Executive Branch Service and the “Revolving Door” in Cabinet Departments: Background and Issues for Congress

Individuals may be subject to certain restrictions when leaving the government for private employment or joining the government from the private sector. These restrictions were enacted in response to what is often referred to as the revolving door. Generally, the revolving door is described as the movement of individuals between the public and private sector. Individuals may move because they possess policy and procedural knowledge and have relationships with former colleagues that are useful to prospective employers.

Laws attempting to restrict the movement of individuals between the government and the private sector have existed since at least the late 1800s. Today’s revolving door laws focus on restricting former government employees’ representational activities that attempt to influence federal officials with whom they used to work. Found at 18 U.S.C. §207, revolving door laws for executive branch officials include (1) a lifetime ban on “switching sides” (e.g., representing a private party on the same “particular matter” involving identified parties on which the former executive branch employee had worked while in government); (2) a two-year ban on “switching sides” on a broader range of issues; (3) a one-year restriction on assisting others on certain trade and treaty negotiations; (4) a one-year “cooling off” period for certain senior officials on lobbying; (5) two-year “cooling off” periods for very senior officials from lobbying; and (6) a one-year ban on certain former officials from representing a foreign government or foreign political party. In addition to laws, executive orders have been used to place further restrictions on executive branch officials, including officials entering government. For example, President Trump issued an executive order (E.O. 13770) to lengthen “cooling off” periods for certain executive branch appointees both entering and exiting government.

To date, much of the empirical work concerning the revolving door has focused on former Members of Congress or congressional staff leaving Capitol Hill, especially those who become lobbyists in their postcongressional careers. This report provides some empirical data about a different aspect of the revolving door—the movement into and out of government by executive branch personnel. Using research conducted by the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University’s capstone class over the 2017-2018 academic year, this report presents data about the revolving door in the executive branch through the lens of President George W. Bush’s and President Barack Obama’s Administrations. The analysis includes Cabinet department officials who were listed, for either Administration, in the United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (the Plum Book).

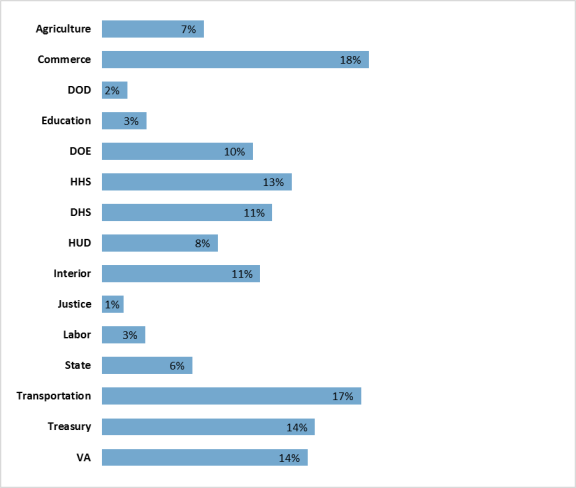

Through an examination of appointees in President Bush’s and President Obama’s Administrations, several findings emerge. First, approximately 92% of executive branch officials in the examined dataset were never registered lobbyists, while 8% were registered lobbyists at some point before or after their government service. Second, Cabinet departments differed greatly in the number of officials who were registered lobbyists either before or after their federal service. Although every Cabinet department surveyed had some percentage of officials registered as lobbyists either before or after their government service, the percentage of officials included in the dataset who registered as lobbyists before their government service, after their government service, or both ranged from a high of 18% (Department of Commerce) to a low of 1% (Department of Justice).

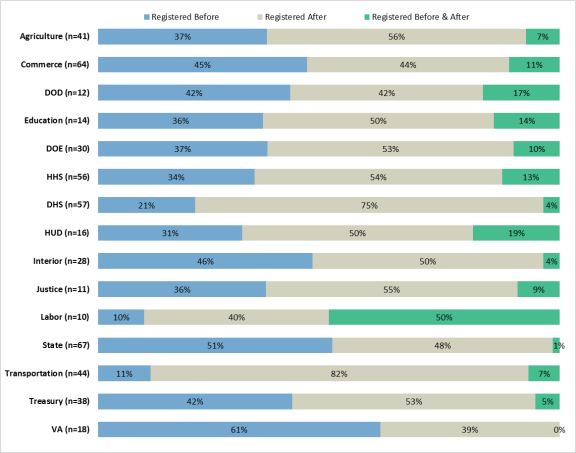

Third, the data also show that for lobbyists entering government, the percentage of officials in the dataset who had been lobbyists before government serving in the Bush and Obama Administrations ranged from 10% in the Department of Labor to 61% in the Department of Veterans Affairs. The analogous percentages for government employees in the dataset leaving to become lobbyists ranged from 39% in the Department of Veterans Affairs to 82% in the Department of Transportation.

Finally, the report identifies several areas for potential congressional consideration. In recent years, several bills have been introduced in Congress to address many of these potential areas. These include options to amend existing “cooling off” periods and evaluate the administration and enforcement of revolving door regulations. Alternatively, Congress may choose to maintain current “cooling off” periods, administration, and enforcement practices.

Executive Branch Service and the "Revolving Door" in Cabinet Departments: Background and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- The Revolving Door in the Executive Branch

- Existing Revolving Door Laws and Executive Orders

- Postemployment Laws

- Supplemental Regulations

- Executive Order Ethics Pledges

- Revolving Door: Advantages and Disadvantages

- Research Design and Methodology

- Revolving Door Lobbyists in the Executive Branch

- Overall Patterns

- Department Trends

- Conclusions and Selected Considerations for Congress

- Amending "Cooling Off" Periods

- Administration of the Revolving Door

- Maintain Current Revolving Door Standards

Figures

Summary

Individuals may be subject to certain restrictions when leaving the government for private employment or joining the government from the private sector. These restrictions were enacted in response to what is often referred to as the revolving door. Generally, the revolving door is described as the movement of individuals between the public and private sector. Individuals may move because they possess policy and procedural knowledge and have relationships with former colleagues that are useful to prospective employers.

Laws attempting to restrict the movement of individuals between the government and the private sector have existed since at least the late 1800s. Today's revolving door laws focus on restricting former government employees' representational activities that attempt to influence federal officials with whom they used to work. Found at 18 U.S.C. §207, revolving door laws for executive branch officials include (1) a lifetime ban on "switching sides" (e.g., representing a private party on the same "particular matter" involving identified parties on which the former executive branch employee had worked while in government); (2) a two-year ban on "switching sides" on a broader range of issues; (3) a one-year restriction on assisting others on certain trade and treaty negotiations; (4) a one-year "cooling off" period for certain senior officials on lobbying; (5) two-year "cooling off" periods for very senior officials from lobbying; and (6) a one-year ban on certain former officials from representing a foreign government or foreign political party. In addition to laws, executive orders have been used to place further restrictions on executive branch officials, including officials entering government. For example, President Trump issued an executive order (E.O. 13770) to lengthen "cooling off" periods for certain executive branch appointees both entering and exiting government.

To date, much of the empirical work concerning the revolving door has focused on former Members of Congress or congressional staff leaving Capitol Hill, especially those who become lobbyists in their postcongressional careers. This report provides some empirical data about a different aspect of the revolving door—the movement into and out of government by executive branch personnel. Using research conducted by the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University's capstone class over the 2017-2018 academic year, this report presents data about the revolving door in the executive branch through the lens of President George W. Bush's and President Barack Obama's Administrations. The analysis includes Cabinet department officials who were listed, for either Administration, in the United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (the Plum Book).

Through an examination of appointees in President Bush's and President Obama's Administrations, several findings emerge. First, approximately 92% of executive branch officials in the examined dataset were never registered lobbyists, while 8% were registered lobbyists at some point before or after their government service. Second, Cabinet departments differed greatly in the number of officials who were registered lobbyists either before or after their federal service. Although every Cabinet department surveyed had some percentage of officials registered as lobbyists either before or after their government service, the percentage of officials included in the dataset who registered as lobbyists before their government service, after their government service, or both ranged from a high of 18% (Department of Commerce) to a low of 1% (Department of Justice).

Third, the data also show that for lobbyists entering government, the percentage of officials in the dataset who had been lobbyists before government serving in the Bush and Obama Administrations ranged from 10% in the Department of Labor to 61% in the Department of Veterans Affairs. The analogous percentages for government employees in the dataset leaving to become lobbyists ranged from 39% in the Department of Veterans Affairs to 82% in the Department of Transportation.

Finally, the report identifies several areas for potential congressional consideration. In recent years, several bills have been introduced in Congress to address many of these potential areas. These include options to amend existing "cooling off" periods and evaluate the administration and enforcement of revolving door regulations. Alternatively, Congress may choose to maintain current "cooling off" periods, administration, and enforcement practices.

Introduction

In 1883, following the assassination of President James A. Garfield by disgruntled job seeker Charles Guiteau,1 the Pendleton Act was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur to ensure that "government jobs be awarded on the basis of merit…."2 The Pendleton Act ended the spoils system to ensure that qualified individuals were hired into federal service and to prevent the President from being "hounded by job seekers."3 With the advent of the merit system, federal employees found themselves serving longer in government while also being attracted to private-sector jobs related to their federal employment.4 The movement of employees between the private sector and government is often referred to as the revolving door.

Generally, the revolving door is described as the movement of individuals between the public and private sector, and vice versa.5 Individuals may move because they possess policy and procedural knowledge and have relationships with former colleagues that are useful to prospective employers, either in government or in the private sector.6 Some observers see the revolving door as potentially valuable to both private-sector firms and the government; other observers believe that employees leaving government to join the industries they were regulating, or leaving the private sector to join a relevant government agency, could provide an unfair representational advantage and create the potential for conflicts of interest.7

While Congress has passed laws regulating the revolving door phenomenon in the executive branch, there has to date been little data available about the underlying phenomenon.8 This report provides data on the movement into and out of government by executive branch personnel in President George W. Bush's and President Barack Obama's Administrations. Using a dataset of executive branch Cabinet department officials compiled by graduate students at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University in partnership with CRS, this report provides empirical data about the use of the revolving door by a subset of federal officials, with a particular focus on those who were registered lobbyists either before or after their government service.

This report begins with an overview of existing revolving door laws and regulations that affect executive branch personnel. It next examines the potential advantages and disadvantages of the revolving door phenomenon. Data collected in partnership with the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University are then presented and analyzed. The data provide an empirical picture of the executive branch revolving door as it relates to registered lobbyists. This analysis is followed by a discussion of select issues for potential congressional consideration.

The Revolving Door in the Executive Branch

Revolving door provisions, which can include laws, regulations, and executive orders, are often considered as a subset of conflict-of-interest provisions that govern the interaction of government and nongovernmental individuals.9 While most historic revolving door provisions generally addressed individuals exiting government for work in the private sector, some have also addressed individuals entering government. Overall, revolving door conflict-of-interest laws have existed since the late 19th century. The first identified conflict-of-interest provision was enacted in 1872.10 This provision generally prohibited a federal employee from dealing with matters in which they were involved prior to government service. In 1919, the first restrictions were placed on individuals who had specifically served as procurement officials from leaving government service "to solicit employment in the presentation or to aid or assist for compensation in the prosecution of claims against the United States arising out of any contracts or agreements for the procurement of supplies … which were pending or entered into while the said officer or employee was associated therewith."11 Similarly, the Contract Settlement Act of 1944 (58 Stat. 649) included a provision making it

Unlawful for any person employed in any Government agency … during the period such person is engaged in such employment or service, to prosecute or to act as counsel attorney or agent for prosecuting, any claim against the United States, or for any such person within two years after the time when such employment or serve has ceased, to prosecute, or to act as counsel, attorney, or agent for prosecuting, any claim against the United States involving any subject matter directly connected with which such person was so employed or performed duty.12

In 1962, portions of the current statutory provision at 18 U.S.C. §207 were enacted as part of a major revision of federal conflict-of-interest laws.13 Since the 1960s, postemployment restriction laws have been amended several times, including by the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 to add certain one-year "cooling off" periods for high-level executive branch personnel and limit executive branch official postemployment advocacy (i.e., lobbying) activities;14 by the Ethics Reform Act of 1989;15 and by the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007, which extended the "cooling off" period to two years for "very senior" executive branch officials.16

Revolving door provisions, including conflict-of-interest laws and "cooling off" periods, were initially designed to protect government interests against former officials using proprietary information on behalf of a private party and current officials against inappropriately dealing with matters on which they were involved prior to government service.17 Additionally, they attempted to limit the possible influence and allure of potential private arrangements by federal officials when they interact with prospective private clients or would-be future employers while still employed by the government.18

Historically, the decision to adopt, or amend, revolving door and conflict-of-interest provisions has been balanced against the potential deterrent of restricting the movement of individuals between the public and private sector. For example, in 1977, the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs reported a bill that would have amended the existing revolving door provisions. As part of its justification for the measure, the committee explained the need to balance the appearance of impropriety against the need to attract skilled government workers. Its report noted the following:

18 USC §207, like other conflict of interest statutes, seeks to avoid even the appearance of public office being used for personnel or private gain. In striving for public confidence in the integrity of government, it is imperative to remember that what appears to be true is often as important as what is true. Thus government in its dealings must make every reasonable effort to avoid even the appearance of conflict of interest and favoritism.

But, as with other desirable policies, it can be pressed too far. Conflict of interest standards must be balanced with the government's objective in attracting experienced and qualified persons to public service. Both are important, and a conflicts policy cannot focus on one to the detriment of the other. There can be no doubt that overly stringent restrictions have a decidedly [sic] adverse impact on the government's ability to attract and retain able and experienced persons in federal office.19

The revolving door allows movement in both directions, with individuals both entering and exiting government. Some past researchers have argued that those who enter government with prior industry experience are more supportive of regulated industry than those without industry experience.20 Similarly, two studies have concluded that the lure of private-sector employment has led regulators to support the regulated industry during their time in government.21

Whether or not the revolving door on net helps or hinders the functioning of government agencies may depend, however, on the potential benefits of transitioning individuals between government and the private sector versus the potential for conflicts of interest to develop on the part of those individuals. Some studies have identified positive aspects of the revolving door and the relationships developed between regulators and the regulated.22 Other studies find that government agencies are better run with stable leadership that does not often utilize the revolving door and keeps some distance between the agency and the regulated industry.23

Existing Revolving Door Laws and Executive Orders

Current laws and regulations generally govern the movement of federal employees from the government to the private sector and vice versa. These provisions can be divided into three categories: broadly applicable postemployment laws, supplemental regulations, and executive order requirements. Revolving door provisions, however, do not necessarily apply to all instances of an employee leaving government service. Rather, they are specific to covered officials (see below) who leave government and are then involved with an issue they were also involved in while a federal employee. For some circumstances, the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) "has emphasized that the term [particular matter] typically involves a specific proceeding affecting the legal rights of the parties, or an isolatable transaction or related set of transactions between identified parties."24

Postemployment Laws

Initially enacted in 1962, 18 U.S.C. §207 provides a series of postemployment restrictions and was enacted "to prevent former Government employees from leveraging relationships forged during their Government service to assist others in their dealings with the Government."25 These include

- a lifetime ban on "switching sides" on a particular matter involving specific parties on which any executive branch employee had worked personally and substantially while with the government;26

- a two-year ban on "switching sides" on a somewhat broader range of matters that were under the employee's official responsibility;27

- a one-year restriction on assisting others on certain trade or treaty negotiations;28

- a one-year "cooling off" period for certain "senior" officials, barring representational communications before their former departments or agencies;29

- a two-year "cooling off" period for "very senior" officials, barring representational communications and attempts to influence certain other high-ranking officials in the entire executive branch of government;30 and

- a one-year ban on certain officials performing some representational or advisory activities for foreign governments or foreign political parties.31

Current law focuses on postemployment restrictions of former federal employees rather than on individuals entering government.32 These postemployment laws focus on "representational" activities of former federal employees and are "designed to protect against the improper use of influence and government information by former employees, as well as to limit the potential influence that a prospective employment arrangement may have on current federal officials when dealing with prospective private clients or future employers while still in government service."33 One study found the appeal of postemployment contact with the government to be strong, especially when there is a "demand for the personnel credentials" of former officials within an industry,34 and when former officials can move from a regulatory agency to the regulated industry.35

The revolving door restrictions are in addition to statutes that apply more broadly to all individuals engaged in certain representational activities, regardless of whether they ever worked for the federal government. These restrictions, found primarily in the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA), however, do not prohibit any particular behavior.36 Rather, they require registration as a foreign agent or lobbyist and the periodic disclosure of information about influence activities.37

Supplemental Regulations

Regulations for the implementation of revolving door provisions are issued by OGE. Found at 5 C.F.R. §2641, these regulations provide an overview and definitions for current revolving door, postemployment conflict-of-interest restrictions; list prohibitions covered by the regulations and the law; and provide a summary of statutory exceptions and waivers.38 The OGE regulations pertain only to postemployment restrictions found at 18 U.S.C. §207 and only to executive branch employees.39

In some cases, agencies have issued additional regulations that supplement OGE's regulations. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) provides guidance on the application of postemployment restrictions to all government employees,40 whereas the Federal Housing Finance Agency provides specific additional postemployment restrictions for its employees.41

Executive Order Ethics Pledges

In several instances, the President has issued an executive order to influence the interactions and relationships between the public and the executive branch. For example, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order (E.O. 10939) that included provisions for behavior by government employees.42 In the years after President Kennedy's Administration, other Presidents also issued ethics executive orders to address postgovernment revolving door restrictions. These executive orders were issued by President Lyndon Johnson,43 President Richard Nixon,44 President Ronald Reagan,45 and President George H. W. Bush.46

In more recent Administrations, three Presidents have each issued an executive order that included additional revolving door restrictions for certain Administration appointees. They are President Clinton (1993),47 President Obama (2009),48 and President Trump (2017).49 Each of these executive orders contained an ethics pledge that provided additional conflict-of-interest requirements for executive branch personnel leaving the government and for individuals entering government. Each also extended statutory and regulatory revolving door provisions, included additional restrictions on lobbyists entering government and lobbying back government upon departure, and in two instances (Clinton and Trump) contained restrictions on former appointees leaving the government to represent a foreign principal.

For a more detailed discussion of executive order ethics pledges, see CRS Report R44974, Ethics Pledges and Other Executive Branch Appointee Restrictions Since 1993: Historical Perspective, Current Practices, and Options for Change, by Jacob R. Straus.

Revolving Door: Advantages and Disadvantages

Discussion of whether revolving door restrictions are positive or negative generally focuses on whether former government employees, when they switch jobs, have an inherent or perceived conflict of interest. Though legislation often treats the revolving door as a negative trend, the movement of individuals between the government and private sector may also present multiple potential benefits. One argument in favor of the revolving door, for example, is that the promise of future private-sector employment could potentially improve the quality of candidates applying for government jobs.50 Further, direct connections with government officials are important, but a close relationship is not necessarily what drives postemployment activities. Although some believe that government employees contemplating a move to the private sector will be friendly to industry interests at the expense of the public interest, two studies have also concluded that regulators instead may engage in more aggressive actions, regardless of their future job prospects.51 Additionally, the flow of personnel between the public and private sectors may increase the knowledge base of both sectors.52

Critics of the revolving door and the movement of employees between the government and private sector often advocate for longer "cooling off" periods and stronger restrictions related to conflicts of interest.53 Additionally, critics often assert that the revolving door has negative effects for the transparency and efficiency of government. These critics see existing bias between those in government and their connections with lobbying firms and the potential for those connections to be exploited when the individual is employed by the private sector.54

Additional criticism of the revolving door focuses on the worth of a former government employee over time. One study has concluded that a majority of revenue generated by private lobbying firms was directly attributable to employees with previous government experience.55 Another study found that "'who you know' rather than 'what you know' drives a good proportion of lobbying revenues."56

Research Design and Methodology

In every Administration, executive branch officials arrive from, and depart to, the private sector. The movement between the government and the private sector touches on many industries and professions.57 When such movement occurs, it is possible that conflicts of interest could arise for current and former government officials.58

Data on executive branch employees entering and exiting the government have historically been difficult to compile. During the 2017-2018 academic year (September 2017 to May 2018), CRS partnered with graduate students at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University to collect and analyze data on the revolving door. Data were collected on the subset of former executive branch officials who were listed in the United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (the Plum Book).59 Published every four years, the Plum Book "lists over 7,000 Federal civil service leadership and support positions … that may be subject to noncompetitive appointment, nationwide. Data covers positions such as agency heads and their immediate subordinates, policy executives and advisors, and aides who report to these officials."60 The positions listed in the Plum Book are political appointments, which represent a subset of executive branch employees. Therefore, this report presents data on that subset of individuals who have worked in these executive branch positions. Additionally, since the Plum Book is published only once every four years, it is a "snapshot" of a given Administration's appointees and includes only individuals who were serving at the time of publication.

Four Plum Books were used to build a dataset of political appointees who served in President George W. Bush's and President Barack Obama's Administrations. Overall, 6,665 federal appointees were included spanning the two Administrations. Table 1 reports the number of appointees from each Administration included in this dataset. If an appointee served in more than one Administration, data reported are for the most recent Administration served. Appointees were not included in the dataset twice. Further, if an appointee left the Administration prior to the Plum Book's publication, then they do not appear in the data.

Table 1. Cabinet Department Political Appointees Included in the Dataset by Presidential Administration

|

Administration (Plum Book Year) |

Number of Appointees |

|

|

George W. Bush (2004) |

|

|

|

George W. Bush (2008) |

|

|

|

Barack Obama (2012) |

|

|

|

Barack Obama (2016) |

|

|

|

Total |

|

Source: Bush School of Government Service and CRS data analysis of Plum Book entries.

Political appointees included in the dataset represented 15 Cabinet departments and were paid at the GS-13 level or higher—a pay rate generally considered to have supervisory authority in the executive branch.61 Table 2 lists the Cabinet departments included in this study and the number of employees from that Cabinet department included in the dataset.

|

Cabinet Department |

Number of Officials |

|

|

Department of Agriculture |

|

|

|

Department of Commerce |

|

|

|

Department of Defense |

|

|

|

Department of Education |

|

|

|

Department of Energy |

|

|

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

|

|

Department of Homeland Security |

|

|

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

|

|

Department of the Interior |

|

|

|

Department of Justice |

|

|

|

Department of Labor |

|

|

|

Department of State |

|

|

|

Department of Transportation |

|

|

|

Department of the Treasury |

|

|

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

|

|

Total |

|

Source: Bush School of Government Service and CRS data analysis of Plum Book entries.

For most individuals and industries, data on both pregovernment and postgovernment service is not readily obtainable from public sources. Therefore, this report uses official Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) data on registered lobbyists to gain insight into the revolving door phenomenon. Administered by the Clerk of the House of Representatives and the Secretary of the Senate, LDA registration data are required by law to be published online.62 The LDA database includes all registration and disclosure statements for lobbyists and is searchable by name, lobbying firm, or lobbying client.63 Since the Plum Book provides the names of former executive branch officials, the LDA database was searched to match pregovernment and postgovernment service of individuals registered as lobbyists. Appointees were classified as lobbyists if they were registered under LDA at any time before or after their government service, regardless of the duration of their registration. These data, which reflect a subset of people who move between employment in the private sector and government in either direction, are the focus of this report's analysis.

Revolving Door Lobbyists in the Executive Branch

Overall Patterns

Of Bush and Obama Administration executive branch appointees in the dataset, approximately 92% (6,159) were never registered as lobbyists, while 8% (506) were registered either before, after, or both before and after their government service. Of those registered as lobbyists, approximately 36.5% registered before joining the government, 55.1% registered after leaving their executive branch jobs, and 8.3% registered both before and after their federal service. Overall, these numbers generally appear to be in line with other studies of the executive branch, which suggest that most high-level federal appointees were not employed as lobbyists either prior to, or after, their government service.64

Examining the number and percentage of lobbyists in the dataset by Administration (Table 3) shows that the overall levels of registered lobbyists either before or after government service is relatively low in both the Bush Administration and the Obama Administration. The Obama Administration, however, had more of its appointees who were registered lobbyists before their government service than after their government service, while the Bush Administration had more of its appointees who were registered lobbyists after their government service than before their government service.

|

Administration |

Registered Before |

Registered After |

Registered Before and After |

Never Registered |

Total in Dataset |

|

Bush 2001-2004 |

36 (2.56%) |

134 (9.53%) |

10 (0.71%) |

1,226 (87.2%) |

1,406 (18.73%) |

|

Bush 2005-2008 |

43 (2.28%) |

94 (4.98%) |

23 (1.22%) |

1,729 (91.53%) |

1,889 (25.16%) |

|

Obama 2009-2012 |

39 (2.86%) |

27 (1.98%) |

3 (0.22%) |

1,297 (94.95%) |

1,366 (18.20%) |

|

Obama 2013-2016 |

67 (3.34%) |

24 (1.20%) |

6 (0.30%) |

1,907 (95.16%) |

2,004 (26.70%) |

|

Totals |

185 (2.8%) |

279 (4.2%) |

42 (0.60%) |

6,159 (92.4%) |

6,665 (100%) |

Source: Bush School of Government Service and CRS data analysis of Plum Book entries.

Note: Percentages do not total 100% because of rounding.

As shown in Table 3, the total number of registered lobbyists in the dataset from the Bush Administration (340) was higher overall than from the Obama Administration (166), although the number of lobbyists serving in either Administration is not particularly large compared to the total number of appointees included in the dataset. During his Administration, President Obama instituted an executive order to restrict the number of lobbyists entering the Administration, a policy that did not exist in the Bush Administration.65 The number of individuals who were registered lobbyists before serving in President Obama's first term is similar to the first term of the Bush Administration.

The number of lobbyists entering government, however, was higher in President Obama's second term than in either the Bush Administration or President Obama's first term. For individuals leaving the Administration, the number of registered lobbyists is lower in the Obama Administration than in the Bush Administration.

Department Trends

In the dataset, Cabinet departments differed greatly in the number of officials who were registered lobbyists either before or after their federal service. Some departments had few individuals who were registered lobbyists either before or after their time in government, whereas others had more. Figure 1 reports the percentage of registered lobbyists by department in the dataset collected by the Bush School of Government and Public Service and CRS.

As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of federal appointees in the dataset who registered as lobbyists before their government service, after their government service, or both ranges from a high of 18% (Department of Commerce) to a low of 1% (Department of Justice). The figures for other agencies ranges between 2% and 17%.66

The overall percentages of Cabinet department officials in the dataset who have ever been registered lobbyists might raise some questions for future research on the connections between government agencies and regulated industries. For example, some agencies appear to have a higher percentage of lobbyists than other agencies. Could a high percentage of lobbyists indicate stronger links to regulated industries?67 Similarly, how might lobbyists entering government differ in their government-industry connection than lobbyists leaving government? Might maintaining government-industry connections allow for better outreach by government agencies and access to information and resources by interest groups?68

The timing of when lobbyists registered may provide additional insight into how often federal officials in the dataset utilized the revolving door between government and lobbying. Figure 2 shows the percentage of LDA-registered officials at various agencies divided by when they registered—before their service, after their service, or both.

As Figure 2 shows, every Cabinet department for which data were gathered had some number of officials listed in the Plum Book who registered as lobbyists either before or after their government service, or both. The number of officials in the dataset identified as registered lobbyists is noted on the left-hand side of Figure 2 next to the name of the federal department at which they worked. As the figure shows, each department had a different mix of the percentage of its officials in the dataset identified as registered lobbyists who registered to lobby before their government service, after their government service, or both.

The percentage of the total number of lobbyists who worked at a particular agency who were registered lobbyists before their government service ranged from 10% in the Department of Labor to 61% in the Department of Veterans Affairs. The percentage of the total number of lobbyists who worked at a particular agency who were registered lobbyists after their government service ranged from 39% in the Department of Veterans Affairs to 82% in the Department of Transportation. Additionally, all departments included in the data except the Department of Veterans Affairs had individuals who were registered lobbyists before and after their government service. For the Department of Labor, half of officials who were lobbyists registered both before and after their government service. For other agencies, the percentages ranged from 1% (Department of State) to 19% (Department of Housing and Urban Development).

Conclusions and Selected Considerations for Congress

In every Administration, individuals move between the public and private sectors. In recent years, there has been greater focus on potential additional restrictions that might be placed on individuals entering and exiting government through the introduction of legislation to amend current revolving door restrictions and the issuance of executive orders to temporarily increase the "cooling off" period for executive branch appointees.69

Current law compartmentalizes the revolving door by placing distinctive postemployment restrictions on different types of government employees.70 For example, restrictions on government officials engaged in contracting do not necessarily apply to nonprocurement or noncontracting employees.71 Such varying restrictions were enacted because "the present complexity and size of Executive departments require occasional separate treatment of certain departmental agencies and bureaus. It would be patently unfair in some cases to apply the one year no contact prohibition to certain employees for the purpose of an entire department—when, in reality, the agency in which he worked was separate and distinct from the larger entity."72

Amending "Cooling Off" Periods

In past Congresses, legislation has been introduced to lengthen revolving door "cooling off" periods.73 Those measures often propose extending "cooling off" periods to as few as two years to instituting a lifetime ban. If enacted, increased restrictions could serve to diminish the interaction between former government officials and government agencies and could reduce the appeal of leaving the government for a private-sector position. Additionally, such additional restrictions might "eliminate the appearance of favoritism a former official may have in lobbying his or her former office, and … prevent a former official from financially benefiting from the use of confidential information obtained while working for the Federal Government."74

Conversely, extending the "cooling off" period could possibly be seen as an unreasonable restriction on postemployment and "curtailing an individual's constitutional right of free association."75 Alternatively, Congress could reduce or eliminate the "cooling off" period. Having a shorter "cooling off" period, or eliminating it altogether, might arguably increase the talent pool available both inside and outside the government.

Finally, Congress could codify past executive branch ethics pledges that generally placed additional restrictions on executive branch appointees.76 Codifying ethics pledge provisions would have the effect of making those changes permanent, and not subject to being revoked by a future executive order. This could allow for permanent changes to existing ethics and conflict-of-interest provisions.77

Administration of the Revolving Door

Administration and enforcement of revolving door provisions are spread among several entities. For example, each agency is responsible for collecting financial disclosure statements from individual employees and ensuring that they comply with conflict-of-interest provisions, including revolving door restrictions.78 Potential violations of revolving door laws, however, would likely be prosecuted by the Department of Justice.79 Congress could amend current law to consolidate the administration and enforcement of conflict of interest and revolving door provisions. Consolidation could provide a single office to help ensure compliance and enforcement of existing laws. Consolidation, however, would potentially add an additional layer to the collection and evaluation documents used to identify potential conflicts-of-interest or revolving door concerns. Since each agency collects financial disclosure forms from its employees, those forms would still need to be transmitted to a central location. Ethics enforcement, including the review of financial disclosure forms for potential conflicts of interest, has historically been conducted at the agency level, as each agency is often in the best position to determine whether a real or perceived conflict exists for its employees.80

Maintain Current Revolving Door Standards

Congress might determine that current revolving door laws and regulations are effective or that the potential costs of changes outweigh potential benefits. Instead of amending existing revolving door provisions, Congress could continue to use existing law and regulations to govern the movement of individuals between the federal government and private sector. Changes to the revolving door could be made on an as-needed basis through modifications to executive branch regulations or executive orders.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information on President Garfield's assassination, see Kenneth D. Ackerman, "The Garfield Assassination Altered American History, But is Woefully Forgotten Today," Smithsonian Magazine, November 19, 2018, at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/garfield-assassination-altered-american-history-woefully-forgotten-today-180968319; and Candice Millard, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President (New York: Anchor Books, 2012). |

| 2. |

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), "Pendleton Act (1883)," Our Documents, https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=48. |

| 3. |

NARA, "Pendleton Act (1883)." |

| 4. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Post Office and Civil Service, Subcommittee on Manpower and Civil Service, History of Civil Service Merit Systems of the United States and Selected Foreign Countries, committee print, prepared by the Congressional Research Service, 94th Cong., 2nd sess., December 31, 1976, No. 94-29 (Washington: GPO, 1976), p. 32. |

| 5. |

Jordi Blanes i Vidal, Mirko Draca, and Christian Fons-Rosen, "Revolving Door Lobbyists," American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 7 (December 2012), pp. 3731-3748. |

| 6. |

Lara E. Chausow, "It's More Than Who You Know: The Role of Access, Procedural and Political Expertise, and Policy Knowledge in Revolving Door Lobbying" (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 2015). |

| 7. |

Marissa Martino Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats? Politics and Administration During the Reagan Years (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); Charles T. Goodsell, The Case for Bureaucracy: A Public Administration Polemic, 3rd ed. (New York: Chatham House, 1994); Dror Etzion and Gerald F. Davis, "Revolving Doors? A Network Analysis of Corporate Officers and U.S. Government Officials," Journal of Management Inquiry, vol. 17, no. 3 (September 2008), pp. 157-161; William T. Gormley Jr., "A Test of the Revolving Door Hypothesis at the FCC," American Journal of Political Science, vol. 23, no. 4 (November 1979), pp. 665-683; and Robert H. Mundheim, "Conflict of Interest and the Former Government Employee: Rethinking the Revolving Door," Creighton Law Review, vol. 14, no. 3 (1981), pp. 707-722. |

| 8. |

To date, much of the empirical work on the revolving door has focused on former Members of Congress or congressional staff leaving Capitol Hill, especially those who become lobbyists in their postcongressional careers. Blanes i Vidal, Draca, and Fons-Rosen, "Revolving Door Lobbyists"; Bruce E. Cain and Lee Drutman, "Congressional Staff and the Revolving Door: The Impact of Regulatory Change," Election Law Journal, vol. 13, no. 1 (March 2014), pp. 27-44; Jeffrey Lazarus, Amy McKay, and Lindsey Herbel, "Who Walks Through the Revolving Door? Examining the Lobbying Activities of Former Members of Congress," Interest Groups & Advocacy, vol. 5, no. 1 (March 2016), pp. 82-100; Todd Makse, "A Very Particular Set of Skills: Former Legislator Traits and Revolving Door Lobbying in Congress," American Politics Research, vol. 45, no. 5 (2017), pp. 866-889; and Melinda N. Ritchie and Hye Young You, "Legislators as Lobbyists," Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1 (February 2019), pp. 65-95. |

| 9. |

Mundheim, "Conflict of Interest and the Former Government Employee: Rethinking the Revolving Door"; Simon Luechinger and Christoph Moser, "The Value of the Revolving Door: Political Appointees and the Stock Market," Journal of Public Economics, vol. 119 (November 2014), pp. 93-107; J. Jackson Walter, "The Ethics in Government Act, Conflict of Interest Laws and Presidential Recruiting," Public Administration Review, vol. 41, no. 6 (November/December 1981), pp. 659-665; and Edna Earle Vass Johnson, "Agency 'Capture': The 'Revolving Door' Between Regulated Industries and Their Regulating Agencies," University of Richmond Law Review, vol. 18, no. 1 (Fall 1983), pp. 95-120. |

| 10. |

17 Stat. 202, June 1, 1872. This early provision was included as a section of the Post Office Department appropriations law for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1873. The provision stated, "That it shall not be lawful for any person who shall hereafter be appointed an officer, clerk, or employee in any of the executive departments to act as counsel, attorney, or agent for prosecuting any claim against the United States which was pending in said departments while he was said officer, clerk, or employee, nor in any manner, nor by any means, to aid in the prosecution of such claim, within two years next after he shall have ceased to be such an officer, clerk, or employee." |

| 11. |

41 Stat. 131, July 11, 1919. |

| 12. |

P.L. 78-395, §19(e), 58 Stat. 668, July 1, 1944. |

| 13. |

P.L. 87-849, 76 Stat. 119, October 23, 1962. Also see U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Bribery, Graft, and Conflicts of Interest, report to accompany H.R. 8140, 87th Cong., 1st sess., July 20, 1961, H.Rept. 87-748 (Washington: GPO, 1961). |

| 14. |

P.L. 95-521, Title V, 92 Stat. 1824, 1864, October 26, 1978. |

| 15. |

P.L. 101-194, Title I, §101(a), 103 Stat. 1716, November 30, 1989. |

| 16. |

P.L. 110-81, §101(a), 121 Stat. 736, September 14, 2007. A "very senior" executive branch official is defined in 18 U.S.C. §207(d) as a person who "(A) serves in the position of Vice President of the United States, (B) is employed in a position in the executive branch of the United States (including any independent agency) at a rate of pay payable for level I of the Executive Schedule or employed in a position in the Executive Office of the President at a rate of pay payable for level II of the Executive Schedule, or (C) is appointed by the President to a position under section 105(a)(2)(A) of title 3 or by the Vice President to a position under section 106(a)(1)(A) of title 3." |

| 17. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Integrity in Post-Employment Act, report to accompany S. 2334, 99th Cong., 2nd sess., August 12, 1986, S.Rept. 99-396 (Washington: GPO, 1986), pp. 7-11. Also see United States v. Nasser (476 F.2d 1111, 1116 (7th Circ. 1973). |

| 18. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Integrity in Post-Employment Act, report to accompany S. 237, 100th Cong., 1st sess., July 7, 1987, S.Rept. 100-101 (Washington: GPO, 1987), pp. 6-8. Also see Brown v. District of Columbia Board of Zoning (423 A.2d 1276, 1282 (D.C. App. 1980). |

| 19. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, Public Officials Integrity Act of 1977, report to accompany S. 555, 95th Cong., 1st sess., May 16, 1977, S.Rept. 95-170 (Washington: GPO, 1977), pp. 31-32. |

| 20. |

Jeffrey E. Cohen, "The Dynamics of the 'Revolving Door' on the FCC," American Journal of Political Science, vol. 30, no. 4 (November 1986), pp. 689-708; and William Gormley, "A Test of the Revolving Door Hypothesis on the FCC," American Journal of Political Science, vol. 23, no. 4 (November 1979), pp. 665-683. |

| 21. |

Cohen, "The Dynamics of the 'Revolving Door' on the FCC," p. 690; and Ross D. Eckert, "The Life Cycle of Regulatory Commissioners," Journal of Law and Economics, vol. 24, no. 1 (April 1981), pp. 113-120. |

| 22. |

David Zaring, "Against Being Against the Revolving Door," University of Illinois Law Review, vol. 2013, no. 2 (2013), pp. 507-550. |

| 23. |

Sounman Hong and Taek Kyu Kim, "Regulatory Capture in Agency Performance Evaluation: Industry Expertise Versus Revolving-Door Lobbying," Public Choice, vol. 171 (2017), pp. 167-186. |

| 24. |

U.S. Office of Government Ethics, "Memorandum Dated October 4, 2006 from Robert I. Cusick, Director, to Designated Agency Ethics Officials Regarding 'Particular Matter Involving Specific Parties,' 'Particular Matter,' and 'Matter,'" Advisory Opinion 06x9, October 4, 2006, p. 3, at https://oge.gov/web/oge.nsf/0/624E14B0D710694B85257E96005FBE7E/$FILE/06x9_.pdf. |

| 25. |

U.S. Office of Government Ethics, Introduction to the Primary Post-Government Employment Restrictions Applicable to Former Executive Branch Employees, LA-16-08, Washington, DC, September 23, 2016, at https://oge.gov/Web/OGE.nsf/OGE%20Advisories/3741DC247191C8B88525803B0052BD7E/$FILE/LA-16-08.pdf?open. |

| 26. |

18 U.S.C. §207(a)(1). |

| 27. |

18 U.S.C. §207(a)(2). |

| 28. |

18 U.S.C. §207(b). |

| 29. |

18 U.S.C. §207(c). |

| 30. |

18 U.S.C. §207(d). |

| 31. |

18 U.S.C. §207(f). For more information on postemployment laws for federal personnel, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10238, Executive Branch Ethics and Financial Conflicts of Interest: Disclosure, by Cynthia Brown; and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10250, Executive Branch Ethics and Financial Conflicts of Interest: Disqualification, by Cynthia Brown. |

| 32. |

The foundation of conflict-of-interest mitigation is grounded in financial disclosure requirements contained in the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, as amended (5 U.S.C. appendix 4 §§101-111). Conflict-of-interest laws apply to virtually all individuals covered by the revolving door, but also other government employees that might not be covered by 18 U.S.C. §207 revolving door restrictions. In general the goal of financial disclosure requirements is "to promote public confidence in the integrity of Government officials," by avoiding conflicts of interest that might arise from financial holdings. Each agency's designated agency ethics official (DAEO) reviews financial disclosure statements to identify actual or potential conflicts of interest and works with the official to mitigate the situation as appropriate. This may include, among other options, recusal from specific decisionmaking and divestment of certain assets. The Office of Government Ethics (OGE) has issued regulations to guide the DAEOs in their interpretation and implementation of the Ethics in Government Act (5 C.F.R. Part 2634). These provisions apply both to individuals upon entering government in covered positions and those currently serving in government in covered positions. Agencies also may issue supplemental regulations that further restrict ownership of certain types of assets or outside employment. For example, the National Credit Union Administration has issued supplemental regulations that further restrict the type of outside employment agency officials may take with credit unions or banks (5 C.F.R. §9601.103). A full list of supplemental regulations can be found at 5 C.F.R. §§3100-10101. |

| 33. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Former Federal Trade Officials: Laws on Post-Employment Activities, Foreign Representation, and Lobbying, GAO-10-766, June 2010, p. 3, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-766. |

| 34. |

Nora Dörrenbächer, "Patterns of Post-Cabinet Careers: When One Door Closes Another Door Opens?" Acta Politica, vol. 51, no. 4 (October 2016), p. 474. |

| 35. |

Sounman Hong and Taek Kyu Kim, "Regulatory Capture in Agency Performance Evaluation: Industry Expertise Versus Revolving-Door Lobbying," Public Choice, vol. 171, no. 1-2 (April 2017), pp. 167-186. |

| 36. |

22 U.S.C. §§611-621 and 2 U.S.C. §§1601-1614. |

| 37. |

This paragraph was originally written by Jack Maskell, formerly a legislative attorney in the Congressional Research Service's American Law Division. For more information on FARA, see CRS In Focus IF10499, Foreign Agents Registration Act: An Overview, by Jacob R. Straus; and CRS Report R45037, The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA): A Legal Overview, by Cynthia Brown. For more information on LDA, see CRS Report R44292, The Lobbying Disclosure Act at 20: Analysis and Issues for Congress, by Jacob R. Straus; and CRS Report R40947, Lobbying the Executive Branch: Current Practices and Options for Change, by Jacob R. Straus. |

| 38. |

5 C.F.R. §2641. |

| 39. |

5 C.F.R. §2641.101. |

| 40. |

5 C.F.R. §730. |

| 41. |

5 C.F.R. §9001. A full list of supplemental regulations can be found at 5 C.F.R. §§3100-9601. |

| 42. |

President Kennedy's executive order included prohibitions on outside employment, use of public office for private gain, receiving compensation from the private sector for government work, and receiving compensation for consulting, lectures, or written material. U.S. President (Kennedy), "Executive Order 10939: To Provide A Guide on Ethical Standards to Government Officials," 26 Federal Register 3951, May 5, 1961. |

| 43. |

U.S. President (Lyndon B. Johnson), Executive Order 11222, "Prescribing Standards of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees," 30 Federal Register 6469, May 11, 1965. |

| 44. |

U.S. President (Nixon), Executive Order 11590, "Applicability of Executive Order No. 11222 and Executive Order No. 11478 to the United States Postal Service and of Executive Order No. 11478 to the Post Rate Commission," 36 Federal Register 7831, April 23, 1971. |

| 45. |

U.S. President (Reagan), Executive Order 12565, "Prescribing a Comprehensive System of Financial Reporting for Officers and Employees in the Executive Branch," 51 Federal Register 34437, September 25, 1986. |

| 46. |

U.S. President (George H. W. Bush), Executive Order 12674, "Principles of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees," 54 Federal Register 15159, April 12, 1989; and U.S. President (George H. W. Bush), Executive Order 12731, "Principles of Ethical Conduct for Government Officers and Employees," 55 Federal Register 42547, October 17, 1990. |

| 47. |

U.S. President (Clinton), Executive Order 12834, "Ethics Commitments by Executive Branch Appointees," 58 Federal Register 5911, January 22, 1993. |

| 48. |

U.S. President (Obama), Executive Order 13490, "Ethics Commitments by Executive Branch Personnel," 74 Federal Register 4673, January 21, 2009. |

| 49. |

U.S. President (Trump), Executive Order 13770, "Ethics Commitments by Executive Branch Appointees," 82 Federal Register 9333, January 28, 2017. |

| 50. |

David Zaring, "Against Being Against the Revolving Door." |

| 51. |

David Zaring, "Against Being Against the Revolving Door"; and Wentong Zheng, "The Revolving Door," Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 90, no. 3 (2015), pp. 1265-1308. |

| 52. |

Timothy M. LaPira and Herschel F. Thomas, Revolving Door Lobbying: Public Service, Private Influence, and the Unequal Representation of Interests (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2017), p. 6. |

| 53. |

For example, see H.R. 484 (115th Congress), which would have created a lifetime ban on registering as a foreign agent under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA; 22 U.S.C. §§611-622) for certain political appointees; or S. 1189 (115th Congress), which would have created a lifetime ban from becoming a registered lobbyist for former Members of Congress. |

| 54. |

For example, see Laurence Tai and Daniel Carpenter, "SEC Capture by Revolving Door: Strengths and Weaknesses in the Evidence Base," Law & Financial Markets Review, vol. 8, no. 3 (September 2014), pp. 227-240. |

| 55. |

Blanes, Draca, and Fons-Ronen, "Revolving Door Lobbyists." |

| 56. |

John M. de Figueiredo and Brian Khelleher Richter, "Advancing the Empirical Research on Lobbying," Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 17, no. 1 (2014), p. 167. |

| 57. |

David Zaring, "Against Being Against the Revolving Door." |

| 58. |

Edna Earle Vass Johnson, "Agency Capture: The Revolving Door Between Regulated Industries and Their Regulating Agencies," University of Richmond Law Review, vol. 18, no. 1 (Fall 1983), p. 118. |

| 59. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Reform, Policy and Supporting Positions, committee print, 108th Cong., 2nd sess., November 22, 2004 (Washington: GPO, 2004), at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2004/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2004.pdf; U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Policy and Supporting Positions, committee print, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., November 12, 2008, S.Prt. 110-36 (Washington: GPO, 2008), at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2008/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2008.pdf; U.S. Congress, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Policy and Supporting Positions, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., December 1, 2012 (Washington: GPO, 2012), at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2012/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2012.pdf; and U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Policy and Supporting Positions, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., December 1, 2016 (Washington: GPO, 2016), at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016.pdf. |

| 60. |

U.S. Government Publishing Office, "United States Government Policy and Supporting Positions (Plum Book)," at https://www.govinfo.gov/collection/plum-book?path=/gpo/United%20States%20Government%20Policy%20and%20Supporting%20Positions%20(Plum%20Book)/2016. |

| 61. |

For more information on federal salaries, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, Federal Workers: Results of Studies on Federal Pay Varied Due to Differing Methodologies, GAO-12-564, June 2012, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-564; Congressional Budget Office, Comparing Compensation of Federal and Private-Sector Employees, 2011 to 2015, April 2017, at https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/01-30-FedPay.pdf; and CRS Report R42636, Comparing Compensation for Federal and Private-Sector Workers: An Overview, by David H. Bradley. |

| 62. |

2 U.S.C. §1605(a)(4). |

| 63. |

For more information on the LDA database, see CRS Report RL34377, Lobbying Registration and Disclosure: The Role of the Clerk of the House and the Secretary of the Senate, by Jacob R. Straus. |

| 64. |

Robert H. Salisbury et al., "Who You Know versus What You Know: The Uses of Government Experience for Washington Lobbyists," American Journal of Political Science, vol. 33, no. 1 (February 1989), pp. 175-195; and Rafael Gely and Asghar Zardkoohi, "Measuring the Effects of Post-Government-Employment Restrictions," American Law and Economics Review, vol. 3, no. 1 (Fall 2001), pp. 288-301. |

| 65. |

E.O. 13490. The executive order also included a waiver provision to allow lobbyists to serve in the Administration, under certain conditions, despite the ban on such service. |

| 66. |

Connections between these data and past studies of the revolving door are generally difficult to discern, since few studies have comprehensively looked at executive branch appointees. Rather, past studies have generally looked at specific independent agencies or subsets of cabinet agencies. Most studies into the revolving door have not examined executive branch activity. Therefore, there is limited literature on the revolving door phenomenon in the executive branch. The studies that do exist have been generally limited in scope, but with potentially interesting findings. For example, past studies have found a high percentage of Federal Communications Commission officials who have been or become registered lobbyists (John M. de Figueiredo and James J. Kim, "When Do Firms Hire Lobbyists? The Organization of Lobbying at the Federal Communications Commission," Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 13, no. 6 [December 2006], pp. 883-900). Another study found a high degree of movement between attorneys in the Department of Justice's Southern District of New York and Wall Street firms (Zaring, "Against Being Against the Revolving Door"; Brooke Parker, "Dangers of the 'Revolving Door': Disqualification of Attorneys Because of Prior Government Public Service," Journal of the Legal Profession, vol. 22 [1998], pp. 317-330; Toni Makkai and John Braithwaite, "In and Out of the Revolving Door: Making Sense of Regulatory Capture," Journal of Public Policy, vol. 12, no. 1 [January 1992], pp. 61-78; James S. Roberts Jr. "The 'Revolving Door': Issues Related to the Hiring of Former Federal Government Employees," Alabama Law Review, vol. 42, issue 2 [Winter 1992], pp. 343-398; and David Miller and William Dinan, Revolving Doors, Accountability and Transparency—Emerging Regulatory Concerns and Policy Solutions in the Financial Crisis, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], March 5, 2009, at http://www.dmiller.info/images/docs/OECD_revolving%20door-2009.pdf). |

| 67. |

Some studies suggest that such a link exists and that lobbyists who are tied into a broader policy network are more effective than those who are not. See Daniel P. Carpenter, Kevin M. Esterling, and David M.J. Lazer, "The Strength of Weak Ties in Lobbying Networks: Evidence from Health-Care Politics in the United States," Journal of Theoretical Politics, vol. 10, no. 4 (October 1998), p. 418. |

| 68. |

Emily Chamlee-Wright and Virgil Henry Storr, "Social Capital, Lobbying and Community-Based Interest Groups," Public Choice, vol. 149, no. 1-2 (October 2011), pp. 167-185. |

| 69. |

For more information on executive order "cooling off" period restrictions, see CRS Report R44974, Ethics Pledges and Other Executive Branch Appointee Restrictions Since 1993: Historical Perspective, Current Practices, and Options for Change, by Jacob R. Straus. |

| 70. |

18 U.S.C. §207. For more information on postemployment laws for federal personnel, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10238, Executive Branch Ethics and Financial Conflicts of Interest: Disclosure, by Cynthia Brown; and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10250, Executive Branch Ethics and Financial Conflicts of Interest: Disqualification, by Cynthia Brown. Also, see James D. Carroll and Robert N. Roberts, "'If Men Were Angels': Assessing the Ethics in Government Act of 1978," Policy Studies Journal, vol. 17, no. 2 (Winter 1988-1989), p. 440. |

| 71. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Ethics Regulations: Compartmentalization of Agencies Under the Ethics in Government Act, GAO/GGD-87-25, February 1987, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/210/209097.pdf. |

| 72. |

GAO, Ethics Regulations, p. 7. |

| 73. |

For example, see Daniel G. Webber Jr., "Proposed Revolving Door Restrictions: Limiting Lobbying by Ex-Lawmakers," Oklahoma City University Law Review, vol. 21, no. 1 (Spring 1996), pp. 29-52. |

| 74. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, S. 420, the Ethics in Government Reform Act of 1993, and S. 79, the Responsible Government Act of 1993, hearing on S. 420 and S. 79, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., March 5, 1993, S.Hrg. 103-63 (Washington: GPO, 193), p. 1. |

| 75. |

Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, S. 420 and S. 79, p. 1. |

| 76. |

For more information on executive branch ethics pledges, see CRS Report R44974, Ethics Pledges and Other Executive Branch Appointee Restrictions Since 1993: Historical Perspective, Current Practices, and Options for Change, by Jacob R. Straus. |

| 77. |

In the 116th Congress (2019-2020), at least four measures have been introduced to codify elements of previous or existing ethics pledges. These include H.R. 1, H.R. 209, H.R. 391, and H.R. 1523. For more information on H.R. 1, see CRS In Focus IF11097, H.R. 1: Overview and Related CRS Products, coordinated by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 78. |

U.S. Office of Government Ethics, "After Leaving Government," Post-Government Employment, at https://www.oge.gov/web/OGE.nsf/Post-Government%20Employment/5C506BC66E5C5C8F85257E96006364F0?opendocument. |

| 79. |

The Department of Justice is tasked with investigating and potentially prosecuting suspected noncompliance. 5 C.F.R. §2641.103. Statutory revolving door provisions are found in the criminal code at 18 U.S.C. §207. |

| 80. |

U.S. Office of Government Ethics, "Mission and Responsibilities," at https://www.oge.gov/Web/OGE.nsf/Mission%20and%20Responsibilities; and U.S. Office of Government Ethics, "Where to Report Misconduct," at https://www.oge.gov/Web/OGE.nsf/Resources/Where+to+Report+Misconduct. |