Foreign Assistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy

Changes from April 16, 2019 to April 30, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Foreign AidAssistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy

Contents

- Foreign

AidAssistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy - How Is "U.S. Foreign

AidAssistance" Defined and Counted? - Foreign Aid Purposes and Priorities

- What Are the Rationales and Objectives of U.S. Foreign Assistance?

- Rationales for Foreign Aid

- Objectives of Foreign Aid

- What Are the Major Foreign Aid Funding Categories and Accounts?

- Bilateral Development Assistance

- Multilateral Development Assistance

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Assistance Serving Both Development and Special Political/Strategic Purposes

- Nonmilitary Security Assistance

- Military Assistance

- Delivery of Foreign Assistance

- What Executive Branch Agencies Implement Foreign

AidAssistance Programs? - U.S. Agency for International Development

- U.S. Department of Defense

- U.S. Department of State

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- U.S. Department of the Treasury

- Millennium Challenge Corporation

- Other Agencies

- What Are the Different Forms in Which Assistance Is Provided?

- Cash Transfer

- Commodities

- Economic Infrastructure

- Training

- Expertise

- Small Grants

How Much AidExpertise- Grants

- In-Kind Goods

- Economic Infrastructure

- Direct Budget Support

How Much Assistance Is Provided as Loans and How Much as Grants? What Are Some Types of Loans? Have Loans Been Repaid? Why Is Repayment of Some Loans Forgiven?- Loan/Grant Composition

- Loan Guarantees

- Loan Repayment

- Debt Forgiveness

- What Are the Roles of Government and Private Sector in Development and Humanitarian

AidAssistance Delivery? - Which Countries Receive U.S. Foreign

AidAssistance? - Foreign Aid Spending

- How Large Is the U.S. Foreign Assistance Budget?

- What Does Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) Mean?

- How Much of Foreign

AidAssistance Dollars Are Spent on U.S. Goods and Services? - How Does the United States Rank as a Donor of Foreign Aid?

- Congress and Foreign

AidAssistance

- What Congressional Committees Oversee Foreign Aid Programs?

- What Are the Major Foreign Aid Legislative Vehicles?

Figures

- Figure 1.

FY2017FY2018 Aid Program Composition - Figure 2. Foreign

AidAssistance Implementing Agencies,FY2017FY2018

- Figure 3.

AidAssistance by Type,2017FY2018 Obligations - Figure 4. Regional Distribution of

Aid, FY1997, FY2007, and FY2017Assistance, FY1998, FY2008, and FY2018

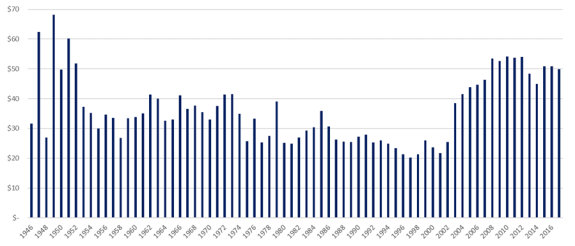

Figure 5. - Figure 5. U.S. Foreign Aid: FY1946-FY2017 Estimate

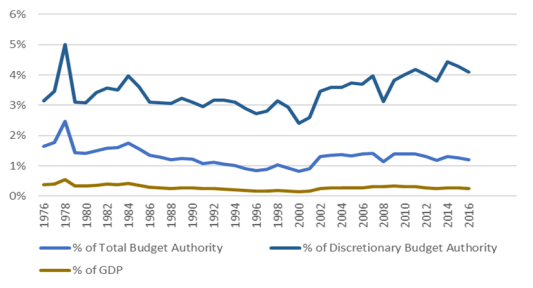

Figure 6.Aid as a Percentage of the Federal Budget and GDP,- Figure

76. ForeignAidAssistance Funding Trends,FY1977-FY2017FY1976-FY2018 Estimate- Figure 7. Overseas Contingency Operations, FY2012-FY2020

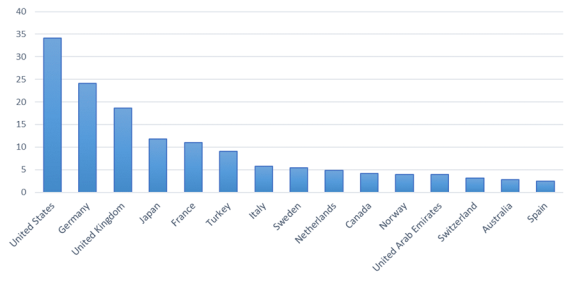

Estimate - Figure 8. Top 15 Bilateral Donors of Official Development Assistance,

20172018

Tables

Summary

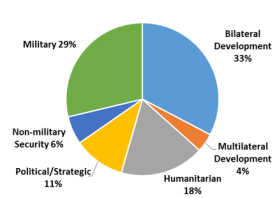

Foreign assistance is the largest component of the international affairs budget and is viewed by many Members of Congress as an essential instrument of U.S. foreign policy. On the basis of national security, commercial, and humanitarian rationales, U.S. assistance flows through many federal agencies and supports myriad objectives. These objectives include promoting economic growth, reducing poverty, improving governance, expanding access to health care and education, promoting stability in conflict regions, countering terrorism, promoting human rights, strengthening allies, and curbing illicit drug production and trafficking. Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, foreign aid has increasingly been associated with national security policy. At the same time, many Americans and some Members of Congress view foreign aid as an expense that the United States cannot afford given current budget deficits.

In FY2017FY2018, U.S. foreign assistance, defined broadly, totaled an estimated $49.8746.89 billion, or 1.2% of total federal budget authority. About 4443% of this assistance was for bilateral economic development programs, including political/strategic economic assistance; 35% for military aid and nonmilitary security assistance; 18% for humanitarian activities; and 4% to support the work of multilateral institutions. Assistance can take the form of cash transfers, equipment and commodities, infrastructure, education and training, or technical assistance, and, in recent decades, is provided almost exclusively on a grant rather than loan basis. Most U.S. aid is implemented by nongovernmental organizations rather than foreign governments. The United States is the largest foreign aid donor in the world, accounting for about 2420% of total official development assistance from major donor governments in 20172018 (the latest year for which these data are available).

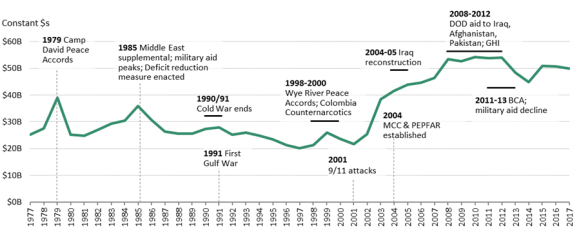

Key foreign assistance trends in the past decadesince 2001 include growth in development aid, particularly global health programs; increased security assistance directed toward U.S. allies in the anti-terrorism effort; and high levels of humanitarian assistance to address a range of crises. Adjusted for inflation, annual foreign assistance funding over the past decade was the highest it has beensince 2001 has been its highest since the Marshall Plan in the years immediately following World War II. In FY2017FY2018, Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, and Iraqand Egypt received the largest amounts of U.S. aidassistance, reflecting long-standing aid commitments to Israel and Egypt, the strategic significance of Afghanistan and Iraq, and the strategic and humanitarian importance of Jordan as the crisis in neighboring Syria continues. The Near East regionSub-Saharan Africa received 2726% of aidassistance allocated by country or region in FY2017FY2018, followed by the Middle East and North Africa, at 2524%, and South and Central Asia, at 1517%. This was a significant shift from a decade prior, when sub-Saharan Africa received 19% of aid and the NearMiddle East 34and North Africa 30%, reflecting significant increases in HIV/AIDS-related and humanitarian assistance programs concentrated in Africa between FY2007 and FY2017FY2008 and FY2018 and the drawdown of U.S. military forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military assistance to Iraq began to decline starting in FY2011, but growing concern about the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has reversed this trend.

This report provides an overview of the U.S. foreign assistance program by answering frequently asked questions on the subject. It is intended to provide a broad view of foreign assistance over time, and will be updated periodically. For more current information on foreign aid funding levels, see CRS Report R45168R45763, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs: FY2019FY2020 Budget and Appropriations, by Susan B. EpsteinCory R. Gill, Marian L. Lawson, and Cory R. GillEmily M. Morgenstern.

Foreign AidAssistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy

U.S. foreign aidassistance (also commonly called foreign aid—the two terms are used interchangeably in this report) is the largest component of the international affairs budget, for decades viewed by many Members of Congress as an essential instrument of U.S. foreign policy.1 Each year, the foreign aid budget is the subject of congressional debate over the size, composition, and purpose of the program. The focus of U.S. foreign aid policy has been transformed since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Global development, a major objective of foreign aid, has been cited as a third pillar of U.S. national security, along with defense and diplomacy, in the national security strategies of the George W. Bush and Barack Obama Administrations. Although the Trump Administration's National Security Strategy does not explicitly address the status of development vis-à-vis diplomacy and defense, it does note the historic importance of aid in achieving foreign policy goals and supporting U.S. national interests.2

This report addresses a number of the more frequently asked questions regarding the U.S. foreign aid programSince the European Recovery Program (better known as the Marshall Plan) helped rebuild Europe after World War II, in an effort to bolster the economy of postwar Europe, prevent the expansion of communism, and jumpstart world trade, modern U.S. foreign assistance programs have continually evolved to reflect changing foreign policy strategy, global challenges, and U.S. domestic priorities.2 The Cold War emphasis on containing communism was replaced by regional development priorities and a focus on counter-narcotics assistance in the 1990s. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, a large portion of U.S. assistance focused on counterterrorism programs and efforts related to U.S. military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan. At the same time, global health assistance expanded significantly to address the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. More recently, foreign assistance policy has focused on competing with China and Russia and addressing protracted global humanitarian crises. Each year, the size, composition, and purpose of foreign assistance programs are considered by Congress, primarily through the appropriations process.

This report addresses a number of the more frequently asked questions regarding U.S. foreign assistance; its objectives, costs, and organization; the role of Congress; and how it compares to those of other aid donors. It attempts not only to present a current snapshot of American foreign assistance, but also to illustrate the extent to which this instrument of U.S. foreign policy has evolved over time.

Data presented in the report are the most current, consistent, and reliable figures available, generally updated through FY2017FY2018. Dollar amounts come from a variety of sources, including the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Foreign Aid Explorer database (Explorer) and annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations acts. As new data are obtained or additional issues and questions arise, the report will be revised.

Foreign aidassistance abbreviations used in this report are listed in Appendix B.

How Is "U.S. Foreign AidAssistance" Defined and Counted?

In its broadest sense, U.S. foreign aidassistance, or foreign aid, is defined under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195, FAA), the primary legislative basis of foreign aidthese programs, as

any tangible or intangible item provided by the United States Government [including "by means of gift, loan, sale, credit, or guaranty"] to a foreign country or international organization under this or any other Act, including but not limited to any training, service, or technical advice, any item of real, personal, or mixed property, any agricultural commodity, United States dollars, and any currencies of any foreign country which are owned by the United States Government.... (§634(b))

For many decades, nearly all assistance annually requested by the executive branch and debated and authorized by Congress was ultimately encompassed in the foreign operations appropriations3 (currently within the Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs [SFOPS] appropriations measure but before FY2008, housed in the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs appropriations measure) and the international food aid title of the agriculture appropriations.3 In the U.S. federal budget, the 150 (international affairs) budget function has subsumed these traditional foreign aid accounts have been subsumed under the 150 (international affairs) budget function.

By the 1990s, howeverassistance accounts.4 The SFOPS bill and Function 150 budget also include State Department diplomatic and related programs, which are not considered foreign assistance.

By the 1990s, it became increasingly apparent that the scope of U.S. foreign aidassistance was not fully accounted for by the total of the foreign operations and international food aid appropriations. Many U.S. departments and agencies had adopted their own assistance programs, funded out of their own budgets and commonly in the form of professional exchanges with counterpart agencies abroad—the Environmental Protection Agency, for example, providing water quality expertise to other governments. These aid. These assistance efforts, conducted outside the purview of the traditional foreign aid authorizing and appropriations committees, grew more substantial and varied in the mid-1990s. The Department of Defense (DOD) Nunn-Lugar effort provided billions in aid to secure and eliminate nuclear and other weapons, as did Department of Energy activities to control and protect nuclear materials—both aimed largely at the former Soviet Union. Growing participation by DOD in health and humanitarian efforts and expansion of health programs in developing countries by the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, especially in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, followed.

During the past 15 yearsIn the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, and the subsequent U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, DOD-funded and implemented aid programs in Iraq and Afghanistan to train and equip foreign forces and win hearts and minds through development efforts were oftenhave at times been considerably larger than the traditionalother military and development assistance programs provided under the foreign operations appropriations. The recent decline in DOD activities in these countries has sharply decreased nontraditional aid funding. In FY2011, nontraditional sources of assistance, at $17.3 billion, represented 35% of total aid obligations. By FY2017, nontraditional aid, at $9.7 billion, represented 19% of total aid, still a significant proportion.

While the executive branch has continued to request and Congress to debate

While the executive branch requests and Congress debates most foreign aid within the parameters of the foreign operations legislation, both entitiesSFOPS appropriation, both branches of government have sought to ascertain a fuller picture of assistance programs through improved data collection and reporting. Significant discrepancies remain between data available for traditional versus nontraditionaldifferent types of aid and, therefore, the level of analysis applied to each. (See text box, "A Note on Numbers and Sources," below.) Nevertheless, to the extent possible, this report tries to capture the broadest definition of aid throughout.

|

A Note on Numbers and Sources Previous versions of this report presented numeric measures of foreign assistance from a variety of sources, including the Budget of the United States' historical tables, USAID's Foreign Aid Explorer database (Explorer), the State Department's ForeignAssistance.gov website, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD) Official Development Assistance (ODA) website. Different sources are necessary for comprehensive analysis, but can often lead to inconsistencies from table to table or chart to chart. This report uses data from only two of these sources. This reflects both an effort to ensure consistency in calculations, as well as improved coordination and consolidation of data between the State Department and USAID as a result of the Foreign Aid Transparency and Accountability Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-191). In using only two sources, there is less variation in data, but differences remain with respect to definitions of foreign assistance used by different sources, including:

Apparent discrepancies also arise due to funding being recorded at different points in the process. Explorer reports funds For the purposes of this report, CRS primarily uses the FAA definition of aid, as reported in Explorer in the form of obligations. ODA data are only used in the section comparing U.S. assistance levels to those of other donor countries. For more recent data on foreign aid funded through the SFOPS appropriation—including |

Foreign Aid Purposes and Priorities

What Are the Rationales and Objectives of U.S. Foreign Assistance?

Foreign assistance is predicated on several rationales and supports a great many objectives. The importance and emphasis of various rationales and objectives have changed over time.

Rationales for Foreign Aid

Throughout the past 70 years, there have been three key rationales for foreign assistance

- :National Security

has been the. The predominant theme of U.S. assistance programs has been national security. From rebuilding Europe after World War II under the Marshall Plan (1948-1951) andthroughthroughout the Cold War, policymakers have viewed U.S. aid programswere viewed by policymakersas a way to prevent the incursion of communist influence and secure U.S. base rights or other support in the anti-Soviet struggle. After the Cold War ended, the focus of foreign aid shifted from global anti-communism to disparate regional issues, such as Middle East peace initiatives, the Development Fund for Africa, the transition to democracy of eastern Europe and republics of the former Soviet Union, and international illicit drug production and trafficking in the Andes. Without an overarching security rationale, foreign aid budgets decreased in the 1990s. However,sinceafter the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States, policymakers frequentlyhavecast foreign assistance as a tool in U.S. counterterrorism strategy, increasing aid to partner states in counterterrorism efforts and funding the substantial reconstruction programs in Afghanistan and Iraq.As noted, global development has been featured as a key element in U.S. national security strategy in both Bush and Obama Administration policy statements.More recently, policymakers have viewed foreign assistance as a tool to counter the global influence of nations that may threaten U.S. security interests, including China, Russia and Iran.

- Commercial Interests. Foreign assistance has long been defended as a way to either promote U.S. exports by creating new customers for U.S.

productsgoods and services or by improving the global economic environment in which U.S. companies compete. Among the objectives of the aforementioned Marshall Plan was to reestablish the capacity of European countries to be U.S. trade partners.

- Humanitarian Concerns. Humanitarian concerns drive both short-term assistance in response to crisis and disaster as well as long-term development assistance aimed at reducing poverty,

hungerfighting disease, and other forms of human suffering brought on by more systemic problems. Providing assistance for humanitarian reasons has generally been the aid rationale most broadly supported by the American public and policymakers alike.

Objectives of Foreign Aid

The objectives of aid generally fit within these rationales. Aid objectives include promoting economic growth and reducing poverty, improving governance, addressing population growth, expanding access to basic education and health care, protecting the environment, promoting stability in conflictive regions, protecting human rights, promoting trade, curbing weapons proliferation, strengthening allies, and addressing drug production and trafficking. The expectation has been that, by meeting these and other aid objectives, the United States will achieve its national security goals as well as ensure a positive global economic environment for American products, and demonstrate benevolent and respectable global leadership.

Different types of foreign aid typically support different objectives. But there is also considerable overlap among categories of aid. Multilateral aid serves many of the same objectives as bilateral development assistance, although through different channels. Military assistance, economic security aid—including rule of law and police training—and development assistance programs may support the same U.S. political objectives in the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Military assistance and alternative development programs are integrated elements of American counternarcotics efforts in Latin America and elsewhere.

Depending on how they are designed, individual assistance projects can also serve multiple purposes. A health project ostensibly directed at alleviating the effects of HIV/AIDS by feeding orphan children may also stimulate grassroots democracy and civil society through support of indigenous NGOs while additionally meeting U.S. humanitarian objectives. Microcredit programs that support small business development may help develop local economies while at the same time enabling client entrepreneurs to provide food and education to their children. Water and sanitation improvements both mitigate health threats and stimulate economic growth by saving time previously devoted to water collection, raising school attendance for girls, and facilitating tourism, among other effects.

In 2006, in an effort to rationalize the assistance program more clearly, the State Department developed a framework that organizes U.S. foreign aid around five strategic objectives, each of which includes a number of program elements, also known as sectors. The five objectives are Peace and Security; Investing in People; Governing Justly and Democratically; Economic Growth; and Humanitarian Assistance. Generally, these objectives and their sectors do not correspond to any one particular budget account in appropriations bills.56 Annually, the Department of State and USAID develop their foreign operations budget request within this framework, allowing for an objective and program-oriented viewpoint for those who seek it. An effort by the State Department to obtain reporting from all departments and agencies of the U.S. government on aid levels categorized by objective and sector is ongoing.6 USAID's Explorer website (explorer.usaid.gov) currently provides a more complete picture of funds obligated for each objective from all parts of the U.S. government (see Table 1).

Table 1. Foreign Assistance from All Sources, by Objective and Program Area: FY2017

(obligations in millions of current U.S. $dollars)

|

Aid Objectives and Program Areas |

FY2017 |

Aid Objectives and Program Areas |

FY2017 |

|||||||||||

|

Peace and Security |

16,916.90

|

Investing in People |

11,287.50

|

|||||||||||

|

Counterterrorism |

473.27 |

Health |

10,013.97 |

|||||||||||

|

Combating Weapons of Mass Destruction |

383.25 |

Education |

1,031.59

|

Health

|

Combating Weapons of Mass Destruction

|

Education

|

||||||||

|

Stabilization/Security Sector Reform |

12,239.44

|

Social Services |

241.94

|

|||||||||||

|

Counternarcotics |

411.89 | |||||||||||||

|

Transnational Crime |

73.60

|

Transnational Crime

|

Governing Justly & Democratically |

2,831.50

|

||||||||||

|

Conflict Mitigation |

302.09

|

Rule of Law & Human Rights |

1,591.02

|

|||||||||||

|

Peace and Security - General |

3,033.36

|

Good Governance |

751.68

|

|||||||||||

| |

Political Competition |

146.38 |

||||||||||||

|

Promoting Economic Growth |

4,633.89

|

Political Competition

|

Promoting Economic Growth

|

Civil Society |

328.16

|

|||||||||

|

Macroeconomic Growth |

465.38

|

Democracy and Governance - General |

14.25

|

|||||||||||

|

Trade & Investment |

115.85 | |||||||||||||

|

Financial Sector |

86.72 |

Humanitarian Assistance |

8,661.94 |

|||||||||||

|

Infrastructure |

706.20 |

Protection, Assistance & Solutions |

8,322.71 |

|||||||||||

|

Agriculture |

1,196.91 |

Disaster Readiness |

189.80 |

|||||||||||

|

Private Sector Competitiveness |

424.92 92 |

Migration Management |

149.43 |

|||||||||||

|

Economic Opportunity |

69.70 |

|||||||||||||

|

Environment |

1,451.71 |

Program Management |

3,423.69 |

|||||||||||

|

Labor, Mining, General Economic Growth |

116.48 |

Multi-Sector |

2,184.35 |

Source: USAID Explorer and CRS calculations.

Note: A similar framework table is included in annual SFOPS congressional budget justifications, and includes only funding in the international affairs (function 150) budget.

What Are the Major Foreign Aid Funding Categories and Accounts?

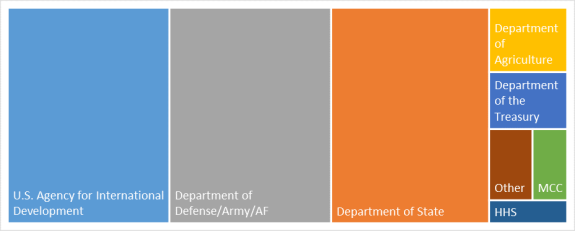

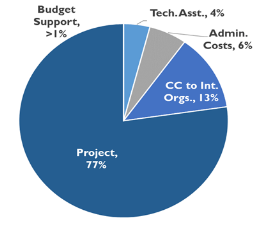

The 2006 framework introduced by the Department of State organizes assistance by foreign policy strategic objective and sector. But there are many other ways to categorize foreign aid, one of which is to sort out and classify foreign aid accounts in the U.S. budget according to the types of activities they are expected to support, using broad categories such as military, bilateral development, multilateral development, humanitarian assistance, political/strategic, and nonmilitary security activities (see Figure 1). This methodology reflects the organization of aid accounts within the SFOPS appropriations but can easily be applied to the international food aid title of the Agriculture appropriations as well as to the DOD and other government agency assistance programs with funding outside traditional foreign aid budget accounts. In FY2017, these many aid accounts provided $49.9 billion in obligated assistance.7

|

|

|

Source: USAID Explorer and CRS calculations. |

Bilateral Development Assistance

For FY2017, U.S. government departments and agencies obligated about $16.2 billion in bilateral development assistance, or 33% of total foreign aid, primarily through the Development Assistance (DA) and Global Health (Global Health-USAID and Global Health-State) accounts and the administrative accounts that allow USAID to operate (Operating Expenses, Capital Investment Fund, and Office of the Inspector General). Other bilateral development assistance accounts support the development efforts of distinct institutions, such as the Peace Corps, Inter-American Foundation (IAF), U.S.-African Development Foundation, Trade and Development Agency, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Policies, Regulations, and Systems

Financial Sector

Infrastructure

Humanitarian Assistance

Agriculture

Protection, Assistance & Solutions

Private Sector Competitiveness

Disaster Readiness

Economic Opportunity

Humanitarian Assistance - General

Environment

Labor, Mining, General Economic Growth

International Contributions

Program Management

Multi-Sector

Source: USAID Explorer and CRS calculations. Note: Figures represent net obligations and are negative in cases where de-obligated funds exceed new obligations. A similar framework table is included in annual SFOPS congressional budget justifications, and includes only funding in the international affairs (function 150) budget. Characterizing aid in this way may provide an incomplete picture, as there is considerable overlap among aid categories and purposes. A health project directed at alleviating the effects of HIV/AIDS by feeding orphan children, for example, may also stimulate grassroots democracy and civil society through support of local NGOs. Microcredit programs that support small business development may at the same time enable client entrepreneurs to provide food and education to their children. Water and sanitation improvements may both mitigate health threats and stimulate economic growth by saving time previously devoted to water collection, raising school attendance for girls and facilitating tourism, among other effects.

Source: USAID Explorer and CRS calculations. For FY2018, U.S. government departments and agencies obligated about $15.4 billion (33% of total foreign aid) for bilateral development assistance, which is generally intended to improve the economic development and welfare of poor countries. USAID and the State Department jointly implement the majority of bilateral development assistance, administering the Development Assistance (DA) and Global Health (Global Health-USAID and Global Health-State) accounts and the Operating Expenses account that allows USAID to operate. Other bilateral development assistance accounts support the development efforts of distinct agencies, such as the Peace Corps, Inter-American Foundation (IAF), Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) among others. By far the largest portion of bilateral development assistance is devoted to global health. These programs include maternal and child health, family planning and reproductive health programs, and strengthening the government health systems that provide care. In recent months, addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries has become a global health priority. The largest share of funding, however, is directed toward treating and combatting the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. These funds are largely directed through the State Department's Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator to other agencies, including USAID and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The latter agency and the National Institutes for Health also conduct programs funded by Labor-Health and Human Services (HHS) appropriations.7 Bilateral development assistance programs also aim to foster sustainable broad-based economic progress and social stability in developing countries. USAID largely manages this aid to fund long-term projects in a wide range of areas. Many programs share the objective in the State Department framework of "promoting economic growth and prosperity":Development assistance programs aim to foster sustainable broad-based economic progress and social stability in developing countries. This aid is managed largely by USAID and is used for long-term projects in a wide range of areas. Many programs share the objective in the State Department framework of "promoting economic growth and prosperity." Agriculture programs focus on reducing poverty and hunger, trade-promotion opportunities for farmers, and sound environmental practices for sustainable agriculture. Private sector development programs include support for business associations

343 .36

101 .65

85 .75

-81 .50

8,345 .84

1,398 .54

8,040 .15

377 .86

92

239 .40

14 .86

66 .29

624 .05

77 .83

308 .94

3,214 .21

2,080 .02

Bilateral Development Assistance

and microfinance services. Programs for managing natural resources and protecting the global environment focus on conserving biological diversitybiodiversity; improving the management of land, water, and forests; encouraging clean and efficient energy production and use; and reducing the threat of global climate change.

Programs supportingwith the objective of "governing justly and democratically" include support for promoting rule of law and human rights, good governance, political competition, and civil society.

Programs with the objective of "investing in people" include support for basic, secondary, and higher education; improving government ability to provide social services; water and sanitation; and health care.

By far the largest portion of bilateral development assistance is devoted to global health. These programs include treatment of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases, maternal and child health, family planning and reproductive health programs, and strengthening the government health systems that provide care. Most funding for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis is directed through the State Department's Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator to other agencies, including USAID and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The latter agency and the National Institutes for Health also conduct programs funded by Labor-Health and Human Services (HHS) appropriations.8

In addition to providing emergency food aid in crisis situations, a portion (about 25% in FY2017) of the Food for Peace (FFP) Title II international food aid program (also referred to as P.L. 480, named after the 1954 law that authorized it)—funded under the Agriculture appropriations—provides nonemergency food commodities to private voluntary organizations (PVOs) or multilateral organizations, such as the World Food Program, for development-oriented purposes. FFP funds are also used to support the "farmer-to-farmer" program, which sends hundreds of U.S. volunteers as technical advisors to train farm and food-related groups throughout the world. In addition, the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program, a program begun in 2002, provides commodities, technical assistance, and financing for school feeding and child nutrition programs.9

Multilateral Development Assistance

A share of U.S. foreign assistance—4% in FY2017 ($2.1 billion)—is combined with contributions from other donor nations to finance multilateral development projects. Multilateral aid10 is funded largely through the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) account and individual accounts for each of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and global environmental funds. For FY2017, the U.S. government obligated $2.1 billion for development activities managed by international organizations and financial institutions, including contributions to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); the United Nations Development Program (UNDP); and MDBs, such as the World Bank.11

Independent agencies, such as the Peace Corps and Millennium Challenge Corporation also administer programs considered under bilateral development assistance.

Multilateral Development Assistance

A share of U.S. foreign assistance—4% in FY2018 ($1.8 billion)—is provided to finance multilateral development projects. Multilateral aid is funded largely through the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) account and individual accounts for each of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs). This aid is distinct from U.S. dues (assessed contributions) paid to multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, which are not considered foreign assistance.9 It is also distinct from bilateral assistance which may be implemented by multilateral agencies under a contract or cooperative agreement with a U.S. agency. Multilateral development assistance is a method of combining U.S. funds with contributions from other donor nations to share the costs of economic development activities, drawing on a wider range of development experience and perspectives. This collaborative approach means the United States has less control over multilateral assistance than over bilateral economic assistance, though it also affords the United States a voice in such multilateral efforts. In determining U.S. contributions to the various multilateral institutions the United States faces the challenge of finding the right balance between the benefits of burden sharing and the constraints of sharing control. Policymakers may also consider the strategic implications of U.S. funding levels relative to those of other donors, as funding may be commensurate with influence in come multilateral fora.nonconcessionalconcessional lending window (the International Development AssociationsAssociation [IDA]) and about 17.3% to the nonconcessional lending window (the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development [IBRD]). In determining the U.S. share of donor contributions to the various multilateral institutions, the U.S. faces the challenge of finding the right balance between the benefits of burden sharing and the constraints of sharing control when determining multilateral priorities.

Humanitarian Assistance

For FY2017, obligations for humanitarian assistance programs amounted to $8.9 billion, 18% of total assistance.

Humanitarian Assistance

Unlike development assistance programs, which are often viewed as long-term efforts that may have the effect of preventing future crises from emerging, humanitarian assistance programs are devoted largely to the immediate alleviation of human suffering in emergencies, both natural and man-made, as well as problems resulting from conflict associated with failed or failing statesboth natural and human-induced disasters, including conflict associated with failed or failing states. For FY2018, obligations for humanitarian assistance programs amounted to $8.5 billion, 18% of total assistance. The largest portion of humanitarian assistance is managed through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account by USAID, which provides relief and rehabilitation efforts to victims of man-madehuman-induced and natural disasters, such as. Recent responses have addressed the economic and social dislocations caused by the 2014/2015 Ebola epidemic, andof the ongoing crises in Syria, South Sudan, Yemen, and Venezuela. A portion of IDA is used for food assistance through the Emergency Food Security Program.

Additional humanitarian assistance goes to programs administered by the State Department and funded under the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) and the Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance (ERMA) accounts, aimed at addressing the needs of refugees and internally displaced persons. These accounts support a number of refugee relief organizations, including the U.N. High Commission for Refugees and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The Department of Defense also provides disaster relief under the Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster, and Civic Assistance (OHDACA) account of the DOD appropriations. (For further information on humanitarian programs, see CRS In Focus IF10568, Overview of the Global Humanitarian and Displacement Crisis, by Rhoda Margesson.)

The bulk of FFPApproximately 80% of FFPA Title II Agriculture appropriations—$1.34 billion in obligations, about 75% of total Food for Peace Act in FY2017 in FY2018—are used by USAID to address emergency needs, mostly to purchase U.S. agricultural commodities, for emergency needs, supplementing both refugee and disaster programs.12 (For more information on food aid programs, see CRS Report R45422, U.S. International Food Assistance: An Overview, by Alyssa R. Casey.)

Assistance Serving Both Development and Special Political/Strategic Purposes

A few accounts promote special U.S. political and strategic interests. Programs funded through the Economic Support Fund (ESF) account generally aim to promote political and economic stability, often through activities indistinguishable from those provided under regular development programs.1312 However, ESF is also used foralso provides direct budget support to foreign governments and to support sovereign loan guarantees. For FY2017FY2018, USAID and the State Department obligated $4.81 billion, nearly 109% of total assistance, through this account.

For many years, following the 1979 Camp David accords, most ESF funds went to support the Middle East Peace Process—in FY1997FY1998, for example, 8788% of ESF went to Israel, Egypt, the West Bank and Jordan. Those proportions have declinedbeen significantly lower in recent decades. In FY2007, 22FY2008, 19% of ESF funding went to these countries and, in FY2017, 25FY2018, 26%. Since the September 2001 terrorist attacks, ESF has largely supported countries of importance in the U.S. global counterterrorism strategy. In FY2007FY2008, for example, activities is Afghanistan and Pakistanin Iraq and Afghanistan received 1756% of ESF funding (2521% in FY2017FY2018).

Over the years, other accounts have been establishedCongress has established other accounts to meet specific political or security interests and then were(some have since been dissolved once the need was met). One example is the Assistance to Eastern EuropeEurope, Eurasia, and Central Asia (AEECA) account, established in FY2009 to combine two aid programs that met particular strategic political interests arising from the demise of the Soviet empire. The SEED (Support for East European Democracy Act of 1989) and the FREEDOM Support Act (Freedom for Russia and Emerging Eurasian Democracies and Open Markets Support Act of 1992) programs were designed to help Central Europe and the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union (FSA) achieve democratic systems and free market economies. With funding decreasing as countries in the region graduated from U.S. assistance, Congress discontinued use of the AEECA account in the FY2013 appropriations. Increasing requests and appropriations for countries in the former Soviet Union threatened by Russia, however, led to its re-emergence in the FY2017 and succeeding SFOPS appropriations.

In the recent past, several DOD-funded nontraditional aid programs directed at Afghanistan also supported development effortsarose from the demise of the Soviet empire to help Central Europe and the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union (FSA) achieve democratic systems and free market economies. Recent SFOPS legislation has also included "funds" and directives drawing from several economic and security assistance accounts to address specific strategic priorities, including the Countering Russian Influence Fund, the Countering Chinese Influence Fund, and the Indo-Pacific Strategy. USAID's Transition Initiatives program also focuses largely on strategic goals, supporting civil society, free media, and inclusive governance in countries and communities in political transition.

In the recent past, several DOD-funded aid programs directed at Afghanistan also supported development efforts with largely strategic objectives. The Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund and the Business Task Force wound down as the U.S. military presence in that country declined; the Commander's Emergency Response Program (CERP) still exists. The latter two programs had earlier iterations as well in Iraq.

Nonmilitary Security Assistance

Several U.S. government agencies support programs to address global concerns that are considered threats to U.S. security and well-being, such as terrorism, illicit narcotics, crime, and weapons proliferation. In the past two decades, policymakers have given greater weightprovided increasing support to these programs. In FY2017, theyFY2018, these programs amounted to $2.98 billion, 6% of total assistance.

Since the mid-1990s, three U.S. agencies—State, DOD, and Energy—have provided funding, technical assistance, and equipment to counter the proliferation of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear weapons. Originally aimed at the former Soviet Union under the rubric cooperative threat reduction (CTR), these programs seek to ensure that these weapons are secured and their spread to rogue nations or terrorist groups prevented.14 In addition to nonproliferation efforts, the13 The Nonproliferation, Anti-Terrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR) account, managed by the State Department, provides for nonproliferation efforts and encompasses civilian anti-terrorism efforts such as detecting and dismantling terrorist financial networks, establishing watch-list systems at border controls, and building developingpartner country anti-terrorism capacities. NADR also funds humanitarian demining programs.

The State Department is the main implementer of counternarcotics programs. The State-managed International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) account supports counternarcotics activities, most notably in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Peru, and Colombia. It also helpsPrograms funded under INCLE also help develop the judicial systems—assisting judges, lawyers, and legal institutions—of many developing countries, especially in Afghanistan. DOD and USAID also support counternarcotics activities, the former largely by providing training and equipment, the latter by offering alternative crop and employment programs (which are generally considered bilateral development assistance).14.15

Military Assistance

The United States provides military assistance to U.S. friends and allies to help them acquire U.S. military equipment and training. At $14.513.6 billion, military assistance accounted for about 29% of total U.S. foreign aid in FY2017FY2018. The Department of State administers three programs, with corresponding appropriations accounts that are then implemented by DOD. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) is a grant program that enables governments to receive equipment and associated training from the U.S. government or to access equipment directly through U.S. commercial channels. Most FMF grants support the security needs of Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Pakistan, the assistance-funded arm of the Foreign Military Sales program, through which the U.S. government procures defense articles for foreign partners. The program supports U.S. foreign policy, as well as the U.S. defense industry, and helps ensure the interoperability of weapons systems among allies and partners. In FY2018, FMF grants primarily supported the security needs of Israel, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. The International Military Education and Training program (IMET) offers military training on a grant basis to foreign military officers and personnel. Peacekeeping funds (PKO) are used to support voluntary non-U.N. peacekeeping operations as well as training for an African crisis response force. Since 2002, DOD appropriations have supported FMF-like programs, training and equipping security forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. These programs and the accounts that fund them are called the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund (ASFF) and, through FY2012, the Iraq Security Forces Fund (ISFF). Beginning in FY2015, similar support was provided Iraq under the Iraq Train and Equip Fund. The DOD-funded programs in Afghanistan and Iraq accounted for more than half of total military assistance in FY2017.

Delivery of Foreign Assistance

How and in what form assistance reaches an aid recipient can vary widely, depending on the type of aid program, the objective of the assistance, and the agency responsible for providing the aid.

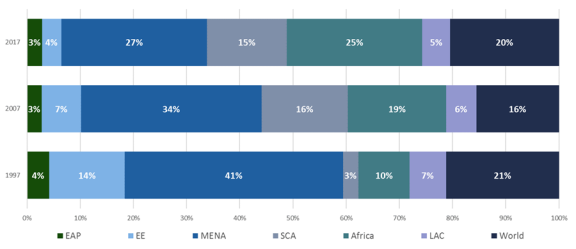

What Executive Branch Agencies Implement Foreign AidAssistance Programs?

Federal agencies may implement foreign assistance programs using funds appropriated directly to them or funds transferred to them from another agency. For example, significant funding appropriated through State Department and Department of Agriculture accounts is used for programs implemented by USAID (see Figure 2). The funding data in this section reflect the agency that implemented the aid, not necessarily the agency to which funds were originally appropriated.

U.S. Agency for International Development

For 50 years, USAID has implemented the bulk of the U.S. bilateral economic development and humanitarian assistance. It directly implements the Development Assistance, International Disaster Assistance, and Transition Initiatives accounts, as well as a USAID-designated portion of the Global Health Programs account. Jointly with the State Department, USAID co-manages ESF, AEECA, and Democracy Fund programs, which frequently support development activities as a means of promoting U.S. political and strategic goals.1615 Based on historical averages, according to USAID, the agency implements more than 90% of ESF, 70% of AEECA, 40% of the Democracy Fund, and about 60% of the Global HIV/AIDS funding appropriated to the State Department. USAID also implements all Food for Peace Act Title II food assistance funded through agriculture appropriations.

USAID obligated an estimated $20.5507 billion to implement foreign assistance programs and activities in FY2017.17FY2018.16 The agency's staff in 2018 totaled 9,74718,,17 of which about 67% were working overseas, overseeing the implementation of hundreds of projects undertaken by thousands of private sector contractors, consultants, and nongovernmental organizations.19

U.S. Department of Defense

DOD implements all SFOPS-funded military assistance programs—FMF, IMET, PKO, and PCCFPKO—in conjunction with the policy guidance of the Department of State. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency is the primary DOD body responsible for these programs. DOD also carries out an array of state-building activities, funded through defense appropriations legislation, which are usually in the context of training exercises and military operations. These sorts of activities, once the exclusive jurisdiction of civilian aid agencies, include development assistance to Iraq and Afghanistan through the Commander's Emergency Response Program (CERP), the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund, and the Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund, and elsewhere through the Defense Health Program, counterdrug activities, and humanitarian and disaster relief. Training and equipping of Iraqi and Afghan police and military, though similar in nature to some traditional security assistance programs, has been funded and implemented primarily through DOD appropriations, though implementing the Iraq police training program was a State Department responsibility from 2012 until it was phased out in 2013.

In FY2017, the Department of DefenseFY2018, DOD implemented an estimated $14.5013.31 billion in foreign assistance programs.2019

U.S. Department of State

The Department of State manages and co-manages a wide range of assistance programs. It is the lead U.S. civilian agency on security and refugee related assistance, and has sole responsibility for implementingadministering the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) and Nonproliferation, Antiterror, and DeminingAntiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR) accounts, the two Migration and Refugee accounts (MRA and ERMA), and the International Organizations and Programs (IO&P) account. State is also home to the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC), which manages the State Department's portion of Global Health funding in support of HIV/AIDS programs, though many of these funds are transferred to and implemented by USAID, the National Institutes of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In conjunction with USAID, the State Department manages the Economic Support Fund (ESF), AEECA assistance to the former communist states, and Democracy Fund accounts. For these accounts, the State Department largely sets the overall policy and direction of funds, while USAID implements the preponderance of programs. In addition, the State Department, through its Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, has policy authority over the Foreign Military Financing (FMF), International Military Education and Training (IMET), and Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) accounts, and, while it was active, the Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund (PCCF). These programs are implemented by the Department of Defense. Police training programs have traditionally been the responsibility of the International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) Office in the State Department, though programs in Iraq and Afghanistan were implemented and paid for by the Department of Defense for several years.

State is also the organizational home to the Office of U.S. Foreign Assistance Resources (formerly the Office of the Director of Foreign Assistance), known as "F," which was created in 2006 to coordinate U.S. foreign assistance programs. The office establishes standard program structures and definitions, as well as performance indicators, and collects and reports data on State Department and USAID aid programs.

The State Department implemented about $7.6636 billion in foreign assistance funding in FY2017,21FY2018, though it has policy authority over a much broader range of assistance funds.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services implements a range of global health programs through its various component institutions. As an implementing partner in the President's Emergency Plan for AidsAIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a large portion of HHS foreign assistance activity isactivities are related to HIV prevention and treatment, including technical support and preventing mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) participates in a broad range of global disease control activity, including rapid outbreak response, global research and surveillance, information technology assistance, and field epidemiology and laboratory training. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) also conduct international health research that is reported as assistance.

In FY2017FY2018, HHS institutions implemented $2.6612 billion in foreign assistance activities.22

U.S. Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury's Under Secretary for International Affairs administers U.S. contributions to and participation in the World Bank and other multilateral development institutions. In this case, the agency manages the distribution of funds to the institutions, but does not implement programs. Presidentially appointed U.S. executive directors at each of the banks represent the United States' point of view. Treasury also deals with foreign debt reduction issues and programs, including U.S. participation in the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, and manages a. The agency manages the distribution of funds and negotiates program structure, but does not implement programs. Treasury, however, does directly implement a bilateral technical assistance program offering temporary financial advisors to countries implementing major economic reforms and combating terrorist finance activity.

For FY2017FY2018, the Department of the Treasury managed foreign assistance valued at about $1.8556 billion.23

Millennium Challenge Corporation

Created in February 2004, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) seeks to concentrate significantly higher amounts of U.S. resources in a few low- and lower-middle-income countries that have demonstrated a strong commitment to political, economic, and social reforms relative to other developing countries. A significant feature of the MCC effort is that recipient countries formulate, propose, and implement mutually agreed multifive-year U.S.-funded project plans known as compacts. Compacts in the 27 recipient countries selected to date have emphasized construction of infrastructureinfrastructure projects. The MCC is a U.S. government corporation, headed by a chief executive officer who reports to a board of directors chaired by the Secretary of State. The Corporation maintains a relatively small staff of about 300.

The MCC obligated about $1.01 billion in FY2017.24

Other Agencies

A number of other government agencies play a role in implementing foreign aid programs.

- The Peace Corps, an autonomous agency with

FY2017FY2018 obligations of $445433.1 million,2524 supports about 7,300 volunteers in6561 countries.2625 Peace Corps volunteers workinon a wide range of educational, health, and community development projects.2726 - The Trade and Development Agency (TDA), which obligated $

5813.7 million inFY2017, finances trade missions and feasibility studies for private sector projects likely to generate U.S. exports.28 TheFY2018, funds project preparation assistance, such as feasibility studies, and partnership building activities, such as trade missions, likely to generate U.S. exports for overseas infrastructure and other projects.27 Until recently, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC)providesprovided political risk insuranceto U.S. companies investing, loans, and guarantees for U.S. private investments in developing countriesand finances projects through loans and guarantees. Its insurance activitieshave beenwere self-sustaining, but credit reform rulesrequirerequired a relatively small appropriation to back up U.S. guarantees and for administrative expenses. The Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act), signed into law in October 2018 (P.L. 115-254), authorized consolidation of OPIC and USAID's Development Credit Authority into a new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC), which is expected to becomeDFC), which became operational infallDecember 2019.2928 ForFY2017FY2018, as for most prior years, OPIC receipts exceeded appropriations, resulting in a net gain to the Treasury.3029 The DFC is also expected to operate at a net gain to the Treasury.

- The Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank provides financing and insurance to facilitate the export of U.S. goods and services when the private sector is unwilling or unable to do so and/or to counter foreign export credit financing. Ex-Im Bank receives an annual appropriation for administrative expenses, but its revenues from interest, risk premia, and other fees charged for its support often exceed its appropriation, creating a net gain to the Treasury.

- The Inter-American Foundation and the African Development Foundation, obligating $

25.830.1 million and $20.217.7 million, respectively, inFY2017,31FY2018,30 finance small-scale enterprise and grassroots self-help activities aimed at assisting poor people.

What Are the Different Forms in Which Assistance Is Provided?

|

|

Source: USAID Explorer and CRS calculations. |

Most U.S. assistance is now provided as a grant (gift) rather than a loan, so as not to increase the heavy debt burden carried by many developing countries. However, the forms a grant may take are diverse. The most common type of U.S. development aid is project-based assistance (77% in FY2017FY2018), in which aid is channeled through an implementing partner, most often a contractor or nongovernmental organization, to complete a specific to complete a project. Aid is also provided in the form of core contributioncontributions to international organizations such as the United Nations, technical assistance, and direct budget support (cash transfer) to governments. A portion of aid money is also spent on administrative costs (see Figure 3). Within these categories, aid may take many forms, as described below.

Cash Transfer

Although it is the exception rather than the rule, some countries receive aid in the form of a cash grant to the government. Dollars provided in this way support a government's balance-of-payments situation, enabling it to purchase more U.S. goods, service its debt, or devote more domestic revenues to developmental or other purposes. Cash transfers have been made as a reward to countries that have supported the United States' counterterrorism operations (Turkey and Jordan in FY2004), to provide political and strategic support (both Egypt and Israel annually for decades after the 1979 Camp David Peace Accord), and in exchange for undertaking difficult political and economic reforms.

Commodities

Training

Transfer of knowledge and skills is a significant part of most assistance programs. The International Military Education and Training Program (IMET), for example, provides training to officers of the military forces of allied and friendly nations. Tens of thousands of citizens of aid recipient countries receive short-term technical training or longer-term degree training annually under USAID programs. More than one-quarter of Peace Corps volunteers are English, math, and science teachers, and also fall into this category. Other aid programs provide law enforcement personnel with anti-narcotics or anti-terrorism training.

ExpertiseMany assistance programs provide expert advice to government and private sector organizations. For example, the Department of the Treasury, USAID, and U.S.-funded multilateral banks all place specialists in host government ministries to make recommendations on policy reforms in a wide variety of sectors. USAID has often placed experts in private sector business and civic organizations to help strengthen them in their formative years or while indigenous staff are being trained. While most of these experts are U.S. nationals, in Russia, USAID funded the development of locally staffed political and economic think tanks to offer policy options to that government.

GrantsUSAID, the Inter-American Foundation, and the African Development Foundation often provide aid in the form of grants directly to local organizations to foster economic and social development and to encourage civic engagement in their communities. Grants are sometimes provided to microcredit organizations, such as village-level women's savings groups, which in turn provide loans to microentrepreneurs. Small grants may also address specific community needs. Recent IAF grants, for example, have supported organizations that help resettle Salvadoran migrants deported from the United States and youth programs in Central America aimed at gang prevention.

In-Kind GoodsAssistance may be provided in the form of food commodities, weapons systems, or equipment such as generators or computers. Food aid may be provided directly to meet humanitarian needs or to encourage attendance at a maternal/child health care program. Weapons supplied under the military assistance program may include training in their use. Equipment and commodities provided under development assistance are usually integrated with other forms of aid to meet objectives in a particular social or economic sector. For instance, textbooks have been provided in both Afghanistan and Iraq as part of a broader effort to reform the educational sector and train teachersalongside a broader teacher training and educational reform effort. Computers may be offered in conjunction with training and expertise to fledgling microcredit institutions. Since PEPFAR was first authorized in 2004, antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) provided to individuals living with HIV/AIDS have been a significant component of commodity-basedglobal health assistance.

Economic Infrastructure

Although once a significant portion of U.S. assistance programs, construction of economic infrastructure—roads, irrigation systems, electric power facilities, etc.— Although it is the exception rather than the rule, some countries receive aid in the form of a cash grant to the government. Dollars provided in this way support a government's balance-of-payments situation, enabling it to purchase more U.S. goods, service its debt, or devote more domestic revenues to developmental or other purposes. Cash transfers have been made as a reward to countries that have supported the United States' counterterrorism operations (Turkey and Jordan in FY2004), to provide political and strategic support (both Egypt and Israel annually for decades after the 1979 Camp David Peace Accord), and in exchange for undertaking difficult political and economic reforms. was rarely providedhas been a relatively small component of aid efforts after the 1970s. Because of the substantial expense of these projects, they were to be found only in large assistance programs, such as that for Egypt in the 1980s and 1990s, where the United States constructed major urban water and sanitation systems. The aid programs in Iraq and Afghanistan supportedimplemented in support of post-U.S. invasion reconstruction in Iraq and Afghanistan were an exception, supporting the building of schools, health clinics, roads, power plants, and irrigation systems. In Iraq alone, more than $10 billion went to economic infrastructure. The Millennium Challenge Corporation now oversees much of this economic infrastructure portfolio, using a competitive selection process to direct such programs toward well-governed countries in which these investments may be more sustainable.

Direct Budget Support

the building of schools, health clinics, roads, power plants, and irrigation systems. In Iraq alone, more than $10 billion went to economic infrastructure. Economic infrastructure is now also supported by U.S. assistance in a wider range of developing countries through the Millennium Challenge Corporation. In this case, recipient countries design their own assistance programs, most of which, to date, include an infrastructure component.

Training

Transfer of knowledge and skills is a significant part of most assistance programs. The International Military Education and Training Program (IMET) provides training to officers of the military forces of allied and friendly nations. Tens of thousands of citizens of aid recipient countries receive short-term technical training or longer-term degree training annually under USAID programs. More than one-quarter of Peace Corps volunteers are English, math, and science teachers. Other aid programs provide law enforcement personnel with anti-narcotics or anti-terrorism training.

Expertise

Many assistance programs provide expert advice to government and private sector organizations. The Department of the Treasury, USAID, and U.S.-funded multilateral banks all place specialists in host government ministries to make recommendations on policy reforms in a wide variety of sectors. USAID has often placed experts in private sector business and civic organizations to help strengthen them in their formative years or while indigenous staff are being trained. While most of these experts are U.S. nationals, in Russia, USAID funded the development of locally staffed political and economic think tanks to offer policy options to that government.

Small Grants

USAID, the Inter-American Foundation, and the African Development Foundation often provide aid in the form of small grants directly to local organizations to foster economic and social development and to encourage civic engagement in their communities. Grants are sometimes provided to microcredit organizations, such village-level women's savings groups, which in turn provide loans to microentrepreneurs. Small grants may also address specific community needs. Recent IAF grants, for example, have supported organizations that help resettle Salvadoran migrants deported from the United States and youth programs in Central America aimed at gang prevention.

How Much Aid Is Provided as Loans and How Much as Grants? What Are Some Types of Loans? Have Loans Been Repaid? Why Is Repayment of Some Loans Forgiven?

Under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the President may determine the terms and conditions under which most forms of assistance are provided, though Congress included provisions encouraging the use of grants over loans in some instances, such as development assistance to the least developed countries. In general, the financial condition of a country—its ability to meet repayment obligations—has been an important criterion of the decision to provide a loan or grant. Some programs, such as humanitarian and disaster relief programs, were designed from the beginning to be entirely grant activities.

Between 1946 and 2018, the United States loaned $115.5 billion in foreign economic and military aid to foreign governments, and while most foreign aid is now provided through grants, $11.0 billion in loans to foreign governments remained outstanding at the end of FY2018.31

Loan/Grant Composition

During the past two decades, nearly all foreign aid—military as well as economic—has been provided in grant form. While loans represented 32% of total military and economic assistance between 1962 and 1988, this figure declined substantially beginning in the mid-1980s, until by FY2001, loans represented less than 1% of total aid appropriations. The de-emphasis on loan programs came largely in response to the debt problems of developing countries, some of which was attributable to aid loans. Both Congress and the executive branch have generally supported the view that foreign aid should not add to the already existing debt burden carried by these countries. In the FY2019 budget request, the Trump Administration encouraged the use of loans over grants when providing military assistance (Foreign Military Financing), but Congress did not include language in support of that proposal in the enacted FY2019 appropriation (P.L. 116-6).

Loan Guarantees

Although a small proportion of total current aid, there are significant USAID-managed programs that guarantee loans, meaning the U.S. government agrees to pay a portion of the amount owed in the case of a default on a loan. A Development Credit Authority (DCA) loan guarantee, for example, in which risk is shared with a private sector bank, can be used to increase access to finance in support of any development sector. The DCA is to bewas transferred from USAID in 2019 to the new IDFC, established by the BUILD Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-254),and merged with the former Overseas Private Investment Corporation to form the new DFC in 2019 (P.L. 115-254) to enhance U.S. development finance capacity. The DFC has authority to provide loan guarantees as well.

to enhance U.S. development finance capacity.

Under the Israeli Loan Guarantee Program, the United States has guaranteed repayment of loans made by commercial sources to support the costs of immigrants settling in Israel from other countries and may issue guarantees to support economic recovery.32 USAID has also provided loan guarantees in recent years to improve the terms or amounts of financing from international capital markets for Ukraine and Jordan. In these cases, assistance funds representing a fraction of the guarantee amount are providedset aside to cover possible default.32 Previously, under the Israeli Loan Guarantee Program, the United States guaranteed repayment of loans made by commercial sources to support the costs of immigrants settling in Israel from other countries and may issue guarantees to support economic recovery.33

Debt Forgiveness

The United States has also forgiven some to cover possible default.33

Loan Repayment

Between 1946 and 2016, the United States loaned $112.7 billion in foreign economic and military aid to foreign governments, and while most foreign aid is now provided through grants, $9.18 billion in loans to foreign governments remained outstanding at the end of FY2016.34 For nearly three decades, Section 620q of the Foreign Assistance Act (the Brooke amendment) has prohibited new assistance to the government of any country that falls more than one year past due in servicing its debt obligations to the United States, though the President may waive application of this prohibition if he determines it is in the national interest.

Debt Forgiveness

The United States has also forgiven debts owed by foreign governments and encouraged, with mixed success, other foreign aid donors and international financial institutions to do likewise. In some cases, the decision to forgive foreign aid debts has been based largely on economic grounds as another means to support development efforts by heavily indebted, but reform-minded, countries. The United States has been one of the strongest supporters of the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). These initiatives, which began in the late 1990s, include participation of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and other international financial institutions in a comprehensive debt workout framework for the world's poorest and most debt-strapped nations.34

The largest and most hotly debated debt forgiveness actions have been implemented for much broader foreign policy reasons with a more strategic purpose. Poland, during its transition from a communist system and centrally planned economy (1990—$2.46 billion); Egypt, for making peace with Israel and helping maintain the Arab coalition during the Persian Gulf War (1990—$7 billion); and Jordan, after signing a peace accord with Israel (1994—$700 million), are examples. Similarly, the United States forgave about $4.1 billion in outstanding Saddam Hussein-era Iraqi debt in November 2004 and helped negotiate an 80% reduction in Iraq's debt to creditor nations later that month.

What Are the Roles of Government and Private Sector in Development and Humanitarian AidAssistance Delivery?

Most development and humanitarian assistance activities are not directly implemented by U.S. government personnel but by private sector entities, such as individual personal service contractors, consulting firms, universities, private voluntary organizations (PVOs), or public international organizations (PIOs). Generally speaking, U.S. government foreign service and civil servants determine the direction and priorities of the aid program, allocate funds while keeping within legislative requirements, ensure that appropriate projects are in place to meet aid objectives, select implementers, and monitor the implementation of those projects for effectiveness and financial accountability. Both USAID and the State Department have promoted the use of public-private partnerships, in which private entities such as corporations and foundations are contributing partners, not paid implementers, in situations where business interests and development objectives coincide.35

As foreign direct investment in developing countries has increased significantly in recent decades, far exceeding foreign assistance from governments in many countries, agencies have sought partnerships and other means of channeling those investments in support of U.S. development priorities. Which Countries Receive U.S. Foreign Assistance? In FY2018Which Countries Receive U.S. Foreign Aid?

In FY2017, the United States provided some form of bilateral foreign assistance to more than 150 180 countries.36 Aid is concentrated heavily in certain countries, reflecting the priorities and interests of United States foreign policy at the time. Table 2 identifies the top 15 recipients of U.S. foreign assistance for FY1997, FY2007 and FY2017FY1998, FY2008 and FY2018, to show shifts in priority countries over time.

Table 2. Top Recipients of U.S. Foreign Assistance from All Sources, FY1997, FY2007, and FY2017

(in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

FY1997 |

FY2007 |

FY2017 |

|||||

|

Israel |

3,173 |

Iraq |

7,867 |

Afghanistan |

5, |

||

|

Egypt |

2, |

Afghanistan |

4,980 |

Iraq |

3,712 |

||

|

Russia |

|

Israel |

2, |

Israel |

3,191 |

||

|

Jordan |

219 |

Egypt |

|

Jordan |

1,490 |

||

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

206 |

Russia |

1, |

Egypt |

1, |

||

|

Turkey |

201 |

Sudan (former) |

1, |

Ethiopia |

|

||

|

Peru |

|

Pakistan |

824 |

Kenya |

|

||

|

Bolivia |

137 |

Ghana |

|

South Sudan |

|

||

|

India |

128 |

Mali |

526 |

Syria |

891 |

||

|

Greece |

126 |

El Salvador |

|

Nigeria |

852 |

||

|

Palau |

122 |

Colombia |

472 |

Pakistan |

837 |

||

|

Colombia |

|

Kenya |

|

Uganda |

|

||

|

Ukraine |

105 |

Ethiopia |

417 |

Tanzania |

|

||

|

Haiti |

|

Jordan |

399 |

Yemen |

595 |

||

|

Rwanda |

91 |

South Africa |

378 |

Somalia |

|

||

Source: USAID Explorer. Note: DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo.

As shown in the table above, there are both similarities and sharp differences among country aid recipients for the three periods. The most consistent thread connecting the top aid recipients over the past two decades has been continuing U.S. strategic interests in the Middle East, with large programs maintained for Israel and Egypt and,as well as for Iraq, following the 2003 invasion. Two key countries in the U.S. counterterrorism strategy, Afghanistan and Pakistan, made their first appearances on the list in FY2002 and continued to be. Of the two, only Afghanistan remains among the top recipients in FY2017FY2018.

In FY1997FY1998, one sub-Saharan African country appeared among leading aid recipients; in FY2017, 7FY2018, seven of the 15 are sub-Saharan African. Many are focus countries under the PEPFAR initiative to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic; South Sudan receives support as a newly independent country with multiple humanitarian and development needs. In FY1997newer initiatives such as Power Africa, Feed the Future, and Invest Africa have also driven funds there. In FY1998, three countries from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union made the list, as many from the region had for much of the 1990s, representing the effort to transform the former communist nations to democratic societies and market-oriented economies. None of those countries appear in the FY2017FY2018 list. In FY1997, four Latin American countries make the list; no countries from the region appear in FY2017FY2018.

On a regional basis, the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region has received the largest share of U.S. foreign assistance for many decades. Although economic aid to the region's top two recipients, Israel and Egypt, began to decline in the late 1990s, the dominant share of bilateral U.S. assistance consumed by the MENA region was maintained in FY2005 by the war in Iraq. Despite the continued importance of the region, its share slipped substantially by FY2017continued to slip substantially through FY2018 as the effort to train and equip Iraqi forces diminished.