Democracy Promotion: An Objective of U.S. Foreign Assistance

Promoting democratic institutions, processes, and values has long been a U.S. foreign policy objective, though the priority given to this objective has been inconsistent. World events, competing priorities, and political change within the United States all shape the attention and resources provided to democracy promotion efforts and influence whether such efforts focus on supporting fair elections abroad, strengthening civil society, promoting rule of law and human rights, or other aspects of democracy promotion.

Proponents of democracy promotion often assert that such efforts are essential to global development and U.S. security because stable democracies tend to have better economic growth and stronger protection of human rights, and are less likely to go to war with one another. Critics contend that U.S. relations with foreign countries should focus exclusively on U.S. interests and stability in the world order. U.S. interest in global stability, regardless of the democratic nature of national political systems, could discourage U.S. support for democratic transitions—the implementation of which is uncertain and may lead to more, rather than less, instability.

Funding for democracy promotion assistance is deeply integrated into U.S. foreign policy institutions. More than $2 billion annually has been allocated from foreign assistance funds over the past decade for democracy promotion activities managed by the State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the National Endowment for Democracy, and other entities. Programs promoting good governance (characterized by participation, transparency, accountability, effectiveness, and equity), rule of law, and promotion of human rights have typically received the largest share of this funding in contrast to lower funding for programs to promote electoral processes and political competition. In recent years, increasing restrictions imposed by some foreign governments on civil society organizations have resulted in an increased emphasis in democracy promotion assistance for strengthening civil society.

Despite bipartisan support for the general concept of democracy promotion, policymakers in the 116th Congress may continue to question the consistency, effectiveness, and appropriateness of such foreign assistance. With President Trump indicating in various ways that promoting democracy and human rights are not top foreign policy priorities of his Administration, advocates in Congress may be challenged to find common ground with the Administration on this issue.

As part of its budget and oversight responsibilities, the 116th Congress may consider the impact of the Trump Administration’s FY2020 foreign assistance budget request for U.S. democracy promotion assistance, review the effectiveness of democracy promotion activities, evaluate the various channels available for democracy promotion, and consider where democracy promotion ranks among a wide range of foreign policy and budget priorities.

Democracy Promotion: An Objective of U.S. Foreign Assistance

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Definitions and Examples

- Authorities and Restrictions

- A History of U.S. Democracy Assistance

- Communism and the Cold War

- Post-Cold War Transition

- Post-9/11 Terrorist Attacks

- Recent Developments

- Democracy Promotion in Restrictive Environments

- Role of Federal Agencies and NED

- USAID

- Department of State

- National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

- Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)

- Other U.S. Bilateral Democracy Activities

- U.S. Support for Multilateral Organizations

- Democracy Promotion Funding

- Criticism of Democracy Promotion and Advocate Responses

- Issues for Congress

- Democracy Promotion in the Trump Administration

- Constrained Funding

- Effectiveness and Oversight

- Indirect vs. Direct Activity

- Relative Significance of Security, Trade, Human Rights

- Alternative Governance Models

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Governing Justly and Democratically, by Account, FY2015-FY2017, FY2018 Estimate, and FY2019 Request

- Table 2. Democracy Promotion Funding by Subcategory, FY2002-FY2019 Req.

- Table 3. 10-Year History of NED Grantee Allocations, FY2009-FY2018 est.

- Table 4. Recent Top Country Recipients of NED Funding

Summary

Promoting democratic institutions, processes, and values has long been a U.S. foreign policy objective, though the priority given to this objective has been inconsistent. World events, competing priorities, and political change within the United States all shape the attention and resources provided to democracy promotion efforts and influence whether such efforts focus on supporting fair elections abroad, strengthening civil society, promoting rule of law and human rights, or other aspects of democracy promotion.

Proponents of democracy promotion often assert that such efforts are essential to global development and U.S. security because stable democracies tend to have better economic growth and stronger protection of human rights, and are less likely to go to war with one another. Critics contend that U.S. relations with foreign countries should focus exclusively on U.S. interests and stability in the world order. U.S. interest in global stability, regardless of the democratic nature of national political systems, could discourage U.S. support for democratic transitions—the implementation of which is uncertain and may lead to more, rather than less, instability.

Funding for democracy promotion assistance is deeply integrated into U.S. foreign policy institutions. More than $2 billion annually has been allocated from foreign assistance funds over the past decade for democracy promotion activities managed by the State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the National Endowment for Democracy, and other entities. Programs promoting good governance (characterized by participation, transparency, accountability, effectiveness, and equity), rule of law, and promotion of human rights have typically received the largest share of this funding in contrast to lower funding for programs to promote electoral processes and political competition. In recent years, increasing restrictions imposed by some foreign governments on civil society organizations have resulted in an increased emphasis in democracy promotion assistance for strengthening civil society.

Despite bipartisan support for the general concept of democracy promotion, policymakers in the 116th Congress may continue to question the consistency, effectiveness, and appropriateness of such foreign assistance. With President Trump indicating in various ways that promoting democracy and human rights are not top foreign policy priorities of his Administration, advocates in Congress may be challenged to find common ground with the Administration on this issue.

As part of its budget and oversight responsibilities, the 116th Congress may consider the impact of the Trump Administration's FY2020 foreign assistance budget request for U.S. democracy promotion assistance, review the effectiveness of democracy promotion activities, evaluate the various channels available for democracy promotion, and consider where democracy promotion ranks among a wide range of foreign policy and budget priorities.

Introduction

Congress has long expressed interest in supporting democratic governance and related rights in other countries as a means of projecting American values, enhancing U.S. security, and promoting U.S. economic interests. More than $2 billion annually has been allocated from foreign assistance funds over the past decade for democracy promotion activities, including support for good governance (characterized by participation, transparency, accountability, effectiveness, and equity), rule of law, and promotion of human rights. While there has been bipartisan support for the general concept of democracy promotion assistance, policy debates in the 116th Congress may question the consistency, effectiveness, and focus of such foreign assistance. With President Trump indicating in various ways, including in proposed funding cuts for democracy promotion assistance, that promoting democracy and human rights are not top foreign policy priorities of his Administration, this debate has taken on new vigor.

The 116th Congress may consider the impact of the Trump Administration's requested foreign assistance spending cuts on U.S. democracy promotion assistance, review the effectiveness of democracy promotion activities, evaluate the various channels available for democracy promotion, and consider where democracy promotion ranks among a wide range of foreign policy and budget priorities. This report provides information on the history of democracy promotion as a foreign assistance objective, the role of the primary U.S. agencies administering such programs, and funding details and trends, as well as issues of potential relevance to Congress.1

Definitions and Examples

Democracy promotion may be defined in many ways, but it generally encompasses foreign policy activities intended to encourage the transition to or improvement of democracy in other countries. U.S. foreign aid to promote democracy may focus on electoral democracy, with a narrow emphasis on free and fair elections, or reflect a more liberal concept of democracy, which includes support for fundamental rights and standards that some argue make democracy meaningful.

U.S. democracy promotion assistance refers to U.S. program descriptions and funding levels for democracy promotion activities funded through the international affairs (function 150) budget, as reported under the Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD) objective in the annual International Affairs Congressional Budget Justification (CBJ) submitted by the Administration to Congress.2 The GJD objective (also sometimes called Democracy, Human Rights and Governance—DRG) is defined as including activities

to advance freedom and dignity by assisting governments and citizens to establish, consolidate and protect democratic institutions, processes, and values, including participatory and accountable governance, rule of law, authentic political competition, civil society, human rights, and the free flow of information.3

Congress has used a similar if somewhat more detailed definition in annual appropriations legislation, in which it frequently includes directives related to democracy assistance. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, defines "democracy programs" as

programs that support good governance, credible and competitive elections, freedom of expression, association, assembly, and religion, human rights, labor rights, independent media, and the rule of law, and that otherwise strengthen the capacity of democratic political parties, governments, nongovernmental organizations and institutions, and citizens to support the development of democratic states, and institutions that are responsive and accountable to citizens.4

The following examples of democracy promotion assistance reflect the broad range of activities that fall within this category:

- Election Support. Through the Support for Increased Electoral Participation (SIEP) project in Afghanistan, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has supported training for party poll watchers and candidate agents to effectively participate in election activities; implemented in-depth, multi-month civic education initiatives for women advocates and youth leaders on the electoral system, good governance, and the importance of political participation; and developed a national and local debate series between university students, among other activities.5

- Judicial Reform. In Jordan, USAID recently supported judicial reform by installing computer automation in Jordan's courts with a customized Arabic-language case management system; partnered with the Ministry of Education to launch a program to involve high school students in sessions on democracy, human rights, and elections; and promoted election reform by supporting the establishment of an Independent Election Commission and a national coalition of civil society organizations to campaign for improved election procedures and monitoring.6

- Law Enforcement Reform. After the 2014 revolution in Ukraine, Ukraine's Ministry of Internal Affairs sought to establish a new first-responder police force rather than rehire police officers from within an existing system that the Ukraine public widely saw as corrupt. The State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) worked with Ukraine to create a transparent and competitive recruitment process, including a public awareness campaign carried out by INL's implementing partners focused on inclusion of women, who made up 25% of applicants.7

- Municipal Governance. USAID's Office of Transition Initiatives is helping municipal governments in Colombia to execute recently signed peace accords and mitigate destabilizing tensions that threaten to derail the peace process. Activities include aligning municipal plans with accord priorities and disseminating best practices from public and private sector leaders in other regions emerging from conflict; training members of community action boards to manage resources and understand accord implications to ensure that implementation reflects local realities and priorities; and providing technical assistance to four government ministries to improve their capacity for accord implementation.8

- Human Rights and Rule of Law. In Ethiopia, National Endowment for Democracy (NED) grants have supported workshops for judicial and security officials and religious and civic leaders to improve understanding of human and democratic rights, assess the main challenges within their communities, and strengthen their ability to prevent rights violations in their individual and professional capacities. NED also supports workshops, forum discussions, and competitions among secondary school students in Addis Ababa to promote awareness of cultural factors that foster democratic development.9

Authorities and Restrictions

The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA), which is the basis of U.S. foreign assistance, cites "democratic participation" and "effective institutions of democratic governance" among the principles on which U.S. foreign assistance policy should be based.10 The FAA authorizes activities to promote good governance by combatting corruption and promoting transparency and accountability, and conditions some assistance on compliance with human rights standards.11 The law has also been amended over the years to add more explicit democracy promotion authorization for specific regions through legislation such as the Central America Democracy, Peace, and Development Initiative (FAA §461; 22 U.S.C. 2271), the Support for East European Democracy (SEED) Act of 1989 (22 U.S.C. 5401 et seq.), and the FREEDOM Support Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-511; 22 U.S.C. 2295). In addition, State Department democracy activities are guided by the various authorities compiled in the U.S. Code chapter on Advancing Democratic Values (22 U.S.C. CHAPTER 89 §8211-12),12 and NED activities are authorized through the 1983 National Endowment for Democracy Act (P.L. 98-164; 22 U.S.C. 4411-4416). As with many foreign assistance programs, authorizations related to democracy promotion may have expired, but annual appropriations language designating funds for this purpose is used by Congress in lieu of new authorizing legislation.

Democracy promotion assistance may generally be implemented "notwithstanding" other provisions of law that otherwise restrict foreign assistance,13 allowing it to be implemented in countries where other types of foreign assistance may by prohibited. There are laws and related agency policies, however, that specifically restrict the scope of democracy assistance activities. The FAA section authorizing development assistance for human rights promotion, for example, states that "none of these funds may be used, directly or indirectly, to influence the outcome of any election in any country."14 Similarly, USAID's Political Party Assistance Policy states that such assistance must support representative, multiparty systems and not seek to determine election outcomes.15 NED is also prohibited by provisions in its authorization from using funds for partisan political purposes, including funding for national party operations and support for specific candidates.16

A History of U.S. Democracy Assistance

Resources and attention to U.S. democracy promotion assistance have varied among Administrations and Congresses—with other interests, including U.S. security concerns, variously bolstering and competing with democracy promotion objectives.

Communism and the Cold War

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States supported democratization efforts in Germany and Japan, but also supported the overthrow of democratically elected regimes in Iran and Guatemala. As one scholar described this period, "stability took precedence over values and the fight against communism over the promotion of democracy."17 Stability was the primary foreign policy objective of the Lyndon B. Johnson, Nixon, and Ford Administrations, during which it was perceived that stable dictators were better for U.S. interests than countries in democratic transition, which may be susceptible to communism.

Democracy and human rights promotion gained traction in U.S. foreign policy in the 1970s. Congress took a lead on this issue, amending the Foreign Assistance Act in 1975 to restrict aid to the governments of countries that engaged in a consistent pattern of "gross violations" of human rights, as detailed in the legislation,18 and creating the position of Coordinator for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs at State in 1976.19 Elected during a Cold War thaw, President Carter emphasized democracy promotion as part of a broader human rights agenda, particularly with respect to Central and South America.20 With the support of Congress, the Carter Administration used foreign assistance to promote this human rights agenda primarily through use of negative conditionality—reducing aid to human rights violators, especially military aid to Latin America, in the early years of his Administration. Stability was still a concern, however, and President Carter sought reform within existing regimes, not the overthrow of totalitarians.21

Upon taking office in 1981, President Reagan immediately resumed the assistance to Latin America on which Carter had put conditions (this assistance was later sharply curbed by Congress) and focused on the existential threat it saw in communism rather than promoting democracy or human rights.22 However, the Reagan Administration adopted its own approach to democracy promotion that was distinct from its predecessor, distancing democracy from human rights, promoting democracy as part of an anticommunist agenda, and using democracy assistance, rather than punitive restrictions on aid, as a primary tool. In a famous 1982 speech before the United Kingdom Parliament, President Reagan stated

No, democracy is not a fragile flower. Still, it needs cultivating. If the rest of this century is to witness the gradual growth of freedom and democratic ideals, we must take action to assist the campaign for democracy.23

The Reagan Administration emphasized a structural rather than a rights-based view of democracy, emphasizing free and fair elections. It also called for the creation of a private but government-funded entity to support foreign prodemocracy organizations, which was established in 1983 as the National Endowment for Democracy and authorized by Congress as a federal grantee.24 Using a nonstate entity to support democracy promotion activities had the benefit of allowing the Administration simultaneously to support dictatorships and strengthen democratic successor movements and to replace once-covert programs with activities that were overt but arguably independent of U.S. policy.25 President Reagan is viewed by some as having solidified a bipartisan consensus within Congress and the American public that the United States had a strategic interest in promoting a transition to electoral democracy among its autocratic allies.26

Post-Cold War Transition

With the end of the Cold War and the dismantling of the Soviet Union, the focus of democracy promotion efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s shifted from Latin America to Eastern Europe and former Soviet states. The United States had a clear interest in promoting stability in this region, home to a vast nuclear arsenal and adjacent to Western European allies, and Congress and the George H. W. Bush Administration saw the opportunity to bring an end to communist expansion by supporting successful transitions to democratic governance and free markets. During this period, Congress enacted the Support for East European Democracy (SEED) Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-179; 22 U.S.C. 5401), primarily to assist Poland and Hungary but later expanded to assist a dozen countries, and the FREEDOM Support Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-511; 22 U.S.C. 2295), geared toward assisting the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. These efforts continued and expanded under the Clinton Administration, which faced a post-Cold War landscape and had to find a new focus around which to shape foreign policy.

President Clinton made democracy promotion one of the pillars of his foreign policy, titling his early security strategies "National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement," asserting that enlarging the community of democratic and free market nations served all U.S. strategic interests.27 The 1990s saw tremendous growth in democracy promotion activities, which experts have attributed to a low threat perception, a global wave of democratic transitions that provided many windows of opportunity, and no strong ideological rival to Western liberal democracy.28 The global spread of democracy seemed inevitable to many at the time, and democracy promotion and support became deeply integrated into the U.S. foreign policy structure.29 Clinton created a Democracy and Governance Office at USAID, and the Office of Transition Initiatives, to take advantage of opportunities for democracy in countries in transition. Congress, meanwhile, established the State Department's Human Rights and Democracy Fund in 1998, which State describes as its "venture capital fund for democracy and human rights."30

Post-9/11 Terrorist Attacks

U.S. democracy promotion activities took a new tone following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001. The George W. Bush Administration asserted that lack of democracy in the Arab world created a breeding ground for terrorism, and that democracy promotion could help contain Islamist extremism as it once had sought to contain Marxist rebels.31 The Administration established the Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI) to support democracy proponents in the Middle East, and established the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) as a model of foreign assistance conditioned on good governance, among other criteria. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice outlined her vision for "transformational diplomacy" in 2006, which aimed to elevate democracy-promotion activities inside countries and "to work with our many partners around the world to build and sustain democratic, well-governed states that will respond to the needs of their people and conduct themselves responsibly in the international system."32 Secretary Rice also established a Foreign Assistance Framework, still operational today, which includes Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD) as one of its key objectives.33

Notably, the Bush Administration, with the support of Congress, channeled significant resources toward efforts to establish democratic processes and institutions in Iraq and Afghanistan following on and concurrent with U.S. military activities in these countries. The lack of clear success with these broadly supported and highly resourced efforts led many to question not only the specific strategies employed, but the whole concept of foreign-led democracy promotion and whether it was an appropriate use of taxpayers' dollars. The Bush Administration "Freedom Agenda" was undermined, some argue, by the association of democracy promotion with military intervention, the use of counterterrorism measures that "undercut the symbolism of freedom," and free elections in the Middle East in which Islamist parties made gains, in conflict with U.S. interests.34

Some also assert that Western support for civil society groups behind the "color revolutions" in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine started a backlash against democracy promotion in Russia and elsewhere, leading many governments to restrict aid and civil society activities related to democracy and human rights, which they viewed as interfering with domestic politics.35 The later years of the Bush Administration saw a growing resistance to democracy promotion activities in many countries, often manifested in increasing restrictions on civil society and nongovernmental organizations affiliated with U.S. and other foreign entities, a trend which continues today.

The Obama Administration appeared to step back from the mixed George W. Bush legacy on democracy promotion when it took office in 2009,36 making efforts to improve relationships with nondemocratic governments in Iran, Russia, and elsewhere.37 When the 2011 "Arab Spring" gave hope for a new wave of democracy across the region, but also threatened U.S. security and economic interests, the Obama Administration and Congress provided democracy assistance where democratization seemed most promising and continued relations with authoritarian regimes that seemed stable, even though human rights was still an issue with some countries.38 At the same time, USAID expanded its democracy and governance efforts in 2012, putting new emphasis on program evaluation and learning in an effort to identify which type of democracy promotion activities are most effective and in what circumstances. USAID also released a new Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance in 2013.

The Trump Administration thus far has indicated a preference for dealing with foreign governments on the basis of U.S. economic and security interests, not necessarily levels of democratic governance, and commentators have suggested that the United States has become "an ambivalent actor on the global democratic stage."39 This is discussed further in the "Issues for Congress" section.

Recent Developments

Some analysts argue that democracy promotion as a U.S. foreign policy objective is at a crossroads.40 According to Freedom House, a total of 71 countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2017, compared with 35 that registered gains, marking the 12th consecutive year in which declines outnumbered improvements.41 Some question whether democracy promotion efforts make sense, given the instability, sectarian conflict, and anti-Western sentiment that political change has unleashed in some places.42 Political polarization, economic recession, a rise in extremism, populism, nationalism, and other challenges in the United States and Europe, some argue, have diminished the appeal of Western-style democracy.43

Others assert, however, that concerns about the declining appeal of democracy and a surge of authoritarianism are overstated.44 Democracy promotion has now been integrated and institutionalized in U.S. foreign policy over several successive Administrations, making a sharp policy change less likely.45 As one democracy expert asserts, while less attention may be paid to democracy promotion on the diplomatic level, "tearing out the many threads of democracy support from the institutional fabric of U.S. foreign policy would not be a simple or quick task."46

The notion that democratic expansion was inevitable has faded over the past decade; however, Congress continues to support democracy promotion aid, with a particular focus on human rights.

Democracy Promotion in Restrictive Environments

In recent years concern has grown about the viability of democracy promotion activities in countries with restrictive political environments, or "closed spaces." Many countries have placed restrictions on NGOs and civil society organizations that engage on a range of issues of public interest or concern in a country. For example, in 2014, CIVICUS, an international association of civil society groups, documented attacks on the fundamental civil society rights of free association, free assembly, and free expression in 96 countries. Another organization that tracks civil society issues, the International Center for the Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), stated that more than 60 laws, regulations, and other initiatives that restrict the influence of civil society organizations have been adopted around the world since 2015.47

While supporting civil society and democracy advocates in repressive countries may continue to be an element of U.S. foreign policy, programs in such environments can create tension when oversight and transparency requirements conflict with efforts to protect implementing partners and beneficiaries who may face significant risks from association with the United States. Programs in closed societies may also have significant diplomatic implications.48

In 2015, USAID issued guidance on programming in closed spaces, which it defined as nonhumanitarian programs in foreign countries in which the government (1) is politically repressive, (2) has explicitly rejected USAID assistance, or (3) has an adverse relationship with the United States such that USAID cannot partner with such government on development assistance or place direct hire staff in country.49 The guidance stated that all such programs would be reviewed with the intention of revising or discontinuing programs that require implementing organizations to go to "undue lengths" to minimize their association with USAID. It also stated that adequate transparency requires that program documents and briefings be unclassified, programmatic information be included in congressional notifications and online, and that implementing partners, including subcontractors and subgrantees, be fully aware of a project's USAID funding. It also noted that an initial review suggested that the great majority of USAID's portfolio in closed spaces is adequately balanced in this respect. In such cases, USAID "will continue to abide by existing Agency guidelines, including ensuring that the programs are not advancing an explicit political agenda beyond the promotion of basic principles of human rights and democratic governance, and operating with as much transparency a possible while protecting the security of implementing partners and beneficiaries."

The challenge of closed spaces, some argue, is a justification for U.S. support of NED, which as a nongovernmental organization may be better suited than USAID or State to work in politically restricted environments. As the organization explains on its website, "NED's NGO status allows it to work where there are no government-to-government relations and in other environments where it would be too complicated for the U.S. Government to work," and "NED's independence from the U.S. Government also allows it to work with many groups abroad who would hesitate to take funds from the U.S. Government."50 NED continued to support programs in Bolivia, for example, even after President Evo Morales expelled USAID and the U.S. ambassador to the country in 2013.

Role of Federal Agencies and NED

Democracy promotion falls within the purview of several agencies and organizations that manage foreign assistance activities. This section describes the role of the primary entities implementing democracy promotion funds.

USAID

USAID is the lead U.S. government manager of most foreign assistance programs. State Department and USAID share primary responsibilities for democracy promotion and human rights assistance. Programs are generally designed, managed, and monitored by USAID officials at the mission level, using nongovernmental partners for implementation. These activities are integrated into the broader development strategy for each country and may be closely linked with U.S. assistance in health, education, economic growth, and other development sectors.

Democracy promotion activities of the missions are supported in USAID's Washington office by the Center for Excellence on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance (DRG, established in 2012 to replace the Office of Democracy and Governance, which was established in 1985), within the Bureau of Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance (DCHA). DRG is the hub of USAID democracy promotion and focuses on advancing policy changes, working with field missions to develop and evaluate programs, and sponsoring research to develop best practices. The establishment of DRG in 2012 coincided with a doubling of staff resources and the addition of new divisions focused on human rights, learning, and integration of democracy promotion elements throughout USAID programs. DRG produced the 2013 USAID Strategy on Democracy, Human Rights and Governance, which guides USAID programs at the country and global level.

The Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI), established in 1994, also plays a significant role in USAID's democracy promotion efforts. The office was created to offer flexible, rapid response peace and democracy promotion assistance in countries in political crisis. In contrast with the ongoing DRG work in most countries, OTI programs are intended to be short-term, usually two to five years. The office is staffed primarily by personal service contractors, allowing it to expand and contract quickly, as well as standing contracts allowing for rapid procurement. OTI's niche is situations in which an opportunity for political change arises in a country of strategic significance to the United States and where other entities, including DRG, are not able to engage due to lack of presence or time pressure.51 As of early 2018, OTI was operating in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, northern Cameroon, Chad, Colombia, Honduras, Libya, Macedonia, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Ukraine.52

Department of State

The State Department democracy promotion activities complement those of USAID. State implements programs to advance democracy, good governance, and human rights around the world primarily through its Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL). DRL programs generally differ from those of USAID in two ways. First, they are focused on short-term or emergency assistance, rather than sustained programming. Second, DRL primarily serves as a Washington, DC-based grant-making entity, providing funds to U.S. nonprofit organizations involved in promoting human rights and democracy, as well as religious freedom, labor rights, transitional justice, and Internet freedom. DRL is not active at the embassy level, but it monitors grantee performance through annual reports and site visits. The bureau addresses human rights and democracy primarily through its Human Rights and Democracy Fund, which targets support to international and local NGOs to build demand for accountable, rights-respecting governance and rule of law. DRL works primarily in countries with closed societies and little political will to reform, as well as countries where USAID does not operate. It also maintains public-private partnerships that address gender-based violence, anticorruption, and embattled civil society organizations. The bureau is under the authority of the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights, a position created at the recommendation of the 2010 QDDR as a means of elevating efforts to address threats to civilians within State policies and operations.

Several other offices reporting to the Under Secretary do work related to democracy promotion. The International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) office, for example, supports anticorruption, law enforcement, and justice sector strengthening activities that may be part of democracy promotion efforts. INL advances the rule of law and human rights primarily through support to criminal justice institutions such as ministries of justice to promote accountable, rights-respecting institutions. This complements INL's work with civilian law enforcement that emphasizes the importance of security provision that respects human rights.

Regional and functional bureaus within the State Department also program and manage DRG activities, or have programs that contribute to furthering DRG efforts, such as programming on atrocity prevention and countering violent extremism conducted by the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO).

In addition, State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA) manages exchange and information programs that often have democracy promotion elements.

National Endowment for Democracy (NED)

The NED, established in 1983, is a Washington, DC-based private nonprofit organization that is funded almost exclusively through annual direct appropriations and designated State Department funds. Much like the State Department's DRL, NED does not design or carry out its own programs, but rather provides grants to organizations involved in human rights and democracy promotion. About 40%-50% of NED grants are awarded in equal amounts to its four affiliated organizations—International Republican Institute, National Democratic Institute, the American Center for International Labor Solidarity, and the Center for International Private Enterprise—while the rest go to nongovernmental organizations indigenous to the countries in which the programs are implemented.

Because NED is not a government agency, it can support activities in places where USAID or other official entities are limited by law or diplomatic considerations. The organization's activities are generally viewed as more independent of U.S. foreign policy considerations than USAID or State democracy and human rights activities. NED grants are reviewed and approved or rejected on a case-by-case basis by the NED board of directors. Program areas funded by NED include freedom of information, political processes, democratic ideas and values, strengthening political institutions, accountability, human rights, rule of law, civic education, NGO strengthening, freedom of association, developing market economy, and conflict resolution. NED reports annually to Congress on its activities, and reports to State quarterly on the use of funds it receives from State.

Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)

MCC was establish in 2004 to implement foreign assistance compacts (five-year assistance contracts) in close partnership with countries that have been selected based on their scores on a variety of indicators suggesting competent and just governance. Human rights and democracy promotion activities are not usually part of MCC country compacts, which are designed to reduce poverty through economic growth. However, one could argue that the MCC selection process incentivizes and promotes democracy and human rights, as MCC compact eligibility depends in part on specific must-pass indicators related to civil liberties and political rights. MCC aims to hold its partners accountable for maintaining good democratic governance during their compact, and in cases where problems have emerged, MCC has suspended or terminated compact programs; the threat of losing an MCC program has created strong leverage for the U.S. government in policy promotion discussions. The MCC threshold program, until 2012, had a more direct role in democracy promotion—for example, the threshold program in Jordan focused on broadening public participation in the electoral process and increasing government accountability and transparency—but now does so only when the lack of democratic progress is shown to be a constraint to economic growth. Threshold programs do still often work to address specific policy issues that prevent compact eligibility, such as control of corruption.

Other U.S. Bilateral Democracy Activities

While the abovementioned agencies are the primary managers of U.S. democracy assistance, other U.S. government entities play a role as well. The Department of Justice implements international programs on rule of law and administration of justice (with State Department funding). The Department of Labor's worker rights activities extend internationally. Various Department of Defense programs include respect for human rights and the subordination of military to civilian authority as part of military training or civil affairs activities. International broadcasting activities overseen by the Broadcasting Board of Governors, such as Voice of America broadcasting and Radio Martì broadcasts to Cuba, have a strong democracy promotion element. Aside from NED, there are a few smaller nonprofit organizations that receive direct annual appropriations, such as The Asia Foundation and the U.S. Institute of Peace, whose programs include elements of democracy promotion. It is difficult to determine how much is spent on these democracy promotion activities, as the agencies do not necessarily categorize and report them as a discrete type of activity. U.S. intelligence agencies also may participate in activities that could be considered democracy promotion, but information on these activities is not publicly available.

U.S. Support for Multilateral Organizations

In addition to bilateral democracy and human rights promotion activities, the United States supports multilateral institutions and organizations that are active in this field. These include the United Nations (U.N.) Development Program, the U.N. Democracy Fund,53 the Community of Democracies, and Freedom House, as well as the World Bank, the Organization of American States (OAS), and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Some of these organizations, such as the OAS, explicitly support democracy promotion, while others, such as the World Bank, focus on good governance, which it defines in ways that overlap significantly with standard features of democracy promotion. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, multilateral donors committed $17.47 billion in official development assistance for governance and civil society development programs in 2016, though data on actual disbursements, which may be lower, are not available.54

Democracy Promotion Funding

In recent years, 95%-99% of U.S. democracy promotion assistance has been funded within the Department of State and USAID budgets, with 11 other agencies providing the rest.55 Funding for U.S. democracy promotion activities is channeled primarily through the Economic Support Fund (ESF), International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), Democracy Fund (DF), Development Assistance (DA), Assistance to Europe, Eurasia, and Central Asia (AEECA), Transition Initiatives (TI), and National Endowment for Democracy (NED) accounts within the annual State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations bill. Congress typically includes a provision in annual appropriations56 directing that a certain amount of funds in the bill be used for "democracy programs," but allocation by account is largely unspecified in legislation. While the NED and DF accounts are focused on democracy promotion, the ESF, DA, INL, and AEECA accounts support a wide range of activities, and the proportion of these accounts allocated to democracy promotion activities is not known until Administration reporting after the fact. Table 1 shows funding categorized by Administrations as supporting the aid objective of Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD) from FY2015 through the FY2019 request, broken out by State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations account. FY2018 account allocations for this objective are not yet available.

Table 1. Governing Justly and Democratically, by Account, FY2015-FY2017, FY2018 Estimate, and FY2019 Request

(current $ in millions)

|

FY2015 Actual |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 Req. |

||||||

|

TOTAL |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Assistance to Europe, Eurasia & Central Asia (AEECA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Democracy Fund/Other (see note below) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Development Assistance (DA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Economic Support Fund (ESF)/ESDF |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

International Narcotics & Law Enforcement Affairs (INCLE) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

International Organizations & Programs (IO&P) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Transition Initiatives |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019 International Affairs Congressional Budget Justifications.

Notes: In the FY2019 request, the DA, AEECA, Democracy Fund, and IO&P accounts are combined with ESF to create a single Economic Support and Development Fund, the total of which is listed in the FY2019 column as ESF. FY2016 allocations group Transition Initiatives, Democracy Fund, and AEECA funds together under the category "Other." FY2018 appropriations account allocations for this objective are not yet available, but total funding for democracy promotion from these accounts is specified in the FY2018 appropriations legislation.

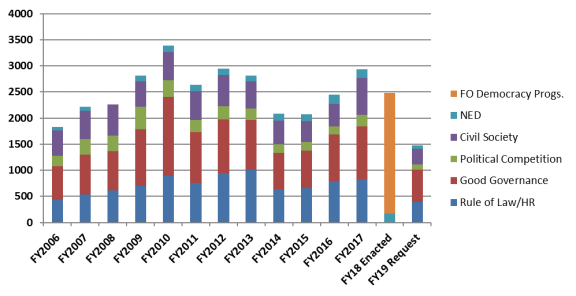

Since establishment of the Foreign Assistance Framework in 2006, Administrations have tracked both requested and obligated foreign assistance funds using a framework that categorizes funding across appropriations accounts into four subcomponents of the Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD) objective: Civil Society, Political Competition, Good Governance, and Rule of Law/Human Rights. Prior to that time, funding was reported under the general heading, Government & Civil Society. Figure 1 and Table 2 show funding levels for these reporting categories from FY2002 through the FY2019 request. FY2018 data are only currently available in total, not by sub-objective.

"Good governance" and "rule of law/human rights" have generally been the highest-funded subcategories of democracy promotion assistance over the past decade, accounting for 35% and 32%, respectively, of democracy promotion aid in FY2015 (Figure 1 and Table 2). "Political competition" has consistently been the lowest-funded subcategory within the GJD framework, representing less than 8% of democracy promotion funding in FY2015. NED funding, which is not included in GJD reporting, has comprised between 3%-7% of annual democracy promotion assistance each year since FY2002.

|

Figure 1. Democracy Promotion Funding by Subcategory, FY2006-FY2019 Req. (current $, in millions) |

|

|

Source: FY2002-FY2005 data reflect Government & Civil Society Sector funding obligations for USAID, State, and MCC from the USAID Data Query Page. FY2006-FY20017 and FY2019 request data are "actual" from annual International Affairs Congressional Budget Justifications; FY2018 enacted data are from P.L. 115-141. P.L. 115-31. Notes: The current Foreign Assistance Framework, which established the reporting categories for Democracy and Governance assistance used here, was established in FY2006. Data from prior years are reported in the general sector category of "Government & Civil Society." FY2018 funding is not yet available by subcategory. |

The Trump Administration budget request for FY2018 includes $1,689 million for overall democracy promotion assistance, which is about a 32% cut from the enacted FY2017 funding level. This includes $1,595 million for GJD activities and $107 million for NED. The proposed reductions are consistent with proposed cuts to foreign assistance funding as a whole in the FY2018 budget proposal, and so do not necessarily suggest that democracy promotion is a greater or lesser priority for the Trump Administration relative to other foreign assistance sectors. Within subobjectives, the request shows a shift in favor of good governance activities (more than 50% of the GJD request, compared to 40% in FY2016) and away from rule of law and human rights activities (27% of the FY2018 request comparted to 35% of the FY2016 funding).

|

FY03 |

FY04 |

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

|

|

Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD), Total |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

1,758 |

2,141 |

2,259 |

2,702 |

3,269 |

2,517 |

|

Rule of Law/Human Rights |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

437 |

532 |

608 |

699 |

888 |

758 |

|

Good Governance |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

638 |

763 |

762 |

1,088 |

1,518 |

974 |

|

Political Competition |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

203 |

305 |

295 |

433 |

321 |

231 |

|

Civil Society |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

480 |

541 |

593 |

482 |

543 |

554 |

|

National Endowment for Democracy (NED) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

74 |

74 |

[99.19]a |

115 |

118 |

118 |

|

GJD+ NED (FY2006-present) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

1,832 |

2,215 |

2,259 |

2,817 |

3,387 |

2,635 |

|

Government/Civil Society (pre-FY2006) |

1,297 |

2,925 |

3,115 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 Est. |

FY19 Req. |

||

|

Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD), Total |

2,826 |

2,701 |

1,952 |

1,934 |

2,273 |

2,769 |

2,309 |

1,413 |

|

|

Rule of Law/Human Rights |

940 |

1017 |

636 |

659 |

794 |

829 |

n.a. |

392 |

|

|

Good Governance |

1,037 |

942 |

690 |

716 |

886 |

1,014 |

n.a. |

616 |

|

|

Political Competition |

247 |

226 |

168 |

163 |

164 |

221 |

n.a. |

106 |

|

|

Civil Society |

603 |

516 |

458 |

396 |

429 |

705 |

n.a. |

299 |

|

|

National Endowment for Democracy (NED) |

118 |

112 |

135 |

135 |

170 |

170 |

170 |

67 |

|

|

GJD+ NED |

2,944 |

2,813 |

2,087 |

2,069 |

2,443 |

2,939 |

2,479 |

1,480 |

|

Source: FY2002-FY2005 reflect total "Government & Civil Society" sector funding obligations for USAID, State and MCC from the USAID Data Query Page. FY2006-FY2017 data are "actuals," and the FY2019 data are the requested amount, all from annual International Affairs Congressional Budget Justifications. FY2018 data are enacted levels specified in P.L. 115-141.

a. In FY2008, NED funding was appropriated through the Democracy Fund account and included in the GJD total.

The United States funds Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance programs across the globe (DRG obligations were reported in more than 70 countries in FY2017, excluding NED funding), but the majority of assistance funds are concentrated in a small group of countries and regional offices. In recent years, Afghanistan has been the top recipient ($302 million estimated for FY2017), along with the State Department's Western Hemisphere Regional Office ($235 million in FY2017). Other top GJD recipients in FY2017 include Syria ($161 million), Ukraine ($100 million), Mexico ($77 million), Colombia and Iraq ($66 million each) and Jordan ($63 million).

NED funding is provided annually through a NED appropriations account, which is in the State Operations and Related Accounts section of the SFOPS appropriation, and often not considered foreign assistance. Report language accompanying the NED appropriation typically calls for the account to be allocated in the customary manner to the core institutes, with a portion designated for discretionary grants. Country allocations for NED assistance are not specified in legislation but are publicly available through annual reports to Congress.

Table 3 provides a detailed breakdown of NED funding by primary grantee and discretionary grant funds over the past 10 years.

|

Grantee |

Fiscal Year |

|||||||||

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 est. |

|

|

Solidarity Center |

13.8 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

13.8 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

13.8 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

|

CIPE |

13.8 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

13.8 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

13.8 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

|

IRI |

13.8 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

13.8 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

13.8 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

|

NDI |

13.8 |

13.8 |

13.7 |

13.8 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

13.8 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

|

NED discretionary grants |

42.6 |

43.6 |

41.7 |

41.3 |

38.1 |

55.9 |

55.7 |

55.4 |

55.0 |

53.1 |

|

NED Mid-long term strategic threatsa |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

13.2 |

13.2 |

13.2 |

|

NED contingencya |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

7.0 |

7.0 |

7.0 |

Source: Email communication with NED, December 4, 2018.

Notes: These amounts do not equal NED's total appropriation because they do not include overhead costs or other NED DC-based activities like NED's fellowship programs, or activist networks such as the World Movement for Democracy.

a. In FY2016, FY2017, and FY2018 Congress provided additional funding to NED to address strategic threats facing democracy abroad. These funds are allocated for two funds: Mid-Long Term Strategic Threats and Contingency.

NED grants are often much smaller than the assistance levels provided through USAID and government agency programs. Top country recipients of NED funding in FY2017 and FY2018 follow in Table 4 below.

|

FY2017 |

FY2018 est. |

|

China, including Tibet ($7.0 million) Burma ($5.4 million) Russia ($5.0 million) Ukraine ($4.7 million) Cuba ($3.8 million) |

Russia ($6.3 million) Cuba ($5.8 million) China, including Tibet ($5.7 million) Burma ($5.6 million) Ukraine ($3.9 million) |

Source: Email communication with NED December 4, 2018.

Criticism of Democracy Promotion and Advocate Responses

Democracy promotion efforts have been met with a range of criticism, some specific to particular activities, but they generally fall into a few general themes. Below are key arguments made by critics, and corresponding responses by democracy promotion advocates.57

- Imposing American Values. Some argue that it is arrogant for the United States to assert that its form of liberal democracy, and accompanying values, should be held by all. Some go further to assert that this effort to reform the world in the U.S. image, as they see it, has helped to stoke the resentment that fuels terrorism. Proponents of democracy promotion counter that democracy and participatory government are not American concepts, but broadly held values, and U.S. activities are not imposed, but support organizations and individuals abroad who are fighting for these freedoms and seek help.

- Sovereignty. Foreign leaders who feel threatened by democracy promotion often argue that democracy promotion efforts, which may be viewed as interfering with local politics, are inappropriate interference with the domestic politics of a foreign country. This argument is often the basis for the efforts to restrict civil society organizations that promote democracy, sometimes with U.S. or other foreign funding. Critics of this argument counter that these leaders, if not selected through free and fair elections, lack the legitimacy to be the representative of sovereign people.

- Inconsistency. Democracy promotion sometimes conflicts with other foreign policy priorities, and critics argue that when the United States exerts pressure on some regimes for undemocratic practices while ignoring similar practices among strategic partners against terrorism, or major oil suppliers, the moral authority of the United States is undermined. Others assert that, as with any foreign intervention, it is appropriate and necessary for the United States to pick and choose situations in which the greatest opportunities for positive change exist.

- Ineffectiveness and Unintended Consequences. Recent democracy promotion efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq, and in several countries in the wake of the Arab Spring, have led some to conclude that these efforts are destined to fail because they attempt to induce social and structural changes in societies that U.S. policymakers do not fully understand. The results may not only be ineffective, but may have unintended consequences such as regional instability. Democracy promotion advocates argue that it is a mistake to focus on the Iraq and Afghanistan examples, which reflect the shortfalls of military intervention more than democracy promotion, and cite positive results in less publicized situations such as Colombia, Indonesia, Myanmar (Burma), Slovakia, and Tunisia.

Issues for Congress

Congress plays an important role in determining the shape, scope, and priorities of U.S. democracy assistance programs. Following are some issues Congress may consider as it carries out related legislative and oversight responsibilities.

Democracy Promotion in the Trump Administration

Many Members of Congress have expressed concern about actions by the Trump Administration that they perceive as undermining U.S. democracy promotion efforts. President Trump's frequent praise for authoritarian leaders, including Russia's Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un of North Korea, and Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, combined with intermittent criticism of democratic leaders and allies, have raised concern that the Administration is emboldening foreign nondemocratic behavior.58 Moreover, President Trump's statements valuing the U.S. economic relationship with Saudi Arabia over acute concerns about the Saudi Crown Prince's role in the October 2018 murder of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi have heightened this concern.59 At the same time, the Trump Administration has taken a hard line on some authoritarian leaders, with National Security Advisor John Bolton referring to Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua as a "troika of tyranny."60 Conflict between Congress and the Administration on whether, how and when the United States should promote democracy and condemn authoritarian regimes may be an issue throughout the 116th Congress.

Constrained Funding

For both FY2018 and FY2019, the Trump Administration proposed cuts to democracy promotion aid of more than 40% compared to prior year funding. The proposed funding cuts exceed those proposed by the Administration both years for foreign assistance programs as a whole, for which proposed cuts would average about 30%. The Administration has also indicated its intent to focus foreign assistance generally on countries of greatest strategic significance; this would not necessarily change democracy promotion allocations, which are already heavily concentrated in such countries. For FY2018, Congress did not enact cuts to the degree proposed by the Administration, but did reduce funding for democracy promotion assistance by 16% compared to FY2017. While a final appropriation for FY2019 has not yet been enacted, both the House and Senate committee-approved bills include slightly more funding for democracy promotion than they approved for FY2018, making Administration-requested funding reductions in FY2019 unlikely. Nevertheless, Congress may continue to scrutinize of the costs versus benefits of various democracy promotion activities and the foreign assistance budget, in general, if the Administration continues to call for significant foreign affairs budget cuts.

Effectiveness and Oversight

Most democracy promotion assistance is subject to the same monitoring and evaluation, auditing, and oversight as other foreign assistance, including the contracting, auditing, and reporting requirements of the State Department and USAID, review by agency Inspectors General, and investigations by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). As with other foreign assistance programs, tracking resources and monitoring outputs and contract performance for democracy aid is well-established practice, while evaluating program effectiveness remains challenging.61 Documenting the impact of democracy promotion activities may be particularly difficult because of the sometimes abstract objectives, political sensitivity, need for timely and flexible response in many situations, length of time to produce certain results (possibly generations), and potential backsliding that can occur in any country at any time.

A 2006 study commissioned by USAID to determine the effects of its democracy assistance programs between 1990 and 2003 found that even when controlling for a variety of other factors, USAID democracy and governance aid had "a significant positive impact on democracy, while all other U.S. and non-U.S. assistance variables are statistically insignificant."62 However, no comparable study of U.S. democracy assistance has been carried out in the past decade, even as much attention has been paid to disappointing results of U.S. democracy promotion aid in such strategically significant places as Egypt and Russia. USAID has stepped up efforts to evaluate its democracy and human rights programs in recent years, with an emphasis on learning which activities are most effective. Congress may wish to use its oversight authority to bring more attention or resources to examining the effectiveness of this type of assistance.

Indirect vs. Direct Activity

There are both advantages and disadvantages to implementing democracy assistance directly, through USAID, or indirectly through NED or multilateral entities. NED was established to make overt and accountable certain democracy promotion activities that had previously been largely covert; but it is structured to keep policymakers at arm's length, giving political cover on both ends, and to limit the ability of policymakers to control NED activities. Providing assistance through multilateral democracy promotion channels, such as the U.N. Democracy Fund, further limits the ability of U.S. policymakers to direct and oversee activities and ensure alignment with U.S. foreign policy priorities. At the same time, these indirect implementation channels are viewed by some as having more legitimacy precisely because they are removed from a specific foreign policy agenda inherent to direct U.S. government action.63 In some situations, affiliation with the United States can be detrimental or dangerous to implementing partners and create conflict between security measures and requirements for transparency and branding. Historically, less than 10% of annual U.S. democracy and human rights assistance has been allocated for NED and multilateral programs. As the 116th Congress considers policy and funding related to democracy promotion, Members may consider the merits and limitations of various aid channels and whether the current allocation of resources best meets policy objectives.

Relative Significance of Security, Trade, Human Rights

As the history of democracy promotion in U.S. foreign policy indicates, the emphasis placed on human rights and democracy at a given time or in a particular bilateral relationship depends significantly on competing security and economic interests (such as stabilizing a country or region with the potential of becoming a U.S. trading partner). As noted above, the Trump Administration has prioritized U.S. national security and economic gains as the focus of U.S. bilateral relationships, suggesting that democracy and human rights promotion are secondary issues when it comes to Administration negotiations with foreign governments. Congressional advocates of human rights, however, may push back on any move to bolster nondemocratic regimes in the name of security, or a view of democratic systems as representing a competitive disadvantage in global trade. As Congress considers the myriad interests at stake in various foreign policy decisions, it may weigh the importance of projecting democratic values against potentially conflicting security and economic interests, and the impact of those choices on U.S. global leadership.

Alternative Governance Models

Some experts argue that liberal democracy promotion was once effective because the United States was viewed by many around the world as exemplifying the type of government they would like to live under, but that the American "brand" has been tarnished by problems within American democracy.64 Furthermore, as new democracies struggle with economic and security challenges, as in Eastern Europe and Iraq, global perceptions of the relationship between democracy, peace, and prosperity have changed. While these challenges lead some to question ongoing U.S. efforts to promote democracy abroad, others assert that these activities are more important than ever because diminished U.S. leadership with respect to promoting democratic values could leave a void that other countries could fill, with detrimental consequences for the United States in the long term. China's system of authoritarian capitalism, in particular, is seen as a potential "post-democratic" model that appeals to many who prioritize stability and economic growth.65 As Congress and the Trump Administration deliberate on the appropriate role of democracy and human rights promotion within U.S. foreign policy, the implications of alternative models gaining prominence and legitimacy may be an important consideration.66

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The report focuses on U.S. foreign assistance activities, which are only part of U.S. democracy promotion activities. Others include diplomatic efforts, international broadcasting, international educational and cultural exchanges, economic sanctions, military aid, and other policy areas related to international engagement. See also CRS Report R45344, Global Trends in Democracy: Background, U.S. Policy, and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

The international affairs budget does not include Department of Defense programs that may be counted as democracy promotion aid in other data sources. |

| 3. |

CRS communication with Department of State's F Bureau, May 18, 2016. |

| 4. |

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, P.L. 115-141, Division K, §7032(c). |

| 5. |

For more information on this program, see https://www.usaid.gov/news-information/fact-sheets/support-increased-electoral-participation-afghanistan. |

| 6. |

For more information, see https://www.usaid.gov/jordan/democracy-human-rights-and-governance. |

| 7. |

For more information on this program, see https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/222034.pdf. |

| 8. |

For more information on this program, see https://www.usaid.gov/political-transition-initiatives/where-we-work/colombia. |

| 9. |

For more information on these programs, see http://www.ned.org/region/africa/ethiopia-2015/. |

| 10. |

The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (P.L. 87-195), §101 and §102. |

| 11. |

FAA, §116. |

| 12. |

This section codifies Title XXI of P.L. 110-53, Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007. |

| 13. |

For FY2018, this notwithstanding language is found in §7032(b) of P.L. 115-141, Division K. |

| 14. |

FAA, §116(e). |

| 15. |

USAID Political Party Assistance Policy, PD-ABY-359, September 2003, p. 1 |

| 16. |

22 U.S.C. 4414(a). |

| 17. |

Daniela Huber, Democracy Promotion in Foreign Policy, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005, p. 51. |

| 18. |

P.L. 94-161, the International Development and Food Assistance Act. |

| 19. |

The Ford Administration had created the Coordinator of Humanitarian Affairs position the year before, but Congress changed the title to add human rights and made the positon a presidential appointment subject to advice and consent of the Senate. For a history of the position, see https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/people/principalofficers/assistant-secretary-for-democracy-human-rights-labor-affairs. |

| 20. |

Huber, p. 67. |

| 21. |

President Carter reversed his human-rights oriented approach to Central America in his last year in office, after the fall of the U.S.-backed Somoza regime in Nicaragua, and started sending military aid, including lethal aid, to the government of El Salvador, a notable human rights violator. |

| 22. |

Congress, in the meantime, continued to promote a rights agenda in the early 1980s. When Reagan first proposed a candidate (Ernest Lefever) for Under Secretary for Human Rights who was overtly opposed to the human rights agenda, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee refused to recommend the nomination to the full Senate. |

| 23. |

President Ronald Reagan, speech before the U.K. Parliament at Westminster Palace, June 8, 1982. |

| 24. |

According to the history on the NED website, the Reagan Administration had originally proposed a larger democracy promotion initiative to be known as "Project Democracy" and coordinated directly by the United States Information Agency (USIA), but the Foreign Affairs Committee reported out an appropriations bill that did not include funding for "Project Democracy," making clear its preference for the nongovernmental Endowment concept, which the Administration then supported. Within Congress, a major point of contention with the legislation establishing NED was the funding of political party institutes, which the original authorization allowed but did not direct through earmarks. |

| 25. |

Robert Pee, "The Cold War and the Origins of U.S. Democracy Promotion," U.S. Studies Online, May 8, 2014; Anthony Fenton, "Bush, Obama and the Freedom Agenda," Foreign Policy In Focus, January 27, 2009. |

| 26. |

Mark Lagon, "Promoting Democracy: The Whys and Hows for the United States and the International Community," Council on Foreign Relations, February 2011. |

| 27. |

This title was used for the 1994, 1995, and 1996 strategies, available at http://nssarchive.us/. |

| 28. |

Thomas Carothers, "Democracy Aid at 25: Time to Choose," Journal of Democracy, January 13, 2015. |

| 29. |

See Francis Fukuyama, "The End of History?" The National Interest, Summer 1989. |

| 30. |

For more information, see the State/DRL home page at https://www.state.gov/j/drl/p/. |

| 31. |

Robert Pee, "War and the Origins of U.S. Democracy Promotion," U.S. Studies Online, May 8, 2014. |

| 32. |

Condoleezza Rice, testimony before Senate Foreign Relations Committee, February 14, 2006. |

| 33. |

Henrietta H. Fore, Acting Director of Foreign Assistance and Acting Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development, Testimony before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Washington, June 12, 2007. |

| 34. |

Mark Lagon, "Promoting Democracy: The Whys and Hows for the United States and the International Community," Council on Foreign Relations, February 2011. |

| 35. |

Thomas Carothers, "Democracy Aid at 25: Time to Choose," Journal of Democracy, January 13, 2015. |

| 36. |

Mark Lagon, "Promoting Democracy: The Whys and Hows for the United States and the International Community," Council on Foreign Relations, February 2011; Stephen M. Walt, "Why Is America So Bad at Promoting Democracy in Other Countries," Foreign Policy, April 25, 2016. |

| 37. |

Thomas Carothers, "Democracy Policy Under Obama: Revitalization or Retreat?" Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 11, 2012. |

| 38. |

Ibid. |

| 39. |

Thomas Carothers and Frances Z. Brown, "Can U.S. Democracy Policy Survive Trump?," Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 1, 2018. |

| 40. |

For more information and analysis on global democracy trends, see CRS Report R45344, Global Trends in Democracy: Background, U.S. Policy, and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 41. |

"Freedom in the World, 2018," Freedom House,, available at https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2018 |

| 42. |

Thomas Carothers, "Democracy Aid at 25: Time to Choose." |

| 43. |

Ibid.; Larry Diamond, "Democracy in Decline," Foreign Affairs, July/August 2016. |

| 44. |

Thomas Carothers, "Democracy is Not Dying," Foreign Affairs, April 11, 2017. |

| 45. |

Democracy promotion as a foreign policy objective has been articulated in every U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) issued since 1990, the 2010 and 2015 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Reviews (QDDR), the 2010 Presidential Policy Directive on Global Development (PPD-6), a joint State Department-USAID Strategic Goal, and the USAID Policy Framework. |

| 46. |

Thomas Carothers, "Prospects for U.S. Democracy Promotion Under Trump" Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 5, 2017. |

| 47. |

For additional examples of civil society restrictions see CRS Report R45344, Global Trends in Democracy: Background, U.S. Policy, and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 48. |

For more on this issue, see CRS Report R44458, Closing Space: Restrictions on Civil Society Around the World and U.S. Responses, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 49. |

The guidance document is available at https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/USAID%20Guidance%20on%20Programming%20in%20Closed%20Spaces%20Ident.pdf. Earlier USAID guidance from 2013 can be found at https://www.usaid.gov/democracy-human-rights-and-governance-strategy. |

| 50. |

See the NED website FAQ page: http://www.ned.org/about/faqs/. |

| 51. |

CRS conversation with OTI, April 6, 2017. |

| 52. |

See the OTI website, at https://www.usaid.gov/political-transition-initiatives/where-we-work. |

| 53. |

In FY2016, the U.S. contribution to UNDEF was $3 million. |

| 54. |

This information is from the OECD Data Query page (http://stats.oecd.org/qwids/), accessed on November 26, 2018. |

| 55. |

Calculations based on data provided by USAID's Economic Analysis and Data Services, Devtech Systems, Inc, on April 13, 2017. Other departments or agencies with funding for democracy promotion activities include the Departments of Defense, Treasury, the Interior, Justice, Labor, and Homeland Security; Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC); Army, Trade and Development Agency (TDA); Inter-American Foundation; and African Development Foundation. |

| 56. |

In the FY2016 bill (P.L. 114-113), Sec. 7032 states that "of the funds appropriated by this Act, not less than $2,308,517,000 shall be made available for democracy programs." |

| 57. |

For examples of article and essays that discuss these concerns, see Thomas Carothers, "Democracy Aid at 25: Time to Choose," Carnegie Endowment for National Peace, January 13, 2015, available at http://carnegieendowment.org/2015/01/13/democracy-aid-at-25-time-to-choose-pub-57701; Arch Paddington, "Countering the Critics of Democracy Promotion," Freedom House, October 23, 2013, available at https://freedomhouse.org/blog/countering-critics-democracy-promotion; Richard Youngs, "Misunderstanding the Maladies of Liberal Democracy Promotion," FRIDE Working Paper #106, January 2011, available at http://fride.org/download/WP106_Misunderstanding_maladies_of_liberal_democracy_promotion.pdf; "The Case for Offshore Balancing," by John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, Foreign Affairs, July/August 2016, available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing. |

| 58. |

See, for example, "Nine Notorious Dictators, Nine Shout-Outs from Donald Trump" by Krishnadev Calamur, The Atlantic, March 4, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/trump-xi-jinping-dictators/554810/; and "Trump pummels G-7 democratic allies but loves autocrats," by Trudy Rubin, The Philadelphia Enquirer, https://www.newsday.com/opinion/commentary/donald-trump-g-7-allies-russia-1.19130523. |

| 59. |

See, for example, "In Extraordinary Statement, Trump Stands with Saudis Despite Khashoggi Killing," by Mark Lander, The New York Times, November 20, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/20/world/middleeast/trump-saudi-khashoggi.html; and "McConnell Vows Congressional Response to 'Abhorrent' Khashoggi Slaying," by Tim Mak, National Public Radio, https://www.npr.org/2018/11/27/671266007/mcconnell-vows-congressional-response-to-abhorrent-khashoggi-murder. |

| 60. |

"Bolton promises to confront Latin America's Troika of Tyranny," by Josh Rogin, The Washington Post, November 1, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/bolton-promises-to-confront-latin-americas-troika-of-tyranny/2018/11/01/df57d3d2-ddf5-11e8-85df-7a6b4d25cfbb_story.html?utm_term=.fdb45cc9aa19. |

| 61. |

For more information on evaluation of foreign assistance generally, see CRS Report R42827, Does Foreign Aid Work? Efforts to Evaluate U.S. Foreign Assistance, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 62. |

Steven E. Finkel, et al., "Effects of U.S. Foreign Assistance on Democracy Building: Results of a Cross-National Quantitative Study," January 16, 2006. Available at http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnade694.pdf. |