Exceptions to the Budget Control Act’s Discretionary Spending Limits

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) established statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2012-FY2021. There are currently separate annual limits for defense discretionary and nondefense discretionary spending.

The law specifies that spending for certain activities, such as responding to a national emergency or fighting terrorism, will receive special budgetary treatment. This spending is most easily thought of as being exempt from the spending limits. Formally, however, the BCA states that the enactment of such spending allows for a subsequent upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate the spending. As a result, these types of spending are referred to as “adjustments.”

Two adjustments—for spending designated as emergency or for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)—have made up the vast majority of the spending. (These adjustments are uncapped and can be used for broad purposes.) Five other adjustments are capped and can be used for more specific programs or purposes, and two additional adjustments address potential technical issues that can arise in enforcing the spending limits.

According to information provided by the Office of Management and Budget (the agency responsible for evaluating compliance with the discretionary spending limits), in the seven fiscal years that have concluded since the discretionary spending limits were instituted, approximately $891 billion of spending has occurred under these adjustments. Spending for OCO made up 73% of the total, and spending for emergencies made up 20%.

In addition to the adjustments specified in the BCA, the 21st Century Cures Act (Division A of P.L. 114-255) provided that a limited amount of appropriations for specified purposes are to be exempt from the discretionary spending limits. As of the date of this report, the Cures Act is unique in providing an exemption of this kind.

Exceptions to the Budget Control Act's Discretionary Spending Limits

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Spending Not Subject to the Limits, Formally Referred to as Adjustments

- Spending Under the BCA Limits and Adjustments, FY2012-FY2018

- Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT)

- Emergency Requirements

- Disaster Relief

- Formula Used for FY2012-FY2018

- Formula for FY2019-FY2021

- Wildfire Suppression

- Program Integrity Adjustments

- Continuing Disability Reviews and Redeterminations

- Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control

- Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessments

- Changes in Concepts and Definitions

- Technical Adjustment (Allowance) for Estimating Differences

- 21st Century Cures Act Spending Not Subject to the Limits

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Wildfire Suppression: Allowable Adjustments

- Table 2. Continuing Disability Reviews and Redeterminations: Allowable Adjustments

- Table 3. Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control: Allowable Adjustments

- Table 4. Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessments: Allowable Adjustments

- Table 5. 21st Century Cures Act Spending Not Subject to the Limits

- Table A-1. Discretionary Spending Limits and Adjustments Under the BCA, FY2012-FY2018

Summary

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) established statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2012-FY2021. There are currently separate annual limits for defense discretionary and nondefense discretionary spending.

The law specifies that spending for certain activities, such as responding to a national emergency or fighting terrorism, will receive special budgetary treatment. This spending is most easily thought of as being exempt from the spending limits. Formally, however, the BCA states that the enactment of such spending allows for a subsequent upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate the spending. As a result, these types of spending are referred to as "adjustments."

Two adjustments—for spending designated as emergency or for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)—have made up the vast majority of the spending. (These adjustments are uncapped and can be used for broad purposes.) Five other adjustments are capped and can be used for more specific programs or purposes, and two additional adjustments address potential technical issues that can arise in enforcing the spending limits.

According to information provided by the Office of Management and Budget (the agency responsible for evaluating compliance with the discretionary spending limits), in the seven fiscal years that have concluded since the discretionary spending limits were instituted, approximately $891 billion of spending has occurred under these adjustments. Spending for OCO made up 73% of the total, and spending for emergencies made up 20%.

In addition to the adjustments specified in the BCA, the 21st Century Cures Act (Division A of P.L. 114-255) provided that a limited amount of appropriations for specified purposes are to be exempt from the discretionary spending limits. As of the date of this report, the Cures Act is unique in providing an exemption of this kind.

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25), which was signed into law on August 2, 2011,1 includes statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2012-FY2021, often referred to as "spending caps."2 There are currently separate annual limits for defense discretionary and nondefense discretionary spending. (The defense category consists only of discretionary spending in budget function 050, "national defense." The nondefense category includes discretionary spending in all other budget functions.3) Each discretionary spending limit is enforced separately through sequestration.4

Discretionary spending that is provided for certain purposes is effectively exempt from the spending limits. This means that when compliance with the discretionary spending limits is evaluated, these special types of spending are treated differently:

- Adjustments. The law specifies that spending for certain activities, such as responding to a national emergency or fighting terrorism, will receive special budgetary treatment. This spending is most easily thought of as being exempt from, or an exception to, the spending limits. Formally, however, the BCA states that the enactment of such spending allows for a subsequent upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate the spending. As a result, these types of spending are referred to as "adjustments." (The reference here to "adjustments to the limits" should be distinguished from statutory changes that have been enacted since 2011 increasing the spending limits.) These adjustments are not formally made until after the spending legislation has been enacted. Therefore, references to the discretionary spending limits typically refer to the spending limit level before the permitted adjustments have been included.

- 21st Century Cures Act spending exempt from the limits. In addition to the adjustments specified in the BCA, the 21st Century Cures Act (Division A of P.L. 114-255), enacted on December 13, 2016, provided that a limited amount of appropriations for specified purposes (at the National Institutes for Health and the Food and Drug Administration and for certain grants to respond to the opioid crisis) are to be subtracted from any cost estimate provided for the purpose of enforcing the discretionary spending limits. As of the date of this report, the Cures Act is unique in providing a statutory exemption of this kind.

These adjustments and the Cures Act exemptions complicate conversations and information related to overall discretionary spending amounts. When references are made to total discretionary spending, those figures may include spending that is provided under the adjustments authority as well as the Cures Act exemptions. However, when references are made to the discretionary spending limits, typically they do not include the spending that occurs as part of the adjustments or the Cures Act exemptions. More information is provided below on each adjustment and the Cures Act.

Spending Not Subject to the Limits, Formally Referred to as Adjustments

While the categories of spending described below are often thought of as being exempt from the spending limits, in fact the enactment of such spending allows for a subsequent upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate the spending. For this reason, we refer to these categories of spending as "adjustments." Permissible adjustments to the discretionary spending limits are specified in Section 251(b) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (Title II of P.L. 99-177 (2)), unless otherwise noted.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is responsible for evaluating compliance with the discretionary spending limits. To provide transparency to the process of evaluating such compliance, OMB is required to submit sequestration reports to Congress.5 In these reports, and in the President's annual budget submission, OMB is required to calculate the permissible adjustments and to specify the discretionary spending limits for the fiscal year and each succeeding year.

The sections below provide more detailed information on the adjustments. These adjustments vary greatly. Two adjustments—Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) and emergency spending—have made up the vast majority of the spending. These adjustments are uncapped and can be used for broad purposes. Five other adjustments are capped and can be used for specific programs or purposes. Two additional adjustments address potential technical issues that can arise in enforcing the spending limits.

Spending Under the BCA Limits and Adjustments, FY2012-FY2018

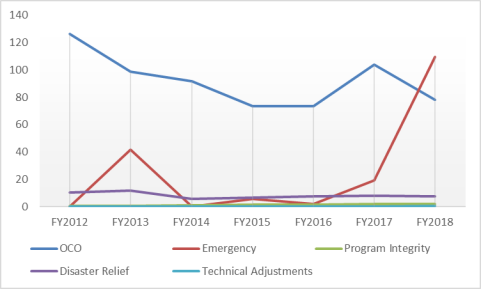

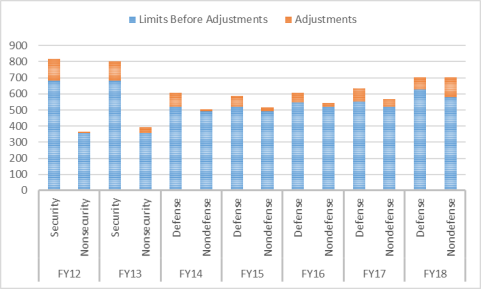

The most recent adjustment totals provided by OMB can be seen in Figure 1 and are detailed in Table A-1. Trends in adjustments amounts can be seen in Figure 2. According to OMB, in the seven fiscal years since the discretionary spending limits were instituted, approximately $891 billion of spending has been provided under these adjustments.6 (This does not include levels for FY2019, which has not yet concluded.) Spending for OCO totaled approximately $646 billion during the period, making up 73% of the total spending permitted under the adjustments. Spending for OCO ranged from a low of approximately $74 billion (FY2015 and FY2016) to a high of approximately $104 billion (FY2017). Spending provided under the emergency spending designation totaled approximately $178 billion during the period, making up 20% of total spending provided under the adjustments. Most of this amount was provided for a single fiscal year (approximately $110 billion in FY2018). The other seven adjustments made up about 7% of total spending occurring under the adjustments.

|

Figure 1. Total Discretionary Spending Limits and Adjustments Under the BCA FY2012-FY2018, discretionary budget authority in billions of dollars |

|

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget, OMB Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, August 20, 2018, p. 4. Notes: Details may not total due to rounding. In FY2012 and FY2013 the separate limits comprised different categories, referred to as security and nonsecurity. Totals appearing as "limits before adjustment" include downward adjustments that occur due to the lack of enactment of a bill reported by the Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction. Totals appearing as "limits" incorporate changes to the limits made by the American Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-67), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). For more information on those changes to the limits, see CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT)

Adjustments are made to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending that has been designated as being for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (referred to in this report as OCO). There is no statutory limit on the amount of spending that may be designated for OCO, meaning that Congress and the President can together designate any amount they agree upon. There is no statutory definition of what activities are eligible to be designated for OCO. The only requirements associated with this designation are that (1) the legislation must specify that the spending is for OCO, (2) each account within an appropriations bill that will be for OCO must be designated separately—meaning that an entire bill that includes several separate accounts cannot have a "blanket" OCO designation—and (3) the President must also designate the spending as being for an OCO requirement.

It is not unusual for Congress to include language stating that spending designated for OCO is available only if the President also designates it as being for OCO. Further, the language typically states that the President designate "all such amounts" or none.

For example, in March 2018, the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of 2018 (P.L. 115-141) included OCO designations for many accounts. Two such accounts are included below:

Military Personnel, Army

For an additional amount for "Military Personnel, Army", $2,683,694,000: Provided, That such amount is designated by the Congress for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(ii) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.

Military Personnel, Navy

For an additional amount for "Military Personnel, Navy", $377,857,000: Provided, That such amount is designated by the Congress for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(ii) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.

In addition, Section 6 of the act stated:

Each amount designated in this Act by the Congress for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(ii) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 shall be available (or rescinded, if applicable) only if the President subsequently so designates all such amounts and transmits such designations to the Congress.

The President then formally designated the spending as being for OCO:

In accordance with section 6 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 1625; the "Act"), I hereby designate for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism all funding (including the rescission of funds) and contributions from foreign governments so designated by the Congress in the Act pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as outlined in the enclosed list of accounts.

The details of this action are set forth in the enclosed memorandum from the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.7

Not all of OCO spending falls within the statutory definition of defense (050). For example, in FY2017, of the approximate $104 billion of discretionary spending designated as OCO, $21 billion was in the nondefense category.8 Likewise, while a majority of OCO spending appears in the Department of Defense appropriations bill, it also commonly appears in the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations bill as well as the Department of Homeland Security appropriations bill and the Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies appropriations bill.

Emergency Requirements

Adjustments may also be made to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending that has been designated as being an "emergency requirement." There is no statutory limit on the amount of spending that may be designated for emergencies, meaning that Congress and the President can together designate any amount they agree upon. Likewise, there is no statutory classification of what activities are eligible to be designated as an emergency requirement. The only statutory requirements are that (1) the legislation must specify that the spending is for an emergency requirement, (2) each account within an appropriations bill that will be for "emergency requirements" must be designated separately—meaning that an entire bill that includes several separate accounts cannot have a "blanket" emergency requirement designation—and (3) the President must also designate the spending as being for an emergency requirement.

It is not unusual for Congress to include language stating that the spending designated for emergency is available only if the President also designates it as being for an emergency. Further, the language typically states that the President designate "all such amounts" or none.

For example, in October 2017, the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-72), was enacted, which included emergency requirement designations for several accounts. One such account is included below:

For an additional amount for "Wildland Fire Management", $184,500,000, to remain available through September 30, 2021, for urgent wildland fire suppression operations: Provided, That such funds shall be solely available to be transferred to and merged with other appropriations accounts from which funds were previously transferred for wildland fire suppression in fiscal year 2017 to fully repay those amounts: Provided further, That such amount is designated by the Congress as being for an emergency requirement pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985.

In addition, Title II of the act states:

Sec. 304. Each amount designated in this division by the Congress as being for an emergency requirement pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 shall be available only if the President subsequently so designates all such amounts and transmits such designations to the Congress.

After this legislation was enacted, the President formally designated the spending as an emergency requirement.

In accordance with section 304 of division A of the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017 (H.R. 2266; the "Act"), I hereby designate as emergency requirements all funding (including the repurposing of funds and cancellation of debt) so designated by the Congress in the Act pursuant to section 251(b)(2)(A) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as outlined in the enclosed list of accounts.

The details of this action are set forth in the enclosed memorandum from the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.9

Disaster Relief

Adjustments may also be made to the spending limits to accommodate certain enacted spending that has been designated as being for disaster relief. The BCA defines disaster relief as activities carried out pursuant to a determination under Section 102(2) of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act.10

Adjustment amounts permitted under the disaster relief designation are limited and are calculated pursuant to a statutory formula. Not all spending that is enacted to provide for disaster relief includes this designation. Congress may provide funds for the purpose of disaster relief but allow the spending to count against the discretionary spending limits, or it may designate the spending as an emergency requirement, particularly when the level of disaster relief being provided would exceed the amount permitted under the disaster relief adjustment. For example, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 included appropriations related to Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria of $23.5 billion for the Federal Emergency Management Agency's Disaster Relief Fund for major disasters declared pursuant to the Stafford Act.11 However, that spending was designated as an emergency requirement and therefore employed the emergency adjustment described above, as opposed to the disaster relief adjustment, which is capped.12

The formula used to determine the maximum amount permitted under the disaster relief adjustment was amended by the CAA of 2018, and, as described below, the new formula is to apply to FY2019 and beyond.13

OMB is required by law to include in its Sequestration Update Report a preview estimate of the adjustment for disaster relief for the upcoming fiscal year. For example, OMB included a preview estimate of $7.366 billion as the cap for disaster relief adjustment in its Sequestration Update Report for 2018 (released on August 18, 2017). Subsequently, appropriations were enacted in the CAA of 2018 providing $7.366 billion for FY2018 for the Federal Emergency Management Agency's Disaster Relief Fund in the FY2018 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act (division F of the CAA of 2018).

Formula Used for FY2012-FY2018

The formula used to calculate the limit for the disaster relief adjustment for FY2018 and earlier required that the annual adjustment for disaster relief not exceed "the average funding provided for disaster relief over the previous 10 years, excluding the highest and lowest years," plus the amount by which appropriations in the previous fiscal year was less than the average funding level, often referred to as carryover.

Under this formula, if the carryover from one year was not used in the subsequent year, it could not carry forward for a subsequent year. According to OMB, this "led to a precipitous decline in the funding ceiling as higher disaster funding years began to fall out of the 10-year average formula."14 According to OMB, the limit for the adjustment fell from a high of $18.43 billion in 2015 to a low of $7.366 billion in 2018.

Formula for FY2019-FY2021

The CAA of 2018 altered the formula for the disaster relief adjustment in ways "that will ultimately increase the funding ceiling," according to OMB.15 The formula for FY2019 and beyond comprises the total of

- the average funding provided for disaster relief over the previous 10 years, excluding the highest and lowest years;

- 5% of the total appropriations provided either (1) since FY2012 or (2) in the previous 10 years—whichever is less—subtracting any amount of budget authority that was rescinded in that period with respect to amounts provided for major disasters declared pursuant to the Stafford Act and designated by the Congress and the President as being for emergency requirements (as described above); and

- the cumulative net total of the unused carryover for FY2018, as well as unused carryover for any subsequent fiscal years.16

OMB has stated that under this formula, the potential adjustment limit for disaster relief for FY2019 would be capped at $14.965 billion.17

Wildfire Suppression

The CAA of 2018 included a new adjustment that applies to FY2020-FY2027 for wildfire suppression.18

Adjustments may be made to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending that provides an amount for wildfire suppression operations in the Wildland Fire Management accounts at the Departments of Agriculture or Interior.19 The law states that the adjustments may not exceed the amounts shown below for each of FY2020-FY2027. However, the law allows such an adjustment to accommodate "additional new budget authority" for wildfire suppression in excess of the average costs for wildfire suppression operations as reported in the President's budget request for FY2015, which is $1.394 billion.20 Unlike some of the adjustments described above, this adjustment does not require a separate additional designation from the President.

|

Fiscal Year |

Allowable Adjustment |

|

2020 |

$2.250 billion |

|

2021 |

$2.350 billion |

|

2022 |

$2.450 billion |

|

2023 |

$2.550 billion |

|

2024 |

$2.650 billion |

|

2025 |

$2.750 billion |

|

2026 |

$2.850 billion |

|

2027 |

$2.950 billion |

Program Integrity Adjustments

The BCA includes two separate adjustments to accommodate spending related to ensuring that certain program funding is spent appropriately, safeguarding against waste, fraud, and abuse. While these two adjustments are separate under the law, they are often grouped together in budget totals, as in Table A-1.

Continuing Disability Reviews and Redeterminations21

As originally enacted, the BCA permits adjustments to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending for two types of program integrity activities conducted by the Social Security Administration: (1) continuing disability reviews, which are periodic medical reviews of Social Security disability beneficiaries and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients under the age of 65;22 and (2) redeterminations, which are periodic financial reviews of SSI recipients. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) expanded the types of program integrity activities for which the adjustments are permitted. The expanded definition may also accommodate spending for (3) cooperative disability investigation units, which investigate cases of suspected disability fraud; (4) fraud prosecutions by Special Assistant United States Attorneys; and (5) work-related continuing disability reviews, which are periodic earnings reviews of Social Security disability beneficiaries.23

|

Fiscal Year |

Allowable Adjustment |

|

2012 |

$623 million |

|

2013 |

$751 million |

|

2014 |

$924 million |

|

2015 |

$1.123 billion |

|

2016 |

$1.166 billion |

|

2017 |

$1.546 billion |

|

2018 |

$1.462 billion |

|

2019 |

$1.410 billion |

|

2020 |

$1.309 billion |

Source: Section 251(b)(2)(B)(i) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended.

The adjustments may not exceed the amounts shown below for each of FY2012-FY2021.24 However, the law allows such an adjustment to accommodate "additional new budget authority" for program integrity activities in excess of $273 million. Unlike some of the adjustments described above, this adjustment does not require a separate additional designation from the President.

As an example, in March 2018, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), included related spending for continuing disability reviews, redeterminations, and other specified activities:

Of the total amount made available under this heading, not more than $1,735,000,000, to remain available through March 31, 2019, is for the costs associated with continuing disability reviews under titles II and XVI of the Social Security Act, including work-related continuing disability reviews to determine whether earnings derived from services demonstrate an individual's ability to engage in substantial gainful activity, for the cost associated with conducting redeterminations of eligibility under title XVI of the Social Security Act, for the cost of co-operative disability investigation units, and for the cost associated with the prosecution of fraud in the programs and operations of the Social Security Administration by Special Assistant United States Attorneys: Provided, That, of such amount, $273,000,000 is provided to meet the terms of section 251(b)(2)(B)(ii)(III) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended, and $1,462,000,000 is additional new budget authority specified for purposes of section 251(b)(2)(B) of such Act.

Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control

Adjustments are made to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending that specifies an amount for health care fraud and abuse control, but the adjustment may not exceed an amount specified in statute.

|

Fiscal Year |

Allowable Adjustment |

|

2012 |

$270 million |

|

2013 |

$299 million |

|

2014 |

$329 million |

|

2015 |

$361 million |

|

2016 |

$395 million |

|

2017 |

$414 million |

|

2018 |

$434 million |

|

2019 |

$454 million |

|

2020 |

$475 million |

The law states that the appropriations act must specify an amount for the health care fraud and abuse control program at the Department of Health and Human Services. The law states further that the adjustments may not exceed the amounts shown below for each of FY2012-FY2021. However, the law allows such an adjustment to accommodate "additional new budget authority" for health care fraud and abuse control in excess of $311 million. Unlike some of the adjustments described above, this adjustment does not require a separate additional designation from the President.

As an example, in March 2018, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), included related spending for health care fraud and abuse control:

In addition to amounts otherwise available for program integrity and program management, $745,000,000, to remain available through September 30, 2019…. Provided further, That of the amount provided under this heading, $311,000,000 is provided to meet the terms of section 251(b)(2)(C)(ii) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended, and $434,000,000 is additional new budget authority specified for purposes of section 251(b)(2)(C) of such Act.

Reemployment Services and Eligibility Assessments

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), enacted in February 2018, included a new adjustment for FY2019-FY2021.25

|

Fiscal Year |

Allowable Adjustment |

|

2019 |

$33 million |

|

2020 |

$58 million |

|

2021 |

$83 million |

Adjustments may be made to the spending limits to accommodate enacted spending that specifies an amount for grants to states under Section 306 of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. §506). The law states further that the adjustments may not exceed the amounts shown below for each of FY2019-FY2021. However, the law allows such an adjustment to accommodate "additional new budget authority" for reemployment services and eligibility assessments in excess of $117 million. Unlike some of the adjustments described above, this adjustment does not require a separate additional designation from the President.

Changes in Concepts and Definitions

The BCA provided that adjustments may be made to the spending limits to address changes in concepts and definitions. The law requires that OMB calculate such an adjustment when the President submits the budget request and that such changes may be made only after consultation with the House and Senate Appropriations Committees and the House and Senate Budget Committees. Further, the law states that such consultation with the committees shall include written communication that affords the committees an opportunity to comment before official action is taken.

The law states that such changes "shall equal the baseline levels of new budget authority and outlays using up-to-date concepts and definitions, minus those levels using the concepts and definitions in effect before such changes."

It appears that no adjustments have been made to accommodate changes in concepts and definitions since enactment of the BCA in 2011. However, the discretionary spending limits in effect between 1991 and 2002 similarly permitted adjustments to accommodate changes in concepts and definitions. During that period, such adjustments were made as a result of a reclassification that shifted programs between the mandatory and the discretionary categories. Other adjustments were made for accounting changes made by the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 and changes in budgetary treatment and estimating methodologies.26

Technical Adjustment (Allowance) for Estimating Differences

It is common for legislation to be enacted each year that permits an adjustment to the discretionary spending limits for that fiscal year in the event that the limits would be breached as a result of estimating differences between the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and OMB.27 For example, the Financial Services and General Government appropriations act for FY2018 included this provision:

If, for fiscal year 2018, new budget authority provided in appropriations Acts exceeds the discretionary spending limit for any category set forth in section 251(c) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 due to estimating differences with the Congressional Budget Office, an adjustment to the discretionary spending limit in such category for fiscal year 2018 shall be made by the Director of the Office of Management and Budget in the amount of the excess but the total of all such adjustments shall not exceed 0.2 percent of the sum of the adjusted discretionary spending limits for all categories for that fiscal year.28

For that particular fiscal year, OMB had estimating differences with CBO, which OMB stated "would cause OMB estimates to exceed both caps."29 These estimating differences were $4 million for the defense category and $554 million for the nondefense category. OMB stated that the maximum allowable adjustment for estimating differences for FY2018 was $2.81 billion and that the amount of estimating differences ($558 million) was within the allowable adjustment. OMB adjusted the caps upward by the amounts of the estimating differences noted.30

21st Century Cures Act Spending Not Subject to the Limits

Title I in Division A of the 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255), enacted in December 2016, authorized appropriations for programs and activities related to health care, research, and opioid abuse.31 The act also established a distinctive budgetary mechanism related to certain authorizations that is different from the adjustments described above but has a similar effect. Specifically, the act established three accounts: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Innovation Account, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Innovation Account, and the Account for the State Response to the Opioid Crisis. The act then transferred funds from the General Fund of the Treasury to these accounts and authorized those funds to be appropriated for specific dollar amounts in specific fiscal years. Those funds were not to be available for obligation until they were appropriated in appropriations acts each fiscal year.

The act further stated that when appropriations are enacted for such authorized activities—up to the authorized amount each fiscal year—those appropriations are to be subtracted from any cost estimate provided for the purpose of enforcing the discretionary spending limits. This effectively exempts any spending provided for these activities between FY2017 and FY2026 from the spending caps.

Specifically, the bill provides such exceptions for the accounts and amounts shown in below. In each case, the exemptions apply only to the years included in the respective table.

|

Fiscal Year |

Allowable Amount |

|

NIH Innovation Account (§1001) |

|

|

2017 |

$352 million |

|

2018 |

$496 million |

|

2019 |

$711 million |

|

2020 |

$492 million |

|

2021 |

$404 million |

|

2022 |

$496 million |

|

2023 |

$1.085 billion |

|

2024 |

$407 million |

|

2025 |

$127 million |

|

2026 |

$226 million |

|

FDA Innovation Account (§1002) |

|

|

2017 |

$20 million |

|

2018 |

$60 million |

|

2019 |

$70 million |

|

2020 |

$75 million |

|

2021 |

$70 million |

|

2022 |

$50 million |

|

2023 |

$50 million |

|

2024 |

$50 million |

|

2025 |

$55 million |

|

Account for State Response to the Opioid Abuse Crisis (§1003) |

|

|

2017 |

$500 million |

|

2018 |

$500 million |

Appendix. Discretionary Spending Limits and Adjustments Under the BCA

Table A-1. Discretionary Spending Limits and Adjustments Under the BCA, FY2012-FY2018

Discretionary budget authority in billions of dollars

|

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Security |

Non-security |

Security |

Non-security |

Defense |

Non-defense |

Defense |

Non-defense |

Defense |

Non-defense |

Defense |

Non-defense |

Defense |

Non-defense |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Limits |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

OCO/GWOT Adjustment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Emergency Adjustment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Program Integrity Adjustment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Disaster Relief Adjustment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Technical Adjustment for Scoring Differences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Revised Limits Including Adjustments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Office of Management and Budget, OMB Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, August 20, 2018, p. 4.

Notes: Totals may not be exact due to rounding. In FY2012 and FY2013, the separate limits comprised different categories, referred to as security and nonsecurity. Totals appearing as "limits" include downward adjustments that occur due to the lack of enactment of a bill reported by the Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction. Totals appearing as "limits" also reflect changes to the limits made by the American Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-67), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). OMB data above is rounded to billions and therefore shows 0.0 when an amount exists but is smaller than 0.05 billion. The adjustment for Concepts and Definitions was not included by OMB in this table, but it appears that no adjustments have been made for concepts and definitions during this period.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge Grant Driessen, Katie Hoover, Karen Lynch, Brendan McGarry, William Morton, William Painter, James Saturno, Jessica Tollestrup, and Julie Whittaker for their peer review.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information on the Budget Control Act, see CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

| 2. |

Discretionary spending is controlled through the appropriations process and is generally provided annually. The appropriations committees have jurisdiction over the funding of discretionary spending programs, while authorizing committees have jurisdiction over the funding of mandatory (or direct) spending programs. For more information see CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

| 3. |

The statutory limits currently included in the BCA are described in statute as "security" and "nonsecurity" although, as stated above, the security category currently consists of discretionary spending in budget function 050 (national defense) only, and the nonsecurity category includes discretionary spending in all other budget functions other than 050 (national defense). For FY2012 and FY2013, the law defined the security category more broadly to include discretionary spending for the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, and Veterans Affairs; the National Nuclear Security Administration; the intelligence community management account; and all accounts in the international affairs budget function (budget function 150) and defined the nonsecurity category to include discretionary spending in all other budget accounts. This change in category definitions was prescribed by the BCA and happened automatically due to the lack of enactment of a bill reported by the Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction. |

| 4. |

This means that if discretionary appropriations are enacted that exceed a statutory limit for a fiscal year for either category, across-the-board reductions (i.e., sequestration) of nonexempt budgetary resources are made to eliminate the excess spending within that category. The threat of a sequester is designed to deter enactment of appropriations legislation that would violate the spending limits or, in the event that legislation is enacted violating these limits, to automatically reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in law. For more information, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch. |

| 5. |

2. U.S.C. §904 (e), (f), and (g). While OMB is responsible for evaluating compliance with limits and implementing a sequester, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is also required to submit to Congress estimates and assessments related to the discretionary spending limits and adjustments as specified in 2 U.S.C. §904 (e), (f), and (g). Those reports can be found at CBO, "Sequestration," https://www.cbo.gov/topics/budget/sequestration. |

| 6. |

Adjustment levels provided by OMB in sequestration reports appear in billions. Therefore, totals may not be exact due to rounding. |

| 7. |

President Donald Trump, letter to Congress, March 23, 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/text-letter-president-speaker-house-representatives-president-senate-20/. |

| 8. |

OMB, OMB Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, April 6, 2018. |

| 9. |

President Donald Trump, letter to Congress, October 26, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/text-letter-president-speaker-house-representatives-president-senate-10/. |

| 10. |

42 U.S.C. §5122(2). For more information, see CRS Report R42352, An Examination of Federal Disaster Relief Under the Budget Control Act, by Bruce R. Lindsay, William L. Painter, and Francis X. McCarthy; and CRS Report R43784, FEMA's Disaster Declaration Process: A Primer, by Bruce R. Lindsay. |

| 11. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45484, The Disaster Relief Fund: Overview and Issues, by William L. Painter. |

| 12. |

Title VI. |

| 13. |

H.R. 1625, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), §102. |

| 14. |

OMB, OMB Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, August 20, 2019, p. 13. |

| 15. |

As stated in OMB, OMB Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, p. 7. The formula for the disaster relief was amended by Section 102(a)(1) of division O. |

| 16. |

"[W]here the unused carryover for each fiscal year is calculated as the sum of the amounts in subclauses (1) and (II) less the enacted appropriations for that fiscal year that have been designated as being for disaster relief" (P.L. 115-141). |

| 17. |

OMB, OMB Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2019, August 20, 2019, p. 14. For more information on the disaster adjustment, see CRS In Focus IF10720, Calculation and Use of the Disaster Relief Allowable Adjustment, by William L. Painter. |

| 18. |

For more information about wildfire suppression spending, see CRS Report R44966, Wildfire Suppression Spending: Background, Issues, and Legislation in the 115th Congress, by Katie Hoover and Bruce R. Lindsay. For more information about the wildfire suppression adjustment, see also the Wildland Fire Management section in CRS Report R45696, Forest Management Provisions Enacted in the 115th Congress, by Katie Hoover et al. |

| 19. |

The law defines wildfire suppression operations as meaning "the emergency and unpredictable aspects of wildland firefighting, including –(aa) support, response, and emergency stabilization activities; (bb) other emergency management activities; and (cc) the funds necessary to repay any transfers needed for the costs of wildfire suppression operations." |

| 20. |

This is the combination of $1,011,060 for the Forest Service and $383,657 for the Department of the Interior. See U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Justification, March 2014, Table I, p. 259; and U.S. Department of the Interior, Wildland Fire Management, Budget Justifications and Performance Information FY2015, p. 33. |

| 21. |

William Morton, Analyst in Income Security co-authored this section. |

| 22. |

Under Titles II and XVI of the Social Security Act (42 U.S.C. §401 et seq., 1381 et seq.). |

| 23. |

The law includes definitions of the terms continuing disability reviews and redeterminations. See Section 251(b)(2)(B)(ii)(I and II) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, as amended. |

| 24. |

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) in Section 815 amended the adjustments authority related to continuing disability reviews and redeterminations. It increased the adjustment levels for FY2017-FY2020, reduced the adjustment level for FY2021, expanded the types of program integrity activities for which adjustment authority may be used to include cooperative disability investigation units and fraud prosecutions by Special Assistant U.S. Attorneys, and expanded the definition of continuing disability reviews to include work-related continuing disability reviews. |

| 25. |

Division E, §30206(c), CAA, 2018. |

| 26. |

OMB, Budget of the United States Government, FY1992, Budget Enforcement Act Preview Report, February 4, 1991; OMB, Budget of the United States Government, FY1993, Budget Enforcement Act Preview Report, January 29, 1992. |

| 27. |

Such adjustments have been provided for under P.L. 113-76, P.L. 113-285, P.L. 114-113, P.L. 115-31, and P.L. 115-141. |

| 28. |

Section 748. |

| 29. |

As stated in OMB, OMB Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, p. 7. |

| 30. |

OMB, OMB Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, p. 7. |

| 31. |

For more information on the 21st Century Cures Act and the accounts described, see CRS Report R44720, The 21st Century Cures Act (Division A of P.L. 114-255), coordinated by Amanda K. Sarata. |