Tax Policy and U.S. Territories: Overview and Issues for Congress

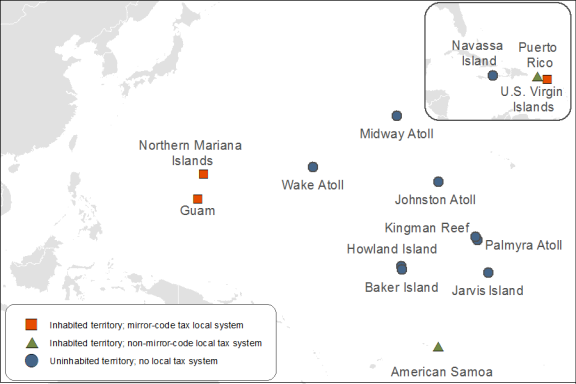

There are 14 U.S. territories, or possessions, five of which are inhabited: Puerto Rico (PR), Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), American Samoa (AS), and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Each of these inhabited territories has a local tax system with features that help determine each territory’s local public finances.

The U.S. Internal Revenue Code (IRC) has two important roles in establishing the tax policy relationship between the United States and the territories. First, native residents of U.S. territories are U.S. citizens or nationals but are taxed more similar to foreign citizens because income earned from territorial sources is treated like foreign-source income. The IRC also treats U.S. subsidiaries formed in the territories as foreign corporations, which can generally defer U.S. tax on income earned from business or trade in the territories.

Second, the IRC serves as the local tax laws in the territories that are required to use a mirror-code system (USVI, Guam, and the CNMI), in which the territory substitutes its name for the “United States” to give the IRC the proper effect as the territory’s local income tax system. AS is not bound by the mirror system but has chosen to adopt much of the IRC for its income tax. PR has its own income tax system, which is not based on the IRC.

These dynamics between federal and territorial tax policy raise several potential issues for Congress. First, economic development of the territories has been of perennial congressional interest. Tax incentives enacted by the territories and the United States have been shown to direct offshore investment to the territories. With this said, though, economic studies of one broader U.S. tax incentive, the now-repealed Section 936 credit, indicate that any employment effects are usually secondary to the magnitude of effects on shareholder earnings, and average tax benefit for corporations often equaled if not surpassed average compensation per employee. Tax policies that effectively subsidize a more narrow set of industries in certain territories, such as rum production in PR and the USVI and manufacturing in AS, still exist today.

Second, federal tax benefits could be used to assist low-income households living in the territories. For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the additional child tax credit (ACTC) could be expanded to low-income territorial households. The EITC is typically not available to territorial residents and the ACTC is limited to residents of the mirror code territories and certain residents of PR. Although these options could target lower-income households, they could also impose administrative costs for territorial households that are not required to file U.S. tax returns (e.g., because they only have territorial-source income). A payroll tax cut could be administratively simpler (since all territorial residents withhold taxes for some federal payroll taxes), but it would also be less narrowly targeted to lower-income households.

Third, interactions and differences in tax rates between the U.S. and territorial tax policies also create opportunities for tax arbitrage and avoidance by corporations and certain individuals. For the United States, this tax revenue loss is part of a broader issue with international income and profit shifting. For the territories, the revenue lost from special tax incentives could be used to reform the local tax system, increase spending on social programs, or pay down their debt. Such tax avoidance opportunities can distort the allocation of capital away from locations and industries where investment earns the highest economic rate of return. Additionally, the ability for certain taxpayers to utilize sophisticated tax avoidance strategies could raise issues of fairness.

This report summarizes U.S. tax policy related to the territories, including a general discussion of how federal taxes apply to territorial residents and how federal law affects the different territorial tax systems in similar or different ways. This report is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to federal or territorial tax policy or tax law.

Tax Policy and U.S. Territories: Overview and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Territorial Tax Authority: Mirror vs. Non-Mirror Code Jurisdictions

- Guam and the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Puerto Rico and American Samoa

- Applicability of Federal Taxes in the Territories

- U.S. Individual Income Taxation

- Corporate Income Taxation

- Payroll Taxes

- Excise Taxes

- Estate and Gift Taxation

- U.S. Tax Incentives Targeted to the Territories

- Policy Issues for Congress

- Tax-Based Assistance to Households in the Territories

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC)

- Payroll Tax Cut

- Economic Development of the Territories

- Tax Arbitrage and U.S. Tax Avoidance

Tables

Summary

There are 14 U.S. territories, or possessions, five of which are inhabited: Puerto Rico (PR), Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), American Samoa (AS), and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Each of these inhabited territories has a local tax system with features that help determine each territory's local public finances.

The U.S. Internal Revenue Code (IRC) has two important roles in establishing the tax policy relationship between the United States and the territories. First, native residents of U.S. territories are U.S. citizens or nationals but are taxed more similar to foreign citizens because income earned from territorial sources is treated like foreign-source income. The IRC also treats U.S. subsidiaries formed in the territories as foreign corporations, which can generally defer U.S. tax on income earned from business or trade in the territories.

Second, the IRC serves as the local tax laws in the territories that are required to use a mirror-code system (USVI, Guam, and the CNMI), in which the territory substitutes its name for the "United States" to give the IRC the proper effect as the territory's local income tax system. AS is not bound by the mirror system but has chosen to adopt much of the IRC for its income tax. PR has its own income tax system, which is not based on the IRC.

These dynamics between federal and territorial tax policy raise several potential issues for Congress. First, economic development of the territories has been of perennial congressional interest. Tax incentives enacted by the territories and the United States have been shown to direct offshore investment to the territories. With this said, though, economic studies of one broader U.S. tax incentive, the now-repealed Section 936 credit, indicate that any employment effects are usually secondary to the magnitude of effects on shareholder earnings, and average tax benefit for corporations often equaled if not surpassed average compensation per employee. Tax policies that effectively subsidize a more narrow set of industries in certain territories, such as rum production in PR and the USVI and manufacturing in AS, still exist today.

Second, federal tax benefits could be used to assist low-income households living in the territories. For example, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the additional child tax credit (ACTC) could be expanded to low-income territorial households. The EITC is typically not available to territorial residents and the ACTC is limited to residents of the mirror code territories and certain residents of PR. Although these options could target lower-income households, they could also impose administrative costs for territorial households that are not required to file U.S. tax returns (e.g., because they only have territorial-source income). A payroll tax cut could be administratively simpler (since all territorial residents withhold taxes for some federal payroll taxes), but it would also be less narrowly targeted to lower-income households.

Third, interactions and differences in tax rates between the U.S. and territorial tax policies also create opportunities for tax arbitrage and avoidance by corporations and certain individuals. For the United States, this tax revenue loss is part of a broader issue with international income and profit shifting. For the territories, the revenue lost from special tax incentives could be used to reform the local tax system, increase spending on social programs, or pay down their debt. Such tax avoidance opportunities can distort the allocation of capital away from locations and industries where investment earns the highest economic rate of return. Additionally, the ability for certain taxpayers to utilize sophisticated tax avoidance strategies could raise issues of fairness.

This report summarizes U.S. tax policy related to the territories, including a general discussion of how federal taxes apply to territorial residents and how federal law affects the different territorial tax systems in similar or different ways. This report is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to federal or territorial tax policy or tax law.

Introduction

There are 14 U.S. territories, or possessions, five of which are inhabited: Puerto Rico (PR), Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), American Samoa (AS), and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Each inhabited territory's local tax system has features that help determine the structure of its public finances.

Additionally, U.S. law, including the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), provides the territories with certain authorities relating to each territory's tax system, while also placing limits on the taxing authority of local lawmakers. The IRC also establishes interdependencies between federal and territorial tax systems, such that changes to the IRC can have economic and revenue effects in the territories and vice versa.

These dynamics between federal and territorial tax policy could interest Congress for a number of reasons. First, the inhabited territories elect representatives to Congress. The U.S. insular areas of Guam, AS, CNMI, and USVI are each represented in Congress by a Delegate to the House of Representatives.1 PR is represented by a Resident Commissioner, whose position is treated the same as a Delegate. Although these representatives have limited voting powers relative to other Members of the House, Delegates and the Resident Commissioner can speak and introduce bills and resolutions on the floor of the House, offer amendments and most motions on the House floor, and speak and vote in House committees.

Second, Congress could be interested in using tax policies intended to improve the economic conditions of the territories. The expansion of several individual federal tax benefits that are currently used to assist lower-income households and increase participation in the labor market, or the introduction of new ones, could potentially improve the quality of living among the territories. Additionally, Congress could use business-related tax incentives to encourage capital investment and employment in the territories.

Third, U.S. tax policies could have revenue implications for the territories, and vice versa. For the United States, territorial policies meant to encourage the relocation of certain industries, high-income, or high-net-worth residents to the territories could compound concerns about the erosion of the U.S. tax base and profit shifting. For the territories, their fiscal balances could be positively or negatively affected by the mix of federal and local tax policies. Territorial fiscal imbalances could raise concerns in Congress, such as recent legislation to create a fiscal control board for the purposes of restructuring public finances in PR.2

These policies could be considered by the bipartisan Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in PR, created by the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; P.L. 114-187). The Task Force has been directed to issue a report, by the end of 2016, providing recommended changes to federal law that would serve to "spur sustainable long-term economic growth, job creation, reduce child poverty, and attract investment" in PR. Although many of these issues are currently being considered within the context of PR, some of these issues have also been part of longer policy debates over U.S. tax policy toward the territories.

This report summarizes U.S. tax policy related to the territories, including what federal tax policies apply to residents in each of the territories and how federal law affects the different territorial tax systems. Multiple current tax policy issues related to the territories are then analyzed. This report is intended to provide Congress with an overview of tax issues related to the territories. It is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to territorial or federal tax policy or tax law. For more tax policy and tax law background on the U.S. territories, please see the list of related readings listed in the Appendix.

Territorial Tax Authority: Mirror vs. Non-Mirror Code Jurisdictions

U.S. law restricts the territories' authority to impose territorial (local) taxes. Most importantly is the distinction between the mirror code and non-mirror code tax systems. Three territories—Guam, CNMI, and the USVI—are currently required by U.S. law to have a mirror code (see Figure 1). This means these territories must use the IRC as their territorial income tax law,3 substituting terms where appropriate (e.g., the territory's name for "United States"). The mirror code requirements relate only to the IRC's income tax provisions (individual, corporate, and noncorporate business income), and not the IRC's other provisions such as excise taxes. Also, while these territories use the IRC as their income tax system, the tax imposed is a local tax (see Table A-1 for a discussion of how this could also affect tax filing requirements).

In contrast, territories that are not bound by the mirror code (PR and AS) may establish their own local forms of income taxation and promulgate their own income tax regulations.

Regardless of whether territories use the mirror code, they are still allowed to enact additional forms of taxation within certain boundaries enacted by U.S. Constitution and applicable federal statutes. A number of territories have used this authority to enact additional types of revenue-raising measures, or provide rebates on territorial-source income taxes.

Guam and the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands

Although Guam and CNMI are mirror-code jurisdictions, they are authorized under Section 1271 of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86) to delink from the IRC if certain conditions are met.4 In order to delink, Guam or CNMI would need to (1) enact a new, non-discriminatory local income tax system to replace the IRC that raised revenue during each of its first five years that is at least equal to the revenue raised during the final year under the old system; and (2) enter into an implementing agreement with the United States to address issues relating to tax administration.5 While Guam signed an implementing agreement with the United States in 1989, it has never gone into effect.6 CNMI, meanwhile, has not entered into an implementing agreement with the United States.7

U.S. Virgin Islands

USVI is required to mirror the IRC for its local tax code but has additional authority to levy taxes compared to Guam and CNMI. Unlike Guam or CNMI, TRA86 did not provide USVI with the authority to delink from the mirror code, reportedly by mutual agreement with the United States.8 TRA86 did grant USVI, though, with the authority to enact nondiscriminatory local income taxes in addition to those taxes mirrored in the IRC. However, USVI has not enacted any additional forms of income taxes to date.9 Under IRC Section 934, USVI is also allowed to provide tax benefits to its residents on their USVI-source income only.

Puerto Rico and American Samoa

There is no requirement in U.S. law that PR and AS use a mirror code.10 Thus, these two territories may enact their own income tax laws, subject to any requirements in U.S. law (e.g., any such tax laws must comply with the U.S. Constitution). Congress recognized PR's authority over matters of internal governance, including territorial tax law and policy, in the 1950 Federal Relations Act (P.L. 81-600) and its approval of the territory's constitution in 1952.11 Since then, PR has enacted its own income tax laws.12 AS, meanwhile, has chosen to adopt a modified version of the IRC as its territorial income tax laws. The current version of AS's local tax code is the version of the IRC that was in effect on December 31, 2000, with some modifications.13 In other words, provisions in the IRC that were enacted after December 31, 2000 are not automatically incorporated into AS' mirror-code system, unless the AS' government passed legislation amending their local tax code.

Applicability of Federal Taxes in the Territories

In addition to the imposition of local taxes in each territory, there are instances when federal taxes may apply as well. Two general principles are helpful in understanding when federal taxes apply in the territories. First, while the United States taxes its citizens, residents, and corporations based on their worldwide income regardless of whether the income is earned within the United States or abroad, for federal tax purposes the residents of the U.S. territories are generally treated more similar to foreign citizens (even though they are U.S. citizens or nationals) and corporations organized or created in the territories are treated like foreign companies.14 This means that federal taxes will generally only be levied when a territory resident or corporation has income that can be sourced (or connected) to the United States. Second, the territories are generally considered to be beyond the physical borders of the United States for federal tax purposes.15 Thus, any IRC provision whose applicability is limited to the geographic United States does not apply in the territories unless the provision specifically provides otherwise (such as the provisions listed in the "U.S. Tax Incentives Targeted to the Territories" section of this report).

U.S. Individual Income Taxation

As a general rule, individuals who are bona fide residents of a territory are eligible for a possession-source income exclusion, and therefore not subject to U.S. income tax on work or business income sourced from within the territories (except for compensation of federal government employees). Bona fide residents of a territory with income only from that territory need to only file one tax return with their local tax authorities. Table A-1 summarizes the general tax filing and income reporting procedures for individuals with territorial-source income.

The possession-source income exclusion currently applies to each of the territories through several sections of the IRC:

- American Samoa (IRC Section 931)

- U.S. Virgin Islands (IRC Section 932)

- Puerto Rico (IRC Section 933)

- Guam and CNMI (former IRC Section 935)16

The possession-source income exclusion and IRC tax coordination requirements between each territory and the United States will determine the filing situation of bona fide residents with income earned outside of their jurisdiction, and individuals who are not bona fide residents and earned territorial-source income.17 Bona fide residents with income from another jurisdiction (such as the United States) might have to file returns with the IRS or their local tax authorities (or both). For individuals who are not bona fide residents, tax filing requirements will depend on such things as the territory involved, the tax filer's citizenship and residency, and the source of the tax filer's income. U.S. tax-filing procedures also vary for excluding certain territorial-source income or allocating income earned in the territories versus the United States.

Bona fide residency in a territory is determined by the three-part test in IRC Section 937.18 To claim residency in a particular territory, the tax filer generally must

- 1. meet a physical presence test (e.g., present in the relevant possession for at least 183 days during the tax year);

- 2. not have a tax home outside the relevant possession;19 and

- 3. not have a closer connection to the United States or to a foreign country than to the relevant possession.20

For both territorial and mainland residents, situations might arise as to whether or not U.S. or territorial income tax is due on certain sources of income. For example, residents of the territories might work part of the year on the U.S. mainland, earn rental property income, or collect income from U.S.-based investments or businesses. Similarly, U.S. citizens residing in the mainland might earn income attributable to the territories. Table 1 outlines the general rules as articulated by the IRS for determining U.S. source of income in certain situations.

Additionally, IRC Section 911 permits U.S. citizens and residents who live and work abroad a capped exclusion of their foreign wage and salary income.21 However, U.S. citizens and residents who reside in the territories cannot qualify for income or housing exclusions specified in IRC Section 911 because they are not classified as living abroad for the purposes of the foreign earned income tax exclusion.22

|

Item of Income |

Factor Determining Source |

|

Salaries, wages, and other compensation for labor or personal services |

Where labor or services performed |

|

Pensions |

Contributions: where services were performed that earned the pension Investment earnings: where pension trust is located |

|

Interest |

Residence of payer |

|

Dividends |

Where corporation is created or organized |

|

Rents |

Location of the property |

|

Royalties: -Natural resources -Patents, copyrights, etc. |

Location of the property Where property is used |

|

Sale of business inventory: -Purchased -Produced |

Where sold Allocation if produced and sold in different locations |

|

Sale of real property |

Location of property |

|

Sale of personal property |

Seller's tax home (generally) |

|

Sale of natural resources |

Allocation based on fair market value of product at export terminal |

Source: IRS, Tax Guide for Individuals With Income From U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), Table 2-1, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p570.pdf.

Corporate Income Taxation

U.S. corporations are subject to U.S. income tax on their worldwide earnings. U.S. tax on the earnings of foreign subsidiaries of U.S. corporations is deferred until these earnings are repatriated back to the United States in the form of dividend distributions to the U.S. parent corporation. Generally, income earned by the active business operations of U.S. corporations in the territories is considered foreign-source income, because the IRC does not define them as being within the "United States." As a result, active corporate income earned in the territories can be deferred. The income earned by foreign branches of U.S. corporations, however, is not deferrable.23

There are two exceptions from the general deferral rule that result in taxation of certain forms of highly mobile income earned by a foreign subsidiary on a current year basis: (1) subpart F income of controlled foreign corporations (CFCs), and (2) passive foreign investment company (PFIC) rules.24 These forms of highly mobile income are not eligible for deferral because they can be transferred relatively easily to low-tax jurisdictions to lower U.S. income taxes. One exception to the current year taxation of subpart F income is for active financing income, which is income earned by U.S. corporations from the active conduct of a banking, financing, or insurance business abroad.25 This income can be deferred.26

U.S. corporations can claim a foreign tax credit, for any qualifying taxes paid to foreign jurisdictions, including the territories, up to the amount of U.S. income tax due. For example, a U.S. corporation earns $30 million in worldwide income, of which $10 million is foreign source income attributed to a wholly-owned subsidiary in PR. Assume that the tax rate on PR-source income is 10% and the U.S. tax rate is 35%. In this example, the pre-credit U.S. tax liability faced by the corporation is $10.5 million ($30 million times 35%). The corporation pays $1 million in income tax to PR ($10 million times 10%), which can be credited against U.S. income tax. Thus, the corporation would owe $9.5 million in income tax to the United States after applying foreign tax credits.

U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-owned corporations (including corporations organized in the territories) are generally subject to U.S. corporate income tax on any income effectively connected to a U.S. trade or business.

Dividends paid by U.S. corporations to foreign companies (such as a foreign parent company) are generally subject to a withholding tax of 30% (unless reduced by bilateral tax treaty). Foreign corporations created or organized in AS, Guam, CNMI, or USVI are not subject to this 30% withholding tax so long as the foreign company receiving the dividends meets certain territorial ownership and activity requirements.27 Each of these territories has adopted local tax laws to waive withholding taxes on payments made by local corporations to corporations organized in the United States.28 For PR corporations meeting these territorial ownership and activity requirements, the U.S. withholding tax rate on dividends is reduced from 30% to 10% so long as PR imposes a withholding tax on dividends paid to U.S. corporations not engaged in a PR trade or business at a rate not greater than 10%.29

Payroll Taxes

For the purposes of Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes, wages paid to U.S. citizens, resident aliens, and nonresident aliens employed in the territories are generally subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes under the same conditions that would apply to U.S. citizens and residents employed in the United States.30 The FICA payroll taxes are comprised of two taxes: (1) a 1.45% tax paid by both the employee and employer for Medicare Hospital Insurance (plus an additional tax of 0.9% on any earned income in excess of $200,000, $250,000 if married filing jointly); and (2) a 6.2% tax on wages, up to a cap, paid by both the employee and employer for the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (Social Security).31

PR and USVI are eligible under federal law for the Unemployment Compensation program, and thus only employers in those territories that pay wages to U.S. citizens, resident aliens, and nonresident aliens employed in the territories are subject to the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax at a rate equal to 6.0% of wages.32 Employers that make contributions to PR or USVI's unemployment insurance programs can be eligible for a credit against up to 90% of gross federal FUTA tax owed (i.e., 5.4% out of the 6% tax rate).33

As with FICA taxes on employee wages, bona fide residents of a U.S. territory who have selfemployment income must generally pay selfemployment tax to the United States.34 Bona fide residents may be subject to U.S. selfemployment tax even if they have no income tax filing obligation with the United States.

Employers and employees in the territories are generally not subject to withholding for U.S. income tax, since most wages paid by an employer residing in the territory are subject to withholding by the territory and are generally subject to local income taxes.35

Excise Taxes

U.S. excise taxes generally do not apply within the territories, with a few exceptions. One exception includes environmental excise taxes, such as the ozone-depleting chemicals tax or the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund tax on petroleum refiners, which are in effect in the territories.36 Another exception is a special excise tax imposed on products manufactured in PR and USVI that are shipped to the U.S. mainland for consumption or sale.37 The tax is equal to any U.S. excise tax (e.g., alcohol, tobacco) that would apply to the identical item produced on the mainland and was intended to prevent products that are manufactured in PR or USVI from having a tax advantage over similar products manufactured on the mainland. These "equalization taxes" are generally "covered over" to the respective treasuries, meaning that the U.S. Treasury transfers any taxes collected under this provision to the territories in the form of direct payments.

In addition to the equalization tax, a specific cover-over for federal tax is collected on rum imported to the United States. A portion of the $13.50 per proof gallon federal excise tax on rum imported into the United States from other sources—not including PR or USVI—is transferred to the treasuries of PR and USVI based on the estimated U.S. market share of rum produced in those territories. Under current law, the cover-over rate transferred to PR and USVI is $13.25 per proof gallon of rum taxed by the United States.38 The covered-over revenue has never been designated for particular purposes by Congress, but the territories have tended to dedicate some portion to fund marketing campaigns for the rum industry and general economic development.39

Estate and Gift Taxation

A U.S. citizen or resident is subject to tax on the value of bequests at death (regardless of where the property is located) as well as inter-vivos (i.e., during life) gifts.40 A tax rate of 40% is levied on the value of any estate exceeding the unified credit ($5.45 million in 2016, adjusted for inflation).41

There is an exemption for U.S. citizens residing in the territories who acquired U.S. citizenship solely by reason of birth or residence within the possession.42 However, the estates of territorial residents could still be subject to U.S. estate and gift tax if the estate contains any tangible property (such as real estate) located in the United States.43

U.S. Tax Incentives Targeted to the Territories

Federal tax incentives are made available for certain activities in the territories. Some of these provisions include the deduction for state and local income or sales taxes, the exclusion of interest on state and local bonds, the credit for research and experimentation, the low-income housing credit, and the renewable energy production tax credit, among others.44

There are also a few provisions in the federal tax code that effectively support specific industries in specific territories. As discussed in the "Excise Taxes" section of this report, rum cover-over payments are often used by the government of PR and USVI to support economic development projects for the rum industries in their respective territories. Additionally, the Section 199 deduction for certain manufacturing and production activities has been temporarily extended to include eligible activities in PR.45 Congress has also temporarily extended a corporate tax credit for business operations and investment activities in AS.46

Policy Issues for Congress

This section of the report summarizes three tax policy issues relevant to the territories that could be of current interest to Congress: (1) tax-based assistance to households in the territories, (2) tax policy and economic development of the territories, and (3) tax arbitrage and U.S. tax avoidance activities related to the territories.

Tax-Based Assistance to Households in the Territories

As an alternative or complement to enhancing social welfare programs, Congress could consider using U.S. tax policy to provide economic assistance to households in some or all of the territories.47 While there are many ways to potentially structure this assistance, common proposals include (1) expanding the availability of the federal earned income tax credit (EITC) to households in the territories, (2) expanding the availability of the federal additional child tax credit (ACTC) to households in the territories, and (3) creating a payroll tax cut for territorial tax filers.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC)

The EITC is a refundable tax credit available to eligible workers earning relatively low wages.48 The lump sum credit is issued to eligible households at one time during the year (after they file their annual federal tax returns), and the size of the credit depends on a variety of factors—namely the recipient's earnings and amount of dependent children. The EITC is a refundable tax credit, which means that it can benefit a taxfiler (in the form of a tax refund) even if they have no federal tax liability. The EITC is intended to encourage the nonworking poor to enter the workforce and reduce the overall tax burdens of working poor families.

The child tax credit (CTC) is a dollar-for-dollar reduction in tax liability and is partially refundable for low-income tax filers.49 The size of the credit depends on the tax filer's earnings and the number of qualifying children. The refundable portion of the CTC is known as the ACTC. The CTC is intended to reduce the financial burden that families incur when they have children.

Generally, bona fide residents of the territories do not meet the criteria to claim the federal EITC. Mirror code residents (Guam, CNMI, and USVI) and certain PR residents can claim the ACTC.50 Congress could expand eligibility of the EITC and ACTC to more residents of non-mirror code territories, as President Obama and others have called for in PR.51

The research surrounding the economic impact of these refundable credits in the United States may prove insightful to policymakers interested in expanding eligibility of these credits to the territories.52 In theory, the CTC and ACTC could provide subsidies for low-income families to work and have children. However, researchers have found it difficult to isolate the labor market effects of CTC and ACTC, particularly with the presence of the similarly-targeted, but larger, subsidy provided by the EITC.53 Additionally, the CTC and ACTC are unlikely to have a significant impact on inducing families to have additional children, as the expenses associated with raising a child typically exceed the benefits associated the tax provisions.

In comparison, studies have found that the EITC is effective in encouraging single mothers to enter the labor force, as was the original intention of the provision, but the credit is less effective in increasing the labor supply of secondary earners.54 There is no significant evidence that the EITC increases the labor supply of individuals without children, likely because so few childless taxpayers receive the childless EITC.55 The EITC also generally reduces poverty but only for recipients who have children.56

Given these findings, expanding access for territorial residents to claim the EITC and ACTC could increase labor supply and reduce poverty in these areas to the extent that these issues are concentrated in populations where the proposals have shown to be effective. For example, a single man without children or an unemployed spouse might not benefit much from these policies compared to a single mother with children.

There are several barriers that could prevent expanded EITC or ACTC from having the type of economic benefits claimed by the policies' proponents. Most notably, many territorial residents currently do not file a U.S. tax return, particularly if their income comes only from territorial sources (see Table A-1). Requiring these households to file a U.S. tax return to claim a federal tax provision could dissuade low-income territorial households from claiming the credit or raise tax compliance costs (especially if it requires accounting for income earned in the informal economy). Alternatively, the U.S. Treasury could offset the cost of such policies enacted via the local tax code. While this option could reduce the household tax compliance costs of filing a U.S. tax return, it could add responsibilities to territorial tax officials with little or no history of administering these provisions. Even in the United States, roughly one-quarter of EITC payments are issued improperly, with the most common errors being the claiming of ineligible children who are not qualified for the purposes of the EITC, income reporting errors, and filing status errors.57

Additionally, other policies (such as the application of the U.S. minimum wage and local labor regulations) could constrain employer demand for new workers and potentially offset any labor supply effects of expanding the EITC to the territories.58 These constraints could be lessened by reducing the applicability of the minimum wage to the territories or by introducing a tax-based labor subsidy (explained in "Economic Development of the Territories" section of this report).59

Expanding eligibility for these refundable tax credits could have significant budgetary costs. In 2006, the JCT noted that many people could be eligible for the EITC and ACTC in PR.60 On the one hand, a redesign of the benefit structure could lessen the revenue loss of expanding access to the EITC and ACTC for territorial residents. This could be achieved, for example, by reducing the income level at which the credits begin to phase out. Adjusting the phaseouts or reducing the benefit rates that apply to households on the U.S. mainland might also better target "low-income" households in the territories after adjusting for costs of living between territories and states on the mainland. If the thresholds are not adjusted, then higher-income households, by territorial standards, could receive "windfall" tax benefits that might not contribute much to improving the local economy or achieving the desired tax relief. On the other hand, the IRC typically does not adjust benefit or threshold amounts for differences in economic conditions between the states. Additionally, the cost of living varies across the territories, thus making it difficult to develop a single, alternative benefit formula just for the territories. One study found that some areas in the territories, such as San Juan (PR), have higher costs of living than average metropolitan areas in the United States.61

Payroll Tax Cut

Congress could increase the after-tax income of territorial households by reducing payroll taxes for territorial residents. A payroll tax cut would reduce the amount withheld from workers' paychecks, thereby increasing their take-home pay. Since all employees must pay payroll taxes on the first $118,500 of income (in 2016), a payroll tax cut would target lower-income households as well as upper-middle income households.62 Higher after-tax incomes could allow residents to more easily pay for basic needs. As previously mentioned, employers and workers in all five of the inhabited territories pay FICA taxes on their wages, and employers pay FUTA taxes on wages in PR and AS.

The most straightforward way to reduce payroll taxes would be to lower the payroll tax rates. For example, a temporary two-percentage-point reduction, or "holiday," in wages subject to OASDI payroll taxes was enacted in the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-312).63 The reductions in payroll taxes to the Social Security trust funds were offset by transfers from the general fund.64

Alternatively, a payroll tax cut could be modeled after the temporary Making Work Pay (MWP) tax credit that was enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA; P.L. 111-5).65 The MWP credit provided a refundable tax credit of 6.2% of wages (up to a certain dollar amount, based on filing status) through lower income tax withholdings in workers' paychecks. The credit phased in and phased out based on a worker's earnings, with the maximum credit amount being $400 for individuals ($800 for joint filers).

Still, both of these payroll tax options have an administrative advantage compared to the EITC and ACTC options in providing tax-based assistance to households in the territories. All territorial residents are subject to some form of federal payroll tax, while not all territorial residents file U.S. income tax returns. As a result, the territories would also not have to implement a new program for the U.S. Treasury to reimburse. The benefits of a payroll tax cut can also be delivered to households more quickly through workers' paychecks rather than through the EITC and ACTC, which are issued once per year during tax season.

Economic Development of the Territories

Congress could consider the role tax policies play in promoting economic development in the territories. For example, the Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico could consider options for the use of U.S. tax policies to encourage or discourage certain industries or types of jobs, or affect the structure of territorial public finances. Historically, Congress has deliberately structured provisions of the IRC to promote particular goals of economic development in the territories. Although a comprehensive historical analysis of U.S. tax policy toward the territory is beyond the scope of this report, notable examples include the now-repealed IRC Section 936 possessions tax credit (first enacted in 1976, but fully phased-out in 2005); deferral of tax on the earnings of territorial subsidiaries of U.S. corporations; and the federal, state, and local exclusion of interest on qualified public bonds issued by the territories.

Options available include tax policies that reduce the cost of capital investment. For example, one such option could provide a credit against U.S. income tax liability for new physical investment in the territories. Credits against U.S. income tax based on wages paid to new workers hired in the territories could reduce the cost of hiring workers. Both forms of tax incentives could be made available to encourage economic activity in any industry, or they could be structured to provide a relative boost to particular industries. However, these types of tax policies could redirect investment away from locations, industries, or modes of production that produce the greatest economic rate of return. Moreover, these policies might have unintended economic side effects. For example, tax incentives for capital investment in the territories could lead firms to engage in more capital-intensive modes of production, and reduce firms' reliance on labor. Even tax incentives for broader economic activity in the territories, including benefits for both capital- and labor-intensive producers, could leave the relative cost of both inputs unchanged, thereby generating little to no employments effects.66

Most evaluations of U.S. tax policies encouraging development in the territories have focused on the effects that the Section 936 possessions tax credit has had on PR. Section 936 enabled certain U.S. corporations to pay little to no U.S. tax on income generated by PR affiliates. This, in turn, provided a substantial incentive for U.S. investment in PR.67 It also, provided an incentive to use tax planning techniques to book profits in PR with little change in real economic activity (i.e., engage in profit shifting). While the Section 936 credit was not exclusively tied to PR operations, a U.S. Department of the Treasury data analysis published in 1991, found that U.S. corporations with affiliate activity in PR accounted for 96.8% of all corporate filings claiming the Section 936 credit and 99.2% of Section 936 credit amounts in 1987.68

Officials from PR claimed that Section 936 encouraged the development of a high-skilled labor force on the island, particularly in jobs within the pharmaceutical and electronics industries.69 The 1991 Treasury study confirmed these general arguments, as it found that Section 936 corporations employed 82.3% of manufacturing workers in PR and that the average annual wage for employees of Section 936 corporations was 59.5% higher than the average wage across all production workers in PR.70 With this said, though, the Treasury study also indicated that the Section 936 incentives effectively amounted to a subsidy almost equal to the average worker's salary in their respective industries. For corporations claiming the credit in 1987, the average tax benefit per employee was 94.5% of the average wage.71 Specifically in the drug, chemicals, and electronics manufacturing industries, the average tax benefit per employee were: 267.4%, 251.7%, and 116.3% (respectively). Other studies, such as those by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 1993, provided additional evidence that the average tax benefit for 936 corporations often equaled if not surpassed average compensation per employee.72 In 1996, Congress approved the ten-year phaseout of Section 936, in part, because the costs to taxpayers outweighed the benefits accumulating to the "relatively small number of U.S. corporations that operate in the possessions."73

Subsequent economic analyses support the notion that Section 936 activity provided significant benefits to U.S. parent corporations. For example, Grubert and Slemrod (2008) indicated that the U.S. firms that benefited the most from Section 936 were those that were able to shift income earned from intangible property, such as patents, developed from research and development conducted elsewhere (such as the United States) to their PR affiliates.74 The authors concluded that income shifting opportunities represented the predominant reason for U.S. investment in PR, even overcoming higher labor and electricity costs for production in the territory. This income shifting activity provided abnormally large returns to investors in Section 936 companies. Bosworth and Collins (2006) found that the net return on stockholders' equity in 1997 was 112% for pharmaceutical firms in PR (compared to 25% for pharmaceutical firms in the United States) and 48% for chemicals firms in PR (compared to 16% for chemicals firms in the United States).75

Tax Arbitrage and U.S. Tax Avoidance

Tax arbitrage activity in the territories is symptomatic of the broader erosion of the U.S. tax base due to international income and profit shifting. Opportunities for U.S. corporate and individual taxpayers to avoid or reduce U.S. tax liability are created, in part, because the territories are generally treated like foreign countries for U.S. income tax purposes, and some of the territories provide tax incentives to attract overseas investment.

As mentioned in the "Economic Development of the Territories," above, economic studies indicate that some U.S. corporations were able to pay low or zero income tax to the United States or local territories on income shifted to the territories during the era of the Section 936 tax credit. While the phaseout of Section 936 in 2005 ended this tax planning strategy, U.S. corporations can still take advantage of deferral, transfer pricing, low tax rates in third-party countries, and special tax incentives offered by the territories to lower their U.S. tax liability.76

For example, media reports indicate that U.S. multinational corporations in the past have established holding companies in a low- or zero-income tax jurisdiction (such as the Cayman Islands) and transferred the ownership of intangible assets (such as patents) to that holding company.77 A PR subsidiary of the U.S. multinational corporation can manufacture a product with the support of special tax incentives offered by the PR government. The U.S. multinational corporation can shift any earnings from U.S. sales of this product to their PR subsidiary, who can then shift these earnings to their holding company in the zero-tax jurisdiction in the form of royalty payments for the use of the intellectual property in manufacturing products in PR. Corporations can use transfer pricing strategies to further reduce taxable income.

Additionally, U.S. individuals can use U.S. or territorial tax incentives to reduce or avoid tax that would otherwise be subject to U.S. tax. For example, a common strategy marketed by tax planning professionals is for U.S. individuals to first establish residency in PR (e.g., by residing on the island for at least half of the year) as a means to avoid U.S. worldwide tax from PR sources (because of the IRC Section 933 exclusion). These individuals would then qualify under PR's Individual Investors Act, which exempts most investment income of new residents from PR tax.78 Overall, U.S. taxpayers can accumulate capital gains on certain investments made in the United States but avoid both U.S. and PR tax when realizing those gains after establishing residency in PR (although their estate could still be subject to U.S. estate and gift taxes).79

These tax avoidance strategies, both at the corporate and individual levels, could raise a number of concerns about the policy implications of these practices. First, tax arbitrage and avoidance strategies result in foregone revenue to the United States.80 In the territories, these policies could reduce or increase revenue, depending on whether the tax incentives redirected new investment to the territories or simply rewarded behavior that might have occurred even without the incentives. In any case, though, these tax strategies might be compared to alternative policy means to attract foreign capital or support economic growth. For example, the revenue raised by shutting off these tax strategies could be used for paying down government debt or on spending programs (such as infrastructure, workforce education, or general social services) that could potentially have a larger effect on growth or income security in the territories. Non-mirror-code territories could also use this revenue to lower statutory income tax rates for all territorial taxpayers (and not just those who are granted special exemptions).

Second, tax avoidance opportunities reduce economic efficiency by distorting relative rates of return to capital across locations. Additionally, capital allocation is distorted across industries, as incentives are offered in targeted industries and as more resources are devoted to international tax planning professional services than would otherwise occur under certain simpler international tax systems. A more efficient tax system would facilitate the flow of capital to locations and industries based on their economic returns, instead of gains from sophisticated tax planning.

Third, tax avoidance opportunities raise issues of economic equity, or fairness, as multinational corporations with the financial means and access to an in-house accounting department or outside consultants with tax planning expertise could pay a lower effective U.S. tax rate on their profits than similar-sized firms that only have U.S. operations. Similarly, individuals with the means to structure their finances offshore, travel and establish bona fide residency in the territories, and subsist on earnings from passive investments could end up paying a lower effective U.S. income tax rate (if any at all) than those who derive most of their earnings from wage income and do not have the means to establish residency in the territories.

Appendix. Summary of Internal Revenue Code Tax Filing Requirements for U.S. Territories

Table A-1 provides a summary of the general U.S. income tax filing requirements, as imposed by the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), for two groups of tax filers: (1) U.S. citizens or residents who are not bona fide residents of the territories (e.g., residents of the 50 states or the District of Columbia); and (2) bona fide residents of the territories. Table A-1 also indicates whether a territory is a "single tax return filing jurisdiction"—meaning a territory in which a bona fide territorial resident generally has to file only one annual income tax return, either with the IRS or the local territory's tax department. General filing procedures and income reporting measures are discussed for residents of the mainland United States and the territories under the three scenarios: (1) tax filers with only territorial-source income, (2) tax filers with income only from non-territorial sources, and (3) tax filers with a both territorial and non-territorial source income.

Table A-1 relates only to IRC's income tax filing requirements and does not apply, for example, to other types of taxes, including self-employment or payroll taxes (FICA) that are due to the United States. This table also does not discuss special tax filing procedures for certain groups, such as U.S. military servicemembers stationed in the territories. This table also does not provide details on income tax filing requirements imposed by the territories.

Table A-1 is intended to inform the legislative debate by providing an overview of current administrative tax filing procedures for territorial residents and U.S. citizens who are nonresidents of the territories but have territorial income. It is also intended to supplement the discussion of potential administrative challenges and costs related to extending provisions in the IRC to certain territorial residents. It is not intended to be a comprehensive source of tax advice or a substitute for professional accounting advice. For more guidance on tax compliance, see the IRS's Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570).81

For more background on tax law regarding the territories, the status of federal legislation to encourage development in the territories, see

- CRS Report R43541, Recently Expired Community Assistance-Related Tax Provisions ("Tax Extenders"): In Brief, by Sean Lowry (discussing the American Samoa Economic Development Credit);

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p570.pdf;

- IRS, "Individuals Living or Working in U.S. Territories/Possessions," at https://www.irs.gov/Individuals/International-Taxpayers/Individuals-Living-or-Working-in-US-Possessions;

- Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), Federal Tax Law and Issues Related to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, JCX-132-15, September 28, 2015, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4840; and

- JCT, Federal Tax Law and Issues Related to the United States Territories, JCX-41-12, May 14, 2012, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=fileinfo&id=4427.

|

Tax Filer Residency Status |

Is Applicable Territory a Single Tax Return Filing Jurisdiction? |

If Taxpayer Has Territory-Source Income Only |

If Taxpayer Has Non-Territory-Source Income Only |

If Taxpayer Has Both Territory- and Non-Territory-Source Income |

|

Non-Bona Fide Resident of U.S. Territory, but U.S. Citizen or Resident (e.g., resident of the 50 states or the District of Columbia) |

N/A |

AS, CNMI, Guam, and PR Rules: No income tax return must be filed with any of these territories. File U.S. income tax return with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and report worldwide income. USVI Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can claim a credit against U.S. tax liability for any income tax paid to the USVI. Attach IRS Form 8689 to U.S. income tax return indicating any USVI-source income and allocating that income as a share of worldwide income. File a copy of U.S. income tax return, including a copy of Form 8689, with the USVI. Pay any income tax due to the IRS and the USVI, as allocated on Form 8689, as separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

AS, CNMI, Guam, PR, and USVI Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. No U.S. or territory income tax return must be filed with any territory. Pay any income tax due to the IRS. |

AS Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. No U.S. or AS income tax return needs to be filed with AS. Pay any income tax due to the IRS. CNMI Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against U.S. income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or the CNMI. Attach IRS Form 5074 to U.S. income tax return indicating any CNMI-source income and allocating that income as a share of worldwide income. No U.S. or CNMI income tax return must be filed with the CNMI. Pay any income tax due to the IRS. |

|

(Continued) Non-Bona Fide Resident of U.S. Territory, but U.S. Citizen or Resident (e.g., resident of the 50 states or the District of Columbia) |

(Continued) |

(Continued) |

(Continued) |

(Continued) Guam Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against U.S. income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or Guam. Attach IRS Form 5074 to U.S. income tax return indicating any Guam-source income and allocating that income as a share of worldwide income. No U.S. or Guam income tax return must be filed with Guam. Pay any income tax due to the IRS. PR Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. No U.S. or PR income tax return needs to be filed with PR. Pay any income tax due to the IRS. |

|

(Continued) Non-Bona Fide Resident of U.S. Territory, but U.S. Citizen or Resident (e.g., resident of the 50 states or the District of Columbia) |

(Continued) |

(Continued) |

(Continued) |

USVI Rules: File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against U.S. income tax liability for income taxes paid to a foreign country or the USVI. Attach IRS Form 8689 to U.S. income tax return indicating any USVI-source income and allocating that income as a share of worldwide income. File a complete copy of U.S. income tax return, including a copy of Form 8689, with the USVI. Pay any income tax due to the IRS and USVI, as allocated on Form 8689, in separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

|

Bona Fide Resident of American Samoa (AS) |

No |

No U.S. or AS income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File an AS income tax return with AS and report worldwide income.

Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against AS income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to AS. |

File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. File an AS income tax return with AS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against AS income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to the United States or AS in separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income but exclude AS-source income. File an AS income tax return with AS and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against AS income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to the United States or AS in separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

|

Bona Fide Resident of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) |

Yes |

No U.S. or CNMI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a CNMI income tax return and report worldwide income.

Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against CNMI income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or the CNMI. Pay any income tax due to the CNMI. |

No U.S. or CNMI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a CNMI income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against CNMI income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or the CNMI. Pay any income tax due to the CNMI. |

No U.S. or CNMI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a CNMI income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against CNMI income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or the CNMI. Pay any income tax due to the CNMI. |

|

Bona Fide Resident of Guam |

Yes |

No U.S. or Guam income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a Guam income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against Guam income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or Guam. Pay any income tax due to Guam. |

No U.S. or Guam income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a Guam income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against Guam income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or Guam. Pay any income tax due to Guam. |

No U.S. or Guam income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a Guam income tax return and report worldwide income.

Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against Guam income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or Guam. Pay any income tax due to Guam. |

|

Bona Fide Resident of Puerto Rico (PR) |

No |

No U.S. or PR income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a PR income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against PR income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to PR. |

File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income. File a PR income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against PR income tax liability for income taxes paid to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to the United States or PR in separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

File a U.S. income tax return with the IRS and report worldwide income but exclude PR-source income. File a PR income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can claim a credit against PR income tax liability income taxes paid on Guam income to the IRS, a foreign country, or another territory. Pay any income tax due to the United States or PR in separate payments to the respective tax agencies. |

|

Bona Fide Resident of the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) |

Yes |

No U.S. or USVI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a USVI income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against USVI income tax liability for income taxes paid on to the IRS, a foreign country, or the USVI. Pay any income tax due to the USVI. |

No U.S. or USVI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a USVI income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against USVI income tax liability for income taxes paid on to the IRS, a foreign country, or the USVI. Pay any income tax due to the USVI. |

No U.S. or USVI income tax return must be filed with the IRS. File a USVI income tax return and report worldwide income. Taxpayer can generally claim a credit against USVI income tax liability for income taxes paid on to the IRS, a foreign country, or the USVI. Pay any income tax due to the USVI. |

Sources: CRS presentation of information in IRS, "Chapter 3—Filing Information in Certain U.S. Possessions," in Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), at https://www.irs.gov/publications/p570/ch03.html; and examples from IRS, "Chapter 5—Illustrated Examples," in Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), at https://www.irs.gov/publications/p570/ch05.html.

Notes: This table relates only to income tax filing requirements and does not apply, for example, to other types of taxes including self-employment or payroll taxes (FICA), which are due the United States. This table also does not provide details on income tax filing requirements imposed by territorial tax codes. Credits for foreign taxes paid can be claimed only up to the amount of tax due.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information, see CRS Report R40555, Delegates to the U.S. Congress: History and Current Status, by Christopher M. Davis. |

| 2. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44532, The Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA; H.R. 5278, S. 2328), coordinated by D. Andrew Austin. |

| 3. |

See 48 U.S.C. §1397 (USVI, originally enacted by the Naval Service Appropriations Act, 1922), §1421i (Guam, originally enacted by the 1950 Organic Act of Guam); Covenant to Establish Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Political Union with the United States of America, art. VI, §601(a), approved by P.L. 94-241, 90 Stat. 263 (48 U.S.C. §1801 note). |

| 4. |

See the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86; P.L. 99-514), §1271, 100 Stat. 2591 (26 U.S.C. §931 note). While Section 601 of the CNMI Covenant generally provides that CNMI is subject to the same federal tax treatment as Guam, CNMI is not required to delink if Guam chooses to do so. See P.L. 99-514, §1271(f)(3), 100 Stat. 2593. |

| 5. |

P.L. 99-514, §1271(b), (c), (d), (e)(2), 100 Stat. 2592. The Treasury Secretary could waive the revenue-raising requirement if the failure to meet it was for good cause and did not jeopardize the territory's fiscal integrity. |

| 6. |

Tax Implementation Agreement Between the United States of America and Guam, U.S.-Guam, April 3-5, 1989, 1989-1 C.B. 342. The effective date was postponed in 1990, with the parties explaining that Guam was not fully prepared to enact new tax laws to replace the mirror code. See Amendment to the Tax Implementation Agreement Between the United States of America and Guam, U.S.-Guam, Dec. 27, 1990. But Stephen A. Cohen, who was with the Guam Department of Revenue and Taxation, states that the delay is because, "The Treasury Department has refused so far to support the [Guam] Tax Code Commission's proposal that the U.S. Congress be asked to delete the dual return filing requirement (Guam and U.S.) now provided by the Tax Reform Act as a condition for delinkage." See Stephen A. Cohen, "Guam Tax Department Carries on in Wake of Big Shakeup," Tax Notes International, vol. 972, no. 7, Oct. 8, 1993. |

| 7. |

The lack of an implementing agreement has another consequence for Guam and CNMI that is unrelated to the delinking authority. Section 1277 of TRA86 requires Guam and CNMI to enter into a Section 1271 implementing agreement in order to make some of the act's amendments to the IRC effective in those territories. See P.L. 99-514, §1277, 100 Stat. 2600-601. Because neither territory has entered into an agreement, those provisions are not operable in Guam or CNMI at this time. |

| 8. |

See JCT, General Explanation of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, JCS-10-87, May 4, 1987, at http://www.jct.gov/jcs-10-87.pdf: "The treatment of the Virgin Islands reflects extended discussions between representatives of the Virgin Islands and the Treasury. It differs from the treatment of the other possessions because of the unique history of the relationship between the Virgin Islands and the United States." |

| 9. |

U.S. Virgin Islands Bureau of Internal Revenue (USVIBIR), Tax Structure Booklet of the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2015, p. 6, at http://www.vibir.gov/pdfs/Tax_Structure_2015.pdf. |

| 10. |

See, e.g., 48 U.S.C. §734. It appears that no provision in federal law expressly addresses the issue with respect to AS, but it is nonetheless clear there is no requirement that AS use the mirror code. For example, see U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Finance, Tax Reform Act of 1986, Report to accompany H.R. 3838, 99th Cong., 2nd sess., May 29, 1985, p. 477, at http://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/srpt99-313.pdf: "Unlike the possessions described above, U.S. law permits American Samoa to assume autonomy over its own income tax system." |

| 11. |

For the Federal Relations Act, see P.L. 81-600, 64 Stat. 319. For provisions on PR's constitutional authority, see P.L. 82-447, 66 Stat. 327. For additional discussion, see CRS Report R42765, Puerto Rico's Political Status and the 2012 Plebiscite: Background and Key Questions, by R. Sam Garrett. |

| 12. |

For example, see 13 P.R. Laws Ann. §§30011-33394 ("Internal Revenue Code for a New Puerto Rico"). |

| 13. |

Am. Samoa Code Ann. §§11.0403(a), 11.0501-11.0537. |

| 14. |

See 26 C.F.R. §1.1-1(a). |

| 15. |

For example, see 26 U.S.C. §7701(a)(9) ("The term 'United States' when used in a geographical sense includes only the States and the District of Columbia."). |

| 16. |

Section 935 was repealed by TRA86. However, its repeal is not yet effective in Guam and CNMI because they have not complied with TRA86 Section 1277. Section 1277 requires that Guam and CNMI enter into implementing agreements with the United States in order to make the act's amendments (including the repeal of Section 935) operable in those territories. If such an agreement were to go into effect, then Section 931 will apply in lieu of former Section 935. |

| 17. |

Note that not all mirror-code possessions follow the same tax-filing procedures. IRC Section 932 coordinates the tax filing requirements for the United States and USVI. For more information on territorial tax filing procedures, see IRS, Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), ch. 3, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p570.pdf. |

| 18. |

See also 26 C.F.R. §1-937-1. |

| 19. |

A tax home is generally the tax filer's regular or principal place of business or, if the tax filer does not have such a place of business, then his or her regular place of abode in a real and substantial sense. See 26 C.F.R. §1.937-1(d). |

| 20. |

The determination of whether a "closer connection" exists is made by looking at the facts and circumstances of each case, including the location of the tax filer's permanent home, where the filer votes, where the filer holds a driver's license, etc. See 26 C.F.R. §§1.937-1(e), 301.7701(b)-2(d). |

| 21. |

See IRC Section 911. For more information on the exclusion, see IRS, "Foreign Earned Income Exclusion—Requirements," at https://www.irs.gov/Individuals/International-Taxpayers/Foreign-Earned-Income-Exclusion—Requirements; and U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Budget, Tax Expenditures: Compendium of Background Material on Individual Provisions, committee print, prepared by the Congressional Research Service, 113th Cong., December 2014, S. Prt. 113-32, p. 31. |

| 22. |

See IRS, Treasury Regulations §§1.911-2(g),(h). |

| 23. |

A foreign subsidiary is a legal entity separate from its parent company, while a foreign branch is an extension of a domestic company. |

| 24. |

See IRC Sections 951-956. Subpart F income includes passive income—such as interest, dividends, annuities, rents, royalties—as well as certain sales and service income generated in countries that are not the origin, destination, or manufacturer of goods. U.S. taxpayers are taxed on a current basis of their pro-rata, or proportional, share of subpart F income. PFIC rules cover foreign-based mutual funds and other pooled investment vehicles that have at least one U.S. shareholder. Most investors in PFICs must pay income tax on all distributions and appreciated share values, regardless of whether capital gains tax rates would normally apply. These PFIC rules are intended to prevent U.S. taxpayers from deferring tax on income earned overseas simply by holding this income in a foreign-owned investment vehicle. |

| 25. |

Although some of the income derived from these lines of business (e.g., interest, dividends, and annuities) could be labeled as passive, they are excepted from subpart F if the income was generated as a result of active business operations. For more background, see CRS Report R41852, U.S. International Corporate Taxation: Basic Concepts and Policy Issues, by Mark P. Keightley and Jeffrey M. Stupak. |

| 26. |

The active financing exception to subpart F income tax rules was a provision that had been temporarily extended along with other temporary, "tax extender provisions," but was made permanent by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-113). |

| 27. |

See IRC Section 881(b). |

| 28. |

JCT, Federal Tax Law and Issues Related to the United States Territories, JCX-41-12, May 14, 2012, pp. 11-12, at https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=fileinfo&id=4427. |

| 29. |

See IRC Section 881(b)(2)(B). |

| 30. |

See IRC Sections 3121(b) and 3121(d). Recently, taxpayers have challenged the applicability of FICA taxes to services performed in CNMI. Both U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that have heard such claims have rejected them. The courts reasoned that because CNMI Covenant §606(b) provides that CNMI should be treated the same as Guam for social security purposes, FICA taxes apply to services performed in CNMI regardless of the citizenship or residency of the employee or employer. See Fang Lin Ai v. United States, 809 F.3d 503, 508 (9th Cir. N. Mar. I. 2015); Zhang v. United States, 640 F.3d 1358, 1366-70 (Fed. Cir. 2011). |

| 31. |

See IRC Sections 3101, 3111. The current tax rate for Social Security is 6.2% for the employer and 6.2% for the employee, or 12.4% total. |

| 32. |

See IRC Section 3301 for general FUTA tax rates, and see IRC Section 3306(j) for provisions including PR and the USVI in the definition of the "United States." |

| 33. |

See IRC Section 3302. For the definition of "United States" that includes PR and USVI, see IRC Section 3306(j). |

| 34. |

See IRS, Tax Guide for Individuals with Income from U.S. Possessions (Publication 570), at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p570.pdf. |

| 35. |

See IRC Section 3401(a)(8). |

| 36. |

For the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund tax, see IRC Sections 4611 and 4612(a)(4)(A). For the ozone-depleting chemicals tax, see IRC Sections 4682 and 4612(a)(4). |

| 37. |

See IRC Sections 7652 and 7653. |

| 38. |

The $13.25 per proof gallon limit on rum cover-over rate is a temporary "tax extender," set to expire at the end of 2016. The limit on the cover-over rate in permanent law is $10.50 per proof gallon. See CRS Report R43510, Selected Recently Expired Business Tax Provisions ("Tax Extenders"), by Jane G. Gravelle, Donald J. Marples, and Molly F. Sherlock; and CRS Report R41028, The Rum Excise Tax Cover-Over: Legislative History and Current Issues, by Steven Maguire. |

| 39. |

Sometimes, the territories use this cover-over revenue to securitize bonds for economic development, commonly referred to as "rum-tax bonds." For more background, see ibid. |

| 40. |

For more information, see CRS Report R42959, Recent Changes in the Estate and Gift Tax Provisions, by Jane G. Gravelle; and CRS Report 95-416, The Federal Estate, Gift, and Generation-Skipping Transfer Taxes, by Emily M. Lanza. |

| 41. |

See IRS, Revenue Procedures, 2015-53, November 2, 2015, at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-15-53.pdf. Credits against U.S. gift and estate tax liability are available for any estate taxes paid to a foreign country. |

| 42. |

See IRC Sections 2208 (estate tax) and 2501(b) (gift tax). |

| 43. |

For more information on the application of the estate tax for nonresident aliens, see CRS Report R43576, Estate and Gift Taxes for Nonresident Aliens, by Emily M. Lanza. |

| 44. |

The energy production tax credit is set to phase out completely for solar energy projects beginning construction by 2022 and wind energy projects beginning construction by 2020. See IRC Section 45(e)(1)(B) and Title III of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113). |

| 45. |

See CRS Report R43510, Selected Recently Expired Business Tax Provisions ("Tax Extenders"), by Jane G. Gravelle, Donald J. Marples, and Molly F. Sherlock. |

| 46. |

See CRS Report R43541, Recently Expired Community Assistance-Related Tax Provisions ("Tax Extenders"): In Brief, by Sean Lowry. |

| 47. |

For more information on social welfare programs that apply to the territories, see "Appendix B: Social Welfare Programs in the Territories" in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Ways and Means, Green Book: Background Material and Data on the Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Way and Means, 113th Cong., 2014, at http://greenbook.waysandmeans.house.gov/2014-green-book/appendix-b-social-welfare-programs-in-the-territories. |

| 48. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43805, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview, by Gene Falk and Margot L. Crandall-Hollick. |

| 49. |

For more information, see CRS Report R41873, The Child Tax Credit: Current Law and Legislative History, by Margot L. Crandall-Hollick. |

| 50. |

Bona fide residents of Guam, CNMI, and USVI are eligible for the ACTC under the mirror code. The IRS has stated that territorial residents who are not required to file a U.S. tax return are only allowed to claim the federal ACTC if an individual is a bona fide resident of PR who paid payroll taxes and has at least three qualifying children. See IRS Publication 570, Tax Guide for Individuals With Income From U.S. Possessions, at 13. The ACTC is calculated using two formulas. The first formula, known as the earned income formula, is calculated as 15% of earnings above $3,000 up to the maximum credit amount ($1,000 times the number of qualifying children). The second formula, which only applies to taxpayers with at least three qualifying children, is calculated as the excess of a taxpayer's payroll taxes (including one-half of any self-employment taxes) over their EITC, not to exceed the maximum credit amount. While taxpayers may generally use whichever formula results in the largest credit, bona fide PR residents may only claim the credit under the second formula. |

| 51. |