U.S. Agricultural Trade with Cuba: Current Limitations and Future Prospects

After more than half a century during which trade relations between the United States and Cuba have evolved from a tight economic embargo to a narrow window of trade in U.S. agricultural and medical products, the diplomatic initiative that President Obama announced in December 2014 to restore more normal relations with Cuba has raised the possibility that bilateral relations could move toward an expansion in commercial opportunities.

Many U.S. agricultural and food industry interests believe the Cuban market could offer meaningful export expansion potential for their products—but only if a number of restrictions under the U.S. embargo on trade with Cuba were to be removed. Among the measures most often cited as inhibiting exports of U.S. products, while simultaneously benefiting foreign competitors, are a prohibition on the provision of private financing and credit on sales to Cuba; denial of access to U.S. government credit guarantees and export promotion programs; the ban on general tourism to Cuba; and the general prohibition on U.S. imports of Cuban goods.

A question that arises for policymakers as diplomatic relations with Cuba are restored is what the potential opportunity is for U.S. food and agricultural exports to Cuba if bilateral relations are returned to a more normal status in the future. Corollary questions are what agricultural products Cuba might export to the United States if the existing prohibition on Cuban products were to be removed, and what implications trade in Cuban products could hold for U.S. agriculture.

Numerous stakeholders within the food and agriculture industry, as well as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), contend that U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba could expand markedly if key elements of the embargo against Cuba were removed. The prohibition on providing private credit and financing and the ban on access to government export promotion programs are two that are often cited. USDA asserts that basic commodities, like U.S. rice, wheat, dry beans, and dried milk could readily gain market share in Cuba under more normal trade relations in view of the close proximity of U.S. ports to Cuba compared with export competitors. Higher value food and agricultural products might make inroads in Cuba over time, it is argued, particularly if Cuba could increase its access to foreign exchange by selling its products in the United States.

Similarly, a report on Cuban imports and the effects of U.S. restrictions on U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba that the U.S. International Trade Commission issued in March 2016 at the request of the Senate Finance Committee concluded that the removal of U.S. restrictions on trade could result in significant gains for U.S. agricultural exports.

A concern voiced by some in agriculture is that opening the U.S. market to Cuba could pave the way for a new influx of tropical fruit and vegetable products that would compete directly with winter-season production in Florida, particularly if foreign investors perceive the opportunity to create an export platform for the U.S. market in Cuba. Among the concerns raised is that Cuban production is often subsidized by the government; also, that allowing Cuban produce into the U.S. market could become a conduit for introducing new pests and plant diseases. While Cuba was once a leading sugar producer and the largest foreign supplier to the U.S. market prior to the embargo, its sugar industry has undergone a steep decline since the demise of the Soviet Union. Cuba continues to export limited quantities of sugar and might very well request access to the lucrative U.S. sugar market if normal trade relations were restored. But any such opportunity would most likely be the result of a negotiated agreement between the United States and Cuba.

Some Members of Congress have introduced legislation in the 114th Congress that would ease U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba. These bills span a broad range of approaches, from a narrow focus on removing the ban on providing private financing and credit for the sale of agricultural goods to Cuba to far broader legislative initiatives that seek to lift the Cuban embargo altogether.

U.S. Agricultural Trade with Cuba: Current Limitations and Future Prospects

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background and Perspective

- From Embargo and Sanctions to a Window for Farm Exports

- Obstacles Impeding U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

- USDA Identifies Key Barriers to Expanded Agriculture Exports to Cuba

- U.S. Agricultural Trade with Cuba over the Years

- U.S. ITC Sees Potential for Expansion in U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

- USDA Sees Potential Sizable Gains in Farm Exports to Cuba

- A Possible Market Opportunity for U.S. Rice

- Florida Produce Could Face Heightened Competition from Cuban Exports

- Cuba's Agricultural Exports: Narrow in Scope, Limited in Quantity

- Cuban Sugar Exports and the U.S. Market

- Legislative Initiatives Aimed at Easing Restrictions on U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

Figures

Summary

After more than half a century during which trade relations between the United States and Cuba have evolved from a tight economic embargo to a narrow window of trade in U.S. agricultural and medical products, the diplomatic initiative that President Obama announced in December 2014 to restore more normal relations with Cuba has raised the possibility that bilateral relations could move toward an expansion in commercial opportunities.

Many U.S. agricultural and food industry interests believe the Cuban market could offer meaningful export expansion potential for their products—but only if a number of restrictions under the U.S. embargo on trade with Cuba were to be removed. Among the measures most often cited as inhibiting exports of U.S. products, while simultaneously benefiting foreign competitors, are a prohibition on the provision of private financing and credit on sales to Cuba; denial of access to U.S. government credit guarantees and export promotion programs; the ban on general tourism to Cuba; and the general prohibition on U.S. imports of Cuban goods.

A question that arises for policymakers as diplomatic relations with Cuba are restored is what the potential opportunity is for U.S. food and agricultural exports to Cuba if bilateral relations are returned to a more normal status in the future. Corollary questions are what agricultural products Cuba might export to the United States if the existing prohibition on Cuban products were to be removed, and what implications trade in Cuban products could hold for U.S. agriculture.

Numerous stakeholders within the food and agriculture industry, as well as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), contend that U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba could expand markedly if key elements of the embargo against Cuba were removed. The prohibition on providing private credit and financing and the ban on access to government export promotion programs are two that are often cited. USDA asserts that basic commodities, like U.S. rice, wheat, dry beans, and dried milk could readily gain market share in Cuba under more normal trade relations in view of the close proximity of U.S. ports to Cuba compared with export competitors. Higher value food and agricultural products might make inroads in Cuba over time, it is argued, particularly if Cuba could increase its access to foreign exchange by selling its products in the United States.

Similarly, a report on Cuban imports and the effects of U.S. restrictions on U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba that the U.S. International Trade Commission issued in March 2016 at the request of the Senate Finance Committee concluded that the removal of U.S. restrictions on trade could result in significant gains for U.S. agricultural exports.

A concern voiced by some in agriculture is that opening the U.S. market to Cuba could pave the way for a new influx of tropical fruit and vegetable products that would compete directly with winter-season production in Florida, particularly if foreign investors perceive the opportunity to create an export platform for the U.S. market in Cuba. Among the concerns raised is that Cuban production is often subsidized by the government; also, that allowing Cuban produce into the U.S. market could become a conduit for introducing new pests and plant diseases. While Cuba was once a leading sugar producer and the largest foreign supplier to the U.S. market prior to the embargo, its sugar industry has undergone a steep decline since the demise of the Soviet Union. Cuba continues to export limited quantities of sugar and might very well request access to the lucrative U.S. sugar market if normal trade relations were restored. But any such opportunity would most likely be the result of a negotiated agreement between the United States and Cuba.

Some Members of Congress have introduced legislation in the 114th Congress that would ease U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba. These bills span a broad range of approaches, from a narrow focus on removing the ban on providing private financing and credit for the sale of agricultural goods to Cuba to far broader legislative initiatives that seek to lift the Cuban embargo altogether.

Introduction

Amid more than a half a century of antagonistic political relations between the United States and Cuba during which commercial ties were largely severed, U.S. exports of agricultural products to the island nation currently stand out as one of the few points of engagement between the two countries, if to a limited degree. U.S. exports of medicine and medical products is the other product category for which the U.S. government has eased its long-standing embargo on trade with Cuba. In a major diplomatic initiative, President Obama announced in December 2014 a significant shift in relations with Cuba with the goal of transitioning from a decades-long policy of sanctions that were designed to isolate Cuba toward a more normal bilateral relationship.

To advance the goal of normalizing relations with Cuba, the President announced a series of actions designed to move the two nations closer to this objective. These included reestablishing diplomatic relations; reviewing the State Department's designation of Cuba as a state sponsor of international terrorism; and providing limited openings for increasing travel, and for expanding commerce and the flow of information. In May 2015, the State Department removed Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, and on July 20, 2015, the United States and Cuba reestablished diplomatic relations and reopened embassies in their respective capitals. In March 2016, President Obama visited Cuba, marking the first visit by a U.S. President in almost 90 years. While these actions are tangible steps in the direction of a more normal relationship with Cuba and will ease the embargo in some areas, the majority of economic restrictions first imposed on Cuba in 1962 remain in place.1

This report reviews the current state of agricultural trade between the United States and Cuba, identifies key impediments to expanding bilateral trade in agricultural products, identifies key provisions in the law to which these obstacles are anchored, and considers the potential consequences for trade in agricultural goods in the event that the current thaw in diplomatic relations was to be extended more broadly so that bilateral trade was returned to a more normal footing. It also summarizes several of the bills introduced in the 114th Congress that propose to remove specific restrictions that impede trade in agricultural goods or that seek to lift the embargo on Cuba entirely.

Background and Perspective

Relations between the United States and Cuba deteriorated sharply, and then decisively, in the early 1960s following a series of dramatic events that recast the U.S.-Cuba relationship along antagonistic lines. Chief among these events were Fidel Castro's action in the early 1960s to build a repressive communist regime and move Cuba toward close relations with the Soviet Union; the expropriation of U.S. economic assets on the island nation located a mere 90 miles from Florida; U.S. covert operations to overthrow the Castro regime in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961; and the subsequent confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union over the Kremlin's attempt to install offensive nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962.

From Embargo and Sanctions to a Window for Farm Exports

In response to these events, President Kennedy imposed an embargo on trade with Cuba in 1962. The trade embargo was subsequently expanded—to prohibit most financial transactions and to freeze Cuban government assets in the United States. The web of U.S. sanctions on Cuba was strengthened in subsequent years and was also broadened to include various democracy-building measures with the enactment of additional laws, including the Cuban Democracy Act (CDA) of 1992 (P.L. 102-484) and the Cuban Liberty and Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-114), the latter frequently referred to as Helms/Burton legislation. In 2000, with passage of P.L. 106-387, the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (TSRA), Congress opened the door to U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba, but with restrictions on credit and financing.

Obstacles Impeding U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

The U.S. sanctions regime against Cuba has been tweaked in various ways in the years since TSRA was enacted, but alterations have been mostly at the edges, and this continues to be the case. Notwithstanding the new diplomatic opening to Cuba that President Obama unveiled late in 2014 in tandem with his expressed desire to move toward a more normal relationship with Cuba, key restrictions on economic relations with Cuba persist. Among the plethora of restrictions that remain in place, those frequently identified as suppressing trade in U.S. products to Cuba include the following:

- a prohibition on the provision of credit and financing for U.S. exports;

- denial of access to government programs and commercial facilities that otherwise would be available to promote and facilitate U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba;

- the ban on general U.S. tourism to Cuba; and

- a general ban on U.S. imports of goods from Cuba, with a recently introduced exception for goods produced by Cuban entrepreneurs.

Subsequently, the Obama Administration rescinded Cuba's designation as a state sponsor of terrorism in May 2015. Among a number of other actions taken to ease the embargo on Cuba, in 2015 and early 2016 the Obama Administration issued a policy of general approval for the export to Cuba of certain additional categories of goods and followed this up in January 2016 by permitting U.S. private export financing of these goods. But agricultural products continue to be excluded from private U.S. financing due to TSRA.

USDA Identifies Key Barriers to Expanded Agriculture Exports to Cuba

That significant barriers continue to restrict the potential for U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba was acknowledged by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in April 2015 testimony before the Senate Agriculture Committee. USDA asserted that if the embargo were removed, the United States could become "a major trading partner with Cuba," considering that Cuba imports around 80% of its food and that U.S. exporters enjoy significant logistical advantages over their major export competitors in Brazil and Europe.2 But USDA contends that these potential advantages are more than offset by a number of policies governing food and agricultural exports to Cuba, pointing to the prohibition on any U.S. government export assistance under TSRA, such as credit guarantees and market promotion programs, as one. Among impediments to expanding U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba that are not governed by the embargo, USDA cited Cuba's limited supply of foreign exchange and its requirement that all U.S. imports be funneled through Cuba's state corporation, Alimport—a requirement that is not imposed on all of Cuba's suppliers.

Subsequently, in a report of June 2015 on the potential for U.S.-Cuba agricultural trade, USDA's Economic Research Service cited restrictions imposed by TSRA on the terms of payments and financing as a "major inhibitor of U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba."3 Under TSRA, payment or financing terms are limited to either cash in advance or financing by third-country financial institutions, with the latter being a more laborious process than making a conventional payment directly from the buyer's financial institution in Cuba to the seller's financial institution in the United States. Following President Obama's "normalization" initiative in late 2014, the U.S. Treasury altered its interpretation of "cash in advance" from one that required cash payment before the shipment of goods from a U.S. port of departure to one that requires cash payment before transfer of title. Moreover, U.S. institutions also were allowed to open correspondent accounts at Cuban financial institutions. Still, in its Cuba report of June 2015, USDA concludes that lacking the ability to extend credit to Cuban buyers places U.S. agricultural exporters at a competitive disadvantage in relation to other exporting countries.

U.S. Agricultural Trade with Cuba over the Years

Prior to the Cuban revolution in 1959 that brought Castro to power and triggered the deterioration in U.S.-Cuban relations, the United States and Cuba conducted a brisk trade in agricultural products. During the three fiscal years before the revolution—FY1956-1958—Cuba ranked as the ninth largest market for U.S. agricultural exports and the second largest supplier of U.S. agricultural imports, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). In a report issued in June 2015, the agency notes that rice, lard, pork, and wheat flour led the list of U.S. farm exports to Cuba in value terms, with Cuba ranking as the largest foreign market for U.S. long-grain rice. Cane sugar, molasses, tobacco, and coffee topped the list of U.S. agricultural imports from Cuba during that period.4 With the advent of the Castro regime and the imposition of U.S. sanctions, U.S. agricultural trade with Cuba ground to a halt in the early 1960s.

|

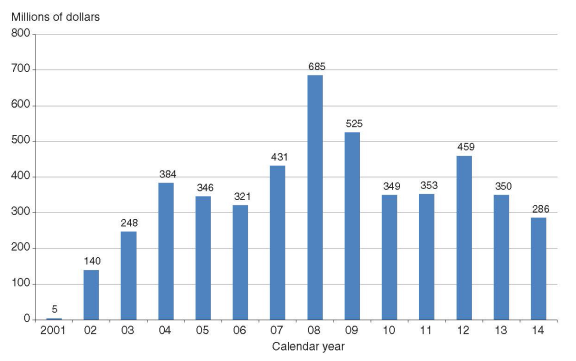

Figure 1. U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba 2001-2014 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. |

Trade in farm products remained at a standstill until Congress enacted the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-387), or TSRA, which authorized certain sales of food, medicines, and medical equipment to a number of countries, including Cuba. TSRA did not change the general ban on imports from Cuba, including agricultural products, and it added prohibitions on extending credit to facilitate agricultural sales to Cuba and on providing any U.S. government support for exports to Cuba. Notwithstanding these disadvantages, U.S. agricultural exporters quickly established a foothold in Cuba, with export sales reaching a peak of $685 million in calendar year (CY) 2008 in the aftermath of several hurricanes and tropical storms (Figure 1), representing 0.6% of total U.S. agricultural exports of $114.8 billion that year.

The level of U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba has trended lower since 2008, averaging $365 million a year during the most recent three calendar years, from 2012 to 2014, or about 0.25% of average U.S. agricultural exports to the world of $145.4 billion over this period. Most recently, U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba dipped to $286 million in CY2014. A parallel trend is that U.S. exports to Cuba have become increasingly concentrated in a few commodities, with chicken meat (leg quarters), corn, soybean meal, and soybeans accounting for 84% of the total between 2012 and 2014 (Table 1).

A number of close observers have suggested the decline in U.S. food and agricultural exports to Cuba in recent years is likely the product of several factors, among which are a preference within the Cuban government for diversifying its supplier network; an effort to establish closer relations with certain allies, such as China and Vietnam; and the availability of credit offered by some non-U.S. suppliers that U.S. competitors are prevented from providing under the U.S. trade sanctions regime.5 Concerning the role of credit, USDA asserts that "U.S. restrictions on extending credit to Cuban buyers have made it harder for U.S. agricultural exporters to sell a larger volume and broader variety of commodities to Cuba."6

|

Product |

Value, $1,000 |

Percent of Total |

|

Total Agricultural Exports |

365.3 |

100% |

|

Animals and Products |

161.2 |

|

|

Chicken meat |

148.9 |

41% |

|

Pork |

4.3 |

1.2% |

|

Grains and Feeds |

97.3 |

|

|

Corn |

72.9 |

20% |

|

Brewing/distilling dregs |

14.1 |

3.9% |

|

Mixed feeds |

10.3 |

2.8% |

|

Oilseeds and Products |

103.5 |

|

|

Soybean meal |

59.4 |

16.3% |

|

Soybeans |

44.1 |

12.1% |

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service.

Note: Totals do not add up because list is limited to major products.

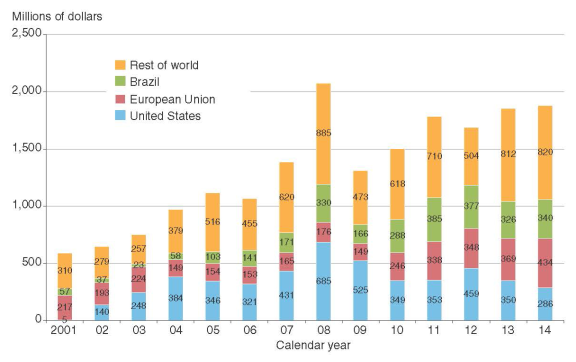

Figure 2 illustrates that as Cuba's agricultural imports from the United States have fallen in recent years, Cuba has increased its imports from the rest of the world, with the European Union and Brazil ranking as Cuba's largest suppliers in CY2014.

|

Figure 2. Cuba's Agricultural Imports by Origin, 2001-2014 2001-2014 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture. |

U.S. ITC Sees Potential for Expansion in U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

In December 2014, the Senate Committee on Finance requested that the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) conduct an investigation and issue a report on trends in Cuban imports of goods and services, including from the United States. The committee also requested that the agency provide an analysis of U.S. restrictions affecting Cuba's purchases. In its letter to ITC, the committee identified three areas of particular interest:

- 1. An overview of Cuba's imports of goods and services from 2005 to the present, to the extent possible, including identification of major supplying countries, products, and market segments;

- 2. A description of how U.S. restrictions on trade, including those relating to export financing terms and travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens, affect Cuban imports of U.S. goods and services; and

- 3. For sectors where the impact is likely to be significant, a qualitative and, to the extent possible, quantitative estimate of U.S. exports of goods and services to Cuba in the event that statutory, regulatory, or other trade restrictions on U.S. exports of goods and services as well as travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens are lifted.

The committee subsequently expanded its request to include7 the following elements:

- A qualitative analysis of existing Cuban non-tariff measures, Cuban institutional and infrastructural factors, and other Cuban barriers that would inhibit U.S. and non-U.S. firms in conducting business in and with Cuba, including restrictions on trade and investment; property rights and ownership; customs duties and procedures; sanitary and phytosanitary measures; state trading; protection of intellectual property rights; and infrastructure affecting telecommunications, port facilities, and the storage, transport, and distribution of goods;

- A qualitative analysis of any effects that such measures, factors, and barriers would have on U.S. exports of goods and services to Cuba in the event of changes to statutory, regulatory, or other trade restrictions on U.S. exports of goods and services to Cuba; and

- To the extent feasible, a quantitative analysis of the aggregate effects of Cuban tariff and non-tariff measures on the ability of U.S. and non-U.S. firms to conduct business in and with Cuba.

In response to the Finance Committee's request, ITC held a hearing in June 2015 to solicit the views of a range of experts and interested stakeholders, among which were food and agricultural interests. Overall, ITC concluded in its March 2016 report8 that U.S. agricultural exports could expand significantly if U.S. restrictions on trade with Cuba were removed. In particular, ITC observed that U.S. agricultural suppliers view the inability to offer credit and U.S. restrictions on travel to Cuba as key obstacles to increasing U.S. farm exports.

The ITC report makes a number of observations concerning U.S. farm and food exports to Cuba, including the following:

- 1. U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba have declined every year since 2009—in dollar terms, in market share, and in the variety of products shipped—whereas Cuba's overall agricultural imports have increased significantly over this period;

- 2. The United States is a competitive exporter of farm products, such as grains, meat, soybeans, and soybean products—products for which Cuba depends heavily on imports;

- 3. U.S. exporters enjoy advantages compared with major competitors, including the close proximity of U.S. ports to Cuba and lower shipping costs, which would allow them to be highly price competitive on certain agricultural products if U.S. travel and financing restrictions were lifted;

- 4. It is unclear whether lifting U.S. restrictions would lead the Cuban government to change its requirement that U.S. agricultural products be imported exclusively by the state trading agency, Alimport;

- 5. The potential for increasing U.S. exports could be tempered by Cuba's desire to diversify its supplier network to prevent it from becoming overly dependent on one country, particularly the United States; and

- 6. Other important factors in determining any expansion in U.S. agricultural exports would include the purchasing power of the Cuban economy, the availability of hard foreign currency, and the extent to which Cuba succeeds in its policy of import substitution through increases in agricultural production.

The ITC report also provides an analysis of potential commodity-specific effects of removing U.S. restrictions on trade with Cuba. A summary of its conclusions is included in Table 2. Overall, ITC concludes that if U.S. restriction on trade with Cuba were to be lifted, exports of the agricultural commodities listed in Table 2 could increase by 155% within five years to a total of about $800 million from a 2010-2013 average of just over $300 million.

|

Commodity Group |

ITC Outlook |

|

Wheat |

Sales could expand to $75 million within several years, compared with zero since 2012, and eventually exceeding $150 million. |

|

Rice |

U.S. exports (zero since 2009) could capture 30% of the market, or $60 million, within two years, rising to one-half of the market within five years and three-quarters within 10 years. |

|

Corn |

Sales could exceed previous levels of late 2000s of $100-$200 million, reflecting U.S. logistical advantages versus major foreign competitors. |

|

Soybeans and Soybean Products |

Exports of soybeans and soybean meal could expand and soybean oil sales resume, reflecting U.S. price competitiveness and logistical advantages over competitors. |

|

Pulses |

Exports of pulses—zero since 2012—could resume for dry beans but would face stiff competition from China, which offers extended credit, and from Canadian beans. |

|

Poultry |

As the lead supplier of Cuba's top food import, U.S. sales gains could be limited short-term; longer term, transport cost advantages, rising incomes, and tourism could spur U.S. sales. |

|

Pork |

Pork is a small share of Cuba's food imports, but U.S. sales could increase from a low level, led initially by low-value cuts and variety meats, with higher-value cuts expanding over time. |

|

Beef |

Similar to pork in that beef represents under 1% of Cuba's food imports. Any U.S. sales would likely involve either lower-priced cuts for Cubans or higher-end cuts for tourists. |

|

Dairy |

Lower freight costs could facilitate a resumption of U.S. exports, likely led by milk powder, with potential for a broader range of products to fill 30% of Cuba's dairy imports by 2020. |

Source: ITC, "Overview of Cuban Imports of Goods and Services and Effects of U.S. Restrictions," Publication No. 4597, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4597.pdf.

A University of Florida economist raised an agriculture-specific word of caution in citing a number of potential concerns for Florida agriculture in the event the current ban on imports from Cuba were to be lifted, among which were subsidized competition from Cuban farmers—who pay no rent to the government for their land, among other subsidies—and the possibility that imported Cuban produce could introduce new pests and diseases into Florida agriculture.9

USDA Sees Potential Sizable Gains in Farm Exports to Cuba

In a separate analysis, USDA issued a report in June 2015 in which it assesses the potential for increased U.S. agricultural trade with Cuba. In its report, USDA points to several important similarities between Cuba and the Dominican Republic, including population size and per capita income in terms of purchasing power parity. Given these similarities, the report goes on to consider whether the Cuban market for U.S. agricultural exports, which averaged $365 million from 2012-2014, might have the potential to expand to a level closer to that of the Dominican Republic, which absorbed an average of $1.1 billion of U.S. agricultural products over the same three years. USDA cites Cuba's close geographic proximity to the United States as a potential advantage for U.S. food and agricultural product exports that could help to drive export gains. Another reason that the agency sees an opportunity to expand U.S. agricultural product exports to Cuba is that the U.S. share of the market in Cuba, at about 20%, is less than half the U.S. market share in the Dominican Republic.

A Possible Market Opportunity for U.S. Rice

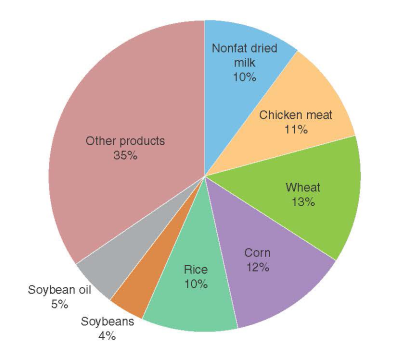

In terms of product mix, USDA, like the ITC report, sees the potential for U.S. rice to "regain a large share of Cuba's import market," if a normal trading relationship were to be established—but only if U.S. suppliers are allowed to provide competitive terms of credit. Among the advantages that favor U.S. rice compared with rice from current suppliers Vietnam and Brazil are the year-round availability of high-quality rice that Cuban consumers prefer, and transportation cost advantages. USDA suggests that exports of other U.S. commodities that have flagged in recent years, such as dry beans, wheat, and dry milk, could also rebound if normal trade relations were restored. In addition, USDA contends that tourist-oriented food service sales could support U.S. exports of cheese; yogurt; and higher value cuts of pork, poultry meat, and beef, particularly if restrictions on tourism to Cuba were relaxed. The agency also sees potential for expanded U.S. export sales of low-value cuts of pork, pork variety meats, chicken leg quarters, and milk powder, subject to further income growth within Cuba. These conclusions are largely reflected in the ITC report of March 2016. In recent years, Cuba has imported significant quantities of wheat, rice, and nonfat dried milk (Figure 3), but almost all of this trade accrued to non-U.S. suppliers.

|

Figure 3. Composition of Cuba's Agricultural Imports 2012-2014 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture. |

Research conducted by Texas A&M University's Center for North American Studies is consistent with USDA's analysis in concluding that U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba have the potential to climb to $1.2 billion within five years if restrictions on trade financing and travel were to be relaxed.10 As concerns the potential effects on individual U.S. states of easing the trade embargo against Cuba along these lines, Texas A&M named Arkansas, Texas, Minnesota, Louisiana, Missouri, and Nebraska as the states that would be expected to benefit most from an expected increase in agricultural exports. Among the factors most likely to influence the volume and mix of U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba, Texas A&M cited remittances to Cuba from Cuban-Americans in the United States and access to foreign exchange based on Cuba's exports—led by tourism, nickel/cobalt, pharmaceuticals, sugar, and tobacco products.

Florida Produce Could Face Heightened Competition from Cuban Exports

In addition to the potential for U.S. agricultural export gains from lifting certain trade restrictions with Cuba, or from removing the U.S. trade embargo completely, is the potential opportunity for Cuba to ship its agricultural products to the United States. A potential concern that could arise over U.S. imports of Cuban agricultural produce is that Florida farmers grow many of the same products during the same season as Cuba. Observers have pointed out that vegetables, citrus, sugar, and tropical fruit are among the overlapping product categories and concluded that if the prohibition on Cuban agricultural exports were removed, Florida growers could face increased competition."11 As previously noted, a corollary concern about such a policy change centers on the possibility that Florida growers could face subsidized competition: For example, some Cuban farms make no payments to the government for the use of their land. Concern about possible subsidized competition would be compounded if firms outside Cuba were to develop the island as a production platform for exporting produce to the United States, a development that some believe might alter the competitive structure of the U.S. winter fresh vegetable industry.12 Some also worry that opening the U.S. market to Cuba's produce could pose a threat to Florida agriculture by exposing it to new invasive pests and diseases.

Cuba's Agricultural Exports: Narrow in Scope, Limited in Quantity

Cuba's agricultural exports are limited, averaging $526 million per year during CY2012-2014, according to USDA, and are concentrated in a few products—sugar accounted for 89% of its farm exports during this period, followed by honey with about 4% of the total.13 China and the European Union are the leading markets for Cuba's agricultural exports. Although not considered agricultural products per se, cigars and cigarettes also were significant export earners during this period, averaging $222 million per year. USDA suggests that Cuba could exploit comparative advantages it has in the production of certain crops, such as tropical fruit, vegetables, sugar, and tobacco, to boost its agricultural exports to the United States if the embargo on its products were lifted.

|

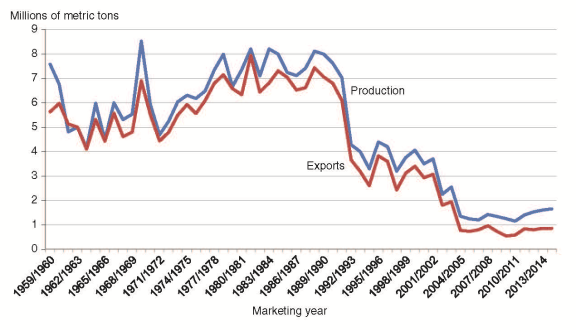

Figure 4. Cuba's Sugar Production and Exports Since the Revolution |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. |

Cuba was long known as a major producer and exporter of sugar, but its production and export trade have declined precipitously since the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, so its capacity to be a major influence on the world market has diminished sharply. USDA states that Cuban sugar production has fallen from between 6.5 million and 8.5 million metric tons during the 1980s, when it exported some 90% of its output, to an average of 1.6 million metric tons during the three most recent marketing years of 2012/2013 through 2014/2015 with exports averaging just below 1 million tons annually. (Figure 4).

Cuban Sugar Exports and the U.S. Market

Given Cuba's resource endowments and history as a major sugar producer, Cuba might expand its output and exports with additional investments. Although the United States is the world's largest sugar importer and Cuba was the largest foreign source of sugar for the U.S. market prior to the U.S. embargo, any post-embargo access to the U.S. sugar market would have to be negotiated. Any such access might well be quite limited in scope given the existing limitations on sugar imports under the U.S. sugar program via tariff rate quotas (TRQs), free-trade agreements, and through a 2014 export limitation agreement with Mexico.14 The United States currently provides low- or no-duty access to most of its supplier countries based on historical trade patterns as determined under an agreement struck under the auspices of the World Trade Organization.

In its June 2015 study, USDA concluded, "A more normal trading relationship with Cuba would likely result in the establishment of some U.S. sugar imports from Cuba, but at volumes much smaller than during the late 1950s." USDA cites a 2002 paper authored by two officials at the U.S. International Trade Commission that identifies six possible options for providing Cuba with access to the U.S. sugar market that the authors contend would be compliant with the existing multilateral trade agreements at the World Trade Organization (WTO):15

- allocate WTO quotas on a first-come, first-serve basis;

- auction sugar quotas;

- redistribute the tariff-rate quota (TRQ) among countries, including Cuba;

- increase the TRQ to accommodate Cuba;

- replace the existing TRQ with a simple tariff; and

- provide market access for sugar as part of a free trade agreement with Cuba.

Legislative Initiatives Aimed at Easing Restrictions on U.S. Agricultural Exports to Cuba

When President Obama announced his initiative to alter the course of U.S.-Cuba relations late last year, he indicated that he does not have the authority to end the embargo because it is codified in legislation. Under the LIBERTAD Act, the President would be required to end the trade embargo if he determines that Cuba has elected a government under free and fair elections and has met other criteria, among which are showing respect for basic civil liberties and human rights of Cuban citizens and Cuba moving to establish a free market economic system. Otherwise, congressional action would be required to end it, either by amending or repealing the LIBERTAD Act and other embargo-related statutes. The text box below identifies existing statutes that contain restrictions that are of particular importance for trade in food and agricultural products with Cuba.

Recognizing that U.S. farmers and exporters are competing for food and agricultural markets in Cuba under terms that place them at a distinct disadvantage compared with foreign competitors that are not subject to restrictions under the U.S. embargo, some Members of Congress have proposed legislation that would ease various elements of the U.S. economic embargo on Cuba, or repeal it entirely. A brief review of several of the legislative initiatives that address agricultural aspects of the trade embargo against Cuba follows.16

- Three bills would lift the overall embargo: H.R. 274 (Rush), H.R. 403 (Rangel), and H.R. 735 (Serrano).

- H.R. 635 (Rangel), among its various provisions, has the goal of facilitating the export of U.S. agricultural and medical exports to Cuba by permanently redefining the term "payment of cash in advance" to mean that payment is received before the transfer of title and release and control of the commodity to the purchaser; authorizing direct transfers between Cuban and U.S. financial institutions for products exported under the terms of TSRA; establishing an export promotion program for U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba; and prohibiting restrictions on travel to Cuba.

- S. 491 (Klobuchar) would remove various provisions of law restricting trade and other relations with Cuba, including certain restrictions in the CDA, the LIBERTAD Act, and TSRA that currently prohibit financing of agricultural sales to Cuba, U.S. export assistance for sales to Cuba including credit and guarantees, and the entry of Cuban goods into the United States.

- S. 1049 (Heitkamp) would amend TSRA to allow for the private financing of agricultural commodity sales to Cuba.

- S. 1543 (Moran)/H.R. 3238 (Emmer) would repeal or amend various provisions of law restricting trade and other relations with Cuba, including certain restrictions in the CDA, the LIBERTAD Act, and TSRA. It would repeal restrictions on private financing for Cuba in TSRA but continue to prohibit U.S. government foreign assistance or financial assistance, loans, loan guarantee, extension of credit, or other financing for export to Cuba, albeit with presidential waiver authority for national security or humanitarian reasons. Under the initiative, the federal government would be prohibited from expending any funds to promote trade with Cuba or develop markets in Cuba, although certain federal commodity research and promotion programs that are funded through mandatory assessments would be allowed.

- H.R. 3687 (Crawford) would amend TSRA to remove the prohibition on U.S. entities from making loans or extending credit to Cuba to facilitate sales of agricultural commodities. The bill would also permit U.S. government assistance in support of U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba—including the Market Access Program, the Export Credit Guarantee Program and the Foreign Market Development Cooperator Program and federal commodity promotion programs—provided the recipient of the assistance is not controlled by the Cuban government. It would also authorize investment for development of an agricultural business in Cuba so long as it is not controlled by the Cuban government or does not traffic in property of U.S. nationals confiscated by the Cuban government.

|

Select Statutory Provisions Relevant to U.S. Food and Agricultural Exports to Cuba

1. prohibiting U.S. aid to facilitate exports to Cuba; 2. limiting the means by which a U.S. person may finance the sale of agricultural products to Cuba to cash in advance or third-country financing.

|

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more on U.S. relations with Cuba see, CRS Report R43926, Cuba: Issues for the 114th Congress, by Mark P. Sullivan; CRS In Focus IF10045, Cuba: President Obama's New Policy Approach, by Mark P. Sullivan; CRS Report R43888, Cuba Sanctions: Legislative Restrictions Limiting the Normalization of Relations, by Dianne E. Rennack and Mark P. Sullivan; and CRS Report RL31139, Cuba: U.S. Restrictions on Travel and Remittances, by Mark P. Sullivan. |

| 2. |

Testimony of Michael T. Scuse on April 21, 2015, at http://www.ag.senate.gov/hearings/opportunities-and-challenges-for-agriculture-trade-with-cuba. |

| 3. |

U.S.-Cuba Agricultural Trade: Past, Present, and Possible Future, USDA, ERS, June 2015, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1856299/aes87.pdf. |

| 4. |

Ibid. |

| 5. |

See testimony of C. Parr Rosson III, Texas A&M University, on June 2, 2015, before the Senate Agriculture Committee at http://www.ag.senate.gov/hearings/opportunities-and-challenges-for-agriculture-trade-with-cuba; also, testimony of William A. Messina, Jr., University of Florida, on June 2, 2015, before the U.S. International Trade Commission at http://www.usitc.gov/press_room/spotlight/overview_cuban_imports_goods_and_services_and.htm. |

| 6. |

U.S.-Cuba Agricultural Trade: Past, Present, and Possible Future, USDA Economic Research Service, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1856299/aes87.pdf. |

| 7. |

ITC, "Overview of Cuban Imports of Goods and Services and Effects of U.S. Restrictions," 80 Federal Register 175, September 10, 2015, at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-09-10/pdf/2015-22697.pdf. |

| 8. |

ITC, "Overview of Cuban Imports of Goods and Services and Effects of U.S. Restrictions," Publication No. 4597, March 2016, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4597.pdf. |

| 9. |

Testimony of William A. Messina Jr., University of Florida, to the USITC on June 2, 2015, http://www.usitc.gov/press_room/spotlight/overview_cuban_imports_goods_and_services_and.htm. |

| 10. |

Testimony of Marco A. Palma, Texas A&M University, to USITC at http://www.usitc.gov/press_room/spotlight/overview_cuban_imports_goods_and_services_and.htm. |

| 11. |

See testimony of William A. Messina, Jr., University of Florida, before the USITC, June 2, 2015, at http://www.usitc.gov/press_room/spotlight/overview_cuban_imports_goods_and_services_and.htm. |

| 12. |

Ibid. |

| 13. |

U.S.-Cuba Agricultural Trade: Past, Present, and Possible Future, USDA, ERS, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1856299/aes87.pdf. |

| 14. |

For background on the structure and operation of the U.S. sugar program, see CRS In Focus IF10223, Fundamentals of the U.S. Sugar Program, by Mark A. McMinimy, and CRS Report R43998, U.S. Sugar Program Fundamentals, by Mark A. McMinimy. |

| 15. |

Normalizing Trade Relations with Cuba: GATT-Compliant Options for the Allocation of the U.S. Sugar Tariff-Rate Quota, Devry S. Boughner and Jonathan R. Coleman, U.S. International Trade Commission, at http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/23911/1/03010046.pdf. |

| 16. |

For a more comprehensive list of legislation introduced into the 114th Congress to remove trade sanctions on Cuba, see CRS Report R43926, Cuba: Issues for the 114th Congress, by Mark P. Sullivan. |