Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Changes from December 27, 2019 to October 16, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions

- Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market

- House Prices

- Interest Rates

- Homeownership Affordability

- Home Sales

- Housing Inventory and Housing Starts

- Mortgage Market Composition

- Rental Housing Markets

- Share of Renters

- Rental Vacancy Rates

- Rental Housing Affordability

- Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

- Status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

- Potential for Legislative Housing Finance Reform

- New FHFA Director and Possible Administrative Changes to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

- Other Issues Related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

- Housing Assistance

- Appropriations for Housing Programs

- Housing Vouchers for Foster Youth

- Implementation of Housing Assistance Legislation

- Quality of Federally Assisted Housing

- Selected Administrative Actions Related to Affordable Housing

- HUD Noncitizen Eligibility and Documentation Proposed Rule

- Equal Access to Housing

- Regulatory Barriers Council

- Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing

- Housing and Disaster Response and Recovery

- Implementation of Housing-Related Provisions of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act (DRRA)

- FEMA Short-term, Emergency Housing Program Change

- Community Development Block Grants-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR)

- Native American Housing Programs

- Tribal HUD-VASH

- NAHASDA Reauthorization

- Department of Veterans Affairs Loan Guaranty and Maximum Loan Amounts

- Housing-Related Tax Extenders

- Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt

- Deductibility of Mortgage Insurance Premiums

Summary

The 116th Congress has been considering a variety of housing-related issues. TheseHousing Issues in the 116th Congress

October 16, 2020

Since the outbreak of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in early 2020 and the resulting economic recession, pandemic relief and response has dominated the housing policy

Katie Jones, Coordinator

considerations of the second session of the 116th Congress. The CARES Act (P.L. 116-136),

Analyst in Housing Policy

enacted in March 2020, contained several housing-related provisions. These included nearly $15

billion in supplemental funding for housing-related COVID-19 relief and response as well as policies such as a temporary eviction moratorium for some properties and forbearance for some

Darryl E. Getter

mortgages. Since then, the Administration issued an order implementing a nationwide eviction

Specialist in Financial Economics

moratorium, and additional relief legislation has been introduced and considered in Congress.

Pandemic relief and response are not the only housing issues that have been considered by the

Mark P. Keightley

116th Congress. Others include topics related to housing finance, federal housing assistance

Specialist in Economics

include topics related to housing finance, federal housing assistance programs, and housing-related tax provisions, among other things. Particular issues that have

been of interest during theto Congress include the following:

-

Maggie McCarty Specialist in Housing Policy

The status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored enterprises

(GSEs) that have been in conservatorship since 2008, including administrative actions

Libby Perl

taken by their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA).

Specialist in Housing Policy

(GSEs) that have been in conservatorship since 2008. Congress could consider comprehensive housing finance reform legislation to resolve the status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. A new director for the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's regulator and conservator, was sworn in on April 15, 2019. Congress may take an interest in any administrative changes that FHFA makes to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac under new leadership. - Appropriations for federal housing programs, including programs at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and rural housing programs administered by Elizabeth M. Webster the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

-

Analyst in Emergency

Oversight of the implementation of certain changes to federal assisted housing programs

'’s Moving to Work Recovery (MTW) program and Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program, and proposed Administration actions, including a proposed rule to modify noncitizen eligibility forassisted housing programs. Considerations related to housing and the federal response to major disasters, including oversight of the implementation of certain changes related to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)Lida R. Weinstock assisted housing programs. Analyst in Macroeconomic Considerations related to housing and the federal response to major disasters, including Policy emergency sheltering options that may be implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, ongoing issues related to oversight of the Federal Emergency Managemen t Agency’s (FEMA’s) implementation of certain changes to assistance that were enactedassistance that were enactedin the previous Congress, and a bill to formally authorize the Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery program.-

Consideration of legislation related to certain federal housing programs, including bills related to programs

that provide assistance to Native Americans living in tribal areas , to serve youth aging out of foster care, and to

betterfurther regulate the quality of federally assisted housing. -

Consideration of legislation to extend certain temporary tax provisions that

are currentlyhad expired, including housing- related provisions that provide a tax exclusion for canceled mortgage debt and allow for the deductibility of mortgage insurance premiums, respectively.

Housing and mortgage market conditions provide context for these and other issues that Congress may consider, although housing markets are local in nature and national housing market indicators do not necessarily accurately reflect conditions in specific communities. On a national basis, some key characteristics of owner-occupied housing markets and the mortgage market in recent years include increasing housing prices, low mortgage interest rates, and home sales that have been increasing but constrained by a limited inventory of homes on the market. Key characteristics of rental housing markets include an increasing number of renters, low rental vacancy rates, and increasing rents. Rising home prices and rents that have outpaced income growth in recent years have led to policymakers and others increasingly raising concerns about the affordability of both owner-occupied and rental housing. Affordability challenges are most prominent among the lowest-income renter households, reflecting a shortage of rental housing units that are both affordable and available to this population. The housing-related implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and its resulting recession on U.S. markets and households are still unfolding.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 30 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 37 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 45 link to page 46 link to page 46 link to page 48 link to page 50 link to page 51 link to page 51 link to page 52 Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions .......................................................................... 1

Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market ........................................... 2

House Prices........................................................................................................ 2 Interest Rates ....................................................................................................... 3 Homeownership Affordability ................................................................................ 4 Home Sales ......................................................................................................... 5

Housing Inventory and Housing Starts..................................................................... 6 Mortgage Market Composition ............................................................................... 8

Rental Housing Markets ............................................................................................. 9

Share of Renters................................................................................................... 9 Rental Vacancy Rates.......................................................................................... 10

Rental Housing Affordability ............................................................................... 11

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Housing ............................................................................ 12

COVID-19 and Effects on Housing ............................................................................ 12

Federal Housing Responses to COVID-19 ................................................................... 14

Federal Interventions Related to Rental Housing ..................................................... 14 Federal Interventions Related to Mortgages ............................................................ 16 Increased Funding for Housing Programs............................................................... 19

Proposals for Additional Action ................................................................................. 20

Other Housing Issues in the 116th Congress ....................................................................... 21

Housing Finance ..................................................................................................... 21

Status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac .................................................................. 21 CFPB’s Proposed Changes to the Qualified Mortgage Rule and the GSE Patch............ 26

Department of Veterans Affairs Loan Guaranty and Maximum Loan Amounts ............. 28

Housing Assistance .................................................................................................. 28

Appropriations for Housing Programs ................................................................... 28 Housing Vouchers for Foster Youth ....................................................................... 30 Implementation of Housing Assistance Legislation .................................................. 31

Quality of Federal y Assisted Housing ................................................................... 33 Native American Housing Programs...................................................................... 34 Proposed New Investments in Affordable Housing .................................................. 35

Selected Administrative Actions Related to Affordable Housing ..................................... 37

HUD Noncitizen Eligibility and Documentation Proposed Rule................................. 37

Equal Access to Housing ..................................................................................... 38 Regulatory Barriers Council................................................................................. 39 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing................................................................... 39

Housing and Disaster Response and Recovery ............................................................. 40

Emergency Sheltering Options During the COVID-19 Pandemic ............................... 41 Implementation of Housing-Related Provisions of the Disaster Recovery Reform

Act (DRRA) ................................................................................................... 42

FEMA Short-term, Emergency Housing Program Change......................................... 44 Community Development Block Grants-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR).................... 46

Housing-Related Tax Extenders ................................................................................. 47

Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt.................................................................. 47

Deductibility of Mortgage Insurance Premiums....................................................... 48

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 17 link to page 53 Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Figures Figure 1. Year-over-Year House Price Changes (Nominal) ..................................................... 2 Figure 2. Mortgage Interest Rates ...................................................................................... 3 Figure 3. New and Existing Home Sales ............................................................................. 5 Figure 4. Housing Starts ................................................................................................... 7 Figure 5. Share of Mortgage Originations by Type ............................................................... 8 Figure 6. Rental and Homeownership Rates ........................................................................ 9 Figure 7. Rental Vacancy Rates ....................................................................................... 10 Figure 8. Renters and Owners Having Difficulty Making Housing Payments.......................... 13

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 49

Congressional Research Service

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Introduction In March 2020, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic began having wide-ranging public health and economic effects in the United States. The impacts of the pandemic have

implications for housing, including the ability of households experiencing income disruptions to make housing payments. In response, Congress and the Administration have taken a variety of actions related to COVID-19 and housing. However, the pandemic is continuing and the economy is in a recession. Some initial assistance measures have ended, and there have been cal s for additional action. The longer-term consequences of the pandemic and associated economic

turmoil on housing markets remain unclear.

Outside of pandemic-related housing issues, several other housing-related issues have been active during the 116th Congress. These include issues related topopulation.

Introduction

The 116th Congress has been considering a variety of housing-related issues. These involve assisted housing programs, such as

those administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and issues related to housing finance, among other things. Specific topics of interest include ongoing issues such as interest in reforming the nation's housing finance system,issues such as the status of two government-sponsored enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; how to prioritize appropriations for federal housing programs in a limited funding environment, ; oversight of the implementation of changes to certain housing programs that were enacted in prior Congresses, and the possibility of extending Congresses; administrative changes to certain affordable housing policies and programs; and the

extension of certain temporary housing-related tax provisions. Additional issues may emerge as the Congress progresses.

This report provides a high-level overview of the most prominent housing-related issues that have

been of interest during the 116th Congress. It116th Congress. It begins with an overview of housing and mortgage market conditions during the Congress to date. While this overview includes some national-level statistics from the months after the pandemic began, it is stil too early to know how the pandemic wil ultimately affect housing markets in the medium or longer term. The following section discusses housing-related concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic and federal housing responses. Final y, the report discusses other housing issues that have been active during the 116th

Congress.

The discussion in this report provides a broad overview of major issues and is not intended to

provides a broad overview of major issues and is not intended to provide detailed information or analysis. It includes references to more in-depth CRS reports on

these issues where possible.

Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions

This section provides background on housing and mortgage market conditions at the beginning of the 116th during the 116th Congress to provide context for the housing policy issues discussed in the remainder of the report. This discussion of market conditions is at the national level. Yet, localLocal housing market conditions can vary dramatically

vary dramatical y, and national housing market trends may not reflect the conditions in a specific area. Nevertheless, national housing market indicators can provide an overall overal sense of general

trends in housing.

In general, rising home prices, relatively low interest rates, and rising rental costs have been prominent features of housing and mortgage markets in recent years. Although interest rates have remained low, rising house prices and rental costs that in many cases have outpaced income growth have led to increased concerns about housing affordability for both prospective homebuyers and

renters.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the United States beginning in March 2020, some housing indicators showed notable changes. For example, interest rates fel , and home sales and

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 6

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

construction activity experienced significant declines, although sales and construction indicators rebounded to varying degrees in subsequent months. Other housing market indicators, such as house prices, have shown only relatively slight changes to date. Since these indicators reflect national-level conditions, conditions in specific local housing markets may differ. Going forward, the pandemic’s impacts on housing market conditions are highly uncertain and wil depend on a

variety of factors.

Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market

Most homebuyers take out a mortgage to purchase a home. Therefore, owner-occupied housing markets and the mortgage market are closely linked, although they are not the same. The ability of prospective homebuyers to obtain mortgages, and the costs of those mortgages, impact housing demand and affordability. The following subsections show current trends in selected owner-

occupied housing and mortgage market indicators.

House Prices

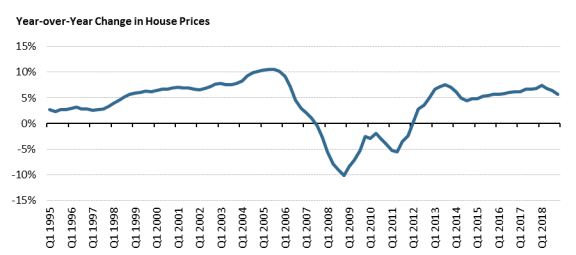

As shown inin Figure 1, nationally, nominal house prices have been increasingincreased national y on a year-over-year basis in each quarter since the beginning of 2012, with year-over-year increases exceeding 5% for much of that time period and exceeding 6% for most quarters since mid-2016at times. These increases followfollowed almost five years of house price declines in the years during and surrounding the economic recession of 2007-2009

and associated housing market turmoil. House

Year-over-year house price increases have slowed somewhat but continued to exceed 5% through

the second quarter of 2020, despite the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.1

slowed somewhat during 2018, but year-over-year house prices still increased by nearly 6% during the fourth quarter of 2018.

1 See Federal Housing Finance Agency, House Price Index (HPI) Quarterly Report, 2020Q2 and June 2020, August 25, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/AboutUs/Reports/ReportDocuments/2020Q2_HPI.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 7

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

House prices, and changes in house prices, vary greatly across local housing markets. Some areas of the country are experiencingcan experience rapid increases in house prices, while other areas are experiencingexperience slower or stagnating house price growth. Similarly, prices have fully regained or even exceeded their pre-recession levels in nominal terms in many parts of the country, but in other areas prices remain below those levels.1

HouseFurthermore, house price increases affect participants in the housing market differently. Rising prices reduce affordability for prospective homebuyers, but they are generallygeneral y beneficial for current homeowners due to the increased home equity that accompanies them (although rising house prices also have the potential to negatively impact

affordability for current homeowners through increased property taxes).

Interest Rates

For several years, mortgage interest rates have been low by historical standards. Lower interest rates increase mortgage affordability and make it easier for some households to purchase homes or refinance their existing mortgages.

As shown inin Figure 2, average mortgage interest rates have been consistently below 5% since May 2010 and have been below 4% for several stretches during that time. After starting to

increase somewhat in late 2017 and much of 2018, mortgage interest rates showed declines at the end of 2018 into early 2019. The average mortgage interest rate for February 2019 was 4.37%, compared to 4.46% in the previous month and 4.33% a year earlier.

have been general y

declining since late 2018.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, interest rates have fal en even further, in part due to

federal monetary policy responses to the pandemic. At times, interest rates have been below 3%, their lowest levels since at least 1971.2 The average mortgage interest rate for August 2020 was

2.94%, compared to 3.02% in the previous month and 3.62% a year earlier.

Figure 2. Mortgage Interest Rates

January 1995–August 2020

January 1995–February 2019 |

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from Freddie pmms/. Notes: Freddie |

2 For example, see Freddie Mac, “Mortgage Rates Drop, Hitting a Record Low for th e Eighth T ime this Year,” press release, August 6, 2020, https://freddiemac.gcs-web.com/node/20476/pdf.

Congressional Research Service

3

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Homeownership Affordability

Homeownership Affordability

House prices have been rising for several years on a national basis, and mortgage interest rates, while low currentlywhile still low by historical standards, have also risen for certain stretches. While incomes have also been rising in recent years, helping to mitigate some affordability pressures, on the whole house price increases have outpaced income increases.23 Home price-to-income ratios have been generally trending upwards since around 2012, with the national median sales price for an existing home more than 4.1 times the median household income in 2018.4 These trends have led to increased concerns

about the affordability of owner-occupied housing.

Despite rising house prices, many metrics of housing affordability suggest that owner-occupied housing is currently relatively affordable.35 These metrics generallygeneral y measure the share of income that a median-income family would need to qualify for a mortgage to purchase a median-priced home, subject to certain assumptions. Therefore, rising incomes and, especiallyespecial y, interest rates that are stil are still low by historical standards contribute to monthly mortgage payments being considered

affordable under these measures despite recent house price increases.

Some factors that affect housing affordability may not be captured by these metrics. For example, several of the metrics are based on certain assumptions (such as a borrower making a 20% down

payment) that may not apply to many households. Furthermore, because they typicallytypical y measure the affordability of monthly mortgage payments, they often do not take into account other affordability challengeschal enges that homebuyers may face, such as affording a down payment and other upfront costs of purchasing a home (costs that generallygeneral y increase as home prices rise). Other factors—such as the ability to qualify for a mortgage, the availability of homes on the market, and

regional differences in house prices and income—may also make homeownership less attainable for some households.4 6 Some of these factors may have a bigger impact on affordability for specific demographic groups, as income trends and housing preferences are not uniform across all al

segments of the population.7

It is unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic may ultimately impact the affordability of homeownership. The pandemic could have implications for a variety of interrelated factors that affect affordability, including factors related to both the supply of homes on the market and the

demand for homes.

3 See Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, State of the Nation’s Housing 2018, p. 22, http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2018.pdf , showing changes in median house prices and median household incomes (in real terms). 4 Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, State of the Nation’s Housing 2019, p.12, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/state-nations-housing-2019.

5 For example, see U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Housing Market Indicators Monthly Update, August 2020, p.3, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Housing-Market -Indicators-Report -August-2020.pdf, showing the National Association of Realtors Housing Affordability Index (HAI) compared to its historical norm. (For more information on the HAI, see the National Association of Realtors website at https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/housing-statistics/housing-affordability-index/methodology.) See also

the Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center’s Housing Finance at a Glance: A Monthly Chartbook, August 2020, p. 21,

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102776/august-chartbook-2020.pdf.

6 Freddie Mac Insight, If Housing Is So Affordable, Why Doesn't It Feel That Way?, July 19, 2017, http://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20170719_affordability.html. 7 For example, see the discussion of affordability challenges for younger households in Freddie Mac Insight , Locked Out? Are Rising Housing Costs Barring Young Adults from Buying Their First Hom es?, June 2018, http://www.freddiemac.com/research/pdf/201806-Insight -05.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9 link to page 9

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Home Sales

Annual home sales increased between 2014 and 2017, improvingsegments of the population.5

Given that house price increases are showing some signs of slowing and interest rates have remained low, the affordability of owner-occupied homes may hold steady or improve. Such trends could potentially impact housing market activity, including home sales.

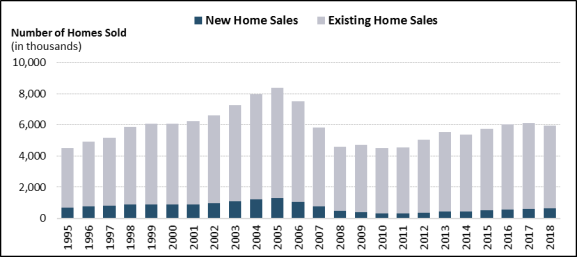

Home Sales

In general, annual home sales have been increasing since 2014 and have improved from their levels during the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, although in 2018 the overall . The overal number of home sales declined from the previous year in 2018 and remained steady in 2019. While home sales have been improving somewhat in recent years (prior to fallingfal ing in 2018), the supply of homes on the market has generally

general y not been keeping pace with the demand for homes, thereby limiting home sales activity

and contributing to house price increases.

Home sales include sales of both existing and newly built homes. Existing home sales generally general y

number in the millionsmil ions each year, while new home sales are usuallyusual y in the hundreds of thousands. thousands. Figure 3 shows the annual number of existing and new home sales for each year from 1995 through 20182019. Existing home sales numbered about 5.3 million in 2018, mil ion in 2019, steady from the previous year and a decline from 5.5 millionmil ion in 2017 (existing home sales in 2017 were the highest level since 2006). New home sales numbered about 622683,000 in 20182019, an increase from 614

617,000 in 20172018 and the highest level since 2007. However, the number of new home sales remains appreciably lower than in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when they tended to be

between 800,000 and 1 millionmil ion per year.

per year.

Figure 3. New and Existing Home Sales

Annual, 1995–2019

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from HUD |

While Figure 3 shows annual home sales through 2019, monthly home sales have been impacted

since the pandemic began. Both new and existing home sales fel sharply in March and April

2020, though both rebounded during the summer months.8

8 HUD, Housing Market Indicators Monthly Update, August 2020 , pages 1-2, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Housing-Market -Indicators-Report -August-2020.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 11 Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Housing Inventory and Housing Starts

Housing Inventory and Housing Starts

The number and types of homes on the market affect home sales and home prices. On a national basis, the supply of homes on the market has been relatively low in recent years,69 and in general new construction has not been creating enough new homes to meet demand.710 However, as noted previously, national housing market indicators are not necessarily indicative of local conditions.

While many areas of the country are experiencing low levels of housing inventory that contribute to higher home prices, other areas, particularly those experiencing population declines, face a different set of housing challengeschal enges, including surplus housing inventory and higher levels of

vacant homes.8

11

On a national basis, the inventory of homes on the market has been below historical averages in recent years, though the inventory, of new homes, in particular, has begun to increase somewhat of late.912 Homes come onto the market through the construction of new homes and when current homeowners decide to sell sel their existing homes. Existing homeowners'’ decisions to sell their sel their

homes can be influenced by expectations about housing inventory and affordability. For example, current homeowners may choose not to sell sel if they are uncertain about finding new homes that meet their needs, or if their interest rates on new mortgages would be substantiallysubstantial y higher than the interest rates on their current mortgages. New construction activity is influenced by a variety of

factors including labor, materials, and other costs as well wel as the expected demand for new homes.

One measure of the amount of new construction is housing starts. Housing starts are the number of new housing units on which construction is started in a given period and are typicallytypical y reported monthly as a "seasonally“seasonal y adjusted annual rate."” This means that the number of housing starts

reported for a given month (1) has been adjusted to account for seasonal factors and (2) has been multiplied multiplied by 12 to reflect what the annual number of housing starts would be if the current month'

month’s pace continued for an entire year.10

13

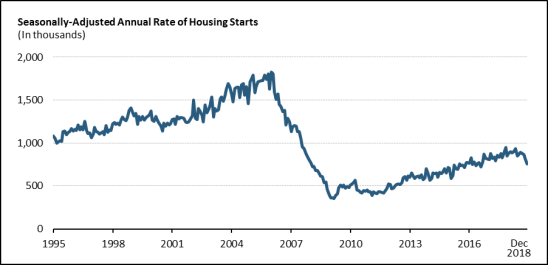

Figure 4 shows the seasonallyseasonal y adjusted annual rate of starts on one-unit homes for each month from January 1995 through December 2018.11 Housing starts for single-family homes fell during the housing market turmoil, reflecting decreased home purchase demand. In recent July 2020.14 Housing starts for single-family homes fel during the

9 For example, see HUD’s U.S. Housing Market Conditions National Housing Market Summary, 1st Quarter 2020, June 2020, p. 3, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/NationalSummary_1Q20.pdf.

10 For example, see Freddie Mac, The Major Challenge of Inadequate U.S. Housing Supply, Economic & Housing Research Insight, December 2018, http://www.freddiemac.com/fmac-resources/research/pdf/201811-Insight-06.pdf and The Housing Supply Shortage: State of the States, Economic & Housing Research Insight, February 2020, http://www.freddiemac.com/fmac-resources/research/pdf/202002-Insight -12.pdf.

11 For example, see Freddie Mac, The Housing Supply Shortage: State of the States, Economic & Housing Research Insight, February 2020, p. 3, http://www.freddiemac.com/fmac-resources/research/pdf/202002-Insight -12.pdf; Jenny Schuetz, The Goldilocks problem of housing supply: Too little, too m uch, or just right? , Brookings Institution, December 14, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-goldilocks-problem-of-housing-supply-too-little-too-much-or-just-right/; and Alan Mallach, The Em pty House Next Door: Understanding and Reducing Vacancy and Hypervacancy in the United States, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2018, pp. 22 -26, https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/empty-house-next -door-full.pdf. 12 HUD, U.S. Housing Market Conditions National Housing Market Summary, 1st Quarter 2020, June 2020, pp. 1-3, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/NationalSummary_1Q20.pdf.

13 T he Census Bureau defines the seasonally adjusted annual rate as “the seasonally adjusted monthly value multiplied by 12” and notes that it “is neither a forecast nor a projection; rather it is a description of the rate of building permits, housing starts, housing completions, or new home sales in the particular month for which they are calculated.” See U.S. Census Bureau, “New Residential Construction,” at https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/definitions/index.html#s. 14 T he number of housing starts is consistently higher than the number of new home sales. T his is prima rily because housing starts include homes that are not intended to be put on the for -sale market, such as homes built by the owner of the land or homes built for rental. See the U.S. Census Bureau, “Comparing New Home Sales and New Residential

Congressional Research Service

6

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, reflecting decreased home purchase demand. In recent years, levels of new construction have remained relatively low by historical standards, reflecting a variety of considerations including labor shortages and the cost of building.1215 Housing starts have general yhave generally been increasing since about 2012, but remain well wel below their levels from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s. For 2018, the seasonally2019, the seasonal y adjusted annual rate of housing starts averaged about 868893,000. In comparison, the seasonallyseasonal y adjusted annual rate of housing starts

exceeded 1 million mil ion from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s.

Single-family housing starts showed a significant drop as the pandemic began, though they have

begun to recover somewhat in the months since then.16 Single-family housing starts in July were

higher than in the previous July, though not as high as the months in late 2019 and early 2020.17

Figure 4. Housing Starts

By month; seasonal y By month; seasonally adjusted annual rate |

|

adjusted annual rate

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, New Residential Construction July 2020. Notes: Figure reflects |

High housing construction costs have led to a greater share of new housing being built at the more expensive end of the market over the last several years. To the extent that new homes are

Construction,” https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/salesvsstarts.html.

15 For example, see Freddie Mac, “What is Causing the Lean Inventory of Houses?,” Outlook Report, July 27, 2017, http://www.freddiemac.com/research/forecast/20170726_lean_inventory_of_houses.page. 16 T he Census Bureau notes that its data collection methods for this survey were impacted by the pandemic, though it says that “ ... processing and data quality were monitored throughout the month [of July] and quality metrics, including response rates, fell within normal ranges for these surveys.” For more information on how data collection was impacted, see U.S. Census Bureau, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) COVID-19’s Effect on the July 2020 New Residential Construction Indicator,” https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/pdf/newresconst_202007_notes.pdf. 17 For data on housing starts and other measures of residential construction (both single-family and multifamily), see U.S. Census Bureau, New Residential Construction, https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/index.html.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 12

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

concentrated at higher price points, supply and price pressures may be exacerbated for lower-

priced homes.18

Mortgage Market Composition

After a mortgage is originated, it might be held in a financial institution’s asset

Figure 5. Share of Mortgage Originations

portfolio, or it might be securitized through

by Type

one of several channels.19 Two government-

2019

sponsored enterprises (GSEs),. To the extent that new homes are concentrated at higher price points, supply and price pressures may be exacerbated for lower-priced homes.13

Mortgage Market Composition

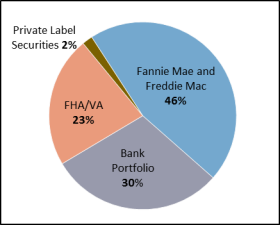

When a lender originates a mortgage, it can choose to hold that mortgage in its own portfolio, sell it to a private company, or sell it to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, two congressionally chartered government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bundle mortgages into , issue mortgage-backed securities and guarantee investors' ’ payments on those securities. Furthermore, a mortgage might be insured by a federal government Mortgages

that are insured or guaranteed by a federal agency, such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), are eligible to be included in mortgage-backed securities

guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Private companies can also issue mortgage-backed securities

without a government or GSE guarantee,

known as private label securities. The

Source: Figure created by CRS based on Inside Mortgage Finance data as reported in Urban Institute,

shares of mortgages that are provided

Housing Finance Policy Center, Housing Finance at a

through each of these channels may be

Glance: A Monthly Chartbook, February 2020, p. 8.

relevant to policymakers because of their

Notes: Figure shows share of first-lien mortgage

implications for mortgage access and

originations by dol ar volume.

affordability as wel as the federal

government’s exposure to risk.

As shown in Figure 5, a little underVeterans Affairs (VA). Most FHA-insured or VA-guaranteed mortgages are included in mortgage-backed securities that are guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, another government agency.14 The shares of mortgages that are provided through each of these channels may be relevant to policymakers because of their implications for mortgage access and affordability as well as the federal government's exposure to risk.

As shown in Figure 5, over two-thirds of the total dollar volume of mortgages originated

was either backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (4643%) or guaranteed by a federal agency such as FHA or VA (2319%) in 2018. Nearly2019. Over one-third of the dollar volume of mortgages originated was held in bank portfolios, while close to 2% was included in a private-label security without

government backing.

The shares of mortgage originations backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and held in bank portfolios are roughly similar to their respective shares in the early 2000s. The share of private-label securitization has been, and continues to be, small smal since the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, while the FHA/VA share is higher than it was in the early and mid-2000s.1520 The share

of mortgages insured by FHA or guaranteed by VA was low by historical standards during that

18 For example, see Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, State of the Nation’s Housing, 2019, p. 8, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_ State_of_the_Nations_Housing_2019.pdf ; and Jung Hyun Choi, Laurie Goodman, and Bing Bai, “Four ways today’s high home prices affect the larger economy,” Urban Institute, Urban Wire blog, October 11, 2018, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/four-ways-todays-high-home-prices-affect -larger-economy.

19 For more information on different types of mortgages and mortgage securitization channels, see CRS Report R42995, An Overview of the Housing Finance System in the United States. 20 See Urban Institute, Housing Finance Policy Center, Housing Finance at a Glance: A Monthly Chartbook, July 2020, p. 8, for a graph showing mortgage market composition since 2001 .

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 13

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

of mortgages insured by FHA or guaranteed by VA was low by historical standards during that time period as many households opted for other types of mortgages, including subprime mortgages.

mortgages. Rental Housing Markets

As has been the case in owner-occupied housing markets, affordability has been a prominent concern in rental markets in recent years. In the years since the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, the number and share of renter households has increased, leading to lower rental vacancy rates and higher rents in many markets.

The extent to which these trends in rents and vacancies

wil continue in light of the pandemic and related policy responses—including the imposition of

various eviction moratoria discussed later in this report—is unclear.

Share of Renters

Share of Renters

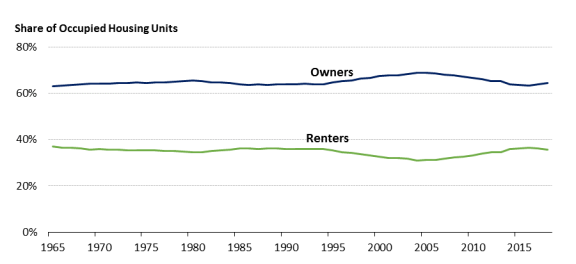

The housing and mortgage market turmoil of the late 2000s led to a substantial decrease in the homeownership rate and a corresponding increase in the share of households who rent their homesrenter households. As shown in

Figure 6, the share of renters increased from about 31% in 2005 and 2006 to a high of about 36.6% in 2016, before decreasing slightly to 36.1% in 2017 and continuing to decline to 35.6% in 2018beginning to decrease and reaching 35.4% in 2019. The homeownership rate correspondingly fell fel from a high of 69% in the mid-2000s to 63.4% in 2016, before rising to 63.9% in 2017 and continuing to rise to 64.4% in 2018.16

The overall number of occupied housing units also increased over this time period, from nearly 110 mil ion 110 million in 2006 to 121 million in 2018123 mil ion in 2019; most of this increase has been in renter-occupied units.1722 The number of renter-occupied units increased from about 34 millionmil ion in 2006 to about 43 million in 2018. The number of owner-occupied housing units fell from about 75 million units in 2006 to about 74 million in 2014, but has since increased to about 78 million units in 2018.

44

21 U.S. Census Bureau, Housing Vacancies and Homeownership, Annual Statistics, http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/prevann.html.

22 U.S. Census Bureau, Housing Vacancies and Homeownership, Historical T ables, T able 7, “Annual Estimates of the Housing Inventory: 1965 to Present,” http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/histtabs.html.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 14 link to page 14

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

mil ion in 2019. The number of owner-occupied housing units fel from about 75 mil ion units in

2006 to about 74 mil ion in 2014, but has since increased to about 79 mil ion units in 2019.

In general, it is too early to know how the COVID-19 pandemic may influence the share of

households who rent or own their homes, as it wil take time for the effects of the pandemic on

owners and renters to fully play out and be reflected in the data.23

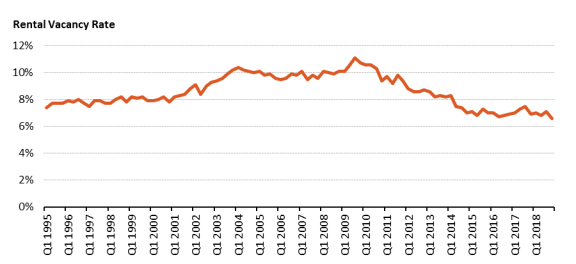

Rental Vacancy Rates

Rental Vacancy Rates

The higher number and share of renter households has had implications for rental vacancy rates and rental housing costs. More renter households increases competition for rental housing, which

may in turn drive up rents if there is not enough new rental housing created (whether through new

construction or conversion of owner-occupied units to rental units) to meet the increased demand.

As shown inin Figure 7, the rental vacancy rate has generallygeneral y declined in recent years and was under 7

6.4% at the end of 2018.

2019. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rental vacancy rates

is unclear, in part because the pandemic has affected more recent data collection for this survey.24

Figure 7. Rental Vacancy Rates

Q1 1995–Q4 2019

Q1 1995–Q4 2018 |

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Housing Vacancies and |

histtabs.html.

23 T he pandemic has impacted data collection for this survey, affecting the comparabilit y of the 2020 quarterly dat a to previous periods. See, for example, Census Bureau, Frequently asked questions: The im pact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandem ic on the Current Population Survey/Housing Vacancy Survey (CPS/HVS) , https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/qtr220/impact_coronavirus_20q2.pdf; and McCue, Daniel, “ Buyer Beware: A Cautionary Note on the Most Recent Homeownership Data from HVS,” Joint Cen ter for Housing Studies of Harvard University, blog post, August 10, 2020, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/buyer-beware-a-cautionary-note-on-the-most -recent -homeownership-data-from-hvs/.

24 See footnote 23 for more on how the pandemic has affected data collection for this survey.

Congressional Research Service

10

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Rental Housing Affordability

Rental Housing Affordability

Rental housing affordability is impacted by a variety of factors, including the supply of rental housing units available, the characteristics of those units (e.g., age and amenities), and the demand for available unitsavailable units, and renter incomes. New housing units have been added to the rental stock in recent years through both construction of new rental units and conversions of existing owner-

occupied units to rental housing. However, the supply of rental housing has not necessarily kept pace with the demand, particularly among lower-cost rental units, and low vacancy rates have been especially

been especial y pronounced in less-expensive units.18

25

The increased demand for rental housing, as well wel as the concentration of new rental construction in higher-cost units, has led to increases in rents in recent years. Median renter incomes have also been increasing for the last several years, at times outpacing increases in rents. However, over the longer term, median rentsRents have increased faster than renter incomes, reducing rental affordability.19

26 Rising rental costs and renter incomes that are not keeping up with rent increases over the long term can contribute to housing affordability problems

chal enges, particularly for households with lower incomes. Under one common

Under the most commonly used definition, housing is considered to be affordable if a household is paying no more than 30% of its income in housing costs. Under this definition, householdsHouseholds that pay more than 30% are considered to be cost-burdened, and those that pay more than 50% are considered to be

severely cost-burdened.

The overall The overal number of cost-burdened renter households has increased from 14.8 mil ion 14.8 million in 2001 to 20.5 million in 2017, although the 20.5 million in 2017 represented a decrease from 20.8 million in 2016 and over 21 million in 2014 and 2015.208 mil ion in 2018, or about 47% of al renters.27 (Over this time period, the overal the overall number of renter households has increased as wellwel .) While housing cost burdens can affect households of all al income levels, and have been growing among middle-income households,28 income levels, they are most prevalent among the lowest-income households. In 20172018, 83% of

renter households with incomes below $15,000 experienced housing cost burdens, and 72% experienced severe cost burdens.2129 A shortage of lower-cost rental units that are both available and affordable to extremely low-income renter households (households that earn no more than

30% of area median income), in particular, contributes to these cost burdens.30

25 For example, see Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, America’s Rental Housing 2020, pp. 3, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf. 26 See HUD, Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Housing Market Conditions National Housing Market Sum m ary 1st Quarter 2020, June 2020, pp. 5-6, and underlying data available at https://www.huduser.gov/portal/ushmc/quarterly_commentary.html. Data on median rents reflect median rents for recent movers less the cost of utilities. For more information on data sources used, see HUD Office of Policy Development and Research, HUD’s New Rental Affordability Index, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-trending-110716.html.

27 Joint Center for Housing Studies, America’s Rental Housing 2020, Appendix T ables, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020, showing Joint Center for Housing Studies tabulations of American Community Survey data. 28 See, for example, Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, “America’s Rental Affordability Crisis is Climbing the Income Ladder,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, blog post, January 31, 2020, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/americas-rental-affordability-crisis-is-climbing-the-income-ladder/.

29 Joint Center for Housing Studies, America’s Rental Housing 2020, Appendix T ables, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020, showing Joint Center for Housing Studies tabulations of American Community Survey data. 30 See Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, America’s Rental Housing 2020, p. 31, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf; and National Low Income Housing Coalition, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Hom es, March 2020, available at https://reports.nlihc.org/gap.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 17 Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Housing The COVID-19 pandemic that began in early 2020 is having wide-ranging effects on public health and the economy. The pandemic has led to a number of housing-related concerns, including, among other things, concerns about housing insecurity among both renters and

homeowners.

Congress and federal agencies have responded to these concerns by taking a variety of actions. In general, these actions have included providing additional federal funding for several housing programs, establishing temporary protections for certain renters and homeowners, and taking

actions intended to support the housing finance system more broadly.

As the economy has entered recession and some temporary assistance measures have begun to expire, many policymakers and others have cal ed for additional federal action. Numerous bil s

that would further address COVID-19-related housing issues have been introduced and some

have been considered.

This section of the report discusses the effects of COVID-19 on housing and federal responses to

date.

COVID-19 and Effects on Housing The pandemic has led to increased housing insecurity as many households experience income disruptions. Such disruptions can lead to difficulties making rent or mortgage payments. According to data from the Census Bureau’s Pulse Survey, and as shown in Figure 8, 21% of renters and 13% of owners reported having not made the current month’s housing payment as of the week that ended on July 21. (These figures include those with deferred payments.) Larger

shares (35% and 17%, respectively) expected that they would not be able to pay the following

month.31

31 T hese figures reflect CRS calculations based on data in the Week 12 Household Pulse Survey, available at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html. T hey include those who missed last month’s payment or whose last month payment was deferred, and those who have slight or no confidence that they will make next month’s payment or anticipate that next month’s payment will be deferred.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 5

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Figure 8. Renters and Owners Having Difficulty Making Housing Payments

For the week ending July 21, 2020

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey for Week 12 (July 16-July 21).

Thus far, many households have been protected by federal and state or local eviction or foreclosure moratoriums. It is not yet clear to what extent renters and homeowners wil be able to make their rent or mortgage payments or make up missed payments when protections expire.

(The end dates for eviction and foreclosure protections depend on a variety of factors, including

the specific protection in question and whether any extensions are issued.)

As described in the “Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions” section, data are beginning to

emerge about the trajectory of national housing market indicators during the first few months of the pandemic. However, the full effects of COVID-19 on housing markets wil not be known for some time. Such effects wil depend on a variety of factors, including the duration of the public health threat and the timing and pattern of economic recovery, and involve a high degree of uncertainty. Impacts may vary across the country based on differences in local housing markets as

wel as geographic variation in the prevalence of COVID-19 and local responses. The impacts are likely to vary across demographic groups, due in part to existing differences in housing conditions as wel as the uneven distribution of the health and economic consequences of the

pandemic.32

32 For example, see Sharon Cornelissen and Alexander Hermann, A Triple Pandemic? The Economic Impacts of COVID-19 Disproportionately Affect Black and Hispanic Households, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, July 7, 2020, https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/a-triple-pandemic-the-economic-impacts-of-covid-19-disproportionately-affect-black-and-hispanic-households/; and Michael Neal and Alanna McCargo, How Econom ic Crises and Sudden Disasters Increase Racial Disparities in Hom eownership, T he Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center, June 1, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/how-economic-crises-and-sudden-disasters-increase-racial-disparities-homeownership.

Congressional Research Service

13

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Federal Housing Responses to COVID-19 On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed into law the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security Act (CARES Act; P.L. 116-136), a COVID-19 response package that included, among many other things, several provisions related to housing. These included certain temporary protections for renters in properties with federal assistance or federal bac king and homeowners

with federally backed mortgages, as wel as increased funding for several housing programs.

Both prior to and since the passage of the CARES Act, federal agencies have taken various administrative actions to address housing concerns related to COVID-19. In addition, on August 8, 2020, President Trump signed an Executive Order related to COVID-19 and housing.33 The Executive Order directed several federal agencies to examine authorities or resources that they

may be able to use to further assist tenants or homeowners affected by COVID-19 to help them avoid eviction or foreclosure. It did not itself provide any new resources or implement any additional actions related to evictions and foreclosures. (For more information on this Executive Order, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10532, President Trump’s Executive Actions on Student Loans, Wage Assistance, Payroll Taxes, and Evictions: Initial Takeaways.) The Executive Order,

among other things, directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to consider whether measures to temporarily pause evictions were necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19 between states. On September 4,

2020, the CDC announced a national eviction moratorium to last until the end of the year.

Lawmakers have also introduced a variety of additional bil s to further address housing issues

related to COVID-19, though as of the date of this report none has been enacted.

Federal Interventions Related to Rental Housing

While al types of households may be at risk of housing instability due to COVID-19, renters may

be particularly vulnerable. This is both because more financial y vulnerable populations are more likely to be renters, and because the process for evicting a household from a rental unit is general y faster than the process of foreclosing on a mortgage. As such, there have been several

policy interventions aimed specifical y at aiding renters.

CARES Act Rental Housing Provisions

To protect renters experiencing COVID-19-related financial hardships, the CARES Act included a 120-day moratorium on eviction filings for tenants in rental properties with federal assistance or federal y related financing, as wel as a prohibition on charging late fees for nonpayment of rent for the same time period. These protections were designed to al eviate the economic and public health consequences of tenant displacement during the pandemic. They supplemented temporary

eviction moratoria and rent freezes implemented in states and cities by governors and local officials using emergency powers. The CARES Act eviction moratorium expired on July 24, though the law also required that landlords provide tenants with at least 30 days’ notice before requiring tenants to vacate a covered property after the moratorium expired. Therefore, tenants

should not have been required to leave covered rental units until at least August 23.

33 Executive Order on Fighting the Spread of COVID-19 by Providing Assistance to Renters and Homeowners, issued on August 8, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-fighting-spread-covid-19-providing-assistance-renters-homeowners/.

Congressional Research Service

14

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Separate from the eviction moratorium, the CARES Act also included provisions related to forbearance for federally backed multifamily mortgages (discussed further below). The CARES Act provided that multifamily mortgage borrowers receiving forbearance must provide certain tenant protections during the forbearance period. Namely, owners cannot evict tenants for nonpayment of rent or charge late fees for the duration of the forbearance. Therefore, some tenants may benefit from federal protection from eviction because they live in a property with a

federal y backed multifamily mortgage subject to a forbearance agreement.

In addition, other assistance provided in the CARES Act, such as federal unemployment

insurance supplemental payments (which have now expired), likely helped renters make housing payments and therefore avoid eviction. While this assistance was not specific to housing,

households could use it to help maintain housing in light of income disruptions.

For more information on CARES Act protections for renters, see the following:

CRS Insight IN11320, CARES Act Eviction Moratorium.

CDC’s National Eviction Moratorium

On September 4, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published an order in the Federal Register implementing a national eviction moratorium through December 31, 2020.34 The moratorium protects certain tenants from eviction for non-payment of rent. The CDC relied on broad authority that it has to take actions to prevent the spread of communicable diseases between states to implement this moratorium.35 In the Federal Register notice announcing it, the CDC

described the public health risks posed by evictions and their effects during a pandemic.

Unlike the CARES Act eviction moratorium, the CDC’s eviction moratorium potential y applies

to renters in any rental property, not just those with federal financing or federal assistance. While the CARES Act moratorium applied automatical y to renters in covered properties, the CDC moratorium requires eligible renters to provide landlords a document that attests to their

eligibility. Eligible renters must attest that they

meet income eligibility criteria; namely, that they either 1) expect to have

incomes no higher than $99,000 ($198,000 if filing a joint tax return) in 2020, 2) were not required to report income to the Internal Revenue Service in 2019, or 3) received an Economic Impact Payment under Section 2201 of the CARES Act;

have made “best efforts to obtain al available government assistance” to pay

rent;

are unable to pay full rent due to certain specified hardships; are making “best efforts” to make partial payments as close as possible to the full

payment as circumstances permit; and

would likely become homeless, move to a homeless shelter, or move into housing

with others in close quarters if evicted due to a lack of available housing options.

Renters must also attest that they understand that the order does not relieve them of the obligation

to pay rent, and does not prohibit landlords from charging fees, penalties, or interest in 34 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services, “T emporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19,” 85 Federal Register 55292-55297, September 4, 2020. 35 T he CDC’s order cites its authority under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. §264) and regulations at 42 CFR 70.2. See the Federal Register notice for the CDC’s discussion of the risk s that evictions pose to public health.

Congressional Research Service

15

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

accordance with applicable contracts. (In contrast, the CARES Act prohibited landlords from charging fees, penalties, or interest during the eviction moratorium.) The CDC moratorium does

not supersede state or local eviction moratoria that provide greater protections.

While the CARES Act did not explicitly include any penalties for noncompliance, the CDC’s order specifies potential penalties (fines and/or jail time) for landlords who do not comply. Renters who are not truthful in their attestations could be found guilty of perjury and be subject to

associated penalties.

The CDC’s national eviction moratorium order raises a variety of questions and is the subject of legal chal enges.36 In addition to questions surrounding the CDC’s authority to issue such a moratorium, there are questions around issues such as how enforcement is being carried out and how many renters may seek protection. Industry groups representing property owners have raised

concerns about the impact of the eviction moratorium on owners, who may have difficulty covering the costs of the property if tenants are unable to pay rent.37 Tenant advocates, while general y welcoming the moratorium, have also noted that it does not help tenants pay rent and have raised concerns about what happens to renters when the moratorium ends.38 Both owner and

tenant advocates have cal ed for federal rental assistance to help tenants make rent payments.39

For more information on the CDC’s eviction moratorium, see CRS Insight IN11516, Federal

Eviction Moratoriums in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Federal Interventions Related to Mortgages

The CARES Act requires mortgage servicers to grant forbearance requests for borrowers with federal y backed mortgages who are experiencing a financial hardship related to COVID-19.40 Mortgage forbearance al ows a household to reduce or suspend mortgage payments for an agreed-upon period of time, but it does not forgive the amounts owed; borrowers and mortgage servicers

must negotiate an agreement for the repayment of the missed amounts.

Under the CARES Act, forbearance for federal y backed single-family mortgages can be for up to 360 days (an initial period of up to 180 days, with an extension of up to an additional 180 days). For federally backed multifamily mortgages, the forbearance can be for up to 90 days (an initial

period of up to 30 days, with two possible 30-day extensions).41 Federal y backed mortgages 36 See, for example, Brown v. Azar et al., 1:20-CV-03702, N.D. Ga. 37 See, for example, National Multifamily Housing Council, “Statement by NMHC President Doug Bibby on Administration’s Enactment of Federal Eviction Moratorium,” September 1, 2020, https://www.nmhc.org/news/press-release/2020/statement-by-nmhc-president -doug-bibby-on-administrations-enactment -of-federal-eviction-moratorium/.

38 See, for example, National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Statement from National Low Income Housing Coalition President and CEO Diane Yentel on the White House Morato rium on Evictions for Nonpayment of Rent,” September 1, 2020, https://nlihc.org/news/statement-national-low-income-housing-coalition-president -and-ceo-diane-yentel-white-house. 39 Letter from California Housing Consortium et al., August 21, 2020, https://www.irem.org/File%20Library/GlobalNavigation/Advocacy/CoalitionLetters/2020/08212020RentalAssistanceCoalitionLetter.pdf.

40 Prior to passage of the CARES Act, the federal agencies that back mortgages and the government -sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had each released guidance reminding mortgage servicers of existing options to help borrowers having difficulties making mortgage payments, including forbearance, and encouraging or requiring temporary suspensions on foreclosures. While much of this guidance was similar to the provisions included in the CARES Act, the specifics varied by agency.

41 FHFA has since announced the availability of forbearance for multifamily mortgages backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac for up to an additional three months; tenant protections must apply for the duration of the forbearance. See FHFA, “FHFA Provides T enant Protections,” press release, June 29, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Provides-T enant -Protections.aspx. HUD has also stated that FHA-insured multifamily mortgages in

Congressional Research Service

16

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

include those insured, guaranteed, or originated by a federal agency, such as HUD, USDA, or VA, or purchased or securitized by two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They are estimated to constitute approximately 70% of outstanding single-family

mortgages.42

The CARES Act also temporarily suspended foreclosures on federally backed single-family mortgages. The CARES Act foreclosure moratorium was in effect for 60 days from March 18, 2020; however, the federal agencies that back mortgages and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have al since announced extensions. As of the date of this report, these entities had extended the

foreclosure moratorium for mortgages they back through December 31, 2020.43

Federal agencies that back mortgages, such as the Federal Housing Administration, and GSEs such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (along with their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance

Agency, or FHFA44) have also taken additional steps to assist borrowers and other mortgage

market participants.45 These steps have included the following:

The CARES Act was silent on this question. Several of the federal entities involved in

mortgages have stated that borrowers with mortgages they back who are not able to repay the missed amounts in a lump sum at the end of the forbearance wil be offered other repayment options,46 and have announced specific options for deferring the missed

amounts to the end of the loan term.47

forbearance may be able to have forbearance periods extended, and that tenant protections will apply during any extended forbearance. See HUD Housing Notice H 20 -07, “ Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Eviction Moratorium,” issued July 1, 2020, p. 3, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/20-07hsgn.pdf.pdf. 42 See, for example, Karan Kaul and Laurie Goodman, “T he Price T ag for Keeping 29 Million Families in T heir Homes: $162 Billion,” T he Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Policy Center, March 27, 2020, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/price-tag-keeping-29-million-families-their-homes-162-billion.

43 FHA Mortgagee Letter 2020-27, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/2020-27hsgml.pdf; FHFA, “FHFA Extends Foreclosure and REO Eviction Moratoriums,” https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Extends-Foreclosure-and-REO-Eviction-Moratoriums.aspx; VA Circular 26-20-30, https://www.benefits.va.gov/HOMELOANS/documents/circulars/26-20-30.pdf; USDA, “ USDA Implements Immediate Measures to Help Rural Residents, Businesses and Communities Affected by COVID -19,” updated August 28, 2020, https://www.rd.usda.gov/sites/default/files/COVID19_CUMULAT IVE_StakeholderNotification_WEEKLY_Aug28.pdf ; and HUD Office of Public and Indian Housing Dear Lender Letter 2020-10, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/PIH/documents/DLL_2020-10_Eviction_Moratorium_and_Loan_Processing_Flexibilities_Extension.pdf .

44 T he Federal Housing Finance Agency is the regulator and conservator for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as well as the regulator of a third housing GSE, the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system. T he FHLBs have also taken steps to address COVID-19-related issues; see the FHLB website at https://fhlbanks.com/covid-19/. For more information on the FHLBs in general, see CRS Report R46499, The Federal Hom e Loan Bank (FHLB) System and Selected Policy Issues. 45 Administrative actions and guidance related to the pandemic continue to evolve. Many federal agencies involved in housing post pandemic-related guidance in a centralized location. For example, see HUD’s webpage on coronavirus resources at https://www.hud.gov/coronavirus, the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s webpage on coronavirus assistance information at https://www.fhfa.gov/Homeownersbuyer/MortgageAssistance/Pages/Coronavirus-Assistance-Information.aspx, and USDA’s Rural Development COVID-19 response page at https://www.rd.usda.gov/coronavirus.

46 See “CARES Act Forbearance Fact Sheet for Borrowers with FHA, VA, or USDA Loans,” https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/SFH/documents/IACOVID19FBFactSheetConsumer.pdf; and FHFA, “ ‘No Lump Sum Required at the End of Forbearance’ says FHFA’s Calabria,” press release, April 27, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/No-Lump-Sum-Required-at-the-End-of-Forbearance-says-FHFAs-Calabria.aspx. 47 See FHA Mortgagee Letter 2020-06, “FHA’s Loss Mitigation Options for Single Family Borrowers Affected by the Presidentially-Declared COVID-19 National Emergency in Accordance with the CARES Act,” April 1, 2020,

Congressional Research Service

17

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

Temporary Mortgage Origination Flexibilities: Certain aspects of the mortgage

origination process present chal enges during the pandemic. In response, federal entities have made temporary changes to certain requirements for mortgages that they back in order to minimize the effects on mortgage origination and home buying. These changes include al owing for alternatives to interior home appraisals in some circumstances and providing flexibilities related to the process for re-verifying a borrower’s employment

before closing.48 FHA and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have each also announced temporary policies that al ow them to insure or purchase, respectively, mortgages that otherwise meet their requirements but are in forbearance.49 (Usual y, mortgages that are already in forbearance are not eligible for FHA insurance or purchase by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.) To help balance the increased risk that these mortgages pose to these

entities, their acceptance of these mortgages is subject to certain conditions.50 Some lawmakers have raised concerns about these conditions, however, and their potential

impact on mortgage credit access.51

Support for Mortgage Servicers: Mortgage servicers are often required to advance

payments to investors in mortgage-backed securities even if the borrower has not made their payments on time, including in the case of forbearance. Large volumes of delinquent payments or mortgage forbearances can therefore cause liquidity issues for some servicers.52 In response, Ginnie Mae and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have each taken

certain steps to address potential servicer liquidity issues for mortgages that they back.53

https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/ documents/20-06hsngml.pdf; FHA Mortgagee Letter 2020-22, “ FHA’s COVID-19 Loss Mitigation Options,” https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/20-22hsgml.pdf; and FHFA, “FHFA Announces Payment Deferral as New Repayment Option for Homeowners in COVID-19 Forbearance Plans,” press release, May 13, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Announces-Payment-Deferral-as-New-Repayment -Option-for-Homeowners-in-COVID-19-Forbearance-Plans.aspx. 48 See, for example, FHFA, “FHFA Directs Enterprises to Grant Flexibilities for Appraisal and Employment Verifications,” press release, March 23, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Directs-Enterprises-to-Grant-Flexibilities-for-Appraisal-and-Employment-Verifications.aspx; and HUD, “ Re-verification of Employment and Exterior-Only and Desktop-Only Appraisal Scope of Work Options for FHA Single Family Programs Impacted By COVID-19,” FHA Mortgagee Letter 2020-05, March 27, 2020, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/20-05hsgml.pdf. T he flexibilities provided in each of these documents were subsequently extended. 49 FHFA, “FHFA Announces that Enterprises will Purchase Qualified Loans in Forbearance to Keep Lending Flowing,” press release, April 22, 2020, https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Announces-that-Enterprises-will-Purchase-Qualified-Loans.aspx; and FHA Mortgagee Letter 2020-16, “ Endorsement of Mortgages under Forbearance for Borrowers Affected by the Presidentially -Declared COVID-19 National Emergency consistent with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,” https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/2020-16hsngml.pdf. As of the date of this report, FHA’s policy is in effect through November 30, 2020, and FHFA’s policy had been ext ended through October 31, 2020. 50 Ibid. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac charge additional fees for purchasing mortgages in forbearance, while FHA requires a lender to continue to bear some of the risk of such mortgages by signing a partial indemnification agree ment. 51 Letter from House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters et al. to HUD Secretary Benjamin S. Carson and FHFA Director Mark Calabria, June 25, 2020, https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/ltr_to_hud_and_fhfa_re_ef_6-25-20.pdf. Bills introduced in the House (H.R. 6794) and Senate (S. 4260) would prohibit FHA and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from imposing additional costs or other terms on such mortgages solely based on their forbearance status.

52 For more information on mortgage servicing considerations, see CRS Insight IN11377, Mortgage Servicing Rights and Selected Market Developm ents. 53 Ginnie Mae expanded access to the Pass T hrough Assistance Program (PT AP), through which Ginnie Mae lends money to servicers to make required advances if they cannot obtain funding through other sources. FHFA announced that Fannie Mae servicers would only be required to advance four months of principal and interest payments (this was

Congressional Research Service

18

Housing Issues in the 116th Congress

In addition, the Federal Reserve has agreed to purchase mortgage-backed securities to help provide liquidity and stability in the mortgage market.54 These purchases can facilitate the funding of mortgages, even if investors’ demand for mortgage-backed securities declines during

the pandemic. For more information, see the following:

CRS Insight IN11334, Mortgage Provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and

Economic Security (CARES) Act.

CRS Insight IN11316, COVID-19: Support for Mortgage Lenders and Servicers. CRS Insight IN11385, The Impact of COVID-19-Related Forbearances on the

Federal Mortgage Finance System.

Increased Funding for Housing Programs