Cuba: U.S. Policy in the 115th Congress

Cuba remains a one-party authoritarian state with a poor human rights record. Current President Miguel Díaz-Canel succeeded Raúl Castro in April 2018, although Castro is continuing as first secretary of Cuba’s Communist Party. Over the past decade, Cuba has implemented gradual market-oriented economic policy changes, but critics maintain that it has not taken enough action to foster sustainable economic growth. Most observers do not anticipate major policy changes under Díaz-Canel, at least in the short term; the president faces the enormous challenges of reforming the economy and responding to desires for greater freedom.

U.S. Policy

Congress has played an active role in shaping policy toward Cuba, including the enactment of legislation strengthening and at times easing U.S. economic sanctions. Since the early 1960s, the centerpiece of U.S. policy has consisted of economic sanctions aimed at isolating the Cuban government. In 2014, however, the Obama Administration initiated a major policy shift, moving away from sanctions toward a policy of engagement. The policy change included the restoration of diplomatic relations (July 2015); the rescission of Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of international terrorism (May 2015); and an increase in travel, commerce, and the flow of information to Cuba implemented through regulatory changes.

In June 2017, President Trump unveiled a new policy toward Cuba that increased sanctions and partially rolled back some of the Obama Administration’s efforts to normalize relations. The most significant changes include restrictions on transactions with companies controlled by the Cuban military and the elimination of individual people-to-people travel. In response to unexplained injuries of members of the U.S. diplomatic community at the U.S. Embassy in Havana, the State Department reduced the staff of the U.S. Embassy by about two-thirds; the reduction has affected embassy operations, especially visa processing, and made bilateral engagement more difficult.

Legislative Activity

In the 115th Congress, debate over Cuba policy continued, especially with regard to economic sanctions. The 2018 farm bill, P.L. 115-334 (H.R. 2), enacted in December 2018, has a provision permitting funding for two U.S. agricultural export promotion programs in Cuba. Two FY2019 House appropriations bills, Commerce (H.R. 5952) and Financial Services (H.R. 6258 and H.R. 6147), had provisions that would have tightened economic sanctions, but final action was not completed by the end of the 115th Congress. Other bills were introduced, but not acted upon, that would have eased or lifted sanctions altogether: H.R. 351 and S. 1287 (travel); H.R. 442/S. 472 and S. 1286 (some economic sanctions); H.R. 498 (telecommunications); H.R. 525 (agricultural exports and investment); H.R. 572 (agricultural and medical exports and travel); H.R. 574, H.R. 2966, and S. 1699 (overall embargo); and S. 275 (private financing for U.S. agricultural exports).

Congress continued to provide funding for democracy and human rights assistance in Cuba and for U.S.-government sponsored broadcasting. For FY2017, Congress provided $20 million in democracy assistance and $28.1 million for Cuba broadcasting (P.L. 115-31). For FY2018, it provided $20 million for democracy assistance and $28.9 million for Cuba broadcasting (P.L. 115-141; explanatory statement to H.R. 1625). For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested $10 million in democracy assistance and $13.7 million for Cuba broadcasting. The House Appropriations Committee’s FY2019 State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations bill, H.R. 6385, would have provided $30 million for democracy programs, whereas the Senate version, S. 3108, would have provided $15 million; both bills would have provided $29 million for broadcasting. The 115th Congress approved a series of continuing resolutions (P.L. 115-245 and P.L. 115-298 ) that continued FY2019 funding at FY2018 levels through December 21, 2018, but did not complete action on FY2019 appropriations, leaving the task to the 116th Congress.

In other action, several approved measures—P.L. 115-232, P.L. 115-244, and P.L. 115-245—have provisions extending a prohibition on FY2019 funding to close or relinquish control of the U.S. Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; the conference report to P.L. 115-232 also requires a report on security cooperation between Russia and Cuba. The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-254) requires the Transportation Security Administration to brief Congress on certain aspects of Cuban airport security and efforts to better track public air charter flights between the United States and Cuba. In April 2018, the Senate approved S.Res. 224, commemorating the legacy of Cuban democracy activist Oswaldo Payá. For more on legislative initiatives in the 115th Congress, see Appendix A.

Cuba: U.S. Policy in the 115th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Recent Developments

- Introduction

- Cuba's Political and Economic Environment

- Brief Historical Background

- Political Conditions

- Cuba's Transition to a New President

- Human Rights

- Economic Conditions

- Cuba's Foreign Relations

- U.S. Policy Toward Cuba

- Background on U.S.-Cuban Relations

- Obama Administration Policy

- Shift Toward Normalizing Relations

- Trump Administration Policy

- Partial Rollback of Engagement and Increased Sanctions

- Continued Focus on Human Rights

- Continued Engagement in Some Areas

- U.S. Response to Injuries of U.S. Personnel in Havana

- Debate on the Direction of U.S. Policy

- Selected Issues in U.S.-Cuban Relations

- U.S. Travel to Cuba

- U.S. Exports and Sanctions

- Trademark Sanction

- Democracy and Human Rights Funding

- Radio and TV Martí

- Migration Issues

- Antidrug Cooperation

- U.S. Property Claims

- U.S. Fugitives from Justice

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Cuba remains a one-party authoritarian state with a poor human rights record. Current President Miguel Díaz-Canel succeeded Raúl Castro in April 2018, although Castro is continuing as first secretary of Cuba's Communist Party. Over the past decade, Cuba has implemented gradual market-oriented economic policy changes, but critics maintain that it has not taken enough action to foster sustainable economic growth. Most observers do not anticipate major policy changes under Díaz-Canel, at least in the short term; the president faces the enormous challenges of reforming the economy and responding to desires for greater freedom.

U.S. Policy

Congress has played an active role in shaping policy toward Cuba, including the enactment of legislation strengthening and at times easing U.S. economic sanctions. Since the early 1960s, the centerpiece of U.S. policy has consisted of economic sanctions aimed at isolating the Cuban government. In 2014, however, the Obama Administration initiated a major policy shift, moving away from sanctions toward a policy of engagement. The policy change included the restoration of diplomatic relations (July 2015); the rescission of Cuba's designation as a state sponsor of international terrorism (May 2015); and an increase in travel, commerce, and the flow of information to Cuba implemented through regulatory changes.

In June 2017, President Trump unveiled a new policy toward Cuba that increased sanctions and partially rolled back some of the Obama Administration's efforts to normalize relations. The most significant changes include restrictions on transactions with companies controlled by the Cuban military and the elimination of individual people-to-people travel. In response to unexplained injuries of members of the U.S. diplomatic community at the U.S. Embassy in Havana, the State Department reduced the staff of the U.S. Embassy by about two-thirds; the reduction has affected embassy operations, especially visa processing, and made bilateral engagement more difficult.

Legislative Activity

In the 115th Congress, debate over Cuba policy continued, especially with regard to economic sanctions. The 2018 farm bill, P.L. 115-334 (H.R. 2), enacted in December 2018, has a provision permitting funding for two U.S. agricultural export promotion programs in Cuba. Two FY2019 House appropriations bills, Commerce (H.R. 5952) and Financial Services (H.R. 6258 and H.R. 6147), had provisions that would have tightened economic sanctions, but final action was not completed by the end of the 115th Congress. Other bills were introduced, but not acted upon, that would have eased or lifted sanctions altogether: H.R. 351 and S. 1287 (travel); H.R. 442/S. 472 and S. 1286 (some economic sanctions); H.R. 498 (telecommunications); H.R. 525 (agricultural exports and investment); H.R. 572 (agricultural and medical exports and travel); H.R. 574, H.R. 2966, and S. 1699 (overall embargo); and S. 275 (private financing for U.S. agricultural exports).

Congress continued to provide funding for democracy and human rights assistance in Cuba and for U.S.-government sponsored broadcasting. For FY2017, Congress provided $20 million in democracy assistance and $28.1 million for Cuba broadcasting (P.L. 115-31). For FY2018, it provided $20 million for democracy assistance and $28.9 million for Cuba broadcasting (P.L. 115-141; explanatory statement to H.R. 1625). For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested $10 million in democracy assistance and $13.7 million for Cuba broadcasting. The House Appropriations Committee's FY2019 State Department and Foreign Operations appropriations bill, H.R. 6385, would have provided $30 million for democracy programs, whereas the Senate version, S. 3108, would have provided $15 million; both bills would have provided $29 million for broadcasting. The 115th Congress approved a series of continuing resolutions (P.L. 115-245 and P.L. 115-298 ) that continued FY2019 funding at FY2018 levels through December 21, 2018, but did not complete action on FY2019 appropriations, leaving the task to the 116th Congress.

In other action, several approved measures—P.L. 115-232, P.L. 115-244, and P.L. 115-245—have provisions extending a prohibition on FY2019 funding to close or relinquish control of the U.S. Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; the conference report to P.L. 115-232 also requires a report on security cooperation between Russia and Cuba. The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-254) requires the Transportation Security Administration to brief Congress on certain aspects of Cuban airport security and efforts to better track public air charter flights between the United States and Cuba. In April 2018, the Senate approved S.Res. 224, commemorating the legacy of Cuban democracy activist Oswaldo Payá. For more on legislative initiatives in the 115th Congress, see Appendix A.

Recent Developments

On January 2, 2019, for the second year in a row, the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN) reported a significant decline in the annual number of short-term detentions for political reasons. In 2018, according to the CCDHRN, there were 2,873 short-term detentions, almost a 45% decline from 2017 and the lowest level since 2010. (See "Human Rights," below.)

On December 22, 2018, Cuba's National Assembly approved a draft constitution that will be subject to a national referendum planned for February 24, 2019. Due to public opposition orchestrated by religious groups, the draft eliminated a provision that eventually could have led to approval of same-sex marriage and instead remained silent on defining matrimony. (See discussion on constitutional changes in "Cuba's Transition to a New President," below.)

On December 20, 2018, President Trump signed into law the 2018 farm bill, P.L. 115-334 (H.R. 2), with a provision that permits funding for two export promotion programs—the Market Access Program and the Foreign Market Development Cooperation Program—for U.S. agricultural products in Cuba. (See "U.S. Exports and Sanctions," below.)

On December 19, 2018, Major League Baseball announced it had reached an agreement with the Cuban Baseball Federation to allow baseball players from Cuba to sign contracts without defecting from Cuba. Some press reports indicate that the Trump Administration might take action to prevent the deal from moving forward.

On November 15, 2018, the Trump Administration updated its list of restricted Cuban entities controlled by the Cuban military, intelligence, or security services or personnel with which direct financial transactions would disproportionately benefit those services or personnel at the expense of the Cuban people or private enterprise in Cuba. Currently, there are 205 entities on the list, including 99 hotels. (See "Partial Rollback of Engagement and Increased Sanctions," below.)

On November 1, 2018, National Security Adviser John Bolton made a speech in Miami, FL, strongly criticizing the Cuban government on human rights. In a press interview, Bolton also maintained that the Administration was considering whether to continue to suspend Title III of the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996 (LIBERTAD Act; P.L. 104-114) to allow lawsuits in U.S. federal court against those "trafficking" in confiscated property in Cuba, an action that would significantly ratchet up U.S. sanctions on Cuba. (For more on Title III, see "U.S. Property Claims," below.)

On November 1, 2018, the United Nations General Assembly approved a resolution (as it has annually since 1991) opposing the U.S. embargo on Cuba. The vote was 189-2, with Israel joining the United States in opposing it. The United States also proposed eight amendments to the resolution criticizing Cuba's human rights record, but all these amendments were defeated by wide margins. (See "Cuba's Foreign Relations," below.)

On October 26, 2018, U.S. media reports highlighted a disturbing TV Martí program originally aired in May 2018 that disparaged U.S. businessman George Soros through anti-Semitic language and unfounded conspiracy theories. Subsequently, the Office of Cuba Broadcasting pulled the program from its website and the chief executive officer of the U.S. Agency for Global Media stated that the program was "inconsistent with our professional standards and ethics." (See "Radio and TV Martí," below.)

On October 16, 2018, the State Department's U.S. Mission to the United Nations launched a campaign to call attention to Cuba's estimated 130 political prisoners. (See "Human Rights," below.)

On October 15, 2018, the Cuban government released Cuban political opposition activist Tomás Núñez Magdariaga from prison after a 62-day hunger strike. The State Department had called for his release, maintaining that he was imprisoned on false charges and convicted in a sham trial. (See "Human Rights," below.)

On October 6, 2018, President Trump signed into law the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-254) with a provision requiring the Transportation Security Administration to brief Congress on certain aspects of Cuban airport security, develop and implement a mechanism to better track public air charter flights between the United States and Cuba, and direct public air charters to provide updated data on such flights. (See "U.S. Travel to Cuba," below.)

Introduction

Political and economic developments in Cuba and U.S. policy toward the island nation, located just 90 miles from the United States, have been significant congressional concerns for many years. Especially since the end of the Cold War, Congress has played an active role in shaping U.S. policy toward Cuba, first with the enactment of the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 (CDA; P.L. 102-484, Title XVII) and then with the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-114). Both measures strengthened U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba that had first been imposed in the early 1960s but also provided road maps for a normalization of relations, dependent upon significant political and economic changes in Cuba. Congress partially modified its sanctions-based policy toward Cuba when it enacted the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (TSRA; P.L. 106-387, Title IX) allowing for U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba.

|

Cuba at a Glance Population: 11.2 million (2016, ONEI) Area: 42,426 square miles (ONEI), slightly smaller than Pennsylvania GDP: $96.9 billion (2017, nominal U.S. $, EIU est.) Real GDP Growth: 0.5% (2016); 1.8% (2017, EIU est.) Key Trading Partners: Exports (2017): Canada, 19.4%; Venezuela, 15.6%; China, 15.2%; Spain 8.6%. Imports (2017): Venezuela, 18.1%; China, 16.3%; Spain, 10.8%. (ONEI) Life Expectancy: 79.6 years (2015, UNDP) Literacy (adult): 99.7% (2015, UNDP) Legislature: National Assembly of People's Power, currently 605 members (five-year terms elected in March 2018). Sources: National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI), Republic of Cuba; U.N. Development Programme (UNDP); Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). |

Over the past decade, much of the debate in Congress over U.S. policy has focused on U.S. sanctions. In 2009, Congress took legislative action in an appropriations measure (P.L. 111-8) to ease restrictions on family travel and travel for the marketing of agricultural exports, marking the first congressional action easing Cuba sanctions in almost a decade. The Obama Administration took further action in 2009 by lifting all restrictions on family travel and on cash remittances by family members to their relatives in Cuba. In 2011, the Obama Administration announced the further easing of restrictions on educational and religious travel to Cuba and on donative remittances to other than family members.

In December 2014, just after the adjournment of the 113th Congress, President Obama announced a major shift in U.S. policy toward Cuba, moving away from a sanctions-based policy aimed at isolating Cuba toward a policy of engagement and a normalization of relations. The policy shift led to the restoration of diplomatic relations, the rescission of Cuba's designation as a state sponsor of international terrorism, and the easing of some restrictions on travel and commerce with Cuba. There was mixed reaction in Congress, with some Members of Congress supporting the change and others opposing it. Legislative initiatives in the 114th Congress reflected this policy divide, with some bills introduced that would have further eased U.S. economic sanctions and others that would have blocked the policy shift and introduced new sanctions.

This report examines U.S. policy toward Cuba in the 115th Congress. It is divided into three major sections analyzing Cuba's political and economic environment; U.S. policy toward Cuba; and selected issues in U.S.-Cuban relations, including restrictions on travel and trade, funding for democracy and human rights projects in Cuba and for U.S. government-sponsored radio and television broadcasting, migration, antidrug cooperation, U.S. property claims, and U.S. fugitives from justice in Cuba. Legislative initiatives in the 115th Congress are noted throughout the report, and Appendix A lists enacted measures and other bills and resolutions. Appendix B provides links to U.S. government information and reports on Cuba. For more on Cuba from CRS, see

- CRS In Focus IF10045, Cuba: U.S. Policy Overview, by Mark P. Sullivan;

- CRS Report R43888, Cuba Sanctions: Legislative Restrictions Limiting the Normalization of Relations, by Dianne E. Rennack and Mark P. Sullivan;

- CRS Report RL31139, Cuba: U.S. Restrictions on Travel and Remittances, by Mark P. Sullivan;

- CRS Insight IN10798, U.S. Response to Injuries of U.S. Embassy Personnel in Havana, Cuba, by Mark P. Sullivan and Cory R. Gill;

- CRS Insight IN10788, Hurricanes Irma and Maria: Impact on Caribbean Countries and Foreign Territories, by Mark P. Sullivan;

- CRS Insight IN10722, Cuba: President Trump Partially Rolls Back Obama Engagement Policy, by Mark P. Sullivan;

- CRS Report R44119, U.S. Agricultural Trade with Cuba: Current Limitations and Future Prospects, by Mark A. McMinimy;

- CRS Report R44137, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues Regarding Its Lease Agreements, by Jennifer K. Elsea and Daniel H. Else; and

- CRS Report R44714, U.S. Policy on Cuban Migrants: In Brief, by Andorra Bruno.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Cuba's Political and Economic Environment

Brief Historical Background1

Cuba became an independent nation in 1902. From its discovery by Columbus in 1492 until the Spanish-American War in 1898, Cuba was a Spanish colony. In the 19th century, the country became a major sugar producer, with slaves from Africa arriving in increasing numbers to work the sugar plantations. The drive for independence from Spain grew stronger in the second half of the 19th century, but independence came about only after the United States entered the conflict, when the USS Maine sank in Havana Harbor after an explosion of undetermined origin. In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the United States ruled Cuba for four years until Cuba was granted its independence in 1902. Nevertheless, the United States retained the right to intervene in Cuba to preserve Cuban independence and maintain stability in accordance with the Platt Amendment,2 which became part of the Cuban Constitution of 1901. The United States subsequently intervened militarily three times between 1906 and 1921 to restore order, but in 1934, the Platt Amendment was repealed.

Cuba's political system as an independent nation often was dominated by authoritarian figures. Gerardo Machado (1925-1933), who served two terms as president, became increasingly dictatorial until he was ousted by the military. A short-lived reformist government gave way to a series of governments that were dominated behind the scenes by military leader Fulgencio Batista until he was elected president in 1940. Batista was voted out of office in 1944 and was followed by two successive presidents in a democratic era that ultimately became characterized by corruption and increasing political violence. Batista seized power in a bloodless coup in 1952, and his rule progressed into a brutal dictatorship that fueled popular unrest and set the stage for Fidel Castro's rise to power.

Castro led an unsuccessful attack on military barracks in Santiago, Cuba, on July 26, 1953. He was jailed but subsequently freed. He went into exile in Mexico, where he formed the 26th of July Movement. Castro returned to Cuba in 1956 with the goal of overthrowing the Batista dictatorship. His revolutionary movement was based in the Sierra Maestra Mountains in eastern Cuba, and it joined with other resistance groups seeking Batista's ouster. Batista ultimately fled the country on January 1, 1959, leading to 47 years of rule under Fidel Castro until he stepped down from power provisionally in July 2006 because of poor health and ceded power to his brother Raúl Castro.

Although Fidel Castro had promised a return to democratic constitutional rule when he first took power, he instead moved to consolidate his rule, repress dissent, and imprison or execute thousands of opponents. Under the new revolutionary government, Castro's supporters gradually displaced members of less radical groups. Castro moved toward close relations with the Soviet Union, and relations with the United States deteriorated rapidly as the Cuban government expropriated U.S. properties. In April 1961, Castro declared that the Cuban revolution was socialist, and in December 1961, he proclaimed himself to be a Marxist-Leninist. Over the next 30 years, Cuba was a close ally of the Soviet Union and depended on it for significant assistance until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

From 1959 until 1976, Castro ruled by decree. In 1976, however, the Cuban government enacted a new Constitution setting forth the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) as the leading force in state and society, with power centered in a Political Bureau headed by Fidel Castro. Cuba's Constitution also outlined national, provincial, and local governmental structures. Since then, legislative authority has been vested in a National Assembly of People's Power that meets twice annually for brief periods, although the Assembly has permanent commissions that work throughout the year. When the Assembly is not in session, a Council of State, elected by the Assembly, acts on its behalf. According to Cuba's Constitution, the president of the Council of State is the country's head of state and government. Executive power in Cuba is vested in a Council of Ministers, also headed by the country's head of state and government, that is, the president of the Council of State.

Fidel Castro served as head of state and government through his position as president of the Council of State from 1976 until February 2008. Although he provisionally stepped down from power in July 2006 because of poor health and ceded power to his brother Raúl (who held the position of first vice president), Fidel still officially retained his position as head of state and government. National Assembly elections were held in January 2008, and Fidel was once again among the slate of candidates elected to the legislative body. But as the new Assembly was preparing to select the members of the Council of State from among its ranks in February 2008, Fidel announced that he would not accept the position as president of the Council of State. This announcement confirmed his departure as titular head of the Cuban government, and Raúl was selected as president.

More than 10 years after stepping down from power, Fidel Castro died in November 2016 at 90 years of age. While out of power, Fidel had continued to author essays published in Cuban media that cast a shadow on Raúl Castro's rule, and many Cubans reportedly believed that he had encouraged so-called hard-liners in Cuba's Communist Party and government bureaucracy to slow the pace of economic reforms advanced by his brother.3 His death accentuated the generational change that has already begun in the Cuban government and a passing of the older generation of the 1959 revolution.

Political Conditions

Current President Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez was selected by Cuba's National Assembly of People's Power to succeed 86-year-old Raúl Castro on April 19, 2018, after Castro completed his second five-year term as president. Most observers saw Díaz-Canel, who had been serving as first vice president since 2013, as the "heir apparent," but Raúl will continue in his position as first secretary of the PCC until 2021. Cuba does not have direct elections for president. Instead, Cuba's legislature, the National Assembly of People's Power, selects the president of the country's 31-member Council of State; the president, pursuant to Cuba's constitution (Article 74), serves as Cuba's head of state and government.

Raúl Castro had succeeded his long-ruling brother Fidel Castro in 2006, serving provisionally until 2008 and then officially serving two five-year terms as president. He had announced in 2013 that he would not seek a third term, in line with his government's imposition of a two-term limit in 2012. Under Raúl, Cuba implemented gradual market-oriented economic policy changes over the past decade, but critics maintain that the government did not take enough action to foster sustainable economic growth.

Elections for the 605 member-National Assembly (as well as for 15 provincial assemblies) had been expected to be held in January 2018, but the elections were postponed until March 2018. The delay was not unexpected since Cuba's municipal elections, scheduled for September 2017, had been postponed to November 2017 because of significant damage caused by Hurricane Irma. The municipal contests involved the direct election of more than 12,000 officials among 27,000 candidates, but the electoral process was tightly controlled, with the government preventing 175 independent candidates from being nominated. Candidates for the National Assembly and provincial assemblies were also tightly controlled by candidacy commissions, and voters were presented with one candidate for each position.

Cuba's Transition to a New President

President Díaz-Canel, who turned 58 a day after becoming president, is an engineer by training. His appointment as first vice president in 2013 made him the official constitutional successor in case Castro died or could not fulfill his duties. His appointment also represented a move toward bringing about generational change in Cuba's political system. Díaz-Canel became a member of the Politburo in 2003 (the PCC's highest decisionmaking body), held top PCC positions in two provinces, and was higher education minister from 2009 until 2012, when he was tapped to become a vice president on the Council of State.

Although some observers believed Díaz-Canel to be a moderate and more open to reform, a leaked video released in August 2017 appears to contradict that characterization. The video shows him speaking at a closed Communist Party meeting earlier in the year in which he strongly criticized dissidents and independent voices (including those arguing for reform of the socialist system), criticized the expansion of Cuba's private sector, and characterized U.S. efforts toward normalization under President Obama as an attempt to destroy the Cuban revolution. Some observers believe that Díaz-Canel's rhetoric could have been aimed at increasing his acceptance by so-called hard-liners in Cuba's political system who are more resistant to change.4

Cuba's political transition is notable because it is the first time since the 1959 Cuban revolution that a Castro is not in charge of the government. A majority of Cubans today have lived under the rule only of the Castros. Raúl's departure can be viewed as a culmination of the generational leadership change that began several years ago in the government's lower ranks.

It is also the first time that Cuba's head of government is not leader of the PCC. Although separating the roles of government and party leaders could elevate the role of government institutions over the PCC, Raúl Castro has indicated that he expects Díaz-Canel to take over as first secretary of the PCC when his term as party leader ends.5

Another element of the transition is the composition of the new 31-member Council of State. The National Assembly selected 72-year-old Salvador Valdés Mesa as First Vice President, not from the younger generation, but also not from the historical revolutionary period. Valdés Mesa, who already had been serving as one of five vice presidents and is on the Politburo, is the first Afro-Cuban to hold such a high government position. Of the Council of State's members, 45% are new, 48% are women, and 45% are Afro-Cuban or mixed race. Several older revolutionary-era leaders remained on the Council, including Ramiro Valdés, 86 years old, who continues as a vice president.6 Nevertheless, the average age of Council of State members was 54, with 77% born after the 1959 Cuban revolution.7

Challenges for President Díaz-Canel. Although most observers do not anticipate immediate major policy changes under President Díaz-Canel, his government will face two enormous challenges—reforming the economy and responding to desires for greater freedom.

Raúl Castro managed the opening of Cuba's economy to the world, with diversified trade relations, increased foreign investment, and a growing private sector.8 Yet the slow pace of economic reform has stunted economic growth and disheartened Cubans yearning for more economic freedom. From mid-2017 through much of 2018, the government appeared to backtrack by restricting private-sector development and slowing reforms, and for several years the government has delayed a long-anticipated end to its dual-currency system that creates economic distortion (see "Economic Conditions" below).9 A challenge for Díaz-Canel will be moving forward with economic reforms opposed by some conservative elements in the party and state bureaucracy.10

Few observers expect the Díaz-Canel government to ease tight control over the political system, at least in the short to medium term, but it will need to contend with increasing calls for political reform and freedom of expression.11 The liberalization of some individual freedoms that occurred under Raúl Castro (such as legalization of cell phones and personal computers, and expansion of internet connectivity) has increased Cubans' appetite for access to information and the desire for more social and political expression. More broadly, if the next government continues to repress political dissidents and human rights activists, it will remain a point of contention in Cuba's foreign relations.

An important question looking ahead is the extent of influence that Castro and other revolutionary figures will have on government policy. Some observers assert that Raúl will continue to have a role in the decisionmaking process because he will head the PCC until 2021.The former president also headed up a commission making changes to Cuba's 1976 constitution (see discussion below). In July 2018, President Díaz-Canel named his Council of Ministers or Cabinet, but a majority of ministers were holdovers from the Castro government, including those occupying key ministries such as defense, interior, finance, and foreign relations; just 9 of 26 ministers were new, including 2 vice presidents and 7 new ministers.12 After Díaz-Canel marked his first 100 days in office in July 2018, some observers maintained that little had changed politically or economically.

By the end of 2018, however, President Díaz-Canel made several decisions that appeared to demonstrate his independence from the previous Castro government and indicate that he was more responsive to public concerns and criticisms. In early December, as described below in the section on "Economic Conditions," Díaz-Canel eased forthcoming harsh regulations that were about to be implemented on the private sector; many observers believed these regulations would have shrunk the sector. Also in December, the Cuban government backed away from full implementation of controversial Decree 349 that had been issued in July 2018 to regulate artistic expression. After the unpopular decree triggered a flood of criticism from Cuba's artistic community, the government announced that the measure would be implemented gradually and applied with consensus (it remains to be seen, however, whether the government's action will satisfy those working in Cuba's vibrant arts community).13 In a third action in December, the government eliminated a proposed constitutional change that could have paved the way for same-sex marriage after strong public criticisms of the provision (see discussion below on constitutional changes).

Constitutional Changes. As noted, Cuba is in the midst of a process to rewrite and update its 1976 constitution that will be subject to a referendum in February 2019. Drafted by a commission headed by Raúl Castro and approved by the National Assembly in July 2018, the proposed changes were subject to public debate in thousands of workplaces and community meetings into November. After considering public suggestions, the National Assembly made additional changes to the draft constitution, and the National Assembly approved this new version on December 22, 2018. Voters are now scheduled to go to the polls to approve the new constitution on February 24, 2019; it would then be approved in April 2019.

One of the more controversial changes made by the commission in its new draft in December was the elimination of a provision that would have redefined matrimony as gender neutral compared to the current constitution, which refers to marriage as the union between a man and a woman. Cuba's evangelical churches orchestrated a campaign against the provision, and Cuban bishops issued a pastoral message against it.14 The commission chose to eliminate the proposed provision altogether, with the proposed constitution remaining silent on defining matrimony, and maintained that the issue would be addressed in future legislation within two years.15

Among other provisions of the draft constitution are the addition of an appointed prime minster to oversee government operations, an age limit of 60 to become president (Article 127) with a limit of two five-year terms (Article 126), and the right to own private property (Article 22). The draft constitution would still ensure the state's control over the economy and the role of centralized planning (Article 19), and the Communist Party still would be the only recognized party (Article 5).16

Human Rights

The Cuban government has a poor record on human rights, with the government sharply restricting freedoms of expression, association, assembly, movement, and other basic rights since the early years of the Cuban revolution. The government has continued to harass members of human rights and other dissident organizations. These organizations include the Ladies in White (Las Damas de Blanco), currently led by Berta Soler, formed in 2003 by the female relatives of the "group of 75" dissidents arrested that year, and the Patriotic Union of Cuba (UNPACU), led by José Daniel Ferrer García, established in 2011 by several dissident groups with the goal of fighting peacefully for civil liberties and human rights; in August 2018, the Cuban government imprisoned Ferrer arbitrarily for 11 days with no access to his family, according to Amnesty International. In recent years, several political prisoners have conducted hunger strikes; two hunger strikers died—Orlando Zapata Tamayo in 2010 and Wilman Villar Mendoza in 2012. In February 2017, Hamel Santiago Maz Hernández, a member of UNPACU who had been imprisoned since June 2016 after being accused of descato (lack of respect for the government), died in prison.17

Although the human rights situation in Cuba remains poor, the country has made some advances in recent years. In 2008, Cuba lifted a ban on Cubans staying in hotels that previously had been restricted to foreign tourists in a policy that had been pejoratively referred to as "tourist apartheid." In recent years, as the government has enacted limited economic reforms, it has been much more open to debate on economic issues. In 2013, Cuba eliminated its long-standing policy of requiring an exit permit and letter of invitation for Cubans to travel abroad. The change has allowed prominent dissidents and human rights activists to travel abroad and return to Cuba. In recent years, the Cuban government has moved to expand internet connectivity through "hotspots" first begun in 2015 and through the launching of internet capability on cellphones in late 2018. As noted below, short-term detentions for political reasons declined significantly in 2017 and 2018, although there were still almost 2,900 such detentions in 2018.

Congressional Resolutions. On April 11, 2018, the Senate approved S.Res. 224 (Durbin), which commemorated the legacy of democracy activist Oswaldo Payá, called on the Cuban government to allow an impartial, third-party investigation into the circumstances surrounding Payá's death in a car accident in July 2012, and called on the Cuban government to cease violating human rights and begin providing democratic freedoms to Cuban citizens. In 2012, the Senate had approved S.Res. 525 (Nelson), which honored the life and legacy of Payá and also called for an impartial, third-party investigation. Payá had founded the Christian Liberation Movement in 1988, a civil society group advocating peaceful democratic change and respect for human rights. He founded the Varela Project in 1996, which collected thousands of signatures supporting a national plebiscite for political reform in Cuba.18

Two similar but not identical resolutions introduced in May 2018, S.Res. 511 (Rubio) and H.Res. 916 (Diaz-Balart), would have honored Las Damas de Blanco as the recipient of the 2018 Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty. The resolutions also would have expressed solidarity and commitment to the democratic aspirations of the Cuban people and call on the Cuban government to allow members of the group to travel freely.

Political Prisoners. On October 16, 2018, the State Department's U.S. Mission to the United Nations launched a campaign to call attention to the plight of Cuba's "estimated 130 political prisoners." Cuban diplomats attempted to disrupt the event by making noise and shouting, although their actions appeared to call more attention to the event and, for some observers, demonstrated the Cuban government's disdain for freedom of expression.19 Secretary of State Mike Pompeo wrote an open letter to Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez on December 7, 2018, asking for a substantive explanation for the continued detention of eight specific political prisoners and an explanation of the charges and evidence against other individuals held as political prisoners.20

In January 2019, the Havana-based Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation (CCDHRN) estimated that Cuba held some 130-140 political prisoners in some 150 prisons and internment camps. In June 2018, the CCDHRN made public a list with 120 prisoners for political reasons, consisting of 96 opponents or those disaffected toward the regime (over 40 are members of UNPACU) and 24 accused of employing or planning some form of force or violence.21

According to the State Department's human rights report on Cuba covering 2017, issued in April 2018, the exact number of political prisoners was difficult to determine, but human rights organizations estimated that there were 65 to 100 political prisoners. The report noted the lack of governmental transparency, along with its systematic violations of due process rights, which masked the nature of criminal charges and prosecutions and allowed the government to prosecute peaceful human rights activists for criminal violations or "dangerousness." As noted in the report, the government refused international humanitarian organizations and the United Nations access to its prisons and detention centers, and closely monitored and often harassed domestic organizations that tracked political prisoner populations.22

Political activist Dr. Eduardo Cardet, designated by Amnesty International (AI) as a "prisoner of conscience," has been imprisoned since November 2016 for publicly criticizing Fidel Castro and was sentenced to three years in prison. AI maintains that Cardet, a leader in the dissident Christian Liberation Movement, was sent to prison solely for peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression and has called for his immediate release. The human rights group issued an urgent action notice in January 2018 calling attention to Cardet's case after he was attacked by several prisoners in December 2017. In June 2018, AI issued another urgent action notice for Cardet, maintaining that Cuban authorities suspended family visiting rights for him because of his family's activism on the case.23

A second AI-designated prisoner of conscience, Cuban biologist Dr. Ariel Ruiz Urquiola, was sentenced to a year in prison in May 2018 for the crime of disrespecting authority (desacato). Urquiola reportedly had referred to several Cuban government forest rangers as "rural guards," a derogatory reference to a repressive agency before the Cuban revolution. The rangers had been checking whether Urquiola had proper permits to cut down several trees and build a fence, which reportedly he had. In June 2018, AI issued two urgent action notices on Urquiola calling for his release and for visits while imprisoned. He was conditionally released from prison on July 3, 2018, following a prolonged hunger strike.24

On October 15, 2018, the Cuban government released UNPACU activist Tomás Núñez Magdariaga from prison after a 62-day hunger strike. Magdariaga had been sentenced to a year in jail for allegedly making threats to a security agent. The State Department had called for his release, maintaining he was falsely charged and convicted in a sham trial. Amnesty International had expressed concern for his health and called on Cuba to make public evidence against him.25

Over the past decade, the Cuban government has released large numbers of political prisoners at various junctures. In 2010 and 2011, with the intercession of the Cuban Catholic Church, the government released some 125 political prisoners, including the remaining members of the "group of 75" arrested in 2003 who were still in prison. In the aftermath of the December 2014 shift in U.S. policy toward Cuba, the Cuban government released another 53 political prisoners, although several were subsequently rearrested.26 In 2017, the Cuban government released several political prisoners that had been dubbed "prisoners of conscience" by Amnesty International. This included graffiti artist Danilo Maldonado Machado (known as El Sexto) who subsequently testified before a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing in February 2017.27

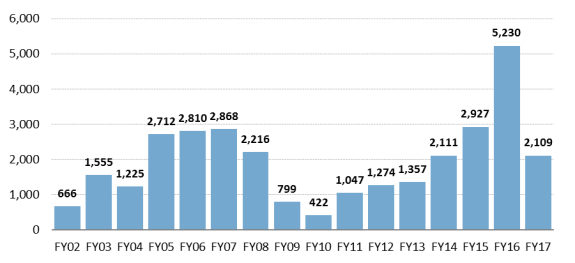

Short-Term Detentions. Short-term detentions for political reasons increased significantly from 2010 through 2016, a reflection of the government's change of tactics in repressing dissent away from long-term imprisonment. The CCDHRN reports that the number of such detentions grew annually from at least 2,074 in 2010 to at least 8,899 in 2014. The CCDHRN reported a very slight decrease to 8,616 short-term detentions in 2015, but this figure increased again to at least 9,940 detentions for political reasons in 2016, the highest level recorded by the human rights organization.

Since 2017, however, the CCDHRN has reported a significant decline in short-term detentions. In 2017, the number of short-term detentions fell to 5,155, almost half the number detained in 2016 and the lowest level since 2011. The decline in short-term detentions continued in 2018, with 2,873 reported short-term detentions, almost a 45% decline from 2017 and the lowest level since 2010.28

Bloggers and Civil Society Groups. Over the past several years, numerous independent Cuban blogs have been established. Cuban blogger Yoani Sánchez has received considerable international attention since 2007 for her website, Generación Y, which includes commentary critical of the Cuban government. In May 2014, Sánchez launched an independent digital newspaper in Cuba, 14 y medio, available on the internet, distributed through a variety of methods in Cuba, including CDs, USB flash drives, and DVDs.29

The Catholic Church became active in broadening the debate on social and economic issues through its publications. The Church also has played a role in providing social services, including soup kitchens, services for the elderly and other vulnerable groups, after-school programs, job training, and even college coursework.

Estado de SATS, a forum founded in 2010 by human rights activist Antonio Rodiles, has had the goal of encouraging open debate on cultural, social, and political issues. The group has hosted numerous events and human rights activities over the years, but it also has been the target of government harassment, as has its founder.

Other notable online forums and independent or alternative media that have developed include Cuba Posible (founded by two former editors of the Catholic publication Espacio Laical), Periodismo del Barrio (focusing especially on environmental issues), El Toque, and OnCuba (a Miami-based digital magazine with a news bureau in Havana).30

Trafficking in Persons. The State Department released its 2018 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report on June 28, 2018, and for the fourth consecutive year Cuba was placed on the Tier 2 Watch List (in prior years, Cuba had Tier 3 status).31 Tier 3 status refers to countries whose governments do not fully comply with the minimum standards for combatting trafficking and are not making significant efforts to do so. In contrast, Tier 2 Watch List status refers to countries whose governments, despite making significant efforts, do not fully comply with the minimum standards and still have some specific problems (e.g., an increasing number of victims or failure to provide evidence of increasing antitrafficking efforts) or whose governments have made commitments to take additional antitrafficking steps over the next year. A country normally is automatically downgraded to Tier 3 status if it is on the Tier 2 Watch List for three consecutive years unless the Secretary of State authorizes a waiver. The State Department issued such a waiver for Cuba in 2017 because the government had devoted sufficient resources to a written plan that, if implemented, would constitute significant efforts to meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking. In the 2018 TIP report, the State Department again issued a waiver for Cuba allowing it to remain on the Tier 2 Watch List for the fourth consecutive year. Such a waiver, however, is only permitted for two years. After the third year, the country must either go up to Tier 2 or down to Tier 3.

The State Department initially upgraded Cuba from Tier 3 to Tier 2 Watch List status in its 2015 TIP report because of the country's progress in addressing and prosecuting sex trafficking, including the provision of services to sex-trafficking victims, and its continued efforts to address sex tourism and the demand for commercial sex.32

In its 2016 TIP report, the State Department maintained that Cuba remained on the Tier 2 Watch List for the second consecutive year because the country did not improve antitrafficking efforts compared to 2015. Nevertheless, the 2016 report noted that the Cuban government continued efforts to address sex trafficking, including prosecution and conviction, and the provision of services to victims. The State Department noted that the Cuban government released a report on its antitrafficking efforts in October 2015; that multiple government ministries were engaged in antitrafficking efforts; and that the government funded child protection centers and guidance centers for women and families, which served crime victims, including trafficking victims. However, the report also noted that the Cuban government did not prohibit forced labor, report efforts to prevent forced labor, or recognize forced labor as a possible issue affecting Cubans in medical missions abroad.33

In its 2017 TIP report, the State Department maintained that the Cuban government demonstrated significant efforts during the reporting period by prosecuting and convicting sex traffickers, providing services to sex trafficking victims, releasing a written report on its antitrafficking efforts, and coordinating antitrafficking efforts across government ministries. The State Department noted, however, that the Cuban penal code did not criminalize all forms of trafficking and did not prohibit forced labor, report efforts to prevent forced labor domestically, or recognize forced labor as a possible issue affecting Cubans working in medical missions abroad.34

In its 2018 TIP report, the State Department noted the Cuban government's significant efforts of prosecuting and convicting more traffickers, creating a directorate to provide specialized attention to child victims of crime and violence, including trafficking, and publishing its antitrafficking plan for 2017-2020. The State Department also noted, however, that the Cuban government did not demonstrate increasing efforts compared to the previous reporting period. It maintained that the government did not criminalize most forms of forced labor or sex trafficking for children ages 16 or 17, and did not report providing specialized services to identified victims. The State Department also made several recommendations for Cuba to improve its antitrafficking efforts, including the enactment of a comprehensive antitrafficking law that prohibits and sufficiently punishes all forms of trafficking.

Engagement between U.S. and Cuban officials on antitrafficking issues has increased in recent years. In January 2017, U.S. officials met with Cuban counterparts in their fourth such exchange to discuss bilateral efforts to address human trafficking.35 Subsequently, on January 16, 2017, the United States and Cuba signed a broad memorandum of understanding on law enforcement cooperation in which the two countries stated their intention to collaborate on the prevention, interdiction, monitoring, and prosecution of transnational or serious crimes, including trafficking in persons.36 In February 2018, the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security hosted meetings in Washington, DC, with Cuban officials on efforts to combat trafficking in persons.37

|

Human Rights Reporting on Cuba Amnesty International (AI), Cuba, https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/americas/cuba/. Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation (Comisión Cubana de Derechos Humanos y Reconciliación Nacional, CCDHRN), an independent Havana-based human rights organization that produces a monthly report on short-term detentions for political reasons. CCDHRN, "Cuba: Algunos Actos de Represión Política en el Mes de Diciembre de 2018," January 3, 2019, at https://www.14ymedio.com/nacional/Informe-arbitrarios-correspondientes-diciembre-CCDHRN_CYMFIL20190102_0001.pdf. CCDHRN, "Lista Parcial de Condenados o Procesados en Cuba por Razones Politicas en Esta Fecha," June 11, 2018, at https://www.14ymedio.com/nacional/LISTA-PRESOS-JUNIO_CYMFIL20180611_0001.pdf. 14ymedio.com, independent digital newspaper, based in Havana, at http://www.14ymedio.com/. Human Rights Watch (HRW), https://www.hrw.org/americas/cuba. HRW's 2018 World Report maintains that "the Cuban government continues to repress dissent and punish public criticism," at https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2018/country-chapters/cuba Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Annual Report 2017, March 23, 2018, Chapter IV has a section on Cuba, at http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/docs/annual/2017/docs/IA2017cap.4bCU-en.pdf. U.S. Department of State, Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2017, April 20, 2018, at https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/277567.pdf. |

Economic Conditions

Cuba's economy continues to be largely state-controlled, with the government owning most means of production and employing a majority of the workforce. Key sectors of the economy that generate foreign exchange include the export of professional services (largely medical personnel to Venezuela); tourism, which has grown significantly since the mid-1990s, with an estimated 4.75 million tourists visiting Cuba in 2018; nickel mining, with the Canadian mining company Sherritt International involved in a joint investment project; and a biotechnology and pharmaceutical sector that supplies the domestic health care system and has fostered a significant export industry. Remittances from relatives living abroad, especially from the United States, also have become an important source of hard currency, amounting to some $3 billion in 2016. The once-dominant sugar industry has declined significantly over the past 20 years. Because of drought, damage from Hurricane Irma, and subsequent months of heavy rains, the 2017-2018 sugar harvest dropped by almost 44% to just over 1 million metric tons (MT), compared to 1.8 million MT the previous year. The outlook for the 2018-2019 harvest is 1.5 million MT, almost a 50% improvement; for comparison, in 1990, Cuba produced 8.4 million MT of sugar.38

For more than 15 years, Cuba has depended heavily on Venezuela for its oil needs. In 2000, the two countries signed a preferential oil agreement (essentially an oil-for-medical-personnel barter arrangement) that until recently provided Cuba with some 90,000-100,000 barrels of oil per day, about two-thirds of its consumption. Cuba's goal of becoming a net oil exporter with the development of its offshore deepwater oil reserves was set back in 2012, when the drilling of three exploratory oil wells was unsuccessful. This setback, combined with Venezuela's economic difficulties, has raised Cuban concerns about the security of the support received from Venezuela. Since 2015, Venezuela has cut the amount of oil that it sends to Cuba, and Cuba has increasingly turned to other suppliers for its oil needs, including Russia and Algeria. In the summer of 2018, from June through August, Venezuela reportedly resumed exporting a key crude oil to Venezuela that it had suspended in 2017 due to needs in Venezuela.39

The government of Raúl Castro implemented a number of economic policy changes, but economists were disappointed that more far-reaching reforms were not implemented. At the PCC's seventh party congress, held in April 2016, Raúl Castro reasserted that Cuba would move forward with updating its economic model "without haste, but without pause."40 A number of Cuba's economists have pressed the government to enact more far-reaching reforms and embrace competition for key parts of the economy and state-run enterprises. These economists criticize the government's continued reliance on central planning and its monopoly on foreign trade.

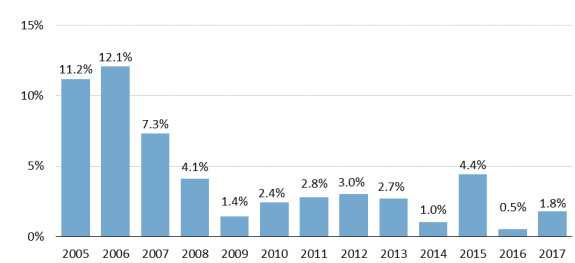

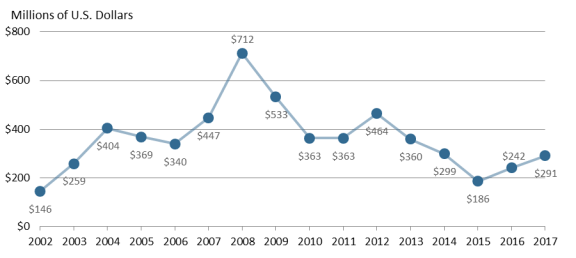

Economic Growth.41 Cuba experienced severe economic contraction from 1990 to 1993, with an estimated decline in gross domestic product ranging from 35% to 50% when the Soviet Union collapsed and Russian financial assistance to Cuba practically ended. Growth resumed after that time, as Cuba moved forward with some limited market-oriented economic reforms, and growth was especially strong in the 2004-2007 period, averaging more than 9% annually. The economy benefitted from the growth of the tourism, nickel, and oil sectors and from support from Venezuela and China in terms of investment commitments and credit lines. The economy was hard-hit by several hurricanes and storms in 2008 and the global financial crisis in 2009, with the government forced to implement austerity measures that slowed growth. From 2010 to 2015, Cuba's economy experienced low to moderate economic growth, ranging from a low of 1% in 2014 to a high of 4.4% in 2015. In 2016, however, the economy grew by just 0.5% because of lower export earnings, reduced support from Venezuela, and austerity measures (preliminary Cuban government estimates had forecast an economic contraction of 0.9%, but this was revised to 0.5% growth in January 2018).42

In September 2017, Hurricane Irma struck in September, killing 10 people in Cuba and affecting more than 2 million people along 300 miles of the northern coast.43 The storm damaged infrastructure (electric power, water and sanitation systems), the agricultural sector, and tourism facilities, and it flooded low-lying areas of Havana.44

Nevertheless, the Cuban government reports that the economy grew 1.8% in 2017 and an estimated 1.2% in 2018, and it predicts 1.5% growth in 2019. President Díaz-Canel has said that austerity measures begun in 2016 will continue in 2019. The economy has been hurt by reduced support from Venezuela over the past several years and the unexpected December 2018 ending of Cuba's program sending medical professionals to Brazil, which had provided Cuba with some $400 million a year.45 The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) predicts economic growth will slow to 0.8% in 2019 and 0.4% in 2020, as tourism grows more moderately because of a slowdown in arrivals from the United States. According to the EIU, the biggest risk to Cuba's economic performance is the complete elimination of support from Venezuela.46

|

Figure 2. Cuba: Real Gross Domestic Product Growth (%), 2005-2017 |

|

|

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, Country Data Tool, 2019. |

Private Sector. The Cuban government employs a majority of the labor force, but the government has been allowing more private-sector activities. In 2010, the government opened up a wide range of activities for self-employment and small businesses to almost 200 categories of work allowed; the number of self-employed or cuentapropistas rose from 144,000 in 2009 to about 588,000 as of October 2018. Analysts contend that the government needs to do more to aid the development of the private sector, including an expansion of authorized activities to include more white-collar occupations and state support for credit to support small businesses.47

Beginning in mid-2017, the government took several steps to restrict private-sector development. In August 2017, it stopped issuing new licenses for 27 private-sector occupations, including for private restaurants and for renting private residences; closed a fast-growing cooperative that had provided accounting and business consultancy services; and put restrictions on construction cooperatives. The government maintains that it took the actions to "perfect" the functioning of the private sector and curb illicit activities, such as the sale of stolen state property, tax evasion, and labor violations.

In February 2018, press reports provided details about draft government regulations being considered that would increase state control over the private sector, limit business licenses to a single activity, reduce and consolidate the current 200 categories of work to 123 categories, and limit the size of private restaurants.48 The regulations ultimately were released in July 2018 and were to take effect in December, at the same time the government would resume issuing licenses for business activities that had been frozen since August 2017. The objectives of the new regulations were to increase taxation oversight of the private sector and to control the concentration of wealth and rising inequality, but many observers believed the regulations were aimed at stifling private-sector growth because of the government's concerns regarding that sector's independence from the government.

Just two days before the regulations were to go into effect, President Díaz-Canel did an about-face and announced on December 5, 2018, that some aspects of the regulations viewed as especially egregious by the private sector would be eliminated or eased. Most significantly, individuals would not be limited to one licensed activity; restaurants, bars, and cafeterias would not be not subject to a limit of 50 seats; and the requirements for maintaining a minimum balance in bank accounts would be reduced from the equivalent of three months of tax payments to two months and would apply to just 6 of the 123 categories of employment.49 Analysts view the backtracking as an indication that President Díaz-Canel is willing to make policy changes in response to public opinion and as a sign that the government does not want to shrink the private sector.

Currency Unification/Reform. A major challenge for the development of the private sector is the lack of money in circulation. Most Cubans do not make enough money to support the development of small businesses. Cuba has two official currencies—Cuban pesos (CUPs) and Cuban convertible pesos (CUCs); for personal transaction, the exchange rate for the two currencies is CUP24/CUC1. Most people are paid CUPs, and the minimum monthly wage in Cuba is 225 CUPs (just over $9), although this minimum wage does not apply to the nonstate sector. According to the State Department, even with other government support such as free education, housing, some food, and subsidized medical care, the average monthly wage of 700 CUPs ($29) does not provide for a reasonable standard of living.50 For increasing amounts of consumer goods, CUCs are used. Cubans with access to foreign remittances or who work in private-sector activities catering to tourists and foreign diplomats have fared better than those serving the Cuban market.

The Cuban government announced in 2013 that it would end its dual-currency system and move toward monetary unification, but the action has been delayed for several years. Currency reform is ultimately expected to lead to productivity gains and improve the business climate, but an adjustment would create winners and losers.51 At the PCC's April 2016 Congress, Raúl Castro called for moving toward a single currency as soon as possible to resolve economic distortions. In January 2018, EU officials visiting Cuba offered technical assistance regarding currency reform and unification.52 Some economists assert, however, that Cuba is unlikely to go forward with currency reform this year because of the country's deep structural economic problems and because of the ongoing constitutional reform process.53

Agricultural Sector. A reform effort under Raúl Castro focused on the agricultural sector, a vital issue because Cuba reportedly imports some 70%-80% of its food needs, according to the World Food Programme.54 In an effort to boost food production, the government turned over idle land to farmers and given farmers more control over how to use their land and what supplies to buy. Despite these and other efforts, overall food production has been significantly below targets. In addition, as noted above, Hurricane Irma caused damage to the agricultural sector, particularly sugar, in September 2017. As a result, in the first six months of 2018, overall food production reportedly decreased about 10% to 15% compared to the same period in 2017.55

Foreign Investment. The Cuban government adopted a new foreign investment law in 2014 with the goal of attracting increased levels of foreign capital to the country. The law cuts taxes on profits by half, to 15%, and exempts companies from paying taxes for the first eight years of operation. The law also eliminates employment or labor taxes, although companies still must hire labor through state-run companies, with agreed wages. A fast-track procedure for small projects reportedly streamlines the approval process, and the government agreed to improve the transparency and time of the approval process for larger investments.56

A Mariel Special Development Zone (ZED Mariel) was established in 2014 near the port of Mariel to attract foreign investment. To date, ZED Mariel has approved some 43 investment projects, which are at various stages of development.57 In November 2017, Cuba approved a project for Rimco (the exclusive dealer for Caterpillar in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Eastern Caribbean) to become the first U.S. company to be located in the ZED Mariel. Rimco plans to set up a warehouse and distribution center in 2018 to distribute Caterpillar equipment. In September 2018, the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center of Buffalo, NY, announced it was entering into a joint venture with Cuba's Center for Molecular Immunology focused on the development of cancer therapies; the joint venture will be located in the ZED Mariel.

According to Cuba's Minister of Foreign Trade and Investment Rodrigo Malmierca, Cuba has signed more than 200 investment projects valued at $5.5 billion since it made changes to its investment law in 2014, with $1.5 billion of that in 2018. The actual amount invested reportedly is much less, with about $500 million annually.58 In November 2018, the Cuban government updated its wish list for foreign investment, which includes 525 projects representing potential investment of $11.6 billion in such high-priority areas as tourism, agriculture and food production, oil, the industrial sector, and biotechnology.59

|

Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, annual proceedings, at http://www.ascecuba.org/publications/annual-proceedings/. Brookings Institution, at https://www.brookings.edu/topic/cuba/. Richard E. Feinberg, Cuba's Economy after Raúl Castro: A Tale of Three Worlds, February 2018, at https://www.brookings.edu/research/cubas-economy-after-raul-castro-a-tale-of-three-worlds/. Caitlyn Davis and Ted Piccone, Sustainable Development: The Path to Economic Growth in Cuba, June 28, 2017, at https://www.brookings.edu/research/sustainable-development-the-path-to-economic-growth-in-cuba/. Richard E. Feinberg and Richard S. Newfarmer, Tourism in Cuba, Riding the Wave Toward Sustainable Prosperity, December 2, 2016, at https://www.brookings.edu/research/tourism-in-cuba/. Richard E. Feinberg, The Cuban Economy Could Sing—with a Stronger Score, October 13, 2016, at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2016/10/13/the-cuban-economy-could-sing-with-a-stronger-score/. Ted Piccone and Harold Trinkunas, The Cuba-Venezuela Alliance: The Beginning of the End? June 2014, at http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2014/06/16-cuba-venezuela-alliance-piccone-trinkunas. The Cuban Economy, La Economia Cubana, website maintained by Arch Ritter, from Carlton University, Ottawa, Canada, available at http://thecubaneconomy.com/. Revista Temas (Havana), links to the Cuban journal's articles on economy and politics, in Spanish, at http://temas.cult.cu/. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información, República de Cuba (Cuba's National Office of Statistics and Information), at http://www.one.cu/. U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc., website at http://www.cubatrade.org/. |

Cuba's Foreign Relations

During the Cold War, Cuba had extensive relations with, and support from, the Soviet Union, which provided billions of dollars in annual subsidies to sustain the Cuban economy. This subsidy system helped to fund an activist foreign policy and support for guerrilla movements and revolutionary governments abroad in Latin America and Africa. With an end to the Cold War, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the loss of Soviet financial support, Cuba was forced to abandon its revolutionary activities abroad. As its economy reeled from the loss of Soviet support, Cuba was forced to open up its economy and engage in economic relations with countries worldwide. In ensuing years, Cuba diversified its trading partners, although Venezuela under populist leftist President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) became one of Cuba's most important partners, leading to Cuba's dependence on Venezuela for oil imports. In 2017, the leading sources of Cuba's imports in terms of value were Venezuela (18.1%, down from 40% in 2014), China (16.3%), and Spain (10.8%); the leading destinations of Cuban exports were Canada (19.4%), Venezuela (15.6%), China (5.2%), and Spain (8.6%).60

Russia. Relations with Russia, which had diminished significantly in the aftermath of the Cold War, have strengthened somewhat over the past several years. Cuban President Díaz-Canel visited Russia for three days beginning November 1, 2018, after which he visited North Korea, China, Vietnam, and Laos.

Russia's interest in the broader Latin America and Caribbean region appeared to increase in response to U.S. actions taken in the aftermath of Russia's intervention in Georgia in 2008 and Russia's annexation of the Crimea region and military intervention in Ukraine in 2014. For many observers, one of Russia's main objectives in the Latin American and Caribbean region is to demonstrate that it is a global power that can operate in the U.S. neighborhood, or "backyard."61

Just before a 2014 trip to Cuba, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed into law an agreement writing off 90% of Cuba's $32 billion Soviet-era debt, with some $3.5 billion to be paid back by Cuba over a 10-year period that would fund Russian investment projects in Cuba.62 In the aftermath of Putin's trip, press reports claimed that Russia would reopen its signals intelligence facility at Lourdes, Cuba, which had closed in 2002, but President Putin denied that his government would reopen the facility.63

Trade relations between Russia and Cuba have not been significant, although they grew in 2017 because of new Russian oil exports to Cuba. According to Russian trade statistics, total trade between the two countries was valued at $290 million in 2017, an almost 17% increase over 2016. This represented less than 2% of Cuba's trade worldwide. Russia's imports from Cuba amounted to almost $14 million in 2017, led by pharmaceutical products and rum, while Russia's exports to Cuba amounted to almost $277 million, led by motor vehicles (and parts) and oil.64

Russian energy companies have been involved in oil exploration in Cuba. Gazprom was in a partnership with the Malaysian state oil company, Petronas, which conducted unsuccessful deepwater oil drilling off Cuba's western coast in 2012. The Russian oil company Zarubezhneft began drilling in Cuba's shallow coastal waters east of Havana in late 2012 but stopped work in 2013 because of disappointing results. In 2014, Russian energy companies Zarubezhneft and Rosneft signed an agreement with Cuba's state oil company Unión Cuba-Petróleo (CUPET) for the development of an offshore exploration block, and Rosneft agreed to cooperate with Cuba in studying ways to optimize existing production at mature fields.65 In 2017, Rosneft began to ship oil to Cuba, a result of Cuba's efforts to diversify its sources of foreign oil because of Venezuela's diminished capacity.66

Russian officials publicly welcomed the improvement in U.S.-Cuban relations under the Obama Administration, although some viewed the change in U.S. policy as setback for Russian overtures in the region. As U.S.-Cuban normalization talks were beginning in Havana in January 2015, a Russian intelligence ship docked in Havana. In October 2016, a Russian military official maintained that Russia was reconsidering reestablishing a military presence in Cuba (and Vietnam), although there was no indication that Cuba would be open to the return of the Russian military.67 The two countries signed a bilateral cooperation agreement in December 2016 for Russia's support to help Cuba modernize its defense sector until 2020.68

In June 2017, when President Trump announced a partial rollback of the U.S. policy of engagement with Cuba, Russia's foreign ministry criticized the president for resorting to "Cold War" rhetoric.69 Some reports indicate that as U.S. relations with Cuba have deteriorated over the past year, Russia has been attempting to further increase its ties to Cuba, with high-level meetings between Cuban and Russian officials and increased economic, military, and cultural engagement.70 In March 2018, the same Russian intelligence ship noted above again stopped in Havana.71

For Cuba, a deepening of relations with Russia could help economically, especially regarding oil, and also could serve as a counterbalance to the partial rollback of U.S. engagement policy by the Trump Administration.72 However, President Díaz-Canel's November 2018 trip to Russia reportedly did not yield significant results. Press reports indicate that Cuba received a $50 million credit line for purchases of Russian military weapons and spare parts and contracts valued at more than $260 million (some that already were in the pipeline) to modernize three power plants and a metal processing plant and upgrade Cuba's railway system.73

The U.S. Southern Command's February 2018 posture statement presented to Congress expressed concern about Russia's increased role in the Western Hemisphere. It stated that Russia's expanded port and logistics access in Cuba (as well as Nicaragua and Venezuela) provide the country "with persistent, pernicious presence, including more frequent maritime intelligence collection and visible force projection in the Western Hemisphere." It stated that Russia's robust relationships with these three countries provide it "with a regional platform to target U.S. and partner nation facilities and assets, exert negative influence over undemocratic governments, and employ strategic options in the event of a global contingency."74 Along these lines, there has been concern in Congress about the role of Russia in Latin America, including in Cuba. The conference report to the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for FY2019, P.L. 115-232 (H.R. 5515), requires the Defense Intelligence Agency to submit a report on security cooperation between Russia, and Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, including a description of any military or intelligence infrastructure, facilities, and assets developed by Russia in the three countries and any associated agreements or understanding between Russia and the three countries.

China. During the Cold War, Cuba and China did not have close relations because of Sino-Soviet tensions, but bilateral relations with China have grown closer over the past 15 years, including a notable increase in trade. Since 2004, Chinese leaders have made a series of visits to Cuba: then-President Hu Jintao visited in 2004 and 2008; President Xi Jinping visited in 2014 (and when he was vice president in 2011); and, most recently, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited in 2016, reportedly signing some 30 economic cooperation agreements.75 Raúl Castro also visited China in 2008 and 2012; during the 2012 trip, he signed cooperation agreements focusing on trade and investment issues. In January 2018, Raúl Castro met with Song Tong, a special envoy of President Xi Jinping, with discussion reportedly focused on strengthening ties. Castro noted that the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) would like to promote exchanges with its Chinese counterpart in an effort to help upgrade Cuba's social and economic model.76

More recently, as noted above, Cuban President Díaz-Canel visited China in early November 2018. According to Chinese state media, President Xi called for a long-term plan to promote the development of China-Cuba ties and said that China would welcome Cuba's participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, which is focused on infrastructure development around the world. President Xi called on both countries to enhance cooperation on trade, energy, agriculture, tourism, and biopharmaceutical manufacturing.77

While Cuba's relationship with China undoubtedly has an ideological component since both are the among the world's remaining communist regimes, economic linkages and cooperation appear to be the most significant component of bilateral relations.