SBA and CDBG-DR Duplication of Benefits in the Administration of Disaster Assistance: Background, Policy Issues, and Options for Congress

Numerous nonprofit, private, and governmental organizations provide a wide range of assistance after a disaster strikes. Section 312 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288) requires federal agencies providing disaster assistance to ensure that individuals and businesses do not receive disaster assistance for losses for which they have already been compensated. Duplication of benefits occurs when compensation from multiple sources exceeds the need for a particular recovery purpose. Recipients are liable to the United States when the assistance duplicates benefits provided for the same purpose.

The combination of any type of disaster assistance can cause duplication. This report focuses on duplication of benefits between the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) grant program and the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program. Key areas of congressional concern over the past decade with respect to the two programs include:

despite quality checks and audits, agencies continue to provide duplicative disaster assistance to individuals and businesses;

duplication assessment and collection process costs often exceed the money recouped;

the execution of the required delivery sequence can be complex and confusing because a multitude of assistance sources can be difficult to coordinate and monitor;

the execution can also be complex and confusing because CDBG-DR is not listed in the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s regulatory sequence procedures;

benefits stem from multiple authorities subject to different interpretations;

federal guidelines regarding the process that states may follow in an effort to minimize potential duplication of benefits in the awarding of CDBG-DR are advisory and are not mandated requirements. To some this gives states too much flexibility to determine who is eligible for CDBG-DR;

disaster victims are sometimes unaware that they received an improper payment and, in some cases, receive collection notices well after they had spent the money on recovery needs.

Equity concerns also stem from the duplication of benefits. These include:

that CDBG-DR is not provided for all disasters. Consequently, some major disasters may benefit from CDBG-DR while others may not—even if they have similar losses;

in most cases, SBA disaster loans can be provided more quickly than financial assistance from a CDBG-DR grant. As a consequence, it is possible for some homeowners to receive an SBA disaster loan and later be deemed ineligible when applying for financial assistance from a CDBG-DR grant due to duplication of benefits requirements. To some, it may appear that homeowners who took initiative to repair and rebuild were unfairly penalized.

This report provides a brief description of the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR. It lists relevant authorities, and highlights policy considerations. The report also explores a number of policy options Congress might consider when addressing duplication of benefits issues related to SBA disaster loans and CDBG-DR. These policy options include

requiring FEMA to clarify the regulatory delivery sequence to help eliminate potential confusion;

prohibiting SBA disaster loan recipients from receiving CDBG-DR assistance or developing other policy options so that CDBG-DR assistance is awarded uniformly;

establishing CDBG-DR assistance as a permanent disaster assistance program;

replacing suggested guidelines for the disbursal of CDBG-DR with requirements;

investigating the use of a centralized database to identify duplication of benefits more effectively.

This report will be updated as events warrant.

SBA and CDBG-DR Duplication of Benefits in the Administration of Disaster Assistance: Background, Policy Issues, and Options for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Brief Program Overview

- SBA Disaster Loan Program

- Community Development Block Grants-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR)

- Statutory Authorities and Regulations

- Policy Issues

- Duplication of Benefits Issues and Conflicts

- Delivery Sequence

- Delivery Sequence Issues

- Duplication of Benefits and Delivery Sequence Determinations

- Selected Examples of SBA Disaster Loan and CDBG-DR Duplication Interpretations

- Policy Options

- Revise FEMA Regulations

- Prohibit SBA Disaster Loan Recipients from Receiving CDBG-DR

- Annual Appropriations for CDBG-DR

- State Disbursement of CDBG-DR

- Assistance Database

Figures

Summary

Numerous nonprofit, private, and governmental organizations provide a wide range of assistance after a disaster strikes. Section 312 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (P.L. 93-288) requires federal agencies providing disaster assistance to ensure that individuals and businesses do not receive disaster assistance for losses for which they have already been compensated. Duplication of benefits occurs when compensation from multiple sources exceeds the need for a particular recovery purpose. Recipients are liable to the United States when the assistance duplicates benefits provided for the same purpose.

The combination of any type of disaster assistance can cause duplication. This report focuses on duplication of benefits between the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) grant program and the Small Business Administration (SBA) Disaster Loan Program. Key areas of congressional concern over the past decade with respect to the two programs include:

- despite quality checks and audits, agencies continue to provide duplicative disaster assistance to individuals and businesses;

- duplication assessment and collection process costs often exceed the money recouped;

- the execution of the required delivery sequence can be complex and confusing because a multitude of assistance sources can be difficult to coordinate and monitor;

- the execution can also be complex and confusing because CDBG-DR is not listed in the Federal Emergency Management Agency's regulatory sequence procedures;

- benefits stem from multiple authorities subject to different interpretations;

- federal guidelines regarding the process that states may follow in an effort to minimize potential duplication of benefits in the awarding of CDBG-DR are advisory and are not mandated requirements. To some this gives states too much flexibility to determine who is eligible for CDBG-DR;

- disaster victims are sometimes unaware that they received an improper payment and, in some cases, receive collection notices well after they had spent the money on recovery needs.

Equity concerns also stem from the duplication of benefits. These include:

- that CDBG-DR is not provided for all disasters. Consequently, some major disasters may benefit from CDBG-DR while others may not—even if they have similar losses;

- in most cases, SBA disaster loans can be provided more quickly than financial assistance from a CDBG-DR grant. As a consequence, it is possible for some homeowners to receive an SBA disaster loan and later be deemed ineligible when applying for financial assistance from a CDBG-DR grant due to duplication of benefits requirements. To some, it may appear that homeowners who took initiative to repair and rebuild were unfairly penalized.

This report provides a brief description of the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR. It lists relevant authorities, and highlights policy considerations. The report also explores a number of policy options Congress might consider when addressing duplication of benefits issues related to SBA disaster loans and CDBG-DR. These policy options include

- requiring FEMA to clarify the regulatory delivery sequence to help eliminate potential confusion;

- prohibiting SBA disaster loan recipients from receiving CDBG-DR assistance or developing other policy options so that CDBG-DR assistance is awarded uniformly;

- establishing CDBG-DR assistance as a permanent disaster assistance program;

- replacing suggested guidelines for the disbursal of CDBG-DR with requirements;

- investigating the use of a centralized database to identify duplication of benefits more effectively.

This report will be updated as events warrant.

Introduction

Following a disaster, particularly one that has been designated by the President as a major disaster or emergency, homeowners and businesses may have access to a number of resources to assist in the response, recovery, and rebuilding process. The range of resources available to individual businesses and households includes insurance payouts, state and local government assistance, charitable donations from private institutions and individuals, and federal assistance.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is the primary entity charged with managing disaster response activities.1 The scope of FEMA assistance is based on the extent of damage incurred. FEMA and its programs, however, are not the sole source of federal assistance that may be available following a presidential disaster declaration.2 Other forms of federal disaster assistance include the Small Business Administration's (SBA's) Disaster Loan Program (SBA Disaster Loan Program) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD's) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program.3 While the SBA Disaster Loan Program is automatically triggered by a presidential disaster declaration, CDBG-DR is not. Instead, Congress has occasionally addressed unmet disaster needs by providing supplemental disaster-related appropriations for the CDBG-DR program. Consequently, CDBG-DR is not provided for all major disasters, but only at the discretion of Congress.

The array of disaster recovery assistance available to businesses and individuals can sometimes result in the awarding of funds in excess of the replacement cost of losses suffered. In instances where the President has issued a major disaster declaration, Section 312 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (hereinafter the Stafford Act, P.L. 93-288) requires federal agencies providing disaster assistance to ensure that individuals and businesses do not receive disaster assistance for losses for which they have already been compensated or may expect to be compensated. Duplication of benefits occurs when compensation from multiple sources exceeds the need for a particular recovery purpose. In such instances, the recipient receiving federal assistance is liable to the United States when the assistance duplicates benefits provided for the same purpose by any other source.

This report addresses issues surrounding duplication of benefits, focusing on SBA disaster loans to individuals and businesses and CDBG-DR grants to state and local governments. CDBG-DR grant recipients provide grants and loans to individuals and businesses. The purpose of this report is to

- provide a brief review of the SBA Disaster Loan and CDBG-DR programs;

- identify federal statutory authorities, regulations, and policy guidance documents governing the duplication of benefits in the provision of federal disaster assistance to businesses and individuals;

- identify issues and conflicts that may arise in interpreting and implementing the federal requirements governing duplication of benefits;

- highlight key policy considerations with respect to the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR duplication of benefits; and

- examine legislative policy options that may address issues related to the duplication of benefits in the provision of SBA Disaster Loan and CDBG-DR disaster recovery assistance.

Brief Program Overview

SBA Disaster Loan Program

The SBA Disaster Loan Program provides low-interest, direct loans to businesses, nonprofit organizations, homeowners, and renters to repair or replace property damaged or destroyed in a federally declared disaster. The program is also designed to help small agricultural cooperatives recover from economic injury resulting from a disaster. There are three categories of SBA disaster loans: Home and Personal Property Disaster Loans (up to $200,000 to homeowners for real estate and up to $40,000 for personal property), Business Physical Disaster Loans (up to $2 million), and Economic Injury Disaster Loans (up to $2 million).4

Community Development Block Grants-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR)

HUD's CDBG-DR program provides grants to states and localities to assist their recovery efforts following a presidentially declared disaster. Generally, grantees must use at least half of these funds for activities that principally benefit low- and moderate-income persons or areas. The program is designed to help communities and neighborhoods that otherwise might not recover due to limited resources.5 CDBG-DR is not available for all major disasters because it is generally subject to Congress passing CDBG supplemental appropriations.6

State and local governments may use CDBG-DR grant funds for recovery efforts involving housing, economic development, infrastructure, and prevention of further damage to affected areas. Examples of eligible uses include

- Buying damaged properties in a flood plain and relocating residents to safer areas;

- Providing relocation payments for people and businesses displaced by the disaster;

- Debris removal not covered by FEMA;

- Rehabilitation of homes and buildings damaged by the disaster;

- Buying, constructing, or rehabilitating public facilities such as streets, neighborhood centers, and water, sewer, and drainage systems;

- Homeownership activities such as down payment assistance, interest rate subsidies, and loan guarantees for disaster victims; and

- Assisting businesses retain or create jobs in disaster areas.7

CDBG-DR grants are intended to supplement rather than supplant SBA and FEMA assistance and are typically enacted by Congress following major disasters. Congress has authorized more than $45 billion for disaster recovery efforts through the CDBG-DR program since 2000.8 In general, Congress has used the statutory framework governing the regular CDBG program when appropriating CDBG-DR funds. In addition, the language of a particular supplemental appropriation may include a number of provisos, waivers, and alternative requirements dictating how and for what purposes funds are to be used, including language directing grantees to develop processes that will prevent waste, fraud, and abuse, including minimizing the duplication of benefits in the administration of CDBG-DR funds.

Statutory Authorities and Regulations

Because disaster assistance is provided through a variety of entities, policies and guidelines governing the duplication of benefits stem from multiple authorities. Some observers contend that the authorities appear incongruous and confusing. The following is a listing of relevant authorities and regulations pertaining to duplication of benefits with respect to the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR.

Stafford Act (42 U.S.C. §5155)

The Stafford Act is the primary statute governing the provision of federal disaster assistance, particularly assistance administered by FEMA. Section 312 of the Stafford Act requires that federal agencies providing financial assistance ensure that individuals, businesses, or other entities suffering losses as a result of a major disaster or emergency do not receive assistance for losses for which they have already been compensated.9 Section 312 also requires the President to establish procedures that ensure uniformity in preventing duplication of benefits. Under Section 312, any person, business, or other entity that has received or is entitled to receive federal disaster assistance is liable to the United States for the repayment of such assistance to the extent that such assistance duplicates benefits available for the same purpose from another source, including insurance and other federal programs.

FEMA Regulation

44 C.F.R. 206.191, which establishes the policies implementing Section 312 of the Stafford Act, states that it is FEMA policy to prevent the duplication of benefits between its own programs, other assistance programs, and insurance benefits. The regulation requires individuals to repay all duplicated assistance to the agency providing the assistance. Under 44 C.F.R. 206.191, a federal agency providing disaster assistance is responsible for preventing or rectifying duplication of benefits when they occur. 44 C.F.R. 206.191 also includes a "delivery sequence" hierarchy intended to prevent waste, fraud, and abuse of program assistance, including the duplication of benefits. The delivery sequence is discussed later in this report.

Small Business Act (15 U.S.C. §647)

Section 18(a) of the Small Business Act (P.L. 85-536, as amended) prohibits the SBA from providing benefits that duplicate the assistance provided by another department or agency of the federal government. Section 18(a) states that if loan applications are refused or denied by a department or agency due to administrative withholding or due to an administratively declared moratorium, then no duplication is deemed to have occurred.

SBA Regulation

13 C.F.R. 123.101(c) states that applicants for SBA Disaster Loan assistance are not eligible for a home disaster loan if their damaged property can be repaired or replaced with the proceeds of insurance, gifts, or other compensation. According to the regulation, these amounts must either be deducted from the amount of the claimed losses or, if received after SBA has disbursed the loan, must be paid to SBA as principal payments on the loan.

It should be noted that most SBA disaster loans (approximately 80%) are awarded to individuals and households rather than small businesses. The program generally offers low-interest disaster loans at a fixed rate with loan maturities of up to 30 years. Thus, SBA loans are a significant source of assistance to individuals.

Title I Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. §5321) and Supplemental Appropriation Acts

The authority to enlist the CDBG program in disaster recovery efforts is provided under the Stafford Act. Further, the law governing the general CDBG program, 42 U.S.C. 5321, authorizes HUD to suspend or waive all statutory requirements of the CDBG program in order "to address the damage in an area for which the President has declared a disaster under" the Stafford Act. Under this authority, CDBG grantees may receive waivers that allow them to utilize their regular CDBG formula grant funds for disaster recovery purposes.10 Further, in some years, Congress provided supplemental appropriations to the CDBG program in response to a disaster that affected communities outside of the regular CDBG formula grant process. These so-called CDBG Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) grants are governed both by the underlying CDBG statute, as well as the provisions of the law that appropriated them.11 As noted above, while the underlying authority exists allowing CDBG funds to be used for disaster relief, Congress must act to appropriate the funds used in response to the incident.

CDBG-DR Regulations and Guidance

On November 16, 2011, HUD published a Notice in the Federal Register clarifying the duplication of benefits requirements under the Stafford Act for CDBG-DR grantees. The Notice covers all active CDBG-DR grants dating back to 2001 as well as future CDBG-DR grants. It makes clear that the duplication of benefits requirement articulated in the Stafford Act applies to all federal agencies administering disaster recovery assistance, including HUD's CDBG program. The Notice provides guidance on, but does not designate nor mandate, adherence to a specific process or method by which grantees must evaluate whether a recipient of CDBG-DR funds has received a duplication of benefits. The Notice does provide a suggested framework for determining need and possible duplication of benefits. The basic six-step framework suggested by HUD is outlined below in Table 1.

|

1. |

Identify Applicant's Total Need Prior to Any Assistance |

|

2. |

Identify All Potentially Duplicative Assistance |

|

3. |

Deduct Assistance Determined to be Duplicative |

|

4. |

Maximum Eligible Award (Item 1 less Item 3) |

|

5. |

Program Cap (if applicable) |

|

6. |

Final Award (lesser of Items 4 and 5) |

Source: Department of Housing and Urban Development, "Clarification of Duplication of Benefits Requirements Under the Stafford Act for Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Disaster Recovery Grantees," 76 Federal Register 71060 -71066, November 16, 2011.

The Notice includes a prohibition against the use of CDBG-DR funds to pay down an SBA home or business loan. In addition, the Notice suggests that should the initial SBA disaster loan amount prove inadequate to meet the homeowner's or business's cost to complete repairs then SBA should reevaluate an applicant's eligibility to receive additional assistance. The Notice clearly states that CDBG-DR may be used only after SBA eligibility has been exhausted and is intended to supplement and not supplant SBA assistance.

Policy Issues

There are several key areas of congressional concern related to the duplication of CDBG-DR assistance and SBA disaster loans, including confusion about the orderly execution of the delivery sequence as dictated by FEMA, how the duplication of benefits policy and the delivery sequence are interpreted, and concerns expressed about fairness, fraud, and delays in rebuilding efforts.

Duplication of Benefits Issues and Conflicts

The availability and timing of disaster assistance from various sources can lead to a duplication of benefits. The duplication of benefits stemming from overlaps between SBA disaster loans and CDBG-DR, however, has been of particular congressional concern. A review of the issues surrounding the use of both SBA disaster loans and CDBG-DR assistance in addressing the needs of individuals and businesses engaged in disaster recovery efforts yields several observations:

- Despite quality checks and audits, agencies continue to provide duplicative disaster assistance to ineligible individuals and businesses. Though they are ineligible, these individuals and businesses typically applied for CDBG-DR assistance because they needed assistance to rebuild and recover from a disaster. In most cases, they used CDBG-DR funds to make needed repairs. These ineligible individuals and businesses later find that they must repay what they did not realize was an improper payment. To some observers, the recoupment of CDBG-DR funds in such cases creates an additional financial and emotional burden for disaster victims who were mistakenly provided an improper grant or loan resulting in a duplication of benefit.

- It has also been argued that the duplication assessment and collection process costs more to conduct than the money recouped.12

- Given the multitude of assistance sources, some observers argue that the execution of the delivery sequence, which dictates the order in which assistance is to be provided by different funding sources, can be complex, confusing, and difficult to coordinate and monitor, often complicated by issues of timing, competence in the conveyance of information, and concerns regarding fraud prevention.

- Some observers have argued that the potential for duplication of benefits is exacerbated by the presence of multiple authorities that are incongruous and subject to different interpretations.

- Federal guidelines regarding the process that states may follow in an effort to minimize potential duplication of benefits in the awarding of CDBG-DR are advisory and are not mandated requirements. To some this gives states too much flexibility to determine who is eligible for CDBG-DR.

In addition, the way in which the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR assistance has been administered is viewed by some as inequitable. The issue of inequitable treatment includes concerns that

- CDBG-DR is not provided for all disasters. Major disasters with similar losses to other major disasters may not benefit from CDBG-DR without affirmative action by Congress to appropriate funds; and

- in some cases, homeowners were denied CDBG-DR financial assistance because they obtained an SBA disaster loan.13 Whereas loans, such as SBA disaster loans, must be repaid, grants do not have to be. To some, it may have appeared that homeowners who took the initiative to repair or rebuild through SBA disaster loans were unfairly penalized.

Delivery Sequence

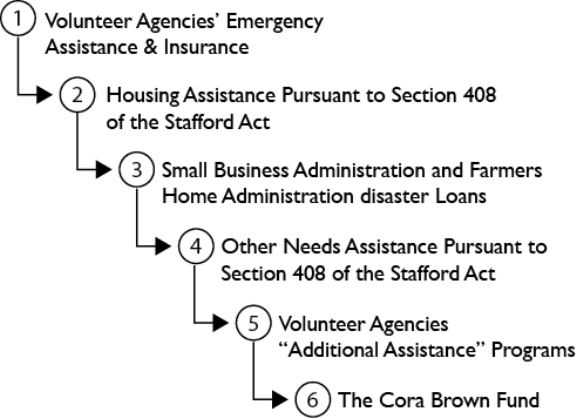

The uniformity requirement set forth in Section 312 of the Stafford Act is located in FEMA regulation 44 C.F.R. 206.191. As shown in Figure 1, 44 C.F.R. 206.191 provides procedural guidance to ensure uniformity in preventing duplication of benefits. 44 C.F.R. 206.191 establishes a delivery sequence of disaster assistance provided by federal agencies and organizations.

|

|

Source: 44 C.F.R. 206.191 Note: Housing assistance under Section 408 includes assistance to individuals and households who are displaced from their pre-disaster primary residences or whose pre-disaster primary residences are rendered uninhabitable, or with respect to individuals with disabilities, rendered inaccessible or uninhabitable as a result of a major disaster. Section 408 includes temporary housing as well as repairs. Other needs assistance under Section 408 includes financial assistance for medical, dental, and funeral expenses. Cora Brown of Kansas City, MO,died in 1977. She left a portion of her estate to the United States to be used as a special fund to relieve human suffering caused by natural disasters. For more information on the Cora Brown Fund see https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1434639028239-341e17807cb06b0bf000d21cc7552b2c/CoraBrown-FactSheet-final508.pdf. |

An organization's position within the sequence determines the order in which it should provide assistance and what other resources need to be considered before that assistance is provided. Further, each organization is responsible for delivering assistance without regard to duplication later in the sequence.

According to FEMA regulations, the agency or organization that is lower in the delivery sequence should not provide assistance that duplicates assistance provided by an agency or organization higher in the sequence. When the delivery sequence has been disrupted, the disrupting agency is responsible for rectifying the duplication.

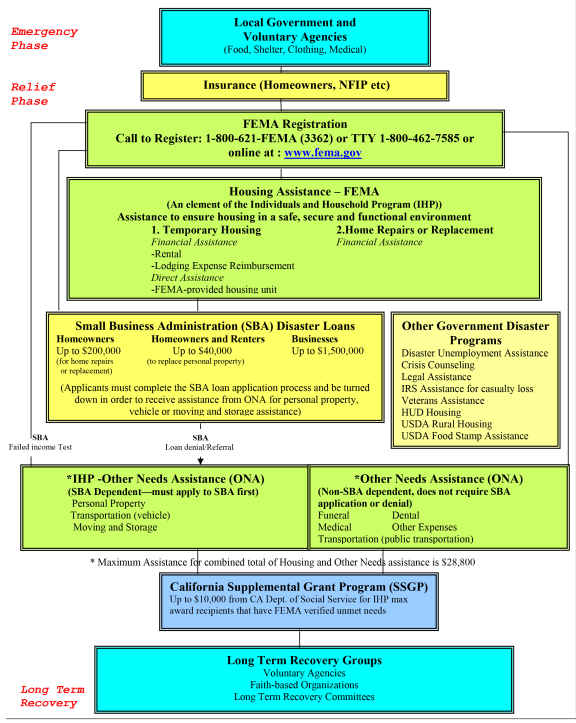

It is noteworthy that descriptions distinguishing between volunteer agency emergency assistance and volunteer agency additional assistance could not be identified. Furthermore, while FEMA's regulations do not specifically mention CDBG-DR funding, FEMA considers CDBG-DR as "other governmental assistance" (see Figure 2) that follows SBA disaster loans in the delivery sequence. Similarly, FEMA policy 9525.3 (Duplication of Benefits—Non-Government Funds) does not provide an itemized delivery sequence list.14

As demonstrated in Figure 2, a more comprehensive delivery sequence has been developed for certain incidents. However, it does not appear that this is a consistent practice for all declarations.

|

Figure 2. Example of an Incident-Specific Delivery Sequence Major Disaster Declaration for California Wildfires: 2008 |

|

|

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency, Sequence of Delivery, Individual Assistance for DR-1731-CA, 2008, at https://www.fema.gov/pdf/hazard/wildfire/ca_assist_chart.pdf. |

Delivery Sequence Issues

For a variety of reasons, the execution of the delivery sequence can be complex and lead to confusion. As mentioned previously, and as illustrated in Figure 2, assistance can be highly decentralized and can involve multiple jurisdictions as well as a vast number of agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector entities. A multitude of assistance sources can be difficult to coordinate and monitor—particularly if the entities are not communicating with each other. In addition, the delivery sequence is not rigid and can be broken in certain cases. The most common example is when adhering to the delivery sequence prevents the timely receipt of essential assistance. In some cases, assistance can be provided more quickly by an organization or agency that is lower in the sequence than an agency or organization that is at a higher level. For example, SBA disaster loans can generally be processed more quickly than grants that are released to the state, which are then disbursed by the state to disaster victims. The underlying rationale in such cases is to provide whatever assistance that is immediately available, and then recoup the assistance later to rectify the break in delivery sequence. In practice, however, this has led to problems. In some cases, the federal government may fail to identify the duplication. In others cases, it may take a prolonged period of time to identify the duplication. The notification for recoupment may come as a surprise to disaster victims who did not realize they owed money back to the government. In some instances, all of the assistance has been used for recovery needs and paying a reimbursement creates a burden for the disaster victim.

The sequence can also be broken if the lower level entity provides assistance after a higher level entity has denied assistance. In some instances, the higher level entity may later decide to reopen the case and reverse its decision. If this occurs, the higher level entity is responsible for coordinating with the lower level entity to prevent the duplication of benefits.

As noted, Congress, at its discretion, has appropriated supplemental CDBG-DR to states and communities affected by disasters. There is no automatic trigger dictating when and how much assistance is provided. As a result, some presidentially declared disasters have been appropriated funds while others have not. For example, Congress provided supplemental CDBG-DR assistance following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Midwest floods of 2008, and Superstorm Sandy that struck in 2012, but not for Hurricane Irene in 2012, or the Arkansas tornadoes in 2016.

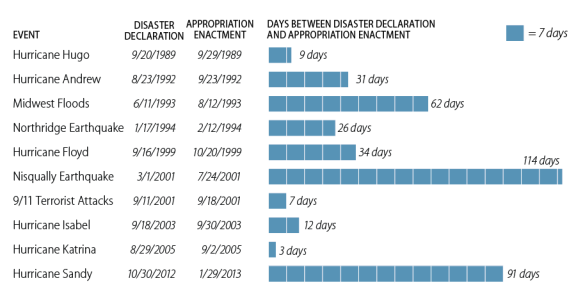

It is difficult to predict the pace or outcome of congressional consideration of legislation appropriating disaster-related CDBG funding. Figure 3 shows the time period between selected disaster events, and the provision of disaster assistance, including CDBG-DR assistance. Generally speaking, as the number of days between the disaster's declaration and the enactment of appropriation legislation increases, so does the likelihood that some applicants seeking assistance unknowingly accept assistance that creates a duplication of benefits.

|

Figure 3. Time Between Disaster Declaration and Appropriation Enactment |

|

|

Source: CRS Report R43665, Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Assistance: Summary Data and Analysis, by Bruce R. Lindsay and Justin Murray. Notes: Figure 3 reflects the number of days it took to enact the first supplemental appropriation after the declaration was issued. Some incidents (such as Hurricane Katrina) received more than one supplemental appropriation for disaster relief. |

Duplication of Benefits and Delivery Sequence Determinations

In the case of federal assistance, the FEMA Regional Administrator determines which agency is responsible for delivering assistance. If duplication is discovered, the FEMA Regional Administrator is responsible for determining whether the duplicating agency followed its own remedial procedures. If the duplicating agency followed its procedures and was successful in correcting the duplication, the FEMA Regional Administrator will take no further action. When duplication occurs under other authorities, the FEMA Regional Administrator and the Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO) should direct the duplicating agency to follow its own procedures to take corrective action, and should work with that agency toward that end.15

Selected Examples of SBA Disaster Loan and CDBG-DR Duplication Interpretations

As mentioned previously, a key issue of congressional concern has been the duplication of benefits between the SBA Disaster Loan Program and CDBG-DR. The concern stems primarily from (1) how federal agencies interpret duplication of benefit policies, and (2) how states have made CDBG-DR decisions based on whether disaster victims received a SBA disaster loan.

Federal Interpretation of Duplication of Benefits

There is evidence that the duplication of benefits regulations and laws are subject to disparate interpretations among federal agencies. This has led to some disagreement as to how the duplication of benefits policy should be implemented and remediated. For example, May 2009 and May 2010 audits conducted by the SBA Office of Inspector General (OIG) examining SBA's efforts to prevent duplication of benefits between SBA disaster loans and CDBG-DR for three states (Iowa, Louisiana, and Mississippi) found that SBA recovered $643.8 million of CDBG-DR funds from the three states and applied them to pay down 19,449 fully disbursed SBA disaster loans. The SBA also applied $281.8 million of duplicate assistance from CDBG-DR to pay down undisbursed loan balances. According to the SBA OIG, these practices were inconsistent with FEMA duplication of benefit regulations because under the FEMA regulation, agencies that are assigned a higher order in the delivery sequence are expected to provide assistance before assistance is provided by agencies at a lower level in the delivery sequence.16 Because SBA is higher in the delivery sequence than CDBG-DR assistance, the SBA OIG argued that SBA was responsible for preventing duplication of benefits. Instead of using the money to pay down SBA loans, that assistance, according to the SBA OIG, could have been made available to other disaster victims who did not qualify for SBA disaster loans.17

Additionally, according to HUD officials, after CDBG-DR program funds were depleted, it was necessary to obtain congressional approval for an additional $3 billion in supplemental funding for Louisiana. According to the SBA OIG, the additional appropriation could have been reduced by Louisiana's share of the $925.6 million had the duplicative grant assistance not been remitted to SBA to pay down disaster loans.18 According to the SBA OIG, the grants could have been used to help people with unmet needs instead of using the grant money to pay down existing loans for people who have been determined (by SBA) to have sufficient resources to repay their loans.

SBA disagreed with the SBA OIG's findings, arguing that SBA interprets the Small Business Act and SBA regulations to require that the SBA monitor the borrower's situation once a loan has been made or approved, and recover all duplicative compensation received by the borrower from any source.19

The SBA OIG revisited the duplication of benefits issue roughly five years later and conducted another audit (published on July 31, 2015). The new audit consisted of meeting with key personnel at the SBA's Fort Worth Processing and Disbursement Center and examining SBA's internal controls to prevent a duplication of payment. The SBA OIG also tested a random sample of CDBG-DR grants to determine if duplication controls appeared to be working as intended.

The SBA OIG concluded the SBA's controls to prevent duplication of benefits with CDBG-DR were adequately designed and working as intended. The SBA OIG noted however, that the recommendations from the earlier audits were primarily geared toward having SBA, in coordination with HUD and FEMA, develop agreements and roles consistent with sequence of delivery outlined in 44 C.F.R. 206.191. Rather than the SBA, it was HUD that took the initiative and issued the November 16, 2011, Federal Register Notice discussed earlier in this report (see Table 1). Based on the findings, the SBA OIG stated that there were no reportable conditions or recommendations.20

After reviewing the audit report, some may argue that HUD's Notice has adequately reconciled how duplication of benefit regulations should be interpreted by federal entities. Others might argue that while the controls may seem to be working now, they may not work in the event of a large-scale disaster. In support of this argument, they may point out that there has not been a large-scale disaster in need of a supplemental appropriation since Hurricane Sandy. They may therefore conclude that the controls have yet to be sufficiently tested. If the controls are overwhelmed by a large-scale disaster, remediating duplication of benefits may once again be subject to differing interpretations.

In addition, with respect to the Federal Register Notice, some may argue that it essentially introduces yet another federal interpretation to existing ones. They may further argue that it would be better to align laws and regulations to eliminate possible interpretations rather using a suggested framework to address the issue.

State and Local Interpretation of Duplication of Benefits

As mentioned previously, on November 16, 2011, HUD published a Notice in the Federal Register intended to provide guidance regarding the framework and processes to be used by state and local government grantees of CDBG-DR funding in determining if a duplication of benefits has and potentially may occur. The Notice neither prescribes nor mandates the specific processes to be used by state and local government grantees in identifying potential duplication of benefits. However, the sequence outlined in the notice is consistent with guidelines outlined in the Stafford Act, and FEMA and SBA regulations and guidance documents. Most importantly, the Notice was intended to clarify duplication of benefits requirements in an effort to ensure consistency in the use of CDBG-DR funds in compliance with the Stafford Act. The duplication of benefits requirements outlined in the Notice were intended to apply to active CDBG-DR grants dating back to 2001, as well as to future CDBG-DR grant allocations.

Avoiding a duplication of benefits in the awarding of CDBG-DR funds is complicated by a number of factors. One area of concern has been the implementation and timing of the delivery sequence. For example, following Hurricane Sandy, which hit the east coast of the United States in late October 2012, homeowners whose homes were damaged by the storm were advised to apply to the SBA for a low interest disaster loan to repair their homes. Subsequently, these homeowners were later informed that they were ineligible for CDBG-DR grant funds under the New York City Build It Back program because the receipt of a SBA loan constitutes a duplication of benefits as articulated in FEMA regulations and the CDBG-DR guidance document published on November 16, 2011.

In the case of CDBG-DR funds used to establish the New York City Build It Back program in 2013, residents who initially were approved for SBA disaster loans were deemed ineligible to receive grants under the NYC Build It Back program even if the homeowner had not accepted the loan. For example, a homeowner approved for a $150,000 loan from the SBA, but who did not actually take it, would not be eligible for $150,000 worth of assistance from NYC Build it Back. Should NYC Build it Back determine that this homeowner, for example, needs additional repair assistance beyond the $150,000, SBA retains the right of first refusal and can determine whether or not a homeowner will receive this additional assistance. Affected homeowners complained that the policy prevented them from receiving the assistance needed to complete repairs of their storm-damaged homes and penalized those who refused the SBA loans in an effort to avoid additional debt during a time of hardship.

At the urging of the New York congressional delegation, on July 25, 2013, HUD updated its policy guidance to allow greater flexibility for homeowners who originally rejected SBA disaster loan assistance. The guidance document focused exclusively on the question of whether CDBG-DR grantees can assist households and businesses that have declined SBA assistance. The document allows grantees to award CDBG-DR funds to households and businesses that have declined SBA, but before doing so the grantee must analyze and document reasons SBA assistance was declined and identify why the provision of CDBG-DR assistance is necessary and reasonable.21 Prior to this arrangement, grantees were required to reduce CDBG-DR assistance by the amount of the homeowner's approved SBA disaster loan.

Policy Options

Revise FEMA Regulations

As mentioned previously, FEMA's regulations do not specifically mention CDBG-DR funding in the delivery sequence. In practice, FEMA considers CDBG-DR funding as assistance that follows SBA disaster loans in the delivery sequence. However, leaving CDBG-DR unmentioned in FEMA's regulation could lead to confusion as to where CDBG-DR is ranked in the delivery sequence. It may also be argued that the omission makes the delivery sequence open to interpretation. If Congress is concerned that the omission could lead to confusion or different interpretations of code, Congress could require that 44 C.F.R. 206.191 be revised to specify the location of CDBG-DR within the delivery sequence.

Prohibit SBA Disaster Loan Recipients from Receiving CDBG-DR

Some might argue that people and businesses that qualify for SBA disaster loans should not be eligible for CDBG-DR grants. They may contend that individuals who are determined to have sufficient resources to repay a SBA disaster loan should not receive CDBG-DR assistance, particularly grant assistance. Grants, they would argue, should only go to those who cannot recover and rebuild on their own.

Annual Appropriations for CDBG-DR

Most federal disaster assistance programs are funded through annual appropriations. This generally ensures that the programs have funds available when an incident occurs. As a result, these programs can provide assistance in a relatively short period of time. For example, a July 2015 SBA OIG study found that SBA's processing time for home disaster loans averaged 18.7 days and application processing times for business disaster loans averaged 43.3 days.22

CDBG disaster assistance, on the other hand, is funded through supplemental funding. In general, Congress only provides supplemental funding when disaster needs exceed the amount available through annual appropriations. This typically only occurs when a large incident takes place, such as hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. Consequently, funding for CDBG-DR is not available for all incidents. In addition, Congress must debate and pass supplemental funding. As demonstrated earlier in Figure 3, on average, Congress has passed supplemental appropriations for disaster assistance within 38.9 days of the disaster declaration. In a few cases, supplemental funding has been provided in less than a week after an incident (for example, Hurricane Katrina and 9/11 received funding in three days and seven days respectively).

CDBG-DR assistance is not immediately made available after an appropriation. For example, an appropriation for CDBG-DR was enacted on June 3, 2008. The allocation date for the CDBG-DR was September 11, 2008—three months after the enacted appropriation.

In addition to the amount of time it can take to pass a supplemental appropriation, it takes some time for HUD to formulate distribution formulas for multiple states. Consequently, CDBG-DR is generally provided later than other forms of disaster assistance. This explains, in part, why the delivery sequence is often broken—because other forms of assistance can be provided more quickly.

One potential option would be to fund CDBG-DR through annual appropriations. Doing so would create an account with funds that could be made immediately available and help expedite CDBG-DR assistance. This option may eliminate gaps and confusion in the delivery sequence because a recipient could potentially receive CDBG-DR assistance around the same time that a SBA disaster loan could be processed. The annual appropriation could be designed similarly to FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund (DRF). Funds from the DRF are used by FEMA to pay for ongoing recovery projects from disasters occurring in previous fiscal years, to meet current emergency requirements, and as a reserve to pay for upcoming incidents. The DRF is funded annually and is a "no-year" account, meaning that unused funds from the previous fiscal year (if available) are carried over to the next fiscal year. In general, when the balance of the DRF becomes low, Congress provides additional funding through both annual and supplemental appropriations to replenish the account.23

Critics of this policy option might argue that if this approach were used, it would be necessary to determine under what situations CDBG-DR assistance would be released. Similarly, as mentioned previously, CDBG-DR assistance is typically only available for large-scale incidents. Creating a permanent CDBG-DR might provide a gateway for smaller incidents to receive CDBG-DR assistance. This, in turn, might lead to increased federal expenditures for disaster assistance.

State Disbursement of CDBG-DR

The federal government allows states to exercise considerable discretion with respect to awarding CDBG-DR assistance, which is often, but not always, in the form of a grant. In some cases, states have made the decision to deny CDBG-DR assistance to SBA disaster loan recipients. The rationale for this decision is that if the recipient has the ability to obtain an SBA disaster loan, then they possess sufficient resources to recover without a grant. Some argue that individuals who are determined to have sufficient resources to repay their SBA disaster loans should not receive grant money because grants are not repaid, which places the financial burden on taxpayers.

It is not uncommon for SBA loan recipients to see the denial of a CDBG-DR grant as an equity issue. Some question why they have to pay off a loan to repair and recover from a disaster, while others receive grant money in response to the same disaster. Furthermore, they tend to blame the federal government for CDBG-DR award decisions when, in fact, these decisions have been made by the state.

Congress could potentially address this issue of perception by requiring uniformity in the distribution of CDBG-DR assistance. Congress could require that states provide CDBG-DR assistance to all eligible SBA disaster loan recipients. Alternatively, Congress could pass legislation that makes people and businesses eligible for SBA loans, ineligible for CDBG-DR assistance. Both methods would likely create uniformity with respect to CDBG-DR awards. Some, however, may say the latter approach would not address the perception issue.

Assistance Database

One potential method of addressing duplication is creating and managing a single database that tracks assistance to individuals and businesses from multiple sources. The system could alert recipients that they are at risk of duplicating assistance. The system might also be used for more timely identification of duplication of benefits. FEMA already coordinates with SBA through FEMA's disaster assistance website, http://www.disasterassistance.gov. Congress could examine whether the website could be modified to track duplication of assistance in a more robust manner. Critics might argue, however, that such a system would not identify all cases of duplication because some individuals and businesses might fail to self-report their assistance. This could be intentional or unintentional.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Amber Wilhelm, Graphics Specialist, Publishing and Editorial Resources Section, assisted with figures in this report. Jared C. Nagel, Information Research Specialist, Government and Finance Section, assisted with appropriations information for this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For information FEMA disaster assistance see CRS Report R43560, Deployable Federal Assets Supporting Domestic Disaster Response Operations: Summary and Considerations for Congress, coordinated by Jared T. Brown; and CRS Report R43990, FEMA's Public Assistance Grant Program: Background and Considerations for Congress, by Jared T. Brown and Daniel J. Richardson. For more information on federal disaster assistance see CRS Report R41981, Congressional Primer on Responding to Major Disasters and Emergencies, by Francis X. McCarthy and Jared T. Brown. |

| 2. |

For more information on presidential disaster declarations see CRS Report R43784, FEMA's Disaster Declaration Process: A Primer, by Francis X. McCarthy; and CRS Report R42702, Stafford Act Declarations 1953-2014: Trends, Analyses, and Implications for Congress, by Bruce R. Lindsay and Francis X. McCarthy. |

| 3. |

For more information on SBA disaster loans see CRS Report R44412, SBA Disaster Loan Program: Frequently Asked Questions, by Bruce R. Lindsay, and CRS Report R41309, The SBA Disaster Loan Program: Overview and Possible Issues for Congress, by Bruce R. Lindsay. For more information on the Community Development Block Program see CRS Report R43520, Community Development Block Grants and Related Programs: A Primer, by Eugene Boyd; CRS Report RL33330, Community Development Block Grant Funds in Disaster Relief and Recovery, by Eugene Boyd; and CRS Report R43394, Community Development Block Grants: Recent Funding History, by Eugene Boyd. |

| 4. |

Home and Personal Property Disaster Loans provide assistance to homeowners and renters for real and personal property including up to $200,000 to homeowners for real estate and up to $40,000 for personal property. SBA may provide an additional 20% of the eligible loan amount for mitigation activities; Business Physical Disaster Loans provide up to $2 million to help businesses of all sizes and nonprofit organizations repair or replace disaster-damaged property, including inventory and supplies; and Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL) provide assistance to small businesses, small agricultural cooperatives (but not enterprises), and certain private, nonprofit organizations that have suffered substantial economic injury resulting from a physical disaster or an agricultural production disaster. EIDLs provide up to $2 million in financial assistance to businesses located in a disaster area that have suffered economic injury as a result of a declared disaster (regardless if there has been physical damage to the business). |

| 5. |

Department of Housing and Urban Development, Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Program, HUD Exchange, 2014, available at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/cdbg-dr/. |

| 6. |

For more information about CDBG, see CRS Report RL33330, Community Development Block Grant Funds in Disaster Relief and Recovery, by Eugene Boyd. |

| 7. |

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, "CDBG-DR Eligibility Requirements," at https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/cdbg-dr/cdbg-dr-eligibility-requirements/. |

| 8. |

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Congressional Budget Justification FY2017, Community Development Fund, Washington, DC, February 2017, pp. 15-9, at http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=15-Community_Dev.Fund.pdf. |

| 9. |

42 U.S.C. §5155. |

| 10. |

Note that certain disaster recover activities may be eligible for the use of regular CDBG funding with the need for a waiver, such as providing temporary housing for disaster victims (see 24 C.F.R. 570.201(c). |

| 11. |

The first supplemental appropriations providing CDBG-DR for disaster recovery was included was P.L. 103-50, Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1993, which appropriated $45 million for community development activities only in areas affected by Hurricane Andrew, Hurricane Iniki, or Typhoon Omar. |

| 12. |

Charles Schumer, "Schumer: HUD Will Waive 'Duplication of Benefits' Review for Nearly All Super Storm Sandy Victims, Allowing Them to Keep Flood Insurance Settlement Funds Without Fear of Claw-Back; at Last Minute, FEMA Will Also Extend Sandy Claims Review Process So More Homeowners Can Apply," press release, September 16, 2015, at https://www.schumer.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/schumer-hud-will-waive-duplication-of-benefits-review-for-nearly-all-superstorm-sandy-victims-allowing-them-to-keep-flood-insurance-settlement-funds-without-fear-of-claw-back-at-last-minute-fema-will-also-extend-sandy-claims-review-process-so-more-homeowners-can-apply_. |

| 13. |

For an example see, "HUD Policy Revision Lets Sandy Victims Get Grant Money for Home Repair," Asbury Park Press, July 17, 2013. |

| 14. |

Federal Emergency Management Agency, 9525.3 Duplication of Benefits—Non-Government Funds, DAP9525.3, February 18, 2016, at https://www.fema.gov/9500-series-policy-publications/95253-duplication-benefits-non-government-funds. |

| 15. |

42 U.S.C. §5144. |

| 16. |

Debra S. Ritt, Report on SBA's Role in Addressing Duplication of Benefits between SBA Disaster Loans and Community Development Block Grants, U.S. Small Business Administration Office Inspector General, Report No. 10-13, September 2, 2010, p. 2, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/oig/oig_report_10-13_cgdb.pdf. |

| 17. |

Ibid, p. 2. |

| 18. |

Ibid, p. 7. |

| 19. |

Ibid, p. 7. |

| 20. |

Small Business Administration, Office of the Inspector General, SBA's Controls to Prevent Duplication of Benefits with Community Development Block Grants, Audit Report 15-14, July 31, 2015, p. 4, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/oig/SBA_Controls_to_Prevent_Duplication_of_Benefits_with_CDBG.pdf. |

| 21. |

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD Guidance on Duplication of Benefit Requirements and Provision of CDBG Disaster Recovery (DR) Assistance, Washington, DC, July 25, 2013, p. 1, at https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/CDBG-DR-Duplication-of-Benefit-Requirements-and-Provision-of-Assistance-with-SBA-Funds.PDF. |

| 22. |

U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Hurricane Sandy Expedited Loan Processes, Audit Report No. 15-13, July 13, 2015, p. 4, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/oig/Audit_Report_15-13_Sandy_Expedited_Processes.pdf. |

| 23. |

The Obama Administration included language in its FY2017 budget request outlining its intent to develop a standing authorization proposal for CDBG-DR funds. The proposal would provide clarity and predictability regarding the availability of CDBG-DR funds and would improve the alignment of CDBG-DR funds with other federal disaster programs. |