Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from August 31, 2018 to November 9, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction and Issues for Congress

- Country Overview and the Erdogan Era

- Erdogan's Expanded Powers and June 2018 Victory

- Economy

- Overview

- Currency Decline: U.S.-Turkey Crisis and Sanctions

- Energy

- The Kurdish Issue

- Background

- Government Approaches to the Kurds

- Religious Minorities

- Christians and Jews

- Alevis

- U.S.-Turkey Relations: Questions about Ally Status

- U.S./NATO Cooperation with Turkey

- Overview

- U.S. Arms Sales and Aid to Turkey

- Possible S-400 Acquisition from Russia

- Selected Points of Bilateral Tension

- Turkey's Strategic Orientation and Foreign Policy

- Sanctions, Pastor Brunson, and Other Criminal Cases

- May 2017 Security Detail Incident in Washington, DC

- Legislation and Congressional Proposals

- Report: U.S.-Turkey Relations and F-35 Program (FY2019 NDAA)

- Conditioning F-35 Transfer on S-400 Decision (Senate Appropriations)

- Possible Restrictions Against Turkish Officials Entering the United States (Senate Appropriations)

- Possible U.S. Opposition to Assistance to Turkey from Selected International Financial Institutions (S. 3248)

- Syria

- Background

- Assessment

- Turkish Foreign Policy

- Russia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- European Union

- Armenia

- Cyprus and Greece

- Other International Relationships

Figures

Appendixes

- Appendix A. Profiles of Key Figures in Turkey

- Appendix B. Significant U.S.-Origin Arms Transfers or Possible Arms Transfers to Turkey

- Appendix C. Congressional Committee Reports of Resolutions Using the Word "Genocide" in Relation to Events Regarding Armenians in the Ottoman Empire from 1915 to 1923

Summary

Turkey, a NATO ally since 1952, significantly affects a number of key U.S. national security issues in the Middle East and Europe. U.S.-Turkey relations have worsened throughout this decade over several matters, including Syria's civil war, Turkey-Israel tensions, Turkey-Russia cooperation, and various Turkish domestic developments. The United States and NATO have military personnel and key equipment deployed to various sites in Turkey, including at Incirlik air base in the southern part of the country.

Bilateral ties have reached historic lows in the summer of 2018. The major flashpoint has been a Turkish criminal case against American pastor Andrew Brunson. U.S. sanctions on Turkey related to the Brunson case and responses by Turkey and international markets appear to have seriously aggravated an already precipitous drop in the value of Turkey's currency.

Amid this backdrop, Congress has actively engaged on several issues involving Turkey, including the following:

- Turkey's possible S-400 air defense system acquisition from Russia.

- Turkey's efforts to acquire U.S.-origin F-35 Joint Strike Fighter aircraft and its companies' role in the international F-35 consortium's supply chain.

- Complex U.S.-Turkey interactions in Syria involving several state and non-state actors, including Russia and Iran. Over strong Turkish objections, the United States continues to partner with Syrian Kurds linked with Kurdish militants in Turkey, and Turkey's military has occupied large portions of northern Syria to minimize Kurdish control and leverage.

- Turkey's domestic situation and its effect on bilateral relations. In addition to Pastor Brunson, Turkey has detained a number of other U.S. citizens (most of them dual U.S.-Turkish citizens) and Turkish employees of the U.S. government. Turkish officials and media have connected these cases to the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, and to Fethullah Gulen, the U.S.-based former cleric whom Turkey's government has accused of involvement in the plot.

In the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, P.L. 115-232) enacted in August 2018, Congress has required a comprehensive report from the Trump Administration on (1) U.S.-Turkey relations, (2) the potential S-400 deal and its implications for U.S./NATO activity in Turkey, (3) possible alternatives to the S-400, and (4) various scenarios for the F-35 program with or without Turkey's participation. Other proposed legislation would condition Turkey's acquisition of the F-35 on a cancellation of the S-400 deal (FY2019 State and Foreign Operations Appropriations Act, S. 3180), place sanctions on Turkish officials for their role in detaining U.S. citizens or employees (also S. 3180), and direct U.S. action at selected international financial institutions to oppose providing assistance to Turkey (Turkey International Financial Institutions Act, S. 3248). The S-400 deal might also trigger sanctions under existing law (CAATSA).

The next steps in the fraught relations between the United States and Turkey will take place in the context of a Turkey in political transition and growing economic turmoil. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has dominated politics in the country since 2002, won reelection to an empowered presidency in June 2018. Given Erdogan's consolidation of power, observers now question how he will govern a polarized electorate and deal with the foreign actors who can affect Turkey's financial solvency, regional security, and political influence. U.S. officials and lawmakers can refer to Turkey's complex history, geography, domestic dynamics, and international relationships in evaluating how to encourage Turkey to align its policies with U.S. interests.

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

November 9, 2020

U.S.-Turkey tensions have raised questions about the future of bilateral relations and have led to congressional action against Turkey, including informal holds on major new

Jim Zanotti

arms sales (such as upgrades to F-16 aircraft) and efforts to impose sanctions.

Specialist in Middle

Nevertheless, both countries’ officials emphasize the importance of continued U.S.-

Eastern Affairs

Turkey cooperation and Turkey’s membership in NATO. Observers voice concerns

about the largely authoritarian rule of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Clayton Thomas

Turkey’s polarized electorate could affect Erdogan’s future leadership. His biggest

Analyst in Middle Eastern

challenge may be structural weaknesses in Turkey’s economy—including a sharp

Affairs

decline in Turkey’s currency—that have worsened since the Coronavirus Disease 2019

pandemic began. The following are key factors in the U.S.-Turkey relationship.

Turkey’s strategic orientation and U.S./NATO basing. Traditionally, Turkey has relied closely on the United States and NATO for defense cooperation, European countries for trade and investment, and Russia and Iran for energy imports. A number of complicated situations in Turkey’s surrounding region—including those involving Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh (a region disputed by Armenia and Azerbaijan), and Eastern Mediterranean energy exploration—affect its relationships with the United States and other key actors, as Turkey seeks a more independent role. President Erdogan’s concerns about maintaining his parliamentary coalition with Turkish nationalists may partly explain his actions in some of the situations mentioned above. Turkey-Russia cooperation has grown in some areas. However, Turkish efforts to counter Russia in several theaters of conflict at relatively low cost—using domestically produced drone aircraft (reportedly with some U.S. components) and Syrian mercenaries—suggest that Turkey-Russia cooperation is situational rather than comprehensive in scope.

Since Turkey’s 2019 agreement with Libya’s Government of National Accord on Eastern Mediterranean maritime boundaries, and its increased involvement in Libya’s civil war, Turkey’s tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean with countries such as Cyprus and Greece have become more intertwined with its rivalry with Sunni Arab states such as Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Saudi Arabia. In this context, some observers have advocated that the United States explore alternative basing arrangements for U.S. and NATO military assets in Turkey—including a possible arsenal of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons at Incirlik Air Base. The August 2020 agreement between Israel and the UAE to normalize their ties could increase tensions between Turkey and these other regional U.S. allies and partners.

Russian S-400 purchase and U.S. responses. Turkey’s purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air defense system led to its removal by the United States from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program. The S-400 deliveries that began in July 2019 also reportedly triggered informal congressional holds on major new arms sales. If Turkey transitions to major Russian weapons platforms with multi-decade lifespans, it is unclear how it can stay closely integrated with NATO on defense matters. The S-400 deal could trigger U.S. sanctions under Section 231 of the Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA, title II of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAATSA; P.L. 115-44). President Trump has reportedly delayed CAATSA sanctions while seeking to persuade Turkey to refrain from operating the S-400. It is unclear how sanctions against Turkey could affect its economy, trade, and defense procurement. Future U.S. actions in response to Turkey’s acquisition of the S-400 could affect U.S. arms sales and sanctions with respect to other U.S. partners who have purchased or may purchase advanced weapons from Russia—including India, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

Congressional initiatives and other U.S. actions. Congressional and executive branch action on arms sales, sanctions, or military basing regarding Turkey and its rivals could have implications for bilateral ties, U.S. political-military options in the region, and Turkey’s strategic orientation and financial well-being. How closely to engage Erdogan’s government could depend on U.S. perceptions of his popular legitimacy, likely staying power, and the extent to which a successor might change his policies in light of geopolitical, historical, and economic considerations.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 35 link to page 38 link to page 6 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 26 link to page 30 link to page 33 link to page 35 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Introduction and Issues for Congress .............................................................................................. 1 Country Overview and the Erdogan Era ......................................................................................... 2

Political Assessment .................................................................................................................. 4 Economic Assessment ............................................................................................................... 7

Overview ............................................................................................................................. 7 Energy ................................................................................................................................. 8

The Kurdish Issue .................................................................................................................... 11

Background ........................................................................................................................ 11 Government Approaches to the Kurds .............................................................................. 12

Religious Minorities ................................................................................................................ 12

Halki Seminary and Hagia Sophia .................................................................................... 13 Alevis ................................................................................................................................ 14

Turkey’s Strategic Orientation and Military Involvement ............................................................ 14

U.S./NATO Presence ............................................................................................................... 16 Issues with Other U.S./NATO Allies ....................................................................................... 18

Eastern Mediterranean and Offshore Natural Gas ............................................................ 18 Middle East and Libyan Civil War .................................................................................... 19

The Syrian Conflict ................................................................................................................. 20

Countering the Syrian Kurdish YPG................................................................................. 21 Turkish-Occupied Areas and Idlib .................................................................................... 23

Role in Nagorno-Karabakh Dispute: Armenia and Azerbaijan ............................................... 24 Turkish Defense Procurement ................................................................................................. 25

Background ....................................................................................................................... 25 U.S. Arms Sales and Aid ................................................................................................... 26 Key Weapons Systems and Turkey’s Relationships: S-400, F-35, Patriot ........................ 27 Drones: Domestic Production, U.S. and Western Components, and Exports ................... 28

Congressional Scrutiny: U.S. Responses and Options .................................................................. 31 Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 34

Figures Figure 1. Turkey at a Glance ........................................................................................................... 2 Figure 2. Turkey: 2018 Parliamentary Election Results in Context ................................................ 6 Figure 3. Turkish Natural Gas Imports by Country ......................................................................... 9 Figure 4. Turkey and Southeastern European Gas Infrastructure .................................................. 10 Figure 5. Map of U.S. and NATO Military Presence in Turkey .................................................... 17 Figure 6. Competing Claims in the Eastern Mediterranean .......................................................... 19 Figure 7. Syria-Turkey Border ...................................................................................................... 22 Figure 8. Arms Imports as a Share of Turkish Military Spending ................................................. 26 Figure 9. Bayraktar TB2 Drone ..................................................................................................... 29 Figure 10. Turkish Military Export Statistics ................................................................................ 31

Congressional Research Service

link to page 39 link to page 47 link to page 50 link to page 52 link to page 52 link to page 53 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Appendixes Appendix A. Turkey’s Foreign Policy Relationships .................................................................... 35 Appendix B. Profiles of Key Figures in Turkey ............................................................................ 43 Appendix C. Timeline of Turkey’s Involvement in Syria (2011-2020) ........................................ 46 Appendix D. Significant U.S.-Origin Arms Transfers or Possible Arms Transfers to

Turkey ........................................................................................................................................ 48

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 49

Congressional Research Service

link to page 39 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Introduction and Issues for Congress While Introduction and Issues for Congress

U.S.-Turkey ties, have always been complicated, tensions in recent years have produced a number of crises and have led to questions about the status and future of the bilateral relationship. complicated, appear to have reached crisis levels in the summer of 2018. Although the United States and Turkey, NATO allies since 1952, share some vital interests, harmonizing priorities can be difficult. These priorities sometimes diverge irrespective of who leads the two countries, based on contrasting geography, threat perceptions, and regional roles. This report provides background information and analysis on the following topics:

Turkey’s domestic setting. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Islamist-

leaning Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, or AKP), in power since 2003, rule in a largely authoritarian manner. Erdogan has steadily consolidated control through elections and increasing dominance over the country’s security apparatus and other key institutions. Erdogan’s biggest challenge may be structural weaknesses in Turkey’s economy—including a sharp decline in Turkey’s currency—that have worsened since the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic began. Concerns about maintaining his political support and the AKP’s parliamentary coalition with the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyet Halk Partisi, or MHP) may partly explain Erdogan’s policies in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, and his efforts to weaken domestic minorities (including the Kurds) and opponents.

Turkey’s strategic orientation. Policy differences and public acrimony between

Turkey and the United States have fueled concern about their relationship and about Turkey’s status as a U.S. ally and NATO member. Turkey appears to compartmentalize its relationships with United States, Russia, the European Union (EU), China, and its regional neighbors depending on various circumstances (see Appendix A). For example, Turkey has purchased an S-400 surface-to-air defense system from Russia and cooperates with it in some other areas, but also has blocked or opposed Russian interests in Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh (a region disputed by Armenia and Azerbaijan).

Congressional scrutiny and U.S. responses and options. U.S.-Turkey tensions

have led to a number of congressional initiatives and other U.S. actions. These include informal congressional holds and proposed legislation aimed at restricting arms sales, possible sanctions on Turkey, and other efforts to limit strategic cooperation or empower Turkey’s rivals.

According to the Turkish Coalition of America, a non-governmental organization that promotes positive Turkish-American relations, as of November 2020, there are at least 101 Members of the House of Representatives (98 of whom are voting Members), and four Senators in the Congressional Caucus on Turkey and Turkish Americans.1 Reduced caucus membership numbers since 2018 may reflect the increased difficulties in bilateral relations and congressional concerns about Turkey’s trajectory under President Erdogan.

1 See http://www.tc-america.org/in-congress/caucus.htm.

Congressional Research Service

1

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 1. Turkey at a Glance

Geography

Area: 783,562 sq km (302,535 sq. mile), slightly larger than Texas

People

Population: 82,017,514. Most populous cities: Istanbul 15.2 mil, Ankara 5.1leads the two countries, based on contrasting geography, threat perceptions, and regional roles. Current points of tension in the relationship include the following:

- Sanctions and worsening U.S.-Turkey relations. Policy differences and public acrimony between the two countries have fueled concern about their relationship and about Turkey's status as a U.S. ally. In August 2018, the Trump Administration levied sanctions against Turkey in connection with the continued detention of Andrew Brunson, an American pastor charged with terrorism. The sanctions appear to have quickened the decline in value of Turkey's already depreciating currency, which has lost considerable value against the dollar (see "Currency Decline: U.S.-Turkey Crisis and Sanctions" below). The crisis in bilateral relations has appeared to deepen as Turkey has retaliated with its own sanctions, and as each country has raised tariffs on imports from the other.

- Congressional initiatives.1 Within the tense bilateral context, Congress has required the Trump Administration—in the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, P.L. 115-232)—to report on the status of U.S.-Turkey relations. Also, some Members of Congress have proposed legislation to limit arms sales and strategic cooperation—particularly regarding the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter—or to place additional sanctions on Turkish officials. While Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and other Turkish leaders have sharply criticized U.S. policies on many issues, questions in U.S. public debate about Turkey's status as an ally and its relationship with Russia have intensified.

- Possible S-400 acquisition from Russia. Turkey's planned purchase of an S-400 air defense system from Russia could trigger U.S. sanctions under existing law. The possible transaction has sparked broader concern over Turkey's relationship with Russia and implications for NATO. U.S. officials seek to prevent the deal, and reports suggest that they may be offering alternatives to Turkey such as Patriot air defense systems.

- Syria and the Kurds. Turkey's political stances and military operations in Syria have fed U.S.-Turkey tensions, particularly regarding Kurdish-led militias supported by the United States against the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIS/ISIL) over Turkey's strong objections.

- Turkey's domestic trajectory and financial distress. President Erdogan rules in an increasingly authoritarian manner. Presidential and parliamentary elections held in June 2018 consolidated Erdogan's power pursuant to constitutional changes approved in a controversial 2017 referendum. Meanwhile, even before the U.S. sanctions in August, Turkey's currency had fallen considerably in value amid concerns about rule of law, regional and domestic political uncertainty, significant corporate debt, and a stronger dollar.

|

|

Geography |

Area: 783,562 sq km (302,535 sq. mile), slightly larger than Texas |

|

People |

7 mil. % of Population 14 or Younger: 23.4% Ethnic Groups: Turks 70%-75%; Kurds 19%; Other minorities 7%-12% (2016) Religion: Muslim 99.8% (mostly Sunni), Others (mainly Christian and Jewish) 0.2% (2017) Literacy: |

|

Economy |

93.5%) (2017)

Economy

GDP Per Capita (at purchasing power parity): $ 26,768 Real GDP Growth: -3.9% (2020), 3.6% (2021 projection) Inflation: 11.9% Unemployment: 14.6% Inflation: 15.4% Unemployment: 10.7% Budget Deficit as % of GDP: 5.6% Public Debt as % of GDP: 38.0% Current Account Deficit as % of GDP: International reserves: $74 billion |

3.7% International currency reserves: $81.9 bil ion

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Map boundaries and information generated by [author name scrubbed]Hannah Fischer using Department of State Boundaries (2011); Esri (2014); ArcWorld (2014); DeLorme (2014). Fact information (2018 2020 estimates unless otherwise specified) from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database; Turkish Statistical Institute; World Bank; Database; Economist Intelligence Unit; and Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook.

Country Overview and the Erdogan Era

Turkey'’s large, and diversified economy, Muslim strong military, Muslim-majority population, and geographic position straddling Europe and the Middle East make it a significant regional power. ImportantFor decades since its founding in the 1920s, the Turkish republic had relied upon its military, judiciary, and other bastions of its Kemalist (a term inspired by Turkey’s republican founder,

Congressional Research Service

2

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk) “secular elite” to protect it from political and ideological extremes—sacrificing at least some of its democratic vitality in the process. Major political developments in Turkey over the past two decades appear to stem partly fromTurkey since 2002 have occurred within the context of significant socioeconomic changes that began in the 1980s. The military-guided governments that came to power after Turkey'’s 1980 coup helped establish Turkey'’s export-driven economy. This led to the gradual empowermentpolitical awakening of a largely Sunni Muslim middle class from Turkey'’s Anatolian heartland.

These socioeconomic changes helped fuel political transformation

These changes helped fuel Turkey’s dramatic transformation after 2002, led by the Islamist-leaning AKPleaning Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, or AKP) and President (formerly Prime Minister) Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The AKP won governing majorities four times—2002, 2007, 2011, and 2015—during a period in which Turkey'’s economy generally enjoyed growth and stability. For decades since its founding in the 1920s, the Turkish republic had relied upon its military, judiciary, and other bastions of its Kemalist (a term inspired by Turkey's republican founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk) "secular elite" to protect it from political and ideological extremes—sacrificing at least some of its democratic vitality in the process.

Erdogan has

During his first decade as Turkey’s leader, Erdogan worked to reduce the political power of the "“secular elite" and has.” He subsequently clashed with other possible rival power centers, including previous allies in the Fethullah Gulen movement.22 Domestic polarization has intensified sinceafter 2013: nationwide antigovernment protests that began in Istanbul'’s Gezi Park took place that year, and corruption allegations later surfaced against a number of Erdogan'’s colleagues in and out of government.3

3

After Erdogan became president in August 2014 via Turkey'’s first-ever popular presidential election, he claimed a mandate for increasing his power and pursuing a "“presidential system"” of governance. Analyses of Erdogan sometimes characterize him as one or more of the following: a pragmatic populist, a protector of the vulnerabletraditionally marginalized groups, a budding authoritarian, or an Islamic ideologue.4 While there may be some similarities between Turkey under Erdogan and countries like Russia, Iran, or China, some factors distinguish Turkey from them. For example, unlike Russia or Iran, Turkey’s economy cannot rely on significant rents from natural resources if foreign sources of revenue or investment dry up. Unlike Russia and China, Turkey does not have nuclear weapons under its command and control. Additionally, unlike all three others, Turkey’s economic, political, and national security institutions and traditions have been closely connected with those of the West for decades.

Erdogan’s consolidation of power has continued and arguably accelerated since 2014. After Erdogan survived a July 2016 coup attempt staged by rogue military officers, Turkey’s parliament approved a state of emergency. The state of emergency enabled Turkish authorities to target many of Erdogan’s political opponents and civil society critics beyond those with proven connections to the coup attempt. More than 60,000 Turks were arrested and 130,000 dismissed from government posts.5 Erdogan and his supporters also gained greater control over the country’s government, security, educational, media, and business institutions.6 After winning controversial victories in an April 2017 constitutional referendum and June 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections, (see below), Erdogan’s presidential powers expanded. In July 2018, parliament lifted the state of emergency, but enacted many of its features into law for another three years. However, the positive economic conditions that helped propel Erdogan’s early political popularity have turned 2 For more on Gulen and the Gulen movement, see CRS In Focus IF10444, Fethullah Gulen, Turkey, and the United States: A Reference, by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

3 Freedom House, Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey, February 3, 2014. 4 See, e.g., Soner Cagaptay, The New Sultan: Erdogan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2017; Burak Kadercan, “Erdogan’s Last Off-Ramp: Authoritarianism, Democracy, and the Future of Turkey,” War on the Rocks, July 28, 2016.

5 Carlotta Gall, “Turkish Leader’s Next Target in Crackdown on Dissent: The Internet,” New York Times, March 4, 2018.

6 Kareem Fahim, “As Erdogan prepares for new term, Turkey dismisses more than 18,000 civil servants,” Washington Post, July 8, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 47 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

into largely negative ones in the past two years, raising questions about how much popularity he can maintain over time.

Human Rights Concerns in Turkey

During the second decade of President Erdogan’s leadership of Turkey, domestic and international observers have raised claims about human rights violations that they assert—amid some opposing views—are more widespread and systematic than in the country’s past eras. During the 2000s, some of these observers expressed hopes that reducing the role of Turkey’s military in its institutions of civilian governance could lead to a more liberal democracy—and perhaps European Union membership. Since then, however, many have voiced worries about the largely unchecked, Islamist-tinged civilian rule that Erdogan justifies on the basis of elections of questionable legitimacy.7 Official analyses from the United States and European Union, as well as unofficial reports from human rights monitors and other third parties, identify a number of issues,8 including the fol owing:

Practices by the government or its supporters (e.g., media control, censorship, intimidation, voter fraud or manipulation) that may undermine the “free and fair” nature of Turkey’s elections.

Arbitrary arrest, indefinite detention, and improper interrogation practices (including instances of torture), and some general erosion of the justice sector’s independence and evidentiary standards.

Imprisonment, forced closures or asset transfers, and other measures targeting journalists, civil society leaders, Erdogan’s political opponents, and independent institutions. The government justifies some measures on the basis of countering terrorism, even though sometimes those targeted appear to have had only minimal or superficial contacts with organizations classified by Turkey as terrorist groups—such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) or the Fethul ah Gulen movement.

Significant limits on the right to assemble and protest.

Conditions on and legal prosecution of content posted on key Internet and social media sites (i.e., YouTube, Facebook, Twitter).

Increased spending on Sunni Muslim religious (imam hatip) secondary schools, and expanded religious instruction in other schools.

As a member of the Council of Europe, Turkey agrees to accept the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), but has not done so in some cases.9 Specific concerns regarding the treatment of Turkey’s large ethnic Kurdish population and its religious minorities are discussed in various sections below.

Erdogan and various other key Turkish figures (including political party leaders) are profiled in Appendix B.

Political Assessment President Erdogan retains sweeping power over Turkey. However, he presides over a polarized electorate and faces substantial domestic and international criticism for governing in an authoritarian manner. Many Turks’ opposition to his continued rule, along with Turkey’s ongoing economic challenges, could undermine Turkey’s future stability and prosperity, even if it does not lead to Erdogan leaving office.10

7 See, e.g., “Democracy Talks: Mustafa Akyol, Author and Journalist,” George W. Bush Presidential Center, April 28, 2020.

8 Department of State, “Turkey,” Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2019; European Commission, Turkey 2020 Report, October 6, 2020; Human Rights Watch, “Turkey,” World Report 2020; Freedom House, “Turkey,” Freedom in the World 2020.

9 “Turkey’s Erdogan says ECHR ruling on jailed politician supports terrorism,” Reuters, November 21, 2018. 10 See, e.g., Max Hoffman, “Turkey’s President Erdoğan Is Losing Ground at Home,” Center for American Progress, August 24, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 16 link to page 16 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

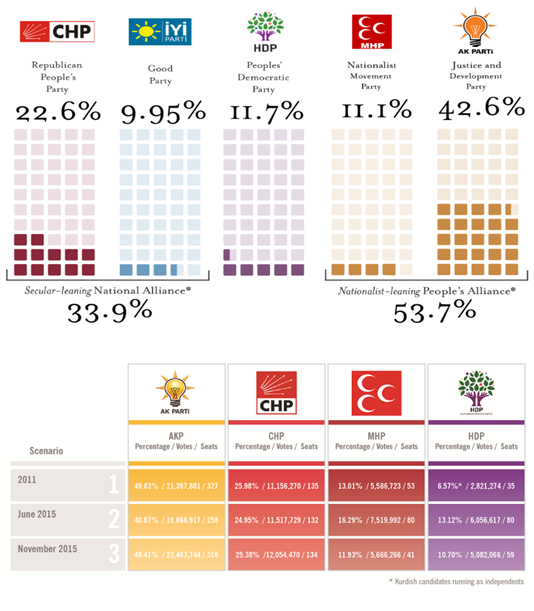

Erdogan won the June 2018 presidential elections with about 53% of the vote. To obtain a parliamentary majority in the June 2018 elections, Erdogan’s AKP relied on the MHP (see Figure 2 below). The MHP is the country’s traditional Turkish nationalist party, and is known for opposing political accommodation with the Kurds. The MHP also had provided key support for the constitutional amendments approved in 2017. Erdogan started courting nationalist constituencies around the time Kurdish voter support for the AKP decreased in 2015 with the end of Turkey-PKK peace negotiations and the resumption of armed conflict (see “Government Approaches to the Kurds” below). Some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced in connection with the June 2018 elections,11 which was also the case with the April 2017 constitutional referendum.12

The Post-2018 Presidential System

Two years into the presidential system in Turkey, it is unclear, a budding authoritarian, an indispensable figure, an Islamic ideologue.4

|

July 2016 Failed Coup On July 15-16, 2016, elements within the Turkish military operating outside the chain of command mobilized air and ground forces in a failed attempt to seize political power from President Erdogan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim.5 Resistance by security forces loyal to the government and civilians in key areas of Istanbul and Ankara succeeded in foiling the coup,6 with around 270 killed on both sides.7 Turkish officials publicly blame the plot on military officers with alleged links to Fethullah Gulen—formerly a state-employed imam in Turkey and now a permanent U.S. resident. Allies at one point, the AKP and Gulen's movement had a falling out in 2013 that complicated existing struggles in Turkey regarding power and political freedom. Gulen denied taking part in the July 2016 coup plot, but acknowledged that he "could not rule out" involvement by some of his followers.8 Gulen's U.S. residency and Turkish dissatisfaction with the U.S. response to the coup plot probably intensified anti-American sentiment, which Erdogan has actively used to bolster his domestic appeal. Shortly after the failed coup, Erdogan placed Turkey's military and intelligence institutions more firmly under the civilian government's control.9 In the two years since, Turkey's government has dismissed around 130,000 Turks from government posts, detained more than 60,000,10 and taken over or closed various businesses, schools, and media outlets.11 The government largely justified its actions by claiming that those affected are associated with the Gulen movement, even though the measures may be broader in terms of whom they directly impact.12 The UN and others have expressed concern over reports alleging that some detainees have been subjected to beatings, torture, and other human rights violations.13 |

Erdogan's consolidation of power has continued. He outlasted the July 2016 coup attempt, and then scored victories in the April 2017 constitutional referendum and the June 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections. U.S. and European Union officials have expressed a number of concerns about rule of law and civil liberties in Turkey,14 including the government's influence on media15 and Turkey's reported status as the country with the most journalists in prison.16

While there may be some similarities between Turkey under Erdogan and countries like Russia, Iran, or China, some factors distinguish Turkey from them. For example, unlike Russia or Iran, Turkey's economy cannot rely on significant rents from natural resources if foreign sources of revenue or investment dry up. Unlike Russia and China, Turkey does not have nuclear weapons under its command and control. Additionally, unlike all three others, Turkey's economic, political, and national security institutions and traditions have been closely connected with those of the West for decades.

Erdogan and various other key Turkish figures (including political party leaders) are profiled in Appendix A.

Erdogan's Expanded Powers and June 2018 Victory

In an election that President Erdogan moved up to June 2018 from November 2019, he was reelected to a five-year presidential term with about 53% of the vote. The election reinforced his dominant role in Turkish politics because a controversial April 2017 popular referendum had determined that the presidential victor would govern with expanded powers. To obtain a parliamentary majority in the June elections, Erdogan's AKP relied on the Nationalist Action Party (Milliyet Halk Partisi, or MHP) (see Figure 2 below). The MHP is the country's traditional Turkish nationalist party, and is known for opposing political accommodation with the Kurds. The MHP also had provided key support for the constitutional amendments approved in 2017. If the MHP's role in parliament influences policy, the government may be less inclined to make conciliatory overtures to the Kurdish militant group PKK (Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan, or Kurdistan Workers Party).17 However, given his expanded powers, Erdogan might be less sensitive to parliamentary developments.

|

|

|

Sources: Institute for the Study of War; Bipartisan Policy Center. Note: Each square represents 12 parliamentary seats. |

Most of the constitutional changes, which significantly affect Turkey's democracy and will probably have ripple effects for Turkey's foreign relations, went into effect after the June 2018 elections. Among other things, the changes

- eliminate the position of prime minister, with the president serving as both chief executive and head of state;

- allow the president to appoint ministers and other senior officials without parliamentary approval;

- prohibit ministers from serving as members of parliament;

- transfer responsibility for preparing the national budget from parliament to the president; and

- increase the proportion of senior judges chosen by the president from about half to over two-thirds.

The New Presidential System

In July 2018, President Erdogan appointed Fuat Oktay as vice president. Oktay had previously served as undersecretary in the prime ministry. In making his other appointments, Erdogan reduced the number of government ministries from 25 to 16, and established eight presidential directorates that overlap with various ministry portfolios.20 |

As with the 2017 constitutional referendum,21 some allegations of voter fraud and manipulation surfaced in connection with the 2018 elections.22 Muharrem Ince of the Republican People's Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, or CHP), Erdogan's main challenger in the presidential race, noted these allegations in his concession message. He claimed that the campaign, which was conducted under a state of emergency and featured media coverage disproportionately favoring Erdogan and the AKP, was "unfair." However, Ince also said that the alleged manipulation did not affect the outcome.23

Economy

Overview

The AKP's political successes have been

11 OSCE, International Election Observation Mission, Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions, Turkey, Early Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, June 24, 2018 (published June 25, 2018).

12 Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Limited Referendum Observation Mission Final Report, Turkey, April 16, 2017 (published June 22, 2017).

13 See, e.g., Chris Morris, “Turkey elections: How powerful will the next Turkish president be?” BBC News, June 25, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

5

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 2. Turkey: 2018 Parliamentary Election Results in Context

Sources: Institute for the Study of War; Bipartisan Policy Center. Note: Each square represents 12 parliamentary seats.

In 2019 local elections, the AKP maintained the largest share of votes but lost some key municipalities to opposition candidates from the secular-leaning Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, or CHP). The AKP’s most significant losses in those elections include the capital, Ankara, and Istanbul, Turkey’s largest city and economic hub. The Istanbul municipal election was particularly controversial: though CHP candidate Ekrem Imamoglu appeared to win a narrow victory in the March 2019 election, the AKP disputed his vote total and the election was annulled by the Supreme Electoral Council. In the closely watched June 2019 re-vote, Imamoglu won a decisive victory over AKP candidate and former Prime Minister Binali Yildirim.

Congressional Research Service

6

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

It is unclear to what extent, if at all, these losses were connected with Turkey’s economic troubles and represent a threat to Erdogan’s rule. Imamoglu and some other opposition mayors have national profiles and by some measures reportedly may rival Erdogan in popularity.14 Using access to information that their positions afford, they have claimed that their AKP predecessors engaged in corrupt and wasteful practices.15 Additionally, since the local elections, Ahmet Davutoglu and Ali Babacan, who are prominent former AKP figures from previous Erdogan-led governments, each have established new political parties that could weaken Erdogan’s hold on his conservative political base. Erdogan is up for reelection at the end of his term in 2023. He could call early elections at any time, but may be unlikely to do so unless a comfortable AKP victory seems assured.16

Economic Assessment

Overview

The AKP’s political successes during the 2000s were aided considerably by robust Turkish economic growth since the early 2000s. Growth rates have beenwere comparable at times to other major emerging markets, such as the BRIC economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Key Turkish businesses include diversified conglomerates (such as Koc and Sabanci) from traditional urban centers as well as "“Anatolian tigers"” (small- to medium-sized export-oriented companies) scattered throughout the country.

In the past decade, however, growth has at times slowed or reversed, and the Turkish economy has experienced significant volatility. The “low-hanging fruit”country. According to the World Bank, Turkey's economy ranked 17th worldwide in annual GDP in 2017; when Erdogan came to power in 2003, Turkey was ranked 21st.

However, despite a real GDP growth rate of over 7% in 2017, a number of indicators suggest that the Turkish economy may be entering a period of volatility and perhaps crisis, with potentially significant implications for the global economy.24 Some observers assert that the "low-hanging fruit"—numerous large infrastructure projects and the scaling up of low-technology manufacturing—that largely drove the previous decade'decade’s economic success ismay be unlikely to produce similar results going forward.25 Turkey's ’s relatively large current account deficit increases its vulnerability to higher borrowing costs.

Prospects are uncertain for how the economy and foreign investors will respond under Erdogan's new government Concerns about rule of law in Turkey and the possibility of U.S. sanctions may also drive volatility. In July 2018, Erdogan gave himself the power to appoint central bank rate-setters and appointed his son-in-law Berat Albayrak (the former energy minister) to serve as treasury and finance minister, exacerbating concerns about greater politicization of Turkey'’s monetary policy.26 17

The steady depreciation over several years of Turkey’s currency, the lira, has put further strain on the economy. As of November 2020, the value of the lira had declined nearly 30% for the year. With net foreign currency reserves probably in negative territory, and interest rates below the rate of inflation, analysts have predicted that Turkey will need to raise interest rates—perhaps dramatically—or seek significant external assistance to address its financial fragility.18 In November, Erdogan replaced Turkey’s central bank governor and Albayrak resigned as treasury and finance minister, fueling speculation about the likelihood of interest rate hikes despite Erdogan’s long-expressed disdain of them.19 Turkey unsuccessfully sought currency swap lines

14 Laura Pitel and Funja Guler, “Turkish opposition mayors outshine Erdogan with ‘kindness’ campaigns,” Financial Times, June 23, 2020.

15 Laura Pitel, “Turkish mayors accuse government of coronavirus cover-up,” Financial Times, August 30, 2020. 16 Nick Danforth, “The Outlook for Turkish Democracy: 2023 and Beyond,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 2020.

17 Marcus Ashworth, “Erdogan’s New Dynasty Makes Turkey Uninvestable,” Bloomberg, July 10, 2018. 18 Economist Intelligence Unit, Turkey country report (retrieved November 3, 2020). 19 Laura Pitel, “Shock change in Turkey’s economic leadership raises stakes for lira,” Financial Times, November 8,

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

from the U.S. Federal Reserve earlier in 2020, having relied to date for some liquidity on swaps from Qatar and China.20

Some observers have speculated that if investment dries up, Turkey may need to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a financial assistance package.27 This21 Erdogan has publicly rejected such speculation. Doing so would be a sensitive challenge for Erdogan because his political success story is closely connected with helping Turkey become independent from its most recent IMF intervention in the early 2000s.

Energy

Turkey’s importance as a regional energy transport hub makes it relevant for world energy markets while also providing Turkey with opportunities to satisfy its own domestic energy needs. With few hydrocarbon resources of its own, Turkey has been traditionally dependent on other countries for energy imports—particularly Russia and Iran. However, Turkey has significantly reduced its dependence on natural gas delivered via pipeline from Russia (see Figure 3),most recent IMF intervention in the early 2000s.28

Currency Decline: U.S.-Turkey Crisis and Sanctions29

The Turkish lira has depreciated significantly as of August 2018. Even before U.S. sanctions were enacted in August, Turkey's lira had faced a downward trend in value, with that trend becoming more pronounced around 2015. The lira's decline and accompanying inflation appear to have been driven in part by increasing its purchases of liquefied natural gas (LNG). From 2016 to June 2020, Russia’s share of Turkish natural gas imports reportedly fell from 50% to 14%, while U.S. LNG as a share of Turkey’s imports grew from 0% to 10%.22 Turkey faces challenges in maintaining and broadening its efforts at diversification, including some pertaining to long-term supply contracts and physical infrastructure. Additionally, Russia may retain leverage with Turkey on issues such as arms sales, nuclear energy, and regional crises (i.e., Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh).

2020.

20 Mustafa Sonmez, “Turkey’s ‘peg-legged’ foreign currency reserves,” Al-Monitor, July 6, 2020. 21 Bobby Ghosh, “Erdogan should break his IMF taboo,” Bloomberg, April 19, 2020. 22 Rauf Mammadov, “Turkey Makes Strides in Diversifying Its Natural Gas Imports,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Vol. 17, Issue 97, July 6, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 14

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Figure 3. Turkish Natural Gas Imports by Country

Source: Turkish Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EPDK), 2019 Annual Report

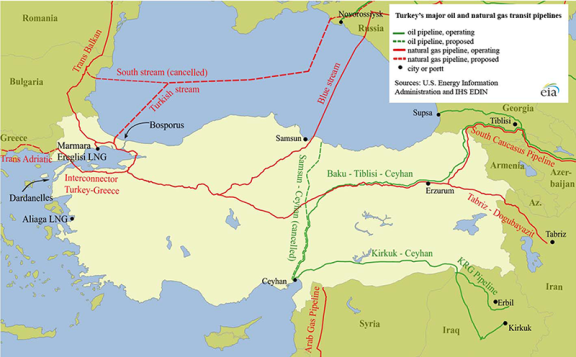

In January 2020, Presidents Erdogan and Putin inaugurated the TurkStream pipeline project (see Figure 4), which carries Russian natural gas across the Black Sea to southern and central Europe via Turkey.23 A planned second line is to extend northward as far as Austria. The Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. 115-44) authorizes sanctions on individuals or entities that invest in or engage in trade for the construction of Russian energy export pipelines. In October 2017, the Administration published guidance noting that Section 232 sanctions would not apply to projects for which contracts were signed prior to August 2, 2017, the date of CRIEEA’s enactment. However, in July 2020, the Administration updated that guidance and stated that while the initial TurkStream pipeline would not be subject to Section 232 sanctions, the second line would be. The FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, P.L. 116-92) enacted in December 2019 included, as Title LXXV, the Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act of 2019 (PEESA). This Act mandates sanctions—subject to a presidential waiver for national security reasons—for actors involved in laying subsea pipeline for TurkStream and possible successor projects on a going forward basis.

Turkey’s location has made it a key country in the U.S. and European effort to establish a southern corridor for pipelines to Europe that bypass Russia.24by a strengthening of the U.S. dollar and in part by concerns about Turkey's central bank independence and rule of law.30 These factors compounded the problem of the country's corporate debt, which stands at nearly 80% of GDP.31 The U.S. sanctions related to Pastor Andrew Brunson's case (see "Sanctions, Pastor Brunson, and Other Criminal Cases" below) and the historic crisis they may augur for U.S.-Turkey relations could be speeding the lira's decline. The lira has depreciated against the dollar by around 40% from January through August of 2018. In August, President Erdogan called on Turks to help with a "national struggle" by converting their savings from dollars and gold to lira.32

Energy

Turkey's importance as a regional energy transport hub makes it relevant for world energy markets while also providing Turkey with opportunities to satisfy its own domestic energy needs. Turkey's location has made it a key country in the U.S. and European effort to establish a southern corridor for natural gas transit from diverse sources.33 However, Turkey's dependence on other countries for energy—particularly Russia and Iran—may somewhat constrain Turkey from pursuing foreign policies in opposition to those countries.34 Construction on the Turkish Stream pipeline, which would carry Russian natural gas through Turkey into Europe, has proceeded apace since 2017; the first gas deliveries are projected for the end of 2019.35

As part of a broad Turkish strategy to reduce the country's dependence on foreign actors, Turkey appears to be trying to diversify its energy imports. In late 2011, Turkey and Azerbaijan reached deals for the transit of natural gas to and through Turkey via the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP);3625 the project was inaugurated in June 2018.37 The deals have attracted attention as a potentially significant precedent for transporting non-Russian, non-Iranian energy to Europe. In June 2013, the consortium that controls the Azerbaijani gas fields elected to have TANAP connect with a proposed Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to Italy, though political developments in Italy and elsewhere could complicate these arrangements.38 Turkey also has shown interest in importing natural gas from new fields26 As of September 2020, work is nearing completion on the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which is to transport

23 CRS In Focus IF11177, TurkStream: Russia’s Newest Gas Pipeline to Europe, by Sarah E. Garding et al. 24 Department of State press statement, “The Importance of Diversity in European Energy Security,” June 29, 2018. 25 The terms of the Turkey-Azerbaijan agreement specified that 565 billion-700 billion cubic feet (bcf) of natural gas would transit Turkey, of which 210 bcf would be available for Turkey’s domestic use. 26 “Leaders open TANAP pipeline carrying gas from Azerbaijan to Europe,” Hurriyet Daily News, June 12, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 22

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Azeri gas to Italy via TANAP.27 Difficult relations with Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt are likely to complicate Turkish efforts to play a larger role in the development and transport of natural gas in the Eastern Mediterranean (see “Eastern Mediterranean and Offshore Natural Gas” below).28

In August 2020, President Erdogan announced a Turkish discovery of offshore natural gas deposits in the Black Sea. It is unclear how this news might impact the situation in the Eastern Mediterranean, and possibly even developing its own gas fields, but difficult relations with Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt could hamper these efforts.39

Another part of Turkey' and Turkey’s overall energy policies.29 Even if the deposits can be accessed, commercially developing them for domestic consumption or trade could take years.30

Figure 4. Turkey and Southeastern European Gas Infrastructure

Source: Created by CRS using data from U.S. Department of State, HIS, ESRI, European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas, Bulgartransgaz.

Another part of Turkey’s strategy to become more energy independent is to increase domestic energy production. Turkey has entered into an agreement with a subsidiary of Rosatom (Russia's ’s state-run nuclear company) to have it build and operate what would be Turkey'’s first nuclear power plant in Akkuyu near the Mediterranean port of Mersin. Construction, which had been delayed for several years, began in April 2018, with operations expected to begin in 2023.4031 Some observers have expressed both skepticism about the construction timeline and concerns that the plant could provide Russia with additional leverage over Turkey.41 Japan has agreed to assist with the construction of a second nuclear power plant for Turkey in Sinop on the Black Sea coast, and Turkey is reportedly discussing cooperation with China to build a third plant in Thrace (northwest Turkey).42

|

|

The Kurdish Issue

Background

Ethnic Kurds reportedly constitute approximately 19% of Turkey'32 Plans for Japan to assist with

27 Shabnam Hasanova, “Where does the TAP gas pipeline project stand to date? The view from Baku,” Jamestown Foundation, June 30, 2020.

28 Yigal Chazon, “Race to exploit Mediterranean gas raises regional hackles,” Financial Times, March 9, 2018. 29 See John V. Bowlus, “Pulling Back the Curtain on Turkey’s Natural Gas Strategy,” War on the Rocks, August 26, 2020.

30 Selcan Hacaoglu, “Erdogan Unveils Biggest Ever Black Sea Natural Gas Discovery,” Bloomberg, August 21, 2020. 31 “Construction starts on 2nd unit of Turkey’s 1st nuclear power plant Akkuyu,” Daily Sabah, June 28, 2020. 32 See, e.g., Aram Ekin Duran, “Akkuyu nuclear plant: Turkey and Russia’s atomic connection,” Deutsche Welle, April 3, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

10

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

the construction of a second nuclear power plant in Sinop on the Black Sea coast were abandoned in January 2020.33

The Kurdish Issue

Background

Ethnic Kurds reportedly constitute approximately 19% of Turkey’s population.34s population.43 Kurds are largely concentrated in the relatively impoverishedless economically developed southeast, though populations are found in urban centers across the country. Some Kurds have been reluctant to recognize Turkish state authority in various parts of the southeast—a dynamic that also exists between Kurds and national governments in Iraq, Iran, and Syria. This reluctance and harsh Turkish government measures to quell Kurdish demands for rights have fed tensions that have occasionally escalated since the foundation of the republic in 1923. Since 1984, the Turkish military has periodically countered an on-and-off separatist insurgency and urban terrorism campaign by the PKK.4435 The initially secessionist demands of the PKK have since ostensibly evolved toward the less ambitious goal of greater cultural and political autonomy.4536 According to the U.S. government and European UnionEU, the PKK partially finances its activities through criminal activities, including its operation of a Europe-wide drug trafficking network.46

37

The struggle between Turkish authorities and the PKK was most intense during the 1990s, but has flared periodically since then. The PKK uses safe havens in areas of northern Iraq under the nominal authority of Iraq'’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The Turkish military's ’s approach to neutralizing the PKK has been routinely criticized by Western governments and human rights organizations for being overly hard on ethnic Kurds. Thousands have been imprisoned and hundreds of thousands have been displaced or had their livelihoods disrupted for suspected PKK involvement or sympathies.

33 “Turkey, Japan scrap partnership in Sinop nuclear plant in Turkey’s north,” Hurriyet Daily News, January 20, 2020. 34 CIA World Factbook, Turkey (accessed August 2020). 35 According to the International Crisis Group, around 14,000 Turks have been killed since fighting began in the early 1980s. This figure includes Turkish security personnel of various types and Turkish civilians (including Turkish Kurds who are judged not to have been PKK combatants). Estimates of PKK dead run from 33,000 to 43,000. International Crisis Group, “Turkey’s PKK Conflict: The Rising Toll” (interactive blog updated into 2018); Turkey: Ending the PKK Insurgency, Europe Report No. 213, September 20, 2011.

36 Kurdish nationalist leaders demand that any future changes to Turkey’s constitution (in its current form following the 2017 amendments) not suppress Kurdish ethnic and linguistic identity. The first clause of Article 3 of the constitution reads, “The Turkish state, with its territory and nation, is an indivisible entity. Its language is Turkish.” Because the constitution states that its first three articles are unamendable, even proposing a change could face judicial obstacles.

37 European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2018; U.S. Department of the Treasury Press Release, “Five PKK Leaders Designated Narcotics Traffickers,” April 20, 2011.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 47 Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Government Approaches to the Kurds

PKK Designations by U.S.

suspected PKK involvement or sympathies.

PKK Designations by U.S. Government

|

Government Approaches to the Kurds

Until the spring of 2015, Erdogan appeared to Until the spring of 2015, Erdogan appeared to

Government

prefer negotiating a political compromise with

Designation

Year

PKK leaders over the prospect of armed conflict.47

Foreign Terrorist

1997

38 However, against the backdrop of

Organization

PKK-affiliated Kurdish groups'’ success in Syria and domestic political considerations, Erdogan

Special y Designated

2001

then adopted a more confrontational political

Global Terrorist

stance with the PKK. Within that context, a complicated set of circumstances involving

Significant Foreign

2008

complicated set of circumstances involving

Narcotics Trafficker

terrorist attacks and mutual suspicion led to a resumption of violence between government forces and the PKK in the summer of 2015. As a result of the violence, which has been concentrated in southeastern Turkey and has tapered off somewhat since latewas most intense from 2015 to 2016, hundreds of fighters and civilians have died.4839 In addition to mass population displacement, infrastructure in the southeast has suffered significant damage. U.S. officials, while supportive of Turkey'’s prerogative to defend itself from attacks, have advised Turkey to show restraint and proportionality in its actions.49

40

Under the state of emergency enacted after the failed July 2016 coup attempt, Turkey's ’s government cracked down on Turkey'’s Kurdish minority. DozensSince then, dozens of elected Kurdish mayors werehave been removed from office and replaced with government-appointed "“custodians."” In November 2016, the two then-co-leaders of the pro-Kurdish HDPPeoples’ Democratic Party (Halklarin Demokratik Partisi, or HDP) were arrested along with nine other parliamentarians under various charges of crimes against the state.; some remain imprisoned, along with other party leaders and members who have been detained on similar charges.41 Turkish officials routinely accuse Kurdish politicians of support for the PKK, but these politicians generally deny close ties.

The future trajectory of Turkey-PKK dealings may depend on a number of factors, including

-

which Kurdish figures and groups (imprisoned PKK founder Abdullah Ocalan

[profiled

inin AppendixA]B], various PKK militant leaders, the professedly nonviolent HDP) are most influential in driving events; Erdogan' Erdogan’s approach to the issue, which has alternated between conciliation and confrontation; and-

possible incentives to Turkey

'’s government and the Kurds from the United States or other actors for mitigating violence and promoting political resolution.

Religious Minorities

Many Members of Congress follow the status of religious minorities in Turkey. Adherents of non-Muslim religions and minority Muslim sects (most prominently, the Alevis) rely to some extent on legal appeals, political advocacy, and support from Western countries to protect their rights in Turkey.

The Turkish government controls or closely oversees religious activities in the country. The Turkish arrangement (often referred to as "laicism") was originally used to enforce secularismReligious minorities are generally concentrated in Istanbul and other urban areas, as well as the southeast, and collectively represent around 0.2% of Turkey’s population. Adherents of non-Muslim

38 As prime minister, Erdogan had led past efforts to resolve the Kurdish question by using political, cultural, and economic development approaches, in addition to the traditional security-based approach, in line with the AKP’s ideological starting point that common Islamic ties among Turks and Kurds could transcend ethnic differences.

39 International Crisis Group, “Turkey’s PKK Conflict: The Rising Toll.” 40 Mark Landler and Carlotta Gall, “As Turkey Attacks Kurds in Syria, U.S. Is on the Sideline,” New York Times, January 22, 2018.

41 See https://hdp-usa.com/political-prisoners.

Congressional Research Service

12

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

religions and minority Muslim sects (most prominently, the Alevis) often attract, and to some extent rely on, legal appeals, political advocacy, and support from Western countries.

The Turkish government controls or closely oversees religious activities in the country. This arrangement was originally used to enforce secularism (often referred to as “laicism”), partly to prevent religion from influencing state actors and institutions as it did under Ottoman rule. However, since at least 2015, observers have detected some movement by state religious authorities in the direction of the AKP's Islamic’s Islamist-friendly worldview.50

Christians and Jews

, and successive Department of State International Religious Freedom Reports indicate that the Turkish government limits the rights of religious minorities.42

U.S. concerns focus largely on the rights of Turkey'’s Christian and Jewish communities, which have sought greater freedom to choose leaders, train clergy, own property, and otherwise function independently of the Turkish government.51 According to the State Department's International Religious Freedom Report for 2017, "Members of the Jewish community continued to express concern about anti-Semitism and increased threats of violence throughout the country."52

43

Halki Seminary and Hagia Sophia

Some Members of Congress routinely express grievances through proposed congressional resolutions and letters on behalf of the Ecumenical (Greek Orthodox) Patriarchate of Constantinople, the spiritual center of Orthodox Christianity based in Istanbul.5344 The Patriarchate, along with various U.S. and European officials, continues to press for the reopening of its Halki Theological School,5445 which was closed after a 1971 ruling by Turkey’s Constitutional Court ruling prohibiting the operation of private institutions of higher education. After an April 2018 meeting with President Erdogan, Patriarch Bartholomew said that he was "optimistic" that the seminary would be opened in the fall.55

46 In February 2019, then-Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras made the first-ever visit by a Greek prime minister to the seminary. In the past, Erdogan has reportedly said that Halki’s reopening would depend on measures by Greece to accommodate its Muslim community.47

Turkey has converted some historic Christian churches from museums into mosques, most notably Istanbul’s landmark Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya in Turkish), a sixth-century Greek Orthodox cathedral that was converted to a mosque after the 1453 Ottoman conquest of Istanbul and then became a museum duringinto mosques, and may be considering additional conversions. A popular movement to convert Istanbul's landmark Hagia Sophia (which became a museum in the early years of the Turkish republic) into a mosque has gained strength in recent years. Bills to effect that conversion have been introduced in the Turkish parliament, but none have been enacted.56 In June 2016, the government permitted daily televised Quran readings from Hagia Sophia during Ramadan, prompting criticism from the Greek government,57 and calls from the State Department for Turkey to respect the site's "traditions and complex history."58 As part of a cultural event in March 2018, President Erdogan recited a prayer from the Quran at the Hagia Sophia.59

Alevis

Republic. A popular movement to convert the site back into a mosque gained strength in recent years, culminating in President Erdogan’s public support for such a move during the March 2019 local elections campaign.48 In July 2020, a

42 See also, e.g., Ceren Lord, Religious Politics in Turkey: From the Birth of the Republic to the AKP (Cambridge University Press), 2018.

43 Since 2009, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has given Turkey designations ranging from “country of particular concern” (highest concern) to “monitored.” As of the 2020 report, Turkey is recommended for the Department of State’s Special Watch List. For additional information on Turkey’s religious minorities, see the Department of State’s International Religious Freedom Report for 2019. 44 On December 13, 2011, for example, the House passed H.Res. 306—“Urging the Republic of Turkey to safeguard its Christian heritage and to return confiscated church properties”—by voice vote. In June 2014, the House Foreign Affairs Committee favorably reported the Turkey Christian Churches Accountability Act (H.R. 4347). The Turkish government does not acknowledge the “ecumenical” nature of the Patriarchate, but does not object to others’ reference to the Patriarchate’s ecumenicity. 45 The Patriarchate also presses for the Turkish government to lift the requirement that the Patriarch be a Turkish citizen, and for it to return previously confiscated properties.

46 In remarks accompanying the release of the 2018 religious freedom report, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said, “We urge the immediate reopening of the Halki Seminary.” Department of State, “Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo at the Release of the 2018 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom,” June 21, 2019.

47 Stelyo Berberakis, “Patriarch hopes to reopen seminary after talks with president,” Daily Sabah, May 11, 2018; “Turkey ready to open Halki Seminary in return for a mosque in Greece: report,” Hurriyet Daily News, May 8, 2015. 48 “Turkey’s Erdogan Says He Plans to Change Hagia Sophia’s Title from Museum to Mosque,” Reuters, March 29,

Congressional Research Service

13

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations

Turkish court invalidated the 1934 decree that created Hagia Sophia as a museum, and President Erdogan subsequently approved its conversion to a mosque and led the first prayers there. The move, also seen as a political overture to conservative Turkish nationalists, was criticized by Secretary of State Michael Pompeo, a number of Members of Congress, and the EU Foreign Affairs Council.

Alevis

About 10 to 20 million Turkish Muslims are Alevis (of whom about 20% are ethnic Kurds). The Alevi community has some relation to Shiism60 and may contain strands from pre-Islamic Anatolian and Christian traditions.6149 Alevism has been traditionally influenced by Sufi mysticism that emphasizes believers'’ individual spiritual paths, but it defies precise description owing to its lack of centralized leadership and reliance on secret oral traditions. Despite a decision by Turkey'multiple decisions by Turkey’s top appeals court in August 2015 that the state financially support cemevis (Alevi houses of worship), the government still does not do so.62

50

Alevis have long been among the strongest supporters of secularism in Turkey, which they reportedly see as a form of protection from the Sunni majority.6351 Arab Alawites in Syria and southern Turkey are a distinct Shia-related religious community.

U.S.-Turkey Relations: Questions about Ally Status

Numerous points of bilateral tension

Turkey’s Strategic Orientation and Military Involvement Numerous points of tension and Turkey’s military operations in various places have raised questions within the United States and Turkey about the two countries' alliance. In the context of concerns about Turkey's strategic orientation (see "Turkey's Strategic Orientation and Foreign Policy"), many Members of Congress are increasingly active in proposing legislation and exercising oversight on U.S.-Turkey matters that include arms sales and strategic cooperation, various criminal cases, and economic sanctions. For its part, Turkey may bristle because it feels like it is treated as a junior partner, and may seek greater foreign policy diversification through stronger relationships with more countries.64

U.S./NATO Cooperation with Turkey

Overview

Turkey's location near several global hotspots makes the continuing availability of its territory for the stationing and transport of arms, cargo, and personnel valuable for the United States and NATO. From Turkey's perspective, NATO's traditional value has been to mitigate its concerns about encroachment by neighbors. Turkey initially turned to the West largely as a reaction to aggressive post-World War II posturing by the Soviet Union. In addition to Incirlik air base (see textbox below), other key U.S./NATO sites include an early warning missile defense radar in eastern Turkey and a NATO ground forces command in Izmir (see Figure 4 below). Turkey also controls access to and from the Black Sea through its straits pursuant to the Montreux Convention of 1936.

Current tensions have fueled discussion from the U.S. perspective about the advisability of continued U.S./NATO use of Turkish bases. Reports in 2018 suggest that some Trump Administration officials have contemplated permanent reductions in the U.S. presence in Turkey.65 There are historical precedents for such changes. On a number of occasions, the United States has withdrawn military assets from Turkey or Turkey has restricted U.S. use of its territory or airspace. These include the following:

- 1962 - Cuban Missile Crisis. The United States withdrew its nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles following this crisis.

- 1975 - Cyprus. Turkey closed most U.S. defense and intelligence installations in Turkey during the U.S. arms embargo that Congress imposed in response to Turkey's military intervention in Cyprus.

- 2003 - Iraq. A Turkish parliamentary vote did not allow the United States to open a second front from Turkey in the Iraq war.

The July 2016 coup plotters apparently used Incirlik air base, causing temporary disruptions of some U.S. military operations. This raised questions about Turkey's stability and the safety and utility of Turkish territory for U.S. and NATO assets. As a result of these questions and U.S.-Turkey tensions, some observers have advocated exploring alternative basing arrangements in the region.66

The cost to the United States of finding a temporary or permanent replacement for Incirlik and other sites in Turkey would likely depend on a number of variables including the functionality and location of alternatives, the location of future U.S. military engagements, and the political and economic difficulty involved in moving or expanding U.S. military operations elsewhere. An August 2018 media report claimed that U.S. officials have been "quietly looking for alternatives to Incirlik, including in Romania and Jordan."67 Another August report cited a Department of Defense spokesperson as saying that the United States is not leaving Incirlik.68

Calculating the costs and benefits to the United States of a U.S./NATO presence in Turkey, and of potential changes in U.S./NATO posture, revolves to a significant extent around three questions:

- To what extent does strengthening Turkey relative to other regional actors serve U.S. interests?

- To what extent does the United States rely on the use of Turkish territory or airspace to secure and protect U.S. interests?

- To what extent does Turkey rely on U.S./NATO support, both in principle and in functional terms, for its security and regional influence?

|

Incirlik Air Base Turkey's Incirlik (pronounced een-jeer-leek) air base in the southern part of the country has long been the symbolic and logistical center of the U.S. military presence in Turkey. Since 1991, the base has been critical in supplying U.S. military missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. The United States's 39th Air Base Wing is based at Incirlik. Turkey opened its territory for anti-IS coalition surveillance flights in Syria and Iraq in 2014 and permitted airstrikes starting in 2015. U.S. drones (both unarmed and armed) have reportedly flown anti-IS missions. At one point, the number of U.S. forces at the base was reportedly around 2,500 (previously, the normal force deployment had been closer to 1,500), but a March 2018 article, citing U.S. officials, indicated that the U.S. military has sharply reduced combat operations at Incirlik owing to U.S.-Turkey tensions.69 Turkey's 10th Tanker Base Command (utilizing KC-135 tankers) is also based at Incirlik. Turkey maintains the right to cancel U.S. access to Incirlik with three days' notice. |

U.S. Arms Sales and Aid to Turkey

|

State Department FY2019 Aid Request for Turkey IMET: $3.1 million NADR: $600,000 Total: $3.7 million |

Turkey has historically been one of the largest recipients of U.S. arms (see more information in Appendix B), owing to its status as a NATO ally, its large military, and its strategic position. Presently, however, Turkey seeks to build up its domestic defense industry (including through technology-sharing and co-production arrangements with other countries) as much as possible, while minimizing "off-the-shelf" arms purchases from the United States and other countries.

Since 1948, the United States has provided Turkey with approximately $13.8 billion in overall military assistance (nearly $8.2 billion in grants and $5.6 billion in loans). Current annual military and security grant assistance, however, is limited to approximately $3-5 million annually in International Military Education and Training (IMET); and Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR) funds.

Possible S-400 Acquisition from Russia

In December 2017, Turkey and Russia reportedly signed a finance agreement for Turkey's purchase of the Russian-made S-400 surface-to-air defense system. Media reports indicate that the deal, if finalized, would be worth approximately $2.5 billion.70 Turkey's procurement agency anticipates initial delivery in July 2019, which is sooner than the first reports of the deal had indicated.71 (An expedited delivery could increase the purchase price.72) Alongside Turkey's pursuit of the S-400 deal to address short-term needs, Turkey also is exploring an arrangement to co-develop a long-range air defense system with the Franco-Italian Eurosam consortium by the mid-2020s.73