Introduction

This report is an overview of U.S. foreign assistance to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).1 It includes a brief historical review of foreign aid levels, a description of specific country programs,2 and analysis of current foreign aid issues.3 It also provides analysis of the Administration's FY2021 budget request for State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations in the MENA region.

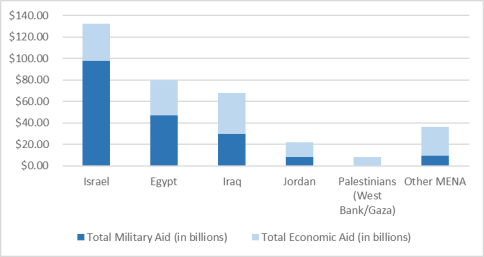

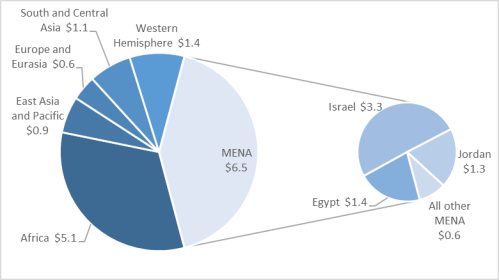

Congress authorizes and appropriates foreign assistance and conducts oversight of executive agencies' management of aid programs. As the largest regional recipient of U.S. economic and security assistance (see Figure 1 below), the Middle East is perennially a major focus of interest as Congress exercises these powers.

|

Figure 1. FY2021 Request for Regional Bilateral Aid current U.S. dollars in billions |

|

|

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justification FY2021. |

The foreign aid data in this report is based on a combination of resources, including USAID's U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants Database (also known as the "Greenbook"), appropriations data collected by the Congressional Research Service from the State Department and USAID, data extrapolated from executive branch agencies' notifications to Congress, and information published annually in the State Department and USAID Congressional Budget Justifications.

The release of this report has coincided with the global spread of the Coronavirus Disease 2019, or COVID-19 (see text box below). The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to affect all MENA countries, and may significantly affect poorer nations that benefit from U.S. and other international assistance. Much of the data presented in this report predates the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

COVID-19 Pandemic in MENA Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many MENA countries were already under political and economic strain. According to one USAID-funded 2018 study, MENA countries had some of the world's lowest levels of public expenditure on health, and access to health services varied greatly across and within countries, despite overall improvements in prior decades.4 In addition to these underlying vulnerabilities, the onset of the pandemic coincided with an oil production glut and a concomitant drop in energy prices, linked to disputes among producers and reduced global demand. As the COVID-19 pandemic spreads across the MENA region, every country is projected to face economic difficulties on par with or possibly even more severe than the 2008-2009 Great Recession, during which GDP in Middle East countries contracted by more than 11% in the years prior to the "Arab Spring" uprisings.5 Several countries appear particularly vulnerable. Iran was an early global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.6 Iraq and Lebanon saw major street protests in 2019 and, in Lebanon's case, the first government sovereign default in its nation's history, and both appear ill-equipped to deal with yet another major economic and social disruption. The COVID-19 pandemic also poses severe challenges for desperate populations in war-torn parts of the Middle East. After 10 years of civil war, some 6.2 million Syrians remain internally displaced, with many living in overcrowded internally displaced person (IDP) camps or informal settlements where they are likely unable to access clean water, sanitation facilities, or medical care. In Yemen, where conflict has contributed to what officials already have called the worst humanitarian crisis in the world, health care capacity is severely limited. Officials from international organizations have voiced concerns about a major COVID-19 outbreak in the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip, given the acute humanitarian challenges in Gaza and the blockade that restricts the movement of people and goods in and out of the territory. The densely populated territory of nearly 2 million Palestinians has a weak health infrastructure and many other challenges related to sanitation and hygiene.7 As of mid-April 2020, the Administration had allocated some emergency humanitarian assistance to the region as a first response to the COVID-19 pandemic. On May1, the State Department announced that it would provide an estimated $114.1 million in assistance to various MENA countries to help prepare laboratory systems, implement a public-health emergency plan for points of entry, activate case-finding and event-based surveillance for influenza-like illnesses, and assist vulnerable refugee populations. To date, Congress has appropriated almost $1.8 billion in emergency foreign assistance funds through two supplemental appropriations bills to address the impact of COVID-19. See CRS In Focus IF11496, COVID-19 and Foreign Assistance: Issues for Congress, by Nick M. Brown, Marian L. Lawson, and Emily M. Morgenstern. |

Foreign Aid to Support Key U.S. Policy Goals

U.S. bilateral assistance to MENA countries is intended to support long-standing U.S. foreign policy goals for the region, such as containing Iranian influence, countering terrorism, preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, preserving the free-flow of maritime commerce and energy resources, promoting Israeli-Arab peace, and preserving the territorial integrity and stability of the region's states. U.S. foreign assistance (from global accounts/non-bilateral) also is devoted to ameliorating major humanitarian crises stemming from ongoing conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere.

As in previous years, the bulk of U.S. foreign aid to the MENA region continues to be focused on assistance (mostly military) to three countries: Israel, Egypt, and Jordan. Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of U.S. foreign assistance since World War II. Almost all current U.S. aid to Israel is in the form of military assistance, and U.S. military aid for Israel has been designed to maintain Israel's "qualitative military edge" (QME) over neighboring militaries. U.S. military aid to Egypt and Jordan (which have been at peace with Israel since 1979 and 1994, respectively) is designed to encourage continued Israeli-Arab cooperation on security issues while also ensuring interoperability between the United States and its Arab partners in the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility.

|

Other Sources of U.S. Foreign Aid to the Middle East For the past two decades, successive Administrations and Congresses have drawn on sources of funding beyond State Department/USAID-administered bilateral aid appropriations to address challenges created by conflicts in the MENA region. The United States has devoted significant resources toward several major humanitarian crises stemming from ongoing conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and elsewhere. For example, between FY2012 and FY2019, successive Administrations allocated more than $10.6 billion in response to the Syrian refugee crisis, most of which came from humanitarian assistance funding appropriated by Congress.8 The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), an independent U.S. government entity established in 2004, provides assistance to support multiyear, large-scale projects by certain foreign governments committed to implementing free market and democratic reforms.9 Separately, the United States is the top source of financing for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has provided loans to multiple MENA countries in recent years to ensure their ability to balance deficits and ensure macroeconomic stability, in exchange for various policy reform commitments. Separately, Congress has authorized and appropriated funding to the Department of Defense (DOD) to train and equip foreign security forces for a range of purposes, including counterterrorism. Countries such as Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Tunisia have been prominent beneficiaries of such programs. As directed by Congress, many DOD security cooperation programs are subject to State Department joint planning and/or concurrence. Major security cooperation authorities and programs under which DOD has provided assistance to MENA countries include the following: 10 U.S.C. 333 (commonly referred to as DOD's "Global Train and Equip authority"),10 the Coalition Support Fund (CSF),11 the Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF),12 and the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program.13 |

The United States also has provided economic assistance to some MENA countries focusing on education, water, health, and economic growth initiatives. In part, U.S. bilateral economic assistance is premised on the idea that governments across the MENA region have had increasing difficulty meeting the expectations of their young citizens. Public dissatisfaction over quality of life issues and lack of economic opportunities persist in many MENA countries. According to the Arab Youth Survey, the rising cost of living and unemployment are the two main obstacles facing Middle East youth today.14 Arab Barometer, a U.S.-funded, nonpartisan research network that provides insight into Arab public attitudes, also notes that widespread youth discontent about their economic prospects translates into broad frustration with government efforts to create employment opportunities. In recent years, as popular protests have proliferated across the MENA region, governments have continued to grapple with systemic socioeconomic challenges, such as corruption, over-reliance on oil, inefficient public sectors, low rates of spending on health and education, and soaring public debt.15

The Trump Administration's FY2021 Aid Budget Request for the MENA Region

Since 1946, the MENA region has received the most U.S. foreign assistance worldwide, reflecting significant support for U.S. partners in Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq (see Figure 2).16 For FY2021, Israel, Egypt, and Jordan combined would account for nearly 13.5% of the total international affairs request.

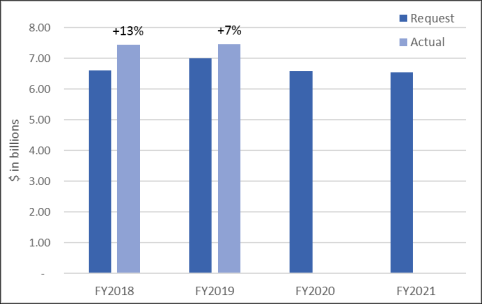

Reducing MENA Aid. For FY2021, the Administration proposes to spend an estimated $6.6 billion on bilateral assistance to the MENA region, a figure that would be nearly equal to the 2020 request but 12% less than what Congress appropriated for 2019 (see Figure 3). In order to achieve this 12% proposed reduction, the Administration's FY2021 request would reduce total military and economic assistance to Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia by a combined $544 million. It also seeks to reduce total aid to Jordan by $250 million and, as it did the previous year, does not request Economic Support Fund/Economic Support and Development Fund (ESF/ESDF)17 for stabilization programs in Syria.18 In its FY2021 request to Congress, the Administration reiterated from the previous year that it seeks to "share the burden" of economically aiding MENA countries with the international community while aiming to build countries' "capacities for self-reliance."

Stabilization Support for Iraq, Syria, and Beyond. For FY2021, the Administration is again requesting that Congress provide it flexibility in allowing up to $160 million in funding appropriated to various bilateral aid accounts to be used for the Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF). The RRF is designed to assist areas liberated or at risk from the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da'esh) and other terrorist organizations (see "Potential Foreign Aid Issues for Congress" below). According to the Congressional Budget Justification (CBJ), "ESDF funding in the RRF will allow the State Department and USAID to support efforts in places like Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen, where the situation on the ground changes rapidly, and flexibility is required." Among other things, funds designated for RRF purposes have supported Iraqi communities through contributions to the United Nations Development Program's Funding Facility for Stabilization (UNDP-FFS). The Trump Administration had ended U.S. contributions to stabilization efforts in Syria, but notified Congress of an intended obligation in 2020 and indicates that it may use FY2021 funds for programs in Syria.

|

Figure 3. MENA Aid Budget Requests vs. Appropriations: FY2018-FY2021 current dollars in billions |

|

|

Source: State Department annual Congressional Budget Justifications FY2017 - FY2021. |

No Funds for the Palestinians. For the first time in over a decade, an Administration has not requested any U.S. bilateral economic or security assistance aid for the Palestinians (see "Potential Foreign Aid Issues for Congress" section below). The Trump Administration, having clashed repeatedly with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, has significantly reduced bilateral funding to the West Bank and Gaza, and has discontinued contributions to U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) for Palestinian refugees. Moreover, as a result of provisions in the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253), no bilateral assistance has been delivered to the Palestinians since January 2019.19 The Administration did suggest that funds from its re-proposed "Diplomatic Progress Fund" ($225 million) could be used to "resume security assistance in the West Bank" or support critical diplomatic efforts, such as "a plan for Middle East peace." In FY2020, the Administration requested $175 million in ESDF for the Diplomatic Progress Fund, though Congress did not fund it in the FY2020 Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, P.L. 116-94 (referred to herein as P.L. 116-94).

Table 1. U.S. Foreign Aid to MENA Countries: FY2016 - FY2021

current U.S. dollars in millions, actual or requested bilateral assistance funds

|

|

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

|

Algeria |

2.59 |

1.82 |

2.12 |

1.48 |

N/A |

3.30 |

|

Bahrain |

5.82 |

1.04 |

0.29 |

0.57 |

N/A |

0.65 |

|

Egypt |

1,448.95 |

1,353.54 |

1,413.67 |

1,419.30 |

1,431.80 |

1,381.85 |

|

Iraq |

405.35 |

861.33 |

403.28 |

451.51 |

451.60 |

124.50 |

|

Israel |

3,100.00 |

3,175.00 |

3,100.00 |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

|

Jordan |

1,274.93 |

1,319.83 |

1,525.01 |

1,524.99 |

1,525.00 |

1,275.00 |

|

Lebanon |

213.46 |

208.41 |

245.94 |

242.29 |

242.29 |

133.16 |

|

Libya |

18.50 |

139.20 |

33.00 |

33.00 |

40.00 |

21.44 |

|

Morocco |

31.74 |

38.58 |

38.65 |

38.49 |

41.00 |

13.50 |

|

Oman |

5.42 |

3.94 |

3.75 |

3.12 |

N/A |

2.70 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Syria |

177.14 |

422.65 |

- |

40.00 |

40.00 |

- |

|

Tunisia |

141.85 |

205.23 |

165.31 |

191.32 |

191.40 |

83.85 |

|

West Bank & Gaza |

261.34 |

291.14 |

61.00 |

0.60 |

150.00 |

- |

|

Yemen |

203.40 |

370.60 |

315.52 |

37.30 |

40.00 |

36.45 |

|

Total |

7,290.49 |

8,392.32 |

7,307.55 |

7,283.96 |

7,453.09 |

6,376.40 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94, Division G of the Joint Explanatory Statement (JES) accompanying P.L. 116-94, and CRS calculations. Figures may reflect rounding. N/A means no dollar amount specified in enacted bill or JES.

Select Country Summaries

Israel20

Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of U.S. foreign assistance since World War II. To date, the United States has provided Israel $142.3 billion (current, or noninflation-adjusted, dollars) in bilateral assistance and missile defense funding. Almost all U.S. bilateral aid to Israel is in the form of military assistance.

In 2016, the U.S. and Israeli governments signed a 10-year Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on military aid, covering FY2019 to FY2028. Under the terms of the MOU, the United States pledges (pending congressional appropriation) to provide Israel $38 billion in military aid ($33 billion in Foreign Military Financing or FMF grants plus $5 billion in missile defense appropriations). This MOU replaced a previous $30 billion 10-year agreement, which ran through FY2018.

|

Top Ten FMF Recipients: FY2021 Request Israel: $3,3 billion Egypt: $1.3 billion Jordan: $500 million Ukraine: $115 million Lebanon: $50 million Tunisia: $40 million Philippines: $40 million Georgia: $20 million Colombia: $20 million Vietnam: $10.9 million |

Israel is the largest recipient of FMF. For FY2021, the President's request for Israel would encompass approximately 59% of total requested FMF funding worldwide.

Israel uses most FMF to finance the procurement of advanced U.S. weapons systems. In March 2020, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) notified Congress of a planned sale to Israel of eight KC-46A Boeing "Pegasus" aircraft for an estimated $2.4 billion. According to Boeing, the KC-46A Pegasus is a multirole tanker (can carry passengers, fuel, and equipment) that can refuel all U.S. and allied military aircraft. The Israeli Air Force's current fleet of tankers was originally procured in the 1970s, and it is anticipated that Israel will be able to use the KC-46A to refuel its F-35 fighters. Israel is the first international operator of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the Department of Defense's fifth-generation stealth aircraft considered to be the most technologically advanced fighter jet ever made. After Japan, Israel will become the second foreign user of the KC-46A.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 request |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

|

|

FMF |

3,100.00 |

3,175.00 |

3,100.00 |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

3,300.00 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Notes: Funding totals do not include monies allocated through Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA).

Egypt21

Since the 1979 Israeli-Egyptian Peace Treaty, the United States has provided Egypt with large amounts of foreign assistance. U.S. policymakers have routinely justified this aid to Egypt as an investment in regional stability, built primarily on long-running military cooperation and the perceived need to sustain the treaty. Egypt has used FMF to purchase major U.S. defense systems, such as the F-16 fighter aircraft, the M1A1 Abrams battle tank, and the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter.

U.S. economic aid to Egypt (funded through ESF) is divided into two components: (1) USAID-managed programs (public health, education, economic development, democracy and governance); and (2) the U.S.-Egyptian Enterprise Fund (EAEF).22 Since its inception in FY2012, Congress has appropriated $300 million in ESF for the EAEF.

Egypt's governance and human rights record has sparked regular criticism from U.S. officials and some Members of Congress (see "Potential Foreign Aid Issues for Congress" section below). Since FY2012, Congress has passed appropriations legislation that withholds the obligation of FMF to Egypt until the Secretary of State certifies that Egypt is taking various steps toward supporting democracy and human rights. With the exception of FY2014, lawmakers have included a national security waiver to allow the Administration to waive these congressionally mandated certification requirements under certain conditions. For FY2019, the Trump Administration has obligated $1 billion in FMF for Egypt, of which $300 million in FY2019 FMF remains withheld until the Secretary issues a determination pursuant to Section 7041(a)(3)(B) of P.L. 116-6, the FY2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act. The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94) also withholds $300 million in FMF until a certification or waiver is issued.

For the past three fiscal years (see Table 3), Congress has appropriated over $1.4 billion in total bilateral aid for Egypt and has added $30 million to $50 million in ESF above the president's request for USAID programs in Egypt.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

142.65 |

112.50 |

106.87 |

112.50 |

125.00 |

142.65 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

1,300.00 |

1,234.30 |

1,300.00 |

1,300.00 |

1,300.00 |

1,300.00 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

1.80 |

1.74 |

1.80 |

1.80 |

1.80 |

1.80 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

2.50 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

2.50 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Jordan23

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is also one of the largest recipients of U.S. foreign aid globally. Like Israel, the United States and Jordan have signed an MOU on foreign assistance, most recently in 2018. The MOU, the third such agreement between the United States and Jordan, commits the United States (pending congressional appropriation) to provide $1.275 billion per year in bilateral foreign assistance over a five-year period for a total of $6.375 billion (FY2018-FY2022).24

U.S. military assistance primarily enables the Jordanian military to procure and maintain U.S.-origin conventional weapons systems. FMF overseen by the State Department supports the Jordanian Armed Forces' multi-year (usually five-year) procurement plans, while DOD-administered security assistance supports ad hoc defense systems to respond to emerging threats.

The United States provides economic aid to Jordan for (1) budgetary support (cash transfer), (2) USAID programs in Jordan, and (3) loan guarantees. The cash transfer portion of U.S. economic assistance to Jordan is the largest amount of budget support given to any U.S. foreign aid recipient worldwide.25 U.S. cash assistance is provided to help the kingdom with foreign debt payments, Syrian refugee support, and fuel import costs (Jordan is almost entirely reliant on imports for its domestic energy needs). ESF cash transfer funds are deposited in a single tranche into a U.S.-domiciled interest-bearing account and are not commingled with other funds. The U.S. State Department estimates that, since large-scale U.S. aid to Syrian refugees began in FY2012, it has allocated more than $1.3 billion in humanitarian assistance from global accounts for programs in Jordan.26

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Notes: Funding levels for FY2020 enacted include $125 million in ESF from prior acts. Under P.L. 116-6 (FY2019 omnibus), Congress provided an additional $50 million in prior-year Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF) aid for Jordan.

Iraq27

The United States funds military, economic, stabilization, and security programs in Iraq, with most assistance funding provided through the Defense Department Counter-ISIS Train and Equip Fund (CTEF). From FY2015 through FY2020, Congress authorized and appropriated more than $6.5 billion in Defense Department funding for train and equip assistance in Iraq.

Iraq began purchasing U.S.-origin weapons systems using its own national funds through the Foreign Military Sales program in 2005,28 and the United States began providing FMF to Iraq in 2012 in order to help Iraq sustain U.S.-origin systems. Between 2014 and 2015, as Iraq and the United States battled the Islamic State throughout northern and western Iraq, FMF funds were "redirected to urgent counterterrorism requirements" including ammunition and equipment."29 A $250 million FY2016 FMF allocation subsidized the costs of a $2.7 billion FMF loan to support acquisition, training, and continued sustainment of U.S.-origin defense systems.

U.S. economic assistance to Iraq has supported public financial management reform, United Nations-coordinated stabilization programs, and loan guarantees. The Obama Administration and Congress provided a U.S. loan guarantee in 2017 to encourage other lenders to purchase bonds issued by Iraq to cover budget shortfalls. The Trump Administration has directed U.S. stabilization support since 2017 to prioritize programs benefitting persecuted Iraqi religious minority groups. P.L. 116-94 directs stabilization assistance to Anbar province and appropriates bilateral economic assistance, international security assistance, and humanitarian assistance for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The act also directs funds to support transitional justice and accountability programs for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in Iraq.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

||

|

|

122.50 |

553.50 |

100.00 |

150.00 |

150.00 |

75.00 |

|

|

|

250.00 |

250.00 |

250.00 |

250.00 |

250.00 |

- |

|

|

|

0.99 |

0.70 |

0.82 |

0.91 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

11.00 |

0.20 |

5.60 |

5.60 |

5.60 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

20.86 |

56.92 |

46.86 |

45.00 |

45.00 |

47.50 |

|

|

|

405.35 |

861.33 |

403.28 |

451.51 |

451.60 |

124.50 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94 and accompanying explanatory statement, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Tunisia30

As of early 2020, Tunisia remained the sole MENA country to have made a durable transition to democracy since the 2011 wave of Arab uprisings. U.S. bilateral aid has increased significantly since then, supporting economic growth initiatives, good governance, and security assistance.

U.S.-Tunisia security cooperation has expanded since 2011, as Tunisia has sought to maintain its U.S.-origin defense materiel, reform its security institutions, and respond to evolving terrorist threats. The United States has supported Tunisia's security sector reform efforts with $12 million to $13 million per year in State Department-administered funding for law enforcement strengthening and reform. Over the last five years, Congress has appropriated $65 million to $95 million per year in bilateral FMF for Tunisia (see Table 6). DOD has provided substantial additional counterterrorism and border security assistance for Tunisia under its "global train and equip" authority (currently, 10 U.S.C. 333) and separate nonproliferation authorities.

Since the Trump Administration issued its first aid budget request (for FY2018), Congress has appropriated, on average, $104 million more in bilateral aid to Tunisia each year than the President requested. As part of its justification for requesting global FMF loan authority in FY2021, the Administration cited a "request from the Government of Tunisia for a $500 million FMF loan to procure U.S.-manufactured light attack aircraft for the Tunisian Armed Forces." 31 Congress did not enact FMF loan authority in prior years in response to previous Trump Administration requests.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

||

|

DA |

- |

- |

- |

- |

40.00 |

- |

|

|

|

60.00 |

89.00 |

79.00 |

85.00 |

45.00 |

31.50 |

|

|

|

65.00 |

95.00 |

65.00 |

85.00 |

85.00 |

40.00 |

|

|

|

2.25 |

2.13 |

2.21 |

2.22 |

2.30 |

2.30 |

|

|

|

12.00 |

13.00 |

13.00 |

13.00 |

13.00 |

8.05 |

|

|

|

2.60 |

6.10 |

6.10 |

6.10 |

6.10 |

2.00 |

|

|

|

141.85 |

205.23 |

165.31 |

191.32 |

191.40 |

83.85 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94 and accompanying conference report, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Notes: Under P.L. 116-94 (FY2020 omnibus), Congress provided an additional $50 million in prior-year ESF funds for Tunisia. Under P.L. 116-6 (FY2019 omnibus), Congress provided an additional $50 million in prior-year Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF) aid for Tunisia.

Lebanon32

The United States has sought to bolster forces that could help counter Syrian and Iranian influence in Lebanon through a variety of military and economic assistance programs. U.S. security assistance priorities reflect increased concern about the potential for Sunni jihadist groups such as the Islamic State to target Lebanon, as well as long-standing U.S. concerns about Hezbollah and preserving Israel's qualitative military edge (QME). U.S. economic aid to Lebanon seeks to promote democracy, stability, and economic growth, particularly in light of the challenges posed by the ongoing conflict in neighboring Syria. Congress places several certification requirements on U.S. assistance funds for Lebanon annually in an effort to prevent their misuse or the transfer of U.S. equipment to Hezbollah or other designated terrorists. Hezbollah's participation in the Syria conflict on behalf of the Asad government is presumed to have strengthened the group's military capabilities and has increased concern among some in Congress over the continuation of U.S. assistance to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF).

FMF has been one of the primary sources of U.S. funding for the LAF, along with the Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund (CTEF). According to the State Department, between FY2015 and FY2019, security assistance has averaged $224 million annually in combined State Department and Department of Defense military grant assistance.33 These funds have been used to procure, among other things, light attack helicopters, unmanned aerial vehicles, and night vision devices.

The United States has long provided relatively modest amounts of ESF to Lebanon for scholarships and USAID programs. Since the start of the Syrian civil war, U.S. programs have been aimed at increasing the capacity of the public sector to provide basic services to both refugees and Lebanese host communities, including reliable access to potable water, sanitation, and health services. U.S. programs have also aimed to increase the capacity of the public education system to cope with the refugee influx.

For FY2021, the President is requesting $133 million in total bilateral aid to Lebanon, which is 46% less than what Congress provided for Lebanon in FY2020. For the past three fiscal years, Congress has appropriated, on average, $113.5 million per year above the President's request.

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 actual |

FY2019 |

FY2020 enacted |

FY2021 |

||

|

|

110.00 |

110.00 |

117.00 |

112.50 |

112.50 |

62.20 |

|

|

|

85.90 |

80.00 |

105.00 |

105.00 |

105.00 |

50.00 |

|

|

|

2.80 |

2.65 |

3.12 |

2.97 |

2.97 |

3.00 |

|

|

|

10.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

6.20 |

|

|

|

4.76 |

5.76 |

10.82 |

11.82 |

11.82 |

11.76 |

|

|

|

213.46 |

208.41 |

245.94 |

242.29 |

242.29 |

133.16 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2017-FY2021), P.L. 116-94, and CRS calculations and rounding.

Regional Program Aid

In addition to assistance provided directly to certain countries, the United States provides aid to Middle Eastern countries through regional programs, including the following.

- Middle East Regional Partnership Initiative (MEPI). MEPI is an office within the Bureau for Near Eastern Affairs at the State Department that specifically supports political reform, women's and youth empowerment, quality education, and promoting economic opportunity in the Arab world. Since MEPI's inception in 2002, Congress has allocated it an estimated $1.1 billion in ESF. One of MEPI's contributions to U.S. democracy promotion in the Arab world has been to directly fund indigenous nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). MEPI's Local Grants Program awards grants to NGOs throughout the Middle East in order to build capacity for small organizations.34 However, in countries with legal restrictions prohibiting foreign funding of local NGOs, U.S. officials and grant recipients may weigh the potential risks of cooperation. Between 2011 and 2013, Egypt arrested and convicted local and foreign NGO specialists on election monitoring, political party training, and government transparency in Egypt.35

- Middle East Regional (MER). A USAID-managed program funded by ESF, MER supports programs that work in multiple countries on issues such as women's rights, public health, water scarcity, and education. For FY2021, the Administration is requesting $50 million in ESF funding for MER. In recent years, USAID has allocated $10 million to $15 million annually for MER.

- Near East Regional Democracy (NERD). A State Department-managed program funded through ESF, NERD promotes democracy and human rights in Iran (though there is no legal requirement to focus exclusively on Iran). NERD-funded training (e.g., internet freedom, legal aid) for Iranian activists takes place outside the country due to the clerical regime's resistance to opposition activities supported by foreign donors. For FY2021, the Administration has bundled its NERD request together with MEPI as part of an $84.5 million ESF request for what it calls "State NEA Regional." For FY2020, Appropriators specified $70 million in ESF for NERD ($55 million base allocation plus $15 million to the State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor or DRL) in Division G of the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying P.L. 116-94.

- Middle East Regional Cooperation (MERC). A USAID-managed program funded through ESF, MERC supports scientific cooperation between Israelis and Arabs. First established in an amendment to the Foreign Operations bill in 1979, MERC was designed to encourage cooperation between Egyptian and Israeli scientists. Today, MERC is an open-topic, peer-reviewed competitive grants program that funds joint Arab-Israeli research covering the water, agriculture, environment, and health sectors. For FY2021, the Administration is not requesting any ESF for MERC. Appropriators specified $5 million for MERC in FY2020 appropriations (Division G of the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying P.L. 116-94).

- Middle East Multilaterals (MEM). A small State Department-managed program funded through ESF, MEM supports initiatives aimed at promoting greater technical cooperation between Arab and Israeli parties, such as water scarcity, environmental protection, and renewable energy. For FY2021, the Administration is not requesting any ESF for MEM, and the last time the program was allocated funding was in FY2018 ($400,000).

- Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP). A State Department-led, interagency initiative funded through multiple foreign assistance accounts (PKO, NADR, INCLE, DA, and ESF), TSCTP supports programs aimed at improving the capacity of countries in North and West Africa to counter terrorism and prevent Islamist radicalization. Three North African countries —Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco—participate in TSCTP; Libya is also formally part of the partnership, but the majority of funding has been implemented in West Africa's Sahel region to date.

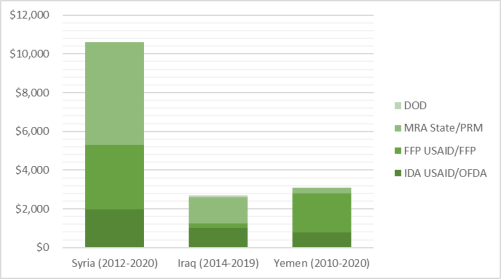

Funding for Complex Humanitarian Crises

For nearly a decade, the United States has continued to devote significant amounts of foreign assistance resources toward several major humanitarian crises stemming from ongoing conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere (see Figure 4). Since 2010, the United States has provided about $16.4 billion in humanitarian response funding to the Middle East.

- The United States is the largest donor of humanitarian assistance to the Syria crisis and since FY2012 has allocated more than $10.6 billion to meet humanitarian needs using existing funding from global humanitarian accounts and some reprogrammed funding.

- According to the United Nations, Yemen's humanitarian crisis is the worst in the world, with close to 80% of Yemen's population of nearly 30 million needing some form of assistance. The United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait are the largest donors to annual U.N. appeals for aid. Since 2011, the United States has provided over $3 billion in emergency humanitarian aid for Yemen. Most of these funds are provided through USAID's Office of Food for Peace to support the World Food Programme in Yemen.

- During the government of Iraq's confrontation with the Islamic State, the United States was also one of the largest donors of humanitarian assistance. Since 2014, it has provided more than $2.6 billion in humanitarian assistance for food, improved sanitation and hygiene, and assistance for displaced and vulnerable communities to rebuild their livelihoods.

The State Department and USAID provide this humanitarian assistance through implementing partners, including international aid organizations and nongovernmental organizations Humanitarian assistance is primarily managed by USAID's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), USAID's Office of Food for Peace (FFP), and the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) using "global accounts" (rather than bilateral), such as IDA, FFP, and MRA.

Foreign Aid Issues for Potential Consideration

Major Changes in U.S. Aid to the Palestinians36

|

U.S. Aid to the Palestinians Since 1950 Until the recent changes to U.S. law and policy, the United States provided aid to the Palestinians in several ways. Since 1950, the U.S. government had annually contributed to UNRWA to support Palestinian refugees. Since 1975, the United States also had provided bilateral economic aid for USAID programs in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, and these programs widely expanded in 1994 after the start of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Since Hamas forcibly took control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, the United States also consistently provided bilateral, nonlethal security assistance for West Bank-based PA security forces. At times, the executive branch and Congress took various measures to reduce, delay, or place conditions on this aid. Annual appropriations legislation has routinely contained (and still does) several conditions on direct and indirect aid to various Palestinian entities. |

Policy changes during the Trump Administration (see Chronology below), coupled with legislation passed by Congress, have halted various types of U.S. aid (see "U.S. Aid to the Palestinians Since 1950" Text Box) to the Palestinians. The Administration withheld FY2017 bilateral economic assistance, reprogramming it elsewhere, and ceased requesting bilateral economic assistance after Palestinian leadership broke off high-level political contacts to protest President Trump's December 2017 recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital. In January 2019, after Congress passed the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253), the Palestinian Authority (PA) ceased accepting any U.S. aid, including security assistance and legacy economic assistance from prior fiscal years. ATCA provided for a defendant's consent to U.S. federal court jurisdiction over the defendant for lawsuits related to international terrorism if the defendant accepted U.S. foreign aid from any of the three accounts from which U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians has traditionally flowed (ESF, INCLE, and NADR). The PA made the decision not to accept bilateral aid, most likely to avoid being subjected to U.S. jurisdiction in lawsuits filed by U.S. victims of Palestinian terrorism.

|

Date |

Event |

|

December 2017 |

President Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announced his intention to relocate the U.S. embassy there. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas announced at the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) conference in Istanbul, Turkey, that the United States had "disqualified itself from playing the role of mediator in the peace process." He then broke off diplomatic contacts with the United States in response to its new policy on Jerusalem. |

|

January 2018 |

President Trump said that the hundreds of millions of dollars of aid that Palestinians receive "is not going to them unless they sit down and negotiate peace." |

|

March 2018 |

Congress and the President enact the Taylor Force Act (Title X of P.L. 115-141), which suspended all economic assistance for the West Bank and Gaza that "directly benefits" the PA for so long as Palestinian entities continue to make welfare payments that are identified in the Act as incentivizing terrorism. |

|

August 2018 |

The State Department announced that the United States would not make further contributions to UNRWA. |

|

September 2018 |

The Administration notified Congress that it would reprogram at least $231.5 million of FY2017 bilateral economic aid initially allocated for the West Bank and Gaza. |

|

October 2018 |

President Trump signed the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 (ATCA, P.L. 115-253) into law. |

|

December 2018 |

Then-PA Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah wrote to Secretary of State Michael Pompeo that the PA would not accept aid that subjected it to U.S. federal court jurisdiction |

|

January 2019 |

U.S. bilateral aid to the Palestinians ended. |

|

December 2019 |

The Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019 is signed into law as part of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94. Congress appropriated $75 million in PA security assistance for the West Bank and $75 million in economic assistance for the West Bank and Gaza in P.L. 116-94. |

|

January 2020 |

The Trump Administration released its Middle East peace plan. |

Source: CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti and CRS Report R46274, The Palestinians and Amendments to the Anti-Terrorism Act: U.S. Aid and Personal Jurisdiction, by Jim Zanotti and Jennifer K. Elsea.

Some sources suggested that the Administration and Congress belatedly realized ATCA's possible impact,37 and began considering how to resume security assistance to the PA—and perhaps other types of aid to the Palestinian people—after the PA stopped accepting bilateral aid in 2019.38 In December 2019, Congress passed the Promoting Security and Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act of 2019, or PSJVTA as § 903 of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020, P.L. 116-94. PSJVTA changes the legal framework applicable to terrorism-related offenses by replacing the provisions in ATCA that triggered Palestinian consent to personal jurisdiction for accepting U.S. aid. However, because PSJVTA did include other possible triggers of consent to personal jurisdiction—based on actions that Palestinian entities might find difficult to stop for domestic political reasons—it is unclear whether the Palestinians will accept this "legislative fix" and resume accepting U.S. bilateral aid.39

Congress also appropriated $75 million in PA security assistance for the West Bank and $75 million in economic assistance in FY2020 (P.L. 116-94), with appropriators noting in the joint explanatory statement that "such funds shall be made available if the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act of 2018 is amended to allow for their obligation." It is unclear whether the executive branch will implement the aid provisions. The Trump Administration had previously suggested that restarting U.S. aid for Palestinians could depend on a resumption of PA/PLO diplomatic contacts with the Administration.40 Such a resumption of diplomacy may be unlikely in the current U.S.-Israel-Palestinian political climate,41 particularly following the January 2020 release of a U.S. peace plan that the PA/PLO strongly opposes and possible discussion of Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank.

The Administration's omission of any bilateral assistance—security or economic—for the West Bank and Gaza in its FY2021 budget request, along with its proposal in the request for a $200 million "Diplomatic Progress Fund" ($25 million in security assistance and $175 million in economic) to support future diplomatic efforts, may potentially convey some intent by the Administration to condition aid to Palestinians on PA/PLO political engagement with the U.S. peace plan.42 The Administration also had requested funds for a Diplomatic Progress Fund in FY2020, but Congress instead provided the $150 million in bilateral aid in P.L. 116-94.

|

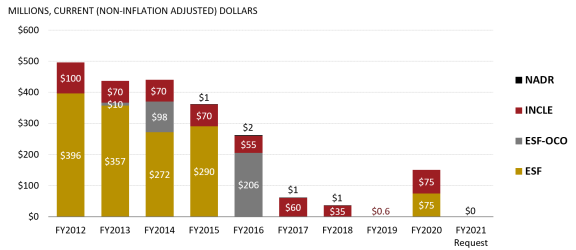

|

Sources: U.S. State Department and USAID, adapted by CRS. Notes: All amounts are approximate. Amounts stated for FY2020 reflect pending appropriation amounts from the H.R. 1865 joint explanatory statement. NADR = Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related Programs, INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement, ESF = Economic Support Fund, OCO = Overseas Contingency Operations. |

Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, some Members of Congress are concerned that the uncertainty surrounding the status of U.S. aid to the Palestinians may prevent humanitarian aid to combat the disease from reaching the Palestinian population. In late March 2020, several Senators sent a letter to Secretary of State Pompeo urging the Administration "to take every reasonable step to provide medicine, medical equipment and other necessary assistance to the West Bank and Gaza Strip (Palestinian territories) to prevent a humanitarian disaster."43 In April, the Administration announced that it would provide $5 million in International Disaster Assistance (IDA) to the West Bank as part of its global COVID-19 response. One media report stated that the $5 million in health assistance for hospitals in the West Bank does not "represent a change of policy regarding aid to the Palestinians, but is rather part of a larger decision to fight the spread of the pandemic across the Middle East, according to sources within the administration."44

Debate over Military Aid to Lebanon45

Since the United States began providing military assistance to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) following the 2006 summer war between Israel and Hezbollah, policymakers and foreign policy experts have debated the efficacy of such aid. U.S. military commanders have repeatedly testified before Congress that assistance to the LAF helps foster U.S.-Lebanese cooperation and strengthens the Lebanese government's capacity to counter terrorism.46 On the other hand, critics of such support have charged that U.S. aid to the LAF risks U.S. equipment falling into the hands of Hezbollah or other designated terrorists. They also contend that the LAF, even with U.S. aid, is unable or unwilling to enforce United Nations Security Council Resolution 1701 (passed after the 2006 war), which calls for the "disarmament of all armed groups in Lebanon." More recently, as Hezbollah has played a key role in supporting the Asad regime in Syria, opponents of U.S. aid to Lebanon assert that Hezbollah and the LAF have more closely coordinated militarily and politically along the Lebanese-Syrian border.47

In 2019, the Trump Administration withheld $105 million in FMF to the LAF as part of a policy review over the efficacy of its military assistance program to Lebanon.48 In 2019, lawmakers in the House and Senate also introduced the "Countering Hezbollah in Lebanon's Military Act of 2019," (S. 1886 and H.R. 3331) which would withhold 20% of U.S. military assistance to the LAF unless the President can certify that the LAF is taking measurable steps to limit Hezbollah's influence over the force.

According to various reports, both the State and Defense Departments opposed the hold on FMF, calling the LAF a stabilizing institution in Lebanon that has served as a U.S. partner in countering Sunni Muslim extremist groups there.49 On November 8, 2019, Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee Eliot Engel and Chairman of its Subcommittee on the Middle East, North Africa, and International Terrorism Ted Deutch wrote a letter to the Office of Management and Budget agreeing with previous expert testimony by former U.S. officials who praised the LAF's capabilities.50

In December 2019, the Administration lifted its hold on FMF to Lebanon (DOD aid to Lebanon had not been withheld). The policy debate coincided with mass protests throughout Lebanon, which forced the LAF to deploy in the streets to maintain order. In December 2019, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued its review on U.S. security assistance to Lebanon concluding that "The Departments of State and Defense reported progress in meeting security objectives in Lebanon, but gaps in performance information limit their ability to fully assess the results of security-related activities."51

In January 2020, Lebanon formed a new government, which drew international scrutiny for being composed entirely of parties allied with the March 8 political bloc (headed by the Christian Free Patriotic Movement, Hezbollah, and the Amal Movement). Nevertheless, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper remarked in February 2020 that "In terms of security assistance, we've committed a lot to the Lebanese Armed Forces and we will continue that commitment."52

Fiscal Pressures Mount in Iraq53

Years of war, corruption, and economic mismanagement have strained Iraq's economy and state finances, leading to widespread popular frustration toward the political system, and culminating in popular protests across central and southern Iraq. The 2019 national budget ran its largest ever one-year deficit, and in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and steep declines in world oil prices delivered two additional shocks to Iraq's already stretched fiscal position. Iraqi authorities have expressed confidence in their ability to withstand low oil prices for the short term. However, with approximately 30% of all Iraqi workers employed by the government, some observers express concern that sustained pressure on state finances and economic activity could lead to more intense street violence and unrest, and/or contribute to an Islamic State resurgence.54

Iraq's draft 2020 budget assumed an oil export price of $56 per barrel. According to one projection from mid-March 2020—when prices were less than half that level—Iraq would have been "likely to earn less than $3 billion per month, given its recent rate of exports—leaving a monthly deficit of more than $2 billion just to pay current expenditures."55 As of May 2020, it appears that without outside assistance, Iraq will need to draw on reserves (around $65 billion as of early 2020), cut salaries, and/or limit social spending to meet budget needs.

International financial institutions (IFIs), such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), could be one source of external financing for Iraq, but Iraq has not met reform targets set under its last round of agreements with the IMF. From 2016 to 2019, the IMF provided over $5 billion in loans to Iraq to help the country cope with lower oil prices and ensure debt sustainability. Iraq would likely face higher borrowing costs for new sovereign debt offerings, and obtaining commitments from Iraqi authorities as preconditions on further U.S. or IFI support may be complicated by Iraq's contested domestic politics and uncertainty over the future of U.S.-Iraq ties.

Secretary of State Michael Pompeo announced on April 7 that U.S. officials would engage Iraqi counterparts in a high-level strategic dialogue in June to address the future of the bilateral partnership, including U.S. assistance and the presence of U.S. forces. U.S. forces consolidated their presence to a reduced number of Iraqi facilities in March and April 2020, and the Administration has informed Congress of reductions in U.S. civilian personnel since 2019.

Stabilization in Areas Liberated from the Islamic State

As Congress considers the President's FY2021 budget request for MENA, Members have continued to discuss what the appropriate level of U.S. assistance should be to stabilize and reconstruct areas recaptured from the Islamic State group (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL). Recent U.S. intelligence estimates warn that an IS-fueled insurgent campaign has begun in Syria and Iraq, foresee billions of dollars in reconstruction costs in liberated areas, and suggest that a host of complex, interconnected political, social, and economic challenges may rise from the Islamic State's ashes. According to the International Crisis Group,

In the two years since defeating ISIS, the Iraqi government has made only minimal progress rebuilding post-ISIS areas and reviving their local economies…. There is no reason to assume local resentment will lead residents directly back to ISIS, particularly given their bitter recent experience with the group's rule. Still, both Iraqis and Iraq's foreign partners worry about what might happen if these areas remain ruined and economically depressed.56

Since FY2017, Congress has appropriated over $1 billion in aid from various accounts (ESF, INCLE, NADR, PKO, and FMF57) as part of a "Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF)" to help areas liberated or at risk from the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations.58 Among several conditions on RRF spending, lawmakers have repeatedly mandated in appropriations language that funds designated for the RRF "shall be made available to the maximum extent practicable on a cost-matching basis from sources other than the United States."

Over time, lawmakers have adjusted the RRF's authorities to ensure that assistance be made available for "vulnerable ethnic and religious minority communities affected by conflict." In addition, lawmakers have removed the geographic limitation (Iraq and Syria) on funds appropriated for RRF, and have specified either in bill text or accompanying explanatory statements that RRF funding be made available for Jordan, Tunisia, Yemen, Libya, Lebanon, for countries in East and West Africa, the Sahel, and the Lake Chad Basin region. Congress also has appropriated funding specifically to address war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity in Iraq and Syria in recent years, including through the designation of RRF-eligible funds.

|

|

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

|

ESF/ESDF |

95.00 |

209.00 |

28.00 |

100.00 |

135.00 |

|

FMF |

100.00 |

75.00 |

25.00 |

- |

- |

|

INCLE |

15.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

- |

- |

|

NADR |

- |

50.00 |

23.00 |

45.00 |

25.00 |

|

PKO |

25.00 |

80.00 |

40.00 |

- |

- |

|

Total |

235.00 |

439.00 |

141.00 |

145.00 |

160.00 |

Source: Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Congressional Budget Justifications (FY2018-FY2021), and CRS calculations and rounding.

Notes: FY2020 enacted makes available not less than $200m from ESF, INCLE, NADR, PKO and FMF accounts, of which $10m from ESF and INCLE are to be used for transitional justice programs.

For stabilization efforts in Iraq, USAID has used ESF and ESF-OCO (Overseas Contingency Operations) funds to contribute to the United Nations Development Program's Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS). To date, more than $396 million in U.S. stabilization aid has flowed to liberated areas of Iraq, largely through the FFS—which remains the main international conduit for post-IS stabilization assistance in liberated areas of Iraq. The Trump Administration also has directed U.S. contributions to the FFS to address the needs of vulnerable religious and ethnic minority communities in Ninewa Plain, western Ninewa, and communities displaced from those areas to other parts of northern Iraq.

As U.S. officials continue to seek greater Iraqi and international contributions to stabilization efforts in Iraq, the scale of what is needed to rebuild Iraq has far exceeded international efforts to date. In 2018, experts from the World Bank and the Iraqi government concluded that the country would need $45 billion to repair civilian infrastructure that had been damaged or destroyed since 2014.59 At the 2018 Kuwait International Conference for Reconstruction of Iraq, the Iraqi government requested $88 billion from the international community for rebuilding efforts – it received pledges of $30 billion. According to one United Nations official, as of late 2019, just over $1 billion in reconstruction pledges have been delivered from donors.60

Stabilization needs in Syria also are extensive—the conflict has entered its tenth year and analysts have estimated that the cost of conflict damage and lost economic activity could exceed $388 billion.61 The Trump Administration generally has supported stabilization programming in areas of Syria controlled by U.S.-backed Kurdish forces and liberated from the Islamic State, while seeking to prevent such aid from flowing to areas of Syria controlled by the government of Syrian President Bashar al Asad. However, in 2018 and 2019, the Administration sought to shift responsibility for the funding of stabilization activities to other coalition partners. In contrast to prior years, the Administration's FY2020 and FY2021 foreign assistance budget requests have sought no Syria-specific funding, but as noted above, the FY2021 request states that "ESDF funding in the RRF will allow the State Department and USAID to support efforts in places like Syria" and other countries. In late 2019, USAID reported that donor funds for stabilization activities in Syria were nearly depleted.62 In October 2019, the Trump Administration announced that it was releasing $50 million in stabilization funding for Syria to support civil society groups, ethnic and religious minorities affected by the conflict, the removal of explosive remnants, and the documentation of human rights abuses. These funds were notified to Congress in early 2020, and consist primarily of FY2019 ESF-OCO funds, with $14 million in RRF-designated funds from various accounts.

The Trump Administration has stated its intent not to contribute to the reconstruction of Asad-controlled areas of Syria absent a political settlement to the country's civil conflict, and to use U.S. diplomatic influence to discourage other international assistance to Asad-controlled Syria. Congress also has acted to restrict the availability of U.S. funds for assistance projects in Asad-held areas.63 In the absence of U.S. engagement, other actors such as Russia or China could conceivably provide additional assistance for reconstruction purposes, but may be unlikely to mobilize sufficient resources or adequately coordinate investments with other members of the international community to meet Syria's considerable needs. Predatory conditional assistance could also further indebt the Syrian government to these or other international actors and might strengthen strategic ties between Syria and third parties in ways inimical to U.S. interests. A lack of reconstruction, particularly of critical infrastructure, could delay the country's recovery and exacerbate the legacy effects of the conflict on the Syrian population, with negative implications for the country's security and stability.

Human Rights and Foreign Aid to MENA

In conducting diplomacy in the Middle East and providing foreign aid to friendly states, it has been an ongoing challenge for the United States to balance short-term national security interests with the promotion of democratic principles. At times, executive branch officials and some Members of Congress have judged that cooperation necessary to ensure stability and facilitate counterterrorism cooperation requires partnerships with governments that do not meet basic standards of democracy, good governance, or respect for human rights.

Nevertheless, successive Administrations and Congress also at times have used policy levers, such as conditional foreign aid, to demand changes in behavior from partner governments accused of either suppressing their own populations or committing human rights abuses in military operations. In some instances, policymakers have taken action intended to reinforce democratic principles in U.S.-MENA diplomacy and to comply with U.S. and international law, while preserving basic security cooperation.

Examples of provisions of U.S. law that limit the provision of U.S. foreign assistance in instances when a possible gross violation of human rights has occurred include, among others:

- The Foreign Assistance Act (FAA) of 1961, as amended, contains general provisions on the use of U.S.-supplied military equipment (e.g., Section 502B, Human Rights - 22 U.S.C. 2304).64 Section 502B(a)(2) of the FAA stipulates that, absent the exercise of a presidential waiver, "no security assistance may be provided to any country the government of which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights."

- The Arms Export Control Act (AECA), as amended, contains several general provisions and conditions for the export of U.S.-origin defense articles that may indirectly address human rights concerns.65 For example, Section 4 of the AECA (22 U.S.C. 2754) states that defense articles may be sold or leased for specific purposes only, including internal security, legitimate self-defense, and participation in collective measures requested by the United Nations or comparable organizations. Section 3(c)(1)(B) of the AECA (22 U.S.C. 2753(c)(1)(B)) prohibits the sale or delivery of U.S.-origin defense articles when either the President or Congress find that a recipient country has used such articles in substantial violation of an agreement with the United States governing their provision or "for a purpose not authorized" by Section 4 of the AECA or Section 502 of the FAA.

- The "Leahy Laws" Section 620M of the FAA (22 U.S.C. 2378d) and 10 U.S.C. 362 prohibit U.S. security assistance to a foreign security force unit when there is credible information that such unit has committed a gross violation of human rights.

In addition to the U.S. Code, annual appropriations legislation contains several general and MENA-specific provisions that restrict aid to human rights violators.66 Recent annual appropriations legislation conditioning U.S. aid to Egypt is one of the more prominent examples of how policymakers have attempted to leverage foreign aid as a tool to promote U.S. values abroad.

Section 7041(a) of P.L. 116-94 contains the most recent legislative language conditioning aid to Egypt. The Act includes a provision that withholds $300 million of FMF funds67 until the Secretary of State certifies that the Government of Egypt is taking effective steps to advance, among other things, democracy and human rights in Egypt.68 The Secretary of State may waive this certification requirement, though any waiver must be accompanied by a justification to the appropriations committees.

Members of Congress and the broader foreign policy community continue to debate the efficacy of using foreign aid as leverage to promote greater respect for human rights in the Middle East and elsewhere. After the January 2020 death of an American citizen incarcerated in Egypt,69 one report suggests that the State Department's Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs has raised the option of possibly cutting up to $300 million in foreign aid to Egypt.70 In 2017, the Trump Administration reduced FMF aid to Egypt by $65.7 million, citing "Egyptian inaction on a number of critical requests by the United States, including Egypt's ongoing relationship with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, lack of progress on the 2013 convictions of U.S. and Egyptian nongovernmental organization (NGO) workers, and the enactment of a restrictive NGO law that will likely complicate ongoing and future U.S. assistance to the country."71

FY2020 MENA Legislative Summary in P.L. 116-94

|

Country |

House |

Senate |

Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying H.R. 1865 |

|

Egypt |

The bill would provide $1.402 billion for assistance for Egypt, including up to $102.5 million in ESF of which not less than $35 million should be made available for higher education programs including not less than $15 million for scholarships, and up to $1.3 billion in FMF, provided that 20% of such funds shall be withheld from obligation until the Secretary of State certifies "that the Government of Egypt is taking the steps enumerated under this section in the report accompanying this Act." The Secretary of State may waive the certification requirement with respect to 95% of the amount withheld from obligation. The remaining 5% may only be made available for obligation if the Secretary of State determines "that the Government of Egypt has completed action to provide fair and commensurate compensation to American citizen April Corley for injuries suffered by Egyptian armed forces on September 13, 2015." The bill also includes authority for loan guarantees for Egypt. |

The bill would provide $1.438 billion for assistance for Egypt, including not less than $125 million in ESF, of which not less than $40 million should be made available for higher education programs, including not less than $15 million for scholarships, and not less than $1.3 billion in FMF, provided that $300 million of FMF funds shall be withheld from obligation until the Secretary of State certifies that the Government of Egypt is taking sustained and effective steps to, among other things, advance democracy and human rights in Egypt. In making the certification, the Committee recommends the submission of reports on the cases of American citizens detained in Egypt, Egypt's compliance with end-user monitoring agreements for the use of U.S. military equipment in the Sinai, and efforts by the Government of Egypt to compensate April Corley. The bill also includes authority for loan guarantees for Egypt. |

The Act provides not less than $125 million in ESF, of which not less than $40 million should be made available for higher education programs, including not less than $15 million for scholarships, and not less than $1.3 billion in FMF, provided that $300 million of FMF funds shall be withheld from obligation until the Secretary of State certifies that the Government of Egypt is taking sustained and effective steps to, among other things, advance democracy and human rights in Egypt, release political prisoners. The Act requires reports from the Secretary of State to congressional committees on efforts by the Government of Egypt to compensate April Corley and on the implementation of Egyptian Law 149/2019 and its impact on Egyptian and foreign NGOs. The Act also includes authority for loan guarantees and financing for the procurement of defense articles to Egypt. |

|

Iran |

Same as enacted bill text. |

Would make funds available under ESF for democracy programs, and for the semi-annual report required of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954. |

Funds appropriated under the Diplomatic Programs, ESF, and NADR accounts shall be made available 1) to support U.S. policy to prevent Iran from achieving the capability to produce or otherwise obtain a nuclear weapon; 2) support an expeditious response to any violation of UNSC resolutions; 3) to support the implementation, enforcement, and renewal of sanctions against Iran; and 4) for democracy programs in Iran. The Act also requires a semi-annual report required of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, and a report on sanctions. |

|

Iraq |

The bill does not specify a precise amount of aid, but would make funds available "for assistance for Iraq for economic, stabilization, and humanitarian programs... None of the funds appropriated or otherwise made available by this Act may be used by the Government of the United States to enter into a permanent basing rights agreement between the United States and Iraq." Report language notes that funding may be used for the Marla Ruzicka Iraqi War Victims Fund, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, and for programs to protect and assist religious and ethnic minority populations in Iraq. "The Committee directs not less than $50,000,000 of the funds provided in this Act for stabilization and recovery assistance be made available for assistance to support the safe return of displaced religious and ethnic minorities to their communities in Iraq." |

The bill would provide $453.6 million, including not less than $150 million in ESF, not less than $47 million in NADR, and not less than $250 million in FMF, for assistance for Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The Committee recommends not less than $7.5 million for the Marla Ruzicka Iraqi War Victims Fund, not less than $10 million for scholarships for students in Iraq, and a report assessing the independence and effectiveness of the judiciary of Iraq. |

The Act makes funds available under titles III and IV for bilateral economic and international security assistance, including in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and for the Marla Ruzicka Iraqi War Victims Fund ($7.5 million); stabilization assistance, humanitarian assistance, programs to protect religious and ethnic minority populations, and for scholarships ($10 million). The JES states that the Secretary of State "shall work with the Government of Iraq to ensure security forces reflect the ethno-sectarian makeup of the areas in which they operate...." The Act states that any change in the status of operations at the U.S. Consulate General in Basrah shall be subject to prior consultation with the appropriate congressional committees. None of the funds appropriated by this Act may be used to enter into a permanent basing rights agreement between the U.S. and Iraq. The Act also provides $40 million in NADR funding for conventional weapons destruction, makes funds available from the Relief and Recovery Fund for humanitarian demining in Iraq, and makes funds available for the Counterterrorism Partnership Funds for programs in areas affected by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. |

|

Israel |

The bill would provide $3.3 billion in FMF and $5 million in MRA for refugee resettlement. |

The bill would provide $3.3 billion in FMF and $5 million in MRA for refugee resettlement. The bill would make not less than $30 million available under ESF and DA to support reconciliation programs, including between Israelis and Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. |

The Act provides $3.3 billion in FMF and $5 million in MRA for refugee resettlement. The Act also makes not less than $30 million available under DA to support reconciliation programs, including between Israelis and Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. |

|

Jordan |

The bill would provide not less than $1.525 billion for assistance to Jordan, including not less than $745.1 million in ESF for budget support for the Government of Jordan and not less than $425 million in FMF. The bill also includes authority for loan guarantees for Jordan. |

The bill would provide not less than $1.65 billion for assistance to Jordan, including not less than $745.1 million for budget support, not less than $425 million in FMF, and not less than $125 million from ESF balances in prior acts. The Committee recommends the establishment of an enterprise fund for Jordan. The bill also authorizes loan guarantees for Jordan. |

The Act provides not less than $1.525 billion for assistance to Jordan, including not less than $745.1 million in ESF for budget support for the Government of Jordan, not less than $425 million in FMF, not less than $13.6 million in NADR and not less than $4 million in IMET. The Act makes available not less than $125 million ESF funds appropriated in prior Acts for budget support to the Government of Jordan and to increase electricity transmission to neighboring countries. The Act also includes authority for loan guarantees for Jordan. |

|

Lebanon |

The Committee recommends $56.2 million in ESF and $56.3 million in DA, of which $12 million is for scholarships. Bill language specifies that INCLE and FMF funds may be made available for the Lebanese Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) to address security and stability requirements in areas affected by the conflict in Syria. FMF funds may be used only to professionalize the LAF and to strengthen border security and combat terrorism. FMF funds may not be obligated for assistance for the LAF until the Secretary of State submits to the Committees on Appropriations a spend plan, including actions to be taken to ensure equipment provided to the LAF is only used for the intended purposes. Aid shall not be made available for the ISF or the LAF if these entities fall under control by a foreign terrorist organization. |

The bill would provide not less than $244 million in assistance to pursue the resolution of border disputes between Lebanon and Israel, including not less than $115 million in ESF, $10 million in INCLE, $11 million in NADR, $3 million in IMET, and not less than $105 million in FMF only for programs to professionalize the LAF, strengthen border security and combat terrorism, and implement U.N. Security Council Resolution 1701. The Committee recommends not less than $5 million for not-for-profit educational institutions in Lebanon and $12 million for scholarships for students in Lebanon. The Committee expects that no funds made available by the act will benefit or legitimize Hizballah or any other FTOs operating in Lebanon. |

The Act makes funds available under titles III and IV consistent with the prior fiscal year and specifies that INCLE and FMF funds may be made available for the Lebanese Internal Security Forces (ISF) and the LAF to address security and stability requirements in areas affected by the conflict in Syria. FMF funds may be used only to professionalize the LAF, to strengthen border security and combat terrorism, and to implement U.N. Security Resolution 1701. FMF funds may not be obligated for assistance for the LAF until the Secretary of State submits to the Committees on Appropriations a spend plan, including actions to be taken to ensure equipment provided to the LAF is only used for the intended purposes. Aid shall not be made available for the ISF or the LAF if these entities fall under control by a foreign terrorist organization. The Act also makes $12 million in ESF available for Lebanon scholarships. |

|

Libya |

The bill does not specify a precise amount of aid, but would make funds available for stabilization assistance for Libya, including border security, provided that the Secretary of State certifies that mechanisms are in place for monitoring, oversight, and control of such funds. Additionally, the bill specifies that no funds shall be made available for Libya by this Act unless the Secretary of State certifies that the Government of Libya is cooperating with U.S. efforts to bring to justice those responsible for the attack on U.S. personnel and facilities in Benghazi, Libya in September 2012. |

The bill would provide not less than $40 million ($27 million ESF, $11 million NADR, $2 million INCLE) for stabilization assistance and continues limitations on assistance similar to the prior fiscal year. |

The Act makes funds available for stabilization assistance for Libya, including support for a United Nations-facilitated political process and border security, provided that the Secretary of State certifies that mechanisms are in place for monitoring, oversight, and control of such funds. The agreement includes not less than $40 million under the Relief and Recovery Fund for stabilization assistance for Libya. |

|

Morocco and Western Sahara |

The bill does not specify a precise amount of aid, but would make funds available under the DA and ESF headings for assistance for the Western Sahara, provided that "not later than 90 days after enactment of this Act and prior to the obligation of such funds, the Secretary of State, in consultation with the USAID Administrator, shall consult with the Committees on Appropriations on the proposed uses of such funds." The bill also states that FMF "may only be used for the purposes requested in the Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Fiscal Year 2017." |