Federal Health Centers: An Overview

The federal Health Center Program is authorized in Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) (42 U.S.C. §254b) and administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within the Department of Health and Human Services. The program awards grants to support outpatient primary care facilities that provide care to primarily low-income individuals or individuals located in areas with few health care providers.

Federal health centers are required to provide health care to all individuals, regardless of their ability to pay, and to be located in geographic areas with few health care providers. These requirements make health centers part of the health safety net—providers that serve the uninsured, the underserved, or those enrolled in Medicaid. Data compiled by HRSA demonstrate that health centers serve the intended safety net population, as the majority of patients are uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid. Some research also suggests that health centers are cost-effective; researchers have found that patients seen at health centers have lower health care costs than those served in other settings. In general, research has found that health centers, among other outcomes, improve health, reduce costs, and provide access to health care for populations that may otherwise not obtain health care.

Section 330 grants—funded by the Health Center Program’s appropriation—are only one funding source for federal health centers. The grants are estimated to cover only one-fifth of an average health center’s operating costs; however, individual health centers are eligible for grants or payments from a number of federal programs to supplement their budgets. These federal programs provide (1) incentives to recruit and retain providers; (2) access to the federally qualified health center (FQHC) designation, which entitles facilities to cost-related reimbursement rates from Medicare and Medicaid; (3) access to additional funding through federal programs that target populations generally served by health centers; and (4) in-kind support, such as access to drug discounts or federal coverage for medical malpractice claims.

This report provides an overview of the federal Health Center Program, including its statutory authority, program requirements, and appropriation levels. It then describes health centers in general, where they are located, their patient population, and outcomes associated with health center use. The report also describes federal programs available to assist health center operations, including the FQHC designation for Medicare and Medicaid payments. The report concludes with two appendixes that describe (1) FQHC payments for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries served at health centers and (2) programs that are similar to health centers but not authorized in Section 330 of the PHSA.

Federal Health Centers: An Overview

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- What Is the Federal Health Center Program?

- Statutory Authority and General Requirements

- Location Requirements

- Fee Schedule Requirements

- Medicaid Coordination and Reimbursement Requirements

- Governance Requirements

- Health Service Requirements

- Reporting and Quality Assurance Requirements

- Licensing and Accreditation Requirements

- Other Requirements

- Grants That Support Federal Health Centers

- Grant Eligibility and Awarding Criteria

- What Is the Health Center Program's Appropriation?

- What Are the Other Sources of Funding for the Health Center Program?

- What Are Health Centers?

- What Types of Health Centers Exist?

- Community Health Centers

- Health Centers for the Homeless

- Health Centers for Residents of Public Housing

- Migrant Health Centers

- Who Uses Health Centers?

- What Outcomes Are Associated with Health Center Use?

- Health Outcomes

- Cost Outcomes

- Access to Health Care

- Quality

- Which Federal Programs Are Available to Health Centers?

- National Health Service Corps Providers

- J-1 Visa Waivers

- Federally Qualified Health Center Designation

- 340B Drug Pricing Program

- Vaccines for Children Program

- Federal Tort Claims Act Coverage

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Grants

- Other Federal Grant Programs

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Examples of Services Provided and the Number of Patients Served by Health Centers (2015)

- Table 2. Health Center Grants Awarded (FY2016)

- Table 3. Health Center Appropriations and Sites, FY2005-FY2017

- Table 4. Health Center Program Revenue Sources (FY2016)

- Table 5. Comparison of Health Center Types

- Table 6. Health Centers' Patient Profiles, 2015

Summary

The federal Health Center Program is authorized in Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) (42 U.S.C. §254b) and administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within the Department of Health and Human Services. The program awards grants to support outpatient primary care facilities that provide care to primarily low-income individuals or individuals located in areas with few health care providers.

Federal health centers are required to provide health care to all individuals, regardless of their ability to pay, and to be located in geographic areas with few health care providers. These requirements make health centers part of the health safety net—providers that serve the uninsured, the underserved, or those enrolled in Medicaid. Data compiled by HRSA demonstrate that health centers serve the intended safety net population, as the majority of patients are uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid. Some research also suggests that health centers are cost-effective; researchers have found that patients seen at health centers have lower health care costs than those served in other settings. In general, research has found that health centers, among other outcomes, improve health, reduce costs, and provide access to health care for populations that may otherwise not obtain health care.

Section 330 grants—funded by the Health Center Program's appropriation—are only one funding source for federal health centers. The grants are estimated to cover only one-fifth of an average health center's operating costs; however, individual health centers are eligible for grants or payments from a number of federal programs to supplement their budgets. These federal programs provide (1) incentives to recruit and retain providers; (2) access to the federally qualified health center (FQHC) designation, which entitles facilities to cost-related reimbursement rates from Medicare and Medicaid; (3) access to additional funding through federal programs that target populations generally served by health centers; and (4) in-kind support, such as access to drug discounts or federal coverage for medical malpractice claims.

This report provides an overview of the federal Health Center Program, including its statutory authority, program requirements, and appropriation levels. It then describes health centers in general, where they are located, their patient population, and outcomes associated with health center use. The report also describes federal programs available to assist health center operations, including the FQHC designation for Medicare and Medicaid payments. The report concludes with two appendixes that describe (1) FQHC payments for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries served at health centers and (2) programs that are similar to health centers but not authorized in Section 330 of the PHSA.

Introduction

The federal Health Center Program awards grants to support health centers: outpatient primary care facilities that provide care to primarily low-income individuals. The program is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)—specifically by its Bureau of Primary Health Care—within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).1 The federal Health Center Program is authorized in Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA)2 and supports four types of health centers: (1) community health centers, (2) health centers for the homeless, (3) health centers for residents of public housing, and (4) migrant health centers.

According to HRSA data, over 10,000 unique health center sites (i.e., individual health center facility locations) exist.3 These sites provided care to 24.3 million people in 2015.4 The majority of health center sites are community health centers (CHCs). CHCs serve the general low-income or otherwise disadvantaged population, whereas the remaining three types of health centers provide care to more targeted low-income or otherwise disadvantaged populations (e.g., migrant farmworkers). Regardless of type, health centers are required by statute to provide health care to all individuals located in the health center's service area or individuals who are members of the health center's target population, regardless of their ability to pay. Health centers are also required to be located in geographic areas that have few health care providers or to provide care to populations that are medically underserved.5 These requirements make health centers part of the health safety net—providers that serve the uninsured, the underserved, or those enrolled in Medicaid.6 Data compiled by HRSA demonstrate that health centers primarily serve the intended safety net population, as the majority of patients are uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid.7

This report provides an overview of the federal Health Center Program, including its statutory authority, program requirements, and appropriation levels. The report then describes health centers in general, where they are located, their patient population, and outcomes associated with health center use. It also describes the federal programs available to assist health center operations, including the federally qualified health center (FQHC) designation for Medicare and Medicaid payments. Finally, the report has two appendixes that describe (1) FQHC payments for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries served at health centers and (2) programs that are similar to health centers but not authorized in Section 330 of the PHSA. Two companion reports also provide additional information about health center supplemental funding (CRS Report R43911, The Community Health Center Fund: In Brief) and about family planning services provided at health centers (CRS Report R44295, Factors Related to the Use of Planned Parenthood Affiliated Health Centers (PPAHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)).

What Is the Federal Health Center Program?

The federal Health Center Program awards grants to support outpatient primary care facilities that provide care to primarily low-income individuals. This section of the report describes the statutory authority for the federal Health Center Program, program requirements, types of grants awarded in support of the Health Center Program, the Health Center Program's appropriation, and other funding/revenue that health centers receive.

Statutory Authority and General Requirements8

Section 330 of the PHSA authorizes grants for health centers and includes the requirements that entities must meet to receive a health center grant. Section 330 requires health centers to provide services to the entire population located in the health center's service area or individuals who are members of the health center's target population, regardless of individuals' ability to pay. Health centers are also required to document the health needs of the residents in their service area and to update their service area if upon evaluation they determine that changes are needed. Among other program requirements, health center grantees must (1) be located in specific geographic areas, (2) have an established fee schedule that meets certain requirements, (3) collect reimbursements for individuals enrolled in public or private insurance programs, (4) have appropriate governance, (5) offer specific health services, (6) meet certain reporting and quality assurance requirements, and (7) license providers and seek accreditation. These requirements apply to activities that are within the scope of PHSA Section 330 grant, but do not apply to other activities.9 HRSA is required to determine whether health center grantees meet these requirements. In 2012, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) raised concerns that the agency may not be providing sufficient oversight of the program and that some health centers may not be meeting these requirements.10 In response to this GAO report, HRSA implemented new procedures to increase the agency's oversight of the program and to provide training to health centers to better comply with the program's requirements.11 This CRS report does not evaluate whether health centers meet program requirements; rather, it describes the program's requirements.

Location Requirements

PHSA Section 330 requires that a health center be located in an area designated as medically underserved or as serving a population designated as "Medically Underserved" (see text box).12

|

Medically Underserved Areas/Populations Medically Underserved Areas (MUA): Areas of varying size—whole counties, groups of contiguous counties, civil divisions, or a group of urban census tracts—where residents have a shortage of health care services. Medically Underserved Populations (MUPs): Groups that face economic, cultural, or linguistic barriers to accessing health care. Source: HRSA, Bureau of Primary Care, Shortage Designations, at http://www.hrsa.gov/shortage/index.html. |

Fee Schedule Requirements

Health centers must establish their own fee schedules that are consistent with prevailing local rates for health services and are designed to cover the reasonable costs that the health center incurs in providing services.13 This fee schedule is used by all payers. As part of the requirement to provide services to all individuals regardless of their ability to pay, the health center is required to discount the fee schedule to reduce or waive the amount that the patient pays based on the patient's ability to pay as determined by a patient's income relative to the federal poverty level14 and the patient's family size—no other criteria may be considered.15 This is referred to as sliding-scale fees. The statute requires that individuals whose income is above 200% of the federal poverty level pay full charges, while individuals whose incomes are at, or below, 100% of the federal poverty level pay only nominal fees.16 Individuals with insurance coverage may also be eligible for discounted services if the copayment charged by the individual's health insurance plan would be greater than the amount that the individual would pay for the service under the discounted fee schedule. In this case, the individual would pay only the discounted fee schedule amount and not the full copayment amount as long as this is not precluded by the insurance plan's contract terms.17 The fee schedule is intended to have patients be monetarily invested in their care but is also supposed to minimize cost-related barriers to care.18

Medicaid Coordination and Reimbursement Requirements

Health centers are required to enroll as providers in state Medicaid and State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) plans to provide services to beneficiaries enrolled in these programs. They are also required to seek appropriate reimbursement for their costs from third-party payers such as private insurance plans, Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP.19 Health centers are further required to have systems to obtain reimbursements, including those used for billing, credit, and collections. These collections provide nearly two-thirds (62.5%) of the Health Center Program's revenue in FY2015 (see Table 4).

Although health centers collect reimbursements, some data suggest that these reimbursements may not be sufficient to cover the costs that health centers accrue when providing care. For example, the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC)—the main advocacy group for health centers at the national level—reported in 2016 that the amount collected from Medicaid covered 82% of the costs incurred when providing care to a Medicaid beneficiary.20

In a 2010, GAO reported that Medicare reimbursements were also below the amount incurred per patient. In nearly 70% of visits that GAO examined in 2007, the health center's costs exceeded Medicare's upper payment limit (i.e., the maximum amount that Medicare would pay).21 Since GAO's report, the Medicare payment methodology used for health centers has changed, resulting in increased payments. It is not clear whether the new payment rate fully pays the costs incurred.

Governance Requirements

Health centers are required to have governing boards in which their patients form majorities. For each health center's board, such members are selected to reflect the demographic characteristics of the population served by the health center. Board members are not permitted to be health center employees or their relatives. In addition, nonpatient board members must be representative of the community that is served by the health center, have expertise in fields relevant to health center operations, and no more than half of the nonpatient representatives may derive more than 10% of their income from the health care industry.22

The governing board must approve general health center policies, including the center's budget, operating hours, management, and fee schedule. The governing board is required to meet monthly, and it must approve the center's director and must approve grant applications submitted by the center.23

Health Service Requirements

Health centers are required to provide primary health services and preventive and emergency health services.24 Primary health services are those provided by physicians25 or physician extenders (physicians' assistants, nurse clinicians, and nurse practitioners) to diagnose, treat, or refer patients. Primary health services include relevant diagnostic laboratory and radiology services. Preventive health services include well-child care, prenatal and postpartum care, immunization, family planning, health education, and preventive dental care.26 Emergency health services refer to the requirement that health centers have defined arrangements with outside providers for emergent cases that the center is not equipped to treat and for after-hours care. Health centers are also required to provide additional health services that are not primary health services but that are necessary to meet the health needs of the service population. This includes, but is not limited to, behavioral health services and environmental health services.27

Health center physicians must also have admitting privileges at one or more hospitals located near the health center. This requirement is intended to ensure care continuity for hospitalized health center patients. In instances where a health center physician does not have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, the health center is required to establish other arrangements to ensure care continuity.

Health centers are also required to provide enabling services such as translation services, health education, and transportation for individuals residing in a center's service area who have difficulty accessing the center. All services that health centers provide must be available to all patients at the center (i.e., regardless of patient payment source) and must be available (either directly or under a referral arrangement) to patients at all health center service sites. Table 1 identifies some specific services tracked in the Uniform Data System (UDS) 2015, the HRSA-required health center grantee reporting system.

|

Service Provided |

Number of Patients Receiving Service Typea |

|

Medical Services |

20,616,149 |

|

Dental Services |

5,192,846 |

|

Enabling Servicesb |

2,388,722 |

|

Mental Health Services |

1,491,926 |

|

Substance Abuse Services |

117,043 |

|

Total Patients |

24,295,946 |

Source: HRSA, Uniform Data System (UDS) Report, UDS, National Rollup Report, 2015, at http://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx; hereinafter, 2015 UDS Report.

a. An individual patient may receive more than one type of service in a given year.

b. For example, translation or transportation to the health center.

Reporting and Quality Assurance Requirements

Health centers are required to report to HRSA certain information and to have quality improvement and assurance plans in place. First, health centers are required to report patient demographics, services provided, staffing information, utilization rates, costs, and revenue to HRSA's UDS. Second, within the UDS, health centers must report on certain clinical outcomes to assess quality.28 These outcomes are similar to those examined in other health care settings. They include, for example, the percentage of children who received recommended immunizations by the age of two, the percentage of women who were screened for cervical cancer, and the percentage of patients whose body mass index was assessed and who were referred to appropriate services if found to be obese.29 Finally, health centers are required to have quality improvement systems in place that include clinical services, management, and patient confidentiality assurances. To meet this requirement, health centers must have a clinical director who reports on quality improvement and assurance activities. The clinical director conducts periodic assessments of the health center's services to evaluate the quality and appropriateness of services provided. HHS has also awarded grants to health centers to implement quality initiatives such as care coordination through mechanisms like medical homes.30

Licensing and Accreditation Requirements

Health center providers must be properly licensed in the state in which they practice. As noted previously, health center physicians must have admitting privileges at hospitals where health center patients are likely to be referred (see "Health Service Requirements"). Furthermore, providers must maintain proper credentials during their health center employment.

Although health centers are not required to be accredited by a national accreditation agency, HRSA encourages them to seek accreditation. Specifically, HRSA encourages health centers to seek accreditation from either the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAHC) or The Joint Commission (TJC). HRSA pays some of the costs of seeking and maintaining accreditation from one of these two accrediting entities.31 HRSA also encourages health centers to be recognized as Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH), which is intended to assess the health center's provision of patient-centered care, which includes meeting national standards for primary care and emphases on care coordination and quality improvement.32

Other Requirements

HRSA requires that health centers maintain appropriate accounting and internal control systems in accordance with government accounting principles. Health centers are required to have annual independent financial audits performed in accordance with federal auditing requirements and to submit corrective action plans that address all findings, and questioned costs, among other concerns, identified in the required audits.33 In addition to specific PHSA Section 330 requirements, health center grantees are required to comply with standard government grant requirements.34

Grants That Support Federal Health Centers

HRSA awards a number of grants to support health centers, including the following:

- New Access Point (NAP) grants permit existing grantees to establish new sites or new grantees to establish new health centers.

- Service Expansion grants are for health centers to expand the number of patients they serve or to provide additional types of services.

- Grants to improve quality or infrastructure of health centers. These grants are used to support activities that support health center quality improvement efforts, including meeting the requirements to become an accredited Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH).35 Grants also include Health Center Control Networks, which are used to support electronic health record use at health centers.36

- Grants for Capital Development for the construction and renovation of health centers.37

- Planning Grants are available to entities that are not health centers, to plan and develop health centers. Funds may be used for assessing the health needs of the proposed service population and developing linkages with the community and with health providers in the proposed service area.

Grant Eligibility and Awarding Criteria

Public and nonprofit entities are eligible to apply for Section 330 grants to operate health centers.38 The majority of health center grantees operate facilities at more than one site, and some operate more than one type of health center.39 Grants are awarded competitively based on an assessment of the need for services in a given area and the merit of the application submitted. Grants may also be awarded based on certain funding priorities, such as creating a rural-urban balance in health center locations.40 HRSA must allocate certain percentages of the Health Center Program's budget to grants that support health centers serving special populations (e.g., migrant workers, the homeless, residents of public housing). Specifically, the Health Center Program's budget must be allocated as follows:

- at least 8.6% for grants to centers serving migrant or seasonal farmworkers,

- at least 8.7% for grants to centers serving homeless individuals, and

- at least 1.2% for grants to centers serving residents of public housing.41

A health center may be of more than one type—for example, a community health center may also operate a migrant health center, but it must devote at least 25% of its HRSA grant funding to migrants to be considered to be serving a "special population." In addition to these funding requirements, HRSA is required to give special consideration, within the competitive grant process, to applications for centers that would serve sparsely populated areas, defined as areas with seven or fewer residents per square mile.42 GAO found that in order to ensure that these percentages are met, HRSA may adjust funding criteria, thereby funding some applications that may not have scored as high in the competitive process.43

Grant recipients are not required to provide matching funds, but are required to use grant funds to supplement and not supplant funding that had been available prior to the grant. Grant amounts are based on the cost of proposed grant activity (see Table 2). An entity may receive funding for multiyear projects, but amounts awarded in subsequent years are contingent on (1) congressional appropriations and (2) the entity's compliance with applicable statutory, regulatory, and reporting requirements.44 At the end of the application period (generally three years), health centers are required to compete for continued funding through what is called a Service Area Competition, which requires the health center to demonstrate that it is meeting the needs of the area it is serving.45

|

Grants |

FY2016 |

|

Total Number of Grants |

1,383 |

|

Average Awarded Amount |

$3.0 million |

|

Range of Awarded Amounts |

$200,000-$18.0 million |

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, FY2017, Rockville, MD, p. 63.

What Is the Health Center Program's Appropriation?

The Health Center Program's appropriation has increased over the past decade, resulting in the establishment of more centers and the ability to serve more patients. From FY2005 through FY2016, the program's funding level increased by 200%, from $1.7 billion to $5.1 billion. Over this same time period, the number of health center sites also increased. Beginning in 2002, the George W. Bush Administration began a multiyear effort to expand the Health Center Program by providing funding for new or expanded health centers for 1,200 communities.46

The program's expansion continued during the Obama Administration. In FY2009, the Health Center Program received $2 billion under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA, P.L. 111-5). Specifically, ARRA provided $500 million for new sites and expanded services at existing sites. It also provided $1.5 billion for construction, renovation, equipment, and health information technology. The program's expansion continued under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended), which permanently authorized the Health Center Program; appropriated a total of $1.5 billion for health center construction and repair; and created the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF), which included a total of $9.5 billion for health center operations to be appropriated in FY2011 through FY2015.47 The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA, P.L. 114-10) extended the CHCF through FY2017, providing a total of $7.2 billion to support health center operations.48

Although the Health Center Program's funding has increased because of the CHCF, this increase was smaller than anticipated when the ACA was enacted in 2010 because the CHCF has been used to offset reductions in discretionary appropriations to the Health Center Program.49 Although the program's funding level has nearly doubled since FY2005, the additional appropriated funds have generally been used to expand the number of centers—which increased by 154%50—while funding awarded to individual centers increased less rapidly over the same time period.51

Table 3 presents the Health Center Program's appropriations from FY2005 through FY2017. The table also includes amounts appropriated under ARRA and the ACA and the number of sites in each fiscal year.

|

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

FY2017 |

||||||||||||||

|

Dollars in Millions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

ACA CHCFb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Total Funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Number of Sites |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Approx. number of sites |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

Source: Compiled by CRS from HRSA budget documents.

Note: Appropriated amounts include federal tort claims funds.

a. Reflects amount reduced under sequestration as required in the Budget Control Act.

b. Community Health Center Fund (CHCF) refers to amounts transferred from the CHCF that was created in Section 10503 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended).

c. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA, P.L. 114-10) extended the CHCF and provided $3.6 billion for each of FY2016 and FY2017.

d. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA, P.L. 111-5) appropriated $2 billion to support the program in FY2009.

What Are the Other Sources of Funding for the Health Center Program?

In addition to Section 330 grants, health centers receive health care operational revenue from reimbursements and from other sources (e.g., state and local grants). The relative contribution of each of these sources to an individual health center's budget varies by center. For health centers located in a state that expanded its Medicaid program under ACA, Medicaid comprises approximately half of health center revenue. In contrast, Medicaid is less than one-third of revenue for health centers in states that did not expand Medicaid.52

HRSA also compiles data for the overall Health Center Program, which provides information on the average health center revenue sources. Table 4 presents data for FY2016, the most recent year of data available. Medicaid is the largest source of health center revenue (42.2%) in FY2016; this was followed by Section 330 grants (21.7%), state, local, and private funding (13.9%), and reimbursements from private insurance (9.0%).53

|

Dollars |

Percent of Program Revenue |

|||||

|

Section 330 Authorized Grants |

||||||

|

Section 330 Grants |

|

|

||||

|

Subtotal (Section 330 authorized grants) |

|

|

||||

|

Reimbursements |

||||||

|

Medicaid |

9.870.0 |

|

||||

|

CHIP |

|

|

||||

|

Medicare |

|

|

||||

|

Other third party payers (e.g., private insurance) |

|

|

||||

|

Patient Feesa |

|

|

||||

|

Subtotal (Reimbursements) |

|

|

||||

|

Other Federal Grants |

||||||

|

Other Federal Grants |

|

|

||||

|

Subtotal (Other Federal Grants) |

|

|

||||

|

State, Local, and Private Grants and Contracts |

||||||

|

State, Local, Other |

|

|

||||

|

Subtotal (State, Local, and Private Grants and Contracts) |

|

|

||||

|

Total (all sources) |

|

|

||||

What Are Health Centers?

This section describes health center facilities funded under the Health Center Program appropriation. It includes a discussion of the four types of health centers funded and compares the services offered and populations served by each center type. The section also describes where health centers are located and outcomes associated with health center use.54

What Types of Health Centers Exist?

Four types of health centers exist: (1) community health centers, (2) health centers for the homeless, (3) health centers for residents of public housing, and (4) migrant health centers. The majority of health centers are community health centers (CHCs), which serve a generally underserved population. The other three types of health centers serve more targeted populations. Each type of health center is described below, along with the population targeted by these centers and the specific services that each type of center must provide.55

Community Health Centers

More than three-quarters of health centers are CHCs because these facilities serve the general population with limited access to health care. CHCs are required to serve all residents who reside in the CHC service area (also known as the catchment area). CHCs are required to provide "primary health services" (see the "Health Service Requirements" section). CHC-required services are the baseline services that all types of health centers are required to provide. The other three types of health centers may be required to provide certain supplemental services that aim to meet the specific needs of the population they serve. The majority of Health Center Program grant funding is allocated to support CHCs. By statute, 18.5% of the budget must be reserved for grants that support health centers serving special populations; this means that a maximum of 81.5% of the Health Center Program budget may be used to support CHCs.56

Health Centers for the Homeless

Health centers for the homeless (HCHs) provide services to homeless individuals—the only federal health program that targets this generally uninsured population.57 Section 330 defines homeless individuals as those who lack permanent housing or live in temporary facilities or transitional housing.58 In addition to the services required of all health centers, HCHs are required to provide substance abuse services and supportive services that aim to meet the health needs of the homeless population. HCHs may also provide mobile services and aim to connect homeless individuals with supportive services, such as emergency shelter, transitional housing, job training, education, and some permanent housing. Grants are also available for innovative programs that provide outreach and comprehensive primary health services to homeless children and children at risk of homelessness. By statute, HRSA must allocate at least 8.7% of the Health Center Program budget to support these centers.59

Health Centers for Residents of Public Housing

Health centers for residents of public housing60 are located in public housing facilities and aim to provide primary care to individuals who reside there. These centers provide the services required of CHCs and are not required to provide specific supplemental services. These centers were authorized in 1990 because of congressional concern that public housing residents had worse health than similar (by demographic and economic status) individuals who did not reside in public housing.61 By statute, HRSA must allocate at least 1.2% of the Health Center Program budget to support these centers.62

Migrant Health Centers

Migrant health centers provide care to migrant farmworkers (persons whose principal employment is in agriculture on a seasonal basis and who establish temporary residences for work purposes) and seasonal farmworkers (persons whose principal employment is in agriculture on a seasonal basis, but do not migrate for this work).63 HRSA estimates that it provides care to more than one-quarter of all migrant and seasonal farmworkers.64 In addition to the general health center requirements, migrant health centers are required to provide certain services specific to their service population's health needs, such as supportive services, environmental health services, accident prevention, and prevention and treatment of health conditions related to pesticide exposure.65 Migrant health centers may be exempt from providing all required services, and may operate only during certain periods of the year. By statute, HRSA must allocate at least 8.6% of the Health Center Program budget to support these centers.66

Comparison of Health Center Types

Table 5 describes the four types of health centers, their target populations, the additional services they are required to provide, and the number of patients seen in 2015. Additional services are assessed relative to the CHC service requirements (see "Health Service Requirements").

|

Health Center Type |

Target Population |

Additional Requirementsa |

Number of Patients Seenb |

|

Community Health Centers |

All individuals who live in service area |

Not Applicable. |

22,085,358c |

|

Health Centers For the Homeless |

Homeless individuals |

Prevention and treatment services for substance abuse. |

890,283 |

|

Health Centers for Residents of Public Housing |

Individuals who reside in or near public housing |

Must consult with public housing residents prior to applying for a grant. |

487,034 |

|

Migrant Health Centers |

Migrant, agricultural workers |

Environmental health services including sanitation services; and services related to the prevention and treatment of pesticide exposure. |

833,271 |

Sources: HRSA's Data Warehouse at http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/sitesdetail.aspx and HRSA, UDS, National Rollup Report 2015.

a. CHC-required services are considered the baseline; therefore, additional requirements are assessed relative to the requirements for CHCs.

b. Refers to the 2015 patient population.

c. HRSA does not report number of patients seen at CHCs; this number was estimated by subtracting the number seen at the three other types of health centers from the total number of patients seen (24,295,946).

Who Uses Health Centers?

According to HRSA, health centers served 24.3 million patients in 2015. These patients were generally socioeconomically disadvantaged and uninsured or underinsured.67 The majority of health center patients have incomes at or below the federal poverty level. Nearly a quarter of patients are treated in a language other than English, and the majority of health center patients are racial or ethnic minorities. In 2015, close to two-thirds of health center patients were identified as a racial and/or ethnic minority. This rate is nearly double the proportion of racial/ethnic minorities in the overall U.S. population. Table 6 presents some demographic characteristics of the health center patient population in 2015, including age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status.

|

Selected Demographic Characteristics of Patients |

Percentage of Patients Served |

|

Income at or below 200% federal poverty level |

62.4% |

|

Enrolled in Medicaid |

48.9% |

|

Uninsured |

24.4% |

|

Racial and/or Ethnic Minority |

62.4% |

|

Best Served in Another Language |

22.8% |

|

Pediatric (Ages 0-17) |

31.2% |

|

Age 65 and older |

7.9% |

Source: 2015 UDS Report.

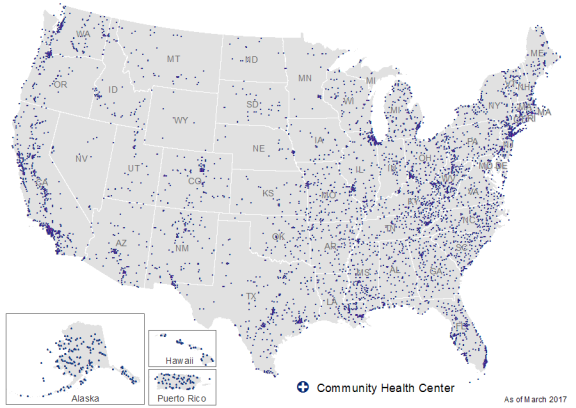

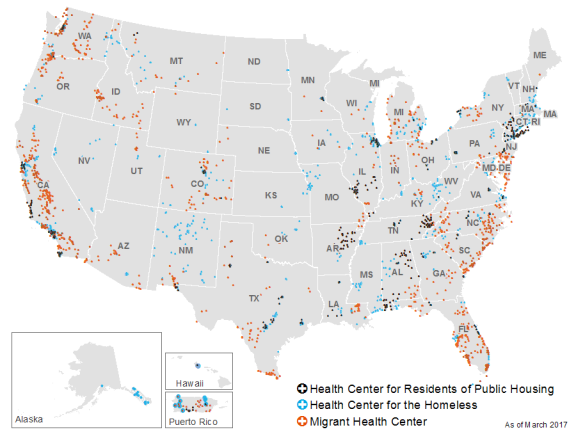

Figure 1 shows the locations of community health center grantees funded with PHSA Section 330 grants and Figure 2 shows the locations of the three other types of health center grantees. Figure 1 shows that community health centers are distributed throughout the country. Figure 1, compared with Figure 2, also shows that community health centers are the most numerous type of sites and that a number of health centers receive grants to operate multiple health center types in the same geographic area.

|

Figure 1. Community Health Center Grantee Sites (Data as of March 2017) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of HRSA grantee data. |

|

Figure 2. Locations of Health Centers for Residents of Public Housing, Health Centers for the Homeless and Migrant Health Centers (Data as of March 2017) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of HRSA grantee data. |

What Outcomes Are Associated with Health Center Use?

Researchers have found that access to health centers can improve health outcomes and reduce costs for the populations and areas they serve. Research has also found that health centers may increase access to health care for generally underserved populations, such as those enrolled in Medicaid, and racial and ethnic minorities. This section briefly summarizes the research on the effects of health centers on health, costs, access, and quality.

Health Outcomes

Health centers focus on preventive care and attempt to manage patients' chronic conditions. This focus may improve health by preventing disease and disease-related complications.68 Research has found that health center patients are more likely to receive preventive health services—including pap tests and influenza vaccinations—and more likely to receive preventive screenings—including mammograms and colonoscopies—when compared to non-health center patients of similar socioeconomic status.69

Finally, health centers aim to increase prenatal care use in low-income pregnant women to reduce outcomes associated with infant mortality such as low birth weight. HRSA has found that health centers have made progress in this effort: an increasing number of health center patients initiate prenatal care in their first trimester, resulting in fewer health center patients—when compared to the national average—having low-birth-weight babies, which is a major cause of infant death.70

Cost Outcomes

Researchers have found that health centers may lower health care costs by reducing more costly emergency department visits. GAO found that, on average, treatment at health centers is nearly one-seventh the cost of treatment of the same condition in an emergency department.71 Given these differences in cost, health centers that successfully reduce emergency department use may reduce overall health care costs. One study found that counties with health centers have lower emergency room use and that individuals who live near health centers use emergency rooms less.72 In addition, GAO found that health centers attempt to lower emergency department use in the communities in which they operate by educating patients about services offered at health centers and by offering same-day and after-hours appointments.73

Health centers may also reduce overall health care costs by preventing unnecessary hospitalizations. A number of studies have examined "ambulatory care sensitive conditions," which are conditions that potentially can be treated in an outpatient setting, thus avoiding a hospitalization (e.g., asthma or seizures). These studies have found that in communities with health centers, individuals with these conditions were less likely to be hospitalized.74 Health center patients enrolled in Medicaid were also less likely to be hospitalized and less likely to have an emergency room visit, relative to Medicaid beneficiaries who did not use health centers.75

Recent studies have also compared total spending associated with health center patients enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid with spending for Medicare and Medicaid recipients who get their primary care outside of health centers. For Medicare and Medicaid recipients, health center patients were associated with lower spending. For Medicare patients, the median annual costs per Medicare beneficiary were 10% lower for health center patients when compared to similar non-health center patients.76 For Medicaid beneficiaries, costs were 24% lower overall and there were lower costs for specialty care and inpatient care.77 These were also 25% fewer hospital admissions.78

Researchers who looked at the Health Center Program's use of medical homes to coordinate patient care found that patients who received the majority of their care at health centers that have implemented medical homes have lower medical costs (41% lower on average) than those who receive the majority of their care through another source.79 Another study that examined national survey data found that health centers (whether or not they employed the medical home model) reduced costs by 24%,80 whereas a North Carolina study found that health center users' annual health care spending was 62% less than similar patients (matched by demographic characteristics and health status) who were served in other outpatient settings.81 Regardless of the magnitude of the difference, there appears to be consensus that health centers provide less costly health care than other outpatient settings.82

The reasons that health centers provide less costly care are debated. The authors of the North Carolina study suggest that health centers provide health care at a lower cost because they can offer discounted services through federal programs (see "Which Federal Programs Are Available to Health Centers?"). They also suggest that health centers may provide less costly overall care because their providers work on a salaried basis, and so do not have financial incentives to order additional tests or procedures. This may not be the case in other outpatient settings because providers generally work under a fee-for-service model, where they may receive additional remuneration for providing more services.83 Other studies note that differences in the cost of services (i.e., the fee for a particular procedure or visit) do not explain the difference because health centers are paid the FQHC rate, which should likely be comparable to, or higher than, the rates reimbursed in other outpatient settings. Given differing explanations of how health centers may reduce health care costs, the researchers state that health center costs may be lower because they avert more costly emergency room visits, specialty care, or hospital stays.84

Access to Health Care

Health centers aim to provide care to underserved populations and, in doing so, may increase health care access. By definition, health centers are located in areas with few providers, including rural and inner city areas. These locations may provide access for populations that are otherwise underserved, for example, because of geography or income. Health centers also serve a more diverse population than do office-based physicians; results from one study indicate health center patients were more likely to be Hispanic or African American.85 Health centers may also increase access for specific racial and ethnic groups. For example, one study found that health centers increase health care access for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders.86 Some research has suggested that health centers may reduce health disparities because they provide care to a population that might otherwise have difficultly accessing health care.87

Relative to other providers (such as office-based physicians), health centers are more likely to accept new patients and are required to accept patients who are unable to pay for services (i.e., charity patients).88 Health center patients are also more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP. As noted, health centers are required to coordinate with Medicaid and CHIP plans and are required to accept all patients, regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. As such, health centers are a common source of care for Medicaid patients. Recent research found that Medicaid patients were more likely to obtain an appointment at a health center than they were at private primary care practice.89 Researchers have also found that health center presence in a geographic area increases the likelihood that low-income adults have seen a doctor in the past year (whether at a health center or not).90

Quality

Research evaluations have compared the quality of care provided at health centers to that provided in physician offices. One study examined 18 quality measures and found that health centers performed better on 6 measures (related to treatment for congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, depression, and screening), no differently on 11 measures, and worse on 2 measures (related to diet counseling for at risk adolescents). This was observed despite the study's finding that health centers treat a population with higher rates of comorbidities (i.e., they have multiple health conditions), which may make it more difficult to provide care that meets the criteria required by the quality measures examined.91

Researchers have also examined the ability of health centers to manage chronic conditions and have found that health centers provide quality care when it comes to managing conditions such as diabetes and hypertension92 and are successful in managing and reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to asthma.93

Another study compared the quality of health center care to that of Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) on selected quality measures, including diabetes and blood pressure control.94 The study found that there were two groups of health centers: those that exceeded Medicaid MCOs in the selected quality measures (called "high performing health centers") and those that were below the Medicaid MCOs (called "low performing health centers"). The researchers found that more health centers were considered "high performing" (12%) and that relatively few health centers (4%) were considered "low performing." The authors observed that there were differences in the population served by high- and low-performing health centers and that it is possible that these population differences resulted in the quality differences observed. Specifically, "low performing health centers" were more likely to serve individuals who were uninsured or homeless and had less revenue from Medicaid. There were also geographic differences in the quality of health centers, with "high performing" health centers located mostly in California, New York, and Massachusetts and with "low performing health centers" more often located in southern states.

Which Federal Programs Are Available to Health Centers?

Section 330 grants, on average, cover approximately one-fifth of the cost of operating a health center;95 the federal government provides other assistance—for example, provider recruitment and financial assistance—that may support individual health center operations.96 To assist with operations, health centers may employ members of the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), a program that provides scholarships and loan repayments in exchange for a period of service at a health center.97 Health centers pay the salary of these personnel, but NHSC benefits may assist with recruitment and retention.

The federal government also provides financial support to health centers. For example, it designates health centers as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), thereby making these facilities eligible for cost-based Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates.98 Medicaid is the largest source of reimbursement, providing more than 40% of all revenue for the Health Center Program (see Table 4). The amount received by an individual health center varies by the percentage of the patient population enrolled in Medicaid; however, NACHC estimates that the average health center receives 44% of its revenue from Medicaid reimbursements.99 Health centers are also eligible for discounted prescription drugs and vaccines, and may receive additional support from grants and loans offered through other federal programs.

National Health Service Corps Providers

Health centers, which are located in medically underserved areas, are also automatically designated as health professional shortage areas (HPSAs)100 and are therefore eligible for National Health Service Corps (NHSC) providers. The NHSC provides scholarships or loan repayments to health professionals working at specific facilities in HPSAs. About half of Corps members serve in health centers,101 making the program an important mechanism for health centers to recruit providers. In addition to the NHSC, some states may operate loan repayment programs for health professionals providing care in state-designated shortage areas.102

J-1 Visa Waivers

Health centers may also be able to obtain providers temporarily through special waivers for J-1 visa physicians. In general, foreign medical graduates who entered the country on a J-1 student visa must return to their home country for two years after they have completed their medical training (medical school and residency). J-1 visa waivers permit the two-year foreign residency period to be waived if the J-1 visa holder practices primary care in a HPSA.103 Because health centers are designated as HPSAs, a number of centers may rely on this program to recruit physicians.104

Federally Qualified Health Center Designation105

Health centers are eligible to be designated as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs),106 but must enroll as a provider in the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs to receive cost-based107 reimbursement rates for services provided to patients enrolled in these programs.108 This higher reimbursement rate is an important source of health center revenue because more than one-third of the patients seen at health centers are enrolled in Medicaid.109 Specific FQHC Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement methodology, including recent payment changes, are described in Appendix B.

340B Drug Pricing Program

Federal health centers are eligible to participate in the 340B Drug Pricing program, which requires drug manufacturers to provide drug discounts or rebates to 340B eligible facilities. The program provides drugs at discount prices—ranging from 13% to 23% below average manufacturer price, depending on the type of drug.110 HRSA reports that in FY2014, 340B-eligible facilities saved $4.5 billion because of the program.111<del> </del>

Vaccines for Children Program112

Health centers are eligible to participate in the Vaccines for Children Program (VFC), which provides vaccines for low-income children who may not be vaccinated because of costs. The program is administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and partially funded by Medicaid. The CDC buys the vaccines and distributes them to health departments that, in turn, distribute them to VFC providers including health centers. VFC provides free vaccines to Medicaid-enrolled children and VFC-eligible children (those who are uninsured, underinsured,113 or those who are American Indian or Alaska Native). Health centers are a VFC-eligible provider, and provide vaccinations as part of their mission to provide primary and preventive services. The VFC program enables health centers to provide these vaccines at a lower cost to the patients and to the health center.

Federal Tort Claims Act Coverage

Health center employees and board members do not need to carry medical malpractice coverage because they are covered under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA).114 Under the FTCA, health center employees and contractors are deemed to be federal employees and cannot be sued for medical malpractice for care they provided that was within the scope of their health center employment. In 2016, the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Reform Act of 2016115 made volunteers at health centers eligible for FTCA coverage.116

According to HRSA, in FY2015, 111 claims were paid for health center employees through the FTCA program totaling $93.8 million.117 This program provides financial support to health centers because otherwise they would have to pay for malpractice coverage and would be responsible for payment and rate increases that may accompany claims made against health center providers.118

Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Grants119

Health centers are eligible to receive grants authorized under parts A and C of the Ryan White AIDS program. Part A authorizes grants for primary care, access to antiretroviral therapies, and other health and supportive services. These grants are awarded to certain metropolitan areas and are used to provide care for low-income, underserved, uninsured, or underinsured individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Part C grant funds are awarded to entities to provide medical services such as testing, referrals, and clinical and diagnostic services to underserved and uninsured people living with HIV/AIDS in rural and frontier communities.

Other Federal Grant Programs120

Health centers are eligible to apply for a number of federally funded grant programs, including programs that seek to improve rural health and health care,121 increase mental health and substance abuse services availability,122 provide services to high-risk pregnant women and their infants,123 increase health professional training at health centers,124 and increase access to family planning services for low-income families.125 The majority of these programs are funded by discretionary appropriations and are competitive grant programs authorized in the PHSA. Programs specific to rural areas may also be administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and are authorized in other acts. For example, health centers in rural areas may be eligible for USDA programs that may assist facilities with acquiring equipment or space through loan guarantees and with acquiring broadband access.126 Health centers may also use General Services Administration resources to acquire real estate and dispose of property127 and may use the Department of Housing and Urban Development's insurance program to finance facility repair and improvement.128

Appendix A. Other Federal Programs That May Provide Primary Care to the Underserved

The federal government supports a number of facilities that provide primary care to low-income or otherwise medically underserved populations that are similar to health centers, but are not authorized in PHSA Section 330. For example, the ACA authorized funding for school-based health centers and nurse-managed health clinics. Both of these facilities serve underserved populations but have different requirements than facilities authorized in PHSA Section 330. The federal government also provides support for facilities that provide care to targeted populations such as American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians; facilities located in rural areas; facilities that provide mental health services; and facilities that provide free care. This appendix describes these types of facilities, their authorization, and program requirements.

School-Based Health Centers

School-based health centers (SBHCs) are facilities located on or near school grounds that provide age-appropriate comprehensive primary health care services to students regardless of their ability to pay.129 SBHCs may be located at public, private, charter, or parochial schools and must be open, at a minimum, during school hours.130 Prior to the ACA, HRSA funded SBHCs through its Section 330 appropriation.131 The ACA authorized separate SBHC grants in Section 339Z-1 of the PHSA and appropriated $200 million ($50 million annually) from FY2010 to FY2013 to support grants for SBHC construction and renovation.132 Although the ACA authorized grants for SBHC operation, funding has not been appropriated for these grants.133 Despite the lack of an explicit SBHC operating grant program, some Section 330 grantees may operate SBHCs.

Nurse-Managed Health Clinics

Nurse-managed health clinics (NMHCs) provide comprehensive primary care and wellness services to underserved populations at centers where nurses provide the majority of health services. NMHCs are required to serve the entire population in the area in which they are located and must have an advisory committee similar to those required for Section 330 health centers. NHMCs provide wellness services, prenatal care, disease prevention, management of chronic conditions (e.g., asthma, hypertension, and diabetes), and health education. Some also provide dental and mental health services.134 ACA authorized grants to support NMHCs in PHSA Section 330A-1. In FY2010, HHS awarded $15 million to provide three years of support for 10 NHMCs.135 Grantees were required to submit a sustainability plan for operation after the federal grant period was completed in 2013.136 No funding has been awarded since FY2010.

Community Mental Health Centers

Community mental health centers (CMHCs)137 are licensed facilities that provide mental health services. These facilities are required to provide mental health services tailored to the needs of children and adults (including the elderly) who have a serious mental illness. These facilities are also required to provide services to individuals who have been discharged from inpatient treatment at a mental health facility. Among the required services, CMHCs must provide emergency services, day treatment or other partial hospitalization services, psychosocial rehabilitation services, and screening for admission into state mental health facilities. The ACA required—effective April 1, 2011—that CMHCs provide less than 40% of their services to Medicare beneficiaries.138

CMHCs receive funding from states through Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) block grants. These include SAMHSA substance abuse prevention and treatment block grants and community mental health services block grants.139 In addition, CMHCs are eligible for HHS grants awarded through the Social Service Block Grant.140 CMHCs also receive reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid for covered services provided to beneficiaries enrolled in these programs.

Native Hawaiian Health Care

The federal government supports the Native Hawaiian Health Care System (NHHCS), which is composed of five grantees and the Papa Ola Lokahi, a consortium of health care organizations that provide primary care, health promotion, and disease prevention services to Native Hawaiians. This population often faces cultural, financial, and geographic barriers to accessing health care services. The NHHCS was originally authorized under the Native Hawaiian Health Care Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-579), which was reauthorized through FY2019 in the ACA.141 The NHHCS is not a grant program under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, but the system receives funding through the health center appropriation.142 In 2014, NHHCS provided medical and enabling services, such as transportation and translation services, to more than 12,000 people.143

Tribal Health Centers

Indian Tribes (ITs), Tribal Organization (TOs), and Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs)144 may receive funds from the Indian Health Service (IHS) to operate health centers for American Indians or Alaska Natives. Although tribal health centers may be similar to health centers funded under Section 330 grants, they are not subject to Section 330 requirements. For example, they are not required to provide services to all individuals in their service area. They are also not required to seek payments or reimbursements on behalf of the clients they see because IHS provides services to all eligible American Indians and Alaska Natives free of charge. Tribal health centers—those operated by an IT, a TO, or a UIO—may be designated as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)145 and receive the Medicare and Medicaid FQHC payment rate (see Appendix B).146

ITs, TOs, and UIOs may also apply for and receive funds under Section 330 of the PHSA; however, should an entity receive Section 330 funds, it would be subject to all Section 330 requirements (i.e., would be required to provide services to non-American Indians and Alaska Natives). Tribal health centers that receive Section 330 grants are also required to ensure that funds received from IHS are used to provide services only to IHS-eligible individuals.

Rural Health Clinics

Rural health clinics (RHCs) are outpatient primary care facilities located in rural and medically underserved areas. These facilities receive higher Medicare and Medicaid payments—similar to the FQHC payment rate147—for services provided to beneficiaries enrolled in the Medicare and Medicaid programs. RHCs are similar to health centers, but, among other differences, they (1) do not receive federal grants, (2) may be operated by for-profit entities, (3) are not required to provide services to individuals regardless of ability to pay, and (4) are not required to offer a sliding-scale fee schedule.148

Free clinics are outpatient facilities that provide medical, dental, and behavioral health services to underserved populations that are primarily uninsured. Free clinics are tax-exempt organizations that provide health care to individuals regardless of their ability to pay and are not permitted to charge for services.149 In general, free clinic funding comes from donations (both monetary and in-kind), religious groups, foundations, and corporations.150 More than 1,200 free clinics151 provide services to a population that is similar to that served by health centers.152 Free clinics do not receive HRSA funding, but they may participate in the Free Clinics Medical Malpractice Program administered by HRSA, which provides liability coverage to health care providers at free clinics.153

Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Look-Alikes

FQHC look-alikes are facilities that meet the criteria to receive a health center grant but do not receive a grant because Section 330 funding is not available.154 The FQHC look-alike program was authorized in 1990 to support the demand for new health centers.155 HRSA and CMS can designate certain facilities as "FQHC look-alikes," making these facilities eligible for certain federal programs (e.g., the NHSC and the 340B drug discount program)156 available to health centers and for the FQHC payment rate. To be designated as an FQHC look-alike, a facility submits an application to HRSA, the agency reviews the application, and then recommends to CMS which facilities should be designated as FQHC look-alikes. In 2015, 54 look-alikes reported serving 709,293 patients.157 Generally, look-alikes offer similar services to health centers but may have more limited capacity than health centers; for example, they may offer fewer dental services.158

Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics

Section 223 (42 U.S.C. §1396a note) of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 (PAMA, P.L. 113-93) established a demonstration program in Medicaid to improve services provided by "certified community behavioral health clinics" in no more than eight states. PAMA created this designation and defined the staffing and other requirements for facilities to meet this designation, including that the designated facilities be open 24 hours a day, use a sliding-scale fee schedule, have culturally and linguistically competent staff with diverse disciplinary backgrounds, and have partnerships with certain facilities to provide continuity of care. The PAMA demonstration program occurred in two phases. Under the first phase, planning grants were awarded to 24 states to develop a Medicaid Prospective Payment System (PPS), under which these facilities will likely be paid a higher rate than they would have otherwise been paid. Under the second phase, eight states were selected from among those who received planning grants to create the new PPS.159 The second phase will begin by July 1, 2017, and last two years.

PAMA also requires the HHS Secretary to report annually to Congress about the demonstration project and to submit recommendations to Congress about whether the demonstration should be continued, expanded, modified, or terminated by December 31, 2021.

Appendix B. Medicare and Medicaid Payments and Beneficiary Cost Sharing for Health Center Services

All federal Health Center Program grantees may be designated as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs)160 upon enrolling as an FQHC in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.161 The FQHC designation makes Section 330 grantees (among others; see text box) eligible for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements rates that are generally higher than the reimbursement rates for comparable services provided in a physician's office.162 In FY2015, these reimbursements represented 47.8% of the Health Center Program's revenue (see Table 4). The FQHC designation was created to ensure that Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements cover the costs of providing services so that Section 330 grant funds are not used to subsidize these costs.163 This appendix describes Medicare and Medicaid payments to FQHCs. The Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148, as amended) required that a new Medicare payment methodology be developed. As a consequence, Medicare payments to FQHCs increased. This report describes current Medicare payment methodology. For information about the prior Medicare payment methodology, see CRS Report R42433, Federal Health Centers.164

|

Social Security Act FQHC Definition FQHC means (1) an entity that is receiving a PHSA Section 330 grant or is receiving funding through a contract with a PHSA Section 330 grant recipient; (2) an entity that meets the requirements to receive a PHSA Section 330 grant as determined by HRSA; (3) an entity that was treated by the Secretary of HHS as a comprehensive federally funded health center for the purposes of Medicare Part B as of January 1, 1990; or (4) an outpatient program or facility operated by an Indian Tribe, Tribal Organization, or Urban Indian Organization receiving funds authorized in the Indian Health Care Improvement Act. Source: §18611(aa)(4) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. §1395x and §1905(l)(2)(B), 42 U.S.C. §1396d. |

Medicare Payments to Health Centers165

Beginning October 1, 2014 (i.e., FY2015), Medicare FQHC payments increased as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)—the agency that administers the Medicare and Medicaid programs—implemented a prospective payment (PPS) system.166 This change was required in the ACA because of concerns that Medicare payments did not reflect the FQHC's costs of providing services to Medicare beneficiaries.167 To develop the PPS, CMS used the Medicare cost report and claims data to ensure that the rate reflects the cost of providing a specific bundle of FQHC services.168

Under the new PPS, FQHCs are paid the lesser of their actual charges or an encounter rate for professional services furnished to a beneficiary in a single day. Medicare pays 80% of this amount. The beneficiary pays the remainder as part of their required cost sharing for FQHC services. The encounter rate is intended to reflect 100% of the reasonable costs of providing a visit. It was calculated by estimating the reasonable costs that would have occurred for the year if the PPS was not implemented (with certain exceptions, e.g., flu and pneumococcal vaccines because they are paid at 100% of reasonable costs); this estimate was calculated without the application of copayments, per-payment limits, or productivity adjustments that limit Medicare payment to other provider types.

The new encounter rate is provided to each FQHC nationwide with a geographic adjustment. It is intended to reflect the type, intensity, and duration of services that FQHCs provide and is adjusted to account for the geographic location of the FQHC. Rates are also adjusted for the initial Medicare visit (i.e., the Welcome to Medicare exam) and for the annual wellness visit, which are determined to be more intensive than a standard visit.169 With some exceptions (e.g., mental health visit and when an injury occurs subsequent to the medical visit), the encounter rate is only paid to a facility once per day, because CMS determined that multiple visits per day were rare for Medicare beneficiaries. The new encounter rate applies to all services, with certain exceptions (e.g., influenza and pneumococcal vaccines and their administration, which are paid at 100% of reasonable costs). FY2015 was a period of transition to the PPS, which will be updated (in accordance with other Medicare payment updates) annually beginning January 1, 2016.170 Beginning January 1, 2017, the PPS base payment was updated by 1.8% using the FQHC market basket.171

Medicare beneficiaries are subject to different deductible and cost sharing requirements for services provided at FQHCs than they would otherwise be if they received the same services in a different setting (e.g., a physician group practice). Specifically, the Medicare Part B deductible does not apply for FQHC services.172 Beneficiaries not in managed care plans—with some exceptions173—must pay the 20% copayment for Medicare services. There are no copayments for preventive services, as required in the ACA.174 FQHC visits generally include a mix of preventive services (not subject to coinsurance) and services that are subject to coinsurance. To determine which charges will be subject to the coinsurance, CMS subtracts the dollar value of the FQHC's reported line-item charge for the preventive services provided from the full payment amount; Medicare then pays the FQHC 100% of the dollar value of the FQHC's reported line-item charge for the preventive services, up to the total payment amount. Medicare will also pay 80% of the remainder of the full payment amount. The beneficiary would then pay the remainder (the 20% coinsurance). Should the reported line-item charge for the preventive services equal or exceed the full payment amount, Medicare pays 100% of the full payment amount and the beneficiary would not be responsible for any coinsurance.

The rule that implemented the Medicare PPS also removed the requirement that auxiliary persons—certified nurse midwives, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical psychologists, and clinical social workers—be employees of the facility in order for the FQHC to bill Medicare for services that are provided "incident to"175 the services of physicians.176

Medicaid Payments

Medicaid uses a PPS to reimburse FQHCs for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries.177 The PPS establishes a predetermined per-visit payment rate for each FQHC (which differs from Medicare where there is a national rate) based on costs of services. The PPS was established based on cost report data in FY1999 and FY2000 and is updated annually for medical inflation.178 The state, in turn, receives the appropriate federal matching amount. States are also required to adjust PPS payment rates based on any changes in the scope of services provided at the FQHC. States are not required to use the PPS to reimburse FQHCs, but they may not reimburse an FQHC less than it would have received under the PPS.179 In 2015, according to NACHC, approximately 25 states and the District of Columbia used the PPS, 11 states used an alternative payment methodology (APM) to reimburse FQHCs under Medicaid, and 12 states used a combination of both methods.180 States using APMs generally use cost-based reimbursements and do so as a way of exploring payment reform options that include FQHCs. FQHCs are required to agree to receive the different rate.181

States are also required to supplement FQHCs that subcontract (directly or indirectly) with Medicaid Managed Care Entities (MCEs). These supplemental payments are supposed to make up the difference, if any, between the payment received by the FQHC from the MCE and the Medicaid payment that the FQHC would be entitled to under the PPS or the APM.182 The ACA did not include changes in Medicaid FQHC reimbursement policy.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information about the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), see CRS Report R44505, Public Health Service Agencies: Overview and Funding (FY2015-FY2017), and CRS Report R44054, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Funding: Fact Sheet. |

| 2. |

42 U.S.C. §254b. |

| 3. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, "Health Care Service Delivery Sites," http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/hccsites.aspx. |

| 4. |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, "Uniform Data System (UDS) Report, National Rollup Report, 2015," at https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=tall&year=2015&state=&fd=, hereinafter, 2015 UDS Report. |

| 5. |

42 U.S.C. §254b. |

| 6. |