Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI): Eligibility, Benefits, and Financing

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is responsible for administering two federal entitlement programs established under the Social Security Act that provide income support to individuals with severe, long-term disabilities: Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSDI is a work-related social insurance program authorized under Title II of the act that provides monthly cash benefits to nonelderly disabled workers and their eligible dependents, provided the workers accrued a sufficient number of earnings credits during their careers in jobs subject to Social Security taxes. In contrast, SSI is a need-based public assistance program authorized under Title XVI of the act that provides monthly cash payments to aged, blind, or disabled individuals (including blind or disabled children) who have limited assets and little or no Social Security or other income. In 2017, SSDI and SSI combined paid an estimated $199 billion in federally administered benefits to 14.5 million qualified disabled individuals and 1.5 million non-disabled dependents of disabled workers.

SSDI is part of the federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, commonly known as Social Security. OASDI benefits are based on an insured worker’s career-average earnings in jobs covered by Social Security and designed to replace a portion of the income lost to a family due to the worker’s retirement, disability, or death. Workers become insured against these events by acquiring a certain number of earnings credits during their careers in covered employment or self-employment. The SSDI component of the program provides benefits to disabled workers who are under Social Security’s full retirement age and to their eligible spouses and children. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component also provides disability benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible disabled survivors of deceased beneficiaries and deceased insured workers. Although these individuals are not technically disability insurance beneficiaries, they are often included in the term SSDI because they receive Social Security benefits due to a qualifying impairment. SSDI and OASI disability benefits are paid from the Social Security trust funds, which are financed primarily by payroll and self-employment taxes levied on the earnings of covered workers.

SSI is a federal assistance program that provides needy aged, blind, or disabled individuals with a guaranteed minimum income to meet their basic living expenses. Although there are no work or contribution requirements to qualify for payments, the program is based on need and therefore is restricted to individuals with limited financial means. SSI is commonly known as a program of “last resort” because claimants must first apply for most other benefits for which they may be eligible; cash assistance is awarded only to those whose assets and other income (if any) are within prescribed limits. The basic federal SSI payment is the same for all recipients and is reduced by the amount of other income that an individual receives. Some states supplement the federal SSI payment with solely state funds. Unlike Social Security, SSI is financed by appropriations from general revenues.

Most claimants are considered disabled for SSDI and SSI eligibility purposes if they are unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to last for at least 12 months or to result in death. In 2018, the SGA earnings limit is $1,180 per month for most individuals. Claimants generally qualify if they have an impairment (or combination of impairments) of such severity that they are unable to perform any kind of substantial work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy, taking into consideration their age, education, and work experience. If a claimant’s application for benefits is denied at any point during the disability determination process, the claimant has the right to appeal the determination or decision.

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI):

Eligibility, Benefits, and Financing

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

- Eligibility Requirements for Disabled Workers

- Disability-Insured Status

- Under the Full Retirement Age (FRA)

- Eligibility Requirements for Dependents and Survivors

- SSDI Spouses

- SSDI Minor Children

- SSDI Student Children

- SSDI Disabled Adult Children

- OASI Disabled Widow(er)s

- OASI Disabled Adult Children

- Termination Events

- Cash Benefits

- Social Security Benefit Formula

- Maximum Family Benefit Limits

- Workers' Compensation and Public Disability Benefit (WC/PDB) Offset

- Average and Total Monthly Benefit Levels

- When SSDI Benefits Start (The Five-Month Waiting Period)

- Exceptions to the Five-Month Waiting Period for Cash Benefits

- Retroactive Benefits

- Medicare

- 24-Month Waiting Period

- Exceptions to the 24-Month Waiting Period

- Financing

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

- Eligibility Requirements

- Categorical Requirements

- Financial Requirements

- Countable Income Limits

- Countable Resource (Asset) Limits

- Deeming of Income and Resources from Certain Close Family Members

- Residency Requirements

- Citizenship Requirements

- Other Requirements

- Termination Events

- Cash Payments

- Federal Benefit Rate (FBR)

- State Supplementary Payments (SSPs)

- Basic Payment Calculation Example

- Gross Income Breakeven Points

- Reduced SSI Payment for Residents of Certain Medical Facilities

- Average and Total Monthly Payment Levels

- When SSI Payments Start

- Medicaid

- 1634 States

- SSI Criteria States

- 209(b) States

- SNAP

- Financing

- Concurrent Disability Beneficiaries

- Definition of Disability

- SSDI and Adult SSI Claimants

- Child SSI Claimants

- Substantial Gainful Activity (SGA) Earnings Limits

- Drug Addiction and Alcohol (DAA)

- Following Prescribed Treatment

- Comparisons with Other Program Definitions of Disability

- Application and Initial Determination Process

- Disability Determinations for SSDI and Adult SSI Claimants

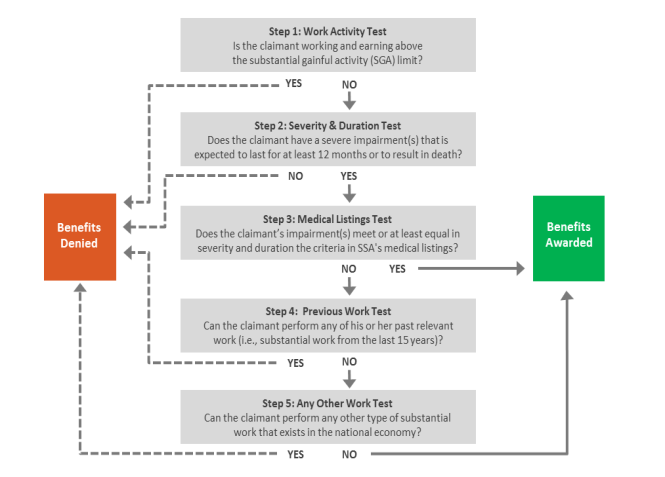

- Step 1. Work Activity Test

- Step 2. Severity and Duration Test

- Step 3. Medical Listings Test

- Step 4. Previous Work Test

- Step 5. Any Work Test

- Disability Determinations for Child SSI Claimants

- Appeals Process

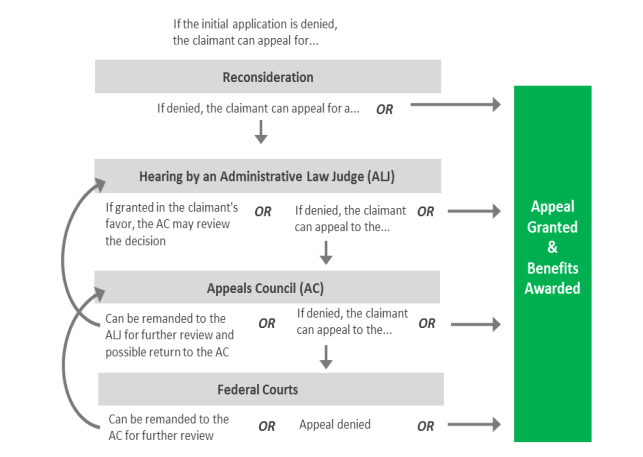

- Step 1. Reconsideration

- Step 2. Hearing Before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ)

- Step 3. Appeals Council (AC)

- Step 4. Federal Courts

- Determinations of Continuing Eligibility

- Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs)

- Age-18 Disability Redeterminations

- Work CDRs

- SSI Redeterminations

Figures

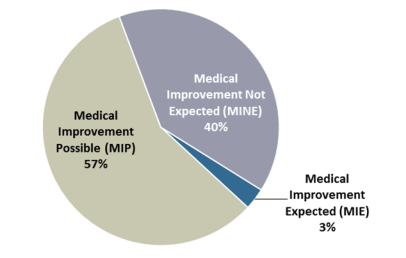

- Figure 1. Social Security Beneficiaries, by Type, December 2017

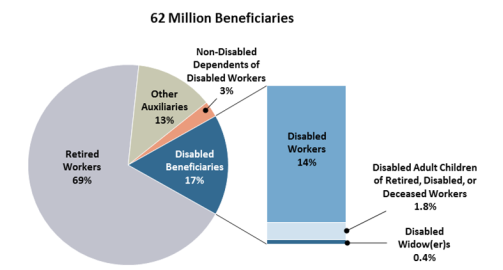

- Figure 2. SSI Recipients, by Eligibility Pathway and Age Group, December 2017

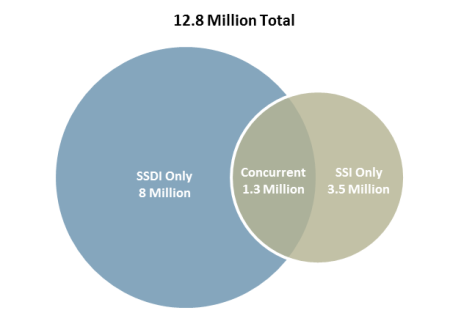

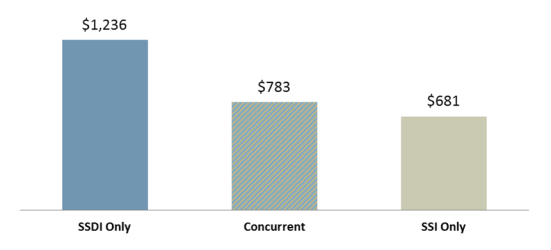

- Figure 3. SSDI Beneficiaries and SSI Disability Recipients Aged 18-64, December 2016

- Figure 4. Average Monthly Benefit Amount for Disability Beneficiaries Aged 18-64, by Type of Disability Beneficiary, December 2016

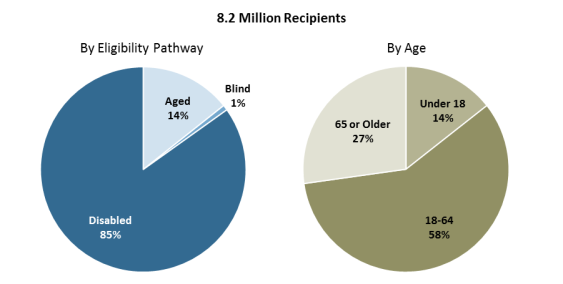

- Figure 5. Initial Disability Determination Process for SSDI and Adult SSI Claimants

- Figure 6. Initial Disability Determination Process for Child SSI Claimants

- Figure 7. Appeals Process

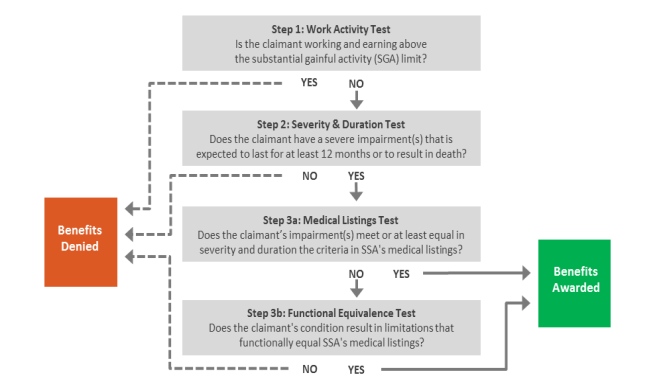

- Figure 8. CDR Diary Classification for SSDI Beneficiaries and SSI Disability Recipients, July 2017

Tables

- Table 1. Number and Share of Disabled Workers Terminated from SSDI and the Annual Termination Rate, by Reason for Termination, 2016

- Table 2. Average and Total Monthly Benefit Amounts of SSDI and OASI Disability Beneficiaries, by Type of Beneficiary, December 2017

- Table 3. Operations of the Social Security Trust Funds, 2017

- Table 4. Number and Share of Nonelderly Blind or Disabled SSI Recipients Terminated and the Annual Termination Rate, by Age Group and Reason for Termination, 2016

- Table 5. Calculating a SSI Payment

- Table 6. Average and Total Monthly Payment Amounts of SSI Recipients, by Type of Payment and Age Group, December 2017

- Table 7. Number of Concurrent Disability Beneficiaries Aged 18-64 and Average Benefit Amount, by Type of SSDI Beneficiary, December 2016

- Table A-1. Comparison of the SSDI and SSI Programs

Summary

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is responsible for administering two federal entitlement programs established under the Social Security Act that provide income support to individuals with severe, long-term disabilities: Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSDI is a work-related social insurance program authorized under Title II of the act that provides monthly cash benefits to nonelderly disabled workers and their eligible dependents, provided the workers accrued a sufficient number of earnings credits during their careers in jobs subject to Social Security taxes. In contrast, SSI is a need-based public assistance program authorized under Title XVI of the act that provides monthly cash payments to aged, blind, or disabled individuals (including blind or disabled children) who have limited assets and little or no Social Security or other income. In 2017, SSDI and SSI combined paid an estimated $199 billion in federally administered benefits to 14.5 million qualified disabled individuals and 1.5 million non-disabled dependents of disabled workers.

SSDI is part of the federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, commonly known as Social Security. OASDI benefits are based on an insured worker's career-average earnings in jobs covered by Social Security and designed to replace a portion of the income lost to a family due to the worker's retirement, disability, or death. Workers become insured against these events by acquiring a certain number of earnings credits during their careers in covered employment or self-employment. The SSDI component of the program provides benefits to disabled workers who are under Social Security's full retirement age and to their eligible spouses and children. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component also provides disability benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible disabled survivors of deceased beneficiaries and deceased insured workers. Although these individuals are not technically disability insurance beneficiaries, they are often included in the term SSDI because they receive Social Security benefits due to a qualifying impairment. SSDI and OASI disability benefits are paid from the Social Security trust funds, which are financed primarily by payroll and self-employment taxes levied on the earnings of covered workers.

SSI is a federal assistance program that provides needy aged, blind, or disabled individuals with a guaranteed minimum income to meet their basic living expenses. Although there are no work or contribution requirements to qualify for payments, the program is based on need and therefore is restricted to individuals with limited financial means. SSI is commonly known as a program of "last resort" because claimants must first apply for most other benefits for which they may be eligible; cash assistance is awarded only to those whose assets and other income (if any) are within prescribed limits. The basic federal SSI payment is the same for all recipients and is reduced by the amount of other income that an individual receives. Some states supplement the federal SSI payment with solely state funds. Unlike Social Security, SSI is financed by appropriations from general revenues.

Most claimants are considered disabled for SSDI and SSI eligibility purposes if they are unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that is expected to last for at least 12 months or to result in death. In 2018, the SGA earnings limit is $1,180 per month for most individuals. Claimants generally qualify if they have an impairment (or combination of impairments) of such severity that they are unable to perform any kind of substantial work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy, taking into consideration their age, education, and work experience. If a claimant's application for benefits is denied at any point during the disability determination process, the claimant has the right to appeal the determination or decision.

Eligibility, Benefits, and Financing

Introduction

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is responsible for administering two federal entitlement programs that provide income support to individuals with severe, long-term disabilities: Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).1 SSDI is a work-related social insurance program that provides monthly cash benefits to nonelderly disabled workers and their eligible dependents, provided the workers accrued a sufficient number of earnings credits during their careers in jobs subject to Social Security taxes. In contrast, SSI is a need-based public assistance program that provides monthly cash payments to aged, blind, or disabled individuals (including blind or disabled children) who have limited assets and little or no Social Security or other income. Both programs use the same basic definition of disability to determine eligibility; however, by virtue of design, each program serves a somewhat different population. In 2017, SSDI and SSI combined paid an estimated $199 billion in federally administered benefits to 14.5 million qualified disabled individuals and 1.5 million non-disabled dependents of disabled workers.2

This report discusses the rules and processes used to determine eligibility for SSDI and SSI. It also explains how benefit amounts are computed, the types of non-cash benefits available to individuals who meet SSA's disability standards, and how each program is financed. For a quick overview of SSDI and SSI, see CRS In Focus IF10506, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and CRS In Focus IF10482, Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI)

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI), commonly known as Social Security, is a federal social insurance program established under Title II of the Social Security Act that provides workers and their families with a measure of protection against the loss of income due to the worker's retirement, disability, or death.3 Workers obtain insurance protection by working for a sufficient number of years in jobs where their earnings are subject to Social Security taxes and therefore are creditable for program purposes. Social Security is financed largely on a pay-as-you-go basis, which means that payroll and self-employment tax contributions from current workers, their employers, and self-employed individuals are used to make monthly benefit payments to today's beneficiaries. In 2017, an estimated 173 million people (or about 94% of all workers) worked in paid employment or self-employment covered by Social Security, and the program paid monthly benefits to approximately 62 million beneficiaries (Figure 1).4

The SSDI component of the program, which was enacted in 1956 and implemented in 1957, provides monthly benefits to statutorily disabled workers who are under Social Security's full retirement age (FRA) and to their eligible spouses, divorced spouses, minor children, student children, and disabled adult children. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component of Social Security also provides benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible survivors of deceased beneficiaries and deceased insured workers. Although these individuals are not technically disability insurance beneficiaries, they are often included in the term SSDI, because they receive Social Security benefits due to a qualifying impairment. In December 2017, the SSDI component of Social Security paid benefits to 10.4 million individuals, including 8.7 million disabled workers and 1.7 million of their dependents.5 That same month, the OASI component paid benefits to 1.2 million OASI disability beneficiaries.6

|

Figure 1. Social Security Beneficiaries, by Type, December 2017 |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), "Benefits Paid by Type of Beneficiary," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/icp.html. Notes: Subtotals may not sum to totals due to rounding. The term other auxiliaries refers to non-disabled dependents and survivors under the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component of the program. |

Eligibility Requirements for Disabled Workers

To qualify for SSDI, disabled workers must (1) be insured in the event of disability, (2) be under Social Security's FRA, (3) have a qualifying impairment (see the "Definition of Disability" section of this report), and (4) have filed an application for benefits.7

Disability-Insured Status

Workers become insured for Social Security by acquiring a certain number of quarters of coverage (QCs) during their careers in paid employment or self-employment covered by Social Security. A worker's job is considered covered if the services performed in that job or net earnings derived by the individual result in wages or net earnings from self-employment income that are taxable and creditable for insured status and benefit computation purposes. In 2018, workers receive one QC for each $1,320 in covered earnings, up to the maximum of four QCs per year, regardless of when the money is earned.8 Thus, if a worker earns $5,280 in covered wages or net earnings from self-employment income during the first week of January 2018, then he or she would be credited with the maximum number of QCs for the calendar year. The amount of earnings needed for one QC is adjusted annually for average earnings growth in the national economy, as measured by SSA's Average Wage Index (AWI).9 Requiring individuals to have earned a certain number of QCs to qualify for cash benefits ensures that such individuals contribute a minimum amount to the insurance system via payroll and self-employment taxes on each QC's worth of covered earnings.

To be insured in the event of disability, known as disability insured, covered workers must be both fully insured for Social Security and meet a recency-of-work requirement. To be fully insured for SSDI, covered workers must have at least one QC for each calendar year after they turned 21 years old and before the year they became disabled.10 The minimum number of QCs for fully insured status is six for the youngest workers (or 1.5 years of covered work); the minimum number of QCs needed for workers aged 62 or older is 40 (or 10 years of covered work). In effect, individuals must have worked in covered employment or self-employment for about a quarter of their adult lives to be fully insured.

To meet the recency-of-work requirement, disabled workers generally need QCs during the 40-quarter period immediately before the onset of the disability.11 In other words, individuals must have worked in covered employment or self-employment for five of the 10 years before becoming disabled. However, workers under 31 years old may meet the recency-of-work requirement with fewer QCs based on their age.12 In 2017, SSDI provided disability insurance coverage to 154 million workers, with about 89% of covered workers aged 21-64 insured for SSDI.13

Under the Full Retirement Age (FRA)

An insured worker must also be under Social Security's FRA to be entitled to SSDI, which for workers born from 1943 through 1954 is age 66.14 FRA is the age at which unreduced Social Security retired-worker benefits are first payable. Upon attaining FRA, disabled workers are automatically transitioned from disabled-worker benefits (or SSDI) to retired-worker benefits (or OASI); however, this change generally does not affect the amount of Social Security benefits paid to them or their dependents. Under current law, Social Security's FRA increases in two-month increments for workers born from 1955 through 1959 until reaching the age of 67 for workers born in 1960 or later. SSDI is not available to workers who have already attained FRA.

Eligibility Requirements for Dependents and Survivors

In addition to the disabled worker's own benefit, SSDI provides benefits to certain family members of the worker. Social Security pays benefits to family members because workers with one or more dependents are presumed to have greater financial need when they retire, become disabled, or die than similarly situated workers who are single. The OASI component also provides benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible survivors of deceased insured workers. The term deceased insured workers includes deceased individuals who received Social Security retired or disabled-worker benefits and non-beneficiary workers who were insured for Social Security at the time of their deaths.

SSDI Spouses

Validly married spouses of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are aged 62 or older or are any age and have an eligible child in their care who is under the age of 16 or disabled, (2) are not entitled to a retired or disabled-worker benefit equal to or larger than the spousal benefit, and (3) have filed an application for benefits.15 Spouses also must have been married to the worker for at least one continuous year immediately before the day on which the claimant's application is filed.16 This provision is known as a duration-of-marriage requirement.

Divorced spouses of disabled workers may qualify if they (1) are aged 62 or older, (2) are unmarried unless the remarriage occurred after attainment of age 60 or age 50 and the claimant was entitled to disabled widow(er)'s benefits, (3) are not entitled to a retired or disabled-worker benefit equal to or larger than the spousal benefit, and (4) have filed an application for benefits.17 Divorced spouses must have been married to the worker for at least 10 years immediately before the date the divorce became final.18

SSDI Minor Children

Eligible minor children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are unmarried, (2) are under the age of 18, and (3) have filed an application for benefits.19 An eligible child is the natural (i.e., biological) child, adopted child, stepchild, equitably adopted child, grandchild, or step-grandchild of the insured worker on whose earnings record the claim is based.20 For certain child claims, such as those involving stepchildren, an explicit dependency requirement must be met, which generally involves the insured worker providing evidence that the child is living with the worker or is receiving at least one-half of his or her support from the worker.21 Otherwise, the child is presumed to be dependent on the insured worker for his or her support. For more information on the rules governing a child's status for purposes of SSDI entitlement, see "GN 00306.001 Determining Status as Child," in SSA's policy manual, the Program Operations Manual System (POMS).22

SSDI Student Children

Eligible student children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are unmarried, (2) are aged 18-19, (3) are a full-time student at an elementary or secondary school, and (4) have filed an application for benefits.23 To be considered a full-time student, the child's scheduled attendance must generally be at the rate of at least 20 hours per week (certain exceptions apply).24 Benefits usually continue until the child graduates or until two months after the child attains the age of 19, whichever occurs first. (Social Security benefits for students aged 18-21 enrolled in post-secondary education [i.e., college] were phased out during the 1980s.)

SSDI Disabled Adult Children

Eligible disabled adult children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are unmarried, (2) are aged 18 or older, (3) have a qualifying impairment that began before they attained the age of 22, and (4) have filed an application for benefits.25 Disabled adult children (DACs) are also called Childhood Disability Beneficiaries (CDB) by SSA. DAC beneficiaries must meet same the disability standard as disabled workers (discussed later in this report). Although DAC beneficiaries must generally be unmarried to be entitled to benefits, the law provides that they may marry other DAC beneficiaries, along with most other types of Social Security beneficiaries.26 This exception does not apply if the marriage was to a minor or student Social Security beneficiary or to a SSI-only recipient.

OASI Disabled Widow(er)s

Disabled surviving spouses of deceased insured workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are at least 50 years of age but not yet 60 years of age, (2) are unmarried unless the remarriage occurred after attainment of age 50 and the claimant was disabled at the time of the remarriage, (3) are not entitled to a retired-worker benefit equal to or larger than the divorced spousal benefit, (4) have a qualifying impairment that began within seven years of the insured worker's death or within seven years of a previous entitlement to such benefits, and (5) have filed an application for benefits.27

The disabled surviving spouse must also have married to the worker for at least nine months. The duration-of-marriage requirement may be waived, however, if the worker was reasonably expected to live for nine months at the time of the marriage and (1) the worker's death was accidental, (2) the worker's death was in the line of duty while he or she was a member of a military serving on active duty, or (3) the claimant was married to the worker for at least nine months as a result of a previous marriage.28 Disabled divorced surviving spouses may qualify if they were married to the deceased insured worker for at least 10 years immediately before the date the divorce became final.29 As with disabled adult children, disabled widow(er)s must meet same the disability standard as disabled workers.

OASI Disabled Adult Children

Eligible disabled adult children of retired or deceased insured workers qualify for benefits if they (1) are unmarried, (2) are aged 18 or older, (3) have a qualifying impairment that began before they attained the age of 22, and (4) have filed an application for benefits.30 (The same provisions governing SSDI DAC beneficiaries also govern OASI DAC beneficiaries.) Unlike most types of Social Security beneficiaries, there is no maximum age limit for disabled adult children. In December 2016, there were 11,260 DAC beneficiaries aged 80 or older, all of whom were dependents or survivors of retired or deceased insured workers.31

Termination Events

In general, disabled workers continue to receive SSDI benefits until they (1) die, (2) attain FRA, (3) no longer meet the statutory definition of disability (i.e., medically improve), or (4) return to work (i.e., have monthly earnings that exceed certain thresholds discussed later in this report). In 2016, the SSDI termination rate—the ratio of disabled-worker terminations to the average number of disabled-worker beneficiaries during the year—was 9.3% (Table 1). The majority of disabled-worker terminations in 2016 were due to attainment of FRA.

Table 1. Number and Share of Disabled Workers Terminated from SSDI and the Annual Termination Rate, by Reason for Termination, 2016

|

Reason for Termination |

Terminations |

Termination Rate |

|

|

Number |

Share |

||

|

Total |

820,372 |

100.0% |

9.3% |

|

Attainment of Full Retirement Age (FRA) |

470,320 |

57.3 |

5.3 |

|

Death of Beneficiary |

251,492 |

30.7 |

2.8 |

|

Return to Work |

47,887 |

5.8 |

0.5 |

|

Medical Improvement |

37,623 |

4.6 |

0.4 |

|

Other |

13,050 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on the following data sources: Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics (ORES), Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2016, October 2017, Table 50, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2016/sect03f.html#table50; and SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), "Benefits Paid by Type of Beneficiary," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/icp.html.

Notes: The term termination rate is the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of disabled-worker beneficiaries during the year. In 2016, the average number of disabled-worker beneficiaries was 8,862,068. The term return to work means that the disabled worker's termination was due to monthly earnings above the substantial gainful activity (SGA) threshold, which in 2016 was $1,130 per month for most workers.

With the exception of certain divorced spouses, receipt of SSDI dependents' benefits is linked to the disabled worker's entitlement to Social Security. If a disabled worker's benefits are terminated, benefits payable on his or her earnings record are also generally terminated. Dependents and survivors who no longer meet the relevant entitlement factors are terminated from the rolls as well.32

Cash Benefits

Social Security Benefit Formula

Initial monthly Social Security benefits are based on an insured worker's creditable, career-average earnings in Social Security-covered employment or self-employment. The Social Security benefit formula is progressive, replacing a greater share of career-average earnings for low-wage or intermittent workers than for high-wage workers. In computing the initial benefit amount, a worker's annual taxable earnings are indexed (i.e., adjusted) to reflect changes in national earnings levels over his or her career, up to the second calendar year before the year of eligibility (i.e., the year a worker attains age 62, becomes disabled, or dies).33 Next, years with the highest earnings in the applicable computation period are summed and then divided over the number of months in that period to produce the worker's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME).34 A formula is then applied to the worker's AIME to compute the primary insurance amount (PIA), which is the worker's basic benefit before any adjustments are made. In 2018, the PIA is determined using the following formula:

- 90% of the first $895 of AIME, plus

- 32% of AIME over $985 and through $5,397 (if any), plus

- 15% of AIME over $5,397 (if any).35

The dollar amounts used in this formula are adjusted annually for average earnings growth in the national economy, as measured by the AWI. The worker's PIA is subsequently adjusted to account for inflation through cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), as measured by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W).36

Spouses and dependent children of disabled workers each receive up to 50% of the worker's basic benefit amount (i.e., the PIA). These supplementary benefits effectively increase the worker's overall replacement rate—the ratio of benefits received to the worker's previous earnings—to account for additional expenses associated with each dependent. Benefits for dependents are less than the worker's own benefit because a family is assumed to have economics of scale.

Disabled widow(er)s receive up to 71.5% of a deceased worker's PIA. Disabled adult children of retired workers receive up to 50% of the worker's PIA, and disabled adult children of deceased insured workers receive up to 75% of the worker's basic benefit. Initial benefits for survivors are higher than benefits for dependents because a family of a deceased worker experiences a complete loss of that worker's earnings, whereas a family of a retired or disabled worker is compensated partially through the worker's own Social Security benefit.

Maximum Family Benefit Limits

Monthly benefits for retired or disabled workers and their eligible family members and for survivors of deceased insured workers are subject to family maximum provisions, which limit the total amount of benefits that can be paid on a worker's earnings record. Therefore, a dependent's or survivor's payable benefit amount may be less than the maximum share of the worker's PIA for that type of benefit. The family maximum for a disabled worker is the smaller of (1) 85% of the worker's AIME (or 100% of the PIA if larger) or (2) 150% of the PIA.37 If the total amount of all family benefits exceeds the maximum amount, then the benefit of each family member (other than the worker) is reduced proportionately. In December 2016, 27% of all disabled-worker families were receiving maximum family benefits.38 A different family maximum formula applies to OASI disability beneficiaries.39

Workers' Compensation and Public Disability Benefit (WC/PDB) Offset

Disabled workers who also receive workers' compensation (WC) or certain other public disability benefits (PDB) may have their SSDI benefits reduced.40 The Social Security Act contains a provision that reduces the SSDI benefits of disabled workers whose combined disability benefits from SSDI and WC/PDB exceed 80% of their average earnings prior to the onset of disability.41 PDBs do not include disability compensation or pension benefits administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), disability benefits based on need (e.g., SSI, state or local general assistance [GA]), disability payments made to public employees based on employment covered by Social Security (except for WC), or wholly private pensions or private disability insurance benefits.42 The purpose of this provision is to reduce the attractiveness of SSDI benefits for concurrently eligible individuals who could otherwise remain in the labor force. The WC/PDB offset no longer applies once the disabled worker attains FRA and converts to retired-worker benefits.43 In 17 states and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the direction of the offset is reversed, resulting in a reduction in the WC or PDB payment instead of the SSDI benefit.44 In December 2016, approximately 5.2% of disabled workers were eligible for WC or PDB payments, and about 1.2% of disabled workers were subject to the WC/PDB offset.45

Average and Total Monthly Benefit Levels

In December 2017, the average monthly SSDI benefit was $1,197 for disabled workers, which on an annualized basis was $14,364 (Table 2).46 The average monthly benefit for SSDI dependents ranged from $335 to $499. That month, SSDI paid out over $11 billion in benefits. For OASI disability beneficiaries, the average benefit that month was $800, and total monthly benefits were $992 million.

Table 2. Average and Total Monthly Benefit Amounts of SSDI and OASI Disability Beneficiaries, by Type of Beneficiary, December 2017

|

Type of Beneficiary |

Number of Beneficiaries |

Average Monthly Benefit |

Estimated Total Monthly Benefits (in thousands) |

|

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) |

|||

|

Disabled Workers |

8,695,475 |

$1,197 |

$10,407,353 |

|

Spouses of Disabled Workers |

126,154 |

335 |

42,315 |

|

Minor Children of Disabled Workers |

1,418,446 |

351 |

497,761 |

|

Student Children of Disabled Workers |

47,920 |

499 |

23,898 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Disabled Workers |

123,257 |

493 |

60,782 |

|

Total |

10,411,252 |

$1,060 |

$11,032,075 |

|

Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) |

|||

|

Disabled Widow(er)s |

258,286 |

729 |

188,404 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Retired Workers |

319,162 |

696 |

222,255 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Deceased Workers |

662,986 |

877 |

581,419 |

|

Total |

1,240,416 |

$800 |

$992,063 |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, OCACT, "Benefits Paid by Type of Beneficiary," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/icp.html.

Notes: Average and total monthly benefit amounts are rounded to the nearest whole dollar. Total monthly benefits are derived by multiplying the number of beneficiaries by the unrounded average benefit amount. These estimates are nearly identical to the rounded total monthly benefit data reported in Table 2 of SSA's "Monthly Statistical Snapshot." Estimated data are used because the snapshot does not provide data for the same beneficiary categories used in this report.

When SSDI Benefits Start (The Five-Month Waiting Period)

For disabled workers47 and disabled widow(er)s,48 entitlement to cash benefits begins five full consecutive calendar months after their disability onset date. This requirement is known as the five-month waiting period. The onset date is the first day that a claimant meets the definition of disability under Title II of the Social Security Act in addition to all relevant entitlement factors. If SSA establishes an onset date after the first day of the month, the five-month waiting period starts on the first day of the following month. For example, if a claimant's onset date were April 11, the waiting period would begin on May 1 and would end on September 30. Benefits would first be payable for the month of October, which is the sixth full month after the disability onset date. Because SSA pays Social Security benefits in the month following the month for which they are due, the individual would receive October's payment on one of several possible payment dates in November (i.e., the seventh month after the onset of disability).49

Exceptions to the Five-Month Waiting Period for Cash Benefits

Disabled adult children are not subject to the five-month waiting period; their entitlement to benefits begins the month after their disability onset date, provided they meet all other entitlement factors.50 In addition, former disabled workers do not have to serve a new waiting period if they become disabled again within 60 months (or five years) after their previous entitlement to cash benefits or period of disability ended.51 A similar provision applies to disabled widow(er)s who become disabled again before age 60, and the new period of disability began within 84 months (or seven years) of the month they were last entitled to disabled-widow(er) benefits.52 Furthermore, disabled widow(er)s may count months of eligibility for SSI or federally administered state supplementary payments (discussed later in this report) toward the five-month waiting period.53 Under current law, there are no exceptions to the five-month waiting period for claimants with specific medical conditions, even those considered terminal.

Retroactive Benefits

SSDI provides retroactive benefits for up to 12 months immediately before the month the disabled worker files an application, provided the worker met all other entitlement factors prior to the filing date. Because of the five-month waiting period for cash benefits, the earliest effective date for a SSDI application can be no more than 17 months before the month in which the application is filed.54 The retroactivity provision was established because an early study of the program found that a large share of claimants did not file for benefits in the first month for which they were eligible. Retroactive benefits should not be confused with past-due benefits, which include both retroactive benefits and benefits owed to claimants for months in which they met all relevant entitlement factors in or after the month of application.

Medicare

In addition to cash benefits, Social Security disability beneficiaries (i.e., disabled workers, disabled widow[er]s, and disabled adult children) qualify for health coverage under Medicare.55 Established under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, Medicare is a federal social insurance program that pays for covered health care services for most individuals aged 65 or older, the majority of Social Security disability beneficiaries and railroad disability annuitants under 65 years old, and certain other individuals who have qualifying impairments.56 (Medicare is not provided to non-disabled dependents under 65 years old.) As with Social Security, workers earn Medicare coverage by working and paying taxes for a sufficient number of years in covered employment or self-employment. For most individuals, entitlement to Medicare is linked to entitlement to Social Security benefits. Social Security disability beneficiaries under 65 years old are provided Medicare because they generally have medical conditions that require significant health care resources. However, many beneficiaries are often unable to work enough to gain health insurance through an employer or to pay for such insurance on their own. In 2013, annual Medicare spending per disabled beneficiary under 65 years old was about $12,776.57

24-Month Waiting Period

Social Security disability beneficiaries under the age of 65 are entitled to Medicare after 24 months of entitlement to cash benefits.58 This requirement is known as the 24-month waiting period. After factoring in the five-month waiting period for cash benefits, disabled workers and disabled widow(er)s typically become entitled to Medicare 29-full calendar months after their disability onset date (i.e., the first day of the 30th full month following disablement). For example, if a claimant's onset date were January 11, 2016, the five-month waiting period for cash benefits would be February 2016 through June 2016, with entitlement to cash benefits beginning July 2016. The claimant would become entitled to Medicare on July 1, 2018, which is the first day of the 25th month of disability benefit entitlement. Disabled adult children are not subject to the five-month waiting period for cash benefits and therefore generally become entitled to Medicare 24 full calendar months after the onset of disability. Due in part to the 24-month waiting period, only 68% of all disabled beneficiaries under 65 years old reported entitlement to Medicare in 2016.59

Exceptions to the 24-Month Waiting Period

General

Social Security disability beneficiaries may count months in which they were previously entitled (or deemed entitled) to cash benefits toward the current Medicare waiting period if their previous entitlement ended within 60 months (or five years) before the month of current onset for disabled workers or 84 months (or seven years) before the month of current onset for disabled widow(er)s and disabled adult children.60 Disability beneficiaries who meet the criteria above and were previously entitled to Medicare do not have to serve a second waiting period for Medicare, because they received cash benefits for at least 24 months during their previous period of disability benefit entitlement and therefore have a sufficient number of months to credit toward the new waiting period. Individuals who become disabled again after the prescribed period may still be able to count months of previous disability benefit entitlement toward the Medicare waiting period if their current impairment is the same, or directly related to, the impairment that served as the basis for disability during a previous period of entitlement.61

In addition, disabled widow(er)s may count months of eligibility for SSI or federally administered state supplementary payments (discussed later in this report) toward the Medicare waiting period.62 It is worth noting that Social Security disability beneficiaries aged 65 or older are entitled to Medicare on the basis of age and thus are not subject to the 24-month waiting period.63

Impairment Related

The Social Security Act specifically excludes disability beneficiaries with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; also known as Lou Gehrig's Disease) from having to satisfy the 24-month waiting period requirement.64 Most disability beneficiaries with ALS become entitled to Medicare the first day of the month that entitlement to cash benefits begins, which for disabled workers and disabled widow(er)s is five full calendar months after the onset of disability.

The Social Security Act also contains separate Medicare entitlement provisions for individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)65 or certain medical conditions caused by exposure to qualifying environmental health hazards,66 meaning that individuals who meet the relevant entitlement factors may enroll in Medicare without having to be entitled (or deemed to be entitled) to Social Security benefits. Neither of these entitlement provisions requires eligible individuals to satisfy a 24-month waiting period requirement, although individuals with ESRD may have to satisfy a three-month waiting period requirement if they are on dialysis and do not self-dialyze on a regular basis.67 Social Security disability beneficiaries who meet the requirements specific to these separate entitlement provisions generally receive Medicare coverage in the month they become entitled to cash benefits.

Financing

Social Security's receipts and outlays are accounted for through two legally distinct trust funds: the Federal Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund and the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund. In the federal accounting structure, a trust fund is an accounting mechanism used by the Department of the Treasury to track and report receipts dedicated for spending on specific purposes, as well as expenditures made to its beneficiaries that are financed by those receipts, in accordance with the terms of a statute that designates the fund as a trust fund. The DI trust fund records receipts and outlays associated with disabled workers and their dependents, and the OASI trust fund records receipts and outlays associated with retired workers and their dependents as well as survivors of deceased insured workers. Administrative costs are also drawn from the trust funds. Each trust fund is a separate account in the U.S. Treasury, and the two funds may not borrow from one another under current law.

Social Security is financed primarily by dedicated payroll and self-employment taxes levied on the earnings of workers in jobs covered by Social Security. Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes are split evenly between employees and employers, while Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) taxes are borne fully by self-employed individuals.68 The overall Social Security payroll tax rate is 12.4% of a worker's earnings (6.2% for employees and employers, each), up to a maximum annual amount, which in 2018 is $128,400.69 Of the 12.4%, 2.37% is allocated to the DI trust fund and 10.03% is allocated to the OASI trust fund.70 The two trust funds are also credited with income from the taxation of a portion of some Social Security benefits71 and from interest earned on special-issue U.S. securities held by the trust funds for years when receipts exceeded outlays.72

In 2017, total receipts to the Social Security trust funds were $997 billion, with $171 billion (or 17%) credited to the DI trust fund (Table 3). That same year, total outlays from the trust funds were $952 billion, with $146 billion (or 15%) coming from the DI trust fund. The trust funds held a combined balance of $2.9 trillion in U.S. securities at the end of 2017, with $71 billion (or 2%) credited to the DI trust fund. In 2017, 98% of the DI trust fund's outlays were for benefit payments, with 1.9% for administrative expenses, and 0.1% for certain transfers.

In their 2017 report and under current law, the Social Security trustees project that the trust funds on a hypothetical combined basis will be able to pay benefits in full and on time until 2034.73 However, as noted earlier, the two trust funds are legally distinct entities. Individually, the trustees project that the DI trust fund will be depleted in 2028 and the OASI trust fund will be depleted in 2035. Upon depletion, the trustees project that continuing revenues to the DI trust fund would be sufficient to pay about 93% of benefits scheduled under law, declining to 82% by 2091.

Under its June 2017 baseline and under current law, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the trust funds on a hypothetical combined basis would be depleted in calendar year (CY) 2030, with the DI trust fund depleted in FY2023 and the OASI trust fund in CY2031.74 Under its April 2018 baseline, CBO now projects that the DI trust fund will be depleted in early FY2025.75 Upon depletion, CBO projects that continuing revenues to the DI trust fund would be sufficient to pay about 88% of benefits scheduled under law.

|

Category |

Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund |

Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund |

Hypothetical Combined OASDI Trust Funds |

|||

|

Receipts |

||||||

|

Payroll Taxes |

|

|

|

|||

|

Income from Taxation of Benefits |

|

|

|

|||

|

Interest |

|

|

|

|||

|

Other Income |

|

|

|

|||

|

Total Receipts |

|

|

|

|||

|

Outlays |

||||||

|

Benefit Payments |

|

|

|

|||

|

Administrative Expenses |

|

|

|

|||

|

Transfers |

|

|

|

|||

|

Total Outlays |

|

|

|

|||

|

Asset Reserves at End of the Year |

|

|

|

|||

Source: CRS, based on SSA, OCACT, "Financial Data for a Selected Time Period," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/allOps.html.

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

Established under Title XVI of the Social Security Act in 1972 and implemented in 1974, SSI is a means-tested federal assistance program that provides monthly cash payments to the needy individuals and couples who are aged, blind, or disabled.76 The program is intended to provide a guaranteed minimum income to adults who have difficulty covering their basic living expenses due to age or disability and who have little or no Social Security or other income. It is also designed to supplement the support and maintenance of needy children who have severe disabilities. SSI is commonly known as a program of "last resort" because claimants must first apply for most other benefits for which they may be eligible; cash assistance is awarded only to those whose assets and other income (if any) are within prescribed limits. The basic federal SSI payment is the same for all recipients and is reduced by most other income that an individual receives. Some states supplement the federal payment using state funds. In December 2017, SSA issued federally administered payments to 8.2 million SSI recipients, including 1.2 million children under 18 years old, 4.8 million adults aged 18-64, and 2.2 million seniors aged 65 or older.77

As shown in Figure 2, the vast majority of SSI recipients enter the program through the disability pathway. In other words, most individuals become eligible for SSI due to a qualifying impairment other than blindness. Blind or disabled SSI recipients who attain age 65 continue to be classified by SSA as blind or disabled, even though they meet the categorical requirements to be classified as aged. To avoid confusion, this report focuses primarily on blind or disabled SSI recipients under 65 years old.

|

Figure 2. SSI Recipients, by Eligibility Pathway and Age Group, December 2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on SSA, "SSI Monthly Statistics, 2017," January 2018, Table 2, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/2017/index.html. Notes: The share of blind SSI recipients is estimated based on 2016 administrative data. See SSA, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics (ORES), SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2016, Table 5, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/. |

Eligibility Requirements

To qualify for SSI, a person must (1) be aged, blind, or disabled as defined in the Social Security Act, (2) have limited income and resources, (3) meet certain other requirements, and (4) have filed an application for payments.78

Categorical Requirements

Public assistance programs usually limit eligibility to certain groups or categories of people who often have difficulty providing for themselves. Under the SSI program, an individual or couple must be aged, blind, or disabled to qualify for payments.79 Aged refers to individuals who are aged 65 or older.80 Blind refers to individuals of any age who have central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of a correcting lens or a limitation in the fields of vision so that the widest diameter of the visual field subtends an angle of 20 degrees or less (i.e., tunnel vision).81 Individuals are considered disabled if they meet SSI's age-specific definition of disability (see the "Definition of Disability" section of this report).

Financial Requirements

In addition to meeting one of the aforementioned categories, an individual or couple must have limited income and other financial resources. Income is defined as anything one receives in cash or in kind that can be used to meet one's needs for food and shelter.82 Resources are cash or other liquid assets or any real or personal property that an individual (or spouse, if any) owns and could convert to cash to be used for his or her support and maintenance.83 Under SSI, a person's countable income and resources must be within the program's statutory limits. Because certain income and resources are disregarded (i.e., not counted), a person may have gross income or resources above the countable limits and still be eligible for the program. In addition to the person's own income and resources, the income and resources of certain ineligible family members (such as a spouse or parent) may be deemed available to meet the needs of the person, and as such, may be included in his or her countable income and resources.

Countable Income Limits

The limit for countable income—gross income minus all applicable exclusions—is equal to the federal benefit rate (FBR), which is the maximum monthly SSI payment available to qualified individuals and couples who have no other income.84 In 2018, the FBR is $750 per month for an individual living in his or her own household and $1,125 per month for a couple living in their own household if both members are SSI eligible.85 The FBR is adjusted annually for inflation by the same COLA applied to Social Security benefits.86 Countable income is subtracted from the FBR in determining eligibility for SSI and the amount of the cash payment. In general, individuals and couples are eligible for SSI if their countable income is less than or equal to the FBR.87 In states that have an agreement with SSA for the agency to administer their state supplementation program (primarily California, Nevada, New Jersey, and Vermont), a person is considered eligible for SSI if his or her countable income is less than the FBR plus the amount of the applicable federally administered state supplementary payment.

Income That is Counted

Under the SSI program, all income is counted unless excluded under federal law or, if provided in statute, at the discretion of the Commissioner of Social Security through agency regulations or subregulatory guidance. SSI classifies income as either earned or unearned. Earned income includes wages, net earnings from self-employment, payments for services performed in a sheltered workshop (now known as a Community Rehabilitation Program [CRP]), and certain royalties and honoraria.88 Unearned income refers to all income that is not earned income (i.e., income not derived from current work), such as Social Security, benefits administered by the VA, unemployment insurance (UI),89 benefits administered by the Railroad Retirement Board (RRB),90 the individual's share of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) grant,91 workers' compensation, public or private pensions, interest income, cash from family or friends, and in-kind support and maintenance (i.e., the value of non-cash benefits such as food or shelter).92

Income That is Not Counted

Certain income is disregarded in determining eligibility for and the amount of assistance provided by SSI.93 For example, the program excludes the following:

- the first $20 per month of any income (earned or unearned), other than unearned income based on need that is totally or partially funded by the federal government or by a non-governmental agency (e.g., TANF);94

- the first $65 per month of earned income plus one-half of any earnings above $65;95

- the first $30 per calendar quarter of infrequent or irregular earned income;96

- the first $60 per calendar quarter of infrequent or irregular unearned income;97

- food assistance provided under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program;98

- energy assistance provided under the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP);99

- housing assistance provided by most federally funded housing programs;100

- federal tax refunds and advanced tax credits, including the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the child tax credit (CTC);101

- assistance based on need that is funded wholly by a state or local entity;102

- the first $2,000 received during a calendar year as compensation for participation in a clinical trial involving research and testing of treatments for a rare disease or condition;103

- impairment-related work expenses (IRWEs) for disabled recipients and blind work expenses (BWEs) for blind recipients;104 and

- any income used to fulfill a plan to achieving self-support (PASS).105

For a more detailed list of unearned income exclusions, see "SI 00830.099 Guide to Unearned Income Exclusions" in POMS.106

The $20 per month general income exclusion and the $65 per month earned income exclusion are not indexed to inflation and have remained at their current levels since the SSI program was enacted in 1972.

Treatment of In-Kind Support and Maintenance (ISM)

SSA defines in-kind support and maintenance (ISM) as food or shelter that a person receives from someone else who pays for it.107 Shelter includes room, rent, mortgage payments, real property taxes, heating fuel, gas, electricity, water, sewerage, and garbage collection services.108 ISM is treated as unearned income subject to special rules based on a person's living arrangement. If a person lives throughout a month in another's household and receives both food and shelter from others living in the household, the FBR is reduced by one third. This reduction is known as the value of the one-third reduction (VTR) and is not rebuttable.109 In 2018, the VTR is $250 per month for an individual ($750 x 1/3) and $375 per month for a couple ($1,125 x 1/3).110 The $20 per month general income exclusion does not apply to ISM reduced under the VTR.

However, if a person receives ISM but does not receive both food and shelter from the household in which the individual lives (either his or her own household or the household of another), then the FBR is reduced by the presumed maximum value (PMV) rule.111 The PMV is a regulatory cap on ISM designed to address situations in which an individual receives ISM but is not subject to the statutory VTR. The reduction under the PMV is equal to one-third of the FBR plus $20, which in 2018 is $270 per month for an individual ($750 x 1/3 + $20) and $395 per month for a couple ($1,125 x 1/3 + $20). Unlike the VTR, the PMV is rebuttable. If the SSI recipient can show that the value of food or shelter received is less than the PMV reduction, then SSA reduces the FBR by the actual value of food or shelter received. Some ISM is disregarded, such as federal housing assistance.112 According to SSA, only about 9% of SSI recipients have ISM reductions.113

Countable Resource (Asset) Limits

The limit for countable resources—gross resources minus all applicable exclusions—is $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple.114 Individuals and couples are eligible for SSI if their countable resources are less than or equal to the applicable statutory limit at any given time.115 Claimants and recipients who transfer (i.e., sell or give away) resources at less than fair market value (FMV) may become ineligible SSI for up to 36 months.116 The look-back period for determining if a transfer was made at less than FMV is also 36 months. Unlike the FBR, the countable resource limits are not adjusted for inflation and have remained at their current levels since 1989.

Resources That Are Counted

As with income, all resources are counted under the SSI program unless excluded federal law or, if provided in statute, at the discretion of the Commissioner of Social Security through agency regulations or subregulatory guidance. The person must have the right, authority, or power to liquidate the property (or his or her share of the property) for the asset to be considered a resource. Countable resources include the following:

- cash retained as of the first moment of the month following the month of receipt;

- bank savings or checking accounts;

- stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and certificates of deposit;

- tractors, boats, machinery, livestock, buildings, and land;

- individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and 401(k) plans under certain conditions;

- unrestricted health savings accounts (HSAs); and

- most types of trusts established with the assets of an individual on or after January 1, 2000.117

Resources That Are Not Counted

Certain resources are excluded in determining SSI eligibility.118 For example, the program excludes the following:

- the person's primary residence;119

- household goods and personal effects;120

- one automobile used for transportation;121

- property essential to self-support (PESS);122

- health flexible spending arrangements (FSAs);123

- resources needed to fulfill a PASS;124

- federal tax refunds and advanced tax credits for a 12-month period;125

- all life insurance policies on a person up to a combined face value of $1,500;126

- up to $1,500 in burial funds set aside for burial expenses of the individual or the individual's spouse;127

- special needs trusts (SNTs) or pooled trusts (PTs) that meet the requirements of Medicaid law;128 and

- the first $100,000 in an Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) account.129

For a more detailed list of resource exclusions, see "SI 01130.050 Guide to Resources Exclusions" in POMS.130

Deeming of Income and Resources from Certain Close Family Members

As a program of "last resort," SSI expects close family members to provide support to low-income aged, blind, and disabled individuals in determining their level of need. Specifically, the income and resources of certain ineligible family members are deemed to be available to meet the basic needs of eligible individuals, and as such, may be included in the individual's countable income or resources for purposes of determining SSI eligibility and the amount of assistance. This process, known as deeming, is used instead of determining the amount of ISM provided by a deemor (i.e., the ineligible family member whose income and resources are subject to deeming) under the VTR or PMV rule. The Social Security Act specifies that deeming applies to the following types of relationships.

- Spouse-to-Spouse. An eligible individual resides in the same household with his or her ineligible spouse.

- Parent-to-Child. An eligible child under 18 years old resides in the same household with his or her ineligible natural (i.e., biological) or adoptive parent(s) or with his or her ineligible natural parent and the spouse of a parent (i.e., a stepparent).

- Sponsor-to-Alien. An eligible alien has a sponsor (usually a relative) who assumes financial responsibility for him of her for purposes of the alien being lawfully admitted to the United States.131

In determining the amount of the deemor's income and resources available to the eligible individual, SSA first applies the basic income and resource exclusions mentioned previously. Next, the agency deducts from the income of the ineligible family member an allocation for his or her living expenses, as well as an allocation for each ineligible child under 18 years old (or under 22 years old and a student) living in the household. This allocation does not apply, however, if the ineligible family member receives public income-maintenance payments, such as TANF or VA pensions based on need.132 In 2018, the allocation is $375 for an ineligible spouse, $375 for each ineligible child, $750 for one ineligible parent, and $1,125 for two ineligible parents. (Different income allocation rules apply to sponsors of aliens.) Finally, SSA charges the remaining countable income of the deemor (if any) to the eligible individual's unearned income and then applies the normal income counting rules to determine SSI eligibility and the amount of the payment. Under deeming, the countable resource limits are $3,000 for an eligible individual with an ineligible spouse, $4,000 for an eligible child with one ineligible parent, $5,000 for an eligible child with two ineligible parents, $2,000 for an alien with an unmarried sponsor, and $3,000 for an alien with a married sponsor.133 For more information on deeming, see Virginia Commonwealth University's National Training and Data Center's page titled, "Understanding the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Program."134

Residency Requirements

To qualify for SSI, individuals or couples must reside in United States, which the program defines as the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.135 People residing in Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, or any other territory or possession of the United State (other than the Northern Mariana Islands) are considered to be residing outside of the United States and thus are ineligible for SSI. However, residents of these territories may become eligible for SSI if they move to one of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, or the Northern Mariana Islands, establish residency there, and meet the physical presence requirement.

|

Cash Assistance for the Aged, Blind, and Disabled in the Territories The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program is not available in Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Instead, these territories continue to operate the joint federal-state programs for the aged, blind, and disabled, which SSI replaced in the 50 states and the District of Columbia in 1974. These programs offer federal funds (up to a specified amount) to the territories in the form of capped categorical matching grants to help pay for the costs of providing cash assistance to needy aged, blind, or disabled adults aged 18 or older. Guam and the U.S. Virgin Islands operate separate programs of Old-Age Assistance (OAA), Aid to the Blind (AB), and Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled (APTD) under Titles I, X, and XIV of the Social Security Act, respectively.136 Puerto Rico operates the consolidated program of Aid to the Aged, Blind, or Disabled (AABD) under Title XVI as it existed prior to reenactment by P.L. 92-603.137 The Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) oversees the matching-grant programs at the federal level. Neither SSI nor the matching-grant programs are available in American Samoa. SSI was extended to the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands as part of its 1976 covenant (P.L. 94-241), effective January 1978. |

Individuals or couples are generally ineligible for SSI for months in which they are not physically present in the United States (as defined above). A person who leaves the United States for 30 consecutive days or more is treated as remaining outside the United States until he or she has returned to and remained in the United States for a period of 30 consecutive days.138 The physical presence requirement does not apply to blind or disabled children of military personnel assigned to permanent duty ashore outside the United States139 or to certain students who are temporarily abroad.140

Citizenship Requirements

In addition to the residency requirement, a person must be a citizen or national of the United States or an eligible noncitizen.141 For the purposes of this report, an eligible noncitizen is an alien who (1) has been granted a qualifying legal status by the federal government (i.e., is a qualified alien) and (2) meets certain other requirements.142 As a result of changes made to federal law under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; P.L. 104-193) as well as legislation enacted shortly thereafter,143 SSI eligibility for noncitizens is limited largely to lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green card holders) with significant past work history in jobs covered by Social Security, "grandfathered aliens" who received SSI when PRWORA was enacted, certain aliens who are exempted by law from PRWORA's requirements, and refugees and asylees.144 Eligible noncitizens do not include aliens who are not authorized to be present in the United States (i.e., "illegal aliens"), nor do they include aliens with certain types of legal (or quasi-legal) status.145 For example, SSI is not available to aliens lawfully admitted to the United States on tourist visas or to beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy.

Eligible noncitizens are often classified into two groups: (1) those without a time limit and (2) those subject to a seven-year limit. Eligible noncitizens without a time limit include, but are not limited to, the following categories:

- LPRs who (1) have satisfied a five-year waiting period requirement from the date of entry and (2) have 40 qualifying quarters of coverage from earnings based on Social Security-covered work (or can be credited with such qualifying quarters from a parent or spouse);

- qualified aliens who are (1) active duty military members, (2) honorably discharged veterans, or (3) the dependents of active duty military members or honorably discharged veterans;

- qualified aliens who are lawfully residing in the United States and were receiving SSI on August 22, 1996;

- qualified aliens who were lawfully residing in the United States on August 22, 1996, and who meet SSI's blindness or disability standard, regardless of the onset date;

- American Indians born in Canada who are admitted to the United States under certain conditions; and

- American Indians who are members of federally-recognized tribes and who meet certain conditions.146

Eligible noncitizens subject to a seven-year limit from the date their status was acquired include, but are not limited to, the following categories:

- refugees and asylees who meet certain conditions;

- Cuban/Haitian entrants and Amerasian immigrants who meet certain conditions;147

- quailed aliens whose deportation is being withheld or whose removal has been withheld (subject to certain conditions);

- Iraqi or Afghan nationals who are admitted to the United States under special immigrant visa (SIV) programs;148 and

- aliens who are deemed to be victims of severe forms of human trafficking and who meet certain other conditions.149

In December 2016, eligible noncitizens made up 6.1% of the total SSI recipient population.150 About 11% of all noncitizen recipients received time-limited payments.151 The average federally administered payment made to all noncitizen recipients that month was $510.152 Roughly 71% of all noncitizen SSI recipients were aged 65 or older, and about 58% of all noncitizen recipients resided in the United States for at least 10 years before applying for SSI.153 Since the enactment of PRWORA, both the number and share of noncitizen SSI recipients has fallen.

Other Requirements

Residents of public institutions (such as a jail, prison, or other facility operated directly or indirectly by a governmental entity) are ineligible for SSI for any month throughout which they reside in such institution.154 In other words, a person is ineligible to receive SSI for any full calendar month in which they are in residence. This requirement does not apply to publicly operated community residences that serve 16 or fewer residents.155 It also does not apply to medical treatment facilities in which more than 50% of the cost of care is paid for by Medicaid or, in the case of a child under 18 years old, by any combination of Medicaid and private health insurance.156 In addition, a person is required to file for all other applicable benefits for which he or she may be eligible.157 Furthermore, a person must not be fleeing to avoid (1) prosecution for certain felonies, (2) custody or confinement after conviction for certain felonies, or (3) recapture because of escape from custody.158 Finally, a person must allow SSA to contact his or her financial institutions for purposes of determining or redetermining eligibility.159

Termination Events

In general, SSI payments are suspended for any month during which a recipient fails to meet the aforementioned eligibility requirements. After 12 consecutive months of payment suspension, most recipients are terminated from the SSI rolls and must file a new application.160 In 2016, the SSI termination rate—the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of SSI recipients during the year for a given age group—was 7.7% for children and 10.0% for working-age adults (Table 4). In 2016, the majority of SSI terminations for children were due to excess income or no longer meeting the applicable definition of disability. For working-age adults that year, most terminations were due to excess income or death.

Table 4. Number and Share of Nonelderly Blind or Disabled SSI Recipients Terminated and the Annual Termination Rate, by Age Group and Reason for Termination, 2016

|

Reason for Termination |

Under 18 Years Old |

Aged 18-64 |

||||||||||||||

|

Terminations |

Termination Rate |

Terminations |

Termination Rate |

|||||||||||||

|

Number |

Share |

Number |

Share |

|||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Excess Income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Whereabouts Unknown |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Excess Resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

In Public Institution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Failed to Furnish Report |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Outside United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

No Longer Disabled |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

Source: CRS, based on the following sources: SSA, ORES, SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2016, November 2017, Table 77, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2016/sect11.html#table77; and SSA, "SSI Monthly Statistics, December 2017," January 2018, Table 2.

Notes: The termination rate is the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of SSI recipients during the year for a given age group. In 2016, the average number of SSI recipients under 18 years old was 1,201,455, and the average number of SSI recipients aged 18-64 was 4,833,829.

Cash Payments

Federal Benefit Rate (FBR)

In 2018, the federal benefit rate (FBR) is $750 per month for an individual living in his or her own household and $1,125 per month for a couple living in their own household.161 On an annualized basis, the FBR in 2018 is $9,000 for an individual and $13,500 for a couple. Individuals and couples with no countable income receive the maximum SSI payment; those with countable income below the applicable FBR have their SSI payment reduced so that their own income plus the reduced SSI payment equals at least the FBR.162 In this way, the FBR acts as an income floor, providing a minimum level of support in 2018 equal to at least 74% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for an individual and 82% of FPL for a couple.163 As noted earlier, the FBR is adjusted annually for inflation by the same COLA applied to Social Security benefits.164 The COLA effective for SSI payments at the start of 2018 was 2.0%, which raised the FBR for an individual from $733 to $750 per month and the FBR for a couple from $1,103 to $1,125 per month.165

State Supplementary Payments (SSPs)

Some states complement federal SSI payments with state supplementary payments (SSPs) that are made solely with state funds.166 SSPs are intended to help individuals whose basic needs are not met fully by the FBR. States may provide SSPs to all SSI recipients, or they may limit payments to certain recipients, such as blind individuals or residents of domiciliary-care homes. Currently, 43 states and the District of Columbia have optional state supplementation programs.167 Most states are required to continue to operate mandatory minimum supplementation programs for certain individuals who were converted to SSI in 1974 from the former federal-state cash assistance programs for the aged, blind, and disabled.168 North Dakota, the Northern Mariana Islands, and West Virginia do not operate any supplementation programs.169