Closing Space: Restrictions on Civil Society Around the World and U.S. Responses

Civil society organizations (CSOs) around the world are confronting ever stricter limitations on their ability to operate, a phenomenon often referred to “closing space” for civil society work. From restrictions on the types of funding they are allowed to receive to draconian registration requirements, the measures targeting CSOs are increasingly putting pressure on the entire civil society sector in certain countries. These restrictions are most commonly imposed by governments seeking to limit the influence of nongovernmental actors, though restrictions are also being imposed by a broad range of governments, including democratic allies. Increasing awareness of this phenomenon has elevated concerns among civil society advocates and some policymakers, including in Congress. Congress has also shaped U.S. policy toward civil society through funding, legislation, hearings, and oversight activities.

Many experts assess that the closure of civil society space is likely to continue. Some experts and advocates warn that, even in already restrictive environments, civil society actors could face new or additional repressive action, particularly when civil society engages in politically charged or sensitive issues. This will likely impact the ability of donors’—including the United States government, private donors, foundations, and international partners—to work with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) abroad. Closing space for civil society could also impact broader U.S. engagement on the freedoms of assembly, association, and expression.

The United States has long supported civil society abroad, which is often viewed as an important component of sustainable democracy and economic growth. The United States is the largest financial supporter of civil society in the world, according to a recent White House fact sheet, with more than $3.2 billion invested to strengthen civil society since 2010. Civil society groups are also in many cases the implementers of U.S. foreign assistance programs.

Many experts view the results of the United States’ efforts to support civil society as mixed. In the face of the rapid geographic and substantive expansion of measures designed to close civil society space, the Obama Administration is credited for launching the Stand with Civil Society initiative in 2013, a global call to action to support, defend, and sustain civil society. This effort saw Presidential attention to the effort through speeches and a Presidential Memorandum. The Administration has also devoted specific funding and programmatic responses to address the closing space phenomenon.

While advocates generally praise the Administration for raising the profile of the closing space issue, some experts question whether the Administration’s actions have fully matched its rhetoric, or whether the policies and structures put into place under the initiative are sustainable. Policy responses to the problem of closing space are complicated by a number of factors, including various competing interests in the policy process, such as balancing support for civil society with U.S. willingness to confront important bilateral partners, possible impacts on other programs or objectives, and the availability of suitable tools or sufficient leverage.

Congress has at times treated the promotion of vibrant civil societies abroad as a key element of U.S. foreign policy and has taken action to support civil society through a range of activities, including legislation. While many such provisions are country- or issue-specific, others are global in scope. Congress may choose to further consider legislation, oversight activities—such as reporting, hearings, or direct engagement—and U.S. funding on this issue.

Closing Space: Restrictions on Civil Society Around the World and U.S. Responses

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Relevance to U.S. Interests

- The Scope of the Closing Space Challenge

- Origins of the Closing Space Phenomenon

- Obama Administration Responses

- Initiatives and Reorganizations

- Stand with Civil Society Initiative

- Direct Civil Society Support Programs

- Ongoing Programs and New Tools

- Coordinating Multilateral Efforts

- Official Reporting on Closing Space

- Modeling Engagement

- Funding Trends

- Perspectives on the Administration's Responses

- Congressional Actions Supporting Civil Society Abroad

- Legislative Action

- Fact Finding and Awareness Raising

- Potential Areas for Congressional Engagement

- Raising the Profile of the Closing Space Phenomenon

- Conducting Oversight of USG Civil Society Support

- Appropriations and Funding

- Examining Policy Trade-Offs in Specific Cases

- Direct Engagement with Counterpart Legislatures

- Outlook

Summary

Civil society organizations (CSOs) around the world are confronting ever stricter limitations on their ability to operate, a phenomenon often referred to "closing space" for civil society work. From restrictions on the types of funding they are allowed to receive to draconian registration requirements, the measures targeting CSOs are increasingly putting pressure on the entire civil society sector in certain countries. These restrictions are most commonly imposed by governments seeking to limit the influence of nongovernmental actors, though restrictions are also being imposed by a broad range of governments, including democratic allies. Increasing awareness of this phenomenon has elevated concerns among civil society advocates and some policymakers, including in Congress. Congress has also shaped U.S. policy toward civil society through funding, legislation, hearings, and oversight activities.

Many experts assess that the closure of civil society space is likely to continue. Some experts and advocates warn that, even in already restrictive environments, civil society actors could face new or additional repressive action, particularly when civil society engages in politically charged or sensitive issues. This will likely impact the ability of donors'—including the United States government, private donors, foundations, and international partners—to work with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) abroad. Closing space for civil society could also impact broader U.S. engagement on the freedoms of assembly, association, and expression.

The United States has long supported civil society abroad, which is often viewed as an important component of sustainable democracy and economic growth. The United States is the largest financial supporter of civil society in the world, according to a recent White House fact sheet, with more than $3.2 billion invested to strengthen civil society since 2010. Civil society groups are also in many cases the implementers of U.S. foreign assistance programs.

Many experts view the results of the United States' efforts to support civil society as mixed. In the face of the rapid geographic and substantive expansion of measures designed to close civil society space, the Obama Administration is credited for launching the Stand with Civil Society initiative in 2013, a global call to action to support, defend, and sustain civil society. This effort saw Presidential attention to the effort through speeches and a Presidential Memorandum. The Administration has also devoted specific funding and programmatic responses to address the closing space phenomenon.

While advocates generally praise the Administration for raising the profile of the closing space issue, some experts question whether the Administration's actions have fully matched its rhetoric, or whether the policies and structures put into place under the initiative are sustainable. Policy responses to the problem of closing space are complicated by a number of factors, including various competing interests in the policy process, such as balancing support for civil society with U.S. willingness to confront important bilateral partners, possible impacts on other programs or objectives, and the availability of suitable tools or sufficient leverage.

Congress has at times treated the promotion of vibrant civil societies abroad as a key element of U.S. foreign policy and has taken action to support civil society through a range of activities, including legislation. While many such provisions are country- or issue-specific, others are global in scope. Congress may choose to further consider legislation, oversight activities—such as reporting, hearings, or direct engagement—and U.S. funding on this issue.

Introduction

Civil society organizations (CSOs), which are often viewed as an important component of sustainable democracy, are confronting growing limitations on their ability to operate around the world. 1 This phenomenon is referred to by researchers and advocates as "closing space" for civil society work. 2 Many experts assess that the closing space trend is likely to continue, which could also impact broader U.S. engagement on democracy promotion or the freedoms of assembly, association, and expression and, in some cases, even conflict with U.S. efforts to promote, development, and security. Congress has taken action to support civil society through a range of activities, including legislation, and may choose to further consider legislation, oversight activities—such as reporting, hearings, or direct engagement—and U.S. funding to respond to growing limitations on civil society around the world.

From restrictions on the types of funding they are allowed to receive to draconian registration requirements, the measures targeting nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society groups are putting ever greater pressure on the entire civil society sector. The restrictions are most commonly imposed by governments seeking to limit the influence of nongovernmental actors. While the problem may be most acute and visible under the repressive regimes in Russia and China, restrictions are also being imposed by a broad range of governments, to include democratic allies such as India and major U.S. foreign assistance recipients such as Egypt.

The United States has long supported civil society abroad, though the implications of this support sometimes vary in practice. It is the largest financial supporter of civil society in the world, according to a recent White House fact sheet, with more than $3.2 billion invested to strengthen civil society since 2010 through training, technical assistance, and direct funding for programs.3 Civil society groups are also in many cases the implementers of U.S. foreign assistance programs managed by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and groups such as the National Endowment for Democracy, among others.

In the face of the rapid geographic and substantive expansion of measures designed to close civil society space, the Obama Administration launched the Stand with Civil Society initiative in 2013 to bolster U.S. support for civil society abroad. The effort saw Presidential attention through speeches and a Presidential Memorandum. While advocates generally praise the Administration for raising the profile of the closing space issue, there is less consensus on whether the Administration's actions have fully matched its rhetoric, or on whether the policies and structures put into place under the initiative are sustainable.

This report provides an overview of the "closing space" challenge, including its origins and current manifestations; outlines current Administration programs and initiatives aimed at addressing the problem; and discusses some areas of potential engagement that Congress may choose to further consider.

Relevance to U.S. Interests

Support for democratic governance abroad has long featured as an element of U.S. foreign policy and has often received significant backing in Congress, although its prominence has varied over time and in specific circumstances. Advocates within and outside of government have argued that the role of civil society is fundamental in a democratic system; according to one expert,

A vigorous civil society helps to ensure that governments serve their people. Joining together in civic groups amplifies isolated voices and leverages their ability to influence governments—to ensure that they build schools, secure access to health care, protect the environment, and take countless other steps to pursue a popular vision of the common good.4

Moreover, civil society can also play an important role in global economic growth and development. According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, civil society space often reflects a positive business environment:

The Special Rapporteur has found that the presence of a robust, vocal and critical civil society sector guarantees, almost without exception, that a State also possesses a good business environment (the converse does not hold: a good business environment does not guarantee a good civil society environment). The rule of law is stronger, transparency is greater and markets are less tainted by corruption. Indeed, the presence of a critical civil society can be viewed as a barometer of a State's confidence and stability—important factors for businesses looking to invest their money.5

Congress at times has treated the promotion of vibrant civil societies abroad as a key element of U.S. foreign policy. A December 2006 Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff report declared that "support for democratic, grassroots organizations has become a centerpiece of America's international outreach."6

Restrictions on civil society not only impact the health of democracies abroad (and U.S. efforts to support them); they also resonate because of their potentially direct impacts on more immediate U.S. interests in crisis situations, as spelled out in an April 2015 report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies:

if Liberia or Guinea had adopted laws that made it difficult or impossible for NGOs to function or receive funding from foreign sources, how would these countries have coped with the Ebola virus? If Kenya adopts such laws, how will the country respond to another famine, and what will the next national election cycle there look like if the hundreds of organizations that helped create citizen demand for a nonviolent election in 2013 no longer exist?7

Crackdowns on civil society groups abroad may also directly impact U.S. government-funded organizations (as in the July 2015 Russia ban on National Endowment for Democracy operations within its borders). In some cases, they can ensnare U.S. citizens who are affiliated with those organizations (for instance, when the Egyptian government cracked down on NGOs in 2011-2012, causing several U.S. citizens working with the National Democratic Institute and International Republican Institute to take shelter at the U.S. Embassy in Cairo; 16 Americans were among 43 workers later convicted in absentia of receiving foreign funding).

The Scope of the Closing Space Challenge

A senior Amnesty International official lamented the increasing restrictions on civil society work globally in a 2015 news article:

There are new pieces of legislation almost every week—on foreign funding, restrictions in registration or association, anti-protest laws, gagging laws. And, unquestionably, this is going to intensify in the coming two to three years. You can visibly watch the space shrinking.8

Groups tracking the increasingly restrictive environment for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have catalogued the problem using a number of different metrics:9

- CIVICUS, an international association of civil society groups, counted "significant attacks on the fundamental civil society rights of free association, free assembly and free expression in 96 countries" in 2014.10

- Freedom House, an NGO focused on expanding democracy and freedom, noted the decline in space for civil society in its 2015 Freedom in the World report, saying, "... whereas the most successful authoritarian regimes previously tolerated a modest opposition press, some civil society activity, and a comparatively vibrant internet environment, they are now reducing or closing these remaining spaces for dissent and debate."11

- The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) has pointed out that between January 2012 and August 2014, some 50 countries introduced or enacted laws designed to restrict the activity of civil society organizations or curtail funding for their work.12

- ICNL also asserts that more than 120 laws constraining the freedoms of association or assembly have been proposed or enacted in 60 countries since 2012. Of these measures, those designed to restrict foreign funding to support the work of civil society groups have seen the fastest growth.13 Such restrictions may include requirements for prior government approval for the use of government-controlled bank accounts, laws demanding "foreign agent" disclosures, or caps on allowable foreign funding.

- The U.S. Agency for International Development produces a Civil Society Sustainability Index (CSOSI) for several regions of the world, tracking developments in this space on an annual basis. For example, the Agency's 2014 report on Africa found that "... in many countries in the region, CSOs—particularly those focused on advocacy and human rights—are facing increasing restrictions or threats of restrictions on their work."14

In many cases, the restrictions have targeted U.S.-funded organizations; for example, in July 2015, Russia banned the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) from operating within its borders.15 The NED thus became the first group to be subjected to a May 2015 law against "undesirable" NGOs.16 The law, which increased Russian authorities' ability to shutter such groups without a court order, followed Russian President Vladimir Putin's assertion to security officials in March that western intelligence agencies use NGOs to "discredit the authorities and destabilize the internal situation in Russia."17 The impact goes beyond U.S. interests; other international donors, including governments, charities, churches, and private philanthropic groups and foundations also are affected. Nor is Russia alone in taking such actions; the Hungarian government, for example, has targeted NGOs that distributed funding from the Norwegian government, accusing them of serving foreign powers seeking to influence Hungarian internal politics.18

Measures targeting foreign funding are potentially especially damaging, experts at the Carnegie Endowment suggest:

Although such support is rarely, if ever, a determinative factor in the political life of recipient countries, it often does have tangible effects on the institutions and processes that it reaches. This is especially true in the civil society domain, where external funding can be a lifeline for groups working on sensitive topics for which domestic funding is scarce, such as human rights advocacy, anticorruption work, or election monitoring. Limiting these organizations' access to external support weakens their capacity for action and often threatens their very existence.19

In addition, while crackdowns in authoritarian countries such as Russia or China appear to garner the lion's share of Western media attention, experts suggest that repressive measures are being taken against civil society around the world in a variety of political systems and across cultural and economic lines.20

Restrictions can target not only groups doing what some would call 'political' or rights-focused work (such as human rights defenders and democracy advocates), but also humanitarian actors, civic coalitions, watchdog groups, economic cooperatives, or service providers, as well as other organizations that may receive foreign funding. Repressive regimes often apply different standards to NGOs based on their activities. For example, organizations working on human or political rights may face more restrictions or penalties than organizations providing humanitarian services. Experts assert that these differences are intended to create divisions that prevent civil society groups from responding collectively, though, in some cases, deep divisions already exist within civil society due to local political and social dynamics.21

The geographic breadth of the problem is demonstrated by the following, nonexhaustive list of examples.22

- India has increased restrictions on foreign-funded organizations, including the Ford Foundation, Mercy Corps, and especially Greenpeace India; its government also revoked more than 10,000 NGO licenses in the first half of 2015 from civil society groups due to failures to detail foreign funding.

- Ethiopia adopted a law in 2009 restricting NGOs that receive more than 10% of their funding from foreign sources from engaging in human rights or advocacy activities.

- Angola's president issued a decree that took effect in March 2015 that limits foreign funding of NGOs and imposes strict registration requirements.

- Bangladesh enacted a law in December 2014 that strictly limits foreign financing of NGOs, and the government is considering a Cyber Security Law that could stifle free expression online.

- Cambodia has placed strict new registration and "neutrality" requirements on NGOs since August 2015, despite an international campaign against the restrictions.

- The Egyptian government in 2014 mandated that all civil society groups must register with the Ministry of Social Solidarity; the penal code also was amended in the context of counterterrorism to mandate life imprisonment for anyone who receives funds from foreign entities. In 2011, the Egyptian government also brought legal cases against local and international NGOs for allegedly receiving illegal funding from abroad, resulting in the conviction and sentencing of 43 foreign and Egyptian NGO employees to prison terms in 2013.

- Hungary imposed measures against Norwegian-funded NGOs (including Transparency International Hungary) beginning in the spring of 2015.

- Uganda adopted a law in January 2016 that more strictly controls NGO registration and activity that is against "the interests of Uganda" or the "dignity of Ugandans"; in addition to limitations on political or human rights work, there is particular concern that the new law could target organizations working on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) issues.23

- Pakistan expelled Save the Children in June 2015, as part of a broader crackdown on foreign-funded civil society groups, and announced a laborious regulatory policy requiring governmental approval to access foreign funds in October 2015.

- In Ecuador, a June 2013 decree placed time-consuming new regulations on NGOs, as part of broader restrictions leading to the 2014 cessation of USAID operations in the country.

- Sudan expelled 13 international NGOs and banned 3 Sudanese relief organizations in 2009 on allegations of collaborating with the International Criminal Court and unnamed "foreign powers" after the ICC issued an arrest warrant for the country's president. Other NGO expulsions occurred in 2012 and 2014.

- South Sudan adopted a law in February 2016 that mandates NGO registration and government monitoring and criminalizes noncompliance with the law; humanitarian actors have voiced concern that the law will impede aid provision.

- Other countries considering legislation restricting NGO activities include (but are not limited to) Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan, and Vietnam.

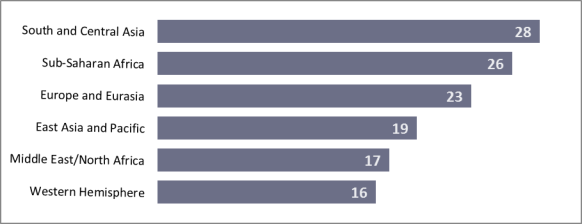

A geographic categorization of repressive measures as tracked by ICNL is provided as Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Repressive Initiatives Since 2012 |

|

|

Source: Douglas Rutzen, "Authoritarianism Goes Global (II): Civil Society Under Assault," Journal of Democracy, vol. 26, no. 4 (October 2015), pp. 28-39, http://www.icnl.org/news/2015/05_26.4_Rutzen.pdf. |

Many experts assess that the closing space trend is likely to continue as authoritarian actors seek to grow their influence both at home and globally.24 Some experts and advocates warn that, even in already restrictive environments, civil society actors could face new or additional repressive action, particularly when civil society engages in politically charged or sensitive issues.25 Such actions could include intimidation, arrest and detention, criminal penalties under new NGO laws, physical attacks, extrajudicial killings, and harassment online. Civil society groups in Burundi, for instance, were harassed and jailed for opposing the president's efforts to extend his mandate in 2015, which has led to ongoing unrest and violence in the country.26 Impunity for acts of violence and repression, either by governmental or nongovernmental actors, may also cause civil society actors to self-censor or leave the country due fears of retaliation. For example, more than 101 environmental activists were killed in Honduras between 2010 and 2014, and some members of civil society engaged on land rights and environment have fled Honduras due concerns for their personal safety.27 These security concerns may affect the ability of donors—including the United States government, private donors, foundations, and international allies—to safely work with CSOs abroad. This, in turn, could further impact the United States' ability to engage directly with local organizations and populations on the freedoms of assembly, association, and expression as well as U.S. efforts to work with local actors on security and development.

Origins of the Closing Space Phenomenon

While the origins of the closing space phenomenon are complex and in many cases country-specific, scholars suggest that several drivers have accelerated the problem. A 2014 publication by the Carnegie Endowment, Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire, explores the causes of the phenomenon and the context of democracy promotion writ large, and makes the following observations:28

- As the cold war ended, western governments shifted away from providing humanitarian assistance largely through foreign governments towards funding nongovernmental organizations directly, including those working in more explicitly political areas.

- A number of events caused semi-authoritarian regimes to view the civil society sector increasingly warily: highly coordinated western support to anti-Milosevic nongovernmental forces in Serbia; the color revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan; the "Arab Spring" movements; and others.

- Russia and China have openly challenged the idea of the universality of liberal democratic political values, offering an alternative conception of the rights and responsibilities of citizens and models of governance.

The phenomenon's acceleration has been facilitated by the fact that governments seeking to inhibit civil society groups have learned from each other, for example by copying and implementing nearly identical restrictive legislative measures, analysts suggest.29 Russia and China maintain a driving role, not only in demonstrating restrictive behavior but also in publicly defending their actions as legitimate. Their example, along with that of India (notably the world's most populous democracy) and Ethiopia, has provided a lead for other countries to follow.

Finally, many observers suggest that another development has contributed to the closing of space for civil society: a post 9/11 focus on counterterrorism. Many experts recognize the legitimate threat terrorism poses to states and multilateral actors, and some point to civil society as partners in efforts combat terrorism, noting that the "importance of involving civil society in a comprehensive and multidimensional response to the threat of terrorism has been stressed by various international documents."30 Nonetheless, according to the Carnegie report, "Governments in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and elsewhere have used the war on terror as an excuse to impose restrictions on freedoms of movement, association, and expression." 31 Some observers point especially to the unique role of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an inter-governmental organization created in 1989 to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.32 While FATF combats illicit funding flows, some experts suggest that its recommendations have been disproportionally hard-hitting on legitimate CSOs and philanthropic organizations.33 The organization's focus on counter-terrorism, critics argue, led to an uncompromising stance in which some governments that have eliminated civic space altogether are rated highly for preventing illicit funding flows. Notably, more than 120 nonprofit organizations have called on FATF to amend its approach to ensure that civil society doesn't face "over-regulation of the sector," a recommendation supported by a United Nations Special Rapporteur.34

Obama Administration Responses

While the United States government has had programs to engage with and promote civil society abroad for decades,35 the Obama administration has taken additional actions to address the closing space challenge's recent acceleration. Administration officials point to a broad scope of mutually reinforcing policies, diplomacy, and assistance that seek to advance freedom for all, including civil society, particularly through enhanced collaboration among State, USAID, Justice, Labor, Defense, and other Departments.

Initiatives and Reorganizations

The challenge of restrictions on civil society abroad has been given high-level attention by the Administration. In 2009, then Secretary of State Clinton announced the Civil Society 2.0 Initiative, which sought to build the capacity of grassroots organizations to use new digital tools and technologies to increase the reach and impact of their work.36 In 2011, the State Department launched a Strategic Dialogue with Civil Society. Summits were held in 2011 and 2012. The purpose of the Dialogue was to "elevate U.S. engagement with partners beyond foreign governments and to underscore the US Government's commitment to supporting and protecting civil society around the world."37

The Administration also established an Interagency Policy Committee38 (IPC) for civil society-related issues in 2013, providing a venue for targeted discussions and decisions on civil society within the interagency. In 2010, for the first time the State Department appointed a Senior Advisor for Civil Society and Emerging Democracies (SACSED). In 2014, Secretary of State John Kerry said the civil society and democracy agendas were "now fully integrated," noting that the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor and Special Representative for Global Partnerships were "working to ensure that the civil society and democracy agenda ... remain at the forefront of our diplomatic engagement."39

Stand with Civil Society Initiative

In September 2013, the President launched the Stand with Civil Society initiative—a global call to action to support, defend, and sustain civil society.40

The initiative is as a partnership with other governments, NGOs, the philanthropic community, and multilateral initiatives to focus on three lines of effort: (1) modeling positive engagement between governments and civil society;41 (2) developing new assistance tools and programs, including regional civil society hubs; and (3) coordinating multilateral and diplomatic pressure to push back against restrictions on civil society.

One year later, President Obama issued a Presidential Memorandum on Deepening U.S. Government Efforts to Collaborate with and Strengthen Civil Society. In a corresponding speech, he emphasized the role civil society plays in holding governments accountable and in promoting economic growth, and said, "If you want strong, successful countries, you need strong, vibrant civil societies."42 The memorandum also made explicit that "partnering and protecting civil society groups around the world is now a mission across the U.S. Government ... this is part of American leadership."43 President Obama directed that executive departments and agencies

- consult with civil society representatives;

- work with CSOs even when local laws are restrictive;

- oppose undue restrictions on civil society and fundamental freedoms by foreign governments behaving in a manner inconsistent with their international obligations;

- facilitate exchanges between governments and civil society; and

- report to the President annually on progress.

In 2015, the Deputy National Security Advisor identified a number of key lessons that had been learned since the launch of the Stand with Civil Society initiative, including

- the need for a long-term effort;

- taking early action during democratic transitions;

- identifying civil society champions in government and the legislature;

- expanding consultations that include civil society and government to develop sound legal frameworks; and

- supporting civil society efforts at self-regulation, transparency and accountability.44

Direct Civil Society Support Programs

The primary implementers of U.S. support to civil society space abroad are USAID and the State Department's Bureau of Democracy Human Rights, and Labor (DRL), though many other Bureaus in the State Department also work with civil society. DRL's assistance to civil society is largely managed by the Office of Global Programming, which, also coordinates internally and with NED. USAID's Center for Excellence on Democracy, Rights, and Governance (DRG Center) leads many of the Agency's efforts to bolster civil society directly. The DRG Center was launched in 2014 to lead on understanding responses to efforts to integrate democracy, rights, and governance in development.45 USAID funding to civil society is also provided via USAID's in-country presence (its "Missions").

U.S. programs operate in a range of environments, including countries that are considered "non-permissive." USAID and DRL testified to Congress that they program in states transitioning from crisis or conflict, repressive or authoritarian countries, "'backsliding' states whose governments have become more sophisticated in their repression, specifically targeting civil society," and—at least for DRL—even where the United States has no diplomatic presence.46

DRL has also testified that while its programs are overt and notified to Congress, the Bureau employs "methods aimed at protecting the identity of our beneficiaries," in an effort to avoid "anything that would help an authoritarian government take repressive actions against or punish our partners."47 USAID also called their work with civil society in repressive countries "sensitive" and emphasized physical security and protection for partners as a concern.48

Ongoing Programs and New Tools

|

Examples of Country-Specific U.S. Programs State and USAID have undertaken a number of programs to support civil society in specific countries. For example: Burma: Technical assistance to a CSO working group negotiating a new registration law that resulted in improvements to the law enacted in July 2014. China: Programs build the capacity of grassroots civil society groups, and take advantage of technological developments to enable greater freedom of expression. Iraq: Support for the formation of the Alliance of Iraqi Minorities and their advocacy for the inclusion and the rights of their members within Iraqi law and society. Kazakhstan: Support to independent CSOs that are now consulted on legislative initiatives such as the new criminal code. Nigeria: Support for the development of a civil society position paper against legislation that would restrict donor funding for civil society operations; Rwanda: Alternative funding mechanisms and programs to counter government attempts to channel donor funding through government approved systems; Ukraine: Support for a coalition of over 70 civil society groups advocating for reforms. Sources: The White House, "Support, Defend, and Sustain: The Relevance of U.S. Response to Closing Civic Space," press release, June 24, 2015; Acting Assistant Secretary of State for DRL Uzra Zeya testimony before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Subcommittee, February 26, 2014. |

A number of State Department and USAID programs and funds are specifically designed to support civil society through a range of activities. Some are focused on emergency responses and protection. Others seek to address the root causes of restrictions on civil society, such as legal and regulatory frameworks or other challenges to the enabling environment. A nonexhaustive list of these activities includes

- The State Department's global Human Rights and Democracy Fund (HRDF), managed by DRL, is a mechanism established in 1998 that provides assistance to promote civil society. HRDF assistance can be used for a range of activities, from "aiding embattled NGOs on the frontlines to countering cyber-attacks on activists and assisting vulnerable populations."49 Since its creation, the Fund has grown from $8 million in FY1998 to $78.5 million in FY2015. DRL also receives approximately $65 million in Economic Support Funds (ESF) from other bureaus to support activities in eight countries, including Iraq, Cuba, and Pakistan.50 DRL is providing $138 million in FY2015 funding that benefits civil society and activists around the world and their efforts to advance freedom and inclusion.51

- In 2011, the State Department launched the Lifeline: Embattled Civil Society Organizations Assistance Fund to offer emergency grants to civil society organizations.52 Lifeline is a consortium of 7 international NGOs supported by a Donor Steering Committee of 18 governments and 2 foundations.53 Lifeline reports that, as of December 31, 2015, it has supported over 814 CSOs in 98 countries and territories with emergency assistance and rapid response advocacy grants since 2011.54 The fund is managed by DRL. The fund has received a total of $7.1 million in U.S. assistance, including $2 million dollars through the HRDF in FY2014.55 Grants from Lifeline typically provide small amounts of emergency grants to CSOs that are threatened for advancing human rights or for advocacy efforts that seek to push back against closure in civic space. These grants can address a range of specific emergency needs such as, security and protection, legal representation, temporary relocation, community mobilization, policy and legal advocacy, civil society coalition building, and strategic litigation.

- The Legal Enabling Environment Program (LEEP) is a USAID program launched in 2013 that opposes efforts by governments to restrict freedoms of expression, peaceful assembly, and association. Implemented by ICNL, the $3.5 million56 program offers technical assistance as well as capacity building around legal reform, sometimes for emergency situations. It has been active in El Salvador, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kenya, Macedonia, Nicaragua, Morocco, Tunisia, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Kyrgyzstan, among others.

- The U.S. government (through USAID) and its partners are establishing a network of regional Civil Society Innovation Initiative (CSII) Hubs.57 The Hubs, funded through a Donor Coordination Group that includes the United States, Sweden, and private philanthropic partners, are intended to encourage cooperation, innovation, research, learning, and peer-to-peer exchanges among civil society groups. A September 2014 White House fact sheet suggested that up to six such hubs would be created in the 2014-2016 timeframe.58 USAID's DRG Center plans to provide approximately $12 million for the Hubs over the next five years; additional or matching funds may also come from other parts of the U.S. government, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and the Aga Khan Foundation.59

Coordinating Multilateral Efforts

The administration has sought to be a vocal advocate for civil society at the United Nations as well as in other organizations, including the Community of Democracies (CD) and the Open Government Partnership (OGP).

Established in 2000, the CD is an intergovernmental organization with 106 signatories that seeks to advance democratic principles and drive the global democratic agenda through common action.60 The United States assumed the Presidency of the CD in July 2015 for a two-year term.61 U.S. officials and experts have noted that this status may provide the United States with a useful platform to galvanize member attention on protecting space for civil society or to create a specific call to action amongst CD members when governments are considering new laws, regulations, or administrative measures that restrict civil society. The CD also leverages multilateral engagement through its Working Group on Enabling and Protecting Civil Society, which fosters collaboration between states, civil society, and international organizations to counter closing space.62 In 2014, the United States committed $3 million in core funding to CD over three years to bolster the promotion of civic space and may contribute more in the future.63 DRL also provided $400,000 to CD so that the organization could provide small grants to assist civil society.64

OGP is a multilateral initiative aimed at "securing commitments from governments to promote transparency, increase civic participation, fight corruption, and harness new technologies to make government more open, effective, and accountable."65 OGP was formally launched in September 2011 by the United States and seven other founding governments: Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, South Africa, and the United Kingdom.

As a founding member and part of the Steering Committee, the United States coordinates with government partners and the OGP civil society chairs on international open government priorities. According to the Administration, "The United States is leading by example in OGP by seeking ways to expand U.S. Government engagement with U.S.-based civil society organizations to develop and implement the U.S. Open Government National Action Plan."66 Since 2011, OGP has expanded to include 69 countries and several hundred civil society organizations.67 The United States is a significant donor to OGP; USAID has provided approximately $1 million in support to OGP's secretariat since 2014.68

Some experts also point to the importance of the fact that the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which build on the Millennium Development Goals, now include governance issues. U.S. officials privately suggest that this occurred in large part due to U.S. efforts, and the United Nations has said that the SDGs provide an international platform in which civil society can play a role as a key stakeholder.69

Official Reporting on Closing Space

While the State Department's annual Country Reports on Human Rights70 report on civic and political rights, the reports are not focused specifically on the challenges facing civil society. The reports may include some instances of abuse of civil society organizations and actors and generally include reporting on restrictive laws.

USAID periodically publishes the Civil Society Organizations Sustainability Index (CSOSI). The CSOSI seeks to assess the overall strength and viability of civil society by examining and assigning scores to seven interrelated dimensions: legal environment, organizational capacity, financial viability, advocacy, service provision, infrastructure, and public image. It was first published in 1997 with a focus on Europe and Eurasia, and has since expanded to report on some countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, as well as Afghanistan and Pakistan. Reports are not always issued annually, but aim to enable users to track developments and identify trends in the civil society sector. USAID's Bureau for Europe and Eurasia continues to fund and manage the CSOSI for its region. The DRG Center was able to expand the Index to other regions through partnerships with the Africa Bureau, the Middle East Bureau, the Aga Khan Foundation, and a number of USAID Missions, including the Sudan and South Sudan Missions and four Missions in Asia.71

Modeling Engagement

In addition to the other efforts outlined above, the U.S. government has also promoted its own regulation of domestic NGO space as one positive framework that seeks to respect national interests and fundamental freedoms. The State Department produced a factsheet in 2012 that provides an overview of the U.S. government's definition of civil society as well as the U.S. approach to regulating NGOs. 72 The factsheet highlights that U.S. regulations on civil society facilitate and support the formation of NGOs and that "U.S. regulations are designed specifically to avoid making judgments about the value or work of any given NGO." Also, the Department of Treasury has been consulting with the nonprofit sector as part of the Financial Action Task Force73 (FATF) process in order to address concerns about terrorist abuse of funding to civil society, such as restrictions on NGOs as a result of efforts to counter terrorist group financing. Another measure promoted by the Administration as a model is its effort to facilitate global philanthropy by private U.S. foundations by amending tax rules to increase the cost-effectiveness of tax service expenditures by foundations.

Funding Trends74

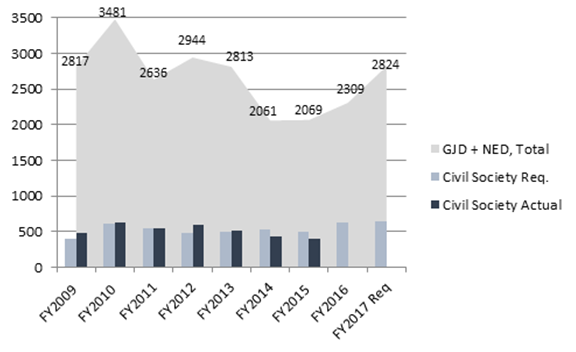

As illustrated in Figure 2, since FY2009 the United States has provided more than $3 billion in foreign assistance to promote civil society.75 Detailed information on specific funding to individual countries is beyond the scope of this report; however, research indicates that relatively large amounts of assistance may be devoted to a small number of countries. For example, out of the 146 countries that were eligible for official development assistance per the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)76 in 2015, only 12 countries have received U.S. investments of more than $100,000 per year to advance civil society legal reform.77 Though these figures do not reflect regional or global programs or emergency response assistance, they do represent funding that is used to support the enabling environment (i.e. legal and regulatory frameworks) for civil society.

The Administration reports that in FY2015, the most recent year for which complete data is available, $396 million was specifically allocated to promote civil society globally.78 This amounts to about 20% of the $2 billion allocated for programs under the "Governing Justly and Democratically" (GJD) foreign assistance objective and for the NED (which is not considered foreign assistance). Notably, other funding under NED and the broad GJD objective supports democracy promotion, good governance, human rights, and rule of law, which many experts consider essential for civil society's broader enabling environment.79

Funding for direct civil society assistance and broader GJD assistance declined between FY2012 and FY2014, and remained relatively flat for FY2015.80 For FY2016, however, the Administration requested more than $3 billion for these activities, a 46% increase over FY2015 funding. This also included $602 million for civil society, a nearly 65% increase over FY2015 funding. Congress responded by appropriating "no less than" $2.3 billion for "democracy programs," resulting in a funding increase for GJD of at least 11%.81 It is unclear whether the higher FY2016 democracy funding will result in a higher allocation for civil society programs in FY2016. For FY2017, the Administration has requested $2.8 billion for GJD and NED, of which $652 million is allocated for civil society. Overall, funding for civil society accounted for 1% of U.S. foreign assistance in FY2015; GJD funding accounted for 5%.

Perspectives on the Administration's Responses

According to many experts,82 the U.S. record in supporting civil society is mixed.

The Obama administration is credited by many experts with having recognized the accelerated closing of civil society space and the need to respond. Practitioners and U.S. officials point to Stand with Civil Society and the Presidential Memorandum as important steps that formalized the Administration's commitments to civil society. They commend the Administration's leadership on rapid response assistance such as Lifeline, which was founded in 2011 to provide emergency assistance to CSOs in partnership with other governments and foundations. For example, an expert on civil society space has called Lifeline an "important increase"83 to quick-action financial assistance.

Experts also recognized a need to balance resources between longer term capacity building, addressing the enabling environment (i.e. legal and regulatory frameworks), and emergency response needs. Nonetheless, given the increase in restrictions on CSOs in recent years, many noted that reaching CSOs under threat with relatively small amounts of funding—sometimes as little as $5,000 to $10,000—could have a significant impact.

A comprehensive accounting of U.S. responses is complicated by the fact that some U.S. assistance (either diplomatic or financial), while valuable, may be less publicly visible or even unwanted. In conversations with CRS, Administration officials and practitioners privately underline that the public record of U.S. government support to civil society is necessarily incomplete due to concerns over retaliation and safety. Some interventions in support of persecuted civil society actors are best done quietly, they suggest. In other cases, non-U.S. actors may be the preferred interlocutor, as some CSOs are unwilling to accept U.S. aid—be it financial or diplomatic—due to concerns that it could undermine their credibility at home.

While experts generally agree that the United States has demonstrated leadership in understanding and framing the problem of closing space, the policy response has been complicated by a number of factors, including various competing interests in the policy process, such as balancing support for civil society with U.S. willingness to confront important bilateral partners, possible impacts on other programs or objectives, and the availability of suitable tools or sufficient leverage.84 In conversations with CRS, former and current officials have privately voiced concern that civil society issues do not often rise to high-level decision-making, particularly when contrasted with decision points around traditional national security interests (e.g. foreign military sales or counterterrorism efforts) and/or development goals (e.g. health). Critics suggest that recent reductions in U.S. funding to promote democratic space and good governance—coupled with increases in U.S. support to other sectors such as security—may send a mixed message to host countries about U.S. priorities. Some also point to the decline in U.S. funding85 for democracy and governance (DG) since FY2012, particularly in countries like Egypt, Ethiopia or Sudan that have placed restrictions on NGO activity, as being perceived as rewarding bad behavior and abandoning civil society.86

More could be done to institutionalize the Administration's efforts to bolster civil society in U.S. foreign policy in the face of competing policy priorities, some experts suggest. For example, the SACSED position established by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton created a direct line to the Secretary and highlighted U.S. engagement with civil society as a key component of U.S. foreign policy and diplomacy. However, in discussions with CRS, many policymakers cautioned against using special envoys alone for this issue. The trade-offs inherent in policy decisions within the interagency process on civil society issues can make it more difficult for a special envoy to engage effectively in policymaking in multiple regions, especially when security threats are also a concern. Advocates suggest that enhanced institutional capacity related to this issue throughout the interagency, particularly through resourcing and staffing, might have a more sustainable impact. Advocates also recommend that all U.S. officials should elevate the focus on civil society, and that officials and programs should be evaluated, in part, on the basis of their engagement with civil society issues; some experts have also suggested the issuance of a Presidential Directive to this effect.87

Some have also underlined the utility of legislation such as the Brownback amendment (see "Legislative Action" below), in protecting U.S. support for civil society, both within the interagency when faced with competing interests, and in ensuring that foreign governments (including key security partners) cannot undercut U.S. support for civil society in repressive environments.

The multilateral tools that the Administration has sought to bolster, including the CD and OGP, present new partnerships and opportunities that some experts hope will lead to concrete outcomes; however, some suggest that multilateral efforts may struggle because they also seek to include countries with mixed or restrictive records on civil society. Others question if these organizations can create good response mechanisms when members repress or restrict civil society. A test case is ongoing in the OGP with member state Azerbaijan, which is under review after international CSOs filed a complaint in March 2015. OGP reviewed and assessed the CSOs complaints to be credible.88 In an upcoming ministerial meeting in May 2016, OGP will review corrective actions by Azerbaijan and the status of its membership in the organization.89 Observers suggest this could be an opportunity to assess OGP's effectiveness in helping governments and civil society work cooperatively for transparent governance.

Observers have also questioned the effectiveness of the Administration's presentation of U.S. regulation of NGOs as an example for other governments. For example, some suggest that the United States has sent mixed signals about its support to CSOs when it comes to efforts to counter terrorism financing. While the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), of which the United States is a leading member, was created to combat illicit funding flows, activists suggest that its recommendations have had a disproportionate impact on legitimate CSOs and philanthropic organizations, especially when compared to regulation of the private sector.90 The organization's focus on counter-terrorism, critics argue, has led to an uncompromising stance in which despotic regimes that have eliminated civic space altogether are rated highly for preventing illicit funding flows. 91 They suggest that U.S. policy and models, as well as institutions like the Treasury Department, should address fears that NGOs could be used as fronts for corruption or terrorist financing activities while also working to support civil society space and operations.

Experts further caution that, though the United States has raised international attention to the issue, restrictions on civil society also impact other governments and donors—both public and private. Some are calling for civil society and NGOs to develop membership models and/or a culture of philanthropy within their countries as possible alternatives to foreign funding. Experts also assess that the underlying issues, namely free expression, assembly, and association, are not merely a concern for civil society, NGOs, or human rights activists. Rather, they suggest that repressive actors could potentially benefit from separating concern over civil society space from broader attention on fundamental freedoms.

Congressional Actions Supporting Civil Society Abroad

Congress has demonstrated a strong and sustained interest in the promotion of vibrant civil society abroad as part of U.S. efforts to promote democracy, development, and security. While many such provisions are country- or issue-specific, others are global in scope. A nonexhaustive list of recent key examples follows:

Legislative Action

- Inclusion of numerous provisions in appropriations measures supporting the role of civil society in international programs. For example, the House committee report accompanying the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Bill, H.Rept. 114-154 includes the following passage:

The Committee notes that during this time of unprecedented political change in many countries around the world, American leadership is critical. It is imperative that assistance is provided to advance democracy worldwide. The Committee is concerned about increased repression of civil society in many countries, which inhibits the ability of citizens to exercise their fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of association, speech, and religion. This disturbing global trend requires new approaches to promote democracy in order to overcome obstacles put in place by increasingly repressive governments. The Committee notes that finding new approaches does not mean retreating from America's role in advancing democracy worldwide. The Committee, therefore, increases funding for the National Endowment for Democracy and the Democracy Fund above the fiscal year 2015 enacted level and includes not less than the fiscal year 2015 enacted level for democracy programs.

- Introduction of legislation that includes mention of the key role of civil society in a broad array of measures. In the 114th Congress, some examples of such measures include H.R. 1567, the Global Food Security Act of 2015; S.Res. 388, a Resolution Supporting the Goals of International Women's Day; S. 2632, the Vietnam Human Rights Act of 2015; S. 2551, the Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act of 2016; and H.R. 2989, the South Sudan Peace Promotion and Accountability Act of 2015, to name a few examples.

- In what is generally referred to as the "Brownback amendment," the 2005 enactment of a provision in the annual appropriations legislation stating that "democracy and governance activities shall not be subject to the prior approval by the government of any foreign country."92 The legislative language originally pertained to Egypt, and was expanded in FY2008 to include "any foreign country."

Fact Finding and Awareness Raising

- Fact-finding missions and publications such as a December 2006 Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff report on "Nongovernmental Organizations and Democracy Promotion: "Giving Voice to the People," based on research conducted by staff in selected countries in Africa, Asia, Central Europe, and Latin America.93 Members and staff regularly meet with civil society groups when traveling abroad, both to gather information and to signal support for such groups.

- Hearings such as "Threats to Civil Society and Human Rights Defenders Worldwide," held by the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission on May 17, 2012, and a broader 2015 "Briefing Series on the Shrinking Space for Civil Society" by the Commission featuring discussions on Kenya, Bangladesh, and with Press Freedom Awardees from Ethiopia, Paraguay, Malaysia, and Syria.

- Participation in organizations such as the Commission on Security & Cooperation in Europe, also known as the U.S. Helsinki Commission. The Commission is an independent agency of the Federal Government which monitors compliance with the Helsinki Accords and seeks to advance comprehensive security through promotion of human rights, democracy, and economic, environmental and military cooperation in the OSCE region. The Commission holds hearings, and its Congressional Co-Chairs issue statements, highlighting specific challenges to civil society in the Eurasian space.

Potential Areas for Congressional Engagement

Congress will likely continue to provide oversight of democracy assistance programs and, given the recent history of congressional action described above, it appears likely that at least some in Congress may to seek to continue to promote and protect the role of civil society abroad in particular. Among the actions that Congress may consider on this issue, several potential avenues emerge, any of which could potentially be addressed through legislation.

Raising the Profile of the Closing Space Phenomenon

Congress has used a variety of means to call attention to specific cases of repression of civil society groups abroad. These have included, for example: hearings, legislation, communications with administration officials or with foreign governments, public statements, fact-finding missions abroad, and funding directives. Members will likely continue to use these tools to highlight the role of civil society and the challenges CSOs face in various countries.

Congress could also mandate high-profile reporting from the executive branch on this issue. For example, Congress could require dedicated, public reporting on civil society challenges in existing executive branch reports to Congress. Congress could also mandate that the reporting include a public rating or ranking system for political and civil rights. Such ratings could be based on diplomatic assessments as well as NGO reports and ratings.94 Such rankings could, of course, also be tied to restrictions, conditions, and/or increases in engagement, assistance, or Congressional oversight. Some advocates have argued that the Congressionally-mandated ranking approach in the State Department's Trafficking in Persons Reports, which reports on human trafficking and ranks governments on their efforts to address the problem, has been useful as a tool to encourage improved behavior by otherwise unresponsive governments; other examples have included reporting and restrictions on issues ranging from child soldiers to international religious freedom.

Conducting Oversight of USG Civil Society Support

In providing oversight of U.S. government programs assisting civil society abroad, Congress may wish to examine a broad range of issues related to the design, effectiveness and execution of such programs, including provisions relating to their monitoring and evaluation.95

The efficacy of current programs is a broad category that Congress may seek to investigate. Questions could range from the most detailed examination of specific country cases, to how the challenge is being addressed on a global scale, or how to identify or develop metrics to measure efficacy. Congress could explore at the broadest level additional measures the U.S. government might undertake to limit or reverse the increasing tide of measures restricting civil society globally.

Congress might also examine the appropriate mix and relative efficacy of smaller, targeted, often discretely executed programs designed to assist specific individuals or groups, with broader, systemic approaches seeking to improve the climate for civil society activity. While the former approach is often executed using funding in the low thousands of dollars, broader approaches (such as the Civil Society Hubs under development using USAID and other funding) can require millions of dollars over a longer term.

The effectiveness and durability of the institutional organization of U.S. government programs supporting civil society may also be an avenue of Congressional interest. Congress could explore, for example, the effectiveness of the National Security Council-led interagency process designed to ensure that all relevant policy dimensions, including civil society support, are taken into account. Among the key questions in this respect, observers suggest, is the extent to which counter-terrorism imperatives—including the need to address foreign financing of terrorist organizations through mechanisms such as FATF—are balanced with other concerns in the broader policy discussion.

Congress might also wish to assess the extent to which the priority given to this issue under the Obama administration has been tied to specific individuals, and how it has or might be affected by changes in key foreign policy and national security personnel – or a change of administration.

Congress may wish to examine the various funding streams dedicated to civil society support. In reviewing this area, Congress could consider not only trends and levels of funding, but how U.S. funding is best provided—whether directly, or through multilateral efforts, for example. Congress may also review a number of additional issues, such as

- the role and effectiveness of cross-border funding of CSOs by private sources such as foundations;

- ongoing debates among CSO analysts regarding whether foreign support to CSOs has the potential to divorce foreign CSO representatives from accountability to those they serve directly;

- the extent to which U.S. support could lead civil society groups to be labeled as foreign or American entities, further feeding into narratives painting civil society as foreign organizations that require strict regulation; and

- best practices for how the United States works with civil society as a donor, including efforts to provide operational support to embattled organizations or programs that instead fund CSOs to provide services or implement U.S.-funded programs.

Also of interest could be an examination of the coordination and overlap between multilateral efforts such as the Open Government Partnership, the Community of Democracies, and even industry-focused civil society partnerships like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). The United States assumption of the Presidency of the Community of Democracies in July 2015 for a two-year term might also be an opportunity for additional scrutiny of U.S. and multilateral efforts to address restrictions on civil society.

Appropriations and Funding

Through the appropriations process, Congress could direct increased funding levels for programs that directly support civil society through a range of activities, including capacity building, legal aid, and public diplomacy. Congress could also explore minimum funding levels for civil society, which could address rapid response efforts as well as efforts to improve the operational environment. Flexible funding for multilateral coalitions or U.S. programs that provide emergency assistance to civil society (such as emergency response programs like Lifeline and programs focused on the enabling environment like LEEP, described above) could be a particular focus. Multilateral funding coalitions could be an additional avenue of support for organizations that cannot accept or do not want U.S. funding. Congress could also bolster funding for Governing Justly and Democratically (GJD) and the National Endowment for Democracy, as broader efforts to promote democracy and governance may lead to an enabling environment for civil society. In addition, Congress could direct portions of bilateral and regional funds (such as Development Assistance or Economic Support Funds) towards civil society support. Congress could also explore the extent to which such funds, when appropriated, have been transferred by agencies towards other purposes.

Members could also seek to expand legislative restrictions or conditions relating to foreign assistance and civil society, such as the Brownback amendment. This could include a review of foreign aid to countries that repress civil society. Congress may wish to assess if U.S. assistance, including security assistance (equipment or arms sales, etc.), could be used by foreign governments to undermine the enabling environment for civil society and explore legislative restrictions or conditions that restrict some assistance if/when civil society is restricted by foreign governments. Congress might also explore whether additional restrictions or authorities might be usefully leveraged by U.S. assistance implementers to the benefit of civil society groups abroad.

Examining Policy Trade-Offs in Specific Cases

Many experts and former U.S. officials acknowledge that the Administration's rhetorical support for civil society abroad has not always matched its publicly visible actions. For example, President Obama's 2015 visit to Kenya and Ethiopia appeared to highlight differences in the U.S. approach to standing with civil society. In Kenya, President Obama was seen publicly with numerous civil society activists—including some groups that the Kenyan government considers problematic—and participated in a specific event with NGOs. In Ethiopia, in contrast, U.S. concern about strict government control over NGOs and civil society space was largely addressed behind closed doors. Though many observers recognize the uniqueness of each country's context, some contend that Obama's visit to Ethiopia—which is a key counterterrorism partner, a regional power, and a top troop contributing country for peacekeeping operations—did not send a strong signal of support for civil society or countering repression.96 Congress could explore these and other kinds of cases with senior Administration officials in hearings or private briefings.

Direct Engagement with Counterpart Legislatures

Congress could, some advocates suggest, engage directly with legislatures considering potentially repressive CSO legislation. Such engagement could be pursued bilaterally, in coordination with other like-minded legislators or legislatures, or through multilateral interparliamentary groups such as the Inter-Parliamentary Union or the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly. In addition to issuing statements of concern, Members could invite foreign legislators to the United States for dialogue and to share best practices. Congressional travel may be another avenue for engagement with legislative counterparts and at-risk CSOs.

Outlook

The repression of civil society in many countries around the world may represent a "new normal," many experts fear, a dynamic which poses significant challenges to the promotion of democratic governance abroad. In the face of what some have called a democratic roll-back, U.S. policymakers, and Congress in particular, may consider options to include how best to support civil society abroad, in particular when weighing such support against the desired cooperation of a foreign government on other issues of critical interest to the United States. U.S. leadership on this issue, including in the context of multilateral organizations, may be received quite differently depending on the specific circumstance, requiring sophisticated understanding of local conditions as well as effective coordination with other actors ranging from private foundations to international partners.

Advocates of support to civil society abroad are concerned that the Administration's elevation of the issue, manifested in the Stand with Civil Society initiative, while laudable in principle, may not have sufficiently mobilized resources in support of the enabling environment for civil society abroad to date. Some also express concern that despite its shortcomings, the priority given to the issue under President Obama may not be sustainable once he leaves office.

Given these trends, it appears all but certain that Congress will continue to examine civil society developments and may seek ways in which to support civil society abroad, even as it grapples with the difficult choices inherent in overseeing foreign relations and assistance.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

In general, civil society includes individuals and organizations that voluntarily organize or engage on a range of issues of public interest or concern. While often used interchangeably with terms such as "nonprofit organizations" and "non-governmental organizations," civil society is generally recognized to also include a range of organizations such as labor unions, activist or civic coalitions, watchdog groups, professional associations, religious groups, political movements, and/or chambers of commerce. A broader discussion of the nature of the terminology describing this space is beyond the scope of this paper, but is available in studies such as Thomas Carothers, "Think Again: Civil Society," Foreign Policy, Winter 1999-2000. |

| 2. |

The authors of this report conducted numerous off-the-record interviews with a range of experts, including analysts, stakeholders, administration officials, former officials, academics, government offices, practitioners, etc. These interviews informed a significant amount of the research on expert views reflected in this report in addition to numerous resources explicitly cited throughout. While extensive, these interviews may not reflect the full scope of views on civil society and closing space. |

| 3. |

The White House, "Fact Sheet: U.S. Support for Civil Society," press release, September 29, 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/29/fact-sheet-us-support-civil-society. |

| 4. |

Kenneth Roth, "The Great Civil Society Choke-out," Foreign Policy, January 27, 2016. |

| 5. |

Maina Kiai, Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association A/70/266, p. 18, August 4, 2015. |

| 6. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Nongovernmental Organizations and Democracy Promotion: "Giving Voice to the People," A Report to Members, committee print, 109th Cong., 2nd sess., December 22, 2006, S.Prt.109-73, p. 1. |

| 7. |

Sarah E. Mendelson, Why Governments Target Civil Society and What Can Be Done in Response: A New Agenda, Center for Strategic & International Studies, April 2015, p. 2, http://csis.org/publication/why-governments-target-civil-society-and-what-can-be-done-response. |

| 8. |

Harriet Sherwood, "Human Rights Groups Face Global Crackdown 'not seen in a generation'," The Guardian, August 26, 2015. |

| 9. |

The publications cited in this section provide a variety of periodically updated data regarding restrictions on civil society, while not necessarily using consistent approaches, methodologies, or geographic scope. These studies are broadly referenced by experts and academics, but their inclusion in this report should not necessarily be interpreted as an endorsement of their methodology by the Congressional Research Service. |

| 10. |

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation, State of Civil Society Report 2015, July 7, 2015, p. 6, http://civicus.org/images/StateOfCivilSocietyFullReport2015.pdf. |

| 11. |

Arch Puddington, "Discarding Democracy: A Return to the Iron Fist," Freedom in the World, Freedom House, 2015. See https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2015/discarding-democracy-return-iron-fist. |

| 12. |

International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), Mapping Initiatives to Address Legal Constraints on Foreign Funding, August 20, 2014, http://www.icnl.org/news/2014/20-Aug.html. A senior U.S. official suggested in June 2015 that the number of countries that have considered or enacted restrictive measures since 2012 had grown to over 90. The White House, "Support, Defend, and Sustain: The Relevance of U.S. Response to Closing Civic Space," press release, June 24, 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/06/24/support-defend-and-sustain%E2%80%99-relevance-us-response-closing-civic-space. |

| 13. |

Douglas Rutzen, "Authoritarianism Goes Global (II): Civil Society Under Assault," Journal of Democracy, vol. 26, no. 4 (October 2015), pp. 28-39, http://www.icnl.org/news/2015/05_26.4_Rutzen.pdf. Rutzen is president and CEO of the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL, http://www.icnl.org). |

| 14. |

U.S. Agency for International Development, 2014 CSO Sustainability Index for Sub-Saharan Africa, https://www.usaid.gov/africa-civil-society. |

| 15. |

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) is a congressionally funded nonprofit organization created in 1983 to strengthen democratic institutions around the world. Through a worldwide grants program, NED assists those working abroad to build democratic institutions and spread democratic values. |

| 16. |

Alec Luhn, "National Endowment for Democracy is first 'undesirable' NGO banned in Russia," The Guardian, July 28, 2015. |

| 17. |

Alec Luhn, "American NGO to withdraw from Russia after being put on 'patriotic stop list'," The Guardian, July 22, 2015. |

| 18. |

Marton Dunai and Balazs Koranyi, "Hungary raids NGOs, accuses Norway of political meddling," Reuters, June 2, 2014. |

| 19. |

Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher, Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2014, p. 19. |

| 20. |

Thomas Carothers, The Closing Space Challenge: How Are Funders Responding?, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 2015, p. 9, http://carnegieendowment.org/files/CP_258_Carothers_Closing_Space_Final.pdf. |

| 21. |

See, e.g., Michael Lund, Peter Ulvin, and Sarah Cohen, "Building Civil Society in Post-Conflict Environments: From the Micro to the Macro," What Really Works in Preventing and Rebuilding Failed States Occassional Paper Series, Issue 1, November 2006, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/OCpaper.pdf. |

| 22. |

Country information compiled from International Center for Not-for-Profit Law's NGO Law Monitor, http://www.icnl.org/; Thomas Carothers, The Closing Space Challenge: How are Funders Responding?, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 2015; and Sherwood, op. cit. |

| 23. |

Amy Fallon, "Uganda: Repressive NGO Act," AllAfrica, March 9, 2016. |

| 24. |

Christopher Walker, Marc Plattner, and Larry Diamond, "Authoritarianism Goes Global," The American Interest, March 28, 2016. |

| 25. |

See, e.g. Kenneth Roth, "Twin Threats: How the Politics of Fear and the Crushing of Civil Society Imperil Global Rights," Human Rights Watch, October 4, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2016/twin-threats. |

| 26. |

See CRS Report R44018, Burundi's Political Crisis, by Emily Renard and Alexis Arieff. |

| 27. |

See, e.g., Anastasia Moloney, "Honduras most dangerous country for environmental activists–report–TRFN," Reuters, April 20, 2015. |

| 28. |

Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher, Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, DC, February 20, 2014, pp. 21-30, http://carnegieendowment.org/2014/02/20/closing-space-democracy-and-human-rights-support-under-fire. |

| 29. |