The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): Administrative and Compliance Challenges

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit available to eligible workers earning relatively low wages. Since the credit is refundable, an EITC recipient need not owe taxes to receive the benefit. Hence, many low-income workers, especially those with children, can receive significant financial assistance from this tax provision.

Studies indicate that a relatively high proportion of EITC payments are issued incorrectly. The Treasury Department estimates that in FY2017 between 21.9% and 25.8% of EITC payments—between $14.9 billion and $17.6 billion—were issued improperly. These improper payments can be overpayments or underpayments. The IRS’s most recent study (released in 2014) of the factors that lead to EITC overclaims—the difference between the amount of EITC claimed by the taxpayer on his or her return and the amount the taxpayer should have claimed—concluded that there were three major reasons that tax filers claimed the wrong amount of the credit:

Qualifying child errors: Some EITC claimants claimed children who were not qualifying children for the credit. The most frequent type of qualifying child error was the failure of the tax filer’s qualifying child to meet the credit’s residency requirement whereby the claimed child must live with the tax filer for over half the year in the United States. This was the largest error in terms of dollars of EITC overclaims.

Income reporting errors: Some EITC claimants misreported their incomes. For example, tax filers whose income was above the phase-out threshold amount would receive a larger credit if they underreported their income. This was the most common error in terms of its frequency among tax returns which included an EITC claim and also included an overclaim.

Filing status errors: Some EITC claimants used the incorrect filing status when claiming the credit. Specifically, married couples were filing as unmarried (as single or head of household) to receive a larger credit.

This IRS study—also referred to as the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study in this report, because it examined tax returns between 2006 through 2008—found largely the same results as a previous IRS study on overclaims, released in 1999. The 2014 study also found that the majority of taxpayers who overclaim the EITC are ultimately ineligible for the credit, rather than eligible for a smaller credit. The 2014 study did not estimate the proportion of errors which were intentional (i.e., fraud) versus “honest mistakes” made while attempting to comply with EITC rules

Unlike previous studies, the 2014 study also examined different types of paid tax preparers who prepared tax returns which included EITC claims (these tax returns are sometimes referred to as “EITC returns”). The study found that among paid tax preparers, unenrolled preparers were both the most common type of tax preparers of EITC returns and among the most prone to erroneous claims of the credit. Unenrolled tax preparers generally do not pass the same testing requirements as enrolled preparers (e.g., attorneys and CPAs) and in contrast to enrolled tax preparers are limited in how they can represent their clients before the IRS.

This report summarizes findings from the 2014 IRS study detailing the factors that can lead to erroneous claims of the credit, and describes the challenges the IRS may face in their efforts to reduce each type of error. It also examines the role of paid tax preparers on EITC error.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): Administrative and Compliance Challenges

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Why Did the IRS Study Overclaims Instead of Improper Payments in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study?

- A Brief Overview of Improper Payments and Overclaims

- Improper Payments and Administrative Costs of the EITC

- Tax Filer Errors that Lead to EITC Overclaims

- The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study and "High" and "Low" Estimates

- Qualifying Child Errors

- How Would Expanding the EITC for Childless Workers Affect EITC Overclaims?

- Study Results

- IRS Enforcement and the Residency Requirement

- Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

- Income Reporting Errors

- Study Results

- Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

- Filing Status Errors

- Study Results

- EITC Errors: Fraud or an Honest Mistake?

- Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

- Paid Tax Preparer Errors

- Study Results

- Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

- Concluding Remarks

Figures

Tables

Summary

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit available to eligible workers earning relatively low wages. Since the credit is refundable, an EITC recipient need not owe taxes to receive the benefit. Hence, many low-income workers, especially those with children, can receive significant financial assistance from this tax provision.

Studies indicate that a relatively high proportion of EITC payments are issued incorrectly. The Treasury Department estimates that in FY2017 between 21.9% and 25.8% of EITC payments—between $14.9 billion and $17.6 billion—were issued improperly. These improper payments can be overpayments or underpayments. The IRS's most recent study (released in 2014) of the factors that lead to EITC overclaims—the difference between the amount of EITC claimed by the taxpayer on his or her return and the amount the taxpayer should have claimed—concluded that there were three major reasons that tax filers claimed the wrong amount of the credit:

- Qualifying child errors: Some EITC claimants claimed children who were not qualifying children for the credit. The most frequent type of qualifying child error was the failure of the tax filer's qualifying child to meet the credit's residency requirement whereby the claimed child must live with the tax filer for over half the year in the United States. This was the largest error in terms of dollars of EITC overclaims.

- Income reporting errors: Some EITC claimants misreported their incomes. For example, tax filers whose income was above the phase-out threshold amount would receive a larger credit if they underreported their income. This was the most common error in terms of its frequency among tax returns which included an EITC claim and also included an overclaim.

- Filing status errors: Some EITC claimants used the incorrect filing status when claiming the credit. Specifically, married couples were filing as unmarried (as single or head of household) to receive a larger credit.

This IRS study—also referred to as the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study in this report, because it examined tax returns between 2006 through 2008—found largely the same results as a previous IRS study on overclaims, released in 1999. The 2014 study also found that the majority of taxpayers who overclaim the EITC are ultimately ineligible for the credit, rather than eligible for a smaller credit. The 2014 study did not estimate the proportion of errors which were intentional (i.e., fraud) versus "honest mistakes" made while attempting to comply with EITC rules

Unlike previous studies, the 2014 study also examined different types of paid tax preparers who prepared tax returns which included EITC claims (these tax returns are sometimes referred to as "EITC returns"). The study found that among paid tax preparers, unenrolled preparers were both the most common type of tax preparers of EITC returns and among the most prone to erroneous claims of the credit. Unenrolled tax preparers generally do not pass the same testing requirements as enrolled preparers (e.g., attorneys and CPAs) and in contrast to enrolled tax preparers are limited in how they can represent their clients before the IRS.

This report summarizes findings from the 2014 IRS study detailing the factors that can lead to erroneous claims of the credit, and describes the challenges the IRS may face in their efforts to reduce each type of error. It also examines the role of paid tax preparers on EITC error.

Introduction

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a refundable tax credit available to eligible workers earning relatively low wages. Because the credit is refundable, an EITC recipient need not owe taxes to receive the benefit.1 Hence, many working poor (especially those with children) who have little or no tax liability receive financial assistance from this tax provision. The amount of the EITC is based on a variety of factors, including number of qualifying children, earned income, and tax filing status.

One concern with the EITC is the credit's complex rules and formulas make it difficult for taxpayers to comply with and difficult for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to administer. Studies indicate that EITC errors (both unintentional and intentional) result in a relatively high proportion of EITC payments being issued incorrectly. The Department of the Treasury's Agency Financial Report (AFR) for fiscal year (FY) 2017 estimates that in FY2017 between 21.9% and 25.8% of EITC payments—between $14.9 billion and $17.6 billion—were issued improperly.2

In 2014, the IRS issued a study examining the major factors that lead taxpayers to erroneously claim the EITC. This study found that the majority of taxpayers who overclaim the EITC are ultimately ineligible for the credit, rather than eligible for a smaller credit. (While the study was released in 2014, it is also referred to as the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study in this report, because it examined tax returns between 2006 through 2008.) In addition, the IRS may have difficulty ensuring that tax filers are in compliance with all the parameters of the credit, a problem that may be exacerbated in light of budgetary constraints faced by the agency.

This report examines findings from the 2014 IRS study. The report first briefly defines and compares two common measures of EITC noncompliance: improper payments and overclaims. Next, the report provides an overview of the major factors leading to EITC noncompliance identified in the 2014 study on this issue, as well as challenges the IRS may face in their efforts to reduce each type of error. These factors include claiming ineligible children as qualifying children for the credit, income reporting errors, and filing status errors. Finally, the report describes the role of paid preparers in EITC noncompliance. This report does not provide a detailed overview of the credit. For more information on eligibility for and calculation of the EITC, see CRS Report R43805, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]

A Brief Overview of Improper Payments and Overclaims

This report discusses two measures of EITC noncompliance: improper payments and overclaims. Although these two measures of EITC noncompliance are related, they do differ.

- EITC improper payments are an annual fiscal year measure3 of the amount of the credit that is erroneously claimed (generally overclaimed) and not recovered by the IRS. In other words, recovered amounts of the credit are subtracted from erroneous claims of the credit to calculate improper payments.

- EITC overclaims are the amount of the credit claimed incorrectly and do not include the impact of enforcement activities.4

Hence, the major difference between improper payments and overclaims is that improper payments net out amounts recovered or protected by the IRS, while overclaims do not. Hence, improper payments are generally smaller than overclaims.

In addition, in contrast to improper payments which are published annually, overclaims have historically been reported less frequently (the last two comprehensive IRS studies that examined overclaims were released in 1999 and 2014). For a more detailed explanation of the relationship between improper payments and overclaims, see the Appendix.

Improper Payments and Administrative Costs of the EITC

The IRS estimates that in FY2017, between $14.9 and $17.6 billion in EITC payments (i.e., between 21.9% and 25.8% of payments) were issued improperly.5 EITC improper payments and rates are often compared to the improper payments and rates of traditional spending programs. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has designated the EITC as a "high-error program" in comparison to other spending programs, with EITC improper payments the second highest in terms of the total dollar amount (behind Medicare Fee-for-Service) and the highest in terms of improper payment rate (improper payments as a percentage of total payments).6, 7

However, in order to make accurate comparisons of improper payments between tax benefits and traditional spending programs, it may be necessary to also consider the comparative costs of administering tax benefits and spending programs. The federal government must spend money to administer its tax laws—as well as other government programs (e.g., food stamps, veteran's benefits). The IRS's administrative expenses include processing tax returns, auditing tax returns, and collecting unpaid tax liabilities. To the extent that additional administrative expenses are associated with fewer errors (unintentional mistakes and fraud) and ultimately a reduction in improper payments, these administrative costs should be considered when comparing the improper payments of tax benefits to traditional spending programs.

For example, some experts stress that spending programs may have lower improper payment rates than the EITC because they screen every participant before the benefit can be claimed. Such screenings generally involve high administrative costs. In contrast, the administrative cost of the EITC is relatively minimal. In congressional testimony, the IRS Taxpayer Advocate noted that8

Using tax returns as the "application" for EITC benefits rather than a traditional screening process results in low cost with high participation as well as the risk of improper payment. The IRS has pointed out that for the EITC current administration costs are less than 1% of benefits delivered. This is quite different from other non-tax benefits programs in which administrative costs related to determining eligibility can range as high as 20% of program expenditures.

In addition to comparing the EITC's improper payments to the improper payments of other spending programs, they can also be compared to revenue losses that arise from taxpayer noncompliance with other provisions of the tax code. EITC errors are not the major source of revenue losses arising from taxpayer noncompliance. The most recent IRS report on the tax gap—tax liabilities not paid—estimated that the annual average gross tax gap for the tax years 2008 to 2010 period was $458 billion. The net tax gap, which nets out amounts subsequently collected, was estimated to be $406 billion over the same time period.9 The majority of the net tax gap—$291 billion—is associated with the individual income tax. The largest source of noncompliance with individual income tax laws was the underreporting of business income on individual income tax returns, resulting in $125 billion of the tax gap The next largest source of the tax gap (in dollar terms) was the underreporting of self-employment tax, estimated to be $65 billion annually during the 2008 to 2010 period.10 As the Taxpayer Advocate stated in the Fiscal Year 2015 Objectives, when comparing the tax gap from the EITC noncompliance versus underreporting business income, "EITC overclaims account for 6% of the gross individual income tax noncompliance while business income underreported by individuals accounts for 51.9%."11,12

Tax Filer Errors that Lead to EITC Overclaims

In August 2014, the IRS released a new EITC compliance study examining the causes of EITC overclaims on 2006, 2007, and 2008 tax returns (henceforth referred to as the "2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study"). This study found that the majority of tax filers who overclaim the EITC are ineligible for the credit, instead of eligible for a smaller credit. Specifically, between 79% and 85% of EITC dollars claimed incorrectly were claimed by tax filers ineligible for the credit.

This study concluded that there were three major reasons13 for errors among claimants:

- EITC claimants claimed children who were not their qualifying children for the credit;

- EITC claimants misreported their income; and

- EITC claimants used an incorrect filing status when claiming the credit.

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that the most frequent EITC error was incorrectly reporting income, and the largest error (in terms of overclaim dollars) was incorrectly claiming a child for the credit, as illustrated in Table 1. The study also found that filing status errors are a source of EITC overclaims, although they are a relatively smaller cause of errors in comparison to income reporting and qualifying child errors. Unlike previous studies (which did not examine error among paid preparers), this study also found that among paid tax preparers, unenrolled preparers were the most common type of preparers of tax returns which include the EITC. In addition, unenrolled preparers were found to be most prone to error when claiming the credit.

|

Amount Overclaimed (billions $2008) |

|||

|

Error Type |

Number of Returns with Error (millions) |

Low Estimate |

High Estimate |

|

Income Reporting Error |

6.5 |

$4.5 |

$5.6 |

|

Qualifying Child Error |

3.0 |

$7.2 |

$10.4 |

|

Filing Status Error |

1.0 |

$2.3 |

$3.3 |

|

Total |

11.9 |

$14.0 |

$19.3 |

|

Addendum |

|||

|

Total Number of Returns Claiming the EITC |

23.7 |

Total Dollar Amount of EITC Claimed ($2008) |

$49.3 |

Source: Table 1 (Addendum) and Table 5 of the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study

Note: According to the IRS, the totals may be greater than the sum of each error type due to double counting. Double counting may occur for two reasons. First, more than one type of error may occur on a given return. Second the estimate of overclaim dollars treats each error in isolation. Each estimate is calculated assuming the respective error is only error eliminated. However a given amount of overclaim dollars may occur on a return with multiple errors, with the cost of one error influenced by presence and cost of the other error.

Total overclaims from the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study were estimated to be between $14.0 billion (low estimate) and $19.3 billion (high estimate).

For policymakers, it may be important to understand not only the types of taxpayer errors that lead to EITC overclaims, but also how the IRS may or may not be able to detect these errors and administer this tax benefit.

The IRS examines a small sample of all tax returns every year, including those with the EITC, to verify that taxpayers are complying with tax laws. In FY2017, the IRS examined over one million tax returns,14 of which more than a third (36.0%) included an EITC claim.15 (By way of comparison, the IRS processed over 245 million returns in the same time period.)16 The IRS estimated that of $29.0 billion of additional tax owed as a result of all examinations, 6.9% ($2.0 billion) came from tax returns which included an EITC claim.17

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study and "High" and "Low" EstimatesThe data from the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study are a subsample collected from the IRS National Research Program (NRP). The data from each of the three tax years (2006, 2007, and 2008) were representative of the population, but were combined and then averaged to provide a more statistically accurate sample. The NRP selects a representative sample of the tax filing population, and then conducts audits among this sample. Not all taxpayers selected for an audit actually participate and respond to the audit examiner's request for information. The rate of audit nonparticipation is much higher for this subsample (14.6%) than it is for all other taxpayers (2.9%). This can lead to uncertainty when trying to extrapolate results from the sample to the general population. As the IRS states when taxpayers do not provide the [audit] examiner with any input, their audit outcomes may not reflect their true circumstance. This is a particular concern for taxpayers claiming the EITC. To address the uncertainty of the behavior of audit nonparticipants, the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study generally provides a range of estimates based on different assumptions. The "high" estimate assumes that all audit nonparticipants claimed the credit erroneously. The "low" estimate assumes that noncompliance among audit nonparticipants is approximately at the same level as noncompliance among similar tax filers who do not comply with audits. Some research suggests that the "low" estimate is the more accurate of the estimates. In her 2014 testimony before Congress, the IRS Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson notes that based on Taxpayer Advocate Service research "taxpayers who fail to respond to the audit, or who have a late response, may in fact be eligible for the EITC."18 Hence, the Taxpayer Advocate exclusively uses the "low" estimate. In other parts of the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study, the researchers examine some of the factors that lead to noncompliance among the audit participants exclusively. In this case only one estimate is provided with the disclaimer that it applies to "known errors" (i.e., the portion of the sample population that did participate in the audit). |

Generally, the IRS does not reveal how it detects errors or flags questionable tax returns to prevent persons from using this information to circumvent IRS detection. However, public documents that evaluate the efficacy of the IRS error detection procedures do provide a general overview of some of the ways the IRS can attempt to detect errors, especially before a refund is issued. An overview and analysis of challenges the IRS may face in detecting and reducing specific errors is provided for each type of error. While not a complete evaluation, they are intended to highlight how the IRS may prevent overclaims from different types of error as well as the agency's limitations in effectively administering the EITC.

In addition to detecting and preventing errors, the IRS can, once they have determined a tax filer improperly claimed the EITC, subject that taxpayer to both financial penalties and disallow them from claiming the credit in future years. If upon examination by the IRS, all or part of a taxpayer's EITC is denied, the taxpayer19

(1) must pay back the amount in error with interest; (2) may need to file the Form 8862, Information to Claim Earned Income Credit after Disallowance; (3) may be banned from claiming EITC for the next two years if we [the IRS] find the error is because of reckless or intentional disregard of the rules; or (4) may be banned from claiming EITC for the next ten years if we [the IRS] find the error is because of fraud.

Tax return preparers who erroneously claim the credit on behalf of clients may also be subject to financial penalties, suspension or expulsion from e-file, injunction preventing them from preparing returns or subjecting them to certain limitations, and other disciplinary action.

Qualifying Child Errors

A child must meet three requirements or "tests" to be considered a "qualifying child" of an EITC claimant. First, the child must have a specific relationship to the tax filer (son, daughter, stepchild or foster child, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, stepsister, or descendent of such a relative).20 Second, the child must share a residence with the tax filer for more than half the year in the United States.21 Third, the child must meet certain age requirements; namely, the child must be under the age of 19 (or age 24, if a full-time student).22 These age requirements are waived if the child is permanently and totally disabled. If the child claimed for the EITC does not meet all of these requirements, they are considered to be claimed in error.

Erroneously claiming a child can result in a significant EITC overclaim per taxpayer. For example, in 2018, the maximum credit amount for taxpayers with no qualifying children is $519. This increases to $3,461 for taxpayers with one qualifying child, $5,716 for taxpayers with two qualifying children, and $6,431 for taxpayers with three or more qualifying children.

Study Results

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that in terms of dollar amounts of overclaims, errors in claiming the qualifying child were the largest source of EITC overclaims. Specifically, the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that of the aggregate amount overclaimed, 38% of overclaim dollars were associated with a qualifying child error, averaging $2,384 per return in overclaim.23 (These estimates reflect overclaims from known errors where a taxpayer selected for the audit fully participated in the audit. Hence, these numbers are not comparable to the "high" and "low" estimate provided in Table 1.) Errors in claiming qualifying children were the second most common error, found on 21% of returns with an EITC overclaim.

IRS Enforcement and the Residency RequirementThe failure of taxpayers' children to meet the qualifying child residency requirement is the largest source in dollars of EITC overclaims, and has historically been the largest source of overclaim dollars. The Taxpayer Advocate in the FY2015 Objectives Report to Congress notes that "the IRS does not focus on EITC errors with the highest level of noncompliance and misses an opportunity to educate taxpayers about the requirements for claiming [the] EITC and preventing future noncompliance."24 Specifically, the Taxpayer Advocate notes that the IRS tends to disproportionately audit returns associated with children who fail both the residency and relationship test (75% of audited EITC returns for 2012), and audits fewer EITC returns that fail the residency test exclusively (16% of audited EITC returns for 2012). According to the Taxpayer Advocate, "the IRS should focus more of its audit efforts on returns that have qualifying children with only residency issues, instead of primarily focusing on returns with qualifying children having both relationship and residency issues."25 The Taxpayer Advocate also noted that the database and selection criteria used to screen EITC returns for audit during tax filing season failed to detect most noncompliant taxpayers that participated in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study and erroneously claimed a child for the EITC. |

Although qualifying children errors were the largest EITC error in dollar terms, the majority of children claimed for the EITC are claimed correctly. The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that 87% of children were claimed correctly. Of the 13% of children claimed in error, the most frequent type of qualifying child error was the failure of the tax filer's qualifying child to meet the residency requirement.26 As previously discussed, a qualifying child for the EITC must share a residence with the taxpayer for more than half the year in the United States. Taxpayers may claim the EITC in error if they presume that providing for or being a parent of a child entitles them to the EITC. The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that among those children known to be claimed in error, more than three-quarters (76%) were due to the tax filer's child failing to meet the residency requirement of the credit.27

The second most common "qualifying child error," accounting for 20% of known qualifying child errors, was the failure of the child to meet the relationship test. In other words, the child claimed for the EITC was not the son, daughter, stepchild, foster child, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, or stepsister (or descendent of such a relative) of the EITC claimant.

Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

When the IRS receives a federal income tax return from a taxpayer with qualifying children claiming the EITC, it may have limited data to verify that the child meets the relevant EITC requirements. As previously discussed, one of the largest sources of qualifying child errors is the child failing to meet the EITC's residency requirement. Currently the IRS has the authority to use the Federal Case Registry of child support orders (FCR) to attempt to determine if the child is living with the EITC claimant during the filing season, and summarily deny the credit if a claimant is deemed ineligible. Summarily denying the credit effectively means that the refund money is "stopped before going out the door," as opposed to issuing the refund and then verifying information after filing season. Researchers have suggested using the FCR data because

the case registry identifies child support payees and child support payors. It [is] further assumed that the payee generally has physical custody of the child. If the assumption is true, then EITC claims made by someone other than the child support payee would be noncompliant since they would not meet the "residence test" that requires an EITC qualifying child to live with the claimant for more than half the year.28

However, the IRS does not currently use the FCR during filing season to summarily deny claims29 before a refund is issued. A 2011 IRS report found that the FCR resulted in a relatively high percentage of "false positives" in terms of identifying children that failed to meet the residency test of the EITC.30 Specifically, the IRS audited a statistically valid random sample of tax returns that the FCR identified as including children who failed to meet the EITC residency requirement. A failure to meet the residency requirement would result in a substantially smaller EITC for the taxpayer. The IRS found the FCR incorrectly identified a significant proportion of the sample as failing to meet the residency requirement, a proportion that was deemed too high to be used in pre-refund compliance.

The FCR which includes information on children, custodial parents, and non-custodial parents, may lead to inaccurately classifying a child as not meeting the EITC residency requirement for a variety of reasons. For example, a court order may require that the custodial parent of the child be the mother. Hence, the father would be the noncustodial parent, and based on the FCR, the father would be ineligible to claim the child for the credit. However, if due to some unforeseen circumstances, like the mother's job loss, the child moved in with the father for a given year, without notifying the court, this change would not be noted in the FCR. The child would now (assuming the child met the age test) be the qualifying child of the father for the purposes of claiming the EITC. However, based on the FCR data alone, the father would be incorrectly denied the EITC. As the Taxpayer Advocate has stated with respect to using the FCR to summarily deny the EITC during filing season31

applying data collected for other purposes to an EITC claim is akin to verifying addresses with a telephone directory to deny a home mortgage interest deduction. Even if virtually all of the entries in a directory were accurate, they were compiled for a different purpose, do not disprove eligibility under the tax law, were compiled at a prior date and many not be current, and should not deprive a taxpayer of a due process right to present his or her own facts.

To verify a child meets the residency requirement of the EITC, the IRS has several Social Security Administration databases to verify the relationship test. These include DM-1, which contains the names, Social Security numbers (SSNs), and dates of birth for all SSN holders; Kidlink, which links SSNs of children to at least one of their parents (but only for children who received SSNs after 1998); and Numident, which provides information from birth certificates, including parents' names.32 Currently, it appears that the IRS does not cross-reference all EITC returns to these databases during the filing season. This may be due to limitations of these databases to accurately document that the child fulfills the relationship requirement. As the IRS Taxpayer Advocate has stated, "a child's relationship and residence with respect to a low-income taxpayer are highly circumstantial facts to be validated on a case-by-case basis."33,34

Instead, in conjunction with the Federal Case Registry, the IRS may use these databases to construct filters that identify EITC returns with a high probability of error in claiming a qualifying child for the credit. After a return is flagged "the return is placed in queue for possible prefund or post-refund audit. Depending on available resources, [the] IRS will audit a portion of the returns ... before complete refunds are sent to the taxpayers. To the extent returns are not handled in prerefund audits, [the] IRS will include them for possible postrefund audits."35 Nonetheless, it is generally harder to recover refunds that have already been released as opposed to those denied during filing season.

Income Reporting Errors

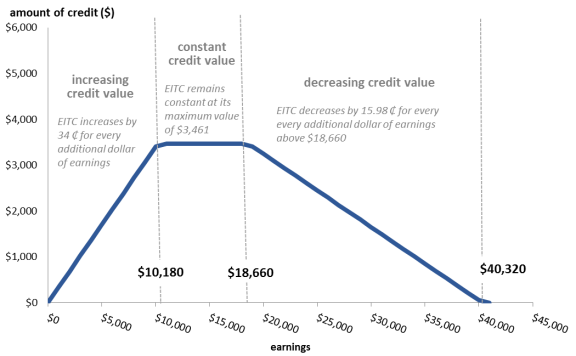

The amount of the EITC depends in part on a taxpayer's income. For a taxpayer with a given number of children and marital status, the EITC is structured to vary by income—gradually increasing, then remaining constant at its maximum level, and finally gradually declining in value. Figure 1 illustrates the EITC amount by earnings level for an unmarried taxpayer with one child for 2018. It illustrates the three distinct ranges of EITC's value by income, with specific dollar amounts and rates applicable to this type of family:

- Phase-in Range: The EITC increases with earnings from the first dollar of earnings up to earnings of $10,180. Over this earnings range, the credit equals the credit rate (34% for a tax filer with one child) times the amount of annual earnings. The $10,180 threshold is called the earned income amount and is the earnings level at which the EITC stops increasing with earned income. The income interval up to the earned income amount, where the EITC increases with earnings, is known as the phase-in range.

- Plateau: The EITC remains at its maximum level of $3,461 from the earned income amount ($10,180) until earnings exceed $18,660. The $3,461 credit represents the maximum credit for a tax filer with one child in 2018. The income interval over which the EITC remains at its maximum value is often referred to as the plateau.

- Phase-out Range: Once earnings (or adjusted gross income (AGI), whichever is greater) exceed $18,660, the EITC is reduced for every additional dollar over that amount. The $18,660 threshold is known as the phase-out amount threshold for a single taxpayer with one child in 2018. For each dollar over the phase-out amount threshold, the EITC is reduced by 15.98%. The 15.98% rate is known as the phase-out rate. The income interval from the phase-out income level until the EITC is completely phased out is known as the phase-out range.

|

Figure 1. Amount of the EITC for an |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Incorrectly reporting income (sometimes referred to as "income misreporting") was the most common source of error identified in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study.36 Income can be overreported or underreported to increase the value of the credit. For tax filers with earnings below the earned income amount, overreporting income can result in a larger credit.37 In contrast, tax filers whose income is above the phase-out threshold amount may receive a larger credit if they underreport their income. Income underreporting may be more common than overreporting since the majority of EITC claimants—51.8% of claimants in 2008—have income that places them in the phase-out range of the credit.38

Study Results

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that errors in income reporting were the second-largest source of EITC overclaims, in terms of dollar amounts of overclaims. Specifically, the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that of the total dollar amount overclaimed, 35% was associated with income reporting errors, averaging $807 per return in overclaimed credit.39 (These estimates reflect overclaims from known errors where a taxpayer selected for the audit fully participated in the audit. Hence, these numbers are not comparable to the "high" and "low" estimates provided in Table 1.) In terms of number of returns with an EITC overclaim, known errors related to incorrectly reporting income were the most common error and found on 58% of returns with an EITC overclaim.40

As illustrated in Table 2, the most frequent type of income reporting error in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study was incorrectly reporting earned income, primarily self-employment income. According to estimates based on audit results, $3.7 billion to $4.5 billion in EITC overclaims were attributable to incorrectly reporting earned income, of which between $3.2 billion and $3.8 billion was associated with self-employment income misreporting. Incorrectly reporting wage income was the smallest contributor to income reporting overclaims.

Table 2. Frequency and Amount of Major

Income Reporting Errors by Type of Error

2006-2008 annual average

|

Total Overclaimed Dollars |

|||

|

Types of Income Reporting Error |

Number of Returns with Error |

Low Estimate |

High estimate |

|

All Income Reporting Errors |

6.5 |

$4.5 |

$5.6 |

|

Earned Income Reporting Errors |

4.5 |

$3.7 |

$4.5 |

|

Wage Income |

1.7 |

$0.8 |

$1.1 |

|

Self-Employment Income |

3.1 |

$3.2 |

$3.8 |

|

AGIb, Investment Income Reporting errors |

3.1 |

$1.1 |

$1.5 |

Source: Table 5 of the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/EITCComplianceStudyTY2006-2008.pdf.

Notes: According to the IRS, the values for all income reporting errors are not equal to the sum of the different types of income reporting errors since more than one type of error may occur on a tax return. Estimates of the dollar amounts of overclaims by error type are calculated assuming a particular error type is the only error eliminated.

a. These estimates are the "high estimate." A low estimate for each error type is not available.

b. Adjusted gross income, AGI, is equal to total income net of total above-the-line deductions. For purposes of the phase-out of the EITC only, taxpayers must use earned income or AGI, whichever is greater, to determine the value of the credit.

The major sources of income reporting errors are different from the major sources of income among EITC claimants. Most EITC recipients—76%—only have wage income. In contrast, 24% earn at least some self-employment income and 10% report both wages and self-employment income.41 Hence, the majority of income reporting errors come from a minority of taxpayers, namely those with self-employment income.

Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

In the administration of the EITC, some observers have suggested that the IRS may be able to compare income reported on the tax filer's tax return to information reported on third-party forms. In other cases—especially among the self-employed—the IRS may have incomplete information. Self-employed individuals generally have their compensation reported on a Form 1099. But this compensation does not necessarily represent self-employment income. Taxpayers may deduct a variety of business expenses from their compensation to determine their self-employment income. The IRS, however, does not receive third-party verification of these deductible expenses when a taxpayer files his or her income tax return. In contrast, wage income is directly reported on form W-2 and is provided to both the taxpayer and the IRS. Indeed, the availability of wage income information to both the taxpayer and the IRS may be a factor in the lower dollar amount of overclaims attributable to wage income reporting errors.

Before 2017, another challenge in detecting this type of error was the time gap between when the IRS processes tax returns and when it receives third-party reporting data on income. (As previously discussed, wage income is reported on the Form W-2 and other forms of compensation are reported on other forms like the 1099-MISC). One GAO study found that in 2012, for example, the "IRS issued 50% of tax year 2011 refunds to individuals by the end of February, but had only received 3% of information returns."42

The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (PATH Act; Division Q of P.L. 114-113) included a provision requiring the IRS to hold income tax refunds until February 15 if the tax return included a claim for the EITC (or the additional child tax credit, known as the ACTC).43 This provision was coupled with a requirement that employers furnish the IRS with W-2s and information returns on nonemployee compensation (e.g., 1099-MISCs) earlier in the filing season. These legislative changes were made "to help prevent revenue loss due to identity theft and refund fraud related to fabricated wages and withholdings."44 With more time to cross-check income on information returns, it is believed that this will help reduce erroneous payments of the EITC by the IRS. This change began in 2017 (affecting 2016 income tax returns). As of yet, there is no research indicating if and to what extent these legislative changes have reduced the frequency or dollar amount of this type of error.45

Filing Status Errors

The EITC can be claimed by taxpayers filing their tax return as married filing jointly, head of household, or single. Tax filers cannot claim the EITC if they use the filing status of married filing separately.

The EITC's value depends in part on the tax filer's filing status. Notably, as a result of the structure of the EITC, certain married tax filers may receive a smaller EITC as a married couple than the combined EITC they would receive as two unmarried individuals—often referred to as the EITC "marriage penalty." For example, in 2014, two single parents, each with one child and earned income of $15,000, would receive an EITC of $3,305 each for a total EITC of $6,610. If they married, their combined income would be $30,000, and with two children their EITC would be $4,041.46 The EITC marriage penalty for this couple would be $2,659. (While some EITC claimants are subject to a marriage penalty, and hence may have an incentive to claim the credit as unmarried, other tax filers may be subject to an EITC marriage bonus. These recipients receive a larger credit as a married couple than their combined credit as two singles.)47 The IRS states that most EITC filing status errors arise as a result of a married couple filing two separate returns as unmarried tax filers. In other words, most filing status errors likely occur among married tax filers subject to a marriage penalty and who incorrectly file as "head of household" or "single," when they should file as married filing jointly.

Study Results

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study found that filing status errors were the third-largest EITC error in dollar terms, accounting for between $2.3 billion and $3.3 billion of EITC overclaims, illustrated in Table 1. According to the study results, filing status errors fall "somewhere between self-employment income misreporting and other types of income misreporting in relative importance."48 In many cases where the wrong filing status was used, "using the proper filing status would have substantially reduced the amount of the EITC received or made those taxpayers ineligible for the credit altogether."49 Unlike qualifying child and income reporting errors, a more detailed evaluation of this EITC error was not provided by the IRS in this study.

EITC Errors: Fraud or an Honest Mistake?IRS studies on factors leading to improper payments or overclaims of the EITC generally do not differentiate between intentional errors—fraud—versus unintentional mistakes. For example, if a non-custodial parent claimed a child for the EITC, it is unclear whether they did so intentionally to get a bigger credit or whether they simply assumed they were eligible for the credit because they claimed other child-related tax benefits for the same child. Research from the 1990s suggests that unintentional errors may be the majority of errors in the EITC, as errors in claiming children for example "are correlated with low levels of education, income, and wealth, perhaps because less-educated taxpayers are more likely to make unintentional errors."50 Another study found that for every 24 cents of improper EITC payments that went to ineligible taxpayers, 11 cents went to taxpayers fraudulently claiming a qualifying child and 13 cents went to those making inadvertent errors.51 Until it is known to what extent EITC errors are intentional versus unintentional, it is difficult to determine the most appropriate policy response. Insofar as errors are due to fraud, increasing enforcement activities and auditing could be an appropriate response. However, insofar as errors are due to "honest mistakes," it could be beneficial to simplify some of the rules related to the EITC. It also may be useful to increase educational outreach, since tax filers tend to cycle in and out of the EITC. Recent estimates suggest that a third of tax filers who claim the EITC in a given year have not claimed the credit the previous year.52 They may be unfamiliar with the eligibility rules and may claim the credit based on incorrect information. |

Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

When taxpayers file their income tax returns, they must select the appropriate filing status based on their marital status and the presence of dependent children. The IRS does not request third-party documentation to verify a taxpayer's marital status during filing season. Indeed, such a request could be viewed as intrusive and burdensome. Instead, the IRS may use marital data from the Social Security Administration to flag questionable returns. There is currently a lack of public information on how the IRS may detect filing status errors.

Paid Tax Preparer Errors

Historically, a majority of EITC claimants—approximately two-thirds—have used a paid tax preparer.53 EITC recipients may use paid preparers for a number of reasons, including

- the belief that having their tax return prepared by a paid preparer will result in a larger tax refund and fewer errors,

- the belief that refunds are received faster when the return is prepared by a paid preparer,

- language differences or taxpayer literacy problems,

- the IRS's close review of EITC returns or the belief that using a paid preparer will reduce the chance of audit,

- less effort (work) by the tax filer, and

- the incorrect belief that the paid preparer (and not the taxpayer) will pay any penalty associated with an error.

However, use of a paid tax preparer does not guarantee an accurate tax return as tax preparers vary in terms of training and experience.

Study Results

The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study collected data on both the usage of different types of paid preparers among EITC claimants, and overclaims among these different types of preparers, as illustrated in Table 3. The data indicate that among those who reported using a paid preparer, EITC claimants were more likely to use an unenrolled agent54 or tax preparer from a national tax preparation company (43% and 35%, respectively) compared to non-EITC claimants (28% and 14%, respectively). Notably, unenrolled preparers have a higher frequency of overclaims (between 49% and 54% of EITC returns prepared by these preparers had an overclaim) than almost all other types of paid preparers, including attorneys (35%), CPAs (between 47% and 49%), and enrolled agents (between 42% and 46%). Volunteer tax preparation services provided by the IRS had the lowest frequency of overclaims (between 20% and 26% of EITC returns prepared by IRS volunteer programs had an overclaim).

EITC returns prepared by unenrolled agents also account for the highest percentage of overclaim dollars (the ratio of total overclaim dollars to total claim dollars, by preparer). The IRS estimates that of the $14.5 billion of EITC claimed on tax returns prepared by unenrolled agents, between $4.7 billion and $5.8 billion (33% to 40%) was overclaimed. In comparison, the IRS estimates that between $2.4 billion and $3.6 billion (20% to 30%) of the $11.8 billion of EITC claimed on tax returns prepared by national tax return preparation firms was overclaimed. Tax returns prepared by IRS volunteer services processed $0.8 billion of EITC claims, of which between 11% and 13% was overclaimed.

Table 3. Tax Preparers Used by EITC Claimants and Percentage of Prepared Returns with Overclaims, by Type of Preparer

2006-2008 Annual Average

|

Returns w/o EITC |

Returns w/ EITC |

||||||

|

Type of Preparer |

% of All Returns |

% of Returns Using a Known Paid Preparera |

% of All Returns |

% of Returns Using a Known Paid Preparera |

% of Returns w/ Overclaims |

Dollar Overclaims as % of Total Claims |

Total Claims (Billions of Constant 2008 $) |

|

Self-Preparedb |

43% |

— |

29% |

— |

39%-47% |

28%-39% |

$12.0 |

|

IRS VITA/TCEc |

2% |

— |

3% |

— |

20%-26% |

11%-13% |

$0.8 |

|

Paid Preparer |

55% |

— |

68% |

— |

44%-51% |

29%-39% |

$36.4 |

|

Attorney |

1% |

2% |

0% |

0% |

35%-35% |

28%-28% |

$0.1 |

|

CPA |

16% |

44% |

6% |

10% |

47%-49% |

27%-31% |

$2.6 |

|

Enrolled Agent |

4% |

11% |

6% |

9% |

42%-46% |

24%-29% |

$2.8 |

|

Paid Friend/Relative |

1% |

2% |

1% |

2% |

37%-37% |

19%-19% |

$0.5 |

|

National Tax Return Prep Firm |

5% |

14% |

21% |

35% |

35%-44% |

20%-30% |

$11.8 |

|

Unenrolled Return Preparer |

10% |

28% |

26% |

43% |

49%-54% |

33%-40% |

$14.5 |

|

Preparer Used, Type Unknownd |

18% |

— |

8% |

— |

51%-72% |

47%-73% |

$4.1 |

|

TOTAL |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

42%-49% |

29%-38% |

$49.1 |

Source: The Internal Revenue Service, Compliance Estimates for the Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 2006-2008 Returns, Publication 5162, Washington, DC, August 2014, Tables 8 and 9.

a. These percentages are based on data from taxpayers who reported using a particular type of paid preparer.

b. Self-prepared returns include those where the taxpayer reported receiving uncompensated assistance from another individual. For self-preparers claiming the EITYV, 28% received this assistance among those not claiming the EITC, 9% received informal assistance.

c. The majority of the returns in this category were prepared by the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program or Tax Counseling for the Elderly (TCE). Approximately 3% were prepared by the IRS via other venues.

d. The majority of the returns in the category were cases where the return was accepted as filed with no investigation into the type of preparer used. A large number of audit non-participants are also included in this group.

The IRS does not conclude that these data are sufficient to indicate which preparers tend to be less capable or unscrupulous. A 2008 Taxpayer Advocate study found that both taxpayers and tax preparers tend to fall into one of three groups: (1) those intent to commit fraud and understate their liabilities or overstate their refunds; (2) those who are indifferent and who defer decisions to the other party (i.e., the tax preparer defers to the taxpayer and vice versa); and (3) those who seek to comply with the tax laws. As this study stated, it is important to understand the dynamic relationship between taxpayers and paid preparers. Certain compliant paid preparers might choose not to assist people who seek to claim the EITC incorrectly. Conversely, a noncompliant taxpayer may seek out a noncompliant paid preparer.55 Echoing this idea, the IRS in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study notes that error rates among preparers may be influenced by selection bias. For example, taxpayers with more complicated tax returns, or who are seeking to intentionally overclaim the credit, may seek out an unenrolled agent. More research may help to determine "the relative ability or integrity of unenrolled preparers."56

Several Government Accountability Office (GAO) investigations of small samples of returns prepared by paid tax preparers have also highlighted the variability in quality and accuracy of paid tax preparation services. In a 2014 study, GAO found that of their limited sample of paid tax preparers (19), most of them (17) made some mistakes when preparing tax returns that resulted in an incorrect refund amount.57 As GAO reported, "nearly all of the returns prepared for our undercover investigations were incorrect to some degrees, and several of the preparers gave us incorrect advice, particularly when it came to reporting non-Form W-2 income (i.e., wage income) and the EITC. Only 2 of the 19 tax returns showed the correct refund amount."58 The report also found that in 3 out of 10 cases, the tax preparers claimed an ineligible child for the EITC.59 In other cases, the tax preparers did not report cash tips of the taxpayer, leading to overstated refunds. Overstated refunds resulting from these two errors ranged from $654 (underreporting income) to $3,718 (underreporting income and claiming an ineligible child).

Challenges in Detecting and Reducing the Error

There have been a variety of proposals to improve the quality of services by paid tax preparers and to increase compliance among these preparers. Under current law, since 2011 paid tax preparers who prepare returns which include an EITC claim must follow several due diligence requirements, including the following:

- Completing IRS Form 8867 and filing this form with each tax return they prepare. Form 8867 is a checklist for the preparers asking questions concerning the taxpayer's filing status, income, and any children claimed for the credit.60

- Completing an EITC worksheet found in the Form 1040 instructional booklet.

- "Tak[ing] steps to ensure that all taxpayer information provided to them is correct and complete by asking follow-up questions to the taxpayer and requesting additional documentation."61

Copies of all forms and relevant information must be kept by the preparer for three years. Paid preparers who do not meet these requirements can face a penalty of up to $500 for each return for which they fail to meet the due diligence requirements.

In addition, the IRS requires that any individual who prepares a tax return for compensation must obtain a Preparer Taxpayer Identification Number (PTIN).62 A PTIN is intended to enable the IRS to quickly and efficiently identify tax preparers who prepare tax returns with a high number of errors or overclaims. Some advocates, however, have pushed for more regulation at the federal level of paid preparers.63 Before January 2013, the IRS had also begun implementation of new testing and continuing education requirements for certain paid preparers not already subject to IRS oversight.64 A Treasury Inspector General Report on EITC improper payments noted that these initiatives to regulate previously unregulated preparers were "considered the most promising strategy for curbing EITC improper payments."65

However, as a result of a ruling in Loving v. Internal Revenue Service in 2013, the IRS was enjoined from enforcing these new requirements.66 Ultimately, the IRS chose not to appeal the decision in Loving.67 The IRS does provide a voluntary education and testing program for unregulated preparers.68

Nonetheless, the IRS Taxpayer Advocate stated at a 2014 hearing,69

The single most useful step Congress can take to improve EITC compliance and reduce Improper Payments is to enact a regulatory regime that requires unenrolled preparers who prepare returns for a fee to demonstrate minimum levels of competency by passing an initial test and then taking annual continuing education courses (including ethics).

Congress has in the past introduced legislation that would give the IRS the statutory authority to regulate paid tax preparers, including S. 832 in the 109th Congress and S. 1219 in the 110th Congress. More recently, the Senate Finance committee held a hearing in 2014 concerning paid preparers. At that hearing the IRS Commissioner requested Congress provide the IRS with the explicit legal authority to regulate currently unregulated tax preparers.70 In his FY2019 budget proposal, President Trump proposed increasing oversight of paid tax preparers, noting that "[e]nsuring that these preparers understand the tax code would help taxpayers get higher quality service and prevent unscrupulous tax preparers from exploiting the system and vulnerable taxpayers."71 To date in the 115th Congress, no legislation has been introduced to regulate paid tax preparers.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, the recent EITC compliance study found that the most common error tax filers make when claiming the EITC is incorrectly reporting income. The largest EITC error in dollar terms is incorrectly claiming a child for the credit. The 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study however, did not provide estimates of what proportion of EITC errors were due to taxpayer confusion versus intentional error (i.e., fraud). This may be of particular interest to policymakers seeking to reduce EITC errors because the strategies to reduce "honest mistakes" versus "fraud" differ. Insofar as these errors are due to taxpayer (or paid tax preparer) confusion with the EITC eligibility rules, the most effective policy response may be to simplify these rules and create greater uniformity for all child-related tax benefits in conjunction with increasing taxpayer education on EITC eligibility. This may be particularly relevant for EITC claimants given that about one-third of the EITC claimants in a given year did not participate in the program the previous year72 and may be unfamiliar with the complex eligibility requirements of the credit.

Increasing enforcement activities and auditing could be the best policy response for errors resulting from fraudulent claims of the credit. The IRS would need data on taxpayers' compliance with EITC parameters (e.g., whether the child claimed was a qualifying child) to enforce the rules of the credit. However, the IRS currently may not have sufficient information to verify qualifying child eligibility and self-employment income. The issues surrounding the IRS ability to detect and correct EITC errors highlight a more general problem with administering complex provisions like the EITC—the lack of accurate and timely third-party data to verify complex eligibility rules. The IRS's budgetary constraints may also hinder enforcement activities. Problems with administration of the EITC also highlight more general problems of administering a variety of child-related tax benefits (like the dependent exemption, the child tax credit, and the child and dependent care credit), each with slightly different eligibility rules. A taxpayer, for example, may incorrectly believe that eligibility for one child-related tax benefit, like the child tax credit, makes them eligible for the EITC, and vice versa, when that may not be the case.

There are a variety of legislative options to improve the administration of the EITC, alone and in the context of other child-related tax benefits. Congress could simplify tax provisions such that they are enforceable with current third-party data (e.g., by making the EITC purely a work-based credit, based on earnings, not qualifying children). Or Congress could simplify eligibility for all child-related tax benefits, such that a qualifying child for one benefit would be a qualifying child for all other child-related tax benefits.

The IRS's administration of the EITC has highlighted the agency's shifting role from tax collector to tax collector and benefit administrator. Unlike other agencies that administer social and economic benefit programs, the IRS does not expend significant resources to determine a taxpayer's eligibility for the EITC before a tax return is filed. Instead, taxpayers file for the EITC, and then the IRS may verify if the taxpayer is eligible for the credit. Some tax returns are checked during tax filing season and others are checked post filing season, after the credit has been paid. Minimal pre-filing eligibility verification may reduce administrative costs but also lead to substantial amounts of the credit being claimed in error.

More broadly, improper payments of refundable tax credits may increase as the number of refundable credits the IRS administers increases or participation in existing credits increases. Given the high percentage of EITC improper payments and data limitations in detecting certain EITC errors, Congress may choose to reconsider providing social benefits through the tax code in the form of refundable credits. Alternatively, if Congress remained interested in providing social benefits in the form of refundable tax credits, the IRS's mission statement could be broadened to include both tax collection and the administration of social benefits.73 Without any changes in the way the IRS administers social benefits like the EITC, improper payments of refundable credits and the suitability of the IRS in administering social benefits could continue to be a prominent issue in tax administration.74

Appendix. The Relationship Between Improper Payments and Overclaims

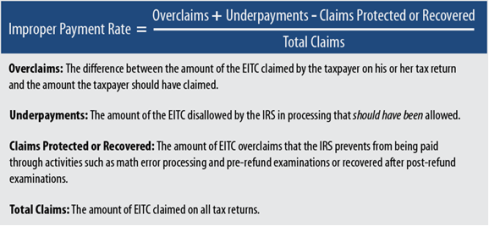

As previously mentioned, this report discusses two measures of EITC noncompliance: improper payments and overclaims. Although these two measures of EITC noncompliance are related, they do differ.

Improper payments are an annual fiscal year measure75 of the amount of the credit that is erroneously claimed and not recovered by the IRS. Overclaims and the overclaim rate are the amount of the credit claimed incorrectly on successfully processed tax returns and do not include the impact of enforcement activities.76 In addition, overclaims and the overclaim rate are generally reported less frequently than improper payments and the improper payment rate. The IRS released studies in 1999 and 2014 which examined EITC overclaims.

Improper Payments, the Improper Payment Rate, and Overclaims

EITC improper payments are defined as erroneous amounts of the credit (including both the nonrefundable and refundable portion of the credit) that are "paid out to taxpayers and are not later recovered or corrected by the IRS."77 To determine an estimate of the dollar amount of improper payments in a given fiscal year, an estimated improper payment rate is multiplied by an estimate of total EITC claims for that fiscal year.

The estimated improper payment rate is based on a sample of the most recent individual income tax reporting compliance data, which can be several years older than the estimate of total EITC claims. For example, the estimated improper payment rate used to estimate the dollar amount of improper payments in FY2012 used tax data from 2008 tax returns. This estimated improper payment rate (based on a sample of 2008 tax returns) was then multiplied by an estimate of total EITC claims for FY2012 to determine the dollar amount of improper payments for FY2012.

An EITC overclaim is "the difference between the EITC amount claimed by the taxpayer on his or her return and the amount the taxpayer should have claimed."78 To determine why some tax filers erroneously claim the EITC, the IRS examines tax returns with an EITC overclaim instead of examining returns with an improper payment. This allows the IRS to determine the factors that lead tax filers to claim the credit incorrectly. If instead, the IRS examined tax returns with EITC improper payments, their sample would exclude those tax returns whose EITC overclaims were either never paid (due to prerefund compliance checks) or were recovered (as a result of postrefund audits). Excluding these tax returns could result in inaccurate estimates of the major factors that lead to incorrect EITC claims.

Before FY2013, the EITC improper payment rate was calculated as total overclaims dollars net of EITC overclaim dollars recovered, divided by the total amount of EITC dollars claimed on all returns. Beginning in FY2013,79 the IRS's calculation of improper payments includes underpayments. EITC underpayments are "the amount of the EITC disallowed by the IRS in processing that should have been allowed."80 Under this new calculation of the improper payment rate, the dollar amounts of underpayments and overclaims are added together and the total amount of recovered EITC overclaims is then subtracted from this sum (see Figure A-1). This modification has a small effect on the improper payment rate, with Treasury noting that "underpayments increase the overall improper payment rate by less than 0.05 percent."81

|

|

Source: Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA). Notes: This formula reflects the formula used for FY2013 and subsequent estimates of improper payments. |

Do Improper Payments Measure the Cost of EITC Noncompliance to the Government?

The cost of EITC errors to the Treasury equals credit overpayments (overclaims net any overclaims blocked or which were recovered by compliance measures) net of any underclaims or offsetting errors. An underclaim is the amount of the credit a taxpayer is entitled to claim but neglects to claim, and includes eligible taxpayers who fail to claim the credit entirely as well as those who claim less than they should. An offsetting error is an underclaim that may partially or fully offset an overclaim. For example an offsetting error occurs when a child claimed in error by taxpayer A could have been correctly claimed by taxpayer B, but taxpayer B did not claim that child. Depending on the size of underclaims and offsetting errors, estimated improper payments "may or may not represent a loss to the government."82

For example, if tax filers overclaimed $10 billion of the EITC (net of amounts never paid or recovered), but $2 billion of the credit was never claimed by eligible claimants, the net amount of the credit paid in error would be $8 billion. When underclaims are large in relation to overclaims, improper payment amount may overstate the cost of EITC errors to the Treasury. When underclaims are relatively small compared to overclaims, improper payment amounts may be accurate approximations of the cost of EITC errors to the Treasury. Currently, there are no publicly available estimates of underclaims and offsetting errors. The IRS does estimate that 21% of eligible EITC claimants do not claim the credit.83 However, an estimate of the amount of EITC dollars underclaimed by these 21% of eligible recipients is not currently available.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Any amount of the credit which is greater than a recipient's tax liability is claimed as a refund on his or her income tax return. |

| 2. |

Department of the Treasury, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2017, November 14, 2017, p. 174, https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/annual-performance-plan/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 3. |

Improper payments and the improper payment rate must by law be reported annually by a variety of agencies for a variety of programs (P.L. 107-300 as amended by P.L. 111-204 and P.L. 112-248). For more information about the legal requirements of agencies concerning improper payments, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, Improper Payments: Government-Wide Estimates and Reduction Strategies, GAO-14-737T, July 9, 2014, pp. 2-3, http://www.gao.gov/assets/670/664692.pdf. |

| 4. |

The Internal Revenue Service, Compliance Estimates for the Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 2006-2008 Returns, Publication 5162, Washington, DC, August 2014, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/EITCComplianceStudyTY2006-2008.pdf, p. 2. |

| 5. |

For FY2017, the Treasury department estimated the dollars of improper payments by applying improper payment rates estimated from tax year 2013 data—21.9% and 25.8% accounting for sampling error— to the estimated FY2017 level of EITC claims ($68.0 billion). In describing how it calculated the tax year 2013 improper payment rates, the Treasury Department stated, "The EITC improper payment rate is estimated using a statistically valid sample of about 2,700 returns audited through the IRS's NRP [National Research Program]. This sample is sufficient to estimate the improper payment rate with plus or minus 2.5 percentage point precision and 90 percent confidence. For TY 2013 (the most recent study completed), the estimated gross amount of improper payments was $18.0 billion and the total amount of EITC claimed was $66.8 billion. The amount of erroneous EITC payments prevented or recovered on TY 2013 returns was $2.1 billion. This results in a net improper payment amount of $15.9 billion, or 23.9 percent of the total EITC claimed (or between 21.9 percent and 25.8 percent, accounting for sampling error)." Department of the Treasury, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2017, November 14, 2017, p. 174, https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/annual-performance-plan/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 6. |

Generally tax provisions are scored as a reduction of revenue. The refundable portion of the EITC however is designated as an outlay, and hence comparable to a spending program. However, noncompliance with other tax laws can result in reduced revenue. The OMB Payment Accuracy does not compare noncompliance in spending programs (improper payments) to noncompliance in tax programs (foregone revenue). |

| 7. |

For more information, see the U.S. Government's Payment Accuracy website at https://www.paymentaccuracy.gov/high-priority-programs. |

| 8. |

House Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Oversight, Written Statement of Nina E. Olson, National Taxpayer Advocate, Hearing on Improper Payments in the Administration of Refundable Credits, http://waysandmeans.house.gov/uploadedfiles/olsen_testimony.pdf, May 25, 2011, p. 9. |

| 9. |

Department of the Treasury, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2017, November 14, 2017, p. 137, https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/annual-performance-plan/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 10. |

The Internal Revenue Service, Federal Tax Compliance Research: Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2008-2010, Publication 1415 (5-2016) Catalog Number 10263H, May 2016, p. 7. |

| 11. |

Taxpayer Advocate Service, Fiscal Year 2015 Objectives Report to Congress: Research Initiatives, Washington, DC, p. 158, http://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/userfiles/file/FY15-Full-Report/Research.pdf. |

| 12. |

These estimates are based on tax gap estimates for tax year 2006, which are not as current as the annual average estimates for tax years 2008 through 2010 cited earlier in this report. For tax year 2006, the net tax gap was estimated to be $385 billion, with $122 billion estimated to be from the underreporting of business income on individual income tax returns, and underreporting on corporate tax returns resulting in $67 billion of the tax gap. The Internal Revenue Service, IRS Releases New Tax Gap Estimates; Compliance Rates Remain Statistically Unchanged from Previous Study, IR-2012-4, January 6, 2012, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-releases-new-tax-gap-estimates-compliance-rates-remain-statistically-unchanged-from-previous-study. |

| 13. |

In addition to the major factors identified in the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance Study that lead to EITC overclaims, the study also identified other minor factors that lead to erroneous claims of the credit. These include errors in applying EITC tie-breaker rules when more than one person can claim a qualifying child, not having a valid Social Security number (SSN), not being a U.S. citizen or resident, not being age 25-64 if claiming the childless EITC, and being the dependent of another taxpayer. In the 2006-2008 EITC Compliance study approximately 700,000 returns annually included one of these errors, resulting in overclaims of between $900 million to $1.4 billion annually. In comparison, the total number of returns with overclaims is estimated at 11.9 million, resulting in between $14.0 billion to $19.3 billion in overclaims annually. |

| 14. |

This includes individual income tax returns, corporate tax returns, estate and gift tax returns, employment tax returns, and excise tax returns. |

| 15. |

The Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Service Databook, 2017, September 30, 2017, Table 9a, available for download at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-irs-data-book/. |

| 16. |

The Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Service Databook, 2017, September 30, 2017, p. iii, available for download at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-irs-data-book. |

| 17. |

Additional tax owed may be a combination of a smaller EITC and a large income tax liability. The Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Service Databook, 2017, September 30, 2017, Table 9a, available for download at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-irs-data-book/. |

| 18. |

House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government, Written Statement of Nina E. Olson National Taxpayer Advocate, Hearing on Internal Revenue Service Oversight, 113th Cong., February 26, 2014, http://www.irs.gov/pub/tas/nta_testimony_houseppprops_oversight_022614.pdf, footnote 107, p. 35. |

| 19. |

See the Internal Revenue Service website http://www.eitc.irs.gov/Tax-Preparer-Toolkit/dd/consequences. |

| 20. |

In cases where a child is the qualifying child of more than one taxpayer and only one of the taxpayers is the child's parent, under the tie-breaker rules for the credit that parent has priority in claiming the child for the credit. However, that does not mean that the parent is required to claim the child for the credit. For more information on the EITC tie-breaker rules, see the IRS's EITC Central webpage at http://www.eitc.irs.gov/EITC-Central/abouteitc/basic-qualifications/tiebreaker. |

| 21. |

Qualifying children who reside with a service member who is stationed outside the United States while serving on extended active duty with the U.S. Armed Forces are considered to reside in the United States for the purposes of the EITC. |

| 22. |

Per IRC §32(c)(3)(A) and its reference to IRC §152(c), a full time student is defined as being at an educational institution for at least five months out of the year in which the credit is claimed. |

| 23. |

This excludes qualifying child errors that occur alongside income reporting errors, but does include qualifying child errors that occur in conjunction with other errors, like using an incorrect filing status. |

| 24. |

National Taxpayer Advocate, Fiscal Year 2015 Objectives: Report to Congress, June 30, 2014, p. 124, http://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/userfiles/file/FY15-Full-Report/The-Earned-Income-Tax-Credit-is-an-Effective-Anti-Poverty-Tool-That-Requires-a-Non-Traditional-Compliance-Approach-by-the-IRS.pdf. |

| 25. |

National Taxpayer Advocate, Fiscal Year 2015 Objectives: Report to Congress, p. 126. |

| 26. |

Other EITC qualifying child errors could include errors related to the age test and SSN test for the qualifying child. |

| 27. |

Compliance Estimates for the Earned Income Tax Credit Claimed on 2006-2008 Returns. (2014), p. 23. |

| 28. |

V. Joseph Hotz and John Karl Scholz, "Can Administrative Data on Child Support Be Used to Improve the EITC? Evidence from Wisconsin," March 2008, http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~scholz/Research/EITC_Admin.pdf, p. 2. |

| 29. |

In this instance, "summarily deny" means that the IRS identifies the error, adjusts the amount of the credit based on that error and then sends a notice to the EITC claimants indicating the correction has occurred. "Taxpayers then have 60 days to contest the assessment outlined in those notices. Further, if they do not contest the assessment within that time, they lose their right to file an appeal with [the] IRS or the U.S. Tax Court but have the option of filing an amended tax return to be considered by [the] IRS." See U.S. Government Accountability Office, Enhanced Prerefund Compliance Checks Could Yield Significant Benefits, GAO-11-691T, May 25, 2011, p. 4, http://www.gao.gov/assets/130/126283.pdf. |

| 30. |

For a description of this IRS study, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, Refundable Tax Credits: Comprehensive Compliance Strategy and Expanded Use of Data Could Strengthen IRS's Efforts to Address Noncompliance, GAO-16-475, May 2016. |

| 31. |

National Taxpayer Advocate, Fiscal Year 2012 Objectives: Report to Congress, June 30, 2011, p. 8, http://www.irs.gov/pub/tas/fy2012_ntaobjectives.pdf. |

| 32. |

Janet Holtzblatt, The Challenges to Implementing Health Reform Through the Tax System, The Tax Policy Center, February 2008, p. 9, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/tpccontent/healthconference_holtzblatt.pdf. |

| 33. |

House Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Oversight, Written Statement of Nina E. Olson National Taxpayer Advocate, Hearing on Improper payments in the Administrations of Refundable Credits, 112th Cong., May 25, 2011, p. 10. |

| 34. |