Banking: Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL)

Some observers asserted that leading up to the financial crisis of 2007-2009 banks did not have sufficient credit loss reserves or capital to absorb the resulting losses and as a consequence supported additional government intervention to stabilize the financial system. In its legislative oversight capacity, Congress has devoted attention to strengthening the financial system in an effort to prevent another financial crisis and avoid putting taxpayers at risk. However, some Members of Congress have expressed concern that financial reforms have been unduly burdensome, reducing the availability and affordability of credit. Congress has delegated authority to the bank regulators and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) to address credit loss reserves. FASB promulgates the U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP), which provides the framework for financial reporting by banks and other entities.

Credit loss reserves help mitigate the overstatement of income on loans and other assets by accounting for future losses. Credit losses are often very low shortly after loan origination, subsequently rising in the early years of the loan, and then tapering to a lower rate of credit loss until maturity. Consequently, a firm’s financial statements might not accurately reflect potential credit losses at loan inception. During the seven years leading up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the loan values held by the U.S. commercial banking system increased by 85%, whereas the credit loss reserves increased by only 21%. The ratio of loss reserves prior to the financial crisis was as low as 1.16% in 2006 and was more than 3.70% near the end of the crisis in early 2010.

In response to banks’ challenges during and after the crisis, in June 2016, FASB promulgated a new credit loss standard—Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL). The new standard is expected to result in greater transparency of expected losses at an earlier date during the life of a loan. Early recognition of expected losses might not only help investors, but might also create a more stable banking system. CECL requires consideration of a broader range of reasonable and supportable information in determining the expected credit loss, including current and future economic conditions. In addition to loans, CECL also applies to a broad range of other financial products. The expected lifetime losses of loans and certain other financial instruments are to be recognized at the time a loan or financial instrument is recorded. All public companies are required to issue financial statements that incorporate CECL for reporting periods beginning after December 15, 2019. Although adherence to CECL is required for all public companies, it is expected to have a more significant effect on the banking industry. The change to credit loss estimates under CECL is considered by some to be the most significant accounting change in the banking industry in 40 years.

The banking regulators (Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) have issued preliminary guidance on CECL implementation. Banking regulators have also proposed changing the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL) to Allowance for Credit Loss (ACL) as a newly defined term. The change to ACL is to reflect the broader range of financial products that will be subject to credit loss estimates under CECL.

During congressional hearings, banking industry professionals have raised several concerns about CECL. According to one estimate, the transition to CECL will likely result in an increase in loan loss reserves of between $50 billion and $100 billion for banks. As these projections are in aggregate across the banking industry, some banks might need to significantly increase their credit reserves whereas others might need to adjust less.

To mitigate the effect of CECL, regulators have given banks the option of phasing in the increased credit reserves over three years. In addition, the Federal Reserve has delayed stress tests that incorporate CECL for the largest banking organizations until 2021. Banks are expected to incur additional costs of developing new credit loss models and costs of implementation. Banks may need to retain historical information on more financial products to estimate credit losses under CECL. Adopting CECL may require upgrading existing hardware and software or paying higher fees to third-party vendors for such services. Participants in recent congressional hearings have raised concerns about CECL implementation issues. The difference in how credit loss estimates are calculated based on CECL and international accounting standards could potentially disadvantage U.S. banks, but CECL is considered less complex to implement.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises, are also to be subject to CECL credit loss estimates as they are subject to private-sector GAAP requirements even though they are currently in conservatorship under the Federal Housing Financing Agency.

Banking: Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Current Expected Credit Loss

- Incurred Loss Model and CECL

- CECL Implementation Dates

- Policy Issues

- Banking Industry

- Effects on Banks

- Implementation Challenges

- Increased Capital Costs for Banks

- Stress Tests for Banks

- Comparison of U.S. CECL and IFRS 9

- Potential Effects on Governmental Entities

Figures

Summary

Some observers asserted that leading up to the financial crisis of 2007-2009 banks did not have sufficient credit loss reserves or capital to absorb the resulting losses and as a consequence supported additional government intervention to stabilize the financial system. In its legislative oversight capacity, Congress has devoted attention to strengthening the financial system in an effort to prevent another financial crisis and avoid putting taxpayers at risk. However, some Members of Congress have expressed concern that financial reforms have been unduly burdensome, reducing the availability and affordability of credit. Congress has delegated authority to the bank regulators and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) to address credit loss reserves. FASB promulgates the U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP), which provides the framework for financial reporting by banks and other entities.

Credit loss reserves help mitigate the overstatement of income on loans and other assets by accounting for future losses. Credit losses are often very low shortly after loan origination, subsequently rising in the early years of the loan, and then tapering to a lower rate of credit loss until maturity. Consequently, a firm's financial statements might not accurately reflect potential credit losses at loan inception. During the seven years leading up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the loan values held by the U.S. commercial banking system increased by 85%, whereas the credit loss reserves increased by only 21%. The ratio of loss reserves prior to the financial crisis was as low as 1.16% in 2006 and was more than 3.70% near the end of the crisis in early 2010.

In response to banks' challenges during and after the crisis, in June 2016, FASB promulgated a new credit loss standard—Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL). The new standard is expected to result in greater transparency of expected losses at an earlier date during the life of a loan. Early recognition of expected losses might not only help investors, but might also create a more stable banking system. CECL requires consideration of a broader range of reasonable and supportable information in determining the expected credit loss, including current and future economic conditions. In addition to loans, CECL also applies to a broad range of other financial products. The expected lifetime losses of loans and certain other financial instruments are to be recognized at the time a loan or financial instrument is recorded. All public companies are required to issue financial statements that incorporate CECL for reporting periods beginning after December 15, 2019. Although adherence to CECL is required for all public companies, it is expected to have a more significant effect on the banking industry. The change to credit loss estimates under CECL is considered by some to be the most significant accounting change in the banking industry in 40 years.

The banking regulators (Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) have issued preliminary guidance on CECL implementation. Banking regulators have also proposed changing the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL) to Allowance for Credit Loss (ACL) as a newly defined term. The change to ACL is to reflect the broader range of financial products that will be subject to credit loss estimates under CECL.

During congressional hearings, banking industry professionals have raised several concerns about CECL. According to one estimate, the transition to CECL will likely result in an increase in loan loss reserves of between $50 billion and $100 billion for banks. As these projections are in aggregate across the banking industry, some banks might need to significantly increase their credit reserves whereas others might need to adjust less.

To mitigate the effect of CECL, regulators have given banks the option of phasing in the increased credit reserves over three years. In addition, the Federal Reserve has delayed stress tests that incorporate CECL for the largest banking organizations until 2021. Banks are expected to incur additional costs of developing new credit loss models and costs of implementation. Banks may need to retain historical information on more financial products to estimate credit losses under CECL. Adopting CECL may require upgrading existing hardware and software or paying higher fees to third-party vendors for such services. Participants in recent congressional hearings have raised concerns about CECL implementation issues. The difference in how credit loss estimates are calculated based on CECL and international accounting standards could potentially disadvantage U.S. banks, but CECL is considered less complex to implement.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises, are also to be subject to CECL credit loss estimates as they are subject to private-sector GAAP requirements even though they are currently in conservatorship under the Federal Housing Financing Agency.

Introduction

Some observers asserted that leading up to the financial crisis of 2007-2009 banks did not have sufficient credit loss reserves or capital to absorb the losses and as a consequence supported additional government intervention to stabilize the financial system.1 In an effort to prevent future government intervention and to avoid putting taxpayers at risk, Congress has passed legislation and maintained oversight of rulemaking by regulatory agencies to help mitigate the risk to taxpayers.

In its legislative capacity, Congress has devoted attention to strengthening the financial system in an effort to prevent another financial crisis by passing legislation. Congress approved the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (the Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) to address some of the weaknesses in regulation that contributed to the financial system's instability. Subsequently, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) was enacted in part to provide relief to financial firms from regulations that Congress believed to be excessively burdensome.

In its oversight capacity, while maintaining oversight of reforms implemented through the regulatory agencies, Congress has delegated authority to the bank regulators and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) to determine minimum credit loss reserves and the current expected credit loss (CECL) implementation. Credit loss reserves help mitigate the overstatement of income on loans and other assets by adjusting for potential future losses on related loans and other assets.

According to FASB,2 evidence from historical credit loss experience indicates that credit losses are not realized evenly throughout the life of a loan.3 Credit losses are often very low shortly after origination; subsequently, they rise in the early years of a loan, and then taper to a lower rate of credit loss until maturity.4 Consequently, a firm's financial statements might not accurately reflect the potential credit losses at loan inception.

U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), currently, require an incurred loss methodology to recognize credit losses on financial statements.5 Under the incurred loss method, (1) a bank must have a reason to believe that a loss is probable and (2) the bank must be able to reasonably estimate the loss.6 Any credit loss reserves set aside to absorb loan losses are, generally, estimated based on historical information and current economic events. The loss incurred on a loan cannot be recognized until the loss on a loan is probable, and the amount is estimable.7

In June 2016, FASB replaced the incurred loss methodology with the more forward-looking CECL methodology to provide more useful information on financial statements.8 CECL requires "consideration of a broader range of reasonable and supportable information" to determine the expected credit loss, including expected loss over the life of a loan or financial instrument by considering current and future expected economic conditions. The expected losses over the life of the financial instrument are to be recognized at the time the financial instrument is created.9 In adherence to FASB, banking regulators have begun a rulemaking process on CECL implementation.

This report primarily focuses on the effects of CECL on the banking industry, although CECL will also affect other financial institutions and sectors. The report first provides an overview of CECL, including a comparison between the incurred loss model and CECL, and then provides the CECL implementation timeline. The report concludes by discussing various policy issues surrounding CECL implementation and its effects on banks and other financial institutions. Although CECL will affect loans and other types of financial instruments, loans is used as a generic term to refer to all assets affected by CECL.

|

Key Concepts and Acronyms

|

Current Expected Credit Loss

Credit loss estimates based on CECL are projected to result in greater transparency of expected losses earlier in the life of the loan and improve a user's ability to understand changes to expected credit losses at each reporting period.12 Among other expected changes, FASB amended certain disclosure requirements but retained a significant portion of the previous disclosure requirements.13

|

FASB's Authority to Promulgate U.S. GAAP Although the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has the statutory authority to promulgate the accounting standards (GAAP) for the U.S. private sector, throughout its history, the SEC has relied on the private sector to establish and develop GAAP in the United States.14 Currently, the SEC recognizes the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) as the designated organization for establishing GAAP for the private sector.15 However, Congress has oversight over the SEC and annually appropriates its funding.16 |

CECL requirements are in effect beginning December 2019 for some companies; see Table 1 for the tiered implementation dates. CECL will affect firms that hold loans,17 debt securities, trade receivables, net investments in leases, off-balance-sheet credit exposures, reinsurance receivables, and any other financial assets that have a contractual right to receive cash payments. CECL will also apply to certain off-balance-sheet credit exposures. All Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filers,18 such as publicly traded companies and others required to be compliant with GAAP, must adopt the new CECL model for determining credit loss reserves.19

CECL will apply to all banking organizations, including national banks, state-member banks, state-nonmember banks of the Federal Reserve System, savings associations, foreign banking organizations, and top-tier banking holding companies, including U.S.-based savings and loan holding companies. The proposed changes are significant enough to affect the regulatory capital rules that the federal banking regulators—the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), collectively, the regulators—have initiated a "notice of proposed rulemaking," to address bank capital requirements.20 The National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) did not join in the joint rulemaking proposal with other financial regulators, but NCUA was part of the joint frequently asked questions issued by the other financial regulators.21 In their October 2017 press release, the regulators referred to a December 2006 policy statement22 that provides examples as the source document for factors that could be considered for determining CECL.23

Because CECL-based credit loss estimates require consideration of the potential loss over the life of an asset, credit losses on all existing loans and certain other assets are likely to be reevaluated. Upon initial adoption of CECL, the earlier recognition of losses might cause a onetime reduction in earnings.24 CECL will likely affect banks in various ways depending on how they currently model the allowance for loan and lease losses and other offset accounts. Each bank may apply different estimation methods to different pools of financial assets, but only one estimation method needs to be applied to each pool of financial assets.25 Although the regulators provide guidance on how CECL is to be implemented, they do not provide specific forecasts or models.

Currently, credit losses in the banking industry are referred to, generally, as Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL), or sometimes referred to as allowance for loans. Although ALLL is reflected on the balance sheet as an offset (a contra-asset) to the underlying asset and reduces the asset's value, the related credit losses are first expensed on the income statement.26

Incurred Loss Model and CECL

As previously discussed, incurred loss methodology is currently based on the probable threshold and incurred loss, which delays the recognition of credit losses. Changing the probable threshold and incurred loss requirements is not expected to change how much the credit loss is actually recognized, but only the timing of credit loss recognition. CECL requires the potential losses to be recorded at the time a bank recognizes the assets on its balance sheet.27 There will be a onetime adjustment to banks' earnings for existing loan portfolios to recognize the potential additional credit loss reserves under CECL.

Current U.S. GAAP is considered complex because it encompasses multiple credit impairment models. In contrast, CECL uses a single impairment measurement objective to be applied to all financial assets subject to credit loss estimates. Further, CECL does not specify a single method for measuring expected credit loss; instead, it allows any reasonable approach as long as it achieves the new GAAP objectives for credit loss estimates.28 As part of developing a CECL model, a firm is to consider reasonable and supportable forecasts to develop the lifetime expected credit losses while considering past events and current conditions.

CECL Implementation Dates

Early adopters of CECL may start issuing CECL-based financial statements for financial reporting periods after December 15, 2018. All public companies are required to issue financial statements that incorporate CECL for reporting periods after December 15, 2019. Table 1 lists the effective dates for CECL implementation.

|

Type of Firm |

U.S. GAAP Effective Datesa |

Effective Dates for Regulatory Filing |

|

Early Application |

Fiscal years beginning after 12/15/2018, including interim periods within those fiscal years |

Permitted after 12/15/2018 |

|

Public business entities that are SEC filersb |

Fiscal years beginning after 12/15/2019, including interim periods |

3/31/2020 |

|

Other public entities (non-SEC filers)c |

Fiscal years beginning after 12/15/2020, including interim periods |

3/31/2021 |

|

Nonpublic entitiesd |

Fiscal years beginning after 12/15/2021, and interim periods for fiscal years beginning after 12/15/2021 |

For reporting periods that begin after 12/15/2021 |

Source: FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 5, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528; OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standards on Financial Instruments-Credit Losses, September 6, 2017, p. 6, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2017/bulletin-2017-34.html; and FASB, Codification Improvement To Topic 326, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses, August 20, 2018, at https://www.fasb.org/cs/Satellite?c=Document_C&cid=1176171080296&pagename=FASB%2FDocument_C%2FDocumentPage.

a. U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, U.S. GAAP.

b. Most companies, but not all, that offer securities in the United States must register the securities offerings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). SEC, Registration Under the Securities Act of 1933, Fast Answers, 2011, at https://www.sec.gov/fast-answers/answersregis33htm.html.

c. Not all securities offerings are required to be registered with the SEC. The SEC makes exceptions for private offerings to a limited number of persons or institutions, offerings of limited size, intrastate offerings, and securities of municipal, state, and federal governments. SEC Registration Under the Securities Act of 1933, Fast Answers, 2011, at https://www.sec.gov/fast-answers/answersregis33htm.html.

d. FASB has proposed a new rule for nonpublic entities that delays CECL implementation by one year as compared to the initial rules. Dates reflected in the table for nonpublic entities are based on propped rules.

The regulators are not only proposing new rules; they have previously issued both a joint statement in support of CECL29 and a "Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses."30

Policy Issues

This section discusses, specific policy issues related to the CECL implementation and how it affects the banking industry; how CECL compares with IFRS 9 (the international version of CECL); and the potential effects of CECL on government entities.

Banking Industry

In support of CECL, former Comptroller of the Currency, Thomas J. Curry, stated the current credit loss model (incurred loss model) used to make loss provisions for assets forces firms to make large loss provisions in the midst of a credit downturn when the earnings and lending capacity are already stressed. He also noted the current accounting standards preclude banks from recording the anticipated losses until incurred.31 A FASB board member also raised similar concerns stating that the loans in the U.S. commercial banking system increased by 85% in the seven years leading up to the financial crisis whereas the reserves to cover the losses increased by 21%.32

Since FASB's announcement of CECL, banking industry professionals have raised concerns about implementing CECL, including during congressional testimonies. One such congressional witness testified that CECL creates a "redundant regulatory environment," especially when risk-based capital requirements were designed to address similar concerns.33 Risk-based capital establishes minimum regulatory capital based on a bank's activity. Another witness stated that implementing CECL would be costly, and it will make credit loss calculations more complicated and potentially reduce the amount of credit available to borrowers.34 Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency,35 Melvin L. Watt, stated that regulatory changes such as CECL will have an initial and ongoing impact on reported net income.36 Others have described the change in how credit losses are determined by adopting CECL "as the biggest bank accounting change in 40 years."37

FASB officials acknowledged concerns similar to the ones raised during congressional testimonies. One such acknowledged concern is that to comply with CECL, it "may require significant effort for many entities to gather the necessary data for estimating expected credit losses."38 FASB also acknowledged concerns surrounding limited credit availability, especially to less creditworthy borrowers or during an economically stressed environment. In response to these various concerns, FASB stated that CECL does not make a change to the economics of lending, but rather to the timing of when the losses are recorded.39 Despite FASB's acknowledgments, changing the timing of when losses are recorded does require developing new credit loss models to address the new standard and can lead to increased costs for banks and affect capital requirements. Under CECL, banks are required to take into consideration many unknowns that, in the case of some residential mortgages, may extend 30 years.

Effects on Banks

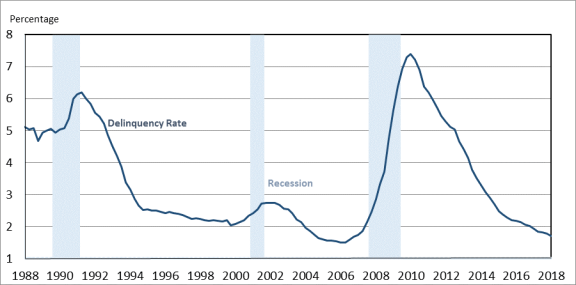

A CECL model is supposed to take into consideration future economic conditions in determining potential losses on financial assets. For example, for a 30-year loan originated in 1988 it would be difficult to predict the appropriate amount to reserve for potential credit loss, as well as the timing and duration of each of the three recessions identified by the shaded bars in Figure 1. Increases in the delinquency rate40 also varied during each of the three recessions. Similarly, the post-recession economic recovery would have been difficult to predict.

Figure 1 illustrates the delinquency rates on all loans made by commercial banks in the United States from January 1988 to December 2017. The incurred loss methodology did not consider the substantial decreases in delinquency rates from more than 6% in early 1991 to less than 3% in early 1994 and the increase again in delinquency rates of more than 7% in late 2009 and subsequent decline.41 Although 30-year projections of credit losses might not be precise, banks can adjust the credit loss models periodically to capture credit deteriorations and recovery. Adjustments to credit losses that consider long-term and short-term trends might prevent banks from increasing credit loss reserves during economic downturns or limiting credit availability to borrowers.

|

Figure 1. Delinquency Rate on All Loans, All Commercial Banks, |

|

|

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), Delinquency Rate on All Loans, All Commercial Banks [DRALACBN], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DRALACBN, June 15, 2018. Notes: Delinquent loans and leases are those past due 30 days or more and still accruing interest as well as those in nonaccrual status. Loans in nonaccrual status are those, generally, no longer receiving payments and banks have chosen not to continue accruing interest. All commercial banks. Quarterly, End of Period, from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 2017. |

One the one hand, because CECL incorporates forward-looking information, it is possible that during economic downturns, banks might limit credit availability, especially if they have forecast a prolonged downturn and thus must maintain sufficient capital levels. Although the profit or repayment of principal on a loan is recognized over the life of a loan, CECL requires recognition of the possible loss on a loan at its inception, which could result in lower earnings than under incurred loss methodology (ALLL) at loan inception because it could lead to some lenders to increase their reserves. An increase in reserves is an expense that reduces the profitability of the bank. Reduced profitability for banks or limited credit availability could negatively affect businesses and consumers alike. On the other hand, setting aside sufficient credit loss reserves may enhance a bank's ability to absorb future loan losses and thus continue to lend at a higher rate than if it had not done so. If CECL better matches actual credit losses, then banks might be less likely to become distressed and ultimately fail.

|

Historical Perspective on Credit Loss Reserves The debate on how much credit loss reserves banks should record on their financial statements has been ongoing at least for two decades. Whereas the SEC has focused on transparent financial statements that accurately report the assets, liabilities, and the periodic earnings of banks, the prudential banking regulators have maintained a prospective view that banks should have sufficient credit loss reserves to absorb losses during economic downturns, see Table 1. Nearly two decades ago, the banking regulators stated that the "loan loss reserve estimates are highly judgmental and imprecise, thus should be estimated in a conservative manner."42 The SEC was concerned that banks could potentially manage their earnings by increasing their credit loss reserves during normal economic times and build a cushion so they would not suffer as much during economic downturns.43 For publicly traded banks, earnings management could potentially reduce any negative effects on stock prices, and potentially incentivize management to manipulate stock prices. The prospective approach under CECL takes into consideration the potential losses over the life of a loan. CECL, arguably, aligns with banking regulators perspective that banks should have sufficient credit reserves to absorb losses through economic cycles. |

As a consequence of CECL's changes, the banking regulators are proposing to replace ALLL with a newly defined term in the capital rules—allowance for credit losses (ACL).44 If the proposed rules are adopted, ACL would be eligible for inclusion in a bank's tier 2 capital; subject to the current limits that include ALLL in tier 2 capital.45 Banks are required to maintain a certain level of capital (identified as tier 1, tier 2, and tier 3) based on the riskiness of the assets a bank holds.

ALLL includes asset valuation allowances that have been established through a charge against earnings to cover estimated credit losses on loans or other extensions of credit. Credit loss allowances under CECL cover a broader range of financial assets than ALLL. However, not every loss in the value of an asset would be included in the definition of ACL.46

Implementation Challenges

This section discusses some of the challenges and risks banks can expect to face to implement, including post-implementation challenges—costs, data retention, and training.

Implementation Costs

Banks will incur onetime transition costs and ongoing costs to develop and implement the new standard.47 Regulators are encouraging banks to capture and maintain relevant historical data to model CECL, but they are not requiring banks to obtain or reconstruct data from previous periods at unreasonable costs.48 The additional data retention requirements may increase ongoing operating expenses for banks. It is, generally, not cost effective for smaller banks to periodically purchase hardware and software to stay current with emerging technology and changing regulatory requirements. Instead, to lower costs, smaller banks typically use a third-party vendor that provides service to multiple banks for a monthly or annual fee. To facilitate the data retention requirements, banks and third-party service providers might incur a onetime upgrade costs to purchase additional hardware and software.

Some of the implementation costs might be offset as CECL uses a single impairment measurement objective as compared with U.S. GAAP, which requires multiple credit impairment models for different asset types.

Data Retention

To determine credit losses, banks rely on qualitative and quantitative factors, including historical data. Under CECL, banks might need to capture additional data and retain that data longer than they might have in the past to determine loss reserves. To facilitate the additional data requirements, some banks might need to migrate to a newer system. Migrating to a new system could result in possible loss of some historical data due to system incompatibilities.49

Despite using third-party vendors for other data processing services, some smaller banks, currently, rely on legacy systems or even spreadsheets for determining credit losses. Banks that use spreadsheets or other internal models to determine credit losses might need to migrate to third-party vendor systems for CECL. To facilitate the additional data retention requirements, third-party vendors might also need to upgrade their systems.

If smaller banks migrate from their own internal models to a vendor-based CECL model, similar CECL models across multiple banks could potentially either overestimate or underestimate the amount of credit loss reserves in aggregate, which could create systemic risks among smaller banks. Also, additional data retention requirements could increase cybersecurity risks for banks and third-party service providers.50

Training

In addition to any technology upgrades, there might be additional training costs for stakeholders to implement CECL.51 All stakeholders including bank employees, financial regulator employees (bank examiners), public auditors, and vendors, must develop sufficient knowledge and train their workforce to transition from incurred loss methodology to CECL. To reflect the changes from ALLL to ACL, the regulators also plan to propose changes to the regulatory reporting forms and instructions, which will likely require additional training.52

Increased Capital Costs for Banks

Banks are to record a onetime adjustment to credit loss allowance when CECL is implemented to reflect the difference between the current incurred loss method and the amount of credit loss allowance required under CECL, with exceptions for certain types of assets.53 The onetime adjustment is to be recorded at the beginning of the year that CECL is implemented.

Upon initial adoption, the recognition of lifetime credit losses for existing loans will likely reduce the income earned during the reporting period. An increase in credit loss reserves is an expense that reduces a bank's profitability. If a bank does not earn sufficient income to offset the increased credit loss reserves, then retained earnings will be declined. Retained earnings are part of bank's required Tier 1 capital.54 The primary function of bank capital is to act as a cushion to absorb unanticipated losses and declines in asset values that could otherwise cause a bank to fail. If retained earnings are affected, then banks might need to reduce their planned capital distributions if the decline caused their capital levels to be too close to the minimum requirements. Furthermore, because CECL is principles-based, neither FASB nor the financial regulators have prescribed a specific credit loss model; therefore, the effect on each bank will vary.

According to one estimate, the transition to CECL will likely result in an upfront increase in ACL of between $50 billion and $100 billion. The increased reserves are expected to affect common equity ratios across the banking system by 25-50 basis points (.25%-.50%).55 The expected cost for loss reserves over the life of loans is not expected to change. As these projected adjustments are in aggregate across the banking industry, some banks might need to increase their reserves significantly more than the projected 25-50 basis points whereas others might need to adjust less. Some banks have begun to disclose the preliminary impact of implementing CECL. In one instance, the bank indicated it would need to increase its credit reserves by 10% to 20% based on 2017 preliminary analysis.56

Because CECL requires banks to consider current and future expected economic conditions to estimate credit losses, some banking organizations have expressed concerns about the difficulty in planning CECL's adoption due to uncertainty about the future economic conditions when CECL is adopted.57 Unexpected economic conditions could result in a higher than anticipated increase in credit loss recognition. In response to this uncertainty, the banking regulators are proposing to allow banks the option to phase in over a three-year period any adverse effects the adjustments would have on regulatory capital requirements. Banks that elect to phase in the regulatory capital requirements over three years would be required to disclose their three-year election. A bank cannot retrospectively elect the three-year phase-in option.

The Regulatory Flexibility Act requires the regulators to consider the impact of proposed rules on small commercial banks and savings institutions with total assets of $550 million or less and trust companies with total revenues of $38.5 million or less.58 The regulators follow an established criterion on whether a new proposed rule would have a significant effect on these small banks. They estimated the proposed CECL rule would not generate any significant costs for the small banks.59

Stress Tests for Banks

The Federal Reserve conducts annual stress tests of the largest U.S. bank holding companies and U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations. Stress tests are qualitative and quantitative assessments of banks' capital plans to determine whether a bank will pass or fail.60 Simply put, a stress test is an analysis of banks viability during a financial crisis. The Federal Reserve requires banks to have sufficient capital to withstand a severe adverse operating environment. Even under such conditions, banks are expected to continue lending, maintain normal operations and ready access to funding, and meet obligations to creditors and counterparties.61

For the 2018 and 2019 stress test cycles, the regulators propose that banking organizations continue to use ALLL as calculated under the incurred loss methodology. Using ALLL instead of ACL is expected to promote the comparability of stress tests results across banks even if banks adopt CECL in 2019.62 In 2021, not only will all banking organizations be required to adopt CECL, but also stress tests are to use ACL. Banks that adopt CECL before the 2021 reporting period will be required to calculate credit losses based on the incurred loss methodology and CECL, potentially increasing these banks' operational costs in the short run. Differences in the way that U.S. GAAP and international accounting standards treat credit loss estimates and credit loss reserves could potentially disadvantage U.S. banks. Some in the banking industry have suggested capital requirements and stress tests can be modified to alleviate some of these concerns.63

A future recession or banking crisis will likely determine any positive or negative effect of changing to CECL. Any future refinements to CECL are likely to depend on whether CECL helped determine the appropriate amount of credit loss reserves even during worsening economic conditions. FASB periodically updates the accounting standards in response to the capital markets.

Comparison of U.S. CECL and IFRS 9

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) promulgates International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) that countries can adopt or modify to suit their needs.64 However, the United States has chosen to remain with U.S. GAAP. FASB created CECL and issued an Accounting Standards Update 326 (ASU 326) for financial instruments—credit losses. IASB independently issued IFRS 9, the international version of CECL.

FASB and IASB jointly established a Financial Crisis Advisory Group to advise each respective board about the global regulatory environment after the financial crisis.65 They also jointly deliberated revisions to credit loss models through 2012. Initially, the boards intended to create a converged credit loss model, but based on separate stakeholder feedback, FASB and IASB created different credit loss models.66

Foreign banking organizations (FBOs) that operate in the United States will need to estimate credit losses under IFRS and U.S. GAAP. In addition to FBOs issuing their annual reports and domestic regulatory reports based on IFRS for their U.S. operations, they are required to prepare quarterly financial statements and regulatory reports based on U.S. GAAP.67 The multiple filing requirements mandate that FBOs create different credit loss estimates. Lastly, some experts in the financial industry believe that under similar circumstances, IASB's credit loss model is operationally more complex and might result in lower reserves than FASB's CECL model.68

IASB stakeholders showed a preference for a loss impairment model that uses a dual measurement approach. U.S. stakeholders showed a strong preference for more of a holistic lifetime credit loss measurement that, unlike IFRS 9, is dependent on credit deterioration factors. FASB concluded that convergence was unachievable between the two accounting standards for some key reasons69

- Even before the new models were developed, the existing practice of accounting for credit losses was different between U.S. GAAP and IFRS preparers.

- The interaction between the roles of the prudential regulators in determining loss allowances is historically stronger in the United States.

- The users of financial statement prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP places greater weight on the loss allowances reported on the balance sheet than the IFRS counterparts.

As a consequence of the issues discussed above as to why the two regime's credit loss models could not be converged, certain similarities and differences between the CECL model and IFRS 9 became clear. Some selected ones are discussed below70

- Both the CECL model and IFRS 9 are expected credit loss models. CECL requires that the full amount of the expected credit losses be recorded for all financial assets at amortized cost. IFRS 9 requires recognition of credit losses for a 12-month period. If there is a significant increase in credit risk, then lifetime expected credit losses are recognized.

- The amount of expected credit losses for assets with significantly increased credit risk might be similar under CECL and IFRS 9, because they both require credit losses over the life of the loan.

- FASB considers the time value of money to be implicit in CECL methodologies, whereas IFRS 9 requires explicit consideration of the time value of money.

- When similar characteristics exist among assets, CECL model requires the collective evaluation of credit losses. IFRS 9 allows collective evaluation of credit losses based on shared-risk characteristics, but IFRS 9 does not require a collective evaluation of credit losses. It requires that only the probability-weighted outcomes are given consideration.

IFRS 9 has been effective for annual periods beginning on or after January 1, 2018, with earlier implementation allowed.

Potential Effects on Governmental Entities

The housing finance system has two major components, a primary market and a secondary market. Lenders make new loans in the primary market, and banks and other financial institutions buy and sell loans in the secondary market. The government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home loan Mortgage Association) play an active role in the secondary market. Both entities are in conservatorship, with the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) acting as the conservator.71 Both entities are still publicly listed and subject to GAAP as promulgated by FASB. Similar to banks, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are required to implement CECL. As a consequence of implementing CECL, their earnings and asset valuations are likely to be affected.

By one estimate, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may each need an additional $7.5 billion and $5 billion credit loss reserves, respectively.72 Currently, they each have $3 billion in capital reserves. To facilitate the additional reserves both entities might need to borrow from the U.S. Treasury. Similar to certain banks being allowed to phase in the increased credit reserves over three years, Congress and FHFA can choose to allow Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to accumulate the additional reserves over three years, potentially avoiding additional draws from the Treasury.

Currently, federal government entities that lend or provide loan guarantees are not subject to CECL. The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) promulgates the accounting standards for federal government agencies. If FASAB adopts CECL, the credit loss reserves on certain assets held by the federal government, including outstanding loans of $1.3 trillion and loan guarantees of $3.9 trillion, could potentially increase.73

Currently, state and local governments that lend or provide loan guarantees are not subject to CECL. The Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) promulgates the accounting standards for state and local governments. If GASB adopts CECL, the credit loss reserves on certain assets held by state and local governments could potentially increase. Each state and local government can choose to follow accounting standards promulgated by GASB. Some states have enacted laws that require the state and the local government to follow accounting standards issued by GASB.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Darryl Getter, [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and Jeff Stupak provided helpful comments. [author name scrubbed], Jared Nagel, and [author name scrubbed] provided valuable assistance with research.

Footnotes

| 1. |

CRS Report R43413, Costs of Government Interventions in Response to the Financial Crisis: A Retrospective, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

For additional information about FASB, see CRS Report R44894, Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 254, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 4. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 254, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 5. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326): Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 1, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 6. |

Accounting Research Manager, 2017-2018 GAAP Financial Statement Disclosures Manual; Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 450, at http://www.accountingresearchmanager.com/#/combined/01230711A65C8BAC652576C0002E10A4/accounting/arm/interpretations-and-examples/24-financial-statements-form-content-and-other-matters/2017-2018-gaap-financial-statement-disclosures-manual/part-4-liabilities/asc-topic-450-contingencies? |

| 7. |

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Economic Review, Bank Loan-Loss Accounting: A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Evidence, 2000. |

| 8. |

Change to CECL is identified as Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-13. FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 5, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 9. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 1, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 10. |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, National Credit Union Administration, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, respectively) Joint Statement on the New Accounting Standards on Financial Instruments - Credit Losses, June 17, 2016, pp. 1-2, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20160617b.htm. |

| 11. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, p. 15, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 12. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 248, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 13. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, pp. 275-278, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 14. |

15 U.S.C. §77s. |

| 15. |

FASB, "Facts About FASB," http://www.fasb.org/facts/. |

| 16. |

For more information about the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), see CRS In Focus IF10032, Introduction to Financial Services: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 17. |

Insurance companies that are publicly traded will need to implement CECL based on FASB's implementation timeline. Unless required by the state regulators, nonpublicly traded insurance companies will not need to comply with CECL. |

| 18. |

For more information on filing requirements, see CRS Report R45221, Capital Markets, Securities Offerings, and Related Policy Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 19. |

Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home loan Mortgage Association (Freddie Mac) are in conservatorship. Similar to banks, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are subject to CECL implementation requirements. The effects of CECL on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are discussed in detail later in the report. |

| 20. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, "Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations," 83 Federal Register 22312-22339, May 14, 2018. |

| 21. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, press release, September 12, 2017, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/topics/faq-new-accounting-standards-on-financial-instruments-credit-losses.htm. |

| 22. |

FDIC, Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses - Revised Policy Statement and Frequently Asked Questions, December 13, 2006, at https://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2006/fil06105.html. |

| 23. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, October 24, 2017, p. 15, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/cecl-faqs.html. |

| 24. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments—Credit Losses, Question 18, September 6, 2017, p. 16, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/topics/faq-new-accounting-standards-on-financial-instruments-credit-losses.htm. |

| 25. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, October 24, 2017, p. 19, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/cecl-faqs.html. |

| 26. |

For more detailed information about balance sheet and income statement, see CRS Report R44894, Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 27. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 244, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 28. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, pp. 247-256, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 29. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Joint Statement on the New Accounting Standards on Financial Instruments - Credit Losses, June 17, 2016, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20160617b.htm. |

| 30. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, October 24, 2017, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/cecl-faqs.html. |

| 31. |

OCC, Remarks by Thomas J. Curry Comptroller of the Currency Before the AICPA Banking Conference, September 16, 2013, at https://occ.gov/news-issuances/speeches/2013/index-2013-speeches.html. |

| 32. |

Hal Schroeder, For the Investor: Benefits of the "CECL" Model and "Vintage" Disclosures, FASB, 2015, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/SectionPage&cid=1176165963082. |

| 33. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, More Efficient Federal Financial Regulatory Regime, Testimony by Brian Ducharme (president, MIT Federal Credit Union) 115th Cong., 1st sess., December 8, 2017. |

| 34. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Fostering Community Economic Growth, Testimony by Dallas Bergl (CEO, Inova Federal Credit Union), 115th Cong., 1st sess., June 8, 2017. |

| 35. |

The change to CECL will also affect Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Association (Freddie Mac) assets valuations and earnings. Both entities are in conservatorship with the Federal Housing Finance Agency acting as the conservator. |

| 36. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Sustainable Housing Finance, 115th Cong., 1st sess., October 3, 2017. |

| 37. |

Steven Abrahams, BankThink CECL Will Inflate Credit Booms and Worsen Downturns, American Banker, September 9, 2016, at https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/cecl-will-inflate-credit-booms-and-worsen-downturns. |

| 38. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 243, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 39. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 244, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 40. |

Banks incur loss on delinquent loans (i.e., loans that are in payment default). |

| 41. |

The ratio of loan loss reserves prior to the financial crisis was low as 1.16% in 2006 and was more than 3.70% near the end of the crisis in early 2010. As of March 31, 2018, the ratio of loan loss reserves to loans is near the pre-crisis level at 1.23%, see Figure 1. The figures discussed were from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Delinquency Rate on All Loan, All Commercial Banks, at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DRALACBN. |

| 42. |

Laurence H. Meyer, Testimony of Governor Laurence H. Meyer, Loan-Loss Reserves, Attachment to the Testimony, The Federal Reserve Board, Before the Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, Committee on Banking and Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, June 16, 1999, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/testimony/1999/19990616.htm. |

| 43. |

Larry D. Wall and Timothy W. Koch, Bank Loan-Loss Accounting: A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Evidence, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, June 2000, at https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/publications/economic-review/2000/q2/vol85no2_bank-loan-loss-accounting.aspx. |

| 44. |

"The financial regulators are not proposing a change to the limit of 1.25% of risk-weighted assets governing the amount of ACL eligible for inclusion in tier 2 capital." Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, p. 19, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 45. |

Replacing allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL) with allowance for credit losses (ACL) is not an acronym that FASB proposed when they created CECL. The financial regulators are proposing to replace ALLL with ACL because ACL encompasses credit losses on a wider array of assets. Federal Reserve, FDIC and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, pp. 14-17, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 46. |

For example, debt security that is available for sale (as compared with debt security held until maturity) would be reported based on the market value as of the closing date of the reporting period. In such instances, an allowance would not be required. Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, pp. 17-20, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 47. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 48. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, October 24, 2017, pp. 15, 20, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/cecl-faqs.html. |

| 49. |

General Service Administration, Data Center Optimization Initiative (DCOI) Guide for Data Center Migration, Consolidation, and Closure, August 29, 2017, at https://www.gsa.gov/blog/2017/11/03/How-to-Successfully-Migrate-Consolidate-and-Close-Data-Centers. |

| 50. |

For more information about cybersecurity issues, see CRS In Focus IF10559, Cybersecurity: An Introduction, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 51. |

For more information on cost-benefit analysis in federal rulemaking, see, CRS Report R44813, Cost-Benefit Analysis and Financial Regulator Rulemaking, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 52. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 53. |

OCC, Federal Reserve, and FDIC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, 83 Federal Register 22312-22339, May 14, 2018. |

| 54. |

Among other items, Tier 1 capital includes qualifying common stock, surplus, and retained earnings. Federal Reserve, FDIC, NCUA, and OCC, Frequently Asked Questions on the New Accounting Standard on Financial Instruments – Credit Losses, October 24, 2017, p. 16, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/accounting/cecl-faqs.html. |

| 55. |

Christopher Wolfe, Michael Shepherd, and Cynthia Chan, Fitch: New Credit-Loss Rules Manageable for US Banks, FitchRatings, July 20, 2016, at https://www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/1009172. |

| 56. |

Citigroup Inc., Form 10-K, Annual Report as of December 31, 2017, February 23, 2018, p. 124, at https://www.citigroup.com/citi/investor/annual-reports.html. |

| 57. |

"The financial regulators are not proposing a change to the limit of 1.25% of risk-weighted assets governing the amount of ACL eligible for inclusion in tier 2 capital." OCC, Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations, April 17, 2018, p. 20, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2018/nr-ia-2018-39.html. |

| 58. |

5 U.S.C. §601 et seq. |

| 59. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, "Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations," 83 Federal Register 22322-23324, May 14, 2018. |

| 60. |

For additional information about stress tests, see CRS Report R45036, Bank Systemic Risk Regulation: The $50 Billion Threshold in the Dodd-Frank Act, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 61. |

Federal Reserve, Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review 2018 Summary Instructions, February 2018, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20180201a.htm. |

| 62. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, "Regulatory Capital Rules: Implementation and Transition of the Current Expected Credit Losses Methodology for Allowances and Related Adjustments to the Regulatory Capital Rules and Conforming Amendments to Other Regulations," 83 Federal Register 22322-23324, May 14, 2018. |

| 63. |

Gregory Norwood, Capital and the Allowance for Credit Losses, Deloitte, US Current Expected Credit Losses Implementation Insights, 2018, at https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/financial-services/articles/us-current-expected-credit-losses-cecl.html. |

| 64. |

After having explored the possibility of converging IFRS and U.S. GAAP for the new credit loss model, the accounting standards boards identified enough differences and chose not to converge the credit loss model standards. At other times, the boards do jointly work on certain standards. For more detailed information about U.S. GAAP, IFRS, and IASB, see CRS Report R44894, Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 65. |

FASB, Financial Crisis Advisory Group (FCAG), at https://www.fasb.org/fcag/index.shtml. |

| 66. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 282, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 67. |

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Reporting Forms - FFIEC 002, Report of Assets and Liabilities of U.S. Branches and Agencies of Foreign Banks, June 2018, at https://www.ffiec.gov/forms002.htm. |

| 68. |

Christopher Wolfe, Michael Shepherd, and Cynthia Chan, Fitch: New Credit-Loss Rules Manageable for US Banks, Fitch Ratings, July 20, 2016, at https://www.fitchratings.com/site/pr/1009172. |

| 69. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, p. 282, http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 70. |

FASB, Financial Instruments—Credit Losses (Topic 326), Measurement of Credit Losses on Financial Instruments, June 2016, pp. 282-284, at http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Document_C/DocumentPage&cid=1176168232528. |

| 71. |

For more information about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, see CRS Report R42995, An Overview of the Housing Finance System in the United States, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 72. |

Brad Finkelstein, Why Fannie and Freddie may need Treasury Bailout Cash, American Banker, July 12, 2018, at https://www.americanbanker.com/news/why-fannie-mae-and-freddie-mac-may-need-more-bailout-cash-from-treasury-department? |

| 73. |

Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives, Fiscal Year 2019, February 2018, p. 258, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/. |