Federal Prison Industries: Background, Debate, Legislative History, and Policy Options

The Federal Prison Industries, Inc. (FPI), is a government-owned corporation that employs offenders incarcerated in correctional facilities under the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). The FPI manufactures products and provides services that are sold to executive agencies in the federal government. The FPI was created to serve as a means for managing, training, and rehabilitating inmates in the federal prison system through employment in one of its industries.

The FPI is intended to be economically self-sustaining and it does not receive funding through congressional appropriations. In FY2015, the FPI generated $472 million in sales, which is greater than the FPI’s sales in FY1993 ($405 million), but is below the FPI’s peak sales of $885 million in FY2009. The FPI operated at an $18 million loss for FY2015, the seventh straight fiscal year in which the FPI’s expenses exceeded revenues.

Data show that the number of FPI work assignments available to inmates has not kept pace with the growing federal inmate population. Starting in FY1988 the proportion of the federal inmate population employed by the FPI steadily deceased. In FY2015, approximately 7% of all federal inmates had an FPI work assignment.

The FPI manufactures products and provides services that are primarily sold to executive agencies in the federal government. In the past, federal departments and agencies were required to purchase products from the FPI. This requirement is sometimes referred to as the FPI’s “mandatory source clause.”

The debate about the FPI centers on the FPI’s mandatory source clause. Some policymakers believe the mandatory source clause impedes private vendors’ abilities to secure federal contracts. However, the FPI contends that the mandatory source clause is necessary to overcome some of the inefficiencies written into its authorizing legislation and problems associated with producing products in a prison environment, thereby allowing it to generate revenue and provide work opportunities for inmates.

Critics argue that the FPI’s lower labor costs provide it with a competitive advantage over private sector employers. The FPI asserts that any lower labor costs are more than offset by the disadvantages associated with operating a business inside a prison.

Advocates of the FPI maintain it is a proven rehabilitative program that does not cost taxpayers anything to operate and it helps provide for the orderly operation of a prison by keeping inmates occupied. Critics contend that vocational education programs have been shown to be more effective at reducing recidivism and inmates who participate in them are not competing with private sector workers for federal contracts.

Congress has taken legislative action to lessen any adverse impact the FPI has had on small businesses. For example, in 2002, 2003, and 2004, Congress passed legislation that modified how the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) procured products offered by the FPI in its schedule of products. In 2004, Congress passed legislation prohibiting federal agencies from using appropriated funding for FY2004 to purchase products or services offered by the FPI unless the agency determined that the products or services are provided at the best value. This provision was extended permanently in FY2005. In the 110th Congress, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (P.L. 110-181) modified the way in which DOD procures products from the FPI. In addition, the Administration of President George W. Bush made several efforts to reduce the consequences the FPI’s mandatory source clause might have on the ability of private businesses to compete for federal contracts.

Should Congress decide that it wants to try to reverse past trends and expand work opportunities for inmates, there are several options policymakers could consider. One option could be to expand a work-sharing initiative that the FPI has already started on a small scale. Congress could also consider replacing inmate work opportunities with vocational education programs. However, the BOP asserts that vocational and apprenticeship programs are not a substitution for, but rather a complement to, FPI work assignments. Congress might also consider allowing private businesses to compete for inmate labor on the open market. Congress has granted the FPI the authority to participate in the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP), which allows inmate labor to be used to produce goods for sale on the open market if certain conditions are met, such as paying inmates the prevailing wage for similar work. However, the FPI has had problems taking advantage of this new authority because the FPI would be required to pay inmates higher wages, thus increasing overhead costs. Also, inmates tend to be lower-skilled than non-incarcerated workers, which means that the prevailing wage requirement, and the additional costs associated with operating a business in a correctional environment, makes inmate labor less attractive to private businesses. This problem could be resolved by removing the prevailing wage requirement and allowing the market to set the price for inmate labor, but this raises questions about what effect inmate labor might have on non-incarcerated workers and the potential for inmate laborers to be exploited.

Federal Prison Industries: Background, Debate, Legislative History, and Policy Options

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- A Brief History of the FPI

- Activities

- The FPI's Sales and Earnings

- Inmate Participation in the FPI

- The Debate Over the FPI

- The Mandatory Source Clause: Central to the Debate

- The Issue of Competitive Advantage

- Rehabilitation and Management

- Discussion of Select Policy Options

- Work Sharing

- The Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program

- Challenges

- Alternatives to Current Policies

- Amending the Mandatory Source Clause

- Using Inmate Labor in the Open Market

Figures

Summary

The Federal Prison Industries, Inc. (FPI), is a government-owned corporation that employs offenders incarcerated in correctional facilities under the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). The FPI manufactures products and provides services that are sold to executive agencies in the federal government. The FPI was created to serve as a means for managing, training, and rehabilitating inmates in the federal prison system through employment in one of its industries.

The FPI is intended to be economically self-sustaining and it does not receive funding through congressional appropriations. In FY2015, the FPI generated $472 million in sales, which is greater than the FPI's sales in FY1993 ($405 million), but is below the FPI's peak sales of $885 million in FY2009. The FPI operated at an $18 million loss for FY2015, the seventh straight fiscal year in which the FPI's expenses exceeded revenues.

Data show that the number of FPI work assignments available to inmates has not kept pace with the growing federal inmate population. Starting in FY1988 the proportion of the federal inmate population employed by the FPI steadily deceased. In FY2015, approximately 7% of all federal inmates had an FPI work assignment.

The FPI manufactures products and provides services that are primarily sold to executive agencies in the federal government. In the past, federal departments and agencies were required to purchase products from the FPI. This requirement is sometimes referred to as the FPI's "mandatory source clause."

The debate about the FPI centers on the FPI's mandatory source clause. Some policymakers believe the mandatory source clause impedes private vendors' abilities to secure federal contracts. However, the FPI contends that the mandatory source clause is necessary to overcome some of the inefficiencies written into its authorizing legislation and problems associated with producing products in a prison environment, thereby allowing it to generate revenue and provide work opportunities for inmates.

Critics argue that the FPI's lower labor costs provide it with a competitive advantage over private sector employers. The FPI asserts that any lower labor costs are more than offset by the disadvantages associated with operating a business inside a prison.

Advocates of the FPI maintain it is a proven rehabilitative program that does not cost taxpayers anything to operate and it helps provide for the orderly operation of a prison by keeping inmates occupied. Critics contend that vocational education programs have been shown to be more effective at reducing recidivism and inmates who participate in them are not competing with private sector workers for federal contracts.

Congress has taken legislative action to lessen any adverse impact the FPI has had on small businesses. For example, in 2002, 2003, and 2004, Congress passed legislation that modified how the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) procured products offered by the FPI in its schedule of products. In 2004, Congress passed legislation prohibiting federal agencies from using appropriated funding for FY2004 to purchase products or services offered by the FPI unless the agency determined that the products or services are provided at the best value. This provision was extended permanently in FY2005. In the 110th Congress, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (P.L. 110-181) modified the way in which DOD procures products from the FPI. In addition, the Administration of President George W. Bush made several efforts to reduce the consequences the FPI's mandatory source clause might have on the ability of private businesses to compete for federal contracts.

Should Congress decide that it wants to try to reverse past trends and expand work opportunities for inmates, there are several options policymakers could consider. One option could be to expand a work-sharing initiative that the FPI has already started on a small scale. Congress could also consider replacing inmate work opportunities with vocational education programs. However, the BOP asserts that vocational and apprenticeship programs are not a substitution for, but rather a complement to, FPI work assignments. Congress might also consider allowing private businesses to compete for inmate labor on the open market. Congress has granted the FPI the authority to participate in the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP), which allows inmate labor to be used to produce goods for sale on the open market if certain conditions are met, such as paying inmates the prevailing wage for similar work. However, the FPI has had problems taking advantage of this new authority because the FPI would be required to pay inmates higher wages, thus increasing overhead costs. Also, inmates tend to be lower-skilled than non-incarcerated workers, which means that the prevailing wage requirement, and the additional costs associated with operating a business in a correctional environment, makes inmate labor less attractive to private businesses. This problem could be resolved by removing the prevailing wage requirement and allowing the market to set the price for inmate labor, but this raises questions about what effect inmate labor might have on non-incarcerated workers and the potential for inmate laborers to be exploited.

Introduction

The Federal Prison Industries, Inc. (FPI),1 is a government-owned corporation that employs offenders incarcerated in correctional facilities under the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). The FPI manufactures products and provides services that are primarily sold to executive agencies in the federal government. Although the FPI's industries are located within various federal prisons, they operate independently. The FPI was created to serve as a means for managing, training, and rehabilitating inmates in the federal prison system through employment in one of its six industries.

The FPI's enabling legislation2 and the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)3 require federal agencies to procure products offered by the FPI, unless authorized by the FPI to solicit bids from the private sector.4 This is commonly referred to as the "mandatory source clause."5 The FPI may grant waivers to executive agencies if its price exceeds the current market price for comparable products.6 Federal agencies, however, are not required to procure services provided by the FPI. Instead, agencies are encouraged to do so pursuant to the FAR.7 It is the mandatory source clause, and its effect on private businesses, that has drawn controversy over the years.

This report provides background on the FPI's operations and statutory authority. It does not address the related debates on inmate labor, criminal rehabilitation, or competition in federal government contracting.

Background

This section of the report provides background information on the FPI, including a brief history of the FPI, an overview of the FPI's current activities, a review of the FPI's sales and earnings for FY1993-FY2015, and data on trends in the number and proportion of federal inmates who work in the FPI.

A Brief History of the FPI

The FPI has its origins in an act passed in 1930 by the 71st Congress (P.L. 71-271). Even though there was growing hostility to prisoner-made goods at the time, the act expanded the use of inmate labor to all federal prisons. Prior to this act, in 1918 and 1924, Congress authorized the establishment of factories at two federal prisons (one in Atlanta and another in Leavenworth, KS).8 P.L. 71-271 required the Attorney General to provide work opportunities for all physically fit inmates, which could provide for their rehabilitation, and the sale of goods produced by inmates could help offset some of the cost of their incarceration. The act required the Attorney General to diversify the industries operated in the federal prison system in order to minimize competition with private businesses. The act allowed the Attorney General to make inmate labor available to federal agencies for the purpose of engaging in federal public works projects. It also allowed the Attorney General to establish industries where inmates would produce products that would be used in federal prisons or would be sold to other federal agencies. At the same time—in response to concerns raised by private business, trade associations, and labor organizations—the act prohibited inmate-made goods from being sold on the open market. The act required federal agencies to purchase products made by federal inmates if they did not exceed current market prices, were available for sale, and met their requirements. Congress established work programs for federal inmates as a way to reduce inmate idleness and provide for the reformation and rehabilitation of inmates.9 The act required the Attorney General to provide industrial work assignments that would give inmates the knowledge and skills necessary to find work after being released.

The BOP experienced difficulties implementing the authorities Congress granted the Attorney General to create and expand prison industries in order to provide work assignments for inmates. The House Judiciary Committee reported that "[a]ttempted diversification of prison employment by prison authorities has been met by resistance from every industry into the field of which is has sought to go even to a minor extent, and the major portion of prison-industry production has, therefore, been largely limited to the particular industries already carried on by the Bureau of Prisons prior to the enactment of [P.L. 71-271]."10,11 The committee noted that it was impossible to provide employment for all "physically fit inmates" without allowing the BOP to expand into new industries or to continue to capture an increasing market share.12

The FPI was created in 1934 when Congress passed and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed P.L. 73-461, which granted the President the authority to establish a federally chartered corporation known as the "Federal Prison Industries." Subsequently, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6917, which implemented the provisions of P.L. 73-461. Congress established the FPI—which was to be governed by a board of directors with representatives of labor, industry, agriculture, retailers, and consumers, and the Attorney General—as a way to help expand prison industries in a manner consistent with P.L. 71-271.13 The act allowed the President to transfer any of the powers vested with the Attorney General under P.L. 71-271 to the FPI. The board of directors was charged with determining in what manner and to what extent industrial operations would be conducted in federal prisons. The board was also required to diversify, to the extent practicable, prison industrial operations so that no one industry would face unfair competition from products made by the FPI.

P.L. 80-772 codified the FPI's authorizing legislation in Title 18 of the United States Code.14 This incarnation of the FPI's authorizing statute had many of the same elements of previous authorizations15 for federal prison industries.

- The FPI was to be administered by a board of directors which would be responsible for determining what products would be produced by the FPI.

- The goods made by the FPI could only be sold to the federal government.

- The FPI was required to provide employment for all physically fit inmates.

- The FPI was required to diversify, as much as practicable, its prison industries and decrease competition with the private sector.

- Jobs for federal inmates through the FPI were required to give inmates the opportunity to acquire knowledge and skills that would allow them to find work after being released.

- Federal agencies were required to purchase goods offered by the FPI if the goods met the agency's requirements, were available, and did not exceed market prices.

The FPI's authorizing legislation remained relatively unchanged for more than 50 years.16

The FPI's industrial production grew from the early 1940s through the late 1960s, spurred, in part, by providing goods for the federal government during World War II, and the Korean and Vietnam wars.17 Strong wartime demand raised the FPI's sales from approximately $7 million (nominal) in 1941 to nearly $19 million (nominal) in 1943.18 Demand for FPI products during the Korean War helped mitigate the decline in sales that resulted from the end of World War II.19 After the Korean War and during the late 1950s, the FPI invested in building new factories and renovating existing ones along with expanding vocational training.20 The purpose of the FPI's capital investment in the 1950s was to produce new products in response to changing markets. For example, the FPI opened new factories that specialized in the repair, refurbishment, and reconditioning of furniture, office equipment, tires, and other government property.21 Demand for products during the Vietnam War resulted in a short-term spike in production and sales.22 However, during the late 1960s, military orders were offset by cutbacks in purchases from civilian federal agencies, which resulted in declining overall sales.

The past 40 years marked a new approach for the FPI. In 1974 the FPI re-organized into seven different divisions, each of which was responsible for handling resource management, production, and sales in a specific FPI industry.23 At the same time, the FPI established regional market positions, and soon afterward, the FPI created a program to improve product quality and acceptability.24 Since the mid-1970s the FPI has focused on increasing sales through a greater emphasis on marketing and customer service and satisfaction. In 1977, the FPI introduced a new trade name: UNICOR.

Starting in the early 1980s, the federal prison population began a nearly unabated, three-decade increase. In FY1980 there were approximately 24,000 inmates in federal prisons; by FY1990 approximately 58,000 inmates; by FY2000 almost 126,000 inmates; and by FY2015 over 205,000 inmates in federal prisons. The growth in the federal prison population prompted the FPI to increase the number of factories it operated so it could employ a greater number of inmates.25 The FPI implemented additional state-of-the-art production techniques, which in turn increased product offerings and created new work opportunities for inmates.26 The new production techniques, according to the FPI, helped better prepare inmates for post-release employment.27 The FPI also started requiring inmates to have higher levels of literacy in order to advance beyond entry level pay status. By 1991, inmates working for the FPI were required to have a high school diploma or General Equivalency Degree (GED) in order to advance beyond the entry level pay grade.28

Activities

The FPI operates 80 factories and three farms in 62 federal prisons representing six different business segments:

- agribusiness,

- clothing and textiles,

- electronics,

- office furniture,

- recycling, and

- services (which include data entry and encoding).29

The FPI is intended to be economically self-sustaining and does not receive funding through congressional appropriations. The FPI uses the revenue it generates to purchase raw material and equipment; pay wages to inmates and staff; and invest in expansion of its facilities. Of the revenues generated by the FPI's products and services, 72% is used to purchase raw material and equipment; 23% funds staff salaries; and 5% funds inmate salaries.30 Inmates earn from $0.23 per hour up to a maximum of $1.15 per hour, depending on their proficiency, educational level, and time in the position, among other things. Additionally, inmates can earn bonuses based on work performance. Under BOP's Inmate Financial Responsibility Program, all inmates who have court ordered financial obligations must use at least 50% of their FPI income to satisfy those debts; the rest may be retained by the inmate.31

The FPI's Sales and Earnings

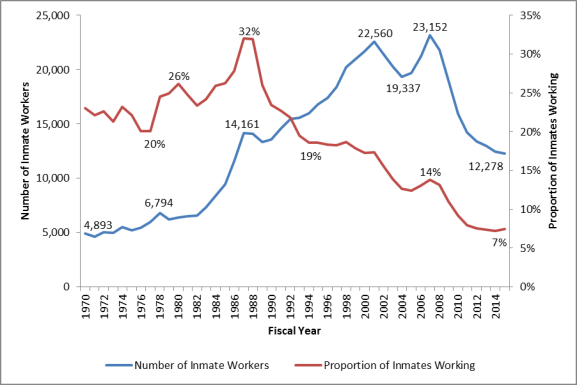

Figure 1 presents data on the FPI's sales and earnings (i.e., profits) since FY1993. In general, the FPI's sales increased between FY1993 and FY2009, increasing from $404.9 million to $885.3 million. In most of these fiscal years the FPI generated a profit. The two exceptions were FY1998 and FY2000, when the FPI reported losses of $2.4 million and $12.8 million in those respective fiscal years. The FPI's sales have declined in each of the past four fiscal years. The recent string of declining earnings represents a break with past trends. Between FY1993 and FY2008, when the FPI's sales decreased in one fiscal year, they almost always increased in the subsequent fiscal year. The FPI's sales in FY2014 were the lowest they have been, in nominal dollars, since FY1994. The recent trend of continuously declining sales broke in FY2015. The FPI reported sales of $471.9 million in FY2015, up from $389.1 million in FY2014. However, even with an increase in sales, the FPI still operated at a loss in FY2015, in line with the previous trend. The FPI has reported an operating loss for each of the last seven fiscal years.

The FPI has been able to sustain itself even though it has been operating at a loss for the past several fiscal years because it is able to draw funds from a revolving account (the "Prison Industries Fund") into which money received from the sale of the products or by-products of the FPI, or for the services of federal prisoners working in FPI, is to be deposited.32 In short, the FPI has been able to make up for operating losses by drawing on funds from previous fiscal years in which it was able to turn a profit.

|

Figure 1. Sales and Earnings for the Federal Prison Industries, FY1993-FY2015 Sales and earnings in millions of dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data provided by the U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries. Note: Sales and earnings amounts reported in Figure 1 are in nominal dollars. |

Inmate Participation in the FPI

Under current law, all physically able inmates who are not a security risk are required to work.33 Those inmates who are not employed by the FPI have other labor assignments in the prison. FPI work assignments are usually considered more desirable because wages are higher and they allow inmates to learn a trade. However, this is not to discount the importance of regular prison work assignments. Both regular and FPI work assignments can provide inmates with "soft skills" (e.g., punctuality, learning the importance of doing a job correctly, following directions from supervisors). Also, both types of work assignments can contribute to institutional order by reducing inmate idleness. Regular prison work assignments provide for the operation and maintenance of prison facilities; hence, these work assignments will exist as long as BOP operates prisons. The availability of FPI work assignments is more volatile.

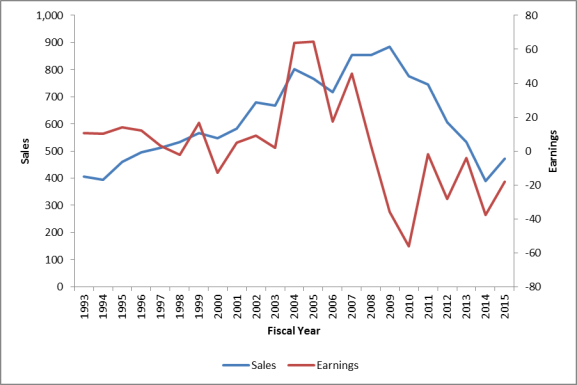

Data show that the number of FPI work assignments available to inmates has not kept pace with the growing federal inmate population. As shown in Figure 2, even though the number of inmates employed by the FPI generally increased between FY1970 and FY2001, starting in FY1988 the proportion of the federal inmate population employed by the FPI began a steady decease. There has been a noticeable decrease in the number of inmates working for the FPI since FY2007, when the number of inmates holding FPI work assignments peaked at approximately 23,200 inmates. Since FY2007, the number of inmates working for the FPI decreased to approximately 12,300 in FY2015. The decreasing number of inmates employed by the FPI corresponds with the FPI's decreasing sales, which has resulted in the FPI shuttering some factories.

The Debate Over the FPI

The debate surrounding the FPI often centers on two competing visions of what it does—is it a business vying for federal contracts or is it a rehabilitative program for prisoners? The BOP considers the FPI to be a rehabilitative program, not a business. As Harley Lappin, former Director of the BOP, stated in his testimony during a hearing on the FPI:

The FPI program's purpose is not to be a business that generates revenue. Rather, it is a correctional program charged with the goal of providing meaningful work opportunities for Federal offenders.... Although the FPI program produces products and performs services, the real output of the FPI program is inmates who are more likely to return to society as law-abiding taxpayers because of the job skills training and work experience they received in the FPI program.34

Critics view the FPI as a business competing with others for federal contracts. Even though the BOP contends that the real product the FPI produces is rehabilitated inmates, opponents note that the FPI produces goods and services that are sold to the federal government, in many cases with advantages not available to the private sector.

Opponents of the FPI argue that providing work opportunities for federal inmates has come at the cost of jobs for law-abiding citizens.35 Further, critics contend that if inmate labor is allowed to displace private sector workers it can cost the federal government revenues it might collect from corporate and/or individual taxes.36 In addition, competition from inmate labor might shrink the private sector job market in fields where inmates are learning their skills while participating in the FPI program, thereby limiting the ability of inmates to find employment after being released.37

The Mandatory Source Clause: Central to the Debate

The debate regarding the competing visions of the FPI revolves around its mandatory source clause, the requirement for federal agencies to purchase products from the FPI. The FPI does not have the same level of preference when it comes to the procurement of services. Instead, agencies are encouraged to do so pursuant to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR). It is the mandatory source clause, and its effect on private businesses, that has drawn controversy over the years.

Since the 1990s, Congress scrutinized the requirement for federal agencies to purchase products from the FPI if they are available for sale by the FPI, meet the agency's delivery schedule and quality requirements, and are not above market price. Congress's increased interest in the FPI's mandatory source clause is driven, in part, by concerns of private businesses that the FPI is monopolizing the federal procurement market and taking jobs from law-abiding citizens.38 Since 2002, Congress has made a series of changes to the FPI's mandatory source clause in response to these concerns (these changes are described in more detail in the Appendix).

Despite these legislative changes, the FPI's mandatory source clause continues to be a point of contention between advocates and opponents of the program. Opponents argue that recent changes (see the Appendix) to the FPI's mandatory source clause have not gone far enough. They argue that the FPI's mandatory source clause produces a monopoly-like environment that usurps the bidding process for federal contracts. Federal agencies are still required to purchase FPI-produced goods if they meet their needs in terms of price, quality, and timeliness of delivery. Critics maintain that the FPI's mandatory source clause should be completely eliminated and the FPI should have to compete for all federal contracts.39 This is, opponents believe, the one way to ensure that private businesses are able to compete equally with the FPI.

Proponents of the FPI contend that legislative and administrative changes to the FPI's mandatory source clause allow federal agencies to purchase products from private vendors. Former Director Lappin states that the FPI's mandatory source clause

does not mean that the FPI program prohibits Federal customers from purchasing from private vendors. Many of the FPI program's products are only offered as "non-mandatory" items, meaning that competitive procurement procedures apply. Finally, for those FPI program products to which mandatory source applies, it does so only in a limited way. Recent legislation and FPI Board of Directors resolutions have dramatically reduced the effect of mandatory source.40

The Issue of Competitive Advantage

One criticism of the FPI is that it has a competitive advantage over the private sector. Critics argue that the FPI has lower labor costs. For example, prisoner wages in FPI are far below the minimum wage in the private sector. Critics note that FPI inmate workers earn between $0.23 and $1.15 per hour. Critics also contend that the FPI has other competitive advantages. For example, as a wholly owned government corporation, the FPI is exempt from federal and state income taxes, gross receipt taxes, and property taxes.41 Also, since the FPI employs federal inmates, health care costs are covered by the BOP. In addition, the BOP pays the cost of building factory space for the FPI and the BOP covers the cost of the FPI's utilities.42

Proponents note that the FPI faces several competitive disadvantages which might negate the fact that the FPI can pay inmate workers lower wages. While inmates receive far lower pay than workers in private industry, the FPI asserts this advantage is offset by the lower average productivity of inmates and the inefficiencies associated with operating a business in a correctional setting.43 In addition, the FPI contends that any advantage it might gain from lower wages is offset by statutory constraints that drive up costs. These include

- employing as many inmates as reasonably possible;

- concentrating on manufacturing products that are labor-intensive;

- providing opportunities for inmates to acquire marketable skills;

- diversifying production as much as possible to minimize competition with private industry and labor, and reduce the burden on any one industry;

- not taking more than a reasonable share of the federal market for any one product; and

- selling products only to the federal government.44

According to the FPI, additional costs also lower its competitiveness. The FPI reports that the average inmate worker, due in part to lower levels of education and a lack of regular employment, is approximately one-quarter as productive as a non-incarcerated worker.45 The FPI has to train (a further cost) most inmate workers how to perform their jobs while private businesses have the ability to hire workers who have the requisite job skills. The FPI notes that expenses such as supervision of inmate workers and measures necessary to maintain the security of the prison add to the cost of production.46 The FPI also argues that its operations benefit private businesses. The FPI uses revenue it generates from sales to the federal government to purchase raw materials and supplies from private vendors. In FY2015, the FPI spent 72% of its revenue, or $362 million, on purchases from the private sector.47

Rehabilitation and Management

Advocates of the FPI maintain it is a proven rehabilitative program that does not cost taxpayers anything to operate. Research conducted by the BOP shows that, 12 months after being released from prison, inmates who participated in the FPI were 35% less likely than inmates from a comparable control group to have recidivated (6.6% compared to 10.1%).48 Inmates who participated in the FPI were also 14% more likely to be employed after 12 months (71.7% compared to 63.1%).49 The researchers found that over the long term (between 8 and 12 years after release), inmates who participated in the FPI were 24% less likely to have recidivated than inmates in the comparison group.50

A review of research on the effects of participation in correctional industries on recidivism found that inmates who participated in correctional industry programs recidivated at a lower rate than those who did not, but only the results from one of the two studies included in the review were statistically significant.51

Proponents also contend that the FPI is an important inmate management tool, which is more important than ever given the continued growth in the federal prison population. Work assignments through the FPI keep inmates productively occupied, thereby reducing inmate idleness and associated violence.52 Proponents argue that FPI work assignments encourage good behavior because inmates must have completed high school or have a GED if they want to advance past an entry-level position.53 In addition to helping inmates learn a trade, proponents note that the FPI provides inmates with "soft skills" (e.g., punctuality, learning the importance of doing a job correctly, following directions from supervisors).54

It has been argued that the BOP's own evaluation of the FPI program demonstrates that a more effective way to reduce recidivism would be to place more inmates in vocational education programs and reduce the size of the FPI. The same study which found that 8 to 12 years after being released, inmates who participated in the FPI program were 24% less likely to have been re-incarcerated than inmates in a comparable control group, also noted that inmates who participated in either vocational or apprenticeship training were 33% less likely to have been re-incarcerated.55 Another study indicates that vocational education programs "work to significantly reduce recidivism."56

The BOP also asserts that vocational and apprenticeship programs are not a substitution for, but rather a complement to, FPI work assignments.57 The BOP argues that vocational training programs alone do not provide inmates with sufficient job skills training and work experience. In addition, the programs are only provided on a part-time schedule rather than for a full day. Finally, vocational education programs are only meant to run for a limited time (18-24 months), and they are funded through appropriations, unlike the FPI.

Discussion of Select Policy Options

Any future deliberation about the scope of the FPI's activities will probably focus on the same policy question posed in past debates: How can the FPI continue to provide work opportunities for inmates while minimizing the effect on the private sector? Two current programs could expand employment opportunities for inmate workers while, in theory, having minimal effect on private sector workers.

Work Sharing

The FPI has started a work-sharing initiative, by which two inmates work part-time to fill a single full-time position.58 The initiative was "intended to increase the number of inmate workers employed by the FPI while minimizing the impact on factory efficiency and costs."59 A work-sharing initiative has the potential benefit of increasing the number of inmate workers while not requiring the FPI to expand into new markets or increase its presence in existing markets. While a work-sharing initiative could increase the number of inmates exposed to the FPI, it would also decrease the amount of time inmates are exposed to the program. The literature on the relationship between correctional industries participation and recidivism does not address whether the duration of exposure to the program has any effect on outcomes. It is possible that working part-time would have a minimal effect on the ability of the program to reduce recidivism, assuming that the inmate spends enough time in the program to internalize the skills and discipline that, in theory, contribute to reduced recidivism. However, the ability of a work-sharing program to increase the number of inmates with a work assignment still depends on the ability of the FPI to sell products and services that generate work assignments for inmates. As discussed previously, the number of inmate workers employed by the FPI decreased between FY2007 and FY2015 and the proportion of inmates employed by the FPI started decreasing after FY1988.

The Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program

Congress has granted the FPI the authority to participate in the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP) and to manufacture goods for the commercial market if they are currently or would have otherwise been manufactured outside the United States (i.e., repatriation authority).60 In granting the FPI these authorities, Congress expressed concern that inmates did not have access to meaningful work opportunities.61 In addition, Congress acknowledged that the FPI functions as a means of preparing inmates for reentry and that if the FPI were allowed to enter into partnerships with private businesses, it could bring some manufacturing lost overseas back to the United States while providing inmates with opportunities to learn skills that will be marketable after release.62

PIECP allows private businesses, under certain conditions, to use inmate labor to produce goods that can be sold on the open market. PIECP has requirements in place to protect workers from unfair competition with inmate labor. For example, inmates participating in a certified program must be paid the prevailing wage for similar work in the same locality, there must be written assurances that inmates will not be used to displace private-sector workers, and there must be proof of consultation with organized labor and private industry before the program starts.63

Challenges

It is possible that neither of these options will greatly expand the FPI's capacity to provide inmate work assignments. The DOJ Office of the Inspector General (OIG) notes that "in general, repatriation has been less successful than expected, primarily due to unanticipated difficulties identifying domestic business partners willing to associate with the use of inmate labor."64 In addition, the DOJ OIG reports that "FPI officials ... viewed [PIECP] as a less viable option for new business development than the repatriation authority ... under [PIECP], FPI would be required to pay inmates higher wages, thus increasing overhead costs."65 Additionally, the FPI noted that, based on their assessment of currently certified programs and the variability of market rate wages across the country, the FPI was "unlikely to be able to pursue regional or nationwide programs, but instead might have to identify smaller, niche markets to be successful."66 One of the downsides of PIECP, in terms of its ability to increase opportunities for inmates to work, is that its prevailing wage requirement can make inmate labor less attractive to private companies since most inmates are low-skilled individuals who would command a lower wage in the private market.67 In addition, the prevailing wage requirement, when combined with additional costs associated with operating a business in a prison environment (e.g., additional security costs, frequent employee turnover, and lost productivity due to disciplinary actions such as prison-wide lock-downs) can erode a business's profit margins.68

Alternatives to Current Policies

Policymakers might also consider exploring other alternatives for increasing the number of work opportunities for inmates beyond the options implemented thus far.

Amending the Mandatory Source Clause

Legislation has been introduced that would eliminate the FPI's mandatory source clause and require the FPI to compete for federal contracts.69 The legislation would authorize funding for vocational education programs. It would also authorize appropriations to pay inmate wages for work they perform for nonprofit or religious organizations, local governments, and school districts and to pay inmate wages for products and services donated to nonprofit or religious organizations that serve low-income individuals.

This proposal would resolve any tension surrounding the FPI's mandatory source clause and its effect on private vendors' ability to secure federal contracts. However, by authorizing funding for programs to help keep inmates employed or engaged in vocational programs, it tacitly acknowledges how important the mandatory source clause is to the FPI's ability to provide work opportunities for inmates. Should Congress choose to require the FPI to compete for all federal contracts, policymakers might consider whether to amend the authorizing legislation for the FPI so it can operate more efficiently.

As previously discussed, current law requires the FPI to provide employment for as many inmates as reasonably possible and to diversify its product line to minimize its effect on the private sector. In fact, the BOP argues that the FPI's mandatory source clause is necessary because the requirements to employ as many inmates as reasonably possible and to diversify its product line are in place. These are requirements that private sector businesses do not have to contend with. Businesses can hire and lay off employees based on demand for their products or services. Businesses can also choose to produce only one or a handful of products and services, which allows the business to effectively compete against other business by learning how to efficiently produce its product or service. Even if Congress removed these requirements, the FPI argues it would still be operating with several competitive disadvantages, such as using a lower-skilled workforce, frequent turnover in employees, and operating a business in a correctional environment. However, the FPI would still have some competitive advantages, such as being able to pay inmates a lower wage and having some labor costs (e.g., health care) covered by the BOP.

In addition, there would likely be the concern, and one that is central to the debate over the FPI, that if Congress lifted some of the current restrictions on the FPI's operations, the FPI would control the market for some products. However, if the FPI could specialize in producing only a handful of products or services it might be able to learn to operate more efficiently, which could result in increased sales and more work opportunities for inmates, although, increased work opportunities for inmates might come at the cost of jobs for non-incarcerated individuals.

Keeping inmates constructively occupied through the use of vocational education programs has the potential to reduce the effect of inmate labor on the private market. Also, as outlined previously, it has been argued that vocational educational programs are more effective at reducing recidivism than work assignments through correctional industries. However, the BOP asserts that vocational and apprenticeship programs are not a substitution for, but rather a complement to, FPI work assignments.70 In addition, vocational programs, unlike FPI work assignments, are funded through direct appropriations.

Congress may consider allowing inmate labor to be used to provide products and services for nonprofit and religious organizations, which could provide work opportunities for inmates while decreasing competition with private businesses. However, this work would have to be subsidized though direct appropriations. Furthermore, there might be a question as to how much demand there would be in this potential market. The FPI's problems with expanding production under its repatriation authority show that some organizations do not want to be associated with inmate labor.

Using Inmate Labor in the Open Market

Another option to provide more work opportunities for inmates might be to repeal federal laws that prohibit the sale of prisoner-made goods on the private market71 and allow businesses to compete for inmates' labor on the open market. As previously discussed, the FPI has employed a decreasing proportion of the federal prison population and PIECP-certified business ventures employ a nominal proportion of prisoners. This might raise questions as to whether having inmates only produce products for consumption by federal agencies or expanding the FPI's authority to participate in PIECP will provide an adequate amount of work opportunities for inmates. The relative lack of success of PIECP suggests that in order for this option to be successful it is likely that there could not be a minimum wage or prevailing wage requirement; and the market would be allowed to determine how much businesses are willing to pay to hire inmates.72 Inmates tend to be lower skilled than non-incarcerated individuals, meaning they generally have a lower level of productivity. When this is combined with the additional cost of operating a business in a correctional environment, minimum wage or prevailing wage requirements make inmate labor look less attractive, thereby limiting work opportunities for inmates. Policymakers could consider keeping prevailing wage requirements in place, but a subsidy might have to be offered in order to make inmate labor attractive to private businesses.

Some policymakers might be concerned about what effect additional inmate labor force participation might have on private workers. It has been noted that due to inmate workers' low level of productivity, the economic impact of inmate labor is likely to be minor.73 It has been estimated that an inmate worker is about one-third as productive as an average member of the workforce.74 Based on an estimate of per-prisoner hourly output, even if every inmate in federal prisons at the end of FY2015 worked full-time, federal inmates' output would have equaled approximately 0.04% of the United States' 2015 gross domestic product.75 Research suggests that increased inmate labor force participation would have minimal effect on the wages of low-skilled workers and their level of unemployment.76

Even if increased inmate workforce participation had a minimal effect overall, it is still possible that certain groups of workers would be disproportionately affected by a change in current restrictions on inmate labor. One scholar compares a potential expansion of inmate labor force participation to increased competition from foreign low-skilled laborers. He notes: "[w]orkers employed in industries that move 'overseas' and into the prison would lose their jobs, as would workers employed by firms unable to compete with newly created prison industries. The impact would be most severe in those sectors of the market in which prison industries concentrate."77 In addition, since any economic benefits, such as lower prices for consumers or a larger workforce of lower-skilled laborers willing to work for lower wages, are likely to be small, and increased inmate labor force participation could lead to non-inmate workers losing jobs, it might be argued that the economic costs of allowing inmates to work in the private market exceed any potential economic benefits.78

Policymakers might also consider other possible benefits and costs beyond the possible economic effects of increased inmate labor force participation. Subjecting correctional industries to competition and the effects of the private market might help them operate more efficiently.79 If working in a correctional industry reduces recidivism, expanding inmate work opportunities could have a significant social benefit through reduced prison costs resulting from reduced recidivism. Also, reduced recidivism could reduce costs associated with fewer crime victims. If inmates earn a wage they can use the money to support dependents, help offset the cost of incarceration, or save some of the money for post-release expenses. Inmates might also be able to start establishing connections with employers that could help facilitate post-release employment. However, any potential benefits of increased inmate labor force participation might be negated by the social costs associated with displaced workers potentially turning to criminal activity.80

Potentially allowing businesses to use inmate laborers might raise other concerns beyond those of the possible economic effects of increased inmate labor force participation. Businesses using inmate labor might conjure up images of corruption and abuse associated with the inmate leasing system,81 a system under which some inmates labored under unsafe conditions, and in some instances, died.82 The most egregious abuses of inmates under the lease system occurred at a time when the law considered inmates to be "slaves of the state" and courts generally allowed states to operate prisons with little oversight.83 Developments in the last half of the 20th century, such as more judicial oversight of prison systems and the "prisoners' rights movement," have reduced the probability that the abuses associated with the inmate lease system would be allowed to occur.84 However, since inmates cannot "vote with their feet" and take their labor to an employer that provides a higher wage or better working conditions, there is a possibility that inmates could be exploited.85 Should Congress expand the use of inmate labor in private markets, the conditions under which inmates labor could be a point of oversight for policymakers. It has been proposed that allowing inmates to unionize might provide some protection against possible exploitation.86 Also, ensuring that inmates have the choice not to work could help prevent exploitation of inmate labor by private businesses.87

Appendix. A Brief Legislative History of the FPI

While the FPI was originally created in 1934 through P.L. 73-461 and implemented by Executive Order 6917, the current statutory authority for the FPI was first codified in the 1948 revision of the "Crimes and Criminal procedure" statutes.88

Concerns about whether the mandatory source clause has prevented private businesses from competing for federal contracts have led Congress to include language in certain legislation that modified how federal agencies procured products under the FPI's mandatory source clause.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-690) required that the FPI meet specific requirements to ease the potential impact of its activities upon the private sector. Before approving the expansion of an existing product or the creation of a new product, the act required the FPI to

- prepare a written analysis of the likely impact of the FPI's expansion on industry and free labor;

- announce in an appropriate publication the plans for expansion and invite comments on the plan;

- advise affected trade associations;

- provide the FPI's Board of Directors with the plans for expansion prior to the Board making a decision on the expansion;

- provide opportunity to affected trade associations or relevant business representatives to comment to the Board of Directors on the proposal; and

- publish final decisions made by the Board of Directors.

The Crime Control Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-647) required each federal department, agency, and institution that is required to purchase products pursuant to the FPI's mandatory source clause to separately report acquisitions of products and services from the FPI to the General Services Administration (GSA) for entry into the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS).

The Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act of 1992

The Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-564) modified the reporting requirement established by the Crime Control Act of 1990 so that federal departments, agencies, and institutions reporting data to the FPDS on acquisitions from the FPI report their data in the same manner as they report data on non-FPI acquisitions.

General Accounting Office Act of 1996

The General Accounting Office Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-316) amended the authorizing legislation for the FPI89 so that the Attorney General, the Administrator of General Services, and the President, or their representatives, were the arbitrators of disputes as to the price, quality, character, or suitability of products produced by the FPI. Prior to this, disputes were arbitrated by the Comptroller General, the Administrator of General Services, and the President, or their representatives.

The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2002

The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2002 (P.L. 107-107) required the Secretary of Defense to use competitive procedures for the procurement of a product if it was determined that the FPI's product was not comparable in price, quality, and time of delivery to products available from the private sector. In doing so, the act required the Secretary of Defense to conduct research and market analysis with respect to the price, quality, and time of delivery of the FPI products prior to purchasing the product from the FPI to determine whether the products are comparable to products from the private sector.

The Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act for FY2003

The Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2003 (P.L. 107-314) amended 10 U.S.C. §2410n to require the Secretary of Defense to use competitive procedures for the procurement of a product if it is determined that the FPI's product is not comparable in price, quality, and time of delivery to products available from the private sector. With respect to the market research determination, the act made such determinations final and not subject to review. The act required that the FPI perform its contractual obligations to the same extent as any other contractor for the DOD. Under the act, contractors or potential contractors cannot be required to use the FPI as a subcontractor or as a supplier of products or services for performance of a contract. It prohibits the Secretary of Defense from entering into a contract with the FPI under which an inmate worker would have access to sensitive information.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2004

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-199) modified the FPI's mandatory source clause by prohibiting funds appropriated by Congress for FY2004 to be used by any federal executive agency for the purchase of products or services manufactured by the FPI unless the agency making the purchase determines, pursuant to government-wide procurement regulations, that the products or services are being provided at the best value.

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005 (P.L. 108-447) permanently extended the provision in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-199) related to the FPI's mandatory source clause. The provision prevents federal agencies from using appropriated funds for purchasing the FPI's products or services unless the agency making the purchase determines, pursuant to government-wide procurement regulations, that the product or service provides the best value for the agency.

Intelligence Authorization Act for FY2004

The Intelligence Authorization Act for FY2004 (P.L. 108-177) required the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency to only make purchases from the FPI if he determines that the product or service best meets the agency's needs.

The National Defense Authorization Act for FY2008

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (P.L. 110-181) amended 10 U.S.C. §2410n to require the Secretary of Defense to do market research to determine whether the FPI has a significant market share of the product before purchasing that product from the FPI.90 In cases where the FPI is determined to have a significant market share, the Secretary of Defense can purchase a product from the FPI only if the Secretary uses competitive procedures for procuring the product, or makes an individual purchase under a multiple award contract in accordance with the competition requirements applicable to such a contract. In cases where the FPI does not have a significant market share, the DOD is required to determine whether the product offered by the FPI meets its needs in terms of price, quality, and time of delivery. In cases where the FPI product does not meet the DOD's needs in terms of price, quality, and time of delivery, the DOD is required to procure the product through competitive procedures. The DOD is required to consider a timely offer from the FPI.

Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2011

In the conference report for the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2011 (P.L. 112-55), Congress expressed concern that inmates did not have access to meaningful work opportunities.91 In addition, Congress acknowledged that the FPI functions as a means of preparing inmates for reentry and that if the FPI were allowed to enter into partnerships with private businesses, it could bring some lost manufacturing back into the United States while providing inmates with opportunities to learn skills that would be marketable after release.92 As a part of the act, Congress amended 18 U.S.C. §1761(c) to allow the FPI to participate in the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP).93 The act also allows the FPI to manufacture goods for the commercial market if they are currently or would have otherwise been manufactured outside the United States.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The FPI is sometimes referred by its trade name, UNICOR. |

| 2. |

See 18 U.S.C. §4121 et seq. |

| 3. |

The FAR was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-400). The FAR is parts 1-63 of Title 48 of the Code of Federal Regulations. |

| 4. |

Under current law (18 U.S.C. §4124(a)) and regulations (48 C.F.R.), federal agencies must procure products from FPI, unless granted a waiver by the FPI (48 CFR §8.604), that are listed as being manufactured by UNICOR in the corporation's catalog or schedule of products. |

| 5. |

Also referred to as "superpreference," "sole source," or "preferential status." |

| 6. |

See Bureau of Prisons Program Statement 8224.02, FPI Pricing Procedures. |

| 7. |

The FAR encourages federal agencies to treat the FPI as a "preferential source" in the procurement of services. |

| 8. |

Michael C. Groh, "FAR (8.602) Gone: A Proposal to Maintain the Benefits of Prison Work Programs Despite the Restructuring of Federal Prison Industries' Mandatory Source Clause," Public Contract Law Journal, vol. 42, no. 2 (Winter 2013), p. 396, hereinafter "FAR (8.602) Gone." |

| 9. |

The House Judiciary Committee noted that "[d]ue to the lack of facilities an appalling number of our Federal prisoners are compelled to remain in idleness or semiidleness. Idleness is equal to crime. No man should be sentenced to idleness. From every viewpoint, humanitarian, social, and economic, prisoners should be given some occupation." U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Employment of Federal Prisoners, Report to accompany H.R. 7412, 71st Cong., 2nd sess., January 6, 1930, H.Rept. 71-103, p. 1. The Senate Judiciary Committee noted that "[i]t is unanimously conceded that idleness in prison breeds disorder and aggravates criminal tendencies. If there is any hope for reformation and rehabilitation of those convicted of crimes, it will be founded upon the acquisition by the prisoner of the requisite skill and knowledge to pursue a useful occupation and the development of habits of industry." U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Employment of Federal Prisoners, Report to accompany H.R. 7412, 71st Cong., 2nd sess., April 25, 1930, S.Rept. 71-529, p. 2. |

| 10. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Prison Industries Board, Report to accompany H.R. 9404, 73rd Cong., 2nd sess., May 1, 1934, H.Rept. 73-1421, p. 1. |

| 11. |

Inmates in the federal prison in Atlanta manufactured cotton products for the War and Navy Departments, while inmates in the federal prison in Leavenworth manufactured shoes, brooms, and brushes. All goods produced by inmates in the two federal prisons were solely for use by federal agencies. FAR (8.602) Gone, p. 395. |

| 12. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Prison Industries Board, Report to accompany H.R. 9404, 73rd Cong., 2nd sess., May 1, 1934, H.Rept. 73-1421, p. 2. |

| 13. |

Ibid. |

| 14. |

The FPI's statutory authority is codified at 18 U.S.C. §4121 et seq. |

| 15. |

P.L. 73-461 and Executive Order 6917. |

| 16. |

P.L. 81-72 (63 Stat. 98) added the Secretary of Defense to the FPI's board of directors and it allowed the board to provide for the vocational training of inmates without regard to their industrial or other assignments. P.L. 100-690 (102 Stat. 4413) changed the statutory authority for the FPI so that the FPI only had to employ the greatest number of inmates who are eligible to work as reasonably possible. The act also established a series of requirements for the FPI before the FPI could expand an existing product line or establish a new one. |

| 17. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries, Factories with Fences: 75 Years of Changing Lives, pp. 20-23, hereinafter "Factories with Fences." |

| 18. |

FAR (8.602) Gone, p. 397. |

| 19. |

Ibid. |

| 20. |

Factories with Fences, p. 21. |

| 21. |

Ibid. |

| 22. |

Ibid., p. 23. |

| 23. |

Ibid. |

| 24. |

Ibid. |

| 25. |

The FPI is mandated by statute to "... provide employment for the greatest number of those inmates in the United States penal and correctional institutions who are eligible to work as is reasonably possible ..." 18 U.S.C. §41229(b)(1). The FPI has a stated goal of employing 25% of work-eligible inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries, FY2015 Congressional Budget, Federal Prison Industries, p.1. |

| 26. |

Factories with Fences, p. 24. |

| 27. |

Ibid. |

| 28. |

Ibid. |

| 29. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries, Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Management Report, November 16, 2015, hereinafter, "FPI FY2015 Annual Management Report." |

| 30. |

Federal Prison Industries, FPI General Overview FAQs, http://www.unicor.gov/FAQ_General.aspx#4. |

| 31. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Custody & Care, UNICOR, Program Details, https://www.bop.gov/inmates/custody_and_care/unicor_about.jsp. |

| 32. |

See 18 U.S.C. §4126(a). |

| 33. |

Title XXIX, §2905 of the Crime Control Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-647) required that all offenders in federal prisons must work (the act permitted limitations to this rule on security and health-related grounds). |

| 34. |

Testimony of former Director of the Bureau of Prisons, Harley G. Lappin, U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, Federal Prison Industries—Examining the Effects of Section 827 of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2008, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., May 6, 2008, Serial Number 110-150 (Washington: GPO, 2009), p. 3, hereinafter, "Testimony of former BOP Director Lappin." |

| 35. |

Diane Cardwell, "Competing With Prison Labor," New York Times, March 15, 2012, p. B1. |

| 36. |

Testimony of John M. Palatiello, President, Business Coalition for Fair Competition in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Contracting and Workforce, Unlocking Opportunities: Recidivism Versus Fair Competition in Federal Contracting, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., June 28, 2012 (Washington: GPO, 2012), p. 47. |

| 37. |

Ibid. |

| 38. |

FAR (8.602) Gone, p. 399. |

| 39. |

See for example, the testimony of Congressman Bill Huizenga, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Contracting and Workforce, Unlocking Opportunities: Recidivism Versus Fair Competition in Federal Contracting, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., June 28, 2012 (Washington: GPO, 2012), pp. 38-41. |

| 40. |

Testimony of former BOP Director Lappin, p. 13. |

| 41. |

FPI FY2015 Annual Management Report. |

| 42. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Federal Prison Industries Competition in Contracting Act of 2006, Report to accompany H.R. 2965, 109th Cong., 2nd sess., July 21, 2006, H.Rept. 109-591 (Washington: GPO, 2006), p. 25. |

| 43. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries, Federal Prison Industries: The Myths, Successes, and Challenges of One of America's Most Successful Government Programs, on file with author, hereinafter "FPI: Myths, Successes, and Challenges." |

| 44. |

18 U.S.C. §4122. |

| 45. |

FPI: Myths, Successes, and Challenges. |

| 46. |

Ibid. |

| 47. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prison Industries, FPI General Overview FAQs, http://www.unicor.gov/FAQ_General.aspx#4. |

| 48. |

"Recidivism" was defined as having post-release supervision revoked due to a technical violation or being arrested for a new crime. William G. Saylor and Gerald G. Gaes, PERP: Training Inmates Through Industrial Work Participation, and Vocational and Apprenticeship Instruction, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Washington, DC, September 24, 1996, p. 18. |

| 49. |

Ibid. |

| 50. |

Ibid., p. 22. |

| 51. |

The study conducted by the BOP was one of the two studies included in the review, and it was the one with the statistically significant results. The author also noted that the studies included in the review might have suffered from selection bias, i.e., inmates who participated were different from those who did not. Doris Layton MacKenzie, What Works in Corrections: Reducing the Criminal Activities of Offenders and Delinquents (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 101-102. |

| 52. |

Testimony of Dale Deshotel, President, Council of Prison Locals, Bureau of Prisons, American Federation of Government Employees, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Contracting and Workforce, Unlocking Opportunities: Recidivism Versus Fair Competition in Federal Contracting, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., June 28, 2012 (Washington: GPO, 2012), p. 70, hereinafter "Testimony of Dale Deshotel." |

| 53. |

Ibid. |

| 54. |

FAR (8.602) Gone, p. 406. |

| 55. |

William G. Saylor and Gerald G. Gaes, PERP: Training Inmates Through Industrial Work Participation, and Vocational and Apprenticeship Instruction, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, Washington, DC, September 24, 1996, p. 22. |

| 56. |

The results of the analysis indicate that if 50% of inmates who did not participate in vocational education programs recidivated, only 39% of those who participated would also recidivate. Doris Layton MacKenzie, What Works in Corrections: Reducing the Criminal Activities of Offenders and Delinquents (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 94. |

| 57. |

Testimony of former BOP Director Lappin, p. 19. |

| 58. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, Audit of the Management of Federal Prison Industries and Efforts to Create Work Opportunities for Federal Inmates, Audit report 13-35, Washington, DC, September 2013, p. 18, hereinafter "DOJ OIG's audit of the FPI's efforts to create work opportunities." |

| 59. |

Ibid. |

| 60. |

Section 221 of the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2012 (P.L. 112-55, 125 Stat. 621). |

| 61. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Programs for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2012, and for Other Purposes, Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 2112, 112th Cong., 1st sess., November 14, 2011, H.Rept. 112-284 (Washington: GPO, 2011), p. 241. |

| 62. |

Ibid. |

| 63. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Program Brief: Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program, NCJ 193772, July 2002, p. 3, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/193772.pdf. |

| 64. |

DOJ OIG's audit of the FPI's efforts to create work opportunities, p. 22. |

| 65. |

Ibid. |

| 66. |

Ibid. |

| 67. |

Stephen P. Garvey, "Freeing Prisoners' Labor," Stanford Law Review, vol. 50, no. 2 (January 1998), p. 373, hereinafter "Freeing Prisoners' Labor." |

| 68. |

Ibid. |

| 69. |

See H.R. 1699, the Federal Prison Industries Competition in Contracting Act of 2015. Legislation that is similar, in whole or in part, to H.R. 1699 has been introduced in past congresses. See, for example, H.R. 2098 (introduced, 113th Congress); H.R. 3634 (introduced, 112th Congress); H.R. 2965 (passed by the House, 109th Congress); H.R. 1829 (passed by the House, 108th Congress); H.R. 1577 (reported by the House Judiciary Committee, 107th Congress); H.R. 2551 (introduced, 106th Congress); and H.R. 2758 (introduced, 105th Congress). |

| 70. |

Testimony of former BOP Director Lappin, p. 19. |

| 71. |

18 U.S.C. §1761(a). |

| 72. |

Stephen P. Garvey, "Freeing Prisoners' Labor," Stanford Law Review, vol. 50, no. 2 (January 1998), p. 373. |

| 73. |

Steven D. Levitt, "The Economics of Inmate Labor Participation," Paper presented at the National Symposium on the Economics of Inmate Labor Force Participation, May 1999, p. 5; Jeffery R. Kling and Alan B. Krueger, Costs, Benefits and Distributional Consequences of Inmate Labor, Princeton University, Industrial Relations Section, Working Paper #449, January 2001, p. 9. |

| 74. |

Richard Freeman, "Making the Most From Prison Labor," Paper presented at the National Symposium on the Economics of Inmate Labor Force Participation, May 1999, p. 3. |

| 75. |

In his paper presented at the National Symposium on the Economics of Inmate Labor Force Participation, economist Steven Levitt noted that researchers in 1998 estimated that inmate workers' per-hour output was $14.56 per hour. Adjusted for inflation, per-inmate output would have been $21.17 per hour in 2015. At the end of FY2015 there were 165,134 inmates held in federal prisons. Assuming that all of these inmates worked 40 hours per week each week of the year, their estimated output would have equaled approximately $7.272 billion. In comparison, the U.S. gross domestic product in 2015 was $17.947 trillion. |

| 76. |

Frederick W. Derrick, Charles E. Scott, and Thomas Hutson, "Prison Labor Effects on the Unskilled Labor Market," The American Economist, vol. 48, no. 2 (Fall 2004), pp. 74-81; Charles E. Scott, Nancy A. Williams, and Frederick W. Derrick, "Identifying Industries for Employment Development Using Input-Output Modeling: The Case of Prison Industry Employment," The American Economist, vol. 55, no. 2 (Fall 2010), pp. 142-152. |

| 77. |

"Freeing Prisoners' Labor," p. 378. |

| 78. |

Jeffery R. Kling and Alan B. Krueger, Costs, Benefits and Distributional Consequences of Inmate Labor, Princeton University, Industrial Relations Section, Working Paper #449, January 2001, p. 6. |

| 79. |

Ray Marshall, "The Economics of Inmate Labor Participation," Paper presented at the National Symposium on the Economics of Inmate Labor Force Participation, May 1999, p. 16. |

| 80. |

Ibid., p. 8. |

| 81. |

The inmate leasing system, which was the most popular in the South after the Civil War up until the early 1900s, provided inmate labor to private entities. The leasing entity was responsible for housing, feeding, and clothing the leased inmates. |

| 82. |

"Freeing Prisoners' Labor," p. 357. |

| 83. |

Ibid., p. 384. |

| 84. |

Ibid., pp. 384-385. |

| 85. |

Jeffery R. Kling and Alan B. Krueger, Costs, Benefits and Distributional Consequences of Inmate Labor, Princeton University, Industrial Relations Section, Working Paper #449, January 2001, p. 9. |

| 86. |

Ibid. |

| 87. |

Steven D. Levitt, "The Economics of Inmate Labor Participation," Paper presented at the National Symposium on the Economics of Inmate Labor Force Participation, May 1999, p. 7. |

| 88. |

P.L. 80-772, codified at 18 U.S.C. §4121 et seq. |

| 89. |

18 U.S.C. §4124(b). |

| 90. |

The FPI is determined to have a "significant market share" when the FPI's sales of a product within a Product Supply Code (PSC) constitute more than 5% of all sales to the DOD within that FSC. |

| 91. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Programs for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2012, and for Other Purposes, Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 2112, 112th Cong., 1st sess., November 14, 2011, H.Rept. 112-284 (Washington: GPO, 2011), p. 241. |

| 92. |

Ibid., p. 242. |

| 93. |

PIECP exempts certified correctional industries for current restrictions on the sale of prisoner-made goods in interstate commerce (18 U.S.C. §1761(a)). The program is intended to place inmates in a realistic work environment, pay them the prevailing local wage for similar work, promote rehabilitation, and enable them to acquire marketable skills to increase their potential for finding gainful employment after completing their terms of incarceration. DOJ OIG's audit of the FPI's efforts to create work opportunities, p. 22. |