Introduction

This report discusses two federal entitlement programs established under the Social Security Act that provide income support to individuals with severe, long-term disabilities: Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). SSDI is a social insurance program that provides monthly cash benefits to nonelderly workers with disabilities and to their eligible dependents, provided the worker paid Social Security taxes for a sufficient number of years in jobs covered by Social Security.1 In contrast, SSI is a public assistance program that provides monthly cash benefits to seniors and individuals with disabilities (adults and children) who have limited assets and little or no Social Security or other income.2 Both programs are administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA) and use the same basic definition of disability to determine eligibility. However, by virtue of design, each program serves a somewhat different population. In 2016, SSDI and SSI combined paid an estimated $199 billion in federally administered benefits to 14.6 million qualified disabled individuals and 1.6 million non-disabled dependents of disabled workers.3 In discussing individuals who receive cash disability benefits, this report focuses primarily on (1) Social Security disabled-worker beneficiaries under 66 years old and (2) blind or disabled SSI recipients under 65 years old. For a quick overview of SSDI and SSI, see CRS In Focus IF10506, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and CRS In Focus IF10482, Supplemental Security Income (SSI).

Social Security Disability Insurance

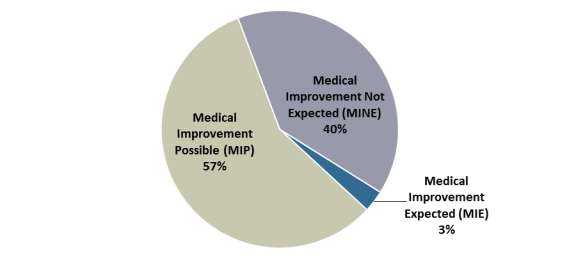

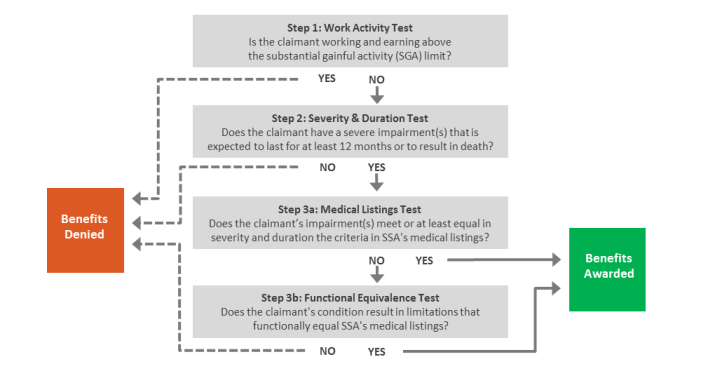

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI), commonly known as Social Security, is a federal social insurance program established under Title II of the Social Security Act that provides workers and their families with a measure of protection against the loss of income due to the worker's retirement, disability, or death.4 Workers obtain insurance protection by working for a sufficient number of years in jobs that are covered by Social Security and thus are taxable and creditable for program purposes. Social Security is financed largely on a pay-as-you-go basis, which means that payroll tax contributions from current workers, their employers, and self-employed individuals are used to make monthly benefit payments to today's beneficiaries. In 2016, an estimated 171 million people (or about 94% of all workers) worked in paid employment or self-employment covered by Social Security, and the program paid monthly benefits to about 61 million beneficiaries, on average (Figure 1).5

|

Figure 1. Social Security Beneficiaries, by Type, December 2016 |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on Social Security Administration (SSA), Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), "Benefits Paid by Type of Beneficiary," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/icp.html. Notes: Subtotals may not sum to 100.0% due to rounding. The term other auxiliaries refers to non-disabled dependents and survivors under the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component of the program. |

The SSDI component of the program, which was established in 1956, provides monthly benefits to statutorily disabled workers who are under Social Security's full retirement age (FRA) and to their eligible spouses, divorced spouses, minor children, student children, and disabled adult children. The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) component of Social Security also provides benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible survivors of deceased beneficiaries and deceased insured workers. Although these individuals are not technically disability insurance beneficiaries, they are often included in the term SSDI beneficiaries, because they receive Social Security benefits due to a qualifying impairment. In December 2016, the SSDI component of Social Security paid benefits to 8.8 million disabled workers and 1.8 million of their dependents.6 That same month, the OASI component paid benefits to 1.2 million OASI disability beneficiaries.

Eligibility Requirements

To qualify for SSDI, disabled workers must

- be insured in the event of disability,

- be under Social Security's FRA,

- have a qualifying impairment (see the "Definition of Disability" section of this report), and

- have filed an application for benefits.7

Disability-Insured Status

Workers become insured for Social Security by acquiring a certain number of credits (i.e., quarters of coverage) during their careers in paid employment or self-employment covered by Social Security. A worker's job is considered covered if the services performed in that job or net earnings derived by the individual result in wages or net self-employment income that are taxable and creditable for insured status and benefit computation purposes. In 2017, workers receive one credit for each $1,300 in covered earnings, up to the maximum of four credits per year, regardless of when the money is earned.8 Thus, if a worker earns $5,200 in covered wages or net self-employment income during the first week of January 2017, then he or she would be credited with the maximum number of credits for the calendar year. The amount of earnings needed for one credit is adjusted annually for average earnings growth in the national economy, as measured by SSA's Average Wage Index (AWI).9 Requiring individuals to have earned a certain number of work credits to qualify for cash benefits ensures that such individuals contribute a minimum amount to the insurance system via payroll taxes on each credit's worth of covered earnings.

To be insured in the event of disability, known as disability insured, covered workers must be both fully insured for Social Security and meet a recency-of-work requirement. To be fully insured for SSDI, covered workers must have at least one credit for each calendar year after they turned 21 years old and before the year they became disabled.10 The minimum number of credits for fully insured status is 6 for the youngest workers (or 1.5 years of covered work); the minimum number of credits needed for workers aged 62 or older is 40 (or 10 years of covered work).11 In effect, individuals must have worked in covered employment or self-employment for about a quarter of their adult lives to be fully insured.

To meet the recency-of-work requirement, disabled workers generally need 20 credits during the 40-credit period immediately before the onset of the disability.12 In other words, individuals must have worked in covered employment or self-employment for 5 of the 10 years before becoming disabled. However, workers under 31 years old may meet the recency-of-work requirement with fewer credits based on their age.13 In 2016, SSDI provided disability insurance coverage to 152 million workers; about 89% of covered workers aged 21-64 were insured for SSDI.14

Age

An insured worker must also be under Social Security's FRA to be entitled to SSDI, which for workers born from 1943 through 1954 is age 66.15 FRA is the age at which unreduced Social Security retired-worker benefits are first payable.16 Upon attaining FRA, disabled workers are automatically transitioned from disabled-worker benefits (or SSDI) to retired-worker benefits (or OASI); however, this change generally does not affect the amount of Social Security benefits paid to them or their dependents. Under current law, Social Security's FRA increases in two-month increments for workers born from 1955 through 1959 until reaching the age of 67 for workers born in 1960 or later. SSDI is not available to workers who have already attained FRA.

Dependents and Survivors

In addition to the disabled worker's own benefit, SSDI provides benefits to certain family members of the worker.

- Spouses. Validly married spouses of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they are (1) aged 62 or older or (2) any age and have an eligible child in their care who is under the age of 16 or disabled.17 Divorced spouses may qualify if they are unmarried, aged 62 or older, and were married to the disabled worker for at least 10 years.18

- Minor Children. Eligible minor children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they are unmarried and under the age of 18.19

- Student Children. Eligible student children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they are unmarried, aged 18-19, and a full-time student at a secondary education or elementary school.20

- Disabled Adult Children. Eligible disabled adult children of disabled workers qualify for benefits if they are unmarried, aged 18 or older, and have a qualifying impairment that began before they attained the age of 22.21

The OASI component also provides benefits to eligible disabled dependents of retired workers and to eligible survivors of deceased insured workers. (The term deceased insured workers includes deceased individuals who received Social Security retired or disabled-worker benefits and non-beneficiary workers who were insured for Social Security at the time of their death.)

- Disabled Widow(er)s. Disabled surviving spouses of deceased insured workers qualify for benefits if they are at least aged 50 but not yet aged 60 and have a qualifying impairment that began within seven years of the insured worker's death or within seven years of a previous entitlement to such benefits. Disabled divorced surviving spouses may qualify if they were married to the deceased insured worker for at least 10 years.22

- Disabled Adult Children. Eligible disabled adult children of retired or deceased insured workers qualify for benefits if they are unmarried, aged 18 or older, and have a qualifying impairment that began before they attained the age of 22.

Social Security pays benefits to family members because workers with one or more dependents are presumed to have greater financial need when they retire, become disabled, or die than similarly situated workers who are single.23

Termination Events

In general, disabled workers continue to receive SSDI benefits until they (1) die, (2) attain FRA, (3) no longer meet the statutory definition of disability (i.e., medically improve), or (4) return to work (i.e., have earnings that exceed certain thresholds). In 2015, the SSDI termination rate—the ratio of disabled-worker terminations to the average number of disabled-worker beneficiaries during the year—was 9.0%. As shown in Table 1, the majority of disabled-worker terminations in 2015 were due to attainment of FRA.

Table 1. Number of Disabled Workers Terminated from SSDI and the Annual Termination Rate, by Reason for Termination, 2015

|

Reason for Termination |

Number of |

Termination Ratea |

|

Total |

802,501 |

9.0% |

|

Attainment of Full Retirement Age (FRA) |

460,720 |

5.2% |

|

Death of Beneficiary |

255,152 |

2.9% |

|

Return to Workb |

39,652 |

0.4% |

|

Medical Improvement |

35,403 |

0.4% |

|

Other |

11,574 |

0.1% |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), based on Social Security Administration (SSA), Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program, 2015, October 2016, Table 50, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2015/sect03f.html#table50.

a. The term termination rate is the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of disabled-worker beneficiaries during the year, which in 2015 was 8,930,360.

With the exception of certain divorced spouses, receipt of SSDI dependents' benefits is linked to the disabled worker's entitlement to Social Security. If a disabled worker's benefits are terminated, benefits payable on his or her earnings record are also generally terminated. Dependents and survivors who no longer meet the relevant entitlement factors are terminated from the rolls as well.

Cash Benefits

Initial monthly Social Security benefits are based on an insured worker's creditable, career-average earnings in Social Security-covered employment or self-employment. The Social Security benefit formula is progressive, replacing a greater share of career-average earnings for low-wage or intermittent workers than for high-wage workers. In computing the initial benefit amount, a worker's annual taxable earnings are indexed (i.e., adjusted) to reflect changes in national earnings levels over his or her career, up to the second calendar year before the year of eligibility (i.e., the year a worker attains age 62, becomes disabled, or dies).24 Next, years with the highest earnings in the applicable computation period are summed and then divided over the number of months in that period to produce the worker's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME).25 A formula is then applied to the worker's AIME to compute the primary insurance amount (PIA), which is the worker's basic benefit before any adjustments are made. For insured workers who attain age 62, become disabled, or die in 2017, the PIA is determined as follows (Table 2):

Table 2. Social Security Benefit Formula for Workers Who Attain Age 62, Become Disabled, or Die in 2017

|

Factor |

Portion of Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) |

|

90% |

of the first $885, plus |

|

32% |

of AIME over $885 and through $5,336, plus |

|

15% |

of AIME over $5,336 |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT), "Benefit Formula Bend Points," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/bendpoints.html.

The worker's PIA is subsequently adjusted to account for inflation through cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), as measured by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W).26 SSDI benefits may be reduced if the disabled worker concurrently receives state workers' compensation (WC), certain other public disability benefits (PDB), or certain pensions based on earnings from non-covered work.27 In December 2016, the average monthly SSDI benefit was about $1,171 for disabled workers, which on an annualized basis was about $14,054 (Table 3).28

Table 3. Number of SSDI and OASI Disability Beneficiaries and Average Benefit Amount, by Type of Beneficiary, December 2016

|

Type of Beneficiary |

Number of Beneficiaries |

Average Monthly Benefit |

Annualized Benefit |

|

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) |

|||

|

Disabled Workers |

8,808,736 |

$1,171.15 |

$14,053.80 |

|

Spouses of Disabled Workers |

134,680 |

$323.98 |

$3,887.76 |

|

Minor Children of Disabled Workers (Under Age 18) |

1,493,476 |

$340.38 |

$4,084.56 |

|

Student Children of Disabled Workers (Aged 18-19) |

50,976 |

$487.71 |

$5,852.52 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Disabled Workers |

122,202 |

$483.08 |

$5,796.96 |

|

Total |

10,610,070 |

$1,032.25 |

$12,387.00 |

|

Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) |

|||

|

Disabled Widow(er)s |

259,207 |

$717.65 |

$8,611.80 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Retired Workers |

308,529 |

$676.67 |

$8,120.04 |

|

Disabled Adult Children of Deceased Workers |

654,531 |

$854.08 |

$10,248.96 |

|

Total |

1,222,267 |

$780.36 |

$9,364.38 |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, OCACT, "Benefits Paid by Type of Beneficiary," https://www.ssa.gov/oact/ProgData/icp.html.

Spouses and dependent children of disabled workers each receive up to 50% of the worker's basic benefit amount (i.e., the PIA). These supplementary benefits effectively increase the worker's overall replacement rate—the ratio of benefits received to the worker's previous earnings—to account for additional expenses associated with each dependent. Benefits for dependents are less than the worker's own benefit because a family is assumed to have economics of scale. Disabled widow(er)s receive up to 71.5% of a deceased worker's PIA. Disabled adult children of retired workers receive up to 50% of the worker's PIA, and disabled adult children of deceased insured workers receive up to 75% of the worker's basic benefit. Initial benefits for survivors are higher than benefits for dependents because a family of a deceased worker experiences a complete loss of that worker's earnings, whereas a family of a retired or disabled worker is compensated partially through the worker's own Social Security benefit.29

Monthly benefits for retired or disabled workers and their eligible family members and for survivors of deceased insured workers are subject to family maximum provisions, which limit the total amount of benefits that can be paid on a worker's earnings record.30 Therefore, a dependent's or survivor's payable benefit amount may be less than the maximum share of the worker's PIA for that type of benefit. If the total amount of all family benefits exceeds this maximum amount, then the benefit of each family member (other than the worker) is reduced proportionately. Certain reductions to the worker's benefit affect the dependent's or survivor's benefit amount.

Five-Month Waiting Period for Benefits

For disabled workers and their family members, entitlement to cash benefits begins five full consecutive calendar months after the worker's disability onset date.31 This requirement is known as the five-month waiting period and applies to both disabled workers and widow(er)s but not to disabled adult children.32 The onset date is the first day that a claimant meets the definition of disability under Title II of the Social Security Act in addition to all relevant entitlement factors.

Retroactive Benefits

SSDI provides retroactive benefits for up to 12 months immediately before the month the disabled worker files an application, provided the worker met all other entitlement factors prior to the filing date. Because of the five-month waiting period for cash benefits, the earliest effective date for a SSDI application can be no more than 17 months before the month in which the application is filed. (Retroactive benefits should not be confused with past-due benefits, which include both retroactive benefits and benefits owed to claimants for months in which they met all relevant entitlement factors in or after the month of application.)

Taxation of Social Security Benefits

Social Security beneficiaries may have to pay federal income tax on their benefits.33 Up to 85% of Social Security benefits can be included in taxable income for beneficiaries whose provisional income exceeds certain statutory thresholds (based on marital and filing status).34 Provisional income equals adjusted gross income, plus certain otherwise tax-exempt income, plus the addition (or adding back) of certain income specifically excluded from federal income taxation, plus 50% of Social Security benefits. About half of all Social Security beneficiaries pay tax on some of their benefits, but a smaller share of SSDI beneficiaries pay tax on their benefits, because they tend to have little income outside of their Social Security benefits.35

Medicare

In addition to cash benefits, Social Security disability beneficiaries (i.e., disabled workers, disabled widow[er]s, and disabled adult children) qualify for health coverage under Medicare.36 Established under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, Medicare is a federal social insurance program that pays for covered health care services for most individuals aged 65 or older, the majority of Social Security disability beneficiaries and railroad disability annuitants under 65 years old, and certain other individuals who have qualifying impairments.37 As with Social Security, workers earn Medicare coverage by working and paying payroll taxes for a sufficient number of years in covered employment or self-employment. For most individuals, entitlement to Medicare is linked to entitlement to Social Security benefits.38

Social Security disability beneficiaries under 65 years old are entitled to Medicare after 24 months of entitlement to cash benefits.39 This requirement is known as the 24-month waiting period and does not apply to disability beneficiaries who have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD).40 In rare circumstances, disability beneficiaries who have certain medical conditions caused by exposure to qualifying environmental health hazards may become entitled to Medicare without having to satisfy a waiting period.41 After factoring in the five-month waiting period for cash benefits, disabled workers and disabled widow(er)s typically become entitled to Medicare 29-full calendar months after their disability onset date. Due, in part, to the 24-month waiting period, only 63% of all disabled workers reported entitlement to Medicare in 2013.42 Annual Medicare spending per disabled beneficiary under 65 years old was about $12,776 in 2013.43 Social Security disability beneficiaries under 65 years old are provided Medicare because they generally have medical conditions that require significant health care resources. However, many beneficiaries are often unable to work enough to gain health insurance through an employer or to pay for such insurance on their own.44 Medicare is not provided to non-disabled dependents under 65 years old.

Financing45

Social Security's income and outlays are accounted for through two legally distinct trust funds: the Federal Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund and the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund. In the federal accounting structure, a trust fund is an accounting mechanism used by the Treasury Department to track and report income dedicated for spending on specific purposes in accordance with the terms of a statute that designates the fund as a trust fund. The DI Trust Fund records income and outlays associated with disabled workers and their dependents, and the OASI Trust Fund records income and outlays associated with retired workers and their dependents as well as survivors of deceased insured workers. Administrative costs are also drawn from the trust funds. The program is financed primarily by dedicated payroll and self-employment taxes levied on the earnings of workers in jobs covered by Social Security. Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes are split evenly between employees and employers, whereas Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) taxes are borne fully by self-employed individuals.46 The overall Social Security payroll tax rate is 12.4% of a worker's earnings (6.2% for employees and employers, each), up to a maximum annual amount, which in 2017 is $127,200.47 The DI and OASI trust funds are also credited with income from the taxation of a portion of Social Security benefits and from interest earned on special-issue U.S. securities.

In 2016, DI Trust Fund expenditures were $145.9 billion, with 97.8% for benefit payments, 1.9% for administrative costs, and 0.3% for certain transfers.48 Total income credited to the DI Trust Fund in 2016 was $156.0 billion, with 98.4% from payroll taxes, 0.7% from the taxation of SSDI benefits, and 0.9% from interest earned on asset reserves. At the end of 2016, the balance of the DI Trust Fund was $46.3 billion. By comparison, the balance of the OASI Trust Fund was $2.8 trillion. A trust fund's balance is a measure of the amount by which income exceeded outlays in the past. Under current law, the Social Security trustees project that the DI Trust Fund will be depleted in 2028.49 At that point, continuing tax revenues to the DI Trust Fund would be sufficient to pay 93% of scheduled SSDI benefits. Using slightly different economic and demographic assumptions, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that under current law, the DI Trust Fund will be depleted in late FY2023.50

Budgetary Treatment of Social Security51

Section 201 of the Social Security Act authorizes the DI and OASI trust funds and designates them as such.52 It also provides the trust funds with a permanent and indefinite appropriation, meaning that all monies credited to the trust funds are available for obligation without the need for further legislative action. Stated another way, the appropriation of the trust funds provides legal authority to pay benefits automatically. Although trust fund expenditures for benefit payments are considered mandatory (i.e., direct) spending, the budgetary resources to administer the program are provided and controlled by the annual appropriations process and thus are considered discretionary spending.53 Congress provides SSA with funding to administer the Social Security program traditionally through the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies (LHHS) appropriations bill.54

From a federal budget perspective, the Social Security program is considered to be off budget, which means that the receipts and expenditures of the DI and OASI trust funds are excluded from the surplus or deficit totals in the President's budget and the congressional budget resolution.55 However, in evaluating the total budget deficit, CBO and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) often include the transactions of DI and OASI trust funds as part of the unified budget.56

Although all disbursements from the DI and OASI trust funds are classified as off budget—including both mandatory spending on benefit payments and discretionary spending on administrative resources—some of the budgetary resources in those trust funds are subject to sequestration under the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA; P.L. 99-177, as amended). Specifically, these are the administrative expenses that are funded through discretionary spending; mandatory spending on Social Security benefit payments is exempt from sequestration.57

Supplemental Security Income

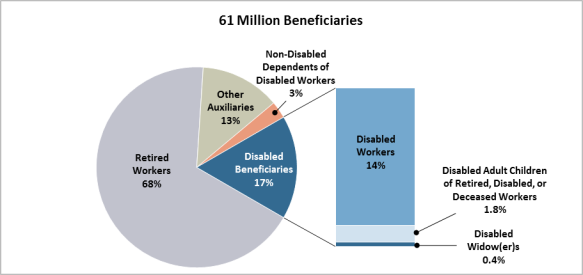

Established under Title XVI of the Social Security Act in 1972 and implemented in 1974, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is a means-tested federal assistance program that provides monthly cash benefits to the aged, blind, and disabled.58 The program is intended to provide a guaranteed minimum income to adults who have difficulty covering their basic living expenses due to age or disability and who have little or no Social Security or other income. It is also designed to supplement the support and maintenance of needy children who have severe disabilities. SSI is commonly known as a program of "last resort" because claimants must first apply for all other benefits for which they may be eligible; cash assistance is awarded only to those whose assets and other income (if any) are within prescribed limits. The basic federal SSI benefit is the same for all recipients and is reduced by most other income that an individual receives. In December 2016, SSA issued federally administered payments to 8.3 million SSI recipients, including 1.2 million children under the age of 18, 4.9 million adults aged 18-64, and 2.2 million seniors aged 65 or older.59

As shown in Figure 2, the vast majority of SSI recipients enter the program through the disability pathway. In other words, most individuals become eligible for SSI due to a qualifying impairment other than blindness. Blind or disabled SSI recipients who attain age 65 continue to be classified by SSA as blind or disabled, even though they meet the categorical requirements to be classified as aged. To avoid confusion, this report focuses primarily on blind or disabled SSI recipients under 65 years old.

|

Figure 2. SSI Recipients, by Eligibility Pathway and Age, December 2016 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on SSA, "SSI Monthly Statistics, December 2016," Table 2, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/index.html, and SSA, Annual Statistical Supplement, 2017, (in progress), Table 7.A1, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2017/7a.html#table7.a1. Notes: Figure includes individuals in receipt of a federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefit as well as 163,204 individuals in receipt of a federally administered state supplementary payment (SSP) but no federal SSI benefit. Some states complement federal SSI benefits with SSPs that are made solely with state funds. In states that contract with SSA to administer their state supplementation programs (i.e., federally administered SSP states), countable income is first subtracted from the federal SSI benefit until the benefit is completely offset. Any remaining countable income is then subtracted from the SSP. A person is considered eligible for SSI in such states if his or her countable income is less than the federal benefit rate (FBR) plus the amount of applicable federally administered SSP. However, in states that do not have supplementation programs or choose to self-administer their programs (i.e., state administered SSP states), a person is eligible for SSI if his or her countable income is less than or equal to the FBR. Thus, individuals in receipt of only a federally administered SSP due to excess countable income are considered by SSA to be SSI recipients but similarly situated individuals in receipt of only a state-administered SSP due to excess countable income are not. |

Eligibility Requirements

To qualify for SSI, a person must

- be aged, blind, or disabled as defined in federal law,

- have limited income and resources,

- meet certain other requirements, and

- have filed an application for benefits.60

Categorical Requirements

Public assistance programs often limit eligibility to certain groups or categories of people who often have difficulty providing for themselves. Under the SSI program, a person must be aged, blind, or disabled to receive benefits.61

- Aged. Individuals who are aged 65 or older.62

- Blind. Individuals of any age who have central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of a correcting lens or a limitation in the fields of vision so that the widest diameter of the visual field subtends an angle of 20 degrees or less (i.e., tunnel vision).63

- Disabled. Individuals who meet SSI's age-specific definition of disability (see the "Definition of Disability" section of this report).

Financial Requirements

The SSI program is based on financial need and therefore is restricted to individuals and couples who have minimal income and other financial resources (i.e., the program is means tested). Specifically, a person's countable income and resources must be within the program's statutory limits. Because certain income and resources are disregarded (i.e., not counted), a person may have gross income or resources above the countable limits and still be eligible for the program. In addition to the individual's own income and resources, the income and resources of certain ineligible family members (such as a spouse or parent) may be deemed available to meet the needs of the individual, and as such, may be included in his or her countable income and resources.

Income64

The limit for countable income—gross income minus all applicable exclusions—is equal to the federal benefit rate (FBR), which is the maximum monthly SSI benefit payable to qualified individuals and couples.65 In 2017, the FBR is $735 per month for an individual living independently and $1,103 per month for a couple living independently if both members are SSI eligible.66 The FBR is adjusted annually for inflation by the same COLA applied to Social Security benefits. Countable income is subtracted from the FBR in determining eligibility for SSI and the amount of the cash payment. In general, individuals and couples are eligible for SSI if their countable income is less than or equal to the FBR.67 In states that have an agreement with SSA for the agency to administer their state supplementation program (discussed later in this report), a person is considered eligible for SSI if his or her countable income is less than the FBR plus the amount of the applicable federally administered state supplementary payment (SSP).

Income is defined as anything one receives in cash or in kind that can be used to meet one's needs for food and shelter.68 SSI classifies income as either earned or unearned. Earned income includes wages, net earnings from self-employment, payments for services performed in a sheltered workshop, and certain royalties and honoraria.69 Unearned income refers to income not derived from current work, such as Social Security, veterans' benefits, interest income, cash from family or friends, and in-kind support.70 Certain income is disregarded in determining eligibility for and the amount of assistance provided by SSI.71 For example, the program excludes the following:

- the first $20 per month of any income (earned or unearned);

- the first $65 per month of earned income plus one-half of any earnings above $65;

- the first $30 per calendar quarter of infrequent or irregular earned income;

- the first $60 per calendar quarter of infrequent or irregular unearned income;

- food and home energy assistance;72

- housing assistance provided by most federally funded housing programs;73

- federal tax refunds and advanced tax credits;

- need-based assistance that is funded wholly by a state or local entity;

- impairment-related work expenses for disabled recipients and work expenses for blind recipients; and

- any income used to fulfill a plan to achieving self-support (PASS).74

Resources75

The limit for countable resources is $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple.76 Resources are cash or other liquid assets or any real or personal property that an individual (or spouse, if any) owns and could convert to cash to be used for his or her support and maintenance.77 Countable resources include the following:

- bank savings or checking accounts;

- stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and certificates of deposit;

- individual retirement accounts (IRAs) or 401(k)s under certain conditions;

- unrestricted health savings accounts (HSAs); and

- most types of trusts.

Individuals and couples are eligible for SSI (and federally administered SSP) if their countable resources are less than or equal to the applicable statutory limit at any given time.78 Unlike the FBR, the countable resource limits are not adjusted for inflation and have remained at their current levels since 1989. Certain resources are excluded in determining SSI eligibility, such as the following:

- the person's primary residence;

- household goods and personal effects;

- one automobile used for transportation;

- property essential to self-support;

- health flexible spending arrangements (FSAs);

- resources needed to fulfill a PASS;

- federal tax refunds and advanced tax credits for a 12-month period;

- burial funds or life insurance policies with a face value of up to $1,500; and

- the first $100,000 in an Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) account.79

Deeming

Because children typically do not have income or resources of their own, SSA uses a process called deeming to assign part of the value of the income and resources of an ineligible parent to the disabled child.80 A child is subject to deeming if the child is under the age of 18, unmarried, and lives in a household with his or her biological or adoptive parent(s) or lives in a household with his or her biological parent and the spouse of a parent (i.e., a stepparent). Deeming occurs because parents are presumed to be financially responsible for their children. Under deeming, the countable income limit is based on the number of ineligible parents and children in the household.81 The SSI program provides for a resource exclusion of $2,000 for one ineligible parent and $3,000 for two ineligible parents. Combined with the disabled child's own $2,000 resource exclusion, the countable resource limits under deeming are $4,000 for a child living with one ineligible parent and $5,000 for a child living with two ineligible parents. Children are subject to parent-to-child deeming until they reach the age of 18. Deeming also applies in cases where a SSI recipient lives with an ineligible spouse or where a qualified noncitizen has a sponsor.82

Other Requirements

In addition to categorical and financial requirements for SSI, a person must (1) reside in one of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, or the Northern Mariana Islands and (2) be a U.S. citizen or a noncitizen who meets a qualified alien category and certain other conditions.83 (SSI is not available in Puerto Rico, Guam, the Virgin Islands, or American Samoa.)84 Recipients who are outside the country for more than a month are ineligible for benefits.85 Except for situations involving certain medical facilities, residents of public institutions (such as a jail or prison) are generally ineligible for SSI.86 Additional requirements related to filing for all other benefits,87 fugitive felon status,88 and permitting SSA to contact a person's financial institutions also apply.89

Termination Events

In general, SSI benefits are suspended for any month during which a recipient fails to meet the aforementioned eligibility requirements. After 12 consecutive months of benefit suspension, most recipients are terminated from the SSI rolls and must file a new application for benefits.90 In 2015, the SSI termination rate—the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of SSI recipients during the year for a given age group—was 6.1% for children and 10.4% for working-age adults. As shown in Table 4, in 2015, the majority of SSI terminations for children were due to excess income or medical improvement and for working-age adults were due to excess income or death.

Table 4. Number of Nonelderly Blind or Disabled SSI Recipients Terminated and the Annual Termination Rate, by Age Group and Reason for Termination, 2015

|

Reason for Termination |

Under Age 18 |

Aged 18-64 |

||

|

Number of Recipients Terminated |

Termination Ratea |

Number of Recipients Terminated |

Termination Ratea |

|

|

Total |

77,785 |

6.1% |

510,624 |

10.4% |

|

Excess Income |

25,239 |

2.0% |

279,128 |

5.7% |

|

Death |

4,202 |

0.3% |

117,504 |

2.4% |

|

Whereabouts Unknown |

3,955 |

0.3% |

6,501 |

0.1% |

|

Excess Resources |

8,742 |

0.7% |

17,833 |

0.4% |

|

In Public Institution |

922 |

0.1% |

29,086 |

0.6% |

|

Failed to Furnish Report |

6,127 |

0.5% |

9,854 |

0.2% |

|

Outside United States |

453 |

0.0% |

2,331 |

0.0% |

|

No Longer Disabled |

25,809 |

2.0% |

43,073 |

0.9% |

|

Other |

2,336 |

0.2% |

5,314 |

0.1% |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2015, January 2017, Table 77, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2015/sect11.html#table77.

a. The termination rate is the ratio of the number of terminations to the average number of SSI recipients during the year for a given age group, which in 2015 was 1,282,372 for children and 4,915,391for adults.

Cash Benefits

As discussed earlier, in 2017, the federal benefit rate (FBR) is $735 per month for an individual living in his or her own household and $1,103 per month for a couple living in their own household.91 On an annualized basis, the FBR in 2017 is $8,820 for an individual and $13,236 for a couple. Individuals and couples with no countable income receive the maximum SSI benefit; those with countable income below the applicable FBR have their SSI benefits reduced so that their own income plus the reduced SSI benefit equals at least the FBR. In this way, the FBR acts as an income floor, providing a minimum level of support in 2017 equal to at least 73% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for an individual and 82% of FPL for a couple.92

Some states complement federal SSI benefits with state supplementary payments (SSPs) that are made solely with state funds. SSPs are intended to help individuals whose basic needs are not met fully by the FBR. States may provide SSPs to all eligible SSI individuals, or they may limit payments to certain SSI recipients, such as the blind or residents of domiciliary-care facilities. Currently, 44 states and the District of Columbia have optional state supplementation programs.93 States may self-administer their supplementation programs or contract with SSA to issue SSPs to eligible recipients on the state's behalf.94 In December 2016, more than 1.5 million individuals received a federally administered SSP from SSA.95 (The agency no longer publishes data on state-administered SSPs and their recipients.)96

As shown in Table 5, the average SSI payment was about $542, which on an annualized basis was about $6,509. These numbers reflect average federally administered SSPs paid to aged, blind, or disabled individuals by SSA but exclude average state-administered SSPs paid to such individuals by their state. Benefits are generally lower for seniors because some of them receive Social Security, which reduces their SSI. Benefits for children are typically higher because they often do not have income of their own.

Table 5. Number of SSI Recipients and Average Federally Administered Benefit Amount, by Age Group, December 2016

|

Age Group |

Number of Recipients |

Average Monthly Benefit |

Annualized Benefit |

|

Total |

8,251,161 |

$542.38 |

$6,508.56 |

|

Under Age 18 |

1,213,079 |

$649.58 |

$7,794.96 |

|

Aged 18-64 |

4,845,735 |

$563.49 |

$6,761.88 |

|

Aged 65 or Older |

2,192,347 |

$436.76 |

$5,241.12 |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, "SSI Monthly Statistics, December 2016." January 2017, Tables 2 and 7, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/index.html.

Notes: Number of Recipients includes individuals in receipt of a federal SSI benefit and those in receipt of a federally administered SSP but no federal SSI benefit. Average monthly benefit and annualized benefit include average federally administered SSPs but exclude average state administered SSPs.

The number of SSI recipients in Table 5 includes individuals in receipt of only federally administered SSPs (i.e., those in receipt of a federally administered SSP but no federal SSI benefit) but excludes individuals in receipt of only state administered SSPs. In states that contract with SSA to administer their state supplementation programs, countable income is first subtracted from the federal SSI benefit until the benefit is completely offset. Any remaining countable income is then subtracted from the SSP. A person is considered eligible for SSI in such states if his or her countable income is less than the FBR plus the amount of applicable federally administered SSP. However, in states that do not have supplementation programs or choose to self-administer their programs, a person is eligible for SSI if his or her countable income is less than or equal to the FBR. Thus, individuals in receipt of only a federally administered SSP due to excess countable income are counted as SSI recipients but similarly situated individuals in receipt of only a state-administered SSP due to excess countable income are not.

Reduced SSI Benefits for Residents of Certain Medical Facilities

Residents of public institutions are generally ineligible for SSI benefits, because the institution provides for their basic needs (i.e., food, clothing, and shelter).97 However, residents of medical institutions in which Medicaid pays more than half of the cost of care are eligible for a reduced SSI benefit of no more than $30 per month (or $60 per month for couples in certain situations).98 Institutionalized children under the age of 18 may be eligible for a reduced SSI benefit if private health insurance pays more than 50% of the cost of care or a combination of private health insurance and Medicaid pays more than 50% of the cost of care.99 The reduced SSI benefit, which is also known as a personal needs allowance, is used to pay for small comfort items not provided by the facility. Any countable income reduces the $30 benefit for institutionalized individuals; however, the full FBR is used in determining their eligibility for SSI ($735 per month for an individual in 2017).100 The reduced SSI benefit is not indexed to inflation and has remained at its current level since July 1988.

Tax Treatment of SSI Benefits

Cash assistance payments, including SSI and SSP, are not subject to federal income tax. Although not explicitly excluded under federal law, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has long held that payments made by "governmental units under legislatively provided social benefit programs for the promotion of the general welfare (i.e., based on need) are not includible in the gross income of the recipients of the payments."101

Benefit Calculation Example

As noted earlier, certain income is disregarded in determining SSI eligibility and the amount of assistance. For example, the program excludes the first $20 per month of any income (earned or unearned) and the first $65 per month of earned income plus one-half of any earnings above $65.102 After the application of the $20 general income exclusion, the offset for unearned income is $1 for $1; in other words, the SSI benefit is reduced by one dollar for each dollar of unearned income. For earned income above $65 (or $85 if the individual has no unearned income), the offset is $1 for $2; that is, the SSI benefit is reduced by one dollar for every two dollars of earned income.103 Income used for certain expenses is also excludable. Table 6 shows an example of how SSI benefits are calculated for an individual living independently who receives a $361 monthly SSDI benefit and has earnings of $289 each month.104

The $20 general income exclusion is first applied to unearned income, meaning that only $341 of the SSDI benefit is countable. Next, the $65 earned income exclusion is applied to the $289 in earnings; the remaining $224 in earnings is counted on a 50% basis (i.e., a $1 for $2 offset). Finally, earned and unearned countable income are summed and then subtracted from the $735 FBR, which results in a monthly SSI payment of $282.

|

Step |

Amount |

Description |

|

(1) Countable Unearned Income |

$361 |

SSDI Benefit |

|

-20 |

General Income Exclusion |

|

|

$341 |

Countable Unearned Income |

|

|

(2) Countable Earned Income |

$289 |

Earnings |

|

-65 |

Earned Income Exclusion |

|

|

$224 |

||

|

-112 |

½ of Remaining Earnings |

|

|

$112 |

Countable Earned Income |

|

|

(3) Total Countable Income |

$341 |

Countable Unearned Income |

|

+112 |

Countable Earned Income |

|

|

$453 |

Total Countable Income |

|

|

(4) SSI Benefit |

$735 |

2017 Federal Benefit Rate (FBR) for an Individual |

|

-453 |

Total Countable Income |

|

|

$282 |

Monthly SSI Benefit |

Source: CRS.

Note: The example is of an individual living independently in 2017 who (1) is not in receipt of SSP and (2) uses no other income exclusions other than those shown.

Income Breakeven Points

Individuals are ineligible for a monthly SSI payment if their countable income reduces the FBR to $0.105 The amount of earned or unearned income an individual can have so that countable income equals the applicable FBR is known as the income breakeven point. The dollar amount of the breakeven point in 2017 depends on the type of other income that an individual or couple receives.

- Unearned Income Breakeven Point. If an individual has only unearned income, the breakeven point is $755 per month for an individual and $1,123 for a couple (i.e., the applicable FBR plus the $20 general income exclusion).

- Earned Income Breakeven Point. If the individual has only earned income, the breakeven point is $1,555 per month for an individual and $2,291 for a couple (i.e., 2 x the applicable FBR plus the combined $85 earned income exclusion).106

Depending on the composition of other income, an individual who receives both earned and unearned income in 2017 faces a breakeven point somewhere between $755 and $1,555 per month ($1,123-$2,291 per month for a couple).107 However, most individuals who receive SSI have no other income, and of those recipients who do, only about 3% have any earnings from work in a given month.108

Treatment of In-Kind Support and Maintenance

The FBR is reduced for SSI recipients in certain living situations who receive in-kind support and maintenance (ISM), which SSA defines as food or shelter.109 If a person lives throughout a month in another's household and receives both food and shelter from others living in the household, the FBR is reduced by one third. This reduction is known as the value of the one-third reduction (VTR) and is not rebuttable.110 In 2017, the VTR is $245.00 per month for an individual ($735 x 1/3) and $367.66 per month for a couple ($1,103 x 1/3).111 However, if a person receives ISM but does not receive both food and shelter from the household in which the individual lives, then the FBR is reduced by the presumed maximum value (PMV) rule.112 The reduction under the PMV is equal to one-third of the FBR plus $20, which in 2017 is $265 per month for an individual ($735 x 1/3 + $20) and $387.66 per month for a couple ($1,103 x 1/3 + $20). Unlike the VTR, the PMV is rebuttable. If the SSI recipient can show that the value of food or shelter received is less than the PMV reduction, then SSA reduces the FBR by the actual value of food or shelter received. Some ISM is disregarded, such as federal housing assistance.113 According to SSA, only about 9% of SSI recipients have their cash payments reduced due to receipt of ISM.114

Relationship with Other Federally Funded Programs

Medicaid

In addition to cash benefits, most SSI recipients qualify for health coverage under Medicaid.115 Established under Title XIX of the Social Security Act, Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that finances the delivery of primary and acute medical services, as well as long-term services and supports (LTSS), to certain needy populations, including the aged, blind, and disabled.116 SSI recipients often have medical conditions that require significant health care resources. However, most SSI recipients are unable to work enough to gain health insurance through an employer or to pay for such insurance on their own.117 Medicaid provides most SSI recipients with health coverage, including some LTSS that private health insurance and Medicare do not cover, making it an important program for individuals with significant long-term care needs.118 In FY2015, estimated spending per Medicaid enrollee was $19,500 for the disabled and $14,300 for the aged.119

Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia grant Medicaid coverage automatically to individuals who become eligible for SSI. Section 1634 of the Social Security Act allows states to contract with SSA for the agency to perform Medicaid eligibility determinations for their SSI recipients as part of the SSI application process.120 In other words, an SSI application in these states is also an application for Medicaid. States that choose to contract with SSA for these Medicaid determinations are known as 1634 states. Eight states and the Northern Mariana Islands use the same income, resource, and disability standards of the SSI program to determine Medicaid eligibility for SSI recipients but require them to file a separate application for Medicaid with the state or local Medicaid office. States that elect this option are known as SSI criteria states.121 The remaining eight states use at least one eligibility criterion more restrictive than the SSI program to determine Medicaid eligibility for SSI recipients; however, any state-established standard may be no more restrictive than that used by the state's Medicaid program in 1972. States that elect to apply more restrictive standards are known as 209(b) states, after the section of the Social Security Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-603) that established the option.122

In general, individuals in receipt of SSI for a given month are also eligible for Medicaid for that month, provided they meet all other Medicaid eligibility requirements. SSI recipients typically become ineligible for Medicaid whenever their cash payments are suspended or terminated. In 2013, an estimated 96% of all SSI recipients reported Medicaid coverage.123

SNAP

In general, individuals living in pure SSI households—those in which all members receive SSI benefits—are categorically eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly the Food Stamp Program). SNAP is a federally funded assistance program, administered jointly with the states, that provides benefits to eligible households on an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card, which can be redeemed for foods at authorized retailers.124 SSI recipients may also qualify for SNAP if they live in households that meet SNAP's eligibility requirements. In 2013, an estimated 63% of all SSI recipients lived in households that received SNAP.125 California provides SSI recipients with a higher federally administered SSP in lieu of SNAP benefits.126

SSA is required to inform all applicants for or recipients of SSI or Social Security about the availability of SNAP benefits.127 The agency is also required to take SNAP applications from SSI applicants or recipients who live in pure SSI households and forward them to the local SNAP office within one federal workday.128 The SNAP state agency determines the SSI applicant's or recipient's program eligibility and calculates applicable benefit amounts.

Financing

Federal SSI benefits and administrative costs are financed from the general fund of the U.S. Treasury. For FY2016, total federal SSI costs were $63.1 billion, with $58.9 billion for benefits and $4.2 billion for administrative and other costs.129 SSPs are financed solely with state funds. States reimburse SSA for the cost of SSPs made to their eligible recipients and for the cost of administering their supplementation program. Spending on federally administered SSPs in FY2016 was $2.8 billion.130

Budgetary Treatment of SSI131

SSI is an appropriated entitlement (i.e., mandatory appropriation). Although SSI benefit payments are mandatory and open ended, SSI's authorizing statute does not provide authority to make payments to fulfill legal obligations.132 Therefore, funding for SSI benefits is provided through mandatory spending that is enacted through annual appropriations acts. As with Social Security, administrative expenses for SSI are discretionary and thus are controlled by the annual appropriations process. Congress typically appropriates funds for SSI benefit payments and administrative expenses into SSA's accounts each year as part of the LHHS appropriations bill. SSI benefit payments and administrative expenses are both exempt from sequestration.133

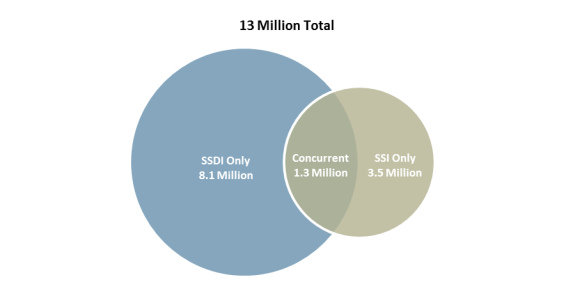

Concurrent Disability Beneficiaries

(Hereinafter the term SSDI refers to payments made to disabled workers, disabled widow[er]s, and disabled adult children of retired, disabled, or deceased insured workers.)

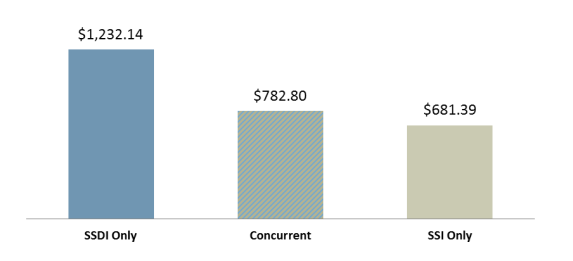

In December 2015, about 13 million adults aged 18-64 received SSDI or SSI due to a qualifying impairment (Figure 3). Of those, more than 1.3 million (or 10%) received both types of disability benefits. About one in eight SSDI beneficiaries aged 18-64 received SSI concurrently. At the same time, about a quarter of SSI recipients aged 18-64 also received SSDI. For this report, individuals who receive both SSDI and SSI due to a qualifying impairment are referred to as concurrent disability beneficiaries. Assuming they meet the applicable eligibility requirements, concurrent disability beneficiaries receive health coverage under Medicare and Medicaid. Individuals who qualify for both health care programs are known as dual eligibles.

The average combined benefit for concurrent disability beneficiaries in December 2015 was $783 (Table 7). Of that amount, about $538 was from SSDI and about $245 was from SSI. Because average benefits for concurrent disability beneficiaries were below the FBR for an individual ($733 per month in 2015) and because SSDI benefits generally offset SSI benefits on a dollar-for-dollar basis, combined benefit levels for each type of concurrent SSDI beneficiary were about the same. Thus, disabled workers (who have higher average SSDI benefit amounts) received lower average SSI benefits, and disabled adult children (who have lower average SSDI benefit amounts) received higher SSI benefits, resulting in roughly the same combined disability benefit amount across all three beneficiary types.

Table 7. Number of Concurrent Disability Beneficiaries Aged 18-64 and Average Benefit Amount, by Type of SSDI Beneficiary, December 2015

|

Type of SSDI Beneficiary |

Number of Concurrent Beneficiaries |

Average Monthly Benefit |

||

|

Combined |

SSDI |

SSI |

||

|

Total |

1,343,261 |

$782.80 |

$537.87 |

$244.93 |

|

Disabled Workers |

985,913 |

784.15 |

559.07 |

225.08 |

|

Disabled Widow(er)s |

29,974 |

788.56 |

543.28 |

245.28 |

|

Disabled Adult Children |

327,374 |

778.25 |

473.98 |

304.27 |

Source: CRS, based on SSA, SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2015, January 2017, Tables 15 and 16.

Notes: The term SSDI includes disabled workers, disabled widow(er)s, and disabled adult children of retired, disabled, or deceased workers.

As shown in Figure 4, the average benefit amount for concurrent disability beneficiaries is higher than that for SSI-only recipients but is lower than that for SSDI-only beneficiaries. The purpose of SSI for adults is generally twofold: (1) to provide cash assistance to aged, blind, or disabled individuals who have no income and (2) to supplement the incomes of those who have low Social Security benefits. For SSDI beneficiaries with minimal benefits and other income, SSI increases their overall monthly disability benefit from SSA.

Definition of Disability

To qualify for disability benefits under either program, claimants must meet the definition of disability prescribed in the Social Security Act. SSDI and SSI use a total work-limiting definition of disability for adults; in other words, an individual's impairment(s) must significantly interfere with his or her ability to earn a living.134 Most adults are considered disabled for SSDI and SSI eligibility purposes if they are unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.135 Work activity is considered substantial if it involves doing significant physical or mental activities, even if it is done on a part-time basis.136 Work activity is considered gainful if an individual does it for pay or profit, regardless of whether the profit is realized or legal.137

SSA uses a monetary threshold to determine whether an individual's work activity constitutes SGA, which the agency adjusts annually to reflect changes in national earnings levels.138 For SSDI, the SGA earnings threshold in 2017 is $1,170 per month for most individuals and $1,950 per month for statutorily blind individuals.139 Under the SSI program, SGA rules do not apply to statutorily blind individuals. Because of certain work incentives, the non-blind SGA earnings threshold applies to SSI disability claimants only at the time of application (see the "SSI Work Incentives" section of the report).

Adults generally qualify as disabled for SSDI and SSI purposes if they have an impairment (or combination of impairments) of such severity that they are unable to perform any kind of substantial work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy, taking into consideration their age, education, and work experience. The work need not exist in the immediate area in which the claimant lives nor must a specific job vacancy exist for the individual.

SSI's Definition of Disability for Children

The SSI program uses a special definition of disability for children because minors are generally not expected to work. Individuals under the age of 18 must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which results in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.140 Children typically qualify as disabled if they have a severe impairment (or combination of impairments) that limits their ability to engage in age-appropriate childhood activities at home, in childcare, at school, or in the community. In addition, the child's earnings must not exceed the non-blind SGA earnings threshold at the time of application.

Comparisons with Other Program Definitions of Disability

The definitions of disability under Titles II and XVI of the Social Security Act are considered total and long-term; neither program pays benefits to individuals with partial or short-term impairments. SSA's all-or-nothing definitions of disability are different from other disability standards. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides partial or total disability benefits to veterans with qualifying impairments on a scale from 0% to 100% (in 10% increments).141 In addition, state workers' compensation pays benefits for total or partial occupational-related injuries and illnesses that are permanent or temporary.142 According to SSA, the Social Security Act's "purpose and specific eligibility requirements for disability and blindness differ significantly from the purpose and eligibility requirements of other programs."143

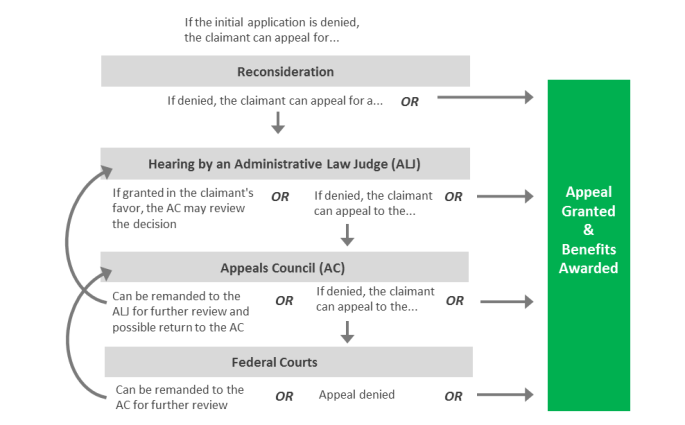

SSA's Disability Application and Determination Process144

The process begins when a claimant files an initial application for SSDI or SSI benefits using one of four methods: (1) submitting an application in person at one of SSA's more than 1,200 nationwide field offices; (2) contacting a SSA teleservice representative over the phone and relaying the necessary information; (3) sending a paper application by mail; or (4) filing an electronic application on ssa.gov (for SSDI and certain concurrent claims only).145 If the agency requires more information to process the application, it will contact the claimant by phone or arrange for an in-person interview at the local field office. Claimants must inform and submit all evidence to SSA related to their impairment as a condition of their application for benefits.146

Claims representatives at SSA's field offices screen claimants to make sure they meet the applicable non-medical entitlement factors. For SSDI, non-medical factors include disability-insured status, the work activity test (i.e., SGA earnings limit), and the claimant's relationship to certain family members. For SSI, such factors include income, resources, living arrangements, the work activity test (for non-blind claimants), citizenship, residency, and the requirement to apply for all other benefits. In general, claimants who do not meet the applicable non-medical entitlement factors are found to be ineligible for benefits and do not receive a disability determination. SSA field office personnel notify claimants whose applications are denied due to non-medical factors.

Applications that meet the applicable non-medical entitlement factors are forwarded to the disability determination services (DDS) office in the area that has jurisdiction for the disability determination (generally the state in which the claimant resides).147 DDSs, which are fully funded by the federal government, are state agencies tasked with reviewing the medical and vocational evidence and issuing the disability determination for SSA.148 Although DDS agency staff are state employees, they make the disability determinations based on federal law, regulations, and SSA's policy guidance. DDSs are located in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands.

The disability determination for both types of benefits is made based on evidence gathered in an individual's case record. Disability examiners—with the help of medical or psychological consultants (who are licensed physicians, psychiatrists, or psychologists)—typically use evidence collected from the claimant's own medical sources to evaluate the existence and severity of the claimant's impairment(s).149 However, if the medical evidence is unavailable or insufficient to make a determination, disability examiners can schedule a physical or mental examination or test from a medical source to obtain the necessary information. In such cases, SSA pays for the consultative examination (CE).150 After considering all medical and other evidence, the DDS agency issues a disability determination and returns the case to the SSA field office. If the claim is approved, the SSA field office sends out the initial award notice and begins processing the claim. If the claim is denied, the DDS agency prepares a personalized disability explanation and notifies the claimant of the decision.

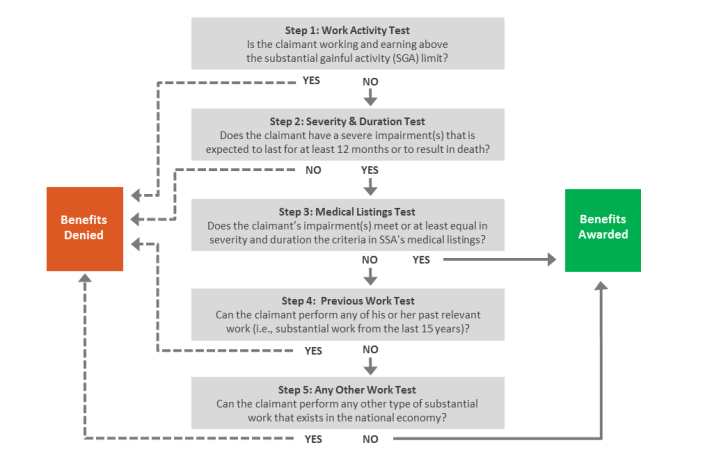

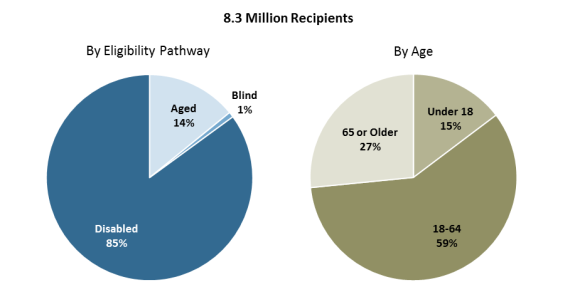

Disability Determinations for SSDI and Adult SSI Claimants

The Social Security Act gives the Commissioner of Social Security broad authority to promulgate regulations specifying the standards, administrative requirements, and procedures used in conducting disability determinations.151 Under its regulations, SSA employs a five-step sequential evaluation process to determine whether a claimant's medical condition meets the definition of disability prescribed in the act for SSDI and adult SSI claimants (Figure 5).152 Each step in the process is followed in a set order. If SSA finds a claimant disabled or not disabled at a given step, the initial disability determination process is completed and a decision by the agency is made. If SSA cannot find a claimant disabled or not disabled at a given step, the agency proceeds to the next step. The following section examines each step of the sequential evaluation process for adults in more detail.

Step 1. Work Activity Test

The SSA field office assesses whether a claimant's level of work activity constitutes SGA.153 In 2017, most claimants are found able to engage in SGA if their countable earnings average more than $1,170 per month.154 Countable earnings equal gross earnings minus applicable exclusions. Blind SSDI claimants are found able to perform SGA if their countable earnings average more than $1,950 per month. (SGA rules do not apply to statutorily blind SSI claimants.)

To determine countable earnings, SSA first documents a claimant's gross earnings for each month during the relevant period of work.155 The agency then considers whether the claimant's work was performed under any special conditions, such as in sheltered employment or under certain government-sponsored job training or employment programs. Earnings or other compensation derived from work performed under special conditions may be deducted (in part or in whole) from gross earnings. Reasonable costs for certain impairment-related work expenses (IRWE)—such as attendant care services or medical equipment—may also be deducted if the claimant needs such expenses to work. Once a claimant's countable earnings have been calculated and added together, SSA divides them over the number of months in the relevant review period to produce a monthly average. Claimants with countable monthly earnings at or below the applicable SGA limit proceed to the next step of the disability determination process. Those with countable monthly earnings above the applicable SGA limit are found not disabled, and their application is denied.

Step 2. Severity and Duration Test

The DDS agency determines whether available medical evidence establishes a physical or mental impairment (or combination of impairments) of sufficient severity to prevent the claimant from engaging in SGA and, if so, whether the impairment(s) can be expected to last for at least 12 months or to result in death. In making this determination, the DDS agency first verifies the existence of a medically determinable impairment using objective medical evidence (i.e., medical signs or laboratory findings) from the claimant's acceptable medical sources.156 A claimant is considered to have a medically determinable impairment if such evidence shows the existence of one or more anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities.

Once a medically determinable impairment has been established, the adjudicative team evaluates the severity of the impairment using all available evidence, including medical opinions and statements of symptoms from the claimant. Symptoms, such as pain or fatigue, are considered if the objective medical evidence from acceptable medical sources shows that the impairment(s) could reasonably be expected to produce the symptoms.157 The DDS agency then evaluates the intensity and persistence of the claimant's symptoms to determine the extent to which such symptoms interfere with the claimant's ability to work. A claimant's impairment(s) is ultimately considered severe if it significantly limits his or her physical or mental ability to do basic work activities. Basic work activities include

- walking, standing, sitting, lifting, pushing, pulling, reaching, carrying, or handling;

- seeing, hearing, and speaking;

- understanding, carrying out, and remembering simple instructions;

- use of judgment;

- responding appropriately to supervision, coworkers, and usual work situations; and

- dealing with changes in a routine work setting.158

A claimant's impairment(s) is considered not severe if it has only a minimal effect on his or her ability to perform basic work activities required in most jobs.

In evaluating the claim at Step 2, the DDS agency is required to consider the combined effect of all the claimant's impairments without regard to whether any such impairment, if considered separately, would be of sufficient severity.159 Thus, a claimant may meet the severity requirement if he or she has multiple non-severe impairments that when combined, have the same effect on the claimant's ability to function as a single severe impairment. Lastly, in addition to being severe, the claimant's medically determinable impairment(s) must be expected to result in death or have lasted or be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.160 Claimants who meet the severity and duration requirements proceed to the next step. Those who do not are found not disabled and their application is denied.

Step 3. Medical Listings Test

The DDS agency determines whether the claimant's medically determinable impairment(s) meets the medical criteria of an impairment specified in SSA's Listing of Impairments.161 The listings describe medically determinable impairments for each body system that the agency considers severe enough to prevent a claimant from performing any gainful activity, regardless of the claimant's age, education, or work experience.162 The listings, which are categorized across 14 major body systems for adults, contain examples of common impairments in the body system and specific evaluative criteria for confirming the existence of a qualifying impairment. Most listed impairments are permanent or expected to result in death. All other listed impairments are expected to last for at least 12 months or for a specific duration.

Claimants qualify at Step 3 of the disability determination process in one of two ways: (1) by meeting the criteria of a specific listing or (2) by equaling the criteria of a specific listing.

- 1. Meeting a Listing. A claimant's medically determinable impairment(s) must satisfy all of the criteria described in the listings (i.e., objective medical and other findings and the duration requirement); a diagnosis alone is insufficient to meet a listing.

- 2. Equaling a Listing. A claimant's medically determinable impairment(s) must be at least equal in severity and duration to the criteria of any listed impairment.163 If the claimant's impairment(s) is described in the listings but he or she does not exhibit one or more findings specific for the listing (or one of the findings does not meet the specified severity), the DDS will find the claimant's impairment(s) medically equivalent to the listing if the claimant has other findings related to his or her impairment(s) that are at least of equal medical significance to the required criteria. If the claimant's impairment is not described in the listings but is closely analogous to a listed impairment, the DDS will find the claimant's impairment(s) medically equivalent to the analogous listing if the findings related to the claimant's impairment(s) are at least of equal medical significance to those of the listed impairment.164

Claimants with impairments that meet or equal a listing are found disabled and awarded benefits. Those with impairments that do not meet or equal a listing proceed to Step 4.

Step 4. Previous Work Test

Claimants with severe impairments that do not meet or equal a listed impairment proceed to an individual assessment that examines their remaining ability to work. To make this determination, the adjudicative team conducts a residual functional capacity (RFC) assessment, which is a function-by-function assessment of a claimant's ability to perform sustained, work-related physical or mental activities despite the limitations and restrictions caused by his or her medically determinable impairment(s).165 In general, RFC is a claimant's maximum remaining ability to do sustained work activities in an ordinary work setting on a regular and continuing basis (i.e., eight hours a day, five days a week, or an equivalent work schedule). The RFC assessment is based on all available evidence in the claimant's case record, such as objective medical evidence, activities of daily living (ADL), and statements provided by the claimant or other lay sources (e.g., family, friends, neighbors). In evaluating a claimant's RFC, the DDS agency considers the effects of pain and other symptoms, as well as any non-severe impairment, on the claimant's ability to function in a work setting.

Once the assessment is complete, the DDS evaluates the claimant's RFC with the physical and mental demands of his or her past relevant work.166 Past relevant work is defined as work performed in the past 15 years, at SGA, and which lasted long enough for the claimant to learn to do it.167 The individual's past relevant work need not exist in significant numbers in the national economy.168 If a claimant's medically determinable impairment(s) does not prevent him or her from performing past relevant work, the claimant is found not disabled and the application is denied. If the claimant is found unable to perform past relevant work, the case proceeds to the next step.

Step 5. Any Work Test

At the final stage of the disability determination process, the DDS agency considers whether the claimant can adjust to any other type of work.169 Specifically, the claimant must be unable to do not only his or her previous work but cannot, considering his or her age, education, and work experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work that exists in the national economy.170 Work that exists in the national economy means work that exists in significant numbers either in the region where the claimant lives or in several regions of the country.171 It does not matter whether the work exists in the immediate area where the claimant lives, whether a specific job vacancy exists, or whether the claimant would be hired if he or she applied for such work.

At this stage, the DDS agency uses medical-vocational rules (also known as the grids) to relate the claimant's age, education, and work experience to his or her RFC to perform work-related physical or mental activities.172 The grids cross-reference the aforementioned vocational factors by certain exertional (i.e., strength demands) and skill levels to determine the limitations and restrictions imposed by the claimant's impairment(s) and related symptoms. The DDS agency uses the Department of Labor's Dictionary of Occupational Titles for information about the physical and mental demands needed for jobs in the national economy.173 In general, older individuals (i.e., those over the age of 50) who have limited education and work experience are more likely to be awarded benefits than younger individuals or those who have more education or work experience. Claimants with impairments that prevent them from adjusting to any other work that exists in the national economy are found disabled and awarded benefits. Claimants with impairments that allow them to adjust to a significant number of jobs in the national economy are found not disabled and their application is denied.

Disability Determinations for Child SSI Claimants

As noted earlier, because children are generally not expected to work, the SSI program uses a special definition of disability for minors. Individuals under the age of 18 must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment, which results in marked and severe functional limitations, and which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months. The first part of the disability determination process for child SSI claimants is similar to the one used for SSDI and adult SSI claimants (Figure 6).174