The Clean Air Act’s Good Neighbor Provision: Overview of Interstate Air Pollution Control

Notwithstanding air quality progress since 1970, challenges remain to reduce pollution in areas exceeding federal standards and to ensure continued compliance elsewhere. The movement of air pollutants across state lines, known as interstate transport, has made it difficult for some downwind states to attain federal ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) standards, partly because states lack authority to limit emissions from other states.

The Clean Air Act’s “Good Neighbor” provision (Section 110(a)(2)(D)) seeks to address this issue and requires states to prohibit emissions that significantly contribute to another state’s air quality problems. It requires each state’s implementation plan (SIP)—a collection of air quality regulations and documents—to prohibit emissions that either “significantly contribute” to nonattainment or “interfere with maintenance” of federal air quality standards in another state. The act also authorizes states to petition EPA to issue a finding that emissions from “any major source or group of stationary sources” violate the Good Neighbor provision (Section 126(b)).

EPA and the states have implemented regional programs to address interstate ozone and PM2.5 transport and comply with the Good Neighbor provision. These programs set emission “budgets” for ozone and PM2.5 precursor emissions—specifically, sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxide (NOx) as PM2.5 precursors and seasonal NOx emissions as an ozone precursor. The current program—the Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR)—focuses on limiting interstate transport of power sector SO2 and NOx emissions to eastern states.

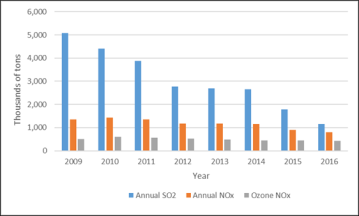

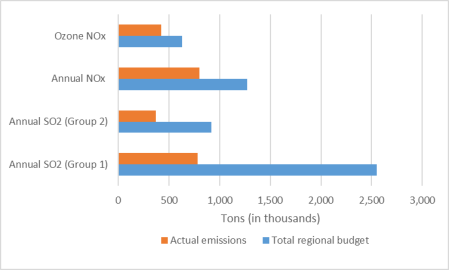

Power sector emissions in CSAPR states are below emission budgets as a result of regulatory and market factors (see figure). Annual SO2, annual NOx, and ozone season NOx emissions from CSAPR sources decreased 77%, 41%, and 15%, respectively, between 2009 and 2016.

CSAPR Emission Trends: 2009-2016

/

Source: EPA Air Markets Program Data, https://ampd.epa.gov/ampd/.

Notes: The Clean Air Interstate Rule was in effect 2009 through the end of 2014 and was replaced by CSAPR on January 1, 2015.

EPA has concluded that regional SO2 and NOx programs have reduced interstate transport of PM2.5 and ozone. The Energy Information Administration’s national-scale analysis identifies market and regulatory factors contributing to emission reductions. It is unclear whether emissions will remain well below budgets, given recent prices of ozone season NOx allowances (i.e., authorization for each ton emitted) and the supply of banked allowances for future use in lieu of emission reductions.

Research indicates that ozone transport harms air quality in downwind states. However, stakeholder views vary regarding the extent to which interstate transport impacts air quality. Some note that some coal-fired power plants do not fully use already-installed pollution controls. Several states have sought additional upwind reductions in ozone precursors through Section 126(b) petitions. Others have questioned the feasibility of achieving additional reductions in ozone precursors, raising concerns about emissions from international or natural sources.

EPA recently proposed to determine that CSAPR fully addresses Good Neighbor obligations for the 2008 ozone standard but has not yet made a “Good Neighbor” determination for the more stringent 2015 ozone standard. The agency has therefore not yet determined whether and how it will update the CSAPR budgets with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.

Members of Congress may have an interest in better understanding how EPA and states implement the Clean Air Act’s Good Neighbor provision, particularly as EPA continues its assessment of Good Neighbor obligations under the 2015 ozone standard.

The following issues, among others, may inform deliberations about interstate air transport. First, the extent to which existing programs will improve air quality in areas not meeting the 2015 ozone standard is to be determined. CSAPR has not addressed NOx emissions from nonpower sector sources, such as large industrial boilers. EPA concluded that industrial sources have potential to cost-effectively reduce NOx emissions but is less certain about the structure of potential NOx control strategies. Second, some have questioned whether additional regulatory incentives are necessary to fulfill Good Neighbor obligations, particularly given current NOx allowance prices. These prices are below the marginal abatement cost, which may result in higher emissions. Third, EPA’s current air quality initiatives may indirectly affect its Good Neighbor assessments. EPA recently sought comment on potential flexibilities for the development of Good Neighbor SIPs.

The Clean Air Act's Good Neighbor Provision: Overview of Interstate Air Pollution Control

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Implementing the Good Neighbor Provision

- SIPs Process

- Section 126(b) Petitions

- Interpreting "Significant Contribution"

- Programs Addressing Interstate Pollution

- Acid Rain Program

- Ozone Control: Regional NOx Programs

- Ozone Transport Commission NOx Budget Program

- NOx Budget Trading Program

- Ozone and PM Control: Regional SO2 and NOx Trading Programs

- Clean Air Interstate Rule

- Cross State Air Pollution Rule

- Results of Regional SO2 and NOx Trading Programs

- Status of Good Neighbor Determinations for Ozone Standards

- Good Neighbor Determinations and the 2008 Ozone Standard

- Good Neighbor Determinations and the 2015 Ozone Standard

- Issues for Congressional Consideration

- NOx Emission Trends

- Incentives for NOx Reductions

- Related EPA Air Quality Initiatives

Summary

Notwithstanding air quality progress since 1970, challenges remain to reduce pollution in areas exceeding federal standards and to ensure continued compliance elsewhere. The movement of air pollutants across state lines, known as interstate transport, has made it difficult for some downwind states to attain federal ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) standards, partly because states lack authority to limit emissions from other states.

The Clean Air Act's "Good Neighbor" provision (Section 110(a)(2)(D)) seeks to address this issue and requires states to prohibit emissions that significantly contribute to another state's air quality problems. It requires each state's implementation plan (SIP)—a collection of air quality regulations and documents—to prohibit emissions that either "significantly contribute" to nonattainment or "interfere with maintenance" of federal air quality standards in another state. The act also authorizes states to petition EPA to issue a finding that emissions from "any major source or group of stationary sources" violate the Good Neighbor provision (Section 126(b)).

EPA and the states have implemented regional programs to address interstate ozone and PM2.5 transport and comply with the Good Neighbor provision. These programs set emission "budgets" for ozone and PM2.5 precursor emissions—specifically, sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxide (NOx) as PM2.5 precursors and seasonal NOx emissions as an ozone precursor. The current program—the Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR)—focuses on limiting interstate transport of power sector SO2 and NOx emissions to eastern states.

Power sector emissions in CSAPR states are below emission budgets as a result of regulatory and market factors (see figure). Annual SO2, annual NOx, and ozone season NOx emissions from CSAPR sources decreased 77%, 41%, and 15%, respectively, between 2009 and 2016.

|

CSAPR Emission Trends: 2009-2016 |

|

|

Source: EPA Air Markets Program Data, https://ampd.epa.gov/ampd/. Notes: The Clean Air Interstate Rule was in effect 2009 through the end of 2014 and was replaced by CSAPR on January 1, 2015. |

EPA has concluded that regional SO2 and NOx programs have reduced interstate transport of PM2.5 and ozone. The Energy Information Administration's national-scale analysis identifies market and regulatory factors contributing to emission reductions. It is unclear whether emissions will remain well below budgets, given recent prices of ozone season NOx allowances (i.e., authorization for each ton emitted) and the supply of banked allowances for future use in lieu of emission reductions.

Research indicates that ozone transport harms air quality in downwind states. However, stakeholder views vary regarding the extent to which interstate transport impacts air quality. Some note that some coal-fired power plants do not fully use already-installed pollution controls. Several states have sought additional upwind reductions in ozone precursors through Section 126(b) petitions. Others have questioned the feasibility of achieving additional reductions in ozone precursors, raising concerns about emissions from international or natural sources.

EPA recently proposed to determine that CSAPR fully addresses Good Neighbor obligations for the 2008 ozone standard but has not yet made a "Good Neighbor" determination for the more stringent 2015 ozone standard. The agency has therefore not yet determined whether and how it will update the CSAPR budgets with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.

Members of Congress may have an interest in better understanding how EPA and states implement the Clean Air Act's Good Neighbor provision, particularly as EPA continues its assessment of Good Neighbor obligations under the 2015 ozone standard.

The following issues, among others, may inform deliberations about interstate air transport. First, the extent to which existing programs will improve air quality in areas not meeting the 2015 ozone standard is to be determined. CSAPR has not addressed NOx emissions from nonpower sector sources, such as large industrial boilers. EPA concluded that industrial sources have potential to cost-effectively reduce NOx emissions but is less certain about the structure of potential NOx control strategies. Second, some have questioned whether additional regulatory incentives are necessary to fulfill Good Neighbor obligations, particularly given current NOx allowance prices. These prices are below the marginal abatement cost, which may result in higher emissions. Third, EPA's current air quality initiatives may indirectly affect its Good Neighbor assessments. EPA recently sought comment on potential flexibilities for the development of Good Neighbor SIPs.

Introduction

The movement of air pollutants across state lines, known as interstate transport, has posed a decades-long challenge to air quality protection. The Clean Air Act (CAA) assigns responsibility to states to limit emissions from sources within their borders as needed to attain federal health-based air quality standards. A state's air quality, however, may be affected by emissions from upwind sources located in a different state. Hence, controlling emissions within the border of a state may not be sufficient to attain the air quality standard. The downwind state lacks authority to limit emissions from the sources in the upwind state(s) but is nonetheless responsible for attaining the federal standards.

Interstate transport has made it difficult for some downwind states to attain federal standards for ozone and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Both of these pollutants are formed by precursor emissions that can travel long distances. Specifically, sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxide (NOx) contribute to the formation of PM2.5 in the air.1 NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) react in sunlight to form ground-level ozone, the main component of smog.2 Studies have shown that these precursor emissions, as well as ozone and PM2.5, are regional pollutants, meaning that they can travel hundreds of miles through the atmosphere.3 For example, Bergin et al.'s study of the eastern United States concluded that regional transport affected air quality in most eastern states. They attributed an average of 77% of each state's ozone and PM2.5 concentrations to emissions from upwind states.4

These regional emissions are associated with health impacts and are therefore of concern. For example, research shows that ground-level ozone is associated with aggravated asthma, chronic bronchitis, heart attacks, and premature death.5 Studies have also linked exposure to particulate matter to respiratory illnesses, such as aggravated asthma, as well as heart attacks and premature death.6

The CAA's "Good Neighbor" provision recognizes such interstate issues and requires states to prohibit emissions that significantly contribute to air quality problems in another state (Section 110(a)(2)(D)). It requires each state's implementation plan—a collection of air quality regulations and documents—to include adequate provisions to prohibit emissions that either "contribute significantly" to nonattainment or "interfere with maintenance" of federal air quality standards in another state.7

Since the 1990s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the states have implemented various regional programs to address interstate air transport. Many of these programs have since concluded. The current program—the Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR, pronounced "Casper")—is an emissions trading program for 28 states in the eastern part of the United States. EPA established CSAPR to limit interstate transport of power sector SO2 and NOx emissions and help states comply with the 1997 and 2006 PM2.5 standards as well as the 1997 and 2008 ozone standards.

EPA has attributed emission reductions to CSAPR and the agency's other emissions trading programs, such as the Acid Rain Program: annual SO2 emissions from power plants participating in CSAPR were 1.2 million tons in 2016, an 87% reduction from 2005 levels.8 CSAPR power plants also emitted 420,000 tons of NOx in the 2016 ozone season, roughly an 80% reduction from the 1990 ozone season NOx emissions.9

Emissions reduction progress notwithstanding, some areas of the country do not meet federal air quality standards for pollutants like ozone and particulate matter. In 2018, EPA designated 52 areas with approximately 200 counties or partial counties as "nonattainment" with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.10

Members of Congress representing both downwind and upwind states may have an interest in how EPA and states implement the CAA's Good Neighbor provision, particularly as states begin to develop plans for nonattainment areas to come into compliance with the 2015 ozone standards. Some downwind states with nonattainment areas have attributed their ozone violations—at least in part—to emission sources from upwind states.11 Downwind states have also expressed concerns that transported air pollution contributes to harmful human health impacts and adversely affects economic growth.12 For example, a Maryland state agency reported that transport of emissions from upwind states has required Maryland's sources to compensate with "deeper in-state emissions reductions," thereby adding economic costs to the state's business community.13 Upwind states have disagreed with the approach used by EPA to determine whether emissions from upwind sources contribute to downwind air quality problems. For instance, Ohio's state environmental agency described EPA's transport approach as "deeply flawed," concluding that it would place "an unfair amount of responsibility" on upwind power plants to reduce emissions.14

To assist Members and staff in understanding interstate transport issues, this report presents background information about the CAA's interstate transport provision, provides a brief history of regional programs leading up to CSAPR, discusses key aspects of the CSAPR program and program results, summarizes the status of Good Neighbor determinations with respect to ozone standards, and concludes with issues for congressional consideration.

Background

The CAA requires EPA to establish national standards for air pollutants that meet the criteria in Section 108(a)(1). These pollutants—the "criteria pollutants"—are those that EPA has determined "may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare" and whose presence in "ambient air results from numerous or diverse mobile or stationary sources."15 EPA must design two types of National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for the criteria pollutants. Primary NAAQS must protect public health with an "adequate margin of safety," and secondary NAAQS must "protect public welfare from any known or anticipated adverse effects."16 The NAAQS are concentration standards measured in parts per million (ppm) by volume, parts per billion (ppb) by volume, and micrograms per cubic meter of air (µg/m3).17 The NAAQS do not set direct limits on emissions but rather define what EPA considers to be clean air for the pollutant in question.18

Section 109(d) of the act requires periodic NAAQS reviews. Every five years, EPA must review the NAAQS and the science upon which the NAAQS are based and then revise the NAAQS if necessary. This multi-step process is rarely completed within the five-year review cycle and is often the subject of litigation that results in court-ordered deadlines for completion of NAAQS reviews.19 Since January 1997, EPA has completed at least one review for each of the six criteria pollutants (carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide), with standards being made more stringent for five of the six.20 Most of the revisions finalized in this time period were for the ozone and particulate matter standards.21

The CAA assigns responsibility to states to establish procedures to attain and maintain the NAAQS within their borders. In particular, the act requires each state to submit a new or revised state implementation plan (SIP) to EPA within three years of a NAAQS promulgation or revision.22 This SIP submission, also known as an "infrastructure SIP," outlines how the state will implement, maintain, and enforce the NAAQS.23 The infrastructure SIP allows EPA to "review the basic structural requirements of [a state's] air quality management program in light of each new or revised NAAQS."24 Examples of the basic structural requirements include enforceable emission limits, an air monitoring program, an enforcement program, air quality modeling capabilities, and "adequate personnel, resources, and legal authority."25

The state's SIP must also address its interstate transport obligations under the CCAA. EPA refers to this section of the SIP submission as the "Good Neighbor SIP." The Good Neighbor SIP must prohibit "certain emissions of air pollutants because of the impact they would have on air quality in other states."26 Specifically, the state's Good Neighbor SIP must prohibit sources in that state from "emitting any air pollutant in amounts which will … contribute significantly to nonattainment in, or interfere with maintenance" of a NAAQS in another state.27

EPA reviews SIPs to ensure they meet statutory requirements. The agency also has authority to require states to revise their SIPs. Furthermore, the act requires EPA, under certain conditions, to impose sanctions and to issue a Federal Implementation Plan (FIP) if a state fails or declines to submit or implement an adequate SIP.28

Recognizing ongoing challenges with ozone transport, the 1990 CAA Amendments established regional planning provisions specific to ozone. For example, CAA Section 184 created a multi-state ozone transport region, known as the Ozone Transport Region (OTR), and established the northeast Ozone Transport Commission (OTC) to advise EPA about ozone controls in the OTR.29 The OTR is comprised of 12 Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, certain counties in Northern Virginia) and Washington, DC.30 The CAA required states in the OTR to impose controls on sources in all specified areas, regardless of attainment status. Such controls included enhanced vehicle inspection and maintenance programs and reasonably available control technology for sources of VOCs.31

In addition, CAA Section 176A allows EPA to establish transport regions to address regional pollution problems contributing to violations of a primary NAAQS. The agency must establish a commission, comprised of EPA and state officials, for each transport region that makes recommendations to EPA on appropriate mitigation strategies.

Implementing the Good Neighbor Provision

The CAA provides two independent statutory authorities to facilitate compliance with the Good Neighbor provision: (1) the SIPs process under Section 110 and (2) a petition process under Section 126(b). While these authorities are separate, they each address the same objective—that is, the Good Neighbor provision in Section 110(a)(2)(D)(i).32 The remainder of this section describes how these authorities may be used to enforce the Good Neighbor provision.

SIPs Process

As previously noted, a state's SIP must prohibit sources in that state from "emitting any air pollutant in amounts which will … contribute significantly to nonattainment in, or interfere with maintenance" of a NAAQS in another state.33 If EPA finds an existing SIP inadequate, it must require the state to revise the SIP.34 This procedure is known as a "SIP call" and it can be issued to multiple states at the same time. Specifically, EPA must issue a SIP call whenever the agency determines that the SIP is "substantially inadequate to attain or maintain" a particular NAAQS, to ensure that the state's sources do not contribute significantly to a downwind state's nonattainment, or if it is otherwise inadequate to meet any CAA requirement.35 EPA can also issue a SIP call if states do not meet the CAA Section 184 requirements of the OTR.

Section 126(b) Petitions

Under CAA Section 126(b), any state or political subdivision can petition EPA to issue a "finding that any major source or group of stationary sources emits or would emit any air pollutant in violation" of the Good Neighbor provision.36 Section 126(b) requires EPA to make a decision within 60 days. If EPA grants the petition, the sources identified in the petition must cease operations within three months unless they comply with emission controls and compliance schedules set by EPA.

While Section 126(b) and a SIP call each enforce the Good Neighbor provision, they differ in their implementation.37 First, a state or political subdivision must initiate the 126(b) petition, whereas EPA initiates the SIP call. Second, unlike a SIP call, the 126(b) petition is limited to a "major source or group of stationary sources" and cannot be used to address minor or mobile sources.38 Third, EPA may directly regulate upwind sources when it grants a 126(b) petition, whereas a SIP call results in direct EPA regulation only if EPA issues a FIP in response to a state's failure to respond adequately to the SIP call.

EPA's review of 126(b) petitions has sometimes coincided with the agency's SIP call process. For example, in 1998, EPA coordinated its review of eight 126(b) petitions when it promulgated a SIP call. EPA acknowledged the distinction between the CAA authorities for the 126(b) petition process and the SIP call but coordinated the two actions because they were both designed to reduce ozone transport in the eastern United States.39

States have also submitted 126(b) petitions ahead of the deadlines for Good Neighbor SIPs.40 For example, in 2011, EPA granted a 126(b) petition from New Jersey, finding that a coal-fired generating station in Pennsylvania contributed significantly to nonattainment with the SO2 NAAQS in New Jersey.41 Some considered EPA's approval of this petition to reflect a more expansive interpretation of Section 126 in which 126(b) petitions are not necessarily limited to the time frame of Good Neighbor SIP updates.42 Whereas EPA had previously considered 126(b) petitions several years after revising a NAAQS—and after making attainment and nonattainment designations for revised standards—EPA approved New Jersey's 126(b) petition before Pennsylvania was required to complete its Good Neighbor SIP for the 2010 revision to the SO2 NAAQS.43 EPA promulgated an emissions limit for the generating station that would reduce its SO2 emissions by 81% and set a compliance deadline of three years.44 In 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit upheld EPA's interpretation of Section 126, concluding that the CAA allows EPA to make a Section 126 finding independently of the Section 110 SIP process.45

States have continued to submit Section 126(b) petitions related to ozone interstate transport. For example, Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, and New York have submitted 126(b) petitions related to compliance with the 2008 and/or 2015 ozone NAAQS.46 As of July 2018, EPA has denied the petition from Connecticut and has proposed to deny petitions from Delaware and Maryland.47 Among the various reasons for denying Connecticut's petition, EPA found that the petition did not reflect current operations at the named source—a power plant located in Pennsylvania.48 In particular, EPA stated that the air quality modeling in Connecticut's petition was based on 2011 emissions data and therefore did not account for subsequent NOx reductions, noting that the named source "primarily burned natural gas with a low NOx emission rate in the 2017 ozone season."49 In addition, EPA conducted its own analysis using the agency's current multi-step framework for determining what constitutes a significant contribution.50 The agency's analysis did not identify additional "highly cost-effective controls available at the source and thus no basis to determine that [the named source] emits or would emit in violation of the good neighbor provision with respect to the 2008 ozone NAAQS."51 While EPA "expects the facility to continue operating primarily by burning natural gas in future ozone seasons,"52 others have expressed concern that there is no "enforceable requirement prohibiting" the named source from switching back to coal.53

Similarly, in June 2018, EPA proposed to deny petitions from Delaware and Maryland, in part because EPA found "several elements of the states' analyses … insufficient to support the states' conclusions."54 For example, EPA said that Delaware's petitions did "not provide any analysis indicating that Delaware may be violating or have difficulty maintaining the 2008 or 2015 ozone NAAQS in a future year associated with the relevant attainment dates."55 EPA also noted that Delaware used 2011 emissions data, which EPA characterized as "generally higher than, and therefore not representative of, current and future projected emissions levels at these [named sources] and in the rest of the region."56 Delaware has disagreed with EPA's proposed denial on various grounds. Among other things, Delaware stated that EPA has not "shown valid modeling or justification that Delaware will attain the 2015 ozone standard by its 2021 Marginal nonattainment deadline."57 In particular, EPA's projections analyzed the year 2023, which is the attainment deadline for areas designated as moderate nonattainment with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.58

Finally, EPA proposed to deny Maryland's petition, in part because the agency disagreed with Maryland that NOx limits for 36 named sources should be based on the respective units' lowest observed emissions rates.59 Specifically, Maryland's petition concluded that the 36 named sources were operating pollution controls "sub-optimally based on a comparison of their lowest observed NOx emissions rates between 2005 and 2008, which Maryland describes as the 'best' observed emissions rates, to emissions rates from the 2015 and 2016 ozone seasons."60 EPA disagreed that the lowest historical NOx emissions rate is representative of "ongoing achievable NOx rates" in part because over time, some NOx controls (e.g., selective catalytic reduction [SCR] systems) "may have some broken-in components and routine maintenance schedules entailing replacement of individual components." EPA stated that in a 2016 rulemaking addressing regional ozone transport, the agency determined that the "third lowest fleetwide average coal-fired [power plant] NOx rate" for power plants using SCR to be "most representative of ongoing, achievable emission rates."61 Maryland has disagreed with EPA's proposed denial, noting that it will "testify in opposition to the proposal and use all available tools, including litigation."62

Interpreting "Significant Contribution"

Enforcement of the CAA's interstate transport provisions hinges on a key test in Section 110(a)(2)(D)(i)—whether one state "significantly contributes" to a violation of the NAAQS in another state. The CAA does not, however, define what constitutes a significant contribution. Instead, this phrase has been interpreted through EPA rulemakings addressing interstate air pollution. The agency's interpretation has been contentious at times, given that it "inherently involves a decision on how much emissions control responsibility should be assigned to upwind states, and how much responsibility should be left to downwind states."63 Stakeholders have challenged the legality of EPA's interpretations over the years.64

The regulatory actions and litigation have led to EPA's establishment of the current framework to address the Good Neighbor provision for ozone and particulate matter.65 The framework establishes a screening threshold—interstate pollution that exceeds 1% of the NAAQS—to identify states with sources that may contribute significantly to air quality problems in downwind states.66 Upwind states that exceed this threshold for interstate pollution are evaluated further—considering cost and air quality factors—to determine whether emission reductions are needed.67 EPA has clarified that it generally uses this framework to determine what constitutes a significant contribution when evaluating Good Neighbor SIPs and when evaluating a 126(b) petition.68 See "Framework to Assess Good Neighbor Provision" for detailed discussion of the framework.

Programs Addressing Interstate Pollution

Pursuant to the CAA, EPA and states have implemented various market-based programs that target regional emissions of SO2 and NOx from power plants. One type of market-based program, known as emissions trading, sets a limit (or "cap") on total emissions within a defined geographic area or economic sector and requires covered entities to surrender an allowance for each unit—typically a ton—of emissions.69 Such programs are also known as "cap-and-trade."

Under an emissions cap, covered entities with relatively low emission-reduction costs have a financial incentive to reduce emissions because they can sell unused allowances to entities that face higher costs to reduce their facility emissions. The requirements vary by each program. For example, policymakers may decide to distribute the emission allowances to covered entities at no cost (based on, for example, previous years' emissions), sell the allowances (e.g., through an auction), or use some combination of these strategies. In addition, some programs may permit covered entities to "bank" or save surplus allowances for future use while others may not.

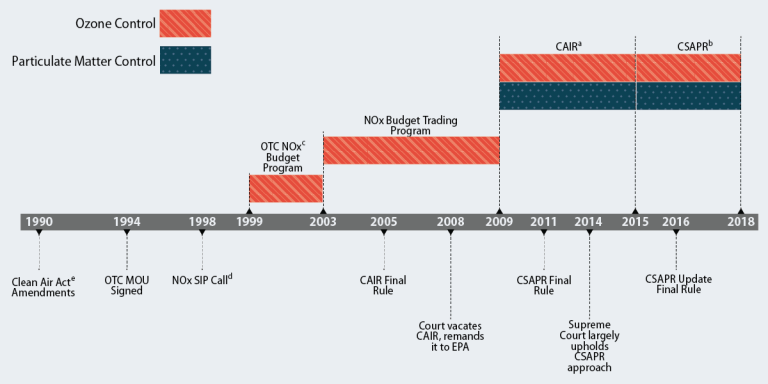

The remainder of this section presents a brief history of the interstate transport programs implemented prior to 2015, given their cumulative impact on regional emission reductions. The "Cross State Air Pollution Rule" section then provides more detail about CSAPR, the current emissions trading program intended to limit interstate transport of power sector SO2 and NOx emissions. Figure 1 summarizes the timeline of the regional programs for ozone and particulate matter control.

Acid Rain Program

EPA established the Acid Rain Program (ARP) under Title IV of the 1990 CAA Amendments to reduce power sector emissions that cause acid rain.70 Specifically, the ARP targets SO2 emissions through cap-and-trade and addressed NOx emissions through an emissions-rate-based program.71 Since its inception over two decades ago, the ARP has achieved notable reductions in these regional pollutants at lower-than-predicted costs. The market-based program also served as the basis for subsequent programs addressing interstate pollution.72

Under Title IV of the CAA, EPA implemented the ARP in two phases. The first phase—1995 to 1999—included 110 high-emitting coal-fired power plants, which had been identified in the statute and spanned 21 eastern and midwestern states.73 The second phase began in 2000 and included more coal-fired power plants as well as those firing oil and natural gas, accounting for nearly all fossil-fueled power plants in the lower 48 states.74 EPA set the annual SO2 emissions cap at 9.97 million allowances in 2000 and decreased it in subsequent years. The ARP remains in effect today. The annual SO2 cap—8.95 million tons of SO2 per year—has not changed since 2010. The annual cap is roughly half of the SO2 emitted by the power sector in 1980.75

EPA distributed SO2 allowances based on statutory formulas and accounted for historical emission rates and fuel consumption.76 The "existing" power plant units—those in operation prior to November 15, 1990—received allowances for free.77 The "new" power plant units—those commencing operations after November 15, 1990—generally did not receive free allowances and had to purchase them on the market.78 At the end of each year, covered power plants have to surrender one allowance for each ton of SO2 emitted. Unused allowances can either be sold or banked for use in later years.79 The market value of unused allowances, therefore, serves as an incentive for power plants to "reduce emissions at the lowest cost."80

The NOx portion of the ARP does not involve cap-and-trade but follows a more traditional regulatory approach. It is implemented through boiler-specific NOx emission rates.81 This program has provided power plants with some compliance flexibility, for example, by allowing the use of emissions rate averaging plans for units under common control, provided they meet certain conditions.82 According to one analysis of the ARP, the NOx portion "helped demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of NOx controls," and by 2000, it "encouraged the installation of advanced NOx combustion controls, such as low-NOx burners, and the development of new power plant designs with lower NOx emission rates."83

While the ARP reduced SO2 and NOx emissions from the power sector, additional reductions were needed to meet ambient air quality standards under the CAA and to address the statute's Good Neighbor provision.84 For example, in 1997, EPA revised the NAAQS for ozone and particulate matter—which are formed by SO2 and NOx—to be more stringent.85 The next sections summarize some of the programs designed to achieve these reductions.

Ozone Control: Regional NOx Programs

Ozone control strategies had focused on VOC emissions until the mid-1990s, when market-based programs began targeting another ozone precursor, NOx, given its "important role … in ozone formation and transport."86 Specifically, two regional trading programs were implemented between 1999 and 2009 to address ozone by reducing NOx emissions. The first one, the "Ozone Transport Commission NOx Budget Program," was in effect between 1999 and 2002. It was then replaced by the second program, the "NOx Budget Trading Program," which ran until 2009.

Ozone Transport Commission NOx Budget Program

The OTC—a multistate organization established under the 1990 CAA Amendments to advise EPA on ozone transport issues—developed the NOx Budget Program and implemented it through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with nearly all of the OTC states.87 The OTC NOx Budget Program set a regional budget (i.e., cap) on NOx emissions from electric utilities and large industrial boilers during the "ozone season" (May through September), which is the time of year weather conditions are most favorable for ozone formation.88 Under the MOU, states "were responsible for adopting regulations, identifying sources, allocating NOx allowances, and ensuring compliance," while EPA was "responsible for approving the states' regulations and tracking allowances and emissions."89

Before emissions trading began under the OTC NOx Budget Program, sources under the ARP were required to meet CAA emission rate standards that were in effect at that time. Sources could not emit above the NOx level expected if using Reasonably Available Control Technology.90 Next, the cap-and-trade program began in 1999 and ran until 2002, at which point the OTC NOx Budget Program was effectively replaced by the NOx Budget Trading Program (see next section).

In 2002, the sources participating in the OTC NOx Budget Program reduced ozone season NOx emissions 60% below 1990 baseline levels.91 Despite the NOx reductions in the Northeast, many northeastern and mid-Atlantic states were unable to meet a statutory deadline to attain the one-hour ozone NAAQS. EPA concluded that these areas had not met this statutory deadline largely because of ozone transport from upwind areas.92

NOx Budget Trading Program

The NOx Budget Trading Program (NBP) effectively replaced the OTC NOx Budget Program and was implemented between 2003 and 2009. The NBP encompassed a wider geographic area than the OTC NOx Budget Program and targeted NOx reductions from electric utilities and nonutility sources (e.g., large industrial boilers).93 EPA established the NBP under the NOx SIP Call, which required a number of eastern and midwestern states, plus the District of Columbia, to revise their SIPs to address regional ozone transport.94 The NOx SIP Call set a NOx ozone season budget for each state and required upwind states to adopt SIPs that would reduce NOx emissions to a level that would meet the budgets.

In the NOx SIP Call, EPA observed that "virtually every nonattainment problem is caused by numerous sources over a wide geographic area," leading the agency to conclude that "the solution to the problem is the implementation over a wide area of controls on many sources, each of which may have a small or unmeasurable ambient impact by itself."95 Ultimately, EPA expected that this would "eliminat[e] the emissions that significantly contribute to nonattainment or interference with maintenance of the ozone NAAQS in downwind states."96

EPA based the NOx SIP Call in part on recommendations from the Ozone Transport Assessment Group (OTAG), a group created by EPA and the 37 easternmost states.97 Of most relevance, OTAG recommended strategies to reduce NOx emissions from utilities as well as large and medium nonutility sources in a trading program.98

EPA accounted for the cost of NOx controls when establishing the NOx budgets.99 EPA identified cost-effective reductions in the electric utility and nonutility source sectors. These control strategies informed the establishment of the NOx emission budgets.100 EPA did not identify cost-effective controls in other sectors—namely, area sources (i.e., nonmobile sources that emit less than 100 tons of NOx per year),101 nonroad engines (i.e., mobile sources that do not operate on roads and highways, such as engines used to power snowmobiles, chainsaws, or lawnmowers),102 or highway vehicles. Under the NOx SIP Call, states could require their sources to comply with the emissions budget or participate in a regional cap-and-trade program. EPA developed a model rule for a regional emissions trading program—known as the NOx Budget Trading Program—to assist states interested in the trading option. All of the jurisdictions—20 states and the District of Columbia—adopted the NBP into their SIPs and participated in the NBP.103

In 2008, NBP emissions were 9% below the 2008 cap, representing a 75% reduction compared to 1990 baseline levels.104 This also represented a 62% reduction below a 2000 baseline, which accounted for emission reductions that occurred under the 1990 CAA Amendments before implementation of the NBP.105

EPA observed that ozone season NOx emissions decreased each year between 2003 and 2008 and attributed these reductions in part to the installation of NOx controls.106 The agency noted that emissions vary year-to-year due to variables such as weather, electricity demand, and fuel costs. For example, EPA attributed the NOx reductions between 2007 and 2008 primarily to lower electricity demand. However, analysis of the entire NBP period—2003 to 2008—shows a reduction in ozone season NOx emissions despite a slight increase in demand for electricity. EPA reported that the average NOx emission rate for the 10 highest electricity demand days (i.e., hot days when use of air conditioning is high) decreased in each year of the NBP. This metric for peak electricity days was 44% lower in 2008 compared to 2003.107

EPA reported that ozone concentrations decreased by 10% between the years 2002 and 2007 across all states participating in the NBP.108 EPA also observed a "strong association between areas with the greatest NOx emission reductions from NBP sources and downwind monitoring sites measuring the greatest improvements in ozone."109 Progress notwithstanding, some NBP areas remained in nonattainment status with the ozone NAAQS as the NBP program concluded by the end of 2008.110

Ozone and PM Control: Regional SO2 and NOx Trading Programs

In 2005, EPA determined that interstate transport of SO2 and NOx contributed significantly to ozone and PM2.5 nonattainment.111 Specifically, EPA found that (1) interstate transport of NOx from 25 states and the District of Columbia contributed significantly to nonattainment, or interfered with maintenance, of the 1997 eight-hour ozone NAAQS; and (2) interstate transport of SO2 and NOx from 23 states and the District of Columbia contributed significantly to nonattainment, or interfered with maintenance, of the 1997 PM2.5 NAAQS.112 To address these findings, EPA promulgated a rule that applied to 28 eastern states and the District of Columbia.113 This rulemaking is known as the Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR).

A legal challenge, however, vacated and remanded CAIR to EPA.114 CAIR remained in effect while EPA responded to the court decision and developed a new regional program addressing air transport, known as CSAPR. CSAPR replaced CAIR on January 1, 2015, and remains in effect today.115 The remainder of this section discusses each program in turn.

Clean Air Interstate Rule

CAIR established a regional cap-and-trade program to reduce power sector SO2 and NOx emissions. Specifically, CAIR established emission budgets for each of the 28 states as well as a model rule for a multi-state cap-and-trade program in the power sector.116 Under CAIR, states could achieve their emission budgets by requiring their sources to participate in the cap-and-trade program.

CAIR set three emissions caps: Two were annual emissions caps to limit SO2 and NOx as precursor emissions to PM2.5, and the third was an ozone season cap limiting NOx as a precursor emission to ozone. The annual NOx and seasonal NOx caps were implemented as the "CAIR NOx annual" and "CAIR ozone season NOx" programs, respectively, in 2009. The SO2 emissions cap was implemented as the "CAIR SO2 annual" program in 2010.117

The scope of CAIR differed from prior NOx trading programs. Whereas the NBP had included both electric generators and nonutility industrial sources (e.g., boilers and turbines), CAIR focused only on electric generators. As previously noted, OTAG's recommendations for the NOx SIP Call included NOx controls for medium and large nonutility stationary sources as well as electric generating units. While nonutility sources emit both NOx and SO2, EPA did not require NOx and SO2 reductions from these sources under CAIR. EPA concluded that it needed more reliable emissions data and better information about control costs to require reductions from nonutility sources in CAIR. Specifically, EPA stated that it lacked information about the costs to integrate NOx and SO2 controls at nonutility sources and therefore could not determine whether such controls would qualify as "highly cost-effective" under CAIR.118

Some stakeholders disagreed with this conclusion, noting that EPA had cost information from the NOx SIP Call. EPA responded that the geographic scope of the NOx SIP Call differed somewhat from CAIR, and therefore it had limited emissions data about nonutility sources in CAIR states that were outside of the NOx SIP Call. In addition, EPA expected that projected NOx and SO2 emissions from nonutility sources were "significantly lower than projected" emissions from electric generators.119 EPA concluded that states would be better positioned to "make decisions regarding any additional control requirements for [non-utility] sources."120

CAIR was challenged in court. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia concluded that CAIR was flawed, finding among other things that the CAIR trading program did not assure some "measurable" emission reduction in each upwind state.121 The court reasoned that the "[e]missions reduction by the upwind states collectively was not enough to satisfy Section 110(a)(2)(D)."122 The court ultimately remanded CAIR to EPA in December 2008, allowing CAIR to remain in effect while EPA developed a replacement rule.123 The CAIR programs for NOx (annual and ozone season) began in 2009 and the CAIR SO2 program began in 2010. The programs continued through the end of 2014.124

Cross State Air Pollution Rule

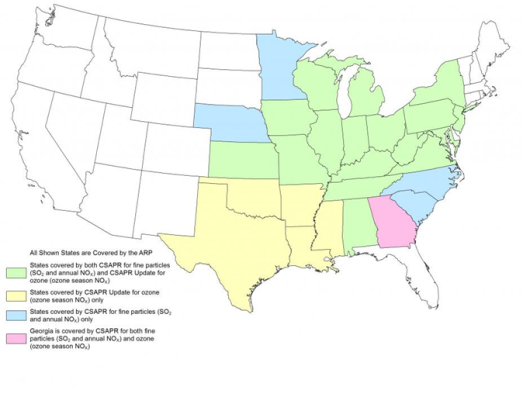

In 2011, EPA promulgated CSAPR to address the court's concerns regarding CAIR.125 CSAPR implementation began in 2015—replacing CAIR—and it remains in effect today. Similar to CAIR, CSAPR aims to reduce ozone and PM2.5 interstate transport. As shown in Figure 2, CSAPR requires 27 states to reduce SO2 emissions, annual NOX emissions, and/or ozone season NOX emissions from the power sector.126 Specifically, CSAPR sets annual SO2, annual NOx, and ozone-season NOx budgets for the covered states and allows states to determine how they will achieve those budgets, including the option of emissions trading.

|

|

Source: EPA (2018), "Map of States Covered by CSAPR," https://www.epa.gov/airmarkets/map-states-covered-csapr. Note: Alaska and Hawaii (not shown) are not covered under the Acid Rain Program (ARP), which applies to power plants in the contiguous United States, nor are they covered under the Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR). |

CSAPR differs from CAIR in other ways, though, and introduced a new approach to measuring a significant contribution under Section 110(a)(2)(D). EPA had previously relied on a regional analysis of significant contributions (e.g., in CAIR and the NOx SIP Call).127 As previously noted, the D.C. Circuit found the regional approach flawed in a ruling on CAIR.128 As a result, EPA used state-specific information under CSAPR to determine significant contributions at the state level. After various legal challenges, the approach used in CSAPR remains in effect today. EPA has determined that it can use this framework to assess the Good Neighbor provision each time it revises the relevant NAAQS.129

Framework to Assess Good Neighbor Provision

EPA developed a multi-step framework to assess states' Good Neighbor obligations and determine each state's significant contribution in CSAPR. First, EPA conducted air quality modeling to project "downwind air quality problems"—that is, it identified downwind monitoring receptors expected to have difficulty attaining or maintaining the NAAQS.130 Next, EPA identified the links between upwind states and the downwind air quality monitoring sites with projected attainment or maintenance difficulties. EPA then identified which of these linked upwind states "contribute at least one percent of the relevant NAAQS" at the downwind sites.131 The agency next assessed the cost-effectiveness of emission control measures and air quality factors to determine whether states exceeding this threshold made significant contributions or interfered with maintenance of a NAAQS in a downwind state. That is, EPA determined that an upwind state contributes significantly to a nonattainment or interference with maintenance of a NAAQS if it produced more than 1% of NAAQS concentration in at least one downwind state and if this pollution could be mitigated using cost-effective measures.

EPA modified the way it considered costs under CSAPR. Whereas EPA had previously based "significant contribution" on the emissions that "could be removed using 'highly cost effective' controls," the agency accounted for both cost and air quality improvement to measure significant contributions under CSAPR.132 In CSAPR, EPA (1) quantified each state's emission reductions available at increasing costs per ton ("cost thresholds"), (2) evaluated the impact of upwind reductions on downwind air quality, and (3) identified the cost thresholds providing "effective emission reductions and downwind air quality improvement."133

The last step of the Good Neighbor assessment framework requires the adoption of "permanent and enforceable measures needed to achieve" the emission reductions.134 EPA implemented this step through its promulgation of FIPs, giving states the option to replace the FIP with a SIP.135 The FIPs specified the emission budgets for each state, reflecting the required SO2 and NOx reductions from power plants in the state, and established the trading programs as each state's remedy to meet the emissions budgets.136

Legal challenges, which eventually reached the Supreme Court, delayed CSAPR implementation.137 The Court largely upheld EPA's approach, holding that EPA's consideration of cost in establishing states' emission budgets was a "permissible construction of the statute."138

CSAPR Emissions Trading Programs

In response to the CAIR litigation, EPA designed "air quality-assured interstate emission trading programs" to implement CSAPR.139 The CSAPR trading programs allow for interstate trading but include provisions meant to ensure that all of the necessary reductions would occur in each individual state. Specifically, EPA stated that the CSAPR assurance provisions "ensure that no state's emissions … exceed that specific state's budget plus the variability limit (i.e., the state's assurance level)."140

EPA established four interstate trading programs for affected power plants under CSAPR: two for annual SO2, one for annual NOX, and one for ozone-season NOX.141 These trading programs aim to help downwind areas attain the 1997 and 2006 annual PM2.5 NAAQS and the 1997 and 2008 ozone NAAQS. The first phase of CSAPR, which began in 2015, sought to address the 1997 and 2006 PM2.5 NAAQS as well as the 1997 ozone NAAQS. The second phase of CSAPR, referred to as the CSAPR Update, began in 2017 and has sought to address the 2008 ozone NAAQS.142

The total emissions budget for each CSAPR trading program equals the sum of the individual state budgets covered by that program. Affected power plants receive an allocation of allowances based on the emission budget for that trading program in the state. Each affected power plant must have an allowance to emit each ton of the relevant pollutant. It may comply with its allowance allocation by using control technologies to reduce emissions—and sell or bank any surplus allowances—or buy more allowances on the market.143

EPA's "CSAPR Update" rulemaking updated the ozone season NOx program with respect to the 2008 ozone NAAQS.144 Specifically, the CSAPR Update promulgated new FIPs for 22 states; 21 of these states were covered in the original CSAPR ozone season NOx trading program.145 The updated ozone season NOx trading began in 2017 and largely replaced the original CSAPR ozone season NOx trading program.146 EPA concluded based on its modeling analysis that emissions from 10 of the states covered in the original CSAPR ozone season NOx trading program "no longer significantly contribute to downwind nonattainment or interference with maintenance" of either the 1997 ozone NAAQS or the 2008 ozone NAAQS.147 Various states and stakeholders have filed a petition for review of the CSPAR Update to the D.C. Circuit.148

CSAPR does not address the Good Neighbor provision with respect to either the 2012 revision to the PM2.5 NAAQS149 or the 2015 revision150 to the ozone NAAQS.151 As of July 2018, states and EPA are in the process of evaluating interstate ozone transport with respect to the 2015 ozone NAAQS (see discussion under "Good Neighbor Determinations and the 2015 Ozone Standard").

Regarding the 2012 PM2.5 standard, a 2016 EPA analysis determined that "few areas in the United States" would "have problems attaining and maintaining the 2012 PM2.5 NAAQS due to the relatively small number and limited geographic scope of projected nonattainment and maintenance receptors."152 EPA concluded that "most states will be able to develop good neighbor SIPs that demonstrate that they do not contribute significantly to nonattainment or interfere with maintenance of the 2012 PM2.5 NAAQS in any downwind state."153 Currently, nine areas are designated nonattainment with the 2012 PM2.5 standard, four of which are located in two CSAPR states (Ohio and Pennsylvania). No areas are currently designated as maintenance with that standard.154

Results of Regional SO2 and NOx Trading Programs

Power sector SO2 and NOx emissions have declined since 2005. EPA has attributed most of these reductions to CAIR, which was in effect through the end of 2014.155 The agency noted that other programs, such as state NOx emission control programs, also contributed to the reductions in annual and ozone season NOx achieved by 2016.156 Figure 3 illustrates the trend of declining emissions, showing that annual SO2, annual NOx, and ozone season NOx decreased between 2009 (the first year of CAIR) and 2016 (the latest year for which the EPA Air Markets Program Data website reports emissions for all three programs).

|

|

Source: EPA Air Markets Program Data, https://ampd.epa.gov/ampd/. Note: CAIR was in effect from 2009 through the end of 2014 and was replaced by CSAPR on January 1, 2015. |

EPA attributed the SO2 reductions under CAIR/CSAPR and the ARP largely to the greater use of pollution control technologies on coal-fired power plant units and "increased generation at natural gas-fired units that emit very little SO2 emissions."157 As noted by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), nearly all SO2 emissions from the electricity sector are associated with coal-fired generation.158 EPA reported that the average SO2 emissions rate for units subject to either the CSAPR or ARP decreased 81% compared to 2005 rates. Most of the reductions were from coal-fired units.159

Analysis from EIA reveals a similar trend at the national level, suggesting that a combination of market and regulatory factors have contributed to SO2 reductions. EIA reported a 73% reduction in national power sector SO2 emissions from 2006 to 2015, which it described as "much larger" than the 32% reduction in coal-fired generation in that same period.160 EIA attributed the national SO2 reductions to (1) changes in the electricity generation mix (e.g., less coal-fired generation and more natural-gas-fired generation), (2) the installation of pollution control technologies at coal- and oil-fired plants (in particular, to comply with the Mercury and Air Toxics rule), and (3) lower use of the most-polluting power plants (e.g., retirements of coal-fired units).161 Another EIA analysis reported that the eastern region of the United States—which includes all of the CSAPR states except Texas—had the largest share of capacity retirements between 2008 and 2017 compared to the rest of the continental United States.162

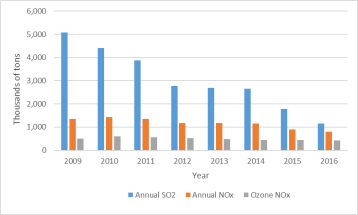

In addition, emissions in 2016 were below the total emission budgets for each CSAPR trading program (see Figure 4).163 EPA observed that this resulted in CSAPR allowance prices at the end of 2016 that "were well below the marginal cost for reductions projected at the time of the final rule [and that such prices] are subject, in part, to downward pressure from the available banks of allowances."164

|

Figure 4. Comparison of CSAPR Emissions Budgets and Actual Emissions in 2016 |

|

|

Source: EPA 2016 Progress Report and EPA Air Markets Program Data, https://ampd.epa.gov/ampd/. |

EPA reported that preliminary data from the 2017 ozone season—the first CSAPR Update compliance period—show that ozone season NOx emissions were below the total emission budget.165

Emission allowance prices are generally affected by a number of factors, including supply and demand, program design elements that influence supply and demand, and legal and regulatory uncertainty.166 Analyses of ozone season NOx highlight summer weather as a key factor (e.g., higher than average temperatures could lead to greater demand for electricity). Power sector compliance strategies (e.g., use of installed control technologies, switching to lower emitting fuels, or retiring higher emitting units) are also relevant to ozone season allowance prices.167

Recent allowance prices in the CSAPR Update trading program appear to be lower than the marginal cost to reduce ozone season NOx emission. One brokerage firm reported that by May 2018—the start of the 2018 ozone season—NOx allowance prices ranged from $150 to $175 per ton, suggesting that the availability of allowance prices at such low prices "could lead to some decisions not to run some pollution controls at maximum output. This would, in turn, lead to higher emissions."168

The brokerage firm reported the marginal cost of ozone season NOx reductions to be about $300 per ton, though EPA considered higher marginal costs to develop the CSPAR Update emission budgets.169 Specifically, EPA considered several cost thresholds—ranging from $800 per ton to $6,400 per ton—and based the CSAPR Update emission budgets on reductions that could be achieved at $1,400 per ton. EPA concluded that a $1,400 per ton threshold would maximize the incremental benefits—the emission reductions and corresponding downwind air quality improvements—compared to other marginal cost thresholds.170 EPA identified NOx control strategies at this cost threshold to include optimizing use of existing operational Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) controls, turning on existing but idled controls—for example, SCR that had not been used for several seasons—and installing advanced combustion controls, such as low-NOx burners.171

EPA has reported improvements in air quality, attributing progress in part to the regional SO2 and NOx transport programs.172 For example, 34 of the 36 areas in the eastern United States that were designated as nonattainment for the 1997 PM2.5 NAAQS now show concentrations below that standard based on 2014-2016 data.173 In terms of ozone, all 92 of the eastern areas originally identified as nonattainment under the 1997 ozone standard now show concentrations below that standard based on 2014-2016 data.174 The 2014-2016 monitoring data also showed that 17 of the 22 areas in the eastern United States that were originally designated as nonattainment with the 2008 ozone standard now have concentrations below that standard.175

Status of Good Neighbor Determinations for Ozone Standards

As previously noted, revisions to the NAAQS trigger the SIPs review process, through which EPA determines whether states have met their Good Neighbor obligations. EPA has not yet finalized its Good Neighbor determinations for either the 2008 revision or the 2015 revision to the ozone standards. The remainder of this section summarizes the status of EPA's Good Neighbor determinations under each standard.

Good Neighbor Determinations and the 2008 Ozone Standard

EPA first sought to address ozone transport with respect to the 2008 ozone standard in the 2016 CSAPR Update. Specifically, the CSAPR Update covered 22 states and promulgated FIPs with ozone season NOx budgets for power plants.176 EPA concluded at the time, however, that it could not determine whether the CSAPR Update fully addressed the Good Neighbor provision with respect to the 2008 ozone standard for 21 of the 22 covered states.177 In other words, the 2016 CSAPR Update "did not fully satisfy the EPA's obligation to address the good neighbor provision requirements" for those 21 states.178 EPA based its 2016 conclusion in part on the agency's projection of air quality problems at downwind monitors in 2017, even with implementation of the CSAPR Update. EPA found that 21 of the 22 CSAPR Update states would contribute "equal to or greater than 1 percent of the 2008 ozone NAAQS" to at least one nonattainment or maintenance monitor in 2017.179

Since then, EPA has updated its air quality modeling and, on June 29, 2018, proposed to determine that the CSAPR Update fully addresses 20 of the 21 remaining Good Neighbor obligations for the 2008 ozone standards.180 As such, the agency has "proposed to determine that it has no outstanding, unfulfilled obligation under Clean Air Act Section 110(c)(1) to establish additional requirements for sources in these states to further reduce transported ozone pollution under" the CAA's Good Neighbor provision with respect to the 2008 ozone NAAQS.181

EPA based its proposed determination on the updated air quality modeling, which projected air quality in 2023—a longer analytical time frame than it used in the CSAPR Update.182 The updated projections showed that in 2023, there would not be any nonattainment or maintenance monitors with respect to the 2008 ozone standard in the eastern United States.183

EPA's selection of a future analytic year is an important factor in the Good Neighbor determination.184 The agency based its selection of 2023 on two primary factors: (1) the downwind attainment deadlines185 and (2) the time frame required to implement emission reductions as "expeditiously as possible."186 As of August 2018, the next attainment dates for the 2008 ozone standard are July 20, 2021 (for areas classified as "Serious" nonattainment) and July 20, 2027 (for areas classified as "Severe" nonattainment).187

The potential to "over-control" emissions was another factor that EPA identified as relevant to the selection of the analytic year. EPA described it as relevant given the agency's expectation that future emissions will decline through implementation of existing local, state, and federal programs and in light of holdings from the U.S. Supreme Court.188 EPA stated that it considered both downwind states' obligation to attain the ozone standards "as expeditiously as possible" and EPA's "obligation to avoid unnecessary over-control of upwind state emissions."189 EPA did not specify whether it expected separate agency actions that may affect ozone precursor emissions—such as changes in the mobile source program—to affect its projections for 2023.

EPA acknowledged that the year it chose—2023—is later than the attainment date for areas classified as "Serious" nonattainment (2008 ozone standard) but concluded that "it is unlikely that emissions control requirements could be promulgated and implemented by the Serious area attainment date."190

The timing of EPA's proposed determination was driven in part by a court order. A federal district court in New York ordered EPA to propose determinations for five states by June 30, 2018, and finalize them by December 6, 2018.191 EPA is under additional court-ordered and statutory deadlines to fully address the Good Neighbor provision with respect to the 2008 ozone standard. For example, another federal district court in California ordered EPA to address the Good Neighbor provision for Kentucky by June 30, 2018.192 EPA is subject to statutory deadlines in 2018 and 2019 to address requirements for eight CSAPR Update states.193

Good Neighbor Determinations and the 2015 Ozone Standard

Evaluation of interstate ozone transport with respect to the 2015 ozone NAAQS is underway. EPA has conducted air quality modeling to inform the development and review of the Good Neighbor SIPs and issued the results in a memorandum in March 2018.194 States have the option to use these modeling results—for example, projections of potential nonattainment and maintenance monitoring sites with respect to the 2015 ozone NAAQS in the year 2023—to develop their Good Neighbor SIPs. States are required to submit Good Neighbor SIPs with respect to the 2015 ozone standard to EPA by October 1, 2018.195 EPA will then evaluate the adequacy of the SIPs and determine whether additional steps are necessary to address ozone transport.

EPA's March 2018 memorandum also identified "potential flexibilities" or "concepts" for developing the Good Neighbor SIPs, describing considerations for each step of the transport framework.196 One of these considerations centered on international ozone contributions. Specifically, EPA seeks feedback on the evaluation of international ozone contributions when determining whether a state significantly contributes to or interferes with maintenance of a NAAQS. This "potential flexibility" might involve developing a "consensus on evaluation of the magnitude of international ozone contributions relative to domestic, anthropogenic ozone contributions" to nonattainment or maintenance receptors and consider whether to weigh the "air quality, cost, or emission reduction factors" differently in areas with relatively high contributions from international sources.197 EPA also invited stakeholders to suggest additional concepts—"including potential EPA actions that could serve as a model"—for the way Good Neighbor obligations are translated to enforceable emissions limits.198

Issues for Congressional Consideration

SO2 and NOx emissions have declined in recent decades, with SO2, annual NOx, and ozone season NOx emissions well below the 2016 CSAPR budgets (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). EPA's analysis suggests that its regional SO2 and NOx programs have reduced interstate transport of PM2.5 and ozone in the eastern United States. EIA's national-scale analysis also points to a combination of broader market and regulatory factors contributing to emission reductions, in particular for SO2.

Going forward, it is not clear whether emissions will remain well below CSAPR budgets given recent low allowance prices for ozone season NOx and the supply of banked allowances that can be used in future years.199 In addition, EPA has not yet issued a determination about whether ozone transport contributes to air quality problems with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.200 The agency has, therefore, not yet determined whether and how it will update the CSAPR budgets with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.

Stakeholder views on interstate air pollution transport vary, generally reflecting disagreements about the level of emissions that should be reduced and which sources—and states—bear responsibility for doing so. Some stakeholders have expressed concern that interstate transport continues to harm air quality.201 For example, some stakeholders have expressed concern about transport of ozone and ozone precursor emissions to downwind states—and the health impacts associated with ozone exposure—and stated that some coal-fired power plants do not make full use of "already-installed pollution controls" to reduce ozone precursor emissions.202 As discussed earlier in this report, EPA has recently denied a 126(b) petition and proposed to deny others from states seeking additional upwind reductions in ozone precursors, in part because the agency disagreed with each state's technical analysis (see "Section 126(b) Petitions").203 Among the stakeholders disagreeing with the agency's rejection of Connecticut's 126(b) petition was a regional organization that raised concern that EPA has not used existing CAA tools to "adequately address interstate ozone transport in a timely manner."204 On the other hand, emissions are below CSAPR budgets, and other stakeholders have questioned the feasibility of additional reductions in ozone precursors. These stakeholders have raised concerns about the extent to which international or natural sources contribute to ambient ozone concentrations.205 The following issues may inform deliberations about interstate air transport, particularly as EPA continues its assessment of Good Neighbor obligations with respect to the 2015 ozone standard.

NOx Emission Trends

Major sources of NOx emissions include power plants, industrial facilities, and mobile sources such as cars and trucks.206 EPA reported that NOx emissions are expected to decline in the future through a "combination of the implementation of existing local, state, and federal emissions reduction programs and changing market conditions for [power] generation technologies and fuels."207 EIA's projections, however, suggest that while coal-fired power generation declines in the reference scenario, power sector NOx emissions remain relatively flat between 2017 and 2050, showing a total decline of 0.2%.208 EPA noted that nonpower-sector sources may be "well-positioned to cost-effectively reduce NOx" emissions compared to the power sector, but the agency also concluded that it has less certainty about nonpower-sector NOx control strategies.209

The extent to which the current collection of federal and state programs—such as CSAPR and EPA mobile source programs that set tailpipe emission standards—improve air quality in areas not meeting the 2015 ozone standard is to be determined.210 In 2015, EPA projected that existing rules (e.g., those addressing automobile emission and fuel economy standards and rules affecting power plants) would reduce ozone precursor emissions, regardless of whether EPA revised the ozone NAAQS.211 EPA has subsequently proposed changes to some of these existing rules—specifically, greenhouse gas emission (GHG) standards for passenger cars and light trucks and existing coal-fired power plants.212 In particular, the proposal for passenger cars and light trucks would freeze fuel economy and GHG standards at model year 2020 levels through model year 2026. The current GHG standards would decrease between model years 2020 and 2025 and were projected to decrease carbon dioxide as well as ozone precursor emissions.213 In terms of power plants, EPA concluded that its Affordable Clean Energy proposal to replace the Clean Power Plan would increase carbon dioxide, SO2, and NOx emissions from the power sector relative to a scenario with implementation of the Clean Power Plan.214 While the agency has not yet finalized these changes, they may have implications for levels of ozone precursor emissions. That is, regulatory changes affecting emissions in one sector—such as automobiles—may affect ozone NAAQS implementation as states seek to ensure the necessary emission reductions are achieved across all sources—mobile and stationary—in the state.

Incentives for NOx Reductions

A recent market report concluded that current NOx allowance prices—which are lower than the marginal cost of NOx reductions—may ultimately lead to higher emissions.215 While EPA has set state-specific emission budgets for CSAPR states intended to address interstate ozone transport with respect to the 2008 ozone standard, it is not clear whether these budgets will be sufficient to address Good Neighbor obligations under the more stringent 2015 ozone standard.

In light of this trend in NOx allowance prices, some have questioned whether additional regulatory incentives may be necessary for states to fulfill Good Neighbor obligations.216 Some states have urged EPA to implement additional regulatory requirements through 126(b) petitions.217 For example, Delaware's 126(b) submission to EPA concluded that "[a]dditional regulatory incentive is required to ensure that the existing [Electric Generating Unit] NOx controls are consistently operated in accordance with good pollution control practices."218

Related EPA Air Quality Initiatives

Current Trump Administration air quality initiatives may indirectly affect consideration of states' Good Neighbor obligations. The Administration has established a "NAAQS Reform" initiative that, among other things, seeks to streamline the NAAQS review process and obtain Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee advice regarding background pollution and potential adverse effects from NAAQS compliance strategies.219 EPA has also created an Ozone Cooperative Compliance Task Force in response to some stakeholders' concerns about international and long-range ozone transport as well as monitoring and modeling issues.220 Limited information is available about the Ozone Cooperative Compliance Task Force and what actions it may undertake.

In March 2018, EPA reiterated its interest in these particular ozone issues when it published air quality projections meant to inform Good Neighbor evaluations with respect to the 2015 ozone standard. Specifically, EPA's memorandum sought comment on "potential flexibilities" for developing the Good Neighbor SIPs, describing considerations for each step of the transport framework, including assessment of international ozone transport.221

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

PM2.5 is also directly emitted by sources (e.g., construction sites, unpaved roads, smokestacks, or fires). See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Particulate Matter (PM) Basics, https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/particulate-matter-pm-basics#main-content. For detailed information about PM and the formation of PM, see National Research Council, Global Sources of Local Pollution: An Assessment of Long-Range Transport of Key Air Pollutants to and from the United States, 2010, pp. 67-76. |

| 2. |

EPA, Basic Information about Ozone, https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution/basic-information-about-ozone. |

| 3. |

EPA, Interstate Air Pollution Transport, https://www.epa.gov/airmarkets/interstate-air-pollution-transport. See also EPA, "Cross-State Air Pollution Rule Update for the 2008 Ozone NAAQS," 81 Federal Register 74514, October 26, 2016; and EPA, Fact Sheet. The Cross-State Air Pollution Rule: Reducing the Interstate Transport of Fine Particulate Matter and Ozone, July 2011, p. 1, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/csaprfactsheet.pdf. |

| 4. |

Michelle S. Bergin et al., "Regional Air Quality: Local and Interstate Impacts of NOx and SO2 Emissions on Ozone and Fine Particulate Matter in the Eastern United States," Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 41, no. 13 (2007), pp. 4677-4689. In addition, EPA summarizes studies about regional transport. See EPA, "Cross-State Air Pollution Rule Update for the 2008 Ozone NAAQS," 81 Federal Register 74514. |

| 5. |

In addition, ground-level ozone is associated with environmental effects, such as negative impacts on forests and crop yields. For information about the health and environmental effects of ozone, see EPA, Basic Information about Ozone; and EPA, Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) of Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants, February 2013, https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=247492. |

| 6. |

EPA, Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM), https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pm. See also EPA, Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter, December 2009, https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=216546. |

| 7. |

CAA §110(a)(2); 42 U.S.C. §7410(a)(2). |

| 8. |

EPA reports emissions reductions achieved under several cap-and-trade programs designed to reduce SO2 and NOx from power plants, including the Acid Rain Program, the Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR), and CSAPR (which replaced CAIR in 2015). EPA reports that most of the SO2 and NOx emission reductions since 2005 occurred in response to CAIR. See EPA, 2016 Program Progress, "Emission Reductions," https://www3.epa.gov/airmarkets/progress/reports/pdfs/2016_full_report.pdf, and "Emission Reductions: SO2 Emission Trends," https://www3.epa.gov/airmarkets/progress/reports/pdfs/2016_full_report.pdf. |

| 9. |

EPA, 2016 Program Progress, "Emission Reductions: Ozone Season NOx Emission Trends." https://www3.epa.gov/airmarkets/progress/reports/pdfs/2016_full_report.pdf. |

| 10. |

On April 30, 2018, EPA designated 51 areas as nonattainment with the 2015 ozone standard. EPA designated one more area as nonattainment on July 17, 2018. For the designations of 51 nonattainment areas, see EPA, "Additional Air Quality Designations for the 2015 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards," 83 Federal Register 25776, June 4, 2018. For the July 2018 designation, see EPA, "Additional Air Quality Designations for the 2015 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards—San Antonio, Texas Area," 83 Federal Register 35136, July 25, 2018. For more information about the 2015 ozone standard and EPA's recent designations, see CRS Report R43092, Implementing EPA's 2015 Ozone Air Quality Standards, by James E. McCarthy and Kate C. Shouse. |

| 11. |

In their recommendations to EPA regarding designation of nonattainment areas, Delaware, New Jersey, and Wisconsin attributed ozone violations in their jurisdiction to emissions transported from other states. See state recommendation letters to EPA, https://www.epa.gov/ozone-designations/2015-ozone-standards-state-recommendations-epa-responses-and-technical-support. |

| 12. |

For example, see U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal et al., letter to Honorable Scott Pruitt, Administrator, EPA, February 23, 2018, https://www.blumenthal.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2018.02.23%20Letter%20to%20Pruitt%20re%20CT%20Clean%20Air%20Act%20Petition.pdf; and U.S. Congress, Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, Subcommittee on Clean Air and Nuclear Safety, Cooperative Federalism Under the Clean Air Act: State Perspectives, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., April 10, 2018. See testimony of Shawn Garvin, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, p. 3, https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/7/9/79fab6e4-ae5d-4e6f-af30-d4cd30d7b3d7/18D52D3F4801CCF26167EC7F17CD4C16.garvin-testimony-04.10.2018.pdf. |

| 13. |

Maryland Department of Environment, "Governor Larry Hogan Announces State Lawsuit Against EPA," press release, September 27, 2017, http://news.maryland.gov/mde/2017/09/27/governor-larry-hogan-announces-state-lawsuit-against-epa/. |

| 14. |

Craig Butler, Director, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, letter to Honorable Gina McCarthy, Administrator, EPA, February 1, 2016, p. 1. See EPA-HQ-OAR-2015-0500-0283 at http://www.regulations.gov. |

| 15. |