Numerical Limits on Permanent Employment-Based Immigration: Analysis of the Per-country Ceilings

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specifies a complex set of numerical limits and preference categories for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs) that include economic priorities among the criteria for admission. Employment-based immigrants are admitted into the United States through one of the five available employment-based preference categories. Each preference category has its own eligibility criteria and numerical limits, and at times different application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 visas annually for employment-based LPRs, which amount to roughly 14% of the total 1.0 million LPRs in FY2014. The INA further specifies that each year, countries are held to a numerical limit of 7% of the worldwide level of LPR admissions, known as per-country limits or country caps.

Some employers assert that they continue to need the “best and the brightest” workers, regardless of their country of birth, to remain competitive in a worldwide market and to keep their firms in the United States. While support for the option of increasing employment-based immigration may be dampened by economic conditions, proponents argue it is an essential ingredient for economic growth. Those opposing increases in employment-based LPRs assert that there is no compelling evidence of labor shortages and cite the rate of unemployment across various occupations and labor markets.

With this economic and political backdrop, the option of lifting the per-country caps on employment-based LPRs has become increasingly popular. Some argue that the elimination of the per-country caps would increase the flow of high-skilled immigrants without increasing the total annual admission of employment-based LPRs. The presumption is that many high-skilled people (proponents cite those from India and China, in particular) would then move closer to the head of the line to become LPRs.

To explore this policy option, analyses of approved pending employment-based petitions are performed on two different sets of data: approved pending petitions with the Department of State (DOS) National Visa Center (NVC), and approved pending petitions with U.S. Citizenship and Immigrant Services (USCIS). Because DOS and USCIS play different roles in the visa application process, their datasets represent different populations. DOS’s data from the NVC contains individuals who apply for a visa while residing outside of the United States. They are considered new arrivals once they are issued a visa and enter the United States. USCIS’s data contains individuals who are already residing in the United States and are applying to change their immigration status from a temporary status to a permanent LPR visa. This process is referred to as an adjustment of status.

As of November 2015, there were 100,747 approved employment-based LPR petitions pending at the National Visa Center. The 3rd preference category of “professional, skilled, and unskilled” workers had the highest number of pending approved petitions (67,792). The 5th preference category of “immigrant investors” had 17,662 approved petitions pending and the 2nd preference category of “advanced degree” workers had 11,400 approved petitions pending. There were also 3,747 approved petitions pending for the 1st preference category of “extraordinary” workers and 379 for the 4th preference category for “special immigrants.”

In terms of the USCIS data, there were a total of 117,731 approved I-485 petitions pending as of April 2016, and most were for the 2nd preference “advanced degree” workers (46,765). There were 37,971 approved I-485 petitions pending in the 3rd preference “professional, skilled, and unskilled” category and 30,457 pending in the 1st preference “extraordinary” category. In addition, there were 1,409 5th preference “immigrant investor” and 1,129 4th preference “special immigrant” approved I-485 petitions pending.

The top four countries in the National Visa Center data set were (in descending rank order) India, the Philippines, China, and South Korea. The top four countries in the USCIS data sets were (in descending rank order) India, China, the Philippines, and Mexico. The data indicates that more Indians and Mexicans are waiting to adjust status in the United States, while more Filipinos and Chinese are waiting to immigrate from abroad.

Some argue that the per-country ceilings are arbitrary and observe that employability has nothing to do with country of birth. Others maintain that the statutory per-country ceilings restrain the dominance of high-demand countries and preserve the diversity of immigrant flows.

Numerical Limits on Permanent Employment-Based Immigration: Analysis of the Per-country Ceilings

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background on Numerical Limits

- Employment-Based Immigrants

- Per-country Ceiling

- Admission Trends

- New Arrivals Versus Adjustments of Status

- Employment-Based Priority Dates for August 2016

- New Arrivals: Approved Visa Petitions Pending at the NVC

- Adjustment of Status: Approved I-485 Petitions Pending

- Comparative Summation

- Legislative and Policy Issues

- Changing Per-country Limits

- Possible Alternatives to Revising the Country Caps

- Statistical Projections Elusive

- Summary of Arguments in Debate

Figures

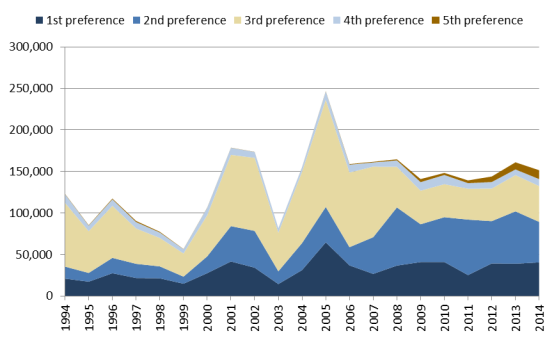

- Figure 1. Permanent Employment-Based Admissions, by Preferences, 1994-2014

- Figure 2. Newly Arriving and Adjusting Employment-Based Principals

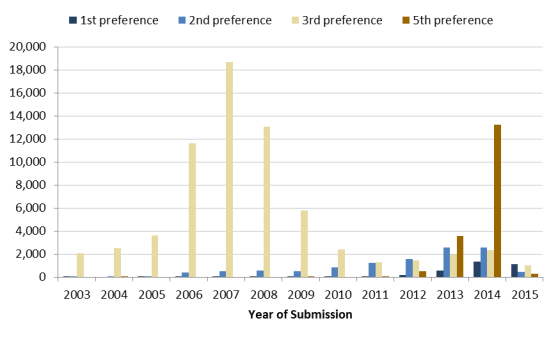

- Figure 3. Approved Employment-Based Visa Petitions Pending as of November 2015, by Date of Submission and Preference Category

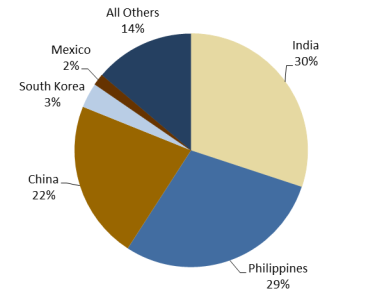

- Figure 4. Approved Employment-Based Visa Petitions Pending as of November 2015, by Top Countries

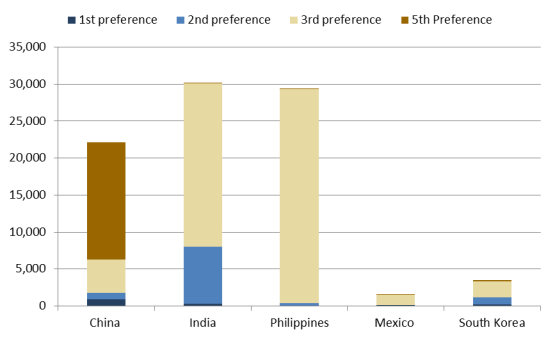

- Figure 5. Approved Employment-based Visa Petitions Pending as of November 2015, by Preference and Top Countries

- Figure 6. Approved Employment-Based I-485 Petitions Pending as of April 2016, by Date of Submission and Select Preference Categories

- Figure 7. Approved Employment-Based I-485 Petitions Pending as of April 2016, by Top Countries

- Figure 8. Approved Employment-Based I-485 Petitions Pending as of April 2016, by Preference and Top Countries

- Figure 9. Top Countries with Approved Visa or I-485 Petitions Pending

Tables

- Table 1. Employment-Based Immigration Preference System

- Table 2. Priority Dates for Employment Preference Visas for August 2016

- Table 3. Employment-Based Pending Petitions

- Table A-1. Approved Employment-Based Petitions Pending as of November 2015, by Top Countries

- Table A-2. Approved Employment-Based I-485 Petitions Pending as of April 2016 by Select Countries

Summary

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) specifies a complex set of numerical limits and preference categories for admitting lawful permanent residents (LPRs) that include economic priorities among the criteria for admission. Employment-based immigrants are admitted into the United States through one of the five available employment-based preference categories. Each preference category has its own eligibility criteria and numerical limits, and at times different application processes. The INA allocates 140,000 visas annually for employment-based LPRs, which amount to roughly 14% of the total 1.0 million LPRs in FY2014. The INA further specifies that each year, countries are held to a numerical limit of 7% of the worldwide level of LPR admissions, known as per-country limits or country caps.

Some employers assert that they continue to need the "best and the brightest" workers, regardless of their country of birth, to remain competitive in a worldwide market and to keep their firms in the United States. While support for the option of increasing employment-based immigration may be dampened by economic conditions, proponents argue it is an essential ingredient for economic growth. Those opposing increases in employment-based LPRs assert that there is no compelling evidence of labor shortages and cite the rate of unemployment across various occupations and labor markets.

With this economic and political backdrop, the option of lifting the per-country caps on employment-based LPRs has become increasingly popular. Some argue that the elimination of the per-country caps would increase the flow of high-skilled immigrants without increasing the total annual admission of employment-based LPRs. The presumption is that many high-skilled people (proponents cite those from India and China, in particular) would then move closer to the head of the line to become LPRs.

To explore this policy option, analyses of approved pending employment-based petitions are performed on two different sets of data: approved pending petitions with the Department of State (DOS) National Visa Center (NVC), and approved pending petitions with U.S. Citizenship and Immigrant Services (USCIS). Because DOS and USCIS play different roles in the visa application process, their datasets represent different populations. DOS's data from the NVC contains individuals who apply for a visa while residing outside of the United States. They are considered new arrivals once they are issued a visa and enter the United States. USCIS's data contains individuals who are already residing in the United States and are applying to change their immigration status from a temporary status to a permanent LPR visa. This process is referred to as an adjustment of status.

As of November 2015, there were 100,747 approved employment-based LPR petitions pending at the National Visa Center. The 3rd preference category of "professional, skilled, and unskilled" workers had the highest number of pending approved petitions (67,792). The 5th preference category of "immigrant investors" had 17,662 approved petitions pending and the 2nd preference category of "advanced degree" workers had 11,400 approved petitions pending. There were also 3,747 approved petitions pending for the 1st preference category of "extraordinary" workers and 379 for the 4th preference category for "special immigrants."

In terms of the USCIS data, there were a total of 117,731 approved I-485 petitions pending as of April 2016, and most were for the 2nd preference "advanced degree" workers (46,765). There were 37,971 approved I-485 petitions pending in the 3rd preference "professional, skilled, and unskilled" category and 30,457 pending in the 1st preference "extraordinary" category. In addition, there were 1,409 5th preference "immigrant investor" and 1,129 4th preference "special immigrant" approved I-485 petitions pending.

The top four countries in the National Visa Center data set were (in descending rank order) India, the Philippines, China, and South Korea. The top four countries in the USCIS data sets were (in descending rank order) India, China, the Philippines, and Mexico. The data indicates that more Indians and Mexicans are waiting to adjust status in the United States, while more Filipinos and Chinese are waiting to immigrate from abroad.

Some argue that the per-country ceilings are arbitrary and observe that employability has nothing to do with country of birth. Others maintain that the statutory per-country ceilings restrain the dominance of high-demand countries and preserve the diversity of immigrant flows.

Introduction

Four major principles currently underlie U.S. policy on legal permanent immigration: the reunification of families, the admission of legal permanent residents (LPRs)1 with needed skills, the protection of refugees, and the diversity of admissions by country of origin.2 These principles are embodied in federal law, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) first codified in 1952. The Immigration Amendments of 1965 replaced the national origins quota system (enacted after World War I) with per-country ceilings. The Immigration Act of 1990 was the last law to significantly revise the statutory provisions on employment-based permanent immigration to the United States.3

Currently, permanent immigrants (or LPRs) enter the United States based on a preference system. Nonimmigrants, who are admitted into the United States temporarily, are not admitted through this preference system. There are five preference categories for employment-based LPRs and each has its own eligibility requirements and numerical limitations, and at times different application processes. Per-country ceilings are an additional numerical limitation placed on permanent immigration in order to prevent any one country from taking too large of a share of the visas.

Interest has grown in the per-country ceilings, which limit the number of employment-based LPRs coming from specific countries each year. While no one is arguing for a return to the country-of-origin quota system that was the law from 1921 to 1965, some assert that the current numerical limits on employment-based LPRs are not working in the national interest. To inform this debate, this report analyzes the impact of the per-country ceilings on the employment-based immigration process.

The Departments of State (DOS) and Homeland Security (DHS) each play key roles in administering the law and policies on the admission of migrants. Although DOS Consular Affairs is responsible for issuing visas, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigrant Services (USCIS) in DHS must first approve immigrant petitions. DOS is responsible for the allocation, enumeration, and assignment of all visas. In addition, the Department of Labor (DOL) is responsible for ensuring that employers seeking to hire employment-based LPRs are approved to do so. The prospective immigrant must maneuver this course through these federal departments and agencies to obtain LPR status.

The report opens with brief explanations of the employment-based preference categories and the per-country ceilings governing annual admissions of LPRs. The focus is on the five major employment-based preference categories. The report continues with a statistical analysis of the pending caseload of approved employment-based LPR petitions. The same analyses of approved pending employment-based petitions are performed on two different sets of data: approved pending petitions with the DOS National Visa Center; and approved pending petitions with USCIS, known by the petition number as the I-485 Inventory. The report concludes with a set of legislative options to revise per-country ceilings that are meant to serve as springboards for further discussions.

Background on Numerical Limits

The INA provides for a permanent annual worldwide level of 675,000 LPRs, which is further broken down by specific levels for each preference category.4 However, the worldwide level is flexible and certain categories of LPRs are permitted to exceed the limits.5 The permanent worldwide immigrant level consists of the following components: family-sponsored immigrants,6 including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens and family-sponsored preference immigrants (480,000 plus certain unused employment-based preference numbers from the prior year); employment-based immigrants (140,000 plus certain unused family preference numbers from the prior year); and diversity immigrants (55,000). Immediate relatives7 of U.S. citizens as well as refugees and asylees who are adjusting to LPR status are exempt from direct numerical limits.8 As a result, roughly 1 million LPRs are admitted or adjusted annually.

In addition to preference category numerical limitations, the INA specifies that each year countries are held to a numerical limit of 7% of the worldwide level of U.S. immigrant admissions, known as per-country limits or country caps.9 The actual number of immigrants that may be approved from a given country, however, is not a simple percentage calculation, as certain types of LPRs (such as immediate relatives) are exempt from the country caps.

Employment-Based Immigrants

Employment-based immigrant visas (and family-sponsored visas) are issued to eligible immigrants in the order in which petitions have been filed under that specific preference category for that specific country.10 Spouses and children of prospective LPRs are entitled to the same status, and the same order of consideration as the person qualifying as the principal LPR, if accompanying or following to join the LPR (referred to as derivative status). When visa demand exceeds the per-country limit, visas are prorated according to the preference system allocations (detailed in Table 1) for the oversubscribed foreign state or dependent area.

|

Category |

Numerical limit |

||

|

Employment-Based Preference Immigrants |

Worldwide Level 140,000 |

||

|

1st preference— |

Priority workers: persons of extraordinary ability in the arts, science, education, business, or athletics; outstanding professors and researchers; and certain multinational executives and managers |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 4th and 5th preference |

|

|

2nd preference— |

Members of the professions holding advanced degrees or persons of exceptional abilities in the sciences, art, or business |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 1st preference |

|

|

3rd preference— |

Skilled shortage workers with at least two years training or experience; professionals with baccalaureate degrees and unskilled shortage workers. |

28.6% of worldwide limit (40,040) plus unused 1st or 2nd preference; unskilled workers limited to 10,000 |

|

|

4th preference— |

"Special immigrants," including ministers of religion, religious workers other than ministers, certain employees of the U.S. government abroad, and others |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); religious workers limited to 5,000 |

|

|

5th preference— |

Immigrant investors who invest at least $1 million (amount may vary in rural areas or areas of high unemployment) in a new commercial enterprise that will create at least 10 new jobs |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940); 3,000 minimum reserved for investors in rural or high unemployment areas |

|

Source: CRS summary of §§203(a), 203(b), and 204 of INA; 8 U.S.C. §1153.

Note: Employment-based allocations are further affected by §203(e) of the Nicaraguan and Central American Relief Act (NACARA), as amended by §1(e) of P.L. 105-139. This provision states that the employment 3rd preference "other worker" allocation is to be reduced by up to 5,000 annually for as long as necessary to offset adjustments under NACARA.

The INA bars the admission of any migrant who seeks to enter as a 2nd or 3rd preference LPR to perform skilled or unskilled labor, unless it is determined that (1) there are not sufficient U.S. workers who are able, willing, qualified, and available; and (2) the employment of the migrant will not adversely affect the wages and working conditions of similarly employed workers in the United States.11 The foreign labor certification program in the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) is responsible for ensuring that foreign workers do not displace or adversely affect wages or working conditions of U.S. workers.12 Therefore, employers applying for foreign workers under the 2nd and 3rd preference categories must first get a foreign labor certification from DOL before filing a visa petition with USCIS.

Per-country Ceiling

As mentioned previously, the INA establishes per-country levels, or country caps, at 7% of the worldwide level.13 The annual worldwide level for permanent immigration is 675,000 LPRs.14 For a dependent foreign state, the per-country ceiling is 2%.15 The per-country level is not a "quota" set aside for individual countries, as each country in the world could not receive 7% of the overall limit. As the State Department describes it, the per-country level "is not an entitlement but a barrier against monopolization."

In addition to being a worldwide ceiling of 7% per country, the 7% per-country ceiling applies within the family-based preference system and did apply within the employment-based preference system prior to FY2001. The American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-313) enabled the per-country ceilings for employment-based immigrants to be surpassed for individual countries that are oversubscribed as long as visas are available within the worldwide limit for employment-based preferences. Employment-based preference allocations may exceed the 7% per-country limit within the overall level of 140,000 annually.

Admission Trends

The total number of employment-based LPR admissions notably increased from 123,291 in FY1994 to 246,865 in FY2005.16 Employment-based LPRs dipped to 140,903 in 2009 and rose to 151,596 in FY2014. They comprised 15% of the total 1,016,518 LPRs in FY2014.17 As noted in Table 1 above, the INA allocates the bulk of the employment-based visas—almost 86%—to the 1st through 3rd preference categories.

Figure 1 presents the trends from 1994 to 2014 by preferences.18 Over this period, the 1st preference LPRs have increased by 93% and the 2nd preference LPRs have increased by more than 200%. The admission of 3rd preference "professional, skilled, and unskilled workers" and 4th preference "special immigrants" has dropped by 44% and 20% from FY1994 through FY2014, respectively. With respect to the 5th preference, from FY1994 to FY2014, admissions increased by more than twenty-fold (from 444 to 10,723).

New Arrivals Versus Adjustments of Status

Petitions for employment-based LPR status are first filed with USCIS in DHS by the sponsoring employer in the United States or, in some cases, the individual can self-petition. Petitions are sent to the National Visa Center (NVC) at DOS and individuals are assigned a priority date which represents their place in line. Individuals must then wait for their priority date to become current before they can proceed to the next steps.19

Once an individual's priority date becomes current, the next steps they take will depend on whether they are already in the United States or are abroad. If the prospective immigrant is already residing in the United States, the individual must apply for an adjustment of status (with Form I-485), which involves the individual, who is currently in the country, switching from a temporary category (e.g., an individual with an F-1 student temporary visa) to a permanent category. USCIS handles the processing of applications for adjustment of status.20

If the prospective LPR does not have legal residence status in the United States or is living abroad, the National Visa Center will handle the processing of the petition and will then forward the petition to the DOS Bureau of Consular Affairs in the applicant's home country. Regardless of whether the potential LPR is adjusting status with USCIS in the United States or obtaining a visa abroad from Consular Affairs, DOS assigns the visa priority dates and allocates the visa numbers.

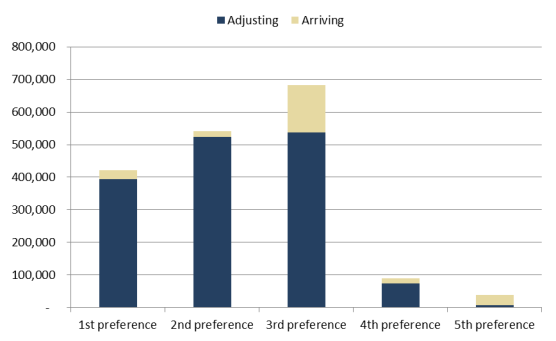

Most foreign nationals who become LPRs were already living in the United States. For example, approximately 86% of employment-based LPRs adjusted to LPR status in FY2014 and only 14% arrived from abroad. Figure 2 shows that over the last decade, within almost all employment-based LPR preference categories, most individuals were adjusting from within the United States, typically as nonimmigrants.21 The 5th preference immigrant investors were the exception and had a majority of individuals being admitted as new arrivals (82% from FY2004-FY2014).22

|

Figure 2. Newly Arriving and Adjusting Employment-Based Principals FY2004-FY2014 Totals by Preference Category |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from the DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. |

The implications of this difference—whether the LPR is "arriving" or "adjusting"—are significant, in that it requires two separate departments to take charge of processing employment-based immigrant visas. Therefore, there are two different sources for data. Data from DOS's NVC caseload of approved pending petitions reflects visa petitions that DOS has received and therefore excludes adjustment of status I-485 applications (processed by USCIS). In addition, USCIS publishes data on their inventory of pending adjustment of status applications (I-485 applications).

Employment-Based Priority Dates for August 2016

As mentioned above, DOS assigns visa priority dates to both individuals adjusting status and those applying from abroad. DOS issues a monthly Visa Bulletin that provides information on how the visa queue translates into waiting times for immigrants.23 The Visa Bulletin issues cutoff dates for numerically limited employment-based preference categories. Individuals with filing dates, or priority dates, earlier than the cutoff dates in the Visa Bulletin are currently being processed.

According to DOS's Visa Bulletin for August 2016, the 1st preference "extraordinary workers" visa category was current, except for China and India, as Table 2 shows. When a category is current, it means an approved petition is now ready for either adjustment of status or consular processing, regardless of priority date. With respect to the 2nd preference "advanced degree" visa category, all countries had a priority date of February 1, 2014, except for China and India. Visas for 3rd preference "professional, skilled, and unskilled workers" visas had a March 15, 2016, priority date, but China, India, and the Philippines had longer waits. For the 4th preference "special immigrants" visa and 4th preference "religious workers" visa, all countries were current except for El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and India. The 5th preference "non-regional center immigrant investors" visa and "immigrant investors" visa were current for all countries except China.

|

Category |

China |

El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras |

India |

Mexico |

Philippines |

All Others |

|

1st: Extraordinary workers |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

current |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

current |

current |

current |

|

2nd: Advanced degrees/ exceptional ability |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

Feb. 1, 2014 |

Nov. 15, 2004 |

Feb. 1, 2014 |

Feb. 1, 2014 |

Feb. 1, 2014 |

|

3rd: Professional, skilled, and unskilled |

Jan. 1, 2010 or |

March 15, 2016 |

Nov. 8, 2004 |

March 15, 2016 |

Feb. 15, 2009 |

March 15, 2016 |

|

4th: Special immigrants |

current |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

Jan. 1, 2010 |

current |

current |

|

5th: Immigrant investors |

Feb, 15, 2014 |

current |

current |

current |

current |

current |

Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Application Final Action Dates For Employment-Based Preference Cases, Visa Bulletin for August 2016.

Notes: *For some preference categories, the Visa Bulletin provides breakdowns for different types of immigrants within the category. Since the priority dates did not differ within these breakdowns of the category, this figure provides the priority dates for the overall category. The exception is the 3rd preference category, where the priority dates for Chinese applicants was January 1, 2010 for those applied as a "professional and skilled" worker and January 1, 2004 for those who applied as an "unskilled" worker.

|

Employment-Based Visa Retrogression Several years ago, "accounting problems" between USCIS's processing of LPR adjustments of status in the United States and DOS's Bureau of Consular Affairs' (BCA) processing of LPR visas abroad became apparent. As discussed above, most employment-based LPRs are adjusting status from within the United States rather than being admitted to the United States from abroad. BCA is dependent on USCIS for current processing data on which to allocate the visa numbers and calculate the employment-based visa priority dates. Therefore, DOS may understate the actual number of approved petitions if USCIS does not forward "adjusting" LPR petitions to the National Visa Center in advance of BCA reaching the visa priority date for each month. When the visa priority dates move backward in time rather than forward, the phenomenon is known as visa retrogression. Visa retrogression occurs when more people apply for a visa in a particular category or country than there are visas available.24 This can result from problems in forwarding approved petitions to the National Visa Center in a timely manner. To cite one example, the Visa Bulletin for September 2005 offered this explanation for visa retrogression: The backlog reduction efforts of both Citizenship and Immigration Services, and the Department of Labor continue to result in very heavy demand for Employment-based numbers. It is anticipated that the amount of such cases will be sufficient to use all available numbers in many categories ... demand in the Employment categories is expected to be far in excess of the annual limits, and once established, cut-off date movements are likely to be slow.25 The most substantial visa retrogression occurred in July 2007. The Visa Bulletin for July 2007 listed the visa priority dates as "current" for the employment-based preferences (except for the unskilled other worker category).26 On July 2, 2007, however, the State Department issued an Update to July Visa Availability that retrogressed the dates to "unavailable." The State Department offered the following explanation: "The sudden backlog reduction efforts by Citizenship and Immigration Services Offices during the past month have resulted in the use of almost 60,000 Employment numbers.... Effective Monday July 2, 2007 there will be no further authorizations in response to requests for Employment-based preference cases."27 Visas in the employment-based categories were unavailable until the beginning of FY2008. Reportedly, USCIS now forwards all approved petitions to the National Visa Center, with the notable exception of those who would clearly be adjusting status within the United States.28 An additional visa retrogression occurred in October 2015. DOS released a revised Visa Bulletin for October 2015, in which it stated that after consultation with DHS, some of the dates for filing applications had been adjusted to "better reflect a timeframe justifying immediate action in the application process."29 With regard to employment-based preference categories, the retrogression affected the 2nd preference category for petitions from India and China. |

New Arrivals: Approved Visa Petitions Pending at the NVC

At the end of each fiscal year, the Department of State publishes a tabulation of approved visa petitions pending with the National Visa Center.30 These data do not constitute a backlog of petitions to be processed; rather, these data represent persons who have been approved for visas that are not yet available due to the numerical limits in the INA. The data only reflect petitions that DOS has received and therefore excludes adjustment of status I-485 applications (processed by USCIS).31 As apparent from the visa retrogression discussion above, these data offer a potentially incomplete account of all prospective employment-based LPRs.

There were 100,747 approved petitions for employment-based LPR visas pending with the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015. This number reflects persons registered under each respective numerical limitation (i.e., the totals represent not only principal applicants or petition beneficiaries, but their spouses and children entitled to derivative status under the INA). Of those approved petitions, there were 82,706 that were in the 1st through 3rd employment-based LPR preference categories.32

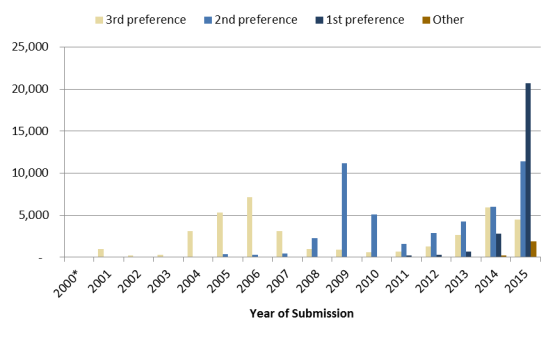

Figure 3 presents the 100,368 approved employment-based visa petitions pending as of November 1, 2015, by date of submission and by preference category for the 1st through 3rd and 5th preference categories. In other words, Figure 3 represents these 100,368 approved pending petitions by the year they were submitted. Most of the 3rd preference approved petitions pending were submitted several years ago. The 1st, 2nd, and 5th preference approved petitions pending are more recent.

The sharp decline in approved 3rd preference category petitions pending that were submitted after 2007 is reportedly due to the visa retrogression that year. Petitions do not appear to be coming forward. Although the economic recession in the United States had no doubt affected the number of employers petitioning for foreign workers, some immigration officials and practitioners maintain that many petitions filed after 2007 are not yet appearing in the approved caseload.33

Overall, the majority of approved employment-based LPR visas pending at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015, were those of 3rd preference "professional and skilled workers"—61,584—as shown in Figure 3. There were also 6,208 approved 3rd preference visas pending for "unskilled workers." In addition, there were 17,662 approved 5th preference "immigrant investor" visas pending. For the 2nd preference, those with advanced degrees, another 11,440 visas were pending. There were also 3,474 approved 1st preference "extraordinary" visas and 379 4th preference "special immigrant" visas pending.

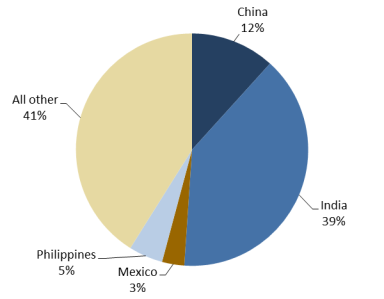

As Figure 4 makes clear, India leads as the source country for most of the approved petitions pending for employment-based LPR visas at the National Visa Center. Almost a third (30%) of the approved pending petitions are from the India (30,281). Philippines follows at 29% or 29,297. China is third at 22% or 22,114. South Korea and Mexico round out the top five source countries with 3% and 2%, respectively, of the approved pending visas.

Figure 5 shows that India's approved visas pending at the National Visa Center are mostly in the 3rd preference "professional, skilled, and unskilled worker" category (21,590); however, India has a noteworthy portion of approved pending visas in the 2nd preference category for those with advanced degrees (7,646). The 3rd preference category also dominates for the Philippines (28,102). A majority of approved visas pending from China are in the 5th preference "immigrant investor" category (15,830).34

These figures representing the approved employment-based LPR visas pending at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015 illustrate that the caseload varies by source country and by preference category. It also reveals that while the India is the largest source country of approved employment-based visas, the Philippines and China make up a noteworthy portion of the approved pending visas.35

Adjustment of Status: Approved I-485 Petitions Pending

Approved visa petitions that are pending at the NVC are not the only source of pending employment-based LPR petitions. USCIS also maintains a system of approved employment-based I-485 petitions (i.e., the Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status) that are pending, which provides another source of data on the number of approved employment-based LPRs. Known as the I-485 Inventory, these data are available by preference category and by top countries. These I-485 data include the employment-based petitioners who plan to adjust status within the United States. The prospective employment-based LPRs who would be new arrivals from abroad are not included in the I-485 Inventory, because they would not need to file I-485 petitions, and they are processed by DOS.

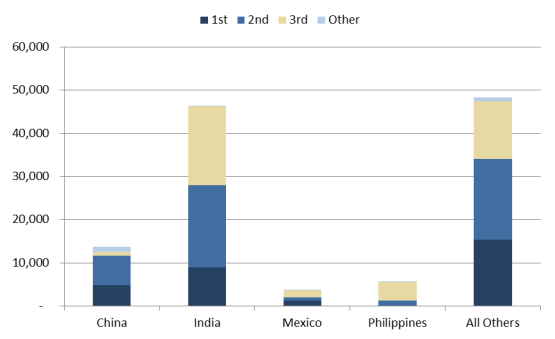

Figure 6 (similar to Figure 3) presents the 117,731 pending approved I-485 petitions as of April 2016, broken down by preference category and the year the petition was submitted to USCIS. The 2nd preference category had the most approved I-485 petitions pending as of April 2016 (46,765) and Figure 6 indicates that many of those I-485 petitions were submitted several years ago.

As noted earlier, the sharp decline in approved 3rd preference category petitions submitted after 2007 is likely due to the visa retrogression in that year. There are 30,457 approved I-485 petitions pending in the 1st preference category and 37,971 approved I-485 petitions pending in the 3rd preference category. Similarly to the approved visa petitions with the National Visa Center, the 1st and 5th preference approved I-485 petitions pending were filed more recently.

The approved I-485 petitions pending in the USCIS Inventory are more numerous in the 1st and 2nd preference categories than the approved visas pending in the 1st and 2nd preference categories at the National Visa Center. However, the 1-485 approved petitions pending in the USCIS inventory are smaller in the 3rd and 5th preference categories than the approved visas pending in the 3rd and 5th preference categories at the National Visa Center.

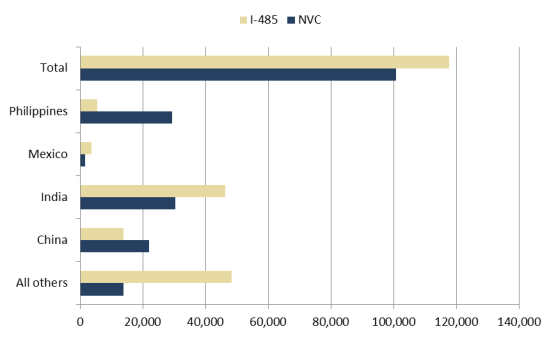

With 46,336 approved I-485 petitions pending, India leads as the top source country with 39% of the approved I-485 petitions pending. China is second with 12% or 13,795. The Philippines (5,596) makes up 5%, and Mexico (3,645) has 3%, as Figure 7 shows.

India dominates the 1st "extraordinary," 2nd "advanced degree," 3rd "professional, skilled, and unskilled worker," and 4th "special immigrant" categories of approved I-485 petitions pending. Figure 8 illustrates that again China is second for the 1st and 2nd preference categories, though China does have the highest number of approved I-485 petitions pending for the 5th "immigrant investor" category.36

Comparative Summation

Table 3 and Figure 9 provide a comparative set of perspectives from which the effects that the per-country limits on legal immigration have on the oversubscribed countries may be assessed. Each depicts the pending caseload of approved employment-based LPR petitions in the 1st through 5th preference categories for both the National Visa Center's approved visa pending and the USCIS's I-485 Inventory of approved petitions. Figure 9 shows the data by top source country, and Table 3 presents the data by visa category.

The data presented in Table 3 demonstrates that the I-485 inventory holds more pending visa applications for adjustments of status (117,731) compared to the NVC pending applications for new arrivals (100,747). The I-485 inventory has higher numbers of pending visas for the 1st, 2nd, and 4th preference categories than the NVC. These patterns are consistent with the earlier analysis of "new arrivals" and "adjustments" showing that more employment-based migrants were adjusting status rather newly arriving. However, the 3rd and 5th preference categories have a higher number of pending visa applications in the NVC for new arrivals than they do in the I-485 inventory.

|

Preference Category |

Numerical Limits |

Admissions from Abroad (NVC) |

Admissions from within the U.S. |

|

1st preference— |

28.6% of worldwide limit plus unused 4th and 5th preference (40,040) |

3,474 |

30,457 |

|

2nd preference— |

28.6% of worldwide limit plus unused 1st preference (40,040) |

11,440 |

46,765 |

|

3rd preference— |

28.6% of worldwide limit plus unused 1st or 2nd preference; unskilled limited to 10,0000 (40,040) |

67,792 |

37,971 |

|

4th preference— |

7.1% of worldwide limit; religious workers limited to 5,000 (9,940) |

379 |

1,129 |

|

5th preference— |

7.1% of worldwide limit (9,940) |

17,662 |

1,409 |

|

Total Employment |

140,000 |

100,747 |

117,731 |

Source: CRS analysis of data from the Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-Sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015; and USCIS I-485 Inventory of pending petitions, as of April 2016.

The data in Figure 9, along with the previous analyses, suggest that the majority of Indians are waiting to adjust status in the United States, while the majority of Filipinos are waiting to immigrate from abroad. Those with approved pending petitions from China seem to be more evenly split among those who might be adjustments and those who might be new arrivals. It is also evident that policy options aimed at advancing approved petitions from India and China would also bear on approved petitions pending from the Philippines.

Legislative and Policy Issues

Employment-based immigration often raises concerns about foreign workers competing with or displacing U.S. workers. The concerns were especially prevalent during the past decade when economic indicators showed that the economy went into a recession.37 Although some economic indicators suggest modest growth, unemployment levels remained high long after the end of the recession and only fell back to their pre-recession level in late 2015. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in May 2016 there were 7.4 million unemployed persons, compared with 5.5 million job openings (a ratio of 13 job seekers for every 10 job openings).38

Even as the number of unemployed individuals outnumbers the number of open positions, some employers assert that they continue to need the "best and the brightest" workers, regardless of their country of birth, to remain competitive in a worldwide market and to keep their firms in the United States. While support for the option of increasing employment-based immigration may be dampened by economic conditions, proponents argue it is an essential ingredient for economic growth.39 Those opposing increases in employment-based LPRs in particular assert that there is no compelling evidence of labor shortages and cite the rate of unemployment across various occupations and labor markets.40 They argue that recruiting foreign workers while many Americans remain unemployed would have a deleterious effect on salaries, compensation, and working conditions in the United States.41

Changing Per-country Limits42

With this economic and political backdrop, the option of lifting the per-country caps on employment-based LPRs has gained attention. Some observers contend that the elimination of the per-country caps would increase the flow of high-skilled immigrants without increasing the total annual admission of employment-based LPRs.43 The presumption is that many high-skilled people (proponents cite those from India and China, in particular) would then move closer to the head of the line to become LPRs.44

Legislative options that have been suggested include the following:

- a targeted lifting of the country caps on the top two preference categories of priority workers and those who are deemed exceptional, extraordinary, or outstanding individuals;

- a categorical lifting of the country caps on all employment-based preference categories, up to the 140,000 worldwide ceiling on employment-based LPRs; or

- a complete lifting of the country caps on all employment-based preference categories as well as excluding employment-based LPRs from the calculation of the family-based and worldwide per-country ceilings.

Possible Alternatives to Revising the Country Caps

While this report is expressly focused on the per-country ceilings in the INA, revising the country caps is just one of many ways to foster high-skilled immigration to the United States. Several possible alternatives include the following:45

- reallocate the employment-based preferences: If the objective is to increase the number of the highest-skilled immigrants without raising the worldwide level, then reallocating additional visas to the 1st and 2nd preference categories is another option. In doing so, it would increase the flow of employment-based immigrants. This alternative, however, would not address the sheer number of approved LPR petitions from China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines. Many advanced-degree workers and all professional and skilled workers who have approved petitions have employers who have already been certified to hire them and have offered jobs to them.

- reallocate the diversity visas: Some have observed that the 50,000 diversity visas would be better used for high-skilled immigrants.46

- permit selected nonimmigrants to adjust to LPR status outside the numerical limits: This alternative would be establishing an employment-based LPR category for foreign students who have obtained a graduate degree at the level of master's or higher in a science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) field from a U.S. institution.

Statistical Projections Elusive

It is not possible to statistically project the effects of revising the per-country limits for several reasons. Foremost, it is not known whether approved petitions may be counted in both the National Visa Center data and the USCIS I-485 Inventory. If so, how is the number of approved employment-based petitions affected?

Secondly, the full effect that the 2007 visa retrogression has had on the processing of employment-based visas is not known. More precisely, if the visa priority dates meaningfully advanced, would a substantial number of post-2007 petitions be approved and advance to the pending caseload? How many petitions are in the pipeline?

It is quite likely that additional people would seek employment-based LPR visas if the wait times were shorter. Employers as well as prospective foreign workers may be more likely to file petitions if the delays were shortened. In other words, the reduction in the number of approved petitions pending might be short-lived.

Finally, if the per-country ceilings were eliminated for employment-based LPRs without any other revisions to permanent legal immigration, it would likely have "ripple" effects on family-based immigration as well as other potential employment-based LPRs.

Summary of Arguments in Debate

Some observe that the per-country ceilings are arbitrary and argue that country caps should not be applied to employment-based preference categories. They maintain that employability has nothing to do with country of birth and that U.S. employers are not allowed to discriminate based on nationality or country of origin. They further opine that it is discriminatory to have laws that limit the number of employment-based LPRs according to country of origin.47

Proponents of per-country ceilings maintain that the statutory per-country ceilings restrain the dominance of high-demand countries and preserve the diversity of the immigrant flows. The Immigration Amendments of 1965 ended the country-of-origin quota system that overwhelmingly favored European immigrants, and subsequent amendments to the INA included immigrants from Western Hemisphere countries within the worldwide and per-country limits. Supporters of current law maintain that U.S. immigration policy has been more equitable and less discriminatory in terms of country of origin as a result of these reforms, because the INA puts country of origin on an equal playing field.

Appendix A. Further Breakdowns of Employment-Based Petitions Pending by Top Countries

Further analysis that compares the distributions of the employment-based preference categories reveals additional differences among the top countries. Even more striking, however, are the country differences between those approved visa petitions pending with the National Visa Center (NVC) and those approved I-485 petitions pending with the USCIS.

Approved Visa Petitions Pending at the National Visa Center

The number of approved 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th preference visas pending is small in contrast to the 3rd preference category. Table A-1 presents the data for the different preference categories' top five countries. China makes up the largest portion of the approved visas pending at the NVC for the 1st and 5th preference categories. India has the largest number of approved visas pending with the NVC for the 2nd and 3rd preference categories combined and the Philippines is responsible for the largest portion within 3rd preference category.

Table A-1. Approved Employment-Based Petitions Pending as of November 2015, by Top Countries

National Visa Center

|

1st Preference |

2nd Preference |

3rd Preference: Professional & Skilled |

3rd Preference: Unskilled |

4th Preference |

5th Preference |

|||||||

|

Country |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

|

China |

902 |

26% |

893 |

8% |

1,681 |

3% |

2,796 |

45% |

- |

- |

15,830 |

90% |

|

India |

333 |

10% |

7,646 |

67% |

21,590 |

35% |

518 |

8% |

121 |

32% |

- |

- |

|

Great Britain |

215 |

6% |

- |

- |

1,047 |

2% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

Canada |

212 |

6% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

Iran |

184 |

5% |

168 |

2% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

South Korea |

- |

- |

964 |

8% |

1,379 |

2% |

819 |

13% |

17 |

4% |

148 |

1% |

|

Philippines |

- |

- |

379 |

3% |

28,102 |

45% |

770 |

13% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Afghanistan |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

21 |

6% |

- |

- |

||

|

Nigeria |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

18 |

5% |

- |

- |

||

|

Mexico |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

503 |

8% |

16 |

4% |

- |

- |

|

Hong Kong |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

254 |

1% |

||

|

Vietnam |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

245 |

1% |

||

|

Taiwan |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

158 |

1% |

||

|

All Others |

1,628 |

47% |

1,390 |

12% |

7,785 |

13% |

802 |

13% |

186 |

49% |

1,027 |

6% |

|

Total |

3,474 |

100% |

11,440 |

100% |

61,584 |

100% |

6,208 |

100% |

379 |

100% |

17,662 |

100% |

Source: CRS analysis of data from the Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015.

Notes: There were 100.747 total approved pending employment-based petitions as of November 1, 2015. Percentages are provided for the top five countries for each preference category. Great Britain includes Northern Ireland. Data for the 3rd preference category is broken down by professional and skilled worker petitions and unskilled worker petitions. The total pending approved pending employment-based petitions for the 3rd preference category was 67,792.

Approved I-485 Petitions Pending

The following table looks at the portion of approved I-485 petitions pending from select countries for each of the five employment-based preference categories. India has the largest number of approved pending I-485 petitions for all categories, except the 5th preference, where China is responsible for the largest portion. China also has the 2nd largest number of approved pending I-485 petitions for the 1st and 2nd preference categories.

|

1st Preference |

2nd Preference |

3rd Preference |

4th Preference |

5th Preference |

||||||

|

Country |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

Petitions |

% |

|

China |

4,797 |

16% |

6,881 |

15% |

848 |

2% |

24 |

2% |

1,245 |

88% |

|

India |

9,009 |

30% |

19,042 |

41% |

18,124 |

48% |

146 |

13% |

15 |

1% |

|

Mexico |

1,236 |

4% |

832 |

2% |

1,508 |

4% |

58 |

5% |

11 |

1% |

|

Philippines |

115 |

<1% |

1,182 |

2% |

4,259 |

11% |

39 |

4% |

1 |

<1% |

|

All Others |

15,300 |

50% |

18,828 |

40% |

13,232 |

35% |

862 |

76% |

141 |

10% |

|

Total |

30,457 |

100% |

46,765 |

100% |

37,971 |

100% |

1,129 |

100% |

1,409 |

100% |

Source: USCIS I-485 Employment-Based Inventory Statistics, as of April 2016.

Notes: There were a total of 117,731 pending approved I-485 petitions.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report was originally written by Ruth Wasem, former Specialist in Immigration Policy.

Footnotes

| 1. |

LPRs are immigrants who are admitted to the United States or who adjust status within the United States. Immigrants refers to individuals living in the United States permanently. In this report, LPR and immigrant are used interchangeably. |

| 2. |

For a more complete discussion of legal immigration, see CRS Report RL32235, U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 3. |

P.L. 101-649. The Immigration Act of 1990 increased the limits of legal immigration to the United States, among other things. With respect to employment-based visas, the act revised the preference system and the labor certification process. |

| 4. |

§201 of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1151. |

| 5. |

§201 of INA; 8 U.S.C. §1151. |

| 6. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43145, U.S. Family-Based Immigration Policy, by William A. Kandel. |

| 7. |

"Immediate relatives" are defined by the INA to include the spouses and unmarried minor children of U.S. citizens, and the parents of adult U.S. citizens. |

| 8. |

CRS Report RL31269, Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy, by Andorra Bruno. |

| 9. |

§202(a)(2) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1151. |

| 10. |

§203(b) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1153. |

| 11. |

§212(a)(5) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. 1182. |

| 12. |

For further discussion of labor certification, see CRS Report RL33977, Immigration of Foreign Workers: Labor Market Tests and Protections, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 13. |

§202(a)(2) of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1151. |

| 14. |

§201 of the INA; 8 U.S.C. §1151. |

| 15. |

The term "dependent area" includes any colony, component, or dependent area of a foreign state. Examples are the Azores and Madeira Islands of Portugal and Macau of the People's Republic of China. |

| 16. |

The Immigration Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-649) substantially rewrote employment-based preference categories and raised the numerical limits. These amendments were fully implemented by 1994. |

| 17. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2014 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, https://www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics. |

| 18. |

There was a dip in permanent employment-based visa admissions in 2003 and a subsequent spike in 2004 due in large part to processing delays. These delays were the result of the transfer of immigration functions from the Department of Justice to the Department of Homeland Security in 2003. |

| 19. |

Individuals can use DOS's Visa Bulletin to check whether their priority date is current. |

| 20. |

The National Visa Center will hold petitions for individuals adjusting status until petitioner asks for it to be transferred to USCIS. |

| 21. |

Nonimmigrants are admitted for a specific purpose and a temporary period of time—such as tourists, foreign students, diplomats, temporary agricultural workers, exchange visitors, or intracompany business personnel. Nonimmigrants are often referred to by the letter that denotes their specific provision in the statute, such as H-2A agricultural workers, F-1 foreign students, or J-1 cultural exchange visitors. |

| 22. |

CRS calculation of data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's 2014 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. CRS divided the total number of newly arrived employment-based immigrants over the total number of employment-based immigrants for FY2004 to FY2014. |

| 23. |

Due to numerical limitations for each preference category, the number of approved petitions for a specific preference category may exceed the number of available visas for that year. In addition, due to per-country ceilings, the number of approved petitions from a specific country may exceed its 7% cap of the worldwide level of LPRs for that year. As a result, individuals with approved petitions may be placed in a queue until the next year or until a visa is available. |

| 24. |

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Visa Retrogression, https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-processes-and-procedures/visa-availability-priority-dates/visa-retrogression. |

| 25. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin, http://travel.state.gov/visa/frvi/bulletin/bulletin_1360.html. |

| 26. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin, No. 107, http://travel.state.gov/visa/frvi/bulletin/bulletin_3258.html. |

| 27. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin, No. 108, http://travel.state.gov/visa/frvi/bulletin/bulletin_3266.html. |

| 28. |

Meeting of CRS immigration analysts with DHS and DOS immigration statisticians, August 4, 2011. |

| 29. |

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Visa Bulletin for October 2015, No. 85, https://travel.state.gov/content/visas/en/law-and-policy/bulletin/2016/visa-bulletin-for-october-2015.html. |

| 30. |

See the Department of State website: http://www.travel.state.gov/visa/statistics/ivstats/ivstats_4581.html. |

| 31. |

U.S. Department of State, Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-Sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015. |

| 32. |

Ibid. |

| 33. |

Meeting of CRS immigration analysts with DHS and DOS immigration statisticians, August 4, 2011. |

| 34. |

U.S. Department of State, Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-Based Preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2015, https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/Statistics/Immigrant-Statistics/WaitingListItem.pdf. |

| 35. |

For further analysis by country and preference category, see Appendix A. |

| 36. |

For further analysis by country and preference category, see Appendix A. |

| 37. |

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) declared the U.S. economy went into a recession in December 2007. |

| 38. |

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, The Employment Situation-May 2016, June 3, 2016 and U.S. Department of Labor , Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, http://www.bls.gov/jlt/. |

| 39. |

Many of the comprehensive immigration reform bills of the 2000s would have increased the total number of employment-based immigrants. Some would have revised the employment-based preference categories. A merit-based point system was also considered. For further background, see Appendix D in CRS Report RL32235, U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 40. |

For further discussion, see U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, STEM the Tide: Should America Try to Prevent an Exodus of Foreign Graduates of U.S. Universities with Advanced Science Degrees?, 112th Cong., 1st sess., October 5, 2011; and CRS Report R40080, Job Loss and Infrastructure Job Creation Spending During the Recession, by Linda Levine. |

| 41. |

For further discussion, see CRS Report RL33977, Immigration of Foreign Workers: Labor Market Tests and Protections, by Ruth Ellen Wasem; and CRS Report 95-408, Immigration: The Effects on Low-Skilled and High-Skilled Native-Born Workers, by Linda Levine. |

| 42. |

While this report is expressly focused on the per-country ceilings in the INA, revising the country caps are just one of many ways to foster high-skilled immigration to the United States. |

| 43. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, H-1B Visas: Designing a Program to Meet the Needs of the U.S. Economy and U.S. Workers, 112th Cong., 1st sess., March 31, 2011; and U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, STEM the Tide: Should America Try to Prevent an Exodus of Foreign Graduates of U.S. Universities with Advanced Science Degrees?, 112th Cong., 1st sess., October 5, 2011. |

| 44. |

Stuart Anderson, Waiting and More Waiting: America's Family and Employment-Based Immigration System, National Foundation for American Policy, October 4, 2011. |

| 45. |

For further discussion, see CRS Report RL32235, U.S. Immigration Policy on Permanent Admissions, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 46. |

The diversity visas are allocated to natives of countries from which immigrant admissions were lower than a grand total of 50,000 over the preceding five years. CRS Report R41747, Diversity Immigrant Visa Lottery Issues, by Ruth Ellen Wasem. |

| 47. |

Immigration Voice, "The Per-Country Rationing of Green Cards that Exacerbates the Delays," press release, undated, http://immigrationvoice.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=5&Itemid=47. |