Housing Issues in the 115th Congress

A variety of housing-related issues were active during the 115th Congress. These issues included topics related to housing finance, tax provisions related to housing, housing assistance and grant programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and regulatory review efforts underway at HUD. In some cases, the 115th Congress considered or passed legislation related to certain housing issues, such as mortgage-related provisions enacted as part of broader financial “regulatory relief” legislation and particular housing-related tax provisions. In other cases, Congress conducted oversight or otherwise expressed interest in actions taken by HUD or other entities involved in housing, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Many of the housing-related topics that were of interest during the 115th Congress are ongoing issues, though some involved particular actions that took place during the 115th Congress. Issues of interest during the Congress included the following:

Housing finance issues included changes to certain mortgage-related requirements and other housing provisions included in broader financial legislation that became law in May 2018. Congress also expressed ongoing interest in certain issues related to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA): (1) a forthcoming final rule on FHA’s requirements for insuring mortgages on condominiums and (2) the level of the mortgage insurance premiums charged by FHA. Comprehensive housing finance reform that would address the status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is also an ongoing topic of interest, although the 115th Congress did not actively consider comprehensive housing finance reform legislation.

Tax issues included changes to housing-related tax provisions in the tax revision law enacted at the end of 2017 (P.L. 115-97); extensions of other, temporary housing-related tax provisions through 2017 by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123); and changes to the low-income housing tax credit in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141).

Housing assistance issues included considerations related to HUD appropriations, ongoing initiatives or proposed changes to HUD rental assistance programs, committee consideration of legislation to reauthorize the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA), issues related to the housing response to presidentially declared major disasters, and a variety of introduced bills that were meant to address housing affordability issues in various ways.

HUD began a variety of regulatory review efforts in keeping with Executive Order 13777, which directed federal agencies to evaluate existing regulations and identify opportunities for reform. Specific HUD actions included suspending a rule related to small-area fair market rents (the suspension has since been voided by a preliminary court injunction); initiating a broad review of manufactured housing regulations; suspending certain regulations governing how HUD funding recipients must comply with the requirement to affirmatively further fair housing; and publishing an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking seeking public comment on whether its regulations related to disparate impact and the Fair Housing Act should be amended.

Housing and mortgage market conditions provide important context for these issues, although housing markets are generally local in nature and national housing market indicators do not necessarily accurately reflect conditions in specific communities. Generally speaking, owner-occupied housing markets in recent years have been characterized by rising house prices, relatively low levels of housing starts and housing inventory, and relatively strong home sales. Rising house prices combined with rising mortgage interest rates have raised concerns about the affordability of buying a home, although interest rates remain low by historical standards. Rental housing markets have also raised affordability concerns. Nearly 21 million renter households are considered to be cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their incomes on rent. The share of households who rent, rather than own, their homes has increased in the years since the housing market turmoil that began around 2007, contributing to lower rental vacancy rates and increasing rents. Increases in household income in recent years have generally not kept pace with increases in house prices or rents, contributing to affordability concerns.

Housing Issues in the 115th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions

- Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market

- Rental Housing Markets

- Housing Finance Issues in the 115th Congress

- Financial "Regulatory Relief" Legislation and Housing

- Housing Finance Reform

- Federal Housing Administration Mortgage Insurance Premiums

- FHA Requirements for Insuring Mortgages on Condominium Units

- Housing-Related Tax Issues in the 115th Congress

- Housing Provisions in the Tax Revision Law

- Housing Provisions in Tax Extenders Legislation

- Changes to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

- Housing Assistance Issues in the 115th Congress

- HUD Appropriations

- HUD Rental Assistance Programs

- Native American Housing Programs

- Housing and Disaster Response

- Other Affordable Housing Proposals

- HUD Regulatory Reviews During the 115th Congress

- Small Area Fair Market Rents

- Manufactured Housing

- Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing

- Disparate Impact Standard under the Fair Housing Act

Figures

- Figure 1. Year-over-Year House Price Changes (Nominal)

- Figure 2. Mortgage Interest Rates

- Figure 3. Housing Starts

- Figure 4. New and Existing Home Sales

- Figure 5. Share of Mortgage Originations by Type

- Figure 6. Rental and Homeownership Rates

- Figure 7. Rental Vacancy Rates

- Figure 8. Share of Cost-Burdened Renter Households by Income

Summary

A variety of housing-related issues were active during the 115th Congress. These issues included topics related to housing finance, tax provisions related to housing, housing assistance and grant programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and regulatory review efforts underway at HUD. In some cases, the 115th Congress considered or passed legislation related to certain housing issues, such as mortgage-related provisions enacted as part of broader financial "regulatory relief" legislation and particular housing-related tax provisions. In other cases, Congress conducted oversight or otherwise expressed interest in actions taken by HUD or other entities involved in housing, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Many of the housing-related topics that were of interest during the 115th Congress are ongoing issues, though some involved particular actions that took place during the 115th Congress. Issues of interest during the Congress included the following:

- Housing finance issues included changes to certain mortgage-related requirements and other housing provisions included in broader financial legislation that became law in May 2018. Congress also expressed ongoing interest in certain issues related to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA): (1) a forthcoming final rule on FHA's requirements for insuring mortgages on condominiums and (2) the level of the mortgage insurance premiums charged by FHA. Comprehensive housing finance reform that would address the status of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is also an ongoing topic of interest, although the 115th Congress did not actively consider comprehensive housing finance reform legislation.

- Tax issues included changes to housing-related tax provisions in the tax revision law enacted at the end of 2017 (P.L. 115-97); extensions of other, temporary housing-related tax provisions through 2017 by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123); and changes to the low-income housing tax credit in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141).

- Housing assistance issues included considerations related to HUD appropriations, ongoing initiatives or proposed changes to HUD rental assistance programs, committee consideration of legislation to reauthorize the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act (NAHASDA), issues related to the housing response to presidentially declared major disasters, and a variety of introduced bills that were meant to address housing affordability issues in various ways.

- HUD began a variety of regulatory review efforts in keeping with Executive Order 13777, which directed federal agencies to evaluate existing regulations and identify opportunities for reform. Specific HUD actions included suspending a rule related to small-area fair market rents (the suspension has since been voided by a preliminary court injunction); initiating a broad review of manufactured housing regulations; suspending certain regulations governing how HUD funding recipients must comply with the requirement to affirmatively further fair housing; and publishing an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking seeking public comment on whether its regulations related to disparate impact and the Fair Housing Act should be amended.

Housing and mortgage market conditions provide important context for these issues, although housing markets are generally local in nature and national housing market indicators do not necessarily accurately reflect conditions in specific communities. Generally speaking, owner-occupied housing markets in recent years have been characterized by rising house prices, relatively low levels of housing starts and housing inventory, and relatively strong home sales. Rising house prices combined with rising mortgage interest rates have raised concerns about the affordability of buying a home, although interest rates remain low by historical standards. Rental housing markets have also raised affordability concerns. Nearly 21 million renter households are considered to be cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their incomes on rent. The share of households who rent, rather than own, their homes has increased in the years since the housing market turmoil that began around 2007, contributing to lower rental vacancy rates and increasing rents. Increases in household income in recent years have generally not kept pace with increases in house prices or rents, contributing to affordability concerns.

Introduction

A variety of issues related to housing were active during the 115th Congress, including issues related to housing finance, housing-related tax provisions, housing assistance and grant programs (including in response to presidentially declared major disasters), and actions undertaken by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as part of its efforts to review existing department regulations. This report provides a high-level overview of the most prominent housing-related issues during the Congress, including brief background on each and discussion of legislative or other relevant activity.

This report is meant to provide a broad overview of major issues and is not intended to provide detailed information or analysis. However, it includes references to more in-depth CRS reports on the issues where possible.

Housing and Mortgage Market Conditions

This section provides background on housing and mortgage market conditions to provide context for the housing policy issues discussed later in the report. This discussion of market conditions is at the national level; however, it is important to be aware that local housing market conditions can vary dramatically, and national housing market trends may not reflect the conditions in a specific area. Nevertheless, national housing market indicators can provide an overall sense of general trends in housing.

For several years since the housing and financial market turmoil of the late 2000s, housing markets have been recovering from house price declines, high rates of mortgage foreclosures, and other symptoms of the housing crisis. While some areas of the country have not fully recovered, most housing market indicators have rebounded. For example, house prices have been increasing for several years, and in many areas have passed their pre-crisis peaks in nominal terms; foreclosure rates have generally declined to levels similar to the years preceding the housing market turmoil; and housing market activity in general is increasing. As many communities have recovered, other housing market conditions have received increased attention. Some of the most prominent considerations that are often discussed in relation to current housing markets include the following:

- Affordability of Both Owner-Occupied and Rental Housing: In many areas of the country, housing affordability has been an ongoing issue for both homebuyers and renters. House prices and rental costs have increased in recent years and have generally increased faster than incomes. Despite concerns about the affordability of owner-occupied housing, many metrics suggest that homeownership is currently relatively affordable by historical standards; however, such measures generally focus on the ability of households to afford monthly mortgage payments and do not consider other costs of purchasing a home, such as saving for a down payment.

- Housing Inventory: The available housing inventory is one factor that affects housing affordability, as too few homes available for sale or rent can increase home prices or rents. Limited inventory, particularly of modestly priced housing, appears to be impacting affordability and home sales in many housing markets. Relatively low levels of new home construction is one of the factors contributing to lower levels of housing inventory.

- Mortgage Access: The availability of mortgage credit tightened in the aftermath of the housing crisis, for a variety of reasons. While credit is not currently as tight as it was at the peak, some argue that it is still too difficult for some creditworthy households to obtain affordable mortgages. Others, however, argue that mortgage standards are loosening too much for certain types of mortgages.

The following subsections provide an overview of selected indicators reflecting conditions in owner-occupied housing markets and the mortgage market, and rental markets, respectively, during the 115th Congress. Some of the included graphics show housing market indicators over time; these graphics highlight the time period of the 115th Congress to allow readers easily to see the levels and trends in these indicators during the Congress. In some cases, these graphics include data for the entire 115th Congress (2017-2018), while in other cases data covering the full time period of the 115th Congress were not available as of the date of the final update of this report.

Owner-Occupied Housing Markets and the Mortgage Market

Over the past few years, on a national level, markets for owner-occupied housing have generally been characterized by rising home prices, low inventory levels, housing starts that are increasing but remain relatively low by historical standards, and home buying activity that is beginning to return to pre-crisis levels. Housing starts remain below the levels seen in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. For the most part, mortgage foreclosures1 and negative equity,2 which characterized the housing and economic turmoil that began around 2007, have eased.3 However, national statistics can mask the experience of local housing markets, and not all communities have recovered equally from the effects of the housing crisis.4

Most homebuyers take out a mortgage to purchase a home. Therefore, owner-occupied housing markets are closely linked to the mortgage market, although they are not the same. The ability of prospective homebuyers to obtain mortgages and the costs of those mortgages impact housing demand and affordability.

House Prices

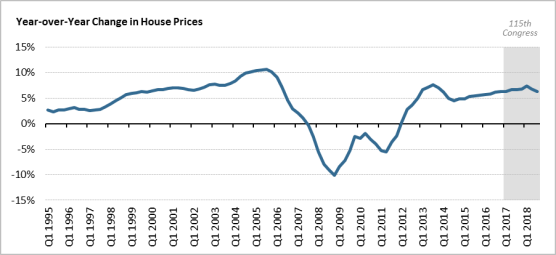

As shown in Figure 1, on a national basis, nominal house prices have been increasing on a year-over-year basis in each quarter since the beginning of 2012. Year-over-year house price changes have been above 5% in each quarter since the second quarter of 2015 and over 6% since mid-2017. These increases follow almost five years of house price declines in the years during and surrounding the economic recession of 2007-2009 and associated housing market turmoil.

House prices vary greatly across local housing markets. In some areas of the country, prices have fully regained or even exceeded their pre-recession levels in nominal terms, while in other areas prices remain below those levels.5 Furthermore, house price increases affect participants in the housing market differently. Rising prices reduce affordability for prospective homebuyers, but they are generally beneficial for current homeowners, who benefit from the increased home equity that accompanies them (although rising house prices also have the potential to negatively impact affordability for current homeowners through increased property taxes).

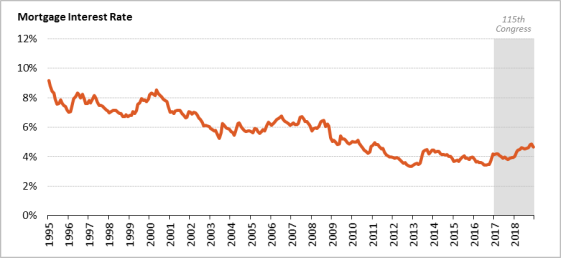

Mortgage Interest Rates

For several years, mortgage interest rates have been low by historical standards. As shown in Figure 2, average mortgage interest rates have been consistently below 5% since May 2010 and have been below 4% for several stretches during that time. Lower interest rates increase mortgage affordability and make it easier for some households to purchase homes or refinance their existing mortgages.

Mortgage interest rates have generally increased since the start of 2018, though they decreased somewhat in December 2018, ending the year at 4.64%. Rising interest rates may make mortgages less affordable for some households, contributing to homeownership affordability pressures.

|

Figure 2. Mortgage Interest Rates January 1995–December 2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from Freddie Mac's Primary Mortgage Market Survey, 30-Year Fixed Rate Historic Tables, available at http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/. Notes: Freddie Mac surveys lenders on the interest rates they are charging for certain types of mortgage products. The actual interest rate paid by any given borrower will depend on a number of factors. |

Owner-Occupied Housing Affordability

As house prices have been rising for several years on a national basis, and as mortgage interest rates have also begun to rise, concerns about the affordability of owner-occupied housing have increased. Incomes have also been rising in recent years, helping to mitigate some affordability pressures, but in general incomes have not been rising as quickly as house prices.6

Despite rising house prices, many metrics of housing affordability suggest that owner-occupied housing is currently relatively affordable. These metrics generally measure the share of income that a median-income family would need to qualify for a mortgage to purchase a median-priced home, subject to certain assumptions.7 Therefore, rising incomes and, especially, interest rates that are still low by historical standards contribute to homes, and borrowers' monthly mortgage payments in particular, being considered affordable despite recent house price increases.8

Some factors that affect housing affordability may not be captured by these metrics, however. For example, many of the metrics are based on certain assumptions (such as a borrower making a 20% down payment) that may not apply to many households. Furthermore, since they typically measure the affordability of monthly mortgage payments, they often do not take into account other affordability challenges that homebuyers may face, such as affording a down payment and other upfront costs of purchasing a home (costs that generally increase as home prices rise). Other factors—such as the ability to qualify for a mortgage, the availability of homes on the market, and regional differences in house prices and income—may also make homeownership less attainable for some households.9 Finally, some of these factors may have a bigger impact on affordability for certain specific demographic groups, as income trends and housing preferences are not uniform across all segments of the population.10

To the extent that house prices and interest rates continue to increase, housing affordability could become more of an issue going forward.11

Inventory and Housing Starts

Many market observers have pointed to low levels of housing inventory as being a key contributor to rising house prices.12 One measure of the housing inventory is the months' supply of new and existing homes for sale—that is, how many months it would take for all of the homes that are currently on the market to sell based on the current pace of home sales, assuming no additional homes were placed on the market. According to HUD, using data from the National Association of Realtors and the U.S. Census Bureau, the months' supply of homes for sale has generally been below the historical average of six months of late, and the inventory of homes for sale has been low for several years.13

One factor that affects housing inventory is the decision of existing homeowners to put their homes on the market. A number of considerations may be impacting owners' decisions about whether to sell their homes, including concerns about being able to find a suitable new home to purchase. Another factor that affects the housing inventory is the amount of new construction. In recent years, levels of new construction have been relatively low by historical standards, reflecting a variety of considerations including labor shortages and the cost of building.14

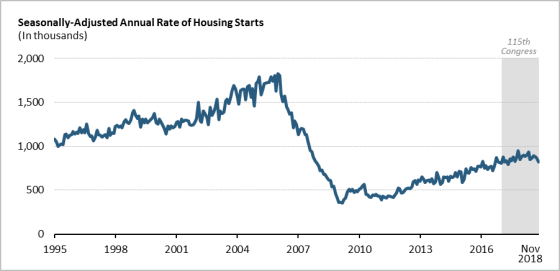

One measure of the amount of new construction is housing starts. Housing starts are the number of new housing units on which construction is started in a given period and are typically reported monthly as a "seasonally adjusted annual rate." This means that the number of housing starts reported for a given month (1) has been adjusted to account for seasonal factors and (2) has been multiplied by 12 to reflect what the total number of housing starts would be if the current month's pace continued for an entire year. That is, the number reported for a given month is the annual number of housing starts that would result if the number of starts per month continued at the current month's rate for 12 months.15

Figure 3 shows the seasonally adjusted annual rate of starts on one-unit homes for each month from January 1995 through November 2018.

|

January 1995–November 2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, New Residential Construction Historical Data, http://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/historical_data/. Data are through November 2018. Notes: Figure reflects starts in one-unit structures only, some of which may be built for rent rather than sale. The seasonally adjusted annual rate is the number of housing starts that would be expected if the number of homes started in that month (on a seasonally adjusted basis) were extrapolated over an entire year. |

Housing starts for single-family homes fell during the housing market turmoil, reflecting decreased home purchase demand. In recent years, as demand has increased, housing starts have been mostly increasing as well, though they remain below the levels seen in the late 1990s and early 2000s. From 2000 through 2007, the seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing starts in one-unit residential buildings was generally between 1.2 million and 1.8 million each month, before falling to a rate of between 400,000 and 600,000 for each month until about 2013. More recently, housing starts have been trending upward, and the seasonally adjusted annual rate averaged about 850,000 during 2017. In November 2018, the seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing starts was 824,000.

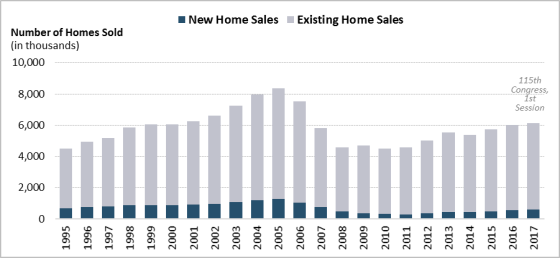

Home Sales

Despite limited inventory and rising home prices, home sales have been increasing in recent years. Home sales include sales of both existing and newly built homes. Existing home sales generally number in the millions each year, while new home sales are usually in the hundreds of thousands.

Figure 4 shows the annual number of existing and new home sales for each year from 1995 through 2017. Existing home sales numbered about 5.5 million in 2017, representing the third straight year of increases and the highest level since 2006. New home sales numbered about 614,000 in 2017. This was the highest level since 2007, but the number of new home sales remains appreciably lower than in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when they tended to be between 800,000 and 1 million per year.16

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from HUD's U.S. Housing Market Conditions reports, available at https://www.huduser.gov/portal/ushmc/home.html; the National Association of Realtors Existing Home Sales Overview Chart at https://www.nar.realtor/topics/existing-home-sales; and the U.S. Census Bureau, New Residential Sales Historical Data, Houses Sold (Annual), https://www.census.gov/construction/nrs/historical_data/index.html. |

Mortgage Credit Access

Some prospective homebuyers may find themselves unable to obtain mortgages due to their credit histories, other financial characteristics, the cost of obtaining a mortgage (such as down payments and closing costs), or other factors. In general, it is beneficial to the housing market when creditworthy homebuyers are able to obtain mortgages to purchase homes. However, access to mortgages must be balanced against the risk of offering them to people who will not be willing or able to repay the money they borrowed. Striking the right balance of credit access and risk management and the question of who is considered to be "creditworthy" are subjects of ongoing debate.

A variety of organizations attempt to measure the availability of mortgage credit. While their methods vary, many experts agree that access to mortgage credit is tighter than it was in the early 2000s, prior to the housing bubble that preceded the housing market turmoil later in the decade, although it has eased somewhat of late. Despite this easing, some have argued that access to mortgage credit is still too tight, and that the mortgage market is taking on less default risk than it did in the years prior to the loosening of credit standards during the housing bubble.17

Others have argued that mortgage credit standards are easing too much, focusing on the fact that credit standards for certain types of mortgages, such as those insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), have appeared to loosen somewhat in recent years compared to the immediate aftermath of the housing market turmoil when standards tightened across the board. They argue that easing credit standards unsustainably increases the risk of certain types of mortgages and contributes to higher house prices by allowing households to leverage higher amounts of mortgage debt.18 FHA itself has noted that it is monitoring certain trends, such as a larger share of new FHA-insured mortgages with higher debt-to-income ratios and the performance of loans with certain types of down payment assistance, that have the potential to increase risk to FHA.19

Mortgage Market Composition

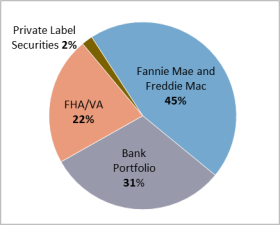

When a lender originates a mortgage, it can choose to hold that mortgage in its own portfolio, sell it to a private company, or sell it to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, two congressionally chartered government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bundle mortgages into securities and guarantee investors payments on those securities. Furthermore, a mortgage might be insured by a federal government agency, such as the FHA or the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Most FHA-insured or VA-guaranteed mortgages are included in mortgage-backed securities that are guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, another government agency.20

In the years after the housing bubble burst, there was an increase in the share of mortgages that either had mortgage insurance from a government agency or were guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, leading some to express concern about increased government exposure to risk and a lack of private capital in the mortgage market.

As shown in Figure 5, about two-thirds of the total dollar volume of mortgages originated during the first three-quarters of 2018 were either guaranteed by a federal agency such as FHA or VA (22%) or backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (45%). Close to one-third of the dollar volume of mortgages originated was held in bank portfolios (31%), while about 2% was securitized in the private market.

The share of new mortgage originations, by dollar volume, insured by a federal agency or guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac has fallen from a high of nearly 90% in 2009, during the housing market turmoil. Nevertheless, the share of mortgage originations with federal mortgage insurance or a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac guarantee remains elevated compared to the 2002-2007 period, when FHA and VA mortgages constituted a small share of the mortgage market and the GSE share ranged from about 30% to 50%.21 The FHA and VA share of mortgages during the 2002-2007 period was low by historical standards, however, as many households opted for other types of mortgages, including subprime mortgages, during that time.

Rental Housing Markets

In the years since the housing market turmoil began, the homeownership rate has decreased while the percentage of renter households has correspondingly increased. Although new rental housing units have also been created, both through new construction and as some formerly owner-occupied homes are converted to rentals, in many markets the rise in the number of renters increased competition for rental housing, leading to lower rental vacancy rates and higher rents in recent years.22 This, in turn, has resulted in more renter households being considered cost-burdened, commonly defined as paying more than 30% of income toward housing costs.

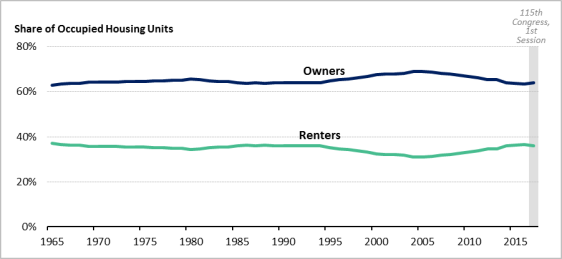

Share of Renters

As shown in Figure 6, the share of renters has generally been increasing for the last decade, reaching close to 37% of all occupied housing units in 2016. This was the highest share of renters since the early 1990s. The homeownership rate has correspondingly decreased, falling from a high of 69% in 2004 to just over 63% in 2016.23 Most recently, in 2017, the share of renters decreased slightly, to about 36%, and the homeownership rate increased slightly, to nearly 64%.

In addition to an increase in the share of households who rent, the overall number of renter households has been increasing as well. In 2016, there were nearly 43.3 million occupied rental housing units, compared to 40 million in 2013 and 35.9 million in 2008. The number of renter households decreased in 2017, to 43.1 million.24 (In comparison, the number of housing units occupied by an owner decreased somewhat after 2008 before beginning to rise again in recent years. The number of housing units occupied by owners was 76.6 million in 2017, compared to about 75.7 million in 2008.25)

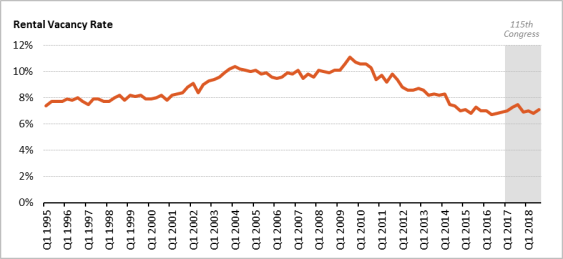

Vacancy Rates

In general, the increase in renters has led to a decrease in rental vacancy rates in many, though not all, areas of the country. This has been the case in many areas despite the creation of new rental units through both new construction and the conversion of some previously owner-occupied single-family units to rental housing. In many cases, the increase in the rental housing supply has not kept up with the increase in rental housing demand.

As shown in Figure 7, on a national basis the rental vacancy rate was over 10% in most quarters from 2008 through 2010. Since then, the rate has mostly declined, reaching about 8% at the end of 2013 and 7% at the end of each year from 2014 through 2017. The rental vacancy rate did increase somewhat throughout much of 2017, reaching 7.5% in the third quarter, before decreasing back to about 7% for most of 2018.26 Furthermore, the market for affordable rental units has been particularly tight, as many of the rental units that have been constructed in recent years have been at the higher end of the market.27

|

Figure 7. Rental Vacancy Rates Q1 1995–Q3 2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Housing Vacancies and Homeownership Historical Tables, Table 1, "Quarterly Rental Vacancy Rates: 1956 to Present," http://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/histtabs.html. |

Rental Housing Affordability

Rental housing affordability is impacted by a variety of factors, including the supply of rental housing units available, the characteristics of those units (e.g., age and amenities), and the demand for available units. As noted previously, new housing units have been added to the rental stock in recent years through both construction of new rental units and conversions of existing owner-occupied units to rental housing. At the same time, however, the demand for rental housing has increased as more households have become renters. Furthermore, much of the new rental housing construction in recent years has been higher-end construction rather than lower-cost units.28

The increased demand for rental housing, as well as the concentration of new rental construction in higher-cost units, has led to increases in rents in recent years. Median renter incomes have also been increasing for the last several years, at times outpacing increases in rents. However, over the longer term, median rents have increased faster than renter incomes. For example, between 2001 and 2017, in real terms the median rent (less utilities) for recent movers has risen over 25% while the median renter income has increased about 6%, reducing rental affordability over that time period.29

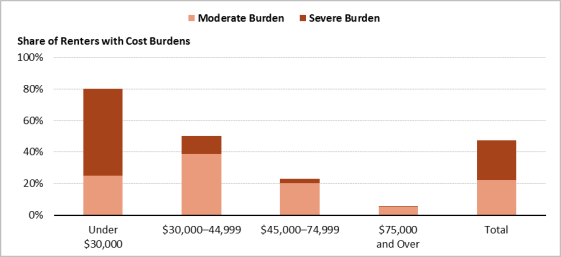

Rising rental costs and renter incomes that are not keeping up with rent increases over the long term can contribute to housing affordability problems, particularly for households with lower incomes. Under one common definition, housing is considered to be affordable if a household is paying no more than 30% of its income in housing costs. Under this definition, households that pay more than 30% are considered to be cost-burdened, and those that pay more than 50% are considered to be severely cost-burdened.

The overall number of cost-burdened renter households has generally increased in recent years, from 15.7 million in 2003 to 20.8 million in 2016, although the number of cost-burdened renter households in 2016 represented a decrease from over 21 million in both 2014 and 2015. (Over this time period, the overall number of renter households has increased as well.)

As shown in Figure 8, cost burdens are most prevalent among lower-income renter households. Among renter households with incomes below $30,000, 80% are cost-burdened, with over half experiencing severe cost burdens. However, cost burdens affect households of all incomes: half of renter households with incomes of at least $30,000 but less than $45,000, and over 20% of renter households with incomes of at least $45,000 but less than $75,000, were cost burdened in 2016. Moderate-income renter households have experienced some of the greatest increases in cost burdens since the early 2000s.30

Furthermore, according to HUD, 8.3 million renter households were considered to have "worst-case housing needs" in 2015 (the most recent data available).31 Households with worst-case housing needs are defined as renter households with incomes at or below 50% of area median income who do not receive federal housing assistance and who pay more than half of their incomes for rent, live in severely inadequate conditions, or both. The 8.3 million renter households with worst-case housing needs in 2015 represented an increase from 7.7 million in 2013 and was similar to 2011 (8.5 million households). In comparison, the number of renter households with worst-case housing needs in 2005 and 2007 was about 6 million.

Housing Finance Issues in the 115th Congress

Several of the issues that were of interest during the 115th Congress are related to the financing of housing. In some cases, these issues can impact the financing of both owner-occupied housing and rental housing, though in other cases they are primarily relevant to one or the other.

Financial "Regulatory Relief" Legislation and Housing

Background

The financial crisis of 2007-2009 led to a variety of legislative and regulatory responses intended to address its perceived causes. These responses included new requirements on financial institutions, some of which were related to mortgages. Many of these requirements were enacted in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) in 2010.32

In the years since, there has been ongoing debate about the extent to which the new requirements achieve the right balance of protecting consumers and the financial system from potentially risky mortgage features without unduly restricting access to credit for creditworthy households.

Recent Developments

During the 115th Congress, a variety of bills were considered to amend certain financial regulatory requirements, including requirements related to mortgages. Most notable among these for housing was the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174), which became law in May 2018.33 The act includes a variety of provisions related to financial regulatory requirements, including some mortgage-related requirements. In general, it modifies these mortgage-related requirements rather than eliminating them entirely. The act also includes some additional provisions related to housing.

Provisions of the act that modify mortgage-related requirements that were put in place after the housing market turmoil include the following:

- allowing certain mortgages originated and held in portfolio by small depository institutions to be considered "qualified mortgages" for the purposes of complying with the ability-to-repay rule;34

- making changes to requirements related to certain property appraisals;

- exempting some banks and credit unions that make fewer than a particular number of mortgage loans from specified new reporting requirements under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA);

- providing grace periods for individuals working as mortgage originators to obtain the proper licensing to originate mortgages in their new positions when they move from banks to nonbanks or across state lines;

- expanding the circumstances under which manufactured home retailers and their employees can be excluded from the definition of mortgage originators, and therefore exempt from certain requirements that apply to mortgage originators, subject to specified conditions; and

- waiving the waiting period between receipt of particular mortgage-related disclosures and the mortgage closing when a borrower is offered a lower interest rate after initial receipt of the disclosures.

While supporters of the act argued that these are targeted changes that will help to ease unnecessarily burdensome regulations and increase the availability of mortgage credit, opponents argued that they weaken or eliminate certain protections that were put in place in response to practices that harmed consumers and ultimately the broader mortgage market.

The act also includes several other mortgage- or housing-related provisions. These include the following:

- requirements intended to address concerns about certain refinancing practices related to some mortgages guaranteed by the Department of Veterans Affairs;

- making permanent specified protections for renters in foreclosed properties that had been put in place by the Protecting Tenants at Foreclosure Act (Title VII of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act, P.L. 111-22) in 2009 but had since expired;

- making permanent a one-year protection against foreclosure for active duty servicemembers under particular circumstances;

- requiring Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to consider alternative credit scoring models for mortgages purchased by those institutions;

- making Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) loans, which allow some homeowners to finance specified energy improvements through property tax assessments, subject to the ability-to-repay requirements that apply to most mortgages;

- certain changes related to small public housing agencies;

- changes to HUD's Family Self-Sufficiency program, an asset-building program for residents of public and assisted housing; and

- requiring certain reports, including a report by HUD on lead paint hazards and abatement and a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on foreclosures in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

Additional information:

- For an expanded discussion of the provisions of P.L. 115-174, see CRS Report R45073, Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) and Selected Policy Issues.

Housing Finance Reform

Background

The U.S. housing finance system supports about $10 trillion in outstanding single-family residential mortgage debt and over $1 trillion in multifamily residential mortgage debt.35 Two major players in the housing finance system are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that were created by Congress to provide liquidity to the mortgage market. By law, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac cannot make mortgages; rather, they are restricted to purchasing mortgages that meet certain requirements from lenders. Once the GSEs purchase a mortgage, they either package it with others into a mortgage-backed security (MBS), which they guarantee and sell to institutional investors, or retain it as a portfolio investment. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are involved in both single-family and multifamily housing, though their single-family businesses are much larger.

In 2008, during the housing and mortgage market turmoil, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac entered voluntary conservatorship overseen by their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). As part of the legal arrangements of this conservatorship, the Department of the Treasury contracted to purchase over $200 billion of new senior preferred stock from each of the GSEs; in return for this support, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac pay dividends on this stock to Treasury.36 To date, Treasury has purchased a total of over $191 billion of senior preferred stock from the two GSEs and has received a total of nearly $280 billion in dividends.37 These funds become general revenues. Since the first quarter of 2012, the only time Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have drawn on their lines of credit with Treasury was in the fourth quarter of 2017; this draw was attributed to changes in the value of deferred tax assets as a result of the tax revision law that was enacted in late 2017 (P.L. 115-97).38

Recent Developments

Since Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed in conservatorship in 2008, policymakers have largely agreed on the need for comprehensive housing finance reform legislation that would transform or eliminate the GSEs' role in the housing finance system. While there is broad agreement on certain principles of housing finance reform—such as increasing the private sector's role in the mortgage market and maintaining access to affordable mortgages for creditworthy households—there is disagreement over how best to achieve these objectives and over the technical details of how a restructured housing finance system should operate.

The 113th Congress considered, but did not enact, housing finance reform legislation.39 The 114th Congress considered a number of more-targeted reforms to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but did not actively consider comprehensive housing finance reform legislation.40 During the 115th Congress, Members on the House and Senate committees of jurisdiction and Administration officials indicated that housing finance reform would be a priority.41 However, little formal legislative action on the issue took place, and in July 2018, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin suggested at a House Financial Services Committee hearing that housing finance reform would be a focus in the 116th Congress.42

In September 2018, House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling released a discussion draft of a comprehensive housing finance reform bill with some bipartisan support.43 Chairman Hensarling also indicated plans to reintroduce the Protecting American Taxpayers and Homeowners Act (PATH Act) from the 113th Congress, which takes a different approach to housing finance reform. However, noting that the reintroduced PATH Act (H.R. 6746) was considered unlikely to pass, he said that he would pursue the discussion draft bill as an alternative.44 The Financial Services Committee held a hearing on the discussion draft bill in December 2018.45

In addition to considering the role of the GSEs in the housing finance system, any future housing finance reform legislation could also consider changes to the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). FHA is a part of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and insures certain mortgages made by private lenders against the possibility of borrower default. By insuring these mortgages, FHA helps to make affordable mortgages more available to borrowers who might otherwise not be well-served by the private mortgage market, such as borrowers with low down payments.

Apart from comprehensive reform of the housing finance system, several additional issues related to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac received attention during the 115th Congress. These included (1) an FHFA decision to allow Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to each retain $3 billion in capital (under the terms of the Treasury support agreements, the amount of capital they are allowed to retain was scheduled to fall to zero at the beginning of 2018), (2) the need for both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to draw on their lines of credit with Treasury in the fourth quarter of 2017 due to a reduction in the value of deferred tax assets as a result of the tax revision law passed in late 2017, and (3) FHFA directing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to continue to make required contributions to certain affordable housing funds despite the draw from Treasury. For more information on these issues in particular, see CRS In Focus IF10851, Housing Finance: Recent Policy Developments.

Additional information:

- For background on the housing finance system in general, see CRS Report R42995, An Overview of the Housing Finance System in the United States.

- For information on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and their conservatorship, see CRS Report R44525, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions.

- For background on FHA, see CRS Report RS20530, FHA-Insured Home Loans: An Overview.

Federal Housing Administration Mortgage Insurance Premiums

Background

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), part of HUD, insures certain mortgages made by private lenders against the possibility of the borrower defaulting. FHA insurance protects the lender in the event of borrower default, which is intended to increase the availability of affordable mortgage credit to households who might otherwise be underserved by the private mortgage market.

FHA charges borrowers both upfront and annual fees, referred to as mortgage insurance premiums, in exchange for this insurance. These fees are supposed to cover the costs of paying a claim to a lender if an FHA-insured mortgage defaults and goes to foreclosure. By law, the HUD Secretary has a responsibility to ensure that the FHA single-family mortgage insurance fund remains financially sound46 and that the fund is in compliance with a requirement that it maintain a capital ratio of at least 2%.47

FHA raised the premiums it charges several times in the years during and following the housing market turmoil in response to concerns about rising mortgage delinquency rates and FHA's ability to maintain compliance with the capital ratio requirement. It then lowered the annual premiums in 2015 as mortgage delinquency rates began to decrease and its financial position stabilized. The level of the premiums charged by FHA is often a topic of interest. The premiums have implications for the affordability and availability of FHA-insured mortgages for certain homebuyers, on the one hand, and for the financial health of the FHA insurance fund, on the other; setting the appropriate premium level involves balancing these considerations.

Recent Developments

Early in January 2017, HUD announced that it planned to decrease the annual mortgage insurance premium it charged for new mortgages that closed on or after January 27, 2017.48 However, on January 20, 2017, the first day of the Trump Administration, HUD suspended the planned decrease before it went into effect, citing a need to further analyze the potential impact that a mortgage insurance premium decrease could have on the FHA insurance fund.49

In its Annual Report to Congress on the Financial Status of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMI Fund) in November 2017, FHA stated that had the planned premium decrease gone into effect, the estimated capital ratio for the MMI Fund would have fallen below the statutorily mandated capital ratio requirement of 2% for FY2017.50 (The actual estimated capital ratio for FY2017 was lower than FY2016, but remained above 2%.) The estimated lower capital ratio would have been due to a combination of (1) less premium revenue coming into the fund as a result of the lower premiums and (2) an increase in the total dollar amount of mortgages that would have been insured as a result of more borrowers obtaining FHA-insured mortgages due to the lower premiums. The report also suggests, however, that reverse mortgages insured by FHA are having a disproportionately negative impact on the insurance fund, raising questions about the extent to which the performance of the reverse mortgage portfolio may, or should, impact decisions about the premiums charged to forward-mortgage borrowers.51

Additional information:

- For more information on FHA-insured mortgages in general, including the current premium levels, see CRS Report RS20530, FHA-Insured Home Loans: An Overview.

- For more information on the financial status of FHA's single-family mortgage insurance fund, see CRS Report R42875, FHA Single-Family Mortgage Insurance: Financial Status of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund (MMI Fund).

FHA Requirements for Insuring Mortgages on Condominium Units

Background

FHA-insured mortgages can be used to purchase condominium units as well as other types of single-family homes. However, HUD places specific requirements on FHA-insured mortgages for condominiums that may affect the eligibility of a condominium mortgage for the insurance.

In order for FHA to insure a mortgage on a condominium unit, HUD requires that the entire condominium project where the unit is located have FHA approval. In order for the condominium project to be approved, it must meet a variety of requirements. These include, among others, a minimum percentage of units that must be owner-occupied, and limits on the amount of nonresidential space and the percentage of units that are behind on their association dues. Condominium buildings seeking FHA approval must go through a certification process and a periodic recertification process to maintain FHA approval.

In 2009, HUD made a number of changes related to condominium mortgage insurance.52 In addition to tightening several requirements, it ended a practice known as "spot approval," in which a mortgage on a condominium located in a project that did not have FHA approval could qualify for FHA insurance on a case-by-case basis. Requirements placed on condominium projects seeking FHA approval are intended to ensure that the buildings themselves are well-managed and financially stable, which in turn is thought to make mortgages on individual units in the building less risky. However, some industry groups and others have argued that many of the changes that FHA made are too strict and unnecessarily reduce access to FHA-insured mortgages for prospective condominium buyers and for condominium owners who seek FHA-insured reverse mortgages.53

While the specifics of debates around individual requirements related to FHA approval of condominium buildings may vary, in general the debate around these requirements is usually framed as a question of how to balance access to FHA-insured mortgages with making sure that insured mortgages do not pose an undue risk to the financial health of the FHA insurance fund.

Recent Developments

In July 2016, towards the end of the 114th Congress, the Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (HOTMA, P.L. 114-201) was enacted. While most of the provisions of HOTMA affected HUD rental assistance programs, there were four provisions related to FHA's requirements for insuring mortgages on condominium units. These provisions directed the HUD Secretary to (1) streamline the recertification process for FHA approval of condominium buildings to make it less burdensome, (2) make changes to the process for granting exceptions for exceeding FHA's limits on commercial space, (3) adopt Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) regulations related to transfer fees and condominiums,54 and (4) issue new guidance, and a justification, addressing the required percentage of owner-occupied units in the building.55

In September 2016, during the 114th Congress, HUD issued a comprehensive proposed rule related to approval of condominium projects.56 While this rulemaking takes the HOTMA provisions into account, it is broader than just the areas addressed by HOTMA and had been in the development stages prior to the passage of the act. Among other things, it proposed a single-unit approval process, similar to the previous spot approval process, to provide a way for FHA-insured mortgages to be approved for condominiums in buildings that are not FHA-approved, subject to certain conditions.

In June 2018, over a hundred Members of Congress signed a letter to HUD urging it to finalize the rule.57 As of the end of the 115th Congress, HUD had not yet issued a final rule.

Additional information:

- For more information on the condominium-related provisions included in HOTMA, see CRS Report R44358, Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (H.R. 3700).

Housing-Related Tax Issues in the 115th Congress

During the 115th Congress, a number of housing-related tax provisions were modified or extended through different pieces of enacted legislation: a broad tax revision law that included changes to housing-related tax provisions, tax extenders legislation that extended temporary tax provisions related to housing, and an appropriations law that included changes to the low-income housing tax credit.

Housing Provisions in the Tax Revision Law

Background

Two of the largest and most well-known tax incentives available to homeowners are the mortgage interest deduction and the deduction for property taxes.

Homeowners are allowed to deduct interest paid on a mortgage that finances the acquisition of a primary or secondary residence as long as the homeowner itemizes their tax deductions. Historically, the amount of interest that was allowed to be deducted was limited to the interest incurred on the first $1 million of combined mortgage debt and the first $100,000 of home equity debt ($1.1 million total). If a taxpayer's mortgage debt exceeded $1 million, they were still allowed to claim a deduction for a percentage of interest paid.58 Homeowners also benefit from the ability to deduct state and local property taxes. Historically, homeowners were allowed to claim an itemized deduction equal to the full amount of state and local property taxes paid.

Not all homeowners claim these deductions. Some have no mortgage, and hence no interest to deduct. Others may be toward the end of their mortgage repayment period, and thus paying relatively little interest, so the deduction for interest is not worth much. Some homeowners live in states with low state and local taxes, and may find the standard deduction to be more valuable. Some may also live in low-cost areas and therefore have a relatively small mortgage and property taxes. There may also be interactions with other drivers of itemization. For example, itemization rates tend to be lower in states with an income tax, which can also lead to fewer homeowners claiming the deductions for mortgage interest and property taxes.

Among households that do claim the deductions, the majority of their advantages tend to benefit those with higher income. This is in part because these households are more likely to have a financial incentive to itemize their taxes and claim the deductions. It is also because higher-income households are more likely to have more expensive homes with larger mortgages, and therefore more likely to have higher property taxes and larger amounts of mortgage interest to deduct, and because the tax benefits increase with higher marginal tax rates in higher income brackets.

Some have argued that the ability to deduct mortgage interest and property taxes incentivize homeownership and have pointed to several perceived benefits of homeownership as a rationale for these tax benefits. However, some researchers have suggested that these deductions have little effect on the homeownership rate, in part because they do not reduce the upfront cost of buying a home, which is one of the biggest barriers to homeownership for many households. This research suggests that the tax benefits may incentivize homebuyers to purchase larger homes than they otherwise would, however, because they increase households' purchasing power and the benefit of the deductions increases with more expensive homes and larger mortgages.

The above discussion draws from CRS Report R41596, The Mortgage Interest and Property Tax Deductions: Analysis and Options. Readers can refer to that report for a fuller exploration of these tax benefits, including the rationales put forward for them, an economic analysis of their effects, and a discussion of research related to their impact.

Recent Developments

In late 2017, a broad tax revision law (P.L. 115-97) that substantively changed the federal tax system was signed into law by President Trump. The legislation temporarily reduced the maximum amount of mortgage debt for which interest can be deducted to $750,000 ($375,000 for married filing separately) for debt incurred after December 15, 2017. For mortgage debt incurred on or before December 15, 2017, the combined mortgage limit remains $1 million ($500,000 for married filing separately). Refinanced mortgage debt will be treated as having been incurred on the date of the original mortgage for purposes of determining which mortgage limit applies ($750,000 or $1 million). The interest on a home equity loan that is secured by a principal or second residence and is used to buy, build, or substantially improve a taxpayer's home is still deductible, but the home equity loan amount counts towards the maximum eligible mortgage amount ($750,000 or $1 million). After 2025, the mortgage limit for all new and existing qualifying mortgage interest will revert to $1 million, plus $100,000 in home equity indebtedness (regardless of its use).

The 2017 tax revision also limits the deduction for state and local property and income taxes to $10,000 until the end of 2025. Additionally, P.L. 115-97 increased the standard deduction to $12,000 (single) or $24,000 (married), which is expected to further reduce the number of taxpayers who itemize deductions generally.

The increase in the standard deduction will mitigate the impact of the changes to the mortgage interest and property tax deductions for many households, though some will pay more in taxes as a result of these changes. The limit to the deduction for property taxes could have implications for some states and localities with high property taxes, and to the extent that the value of the mortgage interest deduction has been capitalized into home prices, the lower limits on the amount of mortgage interest that can be deducted could exert downward pressure on home prices in some areas. However, at this point the size and scope of any effects these changes may have is unclear.

Additional information:

- For more on how the tax revision law affected the mortgage interest deduction, see CRS Insight IN10845, P.L. 115-97: The Mortgage Interest Deduction.

Housing Provisions in Tax Extenders Legislation

Background

In the past, Congress has regularly extended a number of temporary tax provisions that address a variety of policy issues, including housing. This set of temporary provisions is commonly referred to as "tax extenders." Two housing-related provisions that have been included in tax extenders packages in the recent past are the exclusion for canceled mortgage debt, and the deduction for mortgage insurance premiums.

Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt

Historically, when all or part of a taxpayer's mortgage debt has been forgiven, the forgiven amount has been included in the taxpayer's gross income for tax purposes.59 This income is typically referred to as canceled mortgage debt income.

During the housing market turmoil of the late 2000s, some efforts to help troubled borrowers avoid foreclosure resulted in canceled mortgage debt.60 The Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-142), signed into law in December 2007, temporarily excluded qualified canceled mortgage debt income that is associated with a primary residence from taxation. The provision was originally effective for debt discharged before January 1, 2010, and was subsequently extended several times.

Rationales put forward for extending the exclusion have included minimizing hardship for distressed households, lessening the risk that nontax homeownership retention efforts will be thwarted by tax policy, and assisting in the recoveries of the housing market and overall economy. Arguments against the exclusion have included concerns that it makes debt forgiveness more attractive for homeowners, which could encourage homeowners to be less responsible about fulfilling debt obligations, and concerns about fairness as the ability to realize the benefits depends on a variety of factors.61 Furthermore, to the extent that housing markets and the economy have improved in recent years, and foreclosure rates have returned to more typical levels, some may argue that the exclusion is less necessary now than it may have been during the height of the housing and mortgage market turmoil.

Deductibility of Mortgage Insurance Premiums

As described earlier, homeowners traditionally have been able to deduct the interest paid on their mortgage, as well as property taxes they pay, as long as they itemize their tax deductions. Beginning in 2007, homeowners could also deduct qualifying mortgage insurance premiums as a result of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-432).62 Specifically, homeowners could effectively treat qualifying mortgage insurance premiums as mortgage interest, thus making the premiums deductible if homeowners itemized and their adjusted gross incomes were below a specified threshold ($55,000 for single, $110,000 for married filing jointly). Originally, the deduction was to be available only for 2007, but it was subsequently extended several times.

Two rationales that have been put forward for allowing the deduction of mortgage insurance premiums are the promotion of homeownership and the recovery of the housing market. However, it is not clear that the deduction has an effect on the homeownership rate, nor is it clear that the deduction is still needed to assist in the recovery of the housing market, given that housing market indicators suggest that it is stronger as a whole than when the provision was originally enacted (although some areas have not fully recovered from the housing market turmoil). Furthermore, to the degree that owner-occupied housing is over subsidized, extending the deduction could lead to a greater misallocation of resources that are directed toward the housing industry. Extending the deduction, however, may assist some households who are in financial distress because of burdensome housing payments.

Recent Developments

Congress most recently enacted tax extenders legislation in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). The legislation extended the exclusion for canceled mortgage debt and the ability to deduct mortgage insurance premiums, each of which had previously expired at the end of 2016, through the end of 2017. No additional tax extenders legislation was enacted during the 115th Congress.

Additional information:

- For more on the tax extenders in the Bipartisan Budget Act, see CRS Report R44925, Recently Expired Individual Tax Provisions ("Tax Extenders"): In Brief.

- For background on the tax exclusion for canceled mortgage debt, see CRS Report RL34212, Analysis of the Tax Exclusion for Canceled Mortgage Debt Income.

Changes to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Background

The low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) is one of the primary sources of federal funding that is used for affordable rental housing development, which it incentivizes with federal tax credits administered through the Internal Revenue Service. The tax credits are provided to states based on population, and states award the credits to housing developers that agree to build or rehabilitate housing where a certain percentage of units will be affordable to low-income households. Housing developers then sell the credits to investors and use the proceeds to help finance the housing developments.

Historically, LIHTC-assisted developments have had to meet one of two income tests: either a "20-50" test or a "40-60" test. Under the former, at least 20% of units have to be occupied by households with incomes at or below 50% of the area's median gross income (area median income, or AMI), adjusted for family size. Under the latter, at least 40% of the units have to be occupied by individuals with incomes at or below 60% of the area's median gross income, adjusted for family size.

Recent Developments

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) made two changes to the LIHTC program. The first change added a third option for complying with the income test for LIHTC developments in addition to the 20-50 or 40-60 tests. This option allows for income averaging, and the income test is satisfied if at least 40% of the units are occupied by tenants with an average income of no greater than 60% of AMI, and no individual tenant has an income exceeding 80% of AMI. Thus, for example, renting to someone with an income equal to 80% of AMI would also require renting to someone with an income no greater than 40% of AMI, so the tenants would have an average income equal to 60% of AMI. Proponents of income averaging have argued that it will have a variety of benefits, including potentially making it easier for LIHTC developments to include more deeply income-targeted units for households with the lowest incomes, increasing the number of households that are eligible to live in LIHTC properties, and making it easier to use LIHTC for mixed-income housing.63

The second change made by P.L. 115-141 increased the amount of LIHTC credits available to states by 12.5% per year for each of FY2018-FY2021.

The broader tax revision law (P.L. 115-97) did not make any changes directly to the LIHTC program. However, certain changes that were included in the law—such as reductions in corporate tax rates—could affect the demand for LIHTCs and the price that investors are willing to pay for them. If investors pay less for tax credits, then the credits would generate less money for affordable housing development, all else equal. The increase in tax credits included in P.L. 115-141 may help to alleviate concerns about the potential impact of the tax revision law on the price for LIHTCs.

Additional information:

- For more information on the low-income housing tax credit in general, and these recent changes to the program, see CRS Report RS22389, An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.

Housing Assistance Issues in the 115th Congress

Some of the housing-related issues that were active in the 115th Congress have to do with federal programs or activities that provide housing assistance to low-income households or other households with particular housing needs.

HUD Appropriations

Background

For several years, concern in Congress about federal budget deficits has led to increased interest in reducing the amount of discretionary funding provided each year through the annual appropriations process. This interest was most manifest by the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), which set enforceable limits for both mandatory and discretionary spending.64 The limits on discretionary spending, which have been amended and adjusted since they were first enacted,65 have implications for HUD's budget, the largest source of funding for direct housing assistance, because it is made up almost entirely of discretionary appropriations.66

More than three-quarters of HUD's appropriations are devoted to three rental assistance programs serving more than 4 million families: the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, Section 8 project-based rental assistance, and the public housing program. Funding for the HCV program and project-based rental assistance has been increasing in recent years, largely because of the increased costs of maintaining assistance for households that are currently served by the programs.67 Public housing has, arguably, been underfunded (based on studies undertaken by HUD of what it should cost to operate and maintain it) for many years.68 Despite the large share of total HUD funding these rental assistance programs command, their combined funding levels only permit them to serve an estimated one in four eligible families, which creates long waiting lists for assistance in most communities.69

In a budget environment featuring limits on discretionary spending, the pressure to provide increased funding to maintain current services for HUD's largest programs must be balanced against the pressure from states, localities, and advocates to maintain or increase funding for other HUD programs, such as the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, grants for homelessness assistance, and funding for Native American housing.

Recent Developments

The Trump Administration's budget requests for FY2018 and FY2019 each proposed decreases in funding for HUD as compared to the prior year. Both budget requests proposed to eliminate funding for several programs, including multiple HUD block grants (CDBG, the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, and the Self-Help and Assisted Homeownership Opportunity Program (SHOP)), and to decrease funding for most other HUD programs. In proposing to eliminate the block grant programs, the Administration cited budget constraints and proposed that state and local governments should take on more of a role in the housing and community development activities funded by these programs.

In February 2018, Congress enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of FY2018 (BBA; P.L. 115-123), which, among other things, increased the statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2018 and FY2019. Following passage of the BBA, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) was enacted in March 2018, providing final FY2018 appropriations for HUD. The enacted legislation increased overall funding for HUD by nearly 10% compared to FY2017 and did not adopt the program eliminations proposed in the President's budget request. Most HUD funding accounts saw increases in FY2018 compared to FY2017.

As of the end of the 115th Congress, final FY2019 appropriations for HUD had not yet been enacted. HUD programs and activities were funded under continuing resolutions through December 21, 2018, at which point funding lapsed. This funding lapse was still underway when the 115th Congress ended.

Additional information:

- For more on HUD appropriations trends in general, see CRS Report R42542, Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD): Funding Trends Since FY2002.

- For more on FY2018 HUD appropriations, see CRS Report R44931, HUD FY2018 Appropriations: In Brief.

- For more on the FY2019 HUD budget request, see CRS Report R45166, Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD): FY2019 Budget Request Fact Sheet.

HUD Rental Assistance Programs

Background

As noted, HUD administers three primary direct rental assistance programs: the Housing Choice Voucher program, the public housing program, and project-based rental assistance (including project-based Section 8). Combined, these programs serve more than 4 million families at a cost of nearly $40 billion per year, accounting for the vast majority of HUD's total budget. While the three programs provide different forms of assistance—rental vouchers, publicly owned subsidized apartments, and privately owned subsidized apartments—they all allow low-income individuals and families to pay rent considered affordable (generally 30% of adjusted family income). About half of the families served by the combined programs are headed by persons who are elderly or have disabilities and the other half are primarily other families with children. Although these are the largest federal housing assistance programs for low-income families, they are estimated to serve only approximately one in four eligible families due to funding limitations, and most communities have long waiting lists for assistance.

Recent Developments

The size and scope of HUD's rental assistance programs mean they are often of interest to policymakers. Specifically in the 115th Congress, cost considerations, interest in broader welfare reform ideas such as work requirements, and concerns about administrative efficiencies led to various policy proposals and debates.

Administration Rent Reform and Work Requirement Proposal

In April 2018, HUD Secretary Carson announced the Administration's Making Affordable Housing Work Act of 2018 (MAHWA) legislative proposal.70 If enacted, the proposal would have made a number of changes to the way tenant rents are calculated in HUD rental assistance programs. These changes would have resulted in rent increases for assisted housing recipients, and corresponding decreases in the cost of federal subsidies. Specifically, MAHWA proposed to eliminate the current income deductions used when calculating tenant rent and establish two rent structures: one for elderly and disabled households, based on 30% of gross income; and one for other families, based on 35% of gross income, with a mandatory minimum rent based on part-time work at the minimum wage. While these changes would have resulted in rent increases for tenants, the language would have allowed the Secretary to phase in the increases. Additionally, the proposal would have authorized the Secretary to establish other rent structures, and would have authorized local program administrators to establish still other rent structures, with the Secretary's authorization. Further, the proposal would have permitted local program administrators or property owners to institute work requirements for recipients. Given the variation that would have resulted from these last two elements permitting local discretion, it is difficult to estimate what the consequences of the changes would have been for any given family.71

In announcing the proposal, HUD described it as setting the programs on "a more fiscally sustainable path," creating administrative efficiency, and promoting self-sufficiency.72 Low-income housing advocates have been critical of the proposal, particularly the effect increased rent payments may have on families.73 Legislation to implement the Administration's proposal was not introduced in the 115th Congress.74

Rental Assistance Demonstration

The Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) was an Obama Administration initiative initially designed to test the feasibility of addressing the estimated $25.6 billion backlog in unmet capital needs in the public housing program75 by allowing local public housing authorities (PHAs) to convert their public housing properties to either Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers or Section 8 project-based rental assistance.76 PHAs are limited in their ability to mortgage, and thus raise private capital for, their public housing properties because of a federal deed restriction placed on the properties as a condition of federal assistance. When public housing properties are converted under RAD, that deed restriction is removed.77 As currently authorized, RAD conversions must be cost-neutral, meaning that the Section 8 rents the converted properties may receive must not result in higher subsidies than would have been received under the public housing program. Given this restriction, and without additional subsidy, not all public housing properties can use a conversion to raise private capital, potentially limiting the usefulness of a conversion for some properties.78

RAD was first authorized by Congress in the FY2012 HUD appropriations law and was originally limited to 60,000 units of public housing (out of roughly 1 million units).79 However, Congress has since expanded the demonstration. Most recently, in FY2018, Congress raised the cap so that up to 455,000 units of public housing will be permitted to convert to Section 8 under RAD. Given the most recent expansion, nearly half of all public housing units could ultimately convert.

While RAD conversions have been popular with PHAs,80 and HUD's initial evaluations of the program have been favorable,81 a recent GAO study has raised questions about HUD's oversight of it, as well as how much private funding is actually being raised for public housing through the conversions.82

Moving to Work Expansion