Introduction

Though North Korea has been a persistent U.S. foreign policy challenge for decades, during 2017 the situation evolved to become what many observers assess to be a potential direct security threat to the U.S. homeland. In July 2017, North Korea apparently successfully tested its first intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM). Some observers assert that North Korea has, with these tests, demonstrated a capability of reaching the continental United States,1 although others contend that these tests have not yet in actuality proven that the DPRK has achieved intercontinental ranges with its missiles.2 Regardless, these developments, combined with the possibility that the regime in Pyongyang has miniaturized a nuclear weapon, suggests that North Korea could now be only one technical step—mastering reentry vehicle technology—away from being able to credibly threaten the continental United States with a nuclear weapon.3 Some estimates reportedly maintain that North Korea may be able to do so by sometime in 2018, suggesting that the window of opportunity for eliminating these capabilities without possible nuclear retaliation to the continental United States is closing.4 Combined with the long-standing use of aggressive rhetoric toward the United States by successive Kim regimes, these events appear to have fundamentally altered U.S. perceptions of the threat the Kim Jong-un regime poses, and have escalated the standoff on the Korean Peninsula to levels that have arguably not been seen since at least 1994.5 In the coming months, Congress may opt to play a greater role in shaping U.S. policy regarding North Korea, including consideration of the implications of possible U.S. actions to address it.6

The United States has long signaled its preference for resolving the situation with diplomacy, and has used economic pressure, in the form of unilateral and multinational economic sanctions, to create opportunities for those diplomatic efforts. Various Trump Administration statements suggest that a mixture of economic pressure and diplomacy remain the preferred policy tools. To a greater degree than their predecessors, however, Trump Administration officials have publicly emphasized that "all options are on the table," including the use of military force, to contend with the threat North Korea may pose to the United States and its allies.7 Consistent with the policies of prior Administrations, Trump Administration officials have also stated that the goal of their increased pressure campaign toward North Korea is denuclearization—the removal of nuclear weapons from—the Korean Peninsula.8 If the Trump Administration chooses to pursue military options, key questions for Congress include whether, and how, to best employ the military to accomplish denuclearization, and whether using military force on its own or in combination with other tools might result in miscalculation on either side and lead to conflict escalation.

Intended or inadvertent, reengaging in military hostilities in any form with North Korea is a proposition that involves military and political risk. Any move by the United States, South Korea or North Korea could result in an unpredictable escalation of conflict and produce substantial casualty levels. A conflict itself, should it occur, would likely be significantly more complex and dangerous than any of the interventions the United States has undertaken since the end of the Cold War, including those in Iraq, Libya, and the Balkans. Some analysts contend, however, that the risk of allowing the Kim Jong-un regime to acquire a nuclear weapon capable of targeting the U.S. homeland is of even greater concern than the risks associated with the outbreak of war, especially given Pyongyang's long history of threats and aggressive action toward the United States and its allies and the regime's long-stated interest in unifying the Korean Peninsula on its terms. Some analysts assert that preemptive U.S. military action against North Korea should be taken when there is an "imminent launch" of a North Korean nuclear-armed ICBM aimed at the United States or its allies.9 Other analysts downplay the risk of North Korean nuclearization; few analysts believe that North Korea would launch an unprovoked attack on U.S. territory.10

Many students of the regional military balance contend that an overall advantage over North Korea rests with the United States and its ally, the Republic of Korea (or, ROK, commonly known as South Korea), and that U.S./ROK forces would likely prevail in any conflict within a matter of weeks.11 Those analyses, however, also generally assume that neither China nor Russia would become engaged in the conflict. Should China or Russia do so, the conflict would likely become significantly more complicated, costly, and lengthy.12 The toll of such a conflict could be immense, given that Seoul—with a population of approximately 23 million people, including American citizens—is within North Korean artillery deployed near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the two Koreas. Should the DPRK use the nuclear, chemical or biological weapons in its arsenal, according to some estimates casualty figures could number in the millions.13 Depending upon the nature of the conflict and the strategic objectives being advanced, U.S. military casualties could also be considerable.

As a result, Congress may consider whether to support increased U.S. military activities—possibly including combat operations—to denuclearize the Korean peninsula, or whether instead to support efforts to contain and deter North Korean aggression primarily through other means. Any option would carry with it considerable risk to the United States, the region, and global order. As Congress considers these issues, key strategic-level questions include, but are not limited to the following:

- Could the North Korean regime change its calculus, or collapse or otherwise transform, perhaps as a result of outside pressure, prior to its acquisition, or use, of credible nuclear-tipped ICBMs capable of holding targets in the continental United States at risk?

- What are the implications for U.S. relationships in the region if key allies are persuaded that the United States will no longer give the priority to regional security that it has thus far?

- What will be the cost implications, in terms of U.S. and allied financial resources, casualties, standing and reputation, should hostilities break out, and how would those costs affect the ability of the United States to advance other critical national security objectives in other theaters?

- How do the risks associated with U.S. military action against North Korea compare with the risks of adopting other strategies, such as deterring and containing North Korea?

- Would a nuclear-armed Kim regime behave in a manner consistent with other nuclear powers? What would a nuclear-armed North Korea mean for longer-term national security decisions the United States faces?

|

Other Related CRS Reports The Congressional Research Service has authored a number of reports examining various aspects of the North Korea issue, including options for using nonmilitary instruments to resolve the crisis, that may be of interest. These include the following: CRS Report R41259, North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]; CRS In Focus IF10472, North Korea's Nuclear and Ballistic Missile Programs, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] CRS Report R44950, Redeploying U.S. Nuclear Weapons to South Korea: Background and Implications in Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] CRS In Focus IF10165, South Korea: Background and U.S. Relations, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]; CRS In Focus IF10345, Possible U.S. Policy Approaches After North Korea's January 2016 Nuclear Test, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]; CRS Report R41438, North Korea: Legislative Basis for U.S. Economic Sanctions, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS Insight IN10734, North Korea's Long-Range Missile Test, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Insight IN10779, Nuclear Talks with North Korea?, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. For more information, CRS analysts can be contacted through the CRS.gov website, or at x[phone number scrubbed]. |

|

|

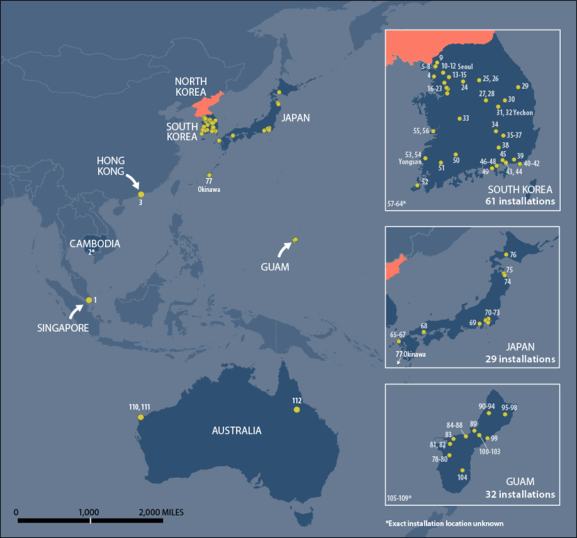

Sources: Map produced by CRS using data from ESRI, and the U.S. Department of State's Office of the Geographer. Note This map reflects official U.S. naming protocols. However, Koreans refer to the "Sea of Japan" as the "East Sea." They refer to the "Yellow Sea" as the "West Sea." |

Background

U.S. officials have been concerned about the threats North Korea poses to international order and regional alliances since Pyongyang's 1950 invasion of South Korea. The United Nations Security Council authorized a 16-nation Joint Command, of which the United States was a significant participant, to intervene on the Korean Peninsula to help repel North Korean forces. Shortly thereafter, when U.S. and allied forces pushed far into North Korean territory, China deployed its armed forces to assist the North. The parties eventually fought back to the 38th parallel that originally divided the peninsula following World War II.14 Counts of the dead and wounded vary: according to the U.S. Department of Defense, more than 33,000 U.S. troops were killed and over 100,000 were wounded during the three-year long Korean War;15 China lost upwards of 400,000 troops, with an additional 486,000 wounded;16 and North Korea's armed forces dead numbered around 215,000, with some 303,000 wounded.17 South Korea witnessed an estimated 138,000 armed forces and 374,000 civilians killed.18 Hostilities were formally suspended in 1953 with the signing of an armistice agreement rather than a peace treaty.

Over the subsequent decades, the United States and its regional allies have largely contained the military threats to U.S. interests in Northeast Asia posed by North Korea. The United States and its ally South Korea have deterred three generations of the ruling Kim dynasty in Pyongyang from launching large-scale military operations. The U.S. security commitment to, and relationship with, the Republic of Korea has helped South Korea to emerge as one of the world's largest industrialized countries and, since the late 1980s, a flourishing democracy.19 South Korea today is one of the United States' most important economic and diplomatic partners in East Asia and globally. With respect to the Korean Peninsula itself, two key components of U.S. policy have been the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty, along with the presence of some 28,500 U.S. troops in South Korea.20 Congress has supported the overall U.S. security approach to Northeast Asia, with the Senate approving defense treaties (and their revisions) with South Korea and Japan, and Congress providing funding for and oversight of the forward deployment of U.S. troops in both countries.

U.S./ROK efforts, however, along with those of other countries, have to date failed to compel the DPRK to abandon its nuclear weapons and ICBM programs. Since Pyongyang began undertaking its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) acquisition programs in earnest in the 1980s, the United States and the international community writ large have employed a range of tools, including diplomacy, sanctions, strengthening of the capabilities of U.S. political and military alliances, and attempts to convince China to increase pressure on the DPRK to change its behavior.21 Around 90% of North Korea's trade is with China, which arguably gives Beijing significant leverage over Pyongyang. Some argue that these efforts have slowed but not stopped North Korea's drive toward developing a nuclear ICBM capability.22

|

Coercion of State Behavior: Deterrence vs. Compellence When seeking to influence the behavior of states through the threat of inflicting pain or harm, at least two separate but related strategies can be employed: deterrence and compellence. Deterrence is generally applied to contexts wherein the objective is to prevent a state from undertaking a given particular action, such as initiating hostilities. Compellence, by contrast, refers to the act of trying to reverse an aggressive move that has been made, for example, returning territory that has already been annexed. For clarity, this report uses "deterrence" to describe strategies to prevent North Korea from initiating, or escalating, hostilities. Because U.S. leaders are seeking to convince Kim Jong-un to denuclearize, this report refers to those proliferation reversal strategies as "compellence." It is therefore possible to say that the United States has thus far deterred Pyongyang from initiating hostilities on the Korean Peninsula, but failed to compel it to abandon its nuclear weapons and ICBM programs. Sources: Schelling, Thomas C. Arms and Influence: With a New Preface and Afterword. Yale University Press, 2008; Freedman, Lawrence, ed. Strategic coercion: Concepts and cases. Oxford University Press, 1998. |

Economic and Diplomatic Efforts to Compel Denuclearization23

The Trump Administration, as the Obama Administration before it, places significant emphasis on expanding economic and diplomatic sanctions on North Korea and third-party entities that deal with North Korea. At the U.N. Security Council, the United States led efforts to pass eight sanctions resolutions, including the most recent, Resolution 2375, which was adopted in September 2017.24 For its part, Congress enacted the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016 (NKSPEA, P.L. 114-122; signed into law by President Obama in February 2016) and the Korean Interdiction and Modernization of Sanctions Act (KIMS Act, title III of P.L. 115-44; signed into law by President Trump in August 2017) to strengthen actions already taken by the executive branch to implement sanctions required by the Security Council and to expand those economic activities in which North Korea engages that could be subject to penalties—including trade and transactions with third countries (secondary sanctions). Further, since the George H.W. Bush Administration, the United States has imposed unilateral measures against North Korean entities, and entities in third countries, found to have been instrumental in North Korea's WMD programs.25 To implement the NKSPEA and KIMS Acts, the United States has also imposed economic sanctions on entities in China and Russia for activities that allegedly provide revenue to the North Korean government, provide the means to evade sanctions, or boost the regime's ability to advance its WMD capabilities. The United States also has worked to strengthen the military capabilities of South Korea and Japan.

Two key diplomatic efforts have aimed to induce North Korea to abandon its nuclear weapons program: the Agreed Framework (1994-2002) and the Six-Party Talks (2005-2009). The Agreed Framework between the United States and North Korea followed a ratcheting up of tensions that nearly led to a U.S. military strike. The Six-Party Talks, which involved the DPRK, China, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States, ran from 2003 to 2009, a period that included the first North Korean nuclear test in 2006. During both sets of negotiations, in exchange for specific economic and diplomatic gains, North Korea committed to eventual denuclearization, froze nuclear material production, and partially dismantled key facilities. Since withdrawing from the Six-Party Talks in 2009, North Korea has not agreed to return to its past denuclearization pledges.26 Subsequently, the United States has primarily concentrated its diplomatic efforts on convincing other nations to increase economic pressure to implement U.N. Security Council resolutions more fully.

|

Text of the Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea, October 1, 1953 The Parties to this Treaty, Reaffirming their desire to live in peace with all peoples and an governments, and desiring to strengthen the fabric of peace in the Pacific area, Desiring to declare publicly and formally their common determination to defend themselves against external armed attack so that no potential aggressor could be under the illusion that either of them stands alone in the Pacific area, Desiring further to strengthen their efforts for collective defense for the preservation of peace and security pending the development of a more comprehensive and effective system of regional security in the Pacific area, Have agreed as follows: The Parties undertake to settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations, or obligations assumed by any Party toward the United Nations. The Parties will consult together whenever, in the opinion of either of them, the political independence or security of either of the Parties is threatened by external armed attack. Separately and jointly, by self help and mutual aid, the Parties will maintain and develop appropriate means to deter armed attack and will take suitable measures in consultation and agreement to implement this Treaty and to further its purposes. Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific area on either of the Parties in territories now under their respective administrative control, or hereafter recognized by one of the Parties as lawfully brought under the administrative control of the other, would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes. The Republic of Korea grants, and the United States of America accepts, the right to dispose United States land, air and sea forces in and about the territory of the Republic of Korea as determined by mutual agreement. This Treaty shall be ratified by the United States of America and the Republic of Korea in accordance with their respective constitutional processes and will come into force when instruments of ratification thereof have been exchanged by them at Washington. This Treaty shall remain in force indefinitely. Either Party may terminate it one year after notice has been given to the other Party. IN WITNESS WHEREOF the undersigned Plenipotentiaries have signed this Treaty. DONE in duplicate at Washington, in the English and Korean languages, this first day of October 1953. UNDERSTANDING OF THE UNITED STATES [The United States Senate gave its advice and consent to the ratification of the treaty subject to the following understanding:] It is the understanding of the United States that neither party is obligated, under Article III of the above Treaty, to come to the aid of the other except in case of an external armed attack against such party; nor shall anything in the present Treaty be construed as requiring the United States to give assistance to Korea except in the event of an armed attack against territory which has been recognized by the United States as lawfully brought under the administrative control of the Republic of Korea. |

North Korea's Objectives

North Korea watchers argue that the ruling elite's fundamental priority is the survival of the Kim regime. For this reason, few analysts believe that North Korea would launch an unprovoked attack on U.S. territory or U.S. overseas bases; the consequences for doing so could include a possible overwhelming U.S. military response that could result in the end of the Kim Jong-un regime, and possibly the end of the DPRK as a sovereign state.27 The National Intelligence Manager for East Asia responsible for integrating the intelligence community's analysis said in a June speech that

We believe North Korea's strategic objective is the development of a credible nuclear deterrent. Kim Jong Un is committed to development of a long range nuclear armed missile capable of posing a direct threat to the continental United States to complement his existing ability to threaten the region. Kim views nuclear weapons as a key component of regime survival and a deterrent against outside threats. Kim probably judges that once he can strike the U.S. mainland, he can deter attacks on his regime and perhaps coerce Washington into policy decisions that benefit Pyongyang and upset regional alliances—possibly even to attempt to press for the removal of U.S. forces from the peninsula.28

North Korea has itself repeatedly emphasized the role of its nuclear weapons as an added deterrent to attack by the United States and/or South Korea. On October 20, 2017, North Korean Foreign Ministry official Choe Son Hui reiterated her government's past statements that its nuclear arsenal is meant to deter attack from the United States and that keeping its weapons is, "a matter of life and death for us."29 She also said that "the current situation deepens our understanding that we need nuclear weapons to repel a potential attack."30 Under Kim Jong Un, North Korea pursues an official policy of byungjin—simultaneous development of its nuclear weapons and its economy. On April 1, 2013, North Korea's party congress adopted the "Law on Consolidating Position of Nuclear Weapons State." The official media (KCNA) summarized the law as saying that nuclear weapons "serve the purpose of deterring and repelling the aggression and attack of the enemy against the DPRK and dealing deadly retaliatory blows at the strongholds of aggression until the world is denuclearized."31

Many analysts are concerned that North Korea could launch an attack first, even with nuclear-armed missiles, if it perceived a U.S. attack as imminent.32 These voices emphasize the need for careful U.S. rhetoric and confidence-building measures to avoid miscalculation.33 The Director of National Intelligence said in early 2012 that "we also assess, albeit with low confidence, Pyongyang probably would not attempt to use nuclear weapons against US forces or territory, unless it perceived its regime to be on the verge of military defeat and risked an irretrievable loss of control."34

Possessing nuclear weapons and long-range missile capability could also help the Kim government achieve a number of additional long-standing objectives. In May 2017 testimony, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats repeated the intelligence community's longstanding analysis that, "Pyongyang's nuclear capabilities are intended for deterrence, international prestige, and coercive diplomacy."35 Accordingly, Pyongyang may also see the acquisition of a nuclear-tipped ICBM capability as a way to increase its freedom of action, in the belief that the United States will be more constrained if North Korea can credibly threaten U.S. territories. The DPRK may believe that by acquiring nuclear-tipped ICBM capability, and thereby deterring the United States, it might have a greater chance of achieving its ultimate goal of reunifying the Korean Peninsula.36 Important steps in this process would include weakening the credibility of the U.S. commitment to defend South Korea and persuading the United States to remove sanctions and withdraw its troops from the Korean Peninsula.37 North Korea may also see recognition as a nuclear weapons state as a way to cement its legitimacy, both with its own populace and with the international community.38

U.S. Goals and Military Options

Sanctions, diplomacy, interdiction, and military capacity-building efforts have arguably slowed—for instance, through raising the costs of procuring materials—although not halted, the advance of North Korea's WMD programs. As multinational sanctions have gained momentum during the past several years, however, DPRK progress in its missile programs has also significantly accelerated.39 As a result of this progress, the Trump Administration appears to have raised the issue of North Korea's nuclear and missile programs to a top U.S. foreign and national security policy priority. Describing its policy as "maximum pressure," or "strategic accountability," the Administration has adopted an approach of increasing pressure on Pyongyang in an effort to convince the North Korean regime "to de-escalate and return to the path of dialogue."40 41 In August 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis outlined the U.S. policy objective and parameters for the Korean Peninsula:

The object of our peaceful pressure campaign is the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. The U.S. has no interest in regime change or accelerated reunification of Korea. We do not seek an excuse to garrison U.S. troops north of the Demilitarized Zone. We have no desire to inflict harm on the long-suffering North Korean people, who are distinct from the hostile regime in Pyongyang.42

In their public remarks, Trump Administration officials have emphasized that, while diplomacy and pressure will continue, a full range of military options could be employed to resolve the crisis. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford, for example, stated at the Aspen Security Forum in July 2017 that "it is not unimaginable to have military options to respond to North Korean nuclear capability. What's unimaginable to me is allowing a capability that would allow a nuclear weapon to land in Denver, Colorado. That's unimaginable to me. So my job will be to develop military options to make sure that doesn't happen."43

A key factor driving the Administration's actions and statements appears to be the assessment that sometime in 2018, North Korea is likely to acquire the capability of reaching the continental United States with a nuclear-tipped ICBM.44 This assessment implies that the timeframe for conducting military action without the risk of a North Korean nuclear attack against U.S. territory is narrowing. Such an assessment may increase the urgency of efforts to restart multilateral diplomatic efforts with North Korea, efforts that some maintain could be strengthened and accelerated if both North Korea and China believe that a U.S. military strike on the Korean Peninsula is becoming more likely.45

|

Possible Alternative Strategies Achieving the denuclearization of North Korea has been the official policy of the past four U.S. Administrations, and now that of the Trump Administration. Some now hold the view, however, that this approach is no longer feasible, in large measure due to the belief that the DPRK is unlikely to denuclearize voluntarily, and that the United States might instead recalibrate its policy to tacitly acknowledge that North Korea is a nuclear power and pursue other strategic objectives. These possible alternative strategies—each of which entails its own degree of risk—include the following:

|

Risk of Proliferation

In addition to possible threats to the continental United States, allies, and U.S. armed forces in the region, concerns persist that should the goal of denuclearization remain unaccomplished, North Korea might continue to proliferate its missile and nuclear technology for a variety of reasons, including financial profit by selling materials and information to state and non-state actors, joint exchange of data to develop its own systems with other states (Iran and Syria, most notably), or as part of a general provocative trend.49 DNI Dan Coats testified before Congress in May 2017 that "North Korea's export of ballistic missiles and associated materials to several countries, including Iran and Syria, and its assistance to Syria's construction of a nuclear reactor, destroyed in 2007, illustrate its willingness to proliferate dangerous technologies."50 In the wake of an earlier set of sanctions, former DNI Dennis Blair said in March 2016 that North Korea had "more motivation to increase their supply of hard currency any way they can," and selling nuclear materials was "certainly a possibility that has occurred to them."51

Efficacy of the Use of Force

Some contend that the military is an inappropriate instrument for resolving the standoff between the DPRK and the international community.52 They argue, for example, that even the threat of military force actually strengthens the Kim regime domestically, as it feeds the DPRK narrative that it must be vigilant against an aggressive United States. These observers contend that, instead, the United States should focus its efforts on influence operations, in particular, to shape the perceptions of the Kim regime's mid-level leaders and the North Korean population.53 Doing so might, in turn, eventually foster the collapse of the Kim regime itself and possibly create a window for denuclearization of North Korea. Others, however, maintain that these kinds of influence operations are unlikely to affect North Korean society in a manner that might result in regime degradation or collapse.54

In addition, some observers argue that although denuclearization may be a long-term strategic goal of the United States, achieving this goal in the short term may be difficult, particularly due to the high risk of military escalation. Therefore, they maintain, other tactics, such as deterrence and containment, may be more appropriate than a preventive military strike. In addition, some see military pressure as well as sanctions as a way to raise the costs for North Korea of continuing on its current nuclear and missile development path, thereby persuading the DPRK to eventually agree to a halt or reversal in these programs.55

|

Different Perceptions of the North Korean Military Threat Terms often used by scholars and practitioners to describe the North Korean regime include mercurial, dictatorial, belligerent, bellicose, rogue, and even state-run criminal enterprise. Many Americans therefore wonder why some other countries, including South Korea, China, and Russia, appear more willing to de facto tolerate nuclear weapons—and the capability to deliver them across continents—in the possession of a state with those characteristics. Perceptions of threat are likely driven by two key factors: perception of capability and intent. While few doubt that North Korea has built capabilities that could hold targets in the region at risk, perceptions tend to differ regarding the DPRK's intent. China is arguably North Korea's closest partner. China and North Korea are, at least nominally, allies; approximately 90% of North Korea's trade is believed to be with China. As a result, China does not appear to be concerned that the DPRK is currently targeting or threatening Chinese territory or interests, although some Chinese analysts fear that if China continues increasing pressure on North Korea, the DPRK could come to target China. Instead, Chinese leaders appear more concerned that severe pressure on North Korea could destabilize the Korean Peninsula, possibly spreading instability into China or prompting Beijing to deploy the People's Liberation Army over its 900-mile long border into North Korea to manage the situation. Beijing is also thought to fear the prospect of a massive flow of North Korean refugees into China and the loss of North Korea as a "buffer" against the U.S.-allied Republic of Korea should the Kim regime collapse. Even so, China has condemned North Korea's weapons programs and has voted for all eight UNSC Resolutions sanctioning Pyongyang, albeit after weakening their requirements and terms.56 Russia is now believed to be North Korea's second-largest trading partner, although its trade with North Korea is dwarfed by China's. Russia is generally estimated to have been North Korea's third-largest trading partner from 2010-2015. Like China, Russia has supported all eight UNSC resolutions sanctioning North Korea's WMD programs, after working with China to soften some aspects.57 Russia has a border with North Korea. Yet Moscow is nearly 4,000 miles from the Korean Peninsula, a distance that may reduce Russia's sense of vulnerability to instability in that region. Although the South Korean government and populace have become increasingly alarmed by North Korea's expanding nuclear capabilities, and tend to agree with the United States about the DPRK's capability and intent, South Korea—perhaps by necessity—tends to differ from the United States regarding what can be done about the problem. For decades, South Korea has lived with the threat of massive devastation from North Korean conventional forces—specifically the DPRK's long-range artillery. North Korean nuclear weapons are therefore not quite as consequential a development to South Koreans as they are to other actors in the region. In addition, whereas North Korean nuclear-armed ICBMs would pose a danger to the United States, shorter-range nuclear-tipped missiles pose a threat to the very existence of South Korea because of the two Koreas' proximity. In addition, some South Koreans have family members living in the North and see the peninsula as one divided Korean nation. For those reasons, most South Koreans oppose the idea of a military strike against North Korea, as doing so could easily lead to unpredictable conflict escalation, including the destruction of Seoul through either conventional or unconventional means, or both. By contrast, the fact that the United States has technically been in conflict with North Korea since 1950, in combination with North Korea's aggressive statements and provocative actions over the years, means that many leaders in Washington, DC, believe that North Korea has long had the intent to threaten the American homeland, but may soon have the capability to do so with credible nuclear missiles. |

Overview of the Peninsular Military Capabilities58

Understanding the military dimensions of the current standoff, and the relative feasibility of different options to use force to resolve the crisis, requires an appreciation of the extant military capabilities on the Korean Peninsula. Estimating the military balance in the region, however, and how military forces might be employed during wartime, requires accounting for a variety of variables; therefore, such estimation is an inherently imprecise endeavor. As an overall approach to designing its military, the DPRK has emphasized quantity over quality, and has committed considerable resources to developing asymmetric capabilities such as weapons of mass destruction and Special Operations Forces. The Republic of Korea, by contrast, has emphasized quality over quantity and maintains a highly skilled, well-trained, and capable conventional force. In terms of cyber capabilities, the DPRK has been conducting increasingly aggressive cyber operations against the heavily networked ROK and other targets. Although the DPRK has limited internet connectivity itself, components of its weapons programs may be vulnerable to cyberattacks.59

Appendix A analyzes in detail the capabilities of the key actors presently on the Korean Peninsula.

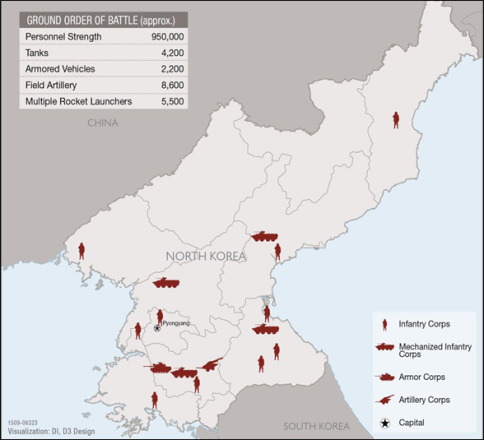

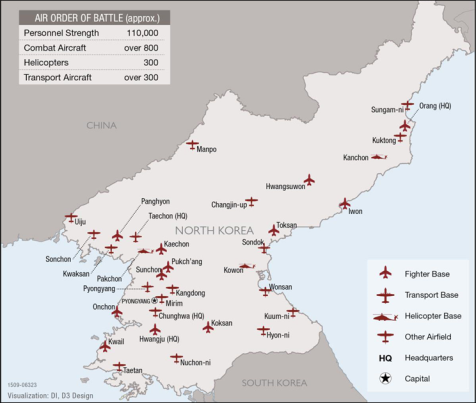

DPRK Capabilities

The Korean People's Army (KPA)—a large, ground force-centric organization comprising ground, air, naval, missile, and special operations forces (SOF)—has over 1 million soldiers in its ranks.60 Although it is the fourth largest military in the world, it has some significant deficiencies, particularly with respect to training and aging (if not archaic) equipment.61 A number of analysts attribute that degradation of capability to food and fuel shortages, economic hardship, and an inability to replace aging equipment, because of international arms markets being closed to North Korea due to sanctions and international nonproliferation regimes, among other factors.62

To compensate, particularly in recent years, the DPRK appears to have heavily invested in asymmetric capabilities, both on the "high" (for example, weapons of mass destruction) and "low" (for example, SOF) ends of the capability spectrum. The presence of chemical and biological weapons that could reach South Korea and parts of Japan has long been confirmed;63 some observers believe that those systems would be immediately employed by the DPRK regime in the event of a conflict.64 Hardened facilities, particularly in forward locations, are thought to protect artillery and supplies and WMD capabilities, including chemical munitions. The DPRK also has missiles believed capable of reaching Guam, other U.S. bases, and allies in the immediate region, including Japan.65 With respect to the "low" end of the capability spectrum, estimates vary on the size of DPRK SOF, although U.S. and ROK intelligence and military sources reportedly maintain that its end strength may be as high as 200,000, including 140,000 light infantry and 60,000 in the 11th Storm Corps.66

These "high" and "low" capabilities are in addition to the considerable DPRK inventory of long-range rockets, artillery, short-range ballistic missiles, and chemical weaponry aimed at targets in the Republic of Korea.67 U.S. military facilities and the Seoul region, the latter with a population of approximately 23 million, are within range of significant conventional artillery capabilities situated along the DMZ. Reports indicate that the DPRK has enhanced the mobility of its missile launchers and at least some of its artillery batteries, arguably making them more difficult to target.68 Reports also suggest that the DPRK has hardened many of its key facilities through an extensive network of underground tunnels, a further challenge to fully identifying the DPRK's military capabilities.69

ROK Capabilities

While the DPRK has sought to balance its conventional deficiencies with asymmetric capabilities, the Republic of Korea has steadily improved its conventional forces, through increasing their lethality with improvements in command, control and communications and advanced technology, as well as through incorporating battlefield lessons from its experience in Operation Iraqi Freedom.70 Still, the ROK's active duty military is approximately half the size of the DPRK's, leading some analysts to conclude that South Korea may not be able to amass enough force to meet a challenge from the north. ROK leaders have decided not to acquire nuclear weapons, but rely instead on U.S. security assurances (in particular, the U.S. extended deterrent nuclear umbrella).71 Toward that end, some in South Korea, in particular, the Liberty Korea Party, have called for the redeployment of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in order to send a powerful deterrent message to the North and demonstrate a strong commitment to the South.72 ROK became a signatory to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in 1975 and is a state party to other related treaties and nonproliferation regimes, including those curtailing chemical and biological weapons and missile proliferation.

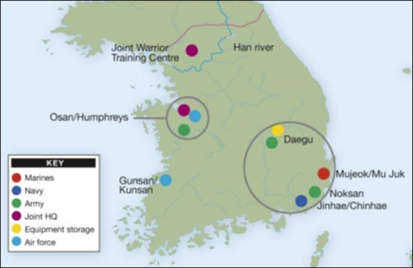

U.S. Posture

There are 28,500 U.S. troops and their families currently stationed in the Republic of Korea, primarily playing a deterrent role by acting as a tripwire in case of DPRK hostilities south of the DMZ.73 U.S. armed forces train with their ROK partners to better prepare them to participate in coalition operations. The United States reportedly also provides the ROK with several key enablers, including military intelligence.74 Since 2004, the U.S. Air Force has increased its presence in ROK through the regular rotation into South Korea of advanced strike aircraft. These rotations do not constitute a permanent presence, but the aircraft often remain in South Korea for weeks and sometimes months for training.75 Due to these conventional capabilities, as well as the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty, the United States has extended its deterrent umbrella to South Korea, including nuclear deterrence.

Under current U.S./ROK operational plans (OPLANS), the South Korean government has publicly stated that United States would deploy units to reinforce the ROK in the event of military hostilities. In the event of wartime, and depending on those circumstances, official ROK sources note that up to 690,000 additional U.S. forces could be called upon to reinforce U.S./ROK positions, along with 160 naval vessels and 2,000 aircraft.76

|

U.N. Security Council Resolutions and the Korean War Armistice Agreement The current North Korea crisis involves relatively recent developments in the nuclear weapons program of North Korea and an emerging national security threat to the United States that a number of analysts argue requires new action by the international community. Several existing measures already govern, at least in part, the situation on the Korean Peninsula and any military conflict that might take place there. The U.N. Security Council adopted three resolutions77 in response to the 1950 invasion of South Korea by North Korea; U.N. unified command and the armed forces of North Korea and China, signed an armistice agreement78 ceasing hostilities on the peninsula in 1953. It is not certain, however, whether these documents govern the current North Korea situation in any way. Although the U.N. Security Council resolutions called for an immediate cessation of hostilities, established authority to use military force to stop the North Korean invasion of South Korea, and called for establishment of a unified U.N. military command headed by the United States, they did so to ensure that North Korean forces withdrew north of the 38th parallel. Upon cessation of hostilities and the withdrawal of North Korean and Chinese forces from South Korea across the demilitarized zone straddling the 38th parallel, the objectives of the U.N. Security Council resolutions authorizing the use of military force were met. It can be argued, therefore, that the resolutions would no longer authorize any use of military force against North Korea unless North Korean forces again crossed into South Korea. The armistice agreement represented a joint decision by the U.N. command, North Korea, and China to cease hostilities, and it has endured as the framework upon which peace on the Korean Peninsula has been based since 1953. Yet, numerous violations of the armistice agreement have occurred. North Korea has used military force against South Korean territory on a number of occasions. In addition, the armistice agreement requires that the parties to the conflict refrain from introducing new weapons into the Korean Peninsula, something that both sides have done on multiple occasions since the armistice was signed. North Korea also has declared several times its determination that the armistice agreement is no longer valid, and that it was withdrawing from the agreement. Thus, while the United Nations has stated that the armistice agreement still serves as the basis and starting point for permanent peace on the Korean Peninsula, it may be difficult to argue that it still serves as the controlling source of international law and authority with regard to all uses of military force. |

Key Risks

As one observer notes, due to the complexity of the situation and the different military capabilities of all sides, predictions regarding how hostilities might unfold on the Korean Peninsula is comparable to describing a "very complex game of three-dimensional chess in terms of tic-tac-toe."79 Accordingly, rather than analyzing possible DPRK counter-moves or possible military campaign trajectories, this section briefly discusses some key risk considerations related to possible military action on the Korean Peninsula.

North Korean Responses

The Kim regime could respond to any kind of U.S./ROK military activity through a variety of conventional and unconventional means, any use of which could escalate into a full-scale war on the Korean Peninsula. Detailing specific possible responses is difficult, however, given the scarcity of relevant available literature. In the first instance, despite noted deficiencies in its overall conventional force structure, many observers expect the DPRK would employ its conventional artillery toward targets in South Korea and inflict considerable damage upon Seoul (as detailed in the next section).

In terms of unconventional responses, the DPRK might employ its highly trained SOF to sabotage U.S./ROK targets south of the DMZ. The DPRK might also employ weapons of mass destruction during a conflict with the U.S./ROK. A possibility also exists that a conflict with DPRK could escalate into nuclear warfare; the result of which could be radioactive contamination could affect all states in the immediate region, including China, Japan, and South Korea. As a consequence in this possible contingency, U.S. forces would likely be required to operate in WMD-contaminated zones, and the Korean Peninsula itself could face enormous devastation and loss of life. North Korea also could launch a cyberattack against the United States, South Korea, or other targets.80 Further, some observers contend that North Korea may already have the capability to launch a nuclear attack against the continental United States, possibly delivered covertly by smuggling, or even through using container ships as a means of delivery.81

Mass Casualties

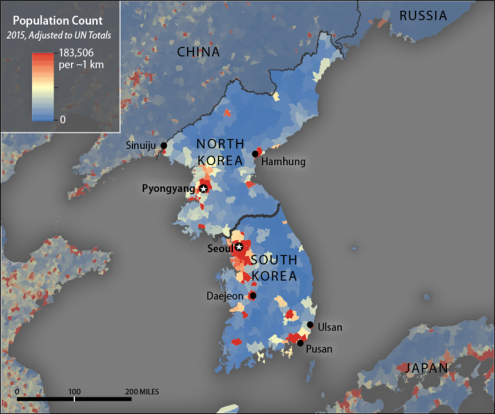

Figure 2 depicts population density on the Korean Peninsula. It suggests that an escalation of a military conflict on the peninsula could affect upwards of 25 million people on either side of the border, including at least 100,000 U.S. citizens (some estimates range as high as 500,000).82 Even if the DPRK uses only its conventional munitions (which most analysts believe would be unlikely given North Korea's arsenal of WMD capabilities), some estimates range from between 30,000 and 300,000 dead in the first days of fighting, given that DPRK artillery is thought by some to be capable of firing 10,000 rounds per minute at Seoul.83 Casualties would likely be significantly higher should nonconventional munitions or capabilities be used. This wide range of casualty estimates is due to the fact that a wide variety of variables (including campaign length, weaponry used, the effectiveness of noncombatant evacuation operations, whether China or Russia might become militarily involved and so on) would likely have significant bearing on the actual numbers of casualties on all sides. Responding to congressional inquiries, the Joint Staff released a letter on October 27, 2017, noting the difficulty of accounting for these variables when projecting civilian casualties in the event of a resumption of hostilities on the Korean peninsula.84 Still, as one observer states

Estimates are that hundreds of thousands of South Koreans would die in the first few hours of combat—from artillery, from rockets, from short range missiles—and if this war would escalate to the nuclear level, then you are looking at tens of millions of casualties and the destruction of the eleventh largest economy in the world.85

Pyongyang could also escalate to attacking Japan with ballistic missiles. Japan is densely populated, with heavy concentrations of civilians in cities: the greater Tokyo area alone has a population of about 38 million.86 The regime might see such an attack as justified by its historic hostility toward Japan based on Japan's annexation of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945, or it could launch missiles in an attempt to knock out U.S. military assets stationed on the archipelago. A further planning consideration is that North Korea might also strike U.S. bases in Japan (or South Korea) first, possibly with nuclear weapons, to deter military action by U.S./ROK forces. When discussing the possibility of renewed hostilities on the Korean Peninsula, Secretary of Defense James Mattis stated that although the United States would likely prevail in a military campaign against the DPRK, it "would be probably the worst kind of fighting in most people's lifetimes."87

The possibly extraordinary loss of life presents other complicating factors to the prosecution of military operations on the Korean Peninsula. Evacuating surviving American noncombatants (noncombatant evacuation operations, or NEOs), including families of U.S. military stationed there, could place a further strain on U.S. military capabilities in theater, and could complicate the flow of additional reinforcements from the continental United States.88 Medical facilities could be overwhelmed handling civilian casualties—which, as noted above, might involve treating exposure to chemical if not biological or nuclear weapons—making it more difficult to treat military casualties.

|

|

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Information generated by [author name scrubbed] using data from the NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center's Gridded Population of the Word, v4, with a UN-adjusted population count (2015), available at http://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-count-adjusted-to-2015-unwpp-country-totals; Department of State (2015); Esri (2016); DeLorme (2016). |

Economic Impacts

The impact of renewed hostilities on South Korean, regional, and global economies, especially should hostilities escalate into a full-scale war, would likely be substantial. According to one rough estimate by a 2010 RAND study, the costs of a conventional war could amount to 60%-70% of South Korea's annual GDP, which in 2016 was $1.4 trillion. The study estimated that if North Korea detonated a 10 kt nuclear weapon in Seoul, the financial costs would be more than 10% of South Korea's GDP over the ensuing ten years. These figures should be treated as a rough order of magnitude rather than a precise costing estimate.89 Given the DPRK's impoverished state, ROK reconstruction costs might also be affected by the costs of rehabilitating the North Korean economy.

China's Reaction

A significant factor likely affecting policymakers deliberations regarding the use of military force on the Korean Peninsula is the question of whether a military conflict between the DPRK and the U.S./ROK runs the risk of a direct military clash with China, as occurred during the 1950-1953 Korean War. China has declared itself "firmly opposed to war and turmoil on the Peninsula," and "committed to a denuclearized, peaceful and stable Korean Peninsula and a settlement of relevant issues through dialogue and consultation."90 If the United States were to undertake preventive or preemptive strikes against North Korea, it could risk a major rupture in its relationship with China, which is the United States' top trading partner and holds upwards of $1.15 trillion in U.S. bonds as of June 2017.91

In August 2017, the Global Times, a nonauthoritative tabloid affiliated with the authoritative Chinese Communist Party publication The People's Daily, wrote in a much-discussed editorial that

China should also make clear that if North Korea launches missiles that threaten U.S. soil first and the U.S. retaliates, China will stay neutral.... If the U.S. and South Korea carry out strikes and try to overthrow the North Korean regime and change the political pattern of the Korean peninsula, China will prevent them from doing so.92

China's leadership has been known to use the Global Times to test policy proposals and messages while taking advantage of the deniability offered by the paper's nonauthoritative status. Whether this editorial was a test message from China's leadership, or generated independently by the Global Times, is unclear.

China increasingly has supported the U.S. and South Korea-led pressure campaign against Pyongyang since Kim Jong-un succeeded his father as DPRK leader in 2011. Yet, many if not most analysts believe that stability on the Korean Peninsula, rather than denuclearization, is the paramount priority of Chinese leaders with respect to the peninsula.93 Among other developments, the outbreak of war on the peninsula could lead to a massive flow of refugees into northeastern China, where large numbers of ethnic Koreans reside.

For years, the United States and South Korea have sought to hold discussions with China about various contingencies involving military conflict with and/or instability in North Korea, in part to reduce the chances of a China-U.S./ROK military clash. Chinese officials generally have resisted engaging in these discussions. Some observers believe this might be in part to avoid appearing to countenance U.S./ROK military action to denuclearize the peninsula.

Independent of such discussions, Chinese statements could complicate matters for the United States, as the possible articulation of Beijing's red lines could encourage the DPRK to continue taking aggressive action that falls just short of Chinese parameters for its rejection of Pyongyang's activities.

Implications for East Asia

The use of U.S. military force on the Korean Peninsula would likely have far-reaching implications for U.S. alliances and partnerships in the region, for great power politics and rivalries, and the overall security landscape in the Asia-Pacific, and perhaps more broadly. An outbreak of war on the peninsula could potentially upend two U.S. overarching priorities in East Asia: preserving U.S. interests and maintaining stability in the region. This section examines some of the possible impacts for regional powers and U.S. interests in East Asia.

China

Perhaps the most significant geopolitical question arising from a military conflict on the peninsula would be the effect on the U.S.-China relationship. Much would depend on China's involvement in the conflict, which could vary from hostile (challenging U.S./ROK forces in combat) to cooperative (working, for example, with the operation to secure the DPRK nuclear arsenal in the event of a regime collapse). During or after a military campaign, the Korean/Chinese border could become a geopolitically sensitive area, necessitating additional security forces. Regardless of the outcome, Washington and Beijing would likely be navigating new waters in the bilateral relationship.

If Beijing remained officially "neutral," China may look to establishing its leadership in a changing East Asian order. It could decide to be more assertive in claiming maritime territory, particularly in the South China Sea, if U.S. forces were consumed in Northeast Asia. It might also seek to change the terms of its relationship, peaceably or by force, with Taiwan, either because U.S. attention and resources are deployed elsewhere, or as part of a deal with Washington for its cooperation on the Korean Peninsula.94 In such a case, U.S. commitments related to Taiwan's security would likely face existential questions, and the U.S.-China relationship would face a fundamental realignment.

In post-conflict reconstruction, China would likely play a major role, given its experience in building infrastructure, proximity to the area, and availability of foreign currency reserves to finance reconstruction. China's establishment in recent years of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and its Belt and Road Initiative95 to boost economic connectivity within and across continents positions China well to perform such a role, and would heighten its influence.96 Even if the United States successfully executed a military campaign, China's capabilities would give Beijing considerable leverage in negotiations over the future of the peninsula, likely including discussions over whether a U.S. military presence would remain were the Korean Peninsula to be reunified.

Alliances with South Korea and Japan

For U.S. bilateral alliances—most prominently with South Korea and Japan—U.S. willingness to use military force against North Korea could reinforce the credibility of U.S. commitment to its allies. The credibility of the U.S. mutual defense treaties could also be strengthened, although controversial issues such as the degree of consultation leading up to any strike could create fissures. If a military action were judged by Seoul and/or Tokyo to be Washington's choice alone—and particularly if the conflict resulted in mass casualties of their citizens—the alliances could be deeply shaken, or even abandoned.

Despite years of preparation, the security partnerships could confront the inevitable challenges of operating in a war-time theater: (1) the strength of alliance planning, through decades of exercises and cooperation, would be tested; (2) issues such as operational control of the U.S./ROK forces would face immediate real-time challenges; (3) the logistical complexity of deploying troops and supplies to the theater from bases in Japan could encounter unanticipated obstacles; and (4) the ability of the Japanese Self Defense Forces to offer support for U.S./ROK military operations could pose difficult political questions for leaders in Seoul and Tokyo, given the distrust that seems to persist in Japan-South Korea relations.

In the aftermath of a military operation, the alliances could face additional questions about U.S. commitment and obligation to its allies. If the use of U.S. military force successfully erases U.S. homeland vulnerability to a DPRK attack, allies might ask what responsibility the United States would have in assisting South Korea or Japan if military operations have damaged their countries (for more, see "Economic Impacts"). If the regime in Pyongyang falls, the process of reunification—even under the most optimistic conditions—faces daunting challenges given the stark differences between the two populations in terms of education, culture, societal organization, and familiarity with democratic or free market practices.97 The duration and extent of reconstruction efforts could also become a major area of contention.

The two alliances could also face questions about their durability if the threat from North Korea is removed. The U.S.-ROK alliance in particular is based on defending the South from aggression from the DPRK; without the threat from North Korea, would Seoul feel the need to ally itself closely with the United States, or vice-versa, and would either party feel the need for a continued U.S. military presence? What other factors—especially pressure from Beijing—might sway Korean leaders?

Russia

Russia's future role in the region is uncertain, even more so in the event of a U.S. intervention. With Moscow thousands of miles away and with a relatively short border with the DPRK, Russia's security concerns are less immediate. However, Russia still maintains massive military capabilities that could be deployed to its Far East and complicate U.S./ROK operations.98 In addition, some maintain that the Kremlin has a strong interest in asserting itself in any emerging geopolitical order, and may seek to take advantage of a shake-up in the region.99 Some analysts argue that if the United States and its allies moved more aggressively to alter the situation on the Peninsula, or if the regime in Pyongyang collapsed on its own accord, Moscow and Beijing may find common cause in supporting North Korea. Both Russia and China share a strong desire to prevent a shift in the regional balance that a reunified peninsula under U.S. influence might produce.100

Possible Military Options

For illustrative purposes only, this section outlines potential options related to the possible use of military capabilities and their implications, along with attendant risks. Not all of these options are mutually exclusive, nor do they represent a complete list of possible options, implications, and risks. The following discussion is based entirely on open-source materials. CRS cannot verify whether any of these potential options are currently being considered by U.S. and ROK leaders. This list is intended to help elucidate the variety of ways that the military can be utilized in furtherance of foreign policy or national security objectives, and the different kinds of risks associated with different policy choices. As such, these notional options are intended to help Congress appreciate the different possible ways force might be employed to accomplish the goal of denuclearizing of the Korean Peninsula, or how the United States might respond to an initiation of hostilities by North Korea. The discussion of these options assumes no Chinese or Russian military intervention. Should either of those parties choose to become meaningfully involved, the strategic calculus would undoubtedly change in unpredictable and likely highly consequential ways.

The design of a military campaign depends on the policy goals that leaders are seeking to accomplish. In August 2017, Secretary of State Tillerson and Secretary of Defense Mattis articulated the U.S. policy objective and parameters for the Korean Peninsula as

the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.... [No] interest in regime change or accelerated reunification of Korea. We do not seek an excuse to garrison U.S. troops north of the Demilitarized Zone... [No] desire to inflict harm on the long-suffering North Korean people.101

If the U.S. objective is the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, U.S. and ROK leaders can seek to achieve this goal in a variety of ways. These range from increasing U.S. presence and posture on the Korean Peninsula, to communicating to Pyongyang—and possibly Beijing—that continuing along the current policy trajectory of nuclearization is counterproductive, or eliminating DPRK's nuclear and ICBM production capabilities and deployed systems, which would likely require intensive military manpower. The Trump Administration has not publicly detailed how it intends to advance toward the objective of denuclearization or, in particular, how the military might fit into such a campaign.

|

Preventive vs. Preemptive War Some of the military options described in this paper would likely require the U.S. to initiate military action in order to have a reasonable prospect of success. Scholars generally describe this kind of action as taking one of two forms: preemptive versus preventive war. Preemptive attacks are based on the belief that the adversary is about to attack, and that striking first is better than allowing the enemy to do so. The 1967 Israeli attack against Egypt that began the Six-Day War is a classic example of a preemptive attack. Preventive attacks, by contrast, are launched in response to less immediate threats, often motivated by the desire to fight sooner rather than later, generally due to an anticipated shift in the military balance, or acquisition of a key capability, by an adversary. Oft-cited examples of preventive attacks include the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and Israel's 1981 raid on the Osirak nuclear facility. International law tends to hold that preemptive attacks are an acceptable use of force, as are those that are retaliatory in nature. Justifying preventive attacks legally is a more difficult case to make under extant international law. Source: Karl P. Mueller, Jasen J. Castillo, Forrest E. Morgan, Negeen Pegahi and Brian Rosen, Striking First: Preemptive and Preventive Attack in U.S. National Security Policy (Arlington, VA: The Rand Corporation, 2006), available at https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2006/RAND_MG403.pdf. |

Maintain the Military Status Quo

From 2009 to 2016, Seoul and Washington tightly coordinated their respective North Korea policies, following a joint approach—often called "strategic patience"—that emphasized pressuring the regime to return to denuclearization talks through expanded multilateral and unilateral sanctions, attempting to persuade China to apply more pressure on Pyongyang, and boosting the capabilities of the U.S.-South Korea and U.S.-Japanese alliances. Despite the Trump Administration's casting of its "maximum pressure" approach as a departure from the Obama Administration's "strategic patience," numerous elements of their respective policies are similar: expanding U.S. and international sanctions, emphasizing China's ability to pressure North Korea, and coordinating policy with U.S. allies. Key changes from the Obama Administration's approach appear to be that

- the Trump Administration has raised the priority level of the North Korean threat, and

- Administration officials are openly discussing the possibility of a preventive military strike against North Korea.

Maintenance of the military status quo would amount to a de facto continuation of the U.S. policy of inexorably increasing unilateral and multinational pressure through economic and diplomatic means to compel North Korea to change its behavior while simultaneously deterring DPRK aggression on the Korean Peninsula.

Supporters of this course of action could argue that, of all the options available, it would be least likely to escalate the crisis on the Korean Peninsula for the immediate future, and that it provides time for international sanctions, which in their strictest forms began in 2016, to have an effect on North Korea.102 Other pressures, like increasing inflows of information perceived to be damaging to the regime into the DPRK, would also have more time to have an impact on the civilian population.

Opponents of this course of action might argue that the policy of "strategic patience" failed to compel the DPRK to abandon its nuclear weapons and ICBM capabilities, and that North Korea is unlikely to abandon its WMD capabilities unless the Kim regime concludes that retaining them puts its survival at stake.103 Opponents might also argue that maintaining the status quo may create time for sanctions to work, but also creates time for North Korea to develop a nuclear-tipped ICBM capable of reaching the U.S. homeland and for North Korea to expand the size of that capability. In addition, some analysts are particularly concerned that South Korea and Japan may reassess their commitment not to build their own nuclear deterrent if North Korea is able to hold the United States at risk. Many analysts fear that Japan and South Korea "going nuclear" could set off a new arms race in Asia that would raise the risk of accidents or miscalculations in the region.

Enhanced Containment and Deterrence

This option is somewhat more robust than merely maintaining the status quo, with greater emphasis on using U.S. military presence and posture to deter and contain North Korea.104 Statements by the DPRK indicate that the U.S. presence on the Korean Peninsula has long been unpalatable to Pyongyang. Taking that into account, in addition to diplomatic and economic measures, U.S. leaders might seek to use the U.S. military presence to underscore the costs of DPRK nuclearization through enhancing its forward presence on the Korean Peninsula and in the region (on bases in Japan and Guam, for example). This could be done through prepositioning equipment, enhancing defensive capabilities, building up troop levels, and/or boosting trilateral cooperation among the United States, South Korea, and Japan. Underscoring the costs of DPRK nuclearization, such actions could also enhance deterrence of possible conflict while ensuring that critical systems and units are nearby in the event of hostilities.

Recent dispatches of a U.S. carrier strike group and a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense deployment to South Korea are examples of this approach. The U.S. military has a wide array of prepositioned equipment, both at shore locations and afloat, that could be sent to South Korea or elsewhere within the region. Deploying additional ground troops to South Korea or elsewhere in the region is also an option. Redeploying U.S. tactical nuclear weapons onto the Korean Peninsula, as has been called for by the Liberty Korea Party is another such option.105 Some observers further argue that a combination of enhanced missile defenses, cyber defenses, U.S./ROK military exercises, and monitoring and interdiction of shipments106 to prevent North Korean WMD proliferation will sufficiently contain the DPRK until peaceful denuclearization can occur.107

Skeptics could argue that such moves could be construed by Pyongyang as a prelude to a ground attack on the DPRK. They could also argue that U.S. presence might have little impact on the decision-making calculus of the Kim regime, since the current U.S. posture and rhetorical threats of the use of military force previously in the region have failed to dissuade the DPRK from acquiring nuclear capabilities and delivery systems thus far. In addition, there are political and diplomatic challenges to increasing military presence in places like Okinawa or achieving more effective trilateral U.S.-ROK-Japan security cooperation.108

Deny DPRK Acquisition of Delivery Systems Capable of Threatening the United States

Pursuing this option may mean deemphasizing, at least for the immediate future, the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and instead focusing on mitigating, or even negating, the means of delivery of nuclear devices, in particular nuclear-tipped ICBMs. Without sufficient testing, however, an ICBM's reliability and effectiveness could remain unknown. It may therefore be more difficult to threaten the U.S. homeland credibly with such a capability in the absence of further test launches, which North Korea is likely to pursue in the near-term. The United States could attempt to shoot down every medium- and long-range missile and space launch with its ballistic missile defense (BMD) capabilities, such as the Aegis BMD, which is designed to intercept theater-range ballistic missiles, but not ICBMs.

Supporters could argue that a course of action along these lines has several advantages, including the possible disruption of DPRK acquisition of a reliable nuclear ICBM without sending additional forces into the region, which as discussed above, might arguably be seen as provocative by DPRK and other actors. It could also minimize risk to U.S. troops and their families in the region. Further, all North Korean missile tests are specifically prohibited by U.N. Security Council resolutions, which some proponents use as justification for such a course of action.109

Skeptics could argue that keeping one or more Aegis BMD ships in a relatively small geographic area for weeks or months on end could prevent the ships from performing other missions.110 In addition, two Aegis BMD ships in the 7th Fleet continue to be out of service for months or longer.111 A major risk is the possibility that an intercept of a DPRK ballistic missile test launch might fail, thereby undermining that deterrent capability in an evolving crisis, with implications perhaps extending beyond the region. Finally, there are risks involved with shooting down a missile that could spread debris over land, air, or ocean areas that have not been cleared through various advance aviation and maritime warnings.

Skeptics could also argue that the Kim regime could still respond militarily, which could escalate the conflict. North Korea would also still possess its nuclear weapons and could therefore proliferate either its nuclear material or weapons to other countries.112 Such a strategy also would not preclude Pyongyang from continuing to hold U.S. forces and installations—as well as U.S. allies including the ROK and Japan—at risk.

Eliminate ICBM Facilities and Launch Pads

This course of action would mean focusing less on North Korea's voluntary denuclearization and more on eliminating, possibly through limited air strikes, DPRK's long-range ballistic missiles and associated facilities. Although the majority of the DPRK's missiles have been launched from fixed sites, efforts are reportedly underway in North Korea to develop solid-fuel mobile missiles that can be deployed more rapidly than liquid-fueled missiles before their launch and are harder to detect than missiles fired from known fixed sites. Reportedly, many DPRK ballistic missile development and production facilities are located in hardened sites in North Korea's northeastern mountainous regions near the Chinese border, adding an additional element of risk of Chinese intervention if these facilities are attacked.113 The DPRK is also believed to operate a single Sinpo-class diesel-electric submarine that may be able to launch a submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM); this submarine was used to test the DPRK's KN-11 SLBM.114 Diesel-electric submarines can be difficult to detect and therefore challenging to target in the event of a limited strike, especially if they are submerged and not moving much, perhaps even for U.S. anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities.115

Under this option the United States could attack DPRK nuclear and ICBM facilities through airstrikes and cruise missile attacks. It is also possible that U.S. and ROK Special Operations forces could conduct direct action missions on the ground. These operations are considered to be high-risk—and could incur significant military casualties—compared with attacking targets with aerial assets. Advantages to this course of action may include the disruption of critical components of the DPRK's ICBM infrastructure, while signaling to Pyongyang that continuing its nuclear program is unacceptable, which could possibly bring the Kim regime back to the negotiating table.

Skeptics could argue that this course of action might escalate, rather than deescalate, the conflict. Further, they could maintain that it might degrade, but not eliminate, North Korea's ICBM capabilities, perpetuating the crisis and possibly spurring the DPRK to pursue its ICBM and nuclear weapons capabilities even more aggressively and in a manner less conducive to such disruption.

Eliminate DPRK Nuclear Facilities

This option would be a more expansive military effort than the previous option, as it would involve targeting a greater number of facilities. Possible targets in a limited strike scenario include nuclear production infrastructure, nuclear devices and missile warheads, and associated delivery vehicles.116 Production infrastructure includes reactor complexes, uranium mines and enrichment facilities, plutonium extraction facilities, related research and development facilities, and explosive test facilities.117 Similar to the previous option, these targets could be attacked by air assets and cruise missiles. Ground attacks by SOF might also be an option.118

Proponents might argue that this option is most likely to eliminate the DPRK's nuclear program to the greatest extent without undertaking regime change.119 Skeptics, however, could argue that a distinct possibility exists that the DPRK would escalate the conflict rather than return to denuclearization negotiations. Given limited intelligence and extensive use of hardened underground facilities by North Korea, some experts believe U.S. strikes would not fully eliminate the country's nuclear weapons program, and "at best, they'll set the program back several years."120 They could also argue that striking nuclear device/weapon sites or facilities could result in widespread radioactive contamination in the event they are damaged or destroyed. Further, if North Korea's nuclear weapons program cannot be destroyed by U.S. strikes, any residual capability including significant conventional military forces—even if nuclear-capable missiles, submarines, or aircraft are eliminated—could be employed against South Korean and U.S. military and civilian targets, or other allied forces.

Skeptics could also argue that there appears to be little information about the numbers, types, and whereabouts of DPRK nuclear devices and missile warheads, and that many of these facilities are believed to be underground in hardened facilities. Accordingly, finding and then eliminating these facilities would likely require highly manpower-intensive operations, and might therefore put considerable numbers of U.S./ROK forces at risk, possibly resulting in significant casualties.

DPRK Regime Change

Although the Tillerson/Mattis op-ed specifically states that the United States has no interest in regime change on the Korean Peninsula,121 it remains a potential (if unlikely) option, particularly should the Kim regime behave in an aggressive manner toward the United States or its allies.122 A more comprehensive operation that might make regime survival untenable could involve strikes against not only nuclear infrastructure but command and control facilities, key leaders, artillery and missile units, chemical and biological weapons facilities, airfields, ports, and other targets deemed critical to regime survival.123 This operation would be tantamount to pursuing full-scale war on the Korean Peninsula, and risk conflict elsewhere in the region.

Advocates of this argument might maintain that the root of the security challenge on the Korean peninsula is the Kim Jong Un regime itself, and that its elimination has the highest degree of likelihood of promoting regional and global security. Skeptics, however, could argue that eliminating the Kim regime involves a high degree of military and political risk, and that preparations for such a large-scale operation could be easily detected, possibly resulting in preemptive strikes by the DPRK against military and civilian targets.124 If an attack is suspected, they could argue, the DPRK could begin to disperse and hide units, making them more difficult to attack. Such a large-scale attack, opponents of pursuing regime change may say, could result in an escalation to a full-scale war if North Korea believes the operation is intended to decapitate the regime.

A regime change operation, they could also argue, would likely require significant ground force involvement and would require a build-up of U.S. forces before it could be undertaken. In addition to possible participation in ground combat, they could argue, U.S. ground forces could be required for post-conflict stabilization operations that could last years. With ongoing U.S. troop commitments in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, such a substantial long-term presence on the Korean Peninsula could have significant ramifications for the availability and readiness of U.S. ground forces or, over the long term, for the required size of the U.S. military.

Withdraw U.S. Forces125

Some observers contend that the only reason the DPRK views the United States as a risk is because U.S. troops are stationed in South Korea and Japan.126 One analyst states

No one should expect a kinder, gentler Kim to emerge. But his "byungjin" policy of pursuing both nuclear weapons and economic growth faces a severe challenge, especially since sanctions continue to limit the DPRK's development. With the United States far away he would have more reason to listen to China, which long has advised more reforms and fewer nukes. He also might be more amenable to negotiate limits on his missile and nuclear activities, if not give up the capabilities entirely. Since nothing else has worked, an American withdrawal would be a useful change in strategy.127