Temporary Professional, Managerial, and Skilled Foreign Workers: Policy and Trends

Temporary visas for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers have become an important gateway for high-skilled immigration to the United States. Over the past two decades, the number of visas issued for temporary employment-based admission has more than doubled from just over 400,000 in FY1994 to over 1 million in FY2015. While these visa numbers include some unskilled and low-skilled workers as well as accompanying family members, the visas for managerial, skilled, and professional workers dominate the trends.

Since 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) has authorized visas for foreign nationals who would perform needed services because of their high educational attainment, technical training, specialized experience, or exceptional ability. Today, there are several temporary visa categories that enable employment-based temporary admissions for highly skilled foreign workers. These visa categories are commonly referred to by the letter and numeral that denote their subsection in the INA. They perform work that ranges from skilled labor to management and professional positions to jobs requiring extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics.

Policymakers and advocates have focused on two visa categories in particular: H-1B visas for professional specialty workers, and L visas for intra-company transferees. These two nonimmigrant visas epitomize the tensions between the global competition for talent and potential adverse effects on the U.S. workforce. The employers of H-1B workers are the only ones required to meet labor market tests in order to hire professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers.

Although foreign students on F visas are generally barred from off-campus employment, some F-1 foreign students are permitted to participate in employment known as Optional Practical Training (OPT) after completing their undergraduate or graduate studies. OPT is temporary employment that is directly related to an F-1 student’s major area of study. Generally, an F-1 foreign student may work up to 12 months in OPT status. In 2008, the Bush Administration added a 17-month extension to OPT for F-1 students in STEM fields, and the Obama Administration recently proposed a 24-month extension for F-1 students in STEM fields.

Congress has an ongoing interest in regulating the immigration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers to the United States. This workforce is seen by many as a catalyst of U.S. global economic competitiveness and is likewise considered a key element of the legislative options aimed at stimulating economic growth. The challenge central to the policy debate is facilitating the migration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers without putting downward pressures on U.S. workers and U.S. students entering the labor market.

Temporary Professional, Managerial, and Skilled Foreign Workers: Policy and Trends

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview of the Issues

- Policy Questions

- Specific Concerns

- H-1B Visa Issues

- L-1 Visa Issues

- Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Workers

- Temporary Professional Specialty Worker: H-1B Visas

- Treaty Professional Specialty Workers: TN and E-3 Visas

- Cultural Exchange Workers: J and Q Visas

- "Conrad 30" J Visa Waiver

- Q Cultural Exchange

- Multinational Executive and Specialist Employees: L-1 Visas

- International Investors and Traders: E Visas

- Persons with Outstanding and Extraordinary Ability: O and P Visas

- Religious Workers: R Visas

- Trends by Category of Worker

- Optional Practical Training (OPT)

- Taxation Rules and Exceptions

- Federal Income Taxes

- Social Security and Medicare Taxes

- Opportunities for Legal Permanent Residence

- Dual Intent and the §214(b) Presumption

- Concluding Comments

Figures

- Figure 1. Temporary Employment-Based Visas Issued, FY1994-FY2015

- Figure 2. Total H-1B Petitions Approved, FY1994-FY2014

- Figure 3. Visas Issued to Principals by Categories of Temporary Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Employees in FY2015

- Figure 4. Trends in Temporary Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Employee Visas Issued to Principals, FY1994–FY2015

- Figure 5. F-1 Foreign Students Approved for Optional Practical Training:

Summary

Temporary visas for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers have become an important gateway for high-skilled immigration to the United States. Over the past two decades, the number of visas issued for temporary employment-based admission has more than doubled from just over 400,000 in FY1994 to over 1 million in FY2015. While these visa numbers include some unskilled and low-skilled workers as well as accompanying family members, the visas for managerial, skilled, and professional workers dominate the trends.

Since 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) has authorized visas for foreign nationals who would perform needed services because of their high educational attainment, technical training, specialized experience, or exceptional ability. Today, there are several temporary visa categories that enable employment-based temporary admissions for highly skilled foreign workers. These visa categories are commonly referred to by the letter and numeral that denote their subsection in the INA. They perform work that ranges from skilled labor to management and professional positions to jobs requiring extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics.

Policymakers and advocates have focused on two visa categories in particular: H-1B visas for professional specialty workers, and L visas for intra-company transferees. These two nonimmigrant visas epitomize the tensions between the global competition for talent and potential adverse effects on the U.S. workforce. The employers of H-1B workers are the only ones required to meet labor market tests in order to hire professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers.

Although foreign students on F visas are generally barred from off-campus employment, some F-1 foreign students are permitted to participate in employment known as Optional Practical Training (OPT) after completing their undergraduate or graduate studies. OPT is temporary employment that is directly related to an F-1 student's major area of study. Generally, an F-1 foreign student may work up to 12 months in OPT status. In 2008, the Bush Administration added a 17-month extension to OPT for F-1 students in STEM fields, and the Obama Administration recently proposed a 24-month extension for F-1 students in STEM fields.

Congress has an ongoing interest in regulating the immigration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers to the United States. This workforce is seen by many as a catalyst of U.S. global economic competitiveness and is likewise considered a key element of the legislative options aimed at stimulating economic growth. The challenge central to the policy debate is facilitating the migration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers without putting downward pressures on U.S. workers and U.S. students entering the labor market.

Congress has an ongoing interest in regulating the immigration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers to the United States. This workforce is seen by many as a catalyst of U.S. global economic competitiveness and is likewise considered a key element of the legislative options aimed at stimulating economic growth. The challenge central to the policy debate is facilitating the migration of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers without adversely affecting U.S. workers and U.S. students entering the labor market.

This report opens with an overview of the policy issues. It follows with a summary of each of the various visa categories available for temporary professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers as well as an analysis of the trends in the use of these various visas over the past two decades. The policy of authorizing foreign students to work in the United States for at least a year following graduation is discussed next. The labor market tests for employers hiring temporary foreign workers are also summarized. The rules regarding federal taxation of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers are explained. The report concludes with a discussion of the avenues for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers to become legal permanent residents (LPRs) in the United States.

Overview of the Issues

Temporary visas for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers have become an important gateway for high-skilled immigration to the United States.1 Over the past two decades, the number of visas issued annually for all temporary employment-based admission has more than doubled from just over 400,000 in FY1994 to over 1 million in FY2015.2 As Figure 1 shows, the total number of temporary employment-based visas issued in FY2007 and FY2008 surpassed 1 million and subsequently fell during the 2007-2009 recession.3 While the total visa numbers include some unskilled and low-skilled workers,4 the visas for managerial, skilled, and professional workers depicted in Figure 1 clearly dominate the trends. In FY2014 and FY2015, visas for managerial, skilled, and professional workers surpassed the prior peak year of FY2007 (885,232) as they reached 929,129 and 984,360, respectively.

The data presented in Figure 1 understate the trends in professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers because the State Department does not issue visas to nonimmigrants who change status within the United States. For example, a foreign national who is in the United States as a student may convert status to a temporary foreign worker nonimmigrant without going abroad to obtain a new visa. For comparison, the Department of Homeland Security Office of Immigration Statistics estimated that there were approximately 1.1 million temporary workers and long-term exchange residents living in the United States in January 2012;5 and the State Department reported that there were 937,366 visas issued to temporary employment-based workers and their families in FY2012.6

|

Figure 1. Temporary Employment-Based Visas Issued, FY1994-FY2015 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the annual reports of the U.S. Department of State Office of Visa Statistics, Visa Report, Table XVI(B) Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Classification (Including Border Crossing Cards), multiple years. Notes: Includes managerial, professional, skilled, and unskilled temporary employees and accompanying family; does not include foreign nationals converting to temporary employment-based visas within the United States. See Table A-1for a list of employment-based nonimmigrant visas. |

The foreign labor certification program in the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) is responsible for ensuring that foreign workers do not displace or adversely affect the working conditions of U.S. workers. Under current law, DOL adjudicates labor certification applications (LCA) for permanent employment-based immigrants.7 Many of the foreign nationals entering the United States on a temporary basis for employment, however, are not subject to any labor market tests (i.e., demonstrating that there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available), and as a result, their employers do not file LCAs with the DOL. There are several groups of temporary foreign employees, however, that are covered by labor market tests.8 DOL adjudicates the streamlined LCA known as labor attestations for certain temporary workers, as discussed more fully below.9

Policy Questions

The admission of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers poses a complex set of policy questions as the United States competes internationally for the most talented workers in the world, while the nation also contends with historically high long-term unemployment rates and youth unemployment rates.10

- Should the number of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers be numerically limited each year? If so, should some classes or types of workers be exempt from numerical limits?

- Should employers of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers be required to meet labor markets tests, such as making efforts to recruit U.S. workers and offering wages and benefits that are comparable to similarly employed U.S. workers?

- What, if any, labor protections and worker rights should be extended to professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers to prevent abuse or exploitation of the worker?

- What, if any, guarantees should professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers make to their employers to ensure the contractual obligations are met?

- Should professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers have "visa portability" so they can change jobs? If so, to what visa categories and under what circumstances should visa portability apply?

- Should regulations governing the admission of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers be streamlined so that the rules are less time consuming and burdensome for employers?

- Should professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers be permitted to have "dual intent," that is, to apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status while seeking or renewing temporary visas? If so, for what visa categories and under what circumstances should dual intent be permitted?

Specific Concerns

In addition to these cross-cutting questions, policymakers and advocates have focused on two visa categories in particular: H-1B visas for professional specialty workers, and L visas for intra-company transferees. These two nonimmigrant visas epitomize the tensions between the global competition for talent and potential adverse effects on the U.S. workforce.

H-1B Visa Issues

H-1B visas are for temporary "professional specialty workers," an employment category closely associated with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, but not limited to them.11 The H-1B visa has been an important avenue for many U.S. businesses seeking to recruit high-skilled foreign workers, but the category has numerical limits. 12 Applications for new H-1B workers have routinely exceeded such limits in recent years—in some years exceeding limits during the first week or even on the first day that applications are received. In addition to these concerns about whether employers have adequate access to H-1B workers, some Members of Congress have raised questions about whether H-1B workers may be placing downward pressure on wages and benefits as well as discouraging or displacing U.S. students in STEM fields.13

Over the years, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued reports that recommended more controls to protect workers, to prevent abuses, and to streamline services in the issuing of H-1B visas. GAO has observed that the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has limited authority to question information on the labor attestation form and to initiate enforcement activities.14 In 2011, GAO identified several weaknesses in the H-1B program's ability to protect workers: (1) oversight that is fragmented between four agencies and restricted by law; (2) lack of legal authority to hold employers accountable to program requirements when they obtain H-1B workers through a staffing company; and (3) expansions that have increased the pool of H-1B workers beyond the cap and lowered the bar for eligibility.15

A 2008 internal Department of Homeland Security (DHS) investigation of H-1B visa adjudications found a 13.4% fraud rate as well as a 7.3% technical violation rate. Violations reportedly ranged from document fraud to deliberate misstatements regarding job locations, wages paid, and duties performed. The investigation also discovered that some petitioning employers shifted the burden of paying various filing fees to foreign workers. A 2010 DHS investigation found a 14% "not verified" rate, which U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officials cited to suggest a reduced level of fraud in the H-1B program. 16 It was unclear, however, how the 14% "not verified" rate compared with 13.4% fraud rate and the 7.3% technical violation rate.

Media coverage of the links between H-1B workers and outsourced jobs has sparked outrage, and a bipartisan group of Members has called for further investigations and legislative action.17 More specifically, the major U.S. utility company Southern California Edison announced plans in early 2015 to lay off 400 U.S. technology workers and to outsource the technology-related work to companies in India. The India-based companies reportedly proposed to use H-1B workers to perform technology-related work that would remain in California.18 More recently, the New York Times published a series that exposed companies such as Disney and Toys 'R' Us requiring their U.S. workers to train H-1B workers before their positions were outsourced overseas.19

L-1 Visa Issues

The L-1 intra-company transferee visa was established for companies that have offices abroad to transfer key personnel freely within the organization.20 It is considered a visa category essential to retaining and expanding international businesses in the United States. Some, however, have raised concerns that intra-company transferees on the L-1 visa may displace U.S. workers who had been employed in those positions for these firms in the United States. Others express concern that the L-1 visa has become a substitute for the H-1B visa, noting that L-1 employees are often comparable in skills and occupations to H-1B workers, yet lack the labor market protections the law sets for hiring H-1B workers. These concerns have been raised, in particular, with respect to certain outsourcing and information technology firms that employ L-1 workers as subcontractors within the United States. A related concern is that an unchecked use of L-1 visas will foster the transfer of STEM and other high-skilled professional jobs overseas, as managers and specialists gain experience in the United States before they transfer the operations abroad. After investigating the L-1 visa, the Department of Homeland Security Inspector General offered this assessment: "That so many foreign workers seem to qualify as possessing specialized knowledge appears to have led to the displacement of American workers, and to what is sometimes called the 'body shop' problem."21 Legislation to address these concerns is frequently linked with H-1B reform.22

On the other hand, concern has been expressed about the increase in denials of L-1 visas as well as the increase in requests for additional evidence in order to adjudicate the L petition. Stuart Anderson of the National Foundation for American Policy analyzed the subset of L-1 petitions for employees with specialized knowledge (L-1B). Over a 10-year period from FY2004 to FY2013, denials of L-1B petitions rose from 10% in FY2004 to 34% in FY2013. The same study reported that requests for additional evidence went from 2% of L-1B petitions to 46% of L-1B petitions. 23 Immigration attorney and former chief counsel at USCIS Lynden Melmed is quoted as saying, "(I)t is very difficult for companies to make business decisions when there is so much uncertainty in the L-1 visa process. A company is going to be unwilling to invest in a manufacturing facility in the U.S. if it does not know whether it can bring its own employees into the country to ensure its success."24

It is difficult to assess the merits of these concerns without a deeper understanding of the temporary visas for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers. The following section of this report delves into the purposes of the various visas, the statutory rules that govern admission under these visas, and the trends in usage of these visas.

Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Workers

When it was enacted in 1952, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) authorized visas for foreign nationals who would perform needed services because of their high educational attainment, technical training, specialized experience, or exceptional ability. Today, there are several temporary visa categories that enable employment-based temporary admissions for highly skilled foreign workers. These visa categories are commonly referred to by the letter and numeral that denote their subsection in the INA.25 They perform work that ranges from skilled labor to management and professional positions to jobs requiring extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics.

Temporary Professional Specialty Worker: H-1B Visas

The INA makes H-1B nonimmigrant visas available for foreign workers in "specialty occupations," which the regulations define as requiring theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialized knowledge in a field of human endeavor including, but not limited to, architecture, engineering, mathematics, physical sciences, social sciences, medicine and health, education, law, accounting, business specialties, theology, and the arts, and requiring the attainment of a bachelor's degree or its equivalent as a minimum.26 Current law generally limits annual H-1B admissions to 65,000, but most H-1B workers are exempted from the limits because they are returning workers or they work for universities and nonprofit research facilities that are exempt from the cap.27

Prospective employers of H-1B workers must submit a labor attestation to the Secretary of Labor before they can file petitions with USCIS to bring in foreign workers. The H-1B labor attestation, a three-page application form, is a statement of intent rather than a documentation of actions taken. In the labor attestation for an H-1B worker, the employer must attest that the firm will pay the nonimmigrant the greater of the actual wages paid to other employees in the same job or the prevailing wages for that occupation, that the firm will provide working conditions for the nonimmigrant that do not cause the working conditions of the other employees to be adversely affected, and that there is no applicable strike or lockout. The firm must provide a copy of the labor attestation to representatives of the bargaining unit or—if there is no bargaining representative—post the labor attestation in conspicuous locations at the work site.28

H-1B Dependent Requirements

The law requires that employers defined as H-1B dependent (generally firms with at least 15% of the workforce who are H-1B workers) meet additional labor market tests.29 These H-1B dependent employers must also attest that they tried to recruit U.S. workers and that they have not displaced U.S. workers in similar occupations within 90 days prior to or after the hiring of H-1B workers. Additionally, the H-1B dependent employers must offer the H-1B workers compensation packages (not just wages) that are comparable to U.S. workers.30

All prospective H-1B nonimmigrants must demonstrate to USCIS that they have the requisite education and work experience for the posted positions. After DOL has approved the labor attestation, USCIS processes the petition for the H-1B nonimmigrant (assuming other immigration requirements are satisfied) for periods up to three years. A foreign national can stay a maximum of six years on an H-1B visa.

H-1B Trends

The Immigration Act of 1990 set an annual cap of 65,000 H-1B workers, a level not reached in the early years of the visa category. As the information technology industry began turning to H-1B visas for temporary foreign workers, the limits of the cap were reached. Although Congress enacted legislation in 1998 to increase the number of H-1B visas,31 that annual ceiling of 115,000 visas was reached months before FY1999 and FY2000 ended. Many in the business community, notably in the information technology area, once more urged that the ceiling be raised. In 2000, Congress enacted legislation to raise the annual ceiling to 195,000 for three years and to permanently exempt those H-1B workers who are renewing their visas or who work for universities and nonprofit research facilities from the 65,000 cap.32 During this temporary period, the higher cap of 195,000 was not met because an increasing number of H-1B workers were now exempt from the cap. A subsequent provision also annually exempts up to 20,000 aliens holding a master's or higher degree from the numerical limit on H-1B visas.33

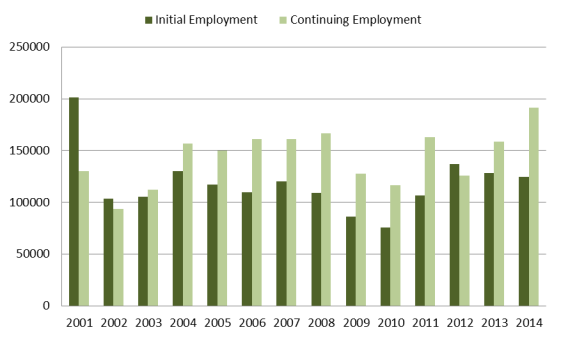

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers, multiple years. Notes: Congress increased the H-1B cap to 195,000 for FY2001-FY2003. The H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004 set aside up to 20,000 H-1B visas for those who have U.S.-earned masters or higher degrees in addition to the 65,000 cap. Not all H-1B workers with approved petitions actually use the visa. FY2014 was the most recent data available that differentiated H-1B visa approvals by "initial employment" and "continuing employment." |

In FY2015, USCIS approved 275,317 H-1B professional specialty worker petitions,34 an increase from a 21st century low point of 192,990 in FY2010 following the 2007-2009 recession. 35 The number of petitions approved in FY2015 also represents a decrease from the previous year, FY2014, where USCIS approved 315,857 petitions. The previous high point was 331,206 H-1B professional specialty worker petitions approved in FY2001. Although current law sets a numerical limit of 65,000 H-1B workers each year (plus 20,000 with masters degrees), only initial grants are counted under the cap. As Figure 2 displays, over the past decade more H-1B workers were approved outside of the numerical limits than under the cap. Not all H-1B workers with approved petitions actually use the visa.

Over the years, a noteworthy portion of H-1B beneficiaries have worked in STEM occupations. In FY2014, the most recent year for which detailed data on H-1B beneficiaries (i.e., workers renewing their visas as well as newly arriving workers) are available, 203,425 H-1B workers were employed in computer-related occupations, and they made up 65% of all H-1B beneficiaries that year. Of all H-1B beneficiaries in FY2014, 45% had a bachelor's degree, 47% had a master's or professional degree, and almost 8% had a doctorate degree. The median salary reported for all H-1B beneficiaries in FY2014 was $75,000.36

Treaty Professional Specialty Workers: TN and E-3 Visas

There are two nonimmigrant visa categories similar to H-1B visas that are designated for temporary professional workers from specific countries. These visas are based upon specific trade agreements foreign nations have signed with the United States. Canadian and Mexican temporary professional workers may enter according to terms set by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on TN visas. The E-3 treaty professional visa is a temporary work visa limited to citizens of Australia.37 Occupationally, they mirror the H-1B visa in that the foreign worker on an E-3 visa or a TN visa must be employed in a specialty occupation. Employers of E-3 workers are required to file a labor attestation. The TN visa is valid for one year and is renewable.

Cultural Exchange Workers: J and Q Visas

The broadest category for cultural exchange is the J visa, which includes professors and research scholars, students, foreign medical graduates, teachers, resort workers, camp counselors, and au pairs who are participating in an approved exchange visitor program. The U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (BECA) is responsible for approving the cultural exchange programs. J visa holders are admitted for the period of the program. Most foreign nationals on J-1 visas are permitted to work as part of their cultural exchange program participation. The J cultural exchange visas have expanded over time from visas issued for educational, research, or scholarship purposes to visas issued for programs engaged in more mundane tasks, such as child care, resort work, or camp counseling. Today, the J visas may be issued to over a dozen subcategories of exchange visitors, many of whom work in the United States.

"Conrad 30" J Visa Waiver

Currently, foreign medical graduates may enter the United States on J-1 visas in order to receive graduate medical education and training. As is the case with most foreign nationals on J-1 visas, foreign medical graduates must return to their home countries after completing their education or training for at least two years before they can apply for certain other nonimmigrant visas or LPR status, unless they are granted a waiver of the foreign residency requirement. States are permitted to sponsor up to 30 waivers per state, per year on behalf of FMGs under a temporary program, colloquially known as the Conrad 30 Program because it was originally sponsored by former Senator Kent Conrad. The objective of the Conrad 30 Program is to encourage immigration of foreign physicians to medically underserved communities. GAO has reported that it has been a major means of providing physicians to practice in underserved areas of the United States.38

Q Cultural Exchange

The Q visa is used by a smaller employment-oriented cultural exchange program, and its stated purpose is to provide practical training and employment as well as share history, culture, and traditions. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) approves the Q cultural exchange programs, and only employers are allowed to petition for Q nonimmigrants. USCIS encourages the prospective employer to submit evidence illustrating that the program activities take place in a public setting where the sharing of culture can be achieved through direct interaction with the American public. Employers are expected to offer the Q cultural exchange worker wages and working conditions comparable to other workers in the locale that are similarly employed.

Multinational Executive and Specialist Employees: L-1 Visas

Intra-company transferees who are executive, managerial, or have specialized knowledge and are employed with an international firm or corporation are admitted on the L-1 visas. The prospective L-1 nonimmigrant must demonstrate that he or she meets the qualifications for the particular job as well as the visa category. The foreign national must have been employed by the firm for at least six months in the preceding three years in the capacity for which the transfer is sought. The foreign national must be employed in an executive capacity, a managerial capacity, or have specialized knowledge of the firm's product to be eligible for the L-1 visa. Those with specialized knowledge are often labeled L-1B. The INA does not require firms who wish to bring L-1 intra-company transfers into the United States to demonstrate that U.S. workers will not be adversely affected in order to obtain a visa for the transferring employee. The L-1 visa is valid for five years and is renewable for a total of seven years.

International Investors and Traders: E Visas

Aliens who are treaty traders enter on E-1 visas, whereas those who are treaty investors enter on E-2 visas. An E-1 treaty trader visa allows a foreign national to enter the United States for the purpose of conducting "substantial trade" between the United States and the country of which the person is a citizen. An E-2 treaty investor can be any person who comes to the United States to develop and direct the operations of an enterprise in which he or she has invested, or is in the process of investing a "substantial amount of capital." Both these E-class visas require that a treaty exist between the United States and the principal foreign national's country of citizenship.39 Both the E-1 and E-2 visas are valid for two years and are renewable in two-year intervals.

Persons with Outstanding and Extraordinary Ability: O and P Visas

Persons with extraordinary ability in the sciences, the arts, education, business, or athletics can be admitted on O visas. Generally, the O visa is reserved for the highest level of accomplishment and covers a fairly broad set of occupations and endeavors, including athletics and entertainment. Regulations implementing the O visa define extraordinary ability in the field of science, education, business, or athletics as a level of expertise indicating that the person is one of a small percentage that has arisen to the very top of the field of endeavor.40 The O visa is valid for up to three years and is renewable for one year.

The P visa has a somewhat lower standard of achievement than the O visa, and it is restricted to a narrower band of occupations and endeavors. The P visa is used by an alien who performs as an artist, athlete, or entertainer (individually or as part of a group or team) at an internationally recognized level of performance and who seeks to enter the United States temporarily and solely for the purpose of performing in that capacity. The law allows individual athletes to stay in intervals up to five years at a time, up to 10 years in total.

Religious Workers: R Visas

Foreign nationals working in religious vocations enter on R visas. The regulations define religious occupation as "an activity which relates to a traditional religious function." USCIS further defined "religious denomination" to clarify that it applies to a religious group or community of believers governed or administered under some form of common ecclesiastical government. Under the regulations, the denomination must share a common creed or statement of faith, some form of worship, a formal or informal code of doctrine and discipline, religious services and ceremonies, established places of religious worship, religious congregations, or comparable indicia of a bona fide religious denomination. The initial length of admission on an R visa is for a period up to 30 months.41

Trends by Category of Worker

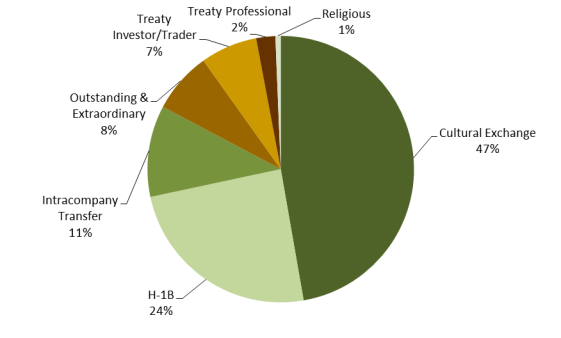

A more detailed presentation of visas issued to professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers by visa category for FY2015 is presented in Figure 3. As some, but not all, visa categories differentiate between the principal or qualifying foreign national and derivative immediate family that are permitted to accompany the foreign national, Figure 3 omits the derivative family members when possible. The total number of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign worker visas issued abroad to principals was 707,781in FY2015.42

|

Figure 3. Visas Issued to Principals by Categories of Temporary Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Employees in FY2015 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the annual reports of the U.S. Department of State Office of Visa Statistics, Visa Report, Table XVI(B), 2015. Note: There were 707,871 visas issued to principals for the visa categories displayed in the figure. Derivative family members are omitted when they are entering through a separate visa category (e.g., H-4, J-2, L-2, R-2). The 172,748 H-1B visas issued abroad represent about 60% of all H-1B petitions USCIS approved in FY2015; the other 40% changed status within the United States. "Treaty Investor/Trader" includes E-1, E-2, and E-2C visas. "Outstanding & Extraordinary" includes O-1, O-2, P-1, P-2, and P-3 visas. "Cultural Exchange" includes J-1 and Q-1 visas. "Intracompany Transfer" includes L-1 visas and "Religious' includes R-1 visas. "H1-B" includes H-1B visas. "Treaty Professional" includes E-3, E-3R, TN, and H-1B1 visas. See Table A-1for a description of each visa symbol. |

Although the cultural exchange workers are the largest single category of temporary foreign workers (47%), it is important to note that about one-third of the J-1 visas are issued to persons engaged in Summer Work Travel (SWT). The State Department characterizes SWT as providing "foreign students with an opportunity to live and work in the United States during their summer vacation from college or university to experience and to be exposed to the people and way of life in the United States."43 Many compare this use of the J-1 visas for SWT to the H-2 visas for seasonal and shortage guest workers.44 Similarly, the Q visa is often used by the hospitality and entertainment industry (e.g., Disney Parks). Q visas comprised less than 1% of all cultural exchange visas issued in FY2015.

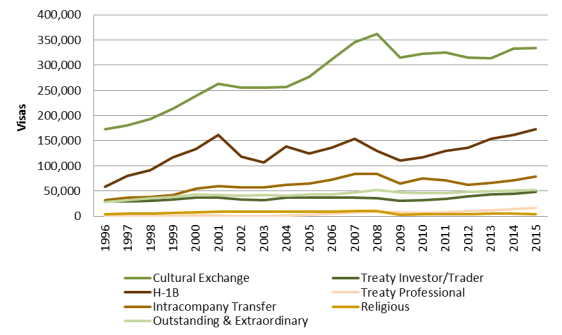

Over the past two decades, the numbers of visas issued to each of the categories of professional, managerial, and skilled foreign worker have increased. The relative portions, however, have not changed substantially, as Figure 4 makes clear. The professional workers (H-1Bs and TNs), the cultural exchange workers (J-1), and the intra-company transferees (L-1) have driven most of the growth over the past two decades. There has also been a slow but steady increase in foreign workers deemed outstanding and extraordinary (O and P) over this same period. Only the religious worker visa category has remained rather flat.

|

Figure 4. Trends in Temporary Managerial, Professional, and Skilled Employee Visas Issued to Principals, FY1996–FY2015 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the annual reports of the U.S. Department of State Office of Visa Statistics, Visa Report, Table XVI(B) Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Classification (Including Border Crossing Cards), multiple years. Note: Derivative family members are omitted when they are entering through a separate visa category (e.g., H-4, J-2, or L-2). "Treaty Investor/Trader" includes E-1, E-2, and E-2C visas. "Outstanding & Extraordinary" includes O-1, O-2, P-1, P-2, and P-3 visas. "Cultural Exchange" includes J-1 and Q-1 visas. "Intracompany Transfer" includes L-1 visas and "Religious' includes R-1 visas. "H1-B" includes H-1B visas. "Treaty Professional" includes E-3, E-3R, TN, and H-1B1 visas. See Table A-1for a description of each visa symbol. |

Optional Practical Training (OPT)

Although foreign students on F visas are generally barred from off-campus employment,45 some F-146 foreign students are permitted to participate in employment known as Optional Practical Training (OPT) after completing their undergraduate or graduate studies. OPT is temporary employment that is directly related to an F-1 student's major area of study. Generally, an F-1 foreign student may work up to 12 months in OPT status. In 2008, the Bush Administration expanded the OPT work period to 29 months for F-1 students in STEM fields. To qualify for the 17-month extension, F-1 students must have received STEM degrees included on the STEM Designated Degree Program List, be employed by employers enrolled in E-Verify,47 and have received an initial grant of post-completion OPT related to such a degree (i.e., already approved for 12 months in OPT).48

President Barack Obama's Immigration Accountability Executive Action of November 20, 2014, included a "High Skilled Memorandum" that directed USCIS and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to develop regulations to expand the number of degree programs eligible for OPT, and to extend the time period and use of OPT for STEM students and graduates. The new policy would also require the OPT program to have stronger ties to degree-granting institutions to ensure that a student's OPT furthers his or her course of study in the United States. In addition, the "High Skilled Memorandum" stated that the new policy would have to be consistent with U.S. worker protections.49 DHS proposed new rules in October 2015 that, among other things, would extend the 17-month extension for STEM graduates to a 24-month extension.50

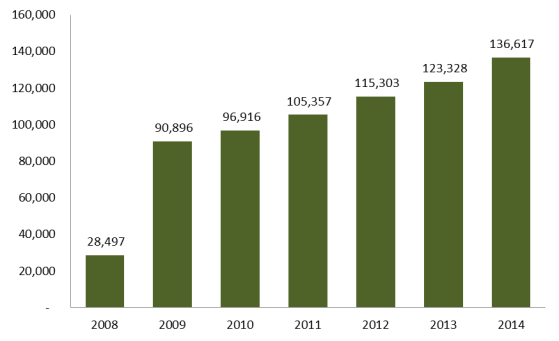

|

Figure 5. F-1 Foreign Students Approved for Optional Practical Training: FY2008-FY2014 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. |

According to USCIS, the number of F-1 visa holders who are engaged in OPT has risen substantially, from 28,497 in FY2008 to 136,617 in FY2014 (Figure 5). OPT workers are now approaching the H-1B workers in terms of number of visas issued annually.

In 2014, GAO released a report noting the potential for fraud and abuse of the OPT status. GAO concluded that DHS' Immigration and Customs Enforcement was unable to "fully ensure foreign students working under optional practical training are maintaining their legal status in the United States."51

Taxation Rules and Exceptions

Federal Income Taxes

Foreign nationals in the United States are classified as resident or nonresident aliens for federal income tax purposes. Resident aliens are generally subject to the same income tax obligations as citizens of the United States. Temporary foreign workers may also be considered resident aliens if they satisfy a "substantial presence" test based upon the number of days they have been in the United States.52 If the foreign national is on an F, J, M, or Q visa53 working as a teacher, student, or trainee, the days working in that capacity do not count toward substantial presence.54 Professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers as a category are generally not exempt from the individual mandate to have health care coverage under the Affordable Care Act.55

Social Security and Medicare Taxes

In terms of the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA), most noncitizens employed in the United States are subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes on wages in the same manner as U.S. citizens.56 However, the Internal Revenue Code specifically excludes the employment of foreign temporary agricultural workers, foreign students on F and M visas, and cultural exchange visitors on J and Q visas from the definition of employment for the purposes of FICA.

Regulations implementing current FICA law for employment of students provide that when an individual is working for a college or university and when the primary status of the individual is as a student, rather than as an employee, then any work performed is excluded from employment for purposes of FICA. The regulations clarify that full-time employees are not "students" for purposes of the FICA exception. "If an employee is not a full-time employee, then whether the employee qualifies as a student depends on all the relevant facts and circumstances. An individual is a student if education, not employment, is the predominant aspect of the employee's relationship with the employer."57 For example, medical residents working full-time are not considered students by the IRS and are subject to FICA payroll taxes.58 Although most students working off-campus are typically engaged in work that would be covered by FICA taxes, the regulations expressly exempt foreign students and exchange visitors from FICA, if DHS has given them work authorization.59

In terms of foreign students and cultural exchange visitors, current law on the definition of employment exempts the following for the purposes of FICA:

Service which is performed by a nonresident alien individual for the period he is temporarily present in the United States as a nonimmigrant under subparagraph (F), (J), (M), or (Q) of section 101(a)(15) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended, and which is performed to carry out the purpose specified in subparagraph (F), (J), (M), or (Q) as the case may be.60

This blanket exemption for foreign nationals on F and J visas (as well as M and Q visas) is based upon nonimmigrant status. It does not differentiate the type of employment or relationship to the employer. To continue the example of medical residents, a foreign national who is on a J visa as a medical resident working full-time is not subject to FICA payroll taxes. If a foreign national on an F-1, J-1, M-1, or Q visa performs work that is not connected to the purpose for which he or she was admitted to the United States, the employment is covered by Social Security, unless otherwise specifically excluded by law.

According to the IRS, the following types of employment of F-1 and J-1 workers are exempt from FICA taxes:

- On-campus student employment up to 20 hours a week (40 hours during summer vacations).

- Off-campus student employment authorized by USCIS.

- OPT student employment on or off campus.

- Employment as professor, teacher, or researcher.

- Employment as a physician, au pair, or summer camp worker.61

Totalization Agreements that the United States has signed with selected foreign governments to avoid double taxation of income for social security purposes also bear on whether the temporary foreign workers are subject to FICA.62

Opportunities for Legal Permanent Residence

Temporary professional visas have become an important gateway for high-skilled immigration to the United States. 63 About half of all employment-based lawful permanent residents (LPRs) have been working in the United States on temporary visas. More specifically, 46% of the foreign nationals who became employment-based LPRs in the United States during the decade of 2000-2009 had formerly held H-1B visas.64 Over this same time period, almost half (48.6%) of employment-based principals who were deemed extraordinary/priority workers had been L intracompany transferees. 65

More recently, the OPT status may provide the link for foreign students to become employment-based LPRs. Many anecdotal accounts tell of foreign students who are hired by U.S. firms as they are completing their programs. Employers may opt to hire them as OPT to extend their F-1 visas. According to DHS: "This extension of the OPT period for STEM degree holders gives U.S. employers two chances to recruit these highly desirable graduates through the H-1B process, as the extension is long enough to allow for H-1B petitions to be filed in two successive fiscal years."66 If the temporary foreign workers meet expectations, the employers may also petition for them to become LPRs through one of the employment-based immigration categories.67

Over 90% of employment-based LPRs are adjusting from a temporary visa category to LPR status within the United States, rather than newly arriving from abroad. Because the INA requires most foreign nationals seeking to qualify for a nonimmigrant visa to demonstrate that they are not coming to reside permanently, these adjustment of status statistics prompt further explanation on the exceptions noted in the law.

Dual Intent and the §214(b) Presumption

Temporary workers who are H-1B or L visa holders are permitted to petition for a LPR visa at the same time that they file for an H-1B or L visa, a policy exception known as dual-intent.68 (i.e., generally, a foreign national applying for a temporary visa cannot also be seeking an LPR visa). Specifically, §214(b) of the INA generally presumes that all aliens seeking admission to the United States are coming to live permanently; as a result, most foreign nationals seeking to qualify for a nonimmigrant visa must demonstrate that they are not coming to reside permanently. Currently, the INA exempts foreign nationals seeking H-1 professional visas and L intra-company transferee visas (as well as V accompanying family members) from the requirement that they prove they are not coming to live permanently.69

Concluding Comments

The metaphor for U.S. policy on economic migration is a post at the border with two signs: one reads "Help Wanted," and the other reads "Keep Out." This tension between competing interests on foreign workers has long characterized American immigration policy. 70 Balancing these priorities on the issues of temporary visas for professional, managerial, and skilled foreign workers is no small feat, and is further complicated by a lack of consensus on the broader policy debate over comprehensive immigration reform.

Appendix. Employment-Based Nonimmigrant Visas

|

Visa Symbol |

Visa Class |

||

|

CW-1 |

CNMI-only transitional workers |

||

|

CW-2 |

Spouse and child of CW-1 |

||

|

E-1 |

Treaty trader, spouse and child |

||

|

E-2 |

Treaty investor, spouse and child |

||

|

E-2C |

CNMI investor, spouse and child |

||

|

E-3 |

Australian specialty occupation professional |

||

|

E-3D |

Spouse and child of E-3 |

||

|

E-3R |

Returning E-3 |

||

|

H-1B |

Temporary worker of distinguished merit and ability performing services other than as a registered nurse |

||

|

H-1B1 |

Free Trade Agreement Professional |

||

|

H-2A |

Temporary worker performing agricultural services |

||

|

H-2B |

Temporary worker performing other services |

||

|

H-3 |

Trainee |

||

|

H-4 |

Spouse or child of H-1B, H-1B1, H-2A, H-2B, or H-3 |

||

|

J-1 |

Exchange visitor |

||

|

J-2 |

Spouse or child of J-1 |

||

|

L-1 |

Intracompany transferee |

||

|

L-2 |

Spouse or child L-1 |

||

|

O-1 |

Person with extraordinary ability in the sciences, art, education, business, and athletics |

||

|

O-2 |

Person accompanying and assisting in the artistic or athletic performance by O-1 |

||

|

O-3 |

Spouse or child of O-1 or O-2 |

||

|

P-1 |

Internationally recognized athlete or member of an international recognized entertainment group |

||

|

P-2 |

Artist or entertainer in a reciprocal exchange program |

||

|

P-3 |

Artist or entertainer in a culturally unique program |

||

|

P-4 |

Spouse or child of P-1, P-2, or P-3 |

||

|

Q-1 |

Participant in an International Cultural Exchange Program |

||

|

R-1 |

Person in religious occupation |

||

|

R-2 |

Spouse or child of R-1 |

||

|

TN |

NAFTA professional |

||

|

TD |

Spouse or child of TN |

||

Source: U.S. Department of State and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Notes: Employment-based nonimmigrant visa classifications that have expired are not included in this table (e.g., H-1A, H-1C, H-2R, Q-1, Q-2, and NAFTA visas). CNMI stands for Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and NAFTA stands for the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report was originally written by Ruth Wasem, former CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. Adam Salazar, former research assistant, updated some of the statistics presented in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Temporary visas are issued for an expressed purpose and a specific period of time. In most cases, the foreign national must demonstrate they have a "home they have no intention of abandoning" in their native country. For more background on temporary visas, see CRS Report RL31381, U.S. Immigration Policy on Temporary Admissions. |

| 2. |

Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office, U.S. Department of State, Table XVI, multiple years. |

| 3. |

From December 2007 to June 2009, the economy experienced the longest and deepest recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. CRS Report R41578, Unemployment: Issues in the 113th Congress, by Jane G. Gravelle |

| 4. |

In FY2015, the total of 1,167,594 employment-based nonimmigrants included 179,497 temporary foreign workers in agriculture, seasonal or shortage occupations, or trainee positions. Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office 2015, U.S. Department of State, Table XVI, 2015. |

| 5. |

Bryan Baker, Estimates of the Size and Characteristics of the Resident Nonimmigrant Population in the United States: January 2012, U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Immigration Statistics, Population Estimates, February 2014. |

| 6. |

Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office 2012, U.S. Department of State, Table XVI, 2013. |

| 7. |

The INA bars the admission of employment-based lawful permanent residents who seek to enter the U.S. to perform skilled or unskilled labor, unless it is determined that (1) there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available; and (2) the employment of the alien will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed workers in the United States. |

| 8. |

Employers of those entering with H visas are generally required to have approved labor attestations, which includes H-2A temporary agricultural workers, and H-2B temporary nonagricultural workers as well as H-1B temporary professional workers. |

| 9. |

For a fuller discussion and analysis, see CRS Report R43223, The Framework for Foreign Workers' Labor Protections Under Federal Law and, CRS Report RL33977, Immigration of Foreign Workers: Labor Market Tests and Protections. |

| 10. |

For an in-depth discussion of the employment rates, see CRS Report R43476, Returning to Full Employment: What Do the Indicators Tell Us? |

| 11. |

For a fuller discussion of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, see CRS Report R42642, Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education: A Primer. |

| 12. |

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future, Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century, 2007; Brookings Institution and George Mason University, Immigration Policy: Highly Skilled Workers and U.S. Competitiveness and Innovation, Forum hosted by the Brookings Center for Technology Innovation and the George Mason Center for Science and Technology Policy, February 7, 2011; Vivek Wadhwa, Guillermina Jasso, and Ben Rissing, et al., Intellectual Property, the Immigration Backlog, and a Reverse Brain-Drain, part III, Duke University, New York University, Harvard Law School and the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, August 2007; U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, H-1B Visas: Designing a Program To Meet the Needs of the U.S. Economy and U.S. Workers, 112th Cong., 1st sess., March 31, 2011; U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, STEM the Tide: Should America Try to Prevent an Exodus of Foreign Graduates of U.S. Universities with Advanced Science Degrees?, 112th Cong., 1st sess., October 5, 2011; and, Mallie Jane Kim, "Chamber of Commerce, Bloomberg Push Immigration Reform," U.S. News & World Report, September 28, 2011. |

| 13. |

Richard Freeman, "The Market for Scientists and Engineers," NBER Reporter, no. 3 (Summer 2007); Rudy M. Baum, "Unemployment Data Worst In 40 Years," Chemical and Engineering News, March 21, 2012; U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees and Border Security, The Economic Imperative for Enacting Immigration Reform, answers to questions for the record, witness Professor Ron Hira, 112th Cong., 1st sess., July 26, 2011 U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, H-1B Visas: Designing a Program To Meet the Needs of the U.S. Economy and U.S. Workers, testimony of Professor Ron Hira, 112th Cong., 1st sess., March 31, 2011; and, U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, STEM the Tide: Should America Try to Prevent an Exodus of Foreign Graduates of U.S. Universities with Advanced Science Degrees, testimony of Dr. B. Lindsey Lowell, 112th Cong., 1st sess., October 5, 2011. |

| 14. |

U.S. General Accounting Office, H-1B Foreign Workers: Better Controls Needed to Help Employers and Protect Workers, GAO/HEHS-00-157, September 2000; U.S. General Accounting Office, H-1B Foreign Workers: Better Tracking Needed to Help Determine H-1B Program's Effects on U.S. Workforce, GAO-03-883, September 2003; and, U.S. Government Accountability Office, H-1B Visa Program: Reforms are Needed to Minimize the Risks and Costs of Current Program, GAO-11-26, January 14, 2011. |

| 15. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, H-1B Visa Program: Multifaceted Challenges Warrant Re-examination of Key Provisions, GAO-11-505T, March 31, 2011, p.2, http://www.gao.gov/assets/90/82421.pdf. |

| 16. |

Office of Fraud Detection and National Security, H-1B Benefit Fraud and Compliance Assessment, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, September 2008; and, U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, H-1B Visas: Designing a Program to Meet the Needs of the U.S. Economy and U.S. Workers, testimony of Donald Neufeld, USCIS Associate Director,112th Cong., 1st sess., March 31, 2011. |

| 17. |

Lisa Mascaro and Jim Puzzanghera, "Senators seek federal investigation of alleged H-1B visa abuse at Edison," The Los Angeles Times, April 9, 2015; Julia Preston, "Senator Seeks Inquiry Into Visa Program Used at Disney," The New York Times, June 4, 2015; and, Office of U.S. Senator Chuck Grassley, "Grassley, Durbin Push for H-1B and L-1 Visa Reforms," press release, November 15, 2015, http://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-durbin-push-h-1b-and-l-1-visa-reforms?et_rid=79443772&et_cid=106146. |

| 18. |

Shan Li and Matt Morrison, "Edison's plans to cut jobs, hire foreign workers is assailed," Los Angeles Times, February 10, 2015; Editorial Board, "End H-1B visa program's abuse," The Los Angeles Times, February 16, 2015. |

| 19. |

Julia Preston, "Toys 'R' Us Brings Temporary Foreign Workers to U.S. to Move Jobs Overseas," The New York Times, September 29, 2015; Julia Preston, "In Turnabout, Disney Cancels Tech Worker Layoffs," The New York Times, June 16, 2015; Julia Preston, "Senator Seeks Inquiry Into Visa Program Used at Disney," The New York Times, June 4, 2015; and Julia Preston, "Pink Slips at Disney. But First, Training Foreign Replacements," The New York Times, June 3, 2015. |

| 20. |

Spouses and children of L-1 visa holders may be issued the L-2 visa. |

| 21. |

Office of the Inspector General, Review of Vulnerabilities and Potential Abuses of the L-1 Visa Program, U.S. Department of Homeland Security , OIG-06-22, January 2006, p. 9, http://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/Mgmt/OIG_06-22_Jan06.pdf. |

| 22. |

Office of U.S. Senator Chuck Grassley, "Grassley, Durbin Push for H-1B and L-1 Visa Reforms," press release, November 15, 2015, http://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-durbin-push-h-1b-and-l-1-visa-reforms?et_rid=79443772&et_cid=106146. |

| 23. |

Stuart Anderson, L-1 Denial Rates for High Skilled Foreign Nationals Continue to Increase, National Foundation for American Policy, NFAP Policy Brief, March 2014. |

| 24. |

Stuart Anderson, L-1 Denial Rates for High Skilled Foreign Nationals Continue to Increase, National Foundation for American Policy, NFAP Policy Brief, March 2014. The Melmed quote is on page 3. |

| 25. |

For a fuller discussion and analysis, see CRS Report RL31381, U.S. Immigration Policy on Temporary Admissions. |

| 26. |

8 C.F.R. §214.2(h)(4). Law and regulations also specify that fashion models deemed "prominent" may enter on H-1B visas. |

| 27. |

For more on H-1B admissions, see CRS Report R42530, Immigration of Foreign Nationals with Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Degrees. |

| 28. |

INA §212(n); 8 C.F.R. §214.2(h)(4). For a further discussion of labor attestations, see CRS Report RL33977, Immigration of Foreign Workers: Labor Market Tests and Protections. |

| 29. |

The American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act (ACWIA) (Title IV of P.L. 105-277) defined H-1B dependent employers as follows: firms having 25 or less employees, of whom at least 8 are H-1Bs; firms having 26-50 employees of whom at least 13 are H-1Bs; firms having at least 51 employees, 15% of whom are H-1Bs; excludes those earning at least $60,000 or having masters degrees. |

| 30. |

INA §212(n). |

| 31. |

Title IV of the FY1999 Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act (P.L. 105-277). |

| 32. |

The American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-313). |

| 33. |

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2005 (P.L. 208-447) included the H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004. |

| 34. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Repot on H-1B Petitions, February, 16, 2016. |

| 35. |

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) maintains a timeline of the U.S. business cycle and declares when a recession begins and ends. According to the NBER, a peak was reached in December 2007, marking the end of the expansion that began in November 2001 and the beginning of the recession that ended in June 2009. CRS Report R40052, What is a Recession and Who Decided When It Started?, by Brian W. Cashell. |

| 36. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers, Fiscal Year 2014 Annual Report, Department of Homeland Security, February 26, 2015. |

| 37. |

§501 of P.L. 109-13, the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Defense, the Global War on Terror, and Tsunami Relief, 2005. |

| 38. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Foreign Physicians: Data on Use of J-1 Visa Waivers Needed to Better Address Physician Shortages, GAO-07-52, November 30, 2006, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-07-52. |

| 39. |

See CRS Report RL33844, Foreign Investor Visas: Policies and Issues. |

| 40. |

8 C.F.R. 214.2(o)(3)(ii). |

| 41. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, "Special Immigrant and Nonimmigrant Religious Workers," 73 Federal Register, 72276, November 26, 2008. |

| 42. |

Bureau of Consular Affairs, Report of the Visa Office 2013, U.S. Department of State, Table XVI, 2015. |

| 43. |

U.S. Department of State, "J-1 Visa Exchange Visitor Program, Summer Work Travel Program," available at http://j1visa.state.gov/programs/summer-work-travel (visited May 14, 2014). |

| 44. |

For a more complete discussion, see CRS Report R42434, Immigration of Temporary Lower-Skilled Workers: Current Policy and Related Issues. |

| 45. |

Students on F visas are permitted to work in practical training that relates to their degree program, such as paid research and teaching assistantships. 8 C.F.R. 214.2(f)(15)(i). |

| 46. |

The F-1 visa is the most common visa for foreign students and it is tailored for international students pursuing a full-time academic education. Spouses and children may accompany an F-1 visa holder on F-2 visas, but are not permitted to work. |

| 47. |

E-Verify is an electronic employment eligibility verification program that U.S. employers voluntarily use to confirm the new hires' employment authorization through Social Security Administration and, if necessary, DHS databases. CRS Report R40446, Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification. |

| 48. |

8 C.F.R. 214.2(f)(10). |

| 49. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Memorandum to Leon Rodriquez, Director, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and Thomas S. Winkowski, Acting Director, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, from Jeh Charles Johnson, Secretary of Homeland Security, Policies Supporting U.S. High-Skilled Business and Workers, November 20, 2014. |

| 50. |

The proposed rule also includes the "Cap-Gap" policy initially implemented in 2008 for any F-1 student with a pending H-1B petition. This proposal allows such students to automatically extend the duration of F-1 status and any current employment authorization until October 1 of the fiscal year for which such H-1B visa is being requested. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Improving and Expanding Training Opportunities for F–1 Nonimmigrant Students With STEM Degrees and CapGap Relief for All Eligible F–1 Students," 80 Federal Register 63376-63404, October 19, 2015. |

| 51. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Student and Exchange Visitor Program: DHS Needs to Assess Risks and Strengthen Oversight of Foreign Students with Employment Authorization, GAO-14-356, February 27, 2014, p. 18, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-356. |

| 52. |

For a full discussion of the taxation of noncitizens, see CRS Report RS21732, Federal Taxation of Aliens Working in the United States. |

| 53. |

Foreign students who wish to pursue a nonacademic (e.g., vocational) course of study apply for an M visa rather than the F visa. The Q visa is an employment-oriented cultural exchange program, and its stated purpose is to provide practical training and employment as well as share history, culture, and traditions. CRS Report RL31381, U.S. Immigration Policy on Temporary Admissions. |

| 54. |

Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Tax Guide for Aliens, Publication 519, January 21, 2014, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p519.pdf, pp. 4-5. |

| 55. |

For more information on the ACA individual mandate, see Internal Revenue Service, Affordable Care Act Tax Provisions for Individuals and Families, May 15, 2014, http://www.irs.gov/uac/Affordable-Care-Act-Tax-Provisions-for-Individuals-and-Families; and, CRS Report R41331, Individual Mandate Under the ACA, by Annie L. Mach. |

| 56. |

For a fuller discussion of whether they are eligible to receive benefits under these programs, see CRS Report RL32004, Social Security Benefits for Noncitizens. |

| 57. |

Internal Revenue Service, Background Information on the Final Regulations and Revenue Procedure Providing Guidance on the Student FICA Exception (Section 3121(b)(10) of the Internal Revenue Code), U.S. Department of Treasury, December 21, 2004, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/student_fica_-_background_info_7-28-05.pdf. |

| 58. |

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research et al. v. United States, 09–837 (2011). |

| 59. |

20 C.F.R. 404.1001, 404.1012, 404.1028 and 404.1036. |

| 60. |

Section 210(a)(19) of the Social Security Act. |

| 61. |

Internal Revenue Service, Social Security/Medicare and Self-Employment Tax Liability of Foreign Students, Scholars, Teachers, Researchers, and Trainees, December 4, 2013, http://www.irs.gov/Individuals/International-Taxpayers/Foreign-Student-Liability-for-Social-Security-and-Medicare-Taxes. |

| 62. |

More specifically, §3121(b) of the I.R.C. Wages may also be exempt from FICA pursuant to totalization agreements authorized by section 233 of the Social Security Act. 26 U.S.C. §3101(c). For more information, see Internal Revenue Service, Totalization Agreements, August 2, 2013, http://www.irs.gov/Individuals/International-Taxpayers/Totalization-Agreements; and CRS Report RL32004, Social Security Benefits for Noncitizens, by Dawn Nuschler and Alison Siskin. |

| 63. |

Not all companies, however, seek to convert H-1B employees to LPR status. Research by Professor Ron Hira of the Rochester Institute of Technology indicates that many of the largest users of the H-1B visa sponsor few, if any, of their H-1Bs for permanent residency. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees and Border Security, The Economic Imperative for Enacting Immigration Reform, 112th Cong., 1st sess., July 26, 2011. |

| 64. |

Ruth Ellen Wasem, "Global Competition for Talent: Parameters of and Trends in U.S. Economic Migration," Center for the History of the New America Conference on Immigration & Entrepreneurship, University of Maryland, MD, September 14, 2012. |

| 65. |

Ibid. |

| 66. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Extension of Post-Completion Optional Practical Training (OPT) and F-1 Status for Eligible Students under the H-1B Cap-Gap Regulations, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, April 2, 2010. |

| 67. |

Not all companies, however, seek to convert H-1B employees to LPR status. Research by Professor Ron Hira of the Rochester Institute of Technology indicates that many of the largest users of the H-1B visa sponsor few, if any, of their H-1Bs for permanent residency. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees and Border Security, The Economic Imperative for Enacting Immigration Reform, 112th Cong., 1st sess., July 26, 2011. |

| 68. |

The other categories permitted dual intent are intracompany transfers employed with international firms who enter on L visas and foreign nationals with V visas for family-related nonimmigrant. §214(b) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1184(b). |

| 69. |

§214(b) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1184(b). |

| 70. |

Ruth Ellen Wasem, "Global Competition for Talent: Parameters of and Trends in U.S. Economic Migration," Center for the History of the New America Conference on Immigration & Entrepreneurship, University of Maryland, MD, September 14, 2012. |