The Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) Program

Congress created the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program to offer long-term, low-cost loans to railroad operators, with particular attention to small freight railroads, to help them finance improvements to infrastructure and investments in equipment. The program is intended to operate at no cost to the government, and it does not receive an annual appropriation. Since 2000, the RRIF program has made 37 loans totaling $5.4 billion (valued at $5.9 billion in 2018 dollars). The program, which is administered by the Build America Bureau within the Office of the Secretary of Transportation, has approved only four loans since 2012.

Congress has authorized $35 billion in loan authority for the RRIF program and repeatedly has urged the Department of Transportation (DOT) to increase the number of loans the program makes. Reports suggest the uncertain length and outcome of the RRIF loan application process and the up-front costs to prospective borrowers are among the elements of the program that have reduced its appeal compared with other financing options available to railroads.

By statute, the Build America Bureau has 90 days from the time a completed application is submitted to render a decision on the application. This timeline becomes uncertain due to the Bureau’s discretion in determining when a loan application is “complete.” A 2014 audit indicated that some loan applications had been in process for more than a year.

Unlike DOT’s other prominent loan assistance program, the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, RRIF requires loan recipients to pay a credit risk premium, which is intended to offset the risk of a default on their loan. The credit risk premium helps the program comply with a congressional requirement that federal loan assistance programs operate at no cost to the federal government. However, it may make RRIF loans less attractive to borrowers than other types of federal, state, or private financing.

Several RRIF loans have been made to government-run intercity passenger rail projects. A number of private companies seeking to build intercity passenger rail lines also have expressed interest in RRIF loans. Changes made by Congress in the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (P.L. 114-94), enacted in December 2015, may lead to even greater use of the RRIF program by sponsors of passenger rail and transit-related projects, as opposed to small freight railroads. Such loans likely would be quite large relative to those RRIF typically extends to small freight railroads, raising questions about the risk to the federal government if the projects are not completed or if they fail to generate sufficient revenue to service the loans.

The Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) Program

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Railroad Industry Background

- RRIF Program

- Program Overview

- Program Performance

- RRIF Program Issues and Options

- Need for Program

- Alternatives to RRIF

- Section 45G Tax Credit

- TIGER Grant Program

- TIFIA Loan Program

- State Programs

- Supportive Policy Options

- Program Effectiveness

- Length of Review Process

- Loan Costs

- Project Requirements

- Loans to Passenger Rail Projects

- Growth in Lending to Passenger Rail Projects

- Unique Risks

Summary

Congress created the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program to offer long-term, low-cost loans to railroad operators, with particular attention to small freight railroads, to help them finance improvements to infrastructure and investments in equipment. The program is intended to operate at no cost to the government, and it does not receive an annual appropriation. Since 2000, the RRIF program has made 37 loans totaling $5.4 billion (valued at $5.9 billion in 2018 dollars). The program, which is administered by the Build America Bureau within the Office of the Secretary of Transportation, has approved only four loans since 2012.

Congress has authorized $35 billion in loan authority for the RRIF program and repeatedly has urged the Department of Transportation (DOT) to increase the number of loans the program makes. Reports suggest the uncertain length and outcome of the RRIF loan application process and the up-front costs to prospective borrowers are among the elements of the program that have reduced its appeal compared with other financing options available to railroads.

By statute, the Build America Bureau has 90 days from the time a completed application is submitted to render a decision on the application. This timeline becomes uncertain due to the Bureau's discretion in determining when a loan application is "complete." A 2014 audit indicated that some loan applications had been in process for more than a year.

Unlike DOT's other prominent loan assistance program, the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, RRIF requires loan recipients to pay a credit risk premium, which is intended to offset the risk of a default on their loan. The credit risk premium helps the program comply with a congressional requirement that federal loan assistance programs operate at no cost to the federal government. However, it may make RRIF loans less attractive to borrowers than other types of federal, state, or private financing.

Several RRIF loans have been made to government-run intercity passenger rail projects. A number of private companies seeking to build intercity passenger rail lines also have expressed interest in RRIF loans. Changes made by Congress in the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (P.L. 114-94), enacted in December 2015, may lead to even greater use of the RRIF program by sponsors of passenger rail and transit-related projects, as opposed to small freight railroads. Such loans likely would be quite large relative to those RRIF typically extends to small freight railroads, raising questions about the risk to the federal government if the projects are not completed or if they fail to generate sufficient revenue to service the loans.

Introduction

The Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program offers long-term, low-interest loans to railroad operators for improving rail infrastructure. The program is intended to operate at no cost to the government and does not receive an annual appropriation. Congress has authorized $35 billion in loan authority for the program, but freight railroads have been relatively unenthusiastic. Since 2000, RRIF has made 37 loans to 29 operators for a total of $5.4 billion, representing $5.9 billion in 2018 dollars. From 2000 through 2015, private railroads' total investment in structures and equipment was approximately $154 billion ($174 billion in 2016 dollars).1 RRIF supplied less than 1% of freight railroads' capital expenditures for track and other structures over that period.

In recent years, sponsors of intercity passenger rail projects have shown increasing interest in the program. About 85% of the RRIF program's nominal loan amount has gone to government-controlled entities for passenger rail projects rather than to freight operators; loans to Amtrak, the national intercity passenger rail provider, alone represent almost 60% of the total nominal loan amount. Part of this activity may be explained by a growing interest in passenger rail services at the state and local level and the scarcity of other funding assistance for such projects, which tend to be extremely costly.

The Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act; P.L. 114-94), enacted in December 2015, included changes intended to make the RRIF program more attractive to potential applicants, though one change—elimination of the requirement that the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), which administers the program, refund borrowers' credit risk premiums—may make the program less attractive. Some of the changes may make the program more useful for funding passenger rail and transit-related projects. The prospect of large loans for private intercity passenger rail and transit-related projects raises questions about potential risks to the RRIF program, because such projects may have no source of earnings until and unless they are completed and, even then, may not be able to generate sufficient revenue to service their loans.

Railroad Industry Background

The railroad industry has changed significantly since Congress created a forerunner of RRIF in 1976. At that time, the nation's railroads were in great financial difficulty, investment in infrastructure and equipment had lagged, and there were questions about the future viability of the industry. Subsequently, Congress significantly deregulated the railroad industry, making it easier for carriers to consolidate and to shed less profitable routes. Since that time, mergers have reduced a large number of regional railroads to a handful of companies that operate across many states (known as Class I carriers).

Deregulation allowed the large railroads to focus their construction and maintenance efforts on heavily trafficked main lines and to stop service on routes that were not profitable. Some of this lightly used trackage was sold to smaller operators, which believed they could build business by working closely with shippers that used or might use the line. These smaller railroads, collectively known as short line railroads, are classified by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) as Class II and Class III carriers.2 Although there are now only seven Class I railroads operating in the United States,3 there are more than 560 short line railroads.4

The Class I freight railroads—large, profitable commercial entities—are able to finance improvements out of their considerable revenues, as well as by issuing stock and by borrowing in the commercial market. Class II and Class III railroads have fewer financing options. Their revenues are smaller, their lines of business typically are more limited than those of the Class I railroads, and their creditworthiness generally is lower. However, nearly half of the nation's short line railroads have come under the control of 27 holding companies,5 potentially offering them easier access to private financing. In addition, a number of short line railroads are terminal switching, port, or harbor rail lines that have a relationship with a Class I railroad, which may help them obtain financing, and some short line railroads are owned by states. These entities typically have easier access to the financial markets than do stand-alone short line railroads.6

Amtrak operates at a loss and relies on federal grants appropriated annually to continue operations. Amtrak's primary service corridor is the Northeast Corridor (NEC), a rail line running from Washington, DC, through New York City to Boston. This line also is used heavily by commuter rail operations and also hosts freight service. There is an estimated backlog of $38 billion in capital investment needed to restore the aging NEC infrastructure to a state of good repair.7 In July 2017 DOT published a proposal for expanded and faster service on the NEC, with a capital cost estimate of $121-$153 billion.8

RRIF Program

Congress created the RRIF program in 19989 and revised it in 2005,10 2008,11 and 2015.12 The program allows DOT to provide credit assistance for rail infrastructure by making low-cost direct loans or providing loan guarantees to project sponsors. Eligible recipients of this assistance include railroads, state and local governments, government-sponsored corporations, and joint ventures that include at least one railroad.

The RRIF program replaced a railroad financing program that Congress created in 1976.13 The original program allowed DOT to provide financial assistance for rail infrastructure by purchasing preference shares or issuing loan guarantees. The authorization to purchase preference shares expired in 1996.

In the 1998 revision that renamed the program, Congress authorized DOT to make direct loans as well as loan guarantees, set an overall cap of $3.5 billion on the total amount of outstanding debt that the program could have at any one time, and reserved almost 30% of that ($1 billion) for projects benefiting short line railroads. In 2005, Congress increased the limit on outstanding debt to $35 billion and increased the amount reserved for smaller freight railroads to $7 billion. The increase was not due to demand for the program—the program had issued a total of less than $1 billion in loans at that point—but in hopes of boosting interest in the program. In 2012, Congress provided that applicants could use future dedicated revenues as security for a RRIF loan. In 2015, it added new types of security that applicants could use to reduce the amount of their credit risk premium, and moved the administration of the program from the FRA to a newly created Build America Bureau.

Projects eligible for RRIF assistance include acquiring, improving, and rehabilitating track, bridges, rail yards, buildings, and shops (or refinancing existing debt that was incurred for these purposes); preconstruction activities; positive train control; transit-oriented development projects; and new rail or intermodal facilities. Loans can be for up to 100% of the project cost, with repayment periods up to 35 years.

The RRIF program is designed to operate at no cost to the government. Applicants are charged a fee of 0.5% of the amount requested to cover the cost of processing their applications. Borrowers are charged another fee (the credit risk premium) at the time a loan is issued to cover the potential cost to the government of the loan not being repaid. The amount of the credit risk premium is based on several factors, including the financial condition of the applicant and the amount of collateral securing the loan.

This no-cost-to-the-government structure is why it was not controversial for Congress to raise the maximum outstanding loan amount from $3.5 billion to $35 billion in 2005. But the up-front costs of a RRIF loan may deter would-be applicants. By contrast, the other major DOT credit assistance program, established in the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA), covers the cost of the credit risk premium for loan recipients (known as TIFIA's subsidy cost). For private loans, the processing costs and credit risk premium typically are folded into the loan repayment schedule rather than being charged up front.

Program Overview

The RRIF program is one of four credit programs run by DOT.14 RRIF loan applications are reviewed by the Build America Bureau, independent financial analysts hired by the Bureau, and DOT's Office of Credit and Finance.15 The Secretary of Transportation has final authority over loan approval.

The appeal of the RRIF program is that the recipient is able to borrow money at the lowest rate available (that paid by the federal government itself)16 and for a longer period of time than most other types of loans would permit. RRIF borrowers can also ask to defer loan repayment for a period of six years (though interest accrues during this period). Alternatively, the Build America Bureau can guarantee a private loan extended at a rate DOT determines to be reasonable; to date, no loan guarantees have been provided through the program.

Congress has imposed certain other restrictions on the program. For example, for FY2017, as in previous years, appropriations legislation prohibited the use of any federal funds to pay the credit risk premium on a RRIF loan.17

Congress has specified18 that in evaluating RRIF applications, the Build America Bureau should favor projects that

- enhance public safety (including installation of positive train control);

- promote economic development;

- enhance the environment;

- enable U.S. companies to be more competitive in international markets;

- are endorsed by the plans prepared under Section 135 of Title 23 by the state or states in which they are located;19

- improve railroad stations and passenger facilities and increase transit-oriented development;

- preserve or enhance rail or intermodal service to small communities or rural areas;

- enhance service and capacity in the national rail system; and

- materially alleviate rail capacity problems that degrade the provision of service to shippers and fulfill a need in the national transportation system.

Program Performance

The RRIF program has used relatively little of its lending authority. RRIF may have a maximum of $35 billion of outstanding loans and loan guarantees. It currently has about 11% of this amount committed. From its inception through January 2018, the RRIF program issued 37 loans for a total amount of $5.4 billion (see Table 1).20 The loans ranged in amounts from $53,000 to $2.45 billion. Twenty-one of the 37 loans have been repaid in full. One loan is in default. The total amount of RRIF loans outstanding as of January 2018 was $4.02 billion.

|

Fiscal Year |

Recipient |

Amount |

|

2002 |

Amtrak |

$100,000,000 |

|

2002 |

Mount Hood Railroad |

2,070,000 |

|

2003 |

Arkansas & Missouri Railroad |

11,000,000 |

|

2003 |

Nashville and Western Railroad |

2,300,000 |

|

2003 |

Dakota Minnesota & Eastern Railroad |

233,601,000 |

|

2004 |

Stillwater Central Railroad |

4,675,250 |

|

2004 |

Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway |

25,000,000 |

|

2005 |

Great Smoky Mountains Railroad |

7,500,000 |

|

2005 |

Riverport Railroad |

5,514,774 |

|

2005 |

Montreal Maine & Atlantic Railwaya |

34,000,000 |

|

2005 |

Tex-Mex Railroad |

50,000,000 |

|

2005 |

Iowa Interstate Railroad |

32,732,533 |

|

2006 |

Virginia Railway Express |

72,500,000 |

|

2006 |

Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway |

14,000,000 |

|

2006 |

Iowa Interstate Railroad |

9,350,000 |

|

2007 |

RJ Corman Railway |

11,768,274 |

|

2007 |

RJ Corman Railway |

47,131,726 |

|

2007 |

Nashville and Eastern Railroad |

4,000,000 |

|

2007 |

Nashville and Eastern Railroad |

600,000 |

|

2007 |

Columbia Basin Railroad |

3,000,000 |

|

2007 |

Great Western Railway |

4,030,000 |

|

2007 |

Dakota Minnesota & Eastern Railroad |

48,320,000 |

|

2007 |

Iowa Northern Railroad |

25,500,000 |

|

2009 |

Georgia & Florida Railways |

8,100,000 |

|

2009 |

Permian Basin Railways, Inc |

64,400,000 |

|

2009 |

Iowa Interstate Railroad |

31,000,000 |

|

2010 |

Denver Union Station Project Authority |

155,000,000 |

|

2010 |

Great Lakes Central Railroad |

17,000,000 |

|

2011 |

Northwestern Pacific Railroad Company and North Coast Railroad Authority |

3,180,000 |

|

2011 |

Amtrak |

562,900,000 |

|

2011 |

C&J Railroad |

56,204 |

|

2012 |

Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority |

83,710,000 |

|

2012 |

Kansas City Southern Railway Company |

54,648,000 |

|

2015 |

New York City Metropolitan Transportation Administration |

967,100,000 |

|

2015 |

The Arkansas and Missouri Railroad Company |

6,809,000 |

|

2016 |

Amtrak |

2,450,000,000 |

|

2018 |

Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority |

220,000,000 |

|

Total |

$5,372,496,761 |

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, "Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing (RRIF)," Executed Loan Agreements, at https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/programs-services/rrif.

Notes: Loan amounts are not adjusted for inflation. Loans in bold have been repaid. A total of 21 loans have been repaid. The total amount of loans that have been made is $5.9 billion in 2018 dollars (nominal dollar values adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Total Non-defense column from Table 10.1: Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2022, published in Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2018 Historical Tables, Budget of the United States Government, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/).

a. Montreal Maine & Atlantic (MMA) was responsible for the July 2013 derailment and explosion of oil transport cars in Lac-Megantic, Canada, which resulted in extensive damage and the deaths of 47 people. MMA entered bankruptcy in August 2013; its loan is in default, with $27.5 million outstanding.

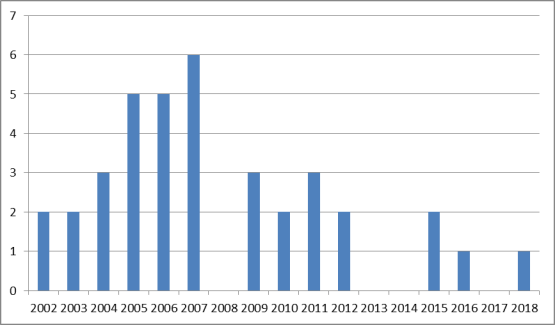

Of the 37 loans made, two-thirds were executed prior to 2008; four have been approved since 2012 (see Figure 1). The Build America Bureau reports that as of January 2018 it was evaluating five applications totaling $5.5 billion.21 (By comparison, FRA was evaluating 13 applications totaling $10 billion in February 2014, suggesting that several applications were withdrawn between 2014 and 2018).22 DOT may approve a loan for less than the amount requested; in the case of a 2007 loan, the Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern Railroad applied for $2.5 billion and received a loan of $48 million.23

Public-sector entities have emerged as the largest borrowers under the RRIF program, representing some 85% of the amount loaned. Most loans to public-sector entities have been intended for passenger rail projects. However, one, an $83.7 million loan to the Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority in 2012, was to support a freight project.

RRIF Program Issues and Options

Need for Program

The policy rationales for the RRIF program are that railroad companies, especially short line companies too small to raise money in the bond market, need better access to long-term, low-cost financing to maintain and expand their networks, and that the safety and efficiency of their networks is a public concern.24 However, it is not clear that railroads, even short line railroads, have significant difficulty financing the maintenance and expansion of their networks. FRA looked at the safety record of short line railroads, taking accident rates as a proxy for the condition of the infrastructure (that is, if the infrastructure were deteriorating, the accident rate likely would increase). FRA found that the number of infrastructure-related accidents per million train-miles on short line railroads declined significantly between 2001 and 2013, from more than eight accidents per million train-miles to fewer than four accidents per million train-miles. FRA stated that "the positive trend, illustrated by a decreasing accident rate, suggests improving maintenance and investment.... "25

Another measure of the condition of short line railroad infrastructure is its capability to handle 286,000-pound rail cars. Since the late 1980s, Class I railroads have moved from maximum car weights of 263,000 pounds to 286,000 pounds. Track and bridges must be strengthened to handle these heavier loads. According to the Association of Short Line Railroads, 39% of short line route-miles were able to handle the 286,000-pound cars in 2002, whereas 57% of a larger number of total route-miles could handle the heavier cars in 2010. FRA stated, after examining both the safety and capacity numbers, that "these data points and trends illustrate that these carriers in aggregate are maintaining their systems and enhancing infrastructure to meet their customer needs."26

On the basis of a 2013 survey of Class II and Class III railroads' estimated spending requirements for infrastructure and equipment, FRA estimated that the total investment needs of short line railroads would be $6.9 billion over the five-year period from 2013 to 2017. The survey respondents anticipated that they would be able to cover about 70% to 75% of their estimated spending needs for infrastructure and equipment during that period, with most of the funding coming from their revenues; they expected about a quarter of the funding to come from other sources, chiefly state (9%) and federal (8%) grants and loans.27 The survey results suggested an estimated gap of around $265 million per year between the available funding and the amount short lines felt was needed.28

Alternatives to RRIF

RRIF is only one of several federal and state programs available to reduce the cost of railroads' investment in infrastructure. Others include the following.

Section 45G Tax Credit

This tax credit, first enacted in 2004, allows Class II and Class III railroads to reduce their taxes by 50% of the cost of track maintenance expenses incurred in a year, up to a limit established by multiplying the railroad's track mileage by $3,500. The cost to the federal government in forgone tax revenue is estimated at $165 million to $202 million per year, which represents investments of roughly $300-$400 million annually.29 In contrast to the RRIF program, this tax credit is targeted exclusively to short line railroads. It does not require the recipient to undertake an uncertain loan application process, with its attendant costs, or to comply with requirements for RRIF loans, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the RRIF program's Buy America policy.30 The tax credit expired on December 31, 2016. Legislation to extend the credit has been introduced in the 115th Congress (H.R. 721; S. 407; S. 2256).

TIGER Grant Program

Congress created a National Infrastructure Investment discretionary grant program within the Office of the Secretary of Transportation in 2009. This program, popularly known as the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant program, made over $5 billion in grants through FY2017. Grants require a 20% match in urbanized areas; in rural areas, no local match is required. Although only governmental entities are eligible to receive grants, applications may represent public-private partnerships. Passenger and freight rail infrastructure projects are eligible uses of TIGER funds. Freight rail projects (including port improvement projects with a rail component) have received nearly $810 million in grants; short line railroad improvement projects have received more than $270 million.31 The program is very competitive, with several times as much funding requested each year as the $500 million typically available for grants.

TIFIA Loan Program

The TIFIA loan program, like the RRIF program, was authorized by Congress in 1998. As of the end of calendar year 2016, the program had assisted 56 projects with a total value of over $82 billion; the federal value of credit assistance provided was more than $20 billion, at a direct cost of more than $1 billion (representing the cost of the credit risk premium and the administrative costs of processing applications).32 Eligible projects include "rail projects involving the design and construction of intercity passenger rail facilities or the procurement of intercity passenger rail vehicles" and "intermodal freight transfer facilities."33 Although five intermodal projects involving rail freight have received assistance, no TIFIA loans have been approved for pure rail projects. Congress appropriates funding to cover the credit risk premium cost of TIFIA loans, reducing the cost of loans to recipients. See Table 2 for a summary of differences between the RRIF and TIFIA programs.

In the FAST Act, the 2015 surface transportation authorization legislation, Congress authorized $1.435 billion through FY2020 to administer the program and cover the credit risk premium. Since DOT assumes a loss ratio of around 10%, the $1.435 billion available after administrative costs gave it the capacity to provide about $14 billion in TIFIA loans or loan guarantees from FY2016 through FY2020.34

|

RRIF |

TIFIA |

|

|

Limit on Total Value of Outstanding Loans |

$35 billion |

—a |

|

Number of Loans/Loan Guarantees Provided |

36 |

56 |

|

Average Assistance Value |

$143 million |

$384 million |

|

Loan Amount as % of Eligible Project Costs |

Up to 100% |

Up to 49%, typically no more than 33% |

|

Loan Term |

Up to 35 years |

Up to 35 years |

|

Up-Front Cost |

Up to 0.5% of loan amount for processing, plus the credit risk premium |

$400,000 to $500,000 for loan processing |

Sources: CRS, based on information from U.S. Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing RRIF, https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/programs-services/rrif; U.S. Department of Transportation, TIFIA 2016 Report to Congress, August 11, 2016, at https://cms.dot.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/TIFIA%20Report%20to%20Congress%202016.pdf.

Note: These programs are not mutually exclusive; at least one project, the redevelopment of Denver Union Station as a multimodal center, received loans from both RRIF and TIFIA.

a. The amount of TIFIA loans is limited by the funding available to the program to cover the subsidy cost of the loans.

State Programs

A number of states have established grant, loan, and tax benefit programs to help short line railroads finance infrastructure or equipment purchases. In its report on Class II and Class III railroad capital needs and funding sources, FRA reported that, in a survey of how short line railroads expected to fund their needs in the near future, respondents expected to get a greater percentage of funding for infrastructure and equipment investments from state programs (9%) than from federal programs (8%).35

Supportive Policy Options

The primary competition for short line and regional railroads is the trucking industry. The degree of competition is affected by the extent of regulation and taxation on the rail and truck sectors. Trucks operate over publicly provided infrastructure (the highway network), whereas railroads are financially responsible for their own infrastructure. Although federal and state taxes on diesel fuel contribute to maintaining the highway infrastructure, studies indicate that heavy trucks cause much more damage to highways than they pay in fuel taxes. This problem is exacerbated by exemptions Congress has provided to limits on truck weights, which raise the productivity of trucking vis-à-vis railroads while increasing the amount of damage the trucks cause to the highway infrastructure.

Congress could aid the short line and regional railroads by, for example, increasing the amount of fuel tax paid by heavy trucks to a level commensurate with the damage they cause to the highway infrastructure and limiting exemptions to truck weight restrictions. Such changes also would benefit the Class I railroads. However, these changes could increase the cost of shipping goods by truck, adversely affecting trucking industry employment. In addition, higher truck rates could affect rail shippers by giving railroads room to raise their own rates.

Program Effectiveness

There are many possible ways of evaluating the effectiveness of the RRIF program. By one measure on which Congress has focused—the extent to which railroads have made use of RRIF loans—the program has not been very effective, considering that less than $6 billion of the $35 billion in loan authority has been used. However, the $35 billion limit appears to have been set somewhat arbitrarily, rather than reflecting an analysis of railroad investment needs that could not be met by other means. The fact that the RRIF program has lent far less than the amount Congress authorized, particularly to private-sector borrowers, may indicate that freight railroads' ability to finance their investment needs without recourse to government support is greater than Congress believed.

Congress has expressed a desire that the program be used more heavily, especially by short line railroads, and has identified two aspects of the program that may be reducing its attractiveness: the uncertain length of the loan review process and the cost to the applicant of the loan. A third aspect that may be reducing the program's attractiveness is the requirement that loan recipients comply with the requirements of the National Environmental Protection Act, various "Buy America" requirements, and federal prevailing wage and employee protection requirements.

Length of Review Process

By statute, a RRIF loan application is supposed to be approved or disapproved within 90 days. But that 90-day clock does not begin until a loan application is considered complete. In a 2014 audit of the program, the DOT Office of Inspector General found that unclear program information resulted in incomplete loan applications that required FRA to work with applicants on completing the applications. The Inspector General determined that due to the extensive loan review process, which involved FRA, outside reviewers, DOT's Office of Credit Oversight and Risk Management, and its Credit Council, the loan application process took a long time and had an uncertain outcome, discouraging potential applicants.36

Management of the program was subsequently transferred to the Build America Bureau. The Bureau published a guide to its credit programs (covering both RRIF and TIFIA) in January 2017.37 The Bureau had five loan applications under review as of January 1, 2018; all were draft applications (after review, an applicant may or may not be invited to submit a final application). The length of time since the draft applications had been submitted was 19 months, 14 months, 10 months, 8 months, and 5 months, suggesting that in spite of the publication of the program guide and other changes made to shorten the review process, it may still be quite lengthy.38

Loan Costs

Federal law requires that federal credit programs operate at no cost to the government. The government faces two primary costs for loan assistance and guarantee programs: that of administering the program, including evaluating applicants, and that of a borrower failing to repay its loan.

To cover the cost of administering the program (including evaluating loan applications), the RRIF program charges loan applicants a nonrefundable fee of up to 0.5% of the loan amount. To protect against the possibility of defaults, federal law requires that loan programs keep enough money in reserve to cover the estimated cost to the government of defaults on the loans made. This reserve amount, which in the case of the RRIF program is paid by the borrower, is referred to as a credit risk premium. A credit risk premium is calculated for each loan, based primarily on the financial soundness of the borrower and the amount of collateral pledged by the borrower. Credit risk premiums for the RRIF program generally have been between 0% and 5% of the loan amount.39 For example, Amtrak paid a 4.424% credit risk premium for its 2011 RRIF loan and 5.8% for its 2016 RRIF loan.40 If collateral of sufficient value is pledged, no credit risk premium may be required.

The 2014 audit of the RRIF program noted that some short line railroads had pointed to the credit risk premium as discouraging them from applying to the program. In response, FRA stated that it has no discretion to subsidize the credit risk premium for applicants. Such a step would require congressional action. As noted above, for several years Congress has included in DOT appropriations bills a provision barring the use of federal funds to pay the credit risk premium.

Prior to the FAST Act, DOT was required to refund the credit risk premium to borrowers after all the loans in their cohort of loans had been repaid. DOT had originally been instructed to establish cohorts of loans for this purpose, with the intent of both maintaining "sufficient balances of credit risk premiums to adequately protect the Federal Government from risk of default, while minimizing the length of time the Government retains possession of those balances."41 However, as of January 2018, DOT has not issued a formal definition of a "cohort of loans." As a result, while 21 RRIF loans have been repaid, DOT has not yet returned any credit risk premiums to their borrowers.

In Section 11607 of the FAST Act (P.L. 114-94), Congress repealed the language requiring DOT to repay the credit risk premium for future loans, leaving the decision about repayment to the discretion of DOT. DOT has reportedly decided that credit risk premiums paid for loans made after enactment of the FAST Act will not be repaid.42

With respect to loans made prior to passage of the FAST Act, the conference committee report accompanying the FAST Act directed DOT to refund credit risk premiums to borrowers that had repaid their RRIF loans, "regardless of whether the loan is or was included in a cohort. The intent of this provision is for the Secretary to pay back such credit risk premium, with interest, as soon as feasible but not later than three months after the date of enactment."43 As noted, more than two years after adoption of this report DOT has yet to repay any credit risk premiums to borrowers that have repaid their loans.

Project Requirements

To qualify for a loan, an applicant must comply with a variety of federal laws, including NEPA, various "Buy America" requirements, and federal prevailing wage and employee protection requirements.44 NEPA requires that FRA review a project's environmental impact.45 The Buy America Act requires that a project receiving a government loan use steel, iron, and other manufactured goods produced in the United States, unless the project sponsor receives a waiver from FRA.46

Loans to Passenger Rail Projects

Growth in Lending to Passenger Rail Projects

The RRIF program was created primarily to support freight rail service, particularly that of small ("short line") railroads. But a significant portion of RRIF assistance has gone to passenger rail service, especially since 2008. The recipients of the greatest amount of assistance have been Amtrak (three loans totaling $3.1 billion) and the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Administration (one loan for $967 million). As of January 2018, just over four-fifths of the total assistance provided by the program has gone to passenger rail projects (see Table 3).

|

Category |

Number of Loans |

Total Amount of Loans |

Average Loan Amount |

|

Freight |

30 |

$1,038 |

$35 |

|

Passenger |

7 |

$4,840 |

$691 |

|

Total |

37 |

$5,878 |

$159 |

Source: CRS, based on RRIF grant information. Nominal dollar values adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Total Non-defense column from Table 10.1: Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2022, published in Executive Office of the President of the United States, Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2018 Historical Tables, Budget of the United States Government, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/.

One cause of much larger loan amounts for passenger projects is that the short line railroads that borrow from RRIF typically have small and thus relatively inexpensive projects; the Class I railroads that might be undertaking larger projects have not made use of RRIF funding. Another cause may be the lack of alternative funding sources for intercity passenger rail projects. In calendar year 2009, Congress appropriated $10.5 billion (later reduced to $10.1 billion through a rescission of appropriated funding) for grants for high-speed and intercity passenger rail projects.47 The availability of that funding generated significant interest on the part of states to establish or expand passenger rail service; FRA reported receiving applications for a total of more than $75 billion.48 Congress provided virtually no funding for intercity passenger rail service expansion from 2010 until 2017, so organizations interested in passenger rail services may have turned to RRIF as an alternative or supplemental source of funding.

Unique Risks

Lending to intercity passenger rail projects creates some unique challenges for RRIF. Passenger rail projects often fail to make an operating profit, and few of them anywhere in the world generate sufficient operating profit to cover their capital costs.

Amtrak, the federally owned intercity passenger railroad operator, has received more than half of all funds loaned by the RRIF program. Amtrak has repaid two of the loans; it does not have to begin repaying the 2016 loan until 2022. Amtrak states that it will service this loan with revenue from its Northeast Corridor operations. However, while Amtrak earns an operating profit on its Northeast Corridor operations, it loses money overall and relies on an annual appropriation of approximately $1.4 billion from Congress to continue operating. Thus, the railroad's ability to repay its RRIF loan depends on the receipt of other federal funds.

In 2010, RRIF extended a $155 million loan to the Denver Union Station Project Authority for the reconstruction of Denver Union Station as an intermodal passenger station. The loan was serviced from the proceeds of tax-increment revenue from development around the station, with a backstop commitment from the City and County of Denver.49 The project repaid both its RRIF and TIFIA loans in February 2017.50

Several private entities seeking to build and operate passenger rail projects have expressed interest in RRIF loans in recent years. Privately owned companies operate passenger rail services in many countries, but they typically pay only a portion of the cost of building and maintaining rail infrastructure, which usually receives some form of government support.

One entity that began operating passenger rail service in 2018, All Aboard Florida (which has branded its trains as Brightline), reportedly applied for a $1.87 billion RRIF loan to develop 110-mile per hour passenger service between Miami and Orlando.51 The company later told the press it was seeking other financing instead of a RRIF loan, and was issued $1.75 billion in private activity bonds by the Florida Development Finance Corporation. The company is using $600 million to pay for upgrades to the line between Miami and West Palm Beach (Phase I), and $1.15 billion to pay for the new high-speed line from its coastal line (at West Palm Beach) to Orlando.52

XpressWest, a proposed privately funded high-speed rail line between Las Vegas and Southern California, reportedly applied for a $5.5 billion RRIF loan in December 2010.53 The chairs of the House and Senate Budget Committees sent a letter to the Secretary of DOT on March 6, 2013, opposing the loan as being too risky;54 on June 28, 2013, DOT issued a letter saying it had suspended review of the XpressWest loan application due to the applicant's difficulties in satisfying Buy America requirements and providing documentation for the loan request.55 A subsequent venture with a Chinese rail company to build the line was terminated, reportedly also due to difficulties in satisfying the Buy America requirements of the RRIF program.56 The Texas Central Railway, a private group proposing to build a high-speed line between Dallas and Houston, has said that it is considering seeking a loan from the RRIF or TIFIA programs but that it presently is not eligible to apply.57 To date, FRA has approved no RRIF loans to private passenger rail operators.

If such loans are extended, they are likely to be quite large relative to the loans RRIF has extended for freight projects and may pose different risks. RRIF loans for freight projects typically are for the purpose of improving an operating railroad that already generates revenue from customers. Those existing facilities may serve as collateral for the loans. Some of the private passenger rail projects now under development, by contrast, involve provision of new services on trackage that has yet to be built, potentially leaving the RRIF program with a significant risk of loss if the project is not completed.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Association of American Railroads, Railroad Facts, annual, 2015 & 2016 editions, "Capital Expenditures," p. 46. Figures inflated using the Chained GDP column from Table 10.1, "Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables," from the "Historical Tables" volume of the annual Budget of the United States. |

| 2. |

The classification of a railroad as being in Class I, II, or III is based on the company's annual revenue; the threshold amounts are adjusted for inflation each year and are roughly $450 million and above for a Class I, between $40 and $450 million for a Class II, and below $40 million for a Class III. |

| 3. |

The seven Class I railroads are freight rail companies; Amtrak is not included in the category. |

| 4. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Summary of Class II and Class III Railroad Capital Needs and Funding Sources: A Report to Congress, October 2014, p. iv, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Elib/Document/14131. |

| 5. |

For example, Genesee & Wyoming Inc. owns 113 short line and regional freight railroads in the United States and another seven outside the United States; it would qualify as a Class I railroad if its U.S. operations were considered as a single rail operator. |

| 6. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Summary of Class II and Class III Railroad Capital Needs and Funding Sources: A Report to Congress, October 2014, p. v, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Elib/Document/14131. |

| 7. |

Northeast Corridor Commission, Northeast Corridor Capital Investment Plan, Fiscal Years 2018-2022, p. 8, http://www.nec-commission.com/capital-investment-plan/plan/NEC-Capital-Investment-Plan-18-22.pdf |

| 8. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Record of Decision for A Rail Investment Plan for the Northeast Corridor, Tier 1 Final Environmental Impact Statement, July 2017, http://www.necfuture.com/. |

| 9. |

P.L. 105-178, Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, §7203. |

| 10. |

P.L. 109-59, Safe, Accountable, Flexible and Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users, §9003. |

| 11. |

P.L. 110-432, Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, Division A, §701(e). |

| 12. |

P.L. 114-94, Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act, Title XI, Subtitle F. |

| 13. |

P.L. 94-210, the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, Title V. |

| 14. |

The other three are the TIFIA Program, the Maritime Guaranteed Loan (Title XI) Program, and the Minority Business Resource Center (MBRC) Short-Term Lending Program. These programs all must conform to the requirements of the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990. |

| 15. |

The Office of Credit and Finance consists of eight to 11 DOT officials, including the Deputy Secretary of Transportation (the chair) and the administrators of several DOT operating agencies. |

| 16. |

The interest rate on a RRIF loan is equal to the rate paid by the U.S. Treasury to borrow for a similar period of time as of the date the loan is approved. |

| 17. |

P.L. 115-31, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, Division K, Title I. |

| 18. |

In 45 U.S.C. §822(c). |

| 19. |

This refers to state transportation plans and state transportation improvement programs, which indicate the transportation projects states plan to undertake in the near future. |

| 20. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, "Railroad Rehabilitation & Improvement Financing (RRIF)," "Executed Loan Agreements," at https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/programs-services/rrif. |

| 21. |

As directed in the FAST Act (codified at 45 U.S.C. 822(i)(5)), DOT now posts a monthly report on its website providing summary information about each loan application under consideration; see https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/programs-and-services/rrif/railroad-rehabilitation-and-improvement-financing-rrif-program-dashboard. |

| 22. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, FY2015 Budget Estimate, February 2014, p. 128, at http://www.dot.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/FRA-FY2015-Budget-Estimates.pdf. |

| 23. |

The loan request was part of a $6.5 billion plan to expand access to coal fields in Wyoming and Montana. Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern subsequently was acquired by a Class I railroad (Canadian Pacific) in 2008, and the loan (along with an earlier RRIF loan) was repaid. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern Railroad Powder River Basin Expansion Project Environmental Impact Statement and Section 4(f)/303 Statement, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Page/P0234; Greg Gormick, "Steady As She Goes," Railway Age, November 2008, p. 32; personal communication from FRA. |

| 24. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, FY2016 Budget Estimate, p. 122, at http://www.dot.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/FY2016-BudgetEstimate-FRA.pdf. |

| 25. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Summary of Class II and Class III Railroad Capital Needs and Funding Sources: A Report to Congress, October 2014, p. 4, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Elib/Document/14131. |

| 26. |

Ibid., pp. 5-6. |

| 27. |

Ibid., pp. 22-24. |

| 28. |

FRA extrapolated Class II and III investment needs from 2013 to 2017 to be $5.3 billion (ibid., p. 23); respondents anticipated that they would be able to cover around 70% (pp. 22-23) to 75% of their investment needs (ibid., p. 24), leaving a shortfall of around one-fourth of the estimated $5.3 billion, or $1.3 billion over five years, around $265 million annually. |

| 29. |

American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association, "The 45G Short Line Railroad Tax Credit," at http://www.aslrra.org/legislative/Short_Line_Tax_Credit_Extension. |

| 30. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of Inspector General, Audit Report: Process Inefficiencies and Costs Discourage Participation in FRA's RRIF Program, June 10, 2014, CR-2014-054, Exhibit E, pp. 19-20, at https://www.oig.dot.gov/sites/default/files/RRIF%20final.pdf. |

| 31. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Summary of Class II and Class III Railroad Capital Needs and Funding Sources: A Report to Congress, October 2014, p. 16, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Elib/Document/14131. |

| 32. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, TIFIA 2016 Report to Congress, August 11, 2016, https://cms.dot.gov/policy-initiatives/tifia/2016-tifia-report-congress. |

| 33. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, TIFIA Program Guide, December 2009, p. 3-1, at http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/tifia/tifia_program_guide.pdf. |

| 34. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, TIFIA 2016 Report to Congress, August 11, 2016, at https://cms.dot.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/TIFIA%20Report%20to%20Congress%202016.pdf. |

| 35. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, Summary of Class II and Class III Railroad Capital Needs and Funding Sources: A Report to Congress, October 2014, pp. 23-24 and Figure 3, at https://www.fra.dot.gov/Elib/Document/14131. |

| 36. |

To cite some extreme cases, the DOT Inspector General's audit found that four RRIF loan applications were still in pending status after more than two years. U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of the Inspector General, Audit Report: Process Inefficiencies and Costs Discourage Participation in FRA's RRIF Program, CR-2014-054, June 10, 2014, p. 18, at https://www.oig.dot.gov/sites/default/files/RRIF%20final.pdf. |

| 37. |

Available at https://cms.dot.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/Bureau%20Credit%20Programs%20Guide_January_2017.pdf. |

| 38. |

See Build America Bureau, Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) Program Dashboard, January 1, 2018, https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/programs-and-services/rrif/railroad-rehabilitation-and-improvement-financing-rrif-program-dashboard. |

| 39. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of the Inspector General, Audit Report: Process Inefficiencies and Costs Discourage Participation in FRA's RRIF Program, CR-2014-054, June 10, 2014, p. 20, at https://www.oig.dot.gov/sites/default/files/RRIF%20final.pdf. |

| 40. |

National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Consolidated Financial Statements, Years Ended September 30, 2016 and 2015, with Report of Independent Auditors, at https://www.amtrak.com/ccurl/736/320/Audited-Consolidated-Financial-Statements-FY2016.pdf, p. 24. |

| 41. |

45 U.S.C. 822(f)(4). This passage was repealed by the FAST Act. |

| 42. |

The Build America Bureau's Credit Programs Guide, published in March 2017, does not address the issue of what happens to a borrower's credit risk premium after a loan is repaid. However, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports that FRA officials said credit risk premiums paid after passage of the FAST Act are not refundable; see https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/678388.pdf, p. 9. |

| 43. |

From the conference report on H.R. 22, the Surface Transportation Reauthorization and Reform Act of 2015, published in the Congressional Record, December 1, 2015, p. H8809. |

| 44. |

These requirements apply to both the RRIF and TIFIA program. U.S. Department of Transportation, Build America Bureau, Credit Programs Guide, March 2017, Section 3-3. |

| 45. |

Section 11504 of the FAST Act directed DOT to propose a regulation exempting railroad rights-of-way from NEPA review, similar to an existing exemption for interstate highways; this would greatly reduce any NEPA compliance burden for most RRIF loan applicants. This regulation is in progress. |

| 46. |

See CRS Report R44266, Effects of Buy America on Transportation Infrastructure and U.S. Manufacturing: Policy Options, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 47. |

Congress appropriated $8 billion in P.L. 111-5, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; also known as the economic stimulus act), and $2.5 billion in P.L. 111-117, the Consolidated Appropriations Act. Congress rescinded $400 million of this funding in 2010 (in P.L. 112-10 §2222). |

| 48. |

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Railroad Administration, "High Speed Intercity Passenger Rail (HSIPR) Program," at http://www.fra.dot.gov/Page/P0134. |

| 49. |

Regional Transportation District, Denver Union Station, at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/conferences/2014/Finance/14.Lien,Marla.pdf, pp. 10-11; Fitch Ratings, "Fitch Affirms Denver Union Station Project Authority's (CO) 2010 Senior Notes at 'A,'" press release, December 5, 2014, at http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/05/ny-fitch-ratings-denver-idUSnBw055872a+100+BSW20141205. |

| 50. |

City of Denver, Department of Finance, "Denver Union Station revenues exceeding projections, positioning City and RTD [Regional Transportation District] to save money with new refinancing agreement," February 3, 2017, at https://www.denvergov.org/content/denvergov/en/denver-department-of-finance/newsroom/news-releases/2017/denver-union-station-revenues-exceeding-projections—positioning.html. |

| 51. |

Lidia Dinkova, "All Aboard Florida on line for government aid," Miami Today, October 22, 2014, at http://www.miamitodaynews.com/2014/10/22/aboard-florida-line-government-aid/. |

| 52. |

Kim Miller, "All Aboard Florida seeks private financing to replace or augment federal loan request," Palm Beach Post, October 7, 2014, at http://realtime.blog.palmbeachpost.com/2014/10/07/all-aboard-florida-seeks-private-financing-to-replace-or-augment-federal-loan-request/; Lis Broadt, "Brightline's $600 million of bonds approved by Florida Development Finance Corp.," TC Palm, October 30, 2017, https://www.tcpalm.com/story/news/local/shaping-our-future/2017/10/30/brightline-all-aboard-florida-finance-development-corporation-care-fl-east-coast-railway-fortress/815335001/. |

| 53. |

Richard N. Velotta, "High-speed rail project waiting on $5.5 billion government loan," VegasINC, February 12, 2013, at http://www.vegasinc.com/business/2013/feb/12/high-speed-rail-project-waiting-55-billion-governm/. |

| 54. |

Letter from Representative Paul Ryan, Chairman of the House Budget Committee, and Senator Jeff Sessions, Ranking Member of the Senate Budget Committee, to Ray H. LaHood, Secretary of Transportation, March 6, 2013, at https://www.budget.senate.gov/chairman/newsroom/press/sessions-ryan-call-for-halt-on-taxpayer-funding-for-risky-high-speed-rail-project. |

| 55. |

Natalie Rodriguez, "Feds halt Review of $5.5B Loan For Vegas Rail Plan," Law360, July 18, 2013, at http://www.law360.com/articles/458185/feds-halt-review-of-5-5b-loan-for-vegas-rail-plan. |

| 56. |

Julie Makinen, "China will not build L.A.-to-Vegas rail line—U.S. company calls the deal off," Los Angeles Times, June 8, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-xpresswest-rail-line-20160608-snap-story.html. |

| 57. |

Texas Central Railway, "Answers to your Questions: Taxpayer Funding," at http://texascentral.com/answers-to-your-questions/, accessed May 9, 2017. That page is no longer available; as of January 30, 2018, another page says "the project will explore all forms of capital available to private companies to finance debt for the project, including federal loan programs like RRIF and TIFIA." https://www.texascentral.com/rumors-vs-reality/project-financing/. |