FEMA Disaster Housing: The Individuals and Households Program—Implementation and Potential Issues for Congress

Following a major disaster declaration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may provide three principal forms of assistance. These include Public Assistance, which addresses repairs to a community and states’ or tribe’s infrastructure; Mitigation Assistance which provides funding for projects a state or tribe submits to reduce the threat of future damage; and Individual Assistance (IA) which provides help to individuals and families.

IA can include several programs, depending on whether the governor of the affected state or the tribal leader has requested that specific help. These can include Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA) for workers made unemployed by a disaster and not covered by the state’s standard unemployment program. IA can also include Crisis Counseling that provides assistance to state and local mental health organizations to assist disaster victims traumatized by an event. IA may also include Case Management services that help a state to organize potential forms of assistance for disaster survivors.

All of those programs can perform important tasks in the post-disaster environment to aid disaster survivors in reorienting their lives and returning to normal. But the principal IA program to offer such assistance is the Individuals and Households Program (IHP), authorized by Section 408 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The IHP provides temporary housing assistance as well as the Other Needs Assistance (ONA) grants that can provide necessary assistance for the replacement of lost items such as furniture and clothing. Funds to assist any household are currently capped at $33,000. This amount is adjusted annually according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Federal disaster housing assistance has a long history that is not always best understood by concentration on the exceptional circumstances presented by Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. In fact, the Hurricane Sandy experience of the last several years may serve as a better guide to explain the form FEMA housing assistance takes in most disaster recovery operations.

While the Katrina experience suggested a general reliance on motel rooms, travel trailers, mobile homes, and even docked cruise ships, the great majority of disaster housing help comes in the form of repairs to a home to make it habitable and financial assistance to cover the cost of temporary rental units, such as available apartments in the disaster area. The use of mobile homes and travel trailers, what FEMA terms “direct assistance,” is rare and generally considered a last resort to be employed only when other housing options are not available in the immediate disaster area. But improvements have been made in this form of assistance and are reviewed here.

This report explains the traditional approach for temporary housing through the IHP program following a disaster, how it is implemented, and considers if the current policy choices are equitable for disaster victims. As a part of this examination, the report looks at other forms of housing repair assistance such as the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program for homeowners as well as assistance that is provided, in some instances, through the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant (CDBG-DR) program.

In recent years FEMA has catalogued its use of various forms of housing and the associated costs of each. This report will review those expenditures and provide information on the relative costs, and applications of, several categories of assistance.

FEMA Disaster Housing: The Individuals and Households Program—Implementation and Potential Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Section 408—Individuals and Households Program (IHP)

- Housing Assistance

- Monetary Assistance

- Direct Assistance

- Repairs

- Replacement

- Financial Assistance to Address Other Needs

- Case Management Services

- The IHP Process

- IHP Activation

- Appropriate Housing Assistance

- Increasing Housing Resources

- Housing Assistance Provided by Category

- FEMA Direct Assistance: Manufactured Housing Units

- Potential Issues for Congress

- Equity in Disaster Housing Assistance

- CDBG-DR Availability

- Group Flood Insurance Linkages

- Maximum Amount of Assistance

- The STEP Program Availability

- Condos and Co-ops Eligibility

- The Sequencing of Housing Assistance

- The State Role in Disaster Housing

- Summary Considerations

Summary

Following a major disaster declaration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may provide three principal forms of assistance. These include Public Assistance, which addresses repairs to a community and states' or tribe's infrastructure; Mitigation Assistance which provides funding for projects a state or tribe submits to reduce the threat of future damage; and Individual Assistance (IA) which provides help to individuals and families.

IA can include several programs, depending on whether the governor of the affected state or the tribal leader has requested that specific help. These can include Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA) for workers made unemployed by a disaster and not covered by the state's standard unemployment program. IA can also include Crisis Counseling that provides assistance to state and local mental health organizations to assist disaster victims traumatized by an event. IA may also include Case Management services that help a state to organize potential forms of assistance for disaster survivors.

All of those programs can perform important tasks in the post-disaster environment to aid disaster survivors in reorienting their lives and returning to normal. But the principal IA program to offer such assistance is the Individuals and Households Program (IHP), authorized by Section 408 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The IHP provides temporary housing assistance as well as the Other Needs Assistance (ONA) grants that can provide necessary assistance for the replacement of lost items such as furniture and clothing. Funds to assist any household are currently capped at $33,000. This amount is adjusted annually according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Federal disaster housing assistance has a long history that is not always best understood by concentration on the exceptional circumstances presented by Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. In fact, the Hurricane Sandy experience of the last several years may serve as a better guide to explain the form FEMA housing assistance takes in most disaster recovery operations.

While the Katrina experience suggested a general reliance on motel rooms, travel trailers, mobile homes, and even docked cruise ships, the great majority of disaster housing help comes in the form of repairs to a home to make it habitable and financial assistance to cover the cost of temporary rental units, such as available apartments in the disaster area. The use of mobile homes and travel trailers, what FEMA terms "direct assistance," is rare and generally considered a last resort to be employed only when other housing options are not available in the immediate disaster area. But improvements have been made in this form of assistance and are reviewed here.

This report explains the traditional approach for temporary housing through the IHP program following a disaster, how it is implemented, and considers if the current policy choices are equitable for disaster victims. As a part of this examination, the report looks at other forms of housing repair assistance such as the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program for homeowners as well as assistance that is provided, in some instances, through the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) Community Development Block Grant (CDBG-DR) program.

In recent years FEMA has catalogued its use of various forms of housing and the associated costs of each. This report will review those expenditures and provide information on the relative costs, and applications of, several categories of assistance.

Section 408—Individuals and Households Program (IHP)

Housing assistance for families and individuals following a presidentially declared disaster event dates back to 1951 when special legislation (H.J. Res. 303) in response to flooding in the Midwest included a provision for "providing temporary housing or other emergency shelter for families who, as a result of such major disaster, require temporary housing or other emergency shelters."1 This authority, which derived from P.L. 81-875, the Federal Disaster Act of 1950, was only sporadically employed over the next two decades.2

But in the intervening years, Congress created various forms of aid to assist those who had lost their homes and their livelihood to disasters. During the late 1960s the disaster loan program of the Small Business Administration (SBA) was created as well as the Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA) program.3 In 1974, the Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288) was enacted that established the IHP program (known initially as Individual and Family Grants—IFG) in the general form that it is recognized today.

The IHP has two broad categories that assist families and individuals who have been impacted by disaster damage; housing assistance and other needs assistance. The total of all assistance to one household cannot exceed $33,000.4 Each household is considered a single applicant regardless of the number of household members.5 In all instances, this help is intended to supplement, but not substitute for existing insurance coverage.

Housing Assistance

Under Section 408, all housing costs are assumed by the federal government for up to 18 months. The types of assistance include monetary assistance, direct assistance, repairs and replacement.

Monetary Assistance

Monetary Assistance is provided to families and individuals to address the costs to rent alternative housing which can be homes, apartments, fabricated dwellings, or other available housing resources. The amount of the assistance is calibrated to include housing and utility costs in the affected area. It may be possible, in accordance with the section's authority, that multiple types of assistance may be provided based on what meets the needs of the individuals and households.6 For example, a family could receive limited monetary assistance for rent while repairs to the home are being made. Similarly, an applicant could also receive the use of manufactured housing while repairs are being made to their primary residence.

Direct Assistance

Direct assistance provides temporary housing units to disaster survivors that are purchased or leased by the federal government. The government may place the units in existing mobile home parks or create new sites for the units. The IHP cost per household limit does not apply to this category since purchase costs for units could exceed that amount.

Repairs

Repairs are the preferred form of assistance: making the survivors' home habitable and returning them to familiar housing in their community. Such help may keep an individual or family close to their employment or schools. These repairs may also include mitigation measures to make the house less susceptible to future damage. These tend to be repairs that can be accomplished rapidly to return the home to use. This type of assistance does not include new utilities or improvements to the home, but does make the home conform to current, applicable building codes in the affected area.

Replacement

In this form of assistance, the IHP makes a contribution toward the replacement of an owner-occupied residence that was lost in a disaster event. Given the limitation on IHP funding amounts for each household, IHP awards will not likely pay for the full replacement of a residence. However, in the case of fabricated dwellings, for example, this amount may make a substantial payment toward such a purchase.

Financial Assistance to Address Other Needs

For assistance with other needs, Section 408 includes the Other Needs Assistance (ONA) program. Unlike housing, ONA is cost-shared with the state government on a 75% federal, 25% state basis. The program is intended to address specific needs created by the disaster's impact. Assistance under ONA can include clothing, furniture, funeral expenses, emergency medical help, and other needs.7 As noted above, ONA help could be one of multiple types of assistance that might be provided. This is dependent on what is most suitable to meet the needs of the household in the particular disaster situation.

One unique form of assistance that is eligible for ONA funding are the group flood insurance policies offered by FEMA after major flood disasters.8 The entire premium per household is $600 which is paid from ONA funds. The state provides the names of the households to be included in the group policy to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). These are households that have received assistance under the IHP program. Essentially, the policy is covering the maximum amount of IHP awards (currently $33,000). The term of the policy is for 36 months and begins 60 days after the date of the applicable disaster declaration. FEMA provides a certificate of coverage to each household. FEMA will again contact the household 60 days before the policy is slated to expire. That notice will include encouragement to the household to contact an insurance broker to obtain a standard flood insurance policy.

Case Management Services

A companion to the provision of IHP services is the authority for states to request Case Management Services to assist families and individuals in organizing assistance and ensuring that they are accessing the various forms of help that may be available. The governor of an impacted state may request the implementation of Disaster Case Management (DCM) in the event of a presidentially declared disaster that includes Individual Assistance. DCM allows for immediate services to address disaster-caused unmet needs, such as technical assistance, outreach, initial triage, and disaster case management casework. The DCM program may also provide for Disaster Case Management State Grants, which may allow for DCM providers to supply services to survivors with long-term disaster-caused unmet needs. This program can be helpful to IHP clients working to reestablish their pre-disaster lives and assist them in understanding both the potential and limits of IHP assistance.9

The IHP Process

Assistance to individuals and households is not automatic under a presidential declaration. It must be specifically requested by the governor in his or her letter of request.10 The governor's request would also include estimates of need based on a preliminary damage assessment (PDA).11 The PDA includes estimates of the number of homes affected, the degree of damage, the estimated amounts of insurance coverage, and other demographic information such as household income and percentages of elderly residents. FEMA has provided an operations manual for damage assessment by the state that details the factors that need to be validated in a request for Individual Assistance (IA):

- Cause of damage

- Jurisdictions impacted and concentration of damage

- Types of homes

- Homeownership rate of impacted homes

- Percentage of affected households with insurance coverage appropriate to the peril

- Number of homes impacted and degree of damage

- Inaccessible communities

- Special Flood Hazard Areas, sanctioned communities, Coastal Barrier Resource System zones and other protected areas

- Primary or secondary residence

- Other relevant PDA data, such as income levels, poverty, trauma, and special needs.12

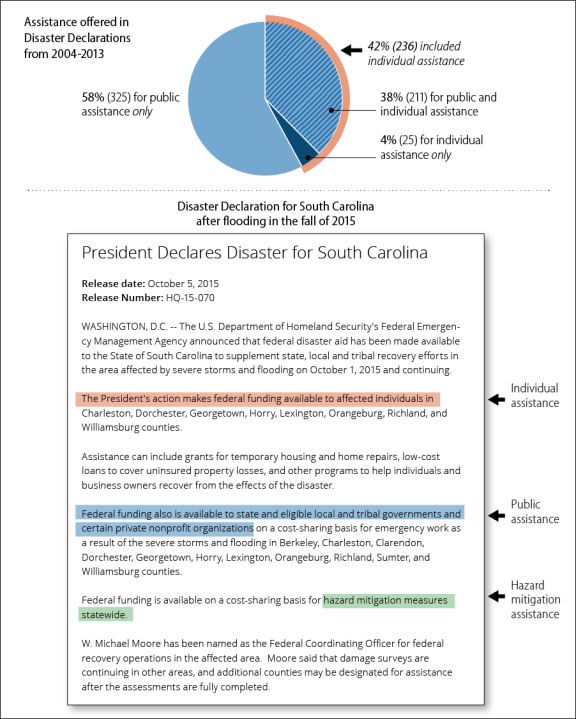

During the period 2004 through 2013 there were 561 major disaster declarations. Of that total, 211 declarations were made for both Public Assistance (PA) and IA while 25 declarations were made for IA only. The remaining 325 declarations were for PA only.13 Just over 40% of all presidential major disaster declarations during this period resulted in a designation for IA. The declarations contain the designations of the areas covered (e.g., counties) by the declaration and the types of assistance (PA and/or IA) available. For example, the pie chart at the top of Figure 1 reflects that division of the types of assistance provided under the declarations and the example below it is a major disaster declaration for South Carolina during the fall of 2015 (DR-4241-SC) that illustrates how the types of assistance are mentioned within a declaration, including the designation of counties. The designations indicate the types of assistance being provided for individual counties within a state or tribal areas. Both the initial county designations, and any subsequent additions, are published in the Federal Register.

IHP Activation

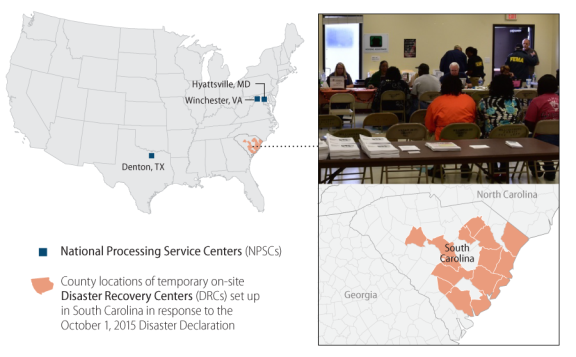

When the IA program has been designated, several steps are taken by FEMA. The activation of the program means that the National Processing Service Centers (NPSCs) are staffed up to receive applications via FEMA's 1-800 number as well as online.14 In some instances FEMA, in concert with the state, will also set up onsite Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) to accept applications in person in the designated disaster area for those without power or the ability to request help by phone or online, or simply to provide greater degree of service. These DRCs also usually include representatives from other agencies and entities such as state and local governments, the American Red Cross, SBA, and other organizations that are part of the recovery process.

The NPSCs take in the great majority of all applications. The facilities are located in Maryland, Texas, and Virginia. Trained operators work with disaster survivors to advise them of the information that they should have available, and ask a series of questions to determine eligibility.

These questions include requests for information regarding the ownership of the primary residence, the type of insurance covering the property (both homeowners and flood insurance), the number of residents in the household and the types of assistance that may be required.

A previously persistent problem (particularly during the Katrina recovery) was that some applicants claimed vacation homes as primary residences. FEMA addressed this using "Lexis/Nexis to run an occupancy check on the registrants' damaged dwelling."15 By using that system, FEMA has reduced the number of improper payments and has been able to more accurately verify the status of the dwelling.

The IHP application process can also include referrals to SBA for its disaster loan program. This is an important step since SBA loans can provide more resources to accomplish repairs than the capped IHP program. In addition, this dialogue can also inform FEMA of other needs that might be necessary, such as the Case Management program. It can also expedite the recovery process when it is clear that the applicant will not qualify for a disaster loan and thus may need extensive FEMA assistance, including ONA.

A principal result of the IA interview process is to arrange an inspection of the damaged property. During this inspection, FEMA again seeks to confirm that it is a primary residence.16 FEMA has multiple contracts with inspection companies that allow them, in most instances, to rapidly perform inspections, verify insurance information, and with more specificity, determine the ONA requirements for a given household.17 The inspectors review the damage to the home but also discuss the status of the housing with the applicant and confirm information regarding insurance coverage as well as home ownership.

|

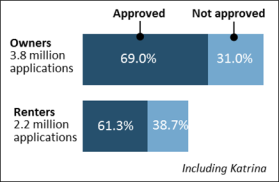

Figure 3. Application Approval, 2004-2013 Owners and Renters |

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS. Notes: Based on FEMA 2014 DATA. |

The inspections are conducted as soon as possible following the declaration. During the period of 2004-2013, about 69% of all owned homes applying for FEMA aid were approved for some form of assistance. During that same period, just over 61% of renters requesting assistance have been approved.18

Appropriate Housing Assistance

A challenge in the recovery phase of a disaster is the management of expectations. This is especially true for aid to families and individuals since the limits on the amount of aid (e.g., the $33,000 cap) are not always clear to all parties involved. But a further complication affecting expectations is the statutory authority to determine what housing help will be provided to an applicant. It is important to consider that the choices of types of assistance to be employed are at the discretion of the President (and this authority has been delegated to FEMA). While the convenience to the individual is a factor, so too are costs involved. Section 408 of the Stafford Act states that:

The President shall determine appropriate types of housing assistance to be provided under this section to individuals and households described in subsection (a)(1) based on considerations of cost effectiveness, convenience to individuals and households, and such other factors as the President may consider appropriate.19

There is, however, a process for families and individuals to appeal program determinations regarding eligibility, length, and amount of assistance and other decisions related to the IHP program.20

Increasing Housing Resources

One additional tool available to FEMA is a pilot program (Stafford Act, Section 689i) that permits FEMA to negotiate with private owners of rental properties that are not currently ready for use. FEMA can then undertake repairs to the units in exchange for exclusive use of the units for FEMA temporary housing needs for that disaster. A 2009 FEMA report to Congress reviewed two attempts to implement the pilot. The pilot projects in Iowa and Texas offered the prospects of increased housing at a cost that is significantly less than direct housing assistance. As the FEMA report noted:

The approved estimate for repairing the seven units in the Cedar Valley apartment complex in Iowa was $44,709.83. The property owner provided FEMA with a breakdown of the monthly operating cost (i.e., labor, insurance, ongoing maintenance) for each unit. FEMA agreed to provide the property owner $328 per unit, per month, for the length of the lease (14 months). The total operating cost for this project was $32,144, bringing FEMA's total program contribution to $76,854. The cost to install and maintain seven manufactured homes for the same period of time would have cost FEMA $439,376. Thus, the savings compared to manufactured housing was estimated to be $362,522.

The approved estimate for repairing the 32 units in Carelton Courtyard Apartments in Texas was $494,820. The property owner provided FEMA with a breakdown of the monthly operating cost for each unit. FEMA agreed to provide the property owner $419 per unit, per month, for the length of the lease (30 months). The total operating costs for this project is $402,538, bringing FEMA's total program contribution to $897,358. The cost to install and maintain 32 manufactured homes for the same period of time would have cost FEMA $2,650,624. Thus, the estimated savings compared to manufactured housing was $1,753,266.21

While the approach described above may not always be possible, depending on the location of the disaster event, it arguably presents another opportunity to create temporary housing resources in the affected area. The Sandy Recovery Improvement Act in 2013 (SRIA, P.L. 113-2) codified this approach into law and provides FEMA with an option to create additional available housing units in the disaster area.22 This approach is also a potential help to the local community as it funds local repair work and leaves the community with more rental stock.

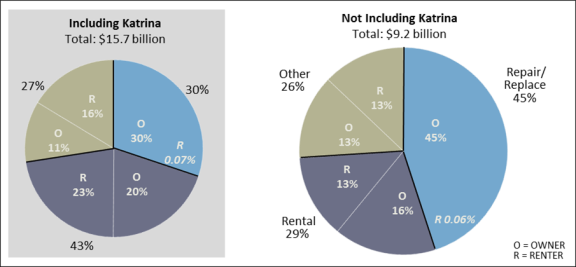

Housing Assistance Provided by Category

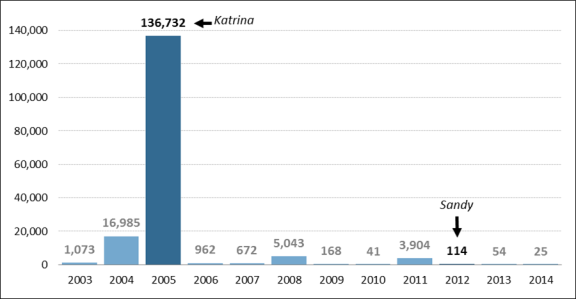

As noted earlier, the primary types of assistance provided under IHP are repairs, rental assistance and Other Needs Assistance (ONA). With the exception of Hurricane Katrina (which is an outlier), for most disasters, the majority of assistance is provided through grants for home repairs to make a home habitable.23 That is followed by rental assistance costs and ONA payments. The use of manufactured housing is not common and is a last resort when the other housing options are not available.24

The Figure 4 pie chart on the right (not including Katrina) illustrates that the plurality of assistance goes to owner-occupied housing. Within that category the great majority of funds (74%) are expended for home repairs, rental assistance, and Other Needs Assistance (ONA). However, the graphic including Katrina shows a significantly smaller amount spent on repairs and a larger amount devoted to rental assistance for both renters and homeowners, reflecting the degree of damage from that event and the diaspora of survivors in rental properties across the nation.

|

|

Source: Based on FEMA 2014 DATA. Notes: Graphics created by CRS. |

Hurricane Katrina damaged or destroyed a significant amount of housing stock along the Gulf Coast, including rental properties. This presented limited alternatives for temporary housing for disaster survivors. Many disaster survivors left the area to reach available housing because open rental units were often outside the impacted area. This led to significant amounts of rental assistance payments. In the case of Hurricane Sandy, and in fact for most disasters, the favored option for homeowners is to repair their homes and remain in them.

FEMA Direct Assistance: Manufactured Housing Units

Under the Stafford Act, direct assistance is defined as "the provision of temporary housing units, acquired by purchase or lease, directly to individuals and households."25 In an effort to provide a housing option for people who wished to stay in their communities following Katrina, FEMA established large mobile home parks. Given the large number of homes that sustained major damage, FEMA had to rapidly assemble a large mobile home inventory to address the numbers of families affected. The use of mobile homes during 2005 was the largest mobile home and trailer operation FEMA had ever attempted. In contrast, given the substantial rental market on the eastern seaboard, as well as fewer homes totally destroyed or with major damage, the used of mobile homes following Hurricane Sandy in 2012 was minimal.

|

|

Source: Based on FEMA 2014 DATA. Notes: Created by CRS. |

The Katrina recovery required a large number of hastily purchased mobile homes, which led to the problem of unsafe units being employed for temporary housing needs. This principally involved high levels of formaldehyde in some of the FEMA units.26 In subsequent years, FEMA established its own standards regarding air levels for formaldehyde in units. FEMA decided in 2007 to provide for temporary housing

manufactured homes built under HUD regulations in HUD regulated factories that are designed and built as long-term housing. HUD Code provides known national construction standards for transportable housing, a knowledgeable private sector infrastructure, and a well understood approach toward providing safe, secure, and habitable housing. In addition FEMA, in conjunction with the United States Fire Administration, has reviewed the benefits of including residential fire sprinkler systems as part of FEMA's basic manufactured home requirements and has determined that adding residential fire sprinkler systems is in the best interest of disaster survivor safety. FEMA includes residential fire sprinkler systems in all new manufactured homes. This will increase occupant safety as many manufactured homes installed by FEMA are located in rural areas that do not have fire departments able to reach homes as quickly as many urban fire departments.27

An additional problem at the time of Katrina was limited assistance or services being provided to large mobile home parks, whether they were existing parks that FEMA had augmented or large parks FEMA had developed. During the Katrina recovery period, FEMA support to group sites consisted mainly of public safety related requirements. In the years since, FEMA's interpretation of such support has expanded. In a memorandum describing "wrap around services" FEMA leadership defined that term as including

basic social services, access to transportation, police/fire protection, emergency health care services, communications, utilities, grocery stores, child care and educational institutions. The availability of common areas such as playgrounds, recreational fields, and designated pet areas may also be considered when establishing a temporary housing group site.28

Potential Issues for Congress

Equity in Disaster Housing Assistance

While FEMA assistance through the IHP program is available for presidentially declared disasters (and SBA disaster loan assistance may be available even for events that are not declared disasters by the President), a select number of disaster events receive an expanded form of federal assistance to meet housing needs. This can create differing tiers of disaster housing assistance for declared disasters depending on what actions Congress takes. Similarly, there are variations of housing assistance in which FEMA uses essential assistance authorities to maintain habitability (such as the STEP program discussed later in this section) which may not lend themselves to each disaster situation.

The following discussion provides some context to understand how different programs that are not a part of IHP can complement one another, and IHP, but also can cause some confusion for the applicants as well. All of these programs may be placed under the rubric of disaster housing, but absent careful coordination can be a cause for misunderstanding and duplication of administrative effort and, possibly, benefits.

CDBG-DR Availability

In some instances that are perceived as catastrophic events, Congress provides additional resources to states and local governments through the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. This is usually identified as CDBG-DR indicating its use in disasters. This approach to augment state resources has been used occasionally, but is not a part of every disaster declaration. It can be applied widely by "allowing states and communities to reprogram their annual CDBG funds to respond to disasters, however, Congress also has provided supplemental assistance to areas affected by natural and man-made catastrophes of a significant magnitude."29

In light of the great flexibility afforded state and local government recipients of the CDBG program and its many uses, the program has been called upon to address unexpected situations. Even so, it is not always an option for a state to reprogram at the time of a disaster. That is why state and local officials have contended that the additional CDBG funds provided through disaster supplemental appropriations (CDBG-DR) are so vital to the affected states. In these instances, Congress has been cognizant of potential needs beyond the recent, large scale disaster events and has sought a wide distribution for the CDBG funds dedicated to disaster relief activities. For example, following Hurricane Sandy, the supplemental appropriations legislation covered states affected by Hurricane Sandy but also reached beyond those affected states at that time as well. The language provided CDBG resources

for necessary expenses related to disaster relief, long-term recovery, restoration of infrastructure and housing, and economic revitalization in the most impacted and distressed areas resulting from a major disaster declared pursuant to the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5121 et seq.) due to Hurricane Sandy and other eligible events in calendar years 2011, 2012, and 2013, for activities authorized under title I of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. 5301 et seq.)30

Funds provided by the Hurricane Sandy supplemental appropriations are still available in accounts in 17 states and 17 local areas.31 The funds, as noted in the legislation above, can be used for a number of different purposes that contribute to the recovery of the state and the disaster-impacted community. While the funds are distributed more widely, there are still problems with the timing of such funding since some of these funds may become available long after many families have had to reach decisions on their future plans following the disaster event. Those decisions may include the acceptance of FEMA housing assistance as well as SBA disaster loans. Those sources of help generally precede the availability of CDBG-DR.

CDBG funds have frequently been used to expand mitigation projects and, as in the Sandy recovery, have been used to provide additional assistance to low-income residents for unmet housing needs. However, this form of assistance (CDBG-DR) is not available for every declared disaster and there may be some smaller disasters that could benefit from this form of supplemental federal help, rather than only having IHP and SBA assistance available.

It is worth noting that the Administration's budget request for FY2017 includes a proposal that may begin to address this issue. Though not committing additional funds for disaster work in the annual budget, it does propose a consolidation of administrative funds for HUD's Office of Community Planning and Development (CPD) from previous supplemental awards to bring some consistency to the program. The budget language noted that

as existing CPD internal management structures and protocols are designed, staffed, and funded to address needs associated with annually funded programs. These internal structures have little capacity to expand for the unpredictable scope of a CDBG-DR supplemental appropriation that may be a multiple of the annual CPD-wide budget. CPD proposes to consolidate remaining balances from these administrative allowances into a single account that can be used to support all CDBG-DR appropriations. This approach will enhance the usefulness of remaining administrative funds, and will ensure that CPD has the ability to hire term staff, perform on-site monitoring, and provide training focused exclusively on the CDBG-DR portfolio. Moreover, the administrative funds provided under P.L. 113-2 will expire on September 30, 2017, but significant program management requirements will continue well past that date; extending the period of availability of the consolidated funds will allow HUD to address this major concern.32

This type of improved structure could contribute to a more reliable approach by HUD to not only the management of supplemental funds but also for a more effective reprogramming of current CDBG funds that could assist states to respond to disasters not included in a supplemental appropriations legislative package and provide a more equitable approach for all disaster declarations.

This discussion also raises the question as to whether Congress would consider setting aside a pool of CDBG funds that could be triggered with the issuance of a presidential major disaster declaration. Or perhaps consider making such funds available only for major disaster declarations providing assistance to families and individuals. This would not preclude the CDBG-DR awards made in supplemental legislation, but it could also provide a consistently available amount of CDBG-DR dollars for all declared major disasters to enhance housing options, if needed.

Group Flood Insurance Linkages

The Group Flood Insurance policies are a three-year investment that may or may not be extended depending on the households' ability or willingness to do so. These investments might increase in worth with linkages to other FEMA programs such as mitigation grants (in helping to identify vulnerable areas) or HUD's CDBG program that could help to subsidize the polices for low income households. Some social service groups have suggested that the policies be extended in some form. For example, in a 2016 letter from Catholic Charities USA to the House Appropriations DHS Subcommittee stated: "We urge you to direct FEMA to develop mechanisms for 3rd party group policies to be maintained for persons in disasters who cannot afford to purchase and maintain flood insurance." While expenses of maintaining polices may be prohibitive, exploring approaches for such an extension is arguably a consistent part of the message; that insurance in place is the strongest preparation for providing a family an opportunity to recover from disaster damage.

Maximum Amount of Assistance

The maximum amount of assistance for individuals was established in the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 at $25,000.33 Over the last fifteen years that amount, in accordance with the law's adjustment limit, has grown by $8,000 to the current amount of $33,000.34 Congress may decide to consider whether the maximum amount is an adequate amount for providing supplemental help to a household after a disaster incident. The amount does appear to provide the necessary amount to provide the maximum amount of housing rental assistance under the law: 18 months. In addition, any remaining amounts could then be devoted to Other Needs Assistance. Also, it should be noted that FEMA does not deduct the cost of a manufactured housing unit against the IHP limit since the unit may revert back to FEMA. But it might also be argued that an increased amount would be an added impetus to the recovery of the local economy. Also a larger IHP award could be especially helpful to carry out the clause of Section 408 that may provide "financial assistance for the replacement of owner-occupied private residences damaged by a major disaster."35 Similarly, a larger award could also help a household to comply with that section's flood insurance requirement. However striking a balance is important since a more generous amount might discourage the purchase of insurance.

The STEP Program Availability

Similar to the support offered by CDBG another program not always available in every disaster is the Sheltering and Temporary Essential Power (STEP) program.36 Under this program FEMA works with state and local governments to reach out to homeowners to perform certain necessary and essential measures to help "restore power, heat and hot water to primary residences that could regain power through necessary and essential repairs. STEP can help residents safely shelter-in-place in their homes pending more permanent repairs."37 This was a pilot program created by FEMA to meet this specific need but is similar to previous FEMA efforts to implement emergency repairs, such as the "Operation Blue Roof" programs it employed in the Caribbean following devastating hurricane damage in the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.38 Similar operations were also carried out in Texas following a string of tornadoes in 2007.

One distinction is that the STEP program home repairs are not accomplished under the authority of the IHP program. The STEP program is funded under Section 403 of the Stafford Act, which covers Essential Assistance.39 This represents significant home repair spending that is not available in each declared disaster. After Sandy, for example, FEMA had reported that in New York City, more than 17 thousand units had received these immediate repairs at a cost surpassing $466 million.40 In many instances, the STEP program may have been all the assistance the household required, but the household would have remained eligible for additional assistance under IHP if needed and eligible.

The STEP program, or something similar to it, has been employed by FEMA to meet urgent needs for sheltering. It may be of interest to Congress to learn how the STEP program has worked and whether it could be scaled for use on disasters of all sizes. FEMA's IG reported on the program during Sandy and had generally favorable conclusions regarding the pilot program.

We determined that FEMA's actions in promulgating this pilot program are consistent with the authorities granted by the Stafford Act. Given the number of individuals affected by Hurricane Sandy, FEMA needs to maintain strong internal controls. We commend FEMA for its rapid response in designing this urgently needed program less than a month after Hurricane Sandy devastated communities on the Atlantic coast. If successful, the program can provide the assistance necessary to save lives, protect public health and safety, and protect property. Nevertheless, FEMA needs to be mindful of the vulnerabilities associated with implementing pilot programs and to institute adequate internal controls to protect against those vulnerabilities.41

Condos and Co-ops Eligibility

The STEP program can also provide assistance to the owners of large buildings. This partially addressed some other issues raised following the impact of Hurricane Sandy with regard to FEMA's treatment of condos and co-ops. While some assistance could be provided to condo or co-op residents under the IHP program, just as it is for any homeowner who suffered damage, there were other complications. One of the main areas of contention has been how to address common areas in these buildings. The IHP program does not have any authority to address common areas since the program only addresses where someone lives. However, the 403 Essential Assistance program could potentially address such areas. But FEMA's policy guidance directs that such common areas must have the majority of their use directed toward common purposes. FEMA's Policy Guidance notes that a facility may be eligible if

Facility use is not limited to any of the following:

A certain number of individuals;

A defined group of individuals who have a financial interest in the facility, such as a condominium association;

Certain classes of individuals; or

An unreasonably restrictive geographical area, such as a neighborhood within a community;42

Since the guidance explicitly sees a condominium association as ineligible if it limits use of its facility to its members, there has been an extended dialogue between FEMA and the representatives of condo and co-op associations. There is proposed legislation that would direct FEMA to continue to engage this issue and work to find new proposals to address the issue.43

The Sequencing of Housing Assistance

As previously noted, FEMA assistance can be available swiftly. Once the program is activated, applications are reviewed and services can begin, such as arranging inspections and, in some instances, performing disaster repairs under something like a STEP program as noted earlier regarding Operation Blue Roof. This might then be followed by an SBA disaster declaration which makes home loans available for much larger amounts than the IHP caps. Frequently, SBA declarations will closely follow presidential major disaster declarations. In addition, determining eligibility for SBA loans can be a part of FEMA's application process.

While those initial steps happen quickly, the availability of CDBG-DR funds depend on congressional action to augment available funding, although CDBG grantees (states and some local governments) are free to reprogram their regular CDBG allocation to address an imminent threat to the health and safety of their residents. But the arrival of supplemental CDBG funds may be weeks or months after homeowners have received some IHP assistance and then arrived at some decisions regarding pursuing an SBA loan. This can result in a situation where a household may accept a loan only to learn later that CDBG grants at favorable terms have become available for similar purposes through the state. This can open up a contentious process in which homeowners may request a cancellation of their loan in exchange for receiving a state grant.44 But while these conflicts can occur, it should also be noted that the first priority of the CDBG grants are low-income families and individuals that may not qualify for SBA loans. However, the CDBG low income requirement can be and often has been waived or modified to meet the needs of a larger middle income population in large disaster events.

The State Role in Disaster Housing

While CDBG funds are provided through the states, the actual role that states play in disaster housing, as administered by FEMA in the disaster recovery process, is quite limited. Not only do states not contribute to the costs of disaster housing through any cost-shares with regard to rental or repair expenditures, they also do not have any obligation to assist in the physical establishment of temporary manufactured housing communities.45 This stands in contrast to the close partnership that exists between FEMA and the states for both the PA and Hazard Mitigation Grant Programs (HMGP) where state staff work with applicants (e.g., local government and non-governmental organizations) and FEMA in the administration of the program.

States do have a 25% cost-share to meet for grants to families and individuals from the ONA program and, based on that contribution, the states consult with their respective FEMA regions on the type and extent of the ONA grants that will be available within their states following a declaration. Congress may choose to consider whether a greater involvement by states might improve the quality of disaster recovery for families and individuals and help to foster the types of programs that might be available for nonfederal disaster events.

Recent FEMA initiatives to update IA factors considered when reviewing a governor's request for a major disaster declaration encourage more state involvement. Similarly, a recent FEMA proposal to create a PA Deductible to assess when a state might qualify for Public Assistance also encourages the establishment of state programs and a greater state commitment to the recovery process.

One example of this approach is the suggestion of a new factor titled, "State Fiscal Capacity and Resource Availability." As the FEMA narrative in the Federal Register Notice observes:

When the community is engaged in emergency management, it becomes empowered to identify its needs and the existing resources that may be used to address them. Collectively, we can determine the best ways to organize and strengthen community assets, capacities, and interests. This allows us, as a nation, to expand our reach and deliver services more efficiently and cost effectively to build, sustain, and improve our capability to prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate all hazards.46

Similarly, in the Federal Register Notice proposing consideration of a Disaster Deductible when considering requests for a PA declaration, FEMA's Notice suggests:

It could incentivize proactive fiscal planning by Recipients for disasters, encouraging them to set aside funding specifically reserved for disaster response and recovery. The availability of credits toward the deductible could incentivize increased planning and adoption of specific mitigation activities which will result in risk-informed mitigation strategies on a broad scale. States may be encouraged to develop and fund special programs such as emergency management programs and individual assistance programs, as such plans may be credited toward satisfaction of the deductible.47

In concert with these suggestions, Congress may consider whether greater involvement by the states in FEMA's disaster housing program might improve the overall program and highlight state responsibilities. Currently, FEMA may consult with the state and local governments when seeking available locations for manufactured housing. But other assistance, such as home repairs, are 100% federally funded. Arguably with some state "skin in the game" there would be a greater awareness by the state of the extent and types of assistance being provided. It would also increase the state's interest in accountability and assuring the quality and timeliness of the repairs as well as the importance of coordinating the applicable programs.

Summary Considerations

In evaluating the history of this topic it can be argued that disaster housing has been driven by the assumption, by both FEMA and its state partners, of a temporary, short-term mission. This assumption was based upon the shared experiences of most non-catastrophic disaster events. These "garden variety disasters" required minimal help to house those made homeless by the disaster event. Additionally, scant attention arguably has been paid to longer-term housing missions resulting in a program some have described as having limited resources, which may suffer from an approach that could arguably be considered insufficiently comprehensive.

However, in recent years there have been a number of steps taken by Congress, such as authorizing Case Management Services and increasing FEMA's ability to create housing resources in the disaster area, as well as initiatives by FEMA that include improved manufactured housing and wrap-around services to support such housing. These incremental pieces have contributed to a more comprehensive temporary housing program with flexible options to offer disaster survivors.

Also, following large, catastrophic events, the combination of IHP with HUD's CDBG-DR program and SBA disaster loans can present a range of types of assistance that can be fashioned to meet the needs of individual disaster survivors. However, as noted earlier, the existence of all such help in each declared disaster is not guaranteed.

But the remaining challenges can be addressed through increased communication by FEMA and its state partners. The most significant test is to manage expectations regarding the assistance that is available following a disaster. That challenge is coupled with the potential need to create a culture of preparedness that would underline to homeowners that IHP assistance is limited and does not supplant the greater benefits of insurance coverage.

It is not a simple message, since the goal is to offer assurance to the public that, while supplemental help is available, it must be understood that insurance and personal mitigation measures should also be considered prior to a disaster event. The IHP program is there for those without the resources to pursue insurance coverage or other preparedness tools. But for those families and individuals able to take a role in their own recovery, an appreciation for the importance of insurance and mitigation would reduce the need of the IHP program, and result in safer and more resilient communities when disaster strikes.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to CRS Visual Information Specialist Amber Wilhelm and former CRS Research Associate [author name scrubbed] for their contributions to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

P.L. 82-107, Missouri-Kansas-Oklahoma-Flood Housing Relief, August 3, 1951. For additional information on the Declaration process see CRS Report R43784, FEMA's Disaster Declaration Process: A Primer, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), "A History of Federal Disaster Relief Legislation, 1950-1974," FEMA-45, September, 1983. |

| 3. |

The SBA program was established under P.L. 85-356, Section 7(b), 72 STAT.387, as amended. The DUA program was established under P.L. 91-606, Section 240, 84 STAT. 1755. For more information on the SBA loan program see CRS Report R41309, The SBA Disaster Loan Program: Overview and Possible Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. For information on the DUA program see CRS Report RS22022, Disaster Unemployment Assistance (DUA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 4. |

This amount is adjusted annually in accordance with the Consumer Price Index. The latest adjustment was posted in a Federal Register Notice—FEMA, Federal Register 80, October 15, 2015, p. 62086. |

| 5. |

44 C.F.R. 206.101 (e)(2). |

| 6. |

42 U.S.C. 5174(b)(2)(B). |

| 7. |

For a detailed listing of ONA assistance see FEMA Disaster Assistance Fact Sheet, March, 2015, available at http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1434645692423-a8341b2317b9bcd4eca23aac8e8e1ea/IHP_FactSheet_final508.pdf. The Post-Hurricane Sandy legislation (P.L. 113-2) expanded ONA eligibility to include child care expenses. |

| 8. |

44 C.F.R. 61.17. |

| 9. |

42 U.S.C. 5189d, this authority was established in Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act (PKEMRA), P.L. 109-295, October 4, 2006, 120 STAT. 1453. |

| 10. |

For the purpose of this report, hereinafter, the term governor, in all cases, includes tribal leaders that serve the same role for disaster requests on tribal lands. |

| 11. |

While it is preferred that a PDA precede any declaration, in instances of catastrophic events, often declarations and designations of assistance are made before PDAs are completed. Then PDAs are subsequently conducted to target assistance. |

| 12. |

DHS/FEMA, Operations Manual: A Guide to Assessing Damage Assessment Damage and Impact, March 31, 2016, p. 50. |

| 13. |

For more information on FEMA's PA program see CRS Report R43990, FEMA's Public Assistance Grant Program: Background and Considerations for Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 14. |

Online registration is available at DisasterAssistance.gov. |

| 15. |

FEMA Office of Legislative Affairs, email response to CRS IA questions, September 24, 2014. |

| 16. |

Ibid. |

| 17. |

Due to the differences in the programs, and the information they are collecting and the size of the possible grants vs. loans, FEMA and SBA conduct their inspections separately. This has been a source of some irritation among disaster survivors, but the inspections remain separate. For additional information on the SBA Disaster Loan Program see CRS Report R41309, The SBA Disaster Loan Program: Overview and Possible Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 18. |

CRS analysis of FEMA IHP data, found at http://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/30714. Data used for this analysis was published October 10, 2014. Henceforth to be termed FEMA 2014 DATA. |

| 19. |

42 U.S.C. 5174(b) 92) (A). |

| 20. |

44 C.F.R. 206.101 (m). |

| 21. |

DHS/FEMA, Individuals and Households Pilot Program, Fiscal Year 2009 Report to Congress, May 19, 2009, pp.10 and 11. |

| 22. |

P.L. 113-2, Section 1103, January 29, 2013, 127 Stat. 42. |

| 23. |

For Katrina there was a much larger amount expended on rental assistance both to survivors spread out in 38 states, and also through the Disaster Housing Assistance Program (DHAP), a FEMA partnership with HUD that provided rental assistance for several years after the event. This was partly due also to the extensive damage to homes that required larger grants for repair than are available under IHP. Some of this need was addressed through Louisiana's The Road Home program that was primarily financed through funding from HUD's CDBG program. |

| 24. |

However, a recent example of the use of direct assistance is the May 2015 declaration for the Oglala Sioux Tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Given the remote location, the use of manufactured housing has provided the long-term housing help the area required. By March 2016 the 100th manufactured housing unit was installed to meet long-term housing needs created by the disaster event. |

| 25. |

42 U.S.C. 5174(c)(B). |

| 26. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, "Hurricane Katrina Response—Committee Probes FEMA's Response to Report of Toxic Trailers," Supplemental Memo and Exhibits, July 19, 2007, at |

| 27. |

FEMA Office of Legislative Affairs, Memo to CRS, March 7, 2016. |

| 28. |

FEMA Memo, Michael M. Grimm, Director, Individual Assistance Division, "Wrap-Around Services for Temporary Housing Group Sites," November 21, 2012. |

| 29. |

For additional, detailed information see CRS Report R43520, Community Development Block Grants and Related Programs: A Primer, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 30. |

P.L. 113-2, January 29, 2013, 126 Stat. 36. For additional information, see CRS Report R42892, Summary Report: Congressional Action on the FY2013 Disaster Supplemental, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 31. |

Department of Housing and Urban Development, CDBG-DR Active Disaster Grants and Grantee Contact Information, https://www.hudexchange.info.programs/cdbg-dr-grantee-contact-information. |

| 32. |

HUD FY2017 Budget, Community Planning and Development, 2017 Summary Statement and Initiatives, "5. Proposal in the Budget—Consolidation of Disaster Administrative Appropriations," p. 15-13, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=15-Community_Dev.Fund.pdf. CPD refers to the Office of Community Planning and Development. |

| 33. |

42 U.S.C. 5174(h). |

| 34. |

This adjustment is made per the law's direction to adjust it annually "to reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the Department of Labor." |

| 35. |

42 U.S.C. 5174(c)(3). |

| 36. |

Currently for the Louisiana disaster, Louisiana-DR-4277, a similar program called "Shelter at Home" is being used to address emergency housing needs. The amount of assistance is capped at $15,000 per home. See FEMA Daily Fact Sheet, 8-30-16-DR-4277. |

| 37. |

DHS/FEMA, "FEMA STEP Program in Action," March 19, 2014, http://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/images/67242. |

| 38. |

DHS/FEMA, "Operation Blue Roof," Release Number 1539-164, October 2, 2004, http://www.fema.gov/news-release/2004/10/02/operation-blue-roof. |

| 39. |

42 U.S.C. 5170b. |

| 40. |

Memo from FEMA Office of Legislative Affairs, to CRS, August 5, 2014. |

| 41. |

DHS/FEMA Office of Inspector General, OIG-13-15, December 2012. |

| 42. |

DHS/FEMA Public Assistance and Policy Guide, FP 104-009-2, January 2016, p. 11. |

| 43. |

H.R. 1471, 114th Congress, 2nd Session, March 1, 2016, Title III, Section 308. |

| 44. |

For a detailed discussion of this issue, see CRS Report R44553, SBA and CDBG-DR Duplication of Benefits in the Administration of Disaster Assistance: Background, Policy Issues, and Options for Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 45. |

Earlier iterations of FEMA regulations insisted on states being responsible for site locations and the establishment of utilities on those sites. But those requirements were dropped as FEMA assumed a greater role in the housing mission to ensure consistent applications of the program. |

| 46. | |

| 47. |