U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Changes from January 17, 2020 to January 18, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S. Sanctions on Russia: A Key Policy Tool

Russia Sanctions and the Trump18, 2022 In early 2022, Congress, the Biden Administration, and other stakeholders are considering the prospect of new sanctions on Russia. In response to a Russian military buildup near and in Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, the United States and European allies have said they would impose additional sanctions Specialist in Russian and in the event of further Russian aggression against Ukraine. Such sanctions could include greater European Affairs restrictions on transactions with Russian financial institutions and U.S. technology exports, as well as the suspension of Russia’s pending Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline project. Further additional sanctions, including on Russia’s energy sector and secondary market transactions in Kristin Archick Specialist in European Russian sovereign debt, also may be under consideration. Affairs Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian activities. The United States maintains sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine Rebecca M. Nelson starting in 2014Administration- How Effective Are Sanctions on Russia?

- About the Report

- Use of Economic Sanctions to Further Foreign Policy and National Security Objectives

- Role of the President

- Role of Congress

- Sanctions Implementation

- U.S. Sanctions on Russia

- Sergei Magnitsky Act and the Global Magnitsky Act

- Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

- Specially Designated Nationals

- Sectoral Sanctions Identifications

- Ukraine-Related Legislation

- Election Interference and Other Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities

- Related Actions

- Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017

- Issues Related to CRIEEA Implementation

- Use of a Chemical Weapon

- Other Sanctions Programs

- Weapons Proliferation

- North Korea Sanctions Violations

- Syria-Related Sanctions

- Venezuela-Related Sanctions

- Energy Export Pipelines

- Transnational Crime

- Terrorism

- Restrictions on U.S. Government Funding

- Russian Countersanctions

- U.S. and EU Coordination on Sanctions

- U.S. and EU Cooperation on Ukraine-Related Sanctions

- U.S. and EU Ukraine-Related Sanctions Compared

- Sanctions Targeting Individuals and Entities

- Sectoral Sanctions

- Developments Since 2017

- Potential New EU Sanctions on Russia

- Economic Impact of Sanctions on Russia

- Russian Economy Since 2014

- Estimates of the Broad Economic Impact

- Factors Influencing the Broad Economic Impact

- Impact on Russian Firms and Sectors

- Factors Influencing the Impact on Firms and Sectors

- Outlook

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

- Table B-1. U.S. Sanctions on Russia for Which Designations Have Been Made

- Table B-2. U.S. Sanctions on Russia for Which Designations Have Yet to Be Made

- Table C-1. U.S. and EU Sectoral Sanctions

- Table D-1. Russia's Largest Firms and U.S. Sanctions

- Table D-2. Selected Major Russian Firms Designated for Sanctions in 2014

Summary

Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia's 2014 invasion of Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian , to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian

Specialist in International

aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposedmaintains sanctions on Russia in

Trade and Finance

response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Mostmalicious cyber-enabled activities and influence operations (including

election interference), the use of a chemical weapon, human rights abuses, the use of energy

Dianne E. Rennack

exports as a coercive or political tool, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and

Specialist in Foreign Policy

support to the governments of Syria and Venezuela. Many Members of Congress support a robust

Legislation

Members of Congress support a robust use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia'’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions.

Sanctions related to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs

(E.O.s) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine: the Legislation establishing sanctions specifically in response to Russian actions includes the following:

Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-208, Title IV; 22 U.S.C. 5811 note) Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014, as

amended (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the ; 22 U.S.C. 8901 et seq.)

Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014, as amended (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859).

In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the P.L. 113-272; 22 U.S.C. 8921 et seq.) Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017, as amended (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44/H.R. 3364, ,

Countering America'’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA], Title II). This legislation codified Ukraine-related and cyber-related EOs, strengthened sanctions authorities initiated in Ukraine-related EOs and legislation, and identified several new targets for sanctions. It also established congressional review of any action the President takes to ease or lift a variety of sanctions.

The United States established sanctions related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine largely in coordination with the European Union (EU). Since 2017, the efforts of Congress and the Trump Administration to tighten sanctions on Russia have prompted some concern in the EU about U.S. commitment to sanctions coordination and U.S.-EU cooperation on Russia and Ukraine more broadly. Many in the EU oppose the United States' use of secondary sanctions, including sanctions aimed at curbing Russian energy export pipelines to Europe, such as Nord Stream 2.

In terms of economic impact, studies suggest that sanctions have had a negative but relatively modest impact on Russia's growth. Changes in world oil prices have had a much ; 22 U.S.C. 9501 et seq.)

Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act of 2019, as amended (PEESA; P.L. 116-92, Title LXXV; 22

U.S.C. 9526 note)

In imposing sanctions on Russia, the United States has coordinated many of its actions with the European Union (EU) and others. As the invasion of Ukraine progressed in 2014, the Obama Administration considered EU support for sanctions to be crucial, as the EU had more extensive trade and investment ties with Russia than the United States. Many policymakers and observers view ongoing U.S.-EU cooperation in imposing sanctions as a tangible indication of U.S.-European solidarity, frustrating Russian efforts to drive a wedge between transatlantic partners.

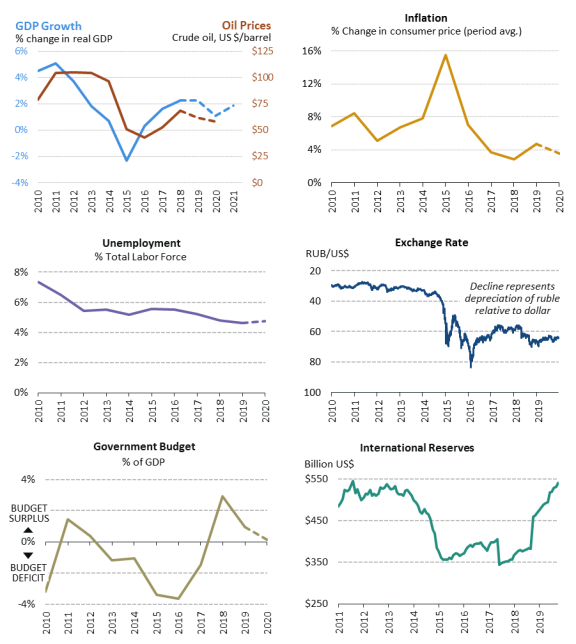

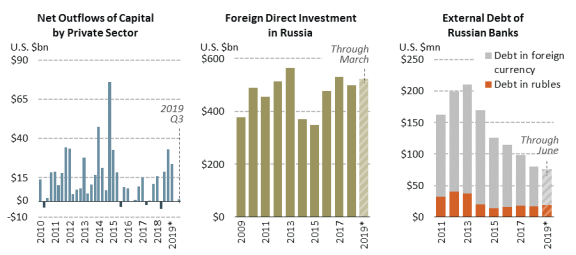

In terms of economic impact, studies suggest sanctions have had a negative but relatively modest impact on Russia’s growth. Changes in world oil prices and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic appear to have had a greater impact than sanctions greater impact on the Russian economy. After oil prices rose in 2016, Russia'’s economy began to strengthen even as sanctions remained in place and, in some instances, were tightened. The Obama Administration and the EU designed sanctions related to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine, in part, to impose longer-term pressures on Russia'’s economy while minimizing collateral damage to the Russian people and to the economic interests of the countries imposing sanctions.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 36 link to page 36 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 44 link to page 45 link to page 47 link to page 48 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

U.S. Sanctions on Russia: A Key Policy Tool ........................................................................... 1 How Effective Are Sanctions on Russia? .................................................................................. 2 About the Report ....................................................................................................................... 3

Use of Economic Sanctions to Further Foreign Policy and National Security Objectives .............. 3

Role of the President ................................................................................................................. 5 Role of Congress ....................................................................................................................... 5 Sanctions Implementation ......................................................................................................... 6

U.S. Sanctions on Russia ................................................................................................................. 6

Sanctions Related to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine................................................................... 7

Specially Designated Nationals .......................................................................................... 7 Sectoral Sanctions Identifications ....................................................................................... 9 Ukraine-Related Legislation ............................................................................................. 10

Election Interference and Other Malicious Cyber-Enabled or Intelligence Activities ............ 12

Sanctions Authorities ........................................................................................................ 12 Related Actions ................................................................................................................. 14

Use of a Chemical Weapon ..................................................................................................... 19

CBW Act Sanctions .......................................................................................................... 19 Poisoning of Sergei Skripal............................................................................................... 20 Poisoning of Alexei Navalny ............................................................................................ 21

Human Rights Abuses and Corruption .................................................................................... 23

Sanctions Authorities ........................................................................................................ 23 Related Actions ................................................................................................................. 24 Section 241 “Oligarch” List and Related Sanctions ......................................................... 25

Nord Stream 2: Energy Exports as a Coercive or Political Tool ............................................. 27 Other Sanctions Programs ....................................................................................................... 28

Weapons Proliferation ....................................................................................................... 28 North Korea Sanctions Violations ..................................................................................... 30 Syria-Related Sanctions .................................................................................................... 31 Venezuela-Related Sanctions ............................................................................................ 32 Transnational Crime .......................................................................................................... 32 Terrorism ........................................................................................................................... 33

Restrictions on U.S. Government Funding ............................................................................. 33

Russian Countersanctions .............................................................................................................. 34 U.S. and EU Coordination on Sanctions ....................................................................................... 35

Comparing U.S. and EU Ukraine-Related Sanctions .............................................................. 35 EU Concerns About U.S. Sanctions After 2017 ...................................................................... 38 Other EU Sanctions in Response to Russian Activities .......................................................... 39

Economic Impact of Sanctions on Russia ..................................................................................... 40

Impact on Russia’s Economy Broadly .................................................................................... 40 Impact on Russian Firms ......................................................................................................... 41 Impact on Russian Government Finances ............................................................................... 43

Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 44

Congressional Research Service

link to page 44 link to page 14 link to page 51 link to page 56 link to page 60 link to page 61 link to page 50 link to page 51 link to page 58 link to page 60 link to page 61 link to page 62 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Figures Figure 1. Economic Growth in Russia, 1994-2021 ....................................................................... 40

Tables Table 1. U.S. Sanctions Related to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine ................................................. 10

Table B-1. U.S. Sanctions on Russia for Which Designations Have Been Made ......................... 47 Table B-2. U.S. Sanctions on Russia for Which Designations Have Yet to Be Made ................... 52 Table D-1. U.S. and EU Sectoral Sanctions .................................................................................. 56 Table E-1. Russia’s Largest Firms and U.S. Sanctions ................................................................. 57

Appendixes Appendix A. Legislative Abbreviations and Short Titles .............................................................. 46 Appendix B. U.S. Sanctions on Russia ......................................................................................... 47 Appendix C. Sanctions in Selected Russia-Related Legislation ................................................... 54 Appendix D. U.S. and EU Sectoral Sanctions ............................................................................... 56 Appendix E. Russian Firms and U.S. Sanctions ........................................................................... 57

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 58

Congressional Research Service

U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Introduction

minimizing collateral damage to the Russian people and to the economic interests of the countries imposing sanctions.

Debates about the effectiveness of sanctions against Russia continue in Congress, in the Administration, and among other stakeholders. Russia has not reversed its occupation and annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region, nor has it stopped sustaining separatist regimes in eastern Ukraine. In 2018, it extended its military operations against Ukraine to nearby waters. At the same time, Russia has not expanded its land-based operations in Ukraine, and Moscow participates in a conflict resolution process that formally recognizes Ukraine's sovereignty over Russia-controlled areas in eastern Ukraine. With respect to other malign activities, the relationship between sanctions and changes in Russian behavior is difficult to determine. Nonetheless, many observers argue that sanctions help restrain Russia or that their imposition is an appropriate foreign policy response regardless of immediate effect.

The 116th Congress has continued to consider new sanctions on Russia. The FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92/S. 1790) establishes sanctions related to the construction of Nord Stream 2 and other Russian subsea natural gas export pipelines. The Defending American Security from Kremlin Aggression Act of 2019 (S. 482) and other legislation propose additional measures to address Russian election interference, aggression in Ukraine, arms sales, and other activities.

Introduction

U.S. Sanctions on Russia: A Key Policy Tool

U.S. Sanctions on Russia: A Key Policy Tool Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavioractivities. The United States has imposedmaintains sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia'’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposedmaintains sanctions on Russia in response to (and to deter) election interference and malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon and influence operations (including election interference), the use of a chemical weapon, human rights abuses, the use of energy exports as a coercive or political tool, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to the governments of Syria and Venezuela. MostMany Members of Congress support a robust use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia'’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions.

Sanctions related to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on national emergency authorities granted the office of the President in the National Emergencies Act (NEA; P.L. 94-412412; 50 U.S.C. 16211601 et seq.) and International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA; P.L. 95-223; 50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.) and exercised by President Barack Obama in 2014 in a series of executive orders (EOsE.O.s 13660, 13661, 13662, 13685). The Obama and Trump , Trump, and Biden Administrations have used these EOsE.O.s to impose sanctions on more than 680 Russian individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft.

hundreds of individuals and entities (as well as on vessels and aircraft).

The executive branch also has used a variety of EOsE.O.s and legislation to impose sanctions on RussianRussia and related individuals and entities in response to a number of other concerns. numerous other activities of concern. Legislation that established sanctions specifically on Russian individuals and entitiesin response to Russian actions includes the following:

-

Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-208, Title

IV; 22 U.S.C. 5811 note)

. -

Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of

Ukraine Act of 2014, as amended (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95; 22 U.S.C. 8901 et seq.)

. -

Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014, as amended (UFSA; P.L. 113-272; 22

U.S.C. 8921 et seq.)

. -

Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017, as amended

(CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44, Countering America

'’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA], Title II; 22 U.S.C. 9501 et seq.).

The last of these, CRIEEA, codifies Ukraine-related and cyber-related EOs, strengthens sanctions authorities initiated in Ukraine-related EOs and legislation, and identifies several new sanctions targets. It also establishes congressional review of any action the President takes to ease or lift a variety of sanctions imposed on Russia.

Russia Sanctions and the Trump Administration

The Trump Administration's implementation of sanctions on Russia, particularly primary and secondary sanctions under CRIEEA, has raised questions for some Members of Congress about the Administration's commitment to holding Russia responsible for its malign activities. Administration officials contend they are implementing a robust set of sanctions on Russia, including new CRIEEA requirements, and note that diligent investigations take time.

As of January 2020, the Trump Administration has made 29 designations based on new sanctions authorities in CRIEEA, relating to cyberattacks and/or affiliation with Russia's military intelligence agency (§224, 24 designations), human rights abuses (§228, amending SSIDES, 3 designations), and arms sales (§231, 2 designations). The Administration has not made designations under CRIEEA authorities related to pipeline development, privatization deals, or support to Syria (§§232-234), nor has it made other designations under SSIDES or UFSA (as amended by CRIEEA, §§225-228), related to weapons transfers abroad, gas export cutoffs, certain oil projects, corruption, and secondary sanctions against foreign persons that facilitate significant transactions or sanctions evasion for Russia sanctions designees. Some Members of Congress have called on the President to make more designations based on CRIEEA's mandatory sanctions provisions.

The Trump Administration has made many Russia sanctions designations under other sanctions authorities, however. These authorities include Ukraine-related and cyber-related EOs codified by CRIEEA, as well as EOs related to weapons proliferation, Iran, North Korea, Syria, Venezuela, transnational crime, and international terrorism. The Administration also has made designations based on legislation, such as the Sergei Magnitsky Act; the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (22 U.S.C. 2656 note); the Iran, North Korea, and Syria Nonproliferation Act, as amended (INKSNA; 50 U.S.C. 1701 note); and the Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991 (CBW Act; 22 U.S.C. 5601 et seq.).

The United States imposed sanctions related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in coordination

Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act of 2019, as amended (PEESA; P.L. 116-

92, Title LXXV; 22 U.S.C. 9526 note)

In imposing sanctions on Russia, the United States has coordinated many of its actions with the European Union (EU), the United Kingdom (UK), and others. As the invasion of Ukraine progressed in 2014, the Obama Administration argued thatconsidered EU support for sanctions wasto be crucial, as the EU hashad more extensive trade and investment ties with Russia than does the United States. Many viewpolicymakers and observers view ongoing U.S.-EU cooperation in imposing sanctions as a tangible indication of U.S.-European solidarity, frustrating Russian efforts to drive a wedge between transatlantic partners.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 45 link to page 6 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

How Effective Are Sanctions on Russia? Many observers have debated the degree to which sanctions and the possibility of future sanctions promote change in Russia’s behavior. Russia has deepened its hold over Ukraine’s occupied Crimea region and separatist regions in eastern Ukraine. Russiabetween transatlantic partners. Since 2017, however, the efforts of Congress and the Trump Administration to tighten U.S. sanctions have been more unilateral, prompting some concern in the EU about U.S. commitment to sanctions coordination and U.S.-EU cooperation on Russia and Ukraine more broadly.

How Effective Are Sanctions on Russia?

The United States (together, in some cases, with the EU and others) has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly to pressure Russia to withdraw from Crimea and eastern Ukraine; to cease malicious cyber activity against the United States, its allies, and partners; to deter and, in some instances, take punitive steps in response to human rights abuses and corruption; to abide by the Chemical Weapons Convention; and to halt Russia's support to the North Korean, Syrian, and Venezuelan regimes.

Many observers have debated the degree to which sanctions promote change in Russia's behavior. With respect to Ukraine, Russia has not reversed its occupation and annexation of Crimea, nor has it stopped sustaining separatist regimes in eastern Ukraine. It also has extended military operations to nearby waters, interfering with commercialmaritime traffic traveling to and from ports in eastern Ukraine. In November 2018, Russian border guard vessels forcibly prevented three Ukrainian naval vessels from transiting the Kerch Strait, the waterway connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Azov, firing on them as they sought to leave the area and imprisoning their crew members for 10 months. At the same time, Russia has signed two agreements that formally recognize Ukraine' to and from ports in eastern Ukraine, and since 2021 has engaged in a buildup of military forces near the Ukrainian border. As of mid-January 2022, however, Russia continues to nominally recognize Ukraine’s sovereignty over Russia-controlled areas in eastern Ukraine, and Russia-led separatist military operations against Ukraine have been limited to areas along the perimeter of the current conflict zone. Russia has not expanded its military aggression to other states.

With respect to other malign activities, thefurther into Ukraine or to other states.

The relationship between sanctions and changes in Russianother Russian malign behavior is also difficult to determine. Sanctions in response to election interference, malicious cyber-enabled activitiesmalicious cyber, influence, and other intelligence activities, use of chemical weapons, human rights abuses, corruption, use of a chemical weaponuse of energy exports as a coercive or political tool, weapons proliferation, and support toillicit trade with North Korea, Iran, Syria,and support to Syria and Venezuela are relatively limited and highly targeted. To the extent that Russia does changechanges its behavior, other factors besides sanctions could be responsible.

For example, Russian policymakers may be willing to incur the cost of sanctions, whether on the national economy or on their own personal wealth, in furtherance of Russia'

To the extent that Russian behavior does not change, it may be because Russian policymakers are willing to incur the cost of sanctions in furtherance of Russia’s foreign policy goals. Sanctions also might have the unintended effect of boosting internal support for the Russian government, whether through appeals to nationalism or through Russian elites'’ sense of self-preservation. Finally, sanctions may target individuals that have less influence on Russian policymaking than the United States assumes.

FurthermoreIn addition, the Russian government has sought to minimize the impact of sanctions on favored individuals and entities through subsidies, preferential contracts, import substitution policies, and alternative markets (see “Impact on Russian Firms,” below).

In addition, the economic impact of sanctions may not be consequential enough to affect Russian policy. Studies suggest that sanctions have had a negative but relatively modest impact on Russia's growth; changes in world oil prices have had a much greater impact on the Russian economy. Most sanctions on Russia do not broadly target the Russian economy or entire sectors. Rather, they consist of broad restrictions against specific individuals and entities, as well as narrower restrictions against wider groups of Russian companies. Overall, more than four-fifths of the largest 100 firms in Russia (in 2018) are not directly subject to any U.S. or EU sanctions, including companies in a variety of sectors, such as transportation, retail, services, mining, and manufacturing.1 Although Russia faced several economic challenges in 2014-2015, including its longest recession in almost 20 years, the 2014 collapse in global oil prices had a larger impact than sanctions.2 Russia's economy strengthened in 2016 and 2017, as oil prices rose.

The relatively low impact of sanctions on the Russian economy is partially by design. The Obama Administration and the EU intended for sanctions related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine to have a limited and targeted economic impact. They’s growth and that changes in world oil prices and economic disruptions associated with the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have had a greater impact than sanctions.1 Although Russia faced several economic challenges in 2014-2015, including its longest recession in almost 20 years, a collapse in global oil prices in 2014 had a larger impact than sanctions. As oil prices recovered, Russia’s economy stabilized and grew at a modest pace. Economic disruptions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic led to another contraction in 2020, followed by recovery in 2021.

The modest macroeconomic effects of sanctions were largely by design. Most sanctions on Russia do not broadly target the Russian economy or entire sectors. Rather, they consist of broad restrictions against specific individuals and entities, as well as narrower restrictions on wider groups of Russian companies and certain transactions with the Russian state. The United States and the EU generally have sought to target individuals and entities responsible for offending policies and/or associated with key Russian policymakers in a way that wouldcould get Russia to change its behavior while minimizing collateral damage to the Russian people and to the economic interests of the countries imposing sanctions.32 Moreover, some sanctions were have been intended to put only long-term pressure on the Russian economy, by denying oil companies access to Western technology to modernize their industry or develop new sources of oilfor instance by making it harder 1 International Monetary Fund (IMF), Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2017 Article IV Consultation, July 10, 2017; and Daniel P. Ahn and Rodney D. Ludema, “The Sword and the Shield: The Economics of Targeted Sanctions,” European Economic Review, vol. 130, November 2020.

2 See, for example, U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Russian Officials, Members of the Russian Leadership’s Inner Circle, and an Entity for Involvement in the Situation in Ukraine,” press release, March 20, 2014; and Ahn and Ludema, “The Sword and the Shield,” 2020 (see footnote 1).

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 29 link to page 29 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

for Russia to modernize its oil sector with access to Western technology and capital. The full economic ramifications of thesesuch restrictions potentiallymay have yet to materialize.

There is some evidence that U.S. sanctions on Russia can have broad economic effects if they are applied to economically significant targets. HoweverAt the same time, doing so may create instability in global financial markets and opposition by U.S. allies, which generally have stronger economic relationships with Russia than the United States does. In . In April 2018, for example, the United States imposed sanctions on Rusal, a global aluminum firm, which had broad effects that rattled Russian and global financial markets. These sanctions marked the first time the United States had made a top-20 Russian firm completely off-limits, and the first time the Department of the Treasury appeared prepared to implement CRIEEA-mandated secondary sanctions. In January 2019, however, the Department of the Treasurydesignated a top Russian firm for sanctions that would affect nearly all economic activity and the first time the Treasury Department appeared ready to enforce CRIEEA-mandated secondary sanctions on persons that continued to conduct transactions with a sanctioned Russian firm. In 2019, however, the Treasury Department removed sanctions on Rusal and two related companies after Kremlin-connected billionaire Oleg Deripaska, who is subject to sanctions, agreed to relinquish his control over the three firms (for more, see "“Section 241 "Oligarch" List," below).

“Oligarch” List and Related Sanctions,” below). About the Report

This report provides a comprehensive overview of the use of sanctions in U.S. foreign policy toward Russia. It is compartmentalized, however, so that readers primarily interested in a particular issue, for example sanctions in response to Russia'’s use of a chemical weaponweapons, may find the relevant information in a subsection of the report.

The report first provides an overview of U.S. sanctions authorities and tools, particularly as they apply to Russia. It next describes various sanctions regimes that the executive branch has used to impose sanctions on Russian individuals and entitiesin response to Russian activities or that are available for this purpose, addressing authorities, tools, targets, and context. Third, the report briefly discusses countersanctions that Russia has introduced in response to U.S. and other sanctions. Fourth, it addresses the evolution of U.S. coordination with the European UnionEU on Russia sanctions policy, and similarities and differences between U.S. and EU sanctions regimes. Finally, the report assesses the economic impact of sanctions on Russia at the level of the national economy and individual firms.

Appendixes provide more detailed information regarding the use of various sanctions authorities and Russia-related targets. Use of Economic Sanctions to Further Foreign Policy and National Security Objectives

Economic sanctions provide a range of tools Congress and the President may use to seek to alter or deter the objectionable behavior of a foreign government, individual, or entity in furtherance of U.S. national security or foreign policy objectives.

Scholars have broadly defined economic sanctions as "“coercive economic measures taken against one or more countries [or individuals or entities] to force a change in policies, or at least to demonstrate a country'’s opinion about the other'’s policies.”3 Economic sanctions may include

3 Barry E. Carter, International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 4. Also see Gary Hufbauer, Jeffrey Schott, and Kimberly Elliott et al., Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 3rd edition (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2007); and U.S. International Trade Commission, Overview and Analysis of Current U.S. Unilateral Economic Sanctions, Investigation No. 332-391, Publication 3124, Washington, DC, August 1998.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 9 link to page 9 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

s policies."4 Economic sanctions may include limits on trade, such as overall restrictions or restrictions on particular exports or imports; the blocking of assets and interest in assets subject to U.S. jurisdiction; limits on access to the U.S. financial system, including limiting or prohibiting transactions involving U.S. individuals and businesses; and restrictions on private and government loans, investments, insurance, and underwriting. Sanctions also can include a denial of foreign assistance, government procurement contracts, and participation or support in international financial institutions.5

4 Sanctions that target third parties—those not engaged in the objectionable activity subject to sanctions but engaged with the individuals or entities that are—are popularly referred to as secondary sanctions. Secondary sanctions often are constructed to deter sanctions evasion, penalizing those that facilitate a means to avoid detection or that provide alternative access to finance.

The United States has applied a variety of sanctions in response to objectionablemalign Russian activities. Most sanctions on Russia, including most sanctions established by executive order (see "“Role of the President," ,” below), do not target the Russian state directly. Instead, they consist of designations of specific individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN) of the Department of the Treasury'Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). Sanctions block the U.S.-based assets of thoseindividuals and entities designated as SDNs and generally prohibit U.S. individuals and entities from engaging in transactions with them.5 In addition, the Secretary of State, in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security and Attorney General, is tasked with denying entry into the United States of, or revoking visas granted to, designated foreign nationals.

Sanctions in response to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine also consist of sectoral sanctions. Often, sectoral sanctions broadly apply to specific sectors of an economy. In the case of sanctions on Russia, sectoral sanctions have a narrower meaning; they apply to specific entities in Russia's ’s financial, energy, and defense sectors that OFAC has identified for inclusion on the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications (SSI) List. These sectoral sanctions prohibit U.S. individuals and entities from engaging in specific kinds of transactions related to lending, investment, and/or trade with entities on the SSI List, but they permit other transactions.

Another major category of sanctions on Russia consists of a presumption of denial to designated end users for export licenses. The Department of Commerce'’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) places entities subject to export restrictions on the Entity List (Supplement No. 4 to Part 744 of the Export Administration Regulations).6

6

4 Not everyone agrees on what the sanctions toolbox includes. For example, some characterize export controls, limits on foreign assistance, or visa denials as foreign policy tools that are less about changing the target’s behavior than about administering U.S. foreign policy while meeting the requirements and obligations the United States assumes under treaties, international agreements, and its own public laws. See Senator Jesse Helms, “What Sanctions Epidemic? U.S. Business’ Curious Crusade,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 78, no. 1 (January/February 1999), pp. 2-8.

5 More recently, some sanctions regimes have included the designation of vessels and aircraft owned or controlled by a designated individual or entity in order to preempt sanctions evasion by means of re-registration or reflagging.

6 The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) established an Entity List in 1997 to oversee U.S. compliance with international treaty and agreement obligations to control the export of materials related to weapons of mass destruction. Subsequently, the Entity List expanded to include entities engaged in activities considered contrary to U.S. national security and/or foreign policy interests. U.S. Department of Commerce, “Entity List,” at https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/policy-guidance/lists-of-parties-of-concern/entity-list.

Congressional Research Service

4

U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Role of the President Role of the President

The President, for a variety of reasons related to constitutional construction and legal challenges throughout U.S. history, holds considerable authority when economic sanctions are used in U.S. foreign policy.77 If Congress enacts sanctions in legislation, the President is to adhere to the provisions of the legislation but is responsible for determining the individuals and entities to be subject to sanctions.

The President also often has the authority to be the sole decisionmaker in initiating and imposing sanctions. The President does so by determining, pursuant to the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), that there has arisen an "“unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States."8”8 The President then declares that a national emergency exists, as provided for in the National Emergencies Act (NEA), submits the declaration to Congress, and establishes a public record by publishing it in the Federal Register.9 9 Under a national emergency, the President may invoke the authorities granted his office in IEEPA to investigate, regulate, or prohibit transactions in foreign exchange, use of U.S. banking instruments, the import or export of currency or securities, and transactions involving property or interests in property under U.S. jurisdiction.10

10

President Obama invoked NEA and IEEPA authorities to declare that Russia'’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine constituted a threat to the United States. On that basis, he declared the national emergency on which most sanctions related to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine are based. In addition, President Obama and President Trump also have invoked NEA and IEEPA authorities to declare national emergencies related to cyber-enabled malicious activities and election interference.

President Biden has invoked NEA and IEEPA authorities to declare a national emergency related to a number of specified harmful foreign activities undertaken by or on behalf of the Russian government.

Role of Congress Role of Congress

Congress influences which foreign policy and national security concerns the United States responds to with sanctions by enacting legislation to authorize, and in some instances require, the President to use sanctions. Congress has taken the lead in authorizing or requiring the President (or executive branch) to use sanctions in an effort to deter weapons proliferation, international terrorism, illicit narcotics trafficking, human rights abuses, regional instability, cyberattacks, corruption, and money laundering. Legislation can define what sanctions the executive branch is to apply, as well as the conditions that need to be met before these sanctions may be lifted.

One limitation on the role of Congress in establishing sanctions originates in the U.S. Constitution'

7 The Constitution divides foreign policy powers between the executive and legislative branches in a way that requires each branch to remain engaged with and supportive of, or responsive to, the interests and intentions of the other. See U.S. Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Strengthening Executive-Legislative Consultation on Foreign Policy, Congress and Foreign Policy Series (No. 8), 98th Cong., 1st sess., October 1983, pp. 9-11.

8 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA); P.L. 95-223, §202(a); 50 U.S.C. 1701(a). For more, see CRS Report R45618, The International Emergency Economic Powers Act: Origins, Evolution, and Use, coordinated by Christopher A. Casey.

9 National Emergencies Act (NEA); P.L. 94-412, §201; 50 U.S.C. 1621. 10 IEEPA, §203; 50 U.S.C. 1702.

Congressional Research Service

5

U.S. Sanctions on Russia

One limitation on the role of Congress in establishing sanctions originates in the U.S. Constitution’s bill of attainder clause.11s bill of attainder clause.11 Congress may not enact legislation that "“legislatively determines guilt and inflicts punishment upon an identifiable individual without provision of the protections of a judicial trial."12”12 In other words, Congress may enact legislation that broadly defines categories of sanctions targets and objectionable behavior, but it is left to the President to "“[determine] guilt and [inflict] punishment"”—that is, to populate the target categories with specific individuals and entities.

Sanctions Implementation

In the executive branch, several agencies have varying degrees of responsibility in implementing and administering sanctions. Primary agencies, broadly speaking, have responsibilities as follows:

-

Department of the Treasury

'’s OFAC designates SDNs to be subject to the blocking of U.S.-based assets; designates non-SDNs for which investments or transactions may be subject to conditions or restrictions; prohibits transactions; licenses transactions relating to exports and investments (and limits those licenses); restricts access to U.S. financial services; restricts transactions related to travel, in limited circumstances; and (with regard to Russia sanctions) identifies entities for placement on the SSI List as subject to investment and trade limitations. -

Department of State restricts visas, arms sales, and foreign aid; implements arms

embargos required by the United Nations; prohibits the use of U.S. passports to travel, in limited circumstances; and downgrades or suspends diplomatic relations.

-

Department of Commerce

'’s BIS restricts licenses for commercial exports, end users, and destinations. -

Department of Defense restricts arms sales and other forms of military

cooperation. -

cooperation.

Department of Justice investigates and prosecutes violations of sanctions and

export laws.

13

13 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

The United States imposes sanctions on Russia in accordance with several laws and executive orders. In 2012, the United States introduced a new sanctions regime on Russia in response to human rights abuses. In 2014, the United States introduced an extensive new sanctions regime on Russia in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In 2016, the United States imposed sanctions on Russian individuals and entities for election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities. In 2017, legislation was enacted to strengthen existing sanctions authorities and establish new sanctions in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, and corruption. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russian individuals and entities in response to the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, trade with North Korea in violation of U.N. Security Council requirements, support for the Syrian and Venezuelan governments, transnational crime, and international terrorism.

For an overview of Russia sanctions authorities and designations, see Appendix B.

Sergei Magnitsky Act and the Global Magnitsky Act

In December 2012, Congress passed and the President signed into law the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012 (hereinafter the Sergei Magnitsky Act).14 This legislation bears the name of Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian lawyer and auditor who died in prison in November 2009 after uncovering massive tax fraud that allegedly implicated government officials. The act entered into law as part of a broader piece of legislation related to U.S.-Russia trade relations (see text box entitled "Linking U.S.-Russia Trade to Human Rights," below).

The Sergei Magnitsky Act requires the President to impose sanctions on those he identifies as having been involved in the "criminal conspiracy" that Magnitsky uncovered and in his subsequent detention, abuse, and death.15 The act also requires the President to impose sanctions on those he finds have committed human rights abuses against individuals who are fighting to expose the illegal activity of Russian government officials or seeking to exercise or defend internationally recognized human rights and freedoms.

The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (P.L. 114-328, Title XII, Subtitle F; 22 U.S.C. 2656 note) followed in 2016.16 This act authorizes the President to apply globally the sanctions authorities in the Sergei Magnitsky Act aimed at the treatment of whistleblowers and human rights defenders in Russia. The Global Magnitsky Act also authorizes the President to impose sanctions against government officials and associates around the world responsible for acts of significant corruption.

Of the 55 individuals designated pursuant to the Sergei Magnitsky Act, 40 are directly associated with the alleged crimes that Magnitsky uncovered and his subsequent ill-treatment and death. OFAC has designated another 13 individuals, all from Russia's Chechnya region, for human rights violations and killings in that region and for the 2004 murder of Paul Klebnikov, the American chief editor of the Russian edition of Forbes.17 Two designations target the suspected killers of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006.18

In December 2017, President Trump issued EO 13818 to implement the Global Magnitsky Act, in the process expanding the target for sanctions to include those who commit any "serious human rights abuse" around the world, not just human rights abuse against whistleblowers and human rights defenders.19 At the same time, the Administration issued the first 13 designations under the act; among them were two Russian citizens designated for their alleged participation in high-level corruption.20

|

Linking U.S.-Russia Trade to Human Rights The Sergei Magnitsky Act continues a U.S. foreign policy tradition that links U.S. trade with Russia to concerns about human rights. The act is part of a broader piece of legislation granting permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status to Russia. This legislation authorized the President to terminate the application to Russia of Title IV of the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618; 19 U.S.C. 2101 et seq.), pursuant to which Russia was denied PNTR status. The Trade Act originally imposed restrictions on trade with Russia's predecessor, the Soviet Union, due to its nonmarket economy and prohibitive emigration policies (the latter through Section 402, popularly cited as the Jackson-Vanik amendment). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, these trade restrictions formally continued to apply to Russia, even though the United States granted Russia conditional normal trade relations beginning in 1992. In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) with U.S. support. The United States subsequently had to grant Russia PNTR status or opt out of WTO "obligations, rules, and mechanisms" with respect to Russia (H.Rept. 112-632). This would have meant that the United States would not benefit from all of Russia's concessions.... Russia could impose WTO-inconsistent restrictions on U.S. banks, insurance companies, telecommunications firms, and other service providers, but not on those from other WTO members. Russia also would not be required to comply with WTO rules regarding SPS [sanitary and phytosanitary] standards, intellectual property rights, transparency, and agriculture when dealing with U.S. goods and services, and the U.S. government would likewise not be able to use the WTO's dispute settlement mechanism if Russia violates its WTO commitments (H.Rept. 112-632). Although the PNTR legislation enjoyed broad congressional support, some Members of Congress were reluctant to terminate the application to Russia of the Trade Act's Jackson-Vanik amendment, which helped champion the cause of Soviet Jewish emigration in the 1970s, without replacing it with new human rights legislation. According to one of the original Senate sponsors of the Sergei Magnitsky Act, Senator Benjamin Cardin, pairing the Sergei Magnitsky Act with the PNTR legislation "allowed us to get this human rights tool enacted" while "[giving] us the best chance to get the PNTR bill done in the right form." He elaborated that "today we close a chapter in the U.S. history on the advancing of human rights with the repeal ... of Jackson-Vanik. It served its purpose. Today, we open a new chapter in U.S. leadership for human rights with the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act" (Congressional Record, S7437, December 5, 2012). |

Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

Most OFAC designations of Russian individuals and entities have beenmaintains sanctions on Russia related to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, malicious cyber activities and influence operations (including election interference), use of chemical weapons, human rights abuses, use of energy exports as a coercive or political tool, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, support to the governments of Syria and Venezuela, and other activities.

11 “No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law Will Be Passed.” U.S. Constitution, Article I, §9, clause 3. 12 See out-of-print CRS Report R40826, Bills of Attainder: The Constitutional Implications of Congress Legislating Narrowly, available to congressional offices on request.

13 Other departments, bureaus, agencies, and offices of the executive branch also weigh in, but to a lesser extent. The Department of Homeland Security, Attorney General, and Federal Bureau of Investigation, for example, all might review decisions relating to visas; Customs and Border Protection has a role in monitoring imports; the Department of Energy has responsibilities related to export control of nuclear materials; and the National Security Council reviews foreign policy and national security determinations and executive orders as part of the interagency process.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 51 link to page 14 link to page 51 link to page 14 link to page 51 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

For an overview of Russia sanctions authorities and designations, see Appendix B.

Sanctions Related to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine OFAC has issued most U.S. sanctions designations of Russian individuals and entities in response to Russia'’s 2014 invasion and annexationoccupation of Ukraine'’s Crimea region and Russia's subsequent instigation of separatist conflict inparts of eastern Ukraine. In 2014, the Obama Administration said it would impose increasing costs on Russia, in coordination with the EU and others, until Russia "“abides by its international obligations and returns its military forces to their original bases and respects Ukraine'’s sovereignty and territorial integrity."21

”14

The United States has imposed sanctions related to Russia'’s invasion of Ukraine on more than 680 at least 735 individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft by placing them on OFAC'sthat OFAC has placed on its Specially Designated Nationals List (SDN) or Sectoral Sanctions Identification List (SSI) (see Table 1 andand Table B-1). The basis for most of these sanctions is a series of four executive orders (E.O.s 13660, 13661, 13662, and 13685) that President Obama issued in 2014.15 In addition. In addition to Treasury-administered sanctions, the Department of Commerce'Commerce’s BIS denies export licenses for military, dual-use, or energy-related goods to designated end users, most of which also are subject to Treasury-administered sanctions. The basis for these sanctions is mainly a series of four executive orders (EOs 13660, 13661, 13662, and 13685) that President Obama issued in 2014.22

Two of President Obama'’s Ukraine-related EOsE.O.s target specific objectionable behavior. EO E.O. 13660 provides for sanctions against those the President determines have undermined democratic processes or institutions in Ukraine; undermined Ukraine'’s peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity; misappropriated Ukrainian state assets; or illegally asserted governmental authority over any part of Ukraine. EOE.O. 13685 prohibits U.S. business, trade, or investment in occupied Crimea and provides for sanctions against those the President determines have operated in, or been the leader of an entity operating in, occupied Crimea.

The other two EOsE.O.s provide for sanctions against a broader range of targets. EOE.O. 13661 provides for sanctions against Russian government officials, those who offer them support, and those operating in the Russian arms sector. EOE.O. 13662 provides for sanctions against individuals and entities that operate in key sectors of the Russian economy, as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury.

Specially Designated Nationals

OFAC established four SDN listsprograms based on the four Ukraine-related EOsE.O.s: two lists for those found to have engaged in specific activities related to the destabilization and invasion of Ukraine, and two lists for broader groups of targets. As of January 20202022, OFAC has placed more than 390 designated at least 445 individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft onunder the four Ukraine-related SDN listsprograms (see Table 1 andand Table B-1).

OFAC has drawn on EO

OFAC draws on E.O. 13660 to designate individuals and entities for their role in destabilizing and invading Ukraine. Designees mainly include former Ukrainian officials (including ex- 14 White House, “Fact Sheet: Ukraine-Related Sanctions,” March 17, 2014. 15 The President declared that events in Ukraine constituted a national emergency in the first executive order; the subsequent three orders built on and expanded that initial declaration. E.O. 13660 must be extended annually to remain in force; the President extended it most recently on March 2, 2021. Executive Order (E.O.) 13660 of March 6, 2014, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine,” 79 Federal Register 13493; E.O. 13661 of March 16 [17], 2014, “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine,” 79 Federal Register 15535; E.O. 13662 of March 20, 2014, “Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine,” 79 Federal Register 16169; and E.O. 13685 of December 19, 2014, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons and Prohibiting Certain Transactions with Respect to the Crimea Region of Ukraine,” 79 Federal Register 77357.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 19 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

and invading Ukraine. Designees mainly include former Ukrainian officials (including ex-President Viktor Yanukovych and a former prime minister), de facto Ukrainian separatist officials in occupied Crimea and eastern Ukraine, Russia-based fighters and patrons, and associated companies or organizations.

OFAC has drawn on EO

OFAC draws on E.O. 13685 to designate primarily Russian or Crimea-based companies and subsidiaries that operate in occupied Crimea (including individuals and entities involved in construction and operation of the Russia-Crimea railway and a prison in Crimea known as a site of human rights abuses). In September 2019, OFAC drew on E.O.. In September 2019, OFAC also drew on EO 13685 to designate nine individuals, entities, and vessels for evading Crimea-related sanctions in furtherance of an illicit scheme to deliver fuel to Russian forces in Syria.

OFAC has drawn on EO 13661 and EO 13662

OFAC draws on E.O. 13661 (and, in some cases, E.O. 13662) to designate a wider circle of Russian government officials, members of parliament, heads of state-owned companies, other prominent businesspeople and associates, including individuals the Department of the TreasuryTreasury Department has considered part of Russian President Vladimir Putin's "’s “inner circle,"” and related entities.23

16

Pursuant to these E.O.s (and sometimes simultaneously pursuant to other authorities), OFAC also has designated officials and state-connected individuals and entities in response to other Russian activities, including malign influence operations worldwide and the poisoning and imprisonment of Russian opposition figure Alexei Navalny.

Among the designated government officials and heads of state-owned companies are Russia's ’s minister of internal affairs, prosecutor general, and Security Council secretary,; directors of the Federal Security Service (FSB), Foreign Intelligence Service and(SVR), National Guard Troops, and the Federal Penitentiary Service; the chairs of both houses of parliament; and the chief executive officers of state-owned oil company Rosneft, gas company Gazprom, defense and technology conglomerate Rostec, and banks VTB and Gazprombank. OFAC also has drawn on EOE.O. 13661 to designate four Russian border guard officials for their role in Russia's Novembera 2018 attack against Ukrainian naval vessels and their crew in the Black Sea near occupied Crimea.

OFAC has designated several politically connected Russian billionaires (whom the Department of the Treasury refers to as oligarchs) and companies they own or control under EO 13661 and EO 13662.24E.O. 13661 or E.O. 13662.17 Designees include 9 of Russia'’s wealthiest 100 individuals, including 34 of the top 20, as estimated in 2021 by Forbes.2518 Of these 9 nine billionaires, 5five were designated in April 2018 as "“oligarchs … who profit from [Russia'’s] corrupt system."26 Under EO 13661, OFAC also ”19

Under E.O. 13661 and other authorities, OFAC has designated Yevgeny Prigozhin, a wealthy state-connected businessperson alleged to be a lead financial backer of private military companies operating in Ukraine, Syria, and other countries. Prigozhin is also designated under other authorities for election interference operations in the United States and elsewhere.

The entities OFAC has designated include(PMCs) that have operated in Ukraine and elsewhere (see “Prigozhin Network” below). These PMCs include the Wagner Group, also subject to U.S. sanctions.

OFAC has designated other holdings owned or controlled by SDNs. These holdings include Bank Rossiya, which the Department of the TreasuryTreasury Department has described as the "“personal bank"” of Russian senior officials;2720 other privately held banks and financial services companies (e.g., SMP Bank and the

16 See, for example, U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Russian Officials, Members of the Russian Leadership’s Inner Circle, And An Entity For Involvement In The Situation In Ukraine,” press release, March 20, 2014. 17 E.O. 13661, for being a Russian government official or supporting a senior government official, and E.O. 13662, for operating in the energy sector.

18 “The World’s Billionaires,” Forbes, 2021, at https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/#version:static_country:Russia. 19 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Designates Russian Oligarchs, Officials, and Entities in Response to Worldwide Malign Activity,” press release, April 6, 2018.

20 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Russian Officials, Members Of The Russian Leadership’s Inner Circle, And An Entity For Involvement In The Situation In Ukraine,” press release, March 20, 2014.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 29 U.S. Sanctions on Russia

other privately held banks and financial services companies (e.g., SMP Bank and the Volga Group); gas pipeline construction company Stroygazmontazh; construction company Stroytransgaz; and vehicle manufacturer GAZ Group. Private aluminum company Rusal, electric company EuroSibEnergo, and the related En+ Group were delisted in January 2019 after being designated in April 2018the year before (for more, see "“Section 241 "Oligarch" List").

“Oligarch” List and Related Sanctions,” below). Designated entities also include several defense and arms firms, such as the state-owned United Shipbuilding Corporation, Almaz-Antey (air defense systems and missiles), Uralvagonzavod (tanks and other military equipment), NPO Mashinostroyenia (missiles and rockets), and several subsidiaries of the state-owned defense and hi-tech conglomerate Rostec, including the Kalashnikov Group (firearms).

Sectoral Sanctions Identifications

Prior to April 2018, OFAC used EO 13662 solely

OFAC has used E.O. 13662 mainly as the basis for identifying entities for inclusion on the SSI List. Individuals and entities under U.S. jurisdiction are restricted from engaging in specific transactions with entities on the SSI List, which OFAC identifies as subject to one of four directives under the EOE.O. SSI restrictions apply to new equity investment and financing (other than 14-day lending) for identified entities in Russia'’s financial sector (Directive 1); new financing (other than 60-day lending) for identified entities in Russia'’s energy sector (Directive 2); and new financing (other than 30-day lending) for identified entities in Russia'’s defense sector (Directive 3).2821 A fourth directive prohibits U.S. trade with identified entities related to the development of Russian deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale projects that have the potential to produce oil and, amended as a result of requirements enacted in CRIEEA in 2017, such projects worldwide in which those entities have an ownership interest of at least 33% or a majority of voting interests.

As of January 20202022, OFAC has placed 13 major Russian companies and more than 275 of their subsidiaries and affiliates on the SSI List. The SSI List includes major state-owned companies in the financial, energy, and defense sectors; it does not include all companies in those sectors. The parent entities on the SSI List, under their respective directives, consist of the following:

Four Five large state-owned banks:(Sberbank, VTB Bank, Gazprombank,Rosselkhozbank)Rosselkhozbank, and VEB (rebranded VEB.RF in 2018), which"“acts as a development bank and payment agent for the Russian government";29- ”;22

State-owned oil companies Rosneft and Gazpromneft, pipeline company

Transneft, and private gas producer Novatek;

- State-owned defense and hi-tech conglomerate Rostec; and

- For restrictions on transactions related to deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale oil

projects, Rosneft and Gazpromneft, private companies Lukoil and Surgutneftegaz, and state-owned energy company Gazprom (Gazpromneft

's’s parent company). 21 Directive 1 has been amended twice to narrow lending windows from, initially, 90 days (July 2014) to 30 days (September 2014) to 14 days (September 2017). The lending window in Directive 2 has been narrowed once, from 90 days (July 2014) to 60 days (September 2017). Directives are available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Pages/ukraine.aspx. 22 The Administration also designated the Bank of Moscow, which later became a subsidiary of VTB Bank. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Announcement of Treasury Sanctions on Entities Within the Financial Services and Energy Sectors of Russia, Against Arms or Related Materiel Entities, and those Undermining Ukraine’s Sovereignty,” press release, July 16, 2014. Congressional Research Service 9 link to page 14 link to page 32 link to page 58 U.S. Sanctions on Russiaparent company).

|

Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine: A Chronology U.S. sanctions related to Russia's invasion of Ukraine have evolved from 2014 to the present. From March to June 2014, OFAC made designations based on EOs 13660 (March 6, 2014) and 13661 (March 17, 2014). OFAC announced initial designations on March 17, 2014, the day after Crimea's de facto authorities organized an illegal referendum on secession. OFAC announced a second round of designations on March 20, the day before Russia officially claimed to annex Crimea. OFAC made three more rounds of designations through June 2014. Before July 2014, the Obama Administration did not invoke EO 13662 (March 20, 2014), which established a means to impose sectoral sanctions. An Administration official characterized the introduction of EO 13662 as a signal to Russia that if Moscow "further escalates this situation [it] will be met with severe consequences." The official explained that "this powerful tool will allow us the ability to calibrate our pressure on the Russian government" (The White House, "Background Briefing on Ukraine by Senior Administration Officials," March 20, 2014). On July 16, 2014, as the conflict in eastern Ukraine escalated and congressional pressure for a stronger U.S. response mounted, the Obama Administration announced the first round of sectoral sanctions on selected Russian financial services and energy companies through the issuance of two directives specifying a narrower set of sanctions than those EO 13662 had authorized. On the basis of the previous EOs, OFAC also made additional designations. The next day, Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17, a commercial aircraft en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur, was shot down over eastern Ukraine. All 298 passengers and crew aboard were killed, including 193 Dutch citizens and 18 citizens of other EU countries. Intelligence sources indicated that separatist forces had brought down the plane using a missile supplied by the Russian military. The MH17 tragedy helped galvanize EU support for sectoral sanctions on Russia similar to those the United States had imposed (for more, see "U.S. and EU Ukraine-Related Sanctions Compared," below). In coordination with the EU, the Obama Administration expanded sectoral sanctions in the wake of the MH17 tragedy. The Administration announced two more rounds of designations in July and September 2014, the second time together with two new directives that imposed sectoral sanctions on Russian defense companies and certain oil development projects. On December 19, 2014, President Obama issued a fourth Ukraine-related executive order (EO 13685). The same day, OFAC issued a new round of designations. The Obama Administration announced six more rounds of designations under the Ukraine-related EOs. The Trump Administration has made eight rounds of designations under these EOs, most recently in September 2019. In the April 2018 round, OFAC used the relatively broad authorities of EOs 13661 and 13662 to designate 24 Russian government officials and politically connected billionaires "in response to [Russia's] worldwide malign activity." |

Ukraine-Related Legislation

Ukraine-Related Legislation

In addition to issuing four Ukraine-related executive orders in 2014, President Obama signed into law the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act (SSIDES) on April 3, 2014, and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act (UFSA) on December 18, 2014. SSIDES was introduced in the Senate on March 12, 2014, six days after President Obama issued the first Ukraine-related EOE.O., declaring a national emergency with respect to Ukraine. The President signed UFSA into law the day before he issued his fourth Ukraine-related EO, E.O., prohibiting trade and investment with occupied Crimea. CRIEEA, which President Trump signed into law on August 2, 2017, amended SSIDES and UFSA (for more on CRIEEA, see ", among other measures (see Table 1 and “Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017," below).

” text box, below).

Both SSIDES and UFSA expandedexpand on the actions the Obama Administration took in response to Russia'Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. President Obama did not cite SSIDES or UFSA as an authority for designations or other sanctions actions, however.23 The Trump Administration issued three human rights-related designations pursuant to SSIDES.

designations or other sanctions actions.30 In November 2018, President Trump cited SSIDES, as amended by CRIEEA (Section 228), to designate two Ukrainian individuals and one entity for committing serious human rights abuses in territories forcibly occupied or controlled by Russia. President Trump has not cited UFSA as an authority for any sanctions designations.

Some sanctions authorities in SSIDES and UFSA overlap with steps taken by the President in issuing executive ordersE.O.s under emergency authorities. Many individuals and entities OFAC designated for their role in destabilizing Ukraine, for example, could have been designated pursuant to SSIDES. Similarly, some of the individuals OFAC designated in April 2018 as "“oligarchs and elites who profit from [Russia'’s] corrupt system"” potentially could have been designated pursuant to the authority in SSIDES that provides for sanctions against those responsible for significant corruption.3124 In addition, Russian arms exporter Rosoboronexport, subject to sanctions under UFSA, is subject to sanctions under other authorities (see "“Weapons Proliferation").

”).

SSIDES and UFSA contain additional sanctions provisions that the executive branch could use. These include sanctions against Russian individuals and entities for corruption, arms transfers to Syria and separatist territories, and energy export cutoffs. They also include potentially wide-reaching secondary sanctions against foreign individuals and entities that facilitate significant transactions for Russia sanctions designees, help them to evade sanctions, or make significant investments in certain oil projects in Russia (for details, see Appendix C).

Table 1. U.S. Sanctions Related to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

(authorities, targets, and Treasury designees)

Designations

Authorities

Targets

(as of 1/2022)

Executive Order (E.O.)

Those responsible for undermining Ukraine’s democracy;

128 individuals, 24

13660; Countering

threatening its peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or

entities

Russian Influence in

territorial integrity; misappropriating assets; and/or il egally

Europe and Eurasia Act asserting government authority. of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44, Title II; 22 U.S.C. 9501 et seq.)

23 In his signing statement, President Obama said the Administration did “not intend to impose sanctions under this law, but the Act gives the Administration additional authorities that could be utilized, if circumstances warranted.” White House, “Statement by the President on the Ukraine Freedom Support Act,” December 18, 2014. 24 U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Designates Russian Oligarchs, Officials, and Entities in Response to Worldwide Malign Activity,” press release, April 6, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

10

U.S. Sanctions on Russia

Designations

Authorities

Targets

(as of 1/2022)

E.O. 13661; P.L. 115-44 Russian government officials; those operating in Russia’s arms 109 individuals, 78

or related materiel sector; entities owned or control ed by a

entities, 3 aircraft, 1

investments in certain oil projects in Russia (for details, see text box entitled "Sanctions in Ukraine-Related Legislation," below).

|

Sanctions in Ukraine-Related Legislation Enacted in April 2014, SSIDES requires the imposition of sanctions on those the President finds to have been responsible for violence and human rights abuses during antigovernment protests in Ukraine in 2013-2014 and for having undermined Ukraine's peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity. In addition, it requires the imposition of sanctions on Russian government officials, family members, and close associates the President finds to be responsible for acts of significant corruption in Ukraine. It also initially authorized, but did not require, the President to impose restrictions on Russian government officials and associates responsible for acts of significant corruption in Russia. In 2017, CRIEEA amended SSIDES to require the President to impose sanctions on Russian government officials and associates responsible for acts of significant corruption worldwide and those responsible for "the commission of serious human rights abuses in any territory forcibly occupied or otherwise controlled" by the Russian government. It also amended SSIDES to introduce secondary sanctions against foreign individuals and entities that help evade sanctions provided for in Ukraine-related or cyber-related EOs, SSIDES, or UFSA, or that facilitate significant transactions for individuals (and their family members) and entities subject to any sanctions on Russia. Enacted in December 2014, UFSA requires the President to impose sanctions on Russian state arms exporter Rosoboronexport and requires sanctions on Russian entities that transfer weapons to Syria or, without consent, Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and potentially other countries that the President designates as countries of significant concern. UFSA also initially authorized the President to impose secondary sanctions on foreign individuals and entities that make a significant investment in deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale oil projects in Russia (a provision similar to the restrictions OFAC established in September 2014 but targeted against third parties). In addition, it initially authorized the President to impose secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that facilitate significant transactions related to defense- and energy-related transactions subject to UFSA sanctions or for individuals and entities subject to sanctions under UFSA or Ukraine-related EOs. In 2017, CRIEEA amended UFSA to require the President to impose sanctions on (1) foreign individuals and entities that make significant investments in deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale oil projects in Russia and (2) foreign financial institutions that facilitate significant transactions related to defense- and energy-related transactions subject to UFSA sanctions, or for individuals and entities subject to sanctions under UFSA or Ukraine-related EOs. Finally, UFSA provides for sanctions against state-owned energy company Gazprom, if it is found to withhold significant natural gas supplies from NATO member states or countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. |

Table 1. U.S. Sanctions Related to Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

(authorities, targets, and Treasury designees)

|

Authorities |

Targets |

Designations (as of 1/2020) |

|

Executive Order (EO) 13660; Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44, Title II; 22 U.S.C. 9501 et seq.) |

Those responsible for undermining Ukraine's democracy; threatening its peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity; misappropriating assets; and/or illegally asserting government authority. |

116 individuals, 24 entities |

|

EO 13661; P.L. 115-44 |