FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act

Changes from November 8, 2017 to June 4, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act

Contents

- Background

- The Budgetary Context

- FY2018 Defense Budget Request

- Limits on the FY2018 Base Budget Defense Appropriations

- FY2018 DOD Military Base Budget Request

- FY2018 DOD Overseas Contingency Operations Budget Request

- Unfunded Priority Lists (UPLs)

- FY2018 NDAA

- Budgetary Overview

- Comparison of Base Budget Authorizations

- Comparison of OCO Authorizations

- Comparison of EDI Authorizations

Selected DefenseBudgetary Context- Budget Caps and the FY2018 NDAA

- FY2018 Defense Budget Request and NDAA

- House and Senate Action on FY2018 NDAA

- FY2018 DOD Budget Amendment (November 2017)

- FY2018 NDAA Conference Report (H.R. 2810)

Selected Budget and Policy Issues in H.R. 2810- Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty

- Deterring Russian Aggression

- North Korean Threats

- Prohibitions on Transfer or Release of Detainees

- Selected DOD Cyber Matters

- Selected Government-Wide Information Technology Matters

- Software Security Issues

Military Personnel Matters- Strategic Nuclear Forces

- Ballistic Missile Defense Programs

- Space and Space-

basedBased Programs and Activities - Overview of Ground Vehicle Programs

- Overview of Shipbuilding Programs

- Selected Aviation Programs

- Acquisition Reform

- Military Construction

Budget Request - Authorization of FY2018 Military Construction Projects

Figures

- Figure 1. Federal Outlays by Budget Category

- Figure 2. Percent of Federal Outlays

- Figure 3. Percent of GDP

- Figure 4. Initial FY2018 National Defense Budget Request (Function 050)

Figure 5

FY2018 Budget for National Defense (050) - Figure 5. Selected Alternative FY2018 National Defense Budget Proposals

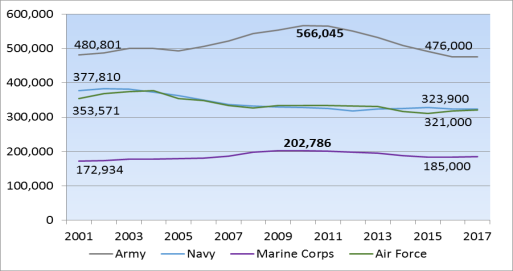

Figure 6. Active-duty End-Strength, 2001-20172018

- Figure

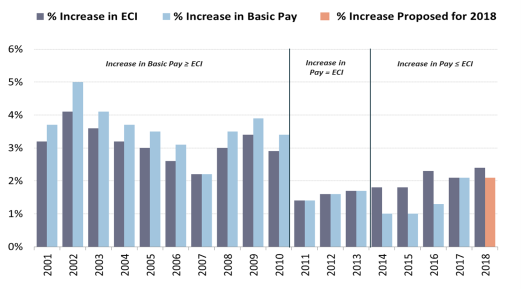

76. Increases in Basic Pay, 2001-2018Tables

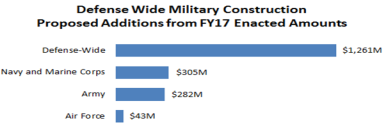

Table 1. Increases in Basic Pay, 2001-2018 - Figure 8. Proposed Changes in the Military Construction Spending, by Military Department

Tables

- Table 1. FY2018 DOD Military Request (Subfunction 051)

Table 2. Administration Proposed Discretionary Limits: FY2018-FY2027- Table

3. FY2018 DOD Military Base Budget Request - Table 4. Troop Levels for Overseas Contingency Operations

- Table 5. FY2018 DOD Overseas Contingency Operations Budget Request

- Table 6. FY2018 Defense Authorizations (as Reported)

- Table 7. FY2018 Proposed DOD Base Budget Authorizations (as reported)

- Table 8. FY2018 Proposed DOD Authorizations for Overseas Contingency Operations (as reported)

Table 9. Proposed Authorizations for European Deterrence Initiative (as reported2. FY2018 NDAA (H.R. 2810/S. 1519)- Table

103. FY2018 Military End-Strength - Table

114. Selected Strategic Offense and Long-range Strike Systems - Table

125. Selected Missile Defense Programs - Table

136. Selected Military Space SystemsSpace Programs - Table

147. Selected Ground Combat Systems and Tactical VehiclesPrograms - Table

158. Selected Shipbuilding and Modernization Programs: Combatant Ships - Table

169. Selected Shipbuilding Programs: Support and Amphibious Assault Ships - Table

1710. Selected Fighter and Attack Aircraft Programs - Table

1811. Selected Tanker, Cargo, and Transport Aircraft Programs - Table

1912. Selected Patrol and Surveillance Aircraft Programs - Table

2013. SelectedHelicoptersHelicopter and Tilt-Rotor Aircraft Programs - Table

21. FY2018 European Reassurance Initiative Military Construction Request Table 22. Proposed Authorization for Selected FY201814. Authorization for Military Construction

Summary

This report discusses the FY2018 defense budget request and provides a summary of congressional action on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for fiscal year (FY) 2018. The annual NDAA authorizes appropriations for the Department of Defense (DOD) and defense-related nuclear energy programs of the Department of Energy and typically includes provisions affecting DOD policies or organization. Unlike an appropriations bill, the NDAA does not provide budget authority for government activities.

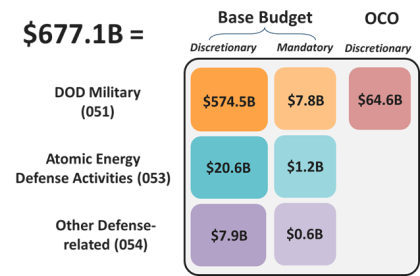

The Trump Administration's The Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for the national defense budget function (Budget Function 050), which encompasses all defensenational defense-related activities of the federal government. Of that amount, $667.6 billion was for discretionary funding that would be provided by an annual appropriations bill. Of that discretionary defense spending request, $659.8 billion was for appropriation accounts for which authorization is provided in the annual NDAA.

On July 14, 2017, the House passed by a vote of 344-81 H.R. 2810, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the House Armed Services Committee. That bill would have authorized $613.8 billion for the base budget—$18.5 billion more than the Administration's initial request—and $74.6 billion designated as OCO funding, which is $10 billion more than the Administration's OCO request. The Senate passed its version of H.R. 2810 on September 18, 2017, by a vote of 89-8, after first replacing the House-passed text of that bill with the text of S. 1519, the version of the FY2018 NDAA that had been reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee. This Senate-passed version of the bill would have authorized $631.9 billion for the base budget—exceeding the base budget request by nearly $37 billion—and $60.0 billion for OCO-designated funding. In November 2017—after the House and Senate had passed their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA but before conferees had completed negotiations to produce a compromise version of the bill—the Trump Administration amended its FY2018 DOD budget request, asking for an additional $5.9 billion. The additional funds included $4.0 billion for missile defense-related programs the Administration described as being in response to recent missile tests and other activities by North Korea. The budget amendment also included $674 million to repair two Navy destroyers damaged in collisions and $1.2 billion to support the President's decision to increase by approximately 3,500 the number of U.S. military personnel in and around Afghanistan. The $1.2 billion associated with the Afghanistan troop levels was designated as OCO while the remaining $4.7 billion of the increase was included in the base budget. The final version of H.R. 2810 authorized $626.4 billion for base budget activities and $65.7 billion for OCO-designated funding. The House agreed to this final version of the bill on November 14, 2017, by a vote of 356-70. The Senate agreed to it on November 16, 2017, by voice vote. President Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-91) on December 12, 2017. Congressional action on FY2018 defense funding reflected a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits (often referred to as caps) on discretionary spending for defense and for nondefense federal activities, set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), remain in place through FY2021. If the amount appropriated for either category were to exceed the relevant cap, it would trigger near-across-the-board reductions to a level allowed by the cap—a process called sequestration. Appropriations designated by Congress and the President as funding for OCO or for emergencies are exempt from these caps. For the period during which Congress was considering the FY2018 NDAA, the BCA limit on discretionary defense spending was $549 billion. The caps apply to appropriations, not authorization legislation. However, if Congress had appropriated for national defense programs the amounts requested by the Administration or the amounts authorized by any of the versions of H.R. 2810 passed by House or Senate, those appropriations would have triggered sequestration. Before Congress enacted any FY2018 appropriations bills, it raised the FY2018 and FY2019 discretionary spending caps on defense and nondefense spending as part of P.L. 115-123, which included the fifth continuing appropriations resolution for FY2018. The revised cap on base budget, discretionary defense appropriations for FY2018 is $629 billion, which would accommodate appropriations to the level authorized by the enacted version of H.R. 2810.The FY2018659.8 billion was for appropriation accounts for which authorization is provided in the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The remainder of the request was either for mandatory funds not requiring annual authorization or for discretionary funds outside the scope of the NDAA.

That initial Administration request included $595.3 billion in discretionary funding for the so-called DOD base budget, that is, funds intended to pay for activities that DODthe Department of Defense (DOD) and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remaining $64.6 billion of the request, formally designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would fund the incremental cost of those ongoing operations as well as any other DOD costs that Congress and the President agree to so designate.

Background

The annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) provides authorization of appropriations for the Department of Defense (DOD), defense-related atomic and elsewhere. The remainder of the request – $64.6 billion – would fund the incremental cost of those ongoing operations, formally designated as Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).

Congressional action on FY2018 defense funding reflects a running debate about the size of the defense budget given strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits on discretionary spending for defense and for non-defense federal activities, set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), remain in place through FY2021. If the amount appropriated for either category exceeds the relevant cap, it would trigger near-across-the-board reductions to a level allowed by the cap – a process called sequestration. Appropriations designated by Congress and the President as funding for OCO or for emergencies, are exempt from the caps.

For FY2018, the BCA limit on discretionary defense spending is $549 billion. Even apart from the request for $8.1 billion in defense-related discretionary appropriations that is outside the scope of the NDAA, the Administration's base budget defense request would exceed the BCA cap by more than $46 billion, thus triggering sequestration.

The House passed H.R. 2810, the version of the FY2018 NDAA reported by the House Armed Services Committee, on July 14, 2017 by a vote of 344-81. On July 10, the Senate Armed Services Committee reported S. 1519, its version of the FY2018 bill. After substituting the text of S. 1519 for the House-passed text of H.R. 2810, the Senate passed an amended version of the latter bill on September 18 by a vote of 89-8.

In terms of the total amounts they would authorize (counting funds for base budget and OCO) the House and Senate proposals differ by slightly more than $3 billion (less than 0.5%). The House bill's $689.0 billion total would exceed the Administration's request by $29.2 billion (about 4.4%), whereas the Senate proposal would exceed the request by $32.3 billion or about 4.8%. The differences between the two bills reflect, in large part, differences in how the chambers categorize and allocate funding for base budget purposes while minimizing the amount by which base budget spending would exceed the BCA cap. Neither bill would modify the FY2018 BCA limit.

Background

The annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) provides authorization of appropriations for the Department of Defense (DOD), defense-related nuclear energy programs of the Department of Energy, and defense-related activities of other federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In addition to authorizing appropriations, the NDAA establishes defense policies and restrictions, and addresses organizational administrative matters related to DOD.1 Unlike an appropriations bill, the NDAA does not provide budget authority for government activities.

|

FY2018 NDAA: Keeping the Numbers Straight Although the House and Senate each passed an FY2018 NDAA designated H.R. 2810, there were hundreds of differences between the two versions. Initially, H.R. 2810 was reported by the House Armed Services Committee and then was debated and amended on the floor of the House before the House passed it on July 14, 2017. The version of the FY2018 NDAA reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee was designated S. 1519. When the Senate began consideration of the NDAA, it called up the House passed bill (H.R. 2810) amended it by In this report, the versions of H.R. 2810 passed by the House and Senate will be referred to as the House bill and Senate bill, respectively. The version of H.R. 2810 reported by the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) and S. 1519 as reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) will be referred to as the HASC version and the SASC version, respectively. All dollar amounts cited in this report are in current dollars. |

Congressional action on the FY2018 NDAA reflectsreflected a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic environment and budgetary issues facing the United States. Annual limits on discretionary spending set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) remain in place through FY2021 and fundamentally shape congressional actions related to all federal spending, including defense funding.2

Constrained by these limits, Congress and the Executive Branchexecutive branch face an increasingly complex and unpredictable international security environment, evidenced by a variety of threats to U.S. security interests including;

Actionaction around the globe bynon-statenonstate, violent extremist organizations–—such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) andal QaidaAl Qaeda;- Russian-backed proxy warfare in Ukraine

and continued investments intended to undermine the NATO alliance; - North Korean provocation evidenced by an "unprecedented" number of missile test launches and its "use of malicious cyber tools" to threaten and destabilize the region;3

- China's expansion of its nuclear enterprise, its investments in power projection and continued island building in the South China Sea; and

- Iran's continued efforts to support international terrorist organizations and establish regional dominance.4

The presidential transition following the November 2016 elections affected the timing of congressional consideration of the FY2018 defense budget request. The Trump Administration transmitted its budget request to Congress on May 23, 2017, 98 days after it was required by law.5 While incoming administrations have tended to submit their budget request later than the statutory deadlines, such delays compress congressional consideration of the request and may result in delays in committee actions and final passage of the authorization and appropriation bills.

The lack of several key strategy documents may also hinder congressional decision-making related to FY2018 defense funding. The Administration is in the process of updating the National Defense Strategy and is also conducting a Nuclear Posture Review. The Administration only recently completed a revision of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan.6 As a result, the Trump Administration's budget request serves as a "placeholder" in many respects while Congress awaits the completion of these and other strategy assessments.7

The Budgetary Context

One exception to that rule is that the Administration's November 2017 amendment to its FY2018 budget request reflected its revision of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan: The additional $5.9 billion requested included $1.2 billion to support the President's decision to deploy in Afghanistan about 3,500 more U.S. personnel than the May 2017 budget request had assumed.6 Although the additional funds were requested after the House and Senate each had passed their respective versions of the NDAA, conferees incorporated the requested amounts into the version of the bill that was enacted. Organization of this Report Congressional action on the FY2018 NDAA took place in the context of a complicated and atypical sequence of events driven by three factors: the ongoing budget debate; the unsettled state of the new Administration's policies when the FY2018 budget request was submitted to Congress; and bellicose statements and actions by the government of North Korea. This report will address aspects of the bill and its context in the following order:The Budget Control Act of 2011Congress completed action on the FY2018 NDAA before the Trump Administration completed its initial updates of the National Defense Strategy and National Security Strategy. A Nuclear Posture Review also was in progress when the bill was enacted. Thus, to some degree, the Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request served as a placeholder while Congress awaited completion of these major strategic assessments.5

The BCA established separate limits (commonly referred to as capscaps) on defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority that are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration.87 Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previously enactedappropriated spending to reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in the BCA. The defense limits applylimit applies to the national defense budget (function 050), but dodoes not restrict amounts provided for "emergencies" or "Overseas Contingency Operations."9designated by the President and Congress as funding for emergencies or for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).8

|

The Budget Control Act For additional information on the BCA, see CRS Report R44039, The Budget Control Act and the Defense Budget: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. |

amounts in billions of dollars Source: OMB Historical Table 8.1.Taking into account actual and projected defense spending over nearly six decades (1962-2022), OMB projects that defense outlays would increase by a multiple of 12.6 (from $52.6 billion to a projected $662.3 billion). Over the same period, net10

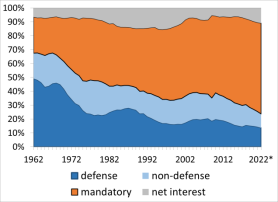

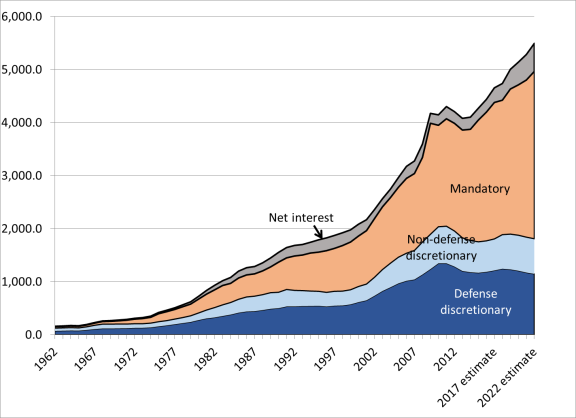

Figure 1. Federal Outlays by Budget Category

Over the nearly six decades from 1962 through 2022, OMB projects that defense outlays would increase from $52.6 billion to a projected $662.3 billion. Over the same period, net9 mandatory spending is projected to increase at roughly 10 times that rate (from $27.9

billionbillion to $3.16 trillion). (See Figure 1.)

to $3.16 trillion). (See Figure 1.)

amounts in billions of dollars |

|

|

Source: OMB Historical Table 8.1. |

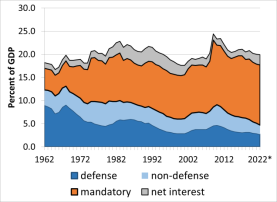

According to OMB data, defense outlays, which accounted for 49.2% of federal spending in 1962, had dropped to 19.4% in 2011 – —the year the BCA was enacted – —and are projected to drop to 13.7% by 2022. On the other hand, net mandatory outlays combined with net interest on the national debt, which accounted for 32.5% of outlays in 1962 and 62.6% in 2011, are projected to account for 76.2% of outlays in 2022. (See Figure 2.)

Similarly, the defense share of the GDP has declinedeclined relatively steadily since 1962, while the share of the GDP consumed by mandatory spending and net interest has risen. (See Figure 3.)

|

|

|

||||||

|

Trends in Federal Spending For information on federal deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. For additional information on mandatory spending, see CRS Report R44641, Trends in Mandatory Spending: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed].

Budget Caps and the FY2018 NDAA

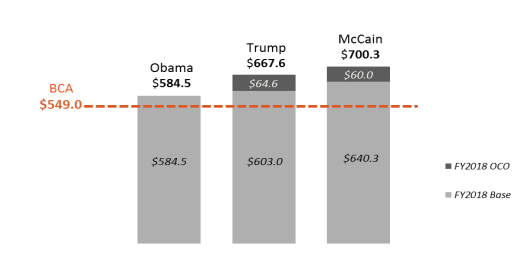

During the period in which Congress was deliberating on the FY2018 NDAA, the BCA limit (or cap) on FY2018 discretionary spending for national defense (budget function 050) was $549 billion. The Trump Administration proposed $603 billion for base budget national defense discretionary spending in FY2018—$54 billion more than the BCA cap. In the absence of the appropriate statutory changes to BCA, defense appropriations at the requested level would have triggered sequestration.10 | |||||||

FY2018 Defense Budget Request

Shortly after taking office, President Trump directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to conduct a "30-day Readiness Review" of "military training, equipment maintenance, munitions, modernization and infrastructure."11 Subsequently, Secretary Mattis issued implementation guidance to DOD that describes a three-phase "campaign" to "build a larger, more capable, and more lethal joint force, driven by a new National Defense Strategy." In the wake of that review, DOD moved out along three axes:

- Submitting a detailed amendment to the Obama Administration's FY2017 budget request – seeking an additional $30 billion to address what it described as "immediate and serious readiness challenges;"12

- Developing the FY2018 Budget Request to be "focus[ed] on balancing the program…while continuing to rebuild readiness;" and

- Beginning formulation of the FY2019-FY2023 Defense Program to be shaped by a new National Defense Strategy and provide "an approach to enchanc[e] the lethality of the joint force against high-end competitors and the effectiveness of our military against a broad spectrum of potential threats."13

In its presentation of the FY2018 budget request, DOD highlighted several priorities:

- Improving warfighting readiness;

- "Filling holes" in capacity and lethality while preparing for future growth;

- Reforming DOD business practices;

- Keeping faith with servicemembers and their families; and

- Supporting overseas contingency operations.14

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for national defense-related activities of the federal government (budget function 050).15 Of the national defense total, $667.6 billion is discretionary spending to be provided, for the most part, by the annual appropriations bill drafted by the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate.16 The remaining $9.6 billion is mandatory spending, that is, spending for entitlement programs and certain other payments. Mandatory spending is generally governed by statutory criteria and it is not provided by annual appropriation acts.17

As has been typical in recent years, about 95% of the national defense total ($646.9 billion) is for military activities of the DOD—referred to as subfunction 051. The balance of the function 050 request comprises $21.8 billion for defense-related nuclear energy activities of the Department of Energy (designated subfunction 053) and $8.4 billion for defense-related activities of other agencies (designated subfunction 054) of which about two-thirds is allocated to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. See Figure 4.

The term base budget is commonly used to refer to funds intended to pay for activities the DOD and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere. In principle, the remainder of the DOD budget request funds the expected incremental cost of those ongoing military operations which are formally designated Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). Appropriations designated for OCO are effectively exempt from the BCA discretionary spending caps.18

For FY2018, the Administration proposes a total DOD budget of $639.1 billion, of which $574.5 billion comprises the discretionary base budget and $64.6 billion is designated as OCO funding. The $574.5 billion request for DOD is a 10% increase from the FY2017 enacted level (see Table 1).

Table 1. FY2018 DOD Military Request (Subfunction 051)

(budget authority in billions of discretionary dollars)

|

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

FY2017-FY2018 Change |

Percentage Change |

|||||||

|

Base |

|

|

|

+10% |

||||||

|

OCO |

|

|

|

- 22% |

||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

+ 5.5% |

Sources: Department of Defense, FY2018 Budget Overview and CBO Estimate on the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (H.R. 244/P.L. 115-31).

Note: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding.

|

Comparison of FY2017 Appropriations with FY2018 Request Any comparison of the FY2018 request to FY2017 enacted amounts should be done with consideration that the FY2017 defense appropriations act (Division C of P.L. 115-31) included $14.8 billion in OCO appropriations in Title X–Additional Appropriations. In addition to $2.1 billion for counter-ISIL activities, these OCO-designated amounts included $12.7 billion that, in general, was drawn from the Trump Administration's March 2017 request for $24.7 billion in additional base budget authority for DOD. |

Limits on the FY2018 Base Budget Defense Appropriations

The current national defense (budget function 050) discretionary limit (or "cap") set by the BCA is $549 billion for FY2018. The Trump Administration proposes $603 billion for base budget national defense discretionary spending in FY2018—$54 billion more than the BCA limit. In the absence of the appropriate statutory changes to BCA, defense appropriations at the requested level would trigger sequestration.19

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget called on Congress to raise the defense discretionary caps for FY2018-FY2021 to accommodate the proposed DOD budget,20 coupled with a recommendation to continue BCA-like limits on discretionary spending through FY2027—six years beyond the expiration of the Budget Control Act (see Table 2).

The Administration's proposed increases in defense spending – which total $463 billion over the period FY2018-FY2027 -- would be more than offset by reductions in non-defense spending that would total $1.5 trillion over the same period. In total, the President's budget proposes a $1 trillion cumulative reduction in federal discretionary spending by establishing such limits.21

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

|

|

Current BCA Limits |

||||||||||

|

Defense |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

|

Non-defense |

516 |

530 |

543 |

556 |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

― |

|

Proposed Limits |

||||||||||

|

Defense |

603 |

616 |

629 |

642 |

655 |

669 |

683 |

697 |

712 |

727 |

|

Non-defense |

462 |

453 |

444 |

435 |

426 |

417 |

409 |

401 |

393 |

385 |

Source: Office of Management and Budget, A New Foundation for American Greatness—President's Budget FY 2018, Table S-7.

Note: The Administration's estimates through FY2022-FY2027 are` based on stated assumptions that programs will "grow at current services growth rates consistent with current law." See footnotes 1-9 to the source table (S-7).

The Trump Administration's proposed increase in base budget national defense spending—above the current statutory cap for FY2018—falls between two other notable FY2018 budget proposals that also would have exceeded the current BCA defense spending cap: the Obama Administration's projected $584.5 billion budget, and a projected budget of $640.3 billion proposed by Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain (see Figure 5).22

(amounts in billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority) |

|

Note: The Obama Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) included a placeholder for Overseas Contingency Operations indicating that funding would be needed, but no actual estimates were provided. |

FY2018 DOD Military Base Budget Request

The DOD's base budget request for FY2018 was a net of $51.3 billion higher than the amount appropriated in FY2017. (See Table 3.)

Table 3. FY2018 DOD Military Base Budget Request

(budget authority in millions of discretionary dollars)

|

Title |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

Change |

Percentage Change |

|

$135,626.0 |

$141,685.6 |

$6,059.7 |

4.5% |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

$167,603.3 |

$188,570.3 |

$20,967.0 |

12.5% |

|

Procurement |

$108,362.8 |

$113,983.7 |

$5,620.9 |

5.2% |

|

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation |

$72,301.0 |

$82,716.6 |

$10,415.6 |

14.4% |

|

Military Construction/Family Housing |

$7,726.0 |

$9,782.5 |

$2,056.5 |

27.0% |

|

$37,127.4 |

$37,896.8 |

$769.4 |

2.1% |

|

General Provisions (net) |

-$3,924.7 |

$123.9 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Total |

$524,795.8 |

$574,759.5 |

$45,889.1 |

8.7% |

Sources: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125. FY2017 enacted amounts obtained from H.Rept. 115-219 to accompany H.R. 3219, Defense Appropriations Act, 2018, comparative tables, p. 322-350. Military construction and family housing enacted amounts obtained from H.R. 5325 (P.L. 114-223).

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding.

a. Military personnel amounts include accrual payments to the Medicare-Eligible Retiree Health Care Fund (MERHCF) which funds "TRICARE for Life" ($6.9 billion in FY2017 enacted and $7.8 billion in FY2018 request). Although they are counted as discretionary appropriations, MERHCF accrual payments occur automatically by the authority of permanent law (10 U.S.C. §1116) and are not included in the annual defense appropriations bills.

b. Includes funding for the Defense Health Program; drug interdiction and counterdrug activities; chemical agents and munitions destruction; and the Office of the Inspector General.

FY2018 DOD Overseas Contingency Operations Budget Request

The FY2018 President's budget request includes $64.6 billion for DOD's Overseas Contingency Operations spending. The request reflects a $5.1 billion reduction from the FY2017 request of $69.7 billion. By comparison, defense appropriations for OCO in FY2017 totaled $82.8 billion, of which approximately $18 billion was designated to fund base budget activities.23

|

Force |

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

|

|

Afghanistan (OFS) |

9,737 |

8,674 |

8,448 |

|

|

Iraq (OIR) |

3,550 |

5,765 |

5,765 |

|

|

In-theater support |

55,831 |

62,486 |

56,310 |

|

|

In CONUS/Other Mobilization |

15,991 |

13,085 |

16,611 |

|

|

Total |

|

90,010 |

87,134 |

|

Source: Department of Defense, FY2018 Defense Budget Overview.

Notes: In-theater support includes Afghanistan, Iraq, Horn of Africa, and ERI.

a. FY2016 Enacted Total (85,109) was reported as 85,108 in the FY2018 Defense Budget Overview

Of the Administration's $64.6 billion request for OCO funding, more than 70% ($45.9 billion) is designated for Operation Freedom's Sentinel (Afghanistan) and overall U.S. Central Command theater posture. The funding requested would maintain 8,448 U.S. military personnel in Afghanistan for train, advise, and assist (TAA) and counterterrorism efforts. Included in this amount is $4.9 billion for the Afghan Security Assistance Fund to continue training and equipping of Afghan security forces, including procurement of aviation assets to support Afghan air force modernization.

The budget request includes $13.0 billion to maintain a force level of 5,765 personnel in Iraq and Syria and support Operation Inherent Resolve. Of the amount requested, $1.8 billion would fund the Counter Islamic State of Iraq and Syria Train and Equip Fund (CTEF)—$1.3 billion for Iraq train and equip (T&E) activities in support of the Iraqi government's security forces and $500 million for Syria T&E in support of forces opposed to the Syrian government that would combat ISIL. The budget also includes $850 million for security cooperation (SC) efforts aimed at building partner capacity, that is, improving the ability of other governments to conduct counterterrorism, perform crisis response and other security activities.24

The OCO request also includes $4.8 billion to enhance U.S. presence in Eastern Europe, often referred to as the European Reassurance Initiative (the ERI). The Administration states that the funding is to provide "near-term flexibility and responsiveness to the evolving concerns of U.S. allies and partners in Europe and helps to increase the capability and readiness of U.S. allies and partners."25 The majority of the requested funding (81%) would enhance U.S. presence in the region, providing $1.7 billion to increase U.S. military personnel presence in Europe and $2.2 billion to increase prepositioned stocks of U.S. military equipment in the region. The request also includes $150 million to "continue train, equip, and advise efforts to build Ukrainian capacity to conduct internal defense operations to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity."26

Table 5 provides a breakdown of the OCO budget request by title.

Table 5. FY2018 DOD Overseas Contingency Operations Budget Request

(budget authority in millions of discretionary dollars)

|

Title |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

||||

|

Military Personnel |

|

| ||||

|

Operation and Maintenance |

|

| ||||

|

Afghanistan Security Forces |

|

| ||||

|

Counter-ISIL |

|

| ||||

|

Procurement |

|

| ||||

|

RDT&E |

|

| ||||

|

Revolving and Management Funds |

|

| ||||

|

Other |

|

| ||||

|

Military Construction |

|

| ||||

|

General Provisions (net) |

|

| ||||

|

Total OCO Budget |

|

|

Sources: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125. FY2017 enacted amounts obtained from H.Rept. 115-219 to accompany H.R. 3219, Defense Appropriations Act, 2018, comparative tables, p. 322-350. Military construction and family housing enacted amounts obtained from H.R. 5325 (P.L. 114-223).

Under the Administration's proposal, projected defense spending increases totaling $463 billion over the period FY2018-FY2027 would be more than offset by reductions in nondefense spending that would total $1.5 trillion over the same period. All told, the President's budget plan proposed a $1 trillion reduction in federal discretionary spending.12 The House and Senate disregarded the defense spending cap in passing their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA and in agreeing to the conference report on a final version of the measure. All versions of the bill (H.R. 2810) authorized defense appropriations at levels which, if enacted, would have exceeded the cap then in force, thus triggering sequestration. After the FY2018 NDAA was enacted, but before final action on any FY2018 appropriations, the caps on discretionary spending for defense and nondefense programs in FY2018 and FY2019 were increased as part of P.L. 115-123, which included the fifth continuing appropriations resolution for FY2018. The revised cap on base budget, discretionary defense appropriations for FY2018 is $629 billion, which would accommodate appropriations to the level authorized by the enacted version of the FY2018 NDAA. Shortly after taking office, President Trump directed Secretary of Defense James Mattis to conduct a "30-day Readiness Review" of "military training, equipment maintenance, munitions, modernization and infrastructure."13 In the wake of that review, DOD moved out along three axes: In its presentation of the initial FY2018 budget request, DOD highlighted several priorities: The Trump Administration's initial FY2018 budget request, released on May 23, 2017, included a total of $677.1 billion for national defense-related activities of the federal government (budget function 050).17 Of the national defense total, $667.6 billion was requested for discretionary spending to be provided, for the most part, by the annual appropriations bill drafted by the Appropriations Committees of the House and Senate. The balance—$9.6 billion—was requested for mandatory spending, that is, spending for entitlement programs and certain other payments. Mandatory spending is generally governed by statutory criteria and it is not provided by annual appropriation acts.18

(dollars in billions) Source: OMB Analytical Perspectives (Table 25-1). Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. OCO is Overseas Contingency Operations. Of the initial, $677.1 billion request, $612.5 billion was for the base budget, that is, for funds intended to pay for those activities the DOD and other national defense-related agencies would pursue even if U.S. forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remainder of the FY2018 request—originally amounting to $64.6 billion—is designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). Originally, the OCO designation was assigned to funding associated with post-9/11 military operations in and around Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the range of DOD activities funded as OCO has broadened. The FY2018 OCO request includes $4.8 billion for the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI), a set of actions intended to beef up the U.S. military presence in Europe as a counter to menacing Russian military actions. The Administration's FY2018 request for ERI included $1.7 billion to increase the number of U.S. military personnel in Europe and $2.2 billion to increase prepositioned stocks of U.S. military equipment in the region. The request also included $150 million to "continue train, equip, and advise efforts to build Ukrainian capacity to conduct internal defense operations to defend its sovereignty and territorial integrity."19 One incentive for expanding the range of DOD spending designated as OCO is that, as such, it is exempt from the BCA funding cap.Notes:

Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. Enacted amounts include $14.8 billion in "Additional Appropriations" provided in H.R. 244, Division C, Title X.

Unfunded Priority Lists (UPLs)

Section 1064 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA/ P.L. 114-328) added 10 U.S.C. §222a to the U.S. Code, requiring each of the armed forces and combatant commanders to report on unfunded priorities.27 The statute defines an "unfunded priority" as a program, activity, or mission requirement that

- 1. is not funded in the President's budget for the fiscal year under consideration;

- 2. is necessary to fulfill a requirement associated with an operational or contingency plan or other validated requirement; and

- 3. would have been recommended for funding if additional resources were available, or if the requirement had emerged after the budget was formulated.28

The military services submitted their FY2018 unfunded priority lists (UPLs)—totaling $32 billion—to Congress on June 1, 2017. The Army identified $12.7 billion in unfunded priorities, including $2.3 billion in funding for activities the Army associated as "Warfighter Readiness."29 The Army's UPL also identified additional funding needed for munitions ($2.3 billion), increased capacity to grow end-strength ($3.1 billion), weapon systems investments for modernization/improved lethality ($4.9 billion), and military construction ($579 million). Of the $4.9 billion in unfunded weapon systems investments, the Army cited air and missile defense, long-range artillery, and munitions as their top priorities.

The Air Force reports $10.7 billion in unfunded priorities including $504 million in personal protective gear for Airmen (helmets, vests, and ruggedized footwear), night vision devices, communications equipment, and increased funding for training. Also listed are $6.7 billion in "Readiness/Modernization" needs including 14 additional F-35s, three additional KC-46s, funding for an EC-130 avionics update, and additional investments in legacy aircraft modification/modernization programs. The Air Force UPL also cites shortfalls in Nuclear Deterrence Operations ($360 million), Space ($772 million), Cyberspace ($563 million) and Infrastructure ($1.8 billion).

The Navy's unfunded priorities total $5.5 billion. The Navy's report to Congress prioritizes weapons systems purchases with requirements for $740 million for 10 F/A-18's, $1.0 billion for 6 additional P-8A Poseidon Aircraft, $390 million for four V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft, and $300 million for 5 ship-to-shore vessels and other weapon systems. Aviation logistics funding is at the bottom of the list, with no mention of shortfalls in major ship repair/overhaul or depot maintenance.

Like the Navy, the Marine Corps stated unfunded priorities are heavily weighted toward aviation system procurements. Of the stated $3.1 billion in unfunded priorities, $2.4 billion is associated with aircraft and aviation systems procurement (six additional F-35s, four additional KC-130J mid-air refueling tankers, two additional CH-53K cargo helicopters, two additional MV-22 tilt-rotor aircraft, seven additional AH-1Z attack helicopters, and two C-40A executive transport aircraft). The Marine Corps report also cites $482 million in unfunded "Ground" priorities, including military construction, facilities sustainment, night optics, and training munitions.

FY2018 NDAA

On July 14, 2017, the House passed H.R. 2810, the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2018, by a vote of 344-81. On September 18, 2017, the Senate passed its version of that bill by a vote of 89-8 after having replaced the text of the House bill with an amended version of S. 1519, the version of the bill that had been reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Before passing the NDAA, the Senate modified the committee-reported text, adopting by unanimous consent In November 2017—after the House and Senate had passed their respective versions of the FY2018 NDAA but before House and Senate conferees had completed work on a compromise version of the bill (H.R. 2810)—the Trump Administration amended its fiscal 2018 budget request, increasing its DOD funding request by a total of $5.87 billion. The requested increase included23 Conferees on the FY2018 NDAA authorized the additional funds requested by the budget amendment.24 The President and Congress designated as emergency funds the $4.7 billion requested for missile defense and ship repair while designating as OCO the funds requested for an enlarged U.S. presence in Afghanistan. Thus, when Congress appropriated those amounts in the FY2018 omnibus appropriations bill, those amounts were exempt from the BCA defense cap. amounts in millions of dollars of discretionary budget authority Title Total Revised Request Missile Defense re: North Korea Repair 2 damaged destroyers Larger force in Afghanistan Procurement 113,983.7 2,423.2 116,406.9 137,311.3 Research, Development, Test and Evaluation 82,716.6 1,346.7 84,063.3 86,348.7 Operation and Maintenance 188,570.3 42.5 673.5 189,286.3 192,290.0 Military Personnel 141,686.1 141,686.1 141,846.4 Revolving Funds and Other auth. 37,849.8 37,849.8 37,676.2 Military Const. and Fam. Housing 9,782.5 200.0 9,982.5 9,980.7 Subtotal: DOD Base Budget 574.589.0 4,012.4 673.5 579,274.8 605,453.3 Atomic Energy Defense Activities 20.477.3 20,477.3 20,597.8 Other Non-DOD Activities 210.0 210.0 300.0 Subtotal: Base Budget 595,276.3 599,962.1 626,351.1 OCO 64,573.0 1,184.1 65,757.1 65,748.3 Grand Total: Base + OCO 659,849.3 4,012.4 673.5 1,184.1 665,719.2 692,099.4 Note: Conferees on the FY2018 NDAA did not consider a separate budget amendment, also submitted in November 2017, that requested $1.16 billion for repair of DOD facilities damaged by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria. The original, House-passed version of the FY2018 NDAA would have authorized a total of about $689.0 billion, exceeding the Administration's initial budget request by about $29.2 billion (4.4%). The original Senate-passed version of the bill would have exceeded the initial request by about $32.3 billion or 4.8%. The conference report on H.R. 2810 does not present the authorization levels in the original House and Senate versions in comprehensive detail, and the number and complexity of floor amendments adopted by each chamber render it infeasible to extract that information from the data available.154 amendments.30an amendment incorporating text from more than 100 amendments.21 Subsequently, the Senate adopted an additional 49 amendments, en bloc, by unanimous consent. In the Senate's only roll call vote onin relation to an amendment to the billNDAA, it voted 61-36 to table (and thus defeatreject) an amendment that would have repealed (six months after enactment of the bill) the joint resolutions on the Authorization of Military Force (AUMF) enacted in 2001 (P.L. 107-40) and in 2002 (P.L. 107-243).22

FY2018 DOD Budget Amendment (November 2017)

OriginalFY2018 Request

Budget AmendmentNovember 2017

Enacted (P.L. 115-91)

Sources: Original request is taken from H.Rept. 115-200, Report of the House Armed Services Committee on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA, July 6, 2017. Data on the November 6, 2017, budget amendment are taken from Office of Management and Budget, "Estimate #3, FY2018 Budget Amendments: Department of Defense to support urgent missile defeat and defense enhancements to counter the threat from North Korea, repair damage to U.S. Navy ships, and support the Administration's south Asia strategy," November 6, 2017, accessed at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/DOD_budgetamendment_package_nov2017.pdf. Total revised request is taken from H.Rept. 115-404, conference report on H.R. 2810, the FY2018 NDAA.

) an amendment that would have repealed (six months after enactment of the bill) the joint resolutions on the Authorization of Military Force (AUMF) enacted in 2001 (P.L. 107-40) and in 2002 (P.L. 107-243).

|

Authorization of the Use of Military Force (AUMF) For additional background and analysis of AUMF, see the following: CRS In Focus IF10539, Defense Primer: Legal Authorities for the Use of Military Forces, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS Report R43983, 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force: Issues Concerning Its Continued Application, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R43760, A New Authorization for Use of Military Force Against the Islamic State: Issues and Current Proposals, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Of the $667.6 billion in national defense discretionary funding requested by the President for FY2018, $659.8 billion falls within the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and is subject to authorization by the annual National Defense Authorization Act (see Table 6).

Budgetary Overview

In terms of the total amount authorized, the House bill and the Senate bill differed by slightly more than $3 billion (less than 0.5%). The House bill's $689.0 billion total would exceed the Administration's request by $29.2 billion (about 4.4%), whereas the Senate proposal would exceed the request by $32.3 billion or about 4.8% (see Table 6).

Despite recommending base budget authorization totals that would exceed the BCA spending limit of $549 billion by upwards of 10%, neither the House bill nor the Senate bill includes a provision that would repeal or modify the BCA limit for FY2018 in current law.31

Table 6. FY2018 Defense Authorizations (as Reported)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Request for NDAA |

|

| |||||||

|

DOD Base Budget |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Atomic Energy Defense Activities |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Defense-related/Maritime Administration |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Subtotal: Base Budget |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) |

|

|

| ||||||

|

OCO for Base Budget Purposes |

|

|

| ||||||

|

GRAND TOTAL: FY2018 NDAA |

|

|

|

Sources: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125.

Notes: The Senate passed the amended text of S. 1519 as an amended version of H.R. 2810.

Totals in this table may not reconcile due to rounding. The Senate Armed Services Committee reporting of the Administration's budget request for DOD is slightly higher than the House Armed Service Committee, rounding to $574.7 billion, as the Senate included $124 million associated with the Compact of the Free Association with Palau (funded in federal budget function 800).

The total amounts recommended for authorization by the House and Senate bills differ by less than $3.2 billion―about 0.45% of the amount they would authorize. Behind those similar totals, however, the two bills differ more strikingly in how they would allocate funds between the base budget and OCO:

- The House bill would authorize $593.4 billion for base budget purposes―an increase of $18.8 billion over the budget request―whereas the Senate bill would authorize $36.3 billion more than the request ($610.9 billion).

- The Senate bill would authorize a total of $60.2 billion designated as OCO funding ($4.4 billion less than the Administration's request), whereas the House bill would authorize $74.6 billion designated as OCO―$10.0 billion more than the Administration requested.

The Administration's base budget request would exceed the BCA defense spending cap. Thus, appropriations provided at that level would trigger sequestration absent a change in the law. The differences between the House and Senate versions of the FY2018 NDAA reflect, in large part, differences in how the chambers would categorize and allocate additional funding for base budget purposes without increasing the amount by which base budget spending would exceed the BCA cap. As a result, comparisons of the amounts that would be authorized by the Administration request and the two versions of the NDAA are complicated by two factors:

OCO-for-Base Authorizations

In addition to authorizing $593.4 billion that was requested by the Administration as base budget funding, the House bill would authorize an additional $10.0 billion that would be designated as OCO funding―and, thus, would be exempt from the BCA cap―but would be spent for base budget purposes. The majority of this OCO-for-base funding would increase procurement amounts by an additional $6.0 billion, all of which would be authorized for shipbuilding activities. In contrast, the Senate bill would not authorize OCO-designated funds for base budget purposes.32

European Defense Initiative Authorizations

Comparison of the base budget authorizations in the House and Senate bills with the Administration's base budget request is also complicated by the bills' handling of the $4.8 billion requested for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI)―an array of investments, deployments, and security assistance grants intended to reassure U.S. allies threatened by Russian military and political maneuvers.33 The Administration included its EDI funding request in the OCO budget, but the House and Senate NDAAs would authorize it largely as part of the base budget.

Comparison of Base Budget Authorizations

The House authorization of OCO-for-base funding, and both committees' rejection of the President's request to designate as OCO most EDI funding complicate comparison of the base budget amounts authorized by the two versions of the bill. One way to compare the Administration's base budget request (Table 7, column "a") with the amounts the House and Senate bills would authorize for that request would be to adjust the base budget authorization totals in the House and Senate bills to eliminate the following realignments in funding:

For the House bill add to the base budget (Table 7, column "b") the bill's "OCO for base" authorizations (Table 7, column "c") and deduct the EDI funds (Table 7, column "d") to get a comparable adjusted base budget total (Table 7, column "e").For the Senate amendment deduct from the base budget (Table 7, column "f") the EDI funds (Table 7, column "g") to get a comparable adjusted base budget total (Table 7, column "h").

Viewed in that light, the two versions of the NDAAs do not differ dramatically in the amounts they would authorize for the major components of the Administration's base budget. The Senate amendment would authorize a net total of $8.0 billion more than the House measure, with procurement funds accounting for the largest share of the difference.

Table 7. FY2018 Proposed DOD Base Budget Authorizations (as reported)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Title |

Request |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Base |

Base |

|

EDI |

|

Base |

EDI |

| |||||||||||||||||

|

Procurement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

RD&E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

O&M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

Military Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

Military Construction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Sources: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125.

Note: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding.

Comparison of OCO Authorizations

Similarly, for a comparison of the OCO funding levels in the budget request and the OCO authorizations proposed by the two versions of the NDAA, one could, in each case, deduct the EDI-related funding (see Table 8).

Table 8. FY2018 Proposed DOD Authorizations for Overseas Contingency Operations (as reported)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Request |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

OCO |

EDI |

|

OCO |

EDI |

|

OCO |

EDI |

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Procurement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

RDT&E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

O&M (excluding Counter ISIL) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Military Personnel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Other (excluding Counter-ISIL) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Military Construction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Source: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125.

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. OCO request shown for the House bill does not include amounts separately authorized in that bill as "OCO for Base". Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund is presented as a separate line because the House bill would authorize it in the O&M title and the Senate amendment would authorize it in the "Other" title.

Comparison of EDI Authorizations

For the most part, the House and Senate bills would support the Administration's EDI request, although they propose to authorize most of the funds as part of the base budget, rather than as OCO funding, as the Administration proposed. The House bill includes a provision (§1275) that would require the Secretary of Defense to submit to the Senate and House Armed Services and Appropriations Committees a plan for the U.S. military role in Europe and for EDI funding through FY2022. The provision also would halt the divestiture of U.S. military sites in Europe, pending receipt of that report.

Both proposals would designate some EDI funding as OCO:

- the House bill would authorize as OCO funding $195 million of the $307 million requested for EDI-related military construction; and

the Senate bill would authorize funding for security assistance to Ukraine in the OCO budget and would add $350 million to the $150 million requested for such activities (seeTable 9).

Table 9. Proposed Authorizations for European Deterrence Initiative (as reported)

millions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

|

Request |

|

| |||||||

|

Base budget |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) |

|

|

| ||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

Source: H.R. 2810, H.Rept. 115-200, S. 1519, and S.Rept. 115-125.

Selected Defense Budget and Policy Issues in H.R. 2810

Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty34

The United States and Soviet Union signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1987. In agreeing to the INF Treaty, the United States and Soviet Union agreed that they would ban all land-based ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The ban would apply to missiles with nuclear or conventional warheads, but would not apply to sea-based or air-delivered missiles. The U.S. State Department has consistently raised concerns about the Russian Federation violating the INF Treaty since 2014. In testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on March 8, 2017, General Paul Selva, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed press reports that Russia had begun to deploy a new ground-launched cruise missile, in violation of the INF Treaty.35

The House bill includes a series of provisions (§. In testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on March 8, 2017, General Paul Selva, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed press reports that Russia had begun to deploy a new ground-launched cruise missile, in violation of the INF Treaty.

The House bill included a series of provisions (§§1241-1248) aimed at compliance enforcement regarding Russian violations of the INF Treaty and other related matters. The Senate bill (§1635) would establishhave established a policy of the U.S.United States regarding actions necessary to bring the Russian Federation back into compliance with the INF Treaty. Both would mandatehave mandated that the Pentagon establish a program of record for the development of a U.S. land-based missile of INF range which, if carried out, would violate the treaty.

The final version of the bill retains the language that requires the Secretary of Defense to "establish a program of record to develop a conventional road-mobile ground-launched cruise missile system with a range of between 500 to 5,500 kilometers" and authorizes $58 million in funding for the development of active defenses to counter INF-range ground-launched missile systems; counterforce capabilities to prevent attacks from these missiles; and countervailing strike capabilities to enhance the capabilities of the United States.

|

The INF Treaty For background and analysis on the INF Treaty see CRS Report R43832, Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Deterring Russian Aggression36

BothCountering Russia26

Like the House and Senate bills includeversions of the bill, the final version of the NDAA includes several policy provisions aimed at deterring Russian aggression and responding to Russian influence operations. Both bills would express support for continued funding for the European Deterrence Initiative at levels similar to the President's budget request. The House bill would further state that it is U.S. policy "to develop, implement, and sustain credible deterrence against aggression" by the Russian government (§1233). The House bill would also require the Secretary of Defense, mostly in coordination with the Secretary of State, to develop and submit strategies, plans, or reports aimed at countering Russian threats and military capabilities, among other objectives (see §1251-1259, §1656). The Senate bill would require the Secretary of Defense to include an assessment of Russian hybrid warfare in an annual report on Russian military and security developments. Both chambers would also require reports on Russian cyberattacks against the Department of Defense (House bill, §1059) or influence operations against members of the Armed Forces (Senate amendment, §1247).37

Both bills would also provide an extension of authorities to provide security assistance – including defensive lethal assistance and intelligence support – to Ukraine (House bill, §1234; Senate amendment, §1243). The Senate bill (§1250) would expand the underlying authorities to include medical treatment of wounded Ukrainian soldiers in certain conditions.

The House bill would express support for U.S. allies and partners Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Georgia (§1237-1238). The Senate amendment would extend authorities for the training of Eastern European national security forces in multilateral exercises and authorize the Secretary of Defense to provide joint security assistance to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to strengthen their resiliency and deterrence against Russian aggression (§1244-1245).

In addition, both chambers would extend existing prohibitions on funding for military-to-military cooperation with Russia and for implementing any activity that would recognize Russian sovereignty over Crimea (House bill, §1231-1232; Senate bill, §1241-1242). The House bill also included three provisions that would restrict contracting with Russian entities:

- §1612 - Restrictions against contracts for satellite services using satellites or launch vehicles designed or manufactured in Russia, or by an entity controlled by the Russian government, except for launches in the United States with engines designed, manufactured in, or provided by entities of Russia.

- §1664 - Restrictions against contracts to procure or obtain telecommunications equipment, systems, or services from Russian government-controlled entities to carry out DOD nuclear deterrence and homeland defense missions.

§3117 - Restrictions against contracts or assistance agreements with Russia for atomic energy defense activitiescountering Russian aggression and malign influence in Europe and expressing support for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI). For example, in the enacted version of H.R. 2810- Section 1273 requires a five-year plan of activities and resources for EDI that would be generally similar to the plan that would have been required by Section 1275 of the House version of the bill;

- Section 1205 extends existing authorities for the training of Eastern European national security forces in multilateral exercises, as would Sections 6209 and 6210 of the Senate version of the bill;

- Section 1279D authorizes the Secretary of Defense to provide joint security assistance to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to improve their interoperability and build capacity to deter aggression, while Sections 1237 and 1238 of the House bill would have expressed support for those three countries and Georgia.

- Section 1234 extends current authorities to provide security assistance—including defensive lethal assistance and intelligence support—to Ukraine, as would the House bill (§1234) and the Senate bill (§6208);

- Section 1234 also expands authorities to provide medical treatment to wounded Ukrainian soldiers and additional forms of military assistance, as would the Senate bill (§6215);

- Sections 1231 and 1232 extend existing prohibitions on funding for military-to-military cooperation with Russia and on activities that would recognize Russian sovereignty over Crimea, echoing language in the House bill (§1231) and the Senate bill (§§1241 and 1242); and

Section 3122 extends existing prohibitions against contracts with or assistance to Russia for atomic energy defense activities, as would Section 3117 of the House bill.

|

Additional Information on the Russian Federation For more information on Russia, see CRS Report R44775, Russia: Background and U.S. Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. |

North Korean Threats

27Both the House and Senate bills both includeincluded sense of Congress provisions related to the importance of the U.S. alliance with the Republic of Korea and threats to U.S. interests and national security posed by North Korea (see §§1264, §1266, and §1270B of the House bill and §1268-§§1268 and 1269 of the Senate bill).

The House bill also would have requiredwould also require the President to provide a report to Congress on cooperation between the Government of Iran and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea on nuclear weapons programs, ballistic missile development, chemical and biological weapons development, and conventional weapons (§1288). The House bill also would have required an assessment and report related to the defense of Hawaii from a North Korea ballistic missile attack (§1685).

The enacted version of the bill includes sense of Congress provisions related to the importance of the U.S. alliances with the Republic of Korea and Japan, the need to strengthen deterrence capabilities in the face of North Korean aggression, and the need to encourage further defense cooperation among the allies (see §§1254 and 1255). It also requires that the President submit a strategy on North Korea, including addressing the DPRK's nuclear weapons programs, ballistic missile development, chemical and biological weapons development, and conventional weapons (§1256). Section 1257 of the conference report requires a briefing by the Secretary of Defense to the armed services committees on the "hazards or risks posed directly or indirectly by the nuclear ambitions of North Korea" including a plan to deter and defend against such threats. The NDAA conference report also adds a requirement that the annual report on the Military Power of Iran also include an assessment of military-to-military cooperation between Iran and North Korea (§1225). The conference report also requires an assessment and report related to the defense of Hawaii from a North Korea ballistic missile attack (§1680 requires an assessment and report related to the defense of Hawaii from a North Korea ballistic missile attack (§1685).

|

Additional Information on North Korea For additional background and information on U.S. |

Prohibitions on Transfer or Release of Detainees

28BothThe final version of H.R. 2810—like the versions passed by the House and Senate bills include—included provisions that would extend until December 31, 2018, previously enacted provisions prohibiting or restricting the transfer or release of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Both include provisions that would extend the prohibition onIn the final billSection 1033 prohibits the use of any funds available to DOD to transfer or release Guantanamo Bay detainees to the United States, its territories, or possessions;

or possessions. However, the Senate bill includes a provision (§1035) that would allow for the temporary transfer of a detainee to the United States for necessary medical treatment that is not available at Guantanamo. Both chambers would also extend prohibitions on the use of any funds available to DOD to transfer or release detainees to Libya, Somalia, Syria, or Yemen. See §1022-1024 of the House bill and §1031-1035 of the Senate bill for the related provisions.

|

Additional Information on Detainee-related Issues For additional background and information see CRS Report R42143, Wartime Detention Provisions in Recent Defense Authorization Legislation, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]; CRS Legal Sidebar WSLG1501, DOD Releases Plan to Close GTMO, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R41156, Judicial Activity Concerning Enemy Combatant Detainees: Major Court Rulings, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

Selected DOD Cyber Matters

The Senate bill included a provision (§1035) that would have allowed the temporary transfer of a detainee to the United States for necessary medical treatment not available at Guantanamo Bay. That provision was not included in the final bill. Both the House and Senate bills includeto transfer or release detainees to Libya, Somalia, Syria, or Yemen; and

. Among such provisions in the House bill are the following:

Section 1651 would requirewhich were incorporated into the final version of the bill, with modifications. House-Originated ProvisionsIn the version of H.R. 2810 originally passed by the House:

Section 1651 would have required the Secretary of Defense to "promptly submit in writing [to Congress] notice of any sensitive military cyber operation and notice of the results of the review of any cyber capability that is intended for use as a weapon;"Section 1654 would require." In the final version of the bill, Section 1631 modifies the House provision to require that the legal reviews of cyber capabilities intended for a weapon be submitted on a quarterly basis in aggregate form. Section 1654 would have required the Secretary of Defense to develop plans to increase regional cyber planning and enhance information operations to counter information operations and propaganda by China and North Korea;. A slightly modified version of that requirement is included in Section 1641 of the final version of the NDAA.

- Section 1655 would

requirehave required a report on the progress of the review of the possible termination of the dual-hat arrangement of the commander of U.S. Cyber Command.

The House Armed Services Committee report on H.R. 2810 also expresses concerns over cyber vulnerabilities, cyber workforce management (training and recruiting), cybersecurity risks of third-party providers (contractors), and the effectiveness of DOD's reporting of cybersecurity incidents.

Senate Provisions

Subtitle C of Title XVI of the Senate bill also includes several provisions related to DOD cybersecurity matters, including the following:

Section 1621 would establish, as a policy of the United States, that the U.S., who also serves as Director of the National Security Agency. This review had been mandated by the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328). The corresponding provision in the final version of the bill (§1648) requires that this report be informed using data from the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation, in consultation with the USCYBERCOM commander and Director of NSA.Senate-Originated ProvisionsIn the version of the FY2018 NDAA originally passed by the Senate:

Section 1621 would have established, as a policy of the United States, that the United States should "employ all instruments of national power, including the use of offensive cyber capabilities, to deter if possible, and respond when necessary, to any and all cyberattacks or other malicious cyber activities that target United States interests...."Section 1622 would requireIn the final version, this was replaced by Section 1633, which requires the President to develop a national policy for the United States relating to cyberspace, cybersecurity, and cyberwarfare. Section 1622 of the original Senate bill would have required the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Secretary ofthe Department ofHomeland Security, and the Secretary of State, to complete a cyber posture reviewnot later than March 1, 2018.- Section 1625 would establish a Strategic Cybersecurity Program to conduct continual "red-teaming" reviews of weapon systems, offensive cyber systems, and critical infrastructure of DOD.

- Section 1663 would require an update on the federal cyber scholarship-for-service program which awards graduate and undergraduate scholarships to students in cyber-security-related programs in return for which recipients agree to work in cybersecurity after graduation for a federal agency or other designated entity for a period equal to the length of the scholarship.

- Section 6608 would require a GAO report on any critical telecommunications equipment manufactured by or incorporating information manufactured by a foreign supplier that is closely linked to a leading cyber threat actor.

Section 6211 would modify the. In the final version of the bill, Section 1644 expanded the scope of the required study to include a review of the role of cyber operations in combatant commander operational planning; a review of the relevant laws, policies, and authorities; and a review of the various approaches to cyber deterrence.- Section 1625 would have established a Strategic Cybersecurity Program to conduct continual "red-teaming" reviews of weapon systems, offensive cyber systems, and critical infrastructure of DOD. This provision was supplanted in the final bill by Section 1640, which calls on the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of the National Security Agency, to submit to the congressional defense committees a plan for carrying out the activities described in the Senate provision.

Section 6211 of the Senate bill would have modified an existing requirement for an annual report on Russian military developments to include Russia's information warfare strategies and capabilities. In the final version of the bill Section 6212 requiresSection 6212 would requirea separate annual report on Russian efforts toprovide propaganda topropagandize members of the U.S.armed forces.Armed Forces.

- Section 1042

would establishof the Senate bill would have established a task force to integrate DOD organizations responsible for information operations, military deception, public affairs, electronic warfare, and cyber operations. - Section 902 would delineate the responsibilities of DOD's Chief Information Warfare Officer.

- Section 1630C would require a report on the applications of Blockchain technology and any efforts by foreign powers, extremist organizations or criminals to utilize these technologies.

Two amendments adopted during Senate floor consideration of the NDAA aim to address shortages in the cyber workforce:

- Section 515 would require DOD to prepare a plan to meet the demand for cyberspace career fields in the reserve components.

- Sections 1661-1664 would expand scholarship programs focused on cybersecurity.

Selected Government-Wide Information Technology Matters

A provision of the original Senate-passed version retained in the final version as Section 1649B requires an update on the federal cyber scholarship-for-service program. This program awards graduate and undergraduate scholarships to students in cyber-security-related programs in return for which recipients agree to work in cybersecurity for a federal agency or other designated entity after graduation for a period equal to the length of the scholarship. A provision in the original Senate-passed provision (§6608) that was not included in the final version of the bill would have required a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on any critical telecommunications equipment manufactured by or incorporating information manufactured by a foreign supplier that is closely linked to a leading cyber threat actor.The Senate bill incorporated In the final bill, Section 1042 requires the Secretary of Defense to establish processes and procedures to integrate strategic information operations and cyberenabled information operations across the responsible organizations. It also requires that a senior DOD official implement and oversee such arrangements.

OPEN Government Act

Section 6012, of the Senate bill incorporated the "Open, Public, Electronic, and Necessary Government Data Act" or (OPEN Government Act), previously had been introduced as S. 760. It would require federal government agencies to catalog and publish their data in formats that are machine usable and to provide a license for open use of thatthose data. This provision mirrorsmirrored recommendations made in the Report of the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, created by P.L. 114-140.38

The final version of the NDAA did not include this provision.

MGT Act