The HUD Homeless Assistance Grants: Programs Authorized by the HEARTH Act

The Homeless Assistance Grants, administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), were first authorized by Congress in 1987 as part of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (P.L. 100-77). Since their creation, the grants have been composed of three or four separate programs, though for the majority of their existence, between 1992 and 2012, the grant programs were unchanged. During this time period, there were four programs authorized and funded by Congress: the Emergency Shelter Grants (ESG), the Supportive Housing Program (SHP), the Shelter Plus Care (S+C) program, and the Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation for Single Room Occupancy Dwellings (SRO) program. Funds for the ESG program were used primarily for the short-term needs of homeless persons, such as emergency shelter, while the other three programs addressed longer-term transitional and permanent housing needs.

The composition of the Homeless Assistance Grants changed when Congress enacted the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act as part of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act in the 111th Congress (P.L. 111-22). The HEARTH Act renamed the ESG program (it is now called the Emergency Solutions Grants) and expanded the way in which funds can be used to include homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing (quickly finding housing for families who find themselves homeless), and it consolidated SHP, S+C, and SRO into one program called the Continuum of Care (CoC) program. A third program carved out of the CoC program to assist rural communitiesthe Rural Housing Stability Assistance Programwas also created by P.L. 111-22. In addition, the HEARTH Act broadened HUD’s definition of homelessness. The changes in P.L. 111-22 had repercussions for the way in which funds are distributed to grantees, the purposes for which grantees may use funds, and who may be served.

HUD began to implement the ESG program in FY2011 and the CoC program in FY2012, and it released proposed regulations for the Rural Housing Stability (RHS) grants in March 2013 (and has not yet provided RHS grants). Funds for the ESG program, in addition to being available for homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing, can be used for emergency shelter and supportive services. CoC program funds can be used to provide permanent supportive housing, transitional housing, supportive services, and rapid rehousing. If the RHS program is implemented, rural communities will have greater flexibility in who they are able to serve (those assisted may not necessarily meet HUD’s definition of “homeless individual”), and may use funds for a variety of housing and services options.

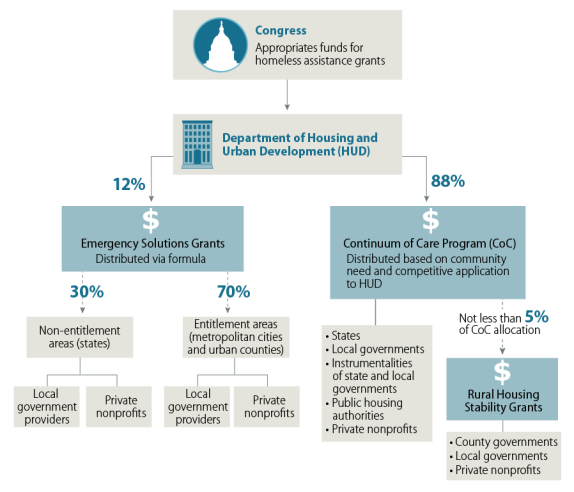

HUD uses one method to distribute funds for the ESG program and another method to distribute funds for the CoC program. The ESG program distributes funds to states, counties, and metropolitan areas using the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program formula, while the CoC grants are distributed through a competitive process, though the CDBG formula plays a role in determining community need. In July 2016, HUD proposed to change the CoC formula so that it no longer relies on the CDBG formula distribution.

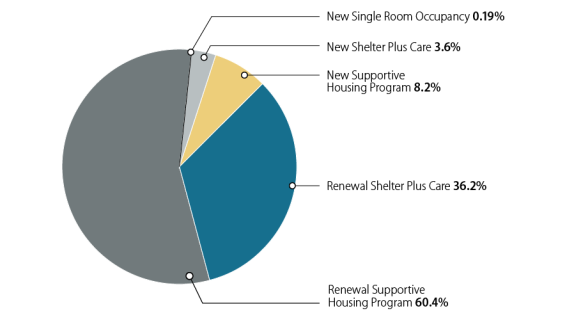

Funding for the Homeless Assistance Grants has increased by almost $1 billion in the last 10 years, reaching nearly $2.4 billion in FY2017 compared to $1.4 billion in FY2007 (see Table 3). Despite funding increases, the need to renew existing grants requires the majority of funding. In FY2016, 90% of the CoC program allocation was used to renew existing grants.

The HUD Homeless Assistance Grants: Programs Authorized by the HEARTH Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- An Introduction to the Homeless Assistance Grants

- Report Organization

- The Definition of Homelessness

- Documenting Homeless Status

- Definition of Chronically Homeless Person

- The Emergency Solutions Grants Program (ESG)

- Distribution of ESG Funds

- Transition to the Continuum of Care Program

- The Continuum of Care and Collaborative Applicants

- Features of the Continuum of Care Program

- Eligible Applicants

- Program Components and Eligible Costs

- The Grant Application Process

- Who May Be Served

- Distribution of Continuum of Care Program Funds

- HUD Determination of Community Need

- Competitive Process

- Features of the FY2017 Competitive Process

- Features of the FY2016 Competitive Process

- Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program

- Funding for the Homeless Assistance Grants

- Issues Regarding the Homeless Assistance Grants

- Contract Renewals for the CoC Program and Predecessor Programs

- The Role of the Community Development Block Grant Formula

- HUD Proposed Rule to Change the CoC Program Formula

Figures

Tables

Summary

The Homeless Assistance Grants, administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), were first authorized by Congress in 1987 as part of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (P.L. 100-77). Since their creation, the grants have been composed of three or four separate programs, though for the majority of their existence, between 1992 and 2012, the grant programs were unchanged. During this time period, there were four programs authorized and funded by Congress: the Emergency Shelter Grants (ESG), the Supportive Housing Program (SHP), the Shelter Plus Care (S+C) program, and the Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation for Single Room Occupancy Dwellings (SRO) program. Funds for the ESG program were used primarily for the short-term needs of homeless persons, such as emergency shelter, while the other three programs addressed longer-term transitional and permanent housing needs.

The composition of the Homeless Assistance Grants changed when Congress enacted the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act as part of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act in the 111th Congress (P.L. 111-22). The HEARTH Act renamed the ESG program (it is now called the Emergency Solutions Grants) and expanded the way in which funds can be used to include homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing (quickly finding housing for families who find themselves homeless), and it consolidated SHP, S+C, and SRO into one program called the Continuum of Care (CoC) program. A third program carved out of the CoC program to assist rural communities―the Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program―was also created by P.L. 111-22. In addition, the HEARTH Act broadened HUD's definition of homelessness. The changes in P.L. 111-22 had repercussions for the way in which funds are distributed to grantees, the purposes for which grantees may use funds, and who may be served.

HUD began to implement the ESG program in FY2011 and the CoC program in FY2012, and it released proposed regulations for the Rural Housing Stability (RHS) grants in March 2013 (and has not yet provided RHS grants). Funds for the ESG program, in addition to being available for homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing, can be used for emergency shelter and supportive services. CoC program funds can be used to provide permanent supportive housing, transitional housing, supportive services, and rapid rehousing. If the RHS program is implemented, rural communities will have greater flexibility in who they are able to serve (those assisted may not necessarily meet HUD's definition of "homeless individual"), and may use funds for a variety of housing and services options.

HUD uses one method to distribute funds for the ESG program and another method to distribute funds for the CoC program. The ESG program distributes funds to states, counties, and metropolitan areas using the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program formula, while the CoC grants are distributed through a competitive process, though the CDBG formula plays a role in determining community need. In July 2016, HUD proposed to change the CoC formula so that it no longer relies on the CDBG formula distribution.

Funding for the Homeless Assistance Grants has increased by almost $1 billion in the last 10 years, reaching nearly $2.4 billion in FY2017 compared to $1.4 billion in FY2007 (see Table 3). Despite funding increases, the need to renew existing grants requires the majority of funding. In FY2016, 90% of the CoC program allocation was used to renew existing grants.

An Introduction to the Homeless Assistance Grants

Homelessness in America has always existed, but it did not come to the public's attention as a national issue until the 1970s and 1980s, when the characteristics of the homeless population and their living arrangements began to change. Throughout the early and middle part of the 20th century, homelessness was typified by "skid rows"—areas with hotels and single-room occupancy dwellings where transient single men lived.1 Skid rows were usually removed from the more populated areas of cities, and it was uncommon for individuals to actually live on the streets.2 Beginning in the 1970s, however, the homeless population began to grow and become more visible to the general public. According to studies from the time, homeless persons were no longer almost exclusively single men, but included women with children; their median age was younger; they were more racially diverse (in previous decades the observed homeless population was largely white); they were less likely to be employed (and therefore had lower incomes); they were mentally ill in higher proportions than previously; and individuals who were abusing or had abused drugs began to become more prevalent in the population.3

A number of reasons have been offered for the growth in the number of homeless persons and their increasing visibility. Many cities demolished skid rows to make way for urban development, leaving some residents without affordable housing options.4 Other possible factors contributing to homelessness include the decreased availability of affordable housing generally, the reduced need for seasonal unskilled labor, the reduced likelihood that relatives will accommodate homeless family members, the decreased value of public benefits, and changed admissions standards at mental hospitals.5 The increased visibility of homeless people was due, in part, to the decriminalization of actions such as public drunkenness, loitering, and vagrancy.6

In the 1980s, Congress first responded to the growing prevalence of homelessness with several separate grant programs designed to address the food and shelter needs of homeless individuals.7 Then, in 1987, Congress enacted the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act (McKinney Act), which created a number of new programs to comprehensively address the needs of homeless people, including food, shelter, health care, and education (P.L. 100-77). The act was later renamed the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (McKinney-Vento) in P.L. 106-400 after its other prominent sponsor, Bruce F. Vento.8

Among the programs authorized in the McKinney-Vento Act were four grants to provide housing and related assistance to homeless persons: the Emergency Shelter Grants (ESG) program, the Supportive Housing Demonstration program, the Supplemental Assistance for Facilities to Assist the Homeless (SAFAH) program, and the Section 8 Moderate Rehabilitation Assistance for Single Room Occupancy Dwellings (SRO) program. These four programs, administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), were created to provide temporary and permanent housing to homeless persons, along with supportive services. Over the years, Congress changed the makeup of the Homeless Assistance Grants, but for 20 years, from 1992 to 2012, the same four grant programs composed the Homeless Assistance Grants. These were the ESG program, the Supportive Housing Program (SHP), the Shelter Plus Care (S+C) program, and the SRO program.9

On May 20, 2009, for the first time since 1992, the Homeless Assistance Grants were reauthorized as part of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act (P.L. 111-22). The law is often referred to as the "HEARTH Act" after its title in P.L. 111-22 (the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act). The HEARTH Act changed the makeup of the four existing grants—the SHP, S+C, and SRO programs were combined into one grant called the "Continuum of Care" (CoC) program; the ESG program was renamed the "Emergency Solutions Grants"; and rural communities were to have the option of competing for funds under a new Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program (RHS). The way in which the funds are distributed, the purposes for which grantees may use funds, and the people who may be served have also changed. The HEARTH Act authorized the Continuum of Care Program, together with the Emergency Solutions Grants Program, at $2.2 billion in FY2010 and such sums as necessary for FY2011.

Report Organization

In FY2011, HUD first awarded funds under the new ESG program, and FY2012 was the first year that funds were awarded pursuant to the CoC program. New regulations regarding the definition of homelessness became effective on January 5, 2012, and HUD released proposed regulations for the RHS program on March 27, 2013 (with comments due by May 28, 2013). This report has multiple sections describing the implementation of the HEARTH Act provisions. It describes

- the HEARTH Act changes to the definition of homelessness in the section "The Definition of Homelessness";

- the way in which ESG operated prior to HEARTH Act implementation as well as the changes made beginning in FY2011 in the section "The Emergency Solutions Grants Program (ESG)";

- components of the competitive Homeless Assistance Grants prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, and how they have been absorbed in the CoC program in the section "Transition to the Continuum of Care Program";

- how funds are distributed pursuant to the CoC program in the section "Distribution of Continuum of Care Program Funds"; and

- the housing and services that are authorized to be provided through the RHS program and how communities are to receive funds in the section "Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program."

The Definition of Homelessness

The way in which homelessness is defined is an important part of how the Homeless Assistance Grants operate, as it determines who communities may assist with the grants they receive. The definition had been the subject of debate for a number of years, with some finding that the definition governing the HUD homeless programs was too restrictive when compared to definitions used in other federal programs that assist those experiencing homelessness.

Until enactment of the HEARTH Act, "homeless individual" was defined in Section 103(a) of the McKinney-Vento Act as

(1) an individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence; and (2) an individual who has a primary nighttime residence that is—(A) a supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (including welfare hotels, congregate shelters, and transitional housing for the mentally ill); (B) an institution that provides a temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized; or (C) a public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings.

This definition was sometimes described as requiring one to be literally homeless in order to meet its requirements10—either living in emergency accommodations or having no place to stay.

The HEARTH Act expanded the definition of "homeless individual,"11 and on December 5, 2011, HUD issued final regulations clarifying aspects of the HEARTH Act definition of homelessness.12 The regulation took effect on January 4, 2012. The HEARTH Act retained the original language of the definition with some minor changes, but also added provisions that move away from the requirement for literal homelessness and toward housing instability as a form of homelessness. Each subsection below explains separate ways in which the HEARTH Act changed the definition of homelessness.

The Original McKinney-Vento Act Language

The HEARTH Act made minor changes to the existing language in the McKinney-Vento Act. The law continues to provide that a person is homeless if they lack "a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence," and if their nighttime residence is a place not meant for human habitation, if they live in a shelter, or if they are a person leaving an institution who had been homeless prior to being institutionalized. The HEARTH Act added that those living in hotels or motels paid for by a government entity or charitable organization are considered homeless, and it included all those persons living in transitional housing, not just those residing in transitional housing for the mentally ill as in prior law. The amended law also added locations that are not considered suitable places for people to sleep, including cars, parks, abandoned buildings, bus or train stations, airports, and campgrounds.

When HUD issued its final regulation in December 2011, it clarified that a person exiting an institution cannot have been residing there for more than 90 days and still be considered homeless.13 In addition, where the law states that a person "who resided in a shelter or place not meant for human habitation" prior to institutionalization, the "shelter" means emergency shelter, and does not include transitional housing.14

Imminent Loss of Housing

P.L. 111-22 added to the current definition those individuals and families who meet all of the following criteria:

- They will "imminently lose their housing," whether it be their own housing, housing they are sharing with others, or a hotel or motel not paid for by a government or charitable entity. Imminent loss of housing is evidenced by an eviction requiring an individual or family to leave their housing within 14 days; a lack of resources that would allow an individual or family to remain in a hotel or motel for more than 14 days; or credible evidence that an individual or family would not be able to stay with another homeowner or renter for more than 14 days.

- They have no subsequent residence identified.

- They lack the resources or support networks needed to obtain other permanent housing.

HUD practice prior to passage of the HEARTH Act was to consider individuals and families who would imminently lose housing within seven days to be homeless.

Other Federal Definitions

P.L. 111-22 added to the definition of "homeless individual" unaccompanied youth and homeless families with children who are defined as homeless under other federal statutes. The law did not define the term youth, so in its final regulations HUD defined a youth as someone under the age of 25.15 In addition, the HEARTH Act did not specify which other federal statutes would be included in defining homeless families with children and unaccompanied youth. In its regulations, HUD listed seven other federal programs as those under which youth or families with children can be defined as homeless: the Runaway and Homeless Youth program; Head Start; the Violence Against Women Act; the Healthcare for the Homeless program; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program; and the McKinney-Vento Education for Children and Youth program.16

Five of these seven programs (all but Runaway and Homeless Youth and Health Care for the Homeless programs) either share the Education for Homeless Children and Youths definition, or use a very similar definition.

- The Department of Education defines homeless children and youth in part by reference to the Section 103 definition of homeless individuals as those lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.17 In addition, however, the ED program defines children and youth who are eligible for services to include those who are (1) sharing housing with other persons due to loss of housing or economic hardship; (2) living in hotels or motels, trailer parks, or campgrounds due to lack of alternative arrangements; (3) awaiting foster care placement; (4) living in substandard housing; and (5) children of migrant workers.18

- The Runaway and Homeless Youth program defines a homeless youth as either ages 16 to 22 (for transitional housing) or ages 18 and younger (for short-term shelter) and for whom it is not possible to live in a safe environment with a relative or for whom there is no other safe alternative living arrangement.19

- Under the Health Care for the Homeless program, a homeless individual is one who "lacks housing," and the definition includes those living in a private or publicly operated temporary living facility or in transitional housing.20

Youth and families who are defined as homeless under another federal program must meet each of the following criteria:

- They have experienced a long-term period without living independently in permanent housing. In its final regulation, HUD defined "long-term period" to mean at least 60 days.

- They have experienced instability as evidenced by frequent moves during this long-term period, defined by HUD to mean at least two moves during the 60 days prior to applying for assistance.21

- The youth or families with children can be expected to continue in unstable housing due to factors such as chronic disabilities, chronic physical health or mental health conditions, substance addiction, histories of domestic violence or childhood abuse, the presence of a child or youth with a disability, or multiple barriers to employment. Under the final regulation, barriers to employment may include the lack of a high school degree, illiteracy, lack of English proficiency, a history of incarceration, or a history of unstable employment.22

Communities are limited to using not more than 10% of Continuum of Care program funds to serve individuals and families defined as homeless under other federal statutes unless the community has a rate of homelessness less than one-tenth of 1% of the total population.23

Domestic Violence

Another change to the definition of homeless individual was added as subsection 103(b) to McKinney-Vento. The law now considers to be homeless anyone who is fleeing a situation of "domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, stalking, or other dangerous or life-threatening conditions in the individual's or family's current housing situation, including where the health and safety of children are jeopardized."24 The law also provides that an individual must lack the resources or support network to find another housing situation. The final regulation issued by HUD in December 2011 specified that the conditions either must have occurred at the primary nighttime residence or made the individual or family afraid to return to their residence.25

Documenting Homeless Status

For the first time, the regulations governing the Homeless Assistance Grants specify how housing and service providers should verify the homeless status of the individuals and families that they serve. (Previously, guidance had been provided in program handbooks.) The final regulations issued in December 2011 create different requirements depending both on the part of the statutory definition under which individuals or families find themselves homeless as well as the type of service provided. In general, it is preferred that service providers have third party documentation that an individual or family is homeless (such as an eviction order or verification from a family member with whom a homeless individual or family had lived). However, under some circumstances, it may also be acceptable to confirm homelessness based on intake worker observation or certification from the person or head of household who is homeless.26 Where someone is seeking assistance at an emergency shelter, through a street outreach program, or from a victim service provider, failure to separately verify homeless status should not prevent an individual or family from receiving immediate assistance.

Definition of Chronically Homeless Person

P.L. 111-22 also expanded the definition of "chronically homeless person," which had been defined in regulation.27 Under the regulation, the term had been defined as an unaccompanied individual who has been homeless continuously for one year or on four or more occasions in the last three years, and who has a disability.28 A regulation released by HUD on December 4, 2015 (and effective January 4, 2016) clarifies that four or more occasions of homelessness in the last three years must total at least 12 months, with at least seven nights separating each occasion.29

The HEARTH Act added to the definition of chronically homeless those homeless families with an adult head of household (or youth where no adult is present) who has a disability. The definition of disability specifically includes post traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Note, however, that to be considered chronically homeless, an individual or family has to be living in a place not meant for human habitation, a safe haven, or an emergency shelter; the HEARTH Act's changes to the definition of "homeless individual" do not apply to chronic homelessness. In addition, a person released from an institution will be considered chronically homeless as long as, prior to entering the institution, they otherwise met the definition of chronically homeless person, and had been institutionalized for fewer than 90 days. HUD began using the new definition in its administration of the Homeless Assistance Grants as part of the FY2010 competition.30

The Emergency Solutions Grants Program (ESG)

The Emergency Solutions Grants, until enactment of the HEARTH Act known as the Emergency Shelter Grants, was the first of the Homeless Assistance Grants to be authorized. It was established one year prior to enactment of McKinney-Vento as part of the Continuing Appropriations Act for FY1987 (P.L. 99-591).31 Funds are distributed to grantee states and local communities to assist those experiencing homelessness (see the next section for information on how funds are distributed). From its creation through FY2010, the funds distributed through the ESG program were provided primarily for the emergency shelter and service needs of homeless persons. However, when the ESG program was reauthorized as part of the HEARTH Act (P.L. 111-22), it not only changed its name, but the focus of the program was broadened to include an expanded role for homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing (assistance to quickly find permanent housing for individuals or families who find themselves homeless). On December 5, 2011, HUD issued interim regulations for the ESG program, and they became effective on January 4, 2012.32 Funding for the program's new purposes was made available as part of a second round of funding in FY2011.33 In FY2012 and thereafter, all funds awarded could be used for the ESG program activities as authorized by the HEARTH Act.

Eligible Activities Prior to Enactment of the HEARTH Act

Prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, ESG funds could be used for four main purposes: (1) the renovation, major rehabilitation, or conversion of buildings into emergency shelters; (2) services such as employment counseling, health care, and education; (3) homelessness prevention activities such as assistance with rent or utility payments; and (4) operational and administrative expenses.34 States and communities that received ESG funds were limited to using not more than 30% of the total ESG funds they received for services, not more than 30% for homelessness prevention activities, not more than 10% for staff costs, and not more than 5% for administrative costs.

Additional Eligible Activities After Enactment of the HEARTH Act

As amended by the HEARTH Act, ESG allows grantees to use a greater share of funds for homelessness prevention and rapid rehousing. Specifically, funds may be used for short- or medium-term rental assistance (tenant- or project-based) and housing relocation and stabilization services for individuals and families who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

At Risk of Homelessness: The law defines the term "at risk of homelessness" to include an individual or family with income at or below 30% of area median income and who has insufficient resources to attain housing stability. An individual or family must also meet one of the following conditions:35

- have moved for economic reasons at least twice during the last 60 days;

- are living with someone else due to economic hardship;

- have been notified in writing that their current housing will be terminated within 21 days;

- are living in a hotel or motel not paid for by a government or charitable entity;

- are living in overcrowded housing (more than 2 persons in an efficiency unit or more than 1.5 people per room otherwise);

- are leaving an institution such as a health or mental health care facility, foster care, or correctional facility; or

- are living in a housing situation that is unstable in some other way.

In addition, families with children and youth defined as homeless under other federal statutes are considered "at risk" of homelessness. As with the definition of homelessness generally, the other federal programs under which children and youth may be considered homeless are the Runaway and Homeless Youth program; Head Start; the Violence Against Women Act; the Healthcare for the Homeless program; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program; and the McKinney Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth program.36

Under the updated ESG program in the HEARTH Act, the amount of funds that grant recipients can use for emergency shelter and related supportive services are limited to the greater of 60% of their ESG allocation or the amount they had used prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act for emergency shelter and related services.

Funding for the ESG Program

Until enactment of P.L. 111-22, the allocation of funds for ESG had not exceeded $160 million in all the years of the program's existence. The HEARTH Act provided that 20% of funds made available by Congress for the Homeless Assistance Grants would go to the newly named program (traditionally, HUD had reserved somewhere between 10% and 15% of funds for the ESG program). However, in appropriations laws since enactment of the HEARTH Act, Congress has not required HUD to allocate 20% of funds to ESG, and has instead specified a dollar amount for ESG, which has ranged from $215 million to $286 million.37 The percentage of funds that recipients can use for administrative costs also changed pursuant to the HEARTH Act. Prior to its enactment, recipients could use up to 5% of their grants for administrative costs. This was raised to 7.5% by the HEARTH Act.38

Distribution of ESG Funds

ESG funds are distributed to both local communities (called "entitlement areas" and defined as metropolitan cities and urban counties)39 and states (called "non-entitlement areas") for distribution in communities that do not receive funds directly, through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program formula.40 Puerto Rico is considered a state and its cities are entitlement areas under the CDBG formula, and the District of Columbia is also an entitlement area. The four territories of Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa also receive ESG funds. The interim regulations governing ESG changed the allocations to these four territories, however. Previously, regulations provided that the four territories receive 0.2% of total funds, but the interim regulations provide that the territories receive "up to 0.2 percent, but not less than 0.1 percent" of the ESG allocation.41 Funds are then distributed among the four territories based on population.42 Tribes do not receive funds through ESG; instead, funds for homeless assistance are distributed through the Indian Community Development Block Grant.43

The CDBG program formula is meant to distribute funds based on a community's need for development; the ESG program has used the CDBG formula to target funds for homeless assistance since its inception, and the HEARTH Act did not alter this part of the law. The formula awards funds to metropolitan cities and urban counties (70% of funds) and to the states for use in areas that do not receive funds directly (30% of funds).44

As a condition for receiving ESG funds, states and communities must present HUD with a consolidated plan explaining how they will address community development needs within their jurisdictions. The consolidated plan is required in order for communities to participate in four different HUD grant programs, including ESG.45 The plan is a community's description of how it hopes to integrate decent housing, community needs, and economic needs of low- and moderate-income residents over a three- to five-year time span.46 Consolidated plans are intended to be collaborative efforts of local government officials, representatives of for-profit and non-profit organizations, and community members. HUD may disapprove a community's consolidated plan with respect to one or more programs, although communities have 45 days to change their plans to satisfy HUD's requirements.47 If HUD disapproves the ESG portion of the plan, the applicant community will not receive ESG funds.

If HUD approves a community's consolidated plan, the community will receive ESG funds based on its share of CDBG funds from the previous fiscal year. However, the community must have received at least 0.05% of the total CDBG allocation in order to qualify to receive ESG funds.48 In cases where a community would receive less than 0.05% of the total ESG allocation, its share of funds goes to the state to be used in areas that do not receive their own ESG funds.49 In FY2016, more than 360 states, cities, counties, and territories received ESG funds.50

After the recipient states and entitlement communities receive their ESG funds, they distribute them to local government entities, nonprofit organizations, public housing authorities, and local redevelopment authorities that provide services to homeless persons.51 These recipient organizations have been previously determined by the state or local government through an application process in which organizations submit proposals—HUD is not involved in this process. Each recipient organization must match the federal ESG funds dollar for dollar.52 States need not match the first $100,000 that they receive, and the match does not apply to the territories.53 The match may include funding from other federal sources and be met through the value of donated buildings, the lease value of buildings, salary paid to staff, and volunteer time.54

Transition to the Continuum of Care Program

The bulk of the funding for the Homeless Assistance Grants is awarded as competitive grants through what is now the CoC program.55 The CoC program differs from ESG in that it focuses on the longer-term housing and services needs of homeless individuals and families. For the 20 years prior to creation of the CoC program, there were three separate competitive grants, each of which provided different services to different populations. Enactment of the HEARTH Act brought each of the three programs' functions under the umbrella of the CoC program. The programs were

- The Supportive Housing Program (SHP): The SHP provided funds for transitional housing for homeless individuals and families for up to 24 months, permanent housing for homeless individuals with disabilities, and supportive services. Eligible recipients were states, local government entities, Public Housing Authorities (PHAs), private nonprofit organizations, and community mental health centers. Grantees were required to meet different match requirements: acquisition, rehabilitation, or new construction with an equal amount of the grant recipient's own funds, supportive services with a 20% match, and operating expenses with a 25% match.

- The Single Room Occupancy Program (SRO): The Single Room Occupancy (SRO) program provided permanent housing to homeless individuals in efficiency units similar to dormitories, with single bedrooms, community bathrooms, and kitchen facilities. The SRO program did not require residents to have a disability and did not fund supportive services. Eligible recipients were PHAs and private nonprofit organizations. The program did not have a match requirement.

- The Shelter Plus Care (S+C) Program: The S+C program provided permanent supportive housing through rent subsidies for homeless individuals with disabilities and their families. The S+C rent subsidies could be tenant-based vouchers, project-based rental assistance, sponsor-based rental assistance, or single room occupancy housing. Eligible recipients were states, local government entities, and PHAs. The S+C program required grant recipients to match the amount of grant funds they received for rental assistance with an equal amount of funds for supportive services.

(For a more detailed description of the three programs, see the Appendix.) Applicants no longer apply for one of the three existing grants—S+C, SHP, or SRO—based on the type of housing and services they want to provide. Instead, the new consolidated grant provides funds for all permanent housing, transitional housing, supportive services, and rehousing activities.

The Continuum of Care and Collaborative Applicants

The terminology surrounding the Continuum of Care program can be confusing. For years the term "Continuum of Care" has been used to describe three different things: (1) the way in which communities plan their response to the needs of homeless persons, (2) the local communities themselves (typically cities, counties, and combinations of both) that collaborate to arrive at a plan to address homelessness and apply to HUD for funds, and (3) the HUD process through which service providers apply for HUD funds.56 With the advent of the HEARTH Act, the term "Continuum of Care" is also used to refer to the main program through which HUD funds homeless services providers.

Through the CoC strategy, which remains largely the same under the HEARTH Act, local communities establish CoC advisory boards made up of representatives from local government agencies, service providers, community members, and formerly homeless individuals who meet to establish local priorities and strategies to address homelessness in their communities. The CoC plan that results from this process is meant to contain elements that address the continuum of needs of homeless persons: prevention of homelessness, emergency shelter, transitional housing, permanent housing, and supportive services provided at all stages of housing.57 The CoC system was created in 1993 as the Innovative Homeless Initiatives Demonstration Program, a grant program that provided funding to communities so that they could become more cohesive in their approach to serving homeless people.58 Since then, nearly every community in the country has become part of a CoC, with more than 400 CoCs, including those in the territories, covering most of the country.59

The HEARTH Act also codified the process by which the Continuum of Care body established at the community level coordinates the process of applying for CoC program funds. However, the name HUD gives to the applicant for the CoC program is "Collaborative Applicant."60 The Collaborative Applicant may be any entity eligible to apply for CoC program funds, including the Continuum of Care itself. In addition, a Collaborative Applicant may choose to apply for status as a Unified Funding Agency (UFA) to apply for CoC program funds. The difference between a Collaborative Applicant and a Unified Funding Agency is that a UFA is a legal entity that has the capacity to receive CoC program funds from HUD and distribute them to each grant awardee.61

|

Status of CoC Program Regulations On July 31, 2012, HUD published interim regulations for the CoC program.62 The regulations are in effect until final regulations, taking into account public comments, are published. The comment period for the interim regulations closed on November 16, 2012.63 HUD has not yet published final regulations, and while HUD has stated that it will reopen the comment period to take account of grantee experiences in implementing the program, this has not yet happened.64 Congress, as part of the Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (P.L. 114-201), directed HUD to reopen the CoC program comment period within 30 days of the law's enactment. The law was enacted on July 29, 2016. HUD reopened the CoC program interim rule for the limited purpose of proposing a new CoC formula on July 25, 2016. |

Features of the Continuum of Care Program

The CoC program maintains many of the aspects of the prior competitive grants, but also implements new features.65 Below is a description of a number of aspects of the CoC program, and, where relevant, comparisons to the three programs that came before (SHP, S+C, and SRO).

Eligible Applicants

The entities eligible to administer most activities remain the same under the CoC program as under the three previous programs. These are states, local governments, instrumentalities of state or local governments (an entity created pursuant to state statute for a public purpose), PHAs, and nonprofit organizations.66 In the HEARTH Act, entities that may administer rental assistance were initially limited to states, units of local government (e.g., cities, towns, or counties), and PHAs. However, Congress, as part of the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (P.L. 114-94), allowed private nonprofit organizations to administer rental assistance.

Program Components and Eligible Costs

The CoC program, like those before it, consists of both program components―the types of services that grantees provide, such as permanent housing and supportive services―and the costs that CoCs incur to operate each component (e.g., entering into leases and rental assistance contracts, paying operating and administrative costs, etc.). This section discusses what CoC program grantees do, and the specific costs that go into operating each component.

Eligible Program Components

Under the CoC program, most of the program components continue to be the same as those funded under the predecessor programs. However, they are consolidated so that applicants need only apply for CoC program funds rather than one of three programs based on services provided.

- Transitional Housing: Transitional housing is housing available for up to 24 months to help homeless individuals and families transition from homelessness to permanent housing. Prior to enactment of the CoC program, transitional housing was provided through the SHP program.

- Permanent Housing: As its name indicates, the statute governing the CoC program provides that permanent housing is not time limited and may be provided with or without supportive services.67 However, HUD, when it released interim CoC program regulations, set out two types of permanent housing that grantees may provide, refining the definition.

- Permanent Supportive Housing: Pursuant to the regulations, grantees may provide permanent housing with supportive services to individuals with disabilities and families where an adult or child has a disability.68

- Rapid Rehousing: The CoC program regulations allow permanent housing assistance to be provided in the context of rapid rehousing.69 Rapid rehousing is a process targeted to assist homeless individuals and families through supportive services together with rental assistance. The hope is that, after a period of time with assistance, those experiencing homelessness will be able to maintain permanent housing on their own. Grantees may pay for short-term rental assistance (up to three months) and medium-term rental assistance (from 3 to 24 months).

- Supportive Services: The statute continues to allow the CoC program to fund an array of supportive services for homeless individuals and families.70 The statute, augmented by the interim regulations, lists a number of authorized services. The services include case management, child care, education services, employment assistance and job training, housing search, life skills training, legal services, mental health services, outpatient health services, substance abuse treatment, transportation, and payment of moving costs and utility deposits.71 Note, however, that a decreasing share of CoC program funds pays for supportive services. See Table 2.

- Homeless Management Information Systems (HMIS): Homeless Management Information Systems are databases established at the local level through which homeless service providers collect, organize, and store information about homeless clients who receive services. Prior to implementation of the HEARTH Act, communities could use SHP grants to pay for HMIS.

|

Resident Contributions Toward Housing Costs HUD's interim regulations for the CoC program (24 C.F.R. §578.77) set out requirements for resident contributions toward rent. Grant recipients that sublease housing to homeless residents may charge residents for their occupancy, though they do not have to. If an occupancy charge is imposed, then it cannot exceed the greater of 30% of adjusted income, 10% of gross income, or, if a family receives welfare benefits, the portion of the benefit designated for housing costs. Residents that receive rental assistance (rather than live in leased housing) must pay rent based on 30% of adjusted income, 10% of gross income, or welfare rent. For more information about how HUD determines income and rent payments, see CRS Report R42734, Income Eligibility and Rent in HUD Rental Assistance Programs: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

Eligible Costs

In the three predecessor programs to the CoC program, the methods through which grantees provided housing and services to homeless individuals (e.g., through rental assistance, construction of housing, etc.) varied based on the particular program. In the CoC program, the relevant ways of providing assistance remain the same, but there is not the same limitation based on program type.

- Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Construction: CoC program funds can be used to acquire and/or rehabilitate property to be used for housing or supportive services for homeless individuals.72 Funds can be used for construction of housing for those who are homeless (but not for a facility that would only provide supportive services).73 These were eligible uses of funds under SHP.

- Leasing: Funds can be used to lease property in which housing and/or supportive services are made available to homeless individuals and families.74 Grant recipients must enter into occupancy agreements or subleases with program participants, and they may impose an occupancy charge.75 As in the SHP program, leases for housing may be for transitional or permanent housing.

- Rental Assistance: Similar to the S+C program, the HEARTH Act provides that grantees may use CoC funds for tenant-based rental assistance, project-based rental assistance, and sponsor-based rental assistance.76 Eligible grantees are states, units of local government, Public Housing Authorities, and private nonprofit organizations.77 With tenant-based vouchers, residents find private market housing much as they would with a Section 8 voucher; project-based assistance is provided to building owners and attached to specific units of housing (unlike a portable voucher); with sponsor-based assistance, grant recipients contract with private nonprofit housing providers or community mental health centers to provide housing. Unlike S+C, however, tenant-based rental assistance may be provided for a limited duration as rapid rehousing.78 It can be short term (up to 3 months) or medium term (between 3 and 24 months).79 Rental assistance may also be used for permanent housing without a time limit. Residents must pay a portion of rent in accordance with HUD rules.80

- Personnel Costs of Supportive Services: Grantees that provide supportive services themselves (versus contracting with outside service providers) may use CoC program funds to pay the salaries and benefits costs of staff who provide services.81

- Operating Costs: Grantees may use operating funds for transitional housing, permanent housing,82 and facilities that provide supportive services.83 Costs may include maintenance, taxes and insurance, reserves for replacement of major systems, security, utilities, furniture, and equipment. Funds may not be used for operating costs in cases where a property already receives rental assistance.84

- Administrative Costs: The percentage of funds that may be used for administrative costs increased for the CoC program compared to the three predecessor programs.

- Individual grantees may use up to 10% of their grants for administrative expenses.85 Administrative expenses include administrative staff salaries (as outlined in the regulations), administrative supplies, and Continuum of Care training, among other things.86 Prior to enactment of the CoC program, SHP grant recipients could use 5% of funds for administrative purposes, and S+C recipients could use 8% of funds.87

- Collaborative Applicants may use up to 3% of CoC funds for administrative expenses related to the application process for HUD funds.88

- Collaborative Applicants that have the status of Unified Funding Agencies, and are able to receive and distribute the CoC program funds awarded to the Continuum of Care, may use an additional 3% of funds for fund distribution, ensuring that grant recipients develop fiscal control and accounting procedures, and arranging for annual audits or evaluations of each project.89

Incentives and Bonuses

The HEARTH Act expanded the way in which competitive grant funds can be used by giving more flexibility to communities that are successful in reducing homelessness.

High-Performing Communities: The HEARTH Act instituted a new program to allow certain high-performing communities to have greater flexibility in the way that they use their funds.90 A Collaborative Applicant will be designated high-performing if the Continuum of Care it represents meets all requirements regarding91

- 1. the average length of homelessness in their communities (fewer than 20 days or a reduction of 10% from preceding year),

- 2. repeat instances of homelessness (less than 5% of those who leave homelessness become homeless again in the next two years or a 20% reduction in repeat episodes),

- 3. submission of data (80% of housing and service providers submit data to Homeless Management Information Systems),

- 4. outcomes among homeless families and youth defined as homeless under other federal programs (95% do not become homeless again within a two-year period and 85% achieve independent living in permanent housing),

- 5. comprehensive outreach plans (all communities within a CoC have an outreach plan), and

- 6. success in preventing homelessness for communities previously designated high-performing.

Collaborative Applicants designated high-performing will be able to use their grant awards for any eligible activity under the CoC program as well as for rental assistance or rapid rehousing to assist those at risk of homelessness.92

Incentives for Proven Strategies to Reduce Homelessness: Continuums of Care are to ensure that certain percentages of funds are used to provide permanent supportive housing for those experiencing chronic homelessness, as well as homeless families with children. The HEARTH Act provides that the HUD Secretary "shall provide bonuses and other incentives" to Continuums of Care that are successful in reducing or eliminating homelessness in general or among certain subpopulations through permanent housing, are successful at preventing homelessness, or that are successful at achieving independent living for families with children or youth defined as homeless under other federal statutes.93

The Grant Application Process

In consolidating the competitive grants, the HEARTH Act maintained many aspects of the current Continuum of Care application system and codified the system in law. Previously, much of the application system had been established through the grant funding process. HUD reviews one application for CoC program funds submitted by Collaborative Applicants. HUD continues to use its current practice of distributing funds directly to individual project applicants unless a Collaborative Applicant has the status of Unified Funding Agency.

Formula

Leading up to enactment of the HEARTH Act, HUD used the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program formula as a way to measure community need for competitive homeless assistance funds. (For more information, see "The Role of the Community Development Block Grant Formula.") The HEARTH Act required HUD to develop a formula for determining need within two years of the bill's enactment using "factors that are appropriate to allocate funds to meet the goals and objectives of 'the Continuum of Care program.'"94 P.L. 111-22 gave the HUD Secretary the authority to adjust the formula to ensure that Collaborative Applicants have sufficient funds to renew existing contracts for one year. When HUD released interim CoC program regulations, it continued to use the CDBG formula as the method for determining a CoC's level of need. However, in July 2016, HUD released a proposal to change the CoC formula so that the CDBG formula is no longer used. A later section in this report, "HUD Determination of Community Need," goes into more detail about the interaction of the CDBG formula and community need as well as HUD's proposal to change the formula.

Matching Requirement

Prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, matching requirements were fulfilled at the individual grant level depending on both the type of grant (SHP, S+C, or SRO) as well as, in the case of SHP, which activities grantees participated in. The CoC program has a unified match requirement where each recipient community (vs. grantee) must match the total grant funds with 25% in funds from other sources (including other federal grants) or in-kind contributions.95 The exception is funds for leasing, which does not require a match. In cases where third-party services are used to meet the match requirement, they must be documented by a memorandum of understanding.96

Who May Be Served

The HEARTH Act expanded the way in which communities may choose to serve people who are experiencing homelessness through the CoC program. In the programs that existed prior to the HEARTH Act, most permanent housing was designated either for unaccompanied individuals, with or without disabilities, although families of an adult with a disability were eligible for housing through the S+C program. None of the three programs provided permanent housing for families with non-disabled adults. In addition, families that might have been considered homeless under other federal programs were not necessarily eligible for assistance. The HEARTH Act made changes that made more people eligible for more services.

- Homeless Adults with Disabilities and Their Families: Prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, nearly all funding for permanent housing was dedicated to persons with disabilities and, in some cases, their families. SHP served unaccompanied individuals with disabilities and the S+C program served persons with disabilities and their families. The HEARTH Act continues to require that at least 30% of amounts provided for both the ESG and CoC programs (not including those for permanent housing renewals) must be used through the CoC program to provide permanent supportive housing to individuals with disabilities or families with an adult head of household (or youth in the absence of an adult) who has a disability.97 This requirement will be reduced proportionately as communities increase permanent housing units for this population, and will end when HUD determines that a total of 150,000 permanent housing units have been provided for homeless persons with disabilities since 2001.

- Homeless Families with Children: Prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, in absence of a disability, homeless families with children did not qualify for permanent housing under the SHP, S+C, or SRO programs. Pursuant to the HEARTH Act, at least 10% of the amounts made available for both the ESG and CoC programs must be used to provide permanent housing for families with children through the CoC program.

- Families with Children and Youth Certified As Homeless Under Other Federal Programs: Up to 10% of CoC program funds can be used to serve homeless families with children and unaccompanied youth defined as homeless under other federal programs.98 If a community has a rate of homelessness less than one-tenth of 1% of the total population, then the 10% limitation does not apply. (For more information on these programs, see "Other Federal Definitions.") These groups were not previously eligible for housing or services.

- Unaccompanied Homeless Individuals Without Disabilities: Nothing in the HEARTH Act prohibits communities from serving homeless individuals who do not have disabilities. However, given the requirement that Continuums of Care use a portion of funds to serve homeless families with children and individuals with disabilities, communities may choose not to prioritize this group.

|

Program |

Supportive Housing Program |

Shelter Plus Care |

Single Room |

Continuum of Care Program |

|

Program Components |

Transitional Housing |

Transitional Housing |

||

|

Permanent Housing |

Permanent Housing |

Permanent Housing |

Permanent Housing |

|

|

Rapid Rehousing |

||||

|

Supportive Services |

Supportive Services |

|||

|

HMIS |

HMIS |

|||

|

Eligible Activities |

Acquisition, Rehabilitation, Construction |

Acquisition, Rehabilitation, Construction |

||

|

Rental Assistance |

Rental Assistance |

Rental Assistance |

||

|

Leasing |

Leasing |

|||

|

Operating Costs |

Operating Costs |

|||

|

Administrative Costs |

Administrative Costs |

Administrative Costs |

||

|

Eligible Applicants |

State Government |

State Government |

State Government |

|

|

Local Government |

Local Government |

Local Government |

||

|

Instrumentalities of State and Local Governments |

||||

|

PHAs |

PHAs |

PHAs |

PHAs |

|

|

Private Nonprofits |

Private Nonprofits |

Private Nonprofits |

||

|

Community Mental Health Centers |

||||

|

Eligible Populations |

Unaccompanied individuals (transitional housing and services only) |

Unaccompanied individuals |

Unaccompanied individuals |

|

|

Unaccompanied individuals with disabilities |

Unaccompanied individuals with disabilities |

|||

|

Individuals with disabilities and their families (transitional housing and services only) |

Individuals with disabilities and their families |

Individuals with disabilities and their families |

||

|

Families with children (transitional housing and services only) |

Families with children |

|||

|

Families with children and youth defined as homeless under other federal programs (generally limited to 10% of CoC funds) |

||||

|

Match Requirements |

Dollar for Dollar (acquisition, rehabilitation, or construction) |

Equal amount of funds for services |

No match requirement |

Match of 25% at the CoC level |

|

20% (services) |

||||

|

25% (operating expenses) |

Source: The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, Title IV, Subtitles C, E, and F, both prior to and after enactment of the HEARTH Act.

Distribution of Continuum of Care Program Funds

The way in which HUD awards CoC program grants did not change significantly with enactment of the HEARTH Act, and, in fact, the HEARTH Act served, in part, to codify the way in which the funds are distributed.

The CoC program funds, like those for the three competitive grants before it, are distributed to eligible applicant organizations through a process that involves both formula and competitive elements. HUD first uses the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program formula to determine the need levels of Continuums of Care; the need level sets a baseline for the amount of funding that a community can receive. HUD then determines through a competition whether applicant organizations that provide services to homeless persons qualify for funds.

HUD Determination of Community Need

Even prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act, HUD determined community need for homeless services as a way of allocating funds. The CoC program continues this process.99 HUD goes through a process where it calculates each community's "pro rata need." Pro rata need is meant to represent the dollar amount that each community (city, county, or combination of both) needs in order to address homelessness. There are several steps in the need-determination process.

Preliminary Pro Rata Need (PPRN): Pursuant to its interim regulations, HUD uses the CDBG formula to determine a Continuum of Care's "preliminary pro rata need" as a starting point for its need for homeless services.100 This is the percentage of funds a community received (or would receive if they do not qualify for CDBG grants) from the CDBG formula multiplied by the amount of funds available to the CoC program. HUD adds together the PPRN amount for each community in a Continuum of Care to arrive at PPRN for the entire Continuum.

Annual Renewal Demand (ARD): Next, PPRN may be adjusted by a Continuum of Care's "annual renewal demand" (i.e., the amount of funds needed to renew existing contracts that are up for renewal in a given fiscal year).

Final Pro Rata Need (FPRN): This is the higher of PPRN or ARD.

Maximum Award Amount: Although FPRN is technically the maximum for which a Continuum of Care may qualify, a Continuum of Care may qualify for more than the FPRN level based on changes to fair market rents, planning costs of the Collaborative Applicant or Unified Funding Agency, and any bonus funding that might be available.

Competitive Process

Continuums of Care do not automatically qualify for their maximum award amount. The CoC program competition determines total funding levels. The competition consists of threshold review of both new and renewal grants, and a competitive process where points are awarded to applicants for new grants.

Threshold Requirements: For existing projects, there is a renewal threshold in order to qualify to have contracts renewed. This primarily involves the organization's performance in administering its grant in prior years. For new projects, HUD ensures that every participant in the proposed projects (from applicant organizations to clients who will be served) is eligible for the CoC program, that the project quality fulfills HUD requirements, and that proposed projects meet civil rights and fair housing standards.

Competition for Funds: Collaborative Applicants are also scored based on criteria established by the HEARTH Act.101 Most of these criteria had been used as part of the Continuum of Care competition established by HUD prior to enactment of the HEARTH Act and were made part of the law. The criteria include

- the Continuum of Care's performance (including outcomes for homeless clients and reducing homelessness);

- the Continuum of Care's planning process to address homelessness in its community (including how it will address homelessness among various subpopulations);

- how the Continuum of Care determined funding priorities;

- the amount leveraged from other funding sources (including mainstream programs);

- coordination of the Continuum of Care with other entities serving those who are homeless and at risk of homelessness in the planning process; and

- for those Continuums of Care serving families with children and youth defined as homeless under other federal programs, their success in preventing homelessness and achieving independent living.

To these factors, HUD has added via regulation the extent to which a Continuum of Care has a functioning Homeless Management Information System and whether it conducts an annual point-in-time count of those experiencing homelessness.

The competitive process also allows Continuums of Care to reallocate funds from an existing project to a new one if they decide that a new project would be more beneficial than an existing one. Continuums of Care that score enough points may receive funding for new projects whose costs are within the amount made available in the competition.

Features of the FY2017 Competitive Process

The specific scoring of the competition for the CoC program may differ from year to year based on available appropriations and HUD priorities. In addition, HUD may also change the ways in which CoCs can use funds for new and reallocated projects.

In FY2017, approximately $2 billion is available for the CoC program.102 Because HUD is unsure if the amount is sufficient to renew existing grants, it continues to use a tiered scoring process that was introduced in the FY2012 competition.103 HUD employs a two-tiered funding approach whereby Collaborative Applicants are to prioritize and rank projects in a way to ensure funding for their most important projects.

In the FY2017 competition for funds, the tiered funding process works as follows:

- Tier 1: The amount available to CoCs within tier 1 is the higher of (1) the amount needed to renew all permanent housing (including rapid rehousing) and HMIS projects or (2) 94% of ARD.104

- Tier 2: Projects that cannot be funded in tier 1 are to be ranked within tier 2. The amount potentially available is the remainder of a CoC's ARD plus an amount for a permanent housing bonus.105

Projects in tier 1 must pass threshold review and are scored on a 200-point scale using factors like those described in the previous, "Competitive Process," section of this report.106 Tier 2 projects are scored on a 100-point scale, with 50 points based on the CoC application score, 40 points based on the way in which CoCs rank their projects (with higher-ranked projects receiving higher scores), and 10 points for a project's commitment either to housing first (if it is permanent housing) or to low-barrier housing and attaining permanent housing (if it is not permanent housing).107 Unlike previous years, HUD is not awarding points based on type of housing (e.g., permanent supportive housing, rapid rehousing, transitional housing).

Funds in the CoC competition are largely used to renew existing grants, but Continuums of Care may also create new projects by reallocating funds from existing projects, and, depending on available resources, may compete for funding for new projects. In FY2017, HUD is allowing applicants to apply for new projects at up to 6% of FPRN (though funding for new projects is not guaranteed).108

HUD limits the ways in which new and reallocated projects can address homelessness. Both new and reallocated projects can provide the following enumerated types of housing to serve specific populations.109 In addition, reallocated funds can be used for new HMIS and coordinated assessment systems.

- Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) projects: new and reallocated funds can be targeted to projects

- serving chronically homeless individuals and families, or

- serving individuals with a disability or families with an adult or child who has a disability who also meet certain criteria established by HUD. In previous years, PSH had to be targeted to individuals and families experiencing chronic homelessness. Chronic homelessness requires that an adult have a disability and that the length of homelessness extends for 12 consecutive months, or for a total of at least 12 months on four or more occasions over the course of three years. In the FY2017 competition, HUD has expanded the circumstances in which individuals and families with disabilities may qualify for PSH. HUD refers to this housing as "DedicatedPLUS." For example, individuals and families residing in transitional housing may qualify for PSH if they had previously been considered chronically homeless, or individuals and families who have experienced homelessness for at least 12 months over the last three years, but not on four separate occasions (as is required by the definition of chronic homelessness). In addition, veterans receiving assistance through VA homeless programs who otherwise meet homeless status criteria qualify for DedicatedPLUS housing.

- Rapid Rehousing (RR) projects: new and reallocated funds can be used for rapid rehousing projects serving homeless individuals and families, including unaccompanied youth.

- Joint Transitional Housing (TH) and RR projects: new and reallocated funds can be used for joint TH-RR projects serving homeless individuals and families. FY2017 is the first year that HUD has allowed funds to be used for this joint project model where funds can be used for both types of housing. Joint TH-RR projects are expected to focus on residents obtaining and retaining permanent housing.110

- Expansion of Existing Projects: new and reallocated funds can be used to increase units in an existing project and/or increase the number of people served.111

FY2017 applications are due to HUD on September 28, 2017.112

Features of the FY2016 Competitive Process

In FY2016, the tiered funding process worked as follows:113

- Tier 1: The amount available to CoCs within tier 1 was 93% of ARD.114

- Tier 2: Projects that could not be funded in tier 1 were to be placed in tier 2. The amount available in tier 2 was the remainder of a CoC's ARD plus 5% of FPRN for a permanent housing bonus.115

Projects proposed for funding in tier 1 had to pass threshold review, and were scored based on the criteria listed in the previous section describing the competitive process. A CoC could place a tier 1 project partially in tier 1, but if it did not receive tier 2 funding, then HUD was to determine if the project was still feasible with partial funding.

Tier 2 projects were scored on a 100 point scale. Up to 50 points were available based on the CoC competition score used to score tier 1 projects. Up to 35 points were available based on the way in which CoCs ranked their projects. The more highly ranked a project, the more points it received. Up to five points were available based on the project type, with permanent supportive housing, rapid rehousing, safe havens, coordinated assessment, and transitional housing for homeless youth eligible for all five points. Finally, up to 10 points were available for the extent to which projects apply housing first and low barrier to assistance housing principals.

Given this system, the ability of projects to be funded depended on several factors:

- The tier within which a Continuum of Care ranked a project.

- The number of points scored by an applicant in the Continuum of Care program competition.

- The order within which projects were ranked in tier 2, and the type of project; the higher the ranking, the greater the number of points available. In addition, renewal transitional housing and supportive services only projects were at a slight disadvantage, with only three and one point available based on project type compared to other projects, which receive five points.

HUD announced tier 1 and tier 2 funding awards together on December 20, 2016.116 A total of $1.95 billion was distributed to more than 7,600 providers across the states and territories. Of this amount, $139 million funded new projects, and $103 million was reallocated from existing to new projects.117 For a breakdown of awards among housing types and between new and existing projects, see Table 2.

|

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

||||||

|

Award Type |

$ in |

% of Total |

$ in |

% of Total |

$ in |

% of Total |

$ in |

% of Total |

$ in |

% of Total |

|

Renewal Project Awards |

$1,614,540 |

96.5% |

$1,595,236 |

93.7% |

$1,692,093 |

93.5% |

$1,646,340 |

84.7% |

$1,763,357 |

90.1% |

|

Permanent Supportive Housing |

993,844 |

59.4 |

1,063,148 |

62.4 |

1,169,101 |

64.6 |

1,273,492 |

65.5 |

1,361,019 |

69.5 |

|

Rapid Rehousing |

6,275 |

0.4 |

8,997 |

0.5 |

67,957 |

3.8 |

105,897 |

5.4 |

196,113 |

10.0 |

|

Transitional Housing |

417,158 |

24.9 |

371,494 |

21.8 |

325,548 |

18.0 |

172,253 |

8.9 |

108,067 |

5.5 |

|

Supportive Services Only |

123,269 |

7.4 |

80,090 |

4.7 |

59,191 |

3.3 |

29,647 |

1.5 |

35,417 |

1.8 |

|

Safe Havens |

33,159 |

2.0 |

29,418 |

1.7 |

26,648 |

1.5 |

23,780 |

1.2 |

17,579 |

0.9 |

|

HMIS |

40,834 |

2.4 |

42,090 |

2.5 |

43,648 |

2.4 |

41,270 |

2.1 |

45,160 |

2.3 |

|

New Project Awards |

$46,683 |

2.8% |

$96,843 |

5.7% |

$102,127 |

5.6% |

$248,819 |

12.8% |

$141,959 |

7.3% |

|

Permanent Supportive Housing |

33,656 |

2.0 |

69,477 |

4.1 |

71,336 |

3.9 |

133,529 |

6.9 |

73,252 |

3.7 |

|

Rapid Rehousing |

6,958 |

0.4 |

27,367 |

1.6 |

30,791 |

1.7 |

92,482 |

4.8 |

53,630 |

2.7 |

|

Transitional Housing |

299 |

0.0 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Supportive Services Only |

3,429 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

18,785a |

1.0 |

11,649 |

0.6 |

|

HMIS |

2,341 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

4,044 |

0.2 |

3,428 |

0.2 |

|

Administrative Costs |

$12,025 |

0.7% |

$10,705 |

0.6% |

$16,339 |

0.9% |

$48,158 |

2.5% |

$52,122 |

2.7 |

|

CoC Planning Costs |

12,025 |

0.7 |

10,670 |

0.6 |

16,258 |

0.9 |

47,554 |

2.4 |

51,426 |

2.6 |

|

Unified Funding Agency Costs |

— |

— |

35 |

<1 |

82 |

<1 |

604 |

<1 |

696 |

<1 |

|

Total |

$1,673,248 |

$1,702,784 |

$1,810,560 |

$1,943,317 |

$1,957,438 |

|||||

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2012-2016 CoC Awards by Program Component, All States, Territories, Puerto Rico, and DC, available at https://www.hudexchange.info/coc/awards-by-component/.

Note: Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. New projects include those created by reallocating funds for existing projects.

a. In the FY2015 and FY2016 competitions, new Supportive Services Only funds could be used for a centralized or coordinated assessment system within a Continuum of Care. Funds could not be used for new projects to provide services to people experiencing homelessness.

Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program

In the area of rural homelessness, the HEARTH Act retained portions of McKinney-Vento's rural homelessness grant program (Title IV, Subtitle G of McKinney-Vento, a program that was never implemented or funded after it was authorized as part of P.L. 102-550) as the Rural Housing Stability Assistance Program. The grants themselves are referred to as the Rural Housing Stability (RHS) grants. As of the date of this report, HUD had released proposed regulations, but had not yet made funds available through the RHS grants.

The program allows rural communities to apply separately for funds that otherwise would be awarded as part of the Continuum of Care program. The HEARTH Act provides that not less than 5% of Continuum of Care Program funds be set aside for rural communities.118 If the funds are not used, then they are to be returned for use by the CoC program.

What Is a Rural Community?

The law defines a rural community as falling into one of three different categories,119 which HUD further refined in its proposed regulation.120 Under the statute and regulations, a rural community is

- a county where no part is contained within a metropolitan statistical area,

- a county located within a metropolitan statistical area, but where at least 75% of the county population is in nonurban Census blocks, or

- a county located in a state where the population density is less than 30 people per square mile, and at least 1.25% of the acreage in the state is under federal jurisdiction. However, under this definition, no metropolitan city in the state (as defined by the CDBG statute) can be the sole beneficiary of the RHS grants.

Eligible Applicants

The entities eligible to apply for and receive RHS program grants are county and local governments and private nonprofit organizations.121 A county that meets the definition of rural community may either submit an application to HUD or designate another eligible entity to do so. Once a grant is awarded, the county or its designee may award grants to subrecipients.

Who May Be Served

Unlike the CoC program, communities that participate in the RHS program are able to serve persons who do not necessarily meet HUD's definition of "homeless individual." HUD may award grants to rural communities to be used for the following: