Global Trends in Democracy: Background, U.S. Policy, and Issues for Congress

Widespread concerns exist among analysts and policymakers over the current trajectory of democracy around the world. Congress has often played an important role in supporting and institutionalizing U.S. democracy promotion, and current developments may have implications for U.S. policy, which for decades has broadly reflected the view that the spread of democracy around the world is favorable to U.S. interests.

The aggregate level of democracy around the world has not advanced for more than a decade. Analysis of data trend-lines from two major global democracy indexes indicates that, as of 2017, the level of democracy around the world has not advanced since around the year 2005 or 2006. Although the degree of democratic backsliding around the world has arguably been modest overall to this point, some elements of democracy, particularly those associated with liberal democracy, have receded during this period. Declines in democracy that have occurred may have disproportionately affected countries with larger population sizes. Overall, this data indicates that democracy’s expansion has been more challenged during this period than during any similar period dating back to the 1970s. Despite this, democratic declines to this point have been considerably less severe than the more pronounced setbacks that occurred during some earlier periods in the 20th century.

Numerous broad factors may be affecting democracy globally. These include (but are not limited to) the following:

The growing international influence of nondemocratic governments. These countries may in some instances view containing the spread of democracy as instrumental toward other goals or as helpful to their own domestic regime stability. Thus they may be engaging in various activities that have negative impacts on democracy internationally. At the same time, relatively limited evidence exists to date of a more affirmative agenda to promote authoritarian political systems or norms as competing alternatives to democracy.

The state of democracy’s global appeal as a political system. Challenges to and apparent dissatisfaction with government performance within democracies, and the concomitant emergence of economically successful authoritarian capitalist states, may be affecting in particular democracy’s traditional instrumental appeal as the political system most capable of delivering economic growth and national prestige. Public opinion polling data indicate that democracy as a political system may overall still retain considerable appeal around the world relative to nondemocratic alternatives.

Nondemocratic governments’ use of new methods to repress political dissent within their own societies. Tools such as regulatory restrictions on civil society and technology-enhanced censorship and surveillance are arguably enhancing the long-term durability of nondemocratic forms of governance.

Structural conditions in nondemocracies. Some scholars argue that broad conditions in many of the world’s remaining nondemocracies, such as their level of wealth or economic inequality, are not conducive to sustained democratization. The importance of these factors to democratization is complex and contested among experts.

Democracy promotion is a longstanding, but contested, element of U.S. foreign policy. Wide disagreements and well-worn policy debates persist among experts over whether, or to what extent, the United States should prioritize democracy promotion in its foreign policy. Many of these debates concern the relevance of democracy promotion to U.S. interests, its potential tension with other foreign policy objectives, and the United States’ capacity to effectively promote democratization.

Recent developments pose numerous potential policy considerations and questions for Congress. Democracy promotion has arguably not featured prominently in the Trump Administration’s foreign policy to this point, creating potential continued areas of disagreement between some Members of Congress and the Administration. Simultaneously, current challenges around the world present numerous questions of potential consideration for Congress. Broadly, these include whether and where the United States should place greater or lesser emphasis on democracy promotion in its foreign policy, as well as various related questions concerning the potential tools for promoting democracy.

Global Trends in Democracy: Background, U.S. Policy, and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Varying Definitions of Democracy

- Democracy Promotion, Congress, and U.S. Policy

- Identification with U.S. Strategy and Interests

- Global Trends

- Measures of the State of Democracy Around the World

- Freedom House's Freedom in the World Report

- The Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index

- Interpreting the Declines

- Factors Potentially Affecting Democracy Globally

- Geopolitics and Authoritarian Power

- Challenges to Democracy's Global Appeal as a Political System

- Modern Methods of Political Control

- Structural Conditions

- Debates over Democracy Promotion in U.S. Foreign Policy

- Relationship to U.S. Interests

- Potential Tension with Other U.S. Policy Objectives

- Capacity and Effectiveness

- Issues for Congress

- How does the Trump Administration view democracy promotion?

- How much emphasis should the United States place on democracy promotion?

- What tools exist for targeted U.S. foreign policy responses to particular challenges?

- How much funding should be provided for democracy promotion programs?

- How can democracy programs be meaningfully evaluated and/or usefully targeted?

- Should the United States work to form new international initiatives to defend democracy?

- Outlook

Figures

- Figure 1. Freedom in the World's Political Rights and Civil Liberties Ratings Since 1972

- Figure 2. Freedom in the World's Political Rights Changes by Subcategory, 2005 vs. 2017

- Figure 3. Freedom in the World's Civil Liberties Changes by Subcategory, 2005 vs. 2017

- Figure 4. Democracy Index Global Average Since 2006

- Figure 5. Democracy Index Changes by Category, 2006 vs. 2017

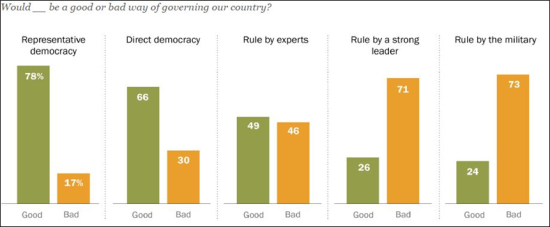

- Figure 6. Level of Support for Democracy Versus Nondemocratic Alternatives

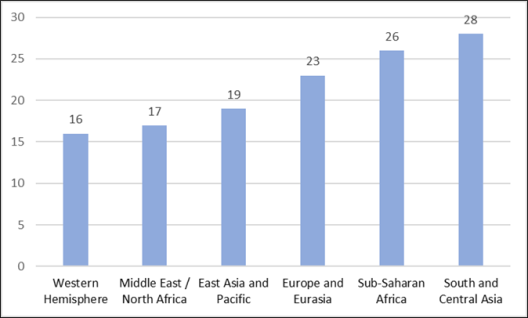

- Figure 7. Geographic Distribution of Initiatives to Restrict Civil Society

Tables

Summary

Widespread concerns exist among analysts and policymakers over the current trajectory of democracy around the world. Congress has often played an important role in supporting and institutionalizing U.S. democracy promotion, and current developments may have implications for U.S. policy, which for decades has broadly reflected the view that the spread of democracy around the world is favorable to U.S. interests.

The aggregate level of democracy around the world has not advanced for more than a decade. Analysis of data trend-lines from two major global democracy indexes indicates that, as of 2017, the level of democracy around the world has not advanced since around the year 2005 or 2006. Although the degree of democratic backsliding around the world has arguably been modest overall to this point, some elements of democracy, particularly those associated with liberal democracy, have receded during this period. Declines in democracy that have occurred may have disproportionately affected countries with larger population sizes. Overall, this data indicates that democracy's expansion has been more challenged during this period than during any similar period dating back to the 1970s. Despite this, democratic declines to this point have been considerably less severe than the more pronounced setbacks that occurred during some earlier periods in the 20th century.

Numerous broad factors may be affecting democracy globally. These include (but are not limited to) the following:

- The growing international influence of nondemocratic governments. These countries may in some instances view containing the spread of democracy as instrumental toward other goals or as helpful to their own domestic regime stability. Thus they may be engaging in various activities that have negative impacts on democracy internationally. At the same time, relatively limited evidence exists to date of a more affirmative agenda to promote authoritarian political systems or norms as competing alternatives to democracy.

- The state of democracy's global appeal as a political system. Challenges to and apparent dissatisfaction with government performance within democracies, and the concomitant emergence of economically successful authoritarian capitalist states, may be affecting in particular democracy's traditional instrumental appeal as the political system most capable of delivering economic growth and national prestige. Public opinion polling data indicate that democracy as a political system may overall still retain considerable appeal around the world relative to nondemocratic alternatives.

- Nondemocratic governments' use of new methods to repress political dissent within their own societies. Tools such as regulatory restrictions on civil society and technology-enhanced censorship and surveillance are arguably enhancing the long-term durability of nondemocratic forms of governance.

- Structural conditions in nondemocracies. Some scholars argue that broad conditions in many of the world's remaining nondemocracies, such as their level of wealth or economic inequality, are not conducive to sustained democratization. The importance of these factors to democratization is complex and contested among experts.

Democracy promotion is a longstanding, but contested, element of U.S. foreign policy. Wide disagreements and well-worn policy debates persist among experts over whether, or to what extent, the United States should prioritize democracy promotion in its foreign policy. Many of these debates concern the relevance of democracy promotion to U.S. interests, its potential tension with other foreign policy objectives, and the United States' capacity to effectively promote democratization.

Recent developments pose numerous potential policy considerations and questions for Congress. Democracy promotion has arguably not featured prominently in the Trump Administration's foreign policy to this point, creating potential continued areas of disagreement between some Members of Congress and the Administration. Simultaneously, current challenges around the world present numerous questions of potential consideration for Congress. Broadly, these include whether and where the United States should place greater or lesser emphasis on democracy promotion in its foreign policy, as well as various related questions concerning the potential tools for promoting democracy.

Introduction

For decades U.S. policymakers have connected U.S. national security and other core interests with the spread of democracy around the world. Reflecting this, the promotion of democracy has been a longstanding and multifaceted element of U.S. foreign policy, and one often interrelated with U.S. efforts to promote human rights. Congress has often played an important role in supporting and institutionalizing U.S. democracy promotion by passing key legislation, appropriating funds for foreign assistance programs and other democracy promoting activities, and conducting oversight of aspects of U.S. foreign policy relevant to democracy promotion.

Widespread concerns exist among analysts and policymakers over the current trajectory of democracy around the world and multiple hearings in the 115th Congress reflected bipartisan concern over this issue.1 For the past decade, experts have debated whether, and to what extent, the heretofore global expansion of democracy has halted or even begun to reverse. Many argue that the world has been in the midst of what has been termed a global "democratic recession" that began around 2006.2 Proponents of this view cite data from global measures of democracy as well as qualitative trends that have heightened concerns over the state of democracy, particularly in recent years. Frequently cited concerns include the rise of authoritarian populist and nationalist leaders, the potential negative influence on democracy from internationally assertive authoritarian states, questions over the enduring appeal of democracy as a political system, new tools nondemocratic governments are using to stifle potential democratizing forces, and others.

Experts vary in their assessment of the impact of these and other perceived trends and in their appraisal of what current conditions may portend for the future trajectory of democracy around the world. With regard to U.S. policy, there are disagreements over the extent to which the United States should respond to negative trends, as well as over the U.S. capacity to influence them meaningfully and effectively.

This report aims to provide Congress information, analysis, and a variety of perspectives on these issues. In particular, it provides brief conceptual background on democracy and on democracy promotion's historical role in U.S. policy, analyzes aggregate trends in the global level of democracy using data from two major democracy indexes, and discusses some of the key factors that may be broadly affecting democracy around the world. Finally, the report includes a synthesis of debates over democracy promotion in U.S. foreign policy and a selection of related policy issues and questions for Congress in the current period and beyond.

Background

Varying Definitions of Democracy

In the most basic sense, democracy means "rule by the people."3 Attempts to elaborate on this definition in ways useful to policymakers and political scientists are longstanding and contested.4 Conceptions of democracy may vary across cultural contexts and across time, and ideological biases (conscious or otherwise) as well as the broader "political zeitgeist" of the times may play a significant role in influencing what features are considered essential to the definition of democracy.5

While competing conceptions of democracy vary in numerous ways, many can be differentiated by their relative "thickness" or "thinness." Relatively "thin" definitions generally emphasize minimum elements of electoral political competition and participation, such as free and fair elections, universal suffrage, and the right to join political organizations.6 More expansive "thick" definitions may include these minimum elements as well as broad protections for individual rights and civil liberties (and corresponding constraints on government power and majority rule), the rule of law, well-functioning and transparent government institutions, and/or a democratic political culture, among other elements.7 These more expansive definitions reflect the notion that democracy consists of more than just basic elements of democratic political competition, such as elections, a contention that is now generally accepted even as the outer boundaries of the concept of democracy remain unsettled.8 Thus while minimalist, "thin" definitions may suffer criticism for excluding elements that are thought by many to be essential to democracy, broader "thick" definitions may conversely be criticized for including elements that to some are beyond the bounds of its core conception.9

Various adjectives are also frequently employed to denote different conceptions or levels of democracy. The term electoral democracy, for instance, is typically understood to align with more minimalist conceptions of democracy, while liberal democracy refers to those minimalist elements plus elements found in more expansive definitions.10 As well, while democracy is frequently understood in contrast to authoritarianism or dictatorship, many modern definitions and measures recognize that political systems often exist in middle zones, and are therefore referred to using concepts such as hybrid regimes.11 Attempts to identify political systems on a continuum of a broader spectrum of concepts in this way may nonetheless require the use of relatively arbitrary divisions between these concepts, given that, as one scholar has argued, "democracy is in many ways a continuous variable," as are many of its key elements.12

The concept of democracy is not explicitly defined in U.S. policy or law. Nonetheless, U.S. law generally implicitly aligns with nonminimalist views or notions of democracy. For example, the ADVANCE Democracy Act of 2007 (Title XXI of P.L. 110-53) associated democratic countries with eight characteristics, including some elements found in broader, "thick" definitions of democracy, such as the rule of law and various civil liberties.13 Similarly, the scope of democracy promotion programs as defined in appropriations bills includes elements such as the rule of law and labor rights.14 In line with this, unless otherwise noted, the term democracy in this report refers to broader conceptions of democracy typically associated with the term liberal democracy.

Democracy Promotion, Congress, and U.S. Policy

Encouraging the spread of democracy is a recurrent theme in U.S. foreign policy, though one that has been embraced unevenly given competing objectives and the differing foreign policy priorities and perspectives of presidential administrations. Congress has often advocated on a bipartisan basis for ensuring that support for democracy and human rights is an important component of U.S. policy, and has repeatedly taken legislative action to that effect. Beginning in the 1970s, in particular, Congress passed legislation to institutionalize support for democracy and human rights within the State Department, authorized and appropriated significant resources for democracy promotion programs (more than $2 billion annually in recent years), and sought to restrict aid to governments and to security forces responsible for gross human rights violations, among other measures.

The means by which the United States promotes democracy, broadly defined, include bilateral and multilateral diplomacy, sanctions and other forms of conditionality, foreign assistance programs, educational and cultural exchange programs, and public diplomacy and international broadcasting.15 U.S. democracy promotion also sometimes has been associated with military intervention.16 Many democracy promotion experts today draw a distinction between peaceful democracy support and democracy imposition, with military force falling into the latter category.17

The traditional rhetorical and official policy embrace of democracy promotion by U.S. policymakers (see discussion below) has not always been reflected in U.S. foreign policy activities.18 For more information on the history of U.S. democracy promotion and congressional efforts in this area, particularly relating to foreign assistance programs, see CRS Report R44858, Democracy Promotion: An Objective of U.S. Foreign Assistance, by Marian L. Lawson and Susan B. Epstein.

Identification with U.S. Strategy and Interests

For over a century, U.S. policymakers have emphasized to varying degrees a connection between the state of democracy in the world and U.S. foreign policy and national security interests. An overarching theme in drawing this connection has been a perceived relationship between peace and world order and the existence of partnerships between democracies with shared values. In one of the early articulations of this sentiment, President Woodrow Wilson in 1917 advocated for U.S. entry into World War I in part by arguing that "a steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations."19

Particularly since World War II, U.S. belief in democratic peace and stability has arguably led to democracy promotion's inclusion in a broader, though not comprehensively articulated, U.S. "grand strategy" alongside other elements such as the promotion of free trade and the creation of new international institutions.20 The efforts of the United States and its allies to construct what some refer to as the post-World War II international order were, in the words of a recent report by the RAND Corporation, "based, in part, on the assumption that no order would be sustainable if not built on a foundation of democracies with shared values," with democracy regarded "as the foundation of other core elements of the order, particularly economic growth and sustainable peace."21 International relations scholars and policymakers debate, however, the conception and historical importance of the international order within U.S. strategy and as a perceived instrument for peace and stability.22 More broadly, debates continue over whether and to what extent democracy promotion should be part of U.S. foreign policy. (See "Debates over Democracy Promotion in U.S. Foreign Policy.")

Recent Presidential Administration Policies

Recent presidential administrations of both parties have emphasized the view that democracies are more responsible international stakeholders and are more peaceful toward one another. President Bill Clinton's 1996 National Security Strategy (NSS) document, for instance, stated that "democratic states are less likely to threaten our interests and more likely to cooperate with the United States to meet security threats and promote free trade and sustainable development."23 President George W. Bush's 2006 NSS stated, "Because democracies are the most responsible members of the international system, promoting democracy is the most effective long-term measure for strengthening international stability; reducing regional conflicts; countering terrorism and terror-supporting extremism; and extending peace and prosperity."24 The Barack Obama Administration NSS documents included more general language connecting democracy promotion and U.S. interests. The 2010 NSS stated, for example, that "America's commitment to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law are essential sources of our strength and influence in the world," and that "our long-term security and prosperity depends on our steady support for universal values, which sets us apart from our enemies, adversarial governments, and many potential competitors for influence."25

All three Presidents argued for promoting democracy at times by directly invoking the logic of what has been called the democratic peace theory, or the contention that democracies are less likely to engage in armed conflict with other democracies.26 The historical relative lack of war between democracies is widely recognized by scholars, though they have debated the causes of this phenomenon and its significance.27

Trump Administration Policy

Unlike the NSS documents of previous administrations, the Trump Administration's December 2017 NSS does not articulate a general intention for the United States to actively promote democracy. The NSS does, however, include references to promoting related elements such as improved governance, anticorruption, and the rule of law, and states that the United States, "will continue to champion American values and offer encouragement to those struggling for human dignity in their societies." It also describes the United States as engaged in "political contests between those who favor repressive systems and those who favor free societies." Echoing to some degree the arguments from previous administrations, it states that "governments that respect the rights of their citizens remain the best vehicle for prosperity, human happiness, and peace," and conversely that "governments that routinely abuse the rights of their citizens do not play constructive roles in the world."28 Many argue that the Trump Administration has deemphasized democracy promotion relative to other foreign policy priorities, an issue that is discussed in the "Issues for Congress" section.

Global Trends

Measures of the State of Democracy Around the World

Numerous global indexes attempt to measure respect for democracy-related factors in nearly every country. The following discussion analyzes trends as measured by two of the most frequently cited annual indexes: Freedom House's Freedom in the World report and the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index.29 Examining the trajectory of democracy as measured by these indexes may help quantify and characterize perceived global democratic declines as well as help place them in broader historical context. Background information about the methodology of each report, information on other global indexes not analyzed in this report, and discussion of some of the general critiques of democracy indexes can be found in Appendix A.30

Freedom House's Freedom in the World Report

Freedom House's Freedom in the World country ratings are often used as a proxy measure for the level of democracy. They may correspond with relatively "thick" definitions of democracy in that they include protections for various civil liberties, the rule of law, safeguards against corruption, and other elements associated with nonminimalist definitions.31

Historical Trends

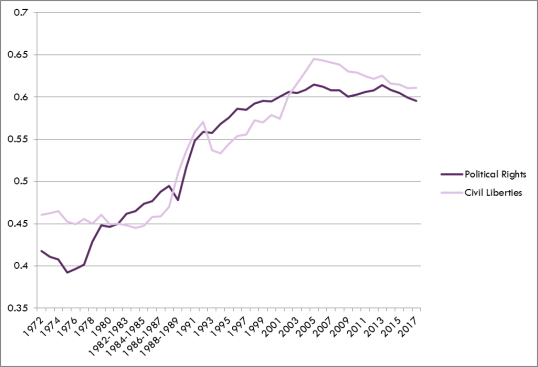

According to Freedom House's time series data, respect for political rights and civil liberties around the globe has increased substantially since the mid-1970s. Since the release of Freedom House's first report covering 1972, the combined average of global political rights and civil liberties was at its lowest point in 1975.32 By 2005, this combined measure had increased by 50% (according to CRS calculations) and stood at the highest point yet recorded.33 (See Figure 1 below.) Similarly, the percentage of countries categorized as "free" by Freedom House (as determined by their combined average of political rights and civil liberties) peaked in 2006 and 2007 at 46.63%.

From 2005 to 2017, Freedom House has recorded an overall global decline in ratings for both civil liberties and political rights, with civil liberties having declined by a greater degree (but from a higher base). According to CRS calculations, the combined global average rating of political rights and civil liberties in the Freedom House index decreased by approximately 5% from 2005 to 2017.34 In terms of freedom gains and declines on a per-country basis, Freedom House data show that countries that have gained have been outnumbered by those that have declined every year since 2006, and the gap between these figures has grown wider since 2015. In 2017, 35 countries gained while more than double that (71) declined.35

Table 1 below compares Freedom House's country statuses for the report covering 2005, with the most recent report covering 2017. As illustrated in the table, the number and percentage of countries categorized as "not free" increased in this period. In population terms, according to Freedom House, 53% of the world's population lived in either a "not free" or "partly free" country in 2005, a figure that increased to 61% in 2017.

|

Status |

Number of Countries |

Percentage of World Population |

||

|

2005 |

2017 |

2005 |

2017 |

|

|

Free |

89 (46%) |

88 (45%) |

46% |

39% |

|

Partly Free |

58 (30%) |

58 (30%) |

18% |

24% |

|

Not Free |

45 (24%) |

49 (37%) |

36% |

37% |

Source: Freedom House, "Country Status Distribution Freedom in the World 1973-2018," Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2006; Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2018.

Notes: The 2005 report measured 192 countries, while the 2017 report measured 195 countries; the 2005 report covered a slightly different timeline than the calendar year: December 1, 2004, to November 30, 2005; population percentages are as reported by Freedom House.

Trends by Subcategory

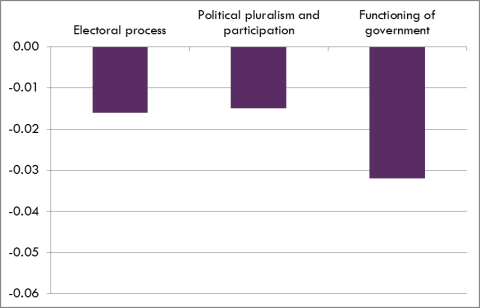

The discussion below breaks down the average global score for both political rights and civil liberties by their subcategories, as measured by Freedom House. As illustrated by Figure 2 and Figure 3, the average global score for every subcategory was lower in 2017 than it was in 2005; however, the size of these declines varied. In general, civil liberties subcategories showed greater decreases, with comparatively smaller declines in political rights subcategories.

As shown above, within the political rights category, the "functioning of government" subcategory suffered the largest decline. This subcategory includes indicators relating to the extent to which freely elected officials exercise power (as opposed to nonelected actors or nonstate groups), whether there are effective safeguards against official corruption, and the extent of government transparency. The "electoral process" and "political pluralism and participation" categories, which declined more modestly, focus on the constituent components of fair elections and free political competition, including universal suffrage, fair election laws and procedures, freedom to join political parties, and other elements.

As shown by Figure 3 above, with the exception of the "personal autonomy and individual rights" subcategory, there were larger declines in each of the civil liberties subcategories than there were in any of the political rights subcategories discussed above. This "personal autonomy and individual rights" subcategory includes indicators relating to freedom of movement, property rights, social freedoms, and equality of economic opportunity.

The "freedom of expression and belief" subcategory, which declined by the greatest degree, includes indicators on the existence of free and independent media as well as respect for religious freedom, academic freedom, and freedom of expression. The "associational and organizational rights" subcategory includes indicators relating to freedom of assembly, the free operation of nongovernmental organizations, and freedom for labor organizations. The "rule of law" subcategory includes indicators that pertain to the existence of an independent judiciary, due process, freedom from the illegitimate use of physical force (including governmental torture, war, and violent crime), and equal treatment under the law.

The Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index

The Economist Intelligence Unit's (EIU's) Democracy Index is a relatively new global democracy measure, with the first released report covering the state of democracy around the world in 2006. The report indicates both an overall democracy score for each country, which is determined by aggregating scores for five related categories, as well as a corresponding regime type categorization.36 In addition to political rights and civil liberties-related measures similar to those examined by Freedom House, EIU's index includes more emphasis on the functioning of government as well as on elements such as the level of political participation and the level of public support for democracy and democratic norms.37

Trends Since 2006

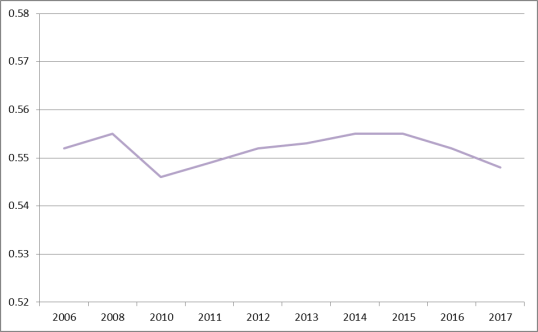

As illustrated by Figure 4 below, the global level of democracy as measured by EIU was slightly lower in 2017 than in 2006, but this decline has not been consistent or uniform. According to calculations by CRS, the global average level of democracy in 2017 was less than 1% lower than it was in 2006. Although the renewed downward trend beginning in 2015 may continue, some might characterize the broader trajectory since 2006 to this point as reflecting stagnation more than outright decline. The discrepancy in overall decline in EIU's index as compared to Freedom House's may be due to improvements in measures of political participation that are included in the EIU index but not measured by Freedom House (see discussion below).

Table 2 below compares EIU's global regime type categorizations for the report covering 2006, with the most recent report covering 2017. The data indicate a decrease in the number of "full democracies," but also a smaller decline in the number "authoritarian regimes."38 Accordingly, the two middle regime types, "flawed democracies" and "hybrid regimes," both increased in number and percentage.39

|

Regime Types |

Number of Countries |

|

|

2006 |

2017 |

|

|

Full Democracies |

26 (16%) |

19 (11%) |

|

Flawed democracies |

53 (32%) |

57 (34%) |

|

Hybrid regimes |

33 (20%) |

39 (23%) |

|

Authoritarian regimes |

55 (33%) |

52 (31%) |

Source: EIU Democracy Index 2006; EIU Democracy Index 2017.

Notes: EIU categorized a number of "borderline" countries in the 2006 index in a manner not strictly consistent with its own score thresholds; for consistency of comparison in the above figures, CRS recategorized countries according to a strict application of EIU's score thresholds.

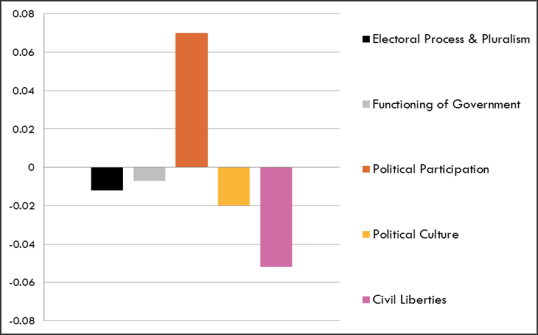

Trends by Category

The relatively modest movement at the global level in EIU's index may mask certain underlying trends. Disaggregating EIU's global average by category demonstrates that a comparatively large increase in the "political participation" category in 2017 as compared to 2006 helped balance out declines in every other category, with the "civil liberties" category particularly negatively affected (see Figure 5 below).

The "political participation" category, which increased by a larger margin than any of the other categories declined, consists of numerous quantitative indicators not included in Freedom House's index. Many of these relate to the level of political engagement by citizens, such as voter participation rates, the rate of membership in political parties, and the level of interest in politics (as captured by public opinion polls). Some might argue that these indicators and some others included in this category, such as the level of adult literacy, while conducive to a healthy democracy, are peripheral to its core definition.

EIU's "electoral process and pluralism" and "functioning of government" categories, which both declined slightly, contain many aspects in common with Freedom House's political rights category, with a focus on the elements of free and fair elections and free political participation as well as the exercise of power by elected officials, corruption, and government transparency, among other elements.40 EIU's "political culture" category, which suffered a slightly larger decline, consists of measures of the level of support for democratic (or antidemocratic) norms among the population, including the level of popular support for democracy and the level of support for "strong leaders" who bypass elections.41

Finally, EIU's "civil liberties" category decreased by the largest margin and includes numerous elements that are roughly analogous to those found in Freedom House's own civil liberties subcategories. These include indicators relating to free media and access to information, freedom of expression for individuals, associational rights, freedom from torture and the enjoyment of basic security, the independence of the judiciary, respect for religious freedom, equal treatment under the law, and others.

Thus, similar to Freedom House's data, EIU's index might be characterized as reflecting relatively smaller declines in elections and political participation aspects of democracy while registering larger declines in civil liberties-related elements. As noted, in the aggregate these declines are in part counter-balanced by improvements in the "political participation" measure, which may indicate increasing levels of democratic political engagement, broadly defined.

Interpreting the Declines

The above analysis appears to support the growing consensus that the global expansion of democracy has been halted for more than a decade. Freedom House's historical data indicates that the decline since 2005 is the most sustained setback to the gradual expansion of political rights and civil liberties since Freedom House began reporting on these measures in 1972. While declines in EIU's index have been less uniform, EIU's data also indicates that democracy has not advanced since 2006. Findings from another democracy index not analyzed here, the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem), similarly show a lack of democratic progress at the global level in recent years.42

The magnitude of actual global backsliding during this period, however, is less clear. As noted above, according to the Freedom House data, the combined global average level of political rights and civil liberties was about 5% lower in 2017 than the all-time high in 2005. According to EIU's data, the overall decline was more modest, with less than a 1% decrease in the global average level of democracy in 2017 as compared to 2006.43

These arguably modest declines are potentially more worrying for democracy proponents when examined in terms of relative population sizes. According to Freedom House, while the percentage of "free" countries decreased one percentage point from 2005 to 2017 (from 46% to 45%), the percentage of the world's population living in a "free" country declined by seven percentage points during this same period (from 46% to 39%). EIU's figures similarly indicate that the percentage of the world's population living in either a "full" or a "flawed" democracy was below 50% in 2017, with 4.5% living in the former.44 This appears to comport with findings from the aforementioned V-Dem measure, which indicate that the global level of democracy is lower when taking population size into account.45 This difference has become more pronounced in recent years because democratic declines may have disproportionately centered on countries with large populations, such as Brazil, India, and Russia, while many of the improving countries have been those with small populations such as Burkina Faso, Fiji, and Sri Lanka.46

Underlying trends in these indexes also point to some level of commonality in terms of what aspects of democracy may have seen the most pronounced declines. As the data disaggregation above illustrates, in both the Freedom House and EIU measures, the aspects of democracy relating to political competition and electoral processes appear to have suffered relatively modest declines as compared to the broader rights and institutions that are associated with well-functioning and truly "free" liberal democratic political systems, such as free and independent media, freedom of expression, freedom of association, and the rule of law.47 A potential explanation is that some governments may be inclined to focus on improving "what shows," such as elections, while neglecting or actively undermining less visible and less easily measured elements of democracy.48 This may also comport with research of longer-term trends indicating that "democratic backsliding" has over time become less overt and more incremental, consisting for instance of censorship and media restrictions, relatively subtle tactics to tilt the electoral playing field, or engineered deteriorations in judicial independence, as opposed to outright electoral fraud or blatant and sudden executive power grabs.49

Outlook and Historical Context

Despite the negative direction of these indexes in recent years, the potential implications for the longer term trajectory of democracy remain unclear. Notably, some experts have previously critiqued the accuracy of measured declines.50 More broadly, and from a longer term historical perspective, analysts have noted that significant "reverse waves" against democratic expansion have been observed in prior periods before giving way once more to continued democratization. Samuel P. Huntington famously observed two prior such "reverse waves," the first lasting from 1922 to 1945 and the second from 1960 to 1975, during which the number of democracies in the world regressed significantly before giving way to renewed democratic expansion and eventual new highs in global levels of democracy around the world.51 Experts who have warned of challenges facing democracy in this current period concede that a comparable third such "reverse wave" has not yet manifested itself.52

Those who have cautioned against excessive pessimism about the present state of democracy argue that the number of democracies in the world remains near its all-time peak, and contend that the current alarm is partly the result of an inclination to focus on certain prominent cases of perceived decline while overlooking positive news, such as improvements in certain countries in Asia and Africa (according to EIU's index).53 Nonetheless, the negative trend lines particularly in the past few years have led to yet unresolved questions over whether democratic setbacks are best characterized as "localized and transitory" or whether a more significant global reversal is underfoot.54

Factors Potentially Affecting Democracy Globally

A number of key factors that analysts believe may be affecting democracy in many countries around the world are discussed below. These broadly relevant, overarching factors may interact with relevant context-specific historical, political, social, and economic circumstances in particular regions or countries. (See Appendix B for a list of CRS reports that contain democracy-related discussions in particular contexts.)

Geopolitics and Authoritarian Power

Many observers contend that democracy's prior periods of expansion in the 20th century were due in part to the influence of the most powerful countries in the international system and their efforts to shape an international environment conducive to democracy. After World War II, the United States and other leading democracies sought to embed democratic norms within multilateral institutions, including the United Nations (U.N.), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU), and later the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), among others. Thus to a certain extent democracy was built into the operating system of the international order and was sometimes linked with security and economic benefits in a way that incentivized countries to meet democratic standards.55 Perhaps not coincidentally, the spread of democracy around the world since the mid-1970s in particular also coincided with an arguably greater emphasis on human rights and democracy in U.S. foreign policy.56 The economic dominance of the United States in this period also enhanced its cultural influence in ways that may have promoted democratization in closed societies.57

In the current period, however, the share of global income accounted for by countries rated "not free" by Freedom House has, according to one calculation, now reached over 30% (as compared to 12% in 1990).58 As these nondemocratic countries develop economically, their relative capacity to project power in their geographic neighborhoods and beyond is expected to continue to increase. If perceptions about the role of the United States and other liberal democracies in having created favorable conditions for democracy are accurate, this rising authoritarian power arguably has the potential to conversely move the international political environment in a direction less hospitable to democracy.

Democracy scholars increasingly focus on the potentially widespread negative impacts to democracy from influential and "activist" authoritarian regimes.59 The growing international assertiveness of these countries, China and Russia foremost among them, is said to be putting the leading democracies "on the defensive."60 Many U.S. policymakers had hoped that Chinese and Russian engagement with the United States and other democracies, their membership in an array of international institutions, and their economic growth from participation in the international trading system might contribute to a gradual political liberalization in both countries, but these hopes have largely not come to fruition.61 Rather, both China and Russia, according to a RAND report, "resent key elements of the U.S. conception of postwar order, such as promotion of liberal values … viewing them as tools used by the United States to sustain its hegemony."62 According to a 2017 U.S. intelligence community assessment, Russia has a "longstanding desire to undermine the US-led liberal democratic order."63 Notably, the Trump Administration's December 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) appears to emphasize some ideological aspects of U.S. competition with these countries.64

Some of the foreign policy activities of influential authoritarian countries may already be having negative impacts on democracy internationally, such as by

- attempting to undercut international support for democratic norms or related human rights norms;65

- eroding democracy's appeal by serving as examples of economically successful alternative political systems;66

- providing aid or other support that undermines democracy or the prospects for democratization in recipient countries;67

- subverting democratic institutions or norms within existing democracies through "soft" and "sharp" power projection;68 and

- actively or indirectly supporting the diffusion of techniques or tools for repressing political dissent.69

Some aspects of these challenges are discussed in the sections that follow.

Challenging the Universality of Democratic Norms

The rising international influence of authoritarian states is being accompanied to a certain extent by challenges to the idea that international norms relating to democracy and human rights are universally applicable. Although concerning for democracy proponents, the overall scope and impact of these efforts to date is unclear.

Both China and Russia in particular actively emphasize norms of state sovereignty and "noninterference" in international relations.70 Russia's emphasis on noninterference can take the form of defending respect for "traditional values." Within Russia, "traditional values" have been invoked to justify discriminatory policies against particular groups, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities. Internationally, Russia has pushed for acceptance of its "traditional values" concept within the U.N. Human Rights Council.71 Russia's restrictive policies for civil society groups operating within Russia, justified on the basis of protecting against foreign influence, have also arguably engendered replication elsewhere (see discussion in the "Modern Methods of Political Control" section).72

China's general posture is characterized by one scholar as offering "a critique of Western-style capitalism, liberal democracy and 'so-called universal values,' while presenting itself as a pragmatic, nonjudgmental partner interested only in 'win–win cooperation.'"73 China's principles of noninterference and respect for what has been termed "civilizational diversity" are said to undergird its engagement with foreign aid recipients such that this aid is largely free of governance conditions.74 Notably, according to one analysis, the top recipients of Chinese aid from 2000 to 2014 were nearly all nondemocracies.75 Principles of noninterference also appear to be manifest in China's efforts to promote the concept of "cyber sovereignty," arguably implicit within which is the notion that countries should be free to censor or otherwise control internet content within their borders.76 As with Russia, China has begun to introduce resolutions and amendments at the U.N. Human Rights Council that some researchers and human rights advocates argue aim to undermine respect for universal human rights norms.77

The multilateral Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which includes China and Russia as influential member states, also operates according to these principles of respect for sovereignty and noninterference.78 A 2006 joint statement by the SCO reads: "Diversity of civilization and model of development must be respected and upheld. Differences in cultural traditions, political and social systems, values and model[s] of development formed in the course of history should not be taken as pretexts to interfere in other countries' internal affairs."79 Although the SCO has traditionally been a regional grouping with members composed of largely authoritarian states in Central Asia, India and Pakistan joined as member states in 2017. According to some analysts, SCO's promotion of "civilizational diversity" norms may be undermining regional respect for democratic principles and having a negative impact on the democracy-related work of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).80

Promoting Authoritarianism?

Although some of their foreign policy actions may be harmful to democracy, the intentions of particular authoritarian states as they relate to democracy are complex and contested. Many authoritarian leaders are understood to be driven by a desire to maintain power and ensure regime stability, goals that are believed to influence their foreign policy decisions.81 China's focus on ensuring continued Communist Party of China (CPC) rule, for instance, may influence its foreign policy decisionmaking;82 the foreign policy actions of other influential authoritarian governments such as Russia and Iran may also be shaped by regime threat concerns.83 These defensive regime threat imperatives may manifest themselves in the foreign policy of states differently and inconsistently, and thus with varying implications for democracy. In general, to date there is more evidence that some authoritarian governments may hope to "contain" the spread of democracy because of its potential threat to their own regime stability than there is of broad, affirmative agendas to promote authoritarianism.84

Some experts contend that authoritarian states often pursue narrow economic and geopolitical interests in their foreign policies, with support for autocrats or the undermining of democracy sometimes instrumental or incidental to the pursuit of these other ends. In this argument, Russia's support for authoritarian governments, for instance, has often been opportunistic, rooted in the desire for control over energy resources or other economic or geopolitical ends. It is also limited in scope by a cultural emphasis on the "Russian world."85 Some analysts, however, assert that Russia's desire to insulate itself against potential democratic political change does color its foreign policy in ways that include an interest in influencing the regime types of its neighbors.86

China's government is said to maintain a "regime-type neutral" approach to foreign policy by which it seeks good relations with countries where it has particular interests without regard to the nature of their political systems. In the words of one analyst, China to this point has exhibited "no missionary impulse to promote authoritarianism," even as its foreign policy efforts may sometimes undermine democracy or lend prestige to authoritarian systems.87

Should their capabilities and opportunities continue to expand, it is possible that powerful nondemocracies could gradually begin to undertake more explicit and affirmative efforts to promote authoritarian political systems. Analysts have noted that the democracy promotion goals adopted by the United States and other democracies emerged over a period of time and expanded in scope and ambition concomitant with the expansion of these countries' international power and influence.88 That said, those democracy promotion efforts, in the words of one analyst, have arguably been motivated by "a clear normative commitment to democracy as a universal value," and sustained in part by genuine enthusiasm for democratic norms across many societies.89 While authoritarian political systems may increasingly hold instrumental appeal, it is not clear that affirmative formulations of "authoritarian values" could garner similar normative enthusiasm.

Notably, even the most politically repressive governments tend to continue to couch their own political systems in the language of democracy, using terms such as "socialist democracy," while maintaining elements, such as political parties and elections, that give the appearance of democracy.90 Moreover, efforts by China and Russia to promote norms of strong respect for noninterference and for differing political systems, while problematic for democracy promotion efforts, would seem to be at odds with more normatively ambitious and activist forms of authoritarianism promotion.

|

Authoritarian "Soft" and "Sharp" Power91 Analysts have expressed concern over whether the "soft power" promotion of leading authoritarian states may undermine aspects of democracy. According to Joseph S. Nye, "soft power" refers to the ability of states to achieve their goals through means of attraction and persuasion (as opposed to through coercion). The soft power efforts of authoritarian states vary widely and can take a range of forms, including investments in international media, support for educational initiatives and cultural exchange programs, foreign aid, and other types of international engagement. Because effective soft power derives in part from the energies of nongovernmental civil society, efforts by authoritarian states to a certain extent may be impaired by the tight governmental control and closed political systems of their sponsoring countries.92 Some analysts now argue that certain efforts by authoritarian states are better understood using the concept of "sharp power" in that they focus on manipulation and distraction rather than on persuasion. Some of these efforts may be characterized as defensive because they seek to bolster the image of the sponsoring country and minimize negative information, but in so doing they may show disregard for or undermine democratic norms such as free expression or academic freedom. Other activities, particularly some Russian efforts in the media space, may aim to proactively sow a corrosive general distrust toward the media and objective truth within target countries. As has been widely reported, authoritarian governments have also engaged in direct and covert political interference activities within numerous democracies, sometimes with more particular political goals. |

Challenges to Democracy's Global Appeal as a Political System

Signs of backsliding within existing democracies in recent years have led some experts to question whether the appeal and prestige of democracy as a political system itself is eroding around the globe. Although political conditions are highly contextualized within individual countries, citizens in a geographically and culturally diverse set of democracies have shown apparent willingness to "cast votes in large numbers for candidates whose commitment to liberal democracy was highly questionable."93 Arguably authoritarian or authoritarian-leaning leaders are currently in power or have previously been elected in countries as varied as Venezuela, Turkey, the Philippines, and Peru. Aspects of liberal democracy such as respect for individual rights, freedom of the press, and the rule of law have come under particular attack in many countries.

Within Western democracies such as Hungary and Poland, leaders and political parties who hold views contrary to democratic norms have also achieved electoral success. Notably, Hungary's Viktor Orbán, who was overwhelmingly elected in April 2018 to a third consecutive term as prime minister, has spoken of constructing an "illiberal state," a project alleged by critics to entail hollowing out pluralism and ensuring the dominance of the ruling party over the long term.94

Political scientists have traditionally viewed countries that have reached a certain level of wealth and have experienced peaceful democratic political transitions as being stable, "consolidated" democracies largely impervious to backsliding into nondemocratic forms of government. Arguably weakening support for democracy within some long-established democracies, however, has spurred an emerging and highly contested debate over whether democratic "deconsolidation" is more possible than previously believed.95

|

Populism and Nationalism96 Many observers have expressed concern in recent years over the potential threat to democracy from populist and nationalist political parties and candidates, which have emerged within both new and old democracies in various regions. Analysts concerned over these trends point to examples of democratic erosion in countries such as Hungary and Venezuela, where nationalist and populist leaders, once elected, have sought to subvert not just aspects of liberal democracy but arguably also core elements of free and fair democratic political competition. While acknowledging the genuine threat of some of these movements to democracy, some analysts have warned against overgeneralizing populist or nationalist movements, noting that even within the same region these movements can arise as a result of different circumstances in each country. Moreover, they contend that not every such movement is necessarily threatening to democracy, and may center on legitimate policy debates. Some research and commentary has connected aspects of rising populism and nationalism in the West in particular to events such as the 2008 financial crisis or, more recently, refugee in-flows. Other research indicates, however, that populist parties in Europe have been gradually rising in popularity for decades, suggesting also longer-term factors. |

Democracy's Instrumental Appeal

Support for democracy around the world may rest on a combination of its intrinsic and its instrumental appeal. Whereas democracy's intrinsic appeal is rooted in personal and political freedoms, its instrumental appeal is associated with perceived positive outputs resulting from democratic governance, such as economic growth and national prestige. Some analysts assert that particularly after the end of the Cold War, many countries pursued democratizing political reforms at least in part because democracy was seen as the only viable pathway to high economic growth, modernity, and national prestige. As discussed above, democratization was also associated with membership in international institutions that provided instrumental economic and security benefits.97

If traditionally high levels of support for democracy around the world have related at least in part to its instrumental appeal, then challenges within democracies in recent years (including within the United States) may be eroding support for democracy as a political system. According to the U.S. intelligence community, some of these challenges include poor governance, economic inequality, and "weak national political institutions."98 Many challenges facing newer democracies in particular may relate to difficulties in establishing modern states capable of providing services in line with the demands of their citizens.99 The connection between democracy and attainment of the economic and security rewards of certain international institutions may also be loosening. Apparent democratic backsliding among some member states in the EU (such as Hungary and Poland) and NATO (such as Turkey) have called into question the ability and inclination of these institutions to enforce democratic standards for countries that have already acceded to membership.100

Relatedly, a class of economically successful authoritarian capitalist states has emerged. To the extent that these countries, China foremost among them, are able to continue to grow at high rates while forestalling political liberalization, they may gradually be undermining the appeal of democracy as a political system by disconnecting it from its perceived association with economic success, modernity, and prestige.101 Recent statements by Xi Jinping have led some observers to assert that China is now openly embracing this role.102 In October 2017, Xi stated that China's model of "socialism with Chinese characteristics" could serve as a "new choice" for countries hoping to speed up their development and preserve their independence.103 Xi later stated, however, that China will not "export" its political model or ask that other countries copy China's methods.104

The U.S. Example105

Many believe that democracy's appeal around the world has historically been enhanced by the capacity of the United States to serve as an attractive example. In recent years, some Members of Congress and others have argued that challenges in the U.S. political system are hampering the United States' ability to effectively project democratic values abroad. Experts point to problems such as polarization and polarizing rhetoric, institutional gridlock, and eroding respect for democratic norms as potentially undermining U.S. democracy promotion efforts. According to Freedom House, the United States has suffered a "slow decline" in political rights and civil liberties for several years, a deterioration that it says "accelerated" in 2017. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) for the first time categorized the United States as a "flawed democracy" in its report covering 2017 (although, as noted earlier in this report, its score narrowly missed continued categorization as a "full democracy" according to EIU).

Measures of Support for Democracy106

Perhaps reflecting some of the dynamics discussed above, a Pew Research Center report summarizing 2017 polling data across a set of 38 geographically and economically diverse countries found mixed attitudes about the performance of democracy. Nonetheless, the same report indicated that support for democracy as a political system remains high, with support far exceeding most nondemocratic alternatives. A median of 78% of respondents approved of representative democracy, while more than 70% disapproved of either rule by a "strong leader" or rule by the military. The only nondemocratic alternative to garner plurality approval was "rule by experts." (See Figure 6 below.) Approximately 23% of respondents expressed support for representative democracy and rejected all three nondemocratic alternatives posed. Pew found that the proportion of these "committed democrats" in a country was correlated with its level of wealth as well as its level of democracy as measured by EIU, suggesting that support for democracy is highest within richer and more democratic countries.107

Beyond this broad snapshot, analyses of polling data measuring support for democracy over time and within individual countries does not appear to demonstrate a single, clear overall global negative trend. For instance, an analysis sought to gauge the trajectory of support for democracy across 134 countries since 1990 by statistically aggregating data from a large number of polls. The findings indicated that baseline levels of support for democracy differed between established democracies, new democracies, and nondemocracies (with levels of support generally highest within established democracies), but that recent trend-lines across each type varied across countries and regions. Some countries exhibited a distinct downward trajectory of support in recent years, while others showed marked increases during the same period. Many countries showed relatively stable levels of support.108

This mixed picture is also reflected in trends within regional polls. For instance, according to a 2014-2015 poll of 34 African countries, since 2012 support for democracy had increased in 10 countries, decreased in 14 countries, and had no statistically significant change in 10 countries.109 Among nine countries in the Middle East and North Africa region, polling data comparing levels of support for democracy in 2010-2011 versus 2012-2014 shows that support remained essentially unchanged in five countries, decreased in two countries, and increased in two countries.110 Within Latin America, although there have been considerable changes in levels of support within particular countries, the aggregate level of support across the region has reportedly remained largely unchanged since 1995.111

These varied trend-lines are perhaps unsurprising given the myriad distinct political, social, and economic contexts and developments within countries around the globe. Nonetheless, they may also indicate that support for democracy as a political system, at least among general publics, is not eroding to the degree that many democracy proponents fear. Rather, to the extent that public opinion polling is a reliable indicator (see text box below), support overall appears resilient to this point. This may buttress the claim, as articulated by one scholar, that "democracy may be receding in practice, but it is still ascendant in peoples' values and aspirations … few people in the world today celebrate authoritarianism as a superior moral system … [or] the best form of government."112

|

Limitations and Caveats Around Measuring Support for Democracy113 Public opinion polling is one of the few concrete means for measuring support for democracy among average citizens around the world. Nonetheless, there are various potential shortcomings and response biases associated with polls that attempt to measure support for democracy, as well as wide disagreements over how to interpret polling data. For instance, the concept of democracy may mean different things to different people across time and cultural contexts. Along these lines, some argue that there have been generational shifts in conceptions of democracy, making long-term time series data difficult to compare. Another example of potential response bias is that positive connotations around the concept of democracy may create social pressure for respondents to overstate their level of support. Respondents in authoritarian political systems may also exhibit self-censorship. Finally, the relationship between attitudes toward democracy and the stability (or lack thereof) of democracies is not necessarily straightforward. |

Modern Methods of Political Control

In addition to concerns over their international influence, nondemocracies are also using new and sophisticated tools to forestall the potential formation of democratizing forces within their own societies. Many of these modern tools may be less heavy-handed, and thus less likely to engender societal backlash, than traditional forms of repression. They may also be less resource intensive. These methods, some of which are discussed below, are thus potentially contributing to more durable forms of nondemocratic governance.114

Civil Society Restrictions115

Civil society organizations (CSOs), which are often viewed as an important component of sustainable democracy, are confronting growing limitations on their ability to operate around the world.116 From restrictions on the types of funding they are allowed to receive to stringent registration requirements, the measures targeting CSOs are increasingly putting pressure on the entire civil society sector in certain countries.117 These restrictions are most commonly, but not exclusively, imposed by authoritarian and hybrid regimes seeking to limit the influence of nongovernmental actors. This phenomenon is commonly referred to by researchers and advocates as the "closing space" for civil society work around the world.118

The origins of the closing space phenomenon vary and are often country-specific. That said, scholars have pointed to several factors that have contributed to the spread of civil society restrictions. After the end of the Cold War era, Western governments, including the United States, substantially increased funding for pro-democracy CSOs. Concurrently, a number of events caused some governments to view the civil society sector warily, including the color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, the later Arab Spring movements, and others.119 Publicly, many states have sought to justify civil society restrictions on national security and counterterrorism grounds; critics argue that such measures are merely pretexts for cracking down on certain civil society sectors or activities.120 Some countries have also justified civil society restrictions, particularly those concerning foreign funding, on the basis of sovereignty.121

Experts cite Russia's suppression of civil society in particular as a model that other states may have sought to emulate.122 Russian government measures restricting civil society have included requiring groups that receive foreign funding and engage in "political activity," broadly defined, to register as foreign agents. Later measures granted the Russian government the authority to unilaterally declare a CSO a foreign agent, as well as the discretion to shut down or limit the activities of CSOs deemed a threat to national security.123

A broad range of other governments have imposed similar restrictions on civil society. According to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), between 2012 and 2015, 60 countries enacted a total of over 120 laws to constrain the freedom of association or assembly (see Figure 7 below).124 In some cases, restrictions render the structure, funding streams, or activities of CSOs illegal or otherwise impossible to sustain, forcing organizations to cease operations. CSOs that depend on foreign funding or staff are particularly vulnerable, as are those that focus on social or political issues that can be deemed subversive or threatening to national interests pursuant to vaguely written laws.125 In other cases, governments initiate investigations or legal proceedings against CSOs for alleged violations of laws related to CSO registration, funding, or activities. Such cases may be intended to drain CSOs of resources and/or to intimidate other groups into compliance.126

Technological Tools127

Optimism about the potential democratizing power of new information technologies, the internet, and social media has been tempered in recent years as nondemocratic governments have grown more adept at using technological means to censor, monitor, distort, or otherwise repress potential social and political opposition.128 In general, many emerging technologies are perhaps best understood as "dual use" in the sense that, depending on how they are utilized, they have the potential for both positive and negative impacts on democracy. Authoritarian governments appear to have shown an ability to mitigate many of the politically threatening aspects of these new technologies, and over time may increasingly have the capacity to actively leverage them in service of social and political control.

Efforts to restrict free expression online have accelerated in some countries since the aforementioned color revolutions and the Arab Spring movements, which saw activists and citizens share information and organize mass protests via social media in an unprecedented fashion.129 According to Freedom House, internet freedom restrictions can be divided into three main categories: obstacles to access, limits on content, and violations of user rights.130 Obstacles to access may relate to poor infrastructure or high costs, but also to blanket and deliberate outages, such as during politically sensitive periods or in politically sensitive areas. Content limitations consist of proactive efforts to shape the information environment online such as through technical filters or censors to block websites and/or certain content.131 In some cases, governments may also use forms of offline punishment such as criminal or extralegal detention to deter individuals from engaging in certain online speech or political organizing.132 Relatedly, government-sponsored cyberattacks on media outlets, opposition leaders, and activists are also reportedly on the rise.133

Increasingly, government efforts also extend to active manipulation of online discourse through automated bots or paid commentators, which artificially spread pro-government messages or use misinformation to distract or confuse online audiences, thereby "drowning out" the online speech of individuals seen as threatening to the government.134 According to the U.S. intelligence community, the use of these tactics by governments around the world has "increased dramatically in the past 10 years."135

Human rights organizations argue that well-resourced and technologically advanced authoritarian states are also developing and deploying advanced technologies to more comprehensively track the online and offline activities of their citizens in ways that may be aimed, at least in part, at anticipating and repressing sources of political dissent. China's efforts are foremost among these and include facial recognition-enhanced public surveillance and the use of "big data" information collection and aggregation technologies.136 These and other emerging technologies may increasingly use efficient and scalable forms of artificial intelligence (AI) that could lower the costs required for maintaining social control.137

Although the most advanced of these technologies are being developed in a small number of countries, they may increasingly spread to other governments over time. Analysts have noted, for instance, reports of Chinese-developed facial recognition technologies having already been marketed and sold to some foreign government customers.138

Structural Conditions

Some analysts contend that the lack of global democratic expansion in recent years, and its arguably modest backsliding, is rooted in unfavorable conditions for democratization in many of the world's remaining nondemocracies. These arguments draw on academic research indicating that structural conditions such as wealth, international linkages, and levels of inequality may have considerable impact on a country's likelihood of sustained democratization. Thus, according to some analysts, challenges in the current period are not particularly surprising, and might be expected to continue, because "nearly every country with minimally favorable conditions for democracy" had already democratized by the mid-2000s.139

These arguments may be buttressed by the fact that many factors that were previously understood by scholars to support democratization are increasingly believed to have more ambiguous effects. Increasing levels of wealth, for instance, may not be as closely associated with democratization as previously believed, and may contribute to regime stability for democracies and some authoritarian states alike.140 Relatedly, the relationship between state capacity and democracy is complex and, according to some experts, not necessarily mutually supportive.141 Within authoritarian regimes, strong state capacity may help forestall democratization by enhancing what scholars call "performance legitimacy" through the government's ability to provide valued public goods, as well as its capacity to monitor and respond to dissent.142 Some research also supports what has been referred to as the "oil curse," or the notion that countries with natural resource wealth are less likely to democratize. This may be because their governments can use abundant revenues from these resources to similarly undercut societal demands for democracy (among other theorized causal factors).143

How much any of these or other factors alone or together may affect the prospects for democratization in a given country is a complex and contested question. Experts who have emphasized these factors as helping to explain the challenges to democracy in the current period concede that favorable conditions are not always necessary for democratization, but contend that they are causally important.144 Some analysts argue against excessive emphasis on these conditions and point to prior examples of democratization in countries where the scholarship would indicate this to be unlikely.145

Debates over Democracy Promotion in U.S. Foreign Policy

Rationales for U.S. democracy promotion are varied. As noted, U.S. leaders have long drawn links between the state of global democracy and U.S. national security and economic interests. In addition, Members of Congress and others have sometimes asserted that the United States has a moral obligation to promote democracy and human rights, and some scholars argue that an inclination within U.S. foreign policy for "values promotion" derives from fundamental aspects of American political culture.146 Nonetheless, analysts continue to debate the extent to which the United States should promote democracy and what the proper balance of emphasis is between this objective and other foreign policy priorities. Some have questioned the appropriateness of democracy promotion at a basic level, such as by asserting that it constitutes an imposition of American values on other societies. There are also debates over whether these efforts constitute violations of sovereignty or improper interference in the politics of other countries.147 Supporters of democracy promotion have defended these activities as legitimate and generally argue that aspirations for, and values reflecting, democratic freedoms are universal.148

More broadly, many disagreements over the proper placement of democracy promotion within U.S. foreign policy tend to relate to the extent to which democracy promotion is seen as supportive of U.S. national interests, the extent of its potential tension with the pursuit of other objectives, and whether the United States has the means and capacity over the long-term to effectively support the spread of democracy and prevent backsliding. These thematic trends are summarized below.

Relationship to U.S. Interests

Scholars, democracy promotion advocates, and U.S. policymakers have associated the spread of democracy around the world with U.S. interests in various ways. As noted earlier, the rationale for democracy promotion has rested on the contention that democracies are generally more reliable and trustworthy international partners of the United States, and on the argument that democracies are considerably less likely to go to war with one another. Regarding the former argument, some argue that democratic transparency may make democracies particularly conducive to supporting the international agreements and institutions that populate the current international order.149 Accordingly, many believe that greater numbers of democracies supports the resilience of this order, which has arguably brought myriad economic and security benefits to the United States. Scholars continue to debate, however, the order's importance as compared to traditional relative power dynamics between countries.150