Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the nation’s largest domestic food assistance program, serving over 42.1 million recipients in an average month at a federal cost of over $68 billion in FY2017. SNAP is jointly administered by state agencies, which handle most recipient functions, and the federal government—specifically, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS)—which supports and oversees the states and handles most retailer functions. In a program with diverse stakeholders, detecting, preventing, and addressing errors and fraud is complex. SNAP has typically been reauthorized in a farm bill approximately every five years; this occurred most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79). Policymakers have long been interested in reducing fraud and improving payment accuracy in the program. Provisions related to these goals have been included in past farm bill reauthorizations and may be considered for the next farm bill, expected in 2018.

There are four main types of inaccuracy and misconduct in SNAP:

Trafficking SNAP benefits is the illicit sale of SNAP benefits, which can involve both retailers and recipients.

Retailer application fraud generally involves an illicit attempt by a store owner to participate in SNAP when the store or owner is not eligible.

Errors and fraud by households applying for SNAP benefits can result in improper payments. Errors are unintentional, while fraud is the intentional violation of program rules.

Errors and fraud by state agencies—agency errors can result in inadvertent improper payments; the discussion of agency fraud largely focuses on certain states’ Quality Control (QC) misconduct.

Certain key ideas are fundamental to any discussion of SNAP errors and fraud:

Errors are not the same as fraud. Fraud is intentional activity that breaks federal and/or state laws, while errors can be the result of unintentional mistakes. Certain acts, such as trafficking SNAP benefits, are always considered fraud; other acts, such as duplicate enrollment, may be the result of either error or fraud depending on the circumstances of the case.

SNAP fraud is relatively rare, according to available data and reports.

There is no single measure that reflects all the forms of fraud in SNAP. There are some frequently cited measures that capture some parts of the issue, and there are relevant data from federal and state agencies’ enforcement efforts.

The most frequently cited measure of fraud is the national retailer trafficking rate, which, estimated that 1.5% of SNAP benefits redeemed from FY2012-FY2014 were trafficked. While the national retailer trafficking rate (which is issued roughly every three years) estimates the extent of retailer trafficking, there is not a standard recipient trafficking rate, nor is there an overall recipient fraud rate.

USDA-FNS is responsible for identifying stores engaged in retailer trafficking—using transaction data analysis, undercover investigations, and other tools—and imposing penalties on store owners who commit violations. Retailers found to have trafficked may be subject to permanent disqualification from participation in SNAP, fines, and other penalties. USDA-FNS also works to identify fraud by retailers applying to accept SNAP benefits. Retailers found to have falsified their applications may be subject to denial, permanent disqualification, and other penalties.

While retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud are primarily pursued by a single federal entity (USDA-FNS), recipient violations (i.e., recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud) are pursued by 53 different state agencies. Recipients found to have trafficked may be required to repay the amount trafficked and may be subject to disqualification from receiving SNAP benefits and other penalties. State agencies’ efforts to reduce and punish recipient fraud vary, which is evident, for instance, in state-submitted data on recipient disqualification activities.

The national payment error rate (NPER) is the most-cited measure of nationwide payment accuracy. Using USDA-FNS’s Quality Control (QC) system, the NPER estimates states’ accuracy in determining eligibility and benefit amounts. The NPER has limitations, though; for instance, it only reflects errors above a threshold amount ($38 in FY2017). After publishing a FY2014 NPER, USDA Office of the Inspector General (OIG ) and USDA-FNS identified data quality issues that prevented the publication of an NPER in FY2015 and FY2016, but USDA-FNS published a NPER for FY2017 in June 2018. For FY2017, it was estimated that 6.30% of SNAP benefit issuance was improper—including a 5.19% overpayment rate and a 1.11% underpayment rate. Regardless of the cause of an overpayment, SNAP agencies are required to work toward recovering excess benefits from households that were overpaid (this is referred to as “establishing a claim against a household”). Applying these rates to benefits issued in FY2017 (over $63.6 billion), an estimated $3.30 billion in benefits were overpaid, and about $710 million in benefits were underpaid.

Overpayments and underpayments to households can be the result of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors during the certification process. State agencies rely on household-provided information in applications, but also employ a range of data matches—some required by federal law, some optional that vary by state—to promote accuracy and double-check information. According to the USDA-FNS FY2016 State Activity Report, of states’ established claims for overpayment, approximately 62% of overpayment claim dollars were for recipient errors, about 28% were for agency errors, and about 11% were due to recipient fraud.

In addition to inadvertent agency errors, state agencies and their agents have been involved in isolated instances of fraud. Beyond cases of fraud conducted by state agency employees for personal gain, in FY2017 the Department of Justice obtained False Claim Act settlements from three state agencies accused of falsifying their Quality Control data and unlawfully obtaining federal bonuses. Investigations into this matter, conducted by the USDA-OIG, are ongoing.

Across all types of fraud, oversight entities such as the Government Accountability Office and USDA-OIG have identified issues and strategies relevant to combating errors and fraud in SNAP. USDA-FNS has also proposed related regulatory changes that were not finalized. On the retailer side, issues identified focus on opportunities to prevent and more promptly punish trafficking. On the recipient side, issues identified include the nonexistence of a recipient fraud rate, states’varied levels of anti-fraud efforts (which may be better incentivized), and improvements to data matching in the application process. During the 115th Congress, Members voted on farm bill proposals that contained some changes to SNAP program integrity policy; these proposals are summarized in CRS Report R45275, The House and Senate 2018 Farm Bills (H.R. 2): A Side-by-Side Comparison with Current Law.

Changes that might strengthen payment accuracy and punishments against fraud can be in tension with other policy objectives such as preserving recipient access to the program, and may have unintended consequences such as incurring costs greater than their savings. Balancing program objectives such as these are considerations for policymakers in this area.

Errors and Fraud in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Types of Errors and Fraud

- Trafficking: Retailer and Recipient

- Retailer Application Fraud

- Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

- Recipient Errors

- Recipient Application Fraud

- Agency Errors

- Fraud Conducted by State Agencies or Their Agents

- State Agency Employee Fraud

- State Agency Fraud

- Extent of Errors and Fraud

- Extent of Retailer Trafficking

- Extent of Retailer Application Fraud

- Extent of Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

- National Payment Error Rate

- Differentiating Between Recipient Fraud, Recipient Errors, and Agency Errors

- Detection and Correction of Errors and Fraud

- Retailer Fraud

- Detection of Retailer Trafficking

- Correction of Retailer Trafficking

- Detection of Retailer Application Fraud

- Correction of Retailer Application Fraud

- Errors in Benefit Issuance to Households

- Detection of Recipient Errors—Data Matching

- Detection of Agency Errors

- Correction of Recipient and Agency Errors—Claims

- Recipient Fraud

- Detection of Recipient Fraud

- Correction of Recipient Fraud

- State Agency Employee Fraud Detection and Correction

- State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control

- Quality Control: Incentives and Penalties Overview

- State Agency Misreporting and Falsification of Quality Control Data

- Combating Errors and Fraud: Issues and Strategies

- Retailer Trafficking

- Certain Store Owners Remain Active in SNAP Despite Permanent Disqualification for Trafficking

- Strengthening Monetary Penalties against Trafficking Retailers

- Changes in EBT Transaction Processing since 2014

- Enhancing Retailer Stocking Standards

- Suspending "Flagrant" Retailer Traffickers

- Increasing Requirements for High-Risk Stores

- Recipient Trafficking

- Requiring Recipient Photographs on EBT Cards

- State Agency Reporting on Recipient Fraud

- Enhancing Federal Financial Incentives for State Agencies to Fight Fraud

- Federal Oversight of State Agencies—Management Evaluations (MEs)

- Delayed State Agency Notification of Retailer Trafficking Cases

- Difference in Burden of Proof for Retailer Trafficking versus Recipient Trafficking

- Best Practices for Fighting Recipient Fraud—the SNAP Fraud Framework

- Retailer Application Fraud

- Verification and Use of Retailer Submitted Social Security Numbers (SSNs)

- Other Verification of Retailer Submitted Information

- Mandating Background Checks on High-Risk Retailer Applications

- Additional Retailer Application Vulnerabilities Identified in 2012 and 2013 USDA-FNS Proposed Rules

- Recipient Application Errors and Fraud

- Establish Federal Incentives to Conduct Pre-certification Investigations

- Difficulties in Collecting Amounts Overpaid to or Trafficked by Recipients

- Duplicate Enrollment and the National Accuracy Clearinghouse (NAC)

- Considerations for Data Matching

- State Agency Errors and Fraud

- Modifying State Involvement in the Quality Control System

Figures

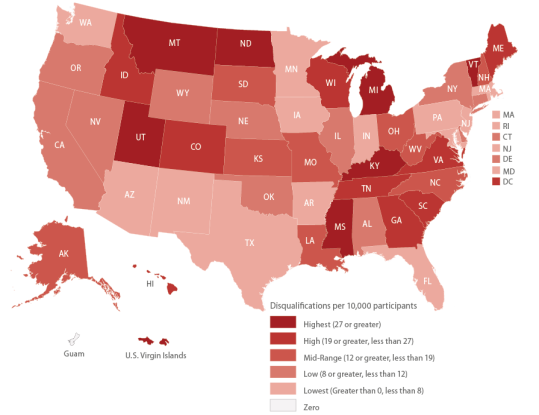

- Figure 1. Authorization and Trafficking at Convenience Stores, 2006-2014

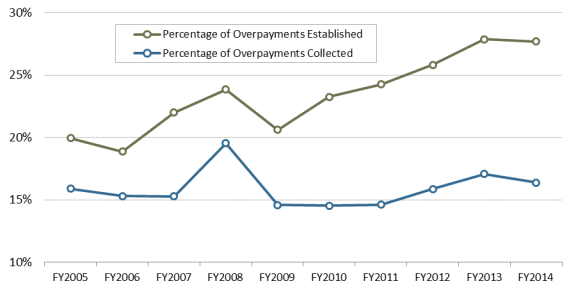

- Figure 2. Claims Establishment by Type, FY2007-FY2016

- Figure 3. Data Matching in SNAP Certification

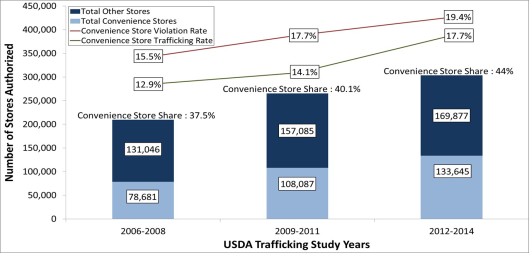

- Figure 4. Per Capita Recipient Disqualifications in States

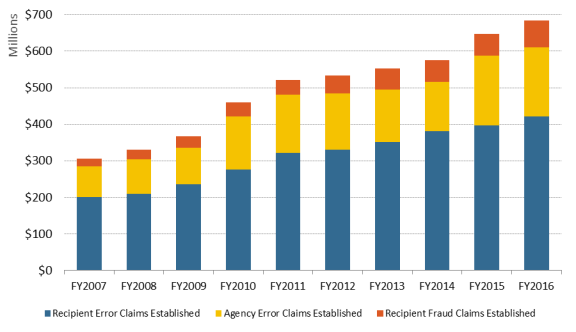

- Figure 5. Claims Established and Claims Collected as Shares of Estimated Dollars Overissued, FY2005-FY2014

Tables

- Table 1. National Payment Error Rate, FY2011-FY2014, FY2017

- Table 2. Bonuses Awarded to States for High Payment Accuracy, FY2014

- Table 3. Penalties Repaid by States for Low Payment Accuracy, FY2005-FY2014

- Table B-1. Inactive USDA-FNS Rulemaking Actions Related to SNAP Integrity

- Table D-1. Convenience Stores as a Percentage of All Stores in SNAP

- Table D-2. Trafficking Rates in Convenience Stores Compared to the National Trafficking Rates

- Table D-3. Convenience Store Redemptions and Trafficking as a Percentage of All Redemptions and Trafficking

- Table E-1. State Payment Error Rates, FY2010 to FY2014

- Table E-2. State Bonuses and Liabilities, FY2010 to FY2014

Summary

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the nation's largest domestic food assistance program, serving over 42.1 million recipients in an average month at a federal cost of over $68 billion in FY2017. SNAP is jointly administered by state agencies, which handle most recipient functions, and the federal government—specifically, the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS)—which supports and oversees the states and handles most retailer functions. In a program with diverse stakeholders, detecting, preventing, and addressing errors and fraud is complex. SNAP has typically been reauthorized in a farm bill approximately every five years; this occurred most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79). Policymakers have long been interested in reducing fraud and improving payment accuracy in the program. Provisions related to these goals have been included in past farm bill reauthorizations and may be considered for the next farm bill, expected in 2018.

There are four main types of inaccuracy and misconduct in SNAP:

- Trafficking SNAP benefits is the illicit sale of SNAP benefits, which can involve both retailers and recipients.

- Retailer application fraud generally involves an illicit attempt by a store owner to participate in SNAP when the store or owner is not eligible.

- Errors and fraud by households applying for SNAP benefits can result in improper payments. Errors are unintentional, while fraud is the intentional violation of program rules.

- Errors and fraud by state agencies—agency errors can result in inadvertent improper payments; the discussion of agency fraud largely focuses on certain states' Quality Control (QC) misconduct.

Certain key ideas are fundamental to any discussion of SNAP errors and fraud:

- Errors are not the same as fraud. Fraud is intentional activity that breaks federal and/or state laws, while errors can be the result of unintentional mistakes. Certain acts, such as trafficking SNAP benefits, are always considered fraud; other acts, such as duplicate enrollment, may be the result of either error or fraud depending on the circumstances of the case.

- SNAP fraud is relatively rare, according to available data and reports.

- There is no single measure that reflects all the forms of fraud in SNAP. There are some frequently cited measures that capture some parts of the issue, and there are relevant data from federal and state agencies' enforcement efforts.

The most frequently cited measure of fraud is the national retailer trafficking rate, which, estimated that 1.5% of SNAP benefits redeemed from FY2012-FY2014 were trafficked. While the national retailer trafficking rate (which is issued roughly every three years) estimates the extent of retailer trafficking, there is not a standard recipient trafficking rate, nor is there an overall recipient fraud rate.

USDA-FNS is responsible for identifying stores engaged in retailer trafficking—using transaction data analysis, undercover investigations, and other tools—and imposing penalties on store owners who commit violations. Retailers found to have trafficked may be subject to permanent disqualification from participation in SNAP, fines, and other penalties. USDA-FNS also works to identify fraud by retailers applying to accept SNAP benefits. Retailers found to have falsified their applications may be subject to denial, permanent disqualification, and other penalties.

While retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud are primarily pursued by a single federal entity (USDA-FNS), recipient violations (i.e., recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud) are pursued by 53 different state agencies. Recipients found to have trafficked may be required to repay the amount trafficked and may be subject to disqualification from receiving SNAP benefits and other penalties. State agencies' efforts to reduce and punish recipient fraud vary, which is evident, for instance, in state-submitted data on recipient disqualification activities.

The national payment error rate (NPER) is the most-cited measure of nationwide payment accuracy. Using USDA-FNS's Quality Control (QC) system, the NPER estimates states' accuracy in determining eligibility and benefit amounts. The NPER has limitations, though; for instance, it only reflects errors above a threshold amount ($38 in FY2017). After publishing a FY2014 NPER, USDA Office of the Inspector General (OIG ) and USDA-FNS identified data quality issues that prevented the publication of an NPER in FY2015 and FY2016, but USDA-FNS published a NPER for FY2017 in June 2018. For FY2017, it was estimated that 6.30% of SNAP benefit issuance was improper—including a 5.19% overpayment rate and a 1.11% underpayment rate. Regardless of the cause of an overpayment, SNAP agencies are required to work toward recovering excess benefits from households that were overpaid (this is referred to as "establishing a claim against a household"). Applying these rates to benefits issued in FY2017 (over $63.6 billion), an estimated $3.30 billion in benefits were overpaid, and about $710 million in benefits were underpaid.

Overpayments and underpayments to households can be the result of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors during the certification process. State agencies rely on household-provided information in applications, but also employ a range of data matches—some required by federal law, some optional that vary by state—to promote accuracy and double-check information. According to the USDA-FNS FY2016 State Activity Report, of states' established claims for overpayment, approximately 62% of overpayment claim dollars were for recipient errors, about 28% were for agency errors, and about 11% were due to recipient fraud.

In addition to inadvertent agency errors, state agencies and their agents have been involved in isolated instances of fraud. Beyond cases of fraud conducted by state agency employees for personal gain, in FY2017 the Department of Justice obtained False Claim Act settlements from three state agencies accused of falsifying their Quality Control data and unlawfully obtaining federal bonuses. Investigations into this matter, conducted by the USDA-OIG, are ongoing.

Across all types of fraud, oversight entities such as the Government Accountability Office and USDA-OIG have identified issues and strategies relevant to combating errors and fraud in SNAP. USDA-FNS has also proposed related regulatory changes that were not finalized. On the retailer side, issues identified focus on opportunities to prevent and more promptly punish trafficking. On the recipient side, issues identified include the nonexistence of a recipient fraud rate, states'varied levels of anti-fraud efforts (which may be better incentivized), and improvements to data matching in the application process. During the 115th Congress, Members voted on farm bill proposals that contained some changes to SNAP program integrity policy; these proposals are summarized in CRS Report R45275, The House and Senate 2018 Farm Bills (H.R. 2): A Side-by-Side Comparison with Current Law.

Changes that might strengthen payment accuracy and punishments against fraud can be in tension with other policy objectives such as preserving recipient access to the program, and may have unintended consequences such as incurring costs greater than their savings. Balancing program objectives such as these are considerations for policymakers in this area.

Introduction

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the nation's largest domestic food assistance program, serving about 42.2 million recipients in an average month at a federal cost of over $68 billion in FY2017.1 It is jointly administered by the federal government and the states and provides means-tested benefits to recipients who are deemed eligible. These benefits may be used only for eligible foods at any of the approximately 260,000 authorized retailers, which range from independent corner stores to national chain supermarkets.2 In a program that operates with so many different stakeholders, detecting, preventing, and addressing errors and fraud is a complex undertaking. Among the complexities are the monitoring of retailer acceptance and recipient use of benefits, the accuracy of information provided by applicant households, and states' performance administering the program. Many governmental entities—federal and state agencies, including both human services and law enforcement—play a role in efforts to detect, prevent, and punish fraudulent SNAP activities and to reduce inadvertent errors.

SNAP has typically been reauthorized in a farm bill approximately every five years; this occurred most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79).3 Policymakers have long been interested in reducing fraud and improving accuracy in the program, and provisions related to these goals are frequently included in farm bills. In preparation for the next farm bill, up for reauthorization in September 2018, policymakers have again begun to discuss error and fraud in the program.4 The Trump Administration has also announced related policy changes.5 At the same time, some policymakers defend the program against criticism of its integrity.6

To help policymakers navigate this complex set of policy issues, this report seeks to define terms related to errors and fraud; identify problems and describe what is known of their extent; summarize current policy and practice; and share recommendations, proposals, and pilots that have come up in recent years. The report answers several questions around four main types of inaccuracy and misconduct: (1) trafficking SNAP benefits (by retailers and by recipients); (2) retailer application fraud; (3) errors and fraud in SNAP household applications; and (4) errors and fraud committed by state agencies (including a discussion of states' recent Quality Control (QC) misconduct). The report then discusses challenges to combating errors and fraud—across the four areas—and potential strategies for addressing those challenges.

Certain key ideas that are fundamental to discussion of SNAP errors and fraud are explored further in the report:

- Errors are not the same as fraud. Fraud is intentional activity that breaks federal and/or state laws, but there are also ways that program stakeholders—particularly recipients and states—may inadvertently err, which could affect benefit amounts. Certain acts, such as trafficking, are always considered fraud, but other acts, such as duplicate enrollment, may be the result of either error or fraud depending on the circumstances of the case.

- SNAP fraud is relatively rare, according to available data and reports. While this report discusses illegal or inaccurate activities in SNAP, they represent a relatively small fraction of SNAP activity overall.

- There is no single data point that reflects all the forms of fraud in SNAP. The most frequently cited measure of fraud is a national estimate of retailer trafficking, which is a significant, but not the only, type of fraud in the program.

- While retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud are pursued primarily by a single federal entity, recipient violations are pursued by 53 different state agencies. This leads to disparate approaches and disparate reporting.7

- The national payment error rate (NPER) is the most-often cited measure of nationwide SNAP payment accuracy, but it has limitations. For example, it only reflects errors above an error tolerance threshold.

Policies to reduce fraud and increase accuracy can be in tension with other policy objectives, and may have unintended consequences. Policies that make retailer authorization more onerous, for instance, have the potential to decrease participants' access to SNAP-authorized stores. Making eligibility determinations more complex for recipients can impede recipients' access to the program and could strain states' eligibility determination operations. Implementing better data collection and accountability systems could require more staff and could incur more costs than it reduces.

This report provides a foundation for discussing error and fraud in SNAP and for evaluating policy proposals. It does not make independent CRS findings, but rather synthesizes the many available resources on error and fraud in SNAP. It relies, in particular, on reports and data from the United States Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) as well as the published audits of the USDA's Office of the Inspector General (USDA-OIG) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO). For a list of abbreviations used in this report, see Appendix A.

Types of Errors and Fraud

This section defines each of the types of intentional fraud and unintentional errors committed by recipients, retailers, and state agencies, including retailer trafficking (fraud), recipient trafficking (fraud), retailer application fraud, recipient application fraud, recipient errors, agency errors, state agency employee fraud, and state agency fraud.

Trafficking: Retailer and Recipient

USDA-FNS is responsible for administering the retailer side of SNAP and for pursuing retailer fraud; while states are responsible for administering the recipient side of SNAP (with federal oversight) and for pursuing recipient fraud.8 "Trafficking" usually means the direct exchange of SNAP benefits (formerly known as food stamps) for cash, which is illegal, and both retailers and recipients can engage in this form of fraud.9 Although SNAP benefits have a dollar value, they are not the same as cash because they can only be spent on eligible food for household consumption at authorized stores equipped with Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) point of sale (POS) machines.10 Trafficking can also include the exchange of SNAP benefits for controlled substances, firearms, ammunition, or explosives.11 Additionally, trafficking includes indirect exchanges, such as obtaining cash refunds for products purchased with SNAP benefits or reselling products purchased with SNAP benefits. Trafficking SNAP benefits includes recipient trafficking and retailer trafficking. Retailer trafficking of SNAP benefits usually occurs when a SNAP recipient sells their benefits for cash, often at a loss, to an owner or employee of a store participating in SNAP.12 Recipient trafficking usually coincides with retailer trafficking, but it may take other forms (e.g., if a recipient were to sell their benefits, or food purchased with benefits, to another individual). Trafficking is one of the most serious forms of SNAP fraud, and although it does not increase costs to the federal government (as overpayments do), it does divert federal funds from their intended purpose.

Retailer Application Fraud

Retailers misrepresenting themselves or circumventing disqualification in the application process can be a source of fraud. To obtain SNAP authorization, applicant retailers must meet certain requirements, including stocking13 and business integrity standards.14 When a retailer initially applies to receive authorization to participate in SNAP or applies for reauthorization to continue SNAP participation,15 the store owner must submit personal and business information and documentation to USDA-FNS in order to verify eligibility for SNAP participation. If a retailer deliberately submits false or misleading information of a substantive nature in order to receive SNAP authorization despite their ineligibility, then they have committed falsification—retailer application fraud.16 Another kind of retailer application fraud involves a store owner attempting to circumvent disqualification from SNAP by engaging in a purported sale or transfer of ownership of their store to a spouse or relative; after which the new purported owner applies to participate in SNAP, claiming that the former disqualified owners are no longer associated with the store. This practice is often referred to as "straw ownership," and USDA-FNS does not consider such sales or transfers of ownership to be bona fide.17 Such actions by the disqualified retailer are considered circumvention—retailer application fraud.18 Retailer application fraud does not increase costs to the federal government (as overpayments can), but it does enable retailers who may be more likely to engage in trafficking to enter the program.

Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

In addition to retailer trafficking and retailer application fraud, errors and fraud can arise in determining eligibility and benefit amounts for recipients.

Recipient Errors

When a household initially applies to receive or recertifies to continue receiving SNAP benefits, the applicant household must submit personal information and documentation to their state agency for eligibility determination, and for benefit calculation if found to be eligible. During this application process, an applicant may misunderstand SNAP rules, make a miscalculation, otherwise unintentionally provide incorrect information, or accidentally omit certain information. If this error results in an overpayment to the household and there is no proof that this error was intentional, then this error is designated as an inadvertent household error (IHE).19

Recipient Application Fraud

If an applicant is found to have intentionally submitted false or misleading information during the initial application or recertification process that leads to an incorrect eligibility or allotment determination (resulting in an overpayment), then that applicant has committed an intentional program violation (IPV)—recipient application fraud.20

Agency Errors

SNAP overpayments or underpayments that are not the result of recipient actions (i.e., not the result of recipient errors or recipient fraud) are generally the result of agency errors (AEs).21 Agency errors include overpayments or underpayments caused by the action of, or failure to take action by, any representative of a state agency.

Fraud Conducted by State Agencies or Their Agents

"State agency employee fraud" and "state agency fraud" are not terms defined in statute, regulation, or agency guidance. As used in this report, "state agency employee fraud" and "state agency fraud" include forms of fraud often referred to as "insider threats"—a threat to SNAP integrity that comes from within entities that administer SNAP (i.e., state agencies).

State Agency Employee Fraud

State agency employee fraud is any intentional effort by state employees to illegally generate and benefit from SNAP overpayments. State agency employee fraud usually involves eligibility workers who abuse their positions and access to the SNAP certification process in order to unlawfully generate SNAP accounts that materially benefit individuals not entitled to such benefits.

State Agency Fraud

State agency fraud is any intentional effort by state officials to mislead USDA-FNS or other federal authorities in order to illegally obtain federal funds or avoid federal monetary penalties. State agency fraud cases are very infrequent and generally center on a state's falsification of program-related data. Of interest to policymakers, the state agency fraud case examined in this report, first identified in 2017, deals with multiple states' falsification of Quality Control (QC) data in order to obtain monetary bonuses and avoid monetary penalties, with some actions dating back to 2008.22 (For more information, see "State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control.")

Extent of Errors and Fraud

Extent of Retailer Trafficking

USDA-FNS publishes an annual report that summarizes their annual administrative activities pertaining to retailers participating in SNAP,23 including detailed retailer data on participation and redemptions, retailer applications and authorizations, investigations and sanctions, and administrative review. According to this Retailer Management Report, in FY2016 there were 260,115 retailers participating in SNAP, and USDA-FNS permanently disqualified 1,842 stores for retailer trafficking (less than 1% of all stores).24

|

National Retailer Trafficking Rate25 The most recent trafficking study (analyzing 2012-2014 data) estimated that 1.50% of all SNAP benefits redeemed were trafficked (sold for cash or exchanged illegally) at stores. This is up from an estimated 1.34% in the 2009-2011 study. This only reflects one type of fraud—retailer trafficking. |

Roughly every three years, USDA-FNS publishes a study estimating the extent of retailer trafficking in SNAP over about three years of SNAP redemption data. The retailer trafficking studies referenced in this report were issued in 2017 (covering 2012-2014), 2013 (covering 2009-2011), and 2011 (covering 2006-2008).26 By examining a representative sample, these studies determined two national rates that reflect the prevalence of retailer trafficking. The national retailer trafficking rate represents the proportion of SNAP redemptions at stores that were estimated to have been trafficked. The national store violation rate represents the proportion of authorized stores that were estimated to have engaged in trafficking.

The national retailer trafficking rate is the most-cited measure of fraud in SNAP, although it does not capture all types of fraud (i.e., it represents only retailer trafficking). According to the September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, the national retailer trafficking rate for 2012-2014 was 1.50%, up from 1.34% in the 2009-2011 study.27 This means that, during this period, USDA-FNS estimates that 1.50% of all SNAP benefits redeemed were trafficked at participating stores. This constitutes about $1.1 billion in estimated benefits trafficked each year at stores during this period.28 Additionally, this study estimated that the national store violation rate for this period was 11.82%, up from 10.47% in the 2009-2011 study.29 This means that, during this period, USDA-FNS estimates that 11.82% of all SNAP-authorized retailers engaged in retailer trafficking at least once.

The September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study found that the increase in retailer trafficking was due to increased program participation by smaller stores, which have a higher rate of retailer trafficking. While stores enter and leave the program from year to year, the overall growth in SNAP-authorized stores over the last 10 years (FY2007-FY2016) was about 93,000, and about 63% of this growth came from convenience stores in the program (see Table D-1 in Appendix D).30 As of FY2016, convenience stores constitute about 46% of all stores in the program, up from 36% in FY2007.31 According to the September 2017 USDA-FNS Retailer Trafficking Study, covering 2012-2014, convenience stores account for about 5% of total SNAP redemptions, but about 57% of retailer trafficking (see Table D-3 in Appendix D).32 Also according to this study, about 18% of all SNAP benefits used at authorized convenience stores are trafficked by these stores (i.e., the convenience store trafficking rate), and about 19% of all authorized convenience stores are engaged in trafficking (i.e., the convenience store violation rate).33 These rates are significantly higher than the national rates for all stores (see Table D-2 in Appendix D). The increase in SNAP participation by smaller stores appears to correlate to an overall increase in retailer trafficking, according to USDA-FNS.34 Figure 1 displays some of these data from the three most recent trafficking studies.

|

Figure 1. Authorization and Trafficking at Convenience Stores, 2006-2014 |

|

|

Source: The three USDA-FNS retailer trafficking studies referenced can be found online using https://www.fns.usda.gov/report-finder. |

Extent of Retailer Application Fraud

There is no standard measure of retailer application fraud. However, USDA-FNS does report annually on actions taken against business integrity violations, and a retailer engaged in application fraud (including falsification and circumvention) is generally considered to be in violation of business integrity standards.

In FY2016, USDA-FNS sanctioned 126 stores for business integrity violations. This number includes sanctions not related to retailer application fraud and amounts to less than 1 store sanctioned for every 2,064 stores participating in the program.35 During the same period, USDA-FNS permanently disqualified about 15 times as many stores for retailer trafficking.36

Extent of Errors and Fraud in Benefit Issuance to Households

National Payment Error Rate

The SNAP Quality Control (QC) system measures improper payments in SNAP. This system was first established by the Food Stamp Act of 1977.37 Under the QC system, every state agency conducts a monthly review of a sample of its households, comparing the amounts of overpayments and underpayments to total issuance.38 From this review, state agencies calculate their state payment error rate (SPER). USDA-FNS conducts annual reviews of a sample of each state's reviews to validate state findings and determine national rates—developing the national payment error rate (NPER).

The NPER is the most-often cited measure of payment accuracy in SNAP.39 Unlike the national retailer trafficking rate, the NPER is not a measure of fraud. The NPER reflects improper payments, but not the cause of these overpayments and underpayments. The NPER estimates all overpayments and underpayments resulting from recipient errors, recipient application fraud, and agency error.40 Per current federal law, only overpayments and underpayments of $38 or more (inflation-adjusted annually) in the sample month are counted when calculating the payment error rate—this is called the Quality Control threshold.41 Additionally, the NPER combines both the overpayment rate and the underpayment rate, so it does not reflect only excess expenditures. For example, in FY2017, the NPER was 6.30%—which included a 5.19% overpayment rate and a 1.11% underpayment rate.42

In discussions regarding SNAP payment accuracy, the NPER is sometimes misunderstood to be a measure of the federal dollars lost to fraud and waste in the program. The NPER instead reflects the extent of inaccurate payments that exceed the Quality Control threshold in a given year. Regardless of the cause of an overpayment, SNAP agencies are required to work towards recovering excess benefits from households that were overpaid. Recovery of overpayments involves, first, the establishment (or determination) of a claim against a household, and, second, the actual collection of that claim. Applying the FY2017 NPER to total benefit issuance, in FY2017 an estimated $3.3 billion in benefits were overpaid, an estimated $710 million in benefits were underpaid.43 In FY2016, the most recent year available, states established over $684 million in claims to recover overpayments.44

Context for Comparing FY2017 NPER to Prior Years

Recent years' NPERs are listed in Table 1, showing rates from FY2011-FY2014 and then skipping to FY2017. SNAP national payment error rates were not released by USDA-FNS in FY2015 or FY2016, due to data quality concerns.

In 2014, USDA found data quality issues in 42 of 53 state agencies' Quality Control data reporting. These data quality issues are not, in and of themselves, proof of wrongdoing. In some cases, states had not followed protocol, while in other cases states had been found to have deliberately covered up errors (fraudulent actions). (A more detailed discussion of Quality Control as well as these audits and investigations can be found in "State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control"). USDA-FNS suspended error reporting for FY2015 and FY2016, and also used this time to examine and improve state quality control procedures.45

In June 2018, USDA-FNS published FY2017 state and national error rates (NPER). USDA-FNS's accompanying materials describe that this NPER was determined "under new controls to prevent any recurrence of statistical bias in the QC system," which includes "a new management evaluation process to examine state quality control procedures on a regular basis."46 The agency also described that the FY2017 rate stems from "a modernized review process, which includes updated guidance, revisions to [the relevant FNS handbook], extensive training for State and Federal staff, and modifications to State procedures to ensure consistency with Federal guidelines."47

As displayed (Table 1) and discussed earlier, the FY2017 NPER of 6.30% is a substantial increase from the FY2014 of 3.66%. USDA-FNS states the FY2017 rate "is higher than the previous rate ... but it is more accurate."48 However, changes to data collection and related oversight since FY2014 make it difficult to reliably compare FY2017 rates to earlier years, as it is possible that earlier years include systemic under-reporting.

|

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2017a |

|

|

Overpayment |

2.99% |

2.77% |

2.61% |

2.96% |

5.19% |

|

Underpayment |

0.81% |

0.65% |

0.60% |

0.69% |

1.11% |

|

NPER |

3.80% |

3.42% |

3.20% |

3.66% |

6.30% |

Differentiating Between Recipient Fraud, Recipient Errors, and Agency Errors

The SNAP overpayment rate (component of the national payment error rate) estimates the extent of all SNAP overpayments, including overpayments resulting from recipient errors, recipient fraud, and agency errors (estimated to total about $3.3 billion overpaid in FY2017). The NPER does not, however, differentiate between the relative extents of each of these types of errors and fraud (i.e., the NPER cannot tell us what percentage of this $3.3 billion is due to, for example, agency errors). There is currently no single standard measurement that individually quantifies the extent of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors. State agencies are, however, responsible for administering the recipient side of SNAP, and every year states report data on these activities which USDA-FNS publishes in the SNAP State Activity Report (SAR).49 This report includes detailed data on state-level program operations including benefit issuance, participation, administrative (i.e., non-benefits) costs, recipient disqualification, and claims.

When a recipient error, an act of recipient fraud, or an agency error results in an overpayment to a household (and that overpayment is detected by the state agency), the household is generally required by the state agency to repay the overpaid amount (i.e., a claim is established). Data on the establishment of claims resulting from recipient errors, recipient fraud, and agency errors is provided in the state report (subdivided by type). The extent of claims establishment, therefore, can serve as a proxy for the extent of these types of errors and fraud. In addition, when a recipient commits fraud (and that act of fraud is detected and proven by the state agency), that recipient is generally punished with disqualification from SNAP. The extent of recipient disqualifications, therefore, can serve as a proxy for the extent of recipient fraud.

Before examining these claims and disqualification data, however, it is important to understand the limitations of this approach. Claims are not established in all instances of overpayments resulting from recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors. For example, claims may not be established when overpayment amounts fall below state agencies' claims thresholds50 or when overpayments are not detected by state agencies. Likewise, not all acts of recipient fraud are detected, proven, and punished with disqualification. Also, these claims establishment and disqualifications data are not based on representative samples and, therefore, these data may not fully reflect the prevalence of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors in the SNAP caseload. Despite these shortcomings, these claims and disqualification data are the only available measures which reflect, albeit imperfectly, the extent of recipient errors, recipient fraud, or agency errors in SNAP. The following calculations of the extent of these types of errors and fraud are based on SNAP State Activity Report FY2016 data including the following: total issuance of $66,539,351,219; average monthly participation of 21,777,938 households; an average monthly participation of 44,219,363 persons; total claims established of 884,301; and total claims dollars established of $684,197,891.51

Recipient Fraud

Unlike retailer trafficking, which is handled by one federal entity (USDA-FNS), recipient fraud is detected and punished by 53 different SNAP agencies (50 states, DC, Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and, as noted in the September 2012 USDA-OIG report, "FNS cannot estimate a recipient fraud rate because it has not established how States should compile, track, and report fraud in a uniform manner."52 This lack of standardization is a reason why a national recipient fraud rate does not exist.53 Both recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud are included in these figures.

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

- for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 14 contained a recipient who was investigated and determined to have committed fraud that resulted in an overpayment that the state agency required the household to repay (30,274 claims established);

- for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about $11 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to recipient fraud and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($73,403,758 in fraud claims established);

- about 3% of the total number of claims established were established due to recipient fraud;

- about 11% of the total claims dollars established were established due to recipient fraud;

- for every 10,000 recipients participating in SNAP, about 13 were disqualified from the program for violating SNAP rules (e.g., committing fraud; 55,930 disqualified);

- about 1.5% of disqualification entries made into the USDA-FNS electronic Disqualified Recipient System (eDRS)54 in FY2016 were permanent disqualifications;55 and

- for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about $21 were determined by state agencies to have been lost (overpaid due to recipient application fraud or trafficked) to recipient fraud associated with disqualified recipients ($136,475,242 in program loss associated with disqualified recipients).56

Recipient Errors

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

- for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 181 were overpaid due to a recipient error and the state agency required the household to repay the overpaid amount (394,883 recipient error claims established);

- for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about $63 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to recipient errors and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($421,934,288 in recipient error claims established);

- about 45% of the total number of claims established were established due to recipient errors;

- about 62% of the total claims dollars established were established due to recipient errors;

- about 65% of FY2016 claims were established by four states;57

- about 55% of FY2016 claims amounts were established by these four states; and

- these four states accounted for about 30% of SNAP participants.

Agency Errors

According to the FY2016 SNAP State Activity Report

- for every 10,000 households participating in SNAP, about 47 were overpaid due to agency errors, and the state agency required the household to repay the overpaid amount (459,144 agency error claims established);

- for every $10,000 in benefits issued to households participating in SNAP, about $28 were determined by state agencies to have been overpaid due to agency errors and were required to be repaid by the overpaid household ($188,859,846 in agency error claims established);

- about 52% of the total number of claims established were established due to agency errors;

- about 28% of the total claims dollars established were established due to agency errors;

- about 80% of the total number of agency error claims established were established by California;58

- about 64% of the total agency error claims dollars established were established by California; and

- California accounted for about 10% of SNAP participants.

Although the total volume of claims established has increased over time, the majority of claims established have been the result of recipient errors, with agency errors being second most common, and recipient fraud claims being least common—as illustrated by Figure 2.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using data from SNAP State Activity Reports FY2007-FY2016. |

Detection and Correction of Errors and Fraud

State and federal efforts to detect and correct errors, as well as efforts to detect and deter fraud, are detailed in this section.

Retailer Fraud

USDA-FNS is responsible for administering the retailer side of SNAP and for pursuing retailer fraud.59 USDA-OIG, in collaboration with the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), U.S. Secret Service, and other federal, state, and local law enforcement entities, is responsible for pursuing criminal charges against retailers found to be engaging in retailer trafficking.

Detection of Retailer Trafficking

Retailer trafficking can be detected through a variety of means, including the following:

Analysis of EBT Transaction Data—Whenever a SNAP EBT card is swiped, the transaction data is captured and analyzed by USDA-FNS for suspicious patterns. USDA-FNS use these data to develop a case against a retailer when the transactions indicate retailer trafficking is occurring at their store. In FY2016, USDA-FNS reviewed the transactions of nearly 9% of participating stores.60 Over 80% of retailer trafficking detected by USDA-FNS are found primarily through EBT transaction analysis.61

Undercover Investigations—USDA-FNS performs undercover investigation of stores suspected of violating SNAP rules (e.g., trafficking), and in FY2016, USDA-FNS investigated over 1% of participating stores.62

State Law Enforcement Bureau (SLEB) Agreements—Some state agencies enter into state law enforcement bureau (SLEB) agreements with law enforcement entities in their jurisdictions in order to further their efforts to detect trafficking. These agreements are typically focused on recipient trafficking, but they can have implications for retailer trafficking.

Tips and Referrals—USDA-FNS receives tips, complaints, and referrals, which can lead to cases of retailer trafficking. These referrals come from SNAP retailers, SNAP recipients, members of the public, state agencies, SLEBs, USDA-OIG, or other law enforcement entities. USDA-OIG operates a website and hotline for members of the public to report instances of fraud.63 In FY2016, USDA-OIG referred 4,320 complaints to USDA-FNS.64

Correction of Retailer Trafficking

If a store is found to have committed trafficking, then all of the owners of the store may be subject to penalties.65 Major penalties associated with retailer trafficking include the following:

Disqualification—If USDA-FNS finds that a SNAP-authorized retailer violated any SNAP rules, then that retailer may be subject to a period of disqualification from program participation.66 Trafficking SNAP benefits is considered one of the most severe violations of SNAP rules, and a retailer found by USDA-FNS to have trafficked SNAP benefits (regardless of the amount) is generally subject to a permanent disqualification (PDQ) from program participation.67

Reciprocal WIC Disqualification—Stores that are disqualified for violations of the rules of SNAP are disqualified for an equal (but not necessarily concurrent) period of time from participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).68 Likewise, stores disqualified from WIC are disqualified from SNAP for an equal (but not necessarily concurrent) period of time. PDQs, such as PDQs for trafficking, are also reciprocal between the programs.

|

Rights of Retailers Accused of Fraud Following a completed trafficking investigation, the agency sends a retailer a "charge letter" detailing the charges, and explaining the retailer's right to request administrative review. If requested, an independent subdivision of USDA-FNS considers the validity of the charges anew and issues a Final Agency Determination that sustains, reverses, or modifies the charges and explains the retailer's right to request judicial review. The retailer may choose to file a complaint against USDA-FNS in the court of jurisdiction after receiving a Final Agency Determination. |

Restitution of Benefits Trafficked (Claims)—When a retailer accepts or redeems SNAP benefits in violation of the Food and Nutrition Act of 2008 (FNA), such as engaging in retailer trafficking of SNAP benefits, that retailer may be compelled to repay the amount that they illegally redeemed. This is called a claim and is considered a federal debt. USDA-FNS has the authority to collect such claims by offsetting against a store's SNAP redemptions as well as a store's bond or letter of credit (LOC),69 where applicable.70

Public Disclosure of Disqualified Retailers—USDA-FNS has the authority to publicly disclose the store and owner name for disqualified retailers.71 A December 2016 USDA-FNS Final Rule asserted USDA-FNS's intent to disclose this information in order to deter retailer trafficking.72

Transfer of Ownership Civil Money Penalty (TOCMP)—If a retailer under a period of disqualification sells or transfers ownership of their store, then USDA-FNS is to assess that disqualified retailer a "transfer of ownership civil money penalty" (TOCMP).73 This means that retailers permanently disqualified from SNAP for committing retailer trafficking are to be assessed this penalty whenever they sell or transfer ownership of their stores (regardless of how much time has passed since the disqualification occurred). In FY2016, USDA-FNS assessed 257 such penalties with a mean value of $29,284.74

Exclusion from the General Service Administration's System for Award Management (GSA-SAM)—This GSA system tracks individuals and entities that do business with the federal government. An individual or entity excluded from this system is prohibited from doing business with the federal government for the duration of the exclusion.75 All of the owners of a store permanently disqualified from SNAP participation for trafficking benefits are permanently listed as exclusions in GSA-SAM. As of September 2017, 10,307 permanently disqualified retailers have been listed by USDA-FNS in GSA-SAM as exclusions due to SNAP and WIC violations.76 This type of exclusion can have collateral consequences for the excluded party.77

Criminal Charges and Penalties—Retailers engaged in trafficking may be criminally charged and penalized with fines up to $250,000 and imprisonment up to 20 years.78 In addition, other adverse monetary penalties (e.g., asset forfeitures, recoveries, collections, and restitutions) may be assessed against those convicted. USDA-OIG, in collaboration with federal, state, and local law enforcement entities, pursues charges against retailers who traffic SNAP benefits. USDA-OIG usually criminally pursues only retailers who traffic in high dollar amounts of benefits and/or retailers who also engaged in other criminal activity. In some cases, state law enforcement bureaus may pursue criminal charges against individuals engaged in retailer trafficking under state or local statutes. In FY2016, USDA-OIG opened 208 SNAP fraud investigations, and obtained 600 indictments, 510 convictions, and $95.3 million in monetary penalties.79

Detection of Retailer Application Fraud

USDA-FNS reviews all information and materials submitted by applicant retailers in order to identify suspicious items and documentation that may indicate retailer application fraud. Where such suspicions arise, USDA-FNS may require additional supporting documentation from the applicant retailer and may contact other federal, state, or local government entities (e.g., entities that administer business licensure, taxation, or trade) to verify questionable items.80

Correction of Retailer Application Fraud

Denial of Application—If USDA-FNS finds during the application process that a retailer fails to meet requirements such as stocking and business integrity standards, then the retailer's application is to be denied. If USDA-FNS determines that an applicant retailer has falsified the application, then that retailer's application is to be denied—the period of denial ranges from three years to permanent depending on the severity and nature of the falsification.81 A retailer denied authorization to participate in SNAP is not generally subject to any penalties other than denial.82

Permanent or Term Disqualification—Retailers who knowingly engage in falsification of substantive matters (e.g., falsification of ownership or eligibility information) may be subject to a permanent disqualification from program participation. Retailers who engage in falsification of a lesser nature (e.g., falsification of store information such as store name or address) are generally subject to a term disqualification of three years. Retailers that are permanently disqualified for falsification may be subject to all of the penalties associated with permanent disqualification (as discussed previously in the context of retailer trafficking penalties), including reciprocal WIC disqualification, claims, public disclosure, TOCMP, GSA-SAM exclusion, and criminal charges and penalties where appropriate.83

Errors in Benefit Issuance to Households

SNAP certification is the process of evaluating an application, determining if an applicant is eligible to receive SNAP benefits, and the appropriate size of the benefit allotment if the applicant is found to be eligible. This is one of the primary responsibilities of state agencies (with federal oversight). Errors (i.e., recipient errors and agency errors) that occur during this process can result in underissuance or overissuance of SNAP benefits.

Detection of Recipient Errors—Data Matching

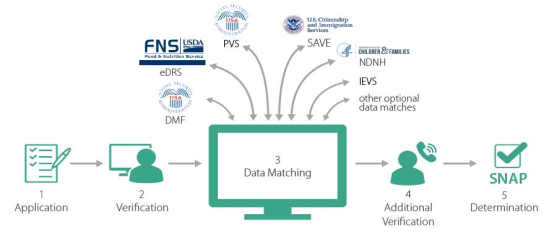

The primary sources for information needed to make certification determinations are generally the applicants themselves, but the eligibility worker may also utilize collateral contact with other entities when necessary.84 In addition, an eligibility worker may perform additional checks using federal, state, local, or private data systems in order to verify information provided by applicants.85 A visual overview of data matching in the certification process is presented in Figure 3.

|

|

Source: Prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Notes: Certification, as illustrated in this graphic, includes five main steps: (1) a household initially applies to receive or recertifies to continue receiving SNAP benefits; (2) a SNAP eligibility worker evaluates the household's application for completion and verifies submitted information (including through interviews with the applicant); (3) a range of data matching systems (both mandatory and optional) is used to confirm eligibility and income information reported by the applicant; (4) when needed, the SNAP staff follows up to verify data; and (5) SNAP staff ultimately makes a SNAP eligibility determination and, if appropriate, designates the benefit allotment amount. |

In FY2016, about 62% of overpayment dollars identified through the claims establishment process (i.e., after overpayments have already occurred) were due to inadvertent household errors made by recipients when applying for benefits.86 With a caseload of about 22 million households, recipient errors (sometimes stemming from simple misunderstanding of federal SNAP regulations) can add up quickly and create a serious payment accuracy problem for states. Although the upfront cost and effort required of a state agency to implement a data match as part of the SNAP certification process can be considerable, data matches using federal, state, local, or private systems can allow agencies to quickly identify recipient errors that could affect applicants' eligibility or benefit amount. Over the years, policymakers have been interested in data matching systems to reduce overpayments.

Mandatory Data Matches

The following six data matches have been statutorily mandated as part of the SNAP certification process:

U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, National Directory of New Hires (HHS-ACF-NDNH) New Hire File—This system is used to verify household employment information.87 The 2014 Farm Bill mandated state use of the New Hire File and this requirement was implemented in a January 2016 USDA-FNS Interim Final Rule.88

Social Security Administration, Prisoner Verification System (SSA-PVS)—This system is used to verify if household members are incarcerated.89 The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 mandated that all SNAP agencies match against the SSA's Prisoner Verification System.90

Social Security Administration, Death Master File (SSA-DMF)—This system is used to verify if household members are deceased.91 In 1998, P.L. 105-379 mandated that all SNAP agencies match against the SSA-DMF.92

USDA-FNS Electronic Disqualified Recipient System (USDA-FNS-eDRS)—This system is used to verify if household members are disqualified from SNAP.93

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (DHS-USCIS-SAVE)—This system is used to verify household members immigration status.94 The 2014 Farm Bill mandated that SNAP agencies utilize an immigration status verification system95 as a part of the certification process;96 a December 2016 USDA-FNS notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) regarding the requirement to utilize this data match was published, but the rule has not yet been finalized.97

Income and Eligibility Verification System (IEVS)—SNAP agencies are required to verify the income and eligibility of all applicants during the SNAP certification process. They generally fulfill this requirement through the use of an income and eligibility verification system (IEVS). An IEVS is not a single data match, but rather a state system that may use multiple federal, state, and local data sources to confirm the accuracy of eligibility and income information provided by the applicant and to locate pertinent information that may have been omitted by the applicant.98 The specific data matches used in an IEVS, however, will vary from state to state.99 The 2014 Farm Bill made states' use of IEVS mandatory in accordance with standards set by the Secretary of Agriculture. This policy is pending implementation, as USDA-FNS published an NPRM in December 2016, but a final rule has not yet been published.100

Optional Data Matches

States also use optional data matches and incorporate these into their processes. Several key eligibility data examples, such as income and program disqualifications, are discussed below:101

Income matches—A household's income and related SNAP deductions are basic determinants of eligibility and an applicant's benefit allotment. As a result, in addition to the mandatory matches discussed above, most states utilize several optional federal and state data matches to verify earned and unearned income. For examples of optional income matches, see Appendix C.

SNAP disqualification matches—In addition to the mandatory USDA-FNS-eDRS match, states maintain their own internal databases of recipients disqualified within the state, and a match from such state databases indicates that a member of an applicant household is ineligible.102

Other data matches—In addition, state agencies use data sources to assess a number of other aspects of a household's application or recertification. For instance, state criminal justice or correctional agency system matches and state department of health vital information system or burial assistance program matches can ensure that a household does not include incarcerated or deceased members. Likewise, state department of children's services or foster care matches can ensure that a household does not include children that have been removed. Such state matches to verify that household size is correct are generally considered verified upon receipt. Matches against state and federal crime databases can ensure that individuals subject to crime-related restrictions are correctly excluded in eligibility determination.103 Data matches between SNAP and other public benefit programs can also help a state agency ensure that states are accurately implementing their comparable disqualification policies.104 These data matches are discussed in more detail in the October 2016 GAO report.105

Detection of Agency Errors

State agencies are responsible for preventing, detecting, and correcting agency errors.106 Agency errors are generally the product of human error, so training and supervision of eligibility workers is the primary means of mitigating them (e.g., something as simple as an eligibility worker transposing two digits during data entry). Agency errors can be detected by ongoing, independent process improvements (e.g., quality control or quality assurance), supervisory case review, eligibility workers, and recipients. Agency errors may also result from state system technical glitches, so states may detect these errors through system audits and mitigate them through system improvements.

Correction of Recipient and Agency Errors—Claims

If a household receives an overpayment, and that overpayment is detected by the state agency, then the agency generally establishes a claim against the household, requiring the adult members of the household to repay the amount that was overpaid. Claims are considered federal debt and must be repaid by the adult members of overpaid households regardless of the cause of the overpayment (i.e., recipient error, recipient fraud, or agency error) except in the case of a major systems failure.107 Agencies must also correct underpayments that they identify. State agencies may elect not to establish claims on low dollar overpayments when such overpayments fall below the agency's claims threshold, explained below.

|

Claims Threshold The "claims threshold" is the minimum dollar value of overpayments that must be collected by state agencies. Agencies may establish claims on amounts below this threshold.108 This threshold applies to overpayments regardless of cause (i.e., recipient error, recipient fraud, or agency error). Since 1983, this threshold was set at $35, but in 2000 it was raised to $125.109 This threshold does not apply to any overpayments discovered during the Quality Control (QC) process, and claims must be established on all such amounts (regardless of dollar value). Generally, this threshold does not apply to households currently participating in the program, as it is easier to collect claims from actively participating households using allotment reduction (i.e., a portion of the household's monthly SNAP benefits are withheld until the claim amount is repaid). States may, however, establish their own cost-effectiveness plans. Under such a plan, if approved by USDA-FNS, a state may modify this threshold for one or more types of overpayments and may create a threshold limit for claims on households currently participating in the program. |

Claims are not always established in the year that the overpayment occurs and claims are not always collected in the year that they are established. State agencies are entitled to retain 35% of the amount they collect on recipient fraud claims and certain recipient error claims, 20% of the amount they collect on all other recipient error claims, and none of the amount they collect on agency error claims.

Recipient Fraud

Detection of Recipient Fraud

State agencies are responsible for administering the recipient side of SNAP (with federal oversight) and for pursuing recipient fraud.110 State agencies must, furthermore, establish and operate a SNAP recipient fraud investigation unit.111 These units detect and punish recipient trafficking, as well as other forms of recipient fraud. USDA-FNS supports state agencies in this capacity by providing technical assistance and setting policy. USDA-OIG, in collaboration with other federal and state law enforcement entities, sometimes criminally pursues recipients who traffic SNAP benefits when such recipients traffic in high dollar amounts of benefits and/or such recipients also engage in other criminal activity. Recipient fraud, like retailer fraud, can be detected through a variety of means, including the following:

Analysis of EBT Transaction Data—Once USDA-FNS has completed the process of administratively penalizing a retailer for retailer trafficking, and the retailer has exhausted their appeal rights,112 then USDA-FNS provides the retailer trafficking case to the appropriate state agency including EBT card numbers which can be used to identify SNAP recipients who may be trafficking.

Social Media—State agencies use automated tools and manual monitoring to detect postings on social media and online commerce websites by individuals attempting to traffic SNAP benefits.

Undercover Investigations—As is done with retailer trafficking cases, state agencies perform undercover investigations to detect recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud.

Multiple Card Replacement—Recipients who frequently request replacement EBT cards are flagged for review as potentially involved in trafficking benefits, because they would request replacements after selling their cards.113 This recipient trafficking detection mechanism was established by an April 2014 USDA-FNS Final Rule.114 In December 2017 USDA-FNS granted a waiver for one state to contact recipients who request a replacement card more than two times in a 12-month period, as opposed to the current regulations' standard of four requests in a 12-month period.115

State Law Enforcement Bureau (SLEB) Agreements—Some state agencies enter into state law enforcement bureau (SLEB) agreements with law enforcement entities in their jurisdictions in order to further their efforts to detect recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud. There are advantages to such arrangements for state agencies; for example, under SLEB agreements, the agency could be notified whenever an individual is arrested in possession of multiple EBT cards, allowing the agency to flag the recipients associated with those EBT cards for potential recipient trafficking.

Tips and Referrals—As is done in detecting retailer trafficking, agencies use tips and referrals to detect recipient trafficking and recipient application fraud.

Data Matching and Other Verification—As is done in detecting recipient errors when applying for SNAP benefits, the data matching and certification process may also provide information useful in detecting recipient application fraud.

Correction of Recipient Fraud

Whenever a SNAP recipient is found to have committed fraud, that individual is subject to individual penalties, such as disqualification. The other members of the SNAP household will not automatically be subject to such penalties, but the adult members of the household will generally be obligated to repay the amount established by the state agency as a claim for overpayment or trafficking. Major penalties associated with recipient fraud include the following:

|

Rights of Recipients Accused of Fraud When a state agency determines that a recipient has committed fraud, the agency provides notice of adverse action to the recipient, which outlines the charges. This notice explains the recipient's right to request a fair hearing (fair hearings may be requested by any recipient aggrieved by a SNAP agency action, not just recipients accused of fraud).116 After a hearing, the recipient is notified of the decision reached and of the recipient's right to request an appeal or rehearing with the state agency. After a rehearing or appeal, the recipient is notified of the decision reached and the recipient's right to request judicial review. Until this process has been exhausted, recipients continue to receive SNAP benefits. Advocates argue that some states' anti-fraud efforts are overly aggressive and deny recipients' access to SNAP when a recipient error, not fraud, may be to blame for an overpayment.117 |

Disqualification—Trafficking and recipient application fraud are types of intentional program violations, and a SNAP recipient found to have committed fraud is generally subject to a period of program disqualification varying from one year to permanent.118 Figure 4 below compares the number of FY2016 SNAP recipient disqualifications to the monthly average number of participating recipients in the state in FY2016. Performing investigations and proving that recipients have committed intentional program violations (in order to disqualify them from SNAP) can require a considerable amount of state agency resources. This chart illustrates the extent to which agencies have prioritized this aspect of SNAP administration relative to their SNAP caseload.

Restitution of Benefits Defrauded (Claims)—A SNAP household must generally repay benefits amounts that are overpaid due to recipient application fraud or are trafficked.119

Comparable Disqualification—If a SNAP recipient is disqualified from any federal, state, or local means-tested public assistance program, then the state agency may impose the same period of disqualification on the individual under SNAP.120 This comparable disqualification is mandatory for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR).

Criminal Charges and Penalties—Generally, if criminal charges are pursued against recipients who traffic benefits or commit recipient application fraud, it is the states that will pursue and prosecute. State fraud laws vary in their penalties for recipient fraud.121 Additionally, as stated in a GAO report from August 2014, each state exercises its discretion differently with respect to filing criminal charges in cases of recipient fraud.122 As with retailer trafficking, USDA-OIG sometimes pursues criminal charges in collaboration with federal and state law enforcement entities against recipients engaged in SNAP fraud.

State Agency Employee Fraud Detection and Correction

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Inspector General (USDA-OIG), in conjunction with local, state, and other federal law enforcement entities, investigates cases of state agency employee fraud and penalizes state agency employees engaged in it. Criminal penalties for state agency employee fraud vary from state to state, and individuals who commit state agency employee fraud may be prosecuted for other crimes (e.g., identity theft) that occurred during the commission of the state agency employee fraud. Penalties for this type of criminal fraud vary but may include imprisonment, probation, and/or monetary restitutions.

State Agency Fraud: SNAP Quality Control

SNAP has long had policies and procedures in place for measuring improper payments—largely, the program's Quality Control (QC) system. QC is currently the basis for levying financial penalties from low-performing states and providing financial performance incentives for the higher-performing and most improved states. In June 2018, following concerns that there had been misreporting of errors, USDA-FNS released a FY2017 NPER under new quality control procedures. This section reviews QC and these developments.

Quality Control: Incentives and Penalties Overview

This section discusses false claims by state agencies with regard to Quality Control (QC) data and state payment error rates (SPERs). As discussed earlier in this report, since 1977, the SNAP Quality Control system has measured improper payments in SNAP, comparing the amounts of overpayments and underpayments that exceed the error tolerance threshold ($38 adjusted annually for inflation)123 to total benefits issuance. The Quality Control process starts with state agency analyses that determine state payment error rates, which are then reviewed by USDA-FNS to develop the SNAP national payment error rate (NPER). After conducting this annual Quality Control review, USDA-FNS awards bonuses to high-performing state agencies and assigns penalties to low-performing state agencies.124

USDA-FNS annually awards high-performance bonuses to up to 10 states with the lowest or most improved state payment error rates. High-performance bonuses must be used by states to improve their administration of SNAP.125 The total annual amount awarded for SPER high-performance bonuses is $24 million.126 The bonuses awarded in FY2014 are summarized in Table 2. Awards for FY2017 have not yet been announced, as of the date of this report.

|

State |

AK |

FL |

KS |

MS |

RI |

SC |

TN |

TX |

VT |

WA |

|

Bonus |

$247 |

$7,742 |

$628 |

$1,302 |

$502* |

$1,672 |

$2,687 |

$6,497 |

$293* |

$2,428 |

Source: USDA-FNS, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/snap/2014-chart-awards.pdf.

Note: Bonus amounts marked with an asterisk "*" are for the most-improved state payment error rates.

State sanctions—known as "liabilities"—are used to punish states that have comparatively high payment error rates. If there is a 95% probability that a state makes payment errors 5% more frequently than the national average, then that state has "exceeded the liability level". If a state exceeds the liability level for two years in a row, then it is assessed a penalty—known as a "liability amount".127 Liability amounts are assessed for only that portion of the state payment error rate that is above 6% (e.g., a state that exceeds the liability level with a state payment error rate of 5.99% would be assessed a $0 liability amount).128 Once assessed, states have the option to pay the liability amount in full or enter into a settlement agreement with USDA-FNS.129