Leveraged Lending and Collateralized Loan Obligations: Frequently Asked Questions

Leveraged lending generally refers to loans made to businesses that are highly indebted or have a low credit rating. Most leveraged loans are syndicated, meaning a group of bank or nonbank lenders collectively funds a leveraged loan made to a single borrower, in contrast to a traditional loan held by a single bank. In some cases, investors hold leveraged loans directly. However, more than 60% of leveraged loans are securitized into collateralized loan obligations (CLOs)—securities backed by cash flow from pools of leveraged loans. These securities are then sold to investors. The largest investors in leveraged loans and CLOs are mutual funds, insurance companies, banks, and pension funds.

During the past decade, the U.S. leveraged loan market experienced periods of growth; it grew by 20% in 2018, bringing the amount outstanding to more than $1 trillion. According to some industry observers, deteriorating credit quality and decreasing investor safeguards have accompanied this growth; however, default rates have remained low. The share of leveraged loans originated by and held by banks has declined, whereas the roles of nonbank participants, such as investment management and finance companies, have increased. In addition, some observers have noted similarities between leveraged lending and CLO market characteristics and those of certain mortgage lending and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets in the lead-up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis. As a result, leveraged lending has raised a number of interrelated policy issues.

Observers express concerns that leveraged lending presents certain financial and economic risks, as both a potential source of systemic risk and a mechanism that could exacerbate a future recession (even if it does not cause financial instability). Leveraged lending could pose systemic risk because it couples high risk with opacity, potentially leading to unexpectedly high losses and financial disruption. Some experts have argued that potential leveraged loan losses or illiquidity could lead to contagion effects, wherein one financial firm’s distress affects other firms and activities. However, banks’ limited exposure to leveraged loans and stronger postcrisis capital and liquidity positions might mitigate contagion effects. For these reasons, some financial authorities (e.g., the chairman of the Federal Reserve) have indicated that although leveraged loans raise some concerns, they “do not appear to present notable risks to financial stability.” Even if leveraged loans do not cause financial instability, some nonfinancial firms that rely on leveraged lending could lose access to financing during the next downturn, which could negatively affect their operations if they were unable to find alternative funding. Overall borrowing by nonfinancial firms is historically high, which could lead to a larger-than-normal cutback in their spending or more corporate failures in the next recession, exacerbating that recession.

Some assert that because certain leveraged loans, such as those involved in private nonbank transactions, face different regulation than leveraged lending by banks and comparable bond issuances, the market might be ineffectively regulated. In addition, some analysts have argued that a lack of transparency in the leveraged lending market prevents the industry and regulators from fully monitoring risks that could be addressed through increased data collection and sharing.

To date, Congress and the financial regulators have mainly limited the policy response to leveraged lending to monitoring risks. A more active regulatory intervention would be complicated by the fact there are few specific regulations governing leveraged lending. (One exception is a supervisory guidance issued by bank regulators in 2013, which the regulators have stressed is nonbinding but the Government Accountability Office declared to be a regulation for Congressional Review Act purposes in 2017.) Addressing systemic risk is under the purview of federal financial regulators, including the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), an interagency council headed by the Treasury Secretary. Although FSOC recommended in its 2018 Annual Report that the financial regulators “continue to monitor levels of nonfinancial business leverage, trends in asset valuations, and potential implications for the entities they regulate,” it did not recommend regulatory or legislative changes to address leveraged lending.

Leveraged Lending and Collateralized Loan Obligations: Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- What Is Leveraged Lending?

- Who Are the Borrowers?

- Who Are the Lenders?

- What Are Loan Syndication and Participation?

- What Are Covenants and Covenant-Lite Loans?

- What Is the Size of the Leveraged Lending Market, and How Much Has It Grown Recently?

- Who Holds Leveraged Loans?

- What Are CLOs?

- Who Holds CLOs?

- Could Leveraged Loans Exacerbate an Economic Downturn?

- What Are the Risks Associated with Leveraged Loans and CLOs?

- How Are Leveraged Loans Regulated?

- How Are Leveraged Loan Issuance and Syndication Regulated?

- What Regulations Do Investors Face When They Hold Leveraged Loans or CLOs?

- How Is the Securitization Process to Create CLOs Regulated?

- What Is the Status of the Bank Regulators' Leveraged Loan Guidance?

- How Has Congress Responded to Leveraged Lending?

Figures

Summary

Leveraged lending generally refers to loans made to businesses that are highly indebted or have a low credit rating. Most leveraged loans are syndicated, meaning a group of bank or nonbank lenders collectively funds a leveraged loan made to a single borrower, in contrast to a traditional loan held by a single bank. In some cases, investors hold leveraged loans directly. However, more than 60% of leveraged loans are securitized into collateralized loan obligations (CLOs)—securities backed by cash flow from pools of leveraged loans. These securities are then sold to investors. The largest investors in leveraged loans and CLOs are mutual funds, insurance companies, banks, and pension funds.

During the past decade, the U.S. leveraged loan market experienced periods of growth; it grew by 20% in 2018, bringing the amount outstanding to more than $1 trillion. According to some industry observers, deteriorating credit quality and decreasing investor safeguards have accompanied this growth; however, default rates have remained low. The share of leveraged loans originated by and held by banks has declined, whereas the roles of nonbank participants, such as investment management and finance companies, have increased. In addition, some observers have noted similarities between leveraged lending and CLO market characteristics and those of certain mortgage lending and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets in the lead-up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis. As a result, leveraged lending has raised a number of interrelated policy issues.

Observers express concerns that leveraged lending presents certain financial and economic risks, as both a potential source of systemic risk and a mechanism that could exacerbate a future recession (even if it does not cause financial instability). Leveraged lending could pose systemic risk because it couples high risk with opacity, potentially leading to unexpectedly high losses and financial disruption. Some experts have argued that potential leveraged loan losses or illiquidity could lead to contagion effects, wherein one financial firm's distress affects other firms and activities. However, banks' limited exposure to leveraged loans and stronger postcrisis capital and liquidity positions might mitigate contagion effects. For these reasons, some financial authorities (e.g., the chairman of the Federal Reserve) have indicated that although leveraged loans raise some concerns, they "do not appear to present notable risks to financial stability." Even if leveraged loans do not cause financial instability, some nonfinancial firms that rely on leveraged lending could lose access to financing during the next downturn, which could negatively affect their operations if they were unable to find alternative funding. Overall borrowing by nonfinancial firms is historically high, which could lead to a larger-than-normal cutback in their spending or more corporate failures in the next recession, exacerbating that recession.

Some assert that because certain leveraged loans, such as those involved in private nonbank transactions, face different regulation than leveraged lending by banks and comparable bond issuances, the market might be ineffectively regulated. In addition, some analysts have argued that a lack of transparency in the leveraged lending market prevents the industry and regulators from fully monitoring risks that could be addressed through increased data collection and sharing.

To date, Congress and the financial regulators have mainly limited the policy response to leveraged lending to monitoring risks. A more active regulatory intervention would be complicated by the fact there are few specific regulations governing leveraged lending. (One exception is a supervisory guidance issued by bank regulators in 2013, which the regulators have stressed is nonbinding but the Government Accountability Office declared to be a regulation for Congressional Review Act purposes in 2017.) Addressing systemic risk is under the purview of federal financial regulators, including the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), an interagency council headed by the Treasury Secretary. Although FSOC recommended in its 2018 Annual Report that the financial regulators "continue to monitor levels of nonfinancial business leverage, trends in asset valuations, and potential implications for the entities they regulate," it did not recommend regulatory or legislative changes to address leveraged lending.

Rapid growth in leveraged lending, a relatively complex form of credit, in the current economic expansion has raised concerns with some policymakers because they have noted similarities between leveraged lending and mortgage lending and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) markets in the lead-up to the 2007-2009 financial crisis. This report explains how leveraged lending works; identifies the borrowers, lenders, and investors who participate in the market; and examines the characteristics of a leveraged loan. It then explains the characteristics of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs)—securities backed by cash flow from pools of leveraged loans—and their investors. Understanding CLOs is crucial to a discussion of the policy issues surrounding leveraged lending because more than 60% of investment in leveraged lending occurs through CLOs. The report also provides data on trends and investor composition. Once these basics are explained, the report explores the regulation of—and some of the potential risks posed by—leveraged lending and CLOs. Finally, it discusses how policymakers have addressed leveraged lending issues to date.

What Is Leveraged Lending?

Put simply, leveraged lending refers to loans to companies that are highly indebted (in financial jargon, highly leveraged). Conceptually, a leveraged loan is understood to be a relatively high-risk loan made to a corporate borrower, but there is no consensus definition of leveraged lending for measurement purposes.1 Instead, different observers or industry groups use various working definitions that may refer to the borrower's corporate credit rating2 or a ratio of the company's debt to some measure of its ability to repay that debt, such as earnings or net worth.3 Because they are high risk, leveraged loans typically have relatively high interest rates, and thus offer higher potential returns for lenders.4

Who Are the Borrowers?

Leveraged loans are made to companies from all industries, and the concentration of leveraged lending in each industry varies over time based on industries' economic conditions. In the second quarter of 2018, healthcare and service were the top two industries using leveraged lending.5 Leveraged loans are often used to complete a buyout or merger, restructure a company's balance sheet (by buying back shares, for example), or refinance existing debt.6

Who Are the Lenders?

Several types of institutions provide funds to borrowers in leveraged lending, including banks, insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, and other private investment funds. Put simply, those institutions are the lenders. However, this concise explanation does not capture certain important characteristics and dynamics within the leveraged lending market.

The institution that originates a leveraged loan rarely, if ever, subsequently holds the loan entirely on its own balance sheet, because a lender often would be wary of taking on a large exposure to a single highly indebted company. Instead, the originating lender typically will either (1) partner with colenders, (2) sell pieces of a single loan to investors, or (3) bundle part or all of the loan into a pool of other leveraged loans in a process called securitization, then sell pieces of the pool to investors. The first two options—referred to as syndication and participation, respectively—are described in more detail below. The third option creates securities called collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), which are described in more detail in the "What Are CLOs?" section. When examining statistics or regulations related to leveraged loans, this report will distinguish between institutions that issue (i.e., originate or create) leveraged loans and institutions that hold (i.e., invest in or purchase pieces of) leveraged loans or CLOs.

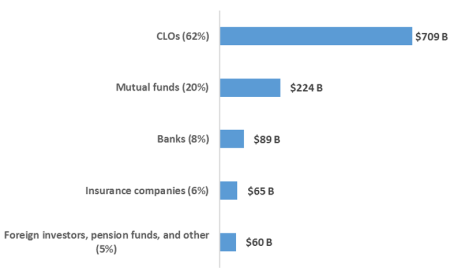

One notable recent trend is the migration of activity from the banking sector to the nonbank sector. Historically, banks played a primary role in both issuing and holding leveraged loans. However, in recent decades, nonbank credit investors, such as private investment funds and finance companies,7 have increasingly overtaken market share.8 As shown in Figure 1, in the primary market, where leveraged loans are first created, bank financing has fallen from about 70% in the mid-1990s to below 10% in 2018, whereas all other nonbank financing combined now comprises more than 90% of leveraged loan investments.9 As discussed below, this migration of activity from the banking industry to nonbank institutions has implications for systemic risk and how leveraged loans are regulated.

|

Figure 1. U.S. Leveraged Loan Investor Base (1994-2018) (Percentage of primary market issuance) |

|

|

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF). |

What Are Loan Syndication and Participation?

In general, a single lender does not want to hold a whole leveraged loan because such loans are large and risky. Instead, lenders typically use economically similar but contractually different arrangements—syndication and participation—to divide the loan among multiple lenders. Under both arrangements, multiple lenders provide a portion of the loan's funding and share in its risk and returns.

The contractual relationship between the parties differs in syndications and participations. In a syndicated loan, the borrower enters into a single loan agreement with multiple lenders. Hence, all lenders have a direct contractual relationship with the borrower.10 Alternatively, a single lender could enter into the loan agreement with the borrower, and this originating lender could then sell portions of the loan, called participations, to other lenders. In this case, the borrower has a direct contractual relationship with the originating lender, who in turn has contractual relationships with the other participants.11 In either case, the loan has in effect been split up between multiple lenders, even though the particulars of the various parties' contractual rights and responsibilities differ.

Syndication and participation require a relatively high degree of coordination among various institutions and stakeholders, and industry practice is that one company acts as an arranger of the deal. The arranger gathers information about the borrower and the loan's purpose, determines appropriate pricing and loan terms, and brings together lenders to join a loan syndication or buy participations. After the deal is closed, the arranger or another company acts as the loan's agent by collecting the payments and fees and passing the appropriate amounts to the loan's holders. The arranger and agent collect fees for these services.12

Traditionally, arrangers and agents were banks, who would also hold a large portion of the loan, and the colenders were also banks. Since the mid-1990s, colenders have increasingly been nonbank lenders, such as finance companies and private investment funds, and the portions of loans held by banks have decreased. In some cases, nonbank lenders have taken on the arranger and agent roles.13 How syndications and participations are regulated is covered in "How Are Leveraged Loans Regulated?"

What Are Covenants and Covenant-Lite Loans?

Leveraged loan agreements typically include covenants—provisions in the loan contract that set conditions the borrower must meet to avoid technical default (as opposed to a payment default, wherein a scheduled payment is missed). Often these conditions relate to indications of the borrower's ability to repay the loan, such as cash flow and financial performance, or restrict certain actions the borrower may take, such as management changes or asset sales.14 If the borrower violates a covenant, the lender can accelerate or call the loan (possibly forcing the borrower into bankruptcy), but often lenders will instead restructure the loan with stricter terms that may include additional restrictions on the borrower's behavior.15

Lenders see covenants as an important mechanism to monitor the borrower's ability to repay the loan and avoid repayment defaults. Loan agreements that include fewer or more lax covenants than are found in traditional leveraged lending contracts are often characterized as covenant-lite. A number of industry observers have noted that covenant-lite loans are becoming more common, and some have argued this indicates credit standards are declining and could lead to higher losses in the future. However, the causes of the increase in covenant-lite loans and the level of concern this trend warrants are subject to debate.16

What Is the Size of the Leveraged Lending Market, and How Much Has It Grown Recently?

The Federal Reserve states that there were approximately $1.15 trillion of leveraged loans outstanding at the end of 2018.17 For comparison, this amount was similar to U.S. auto loans ($1.16 trillion) or credit card debt ($1.06 trillion) outstanding.18

In recent years, leveraged lending has grown much faster than other categories of credit reported by the Federal Reserve (see Table 1). The $1.15 trillion outstanding was a 20.1% increase from a year earlier—more than four times the growth of overall business credit—and annual growth has averaged 15.8% since 2000. By comparison, student loans outstanding grew 5.3% last year and have averaged 9.7% annual growth since 1997.19

|

Loan Type |

Amount Outstanding |

Growth in 2018 |

Long-Term Average Annual Growth |

|

|

Business Credit |

$15.24 trillion |

3.7% |

5.7% |

|

|

Of which: Leveraged Loans |

$1.15 trillion |

20.1% |

15.8% |

|

|

Bonds and Commercial Paper |

$6.24 trillion |

1.4% |

5.7% |

|

|

Bank Lending |

$1.52 trillion |

11.4% |

3.3% |

|

|

Consumer Credit |

$15.63 trillion |

3.2% |

5.5% |

|

|

Of which: Student Loans |

$1.57 trillion |

5.3% |

9.7% |

|

|

Credit Card Loans |

$1.16 trillion |

3.7% |

5.1% |

|

|

Auto Loans |

$1.06 trillion |

3.1% |

3.5% |

|

Source: Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, Table 2.

Note: Due to data availability, the growth period is 1997-2018 for student, auto, and credit card loans, and 2000-2018 for leveraged loans.

In part, the rapid growth in leveraged loans reflects growing nonfinancial business indebtedness, but overall nonfinancial business indebtedness grew only about a fifth as quickly as leveraged lending. This suggests that leveraged lending growth may reflect a substitution of one type of debt for another.20

Who Holds Leveraged Loans?

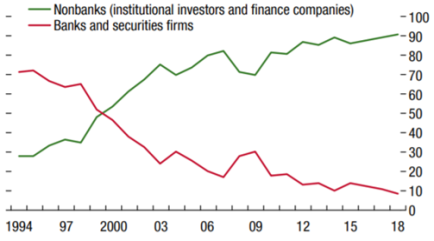

Investors can hold leveraged loans by either (1) investing directly in individual leveraged loans, typically through syndications and participations or (2) investing in CLOs. Institutions that directly hold large shares of outstanding leveraged loans include mutual funds (19%), banks (8%), and insurance companies (6%), as shown in Figure 2.21 According to one study, mutual fund holdings are split fairly evenly between funds offered to institutional investors and funds offered to retail investors.22 Nearly all of the remainder of leveraged loans (62%) are held by CLOs. Portions, or tranches, of CLOs are then sold, largely to the same types of investors that invest directly in leveraged loans. CLOs will be discussed in more detail in the next section. As discussed above, banks' share of funding in the leveraged loan market has exhibited a long-term decline.23

What Are CLOs?

Collateralized loan obligations are securities backed by portfolios of corporate loans.24 Although CLOs can be backed by a pool of any type of business loan, in practice, U.S. CLOs are primarily backed by leveraged loans, according to the Federal Reserve. The outstanding value of U.S. CLOs has grown from around $200 billion at year-end 2006 to $617 billion at year-end 2018.25 As noted above, about 60% of leveraged loans are held in CLOs.

CLOs offer a way for investors to receive cash flows from many loans, instead of being completely exposed to potential payments or defaults on a single loan. To isolate financial risks, CLOs are structured as bankruptcy-remote special purpose vehicles (SPVs) that are separate legal entities. Each CLO has a portfolio manager, who is responsible for constructing the initial portfolio as well as the CLO's ongoing trading activities. CLO managers are primarily banks, investment firms (including hedge funds), and private equity firms.26

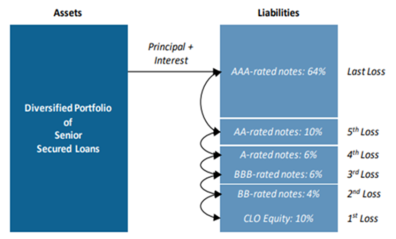

CLOs are sold in separate tranches, which give the holder the right to the payment of cash flow on the underlying loans. The different tranches are assigned different payment priorities, so some will incur losses before others. This tranche structure redistributes the loan portfolios' credit risk. The tranches are often known as senior, mezzanine, and equity tranches, in order from highest to lowest payment priority, credit quality, and credit rating.27 Through this process, the loan portfolio's risks are redistributed to the lower tranches first, and tranches with higher credit ratings are formed.

|

|

Source: Ares Management Corporation, Investing in CLOs, 2019, at http://aresmgmt.com/media/526684/Ares_Investing-in-CLOs-White-Paper_RETAIL_1H-2019.pdf. Note: Hypothetical example for illustration purposes only. |

In general, the financial industry views CLOs' tranched structure as an effective method for providing economic protection against unexpected losses. As Figure 3 illustrates, in the event of default, the lower CLO tranches would incur losses before others. Hence, tranches with higher payment priority have additional protection from losses and receive a higher credit rating. The pricing of the tranches also reflects this difference in asset quality and credit risk, with lower tranches offering potentially higher returns to compensate for greater risks taken.

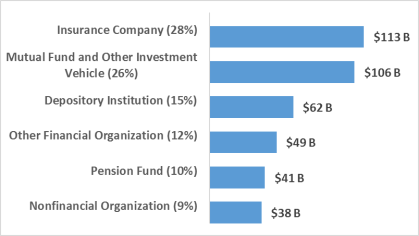

Who Holds CLOs?

CLOs are often sold to institutional investors, including asset managers, banks, insurance companies, and others. The asset management industry, which includes hedge funds and mutual funds, mainly holds the riskier mezzanine and equity tranches, and banks and insurers hold most of the lower-risk senior CLO tranches.28 The Federal Reserve estimated that U.S. investors held approximately $556 billion in CLOs based on U.S. loans at the end of 2018. Of this, an estimated $147 billion in U.S. CLO holdings were issued domestically. Detailed data on domestic CLOs' holders are not available; certain detailed data, however, can be found in the reporting of cross-border financial holdings, which comprise a large majority of U.S. CLOs.29 The cross-border financial reporting indicates that $409 billion of U.S. CLO holdings were issued in the Cayman Islands, apparently the only offshore issuer.30 Figure 4 provides an overview by investor type for domestic holdings of these CLOs.31

|

Figure 4. Domestic Holdings of Cayman-Issued U.S. CLO Securities by Investor Type ($Billions, as of 2018) |

|

|

Source: CRS, following calculations based on Treasury data in Emily Liu and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, "Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?" at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/who-owns-us-clo-securities-20190719.htm. Notes: "Other Financial Organization" includes bank holding companies. "Nonfinancial Organization" includes households. |

Could Leveraged Loans Exacerbate an Economic Downturn?

The rapid growth of leveraged lending has led to concerns that this source of credit could dry up in the next downturn. A slowdown in leveraged loan issuance could pose challenges for the (primarily) nonfinancial companies relying on leveraged loans for financing. Were these firms to lose access to financing, they could be forced to reduce their capital spending, among other operational constraints, if they were unable to find alternative funding sources.32 Capital spending (physical investment) by businesses is typically one of the most cyclical components of the economy, meaning it is highly sensitive to expansions and recessions. Overall borrowing by nonfinancial firms is historically high at present.33 This raises concerns that heavily indebted firms could experience a debt overhang—where high levels of existing debt curtail a firm's ability to take on new debt—in the next downturn. If a debt overhang at nonfinancial firms leads to a larger-than-normal reduction in capital spending or more corporate failures, this might exacerbate the overall downturn.

If a downturn in the leveraged loan market had a negative effect on financial stability, as discussed in the next section, negative effects on the overall economy could be greater.

What Are the Risks Associated with Leveraged Loans and CLOs?

Leveraged loans and CLOs pose potential risks to investors and overall financial stability. Some risks, such as potential unexpected losses for investors, are presented by both leveraged loans and CLOs. Some apply to only one, such as risks posed by securitization presented by CLOs. This section considers the risks posed by both, highlighting differences between the two where applicable.

Risks to investors. Like any financial instrument, leveraged loans and CLOs pose various types of risk to investors. In particular, they pose credit risk—the risk that loans will not be repaid in full (due to default, for example). Credit risk is heightened because the borrowers are typically relatively indebted, have low credit ratings, and, in the case of covenant-lite loans, certain common risk-mitigating protections have been omitted. The ways borrowers often use the funds raised from leveraged loans, such as for leveraged buyouts, can also be high risk. Nevertheless, the overall risk of leveraged loans should not be exaggerated—leveraged loans have historically had lower default rates and higher recovery rates in default than high-yield (junk) bonds, another form of debt issued by financially weaker firms.34 Credit risk is mitigated to a certain degree because leveraged loans are typically secured and their holders stand ahead of the firm's equity holders to be repaid in the event of bankruptcy.35 Furthermore, leveraged loans typically have floating interest rates, so interest rate risk is borne by the borrower, not the investor.

As mentioned in the "What Are CLOs?" section, when leveraged loans are securitized and packaged into CLOs, the credit risk of the original leveraged loans is redistributed by the CLOs' tranched structure, with senior tranches (mostly held by banks and insurers) often receiving the highest credit rating (e.g., AAA) and junior tranches (mostly held by hedge funds and other asset managers) receiving lower credit ratings.36 Subordinated debt and equity positions provide additional protection to the senior tranches. Tranching distributes CLO credit risk differently across investors in different tranches.

Up to this point in the credit cycle, the risks associated with leveraged loans and CLOs have largely not materialized—leveraged loan default rates have been relatively low because of low interest rates and robust business conditions. But some analysts fear that default rates could spike if economic conditions worsen, interest rates rise, or both—and these possibilities may not have been properly priced in. Default rates on leveraged loans rose from below 1% to almost 11% during the last recession.37 An unanticipated spike in default rates would impose unexpected losses on leveraged loan and CLO holders.

Systemic risk. Investment losses associated with changing asset values, by themselves, are routine in financial markets across many types of assets and pose no particular policy concern if investors have the opportunity to make informed decisions. The main policy concern is whether leveraged loans and CLOs pose systemic risk; that is, whether a deterioration in leveraged loans' performance—particularly if it were large and unexpected—could lead to broader financial instability.38 This depends on whether channels exist through which problems with leveraged loans could spill over to cause broader problems in financial markets. Losses on leveraged loans or liquidity problems with leveraged loans could lead to financial instability through various transmission channels discussed below.

During the financial crisis, problems with mortgage-backed securities (MBS) demonstrated how a class of securities can pose systemic risk.39 Similar to CLOs, MBS are complex, opaque securities backed by a pool of underlying assets that are typically tranched, with the senior tranches receiving the highest credit rating. Unexpected declines in housing prices and increases in mortgage default rates revealed that MBS—both highly rated and lowly rated tranches—had been mispriced, with the previous pricing not accurately reflecting the underlying risks. The subsequent repricing led to a cascade of systemic distress in the financial system: liquidity in the secondary market for MBS rapidly declined and fire sales pushed all MBS prices even lower. MBS losses caused certain leveraged and interconnected financial institutions, including banks, investment firms, and insurance companies, to experience capital shortfalls and lose access to the short-term borrowing markets on which they relied. Ultimately, these problems caused financial panic and a broader decline in credit availability as financial institutions deleveraged—reducing new lending activity to restore their capital levels—in response to MBS losses. The resulting reduction in credit in turn caused a sharp decline in real economic activity.

CLOs today share some similarities with MBS before the crisis, but there are important differences. Similarities include the rapid growth in available credit and erosion of underwriting standards. Both types of securities are relatively complex and opaque, potentially obfuscating the underlying assets' true risks. Outstanding leveraged loans and CLOs are small relative to overall securities markets, which in isolation is prima facie evidence that they pose limited systemic risk, even if they were to become illiquid or subject to fire sales. However, before the financial crisis, policy concerns were mainly focused on potential problems in subprime mortgage markets, which were also relatively small. Nevertheless, problems with subprime mortgages turned out to be the proverbial tip of the iceberg, as the deflating housing bubble caused losses in the much-larger overall mortgage market.40 Analogously, a disruption in the leveraged lending market could create spillover effects in related asset classes, similar to how problems that started with subprime mortgages eventually spread to the entire mortgage market and nonmortgage asset-backed securities in the financial crisis. Ultimately, the underlying cause of the MBS meltdown was the bursting of the housing bubble. Despite the high share of business debt to gross domestic product (GDP) at present, experts are divided on whether there is any underlying asset bubble in corporate debt markets (analogous to the housing bubble) that could lead to a destabilizing downturn.41

In addition, it is not clear whether unexpected losses in leveraged lending would lead to broader systemic deleveraging by financial firms or problems for systemically important institutions. Losses on leveraged loans or CLOs might not cause problems for leveraged financial institutions, such as banks, because (1) their leveraged loan and CLO holdings are small relative to total assets and limited mostly to AAA tranches; and (2) banks face higher capital and liquidity requirements to protect against losses or a liquidity freeze, respectively, than they did before the crisis.42 Furthermore, the largest holders of leveraged loans and CLOs are asset managers. They generally hold these assets as agents on their clients' behalf and thus are normally not vulnerable to insolvency from asset losses because those losses are directly passed on to account holders, who own the assets.43

Another source of systemic risk relates to a liquidity mismatch for certain holders. There is potentially an incentive for investors in leveraged loan mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs), respectively, to redeem their shares on demand for cash or sell their shares during episodes of market or systemic distress, similar to a bank run. Because the underlying leveraged loans and CLOs are illiquid, investors who are first to exit could limit their losses if they redeem them while the fund still has cash on hand and is not forced to sell the underlying assets at fire sale prices.44 This incentive could act as a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the incentive to run could cause mass redemptions that then force fire sales that reduce the fund's value. Leveraged loan mutual funds generally allow withdrawal on demand,45 but other run risk may be limited because "U.S. CLOs are not required to mark-to-market their assets, and early redemption by investors is generally not permissible"46 and other private investment funds, such as hedge funds, often feature redemption restrictions.47

Although the financial crisis is a cautionary tale, there are other historical examples where a sudden shift in an asset class's performance did not lead to financial instability. For example, a collapse in the junk bond market following a spike in defaults from 1989 to 1990 did not pose problems for the broader financial system or economy.48 In addition, while CLO issuance slowed during the last financial crisis, the rating agency and data provider Standard & Poor's reports that CLO default rates remained low and "no tranches originally rated AAA or AA experienced a loss" throughout the crisis.49 However, the amount of CLOs outstanding was much smaller then compared to now, and product features have changed over time. More recently, in December 2018, relatively large investor withdrawals from bank loan mutual funds did not result in instability in the leveraged loan market.50

How Are Leveraged Loans Regulated?

The goals of financial regulation, and the tools used to achieve those goals, vary based on the type of financial institution, market, or instrument involved.51 Thus, to answer this question, it is useful to break down leveraged loan regulation by the type of institution and activity (issuance, investment, and securitization).

Leveraged lending falls under the purview of multiple regulators with different regulatory approaches and authorities. This regulatory fragmentation could encourage activities to migrate to less-regulated sectors, limits the official data available, and may complicate the evaluation and mitigation of any potential systemic risk to financial stability associated with leveraged lending.

Following the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), an interagency council of regulators headed by the Treasury Secretary, was created to address threats to financial stability and issues where regulatory fragmentation hinders an effective policy response. In its 2018 Annual Report, FSOC recommended that the financial regulators "continue to monitor levels of nonfinancial business leverage, trends in asset valuations, and potential implications for the entities they regulate."52 Outside of monitoring risk, FSOC has not, to date, recommended any regulatory or legislative changes to address leveraged lending.

How Are Leveraged Loan Issuance and Syndication Regulated?

The regulations applicable to leveraged loan issuance and syndication differ between banks and nonbank lenders. In both cases, though, leveraged lending falls under the laws and regulations applied to business lending in general, rather than rules that apply specifically to leveraged lending.53

In general, banks are required to act in a safe and sound manner to mitigate the potential for failure and are subject to supervision to ensure that they are doing so. As such, regulators generally will check banks' leverage loan origination, syndication, and participation practices as part of regular examinations. This supervision could uncover cases in which a bank is originating or syndicating excessively risky leveraged loans. In addition, the bank regulators have issued guidance documents, most recently in 2013, describing certain standards and practices and communicating regulator expectations related to leveraged lending. Whether this guidance qualifies as regulation that must go through the rulemaking process is a matter of debate examined in the "What Is the Status of the Bank Regulators' Leveraged Loan Guidance?" section later in this report. In any case, the guidance covers only the leveraged loan activities of banks, is not meant to cover nonbank activity or bank investment in CLOs, and cannot address potential systemic risk originating outside of the banking system.

Nonbank participants, with the exception of insurance companies, generally are not subject to similar oversight. To the extent that banks' role in leveraged lending is decreasing, and particularly in cases where a bank is not involved in a leveraged loan at all, this could result in reduced regulatory oversight of leveraged loan issuance and syndication.54

What Regulations Do Investors Face When They Hold Leveraged Loans or CLOs?

Regulations applicable to holding leveraged loans or CLOs depend on what type of entity is involved. Nonbank investment funds, banks, and insurance companies all face different requirements. As with regulations applying to issuance, these rules generally are not uniquely or specifically applied to leveraged loans and CLOs, but rather to all types of loans and assets held by these institutions.

Banks. Banks face a number of prudential (or safety and soundness) regulations related to all bank activities, including leveraged lending. Capital requirements and the Volcker Rule are notable prudential regulations banks must consider when engaged in leveraged lending.

Certain payments banks make on capital are flexible, unlike the rigid payment obligations they face on deposits and liabilities. Thus, capital gives banks the ability to absorb some amount of losses without failing.55 Banks are required to satisfy several requirements to ensure they hold enough capital. In general, these requirements are expressed as minimum ratios between certain balance sheet items that banks must maintain. Leverage ratios require banks to hold a certain amount of capital for all loans regardless of riskiness, whereas risk-weighted ratios require banks to hold an amount of capital based on the riskiness of the loan. When a bank holds leveraged loans or CLO tranches or makes credit available to others to finance leveraged loans or CLOs, it must comply with both types of requirements. Based on the characteristics of individual loans and assets, a bank might be required to hold a relatively large amount of capital for leveraged loans and CLOs to comply with risk-weighted ratios.56

Banks also face certain permissible activity restrictions, which prohibit them from engaging in certain risky activities. Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Act (called the Volcker Rule) is one such regulation that prohibits banks from proprietary trading and certain relationships with hedge funds and certain other funds.57 The latter restriction may be pertinent to banks' involvement in CLOs, depending on how they are structured. Although CLOs may be structured in a manner similar to loan participations (which generally are allowed under the Volcker Rule), they can also be structured such that banks' ownership interests appear similar to those associated with hedge funds (which is generally not allowed under the Volcker Rule). The Volcker Rule establishes criteria for a CLO to qualify for an exemption. Moreover, the final rule provides guidance on how banks may construct CLO structures to avoid retaining impermissible ownership or equity interests that resemble hedge funds.58

In addition, banks are subject to periodic examination by federal bank regulators. If examiners determine a bank is holding overly risky loans, they can give it a worse rating (which in turn could increase the fees it pays for deposit insurance or restrict it from certain activities) or direct it to take corrective action.59 Because leveraged loans are considered more risky than other loan types, they may be more likely to draw examiners' attention and elicit a response.

Furthermore, the bank regulators established the Shared National Credit Program in 1977 to more closely monitor and assess risk related to large syndicated loans. The program requires banks to report data on syndicated loans larger than $100 million.60

To inform banks of their regulatory obligations and regulator expectations related to leveraged lending, the federal bank regulatory agencies have issued a guidance document to banks. Whether this document qualifies as an official regulation, as well as, whether it inappropriately discouraged banks from engaging in leveraged lending, is a subject of debate covered in this report's section "What Is the Status of the Bank Regulators' Leveraged Loan Guidance?" below.

Asset management.61 Relative to banking, investment funds in the asset management industry involve different operational frameworks and regulatory requirements. The asset management industry's operating framework is an agent-based model that separates investment management functions from investment ownership.62 In this model, risk is largely borne by the investors who own the assets, not by the companies managing them. This is different from the model used for banking, in which banks own and retain the assets and risks. Asset managers are generally not subject to safety and soundness regulations that apply to banks.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the primary regulator overseeing the asset management industry. The main components of the SEC's asset management regulatory regime include disclosure requirements, investor access restrictions, examinations, and risk mitigation controls. In addition, the SEC's Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (OCIE) is responsible for conducting examinations and certain other risk oversight of the asset management industry.63 Examples of violations involving leveraged loan capital markets participants that could trigger a SEC investigation include market manipulation and violation of fiduciary duties. Industry self-regulatory organizations under SEC oversight, such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), could also examine broker-dealers involved with leveraged lending.64

Restrictions or requirements for investment funds in the leveraged lending and CLO markets depend on whether a fund is public (broadly accessible by investors of all types) or private (accessible only by institutional and individual investors who meet certain size and sophistication criteria). Public funds that invest in leveraged lending and CLOs include mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), whereas private fund investors include hedge funds and private equity.65 Depending on the types of the funds, they could also be subject to other requirements, such as disclosure of portfolio holdings through prospectus, conflict of interest mitigation through fiduciary requirements, liquidity and leverage restrictions, as well as operational compliance requirements to safeguard client assets.66

Insurance.67 Insurance firms are regulated for safety and soundness, but at the state level rather than by a federal entity.68 Insurance firms also face risk-based capital requirements that affect how many leveraged loans and CLOs they hold. Insurance capital requirements focus significantly on the riskiness of insurers' contingent liabilities (i.e., potential claims), in addition to the riskiness of the assets they hold. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) assigns a risk assessment to the assets (including leveraged loans and CLOs) insurance companies purchase to back their claims. Riskier assets get less credit toward fulfilling those capital requirements. Thus, the risk assessment assigned to individual leveraged loans and CLOs largely determines the limits that capital requirements impose on insurers' holdings of those loans and securities. In 2017, 97% of CLOs held by insurers received an investment-grade rating from the NAIC (NAIC-1 or NAIC-2), posing less expected risk and requiring less capital to guard against that risk than lower-rated holdings.69

A significant difference between the insurance and banking industries, and thus how they are regulated for safety and soundness, is the importance of matching the durations of assets and liabilities in insurance, particularly life insurance. Insurance often entails much longer-term liabilities than does banking, allowing insurers to safely hold longer-term assets to match these longer-term liabilities. This allowance for duration matching may influence the leveraged loans and CLOs an insurer can safely hold. However, insurance regulators have recently increased their focus on the liquidity of insurers' assets, which could discourage insurers from holding many leveraged loans and CLOs because of their relative illiquidity.

How Is the Securitization Process to Create CLOs Regulated?

Through the securitization process, securities (CLOs) backed by leveraged loans are issued and sold to investors. This section highlights the regulatory requirements applied to CLOs and CLO managers. Notably, it discusses the initial application of risk-retention rules to CLOs, and their subsequent partial removal.

The securitization process traditionally allowed managers creating the securities to fully transfer their portfolio assets (and risks) to capital markets investors. This process could result in a misalignment of incentives between managers and investors because the managers did not share much of the securitized products' risks, which has been referred to as a lack of "skin in the game." The 2007-2009 financial crisis revealed this misalignment as a structural flaw that contributed to the crisis. To address the issue, the SEC and other financial regulators adopted credit risk-retention rules under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) for securitization structures, including CLOs, in December 2016.70 The risk retention rule requires CLO managers to retain 5% of the original value of CLO assets, thus aligning their own interests with those of investors (i.e., imposing skin in the game).71 Subsequently, in 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that managers of open-market CLOs, which are reportedly the most common form of CLOs, are no longer subject to risk-retention rules.72 However, other types of CLOs are still subject to risk-retention requirements.

CLOs are securities instruments. The federal securities laws, including the Securities Act of 1933 (P.L. 73-22) and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (P.L. 73-291), require all offers and sales of CLO securities to either be registered under its provisions or qualify for an exemption from registration. Registration requires public disclosure of material information, such as the underlying security's financial details. However, most CLOs are created under private exemptions, which require less registration than public offerings but confine offerings to a more limited investor base.73

As discussed above, a CLO manager oversees the securitization process. CLO managers are generally registered as investment advisers under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. As a result, they are subject to the SEC's registration and compliance requirements as well as the fiduciary duties that obligate them to place clients' interests above their own.74

What Is the Status of the Bank Regulators' Leveraged Loan Guidance?

Bank regulators use guidance to provide clarity to banks on supervision, such as how supervisors treat specific activities in their exams. In 2013, the federal bank regulators jointly issued an updated 15-page guidance document that described their "expectations for the sound risk management of leveraged lending activities."75 Subsequently, banks asserted that following the guidance constrained them from making sound loans and that regulators enforced the guidance as if it were a binding regulation.76 As opposed to guidance, a regulation can be issued only if the agency follows the Administrative Procedure Act's requirements (5 U.S.C. §551 et seq.), including the notice and comment process and other relevant requirements.77 Under the Congressional Review Act (CRA; P.L. 104-121), regulators must submit new regulations and certain guidance documents to Congress, which can then prevent a regulation or guidance from taking effect by enacting a joint resolution of disapproval.78 Because the bank regulators appeared to have the view that the document did not meet the CRA's definition of "rule," they did not submit it to Congress.79

In 2017, Senator Pat Toomey asked the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to analyze the guidance and determine whether it qualified as a rule subject to CRA review.80 GAO concluded that the guidance is a rule subject to CRA review.81 Following GAO's determination, the bank regulators reportedly sent letters to Congress indicating they would seek further feedback on the guidance,82 and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell indicated at a hearing on February 27, 2018, that the Federal Reserve has emphasized to its bank supervisors that the guidance was nonbinding.83 The Comptroller of the Currency, Joseph Otting, reportedly stated in 2018 that the guidance provides flexibility for leveraged loans that do not meet its criteria, provided banks operate in a safe and sound manner.84 To date, no changes have been made to the guidance and no joint resolution of disapproval under the CRA has been introduced. The Congressional Research Service has been unable to locate a submission of the guidance to Congress following the GAO finding that it was required under the CRA.85

How Has Congress Responded to Leveraged Lending?

The House Financial Services Committee held a hearing on June 4, 2019, entitled Emerging Threats to Stability: Considering the Systemic Risk of Leveraged Lending.86 Two unnumbered draft bills related to leveraged lending were considered at this hearing. The draft Leveraged Lending Data and Analysis Act would require the Office of Financial Research, a Treasury office that supports FSOC, to gather information, assess risks, and make recommendations in a report to Congress on leveraged lending. The draft Leveraged Lending Examination Enhancement Act would require the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), an interagency council of federal bank regulators, to set prudential standards for leveraged lending by depository institutions. It would also require the FFIEC to report quarterly on leveraged lending by depository institutions.87

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Because there is no consensus definition of leveraged lending, the data presented in this report might differ from data presented in other sources. |

| 2. |

For example, companies with below-investment-grade ratings. See Katie Kolchin and Chris Killian, Leveraged Lending FAQ and Fact Sheet, Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, March 1, 2019, at https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/leveraged-lending-faq-fact-sheet/. |

| 3. |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending, March 21, 2013, p. 4, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1303a1.pdf. |

| 4. |

Sean Campbell, "Taking It All In: Understanding Leveraged Lending in the U.S. Economy," Financial Services Forum, April 9, 2019, at https://www.fsforum.com/types/press/blog/understanding-leveraged-lending-in-the-u-s-economy/. |

| 5. |

S&P Global Market Intelligence, Leveraged Loan Primer, 2019, at https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/pages/toc-primer/lcd-primer#sec1. |

| 6. |

S&P Global Market Intelligence, Leveraged Loan Primer, 2019. |

| 7. |

Finance companies, put simply, are nonbank institutions that make loans as their main line of business. More specifically, the Federal Reserve defines them as companies whose assets are mostly composed of loans or lease assets, but that are not U.S.-chartered depository institutions, cooperative banks, credit unions, investment banks, or industrial loan corporations. For the full definitions, see Federal Reserve, "Description of table F.128 - Finance Companies," Financial Accounts of the United States, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/fof/TableDesc.aspx?t=F.128. |

| 8. |

International Monetary Fund (IMF), Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, pp. 19-21, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 9. |

Primary market refers to the market where a financial instrument is first created. Secondary market refers to the market where these instruments are traded. Data from IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019. |

| 10. |

FDIC, Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies, Section 3.2-Loans, June 2019, pp. 66-68, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/safety/manual/. |

| 11. |

FDIC, Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies, pp. 33-34. |

| 12. |

See, e.g., Sergey Chernenko, Isil Erel, and Robert Prilmeier, "Nonbank Lending," paper presented at the FDIC's 2018 Banking Research Conference, Arlington, VA, September 6, 2018, pp. 7-9, at https://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/cfr/bank-research-conference/annual-18th/7-erel.pdf; and Marcel Grupp, Taking the Lead: When Non-Banks Arrange Syndicated Loans, Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe, SAFE Working Paper no. 100, 2015, at https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/110186/1/824414217.pdf. |

| 13. |

Marcel Grupp, Taking the Lead: When Non-Banks Arrange Syndicated Loans. |

| 14. |

Mitchell Berlin, Greg Nini, and Edison Yu, Concentration of Control Rights in Leveraged Loan Syndicates, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, working paper no. WP 19-41, October 2019, pp. 10-13, at https://philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2019/wp19-41.pdf. |

| 15. |

Mitchell Berlin, Greg Nini, and Edison Yu, Concentration of Control Rights in Leveraged Loan Syndicates, pp. 1-2. |

| 16. |

Edison Yu, Measuring Cov-Lite Right, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Banking Trends, Third Quarter 2018, at https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/banking-trends/2018/bt-cov_lite.pdf?la=en. |

| 17. |

Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, Table 1, p. 9, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-201905.pdf. |

| 18. |

Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, Table 2, p. 17, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-201905.pdf. |

| 19. |

Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, Table 2, p. 17. |

| 20. |

For example, as net leveraged loan issuance has risen since 2017, net high-yield corporate (junk) bond issuance has declined. High-yield bonds are those issued by business that do not receive an investment-grade credit rating. Federal Reserve System, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, Figure 2-4, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-may-financial-stability-report-borrowing.htm. |

| 21. |

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell, "Business Debt and Our Dynamic Financial System," speech at 24th Annual Financial Markets Conference, Amelia Island, FL, May 20, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20190520a.htm. |

| 22. |

Ayelen Banegas and Jessica Goldenring, Leveraged Bank Loan Versus High Yield Bond Mutual Funds, Federal Reserve, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, no. 2019-047, May 3, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2019047pap.pdf. Institutional investors are organizations that invest on behalf of members (e.g., endowments and pension funds), in contrast to retail investors who invest their own funds directly. |

| 23. |

IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April, 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 24. |

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), Collateralized Loan Obligations Primer, at https://www.naic.org/capital_markets_archive/primer_180821.pdf, and IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 25. |

Emily Liu and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, "Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?" FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, July 19, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/who-owns-us-clo-securities-20190719.htm. |

| 26. |

Stavros Peristiani and João A.C. Santos, "Investigating the Trading Activity of CLO Portfolio Managers," Liberty Street Economics (blog), Federal Reserve Bank of New York, August 3, 2015, at https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2015/08/investigating-the-trading-activity-of-clo-portfolio-managers.html. |

| 27. |

NAIC, Collateralized Loan Obligations Primer, at https://www.naic.org/capital_markets_archive/primer_180821.pdf, and IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April, 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 28. |

IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 29. |

Emily Liu and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, "Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?" FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, July 19, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/who-owns-us-clo-securities-20190719.htm. |

| 30. |

U.S. CLOs are often structured in offshore SPVs to benefit from legal isolation and favorable tax treatments. Around 74% of all U.S. CLO securities held both domestically and abroad were issued out of the Cayman Islands. |

| 31. |

All statistics from Emily Liu and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, "Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?" FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, July 19, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/who-owns-us-clo-securities-20190719.htm. |

| 32. |

IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 33. |

Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-may-financial-stability-report-borrowing.htm. |

| 34. |

Guggenheim Investments, Understanding Collateralized Loan Obligations, May 2019, at https://www.guggenheiminvestments.com/cmspages/getfile.aspx?guid=4510f36e-7ed3-4af3-98c5-6b667d7464e9. |

| 35. |

S&P Global, Leveraged Loan Primer, 2017, at https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/documents/lcd-loan-primer.pdf. |

| 36. |

IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 37. |

Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, Figure 2-6, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-may-financial-stability-report-borrowing.htm. |

| 38. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10700, Introduction to Financial Services: Systemic Risk, by Marc Labonte. |

| 39. |

For an in-depth comparison of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in the financial crisis, see Bank of International Settlements, "Structured Finance Then and Now," BIS Quarterly Review, Box B, September 2019, at https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1909w.htm; and Bank of England, Financial Stability Report, November 2018, Box 4, at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financial-stability-report/2018/november-2018.pdf. |

| 40. |

Juan Ospina and Harald Uhlig, Mortgage-Backed Securities and the Financial Crisis of 2008: a Post Mortem, University of Chicago, Working Paper no. 2018-24, April 2018, at https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/mortgage-backed-securities-and-the-financial-crisis-of-2008-a-post-mortem/. |

| 41. |

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell, "Business Debt and Our Dynamic Financial System," speech at 24th Annual Financial Markets Conference, Amelia Island, FL, May 20, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20190520a.htm. |

| 42. |

Banks provide unfunded revolving credits and letters of credit to finance leverage loans that might obscure their true exposure to leveraged loans. See S&P Global, Leveraged Loan Primer, 2017, at https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/documents/lcd-loan-primer.pdf. |

| 43. |

For general background on the asset management industry, see CRS Report R45957, Capital Markets: Asset Management and Related Policy Issues, by Eva Su. |

| 44. |

For more detail on ETFs and liquidity mismatch, see CRS Report R45318, Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): Issues for Congress, by Eva Su; Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Report, May 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-may-financial-stability-report-borrowing.htm; Bank of International Settlements, "Structured Finance Then and Now," BIS Quarterly Review, Box B, September 2019, at https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1909w.htm; and IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019, at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019. |

| 45. |

These mutual funds hold some liquid assets to provide some protection against withdrawal surges. See Kenechukwu Anadu and Fang Cai, "Liquidity Transformation Risks in U.S. Bank Loan and High-Yield Mutual Funds," FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, August 09, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/liquidity-transformation-risks-in-US-bank-loan-and-high-yield-mutual-funds-20190809.htm. |

| 46. |

Emily Liu and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, "Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?," FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, July 19, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/who-owns-us-clo-securities-20190719.htm. |

| 47. |

Sameer Jain, "Investment Considerations in Illiquid Assets," Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association, Alternative Investment Analyst Review, vol. 2, no. 2, third quarter 2013, pp. 43-44, at https://caia.org/aiar/1952#aiar-default-2. |

| 48. |

Richard H. Jefferis, Jr, "The High-Yield Debt Market: 1980-1990," Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, April 1990, at https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/historical/frbclev/econcomm/econcomm_19900401.pdf. |

| 49. |

S&P Global, CLOs Show Strong Historic Performance With Few Defaults, January 31, 2014, at https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/leveraged-loan-news/sp-report-clos-show-strong-historic-performance-with-few-defaults. |

| 50. |

Kenechukwu Anadu and Fang Cai, "Liquidity Transformation Risks in U.S. Bank Loan and High-Yield Mutual Funds," FEDS Notes, Federal Reserve, August 09, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/liquidity-transformation-risks-in-US-bank-loan-and-high-yield-mutual-funds-20190809.htm. |

| 51. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44918, Who Regulates Whom? An Overview of the U.S. Financial Regulatory Framework, by Marc Labonte. |

| 52. |

Financial Stability Oversight Council, Annual Report, 2018, p. 11, at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/261/FSOC2018AnnualReport.pdf. |

| 53. |

For example, state laws related to secured transactions may affect whether a loan participation qualifies as a "secured interest." See Christopher Whalen, "A Cautionary Tale from the '80s for Today's Loan Participations," American Banker, May 27, 2016, at https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/a-cautionary-tale-from-the-80s-for-todays-loan-participations. |

| 54. |

Marcel Grupp, Taking the Lead: When Non-Banks Arrange Syndicated Loans, Sustainable Architecture for Finance in Europe, SAFE Working Paper no. 100, 2015. |

| 55. |

FDIC, Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies: Section 2.1 Capital, April 2015, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/safety/manual/. |

| 56. |

For more information on capital requirements, see CRS In Focus IF10809, Introduction to Bank Regulation: Leverage and Capital Ratio Requirements, by David W. Perkins. |

| 57. |

For a more information on the Volcker Rule, see CRS In Focus IF10923, Financial Reform: Overview of the Volcker Rule, by Rena S. Miller. |

| 58. |

For more information on the Volcker Rule's application to CLOs, see CRS In Focus IF10736, Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) and the Volcker Rule, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 59. |

For more information on bank exams, see CRS In Focus IF11055, Introduction to Bank Regulation: Supervision, by Marc Labonte and David W. Perkins. |

| 60. |

Federal Reserve, OCC, and FDIC, Shared National Credit Program, 1st and 3rd Quarter 2018 Examinations, Washington, DC, January 2019, p. 3, at https://www.fdic.gov/news/news/press/2019/pr19004a.pdf. |

| 61. |

For more information on asset management, see CRS Report R45957, Capital Markets: Asset Management and Related Policy Issues, by Eva Su. |

| 62. |

For explanations of the principal-agent paradigm, see former Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) assistant chief economist Stewart Mayhew's presentation, "Conflict of Interest Among Market Intermediaries," at https://www.sec.gov/about/offices/oia/oia_market/conflict.pdf. |

| 63. |

SEC, Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations, 2019 Examination Priorities, at https://www.sec.gov/files/OCIE%202019%20Priorities.pdf. |

| 64. |

The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), for example, conducts examination on broker-dealers. See FINRA, "2019 Annual Risk Monitoring and Examination Priorities Letter," January 22, 2019, at http://www.finra.org/industry/2019-annual-risk-monitoring-and-examination-priorities-letter. |

| 65. |

These institutional and retail investors are more sophisticated and higher-net-worth clients who are perceived as better positioned to understand and tolerate risks. |

| 66. |

For more on public and private funds and how they are regulated, see CRS Report R45957, Capital Markets: Asset Management and Related Policy Issues, by Eva Su. |

| 67. |

This section authored in consultation with Baird Webel, Specialist in Financial Economics. For more information on insurance, see CRS In Focus IF10043, Introduction to Financial Services: Insurance, by Baird Webel. |

| 68. |

There is a Federal Insurance Office within the Treasury Department, but its regulatory authority is limited. There is also an independent insurance expert who is a voting member of FSOC. |

| 69. |

National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the Center for Insurance Policy and Research, "U.S. Insurance Industry's Exposure to Collateralized Loan Obligations as of Year-End 2018," Capital Markets Special Report, June 18, 2019, at https://www.naic.org/capital_markets_archive/special_report_190618.pdf. |

| 70. |

OCC, Federal Reserve, FDIC, SEC, Federal Housing Finance Agency, and Department of Housing and Urban Development, Credit Risk Retention Final Rule, at https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2014/34-73407.pdf. |

| 71. |

Among other things, a qualifying sponsor can satisfy the risk-retention requirements through either ownership interests in (1) a single or vertical security representing a 5% face value interest in each class of issued securities, (2) an eligible horizontal residual interest equal to 5% of the fair value of all interests, (3) a cash reserve account funded in an amount equal to 5% of the fair value of all interests, or (4) any combination of clause above and 5% of the fair value of all interests. |

| 72. |

Open-market CLOs are CLOs in which the loan assets are acquired from "arms-length negotiations and trading on an open market," in contrast to "balance sheet CLOs," which are "created, directly or indirectly, by the originators or original holders of the underlying loans to transfer the loans off their balance sheets and into a securitization vehicle." The court observed that open-market CLO managers "neither originate the loans nor hold them as assets at any point. Rather, like mutual fund or other asset managers, CLO managers only give directions to an SPV and receive compensation and management fees contingent on the performance of the asset pool over time." For more details, see Loan Syndications & Trading Ass'n v. SEC, No. 17-5004 (D.C. Cir. Feb. 9, 2018); and Ropes and Gray, "Risk Retentions Rule Overturned for Open-Market CLO Managers," Ropes & Gray (law firm) newsletter, February 18, 2018, at https://www.ropesgray.com/-/media/Files/alerts/2018/02/20180213_CF_Alert.pdf. |

| 73. |

Jennifer Surane and Sally Bakewell, "Citigroup Is Trying to Take CLO Trading Out of the 1990s," Bloomberg, June 20, 2019, at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-20/citigroup-is-trying-to-take-clo-trading-out-of-the-1990s. |

| 74. |

Joseph Suh and Craig Stein, "Collateralized Loan Obligations," The Hedge Fund Journal, March 2013, at https://www.srz.com/images/content/6/8/v2/68003/The-Hedge-Fund-Journal-Collateralized-Loan-Obligations-What-to-E.pdf. |

| 75. |

Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending, March 21, 2013, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1303a1.pdf. |

| 76. |

Bill Nelson, Jeremy Newell, and Greg Bear, Why Leveraged Lending Guidance is Far More Important, and Far More Misguided, Than Advertised, Bank Policy Institute, November 14, 2017, at https://bpi.com/why-leveraged-lending-guidance-is-far-more-important-and-far-more-misguided-than-advertised/. One study found that the 2013 guidance did not reduce banks' leveraged lending, but a 2014 clarification to the guidance did. See Sooji Kim, Matthew C. Plosser, and João A. C. Santos, Macroprudential Policy and the Revolving Door of Risk: Lessons from Leveraged Lending Guidance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report no. 815, May 2017, at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr815.pdf?la=en. |

| 77. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10003, An Overview of Federal Regulations and the Rulemaking Process, by Maeve P. Carey. |

| 78. |

5 U.S.C. §§801-808. For a discussion of the types of agency actions subject to disapproval under the CRA, including guidance documents, see CRS Report R45248, The Congressional Review Act: Determining Which "Rules" Must Be Submitted to Congress, by Valerie C. Brannon and Maeve P. Carey. |

| 79. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—Applicability of the Congressional Review Act to Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending, B-329272, October 19, 2017, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687879.pdf. |

| 80. |

Senator Pat Toomey, "Toomey Praises Guidance Document Clarification from Financial Regulators," press release, September 12, 2018, at https://www.toomey.senate.gov/?p=op_ed&id=2254. |

| 81. |

GAO, OCC, Board of Governors of the Fed, FDIC—Applicability of the Congressional Review Act to Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending, B-329272, October 19, 2017, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687879.pdf. |

| 82. |

Jonathan Schwarzberg and Davide Scigliuzzo, "Exclusive: U.S. regulators offer Congress olive branch on loans," Reuters, December 7, 2017, at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-congress-lending-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-regulators-offer-congress-olive-branch-on-loans-idUSKBN1E12NT. |

| 83. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Monetary Policy and the State of the Economy, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., February 27, 2019, 115-76 (Washington: GPO, 2018), pp. 14-15. |

| 84. |

Jonathan Schwarzberg, "OCC Head Says Leveraged Lending Guidance Needs No Revisions," Reuters, May 24, 2018, at https://www.reuters.com/article/llg-revisions/occ-head-says-leveraged-lending-guidance-needs-no-revisions-idUSL2N1SV24T. |

| 85. |

CRS attempted to identify a record of the guidance having been submitted under the CRA following the GAO opinion by searching through the "Executive Communications" portion of the Congressional Record and did not identify such a record. The Parliamentarian and one or more of the issuing agencies may be able to provide more definitive information on whether it was submitted. Furthermore, the agencies not submitting the guidance did not necessarily preclude Congress from using the CRA to overturn it. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11096, The Congressional Review Act: Defining a "Rule" and Overturning a Rule an Agency Did Not Submit to Congress, by Maeve P. Carey and Valerie C. Brannon. |

| 86. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Emerging Threats to Financial Stability: Considering the Systemic Risk of leveraged Lending, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 4, 2019, at https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=403827. |

| 87. |

The discussion drafts are available at https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=403827. |