Department of State and Foreign Operations Appropriations: History of Legislation and Funding in Brief

Congress currently appropriates most foreign affairs funding through annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations. Prior to FY2008, however, Congress provided funding for the Department of State, international broadcasting, and related programs within the Commerce, Justice, State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies appropriations. In those years, Congress separately appropriated funding for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and foreign aid within the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs appropriations. The 110th Congress aligned the two foreign affairs appropriations into the SFOPS legislation.

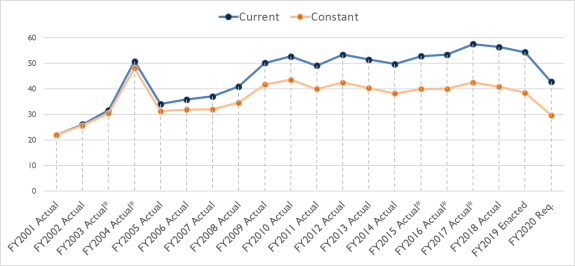

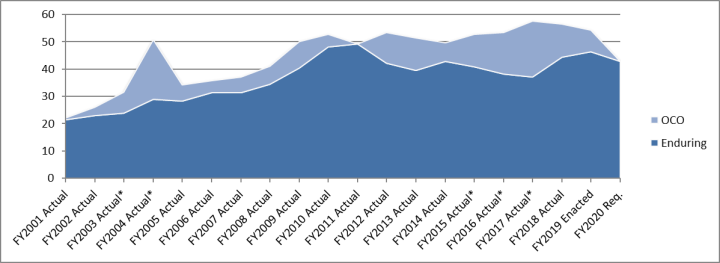

SFOPS appropriations since FY2001 have included enduring appropriations (ongoing or base funding), emergency supplemental appropriations, and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) appropriations. Total SFOPS funding levels in both current and constant dollars show a general upward trend, with FY2004 as the peak largely as a result of emergency supplemental appropriations for Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Funds. When adjusted for inflation, annual foreign affairs appropriations have yet to surpass the FY2004 peak. The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and the Bipartisan Budget Acts (BBA) of 2015 and 2018 appear to have had an impact on both enduring and OCO funding levels.

The legislative history of SFOPS appropriations shows that nearly all foreign affairs appropriations measures within the past 25 years were passed within omnibus, consolidated, or full-year continuing resolutions, rather than in stand-alone bills. Moreover, many appropriations were passed after the start of the new fiscal year, at times more than half way into the new fiscal year. In many fiscal years, SFOPS appropriations included emergency supplemental funding or, since FY2012, OCO funding.

Department of State and Foreign Operations Appropriations: History of Legislation and Funding in Brief

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Legislative History

- Funding History

- 20-Year Funding Trends

- Enduring vs. Supplemental/OCO Appropriations

Figures

Summary

Congress currently appropriates most foreign affairs funding through annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations. Prior to FY2008, however, Congress provided funding for the Department of State, international broadcasting, and related programs within the Commerce, Justice, State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies appropriations. In those years, Congress separately appropriated funding for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and foreign aid within the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs appropriations. The 110th Congress aligned the two foreign affairs appropriations into the SFOPS legislation.

SFOPS appropriations since FY2001 have included enduring appropriations (ongoing or base funding), emergency supplemental appropriations, and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) appropriations. Total SFOPS funding levels in both current and constant dollars show a general upward trend, with FY2004 as the peak largely as a result of emergency supplemental appropriations for Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Funds. When adjusted for inflation, annual foreign affairs appropriations have yet to surpass the FY2004 peak. The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and the Bipartisan Budget Acts (BBA) of 2015 and 2018 appear to have had an impact on both enduring and OCO funding levels.

The legislative history of SFOPS appropriations shows that nearly all foreign affairs appropriations measures within the past 25 years were passed within omnibus, consolidated, or full-year continuing resolutions, rather than in stand-alone bills. Moreover, many appropriations were passed after the start of the new fiscal year, at times more than half way into the new fiscal year. In many fiscal years, SFOPS appropriations included emergency supplemental funding or, since FY2012, OCO funding.

Introduction

Congress appropriates foreign affairs funding primarily through annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations.1 Prior to FY2008, however, Congress provided funds for the Department of State and international broadcasting within the Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies appropriations (CJS) and separately provided foreign aid funds within Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs appropriations.

The transition between the different alignments occurred in the 109th Congress, with a change in appropriations subcommittee jurisdiction. For that Congress, the House of Representatives appropriated State Department funds separately from foreign aid, as in earlier Congresses, but the Senate differed by appropriating State and foreign aid funds within one bill—the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations.2 Both the House and Senate began jointly funding Department of State and foreign aid appropriations within the Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs Appropriations in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 (P.L. 110-161).

SFOPS appropriations currently include State Department Operations (including accounts for Embassy Security, Construction, and Maintenance, and Education and Cultural Affairs, among others); Foreign Operations (including USAID administration expenses, bilateral economic assistance, international security assistance, multilateral assistance, and export assistance); various international commissions; and International Broadcasting (including VOA, RFE/RL, Cuba Broadcasting, Radio Free Asia, and Middle East Broadcasting Networks). While the distribution varies slightly from year to year, Foreign Operations funding is typically about twice as much as State Operations funding.

In addition to regular, enduring SFOPS appropriations, Congress has approved emergency supplemental funding requested by Administrations to address emergency or otherwise off-cycle budget needs. Since FY2012, Congress has also appropriated Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding requested within the regular budget process for Department of State and USAID war-related expenses.

This report lists the legislative and funding history of SFOPS appropriations and includes funding trends.

Legislative History

Nearly all foreign affairs appropriations within the past 25 years were passed within omnibus, consolidated, or full-year continuing resolutions, rather than in stand-alone bills, and usually after the start of the new fiscal year. Many foreign policy experts contend that stand-alone appropriations legislation would allow for a more rigorous debate on specific foreign policy activities and improve the ability to introduce or fund new programs, or cancel and defund existing programs. Such experts assert that the frequent practice of passing continuing resolutions and delaying passage of appropriations well into the next fiscal year has hindered program planning (not just in foreign affairs) and has reduced the ability to fund programs that did not exist in the previous cycle.

In addition to annual appropriations, several laws require Congress to authorize State and foreign operations funding prior to expenditure.3 Before 2003, Congress typically provided authorization in a biannual Foreign Relations Authorization bill.4 This practice not only authorized funding for obligation and expenditure, but also provided a forum for more rigorous debate on specific foreign affairs and foreign aid policies and a legislative vehicle for congressional direction. In recent years, the House and Senate have separately introduced or considered foreign relations and foreign aid authorization bills, but none have been enacted.5

Table 1 below provides a 25-year history of enacted foreign affairs appropriations laws (excluding short-term continuing resolutions and supplemental appropriations), including the dates they were sent to the President and signed into law. Some observations follow:

- Since FY1995, Congress appropriated foreign affairs funding in on-time, freestanding bills once—in 1994 for the FY1995 appropriations year. The last time Congress passed foreign affairs funding on time, but not in freestanding legislation, was for FY1997.

- Congress included foreign affairs funding within an omnibus, consolidated, or full-year continuing resolution 21 of the past 25 years.

- FY2006 was the last time Congress enacted freestanding State Department and foreign operations appropriations bills.

- Six times over the past 25 years, Congress sent the State and foreign operations appropriations to the President in March, April, or May—six to eight months into the fiscal year.

|

Fiscal Year |

Commerce, Justice, State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies |

Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs |

The Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs |

Date Sent to President and Signed |

|

FY2019 |

P.L. 116-6—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 |

To Pres. 02/15/19; signed 02/15/19 |

||

|

FY2018 |

P.L. 115-141—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 |

To Pres. 03/23/18; signed 03/23/18 |

||

|

FY2017 |

P.L. 115-31—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 |

To Pres. 05/04/17; signed 05/04/17 |

||

|

FY2016 |

P.L. 114-113—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 |

To Pres. 12/18/15; signed 12/18/15 |

||

|

FY2015 |

P.L. 113-235—Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 |

To Pres. 12/16/14; signed 12/16/14 |

||

|

FY2014 |

P.L. 113-76—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 |

To Pres. 1/17/14; signed 1/17/14 |

||

|

FY2013 |

P.L. 113-6, Div. F—Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013 |

To Pres. 3/22/13; signed 3/26/13 |

||

|

FY2012 |

P.L. 112-74, Div. I—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2012 |

To Pres. 12/21/11; signed 12/23/11 |

||

|

FY2011 |

P.L. 112-10 Title XI—Dept. of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011 |

To Pres. 4/15/11; signed 4/15/11 |

||

|

FY2010 |

P.L. 111-117—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010 |

To Pres. 12/15/09; signed 12/16/09 |

||

|

FY2009 |

P.L. 111-8—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2009 |

To Pres. 3/11/09; signed 3/11/09 |

||

|

FY2008 |

P.L. 110-161—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 |

To Pres. 12/24/07; signed 12/26/07 |

||

|

FY2007 |

P.L. 109-289 (CR) and P.L. 110-5—Revised Continuing Appropriations, 2007 (Full-year CR through Sept. 30, 2007) |

P.L. 109-289 (CR) and P.L. 110-5—Revised Continuing Appropriations, 2007 (Full-year CR through Sept 30, 2007) |

Full-year CR to Pres. 2/15/07; signed 2/15/07 |

|

|

FY2006 |

P.L. 109-108—Science, State, Justice, Commerce and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006 |

P.L. 109-102—Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2006 |

P.L. 109-108 to Pres. 11/18/05; signed 11/22/05 P.L. 109-102 to Pres. 11/10/05; signed 11/14/05 |

|

|

FY2005 |

P.L. 108-447—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005, Div. B. |

P.L. 108-447—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005, Div. D. |

To Pres. 12/7/04; signed 12/8/04 |

|

|

FY2004 |

P.L. 108-199—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2004, Div. B |

P.L. 108-199—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2004, Div. D |

To Pres. 1/22/04; signed 1/23/04 |

|

|

FY2003 |

P.L. 108-7, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2003, Div. B |

P.L. 108-7, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2003, Div. E |

To Pres. 2/19/03; signed 2/20/03 |

|

|

FY2002 |

P.L. 107-77—Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2002 |

P.L. 107-115—Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2002 |

P.L. 107-77 to Pres. 11/16/01; signed 11/28/01 P.L. 107-115 to Pres. 1/04/02; signed 1/10/02 |

|

|

FY2001 |

P.L. 106-553—Federal Funding, Fiscal Year 2001, Appendix B, Title IV |

P.L. 106-429—Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2001 |

P.L. 106-553 to Pres. 10/27/00; signed 12/21/00 P.L. 106-429 to Pres. 11/06/00; signed 11/06/00 |

|

|

FY2000 |

P.L. 106-113—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000 |

P.L. 106-113—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000 |

To Pres. 11/22/99; signed 11/29/99 |

|

|

FY1999 |

P.L. 105-277—Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999 |

P.L. 105-277—Omnibus Consolidated and Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act, 1999 |

To Pres. 10/21/98; signed 10/21/98 |

|

|

FY1998 |

P.L. 105-119—Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1998 |

P.L. 105-118—Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1998 |

P.L. 105-119 to Pres. 11/24/97; signed 11/26/97 P.L. 105-118 to Pres. 11/19/97; signed 11/26/97 |

|

|

FY1997 |

P.L. 104-208—Omnibus Appropriations Act, 1997 |

P.L. 104-208—Omnibus Appropriations Act, 1997 |

To Pres. 9/30/96; signed 9/30/96 |

|

|

FY1996 |

P.L. 104-134—Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996 |

P.L. 104-134—Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996 |

To Pres. 4/25/96; signed 4/26/96 |

|

|

FY1995 |

P.L. 103-317—Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1995 |

P.L. 103-306—Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1995 |

P.L. 103-317 to Pres. 8/22/94; signed 8/26/94 P.L. 103-306 to Pres. 8/12/94; signed 8/23/94 |

Source: See http://www.congress.gov.

Note: This table excludes short-term continuing resolutions and supplemental appropriations.

Funding History

Since realignment of the foreign affairs appropriations legislation in FY2008, SFOPS appropriations measures have included State Department Operations, Foreign Operations, various international commissions, and International Broadcasting. For a full list of the accounts included in the FY2019 SFOPS, see Table 2.6

Table 2. Components Included in the FY2019 Department of State, Foreign

Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations

(organized by title)

|

Title |

Programs |

|

State Department Operations |

|

|

Title I—Department of State and Related Agency |

Administration of Foreign Affairs |

|

Foreign Operations |

|

|

Title II—USAID |

USAID Operating Expenses (OE) |

|

Title III—Bilateral Economic Assistance |

Global Health Programs (USAID & State) |

|

Title IV—International Security Assistance |

International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) |

|

Title V—Multilateral Assistance |

International Organizations and Programs |

|

Title VI—Export and Investment Assistance |

Export-Import Bank |

|

General Provisions |

|

|

Title VII—General Provisions |

|

|

Overseas Contingency Operations |

|

|

Title VIII—Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism |

Department of State |

Source: P.L. 116-6, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019.

20-Year Funding Trends

Table 3 and Figure 1 provide the funding levels for enduring funds and Supplemental/OCO funds in the Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs for FY2001-2020 request (in current dollars).

Table 3. State-Foreign Operations Funding Table: FY2001-FY2020 Request

(In billions of current dollars)

|

Fiscal Year |

State Operations |

Foreign Operations |

Total |

|||||||||

|

Enduringa |

Supplemental/ |

Total |

Enduring |

Supplemental/ |

Total |

Enduring |

Supplemental/ |

Grand Total |

||||

|

2001 Actual |

$6.49 |

$0.51 |

$7.00 |

$14.99 |

$0.00 |

$14.99 |

$21.48 |

$0.51 |

$21.99 |

|||

|

2002 Actual |

$7.62 |

$0.55 |

$8.17 |

$15.36 |

$2.61 |

$17.97 |

$22.98 |

$3.16 |

$26.14 |

|||

|

2003 Actualb |

$8.06 |

$0.59 |

$8.65 |

$15.75 |

$7.24 |

$22.99 |

$23.81 |

$7.83 |

$31.64 |

|||

|

2004 Actualb |

$9.38 |

$0.60 |

$9.98 |

$19.61 |

$21.21 |

$40.82 |

$28.99 |

$21.81 |

$50.80 |

|||

|

2005 Actual |

$7.04 |

$3.68 |

$10.72 |

$21.23 |

$2.20 |

$23.43 |

$28.27 |

$5.88 |

$34.15 |

|||

|

2006 Actual |

$8.72 |

$1.55 |

$10.27 |

$22.67 |

$2.92 |

$25.59 |

$31.39 |

$4.47 |

$35.86 |

|||

|

2007 Actual |

$9.48 |

$1.22 |

$10.70 |

$21.95 |

$4.43 |

$26.38 |

$31.43 |

$5.65 |

$37.08 |

|||

|

2008 Actual |

$10.47 |

$2.74 |

$13.21 |

$24.00 |

$3.77 |

$27.77 |

$34.47 |

$6.51 |

$40.98 |

|||

|

2009 Actual |

$13.13 |

$2.70 |

$15.83 |

$27.27 |

$7.04 |

$34.31 |

$40.40 |

$9.74 |

$50.14 |

|||

|

2010 Actual |

$14.74 |

$2.62 |

$17.36 |

$33.26 |

$2.04 |

$35.30 |

$48.00 |

$4.66 |

$52.66 |

|||

|

2011 Actual |

$15.76 |

$0.00 |

$15.76 |

$33.38 |

$0.00 |

$33.38 |

$49.14 |

$0.00 |

$49.14 |

|||

|

2012 Actual |

$13.22 |

$4.63 |

$17.85 |

$28.93 |

$6.58 |

$35.51 |

$42.15 |

$11.21 |

$53.36 |

|||

|

2013 Actual |

$13.10 |

$4.60 |

$17.70 |

$26.48 |

$7.33 |

$33.81 |

$39.58 |

$11.93 |

$51.51 |

|||

|

2014 Actual |

$13.92 |

$1.82 |

$15.74 |

$28.84 |

$5.13 |

$33.97 |

$42.76 |

$6.95 |

$49.71 |

|||

|

2015 Actualc |

$14.05 |

$1.80 |

$15.85 |

$26.83 |

$10.10 |

$36.93 |

$40.88 |

$11.90 |

$52.78 |

|||

|

2016 Actuald |

$11.11 |

$5.30 |

$16.41 |

$27.11 |

$9.89 |

$37.00 |

$38.22 |

$15.19 |

$53.41 |

|||

|

2017 Actuale |

$11.12 |

$6.87 |

$18.00 |

$25.95 |

$13.61 |

$39.56 |

$37.07 |

$20.48 |

$57.55 |

|||

|

2018 Actual |

$11.97 |

$4.18 |

$16.15 |

$30.38 |

$7.84 |

$38.22 |

$42.35 |

$12.02 |

$54.37 |

|||

|

2019 Enacted |

$12.09 |

$4.37 |

$16.46 |

$34.29 |

$3.63 |

$37.92 |

$46.38 |

$8.00 |

$54.38 |

|||

|

2020 Request |

$13.70 |

$0 |

$13.70 |

$29.01 |

$0 |

$29.01 |

$42.71 |

$0 |

$42.71 |

|||

Source: The Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs, FY2001-FY2020; P.L. 116-6.

a. State Operations Enduring levels do not include mandatory spending for the Foreign Service Retirement Fund.

b. FY2003 and FY2004 include funding allocated as part of the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund (IRRF).

c. FY2015 includes the Ebola Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 113-235).

d. FY2016 Includes Zika Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 114-223).

e. FY2017 includes Security Assistance Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-254).

|

Figure 1. State-Foreign Operations Funding: FY2001-FY2020 Request (In billions of current dollars) |

|

|

Source: The Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs, FY2001-FY2020; P.L. 116-6. Notes: FY2003 and FY2004 include funding allocated as part of the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund (IRRF); FY2015 includes the Ebola Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 113-235); FY2016 includes the Zika Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 114-223); and FY2017 includes the Security Assistance Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-254) OCO funding. |

Although current funding for State-Foreign Operations generally has grown since FY2001, there was a spike in funding in FY2004 that can, in large part, be attributed to supplemental funding for the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund, which provided additional funds in that year. The creation of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) added to growing funding levels from FY2004-FY2009. OCO became a regular part of foreign affairs funding as of FY2012. Supplemental funding for Ebola in FY2015, Zika in FY2016, and OCO in FY2017 contributed to the rise in funding levels during those years (see Figure 2).7

The constant dollar trend line generally continues to increase, although at a slower pace than current dollars. FY2004 remains the peak year in constant dollars. The introduction of OCO funding in FY2012 briefly elevated SFOPS funding, but in the following years, funding levels off at nearly the same amount as the FY2012 level.8 After removing inflation, funding for FY2013 through the FY2020 request declines below that level, suggesting that the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) has kept foreign affairs funding below the rate of inflation.9

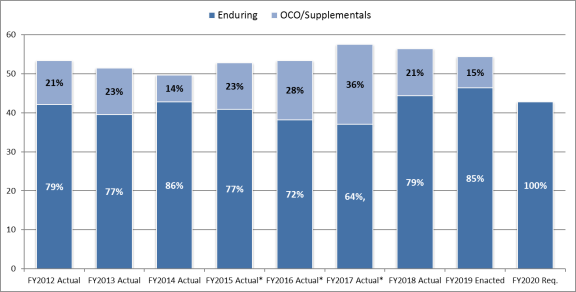

Enduring vs. Supplemental/OCO Appropriations

The Administration distinguishes between enduring (also called base, regular, or ongoing), emergency supplemental, and Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funds. Funds designated as emergency or OCO are not subject to procedural limits on discretionary spending in congressional budget resolutions, or the statutory discretionary spending limits provided through the Budget Control Act of 2011 for FY2011-FY2021 (BCA, P.L. 112-25).

Prior to FY2012, the President typically submitted to Congress additional funding requests (after the initial annual budget request), referred to as emergency supplementals. Supplemental funding packages have historically been approved to address emergency, war-related, or otherwise off-cycle budget needs. The Obama Administration requested emergency supplemental appropriations for urgent unexpected expenses, such as the U.S. international responses to Ebola, the Zika virus, and famine relief to Syria, Yemen, Somalia, and Northeast Nigeria. The Trump Administration has not requested supplemental funding for unexpected international crises.

In contrast to emergency supplemental appropriations, the Obama Administration included within the regular budget request in FY2012 what it described as short-term, temporary, war-related funding for the frontline states of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan—designated as Overseas Contingency Operations funds, or OCO.10 Congress had used the OCO designation in earlier years for Department of Defense appropriations to distinguish between ongoing versus war-related expenditures. In response to the FY2012 SFOPS OCO request, Congress appropriated OCO funds for the Department of State and USAID activities beyond the requested level and for more than just activities in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In FY2012, Congress included OCO funds for the three frontline states as well as for Yemen, Somalia, Kenya, and the Philippines. The Obama Administration first requested OCO funds for a country other than the three frontline states in FY2015, when it requested OCO funds for Syria.11 In FY2018, the Trump Administration requested OCO funds for the Department of State and USAID activities in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, as well as "High Threat/High Risk" areas. These included Syria, Yemen, Nigeria, Somalia, and South Sudan, among others. The Administration's initial FY2019 request included OCO funds for the Department of State and USAID, but after passage of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018, P.L. 115-123), the Administration requested that all previously requested SFOPS OCO funds be moved to enduring funds. For FY2020, the Trump Administration again requested no OCO funds for foreign affairs agencies.

Since FY2012, OCO has ranged from a low of 14% of the total budget request in FY2014 to a high of 36% in FY2017, when the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015, P.L. 114-74) set nonbinding OCO minimums for FY2016 and FY2017. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018, P.L. 115-123) raised discretionary spending limits for FY2018 and FY2019 and extended direct spending reductions through FY2027. With the raised spending limits, the Trump Administration's FY2019 budget request did not include the OCO designation for any foreign assistance funds. However, Congress has continued to appropriate OCO funds, including $8.0 billion in FY2019. The Administration's FY2020 budget request also does not request OCO funds for State-Foreign Operations appropriations.

The BCA and BBAs have had an effect on foreign affairs funding levels and may have future implications. The Budget Control Act of 2011 sets limits on discretionary spending through FY2021 for defense and nondefense funding categories. Because OCO funds are not counted against the discretionary spending limits, the BCA has put downward pressure on SFOPS enduring/base funds, while OCO has increasingly funded other foreign affairs activities. In addition, the 2015 BBA significantly increased FY2016 and FY2017 OCO funding for foreign affairs over the requested funding levels in FY2015 and FY2016, further encouraging a migration of funds for ongoing activities into OCO-designated accounts. However, the 2018 BBA has had the opposite effect on foreign affairs OCO, allowing lawmakers to shift OCO funding back into enduring/base accounts.

|

Figure 3. OCO/Supplementals as a Percentage of Total State-Foreign Operations Funding (In billions of current dollars) |

|

|

Source: The Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs, FY2012-FY2020. Notes: FY2015 includes the Ebola Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 113-235); FY2016 includes the Zika Response Supplemental Funding (P.L. 114-223); and FY2017 includes the Security Assistance Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-254) OCO funding. |

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report was originally written by Susan B. Epstein, Specialist in Foreign Policy.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more detail on the latest SFOPS appropriations, see CRS Report R45168, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs: FY2019 Budget and Appropriations, by Susan B. Epstein, Marian L. Lawson, and Cory R. Gill. |

| 2. |

H.R. 5522, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2007, in the 109th Congress, was the first appropriations legislation to combine both State Operations and Foreign Operations funding into one bill. |

| 3. |

In years when authorizations are not passed, the laws requiring authorization are waived in the appropriations measure. Laws requiring authorization, but waived within the General Provisions of the appropriations law since 2003, include Section 10 of P.L. 91-672, Section 15 of the State Department Basic Authorities Act of 1956, Section 313, and Section 504(a)(1) of the National Security Act of 1947 (50 U.S.C. 3094(a)(1)). |

| 4. |

FY2003 was the last time Congress passed comprehensive foreign relations authorization legislation. In some years, foreign aid has been included within foreign relations authorization legislation. Prior to 1985, the most recent year Congress enacted foreign aid authorization legislation, Congress typically authorized foreign aid separately. |

| 5. |

The 114th Congress passed the Department of State Authorities Act, Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-323), signed into law in December 2016. This was not a comprehensive foreign relations bill, as it did not include authorization of appropriations. |

| 6. |

For further discussion on the various SFOPS components, see CRS Report R40482, Department of State, Foreign Operations Appropriations: A Guide to Component Accounts, by Cory R. Gill and Marian L. Lawson. |

| 7. |

For further discussion, see CRS Report R40213, Foreign Aid: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy, by Curt Tarnoff and Marian L. Lawson. |

| 8. |

An emergency supplemental for Ebola was passed in FY2015 (P.L. 113-235); Zika Response supplemental funding was passed in FY2016 (P.L. 114-223); and supplemental OCO funding was included in the Security Assistance Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-254) in FY2017. |

| 9. |

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA, P.L. 112-25) was the result of negotiations between President Obama and Congress to raise the debt ceiling by at least $2.1 trillion and reduce spending by that amount over a 10-year period between FY2012 and FY2021. The BCA established spending limits for each budget function (international affairs is function 150). If in a given year, the spending limits are not raised and the caps are not met, sequestration would be triggered. For more information on the BCA as it relates to the foreign affairs budget, see CRS Report R42994, The Budget Control Act, Sequestration, and the Foreign Affairs Budget: Background and Possible Impacts, by Susan B. Epstein. |

| 10. |

Executive Budget Summary, Function 150 & Other International Programs, Fiscal Year 2013, p. 137. |

| 11. |

For more information on OCO, its history, and current status, see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, by Brendan W. McGarry and Susan B. Epstein. |