Introduction

The 116th Congress, in both its legislative and oversight capacities, faces numerous trade policy issues related to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) renegotiations and the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).1 On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate and modernize NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA).2 Talks officially began on August 16, 2017. On September 30, 2018, leaders from the United States, Canada, and Mexico announced the conclusion of the negotiations for a modernized NAFTA, which would now be called the USMCA. On November 30, 2018, the proposed USMCA was signed by President Donald J. Trump, then President Enrique Peña Nieto of Mexico, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. President Trump stated his intention to withdraw from or renegotiate NAFTA during his election campaign and has hinted at the possibility of NAFTA withdrawal since he entered into office.

|

Joint Statement on Proposed USMCA "Today, Canada and the United States reached an agreement, alongside Mexico, on a new, modernized trade agreement for the 21st Century: the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). USMCA will give our workers, farmers, ranchers and businesses a high-standard trade agreement that will result in freer markets, fairer trade and robust economic growth in our region. It will strengthen the middle class, and create good, well-paying jobs and new opportunities for the nearly half billion people who call North America home. "We look forward to further deepening our close economic ties when this new agreement enters into force. "We would like to thank Mexican Economy Secretary Ildefonso Guajardo for his close collaboration over the past 13 months." Joint Statement from United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland, September 30, 2018. Source: USTR, at https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases. |

Key issues for Congress in regard to the consideration of the proposed USMCA include the constitutional authority of Congress over international trade, its role in revising, approving, or withdrawing from the agreement, U.S. negotiating objectives and the extent to which the proposed agreement makes progress in meeting them as required under TPA. Congress may also consider the agreement's impact on U.S. industries, the U.S. economy, and broader U.S. trade relations with Canada and Mexico, two of the United States' largest trading partners.

The proposed USMCA, if approved by Congress, would revise some key provisions such as auto rules of origin, which, some argue roll back longstanding U.S. FTA provisions. On the other hand, it establish new updated provisions in areas such as digital trade and intellectual property rights. A key question for Congress may be whether the agreement strikes the right balance overall.

After numerous rounds of negotiations, on August 31, 2018, after the United States and Mexico announced a preliminary U.S.-Mexico agreement, President Trump notified Congress of his intention to "enter into a trade agreement with Mexico – and with Canada if it is willing."3 On September 30, 2018, U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Robert Lighthizer announced that the three countries had reached an agreement on a USMCA trade deal that would revise, modernize, and replace NAFTA upon ratification.4

Canada, in its negotiating objectives, pledged to make NAFTA more "progressive" by strengthening labor and environmental provisions, adding a new chapter on indigenous rights, reforming the investor-state dispute settlement process, and protecting Canada's supply-management system for dairy and poultry, among other objectives.5 Mexico's set of negotiating objectives prioritized free trade of goods and services, and included provisions to update NAFTA, such as working toward "inclusive and responsible" trade by incorporating cooperation mechanisms in areas related to labor standards, anticorruption, and the environment, as well as strengthening energy security by enhancing NAFTA's chapter on energy.6

While the USTR's NAFTA negotiating objectives included many goals consistent with TPA, USTR also sought, for the first time in U.S. trade negotiations, to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with NAFTA countries, among other specific objectives. U.S. objectives appeared to seek to "rebalance the benefits" of the agreement, echoing President Trump's statements that NAFTA has been a "disaster" and the "worst agreement ever negotiated."7 Some U.S. negotiating positions could be seen to have the explicit or implicit goal of promoting U.S. economic sovereignty and/or rolling back previous liberalization commitments in specific areas, such as reviewing and potentially sunsetting the agreement every five years, questioning the validity of binational dispute settlement, enhancing government procurement restrictions, and increasing U.S. and North American content in the auto rules of origin.8 Trump Administration officials also spoke of unraveling the North American and global supply chains as a way of attempting to divert trade and investment from Canada and Mexico to the United States.9 Mexican and Canadian negotiators viewed such proposals as counterproductive to the spirit and mutual economic benefits of NAFTA and repeated their positions to modernize NAFTA with provisions such as those in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The differences between views on modernizing the agreement and U.S. proposals led to perceived tensions in the negotiations.

The proposed USMCA presents an opportunity to incorporate elements of more recent FTAs that have entered into force or were negotiated, such as the U.S.-Korea FTA (KORUS) and the proposed TPP. The U.S. and global economies have changed significantly since NAFTA entered into force 25 years ago, especially due to technology advances. The widespread use of the commercial internet, for example, has dramatically affected consumer habits, commercial activities such as e-commerce and supply chain management. Negotiators also sought updated provisions in other areas such as intellectual property rights (IPR), labor, and the environment. The increased role of state-led or supported firms in trade competition with private sector firms is also a new issue of debate and focus of new rules-setting.

Many economists and business representatives generally look to maintain and strengthen the trade and investment relationship with Canada and Mexico under NAFTA or the proposed USMCA, and to further improve overall relations and economic integration within the region. However, labor groups and some consumer-advocacy groups argue that NAFTA resulted in outsourcing and lower wages that have had a negative effect on the U.S. economy. Some proponents and critics of NAFTA agree that NAFTA should be modernized, but have contrasting views on how to revise the agreement.

This report provides a brief overview of NAFTA and the role of Congress in the renegotiation process, and discusses key provisions in the proposed USMCA, as well as issues related to the negotiations. It also provides a discussion of policy implications for Congress going forward. It will not examine existing NAFTA provisions and economic relations in depth. For more information on these issues, please see CRS Report R42965, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by M. Angeles Villarreal and Ian F. Fergusson.

NAFTA Overview

NAFTA negotiations were first launched under President George H. W. Bush. President William J. Clinton signed into law the NAFTA Implementation Act on December 8, 1993 (P.L. 103-182). NAFTA entered into force on January 1, 1994. It is significant because it was the first FTA among two wealthy countries and a lower-income country and because it established trade liberalization commitments that led the way in setting new rules for future trade agreements on issues important to the United States. These include provisions on intellectual property rights (IPR) protection, services trade, agriculture, dispute settlement procedures, investment, labor, and the environment. NAFTA addressed policy issues that were new to FTAs and was influential in concluding major multilateral trade negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO). The United States now has 14 FTAs with 20 countries.

NAFTA's market-opening provisions gradually eliminated nearly all tariff and most nontariff barriers on goods and services produced and traded within North America. At the start of NAFTA, average applied U.S. duties on imports from Mexico were 2.07% and over 50% of U.S. imports from Mexico entered duty free.10 In contrast, the United States faced higher tariff, nontariff, and investment barriers in Mexico.11 Trade among NAFTA partners has more than tripled since the agreement entered into force, forming integrated production chains among all three countries. Many trade policy experts and economists give credit to NAFTA for expanding trade and economic linkages among the parties, creating more efficient production processes, increasing the availability of lower-priced and greater choice of consumer goods, and improving living standards and working conditions.12 Others blame NAFTA and subsequent U.S. FTAs for disappointing employment trends, a decline in average U.S. wages, and for not having done enough to improve labor standards and environmental conditions abroad.13

Another important element of NAFTA is that it helped "lock in" trade and investment liberalization efforts taking place at the time, especially in Mexico. NAFTA was instrumental in developing closer U.S. relations with both Mexico and Canada and it may have accelerated ongoing trade and investment trends. At the time that NAFTA was implemented, the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA) was already in effect and U.S. tariffs on most Mexican goods were low, while Mexico had the highest level of trade barriers among the three countries. From the 1930s through part of the 1980s, Mexico maintained a strong protectionist trade policy in an effort to be independent of any foreign power and as a means to promote domestic-led industrialization.14 In 1991, for example, U.S. businesses were very restricted in investing in Mexico. Under Mexico's restrictive Law to Promote Mexican Investment and Regulate Foreign Investment, about a third of Mexican economic activity was not open to majority foreign ownership.15 Mexico's failed protectionist policies did not result in increased income levels or economic growth, and the income disparity with the United States remains large, even after NAFTA.

|

Mexico |

Canada |

United States |

||||

|

1994 |

2017 |

1994 |

2017 |

1994 |

2017 |

|

|

Population (millions) |

92 |

129 |

29 |

37 |

263 |

327 |

|

Nominal GDP (US$ billions)a |

508 |

1,148 |

548 |

1,627 |

7,309 |

19,371 |

|

Nominal GDP, PPP Basis (US$ billions)b |

790 |

2,372 |

654 |

1,671 |

7,309 |

19,371 |

|

Per Capita GDP (US$) |

5,499 |

8,890 |

19,914 |

44,415 |

27,777 |

59,332 |

|

Per Capita GDP in $PPP |

8,555 |

18,370 |

22,531 |

45,630 |

27,777 |

59,330 |

|

Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) |

14% |

37% |

33% |

31% |

10% |

12% |

|

Imports of goods and services (% of GDP) |

18% |

39% |

32% |

34% |

11% |

15% |

Source: Compiled by CRS based on data from Economist Intelligence unit (EIU) online database.

Notes: Some figures for 2017 are estimates.

a. Nominal GDP is calculated by EIU based on figures from World Bank and World Development Indicators.

b. PPP refers to purchasing power parity, which reflects the purchasing power of foreign currencies in U.S. dollars.

NAFTA coincided with Mexico's unilateral trade liberalization efforts. After NAFTA, the United States and Canada gained greater access to the Mexican market, which was the fastest-growing major export market for U.S. goods and services at the time.16 NAFTA also opened up the U.S. market to increased imports from Mexico and Canada, creating one of the largest free trade areas in the world. Since NAFTA, the three countries have made efforts to cooperate on issues of mutual interest, including trade and investment, and also in other, broader aspects of the relationship, such as regulatory cooperation, industrial competitiveness, trade facilitation, border environmental cooperation, and security.

Key NAFTA Provisions

Some key NAFTA provisions include tariff and nontariff trade liberalization, rules of origin, commitments on services trade and foreign investment, IPR protection, government procurement rules, and dispute resolution. Labor and environmental provisions are included in separate NAFTA side agreements. NAFTA provisions and rules governing trade were groundbreaking in a number of areas, particularly in regard to enforceable rules and disciplines that were included in a trade agreement for the first time. There were almost no FTAs in place worldwide at the time, and NAFTA influenced subsequent agreements negotiated by the United States and other countries, especially at the multilateral level in light of the then-pending Uruguay Round of major multilateral trade liberalization negotiations.

The market-opening provisions of the agreement gradually eliminated nearly all tariffs and most nontariff barriers on goods produced and traded within North America, mostly over a period of 10 years after it entered into force. Some tariffs were eliminated immediately, while others were phased out in various schedules of 5 to 15 years. Most of the market-opening measures from NAFTA resulted in the removal of tariffs and quotas applied by Mexico on imports from the United States and Canada. The average applied U.S. duty17 for all imports from Mexico was 2.07% in 1993.18 Moreover, many Mexican products entered the United States duty-free under the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). In 1993, over 50% of U.S. imports from Mexico entered the United States duty-free. In contrast, the United States faced considerably higher tariffs and substantial nontariff barriers on exports to Mexico. In 1993, Mexico's average applied tariff on all imports from the United States was 10% (Canada's average tariff on U.S. goods was 0.37%).19 Non-tariff barriers also affected U.S.-Mexico trade, such as sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) rules, Mexican import licensing requirements, and U.S. marketing orders.20 The market opening that occurred after NAFTA is likely a factor in the significance of trade for Mexico's economy. In 1994, Mexico's exports and imports equaled 14% and 18%, respectively, of GDP, while in 2017, these percentages increased to 37% and 39%. For the United States, trade is less significant for the economy, with the value of imports and exports equaling 15% and 12%, respectively, of GDP in 2017 (see Table 1).

NAFTA rules, disciplines and nontariff provisions include the following:

- Agriculture. NAFTA eliminated tariffs and tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) on most agricultural products. It maintains TRQs with high over-quota tariffs for U.S. exports of dairy, poultry, and egg products to Canada. NAFTA addressed sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and other types of agricultural non-tariff barriers. SPS regulations are often regarded by agricultural exporters as one of the greatest challenges in trade, often resulting in increased costs and product loss and disrupting integrated supply chains.21

- Investment. NAFTA removed significant investment barriers in Mexico, ensured basic protections for NAFTA investors, and provided a mechanism for the settlement of disputes between investors and a NAFTA country. NAFTA provided for national and "nondiscriminatory treatment" for foreign investment by NAFTA parties in certain sectors of other NAFTA countries. The agreement included country-specific liberalization commitments and exceptions to national treatment. Exemptions from NAFTA included the energy sector in Mexico, in which the Mexican government reserved the right to prohibit private investment or foreign participation.

- Services Trade. NAFTA services provisions established a set of basic rules and obligations in services trade among partner countries. The agreement granted services providers certain rights concerning nondiscriminatory treatment, cross-border sales and entry, investment, and access to information. However, there were certain exclusions and reservations by each country. These included maritime shipping (United States), film and publishing (Canada), and oil and gas drilling (Mexico).22 NAFTA liberalized certain service sectors in Mexico, particularly financial services, which significantly opened its banking sector.23

- Financial and Telecommunications Services. Under NAFTA, Canada extended an exemption granted to the United States, under the CUSFTA, to Mexico in which Mexican banks would not be subject to Canadian investment restrictions. In turn, Mexico agreed to permit financial firms from another NAFTA country to establish financial institutions in Mexico, subject to certain market-share limits applied during a transition period ending by the year 2000. In telecommunications, NAFTA partners agreed to exclude provision of, but not the use of, basic telecommunications services. NAFTA granted a "bill of rights" for the providers and users of telecommunications services, including access to public telecommunications services; connection to private lines that reflect economic costs and available on a flat-rate pricing basis; and the right to choose, purchase, or lease terminal equipment best suited to their needs.24 NAFTA did not require parties to authorize a person of another NAFTA country to provide or operate telecommunications transport networks or services. Nor did it bar a party from maintaining a monopoly provider of public networks or services, such as Telmex, Mexico's dominant telecommunications company.25

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Protection. NAFTA was the first U.S. FTA to include IPR protection provisions. It built upon the then-ongoing Uruguay Round negotiations that would create the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement in the WTO and on various existing international intellectual property treaties. The agreement set specific enforceable commitments by NAFTA parties regarding the protection of copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, among other provisions.

- Dispute Resolution. NAFTA's provisions for preventing and settling disputes regarding enforcement of commitments under the agreement were built upon provisions in the CUSFTA. NAFTA created a system of arbitration for resolving disputes that included initial consultations, taking the issue to the NAFTA Trade Commission, or going through arbitral panel proceedings.26 NAFTA included separate dispute settlement provisions for addressing disputes related to investment and over antidumping and countervailing duty determinations.

- Government Procurement. NAFTA opened up a significant portion of federal government procurement in each country on a nondiscriminatory basis to suppliers from other NAFTA countries for goods and services. It contains some limitations for procurement by state-owned enterprises.

- Labor and Environment. NAFTA marked the first time that labor and environmental provisions were associated with an FTA. For many, it represented an opportunity for establishing a new type of relationship among NAFTA partners.27 Labor and environmental provisions were included in separate side agreements. They included language to promote cooperation on labor and environmental matters as well as provisions to address a party's failure to enforce its own labor and environmental laws. Perhaps most notable were the side agreements' dispute settlement processes that, as a last resort, may impose monetary assessments and sanctions to address a party's failure to enforce its laws.

Trade Trends

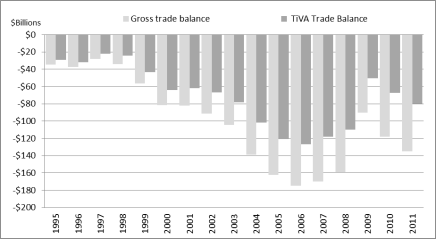

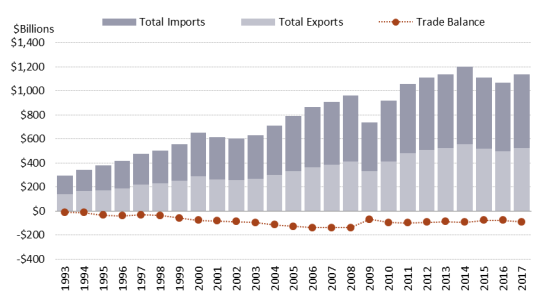

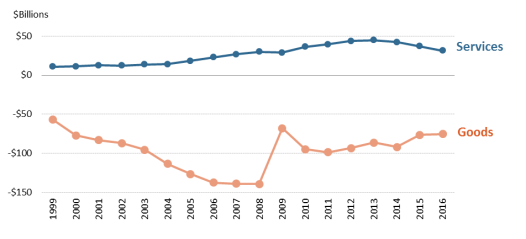

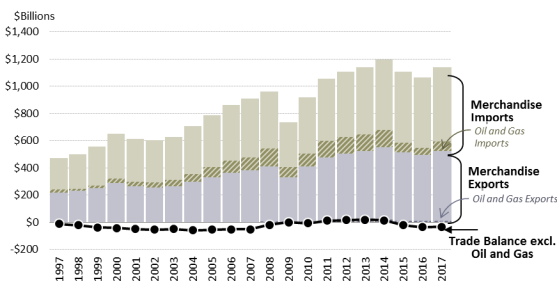

U.S. trade with NAFTA partners increased rapidly once the agreement took effect, increasing more rapidly than trade with most other countries. U.S. total merchandise imports from NAFTA partners increased from $151 billion in 1993 to $614 billion in 2017 (307%), while merchandise exports increased from $142 billion to $525 billion (270%) (see Figure 1). The United States had a trade deficit with Canada and Mexico of $89.6 billion in 2017, compared to a deficit of $9.1 billion in 1993. Services trade with NAFTA partners has also increased. The United States had a services trade surplus with Canada and Mexico of $31.4 billion in 2016 (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. U.S. Merchandise Trade with NAFTA Partners: 1993-2017 (billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission's Interactive Tariff and Trade Data Web, at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. |

|

Figure 2. U.S. Services and Merchandise Trade Balance with NAFTA Partners (billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis at http://www.bea.gov and the U.S. International Trade Commission's (USITC's) Interactive Tariff and Trade Data Web, at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. |

Trade in Oil and Gas

Trade in oil and gas is a significant component of trilateral trade, accounting for 7.2% of total U.S. merchandise trade with Canada and Mexico in 2017. As shown in Figure 3, U.S. oil and gas exports to Canada and Mexico increased from $0.9 billion in 1997 to $13.4 billion in 2017, while imports increased from $22.3 billion to $69.0 billion. If oil and gas products are excluded from the trade balance, the deficit with NAFTA partners is lower than the overall trade deficit. In 2017, the total U.S. merchandise trade deficit with Canada and Mexico was $88.6 billion, while the merchandise deficit without oil and gas products was a significantly lower $33.0 billion.28

|

Figure 3. U.S. Merchandise and Oil and Gas Trade with NAFTA Partners (1997-2017) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission's Interactive Tariff and Trade Data Web, at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. Notes: Oil and gas trade data are at the NAIC 3-digit level, code 211, which include activities related to exploration for crude petroleum and natural gas; drilling, completing, and equipping wells; operating separators, emulsion breakers, desilting equipment, and field gathering lines for crude petroleum and natural gas; and other activities. |

Trade in Value Added

Conventional measures of international trade do not always reflect the flows of goods and services within global production chains. For example, some auto trade experts claim that auto parts and components may cross the borders of NAFTA countries as many as eight times before being installed in a final assembly plant in a NAFTA country.29 Traditional trade statistics include the value of the parts every time they cross the border and count the value multiple times. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) developed a Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database, which presents indicators that provide insight into domestic and foreign value added content of gross exports by an exporting industry.30 These statistics provide a more detailed picture of the location where value is added during the various stages of production. U.S. trade with Canada and Mexico is diverse and complex since a final good sold in the market could have a combination of value added from all three countries, or from other trading partners. The most recent TiVA data available (2011) for trade in goods and services indicate that the conventional measurement puts the total U.S. trade deficit (including goods and services) with NAFTA countries at $135 billion, while the TiVA methodology puts the deficit at $79.8 billion (see Figure 4).

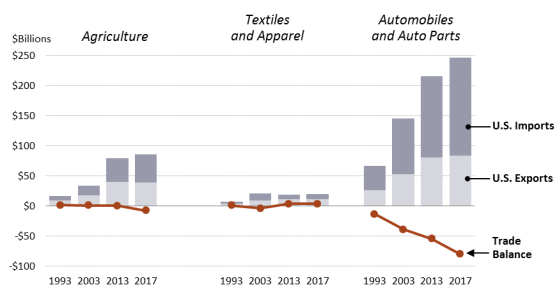

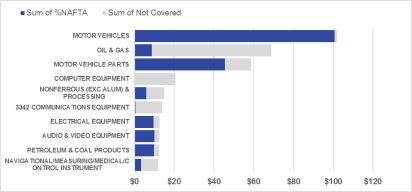

Merchandise Trade in Selected Industries

NAFTA removed Mexico's protectionist policies in the auto sector and was instrumental in the integration of the motor vehicle industry in all three countries. The sector experienced some of the most significant changes in trade following the agreement. Motor vehicles and motor vehicle parts rank first among leading exports to and imports from NAFTA countries as shown in Figure 5. Agriculture trade also expanded after NAFTA, but to a lesser degree than the motor vehicle industry. The trade balance in agriculture also has a far lower trade deficit. Trade trends by sector indicate that NAFTA achieved many of the trade and economic benefits that proponents claimed it would bring, although there have been adjustment costs. It is difficult to isolate the effects of NAFTA to quantify the effects on trade in specific industries because other factors, such as economic growth and currency fluctuations, also affect trade.

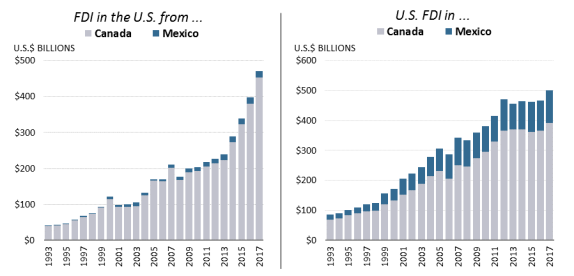

U.S. Investment with Canada and Mexico

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been an integral part of the economic relationship between the United States and NAFTA partners for many years. Two-way investment between Canada and the United States has increased markedly since NAFTA, both in terms of the stock and flow of investment. The United States is the largest single investor in Canada with a stock of FDI into Canada reaching $391.2 billion in 2017, up from a stock of $69.9 billion in 1993 (see Figure 6). U.S. investment represents about half of the total stock of FDI in Canada from global investors. The United States was the largest destination for Canadian FDI in 2017 with a stock of $453.1 billion, a significant increase from $40.4 billion in 1993. These trends highlight the changing view of FDI among Canadians, from one that could be considered fearful or hostile to FDI as vehicles of foreign control over the Canadian economy, to one that is more welcoming of new jobs and technologies that result from FDI.

In Mexico, the United States is the largest source of FDI. The stock of U.S. FDI in Mexico increased from $15.2 billion in 1993 to $109.7 billion in 2017 (see Figure 6). Total FDI in Mexico dropped 19% in 2015, mainly due to a decline in investment in the services sector and automotive industry. Other countries in Latin America also experienced similar declines in FDI in 2015. Some economists contend that Mexico's recent economic reforms have added resilience to the Mexican economy and that greater economic growth and investment in Mexico would occur over time as a result.31 Mexican FDI in the United States, while substantially lower than U.S. investment in Mexico, has also increased rapidly, from $1.2 billion in 1993 to $18.0 billion in 2017.32

|

Figure 6. Foreign Direct Investment Positions Among NAFTA Partners (historical-cost basis) |

|

|

Source: CRS based on data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

NAFTA Renegotiation Process and TPA

Under Article II of the Constitution, the President has the authority, with the advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties. Under Article I, Section 8, Congress has the authority to lay and collect duties, and to regulate foreign commerce. The President may seek expedited treatment of the implementing legislation of a renegotiated NAFTA under the Bipartisan Comprehensive Trade Promotion and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA).33 NAFTA provides, "The Parties may agree on any modification of or addition to this Agreement. When so agreed, and approved in accordance with the applicable legal procedures of each party, a modification or addition shall constitute an integral part of the agreement."34

Under TPA, the President must consult with Congress before giving the required 90-day notice of his intention to start negotiations.35 The Trump Administration's consultations included meetings between U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and members of the House Ways and Means Committee and Senate Finance Committee and with members of the House and Senate Advisory Groups on Negotiations.36 The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) held public hearings and has received more than 12,000 public comments on NAFTA renegotiation.37

In order to use the expedited procedures of TPA, the President must notify and consult with Congress before initiating and during negotiations, and adhere to several reporting requirements following the conclusion of any negotiations resulting in an agreement. The President must conduct the negotiations based on the negotiating objectives set forth by Congress in the 2015 TPA authority. See box below for the dates on which these requirements were or are expected to be met.

|

TPA: Key TPA Dates and Deadlines for USMCA |

|

Trade Deficit Reduction

The Trump Administration, for the first time in the negotiating objectives of an FTA, indicated its aim to improve the U.S. trade balance and reduce the trade deficit with NAFTA countries in the renegotiation of NAFTA.38 The trade balance with NAFTA partners has fluctuated since the agreement entered into force, increasing from $9.1 billion in 1993 to $89.6 billion in 2017. President Trump and some officials within his Administration believe that trade deficits are detrimental to the U.S. economy.39 USTR Robert Lighthizer stated after the second round of negotiations that while he wanted to negotiate an agreement that is approved by Congress, he also wanted to bring down the trade deficit, as part of his mission, in order to help American workers and farmers.40 Other critics of NAFTA also argue that U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) have contributed to rising trade deficits with some trade partners.41

Economists generally argue that it is not feasible to use trade agreement provisions as a tool to decrease the deficit because trade imbalances are determined by underlying macroeconomic fundamentals, such as a savings-investment imbalance in which the demand for capital in the U.S. economy outstrips the amount of gross savings supplied by households, firms, and the government sector.42 According to some economists, a more constructive alternative would be to help strengthen Mexico's economy and boost Mexico's imports from the United States.43 Others contend that FTAs are likely to affect the composition of trade among trade partners, but have little impact on the overall size of the trade deficit.44 They argue that trade balances are incomplete measures of the comprehensive nature of economic relations between the United States and its trading partners, and maintain that trade imbalances are determined by macroeconomic fundamentals and not by trade policy.45

From this perspective, it is not clear how the Administration would expect to reduce the trade deficit through the proposed USMCA.

Proposed USMCA

The proposed USMCA, comprising 34 chapters and 12 side letters, retains most of NAFTA's chapters, making notable changes to market access provisions for autos and agriculture products, and to rules and disciplines, such as on investment, government procurement, and IPR. New issues, such as digital trade, state-owned enterprises, anticorruption, and currency misalignment, are also addressed. Because NAFTA is 25 years old, the proposed USMCA could be viewed as an opportunity to include obligations not currently covered in the original text, such as digital trade or more enforceable labor and environmental provisions. The following selective topics provide an overview of proposed USMCA provisions and a comparison to existing NAFTA provisions.

Rules of Origin

Rules of origin in NAFTA and other FTAs help ensure that the benefits of the FTA are granted only to goods produced by the parties that are signatories to the FTAs rather than to goods made wholly or in large part in other countries. If a U.S. import does not meet NAFTA rules-of-origin requirements, it will enter the United States under another import program or at U.S. MFN tariff rates. In 2017, 53% of U.S. imports from Canada and Mexico entered duty-free under NAFTA, while 47% entered under normal trade relations.46 In the case of NAFTA, most goods that contain materials from non-NAFTA countries may also be considered as North American if the materials are sufficiently transformed in the NAFTA region to go through a Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) change in tariff classification (called a "tariff shift"). In many cases, goods must have a minimum level of North American content in addition to undergoing a tariff shift. Regional value content may be calculated using either the "transaction-value" or the "net-cost" method. The transaction-value method, which is simpler, is based on the price of the good, while the net-cost method is based on the total cost of the good less the costs of royalties, sales promotion, and packing and shipping. Producers generally have the option to choose which method they use, with some exceptions, such as the motor vehicle industry, which must use the net-cost method.47

The U.S. proposal on tightening rules of origin in the motor vehicle industry was viewed as one of the more contentious issues in the negotiations. Please see section below on the "Motor Vehicle Industry" for a discussion of the auto rules of origin.

NAFTA's rules of origin requirements state that if the transaction value method is used, not less than 60 per cent if the good must be of North American content for a good to receive NAFTA benefits. If the net cost method is used, not less than 50 percent if the value of the good must be of North American content. The proposed USMCA maintains these percentages for general imports. As noted below, certain industries such as the motor vehicle industry have specific rules of origin requirements.

Motor Vehicle Industry

NAFTA phased out U.S. tariffs on motor vehicle imports from Mexico and Mexican tariffs on U.S. and Canadian products as long as they met the rules of origin requirements of 62.5% North American content for autos, light trucks, engines and transmissions; and 60% for automotive parts. Some tariffs were eliminated immediately, while others were phased out in periods over 5 to 10 years. The agreement phased out Mexico's restrictive auto decrees, which for many years imposed high import tariffs and investment restrictions in Mexico's auto sector, and opened the Mexican motor vehicle sector to trade with and investment from the United States.48

NAFTA and the elimination of Mexican trade barriers liberalized North American motor vehicle trade and was instrumental in the integration of the North American motor vehicle industry.49 North American motor vehicle manufacturing is now highly integrated, with major Asia- and Europe-based automakers constructing their own supply chains within the region.50 The major recent growth in the North American market occurred largely in Mexico, which now accounts for about 20% of total continental vehicle production.51 In general, recent investments in U.S. and Canadian assembly plants have involved modernization or expansion of existing facilities, while Mexico has seen new assembly plants.52

The proposed USMCA would tighten auto rules of origin by including

- new motor vehicle rules of origin and procedures, including product-specific rules, and requiring 75% North American content;

- for the first time in a trade agreement, wage requirements stipulating 40%-45% of North American auto content be made by workers earning at least $16 per hour;

- a requirement that 70% of a vehicle's steel and aluminum must originate in North America; and

- a provision aiming to streamline the enforcement of manufacturers' rules of origin certification requirements.

In addition, side letters would exempt from potential Section 232 tariffs, which are being investigated by the Department of Commerce53, the following items from Canada and Mexico:

- 2.6 million passenger vehicles each from Canada and Mexico on an annual basis;

- light trucks imported from Canada or Mexico; and

- auto part imports amounting to U.S. $32.4 billion from Canada and U.S. $108 billion from Mexico in declared customs value in any calendar year.

During the negotiations, vehicle and parts manufacturers generally supported retaining the current rules of origin under NAFTA, whereas labor groups sought to require a higher percentage of regional content, which they believe would reduce the share of parts produced in non-NAFTA countries. Some observers state that "it is unclear" whether the auto rules of origin in the proposed USMCA meet the requirements under the World Trade Organization's Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.54 Article XXIV states that duties and other commerce regulations between parties of a customs union "should not on the whole be higher or more restrictive" than the rate of the duties and regulations "applicable in the constituent territories prior to the formation of such union."55

Some economists and other experts believe that the higher North American content requirement in the proposed USMCA could have unintended consequences. They contend that trade in motor vehicles within North America may not be able to meet the new requirements and would be ineligible for USMCA benefits. Such experts say that it would be more cost efficient for manufacturers of motor vehicles and motor vehicle parts to pay the MFN tariff56 of about 2.5%, rather than meet the cumbersome rules-of-origin requirements. They argue that a change in rules poses a significant risk to North American auto production, because it is likely that manufacturers would not have the supply to meet the new rules and would not be able to remain competitive in the market.57 Auto manufacturers in Mexico are concerned that they may lose market share to Asian manufacturers.58 For example, because the rules of origin in the U.S.-South Korea FTA are much lower than those in the USMCA, it is possible that motor vehicle producers would shift production to South Korea, especially in light trucks.59

Even with these concerns, motor vehicle producers, in general, support the conclusion of the negotiations for the proposed USMCA and its ratification. Some automakers say that complying with the new rules of origin may be cumbersome, but probably manageable. Some also contend that production in the United States has the potential to increase under the agreement, although it is not clear whether this would translate into more U.S. jobs.60 Auto industry representatives reacted favorably to the conclusion of the negotiations and generally agree with changes modernizing the agreement, such as updating border customs procedures (i.e., trade facilitation measures), digital trade provisions, and IPR protection.61

The United Auto Workers union (UAW) called for the renegotiation of NAFTA to provide more benefits to workers in all three signatory countries.62 The UAW supports a strengthening of labor and environmental provisions, ensuring "fair" trade among all NAFTA parties through more enforceable provisions, and enhancing provisions on worker rights protection.63 After the announcement of the proposed USMCA, the UAW issued a statement that it would need time to evaluate the details of the agreement before determining whether the "agreement will protect our UAW jobs and the living standards of all Americans."64

Agriculture65

NAFTA's agriculture provisions include tariff and quota elimination, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, rules of origin, and grade and quality standards.66 NAFTA set separate bilateral undertakings on cross-border trade in agriculture, one between Canada and Mexico, and the other between Mexico and the United States. As a general matter, CUSFTA provisions continued to apply on trade with Canada.67 Under CUSFTA, Canada excluded dairy, poultry, and eggs for tariff elimination. In return, the United States excluded dairy, sugar, cotton, tobacco, peanuts, and peanut butter. Although NAFTA resulted in tariff elimination for most agricultural products and redefined import quotas for some commodities as tariff-rate quotas (TRQs),68 some products are still subject to high above-quota tariffs, such as U.S. dairy and poultry exports to Canada. Canada maintains a supply-management system for these sectors that effectively limits U.S. market access. These products were also exempt from Canada-Mexico trade liberalization. NAFTA also addressed SPS measures and other types of nontariff barriers that may limit agricultural trade. SPS regulations continue to be regarded by agricultural exporters as challenging to trade and disruptive to integrated supply chains.69

In conjunction with agricultural reforms underway in Mexico at the time, NAFTA eliminated most nontariff barriers in agricultural trade with Mexico, including import licensing requirements, through their conversion either to TRQs70 or to ordinary tariffs. Tariffs were phased out over 15 years with sensitive products such as sugar and corn receiving the longest phase-out periods. Approximately one-half of U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade became duty-free when the agreement went into effect. Prior to NAFTA, most tariffs in agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico, on average, were fairly low, though some U.S. exports to Mexico faced tariffs as high as 12%. However, approximately one-fourth of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico (by value) were subjected to restrictive import licensing requirements.71

In the USMCA negotiations on agriculture, a principal U.S. demand was for additional market access to Canada's supply-management-restricted dairy, poultry, and egg markets. This system places a tariff-rate quota on imports of those products into Canada. While most of the in-quota tariff levied is 0%, out of quota tariffs (TRQ) can reach 313.5% for dairy products. Canada was not willing to abolish supply management, but did allow a yearly expansion of the TRQ for dairy products; an expansion of duty-free quota for poultry from 47,000 tons to 57,000 tons in year six, and a subsequent 1% annual increase for 10 years. The TRQ for eggs would increase to 10 million dozen annually. In return, the United States is providing more access to Canadian dairy, sugar, peanuts and cotton. U.S. tariffs for peanuts and cotton are to be phased-out over five years, and TRQs for dairy and sugar products are to be increased. The United States also negotiated changes to Canadian wheat grading system and providing national treatment for beer, wine, and spirits labeling and sales. A U.S. proposal to allow trade remedies to be used for seasonal produce was not adopted.

USMCA partners agreed to several other non-market access provision in the agriculture and sanitary and phytosanitary standards chapter. These include

- regulatory alignment among the parties;

- protection for proprietary formulas for pre-packaged foods and food additives (limited to furthering "legitimate objective[s]," which is not defined); and

- SPS rules based on "relevant scientific principles;" greater transparency in SPS rules.

Biotechnology provisions affecting agriculture include

- transparent and timely application and approval process for crops using biotechnology;

- procedures for import shipments containing a low-level presence of an unapproved crop produced with biotechnology; and

- establishment of a working group on agricultural biotechnology.

Customs and Trade Facilitation

Customs and trade facilitation relates to the efficient flow of legally traded goods in and out of the United States. Enforcement of U.S. trade laws and import security are other important components of customs operations at the border. NAFTA's chapter on customs procedures includes provisions on certificates of origin, administration and enforcement, and customs regulation and cooperation. More recent agreements have modernized provisions in regard to customs procedures and trade facilitation. The World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), the newest international trade agreement in the WTO, entered into force on February 22, 2017. Two-thirds of WTO members, including the United States, Canada, and Mexico, ratified the multilateral agreement.72 Trade facilitation measures aim to simplify and streamline customs procedures to allow the easier flow of trade across borders and thereby reduce the costs of trade. There is no precise definition of trade facilitation, even in the WTO agreements. Trade facilitation can be defined narrowly as improving administrative procedures at the border or more broadly to also encompass behind-the-border measures and regulations. The TFA aims to address trade barriers, such as lack of customs procedural transparency and overly burdensome documentation requirements.73

In the proposed USMCA, parties affirmed their rights and obligations under the TFA of the WTO. USMCA provisions also include commitments to administer customs procedures in such ways as to facilitate trade or the transit of a good while supporting compliance with domestic laws and regulations. Parties commit to create a Trade Facilitation Committee to cooperate on trade facilitation and adopt additional measures if necessary. Other provisions include measures for online publication of information and resources related to trade facilitation, communications mechanisms, establishment of enquiry points to respond to enquiries by interested persons, rules for issuing written advance customs rulings, procedures for efficient release of goods in order to facilitate trade between the parties, expedited customs procedures for express shipments, automated risk analysis and management procedures, creation of a single-access window system to enable electronic submission through a single entry point for importation into the territory of another party, and transparency procedures. Given the magnitude and frequency of U.S. trade with NAFTA partners, more updated customs provisions in NAFTA could have a significant impact on companies engaged in trilateral trade.74

The USMCA would set de minimis customs threshold for duty free treatment at US$800 for the United States, C$150 (about US$117) for Canada, and US$117 for Mexico. Tax-free threshold would be set at C$40 (about US$31) for Canada and US$50 for Mexico. Proponents of the higher de minimis thresholds contend that these changes will facilitate North American trade by allowing low-value parcels to be shipped across international borders tax and tariff free and with simple customs forms.75 Some Members and other stakeholders have raised concerns about a footnote that would allow the United States to decrease its threshold to a reciprocal de minimis amount in an amount no greater than the Canadian or Mexican threshold. They contend that lowering the current U.S. threshold could come at a cost to U.S. consumers and express carriers.76

Energy

NAFTA includes explicit country-specific exceptions and reservations, including the energy sector in Mexico. In NAFTA's energy chapter, the three parties confirmed respect for their constitutions. This was of particular importance for Mexico and its 1917 Constitution, which established Mexican national ownership of all hydrocarbons resources. Under NAFTA, the Mexican government reserved to itself strategic activities, including investment and provisions in such activities, related to the exploration and exploitation of crude oil, natural gas, and basic petrochemicals. Mexico also reserved the right to provide electricity as a public service within the country. Despite these exclusions from NAFTA, energy remains a central component of U.S.-Mexico trade.77

The proposed USMCA does not have an energy chapter and moves some of NAFTA's energy provisions to other parts of the agreement. The USMCA adds a new chapter specifically recognizing Mexico's constitutional prohibitions on foreign investment or ownership of Mexico's energy sector. Other provisions in the USMCA, such as the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions in regard to Mexico's energy sector, would help protect private U.S. energy projects in Mexico.

In 2013, the Mexican Congress approved the Peña Nieto Administration's constitutional reform proposals for the energy sector. The reforms restructured Mexico's state-owned oil company, PEMEX, as a "state productive company," which means that despite being owned by the state, it competes in the market like any private company.78 It has operational autonomy, in addition to its own assets. These reforms opened Mexico's energy sector to production-sharing contracts with private and foreign investors while keeping the ownership of Mexico's hydrocarbons under state control.79 Following the reforms, Mexico adopted new procurement rules to increase efficiency and effectiveness in the procurement process. In the NAFTA renegotiations, U.S. industry groups called for the United States to use NAFTA's so-called ratchet mechanism in regard to Mexico's energy reforms, which would prevent the reforms from being reversed and grant protection to U.S. investors.80

In regard to Canada, negotiators addressed a so-called "proportionality" provision contained in the energy chapters of both CUSFTA and NAFTA, which would be dropped under the proposed USMCA. This provision provides that Canadian restrictions on energy exports cannot reduce the proportion of exports delivered to the United States. The chapter also prohibits pricing discrimination between domestic consumption and exports to the United States. Some Canadians maintain that this provision restricts the ability of Canada to make energy policy decisions and may seek to change this provision.

Government Procurement

The NAFTA government procurement chapter sets standards and parameters for government purchases of goods and services. Government procurement chapters typically extend national and nondiscriminatory treatment among parties and promote transparency in the tendering process. The schedule of commitments, set out in an annex to the chapter, provides opportunities for firms of each nation to bid on certain contracts for specified government agencies over a set monetary threshold on a reciprocal basis. The United States and Canada also have made certain government procurement opportunities available through similar obligations in the plurilateral WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). Mexico is currently not a member of the GPA.

Supporters of expanded procurement opportunities in FTAs argue that the reciprocal nature of the government procurement provisions in FTAs allows U.S. firms access to major government procurement market opportunities overseas. In addition, supporters claim open government procurement markets at home allow government entities to accept bids from partner country suppliers, potentially making more efficient use of public funds.

Other stakeholders contend that public procurement should primarily benefit domestic industries. The Buy American Act of 1933, as amended, limits the ability of foreign companies to bid on government procurements of manufactured and construction products. Buy American provisions periodically are proposed for legislation such as infrastructure projects requiring government purchases of iron, steel, and manufactured products.81 Such restrictions are waived for products from countries with which the United States has FTAs or to countries belonging to the GPA. The Trump Administration has made it a priority to support strong Buy American and Hire American policies in government procurement and has sought to minimize government procurement commitments with other parties.

The proposed USMCA government procurement chapter only applies to procurement between Mexico and the United States. It is the first U.S. FTA not to include procurement commitments for all parties. Procurement opportunities between the United States and Canada continue to be covered by the plurilateral WTO GPA. The proposed USMCA carries over much of the NAFTA government procurement chapter's coverage for U.S.-Mexico procurement. It covers largely the same entities and maintains the same thresholds as NAFTA, as adjusted annually for inflation. Core provisions

- promote transparency in the tendering process through online tender information and descriptions;

- provide online application and documentation processes without cost to the applicant;

- provide for publication of post-award explanations of procurement decisions;

- exclude government procurement from the financial services chapter;

- exclude textile and apparel procured by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) under the "Kissell Amendment;"

- allow Mexico to set aside annual procurement contracts of $2.328 billion, annually adjusted for inflation, to Mexican suppliers;

- allow for coverage of build-operate-transfer (BOT) contracts (As Mexico has taken an exception to this provision, the United States will extend this coverage to Mexico when Mexico reciprocates.)

The exclusion of Canada is a break from previous government procurement chapters in U.S. FTAs. As noted above, procurement opportunities in each country for U.S. and Canadian firms will continue to be covered by the GPA, which was revised and updated in 2014. The national treatment and transparency provisions are common to both the GPA and the proposed USMCA, as are the provisions modernizing the agreement to provide for online tendering. The differences primarily are with the schedules and the thresholds. In some areas, the GPA provides a more open procurement market. For example, the GPA covers 75 U.S. government entities, including 35 U.S. states, whereas NAFTA covers 56 federal entities and does not cover state procurement. The GPA has a higher monetary threshold than NAFTA for procurement of goods and services ($180,000 v. $80,317), but a lower construction procurement threshold ($6.9 million v. $10.4 million).82 In addition, while the proposed USMCA uses a negative list approach for services (all services included unless specifically excluded), Canada—though not the United States—maintains a positive list (only services specifically enumerated are covered) for services in the GPA. Government procurement between Canada and Mexico will continue to be covered by the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11).

Some industry groups have criticized the exclusion of Canada and financial services from the agreement. The Automotive and Capital Goods Advisory Committee (ITAC-2) maintained that excluding countries sets a bad precedent for future FTAs, that there was a "not inconceivable" chance that the United States could withdraw from the GPA, leaving no reciprocal access to the Canadian procurement market, and that other countries with FTAs with Canada, such as the EU and the TPP-11, would have greater access to the Canadian procurement market than that provided by the GPA.83 The Services ITAC (ITAC-10) expressed concern that continued access to government procurement for financial services under USMCA has been called into doubt by the exclusion of that sector from the agreement. ITAC-10 noted that, under NAFTA coverage, U.S. insurance providers cover two-thirds of Mexican government employees.84

Investment

NAFTA removed significant investment barriers, ensured basic protections for NAFTA investors, and provided a mechanism for the settlement of disputes between investors and a NAFTA country. U.S. FTAs, including NAFTA and bilateral investment treaties (BITs) maintain core investor protections reflecting U.S. law, such as obligations for governments to provide investors with nondiscriminatory treatment, a minimum standard of treatment, and protections against uncompensated expropriation, among other provisions.85 Since NAFTA, investment chapters in FTAs and the U.S. model BIT clarified certain provisions, including commitments to affirm more clearly a government's right to regulate for environmental, health, and other public policy objectives.

The proposed USMCA provisions, in general, largely track those of NAFTA, with the exception of the elimination of some investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions in NAFTA's investment chapter (See "Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS)"). During the negotiations of the proposed USMCA, the U.S. business community strongly opposed reported U.S. proposals to scale back or eliminate NAFTA ISDS provisions. The American Petroleum Institute (API), for example, stated that strong ISDS provisions protect U.S. business interests and that weakening or eliminating NAFTA's ISDS would "undermine U.S. energy security, investment protections and our global energy leadership."86 On the other hand, U.S. labor and civil society groups welcomed the Administration's more skeptical approach to ISDS. The 2015 TPA called for "providing meaningful procedures for resolving investment disputes," which may affect congressional consideration of an agreement.87

The proposed USMCA clarifies language related to national treatment and most-favored-nation treatment. In determining whether an investment is afforded national treatment in the context of expropriation, a "like circumstances" analysis can be used. Under the article, "like circumstances" depends on the totality of the circumstances including whether the relevant treatment distinguishes between investors or investments on the basis of legitimate public welfare objectives."88

Minimum Standard of Treatment (MST)

The proposed USMCA, like NAFTA, requires parties to provide MST to investments in accordance with applicable customary international law, including fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security. It defines the applicable standard of treatment for a covered investment as the customary international law MST of aliens, and that "fair and equitable treatment" and "full protection and security" do not create additional substantive rights. However, the proposed USMCA clarifies that a party's action (or inaction) that may be inconsistent with investor expectations is not, on its own, a breach of MST, even if loss or damage to the investment follows.

Performance Requirements

The proposed USMCA would prohibit parties from imposing specific "performance requirements" in connection with an investment or related to the receipt of an advantage in connection with it. These include prohibitions on performance requirements such as to export a given level or percentage of goods, achieve a given level or percentage of domestic content, or transfer a particular technology. A new feature not in NAFTA includes prohibitions on performance requirements related to the purchase, use, or according of a preference to a technology of the party (or of a person of the party), and related to certain royalties and license contracts.

Denial of Benefits

The proposed USMCA's denial of benefits article, among other things, permits a party to deny the investment chapter's benefits to an investor that is an enterprise of another party (and to the investments of that investor) if that enterprise is owned or controlled by a person of a non-party or of the denying party or does not have "substantial business activities" in the territory of any party other than the party denying benefits. This article presumably is intended to address some stakeholder concerns that the chapter could be used to afford shell companies access to its protections.

Government Right to Regulate

Unlike NAFTA, the proposed USMCA contains a provision stating that, except in rare circumstances, nondiscriminatory regulatory action by a party to protect legitimate public welfare objectives (e.g., in public health, safety, and the environment) do not constitute indirect expropriation. Debate exists about what exactly are "rare circumstances." The proposed USMCA includes a statement that nothing in the Investment Chapter shall be construed to prevent a government from regulating in a manner sensitive to "health, environmental, and other regulatory objectives," as long as the action taken is otherwise consistent with the chapter. Previous U.S. FTAs, including NAFTA, limited the affirmation of a government's right to regulate to "environmental concerns."

Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS)

ISDS has been a controversial aspect of the NAFTA investment chapter. It is a form of binding arbitration that allows private investors to pursue claims against sovereign nations for alleged violations of the investment provisions in trade agreements. It is included in NAFTA and nearly all other U.S. trade agreements that have been enacted since then, and is also a core provision in U.S. bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Generally, ISDS tribunals are composed of three lawyer-arbitrators: one chosen by the claimant investor, one by the respondent country, and one by mutual decision between the two parties. Most cases follow the rules of the World Bank's Centre for Settlement for Investor Dispute or the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law. Fifty-nine ISDS actions have been adjudicated under NAFTA, with the majority coming after 2004.89

Supporters argue that ISDS is important for protecting investors from discriminatory treatment and are modeled after U.S. law. They also argue that trade agreements do not prevent governments from regulating in the public interest, with clear exceptions for these actions, as well as for national security and for prudential reasons; ISDS remedies are limited to monetary penalties; and ISDS cannot force governments to change their laws or regulations. Critics counter that companies use ISDS to restrict governments' ability to regulate in the public interest (such as for environmental or health reasons), leading to "regulatory chilling" even if an ISDS outcome is not in a company's favor. The United States, to date, has never lost a claim brought against it under ISDS in a U.S. investment agreement.

|

NAFTA Record on ISDS As of February 2019

|

ISDS provisions in the proposed USMCA would substantially revise longstanding provisions in NAFTA, other U.S. FTAs, and current BITs that were actively sought by past Administrations. Significantly, ISDS between Canada and the United States is ended under the new agreement. U.S. and Mexican investors would not be able to bring arbitration claims under USMCA against Canada, nor would Canadian investors bring such claims against the United States or Mexico. With respect to Mexico and the United States, the proposed USMCA would limit ISDS to claimants regarding government contracts in natural gas, power generation, infrastructure, transportation, and telecommunications sectors; or in other sectors provided the claimant exhausts national remedies first. Canada and Mexico are maintaining ISDS among themselves through CPTPP.

Under the proposed USMCA, ISDS is continued in three circumstances:

- Legacy claims from existing investments are eligible for arbitration under NAFTA ISDS provisions for three years from the date of NAFTA termination;

- Direct expropriation claims, including claims of violation of national treatment, would continue to be eligible for arbitration for United States and Mexican investors, provided that they exhaust domestic remedies first. Indirect expropriation, in which an action or series of actions by a Party has an effect equivalent to direct expropriation without formal transfer of title or outright seizure, is no longer covered; and

- Government contracts in certain covered sectors (oil and gas, power generation, telecommunications, transportation, and infrastructure) would be eligible for arbitration under USMCA ISDS. This use of ISDS is designed to protect investors in heavily regulated industries whose investments may be affected by the presence of state-owned enterprises in the sector.

Services

The United States has a highly competitive services sector and has made services trade liberalization a priority in its negotiations of FTAs, including NAFTA and the proposed USMCA.90 NAFTA covers core obligations in services trade in its own chapter, but because of the complexity of the issues, it also covers services trade in other related chapters, including financial services and telecommunications. NAFTA contained the first "negative list" services chapter in a U.S. trade agreement, and it is maintained in the proposed USMCA. With a negative list, all services are covered under the agreement unless specifically excluded from it, or unless NAFTA parties reserved a service to domestic providers at the time of the agreement. This approach generally is considered to be more comprehensive than the "positive list approach" used in the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which requires each covered service to be identified. The negative list approach also implies that any new type of service that is developed after the agreement enters into force is automatically covered unless it is specifically excluded. Key provisions of the services chapter in NAFTA and the proposed USMCA include the following:

- nondiscriminatory treatment of services from partner-country providers in like circumstances, including national treatment and MFN treatment;

- no limitations on the number of service suppliers, the total value or volume of services provided, the number of persons employed, or the types of legal entities or joint ventures that a foreign service supplier may employ;

- prohibition on locality requirements that a service provider maintain a commercial presence in the country of the buyer;

- support of mutual recognition of professional qualifications for certification of service providers;

- transparency in the development and application of government regulations; and

- allowance for payments and transfers of capital flows "freely and without delay" that relate to the provision of services, with permissible restrictions in some cases for bankruptcy and criminal offences.

Express Delivery

NAFTA did not contain commitments on express delivery; however, the United States made market access of express delivery services a priority in its more recent FTA negotiations. The proposed USMCA addresses express delivery in a chapter annex.91 The commitments on express delivery focus, in particular, on cases where a government-owned and operated postal system provides express delivery services competing with private sector providers. The proposed USMCA stipulates that the postal system cannot use revenue generated from its monopoly power in providing postal services to cross-subsidize an express delivery service. The proposed USMCA would also require independence between express delivery regulators and providers, prohibit the requirement of providing universal postal service as a prerequisite for express delivery, and prohibit fees on express delivery providers for the purpose of funding other such providers. In addition, the proposed USMCA specified a threshold level for the customs de minimis, a critical commitment for express delivery providers and small businesses as shipments valued below the de minimis receive expedited customs treatment and pay no duties or taxes.

|

De Minimis Threshold The de minimis threshold for assessing customs duties on imported goods was a new issue in the USMCA negotiations, one which affects several negotiating areas such as customs, services, and e-commerce. The controversy surrounds the threshold customs valuation assessed among the three NAFTA nations for goods entering the country (mailed, delivered by courier, transported by distributors, etc.) without charging duty or sales tax. The United States has sought increased thresholds from its trading partners. While the United States currently exempts duties for shipments under $800 (P.L. 114-125, §901), Canada's threshold is C$20 (recently about US$15-16) and Mexico's is $50. The proposed USMCA raised the customs threshold for duty free treatment to $117 (C$150) for Canada and Mexico. The tax-free threshold was set at $50 for Mexico and C$40 (about $31) for Canada. However, a footnote also allows the U.S. threshold to be lowered to achieve reciprocity, a controversial provision to some Members of Congress. |

Temporary Entry for Business Purposes

In addition to cross-border trade in services, a person supplying the service may travel to and provide certain services in the location where the service is performed. NAFTA includes commitments on temporary entry for service professionals, such as accountants, architects, legal, and medical providers, and other business personnel, in order to facilitate such trade. As temporary entry has been a controversial issue in the context of previous trade agreements, the proposed USMCA chapter on temporary entry largely replicates NAFTA's provisions. The proposed USMCA does not place new restrictions on the number of entrants or expand the list of eligible professionals, as many businesses and other service providers had hoped.

Financial Services

Financial services, including insurance and insurance-related services, banking and related services, as well as auxiliary services of a financial nature, are addressed in a separate USMCA chapter as in previous U.S. FTAs. The financial services chapter adapts relevant provisions from the foreign investment chapter and the cross-border trade in services chapter. The prudential exception in NAFTA and the proposed USMCA provides that nothing in the FTA would prevent a party to the agreement from imposing measures to ensure the integrity and stability of the financial system. As with NAFTA and other FTAs, the proposed USMCA distinguishes between financial services traded across borders and those sold by a provider with a commercial presence in the home country of the buyer. In the case of providers with a foreign commercial presence, the USMCA applies the negative list approach with commitments applying generally except where noted; in the case of cross-border trade, the proposed language limits coverage to a positive list of specific banking and insurance services as defined by each country.92

Perhaps the provision in the proposed USMCA that has drawn the most attention is the prohibition on data localization requirements. Financial services firms rely on cross-border data flows to ensure data security, create efficiencies and cost savings through economies of scale, and utilize internet cloud services that are often provided by U.S. technology firms. Localization requirements imposed by countries could require companies to have in-country servers and data centers to store data. These types of regulations can create additional costs and may serve as a deterrent for firms seeking to enter new markets or a disguised barrier to trade. Localization supporters, though, claim they increase local control, privacy protection, and data security.

While NAFTA allowed the transfer of data in and out of a party in the ordinary course of business, TPP was the first proposed U.S. FTA to prohibit data localization for e-commerce applications. However, it specifically carved out financial services, based on the apprehension of regulatory authorities that such data may not be available during time of crisis. The proposed USMCA strengthened the language to protect the free flow of data and removes the carve-out provided that a Party's financial regulatory authorities have "for regulatory and supervisory purposes, immediate, direct, complete, and ongoing access" to data located in another party's territory.93 Canada has a one-year transition period to implement the data localization prohibition.

The proposed USMCA also includes commitments on electronic payment card services. It requires that each country in the agreement allow for the supply, by persons of other parties, of electronic payment services for payment card transactions, defined by each country, generally including credit and debit cards. The provisions on card services would, however, allow for certain preconditions of access, including requiring a representative or office within country.

Other new USMCA financial services provisions would

- exclude government procurement from financial services disciplines;

- modify investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) through a bilateral annex on Mexico-United States Investment Disputes in Financial Services;

- allow a financial institution from one party with a presence in a second party to have access to the latter's payment and clearance system; and

- protect source code and algorithms and a prohibition on forced technology transfer in the digital trade section.

Telecommunications

The telecommunication chapter in NAFTA requires regulatory transparency; interconnection among providers; reasonable and nondiscriminatory access to network infrastructure and government-controlled resources like spectrum bandwidth for reasonable rates; and protection of the supplier's options for employing technology. The proposed USMCA telecommunications chapter adopts these provisions and would be the first U.S. FTA to cover mobile service providers. The chapter would promote cooperation on charges for international roaming services and allow regulation for mobile roaming service rates. Other provisions aim to ensure that suppliers can resell and unbundle services, and that suppliers can furnish value-added services. The telecommunications chapter does not cover television or radio broadcast or cable suppliers. It also promotes the independence of regulators. It does not contain the provision in NAFTA recognizing the importance of international standards for global compatibility and interoperability.

The chapter has the effect of binding Mexico to its 2013 Constitutional reforms in telecommunications, by guaranteeing the independence of the regulatory commission, nondiscriminatory repurchase rates, and interconnection obligations. The proposed USMCA chapter does not affect Canadian restrictions on foreign ownership of telecommunications common carriers.

Digital Trade

NAFTA was negotiated and came into effect at the dawn of the consumer Internet age, and it did not contain provisions to address barriers and rules and disciplines on digital trade. Congress established principal negotiating objectives in TPA-2015 on digital trade in goods and services, as well as on cross-border data flows. The objectives include equal treatment of electronically delivered goods and services, as compared to physical products, protection of cross-border data flows, and prevention of data localization regulations, as well as prohibitions on duties on electronic transmissions.

The proposed USMCA digital trade chapter broadly covers all industries, but explicitly excludes government procurement or provisions on data held or processed by governments of the parties. It also does not include financial services, which has separate obligations in the financial services chapter. Overall, the chapter aims to promote digital trade and the free flow of information, and to ensure an open Internet. While the majority of the obligations related to digital trade are found in the digital trade chapter, there are relevant provisions in other chapters, including financial services, IPR, and telecommunications.

Key provisions of the proposed USMCA digital trade chapter

- ensure nondiscriminatory treatment of digital products;

- prohibit cross-border data flows restrictions and data localization requirements;

- prohibit requirements for source code or algorithm disclosure or transfer as a condition for market access, with exceptions;

- prohibit customs duties or other charges for electronically transmitted products;

- require parties to have online consumer protection and anti-spam laws, and a legal framework on privacy;

- promote cooperation on cybersecurity, and risk-based strategies and consensus-based standards over prescriptive regulation in combating cybersecurity risks and events;

- prohibit imposition of liability for harms against Internet services providers or users related to information stored, processed, transmitted, distributed, or made available by the service, with the exclusion of ISP liability for intellectual property rights (IPR) infringement; and

- promote publication of open government data in machine readable format for public usage.

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

NAFTA was the first FTA to contain an IPR chapter, which in turn was the model for the WTO Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) Agreement that came into effect a year later in 1995.94 IPR chapters in trade agreements include provisions on patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, geographical indications (GIs), and enforcement. NAFTA predated the widespread use of the commercial Internet, and subsequent IPR chapters in U.S. FTAs contain obligations more extensive than those found in TRIPS and NAFTA. In general, they have followed the TPA negotiating objective that agreements should "reflect a standard of protection similar to that found in U.S. law." The President's NAFTA renegotiation objectives reflect TPA-2015 and the aims of U.S. negotiators in the TPP (although in some instances the negotiated TPP outcomes were less extensive). The United States achieved most of what it sought in the proposed USMCA and some results that went beyond TPP:

Patents

Patents protect new innovations, such as pharmaceutical products, chemical processes, business technologies, and computer software. These provisions largely track provisions in more recent U.S. FTAs, including TPP:

- Patent and Regulatory term extension. Provides an extension for "unreasonable" delays in the patent examination or regulatory approval processes. NAFTA allowed countries to provide such an extension but did not define unreasonable. The proposed USMCA defines unreasonable as five years after the filing of the application, or three years after a request for examination has been made.