EPA’s Clean Power Plan for Existing Power Plants: Frequently Asked Questions

Changes from June 5, 2017 to September 22, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

EPA's Clean Power Plan for Existing Power Plants: Frequently Asked Questions

Contents

- Background

- Q: Why did EPA promulgate the Clean Power Plan?

- Q: How much progress has the United States made in reducing GHG emissions and meeting emission targets?

- Q: How much does the generation of electricity contribute to total U.S. GHG emissions?

- Q: What other steps has EPA taken to reduce GHG emissions?

- Statutory Authority

- Q: Under what authority did EPA promulgate the Clean Power Plan rule?

- Q: What does Section 111(d), the authority EPA cited for the Clean Power Plan, bar EPA from regulating?

- Q: When has EPA previously used its Section 111(d) authority?

- Q: How do the Clean Power Plan standards for existing power plants relate to EPA's GHG standards for new fossil-fueled power plants?

- Q: How does Section 111 define the term "standards of performance"?

- The Final Rule

- Q: By how much would the Clean Power Plan reduce CO2 emissions?

- Q: To whom does the Clean Power Plan directly apply?

- Q: What types of facilities are affected by the final rule?

- Q: How many EGUs and facilities are affected by the final rule?

- Q: Does the Clean Power Plan apply to all states and territories?

- Q: What is the deadline under the final rule for submitting state plans to EPA?

- Q: What are the different options available to states when preparing their state plans?

- Q: Can states join together and submit multi-state plans?

- Q: What are the national CO2 emission performance rates in the final rule?

- Q: How did EPA establish the national CO2 emission performance rates?

- Q: How did EPA calculate the state-specific emission rate targets?

- Q: What are the state-specific emission rate targets?

- Q: How did EPA calculate the state-specific mass-based targets?

- Q: What are the state-specific mass-based targets?

- Q: Does the Clean Power Plan apply to EGUs on Indian lands?

- Q: Would states and companies that have already reduced GHG emissions receive credit for doing so?

- Q: How does EPA's Clean Power Plan interact with existing GHG emission reduction programs in the states, namely the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and California's climate policies?

- Q: What role is there for "outside-the-fence" emission reductions?

- Q: How would new fossil-fuel-fired power plants and their resulting electricity generation and emissions factor into a state's emission rate or emission calculations?

- Q: What role does nuclear power play in the Clean Power Plan rule?

- Q: What role does energy efficiency play in the Clean Power Plan final rule?

- Q: What role does biomass play in the Clean Power Plan?

- Q: What is the Clean Energy Incentive Program?

- Q: How does the final Clean Power Plan differ from the proposed rule?

- Next Steps

- Q: What are the next steps in the Clean Power Plan's implementation?

- Q: What incentives are there for early compliance?

- Q: If the Clean Power Plan is upheld, what happens if a state fails to submit an adequate plan by the appropriate deadline?

- Q: What would the proposed FIP have required?

- Costs and Benefits of the Clean Power Plan

- Q: What role did cost play in EPA's choice of emission standards?

- Q: What were EPA's estimates of the costs of this rule?

- Q: What other estimates of the Clean Power Plan's cost are there?

- Q: What were the benefits EPA estimated for the Clean Power Plan?

- Potential Impacts on the Electricity Sector

- Q: How might the Clean Power Plan impact electricity prices and electricity bills?

- Q: How did the Clean Power Plan address electricity reliability?

- Q: What types of electricity sector infrastructure changes might result from the Clean Power Plan?

- Reconsidering the Rule

- Q. What is required by President Trump's Executive Order 13783?

- Q. What would the process for suspending, revising, or rescinding the Clean Power Plan be?

- The CPP and the International Paris Agreement

- Q: What would the CPP contribute to meeting the U.S. GHG mitigation pledge under the international Paris Agreement (PA)?

- Q: Can the United States meet its contribution under the Paris Agreement without the Clean Power Plan?

- Congressional Actions

- Q: Can Congress use the Congressional Review Act (CRA) to disapprove the rule?

- Q: What other steps might Congress take to replace, rescind, or modify the Clean Power Plan rule?

- Judicial Review

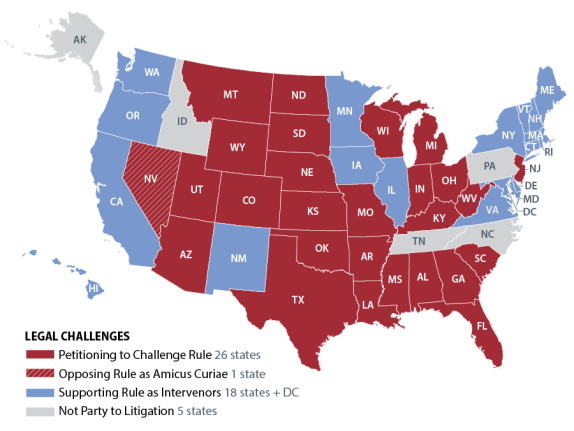

- Q: What parties have joined litigation over the final Clean Power Plan rule?

- Q: What is the status and time frame of litigation challenging the final Clean Power Plan rule, and will the rule remain in place while the litigation is pending?

- Q: What legal arguments are being made for and against the final Clean Power Plan rule?

- Q: Might other litigation affect the final Clean Power Plan rule?

- For Further Information

- Q: Who are the CRS contacts for questions regarding this rule?

Figures

- Figure 1. U.S. GHG Emissions (Net)

- Figure 2. Percentage Change in U.S. GHG Emissions, the Economy, and Population

- Figure 3. CO2 Emissions from the Electricity Sector

- Figure 4.

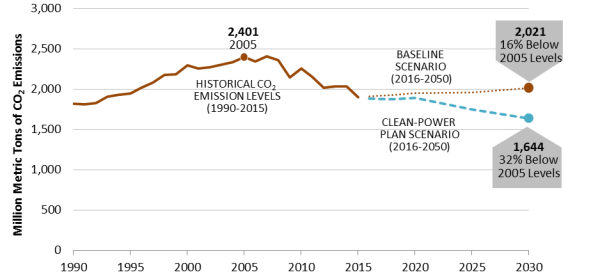

U.S. CO2 Emissions from Electricity GenerationHistorical Emissions and EPA Baseline and Clean Power Plan Projections

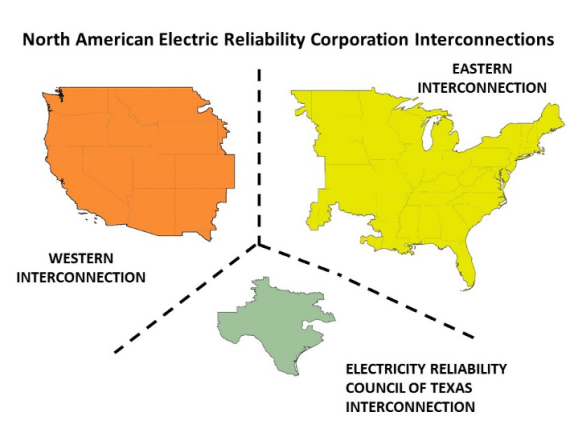

- Figure 5. Electricity Regions in EPA's Methodology

- Figure 6. EIA Projections of All Energy-Related CO2 Emissions Under Various Assumptions

- Figure 7. States Participating in Clean Power Plan Litigation

Tables

- Table 1. National CO2 Performance Rates

- Table 2. State-Specific Emission Rate Baselines (2012), Emission Rate Targets (2030), and Percentage Reductions Compared to Baselines

- Table 3. State-Specific 2012 CO2 Emission Baselines and 2030 CO2 Emission Targets

- Table 4. Emission Rate and Emission Targets for Areas of Indian Country

Summary

On March 28, 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13783, directing federal agencies to review existing regulations and policies that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources. Among its specific provisions, the order directed the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to review the Clean Power Plan, one of the Obama Administration's most important actions directed at reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The Clean Power Plan was promulgated in August 2015 to reduce GHG emissions from the generation of electric power. Fossil-fueled electric power plants are the largest U.S. source of such emissions, accounting for about 29% of the U.S. total from all sources. The rule sets individual state targets for average emissions from existing power plants—interim targets for the period 2022-2029 and final targets to be met by 2030. The targets for each state were derived from a formula based on three "building blocks"—efficiency improvements at individual coal-fired power plants and increased use of renewable power and natural- gas- combined-cycle power plants to replace more polluting coal-fired units. Although EPA set state-specific targets, states would determine how to reach these goals, not EPA. Each state can reach its goal however it chooses, without needing to "comply" with the assumptions in the EPA building blocks.

When the rule is fully implemented, EPA has said it would expect the rule's targets to reduce total power plant GHG emissions by about 32% in 2030 as compared with 2005 levels. A variety of factors—some economic, some the effect of government policies at all levels—have already reduced power sector GHG emissions about 2/3 of this amount as of 2015.

Whether the Clean Power Plan will be implemented as promulgated is uncertain, in part because of the executive order's directive to review and potentially revise or rescind it. The executive order directs EPA to review the CPP for consistency with several broad policies stated in section 1 of the order and, if appropriate, to publish for notice and comment proposed rules suspending, revising, or rescinding the rule.

Adding to questions about implementation, the rule is the subject of ongoing litigation in which a number of states and other entities have challenged it (while other states and entities have intervened in support of it). On February 9, 2016, the Supreme Court stayed implementation of the rule for the duration of the litigation. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia heard oral arguments in the case in September 2016, but agreed on April 28, 2017 to an EPA request to hold the case in abeyance for 60 days while the agency conducts the review required by the executive order. The court ordered the parties to submit briefs by May 15 on whether the court should remand the Clean Power Plan to EPA rather than hold it in abeyance.

This report provides background information and discusses the statutory authority under which EPA promulgated the rule. The Clean Power Plan relies on authority asserted by EPA in Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA). This section has been infrequently used and seldom interpreted by the courts, so a number of questions have arisen regarding the extent of EPA's authority and the mechanisms of implementation.

The report also summarizes the provisions of the Clean Power Plan rule as it was finalized on August 3, 2015, including

- how large an emission reduction would be achieved under the rule nationwide,

- how EPA allocated emission reduction requirements among the states,

- the potential role of cap-and-trade systems and other flexibilities in implementation,

- what role the actions of individual power plants (i.e., "inside the fence" actions) and actions by other actors, including energy consumers ("outside the fence" actions) might play in compliance strategies, and

- what role there would be for existing programs at the state and regional level, such as the nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), and for broader GHG reduction programs such as those implemented in California.

The report also discusses options that Congress has to influence EPA's action.

On August 3, 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) promulgated standards for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from existing fossil-fuel-fired power plants under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA).1 The rule, known as the Clean Power Plan (CPP), appeared in the Federal Register on October 23, 2015.2 Information regarding the rule and its current status are posted on EPA's website.3, including EPA's Regulatory Impact Analysis and numerous EPA Fact Sheets, can be found at https://web.archive.org/web/20161104002205/http://www2.epa.gov/cleanpowerplan/clean-power-plan-existing-power-plants.

The agency conducted significant outreach to interested parties both before and after the rule's proposal. Before proposal, according to Bloomberg BNA, "Senior Environmental Protection Agency officials consulted with at least 210 separate groups representing a broad range of interests in the Washington, DC, area and held more than 100 meetings and events with additional organizations across regional offices."43 Despite, or perhaps because of, these outreach efforts, EPA received more than 4.3 million public comments following the rule's proposal, the most ever for an EPA rule.54 The agency continued outreach activities during the public comment period and before publication of the final rule.

Interest in the rule reflects what is generally conceded to be the importance of its potential effects. The economy and the health, safety, and well-being of the nation depend on a reliable and affordable power supply, which many contend would be adversely affected by controls on GHG emissions from power plants. At the same time, an overwhelming scientific consensus has formed around the risks, potentially catastrophic, of greenhouse gas-induced climate change. To determine how the rule addresses these issues, congressional committees asked EPA officials numerous questions about the rule, and individual Members wrote EPA seeking additional information about the rule's potential impacts.65 This congressional interest has continued since the final rule was promulgated. EPA responded to questions and comments by making numerous changes to the rule between proposal and promulgation.

The rule is the subject of ongoing litigation: a number of states and other entities have challenged the rule, while other states and entities have intervened in support of it. On February 9, 2016, the Supreme Court granted applications to stay the rule for the duration of the litigation. While EPA cannot currently enforce the rule—because the litigation has not yet been resolved—the contents and parameters of the rule as promulgated remain important: Some states are not engaged in compliance planning in light of the stay, while other states have expressed their intention to proceed with planning.76 In addition, on March 28, 2017, President Trump signed Executive Order 13783, directing federal agencies to review existing regulations and policies that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources. Among its specific provisions, the order directed EPA to review the Clean Power Plan and three proposed and final rules related to it "for consistency with the policy set forth in ...this order," and, if appropriate, to "suspend, revise, or rescind" them. Thus, the status of the Clean Power Plan is in flux, with major decisions possible from both the executive and judicial branches.

In order to provide basic information about the rule as promulgated, and about the ongoing litigation and reconsideration of the rule, this report presents a series of questions and answers.

Background

Q: Why did EPA promulgate the Clean Power Plan?

A: EPA promulgated emissions guidelines to limit carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from existing power plants under Section 111(d) of the CAA for a variety of reasons. Some important context includes the following:

- The Supreme Court in Massachusetts v. EPA in 2007 determined that "air pollutant," as used in the CAA, covers GHGs.

87 EPA thereafter determined that GHGs are air pollutants that were "reasonably anticipated to endanger both public health and welfare."98

- In December 2010, EPA entered into a settlement agreement to issue New Source Performance Standards (NSPSs) for GHG emissions from electric generating units (EGUs) under Section 111(b) of the CAA and emission guidelines under Section 111(d) covering existing EGUs.

109 As discussed further below,1110 EPA finalized NSPSs for GHG emissions from new, modified, and reconstructed fossil-fuel-fired EGUs at the same time as the CPP.1211

- In the context of U.S. commitments under a 1992 international treaty, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), President Obama pledged in 2009 to reduce U.S. GHG emissions by 17% below 2005 levels by 2020, consistent with an 80% reduction by 2050.

1312 The President set a further goal as the U.S. national contribution to global GHG reductions under the 2015 Paris Agreement: a 26% to 28% reduction from 2005 levels to be achieved by 2025, consistent with a straight-line path to an 80% reduction by 2050.1413 Other countries have also pledged GHG emissions abatement.1514 Parties to the Paris Agreement (currently 143) are legally bound to submit GHG emission reduction pledges, although they are not bound to the quantitative targets themselves. As of April 27, 2017, 165 intended nationally determined contributions—covering more than 190 countries, including all major emitters—had been submitted. The PA entered into force on November 4, 2016, and the United States is a Party, following President Obama's communication of U.S. acceptance of the agreement in September 2016. The U.S. Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is registered in the interim Registry of NDCs.

Fossil-fueled EGUs account for 29% of U.S. GHG emissions. It would be challenging to substantially abate U.S. GHG emissions without addressing these sources.

Q: How much progress has the United States made in reducing GHG emissions and meeting emission targets?

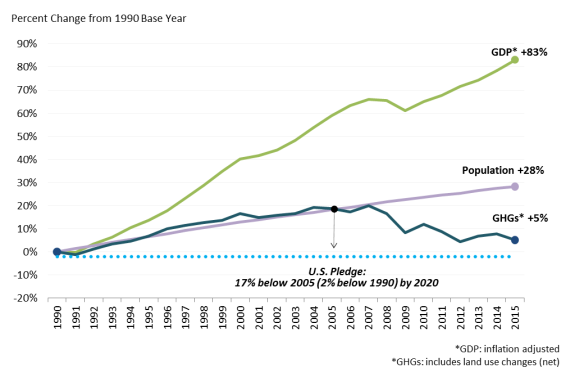

A: Figure 1 illustrates net U.S. GHG emissions between 1990 and 2015.1615 As the figure indicates, U.S. GHG emissions increased during most of the years between 1990 and 2007. GHG emissions decreased substantially in 2008 and 2009 as a result of a variety of factors—some economic, some the effect of government policies at all levels. Since 2010, emissions have fluctuated but have not surpassed 2009 levels.

The figure also compares recent U.S. GHG emission levels to the 2020 and 2025 emission goals. Based on 2015 GHG emission levels, the United States is more than halfway to reaching the AdministrationPresident Obama's 2020 goal (17% below 2005 levels). U.S. GHG levels in 2015 were 11% below 2005 levels.

|

Figure 1. U.S. GHG Emissions (Net) Compared to 2020 and 2025 Emission Targets |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS; data from EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2015, April 2017, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/inventory-us-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks. Notes: Net GHG emissions includes net carbon sequestration from land use, land use change, and forestry. This involves carbon removals from the atmosphere by photosynthesis and storage in vegetation. |

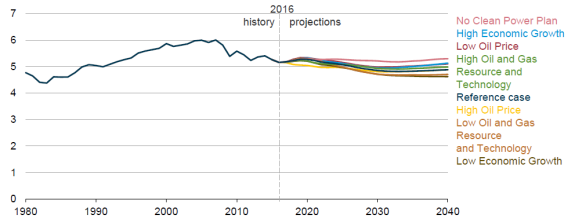

Figure 2 illustrates the percentage change in net U.S. GHG emissions, U.S. economic activity measured as gross domestic product (GDP, adjusted for inflation), and U.S. population between 1990 and 2015. As Figure 2 indicates, during that period, U.S. economic activity increased by 83%, population increased 28%, and GHG emissions increased by 5%.

Q: How much does the generation of electricity contribute to total U.S. GHG emissions?

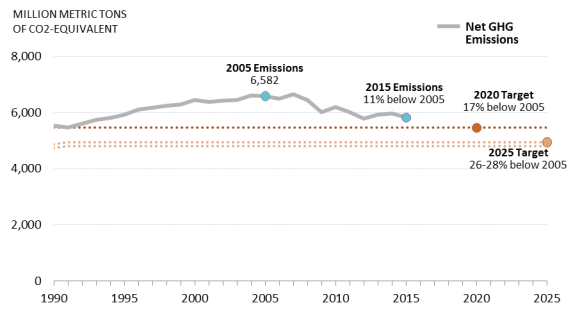

A: The U.S. electricity generation sector1716 contributes the largest percentage of U.S. GHG emissions, accounting for about 29% of all U.S. GHG emissions in 2015.1817 CO2 emissions account for the vast majority (99% in 2015) of GHG emissions from the electricity sector. As illustrated in Figure 3, CO2 emissions from electricity generation generally increased between 1990 and 2007, but have generally decreased since that time.19

|

Figure 3. CO2 Emissions from the Electricity Sector 1990-2015 |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS, data from EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2015, April 2017. |

Q: What other steps has EPA taken to reduce GHG emissions?

A: Prior to the promulgation of this rule, EPA had already promulgated GHG emission standards for light-duty and medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, using its authority under Section 202 of the CAA.2019 Light-duty vehicles (cars, SUVs, vans, and pickup trucks) and medium- and heavy-duty vehicles (including buses, heavy trucks of all kinds, and on-road work vehicles) are collectively the largest emitters of GHGs other than power plants. Together, on-road motor vehicles accounted for 23% of U.S. GHG emissions in 2015.2120

GHG standards for light-duty vehicles first took effect for Model Year (MY) 2012. Allowable GHG emissions will be gradually reduced each year from MY2012 through MY2025. In MY2025, emissions from new vehicles must average about 50% less per mile than in MY2010. The standards for heavier-duty vehicles began to take effect in MY2014. They will require emission reductions of 6% to 23%, depending on the type of engine and vehicle, when fully implemented in MY2018. A second round of standards, to address later medium- and heavy-duty vehicles, was promulgated on August 16, 2016.2221 The new standards cover model years 2018-2027 for certain trailers, and model years 2021-2027 for semi-trucks, large pickup trucks, vans, and all types and sizes of buses and work trucks. The standards are expected to lower CO2 emissions by approximately 1.1 billion metric tons over the life of the covered vehicles, according to EPA.

EPA determined that the promulgation of standards for motor vehicles also triggered Clean Air Act requirements that new major stationary sources of emissions (power plants, refineries, etc.) obtain permits for their GHG emissions, and install the Best Available Control Technology, as determined by state and EPA permit authorities on a case-by-case basis, prior to construction. The Supreme Court partially upheld that position in June 2014, provided that the sources were already required to obtain permits for other conventional pollutants.2322

The GHG permitting requirements for stationary sources have been in place since 2011 but were limited by EPA's "Tailoring Rule" to the very largest emitters—about 200 facilities as of mid-2014. The Supreme Court's June 2014 decision invalidated the Tailoring Rule, but found that EPA could limit GHG permit requirements to "major" facilities, so-classified as a result of their emissions of conventional pollutants. In so doing, the Court limited the pool of potential GHG permittees to a number similar to what the Tailoring Rule would have provided.

In 2016, EPA also promulgated GHG (methane) emission standards for new oil and gas sources2423 and for new and existing municipal solid waste (MSW) landfills.2524 Although these rules have been promulgated, they are being challenged in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.2625 President Trump's Executive Order 13783 requires EPA to review the methane emission standards for oil and gas sources.2726In addition, EPA announced that it will reconsider fugitive emissions monitoring requirements that are part of the methane standards and stay the compliance date for those requirements for 90 days.28

Statutory Authority

Q: Under what authority did EPA promulgate the Clean Power Plan rule?

A: EPA cited Section 111(d) of the CAA2928 for its authority to promulgate the CPP.3029 Section 111(d) requires EPA, among other things, to issue regulations providing for states to submit plans to EPA to impose "standards of performance" for existing stationary sources for any air pollutant that meets certain criteria. The first criterion is that the air pollutant must not already be regulated under certain other CAA provisions,3130 which are discussed further below. The second criterion is that CAA Section 111(b) NSPSs apply to the source category for the air pollutant.3231 EPA finalized Section 111(b) NSPSs for new, modified, or reconstructed power plants for CO2 when it issued the CPP rule.3332 EPA often refers to Section 111(d) regulations as "emission guidelines."3433

Q: What does Section 111(d), the authority EPA cited for the Clean Power Plan, bar EPA from regulating?

A: CAA Section 111(d) bars EPA from regulating an air pollutant pursuant to Section 111(d) if the air pollutant is already regulated as a criteria pollutant under a National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) under CAA Section 108 or, per EPA's interpretation, as a hazardous air pollutant (HAP) under CAA Section 112.3534 CO2 is not regulated as a criteria pollutant or a HAP under either of these provisions.

Because the House and Senate passed different versions of CAA Section 111(d) in the 1990 CAA amendments, controversy exists over EPA's authority per the Section 112 criterion.3635 Under the House's provision, CAA Section 111(d)(1)(A)(i) requires EPA to issue a rule under which each state shall submit to EPA a plan adopting standards of performance for any air pollutant that "is not included on a list published under section 108(a) or emitted from a source category which is regulated under section 112.... "3736 Because EPA regulates power plants under Section 112 for HAP,3837 some have argued that EPA is barred from regulating power plants under Section 111(d) for CO2, although CO2 is not regulated as a HAP under Section 112.3938

In the final CPP rule, EPA addressed this issue, finding the CAA Section 112 exclusion to "not bar the regulation under CAA section 111(d) of non-HAP from a source category, regardless of whether that source category is subject to standards for HAP under CAA section 112."4039 Describing the House amendment as ambiguous,4140 EPA stated that the "sole reasonable" interpretation is that "the phrase 'regulated under section 112' refers only to the regulation of HAP emissions. In other words, EPA's interpretation concluded that source categories 'regulated under section 112' are not regulated by CAA section 112 with respect to all pollutants, but only with respect to HAP."4241

In making this argument, EPA also cited the Senate's 1990 amendment to CAA Section 111(d)(1)(A)(i), which is published in the U.S. Statutes at Large but not in the U.S. Code.4342 The Senate's amendment excludes from Section 111(d) regulation any air pollutant "included on a list published under section 108(a) or 112.... "43"44 As such, the Senate language excludes air pollutants regulated under Section 112, rather than source categories, from Section 111(d) regulation, which is consistent with EPA regulating power plants for CO2 under Section 111(d).

Q: When has EPA previously used its Section 111(d) authority?

A: An analysis by the American College of Environmental Lawyers observed that since the 1970s, EPA has promulgated emission guidelines under Section 111(d) of the CAA on seven occasions.4544

EPA's 2005 Clean Air Mercury Rule (CAMR) delisted coal-fired electric utility steam generating units from Section 112 of the CAA and, instead, established a cap-and-trade system for mercury under Section 111(d);4645 however, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit vacated CAMR in 2008.4746 The court found that EPA's delisting of the source category from Section 112 was unlawful and that EPA was obligated to promulgate standards for mercury and other hazardous air pollutants under Section 112.4847 The court, therefore, did not reach the question of whether the flexible approach taken by EPA for mercury controls (i.e., a cap-and-trade system) met the requirements of Section 111(d).

In 1996, EPA used its Section 111(d) authority to regulate emissions of methane and non-methane organic compounds from large landfills.4948 These regulations set numeric emission limits and required designated landfills to use certain types of control equipment.5049 In August 2016, EPA revised emission guidelines for existing landfills operating prior to July 17, 2014.51

EPA also used its Section 111(d) authority for another emission guideline rule for large municipal waste combustors, which EPA proposed in 1989 and finalized in 1991 pursuant to a consent decree.5251 However, the 1990 CAA amendments added a new CAA Section 129 specifically to address emissions from solid waste incinerators, including municipal waste combustors. Section 129 required Section 111 NSPS and emission guidelines for solid waste incinerators to meet certain requirements,5352 so the 1991 rule for large municipal waste combustors was superseded by a later rule intended to comply with Section 129.5453 EPA adopted the remaining Section 111(d) emission guidelines for acid mist from sulfuric acid production units,5554 fluoride emissions from phosphate fertilizer plants,5655 total reduced sulfur emissions from kraft pulp mills,5756 and fluoride emissions from primary aluminum plants.5857 Additionally, EPA has promulgated six rules that implement Section 111(d) in conjunction with the requirements of CAA Section 129.5958

Q: How do the Clean Power Plan standards for existing power plants relate to EPA's GHG standards for new fossil-fueled power plants?

A: EPA finalized standards for new fossil-fuel-fired power plants under Section 111(b) of the CAA on the same day it finalized the CPP rule.6059 As discussed earlier, when EPA sets NSPSs for a source category for an air pollutant under Section 111(b), EPA triggers Section 111(d)'s applicability for existing sources in the Section 111(b) regulated source category for the air pollutant if the air pollutant is neither regulated as a criteria pollutant under a NAAQS nor, according to EPA's interpretation, regulated as a HAP for the source category.6160 Consequently, EPA's adoption of NSPSs for new fossil-fueled power plants for CO2 triggered Section 111(d)'s applicability for existing fossil-fueled power plants for CO2.

Conversely, EPA has no authority to set Section 111(d) performance standards for existing sources in a source category for an air pollutant if EPA has no NSPSs for new sources in the source category for the air pollutant. Many of the petitioners challenging the CPP rule for existing power plants are also challenging EPA's NSPSs for new, modified, or reconstructed power plants for CO2.6261 Because the CPP rule is predicated on the NSPS rule, a court decision striking down the NSPS rule would undermine the CPP rule's legal basis.

Q: How does Section 111 define the term "standards of performance"?

A: The term "standards of performance" appears repeatedly in CAA Section 111, including in both the Section 111(b) provisions relating to new sources and the Section 111(d) provisions relating to existing sources in a source category. Section 111(a) defines "standard of performance" as

[A] standard for emissions of air pollutants which reflects the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction which (taking into account the cost of achieving such reduction and any nonair quality health and environmental impact and energy requirements) the Administrator determines has been adequately demonstrated.63

Under this definition, EPA must determine the "best system of emission reduction" (BSER) that is "adequately demonstrated," considering certain factors. Then, EPA or states, as applicable, must base the standard for emissions on the degree of emission limitation that is "achievable" through the BSER. The CAA does not define these component terms within the definition of "standard of performance."

As discussed in more detail below,6463 in the CPP rule, EPA determined the BSER for existing power plants based on three "building blocks": (1) efficiency improvements at affected coal-fired power plants, (2) generation shifts among affected power plants, and (3) renewable generating capacity.6564 It then used the BSER to set CO2 emission performance rates.6665 EPA used a different approach to determine the BSER for new, modified, and reconstructed power plants.67

Courts have expanded on the CAA Section 111 definition of the term "standards of performance" and EPA's interpretation of its component terms, but they have done so generally with respect to NSPSs under Section 111(b) rather than emission guidelines for existing sources under Section 111(d).6867 As discussed further below,6968 EPA explains that the interpretation of the term "standards of performance" and related terms is guided by Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984), in which the U.S. Supreme Court stated that if a statute "is silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency's answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute."7069 However, some opponents of the CPP rule argue that this framework, known as "Chevron deference," should not apply, at least to certain aspects of EPA's interpretation of CAA Section 111.71

The Final Rule

Q: By how much would the Clean Power Plan reduce CO2 emissions?

A: EPA's final rule does not set a future level of CO2 emissions from existing electricity generators. The rule establishes uniform national CO2 emission7271 performance rates—measured in pounds of CO2 per megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity generation—and state-specific CO2 emission rate and emission targets. States determine which measure they want to use to be in compliance.

Although it has been widely reported that the rule would require a 32% reduction in CO2 emissions from the electricity sector by 2030, compared to 2005 levels, this reduction was EPA's estimate of the rule's ultimate effect nationwide. The final rule does not explicitly require this level of emission reduction from electric generating facilities or states.

EPA used computer models to project these CO2 emission levels. The actual emissions would depend on how states choose to comply with the rule and how much electricity is generated (and at what type of generation units).

Figure 4 compares EPA's projections of CO2 emissions in the electricity sector resulting from the final rule with historical CO2 emissions (1990-2015) from the electricity sector. The figure also illustrates the projected CO2 emissions from the electricity sector under EPA's baseline scenario (i.e., business-as-usual). The figure indicates that the final rule would reduce CO2 emissions in the electricity sector by 32% in 2030 compared to 2005 levels. Under the baseline scenario (without the rule), EPA projected a 16% reduction by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

Figure 4. Historical Emissions |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS; historical emissions from EPA, Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2015, April 2017; baseline and CPP projections from EPA, Power Sector Modeling, http://www.epa.gov/airmarkets/programs/ipm/cleanpowerplan.html. Notes: CRS converted EPA's projected emissions from short tons to metric tons. |

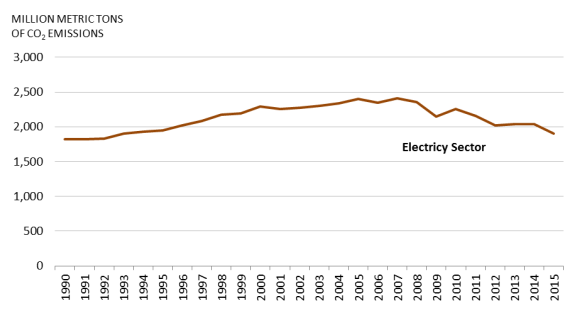

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) provided comparable results in its 2017 Annual Energy Outlook.7372 EIA estimated that under a reference case scenario, which includes the CPP and other assumptions, CO2 emissions in the electricity sector would decrease by 36% in 2030 compared to 2005 levels. Under a scenario without the CPP, EIA estimated that CO2 emissions in the electricity sector would decrease by 22% in 2030 compared to 2005 levels.

Q: To whom does the Clean Power Plan directly apply?

A: The final rule directs governors (or their designees) to submit state-specific plans to EPA that describe how the states would meet their compliance obligations established by the final rule.

Q: What types of facilities are affected by the final rule?

A: The final rule addresses CO2 emissions at "affected" electric generating units (EGUs). In general, an affected EGU is a fossil-fuel-fired unit that was in operation or had commenced construction as of January 8, 2014, has a generating capacity above a certain minimum threshold, and sells a certain amount of its electricity generation to the grid.7473 The state-specific plans describe the requirements that would apply to affected EGUs.

Q: How many EGUs and facilities are affected by the final rule?

A: Based on data EPA provided in support of its final rule,7574 the affected EGU definition applied to approximately 3,000 EGUs at approximately 1,100 facilities. The number of EGUs and facilities varies by state.

Q: Does the Clean Power Plan apply to all states and territories?

A: EPA did not establish emission rate goals for Vermont and the District of Columbia, because they did not have affected EGUs. Although Alaska and Hawaii had targets in EPA's proposed rule, in its final rule, EPA stated that Alaska, Hawaii, and the two U.S. territories with affected EGUs (Guam and Puerto Rico) would not be required to submit state plans on the schedule required by the final rule, because EPA "does not possess all of the information or analytical tools needed to quantify" the best system of emission reduction for these areas. In the final rule preamble, EPA stated it would "determine how to address the requirements of section 111(d) with respect to these jurisdictions at a later time."76

Q: What is the deadline under the final rule for submitting state plans to EPA?

A: Under the final rule as promulgated, states were required to submit to EPA either an initial plan or final plan by September 6, 2016. If a state submitted an initial plan, the state could seek an extension from EPA to submit its final plan by September 6, 2018. If EPA granted this extension, the state would have been required to submit a progress report by September 6, 2017. Because the rule is currently stayed for the duration of the litigation, and the litigation is likely to continue into 2017 or potentially later,77 these deadlines do not have legal effect and will likely be delayed if the rule is ultimately upheld.

Q: What are the different options available to states when preparing their state plans?

A: States have several key decisions to make when crafting their state plans. Perhaps the most important decision is whether to measure compliance with an emission rate target (pounds of CO2 per MWh) or a mass-based target (tons of CO2). EPA provided both targets in its final rule. If a state decides to set up an emission (or emission rate) trading system, the trading system would be compatible only with systems using the same metric. In other words, a rate-based state cannot trade with a mass-based state.

In addition, the final rule allows for two types of state plans, described by EPA as (1) an "emission standards" approach and (2) a "state measures" approach. With an emission standards approach, a state would implement national CO2 emission performance rates (discussed below) directly at the affected EGUs in the state. In contrast, a state measures approach would allow a state to achieve the equivalent of the national CO2 emission performance rates by using some combination of federally enforceable standards and elements that would be enforceable only under state laws (e.g., renewable energy and/or energy efficiency requirements).

Q: Can states join together and submit multi-state plans?

A: States have the option of submitting multi-state plans. The same deadlines apply to multi-state plans. A multi-state plan would employ either a rate-based or mass-based approach.

Q: What are the national CO2 emission performance rates in the final rule?

A: The final rule establishes uniform national CO2 emission performance rates—measured in pounds of CO2 per MWh of electricity generation—for each of the two subcategories of EGUs affected by the rule (Table 1). These subcategories include (1) fossil-fuel-fired electric steam generating units, of which coal generation accounts for 94%—oil and natural gas contribute the remainder—and (2) stationary combustion turbines, namely natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) units.

The national rates are a major change from the proposed rule, which did not include similar performance rates at the EGU level. As discussed below, the national CO2 emission performance rates are the underpinnings for the calculations that EPA used to develop state-specific emission rates and mass-based targets.

|

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

2030 |

Interim (Average of 2022-2030) |

Final (2030) |

|

|

Fossil steam units |

1,741 |

1,681 |

1,592 |

1,546 |

1,500 |

1,453 |

1,404 |

1,355 |

1,304 |

1,534 |

1,305 |

|

NGCC units |

898 |

877 |

855 |

836 |

817 |

798 |

789 |

779 |

770 |

832 |

771 |

Source: Prepared by CRS; annual rates from EPA, CO2 Emission Performance Rate and Goal Computation Technical Support Document for CPP Final Rule, August 2015.

Note: To generate the final rates, EPA used the 2030 rates and rounded up to the next integer.

Q: How did EPA establish the national CO2 emission performance rates?

A: EPA compiled 2012 CO2 emissions and electricity generation data from each affected EGU in each state. Then EPA divided the states into three regions (see Figure 5), aggregating the CO2 emission and electricity generation data. Next, EPA applied three "building blocks" to the aggregated regional data:

- Building block 1: EPA applied heat rate improvements to coal-fired EGUs, improving their overall emission rate. The improvements vary by region from 2.1% to 4.3%.

- Building block 2: EPA assumed that NGCC generation would increase to a specific ceiling, displacing an equal amount of generation from steam units (primarily coal). Note that in the final rule, EPA applies building block 3 before building block 2, dampening the impact of building block 2.

- Building block 3: EPA projected annual increases in renewable energy generation, which resulted in corresponding decreases in generation from affected EGUs. EPA based the future increases on renewable energy generation increases between 2010 and 2014.

EPA's building block application produced annual CO2 emission performance rates for steam and NGCC units in each region. EPA compared the rates in each of the three regions and chose the least stringent regional rate as the national standard for that particular year for each EGU category (Table 1).

|

|

Source: Reproduced from EPA, Overview of the Clean Power Plan: Cutting Carbon Pollution from Power Plants, August 2015, http://www.epa.gov/airquality/cpp/fs-cpp-overview.pdf. Notes: EPA did not establish emission rate goals for Vermont and the District of Columbia because they do not currently have affected EGUs. Although Alaska and Hawaii have targets in the proposed rule, in its final rule, EPA stated that Alaska, Hawaii, and the two U.S. territories with affected EGUs (Guam and Puerto Rico) will not be required to submit state plans on the schedule required by the final rule, because EPA "does not possess all of the information or analytical tools needed to quantify" the best system of emission reduction for these areas. EPA stated it will "determine how to address the requirements of section 111(d) with respect to these jurisdictions at a later time" (EPA, "Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units," Final Rule, 80 Federal Register 64743, October 23, 2015). |

Q: How did EPA calculate the state-specific emission rate targets?

A: To generate state-specific emission rate targets, EPA applied the national CO2 emission performance rates to each state's baseline (2012) of fossil fuel generation (steam generation vs. NGCC generation).

For example, in 2012, Arizona's electricity generation mix included

- 49% steam generation, and

- 51% NGCC generation.

To calculate Arizona's 2030 emission rate target, EPA multiplied the percentage of each generation type by the corresponding 2030 national CO2 emission performance rate (Table 1):

(49% X 1,305 lbs. CO2/MWh) + (51% X 771 lbs. CO2/MWh) = 1,031 lbs. CO2/MWh

Q: What are the state-specific emission rate targets?

A: Table 2 lists the 2030 emission rate targets for each state and the 2012 emission rate baselines. In addition, the table lists the implied percentage reductions required to achieve the 2030 emission rate targets compared to the 2012 baselines.

EPA used different formulas to calculate the 2012 baselines in the proposed and final rules. The final rule baseline includes pounds of CO2 generated from affected EGUs in each state (the numerator) divided by the electricity generated from these units. The proposed rule baseline included pounds of CO2 generated from affected EGUs in each state (the numerator) divided by the electricity generated from these units and "at-risk" nuclear power and renewable energy generation (the denominator). Including these additional elements in the denominator often yielded lower baselines compared to the final rule.

Therefore, it is problematic to compare the percentage rate reductions from the proposed rule with the final rule, because the 2012 baseline calculations changed—sometimes dramatically—in the final rule. For example, Washington's 2012 baseline was 756 lbs. CO2/MWh in the proposed rule. In the final rule, Washington's 2012 baseline increased by 107% to 1,556 lbs. CO2/MWh.

Table 2. State-Specific Emission Rate Baselines (2012), Emission Rate Targets (2030), and Percentage Reductions Compared to Baselines

|

State |

2012 Emission Rate Baseline |

2030 Emission Rate Target |

Percentage Change Compared to Baseline |

|

Pounds of CO2 per megawatt-hour of electricity generation |

|||

|

Alabama |

1,518 |

1,018 |

33% |

|

Alaska |

Not established |

Not established |

NA |

|

Arizona |

1,552 |

1,031 |

34% |

|

Arkansas |

1,816 |

1,130 |

38% |

|

California |

954 |

828 |

13% |

|

Colorado |

1,904 |

1,174 |

38% |

|

Connecticut |

846 |

786 |

7% |

|

Delaware |

1,209 |

916 |

24% |

|

Florida |

1,221 |

919 |

25% |

|

Georgia |

1,597 |

1,049 |

34% |

|

Hawaii |

Not established |

Not established |

NA |

|

Idaho |

834 |

771 |

8% |

|

Illinois |

2,149 |

1,245 |

42% |

|

Indiana |

2,025 |

1,242 |

39% |

|

Iowa |

2,195 |

1,283 |

42% |

|

Kansas |

2,288 |

1,293 |

43% |

|

Kentucky |

2,122 |

1,286 |

39% |

|

Louisiana |

1,577 |

1,121 |

29% |

|

Maine |

873 |

779 |

11% |

|

Maryland |

2,031 |

1,287 |

37% |

|

Massachusetts |

1,003 |

824 |

18% |

|

Michigan |

1,928 |

1,169 |

39% |

|

Minnesota |

2,082 |

1,213 |

42% |

|

Mississippi |

1,151 |

945 |

18% |

|

Missouri |

2,008 |

1,272 |

37% |

|

Montana |

2,481 |

1,305 |

47% |

|

Nebraska |

2,161 |

1,296 |

40% |

|

Nevada |

1,102 |

855 |

22% |

|

New Hampshire |

1,119 |

858 |

23% |

|

New Jersey |

1,058 |

812 |

23% |

|

New Mexico |

1,798 |

1,146 |

36% |

|

New York |

1,140 |

918 |

19% |

|

North Carolina |

1,673 |

1,136 |

32% |

|

North Dakota |

2,368 |

1,305 |

45% |

|

Ohio |

1,855 |

1,190 |

36% |

|

Oklahoma |

1,565 |

1,068 |

32% |

|

Oregon |

1,089 |

871 |

20% |

|

Pennsylvania |

1,642 |

1,095 |

33% |

|

Rhode Island |

918 |

771 |

16% |

|

South Carolina |

1,791 |

1,156 |

35% |

|

South Dakota |

1,895 |

1,167 |

38% |

|

Tennessee |

1,985 |

1,211 |

39% |

|

Texas |

1,553 |

1,042 |

33% |

|

Utah |

1,790 |

1,179 |

34% |

|

Virginia |

1,366 |

934 |

32% |

|

Washington |

1,566 |

983 |

37% |

|

West Virginia |

2,064 |

1,305 |

37% |

|

Wisconsin |

1,996 |

1,176 |

41% |

|

Wyoming |

2,315 |

1,299 |

44% |

Source: Prepared by CRS; final rule target and baseline data from EPA, CO2 Emission Performance Rate and Goal Computation Technical Support Document for CPP Final Rule, August 2015, and accompanying spreadsheets, http://www2.epa.gov/cleanpowerplan/clean-power-plan-final-rule-technical-documents. The interim and final targets are codified in 40 C.F.R. Part 60, Subpart UUUU, Table 2.

Notes: EPA did not establish emission rate goals for Vermont and the District of Columbia because they do not currently have affected EGUs. Although Alaska and Hawaii had targets in the proposed rule, in its final rule, EPA stated that Alaska, Hawaii, and the two U.S. territories with affected EGUs (Guam and Puerto Rico) will not be required to submit state plans on the schedule required by the final rule, because EPA "does not possess all of the information or analytical tools needed to quantify" the best system of emission reduction for these areas. EPA stated it will "determine how to address the requirements of section 111(d) with respect to these jurisdictions at a later time" (EPA, "Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units," Final Rule, 80 Federal Register 64743, October 23, 2015).

Q: How did EPA calculate the state-specific mass-based targets?

A: EPA's conversion from emission rate targets to mass-based targets involved two steps. First, EPA multiplied a state's emission rate target (lbs. CO2/MWh) for a particular year (e.g., 2022) by the state's 2012 CO2 generation baseline (MWh). This yields an initial mass-based value for that year.

Second, EPA determined the amount of renewable energy generation (pursuant to building block 3) that would not be needed to achieve the emission rate targets. This "excess" generation is available because EPA chose the least stringent of the three regional CO2 performance rates as the national CO2 performance rate.7876 EPA explained:

Due to the nature of the emission performance rate methodology, which selects the highest of the three interconnection-based values for each source category as the CO2 emission performance rate, there are cost-effective lower-emitting generation opportunities quantified under the building blocks that are not necessary for affected EGUs in the Western and Texas interconnections to demonstrate compliance at historical generation levels.79

EPA calculated the CO2 emissions associated with this "excess" generation and allocated the CO2 emissions to all of the states based on their 2012 generation, increasing their annual mass-based targets. As a result, some of the states' 2030 mass-based targets are higher than their 2012 emission baselines.

EPA based the renewable energy allocation on each state's share of total electricity generation in 2012 from affected EGUs. For example, in 2012, Florida's affected EGUs accounted for 8% of the generation from all affected EGUs nationwide, so Florida received 8% of the excess renewable energy generation in the mass-based calculation.

Q: What are the state-specific mass-based targets?

A: Table 3 lists the state-specific, mass-based targets from EPA's final rule. The table compares the 2030 targets with the 2012 baselines as calculated for the final rule and provides a percentage change between the two values. Most of the states have emission reduction requirements, but three states (Connecticut, Idaho, and Maine) have 2030 targets that are higher than their 2012 baselines (as discussed above).

Table 3. State-Specific 2012 CO2 Emission Baselines and 2030 CO2 Emission Targets

Short Tons—Alphabetical by State

|

State |

2012 CO2 Emission Baseline |

2030 CO2 Emission Targets |

Percentage Change |

|

Alabama |

75,571,781 |

56,880,474 |

-25% |

|

Alaska |

Not established |

Not established |

Not established |

|

Arizona |

40,465,035 |

30,170,750 |

-25% |

|

Arkansas |

43,416,217 |

30,322,632 |

-30% |

|

California |

49,720,213 |

48,410,120 |

-3% |

|

Colorado |

43,209,269 |

29,900,397 |

-31% |

|

Connecticut |

6,659,803 |

6,941,523 |

4% |

|

Delaware |

5,540,292 |

4,711,825 |

-15% |

|

Florida |

124,432,195 |

105,094,704 |

-16% |

|

Georgia |

62,843,049 |

46,346,846 |

-26% |

|

Hawaii |

Not established |

Not established |

Not established |

|

Idaho |

1,438,919 |

1,492,856 |

4% |

|

Illinois |

102,208,185 |

66,477,157 |

-35% |

|

Indiana |

110,559,916 |

76,113,835 |

-31% |

|

Iowa |

38,135,386 |

25,018,136 |

-34% |

|

Kansas |

34,655,790 |

21,990,826 |

-37% |

|

Kentucky |

92,775,829 |

63,126,121 |

-32% |

|

Louisiana |

44,391,194 |

35,427,023 |

-20% |

|

Maine |

2,072,157 |

2,073,942 |

0.1% |

|

Maryland |

20,171,027 |

14,347,628 |

-29% |

|

Massachusetts |

13,125,248 |

12,104,747 |

-8% |

|

Michigan |

69,860,454 |

47,544,064 |

-32% |

|

Minnesota |

34,668,506 |

22,678,368 |

-35% |

|

Mississippi |

27,443,309 |

25,304,337 |

-8% |

|

Missouri |

78,039,449 |

55,462,884 |

-29% |

|

Montana |

19,147,321 |

11,303,107 |

-41% |

|

Nebraska |

27,142,728 |

18,272,739 |

-33% |

|

Nevada |

15,536,730 |

13,523,584 |

-13% |

|

New Hampshire |

4,642,898 |

3,997,579 |

-14% |

|

New Jersey |

19,269,698 |

16,599,745 |

-14% |

|

New Mexico |

17,339,683 |

12,412,602 |

-28% |

|

New York |

34,596,456 |

31,257,429 |

-10% |

|

North Carolina |

67,277,341 |

51,266,234 |

-24% |

|

North Dakota |

33,757,751 |

20,883,232 |

-38% |

|

Ohio |

102,434,817 |

73,769,806 |

-28% |

|

Oklahoma |

52,862,077 |

40,488,199 |

-23% |

|

Oregon |

9,042,668 |

8,118,654 |

-10% |

|

Pennsylvania |

119,989,743 |

89,822,308 |

-25% |

|

Rhode Island |

3,735,786 |

3,522,225 |

-6% |

|

South Carolina |

35,893,265 |

25,998,968 |

-28% |

|

South Dakota |

5,121,124 |

3,539,481 |

-31% |

|

Tennessee |

41,387,231 |

28,348,396 |

-32% |

|

Texas |

251,848,335 |

189,588,842 |

-25% |

|

Utah |

32,166,243 |

23,778,193 |

-26% |

|

Virginia |

35,733,502 |

27,433,111 |

-23% |

|

Washington |

15,237,542 |

10,739,172 |

-30% |

|

West Virginia |

72,318,917 |

51,325,342 |

-29% |

|

Wisconsin |

42,317,602 |

27,986,988 |

-34% |

|

Wyoming |

50,218,073 |

31,634,412 |

-37% |

Source: Prepared by CRS using data from EPA, CO2 Emission Performance Rate and Goal Computation Technical Support Document for CPP Final Rule (August 2015). The interim and final targets are codified in 40 C.F.R. Part 60, Subpart UUUU, Table 3.

Notes: EPA did not establish emission targets for Vermont and the District of Columbia because they do not currently have affected EGUs. Although Alaska and Hawaii had targets in the proposed rule, in its final rule, EPA stated that Alaska, Hawaii, and the two U.S. territories with affected EGUs (Guam and Puerto Rico) will not be required to submit state plans on the schedule required by the final rule, because EPA "does not possess all of the information or analytical tools needed to quantify" the best system of emission reduction for these areas. EPA stated it will "determine how to address the requirements of section 111(d) with respect to these jurisdictions at a later time" (EPA, "Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units," Final Rule, 80 Federal Register 64743, October 23, 2015).

Q: Does the Clean Power Plan apply to EGUs on Indian lands?

A: The final rule established emission rate and emission targets for three areas of Indian country:

- the Navajo Nation,

- the Ute Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and

- the Fort Mojave tribe.

The targets (Table 4) are based on two facilities in the Navajo Nation (the Navajo Generating Station and the Four Corners Power Plant), the South Point Energy Center on the Fort Mojave Reservation, and the Bonanza Power Plant on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation.

|

Area of Indian Land |

2012 CO2 Emission Rate Baseline |

2030 CO2 Emission Rate Target |

Percentage Change |

2012 CO2 Emission Baseline |

2030 CO2 Emission Targets |

Percentage Change |

|

Fort Mojave Tribe |

858 |

771 |

-10% |

583,530 |

588,519 |

1% |

|

Navajo Nation |

2,121 |

1,305 |

-38% |

31,416,873 |

21,700,586 |

-31% |

|

Ute Tribe |

2,145 |

1,305 |

-39% |

3,314,097 |

2,263,431 |

-32% |

Source: Prepared by CRS. The targets are codified in 40 C.F.R. Part 60, Subpart UUUU, Table 2 (emission rates) and Table 3 (mass-based).

EPA stated that tribes have "the opportunity, but not the obligation," to establish and submit a plan (after obtaining the necessary approval from EPA) to meet their emission rate targets. If a tribe does not seek approval to submit its own plan, EPA is responsible for establishing a plan, if the agency determines, at a later date, that "a plan is necessary or appropriate."80

On October 23, 2015, in addition to finalizing the CPP and NSPSs for EGUs, EPA proposed a rule for a federal plan, which would be implemented by EPA in states that do not submit a satisfactory state implementation plan.8179 In the federal plan rule, EPA proposed "to find that it is necessary or appropriate to regulate affected EGUs in each of the three areas of Indian country that have affected EGUs under the proposed federal plan."8280 Therefore, EPA would develop and implement the federal plan for EGUs in the relevant Indian lands, unless the tribal governments received EPA approval to submit their own plans to meet their emission targets. However, pursuant to President Trump's Executive Order 13783, EPA withdrew the federal plan proposed rule on April 3, 2017.83

Although EPA withdrew the proposed federal plan, the targets in Indian lands established by the final rule remain. If the final rule is upheld in court, the agency would need to develop and finalize a new federal plan if it determines that "a plan is necessary or appropriate" if a tribe does not seek approval to submit its own plan.

Q: Would states and companies that have already reduced GHG emissions receive credit for doing so?

A: States would not receive "credit" in their emission rate or emission targets for emission reduction measures already taken. Whether individual power companies would receive some type of credit would be decided by states as they develop their implementation plans. The rule requires each state to submit an implementation plan to EPA that identifies what measures/regulations the state would implement to reach its goal.

EPA used 2012 data to prepare the national CO2 emission performance rates and each state's emission rate and emission targets. The final rule does not have a process for providing credit for emissions reductions made prior to 2012. EPA contended that states that began action prior to 2012, including a shift to less carbon-intensive energy sources or energy efficiency improvements, would be "better positioned" to meet state-specific emission rate goals.8482 However, some stakeholders would likely argue that the 2012 demarcation is unfair to states where investments in substantial amounts of low-carbon generation technology and/or energy efficiency improvements were made prior to 2012.

Q: How does EPA's Clean Power Plan interact with existing GHG emission reduction programs in the states, namely the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and California's climate policies?

A: A number of U.S. states have already required greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions. The most aggressive actions have come from a coalition of states from the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions—the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative8583—and California.8684

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a cap-and-trade system involving nine states that took effect in 2009.8785 RGGI applies to CO2 emissions from electric power plants with capacities to generate 25 megawatts or more.

Pursuant to legislation passed in 2006, California established a cap-and-trade program that took effect in 2013. California's cap applies to multiple GHGs from multiple economic sectors, covering approximately 85% of California's GHG emissions. In addition, California has other policies and regulations that address GHG emissions directly and indirectly.88

EPA allows states considerable flexibility in meeting their emission rates or emission targets. For example, states can establish new programs to meet their goals or use existing programs and regulations. Moreover, states can meet their goals individually or collaborate with other states to create (or use existing) multistate plans.

It is uncertain whether the scope and stringency of the RGGI program or the California system would be sufficient to meet the targets in EPA's final rule. In particular, the emission caps in both programs do not go beyond 2020. In addition, legal challenges to California's program have raised some uncertainty concerning the program's future.89

Q: What role is there for "outside-the-fence" emission reductions?

In August 2017, RGGI state officials announced an initial agreement to extend the RGGI program through 2030, with additional emission reductions.89 The agreement is still in its early stages and will undergo a public comment process. RGGI states would then need to update their respective statutes or regulations to implement the program changes.A:Both California and the RGGI states have taken action to extend the emission caps in their respective programs beyond 2020. In July 2017, California enacted AB 398, which extends the state's cap-and-trade program through 2030.87 The legislation received a two-thirds vote, which may help avoid subsequent legal challenges.88

Although outside-the-fence activities were a major component of EPA's target calculations, the degree to which outside-the-fence emission reductions would be used would depend on the policies and requirements states implement through their state plans.

Q: How would new fossil-fuel-fired power plants and their resulting electricity generation and emissions factor into a state's emission rate or emission calculations?

A: In EPA's final rule, new EGUs are treated differently under rate-based and mass-based plans. Under a mass-based approach, states have the option of including new fossil-fuel-fired sources in their emission reduction plans. In its final rule, EPA provided mass-based emission targets that include projections of new sources (described by EPA as a "new source complement").90 This inclusion would facilitate emissions trading within the state and with other states. These new sources would remain subject to the performance standards under CAA Section 111(b).91

In its proposed rule, EPA considered whether states could include new NGCC units in their emission rate calculations. In the final rule, EPA specifically prohibited states from including new NGCC units as a means of directly adjusting the state's emission rate. However, if a new NGCC were to effectively replace existing electricity generation from a coal-fired EGU, the state's emission rate would likely decrease with the removal of the coal-fired unit.92

Q: What role does nuclear power play in the Clean Power Plan rule?

A: EPA modified its treatment of nuclear power in the final rule. In its proposed rule, EPA factored "at risk" nuclear power (estimated at 5.8% of existing capacity) into the state emission rate methodology. As a result, states would have had an incentive to maintain the at-risk nuclear power generation so their emission rates would not increase (all else being equal). The final rule does not include at-risk nuclear generation in its building block calculations.

In addition, in its final rule, EPA decided not to include under-construction nuclear power capacity in the emission rate calculations. Including the estimated generation from these anticipated units in the emission rate equation would have substantially lowered the emission rate targets in Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee. If the final rule had retained this feature, and these nuclear units did not enter service, these three states would likely have more difficulty achieving their emission rate goals.

EPA clarified that the final rule would allow the generation from under-construction units, new nuclear units, and capacity upgrades to help sources meet emission rate or emission targets.

Q: What role does energy efficiency play in the Clean Power Plan final rule?

A: In EPA's proposed rule, demand-side energy efficiency (EE) improvements were part of the agency's state-specific emission rate target calculations ("building block 4"). However, in its final rule, EPA did not include demand-side EE improvements as part the agency's national CO2 emission performance rate calculations, which underlie the state-specific targets.

Although EPA removed demand-side EE assumptions from its target calculations, states may choose to employ EE improvement activities as part of their plans to meet their targets. In particular, the final rule included a new voluntary program that provided incentives for early investments (in 2020 and 2021) in EE programs in low-income communities (as discussed below).

In addition, in its Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) for the final rule, EPA assumed that EE will play an important role in meeting compliance obligations:

[EE] is a highly cost-effective means for reducing CO2 from the power sector, and it is reasonable to assume that a regulatory requirement to reduce CO2 emissions will motivate parties to pursue all highly cost-effective means for making emission reductions accordingly, regardless of what particular emission reduction measures were assumed in determining the level of that regulatory requirement.93

Q: What role does biomass play in the Clean Power Plan?

A: In its final rule, EPA would allow states to use "qualified biomass" as a means of meeting state-specific reduction requirements. EPA defined qualified biomass as a "feedstock that is demonstrated as a method to control increases of CO2 levels in the atmosphere."94 This appears to be a narrower approach than was taken in the proposed rule. Also, EPA required additional accounting and reporting requirements if a state decides to use qualified biomass. The agency gave some indication as to which biomass types may qualify.95

Q: What is the Clean Energy Incentive Program?96

A: The Clean Energy Incentive Program (CEIP) is a voluntary program that would complement the CPP. The CEIP encourages states to support energy efficiency measures and renewable energy projects before the first CPP compliance obligations are scheduled to take effect in 2022. In order to participate in the CEIP, states would need to include particular design elements in their final state plans.

EPA established the framework of the CEIP in its CPP final rule in 2015. EPA issued a proposed rule for the CEIP that was published in the Federal Register on June 30, 2016.97 The proposed rule provided additional details, clarified certain elements that were previously outlined, and altered some of the program eligibility requirements. In response to President Trump's Executive Order 13783 to review and potentially revise the CPP, EPA withdrew the CEIP 2016 proposed rule on April 3, 2017.98 The following discussion describes the CEIP as established in the CPP 2015 final rule.

The CEIP would create a system to award credits to energy efficiency projects in low-income communities and renewable energy projects (only wind and solar) in participating states. The credits would take the form of emission rate credits (ERCs) or emission allowances, depending on whether a state uses an emission rate or mass-based target, respectively. The credits could be sold to or used by an affected emission source to comply with the state-specific requirements (e.g., emission rate or mass-based targets).

Renewable energy projects would receive one credit (either an allowance or ERC) from the state and one credit from EPA for every two MWh of solar or wind generation. EE projects in low-income communities would receive double credits: For every two MWh of avoided electricity generation, EE projects will receive two credits from the state and two credits from EPA. EPA would match up to the equivalent of 300 million short tons in credits during the CEIP program life. The amount of EPA credits potentially available to each state participating in the CEIP depends on the relative amount of emission reduction each state is required to achieve compared to its 2012 baseline. Thus, states with greater reduction requirements would have access to a greater share of the EPA credits.

To generate the credits, states would effectively borrow from their mass-based or rate-based compliance targets for the interim 2022-2029 compliance period. EPA would provide its share of credits from a to-be-established reserve.

Q: How does the final Clean Power Plan differ from the proposed rule?

A: EPA's 2015 final rule is different from EPA's 2014 proposed rule in multiple respects. A key change is the establishment of national CO2 emission performance rates for the sources affected by the rule: fossil-fuel-fired electric steam generating units and stationary combustion turbines.

EPA used what it called "building blocks" to derive the national emission performance rates and state-specific targets based on the national rates. The final rule's state-specific targets differ from those in the proposed rule, because in the final rule, EPA applied its building block assumptions to regional-level data to create regional CO2 emission performance rates. These regional rates led to national rates, which were then used to produce state-specific emission rate and emission targets. By contrast, in the proposed rule, EPA applied building blocks to state-level data, yielding different outcomes.

In addition, EPA modified its target creation methodology (e.g., building blocks) in the final rule. Key modifications include adjustments to

- renewable energy,

- natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) displacement of coal-fired electricity generation,

- heat rate improvements at coal-fired units,

- energy efficiency,

- nuclear power, and

- state-specific 2012 baselines.

These methodological changes impact only the state-specific targets. States can choose to use a variety of mechanisms to meet their targets, including, but not limited to, the emission reduction activities assumed in EPA's methodology.

In addition, state compliance with the final rule begins in 2022 instead of 2020 under the proposed rule. The final rule has additional compliance options available to states, particularly in the form of state plans.

Next Steps

Q: What are the next steps in the Clean Power Plan's implementation?

A: EPA cannot enforce the rule while it is stayed, pursuant to Supreme Court order, for the duration of the litigation over the rule.99 Some states have not begun implementation planning or have stopped implementation planning for the duration of the stay, while some states have indicated that they intend to continue planning.100

The final rule, as promulgated, set a deadline of September 6, 2016, for each state to submit a State Implementation Plan to EPA.101 In lieu of a completed plan, the final rule authorized a state to make an initial submittal by that date and request up to two additional years to complete its submission. For the extension of time to be granted, the final rule required the initial submittal to address three components sufficiently to demonstrate that the state is able to submit a final plan by September 6, 2018:

- 1. an identification of the final plan approach or approaches under consideration, including a description of progress made to date;

- 2. an appropriate explanation for why the state needs additional time to submit a final plan; and

- 3. a demonstration of how the state has been engaging with the public, including vulnerable communities, and a description of how it intends to meaningfully engage with community stakeholders during the additional time.

In light of the stay, these near-term deadlines lack legal effect. If the rule is ultimately upheld or remanded back to EPA, then initial compliance deadlines would likely be extended until a revised rule is finalized.102 Following submission of final plans, EPA would review the submittals to determine whether they are approvable.

The interim compliance period for the rule, as promulgated, begins in 2022, although it is possible that this compliance date could be delayed as well if the rule is ultimately upheld. EPA set an eight-year interim period that begins in 2022 and runs through 2029 and is separated into three steps (2022-2024, 2025-2027, and 2028-2029), each with its own interim goal. Affected EGUs would have to meet each of the step 1, 2, and 3 CO2 emission performance rates or follow an EPA-approved emissions reduction trajectory designed by the state itself for the eight-year period from 2022 to 2029. The final rule, as promulgated, requires compliance with the state's final goal by 2030.

Q: What incentives are there for early compliance?

A: In general, the CPP states

Incremental emission reduction measures, such as RE [renewable energy] and demand-side EE, can be recognized as part of state plans, but only for the emission reductions they provide during a plan performance period. Specifically, this means that measures installed in any year after 2012 are considered eligible measures under this final rule, but only the quantified and verified MWh of electricity generation or electricity savings that they produce in 2022 and future years may be applied toward adjusting a CO2 emission rate.103

As noted earlier, however, the CPP provided incentives for states to adopt measures to reduce emissions in 2020 and 2021 under the CEIP. Under the CEIP, EPA would provide credits against CPP requirements for wind and solar projects that commence construction after the date that a state submits its final plan to EPA and that generate metered electricity in 2020 and 2021. EPA would provide double credits for EE measures that result in reducing electricity consumption in low-income communities in participating states in the same two years.104

Q: If the Clean Power Plan is upheld, what happens if a state fails to submit an adequate plan by the appropriate deadline?

A: EPA cannot compel a state to submit a Section 111(d) plan. Rather, if a state fails to submit a satisfactory plan by EPA's deadline, CAA Section 111(d) authorizes EPA to prescribe a plan for the state. This authority is the same, Section 111(d) says, as EPA's authority to prescribe a federal implementation plan (FIP) when a state fails to submit a state implementation plan to achieve a National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS).105 EPA proposed a model FIP on August 3, 2015 (which appeared in the Federal Register on October 23, 2015), but withdrew it as directed by Executive Order 13783.106 If the CPP is upheld in court, EPA would need to re-propose a FIP for states that fail to submit an approvable plan to EPA.

Q: What would the proposed FIP have required?

A: Just as EPA cannot compel a state to submit a state plan, it also cannot compel a state to meet its average emission targets. FIPs, therefore, would require compliance by individual EGUs in the affected state. The proposed FIP would set either emission rates or emission limits for affected EGUs. According to EPA, the stringency of the federal plan would be the same as the national CO2 emission performance rates specified in the CPP.107 In addition, the FIP would establish a trading program that could be used by affected EGUs to meet those limits. If the agency chooses to implement a mass-based program, the proposal envisions the allocation of allowances to individual EGUs based on their historical emissions during the years 2010-2012.108

Although the proposed rule set forth both a mass-based and a rate-based option for the proposed trading program, the agency stated that it intended to finalize a single approach—that is, either a rate-based or a mass-based approach—in all FIPs "in order to enhance the consistency of the federal trading program, achieve economies of scale through a single, broad trading program, ensure efficient administration of the program, and simplify compliance planning for affected EGUs."109 While accepting comments on both approaches, the agency appeared to be leaning toward a mass-based option for use in the FIPs, stating that it

would be more straightforward to implement compared to the rate-based trading approach, both for industry and for the implementing agency. The EPA, industry, and many state agencies have extensive knowledge of and experience with mass-based trading programs. The EPA has more than two decades of experience implementing federally-administered mass-based emissions budget trading programs including the Acid Rain Program (ARP) sulfur dioxide (SO2) trading program, the Nitrogen Oxides (NOX) Budget Trading Program, CAIR, and CSAPR. The tracking system infrastructure exists and is proven effective for implementing such programs.110

EPA noted that, under its proposed FIP rule, states with FIPs could still participate in the implementation of the program under these conditions:

- After a federal plan is put in place for a particular state, the state would still be able to submit a plan, which, if approved, would allow the state and its EGUs to exit the federal plan.