Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International

Accounting and auditing standards in the United States are promulgated and regulated by various federal, state, and self-regulatory organizations (SROs). Accounting and auditing standards are also influenced by practitioners from businesses, nonprofits, and government entities. Congress has allowed financial accounting and auditing practitioners to remain largely self-regulated while retaining oversight responsibility. At certain times, Congress has sought to achieve specific accounting- and auditing-based policy objectives by enacting legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX; P.L. 107-204) and the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA; P.L. 101-508).

The informational needs of stakeholders differ between the different sectors of the economy—the private sector, the federal government, and state and local governments. As a consequence, different accounting and auditing standards have evolved in these sectors. In the private sector, financial statements communicate to stakeholders how the company used its resources to generate profit and expand its business, or how the company incurred loss and the chances the business will survive over the long run. In comparison, public-sector entities such as the federal, state, and local governments issue reports to communicate how tax revenues were used to benefit citizens. State and local governments have standards distinct from those of the federal government. As such, accounting and auditing standards can be classified into three areas: (1) private industry standards, (2) federal government standards, and (3) state and local government standards.

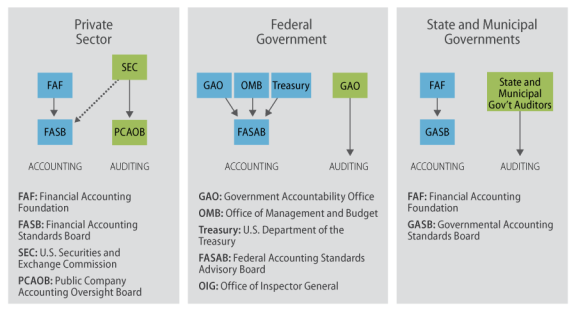

The accounting and auditing standards created for publicly traded companies are subject to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) oversight. Congress has oversight over the SEC and annually appropriates its funding. Throughout its history, the SEC has relied on SROs to establish financial reporting standards for the private sector; these are known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Currently, the SEC recognizes the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) as the designated authority for establishing GAAP. SOX created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to oversee the auditing profession for the private sector. The SEC has oversight responsibility over FASB and PCAOB.

The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) was created to establish the financial reporting and accounting standards for the federal government. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has responsibility for establishing auditing standards for federal government agencies, including federal grant recipients in state and local governments.

A counterpart to FASAB for state and local governments is the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB). Many of the underlying principles between FASAB and GASB are the same, but each state or territory is allowed to choose whether it follows GASB standards in full or modifies the standards to fit local needs. Auditing standards vary by state and local governments.

Two policy issues might be of particular interest to Congress and investors. The first is the relationship between accounting and auditing standards in the United States and in other countries. In particular, there is debate over whether or to what degree international accounting and auditing standards should influence U.S. GAAP and U.S. Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (U.S. GAAS), respectively.

The second is to what degree business risk should be evaluated based on sustainability issues. Increasingly, investors expect firms to respond to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) has created a series of provisional standards for the private sector. SASB is an independent organization that is not recognized by Congress or the SEC as an official standard-setting body.

Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure: U.S. and International

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Private Sector

- Accounting

- Annual Report to the SEC: Form 10-K

- Annual Report to Shareholders

- Auditing

- Audit Opinions

- COSO Framework

- Federal Government

- Accounting

- Auditing

- State and Local Governments

- Accounting

- Auditing

- Policy Issues

- International Standards

- Accounting

- Auditing

- The Road Ahead for U.S. Accounting and Auditing Standards and International Standards

- Sustainability Accounting Standards

- Corporations and SASB Disclosure

- Sustainability Accounting Standards Board

- The Road Ahead for Sustainability Accounting Standards

Figures

- Figure 1. Accounting and Auditing Standard-Setters

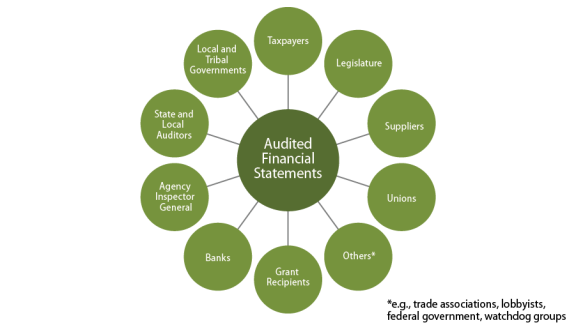

- Figure 2. Stakeholders in the Private Sector

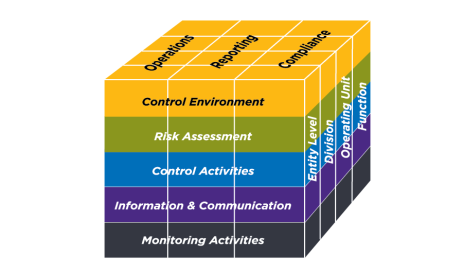

- Figure 3. COSO Framework

- Figure 4. Stakeholders in the Federal Government

- Figure 5. Stakeholders in the State or Local Governments

- Figure 6. International and Sustainability Standard-Setters

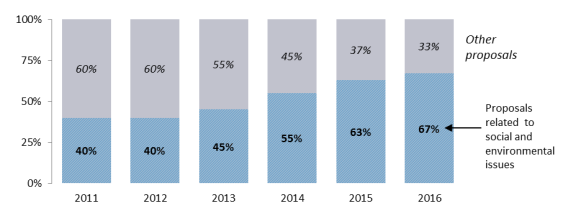

- Figure 7. Shareholder Proposals Pertaining to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Issues

- Figure 8. Universe of Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues

- Figure 9. Disclosure of SASB Topics on Form 10-K

Tables

Summary

Accounting and auditing standards in the United States are promulgated and regulated by various federal, state, and self-regulatory organizations (SROs). Accounting and auditing standards are also influenced by practitioners from businesses, nonprofits, and government entities. Congress has allowed financial accounting and auditing practitioners to remain largely self-regulated while retaining oversight responsibility. At certain times, Congress has sought to achieve specific accounting- and auditing-based policy objectives by enacting legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX; P.L. 107-204) and the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA; P.L. 101-508).

The informational needs of stakeholders differ between the different sectors of the economy—the private sector, the federal government, and state and local governments. As a consequence, different accounting and auditing standards have evolved in these sectors. In the private sector, financial statements communicate to stakeholders how the company used its resources to generate profit and expand its business, or how the company incurred loss and the chances the business will survive over the long run. In comparison, public-sector entities such as the federal, state, and local governments issue reports to communicate how tax revenues were used to benefit citizens. State and local governments have standards distinct from those of the federal government. As such, accounting and auditing standards can be classified into three areas: (1) private industry standards, (2) federal government standards, and (3) state and local government standards.

The accounting and auditing standards created for publicly traded companies are subject to the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC's) oversight. Congress has oversight over the SEC and annually appropriates its funding. Throughout its history, the SEC has relied on SROs to establish financial reporting standards for the private sector; these are known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Currently, the SEC recognizes the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) as the designated authority for establishing GAAP. SOX created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to oversee the auditing profession for the private sector. The SEC has oversight responsibility over FASB and PCAOB.

The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) was created to establish the financial reporting and accounting standards for the federal government. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has responsibility for establishing auditing standards for federal government agencies, including federal grant recipients in state and local governments.

A counterpart to FASAB for state and local governments is the Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB). Many of the underlying principles between FASAB and GASB are the same, but each state or territory is allowed to choose whether it follows GASB standards in full or modifies the standards to fit local needs. Auditing standards vary by state and local governments.

Two policy issues might be of particular interest to Congress and investors. The first is the relationship between accounting and auditing standards in the United States and in other countries. In particular, there is debate over whether or to what degree international accounting and auditing standards should influence U.S. GAAP and U.S. Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (U.S. GAAS), respectively.

The second is to what degree business risk should be evaluated based on sustainability issues. Increasingly, investors expect firms to respond to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) has created a series of provisional standards for the private sector. SASB is an independent organization that is not recognized by Congress or the SEC as an official standard-setting body.

Introduction

Accounting is commonly considered the language of finance. A common set of principles and rules help establish accounting standards. Accountants who audit financial statements (auditors1) also adhere to a common set of audit principles and rules to examine financial statements.

In the United States, accounting and auditing standards are promulgated and regulated by various federal, state, and self-regulatory agencies. Accounting and auditing standards are also influenced by practitioners from businesses, nonprofits, and government entities (federal, state, and local). Congress has allowed financial accounting and auditing practitioners to remain self-regulated while retaining oversight responsibility. At certain times, Congress has sought to achieve specific accounting- and auditing-based policy objectives by enacting legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX)2 and the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA).3

This report examines the U.S. accounting and auditing regulatory structure. It first provides background on why different accounting standards exist between the private and public sectors. The next three sections of the report discuss how accounting and auditing standards are created and regulated in the private sector, the federal government, and state and local governments. Some of the common concepts that affect accounting and auditing standards across all sectors are discussed in detail in the private-sector segment of the report. Then, the report discusses the relationship between (1) international accounting and auditing standards and (2) the United States Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP) and Generally Accepted Auditing Standards (U.S. GAAS). Next, the report discusses the newly emerging Sustainability Accounting Standards for the private sector. Lastly, this report has three appendixes. Appendix A provides a table of acronyms that are common to the accounting and auditing profession and used throughout this report. Appendix B provides a glossary that explains the various financial statements listed in Table 1. Appendix C provides the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants' (AICPA) Principles of Professional Conduct for Certified Public Accountants (CPAs).

Background

The informational needs of stakeholders differ between the private and public sectors. As a consequence, different accounting and auditing standards have evolved in these sectors to address stakeholders' specific needs. In the private sector, financial statements communicate to stakeholders such as investors, creditors, company employees, regulators, and others how the company used its resources to generate profit and expand its business, or how the company incurred loss and the likelihood the business will survive over the long run. Public-sector entities such as the federal, state, and local governments issue reports to communicate how tax revenues were used to benefit citizens. Their intended audience is usually taxpayers, Congress, or the state and local legislatures. State and local governments have standards distinct from those of the federal government. Thus, accounting and auditing standards can be classified into three areas: (1) private industry standards, (2) federal government standards, and (3) state and local government standards. Figure 1 provides an overview of the accounting and auditing standard-setters for the different segments that will be discussed in this report.

|

|

Source: CRS. Note: In the first panel, the striated line indicates the SEC's oversight role over accounting standards promulgated by the FASB. The FASB's parent organization, the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF), is a nonstock Delaware corporation. Neither FASB nor FAF is a government agency, even though the SEC does have oversight of the budget for FASB and the accounting standards as promulgated by FASB (FAF, "Facts About FAF," http://www.accountingfoundation.org/jsp/Foundation/Page/FAFSectionPage&cid=1176157790151). |

Private Sector

In the private sector, financial statements provide economy-wide benefits to firms and investors through the dissemination of accurate information. One way these benefits are realized is through the efficient allocation of capital between investors and firms.4 Investors rely on financial statements to make informed decisions on how best to invest their savings. Financial statements are a primary means by which firms communicate with capital markets, investors, creditors, regulators, the public, and others. Figure 2 illustrates the range of private-sector stakeholders.

|

|

Source: Adapted from PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), Understanding a Financial Statement Audit, January 2013, p. 3, http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/audit-assurance/publications/understanding-financial-audit.html. |

The private sector includes public and private companies5 as well as not-for-profit organizations, though this report focuses on public companies. The accounting and auditing standards created for publicly traded firms are subject to the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC's) oversight. Congress created the SEC in 1934 to protect investors and to maintain fair, orderly, and efficient markets. However, Congress has oversight over the SEC and annually appropriates its funding.6

Accountants and auditors, in addition to adhering to accounting and auditing standards, are also subject to the ethical requirements of their affiliated membership organizations, such as CPAs' Principles of Professional Conduct (see Appendix C).

Accounting

Accounting is a process by which an entity identifies, measures, and communicates financial information about its economic activities to stakeholders by adhering to a common set of practices, known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).7 The primary way for an entity to communicate its financial performance to its stakeholders is through financial statements. In simple terms, accounting standards are agreements among practitioners (i.e., accountants, auditors, and regulators) on how each line item on the financial statement should be valued and reported.8

One of the powers Congress gave the SEC is the statutory authority to establish accounting standards for the private sector in the United States. Since the creation of the SEC, domestic companies have used GAAP to issue financial statements.9 Throughout its history, the SEC has relied on the private sector to establish and develop GAAP in the United States.10 Currently, the SEC recognizes the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)11 as the designated organization for establishing GAAP for the private sector.12

|

FASB Funding Since enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX),13 FASB has been funded by fees collected from issuers of publicly traded securities. The fees are subject to SEC review.14 FASB incurred $40.5 million in program and support expenses in 2016. The expenses were paid in part with $24.8 million from accounting support fees;15 the remainder was paid through other revenue sources, such as the sale of publications or subsidies from the Financial Accounting Foundation's (FAF's) excess reserve funds. FASB is a subsidiary of FAF. According to FAF, the FAF, FASB, and Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB) are mainly funded through accounting support fees.16 |

Financial statements for publicly traded companies as well as privately held companies commonly include an income statement, a balance sheet, a statement of shareholder equity, and a statement of cash flows. Table 1 compares the different financial statements presented in annual reports of various entities in different sectors (for an explanation of different statements, see Table B-1). As previously discussed, as a consequence of the differences between the private sector and the public sector, the financial statements normally used in one sector might not exist in another sector. Further, financial statements within the same sector (e.g., the private sector) will communicate a qualitatively different set of information based on their underlying business activity. As an example, the financial statements for Boeing, mainly a manufacturer of commercial jetliners, defense, space, and security systems, will be qualitatively different from those of T-Mobile, a provider of cell phone service and retailer of cell phones.

|

Private Sectora |

Federal Governmentb |

State and Local Governmentsc |

|

Income Statement |

Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position |

Statement of Activities |

|

Balance Sheet |

Balance Sheet |

Statement of Net Position (Assets) |

|

Statement of Shareholders' Equity |

Statement of Operations and Changes in Net Position |

Statement of Net Position (Assets) |

|

Statement of Cash Flows |

Statement of Changes in Cash Balance from Unified Budget and Other Activities |

Statement of Activities |

|

Not Applicable |

Statement of Net Cost |

Required Supplementary Information |

|

Not Applicable |

Reconciliations of Net Operating Cost and Unified Budget Surplus (Deficit) |

Required Supplementary Information |

|

Not Applicable |

Statement of Social Insurance |

Required Supplementary Information |

|

Notes to the Financial Statements |

Notes to the Financial Statements |

Notes to the Financial Statements |

|

Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operationd |

Management's Discussion and Analysis |

Management's Discussion and Analysis |

|

Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operation |

Citizen's Guide to the Financial Report of the United States Government |

Letter of Transmittal |

|

Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operation |

Required Supplementary Information |

Required Supplementary Information |

|

Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operation |

Budget of the U.S. Governmente |

Statistical Section |

Source: CRS.

a. Several of the financial statements that exist in the government sector do not exist in the private sector or are not relevant.

b. The financial statements listed below are from the Financial Report of the United States Government for Fiscal Year 2015. The financial statements listed in Table 1 provide a comparison to the private sector. Individual agency financial reports may differ based on their function and purpose from what is listed for the federal government. See Department of the Treasury, Financial Report of the United States Government - Fiscal Year 2016, January 12, 2017, https://www.fiscal.treasury.gov/fsreports/rpt/finrep/fr/fr_index.htm.

c. The financial statements listed below are from the Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) of the State of Ohio and from the CAFR of the City of New York for FY2016. Other states' and territories' financial statements might differ due to their respective laws and requirements. Only government-wide financial statements are included, and specific fund financial statements, such as proprietary funds, fiduciary funds, and fiduciary component units, are not listed. See The State of Ohio, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report - The State of Ohio - Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2016, December 22, 2016, http://obm.ohio.gov/StateAccounting/financialreporting/cafr.aspx.

Other cities' and local municipalities' financial statements might differ due to their respective laws and requirements. Only government-wide financial statements are included, and fund financial statements are not listed. See The City of New York, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2016, October 31, 2016, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comprehensive-annual-financial-reports/.

d. Some elements of the various statements and schedules in the government sector might be similar in the management's discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operation in the private sector, but most elements are not relevant or are not presented.

e. For the purpose of this table, Budget of the U.S. Government includes all supporting schedules. See Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, February 9, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget.

Annual Report to the SEC: Form 10-K

Federal securities laws require public companies, both domestic and foreign, to share critical information about their performance on an ongoing basis. Domestic companies are required to submit annual reports on Form 10-K, quarterly reports on Form 10-Q, and current events on Form 8-K. Form 10-K provides a comprehensive overview of the company's performance, including audited financial statements, and is required to be filed 60-90 days after the fiscal year-end based on the size of the company. Form 10-Q is required to be filed 40-45 days after quarter end.17 Form 8-K18 is required to be filed within four business days to inform shareholders of material corporate events.19 Companies submit their forms (reports) electronically to SEC's Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval (EDGAR) system.

Foreign companies that participate in U.S. capital markets are required to file a different but comparable set of financial reports. Based on the expectation that the United States will eventually either adopt or converge with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS),20 the SEC in 2007 changed the requirement for Foreign Private Issuers (FPIs).21 Until 2007, foreign and domestic firms had similar filing requirements with the SEC. In 2007, to prevent foreign firms from potentially delisting from U.S. exchanges, the SEC authorized foreign firms to file either Form 20-F using IFRS or Form 10-K using U.S. GAAP. This ruling eased concerns that some foreign firms might delist from the U.S. exchanges due to additional costs they would incur either reconciling or converting from IFRS to U.S. GAAP. Further, SEC was still debating in 2007 as to whether the United States should converge with the IFRS or continue to follow U.S. GAAP.22

Annual Report to Shareholders

The annual report to shareholders is distinct from Form 10-K. The annual report to shareholders is considered a state-of-the-company report to its shareholders and potentially interested stakeholders. It usually contains a letter from the CEO, financial data, results of operations, market segment information, new product plans, subsidiary activities, and research and development on future programs. The SEC requires the annual report to be sent to shareholders. The SEC also requires listed companies to post their annual reports and proxy materials on the firm's website.23 Proxy materials provide the firm's shareholders with information on substantive issues related to the firm. It also provides an avenue for the shareholders to influence the decisions of the firm's board of directors and management, including the selection of the board of directors and compensation of company executives.24

The annual report filed with the SEC on Form 10-K might contain more detailed information about the company's financial condition than the annual report to shareholders. Companies may send their annual 10-K report to shareholders instead of creating a separate annual report. Registered FPIs are required to follow a similar set of requirements as domestic firms.

Auditing

Private- or public-sector stakeholders need to have reasonable assurance that the financial statements of an entity are free of material misstatement whether caused by error or fraud.25 In the private sector, independent assurance to shareholders and other stakeholders is provided by a qualified external party—an auditor. The auditor is engaged to give an unbiased professional opinion on whether the financial statements and related disclosures are fairly stated in all material26 respects for a given period of time in accordance with GAAP.27

As a consequence of financial accounting fraud in the early 2000s, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. SOX created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) as a nonprofit corporation to provide independent oversight of audits of public companies. The PCAOB also oversees the audits of brokers and dealers, including compliance reports.28

The five board members of the PCAOB are appointed to staggered five-year terms by the SEC, after consultation with the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Secretary of the Treasury. The SEC has oversight authority over the PCAOB, including the approval of the board's rules, standards, and budget. SOX was amended by the Dodd-Frank Act,29 which established funding for the PCAOB's activities, primarily through the annual accounting support fees assessed on public companies and other issuers, as well as brokers and dealers registered with the SEC.30 The PCAOB's budget for 2017 was $269 million. Approximately $233 million of the accounting support fees to be collected will be allocated to public companies and $35 million to brokers and dealers.31

Along with the creation of PCAOB, SOX (§404) also requires public companies' annual reports to include the company's own assessment of internal control32 over financial reporting and an auditor's attestation (audit). The different types of audit opinions an auditor may issue are discussed next, followed by a discussion of internal control integrated frameworks.

Audit Opinions

Auditors form audit opinions by examining the types of risks an organization might face and the types of controls that exist to mitigate those risks. Once the risks and controls to mitigate those risks have been determined, the auditors will examine the supporting evidence and determine if management is presenting the financial statements fairly in all material respects.33 Although most entities will usually receive an unqualified opinion, the auditor may express other types of opinions based on the circumstances. There are four different types of audit opinions an auditor may express:34

- 1. Unqualified Opinion. An unqualified opinion states that the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of the entity in conformity with GAAP. This is the opinion expressed in the standard report. Under certain circumstances explanatory language might be added to the auditor's standard report, while not affecting the auditor's unqualified opinion on the financial statements.

- 2. Qualified Opinion. A qualified opinion states that, except for the effects of the matter(s) to which the qualification relates, the financial statements present fairly in all material respects the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with GAAP.

- 3. Adverse Opinion. An adverse opinion states that the financial statements do not present fairly the financial position, results of operations, or cash flows of the entity in conformity with GAAP.

- 4. Disclaimer of Opinion. A disclaimer of opinion states that the auditor does not express an opinion on the financial statements.

Independent audit opinions do not fully guarantee the financial statements are presented fairly in all material respects for the following key reasons:

- The auditors use statistical methods for random sampling and look at only a fraction of the economic events or documents during an audit. It is cost-and time-prohibitive to recreate or sample all economic events at an entity.

- Frequently many line items on the financial statements involve subjective decisions or a degree of uncertainty as a result of using estimates.

- Audit procedures cannot eliminate potential fraud by management, though it is possible an auditor may find fraud committed by management during the audit process.

Thus, the auditor provides only a reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement.

COSO Framework

Section 404 of SOX requires management at public companies to select an internal control framework and then assess and report annually on the design and operating effectiveness of their internal controls. The internal control framework widely used by the business community is the one created by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO).35 COSO is a private-sector initiative dedicated to improving organizational performance and governance through effective internal control, enterprise risk management, and fraud deterrence.36

|

SEC Internal Control—Integrated Framework Requirements A requirement of SOX was for the SEC to create rules that would require public companies' annual reports to contain (1) a statement of management's responsibility for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures; and (2) management's assessment of the internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting. Under SEC's final rules, annual reports on internal control are required to contain

The COSO framework was created by the business community to meet the above requirements. |

Internal control helps entities achieve important objectives and sustain and improve performance. Entities, whether private or public, use internal controls as a means to achieve the objectives of the organization by designing processes that control the risk of the organization. An effective internal control framework requires an entity's management and board of directors to use judgment that is dynamic, integrated, and responsive to the needs of the company,37 rather than rigidly adhere to past policies and procedures.

A COSO framework, depicted in Figure 3, was created to help practitioners assess internal controls not as an isolated issue, but rather as an integrated framework for how internal controls work together across an organization to help achieve the objectives as determined by management.

The cube represents the integrated perspective recommended by COSO for practitioners who are creating and assessing internal controls. The cube may be best understood by examining each set of components separately.

The three objectives—Operations, Reporting, and Compliance—are represented by the columns. The objectives are designed to help an organization focus on different aspects of internal control to help management achieve its objectives.

The five components—Control Environment, Risk Assessment, Control Activities, Information and Communication, and Monitoring Activities—are represented by the rows. The components represent what is required to achieve the three objectives.

An entity's organizational structure—Entity-Level, Division, Operating Unit, and Function—is represented by the third dimension. For an organization to achieve its objectives, according to COSO, internal control must be effective and integrated across all organization levels.38

|

|

Source: COSO, Internal Control - Integrated Framework, Executive Summary, May 2013, p. 6. |

Federal Government

Taxpayers want the government to use their economic resources effectively and efficiently. There is also considerable debate as to whether the current generation of citizens should shift the costs for the benefits derived in the near term to future taxpayers (i.e., deficit spending to meet the current needs of the government). Thus, periodically assessing if the government's financial position has improved or deteriorated is important not only from an economic perspective but also because it has social and political implications.

The financial statements of the U.S. government and its agencies provide taxpayers and Congress a comprehensive view of how the government manages tax revenue and how effective the federal government is at providing services. The financial statements report the U.S. government's financial position and condition, its revenues and costs, assets and liabilities, other responsibilities and commitments, and other financial issues. The U.S. government's financial report is a means of communicating to multiple stakeholders, which are depicted in Figure 4. The Financial Report of the United States Government, issued by the Department of the Treasury, serves the same basic purpose as the annual report issued by a publicly traded company to its investors.

Although the underlying accounting and auditing concepts in the federal government closely follow those in the private sector, the expected outcomes are different. Thus, financial reporting and auditing standards in the federal government have a different focus than in the private sector. The standard-setting body for federal financial reporting is the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB). The standard-setting body for federal auditing standards is the GAO.39

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Accounting

The accounting standards established by FASAB are considered Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for federal financial reporting entities.40 FASAB was created by the GAO, Department of the Treasury, and the Office of Management and Budget; they are also its current sponsors. FASAB is funded by the three sponsors, and its budget for 2017 was $2.0 million.41

According to FASAB, there are four objectives of federal financial reporting.42 The following four objectives, phrased here as FASAB's recommendations, consider the many needs expressed by current and potential users of federal financial information, and they provide a framework for assessing the federal government's existing financial reporting systems:

Budgetary Integrity. Federal financial reporting should assist the government in being accountable in its tax expenditures. Federal financial reporting should thus provide information that helps stakeholders determine

- how budgetary resources have been obtained and used and whether their acquisition and use were in accordance with the legal authorization;

- the status of budgetary resources; and

- how information on the use of budgetary resources relates to information on the costs of program operations, and whether information on the status of budgetary resources is consistent with other accounting information on assets and liabilities.

Operating Performance. Federal financial reporting should provide information for evaluating the services, efforts, costs, and accomplishments of the government. Federal financial reporting should provide information that helps stakeholders determine

- the costs of providing specific programs and activities;

- the efforts and accomplishments associated with federal programs and the changes over time and in relation to costs; and

- the efficiency and effectiveness of the government's management of its assets and liabilities.

Stewardship. Federal financial reporting should help in the assessment of the government's operations and investments for the given period and how, as a result, the government's and the nation's financial condition has changed and may change in the future. Federal financial reporting should provide information that helps to determine whether

- the government's financial position improved or deteriorated over the period;

- future budgetary resources will likely be sufficient to sustain public services and to meet obligations as they come due; and

- government operations have contributed to the nation's current and future well-being.

Systems and Control. Federal financial reporting should assist stakeholders in determining whether financial management systems and internal accounting and administrative controls are adequate to ensure that

- transactions are executed in accordance with budgetary and financial laws and other requirements, consistent with the purposes authorized, and are recorded in accordance with federal accounting standards;

- assets are properly safeguarded to deter fraud, waste, and abuse; and

- performance measurement information is adequately supported.43

Auditing

The financial statements of federal agencies and the U.S. government are audited by inspectors general, independent accounting firms, or GAO. GAO is an independent, nonpartisan agency of Congress. GAO's mission is to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and ensure the accountability of the federal government for the benefit of taxpayers.44 In addition to meeting this legal mandate, GAO also does work at the request of congressional committees. GAO's budget authority for 2017 (excluding offsetting collections) was $545 million.45

GAO issues the Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS), also commonly known as the "Yellow Book," which provides a framework for conducting audits. Some audit organizations within the federal government use a hybrid method of external and internal auditors. Whether external or internal auditors perform the function, they are required to adhere to the standards established under GAGAS.

The Yellow Book requires auditors to consider the visibility and sensitivity of government programs in determining the materiality threshold:46

Additional considerations may apply to GAGAS financial audits of government entities or entities that receive government awards. For example, in audits performed in accordance with GAGAS, auditors may find it appropriate to use lower materiality levels as compared with the materiality levels used in non-GAGAS audits because of the public accountability of government entities and entities receiving government funding, various legal and regulatory requirements, and the visibility and sensitivity of government programs.47

The Yellow Book further notes that audits performed in accordance with GAGAS can lead to improved government management through better decisionmaking and oversight, effective and efficient operations, and accountability and transparency for resources and results.48

Similar to the requirements in the private sector, GAGAS requires federal financial reporting to disclose compliance with laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements that have a material effect on the entities' financial statements.49 In addition to the COSO framework for internal control policies and procedures, GAGAS also recommends utilization of the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government50 and the Internal Control Management and Evaluation Tool51 created specifically for federal government entities by the GAO.52

Whether from academia or other nonprofits that promote specific auditing techniques or guidance, over time practitioners adopt and incorporate best practices from various entities as part of the required audit practice. In addition to the Yellow Book53 issued by the GAO, there are other standards or guidance promulgated by different organizations that influence the auditing standards of the federal government, including54

- The Red Book—International Professional Practices Framework, issued by the Institute of Internal Auditors;55

- The Green Book—Standards for Internal Control in Federal Government, issued by the GAO;56 and

- The Green Book—Principles and Standards for Offices of Inspector General, issued by the Association of Inspectors General.57

State and Local Governments

Similar to the expectations of the federal government, state and local taxpayers expect their respective governments to provide taxpayers and the legislature a comprehensive view of how the government is managing its resources.58 The financial statements issued by state and municipal governments communicate the state or local government's financial position and condition, its revenues and costs, assets and liabilities, and other responsibilities and commitments. The Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) issued by each state or local jurisdiction serves the same purpose as the annual report issued by a publicly traded company to its investors. Those financial statements and annual reports are a means of communicating such information to multiple stakeholders (see Figure 5).

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Because the Constitution limits the power of the federal government on matters that are within the jurisdiction of states, each state or territory has flexibility to choose the accounting and auditing standards that suit its needs.59 The underlying accounting and auditing concepts at the state and local levels are similar to those at the federal level. There is also significant overlap with private-sector accounting and auditing concepts, but the expected outcomes are different. Thus, financial reporting and auditing standards for state and local governments have a different focus than in the private sector and are more closely aligned with the federal government's objectives.

The standard-setting body for state and local governments' accounting standards is the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB). While publicly traded companies are required by the SEC to follow the accounting standards created by FASB, state and municipal governments are not required to follow accounting standards promulgated by GASB. Generally, unless a local government is a recipient of federal funds through grants or shared revenue, it is not required to follow accounting or auditing standards that are applicable to the federal government.

Accounting

The accounting standards established by GASB are considered Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for states and municipalities. A higher-level government such as a state or a county can require all subordinate municipalities or tax authorities to follow GASB accounting standards. States and municipalities can adopt GASB accounting standards without any changes, choose not to adopt a specific standard, or modify a standard to meet their specific needs. Not adopting or changing an accounting standard might allow the entity to report a more positive outcome, especially when revising an accounting standard leads to an economic prediction that is worse than the projection under the previously used standard.60

According to a GASB study, there were 87,575 nonfederal government entities (states and local governments and other government-created entities, such as utilities, water districts, and hospital authorities) in 2008. States have established different policies for whether they and their respective local governments will follow standards (GAAP) as promulgated by GASB. Twenty-seven states are required to follow GAAP as promulgated by GASB. Twenty-eight states require some or all of their counties to follow GAAP. Thirty-six states have laws or regulations that require at least some of their political subdivisions to follow GAAP. Thirty-four states require some or all school districts to follow GAAP. The study also noted that in some states, certain local jurisdictions are required to conform to GAAP, but they do not actually do so, and either no enforcement mechanism is available, or conformance is not enforced.61

GASB is funded by fees collected from broker-dealers by the SEC through the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).62 The accounting support fees are collected by FINRA from member firms that report trades to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB). In other words, broker-dealers that transacted state and municipal securities pay the accounting support fees for GASB. Section 978 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the SEC to collect the support fees from a national securities association that is registered under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.63 GASB incurred $10 million in program and support expenses in 2015. The expenses were primarily paid with $7.4 million from accounting support fees. The remainder of the expenses was paid through other revenue sources, such as sales of publications, or through subsidies from the Financial Accounting Foundation's (FAF's) excess reserve funds. GASB is a subsidiary of FAF.64

According to GASB, financial reporting plays a major role in holding the government accountable to the taxpayer—based on a belief that taxpayers have the right to know how the government is using its resources.65 Information that is made available may lead to debate among citizens and elected officials. GASB identifies three major objectives associated with publicly sharing financial information, and it recommends:

Accountability. Financial reporting should assist in fulfilling government's duty to be publicly accountable and should enable stakeholders to assess that accountability by

- providing information to determine whether current-year revenues are sufficient to pay for current-year services;

- demonstrating whether resources were obtained and used in accordance with the entity's legally adopted budget, and demonstrating compliance with other finance-related legal or contractual requirements; and

- providing information to assist stakeholders in assessing the service efforts, costs, and accomplishments of the governmental entity.

Evaluation by the Public. Financial reporting should assist stakeholders in evaluating the operating results of the governmental entity for the year by

- providing information about sources and uses of financial resources;

- providing information about how it financed its activities and met its cash requirements; and

- providing information necessary to determine whether its financial position improved or deteriorated as a result of the year's operation.

Current and Future Focus. Financial reporting should assist stakeholders in assessing the level of services that can be provided by the governmental entity and its ability to meet its obligations as they come due by

- providing information about its financial position and condition;

- providing information about its physical and other nonfinancial resources that will have useful lives that extend beyond the current year, including information that can be used to assess the service potential of those resources; and

- disclosing legal or contractual restrictions on resources and the risk of potential loss of resources.66

State and local governments seek to meet these objectives through issuing CAFR. The below text box explains the structure and contents of a CAFR.

|

Structure and Contents of a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report A Comprehensive Annual Financial Report is a detailed presentation of a state's or a municipality's financial condition. Each of the three major sections—introductory, financial, and statistical—has subsections. This text box discusses some of the significant subsections. Introductory Section. The introductory section includes basic information about the reporting entity. Elements of the introductory section include the cover, title page, table of contents, list of principal officials, organization chart, and letter of transmittal. If the entity received the Government Finance Officers Association's certificate of achievement for financial reporting, then the certificate will also be included. The letter of transmittal is considered the most important element of the introductory section. It is expected to address the accounting standards followed by the entity; provide a profile of the government; explain the local economy and long-range planning for the jurisdiction; and include the auditor's report. Financial Section. The financial section includes the independent auditor's report, management's discussion and analysis, basic financial statements for the reporting entity and other significant subcomponents, required supplementary information (RSI), combined financial statements, and individual fund statements. RSI might focus on the funding progress of employees' pension plans and other postemployment benefit plans. Combined and individual fund financial statements and schedules present information on funds for which the reporting entity either has custodial or oversight responsibility. Statistical Section. The statistical section typically provides stakeholders with historical perspective, context, detail, associated notes, and required supplementary information to understand and assess a government's economic condition. The statistical section is presented in five categories—financial trends information, revenue capacity information, debt capacity information, demographic and economic information, and operating information.67 |

Auditing

State and municipal government audits are conducted by either an elected or appointed auditor. Elected auditors conduct their work at all levels of government, from states to cities and towns. Appointed auditors are often appointed by the legislature or by the chief executive of the respective municipal organization with the consent of the legislature.68 State and municipal auditors, whether required by law or not, might follow the GAGAS issued by GAO, while making appropriate changes to suit their specific needs.69

While states or municipalities may have differences in their financial reporting and audit needs, the unifying theme of government accountability to its citizens creates more commonality than differences. As an example, states such as California70 and Florida71 either utilize GAGAS for all state audits or tailor the standards to comply with state statute. Cities such as Miami, FL,72 and San Diego, CA,73 also use GAGAS.

In addition to states and local governments utilizing the Yellow Book issued by the GAO, there are other organizations that influence the auditing standards for state and municipal governments.74 The Blue Book issued by the Government Finance Officers Association, for example, provides guidance on accounting, auditing, and financial reporting standards.75

Policy Issues

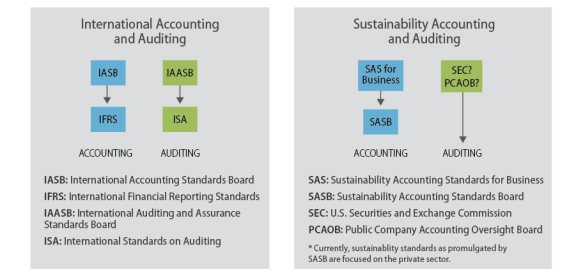

Two policy issues might be of particular interest to Congress and investors. The first is the relationship between accounting and auditing standards in the United States and other countries—in particular, whether or to what degree international accounting and auditing standards should influence U.S. GAAP and U.S. GAAS, respectively. The second is the newly emerging sustainability accounting standards for businesses, which encompass environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. Both of these policy issues are discussed in greater detail below. Figure 6 provides an overview of international accounting and auditing standard-setters and for sustainability accounting and auditing.

|

|

Source: CRS. |

International Standards

Capital markets are global. Investors in the United States invest in foreign firms, and investors from other parts of the world invest in U.S.-based firms. Investors in the United States and elsewhere rely on financial statements to make informed decisions. The earlier discussion about financial statements as a means of communication with various private-sector stakeholders (see Figure 2) is also applicable to international accounting and auditing standards.

Similar to how each state or municipality has discretion to either adopt or modify the accounting standards created by GASB, each country has discretion to either adopt or modify international accounting or auditing standards. To establish a common set of accounting standards, many foreign countries, including those of the European Union (EU), either require or allow International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as their domestic GAAP for firms in their jurisdiction. The EU also accepts U.S. GAAP as equivalent to IFRS. A counterpart to U.S. GAAS is International Standards on Auditing (ISA). This section of the report provides an overview of international accounting and auditing standards and discusses some policy issues that might be of interest to Congress and investors.

Accounting

IFRS and U.S. GAAP fundamentally differ in their approach to creating accounting standards, but they share similar objectives of creating accounting and financial reporting standards that will facilitate efficient capital markets. IFRS is a principles-based accounting standard that provides broad, flexible guidelines that can be applied to a range of situations, but they can lead to inconsistent interpretation and application.76 IFRS is subject to each jurisdiction's interpretation and institutional infrastructure. Countries with lower levels of gross domestic product or less-developed economies can realize savings by working with other countries to develop accounting standards that they can tailor to suit their jurisdictional needs. IFRS is promulgated by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB); see Figure 6.

In contrast to IFRS, U.S. GAAP is generally understood to be a rules-based accounting standard that is less subject to interpretation. U.S. GAAP has evolved over 80 years within the U.S. institutional infrastructure to address the specific needs of the world's largest capital market—the United States.77 In contrast to IFRS, rules-based accounting standards (U.S. GAAP) require specific guidelines to be followed, but they may not address unforeseen issues that may arise in the normal course of business.

Whether IFRS will eventually evolve into a rules-based standard similar to U.S. GAAP may not be known until after it has weathered significant scrutiny from practitioners and the judicial system. Despite the differences, accounting and auditing regulators in the United States and international regulators at times try to coordinate on specific standards.

IFRS has its genesis in the 1973 establishment of the predecessor organization to the International Accounting Standards Board, the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC), by the AICPA and its counterparts in other countries.78 The IASC, unlike FASB and IASB, was essentially a nonbinding agreement rather than a formal body. It was created to establish basic global accounting standards in response to increased economic integration and cross-border capital transactions.79 In 2005, the EU member countries switched from their local GAAP to IFRS. Since 2003, more than 100 countries in varying degrees have either adopted or converged with IFRS.80 The IASB is a member of the IFRS Foundation, which is based in the United Kingdom. Unlike the designated authority granted by the SEC to FASB to set U.S. accounting standards, the IASB is an international body tasked with the responsibility, but not the authority, to promulgate the use of IFRS in member countries.81

In 2015, the IFRS Foundation's income was £30.6 million (British pounds). Contributors to the foundation from the United States include, among many others, the U.S. Federal Reserve, AICPA, Chartered Financial Analyst Institute, Oracle, Citigroup, Deloitte, and KPMG.82

The IASB seeks to promote unified accounting standards through IFRS by broadly defining the principles of specific accounting concepts. Countries have two main ways of incorporating IFRS:

- 1. Adoption. Accept IFRS without any modification as set by IASB (e.g., EU member countries).

- 2. Convergence. Closely align some or all local GAAP within a jurisdiction with IFRS. Convergence can be achieved by either incorporating specific standards from IFRS or modifying the local GAAP to resemble IFRS more closely. For example, in China, IFRS is neither required nor permitted as promulgated by IASB in the original format. The Chinese Accounting Standards have substantially converged with IFRS, but they remain as a distinct standard that is suited for the Chinese governance and judicial system. To a significant degree, IFRS was customized to a more easily understandable format for Chinese markets.83

Similar to FASB, the AICPA, IASB, and other nongovernmental organizations create and promote accounting and auditing rules and guidelines, but they do not have the authority to enforce these in the U.S. private sector.

Auditing

Similar to the expectations that the financial statements of domestic firms should be free of material misstatement whether caused by error or fraud, the same set of expectations exist for financial statements of foreign firms. Foreign firms also engage an auditor to give an unbiased professional opinion on whether the financial statements and related disclosures are fairly stated in all material84 respects for a given period of time in accordance with the established local GAAP. The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) promulgates International Standards on Auditing (ISA) for adoption by each country.

Most of the previous discussion about auditing from the private sector is applicable in the context of international auditing as well. The rest of this section provides background information on IAASB and the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and what, if any, influence the United States has on international auditing standards. IAASB is a member organization of the IFAC.

There are other member organizations within IFAC that focus on creating international accounting standards for the public sector, international ethics standards for accountants, and international educational standards for accountants.85 PCAOB, while not a member, has observer status with IAASB.86

IFAC was founded in 1977 in Munich, Germany, at the 11th World Congress of Accountants. There were 63 founding members from 51 countries, and membership has since grown to include 175 members and associates from 130 countries. AICPA was a founding member of IFAC, and the U.S.-based Institute of Management Accountants is also a member.87 Both IFAC and IAASB are funded by members. IFAC is governed by the IFAC Council and board of directors. The IFAC Council is composed of one representative from each member, and the board is composed of not more than 22 members.

IFAC is overseen by the Public Interest Oversight Board (PIOB),88 which seeks to improve the quality of IFAC standards in the areas of audit, education, and ethics. PIOB in turn is accountable to a monitoring group composed of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors, the World Bank, the European Commission, and the Financial Stability Board. While there are no entities from the United States that are part of PIOB, the United States does have influence through the international organizations it supports, such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the World Bank.89

The Road Ahead for U.S. Accounting and Auditing Standards and International Standards

One aspect of the powers Congress gave the SEC is the authority to establish accounting standards for the private sector in the United States.90 Although the SEC has the Office of the Chief Accountant, whose primary mission is to establish and enforce accounting and auditing policy to ensure that financial statements improve investment decisions, the SEC has relied on the private sector to establish accounting and auditing standards in the United States. As previously discussed, FASB and its predecessor organizations have promulgated U.S. GAAP, with the SEC largely assuming an oversight role—except on the issue of establishing global accounting standards.91 The SEC since the early 2000s has at various times considered adopting IFRS or converging U.S. GAAP with IFRS. If the SEC chooses to switch from U.S. GAAP to IFRS, there may be major implications for U.S. firms and investors, which could be of interest to Congress in its oversight capacity of the SEC.

Congressional interest in accounting convergence has manifested itself in several ways, including hearings, letters to the SEC, and earlier enacted legislation. Congress expressed interest in the convergence of accounting standards at a March 2015 hearing on the SEC's FY2016 budget request held by the House Committee on Financial Services.92 In June 2014, the bipartisan Joint Congressional Caucus on CPAs and Accountants wrote a letter to the SEC Chairman on the issue of convergence. In both instances, some Members of Congress voiced their concerns over "further incorporation of IFRS into the U.S. financial reporting system" and the existence of a "two-GAAP environment, enabling accounting arbitrage; investor confusion arising from differences in accounting treatments; and possible legal challenges."93 Some other Members of Congress have also expressed similar concerns publicly.94 The 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act95 addressed many reforms to the financial industry, but did not specifically address accounting convergence issues.

Earlier congressional interest in IFRS has also manifested itself in enacted legislation that required the SEC to study the issue of adoption. For example, Section 108(d) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 required the SEC to "conduct a study on the adoption by the United States financial reporting system of a principles-based accounting system." 96 The SEC concluded the study as required by SOX in 2003, recommending that U.S standards should be more principles-based, while also recognizing the benefits and limitations of both rules-based and principles-based standards.97

Although the SEC report to Congress in 2003 stated the pursuit of a unified global accounting standard might be in the interest of the United States, a later report by the SEC in 2012 did not make any specific policy recommendations on incorporating IFRS.98 Section 509 of the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 199699 required the SEC to report to Congress on the development of international accounting standards. The study found that the international accounting standards, developed by the IASC, needed to be improved before acceptance could be considered in the United States.100

The future direction of how accounting standards evolve in the United States could be decided by Congress, the SEC, or FASB. To date, Congress has not enacted legislation requiring or prohibiting the incorporation of IFRS. However, if Congress chooses to directly address the issue, it could pass legislation. Alternatively, it could continue to defer to the regulators, as it has since the creation of IFRS in 2003. Although the SEC has the statutory authority for establishing accounting standards in the United States, it has delegated the responsibility to FASB to continue to find common ground with IASB on specific standards.

To date, current and former leadership of the SEC have proposed three different approaches to incorporating IFRS within the United States, without achieving consensus. The first approach, according to then-SEC Chairman Mary Jo White at the aforementioned March 2015 hearing, was the establishment of a single set of high-quality global accounting standards.101

A second approach was proposed by SEC Commissioner Kara M. Stein in a March 2015 speech. In her speech, she stated that a single set of globally recognized, high-quality accounting standards is a "wonderful vision," but with a myriad of shortcomings, and the "debate between dueling standards needs to move on." She also stated that she was not convinced of a need to abandon U.S. GAAP in favor of IFRS. She proposed an alternate approach of developing accounting standards that are responsive to the interconnected digital world, which can minimize the differences between the two and maximize global investment and access to capital.102

A third approach was proposed by then-SEC Chief Accountant James Schnurr that financial statements based on IFRS should be allowed as supplementary information to U.S. GAAP statements. In December 2014, he stated that international regulatory and accounting constituents continue to want clarity on what action, if any, the SEC will take regarding incorporating IFRS into U.S. GAAP.103 In December 2016, current SEC Chief Accountant Wesley Bricker reiterated Schnurr's statements, adding that for the foreseeable future U.S. GAAP best serves the needs of investors and others who rely on financial reporting by U.S. issuers.104

Sustainability Accounting Standards

The investing community and various stakeholders—institutional and individual investors, academics, and advocacy groups—continue to have a long-running debate about what should be disclosed by public firms. Issues related to sustainability accounting standards have been at the forefront of that debate, and shareholder expectations for corporations to address material environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues have continued to increase. In alignment with the increasing shareholder expectations in ESG issues, the percentage of shareholder proposals related to these issues filed with SEC-registered firms increased from 40% to 67% between 2011 and 2016 (see Figure 7).

Sustainability issues include a firm's environmental and social impact as well as how a firm manages environmental and social capital to create long-term value.105 Sustainability topics encompass such issues as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) topics (see Figure 8).

|

Figure 8. Universe of Environmental, Social, and Governance Issues (as defined by SASB) |

|

|

Source: Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Conceptual Framework, October 2013, p. 8. |

Proponents of sustainability accounting standards suggest that investments in material sustainability issues can increase shareholder value by, among other things, differentiating among competitors within each industry, fostering investor confidence, increasing employee trust and loyalty, and increasing access to capital.

Critics argue Congress has enacted regulations that address many of the ESG issues. Additional disclosures and reporting requirements, they say, could be an unneeded regulatory burden for firms.106 Some of the legislation and regulatory requirements that were enacted or revised in the last decade that address ESG issues include CEO pay as compared to median compensation of all other employees,107 clawback provisions on incentive-based compensation,108 disclosure of origins of conflict minerals,109 GAAP requirements to disclose material information to the public, and Regulation S-K—an SEC requirement for firms to share nonfinancial information with investors, the public, and the SEC.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), a U.S.-based non-profit, has created a set of provisional standards to help corporations address increased shareholder interest in ESG issues. Currently, corporate filers with the SEC are not required to follow standards as promulgated by SASB. As discussed below, publicly traded firms are subject to other ESG-related requirements.

Corporations and SASB Disclosure

The SEC does not require disclosures as specified by SASB for publicly traded firms, but there are other regulatory requirements, such as existing GAAP disclosure requirements and Regulation S-K (see text box below), that require significant sustainability issues to be disclosed by publicly traded firms. In addition, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires that upon the sale or disposition of property that triggers environmental remediation obligations and environmental events, a company must disclose the potential material impact to investors in its financial statements. As an example of an ESG disclosure, in the BP Deepwater Horizon oil leak in 2010,110 the related liability was required to be disclosed according to GAAP, as it could have materially affected the company's financial condition.111

In addition to the SEC requirements, there may also be other federal or state requirements mandating disclosure to the public on issues related to sustainability. Similarly, in an international context, either by regulatory requirement or through stock exchanges, over 33 countries have various ESG disclosure requirements.112

Those in favor of an alternative set of requirements for disclosure of ESG issues question how useful the existing disclosure requirements are to investors. Usually, the need to disclose issues related to sustainability arises from concerns over corporate risk. Often, however, sustainability disclosures use boilerplate language meant to meet regulatory requirements or to avoid potential lawsuits. Boilerplate language, arguably, might not give any specifics of potential financial impact but might meet the basic disclosure requirements to avoid a potential lawsuit or fines from regulators.

|

Regulation S-K Regulation S-K provides a framework for sharing nonfinancial information with investors, the public, and the SEC. The regulation was adopted under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to create a uniform and integrated reporting framework for SEC-registered companies. If a firm files certain Forms (S-1, 10-K, and 8-K) with the SEC, then it might be required to address issues surrounding Regulation S-K:

Several sections of the regulation may require disclosure of sustainability issues, but some may be more relevant than others. For example:

|

Sustainability Accounting Standards Board

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) was founded in 2011 as an independent organization to promulgate sustainability accounting standards for the private sector.114 The board has not been recognized by Congress or sanctioned by the SEC as an official standard-setting body for ESG issues. Since it is not an officially sanctioned regulator, any future wholesale implementation of the standards created by SASB are voluntary. According to SASB, its definition of materiality115 is informed by federal securities laws. In defining industry-specific material sustainability issues, SASB considers evidence of shareholder interest, evidence of financial impact, and, in certain circumstances, forward-looking impact, but it does not purport to prescribe to any company or industry what constitutes material disclosure.116 The criteria for materiality under SASB might potentially consider a broader or narrower scope of information; otherwise, firms would be required to disclose material events under existing regulations.

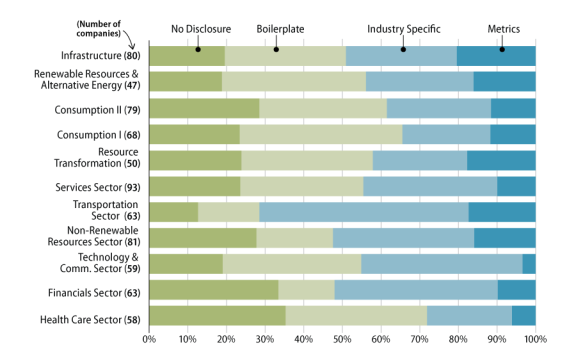

According to SASB, immaterial sustainability issues or boilerplate disclosures have little, if any, effect on shareholder value; thus, identifying material sustainability issues within each industry might provide an increased level of clarity to all stakeholders.117 To evaluate the type of information that is available to shareholders, SASB examined numerous companies and determined there was no consistency in how companies disclosed ESG issues. They ranged from no disclosures or standard boilerplate disclosures to industry-specific disclosures or metrics-based disclosures (see Figure 9).118 Inconsistency makes it harder to measure firm performance within each industry and across different industries. Even if a firm makes an industry-specific or metrics-based disclosure, the disclosures might not be materially relevant, or the disclosures might be a checklist that meets limited objectives without direct correlation to financial performance.

|

|

Source: SASB, Industry-Based Standards for Effective Disclosure of Material Sustainability Information to Investors, December 2016. |

SASB has developed a sustainable industry classification system (SICS)119 to group firms by their resource intensity and by whether or not they face common sustainability opportunities and risks.120 SICS is structured into 79 industry-specific standards in 11 sectors. To be cost-effective each industry-specific standard measures material sustainability disclosure based on 5 topics and 13 metrics. SASB envisions that analysts and investors will be able to compare firms based not only on financial metrics but also on sustainability metrics.

|

How Do You Measure Sustainability? Sustainability issues differ across industries and require different metrics. According to SASB, even climate change manifests itself differently from one industry to the next. Standards that are material and cost-effective need to be industry-specific. As an example, material sustainability topics for the pharmaceutical industry include the following:121 |

|

|

|

SASB's 2015 operating expenses totaled $8.3 million. Funding was provided largely through donors such as Bloomberg Philanthropies, Deloitte, Ford Foundation, Morgan Stanley, and PWC;122 SASB also borrowed $2 million.123

There are other international standards and entities that promote, reinforce, or compete with SASB for disclosing ESG issues. Criticisms of some of these reporting requirements are that they are compliance focused and not focused on materiality, and they do not enhance a firm's value.124 A compliance focus could result in firms certifying that the firm meets a specific reporting requirement without any measurement of how it affects a firm's profitability or how a firm has improved on ESG issues year over year. Those other standards and entities include the following:

- The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) evolved in the late 1990s through two U.S.-based nonprofit organizations, the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies125 and the Tellus Institute.126 Arguably, GRI competes with SASB in many facets of sustainability reporting. There are approximately 2,500 companies that report on sustainability issues based on GRI standards around the world.127 As with SASB, GRI's standards are not formally incorporated as part of the financial reporting structure.

- Dow Jones Sustainability Indices measure the sustainability performance of companies. According to Dow Jones, the indices include only companies that are world leaders with long-term economic, environmental, and social criteria that account for general and industry-specific sustainability trends.128

- International Standards Organization (ISO) 26000—Social Responsibility provides guidance on how businesses and organizations should operate in a socially responsible way that contributes to the health and welfare of society.129

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD's) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises provide nonbinding principles and standards in a global context for business conduct in a socially responsible way.130

- The United Nations Global Compact seeks to engage companies to align strategies and operations with universal principles pertaining to human rights, labor, environment, and anticorruption to take actions that advance the aforementioned societal goals.131

In the arena of competing standards, which standard(s) becomes pervasive throughout the world depends on the usefulness to investors and other stakeholders.

The Road Ahead for Sustainability Accounting Standards

Over the last several years, increased interest in sustainability issues has resulted in corporations voluntarily disclosing information about ESG issues, as evidenced by a 2013 study by Ernst & Young and Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship. According to the study, 95% of the Global 250132 companies issue sustainability reports; in addition, the study found that 53% of S&P 500 companies currently issue sustainability reports.133 Another study found that 86% of the largest 100 companies in the United States reported on sustainability issues.134 Without standardization and focus on materiality, measuring the effectiveness of sustainability efforts by these companies, arguably, is difficult for the investors and other stakeholders. If sustainability accounting standards continue to evolve from the development stage to be an accepted norm by the private sector, Congress may give additional scrutiny to sustainability disclosures in corporate reports.

There are several options that Congress might consider. One option is to let the markets determine what should be disclosed within the existing regulatory structure. If in the long run there is sufficient interest by investors, and SASB standards become widely accepted, then Congress could direct the SEC to require corporate disclosures in compliance with standards promulgated by SASB and standardize the reporting structure. Similarly, federal, state, and local governments might consider utilizing SASB disclosures in their annual reports.

Another option is to require the SEC to undertake a cost-benefit study and assess investor interest in sustainability disclosures in order to formalize and standardize sustainability disclosure as part of SEC filings.

Currently, firms discuss any sustainability issues in the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section of the annual report. MD&A is an SEC requirement; any sustainability issues discussed in the MD&A section are not necessarily subject to independent audit. Should SASB become a GAAP requirement or become pervasive in corporate disclosures, new auditing standards might need to be developed. As with financial accounting standards, SASB and auditing requirements would need to evolve as industries change practices or new industries emerge. In some instances, industry-specific sustainability standards might need to evolve faster than financial accounting standards, if risk factors in certain industries become more volatile or new industries emerge as legacy industries continue to become extinct.