U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy

Family reunification has historically been a key principle underlying U.S. immigration policy. It is embodied in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which specifies numerical limits for five family-based immigration categories, as well as a per-country limit on total family-based immigration. The five categories include immediate relatives (spouses, minor unmarried children, and parents) of U.S. citizens and four other family-based categories that vary according to individual characteristics such as the legal status of the petitioning U.S.-based relative, and the age, family relationship, and marital status of the prospective immigrant.

Of the 1,183,505 foreign nationals admitted to the United States in FY2016 as lawful permanent residents (LPRs), 804,793, or 68%, were admitted on the basis of family ties. Of the family-based immigrants admitted in FY2016, 70% were admitted as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Many of the 1,183,505 immigrants were initially admitted on a nonimmigrant (temporary) visa and became immigrants by converting or “adjusting” their status to a lawful permanent resident. The proportion of family-based immigrants who adjusted their immigration status while residing in the United States (34%) was substantially less than that of family-based immigrants who had their immigration petitions processed while living abroad (66%), although such percentages varied considerably among the five family-based immigration categories.

Since FY2000, increasing numbers of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens have accounted for the growth in family-based immigration. In FY2016, related (derivative) immigrants who accompanied or later followed principal (qualifying) immigrants accounted for 9% of all family-based immigration. In recent years, Mexico, the Philippines, China, India, and the Dominican Republic have sent the most family-based immigrants to the United States.

Each year, the number of foreign nationals petitioning for LPR status through family-sponsored preference categories exceeds the numerical limits of legal immigrant visas. As a result, a visa queue has accumulated of foreign nationals who qualify as immigrants under the INA but who must wait for a visa to immigrate to the United States. The visa queue is not a processing backlog but, rather, the number of persons approved for visas not yet available due to INA-specified numerical limits. As of November 1, 2017, the visa queue numbered 3.95 million persons.

Every month, the Department of State (DOS) issues its Visa Bulletin, which lists “cut-off dates” for each numerically limited family-based immigration category. Cut-off dates indicate when petitions that are currently being processed for a numerically limited visa were initially approved. For most countries, cut-off dates range between 23 months and 13.5 years ago. For countries that send the most immigrants, the range expands to between 2 and 23 years ago.

Long-standing debates over the level of annual permanent immigration regularly place scrutiny on family-based immigration and revive debates over whether its current proportion of total lawful permanent immigration is appropriate. Proposals to overhaul family-based immigration were made by two congressionally mandated commissions in 1980 and 1995-1997. More recent legislative proposals to revise family-based immigration include S. 744, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act in the 113th Congress and S. 1720, the Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy (RAISE) Act in the 115th Congress.

Those who favor expanding family-based immigration by increasing the annual numeric limits point to the visa queue of approved prospective immigrants who must wait years separated from their U.S.-based family members until they receive a visa. Others question whether the United States has an obligation to reconstitute families of immigrants beyond their nuclear families and favor reducing permanent immigration by eliminating certain family-based preference categories. Arguments favoring restricting certain categories of family-based immigration reiterate earlier recommendations made by congressionally mandated immigration reform commissions.

U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Overview of Family-Based Immigration

- Evolution of U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy

- Current Laws on Family-based Immigration

- Legal Immigration Limits

- Per-Country Ceilings

- Laws Governing the Immigration Process

- Procedures for Acquiring Lawful Permanent Residence

- Derivative Immigrants

- Child Immigrants

- Conditional Resident Status

- Same-Sex Partners

- Profile of Legal Immigrants

- Legal Immigration Trends

- Legislative and Policy Issues

- Supply-Demand Imbalance for U.S. Lawful Permanent Residence

- Assessing the Per-Country Ceiling

- Limitations on Visiting U.S. Relatives

- Impetus to Violate Immigration Laws

- Aging Out of Legal Status Categories

- Marriage Timing of Immigrant Children

- Unaccompanied Alien Children

- Broader Immigration Questions

- Findings from Earlier Congressionally Mandated Commissions

- Family Reunification versus Family Reconstitution

- Family Reunification versus Economic Priorities

- "Chain Migration"

- Selected Legislative Activity

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Numerical Limits of the Immigration and Nationality Act

- Table 2. Actual Family-Sponsored Immigration by Major Class in FY2016

- Table 3. Principal and Derivative Immigrants, by LPR Category, FY2016

- Table 4. Visa Queue of Prospective Family-Preference Immigrants with Approved Applications, for Selected Countries, as of November 1, 2017

- Table 5. Cut-Off Dates for Family-Based Petitions, February 2018

- Table A-1. Annual Number of Lawful Permanent Residents by Major Class, FY2006-FY2016

- Table A-2. Annual Number of Lawful Permanent Residents by Major Class, FY1996-FY2005

- Table A-3. Percentages of Annual Lawful Permanent Residents by Major Class, FY2006-FY2016

- Table A-4. Percentages of Annual Lawful Permanent Residents by Major Class, FY1996-FY2005

- Table A-5. Key Proportions for Annual Lawful Permanent Residents, FY2006-FY2016

- Table A-6. Key Proportions for Annual Lawful Permanent Residents, FY1996-FY2005

Summary

Family reunification has historically been a key principle underlying U.S. immigration policy. It is embodied in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which specifies numerical limits for five family-based immigration categories, as well as a per-country limit on total family-based immigration. The five categories include immediate relatives (spouses, minor unmarried children, and parents) of U.S. citizens and four other family-based categories that vary according to individual characteristics such as the legal status of the petitioning U.S.-based relative, and the age, family relationship, and marital status of the prospective immigrant.

Of the 1,183,505 foreign nationals admitted to the United States in FY2016 as lawful permanent residents (LPRs), 804,793, or 68%, were admitted on the basis of family ties. Of the family-based immigrants admitted in FY2016, 70% were admitted as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Many of the 1,183,505 immigrants were initially admitted on a nonimmigrant (temporary) visa and became immigrants by converting or "adjusting" their status to a lawful permanent resident. The proportion of family-based immigrants who adjusted their immigration status while residing in the United States (34%) was substantially less than that of family-based immigrants who had their immigration petitions processed while living abroad (66%), although such percentages varied considerably among the five family-based immigration categories.

Since FY2000, increasing numbers of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens have accounted for the growth in family-based immigration. In FY2016, related (derivative) immigrants who accompanied or later followed principal (qualifying) immigrants accounted for 9% of all family-based immigration. In recent years, Mexico, the Philippines, China, India, and the Dominican Republic have sent the most family-based immigrants to the United States.

Each year, the number of foreign nationals petitioning for LPR status through family-sponsored preference categories exceeds the numerical limits of legal immigrant visas. As a result, a visa queue has accumulated of foreign nationals who qualify as immigrants under the INA but who must wait for a visa to immigrate to the United States. The visa queue is not a processing backlog but, rather, the number of persons approved for visas not yet available due to INA-specified numerical limits. As of November 1, 2017, the visa queue numbered 3.95 million persons.

Every month, the Department of State (DOS) issues its Visa Bulletin, which lists "cut-off dates" for each numerically limited family-based immigration category. Cut-off dates indicate when petitions that are currently being processed for a numerically limited visa were initially approved. For most countries, cut-off dates range between 23 months and 13.5 years ago. For countries that send the most immigrants, the range expands to between 2 and 23 years ago.

Long-standing debates over the level of annual permanent immigration regularly place scrutiny on family-based immigration and revive debates over whether its current proportion of total lawful permanent immigration is appropriate. Proposals to overhaul family-based immigration were made by two congressionally mandated commissions in 1980 and 1995-1997. More recent legislative proposals to revise family-based immigration include S. 744, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act in the 113th Congress and S. 1720, the Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy (RAISE) Act in the 115th Congress.

Those who favor expanding family-based immigration by increasing the annual numeric limits point to the visa queue of approved prospective immigrants who must wait years separated from their U.S.-based family members until they receive a visa. Others question whether the United States has an obligation to reconstitute families of immigrants beyond their nuclear families and favor reducing permanent immigration by eliminating certain family-based preference categories. Arguments favoring restricting certain categories of family-based immigration reiterate earlier recommendations made by congressionally mandated immigration reform commissions.

Overview of Family-Based Immigration

The United States has long distinguished settlement or permanent immigration from temporary immigration. Current U.S. immigration policy governing lawful permanent immigration emphasizes four major principles: (1) family reunification; (2) immigration of persons with needed skills; (3) refugee protection; and (4) country-of-origin diversity.

Family reunification, which has long been a key principle underlying U.S. immigration policy, is embodied in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, as amended1 (INA), which specifies five categories of family-based2 immigrants. These include the numerically unlimited category of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens (spouses, minor children, and parents) and four numerically limited family preference categories. The latter vary according to individual characteristics such as the citizenship status of the petitioning U.S.-based relative, and the age, family relationship, and marital status of the prospective immigrant.3 In addition, the INA limits family preference immigration from any single country to 7% of each category's total.

Family-based immigration currently makes up two-thirds of all legal permanent immigration.4 Each year, the number of foreign nationals petitioning for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status exceeds the total number of immigrants that the United States can accept annually under the INA. Consequently, a visa queue has accumulated with roughly 4 million persons who qualify as family-based immigrants under the INA but who must wait for a numerically limited visa to immigrate to the United States.5

Interest in immigration reform and concerns over "chain migration"—a term that some use to characterize the process by which family-based immigration allows foreign nationals who obtain LPR status and citizenship to then sponsor other relatives under the family-based immigration provisions—has increased scrutiny of family-based immigration and has revived discussion about the appropriate number of annual permanent immigrants.6 This report reviews family-based immigration policy. It outlines a brief history of U.S. family-based immigration policies, discusses current law governing family-based immigration, and summarizes recommendations made by previous congressionally mandated commissions charged with evaluating immigration policy. It then presents data on legal immigrants entering the United States during the past decade and discusses the queue of approved immigrant petitioners waiting for an immigrant visa. It closes by discussing selected policy issues and legislative proposals.

Evolution of U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy

Although U.S. immigration policy incorporated family relationships as a basis for admitting immigrants as early as the 1920s,7 the promotion of family reunification found in current law originated with the passage of the INA in 1952.8 While the 1952 act largely retained the national origins quota system established in the Immigration Act of 1924,9 it also established a hierarchy of family-based preferences that continues to govern contemporary U.S. immigration policy, including prioritizing spouses and minor children over other relatives, as well as relatives of U.S. citizens over those of LPRs.

The Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965 (P.L. 89-236), enacted during a period of broad social reform, eliminated the national origins quota system, which was widely viewed as discriminatory.10 It gave priority to immigrants with relatives living permanently in the United States. The law distinguished between immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, who were admitted without numerical restriction, and other relatives of U.S. citizens and immediate and other relatives of LPRs, who faced numerical caps. It also imposed a per-country limit on family-based and employment-based immigrants that limited any single country's total for these categories to 7% of the statutory total. 11

Twenty-five years later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-649), which increased total immigration under what some have called a "permeable cap."12 The act provided for a permanent annual flexible cap of 675,000 immigrants, and increased the annual statutory limit of family-based immigrants from 290,000 to the current limit of 480,000. Provisions of the 1990 act are described later in this report in the section titled "Current Laws on Family-based Immigration."

Current U.S. immigration policy retains key elements of its landmark 1952 and 1965 reformulations. Given that continuity in immigration policy, earlier recommendations for revising family-based immigration policy to address certain perennial issues—in particular, the large "visa queue" of prospective family-based immigrants awaiting a numerically limited visa, and the high proportion of immigrants who enter based upon family ties—still have relevance.13 Key reform proposals originated from two congressionally mandated commissions established to evaluate U.S. immigration policy. Recommendations from these commissions are discussed in the section of this report titled "Findings from Earlier Congressionally Mandated Commissions."

Current Laws on Family-based Immigration

Legal Immigration Limits

The INA enumerates a permanent annual worldwide level of 675,000 immigrants14 (Table 1). This limit, sometimes referred to as a "permeable cap," is regularly exceeded because immigration for certain LPR categories is unlimited.15 The permanent annual worldwide immigrant level includes

- 1. family-sponsored immigrants (480,000 plus certain unused employment-based preference numbers from the prior year);

- 2. employment-based preference immigrants (140,000 plus certain unused family preference numbers from the prior year); and

- 3. diversity visa lottery immigrants16 (55,000).17

Family-sponsored immigrants include five categories (Table 1). The first, immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, includes spouses, unmarried minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens.18 Immediate relatives can become LPRs without numerical limitation, provided they meet standard eligibility criteria required of all immigrants.19

The next four categories, family preference immigrants, are numerically limited. The first includes unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens. The second includes two subgroups of relatives of lawful permanent residents, each subject to its own numerical limit: the first subgroup (referred to as 2A) includes spouses and unmarried minor children of LPRs, and the second subgroup (referred to as 2B) includes unmarried adult children of LPRs. The third family preference category includes adult married children of U.S. citizens, and the fourth includes siblings of adult U.S. citizens.

|

Family-Sponsored Immigrants |

480,000 |

||||||||

|

Immediate Relatives of U.S. Citizens: |

unlimited |

||||||||

|

Family Preference Immigrants: |

226,000 |

||||||||

|

1st Preference: |

Unmarried sons and daughters of citizens |

23,400 |

|||||||

|

+ unused 4th Preference visas |

|

||||||||

|

2nd Preference (A): |

Spouses and minor children of LPRs |

87,900 |

|||||||

|

2nd Preference (B): |

Unmarried sons and daughters of LPRs |

26,300 |

|||||||

|

+ unused 1st Preference visas |

|||||||||

|

3rd Preference: |

Married children of citizens |

23,400 |

|||||||

|

+ unused 1st and 2nd Preference visas |

|||||||||

|

4th Preference: |

Siblings of adult U.S. citizens |

65,000 |

|||||||

|

+ unused 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Preference visas |

|

||||||||

|

Employment-Based Preference Immigrants |

140,000 |

||||||||

|

Diversity Visa Lottery Immigrants |

55,000 |

||||||||

|

TOTAL |

675,000 |

||||||||

Source: CRS summary of INA §203(a) and §204; 8 U.S.C. §1153.

Notes: Figures in italics sum to the non-italicized total of 226,000 for family preference immigrants.

The annual level of family preference immigrants is determined by subtracting the number of visas issued to immediate relatives of U.S. citizens in the previous year, plus the number of aliens paroled into the United States for at least a year, from 480,000 (the total family-sponsored level) and adding—when available—employment preference immigrant numbers unused during the previous year.20 Unused visas in each category roll down to the next preference category.

Under the INA, the annual level of family preference immigrants may not fall below 226,000. If the number of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens admitted in the previous year happens to fall below 254,000 (the difference between 480,000 for all family-based immigrants and 226,000 for family preference immigrants), then family preference immigrants may exceed 226,000 by that amount. However, since FY1996, annual immediate relative immigrants have exceeded 254,000 each year, ranging from a low of 258,584 immigrants in FY1999 to a high of 580,348 immigrants in FY2006.21 As such, the annual limit of family preference immigrants effectively has remained at 226,000 for the past two decades.22

|

Number |

Percentage |

||

|

Total Family-Sponsored Immigrants |

804,793 |

|

|

|

Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens |

566,706 |

70.4% |

|

|

(A) Spouses |

304,358 |

37.8% |

|

|

(B) Minor children |

88,494 |

11.0% |

|

|

(C) Parents |

173,854 |

21.6% |

|

|

Family-preference immigrants |

238,087 |

29.6% |

|

|

1st Preference: Unmarried sons and daughters of U.S. citizens |

22,072 |

2.7% |

|

|

2nd Preference: Spouses and children of LPRs |

121,267 |

15.1% |

|

|

(A) Spouses |

42,089 |

5.2% |

|

|

(A) Minor children |

62,652 |

7.8% |

|

|

(B) Unmarried sons and daughters |

16,526 |

2.1% |

|

|

3rd Preference: Married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens |

27,392 |

3.4% |

|

|

4th Preference: Siblings of U.S. citizens |

67,356 |

8.4% |

Source: CRS presentation of data from 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Tables 6 and 7, Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics.

Note: Figures in italics sum to the non-italicized figure immediate above them. Indented figures sum up to figures immediately above them. Percentages may not sum completely due to rounding. Differences between the actual number of family preference immigrants shown above and the statutorily determined number shown in Table 1 result from category "roll-downs" (unused visas in one category rolling down to the next) and fiscal year differences between when visa petitions were approved versus when the immigrants were admitted to the United States. For more information, see Ryan Baugh, U.S. Lawful Permanent Residents: 2016, Office of Immigration Statistics, Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC, December 2017.

Reflecting the INA's numerical limits, actual legal immigration to the United States is dominated by family-based immigration. In FY2016, a total of 804,793 family-based immigrants made up just over two-thirds (68%) of all 1,183,505 new LPRs.23 This proportion has remained stable for the past decade (see Table A-1, Table A-3, and Table A-5). The 566,706 immediate relatives in FY2016 represented over two thirds (70%) of all family-based immigration and almost half (48%) of all legal permanent immigration (Table 2).

Per-Country Ceilings

In addition to annual numerical limits on family preference immigrants, the INA limits LPRs from any single country to 7% of the total annual limit of family preference and employment-based preference immigrants.24 The per-country limit does not indicate that a country is entitled to the maximum number of visas each year, but only that it cannot receive more than that number. Two exemptions from this rule include all immediate relatives of U.S. citizens; and 75% of all visas allocated to second (2A) family preference immigrants (spouses and children of LPRs).25 Because the number of foreign nationals potentially eligible for a visa exceeds the annual visa limit under current law, waiting times for available family-based visas can extend for years, particularly for persons from countries with many petitioners, such as India, China, Mexico, and the Philippines. For further discussion, see the sections later in this report titled, "Supply-Demand Imbalance for U.S. Lawful Permanent Residence" and "Assessing the Per-Country Ceiling."

Laws Governing the Immigration Process

Procedures for Acquiring Lawful Permanent Residence

Becoming an LPR on the basis of a family relationship first requires that the petitioning or sponsoring U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident in the United States establish his or her relationship with the prospective LPR. To do so, the sponsor must first file Form I-130 Petition for Alien Relative with DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).26 Upon approval of the Form I-130, the prospective LPR must file a Form I-485 Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status. Immediate relatives, unlike family-preference immigrants, can file both petitions concurrently.

If the prospective LPR already resides legally in the United States, USCIS handles the entire adjustment of status process whereby the alien adjusts from a nonimmigrant27 category (which had initially permitted him or her to enter the United States legally) to LPR status.28 If the prospective LPR does not reside in the United States, USCIS must review and approve the petition before forwarding it to the Department of State's (DOS's) Bureau of Consular Affairs in the prospective immigrant's home country.

The DOS Consular Affairs officer, when the alien lives abroad, or USCIS adjudicator, when the alien is adjusting status within the United States, must be satisfied that the alien is entitled to LPR status. Such reviews ensure that potential immigrants are not ineligible for visas or admission under the inadmissibility grounds in the INA. In both cases, if the petition is approved, DOS determines whether a visa is available for the foreign national's immigrant category. Available visas are issued by "priority date," the filing date of their permanent residence petition. For more information, see the section on "Supply-Demand Imbalance for U.S. Lawful Permanent Residence" in this report.

While the INA contains multiple grounds for inadmissibility, the public charge ground (i.e., the individual cannot support him or herself financially and must rely upon the state) is particularly relevant for family-sponsored immigration. All family-based immigration requires that U.S.-based citizens and LPRs petitioning on behalf of (or sponsoring) their alien relatives submit a legally enforceable affidavit of support along with evidence that they can support both their own family and that of the sponsored alien at an annual income no less than 125% of the federal poverty level.29 Alternatively, sponsors may share this responsibility with one or more joint sponsors, each of whom must independently meet the income requirement. Current law also directs the federal government to include "appropriate information" regarding affidavits of support in the Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) system.30 This level of support is legally mandated for 10 years or until the sponsored alien becomes a U.S. citizen.31

Laws for adjusting status vary depending on how the foreign national entered the United States. If a foreign national entered the United States legally, overstayed his or her visa, and then married a U.S. citizen, he or she can adjust status under INA §245(a), assuming other requirements for admissibility are met. However, if a foreign national under the same circumstances married an LPR instead of a U.S. citizen, the INA treats such individuals as unauthorized aliens who entered illegally: they must leave the country, and are barred from re-entering for either 3 years or 10 years, depending on whether they resided in the United States illegally for 6-12 months or for more than 12 months, respectively.32

Derivative Immigrants

Spouses and children who accompany or later follow qualifying or principal immigrants are referred to as derivative immigrants. Under current law, derivative immigrants are entitled to the same status and same order of consideration as the principal immigrants they accompany or follow-to-join,33 assuming they are not entitled to an immigrant status and the immediate issuance of a visa under another section of the INA.34 As such, derivative immigrants count equally as principal immigrants within the numerical limits of each immigration category. For instance, the 67,356 immigrants admitted under the 4th family preference category (siblings of U.S. citizens) in FY2016 (Table 2) include 23,815 qualifying immigrants or actual siblings of U.S. citizens as well as 16,468 spouses of qualifying immigrants and 27,073 children of qualifying immigrants. Derivative immigrant status attaches to approval of the principal immigrant's petition and requires no separate petition.35

In contrast, children classified as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens are not treated by the INA as derivatives and must each have a separate petition filed on their behalf. In FY2016, derivative immigrants represented 9% of all family-based immigration, 43% of all other immigrant categories, and 20% of total immigration.36

|

Immigrant Type |

Immediate Relatives of USCs |

1st Preference: Unmarried Sons & Daughters of USCs |

2nd Preference: Spouses & Unmarried Children of LPRs |

3rd Preference: Married Sons & Daughters of USCs |

4th Preference: Siblings of USCs |

All Other Lawful Permanent Residents |

Total Lawful Permanent Residents |

|

Numbers of Immigrants |

|||||||

|

Principal |

566,703 |

13,901 |

121,247 |

8,088 |

23,815 |

215,344 |

949,098 |

|

Derivative |

— |

8,041 |

— |

19,292 |

43,541 |

163,343 |

234,217 |

|

Total |

566,703 |

21,942 |

121,247 |

27,380 |

67,356 |

378,687 |

1,183,315 |

|

Percent of Total |

|||||||

|

Principal |

100% |

63% |

100% |

30% |

35% |

57% |

80% |

|

Derivative |

0% |

37% |

0% |

70% |

65% |

43% |

20% |

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Source: CRS presentation of data from 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 7, Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics.

Notes: USC refers to U.S. citizen. All Other Lawful Permanent Residents refer to employment-based immigrants, Diversity Visa Lottery immigrants, refugees and asylees.

Table 3 distinguishes principal from derivative immigrants for FY2016. Absolute numbers of principal qualifying immigrants made up 76% of total LPRs and 91% (not shown) of all family-based LPRs in that year. Differences appear by category with 3rd and 4th preference immigrants comprised of greater numbers of derivative than principal immigrants. Those categories contrast sharply with immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, and 1st and 2nd family preference category immigrants, where principal immigrants outnumber derivative immigrants. In comparison, all other (non-family) immigrants are more evenly divided between the two immigrant types.37

Child Immigrants

How the INA governs child immigrants depends on the child's age and marital status, as well as the citizenship status of the sponsoring U.S. relatives. The five family-sponsored categories described above distinguish between "minor children" under age 21, and adult "sons and daughters" age 21 and above, as well as between unmarried and married children. Within the five categories, the INA prioritizes minor over adult children, unmarried over married children, and children of U.S. citizens over children of LPRs.

In the two cases (immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and LPRs) where it is necessary to determine if the child is a minor, age varies by sponsorship category. For children sponsored as immediate relatives, age is determined based on when the I-130 petition was filed.38 For children sponsored under the 2nd family preference category, age is determined based on when an immigrant visa number becomes available, reduced by the amount of time (converted into years) that it took USCIS to process and approve the petition.39

Additionally, under current law, only adult U.S. citizens may sponsor their foreign-born parents as immediate relatives and their foreign-born siblings as 4th family preference immigrants.40 Foreign-born children under age 18 become naturalized U.S. citizens automatically upon admission to the United States if at least one parent is a U.S. citizen by birth or naturalization.41 Orphans adopted abroad by U.S. citizens must have been adopted by age 16 (with exceptions) to acquire automatic citizenship upon admission to the United States.42

Conditional Resident Status

Foreign national spouses of U.S. citizens and LPRs who acquire legal status through family-based provisions of the INA must have a two-year evaluation period for marriages of short duration (under two years at the time of sponsorship). Such foreign nationals receive conditional permanent residence status.43 This nonrenewable legal immigrant status, granted on the day the foreign national is admitted to the United States, is intended to help USCIS determine if such marriages are bona fide. During the two-year conditional period, USCIS may terminate the foreign national's conditional status if it determines that the marriage was entered into to evade U.S. immigration laws or was terminated other than through the death of the spouse.44

Within 90 days before the end of the two-year conditional period, the foreign national and his or her U.S.-based spouse must jointly petition to have the conditional status removed. If the petitioner and beneficiary fail to file the joint petition within the 90-day period, a waiver must be obtained to avoid loss of legal status. Assuming conditions in the law have been met and an interview with an appropriate immigration official uncovers no indication of marriage fraud, conditional permanent resident status converts to lawful permanent resident status.45

USCIS may waive the requirements noted above and remove an alien's conditional status in the following situations: (1) if the noncitizen spouse can show that he or she would suffer "extreme hardship" if deported from the United States; (2) if the conditional resident establishes that he or she entered into the marriage "in good faith," that the marriage was legally terminated, and that the noncitizen was "not at fault" in failing to meet the joint petition requirements; (3) if the alien spouse entered into the marriage in good faith but he or she or his or her child was battered or subjected to extreme cruelty by the citizen or resident spouse; or (4) if the noncitizen entered into the marriage in good faith that was subsequently deemed illegitimate because the U.S. citizen or LPR spouse engaged in bigamy.46 In all cases, USCIS reviews the legitimacy of the marriage prior to removing or waiving the condition.

Same-Sex Partners

The INA does not affirmatively define the terms "spouse,"47 "wife," or "husband." Previously, the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) declared that the terms "marriage" and "spouse," as used in federal enactments,48 excluded same-sex marriage.49 However, the Supreme Court's June 26, 2013 decision in United States v. Windsor struck down DOMA's provision defining "marriage" and "spouse" for federal purposes.50 DHS subsequently approved the first immigrant visa for the same-sex spouse of a U.S. citizen, and then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano directed USCIS to "review immigration visa petitions filed on behalf of a same-sex spouse in the same manner as those filed on behalf of an opposite-sex spouse."51 That policy remains in effect.

Profile of Legal Immigrants

Legal Immigration Trends

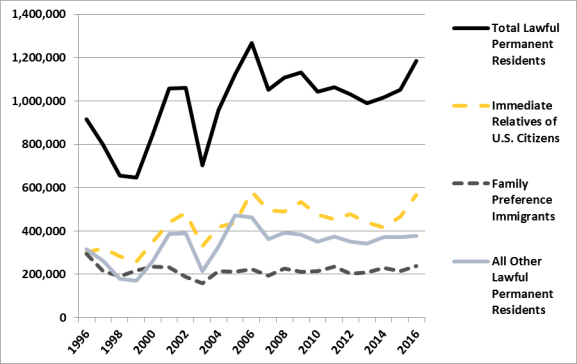

Immigration statistics for FY1996 through FY2016 reveal several trends among immigrants by category (Figure 1). First, total lawful permanent residents increased 29% over this period (with substantial fluctuations) from 915,900 in FY1996 to 1,183,505 in FY2016.52

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from the 2005, 2009, 2013, and 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 6, Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. Notes: All Other Lawful Permanent Residents refer to employment-based immigrants, diversity immigrants, refugees and asylees, and other immigrants. |

Second, the number of immediate relatives increased by 89% over this period, from 300,430 to 566,706, the largest increase of all family-based categories. Because annual family-sponsored preference immigrants are effectively capped at 226,000, immediate relatives—which are not numerically limited—accounted for the entire increase in total family-based immigration over this period.53 Increasing numbers of immigrants in other LPR categories explain why the proportion of family-based immigration to total immigration has remained constant at about two thirds over these two decades (66%). (For more data, see Table A-1, Table A-2, Table A-3, Table A-4, Table A-5, and Table A-6.)

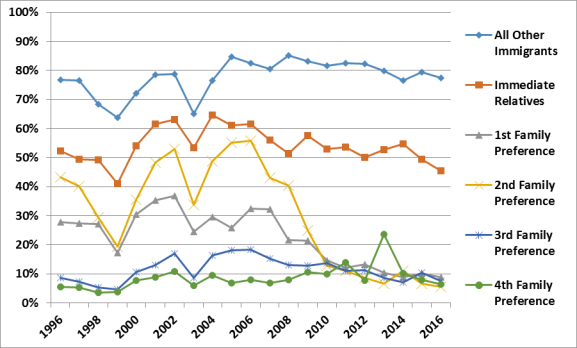

As noted in the section of this report titled, "Laws Governing the Immigration Process," individuals can become LPRs either by adjusting to LPR status if they currently reside in the United States, or by applying for LPR status from abroad. Figure 2 presents the percentage of LPRs who adjusted status by immigration category. As such, it represents the proportion of LPRs in each class category that was already residing in the United States at the time LPR status was granted. About half of all immediate relatives of U.S. citizens adjusted their status from within the United States over this period, while most family-based preference category immigrants, particularly in recent years, were admitted from abroad.54 In contrast, all other non-family-based immigrants mostly adjusted their status from within the United States.

Legislative and Policy Issues

Issues that are regularly raised in debates on family-based immigration policy include the supply-demand imbalance for U.S. lawful permanent residence, the per-country ceilings, limitations on foreign nationals who wish to visit U.S.-based relatives, the impetus to violate U.S. immigration laws, aging out of certain legal status categories, the marriage timing of immigrant children, and policies toward unaccompanied alien children.

Supply-Demand Imbalance for U.S. Lawful Permanent Residence

Each year, the number of foreign nationals petitioning for LPR status through family-sponsored preferences exceeds the number of immigrants that can be admitted to the United States according to current law. Consequently, a "visa queue" or waiting list has accumulated of persons who qualify as immigrants under the INA but who must wait for a visa to receive lawful permanent status. As such, the visa queue constitutes not a backlog of petitions to be processed but, rather, the number of persons approved for visas that are not yet available due to the numerical limits enumerated in the INA.

The most recent data available indicate that the visa queue of numerically limited family-preference immigrant petitions as of November 1, 2017, stood at 3.95 million applications (Table 4), a 7% decrease over the prior year's queue of 4.26 million.55 Within this population, queue size generally correlates inversely with preference category. For example, petitions filed under the (highest) 1st preference category (288,826) represent just 7% of the total queue while those filed under the (lowest) 4th preference category (2,344,993) make up 59% of the queue.

Waiting periods vary significantly depending on preference category and comprise both a statutory and a processing waiting period.56 Statutory limits to the number of visas given by category create waiting times that typically account for most of the waiting period. As noted, while U.S. immigration policy grants unlimited admission to immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, it limits annual immigration under the four family-sponsored preference categories to 226,000. The number of immigrants is also subject to the 7% per-country ceiling discussed above, which, for "over-subscribed" countries with relatively large numbers of LPR status petitions such as Mexico and China, increases visa waiting times substantially.

Table 4. Visa Queue of Prospective Family-Preference Immigrants with Approved Applications, for Selected Countries, as of November 1, 2017

|

Country |

Total Family Preference Prospective Immigrants |

1st Preference: Unmarried Sons & Daughters of USCs |

2nd (A) Preference: Spouses and Minor Children of LPRs |

2nd (B) Preference: Unmarried Sons and Daughters of LPRs |

3rd Preference: Married Sons & Daughters of USCs |

4th Preference: Siblings of USCs |

|

Mexico |

1,257,801 |

106,532 |

69,418 |

143,707 |

205,005 |

733,139 |

|

Philippines |

333,564 |

19,339 |

8,849 |

51,980 |

128,108 |

125,288 |

|

India |

282,207 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

51,259 |

223,476 |

|

Vietnam |

249,821 |

5,412 |

6,336 |

10,125 |

45,493 |

182,455 |

|

China |

202,503 |

n.a. |

6,937 |

8,142 |

23,416 |

161,093 |

|

Dominican Republic |

175,109 |

23,868 |

28,256 |

45,827 |

16,863 |

60,295 |

|

Bangladesh |

175,007 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

164,793 |

|

Pakistan |

121,752 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

15,037 |

101,387 |

|

Haiti |

104,085 |

15,674 |

7,275 |

16,194 |

15,863 |

49,079 |

|

El Salvador |

71,707 |

10,211 |

9,227 |

10,739 |

11,615 |

29,915 |

|

Jamaica |

n.a. |

14,268 |

n.a. |

4,886 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Colombia |

n.a. |

5,617 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Guyana |

n.a. |

5,206 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Honduras |

n.a. |

5,117 |

3,866 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Cuba |

n.a. |

n.a. |

11,757 |

9,012 |

14,502 |

n.a. |

|

Guatemala |

n.a. |

n.a. |

5,238 |

4,706 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

All Others |

974,301 |

77,582 |

56,571 |

59,035 |

208,794 |

514,073 |

|

Worldwide Total |

3,947,857 |

288,826 |

213,730 |

364,353 |

735,955 |

2,344,993 |

|

Percent of Total |

100% |

7% |

5% |

9% |

19% |

59% |

Source: Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2017, U.S. Department of State, National Visa Center.

Notes: USC refers to U.S. citizen, and LPR refers to lawful permanent resident. Figures include principal applicants and derivative spouse and child applicants. China refers to mainland-born. Because the National Visa Center (NVC) Annual Report lists the top countries for each category, some countries that appear as a top country in the visa queue for one immigrant category may not appear as a top country in another. In such cases, n.a. indicates the figure was not presented in the NVC report for the country and preference category.

The Visa Bulletin, a monthly update published online by DOS, illustrates how the visa queue translates into waiting times for immigrants (Table 5).57 DOS issues the numerically limited visas for family-sponsored preference categories according to computed cut-off dates. DOS adjusts these cut-off dates each month based on several variables, such as the number of visas used to that point, the projected demand for visas, and the number of visas remaining under the annual numerical limit for that country and/or preference category.58 Filing dates for qualified applicants are referred to as priority dates. Applicants with priority dates earlier than the cut-off dates in the Visa Bulletin are currently being processed.

Table 5. Cut-Off Dates for Family-Based Petitions, February 2018

(LPR petition filing dates for which immigration visas are available as of February 1, 2018)

|

Family Preference Category |

China |

India |

Mexico |

Philippines |

All Other Nations |

|

1st: Unmarried adult children of USCs |

3/15/2011 |

3/15/2011 |

7/1/1996 |

8/1/2005 |

3/15/2011 |

|

2nd (A): Spouses and children of LPRs |

3/1/2016 |

3/1/2016 |

2/1/2016 |

3/1/2016 |

3/1/2016 |

|

2nd (B): Unmarried adult children of LPRs |

1/15/2011 |

1/15/2011 |

9/8/1996 |

7/22/2006 |

1/15/2011 |

|

3rd: Married adult children of USCs |

11/15/2005 |

11/15/2005 |

6/22/1995 |

3/15/1995 |

11/15/2005 |

|

4th: Siblings of USCs |

7/22/2004 |

1/8/2004 |

11/8/1997 |

10/1/1994 |

7/22/2004 |

Source: Visa Bulletin for February 2018, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs.

Notes: USC refers to U.S. citizen and LPR refers to lawful permanent resident. China refers to mainland-born.

All family-preference category visas were oversubscribed as of February 1, 2018. Table 5 indicates, for example, that LPR petitions filed under the 1st family preference category (unmarried children of U.S. citizens) on or before March 15, 2011, were being processed close to seven years later for most countries. Countries that send many immigrants to the United States, such as China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines, currently have above-average waiting times. For instance, LPR petitions filed under the 1st family preference category for unmarried Filipino children that had been filed on or before August 1, 2005, were being processed on February 1, 2018, more than 12 years later.

The Visa Bulletin does not indicate how long current petitioners must wait to receive a visa, only how long they can expect to wait if current processing conditions continue into the future. However, visa processing rates vary for a variety of reasons, and changes in processing conditions can lead to visa retrogression, where dates are pushed back and petitioners have to wait longer, or visa progression, where dates advance forward and petitions are processed sooner. Visa retrogression occurs when more people apply for a visa in a particular category or country than there are visas available for that month. In contrast, visa progression occurs when fewer people apply.59 As each fiscal year closes (on September 30th), priority date progression or retrogression may occur to keep visa issuances within annual numerical limitations.60 Substantial increases in the rate at which family-based LPR petitions have been filed over the past two decades have extended actual waiting times for the most recent petitioners.61 Hence, while many interpret the cut-off dates as a rough estimate of waiting times to receive a visa, this interpretation may not always be accurate in certain situations for some categories.

While the visa queue reflects excess demand to immigrate permanently to the United States over the statutorily determined supply of slots, many criticize it for keeping families separated for what they view as excessive periods of time and for prompting actual and potential petitioners to subvert U.S. immigration policy through unauthorized or illegitimate means (see the section of this report, "Impetus to Violate Immigration Laws").62 Earlier debates over the visa queue are discussed in the section of this report titled, "Findings from Earlier Congressionally Mandated Commissions."

Assessing the Per-Country Ceiling

As noted, the INA establishes a per-country ceiling limiting total legal immigration from any single country for family-preference and employment-sponsored preference immigrants to 7% of the worldwide immigration level to the United States. Exceptions to this rule include the admission of all immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and 75% of all visas allocated to 2nd (A) preference category of spouses and children of LPRs.

The per-country ceiling especially restrains immigrants from countries with large numbers of LPR petitioners, such as Mexico, the Philippines, India, and China. Petitioners from these countries experience relatively longer average waiting times to receive a visa than petitioners from other countries (Table 5).

Proponents of the per-country ceiling assert that U.S. immigration policy has been more equitable and less discriminatory in terms of country of origin following passage of the Immigration Amendments of 1965. That act and its subsequent amendments, which ended the country-of-origin quota system favoring European immigrants, imposed worldwide and per-country limits on Western Hemisphere immigrants. Proponents also note the two major INA exceptions to the per-country ceilings—immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and 75% of 2nd (A) preference immigrants—that benefit oversubscribed countries such as Mexico, India, and China.63

Immigration reform advocates argue that family reunification should be prioritized over per-country ceilings, and cite the visa queue faced by prospective family-based LPRs from India, China, Mexico, and the Philippines. They assert that the current per-country ceilings are arbitrary and should be increased to enable families from all countries to reunite.64

Limitations on Visiting U.S. Relatives

Because U.S. immigration law presumes that all aliens seeking temporary admission to the United States wish to live here permanently, tourists and other temporary visitors must demonstrate their intent to return to their home countries.65 Consequently, aliens with pending LPR petitions (who intend to live permanently in the United States) as well as foreign nationals with U.S. citizen and LPR relatives, who wish to either tour the United States or visit their U.S.-based relatives, are often denied nonimmigrant visas to visit.66 The presumption of intention to immigrate is stated explicitly in Section 214(b) of the INA, and is the most common basis for rejecting nonimmigrant visa applicants.67

As an example, an adult unmarried Mexican daughter of U.S. citizen parents wishing to visit them on a tourist visa would likely face challenges to demonstrate that she possessed sufficient ties to Mexico to prevent her from staying in the United States. If denied a tourist visa, and having no occupational options available through employment-based immigration, her only alternative would be to apply for LPR status under the 1st family sponsored preference category, which, based on the cut-off dates shown in the latest Visa Bulletin (Table 5), could take roughly 21 years. During this period, she would be unable to visit her parents in the United States.

Impetus to Violate Immigration Laws

As noted, many foreign nationals with approved petitions to reside legally and permanently in the United States face extensive waiting times for obtaining a visa. As such, some have characterized current U.S. family-based immigration policy as promising what cannot be fulfilled within a reasonable period of time.68 Given the corresponding family separation that such wait times cause, some aliens who might otherwise abide by U.S. immigration laws may choose either to violate the terms of their temporary visas by "overstaying" in the United States or to enter the United States without inspection (i.e., illegally).69 However, the number of unauthorized aliens who reside in the United States specifically because their attempts to acquire LPR status within a reasonable period did not succeed is unknown.70 It is also not known how many unauthorized aliens have petitions pending and are therefore part of the 3.95 million family-based visa queue.71

Aging Out of Legal Status Categories

"Aging out" refers to the change in eligibility for a foreign national to receive an immigration benefit as they get older. It typically applies to children. In the case of family-based immigration, it is particularly noticeable because of the different treatment of minor children of U.S. citizens versus minor children of LPRs. Minor children of U.S. citizens are protected from aging out by the Child Status Protection Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-208), which provided them with durable status protection. That protection means that for immigration purposes, age is recorded as of the date an immigration petition was filed and remains in effect (or "freezes") regardless of the length of time needed to obtain lawful permanent residence.

In contrast, if minor children of LPRs who are sponsored under the 2(A) family preference category (see Table 1) turn 21 after a petition for lawful permanent residence has been filed on their behalf (but before they receive LPR status), they automatically "age out" of the 2(A) category and must be sponsored for immigration under the 2(B) category. This occurs because children of LPRs lack the durable status protection of immediate relative children of U.S. citizens. The net result of this 2(A) to 2(B) shift upon aging out is a substantially longer waiting time to obtain LPR status. The Visa Bulletin (Table 5) indicates that reclassification of 2(A) to 2(B) petitions currently extends the visa cut-off date and any attendant family separation by at least five years.72 (See also "Child Immigrants" above.)

Marriage Timing of Immigrant Children

Differential treatment for unmarried children under the 1st family preference category and married children under 3rd family preference categories may motivate potential LPR petitioners to delay marriage in order to receive more favorable immigration treatment under the INA. The INA prioritizes the former family preference category over the latter, a ranking that translates into a difference in visa cut-off dates of between one and four years, depending on the country of emigration (Table 5). This difference in cut-off dates occurs because unmarried children of U.S. citizens do not retain a durable marital status when they apply for LPR status under the 1st family preference category. Hence, the desire to remain in the 1st family preference category may motivate such petitioners to postpone marriage until their visas become available.

Unaccompanied Alien Children

The number of unaccompanied alien children (UAC) from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras seeking to enter the United States has increased substantially in recent years.73 In FY2014, total UAC apprehensions reached a peak of over 68,500 (up from 8,000 in FY2008). They have since fluctuated, and in the first three months of FY2018, they exceeded 11,000.74 Since FY2009, children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (Central America's "Northern Triangle") have accounted for almost all of the increased UAC apprehensions.

While policies addressing the surge in unaccompanied minors generally lie outside the scope of family-based immigration policy, the issue highlights the importance of family reunification as a key motivating factor for migrating to the United States.75 U.N. survey data indicate that sizable percentages of children residing in Northern Triangle countries have at least one parent living in the United States.76

Family reunification is a key feature of UAC processing in the United States. Upon apprehension, unaccompanied children are immediately put into removal proceedings. Yet, by law, persons apprehended by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and whom CBP determines to be unaccompanied children from countries other than Mexico and Canada must be turned over to the care and custody of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) while they await their removal hearing. ORR is required by statute to ensure that UACs "be promptly placed in the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child."77 In FY2017, an estimated 84% of children were placed with parents, legal guardians, and close relatives who resided in the United States.78

The desire for family reunification is also driven by the perception by potential migrants that children who are not immediately returned to their home countries can reside with their family members for periods extending several years. Many contend that the considerable length of time unaccompanied minors can expect to wait until their removal hearing contributes to incentivizing the migration.79

Complicating this situation is the fact that sizable proportions of these family members are estimated to be unauthorized aliens.80 According to the Pew Research Center, the estimated percent unauthorized of Salvadorans, Guatemalans, and Hondurans living in the United States in 2015 was 51%, 56%, and 60%.81

Broader Immigration Questions

Long-standing debates over the level of annual permanent immigration have regularly placed scrutiny on family-based immigration and revived debates over whether its current proportion of total lawful permanent immigration is appropriate. The following section discusses a set of broad immigration policy questions that have been raised by two congressionally mandated commissions as well as other observers.

Findings from Earlier Congressionally Mandated Commissions

Key reform proposals on a broad range of immigration policy challenges were made by two congressionally mandated commissions established to evaluate U.S. immigration policy: the 1981 Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy chaired by Theodore Hesburgh82 (the Hesburgh Commission) and the 1995 U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform chaired by Barbara Jordan83 (the Jordan Commission).

The Jordan Commission relied on findings of its predecessor.84 The Hesburgh Commission acknowledged that certain large-scale and relatively predictable demographic trends—fertility and mortality rates, for instance—could allow policymakers to formulate immigration policies around predetermined optimal population sizes.85 Although the United States has never had a policy specifying an appropriate population size for the nation, the Hesburgh Commission was aware of arguments for either increasing or decreasing immigration levels because of fiscal, cultural, environmental, and economic pressures, as well as for foreign policy objectives and national security.

Family reunification was cited by both the Hesburgh and the Jordon Commissions as the primary goal of U.S. immigration policy.86 The Jordan Commission rejected formulaic procedures for determining immigrant criteria, such as point systems, supporting instead the existing framework that allows U.S.-based relatives to decide whom to sponsor for immigration to the United States.87 The Hesburgh Commission, noting the imbalance between the demand for lawful permanent U.S. residence and visa supply, asserted that "raising false hopes among millions with no prospect of immigration" would foster unauthorized immigration and "widespread dissatisfaction with U.S. immigration laws."88 Both commissions considered options for reconfiguring family-based categories, typically favoring spouses and minor children over other relatives, and the relatives of U.S. citizens over those of LPRs.

The Hesburgh Commission recommended eliminating the 4th family preference category, siblings of U.S. citizens.89 The Jordan Commission went farther, recommending the elimination of what are currently the 1st, 3rd, and 4th family preference categories, thereby allowing only spouses, minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens (immediate relatives), and spouses and minor children of LPRs (2A preference category) as family-sponsored preference immigrants.90 Justifications for these revisions included reunifying U.S. citizens and LPRs with their closest and most dependent relations, reducing unreasonably long visa wait times, and improving the credibility of the immigration system while eliminating false expectations of prompt U.S. permanent resident status for more distant relatives of U.S. citizens and LPRs.

The Hesburgh Commission recommended more flexible family-based immigration numerical limits. For instance, it suggested establishing two numerical targets, one annual, and another for a longer term, such as five years. This would allow annual immigration to vary, possibly within an established range, accommodating unpredictable situations such as domestic concerns or international conditions while maintaining a long-term ceiling. Another option suggested by the Hesburgh Commission would permit borrowing between ceilings for subcategories (family, employment, refugee) to accommodate such situations.

In a 2013 hearing on the American immigration system, Dr. Michael Teitelbaum, commissioner and vice chair of the former U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform (Jordan Commission), testified before the House Judiciary Committee.91 Six weeks later, Dr. Susan Martin, former executive director of the Jordan Commission, testified at a hearing on comprehensive immigration reform before the Senate Judiciary Committee.92 During their presentations, Teitelbaum and Martin both reiterated recommendations from the Jordan Commission's 1995 and 1997 reports. Their testimony, occurring 15 years after the commission completed its assessment of U.S. immigration policy, underscored the continued relevance of past congressional debates on current issues surrounding family-based immigration.

Family Reunification versus Family Reconstitution

As noted, the INA allows LPRs and U.S. citizens to sponsor spouses and unmarried children. U.S. citizens, in addition, may sponsor parents, married adult children, and siblings. The INA, however, does not permit either U.S. citizens or LPRs to sponsor other relatives such as grandparents, grandchildren, cousins, aunts, and uncles.

Some supporters of current law argue that parents and children should be considered immediate family members regardless of their age or marital status.93 They contend that siblings are considered immediate relatives in many cultures.94 A central argument for expanding family-based immigration is to reduce the current visa queue of roughly 4 million persons with approved immigration petitions who must wait years to receive a visa to immigrate. As highlighted by Visa Bulletin cut-off dates (Table 5), family separation can last for years or even decades, which some contend keeps families and individual lives and careers suspended and causes considerable emotional and psychological distress.95

Advocates of lower immigration levels take issue with broadening family reunification.96 While they accept that family reunification is an important goal, they argue that the United States has neither the responsibility nor obligation to effectively reconstitute immigrants' families beyond immediate relatives.97 They assert that U.S. immigration policy is currently among the most generous in the world and would continue to be so even if legal immigration were substantially curtailed.98 Those favoring limiting family-based preference immigration to just immediate family members (i.e., spouses and minor unmarried children) note that the Jordan Commission recommended this limitation in 1995.99

Family Reunification versus Economic Priorities

Some observers fault U.S. immigration policy for operating largely irrespective of current economic and labor market conditions.100 Because current family-based immigration provisions do not require minimum education or skill requirements, they arguably do not yield optimal labor market benefits for the United States.101 Critics also contend that current policies foster greater demand for taxpayer-funded social services102 by admitting relatively less-educated persons who frequently work in lower-paid occupations or who have higher unemployment rates.103

Although critics argue that family-based immigration policies do not adjust for changing labor market requirements in specific industries and for specific occupations, others cite evidence of their positive impact on long-term employment needs. Studies suggest that while employment-based immigrants serve short-term labor market needs, family-based immigrants serve such needs more effectively over the long term.104 A related argument posits that the skills of immigrants entering the United States under the current immigration system match those required of the future workforce more accurately than some suggest.105 The foreign born also work in certain occupations, such as health care with above-average expected growth.106 Some cite these trends to argue that current immigration policies admit people whose occupational and sectoral employment profiles match projected demands of the U.S. economy. Apart from skill levels, demographically, the foreign-born population in recent decades has contributed almost all the growth in the working age population.107

Proponents of family-based immigration also argue that family reunification in the United States helps U.S. immigrants contribute more to their communities and the U.S. economy through improved productivity, health, and emotional support.108 Similarly, proponents of the 4th family preference siblings category, which the Jordan Commission recommended eliminating, argue that immigrant siblings are often involved with entrepreneurial enterprises and family businesses, a traditional immigrant pathway to economic mobility and a source for economic revitalization in disadvantaged urban and rural areas.109

"Chain Migration"

"Chain migration" is a term some have used to characterize the process by which family-based immigration can create self-perpetuating and expanding migration flows, as foreign nationals who obtain lawful permanent resident status and citizenship then sponsor other relatives under the family-based immigration provisions. As noted, while immigrants sponsored under the four family preference categories face numerical limits as well as a per-country ceiling, immediate relatives of U.S. citizens are admitted without numerical restriction of either type. Some have likened the potential for immigrant population growth under current policy to a genealogical table, where a new "link" of an immigrant chain is formed each time an admitted immigrant sponsors a new family-related immigrant who then may do the same for another new immigrant.110 Critics of family-based immigration policy argue that such processes could potentially generate hundreds of new immigrants from a single LPR.111 Theodore Hesburgh, chair of the U.S. Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy, offered the following illustration in 1981:

Assume one foreign-born married couple, both naturalized, each with two siblings who are also married and each new nuclear family having three children. The foreign-born married couple may petition for the admission of their siblings. Each has a spouse and three children who come with their parents. Each spouse is a potential source for more immigration, and so it goes. It is possible that no less than 84 persons would become eligible for visas in a relatively short period of time.112

Although family-based immigration could hypothetically generate such large impacts, empirical studies of actual "immigrant multipliers"113 estimate more modest effects.114 Carr and Tienda have produced several empirically rigorous analyses estimating multipliers for recent cohorts of immigrants. In one, they examined persons who acquired LPR status from 1980 to 2000, deriving a separate multiplier for each of the four five-year intervals across the two decades.115 That analysis yielded an immigration multiplier of 3.46 for the period from 1996 to 2000, meaning that, on average, every 100 initial immigrants who acquired LPR status during that period subsequently sponsored 346 new immigrants. Because this multiplier covers the most recent 5-year period of the four computed across a 20-year analysis, it is considered more relevant for current analyses of chain migration and has been widely cited by other policy analysts in discussions of chain migration.116 In a subsequent analysis, Tienda estimated separate multipliers for immigrants from China (6.24), India (5.11), the Philippines (6.38), and Mexico (5.07) for the same five-year period.117

Several factors may limit the impact of chain migration. First, with the exception of the 2nd family preference category, family-sponsored immigration requires that sponsoring immigrants possess U.S. citizenship. Recent studies indicate that many LPRs who are eligible to become U.S. citizens choose not to do so.118 Second, not all persons eligible to immigrate to the United States wish to do so. Both decisions—to naturalize for U.S.-based LPRs and to emigrate for relatives overseas—are affected by an array of individual-level characteristics and macro-level conditions in both the United States and the origin country. Consequently, estimates of multipliers are likely to vary substantially by country and period considered.119 Finally, as discussed above, long wait times for visas pose an impediment for many immigrants sponsoring relatives under the family-preference categories.120

Selected Legislative Activity

Legislative options to address selected stand-alone policy issues surrounding family-based immigration—the supply-demand imbalance for U.S. lawful permanent residence, the per-country ceilings, limitations on foreign nationals who wish to visit U.S.-based relatives, the impetus to violate U.S. immigration laws, aging out of certain legal status categories, the marriage timing of immigrant children, and policies toward unaccompanied alien children—have been debated by scholars and policymakers as well as addressed in a range of legislative proposals.

A broader policy question, in the context of current immigration debates, may be whether and how to address overall levels of legal immigration. Options at this level can generally be characterized as expanding, contracting, or revising family-based immigration. Such options revolve around classifying family categories as numerically limited or unlimited, decreasing or increasing current numerical limits, expanding or reducing the number of family preference categories, revising priorities among the different family-based categories, and using different selection procedures and criteria for admitting lawful permanent residents.

Examples of recent legislative proposals that focus on altering the level of permanent immigration include S. 744, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act introduced in the 113th Congress121 and S. 1720, the Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy (RAISE) Act introduced in the 115th Congress.122

S. 744, which passed the Senate in the 113th Congress, would have, among other things, reclassified spouses and minor unmarried children of LPRs as immediate relatives, thus exempting them from family preference numerical limits. It would have reallocated family preference visas and eliminated the 4th family preference category for adult siblings of U.S. citizens. The bill would have also provided additional visas to allow pending immigrants in the immigrant visa queue to all receive LPR status within seven years.123 In contrast, the RAISE Act would reduce the number of immediate relative and family preference category immigrants within family-sponsored immigration and eliminate the immigrant visa queue by invalidating most pending immigrant petitions.124

These two proposals are not the only approaches being considered to address levels of permanent immigration but they illustrate alternative perspectives on the goals of U.S. immigration policy from which these proposals arise.

Appendix. Immigration Figures for FY1996-FY2016

|

FY2006 |

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

|

Immediate relatives |

580,348 |

494,920 |

488,483 |

535,554 |

476,414 |

453,158 |

478,780 |

439,460 |

416,456 |

465,068 |

566,706 |

|

Spouses |

339,843 |

274,358 |

265,671 |

317,129 |

271,909 |

258,320 |

273,429 |

248,332 |

238,852 |

265,367 |

304,358 |

|

Children |

120,064 |

103,828 |

101,342 |

98,270 |

88,297 |

80,311 |

81,121 |

71,382 |

61,217 |

66,740 |

88,494 |

|

Parents |

120,441 |

116,734 |

121,470 |

120,155 |

116,208 |

114,527 |

124,230 |

119,746 |

116,387 |

132,961 |

173,854 |

|

Family-preference |

222,229 |

194,900 |

227,761 |

211,859 |

214,589 |

234,931 |

202,019 |

210,303 |

229,104 |

213,910 |

238,087 |

|

Unmarried adult children of USCs |

25,432 |

22,858 |

26,173 |

23,965 |

26,998 |

27,299 |

20,660 |

24,358 |

25,686 |

24,533 |

22,072 |

|

Spouses & unmarried children of LPRs |

112,051 |

86,151 |

103,456 |

98,567 |

92,088 |

108,618 |

99,709 |

99,115 |

105,641 |

104,892 |

121,267 |

|

Married adult children of USCs |

21,491 |

20,611 |

29,273 |

25,930 |

32,817 |

27,704 |

21,752 |

21,294 |

25,830 |

24,271 |

27,392 |

|

Siblings of USCs |

63,255 |

65,280 |

68,859 |

63,397 |

62,686 |

71,310 |

59,898 |

65,536 |

71,947 |

60,214 |

67,356 |

|

Non-family-based |

463,552 |

362,595 |

390,882 |

383,405 |

351,622 |

373,951 |

350,832 |

340,790 |

370,958 |

372,053 |

378,712 |

|

Employment-based immigrants |

159,081 |

162,176 |

166,511 |

144,034 |

148,343 |

139,339 |

143,998 |

161,110 |

151,596 |

144,047 |

137,893 |

|

Diversity Visa Lottery immigrants |

44,471 |

42,127 |

41,761 |

47,879 |

49,763 |

50,103 |

40,320 |

45,618 |

53,490 |

47,934 |

49,865 |

|

Refugees, asylees, and parolees |

221,023 |

138,124 |

167,564 |

179,753 |

137,883 |

169,607 |

151,372 |

120,186 |

134,337 |

152,018 |

157,440 |

|

All other immigrants |

38,977 |

20,168 |

15,046 |

11,739 |

15,633 |

14,902 |

15,142 |

13,876 |

31,535 |

28,054 |

33,514 |

|

Total, all immigrants |

1,266,129 |

1,052,415 |

1,107,126 |

1,130,818 |

1,042,625 |

1,062,040 |

1,031,631 |

990,553 |

1,016,518 |

1,051,031 |

1,183,505 |

Source: CRS presentation of data from 2005 through 2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Table 6, Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics.

Notes: Italicized figures sum up to bold figures immediately above them. USC refers to U.S. citizen; LPR refers to lawful permanent resident.

|

FY1996 |

FY1997 |

FY1998 |

FY1999 |

FY2000 |

FY2001 |

FY2002 |

FY2003 |

FY2004 |

FY2005 |

||

|

Immediate relatives |

300,430 |

321,008 |

283,368 |

258,584 |

346,350 |

439,972 |

483,676 |

331,286 |

417,815 |

436,115 |

|

|

Spouses |

169,760 |

170,263 |

151,172 |

127,988 |

196,405 |

268,294 |

293,219 |

183,796 |

252,193 |

259,144 |

|

|

Children |

63,971 |

76,631 |

70,472 |

69,113 |

82,638 |

91,275 |

96,941 |

77,948 |

88,088 |

94,858 |

|

|

Parents |

66,699 |

74,114 |

61,724 |

61,483 |

67,307 |

80,403 |

93,516 |

69,542 |

77,534 |

82,113 |

|

|

Family-preference |

294,174 |

213,331 |

191,480 |

216,883 |

235,092 |

231,699 |

186,880 |

158,796 |

214,355 |

212,970 |

|

|

Unmarried adult children of USCs |

20,909 |

22,536 |

17,717 |

22,392 |

27,635 |

27,003 |

23,517 |

21,471 |

26,380 |

24,729 |

|

|

Spouses & unmarried children of LPRs |

182,834 |

113,681 |

88,488 |

108,007 |

124,540 |

112,015 |

84,785 |

53,195 |

93,609 |

100,139 |

|

|

Married adult children of USCs |

25,452 |

21,943 |

22,257 |

24,040 |

22,804 |

24,830 |

21,041 |

27,287 |

28,695 |

22,953 |

|

|

Siblings of USCs |

64,979 |

55,171 |

63,018 |

62,444 |

60,113 |

67,851 |

57,537 |

56,843 |

65,671 |

65,149 |

|

|

Non-family-based |

321,296 |

264,039 |

179,603 |

171,101 |

259,560 |

387,231 |

388,800 |

213,460 |

325,713 |

473,172 |

|

|

Employment-based immigrants |

117,499 |

90,607 |

77,517 |

56,817 |

106,642 |

178,702 |

173,814 |

81,727 |

155,330 |

246,877 |

|

|

Diversity Visa Lottery immigrants |

58,790 |

49,374 |

45,499 |

47,571 |

50,920 |

41,989 |

42,820 |

46,335 |

50,084 |

46,234 |

|

|

Refugees, asylees, and parolees |

130,834 |

114,022 |

53,482 |

44,784 |

66,090 |

113,330 |

131,816 |

48,960 |

78,351 |

150,677 |

|

|

All other immigrants |

14,173 |

10,036 |

3,105 |

21,929 |

35,908 |

53,210 |

40,350 |

36,438 |

41,948 |

29,384 |

|

|

Total, all immigrants |

915,900 |

798,378 |

654,451 |

646,568 |

841,002 |

1,058,902 |

1,059,356 |

703,542 |

957,883 |

1,122,257 |

Table A-3. Percentages of Annual Lawful Permanent Residents by Major Class, FY2006-FY2016

(Percent of total immigration)

|

FY2006 |

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

|

Immediate relatives |