valley by bus will be prescreened for citizenship," by Joey Gomez, May 14, 2008. Doty later responded to criticism that this policy would endanger people by stating: "In the event of a mandatory evacuation, any illegal alien that is taken into custody by the Border Patrol will be evacuated by the Border Patrol to a detention facility in a safe area of the state. People in custody will still be moved out of the immediate danger areas." Houston Chronicle, "Border Patrol plans to check IDs in hurricane evacuations," Associated Press, May 16, 2008, and Rio Grande Guardian, "Hinojosa, AILA, criticize Border Patrol involvement in Valley hurricane evacuation," by Steve Taylor, May 17, 2008. |

| 91. |

San Antonio Express-News, "U.S. Citizenship To Be Checked In Event Of A Storm," by Lynn Brezosky, May 16, 2008. |

| 92. |

CRS has been advised that this reported citizenship pre-screening is not an official DHS policy at this time. Meeting with DHS Customs and Border Protection officials, May 21, 2008. |

| 93. |

FEMA's policy states that if you are not a U.S. citizen or a qualified alien, another adult household member who is eligible may qualify and "no information regarding your status will be gathered." If a minor child who is a U.S. citizen or a qualified alien resides with you, you can apply for assistance on your child's behalf and "no information regarding your status will be gathered." |

| 94. |

CRS Report RL33091, Hurricane Katrina-Related Immigration Issues and Legislation. |

| 95. |

Darryl Fears, "For Illegal Immigrants, Some Aid Is Too Risky," Washington Post, September 20, 2005. |

| 96. |

Wall Street Journal, "Storms in the Gulf: Roundup of Immigrants in Shelter Reveals Rising Tensions," by Chad Terhune and Even Perez, October 3, 2005; Chicago Tribune, "Immigration Agents Net 5," by Tribune News Service, September 20, 2005; and El Paso Times," Evacuee Faces Deportation," by Louie Gilot, September 22, 2005. |

| 97. |

CRS Report R42766, The Emergency Food and Shelter National Board Program and Homeless Assistance. |

| 98. |

For background on unaccompanied children from Central America, see CRS Report R43599, Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview. |

| 99. |

PRUCOL specifically arose early in the 110th Congress when §226 of the House-passed Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) Act of 2007 (H.R. 3920) stated: "No benefit allowances, training, or other employment services may be provided under this chapter to a worker who is an alien unless the alien is an individual lawfully admitted for permanent residence to the United States, is lawfully present in the United States, or is permanently residing in the United States under color of law." This provision restated language in the existing TAA statute that had been superseded by Title VI of PRWORA. Although the Senate did not act on H.R. 3920 in the 110th Congress, P.L. 110-161 appropriated funding for TAA without the PRUCOL language. For background and legislative tracking on TAA, see CRS Report RL34383, Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) for Workers: Current Issues and Legislation, available to congressional clients upon request. |

| 100. |

The issue of "quasi-legal" also arises in the context of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Those aliens who are "lawfully present" are generally subject to the health insurance mandate and are eligible, if otherwise qualified, to participate in the exchanges (the health insurance marketplace) and for the premium tax credit and cost-sharing subsidies available to certain individuals who purchase insurance through an exchange. Most "quasi-legal" aliens are considered lawfully present for the purposes of the ACA. For further discussion, see CRS Report R43561, Treatment of Noncitizens Under the Affordable Care Act. |

| 101. |

For further analyses of these issues, see CRS Report RL33863, Unauthorized Alien Students: Issues and "DREAM Act" Legislation. |

| 102. |

CRS Report RS22629, Medicaid Citizenship Documentation. |

| 103. |

The House of Representatives established a special committee to investigate the August 2, 2007, roll call vote to recommit H.R. 3161, the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies FY2008 Appropriations Act. For background on this dispute, see CQ Today, "Preliminary Report on Disputed Vote Answers Few Questions," by Kathleen Hunter, September, 28, 2007, and CQ Today, "This Is One Ugly Dispute That May Soon Be Ready for Its Close-Up," by Molly K. Hooper, April 17, 2008. |